On the afternoon of August 15, 1945, thirteen-year-old Gu Weiqing suddenly heard the deafening sounds of firecrackers, drumbeating, and victory chants from outside. The whole family rushed out and found the streets of Chongqing flooded with paraders in tears and exaltation. “It finally dawned!”1 Paul Child, then serving in the Office of Strategic Services in Kunming, observed:

The streets of the city are filled with windows of red exploded-fire-cracker-casings. Everywhere are national government flags and victory signs in both Chinese and English. Some of the inscriptions: “Thank you President Roosevelt and President Chiang” – “Hooray for final Glorious Victory” – “Let us now fight for Peace as we fighted [fought] for War!” Crowds jam all streets, with happy faces. Dragons 60 feet long, made of flowers and paper are whirled through the alleys accompanied by gongs, flutes, drums and firecrackers. Every store front has red paper victory signs in gold on red … this afternoon, in this Chinese city, with its crowds of happy faces, its firecrackers, its wildly-twisting dragons, its drums and gongs, its flags and inscriptions has given me the feeling that perhaps the God damned war is finished.2

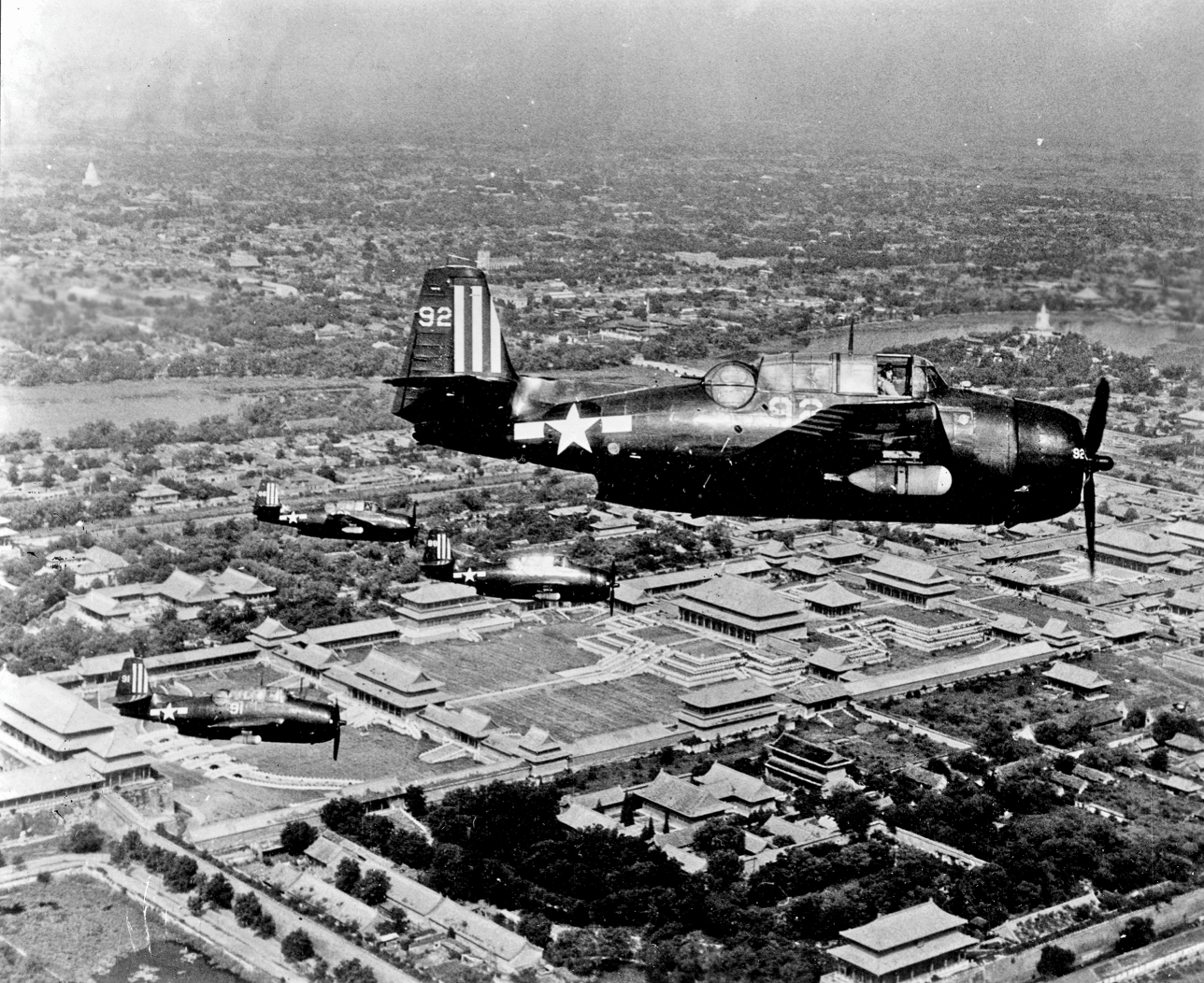

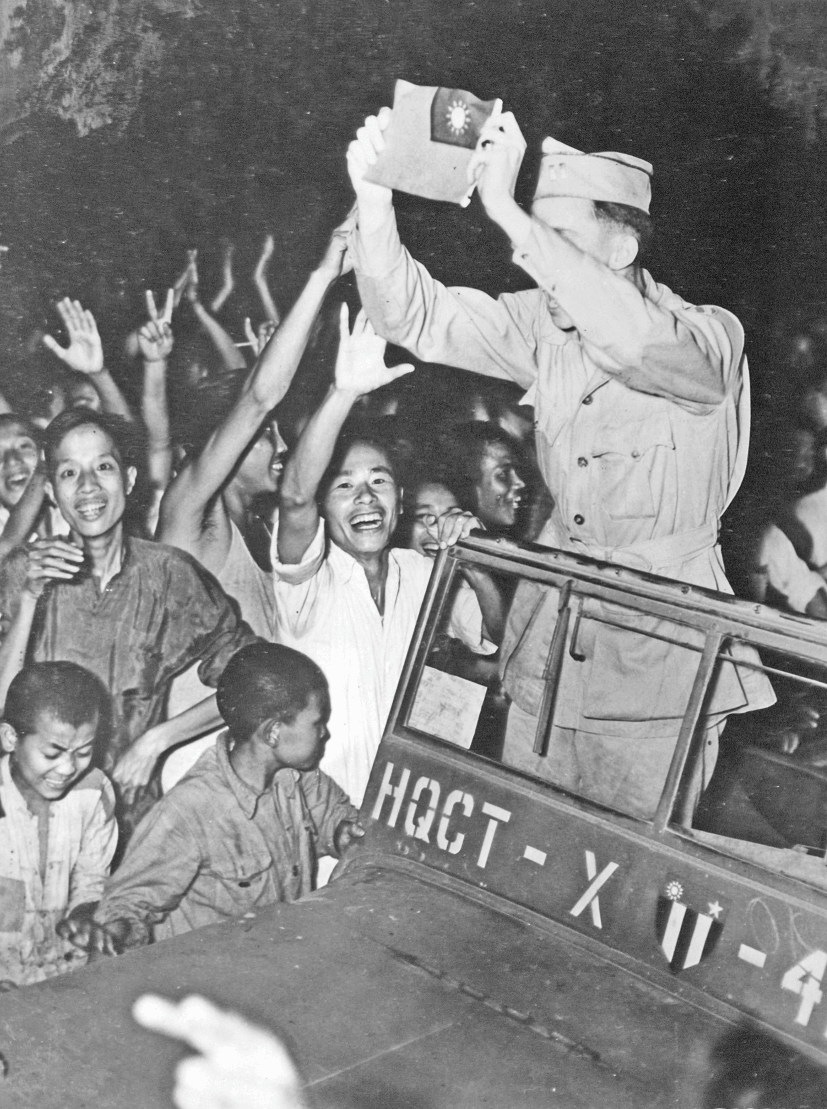

As American air units flew in a V shape overhead, overseeing the ground filled with crowds and joy, the glorious news of the end of war exploded in China and became perpetually engraved in the memories of all who had long fought and survived the most devastating war in history (see Figure 1.1). Unlike the meticulously planned D-Day landing and subsequent liberation of Paris, the abrupt end of the war in the Pacific, accelerated by the catastrophic atomic bombs, surprised both the Nationalists and Communists. Months passed before the Japanese and collaborationist forces were finally replaced by Chinese troops who rushed to reach former Japanese-occupied areas. The continuous presence of more than a million armed Japanese forces before their repatriation was not to be taken lightly.3 The dire situation was further complicated by the direct military involvement of the Soviet Union in Manchuria. In the contentious environment of the Chinese civil war and the emerging Cold War, the Japanese surrender did not mark a clean line between war and peace, but rather the beginning of intense postwar struggles.4

Figure 1.1 A US Army captain holding a flag of China, greeted by cheering civilians in Chongqing upon news of the Japanese surrender, August 1945. NARA.

Upon Japanese surrender, the Nationalists’ main concern was to prevent Chinese Communists from taking advantage of any potential power vacuum. Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in China, ordered that Japanese forces must remain in their positions, keep good order of those areas, and only surrender their weapons and turn over their occupied territories to personnel authorized by him.5 Because of such strategic priorities, the Nationalists generally did not treat Japanese troops in China harshly. To the initial surprise of many Japanese officers who expected much more severe punishment, Chiang announced the principle of “repaying hatred with benevolence,” invoking both Confucian morals and Christian ethics. War trials were held, and Japanese soldiers occasionally were beaten in the streets by local civilians, but rarely was there any mass retribution. Unsurprisingly, the Communists ignored Chiang’s instructions of standing still and took quick action. General Zhu De, commander of the Communist forces, announced that “any anti-Japanese armed forces can take the surrender of the Japanese.”6 Although they had to abort the campaign to seize large cities, opposed by both the United States and the Soviet Union, Communist troops seized more than 150 towns at the county level and above in North China and succeeded in consolidating rural areas.7 They confiscated Japanese weapons and equipment and fought with those who refused. Like the Nationalist army that used Japanese soldiers to assist in preventing Communist takeovers in certain areas, the Communists also recruited some Japanese divisions, especially the much-needed technical and medical staff, into the 8th Route Army to fight in the civil war.8 But unlike the lenient policy of the Nationalists, the Communist Party called for severe punishments of Japanese war criminals and Chinese collaborators and attacked the Nationalist policy on Japanese surrender as “a hoax.”9

This was the chaotic environment into which US occupying forces entered in the wake of WWII. Before delving into the everyday encounters between American GIs and Chinese civilians, it is crucial to understand the complex and evolving nature of the US military’s postwar involvement in China, the tactics that it adopted, and their impacts. At the official invitation of the Nationalist Government, American service members carried out a wide range of activities that extended beyond the scope of wartime engagements and traditional warfare. These heterogeneous operations, including occupation missions as well as noncombat duties and “peaceful” tasks, not only defined the principal tasks of GIs in the country, but also set the stage, terms, and tone for their daily interactions with the Chinese populace. Rather than solely relying on decisive battles and supreme firepower, the US employed a “show of force” tactic within the changing geopolitical landscape. This strategy included large-scale military exercises and parades, positioning of naval forces in key waterways, protection of rail lines and key installations, and regular reconnaissance patrols by air and land. It also featured dramatic ceremonial events such as the official Japanese surrender and public war crime trials. These spectacles, intended to stage American victory, might, and justice, targeted both enemies and allies, friendly and hostile groups. The use or mere threat of force aimed to ensure submission and deference by showcasing America’s readiness and capacity to act. The goal was to demonstrate the United States’ military strength, power, and dominance in the postwar world. However, faced with a mission of near-impossible objectives in a precarious environment, the display of American force was only partly effective, with varying degrees of success when it came to the Japanese, the Communists, and the Nationalists.

An Untenable Position

More than fifty thousand marines had arrived in North China by October 1945. Initially, Lieutenant General Albert C. Wedemeyer, Commander of US Forces, China Theater, had called for six or seven divisions to serve as a barrier force aimed at deterring Soviet expansion in the region. Two were sent: the 1st Marine Division infantry that occupied positions in Tanggu, Tianjin, Beijing, and the Qinhuangdao area, and the 6th Marine Division that moved into Qingdao. Concerned about Soviet assistance to the Communists and American strategic interests in the region, the US Navy used the port of Qingdao as a major fleet anchorage in the Far East. The number of US military personnel in China almost doubled following the end of WWII, reaching a peak of more than one hundred thousand, but it fell to below twelve thousand by the end of 1946, when a series of deactivations and reorganizations was implemented. In January 1947, when George Marshall’s mission to bring peace and stability to China was declared unsuccessful, President Truman ordered military personnel home. Several thousand personnel remained on the eve of the Communist victory, and the last group withdrew from Qingdao in late May 1949.10

The United States Marine Corps’ primary occupation duties included disarming and repatriating Japanese troops, liberating and rehabilitating Allied internees and POWs, and assisting the Nationalist Government in reoccupying key areas. On behalf of Chiang Kai-shek, the American military accepted Japanese surrenders in North China before the arrival of Nationalist forces. The subsequent repatriation mission involved disarming, subsisting, and transporting a large number of Japanese military and civilian personnel, as well as Koreans and Taiwanese. By October 1946, more than 1 million people had been deported from Manchuria, mainly through the port of Huludao. This massive undertaking continued until the summer of 1948, as many remained stranded in Communist-controlled areas, further complicated by transportation disruptions caused by the civil war.11 Weary of Soviet aggressions together with China’s civil war development, the American army and navy helped transport by air and sea Chiang’s major divisions to northern and eastern China to prevent Communist takeover of these areas. In addition, marines guarded key rail lines, bridges, and mines to ensure vital coal and supply train transportation between North China and Shanghai, as well as to Manchuria. More broadly, and long after these initial goals were achieved, American military personnel continued their involvement in China. They engaged in a variety of roles that would later be known as MOOTW, short for “military operations other than war,” including nation assistance, humanitarian assistance, and peacekeeping.12 Army and marine officers provided personnel for the Executive Headquarters in Beijing, which directed truce teams to conduct field investigations and helped supervise the agreement between the Nationalists and Communists. To “assist and advise the Chinese government,” nearly a thousand members of the Military Advisory Group in China, known as MAGIC, helped train and strengthen the efficiency of the Nationalist military. The last group withdrew from Nanjing by March 1949.13 Moreover, American servicemen supported the relief efforts of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) in China, which was its largest single-country program, with a total estimated cost of US$670 million. They helped distribute massive quantities of war surplus supplies, providing food, shelter, and medical supplies to civilians across China. The final activities of the UNRRA mission were completed by March 1948.14 Throughout their deployment, US soldiers acted as a “police force” while upholding their traditional role as protectors of American lives and property. As the Communist takeover approached, the final groups evacuated citizens, defended the naval base in Qingdao, and provided cover and support for the retreat of Nationalist forces from the area.15

In general, US servicemen were tasked with maintaining neutrality in the civil strife while assisting and advising the Nationalist Government, an ambivalent goal that reflected the unsettled American policy toward China. At the conclusion of WWII, the American government saw the utmost importance of a strong, united, and democratic China and pledged support for the Nationalists. But it did not want to get involved in China’s civil war, a principle of Truman’s foreign policy.16 The American military and the US Department of State disagreed both on whether the CCP would pose a real threat to the United States and on the appropriate level of aid and intervention to be provided to the Nationalists. As “an instrument of American policy,” the marines served in what Secretary of Defense James Forrestal described as “the balance of order” in China.17 However, amidst a fratricidal war with ambiguous instructions to “abstain from active participation” while “cooperating” with Nationalist forces, the marines essentially “walked a tightrope to maintain the illusion of friendly neutrality.”18 This untenable position created critical challenges in the field. As Second Lieutenant John B. Simms put it, “It was probably more the political consideration of not having a major clash with the U.S. forces than our strength” that prevented Communists from “moving in and taking over.” While “only marginally effective as a unit” and handicapped in movement and knowledge of the area, Simms added, “The greatest handicap was trying to maintain a neutral status.”19 Deployed across Nationalist, Communist, and contested areas, US combat troops faced stepping into a “hornet’s nest” and becoming embroiled in a violent conflict, with the containment of Communism looming on the horizon. In the absence of a clear victory or timeline, the uncertainties surrounding their deployment, including how long it would last and how to determine their success, imposed serious constraints on the operations as well as on soldiers’ morale.

Many of the soldiers were unprepared and untrained for the prolonged peace operations in a setting of potential conflict. According to an official Marine Corps account, “the average Marine on postwar duty in China found himself an uneasy spectator or sometimes an unwilling participant in a war which he little understood and could not prevent.”20 While the new recruits lacked adequate training and experience, the battle-hardened veterans who had fought in some of the bloodiest Pacific campaigns were plagued by homesickness, boredom, post-traumatic stress disorder, and low morale. Due to the scope and complexity of their duties, American servicemen encountered a wide spectrum of situations from surprising guerrilla attacks to widespread urban crimes and civilian hostility. In the rural environments, “a strange never-never land of allies who were not quite allies and not-quite-at-war hostiles who took pot shots and mined tracks,” they were vulnerable to assaults from Communist forces, local bandits, and sometimes even Nationalist soldiers.21 When under attack, GIs were directed to exercise restraint and avoid escalating the conflict – a frustrating and perilous experience. In the unstable urban environment plagued by poverty and social unrest, they lacked clear instructions and effective tools to handle a range of challenging situations from armed gang robbery to petty theft. As a result, guard duties turned into “accidents” and deadly incidents, and military operations became an ad hoc, improvised response by individual soldiers and officers at the front trying to manage uncertain situations and unexpected crises, sometimes resorting to unnecessary and excessive force.

Ultimately, the China operations proved untenable. Even the commanding generals felt that the occupation’s goal was “ill-considered and ambiguous in meaning,” making it “an intangible mission” difficult to execute or even explain to soldiers.22 While some of its initial goals were considered successful, the results of others were more mixed and controversial. As American servicemen accepted the Japanese surrender in official ceremonies, engaged in sporadic clashes with Communist forces, and adjudicated Japanese criminals in China without authorization from the Nationalist Government, they engaged in perilous encounters with friends and enemies as well as various groups in between.

Staging Victory: Japanese Surrender Ceremonies

The first and foremost objective of the American occupation was to disarm the Japanese and accept their surrender. To most marines who landed in North China in the autumn of 1945, it was their first close encounter with individual Japanese soldiers in a noncombat setting, making it an “experience in itself.” When describing their initial contact with the Japanese, Officer Simms observed: “Here was an armed U.S. Marine watching an armed enemy pass by within spitting distance. Neither they nor I really knew what measure to take,” and “we ended up simply ignoring the existence of the other.”23 In an odd fashion, Japanese officers continued to reside in the genteel old Astor House Hotel in Tianjin and dined next to American officers in the same breakfast room for the first few weeks.24 Out in the countryside in Hebei Province, Private E. B. Sledge recorded the visual shock of encountering Japanese troops on duty: “a Japanese officer in dress uniform and cap, Sam Browne belt, campaign ribbons, and white gloves standing erect in the turret – with his samurai saber slung over his shoulder.”25 Besides a few incidents of gunshots, the initial American encounter with Japanese troops in China was mostly marked by silence. The “clackety-clack of the swords clanging and the hob-nailed kind of boots” of the Japanese soldiers walking in silence, as well as the heads-down Japanese civilians dressed in disguise fearing revenge from the Chinese, were all markers of defeat.26

The Americans’ initial attitude was to “go hard on the Japanese.”27 Commanders bore their victor identity clearly with the sentiment that “we have won the goddam war, and to the victors belong the spoils.”28 Brigadier General William A. Worton, Chief of Staff of the IIIAC, instructed his subordinates to take the “bloody houses” from enemy aliens for commanding generals’ accommodations in the city. Since “there were no guidelines for this duty in the Marine Corps Manual,” the general suggested giving them three days to get out, and “be dressed for it” when giving such an order, as “if you’re going to kick their asses out of their own houses, make sure your boots are highly polished.”29 Major General Lemuel C. Shepherd, commander of the 6th Marine Division who took the division from Okinawa to Qingdao, commented about the Japanese in the city: “We kicked them so badly that I think we took all the sting out of them for a while, anyhow, and they are very nice to us, for they know where their bread is buttered.” Rather than appear “too kind,” he was further advised by his aides to be “forceful” with the regional Japanese representative for surrender.30

“To be forceful” with the Japanese was a result of American sentiments after the brutal Pacific warfare. Commanders and soldiers shared indignation toward Japanese troops who were seen as “bastards” and “rattlesnakes.” American wartime propaganda often invoked racist images to motivate their soldiers, and dehumanization of the Japanese soldiers as animals or subhuman was a common practice to justify the killing.31 Japanese cruelty was extensively covered in the media, creating widespread loathing. Displaying a forceful attitude was also a deliberate military strategy based on psychological manipulation, namely to prevent potential resistance and promote cooperation through intimidation, threat, and warning. When the war ended suddenly, the massive number of Japanese troops in China had little sense of defeat; many believed they “never lost any war” and didn’t feel they had lost this one.32 So the line of victory needed to be clearly drawn.

The American exhibition of force was immediate upon arrival, as thousands of marines made a dramatic entrance, riding through the major cities on trains, open trucks, and Jeeps. Their victory parades were truly a spectacle that invited gazes. As American soldiers waved, throngs of local civilians flooded the streets, holding flags, horns, banners, and streamers, while others crowded windows and rooftops along the path (see Figure 1.2). Shortly thereafter, the American military continued to impress with additional marches along these thoroughfares. On October 19, 1945, for example, the first marine parade was held in Beijing, when “tanks, artillery, and vehicles were freshly painted field green and were wiped with a thin film of oil so that they glistened in the bright sun.” The troops “looked sharp,” with all parts of their uniforms ordered to be “tailored to ‘fit perfectly’” and “squared away and paraded with absolute precision.”33 In Tianjin, troops marched “for psychological purposes which worked both ways: it gave the Chinese a fete and a big pat on the back, it gave our Marines a thrill, and it said something to the Japanese.”34 While displaying sharp-looking GIs armed with powerful artillery and air force, US commanders also deliberately used a “rumpled appearance” and “sartorial insouciance” to accomplish “a subliminal strategic purpose of some sort.” Anticipating that the leadership’s landing in Tianjin would be “received very formally at the airport by a battalion of Japanese,” General Worton gave orders of dressing casually in khaki – that is, to “counter-balance the icy propriety of the Japanese officers’ uniforms with an American informality that would do something to their psyche.”35 Upon entering Shanghai in September 1945, Admiral Milton E. Miles, “the dare-devil Commander of U.S. Naval Guerilla Forces in China,” who had carried on a “Lawrence of Arabia” type of guerilla activity in the war, inspected a Japanese ship, ate some spam, and “appropriated a couple of hara-kiri knives and samurai swords.” The ship was seized by Elmo R. Zumwalt Jr., then a young navy officer and a future admiral himself, who had led a very small crew from the Pacific to Shanghai to gather intelligence. Upon his initial days in the city before reinforcements came, Zumwalt successfully secured Japanese vessels, docks, and warehouses by teaching the “vanquished” a lesson. He answered the “truculent demands” from a Japanese captain bedecked in full regalia by taking his pistol, spinning him around, and rooster-walking him away using a grip on the seat of his pants.36

Figure 1.2 Marines entering Tianjin, welcomed by local crowds giving a thumbs-up, October 1945. MCHD.

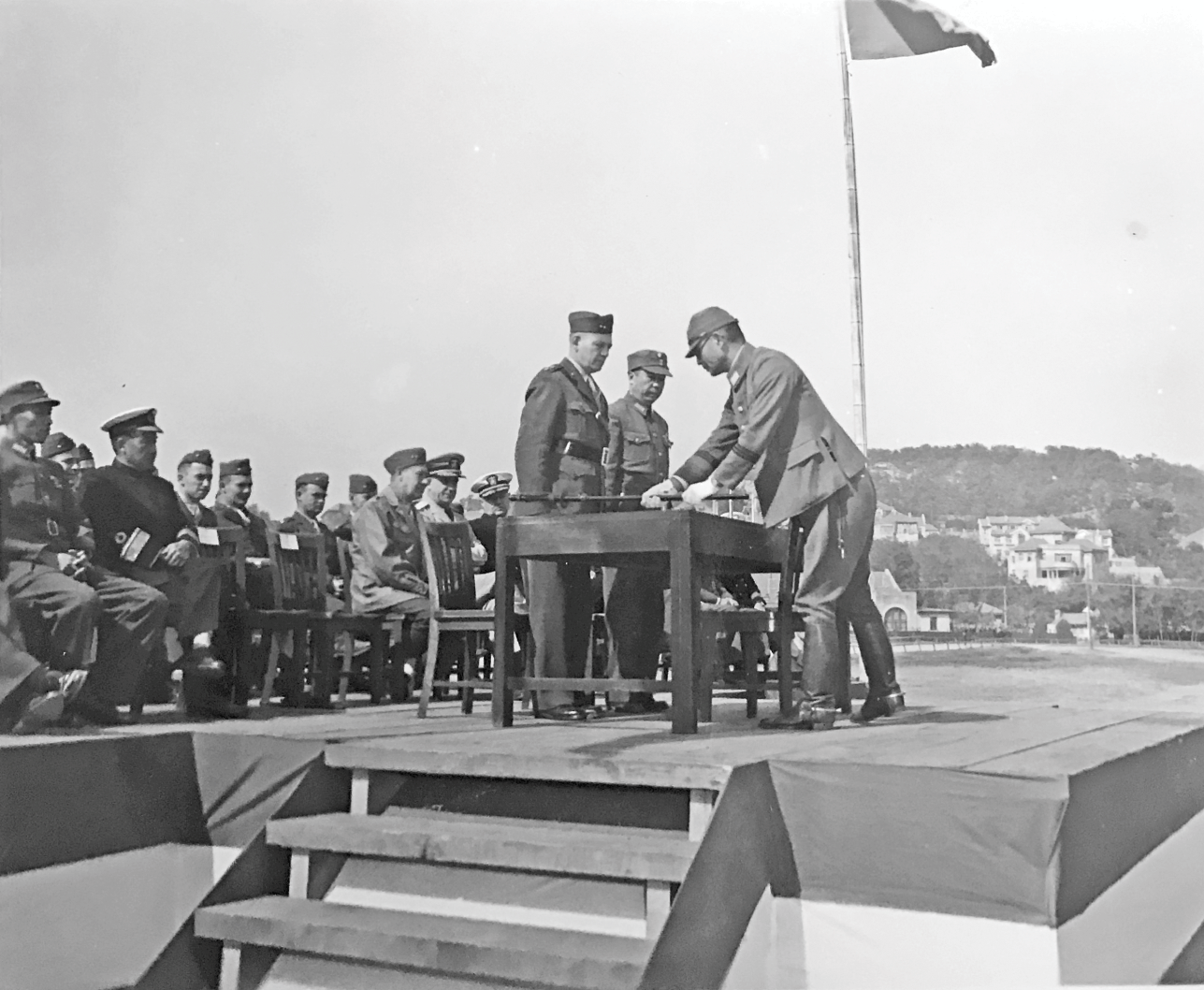

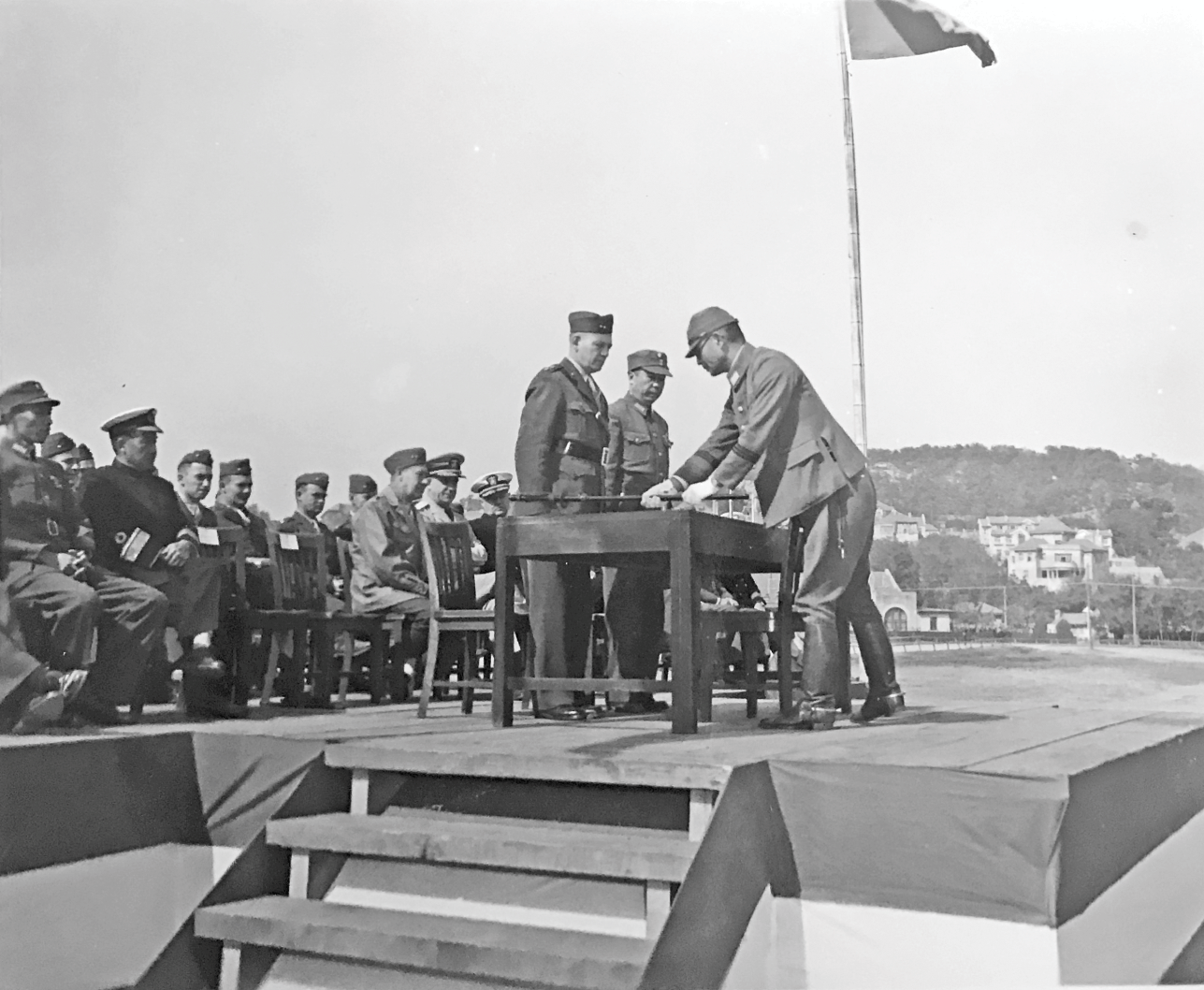

The most significant American spectacle was displayed in the formal Japanese surrender ceremonies held in Tianjin and Qingdao. On October 6, 1945, the United States Marine Corps accepted the surrender of more than fifty thousand Japanese troops in the Tianjin-Tanggu-Qinhuangdao area in front of the former French Municipal Building, now headquarters of the IIIAC. Beginning at 8:30 a.m., invited Allied guests entered and the marine guard of honor and band took their positions. Shortly before 9:00 a.m., Japanese representatives arrived in two vehicles escorted by American Jeeps. At 9:00 a.m. sharp, Major General Keller E. Rockey, commanding the IIIAC, and his chief of staff, General Worton, walked out of the headquarters and took their seats. The Japanese representative, Lieutenant General Uchida Ginnosuke, commander of the Japanese 118th Division, was led to the draped signing table, saluted the American leaders, and signed the surrender documents, ten copies in English and ten in Japanese (see Figure 1.3).37 Then General Rockey signed. Afterward, the honor guards fired a gun salute, and the marine band played the US national anthem, followed by the Chinese anthem. After another round of salutes, seven Japanese delegates removed their swords and laid them down on another long table. The brief ceremony ended in twenty minutes as the Japanese delegates were led out of the site by marines.38 Notably, General Uchida Ginnosuke wore his boots and full uniform during the ceremony with “a dozen medals tacked to his tunic,” together with his sword, and he “stood rigidly in front of their command company of soldiers.” In contrast, General Rockey, General Worton, and their subordinates, “by design and by order,” wore their “most casual khakis; no neckties, no medals, no frills.”39 Ceremonial officers who escorted the Japanese representatives sported open-collar khaki uniforms without belts or insignia, and crowds of marines stared and cheered in close distance, packing the headquarters stairs, windows, and roof.

Figure 1.3 The Japanese surrender ceremony in Tianjin, 1945. MCHD.

Figure 1.3Long description

They are surrounded by their aides. In the foreground, the Japanese representative, Lieutenant General Uchida Ginnosuke, who is facing away from the camera, is seated and signing surrender documents. A U.S. guard stands to his left.

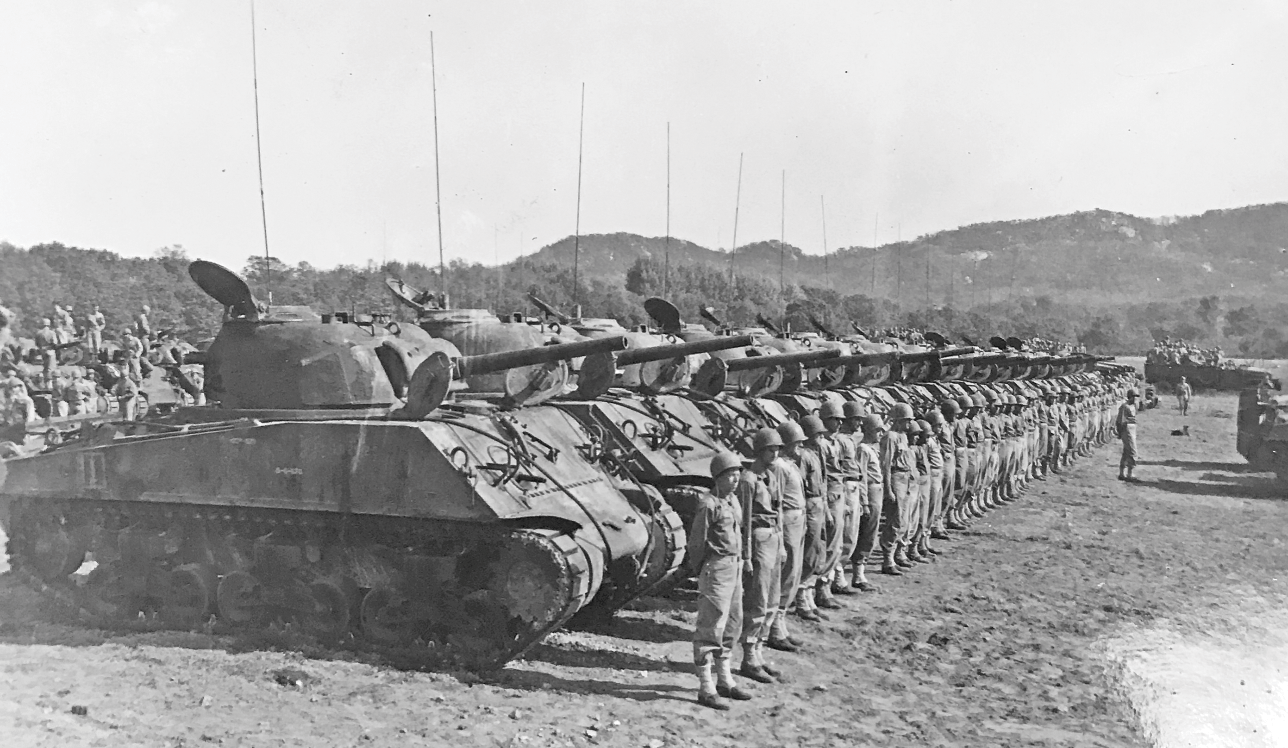

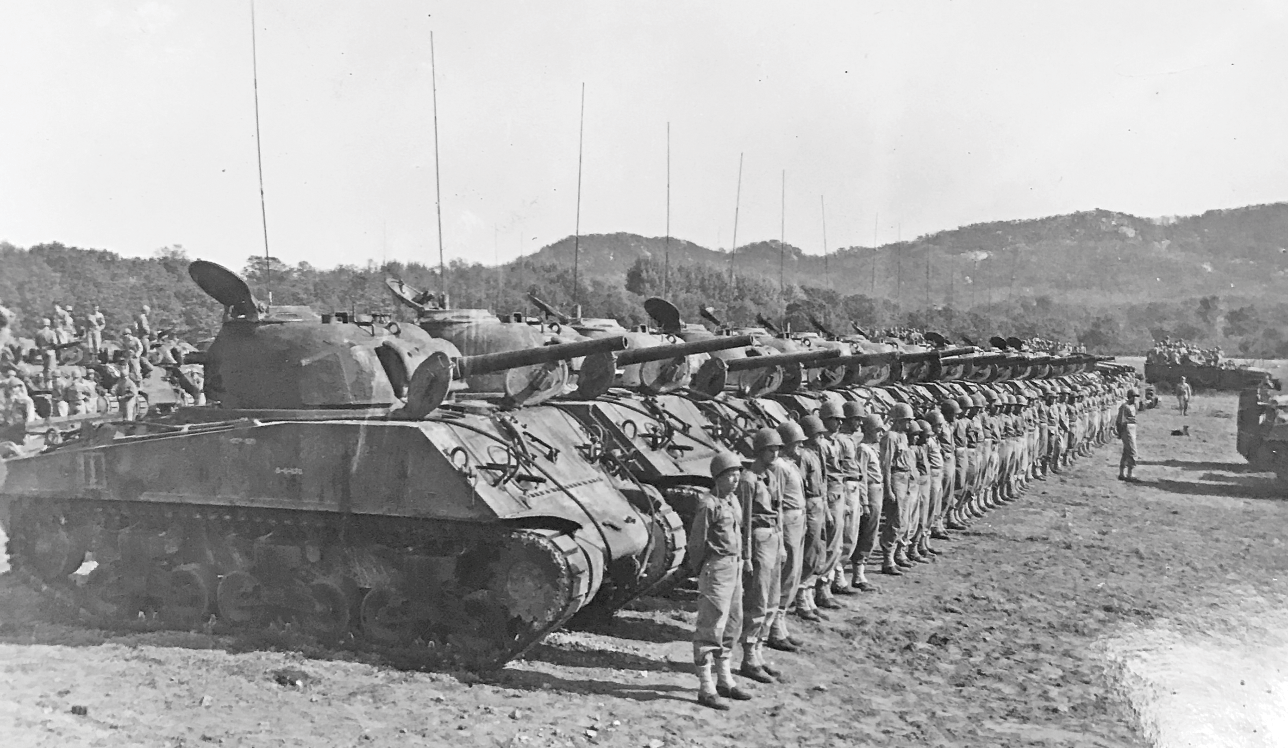

By contrast, the two-hour-long surrender ceremony in Qingdao on October 25, 1945, was a more direct show of might. At 11:00 a.m., the surrender ceremony of about ten thousand Japanese in the Qingdao garrison took place at the spacious oval racecourse that had been built during German occupation in the late nineteenth century. Flags of five nations – the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, France, and China – flew from the grandstands (see Figure 1.4). More than twelve thousand marines from the 6th Division paraded in battle dress, together with forty rumbling tanks; four hundred armored, military, and communication vehicles; and self-propelled artillery. During the ceremony, six squadrons of Marine Air Force aircraft swooped over the racecourse and hovered over the city and along the coast (see Figures 1.5 and 1.6).40 As Major General Shepherd recalled, “I turned out every man in the division and every vehicle in the division” to show “the strength and fire power of the division.”41 During the ceremony, Shepherd in his formal military attire and Lieutenant General Chen Baocang (Chen Pao-tsang), Chiang Kai-shek’s representative, were seated on the platform, while the Japanese representative, Major General Nagano Eiji, unbuckled his samurai sword and laid it across the table while bowing, an act followed by ten other Japanese delegates. Nagano then signed the surrender documents. Afterward, the division band played the national anthems of America and China, as all attendees including the Japanese officers saluted. After the signing, the entire marine division plus the air force members paraded.

Figure 1.4 The Japanese surrender ceremony in Qingdao, 1945. MCHD.

Figure 1.4Long description

A group of guests observes the scene from the platform.

Figure 1.5 China division parade in the Japanese surrender ceremony in Qingdao, 1945. MCHD.

Figure 1.6 China division parade in the Japanese surrender ceremony in Qingdao, 1945. MCHD.

The American-held ceremonies departed from previous Chinese ones through two major innovations. First, an open field was chosen, and the general public was invited to the collective witnessing, together with guests and journalists. An estimated two to three hundred Chinese surrounded the Tianjin ceremony, while one hundred thousand people reportedly gathered in the vicinity, shouting victory chants and clapping their hands.42 In Qingdao, while the Japanese delegates struggled to complete their mechanized exit as their car broke down, according to a Chinese report, “Not even racket of fighter planes overhead could drown the roar of laughter that came from 10,000 Chinese throats.”43 In contrast, from September to December 1945, the Nationalist Government accepted surrenders across China in fifteen designated districts, including northern Vietnam and Taiwan, and held ceremonies that were mostly brief and unembellished. Even the carefully choreographed and meticulously planned national ceremony in Nanjing was not open to the public and only lasted fifteen minutes for signing documents.44 Another major American innovation was to include a formal sword surrender act in the proceeding. Commanding generals saw the Japanese sword as “the symbol of his defeat” and a “token of surrender.”45 Thus, before or after signing the surrender document, the Japanese representatives formally laid down their swords on the assigned table. Chinese leaders also saw the sword as crucial to the Japanese but chose a more accommodating approach. In the national ceremony in Nanjing, the Japanese delegates’ swords were submitted in a separate resting room before entering the ceremonial space and were not photographed or recorded in the formal program. In fact, this arrangement was a result of Sino-Japanese prenegotiations. The Japanese representative was given the choice of submitting the swords or not carrying them during the ceremony.46 General Okamura Yasuji, who signed the Japanese Instrument of Surrender in Nanjing, chose the latter option.

These American shows in China might have been directly inspired by the spectacles at the Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945. On that occasion, the Japanese delegation in their ceremonial suits and uniforms arrived beneath the guns of the battleship USS Missouri and were surrounded by thousands of American sailors and marines wearing daily service clothes and plain open-collar khakis. General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, had Matthew C. Perry’s 1853 flag delivered from Maryland and chose the ceremonial spot because it was where Commodore Perry had come ashore for the first time and “opened Japan.” These symbols were intended to convey defeat and humiliation for Japan’s past deeds, as well as dismissiveness and contempt toward its future. MacArthur was determined to put on full display the superiority of American forces with an armada of 258 combat ships and a formation of B-29 Superfortresses that had brought destruction to Japan.47 This demonstration of force was an admonition to quell any potential resistance and a show of America’s new status as a nuclear superpower. Although surrender terms were all predetermined, the actual ceremony was significant as a meaning-making ritual occupying highly charged political, mental, and emotional space. Throughout Asia, American-held surrenders “relied on displays of force and potent symbols to convey the irremissibility of Allied power and impress upon the Japanese the unconditional nature of their defeat.”48

Under close scrutiny by all parties, the Act of Surrender also became an act of power transfer. “I thought of the moment as unembellished, stark history,” Walter J. P. Curley, aide-de-camp to General Worton, commented on the Japanese surrender in Tianjin, which he helped organize. “After the ceremony, we invited Chinese, British, French, Swiss, Swedish, and American officials into our III Phib Headquarters. We drank champagne, and clapped backs.”49 In Qingdao, General Shepherd recalled, he signed the articles of surrender and “had the local Chinese Commander also sign them.”50 These seemed accurate descriptions of the event except that the Chinese appeared in these American accounts as supporting characters in the background, as observing guests by invitation, and as cheering audiences of the grandiose march. The whole scene was presented or even designed as an American victory. Notably, the signing page of the surrender document in Qingdao indicated that Major General Lemuel C. Shepherd and Major General Li Yannian, Deputy Commander of the 11th Chinese War Area, were “duly authorized representatives of the Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek.” General MacArthur’s General Order No. 1 provided that the Japanese forces in China excluding Manchuria, Taiwan, and northern Indochina were to surrender to Chiang, and all Japanese forces within Manchuria were to surrender to the commander in chief of the Soviet forces in the Far East.51 However, on the cover page of this Act of Surrender, the document was said to be signed by General Shepherd “on behalf of the United States.” The surrender paper ended with this statement: “In case of conflict or ambiguity between the English text of this document and any translation thereof, the English text shall govern.”52 Ten copies of English and Japanese documents were signed on that day. Surrender did not always mean an acceptance of defeat by the signers of the official documents who might be operating in very different political and discursive spaces. As Japanese army leaders in China continued to question whether they had indeed lost the war in China or lost to the Chinese, signing the surrender paper to the Americans made the Japanese surrender in China even a less clean act.

The apparently reversed roles between American guests and Chinese hosts, as well as the explicit and implicit message of American victory in the American-led ceremonies, did not escape the eyes of the Chinese. In their own reports of these two ceremonies, local news media often profiled photos of Chinese generals inspecting American forces and portrayed the two allies equally. But bitter feelings often surfaced in personal accounts. According to the memoir of Major General Lü Wenzhen, who was leading the advance commanding team of the Nationalist army to North China and in charge of handling Japanese surrender affairs in the region, he was quite surprised when an American officer informed him that the Americans would be accepting Japanese surrenders in Tianjin instead. He questioned why foreigners would be handling such matters in China. His unease extended to the actual ceremony, where the raising of the American flag and the playing of the American anthem sparked confusion among the Chinese spectators. They felt a mix of bewilderment and dismay, wondering, “Now with Japan gone, here comes America?” The mood shifted only when the Chinese anthem started and the crowd burst into roars and applause.53 Perhaps bearing this sentiment in mind, General Lü decided to create a proper Chinese ceremony. After witnessing the Tianjin ceremony, he recommended relocating the surrender ceremony in Beijing that was to be held four days later from the modest Hall of Embracing Compassion (Huairen Tang) to the expansive open space in the Forbidden City, stating that as the “American military accepted the Japanese surrender in public, we will also hold a public one.”54 As a result, an estimated one hundred thousand to two hundred thousand locals gathered on the historic day. The ceremony was presided over by General Sun Lianzhong, the commander in chief of the 11th War Area and a war hero known for leading the Battle of Taierzhuang in 1938, China’s first major victory against Japan that provided a tremendous morale boost. Also following the example of the Tianjin ceremony, a formal sword surrender act was included in the proceeding, as the Japanese delegates turned over their swords after signing three copies of the surrender document, this time in Chinese and Japanese. There were also new inventions. At 10:00 a.m. sharp on the national day of October 10, after a spectacular band show and gun salute, a moment of silence was observed for the fallen soldiers and the Japanese representatives were asked to bow low and repent to the Chinese people. While learning from the American ceremonies, especially the creation of spectacles, the Japanese surrender ceremony in Beijing also represented an upgrade, not only in scale, but also in its insistence on public contrition. It demanded explicit Japanese acknowledgment of defeat, responsibilities, and even war crimes.

Surrender ceremonies consist of a deeply visceral encounter, a physical and symbolic exchange concerning victory and defeat, dignity and shame, agonies and forgiveness. They are moments of political and cultural reordering, “a complex configuration of social and cultural forms,” what sociologist Robin Wagner-Pacifici calls the “transfer of power and reconstruction of identity.”55 In Tianjin and Qingdao, marines put on a formidable show of force in the official ceremonies. The actual display of power took different forms, from masqueraded casualness to overt intimidation. However, the shared goal was to underscore a clear relationship between victory and subordination, contempt and humiliation. More than achieving straightforward military success, this effort aimed to showcase an American victory to ensure both defeat and domination. These ceremonies thus became not only the victorious conclusion of the war but also a rehearsal of incoming postwar politics.

These staged acts of surrender seemed to have worked like a charm. According to General Worton’s personal aide, “the American takeover and occupation of North China from then on happened remarkably smoothly.” The Japanese commander was “scrupulously cooperative, if sullen, and understood the tasks at hand,” and Japanese officers and soldiers virtually disappeared from general sight.56 Similarly, the American military in Qingdao after the ceremony supposedly “never had any trouble.”57 Diehard Japanese officers who had infamously pledged never to surrender were said to become surprisingly cooperative in following American orders. It went so well that they gained new respect from the American military leadership and became subordinates who could be entrusted with rearmament and responsibilities such as fighting Communist forces and defending marines in isolated areas. For example, General Shepherd provided Japanese troops with arms and ammunition and permitted them to keep their rifles. He explained it bluntly: “If anybody’s going to be killed fighting Communists, it’s not going to be Marines, it’ll be Japanese.”58 Indeed, the Japanese tried to stay on good terms with the Americans after the country’s surrender and occupation. Many continued to hold the Nationalists in contempt and considered themselves defeated by the Americans rather than by the Chinese. Japanese troops of all ranks in China saluted all marines regardless of rank. For the most part, they stayed in their camps and were on their best behavior around Americans.59

Staging Might: Dangerous Encounters with the Communists

On October 26, 1946, just one day after the official surrender ceremony in Qingdao, Marine Aircraft Group 32 planes began regular reconnaissance patrols to check the status of railway lines and ensure “adequate warning of any Communist move” against the city. At this time, the Communists controlled most of the coastline and vast areas of the interior in Shandong.60 These aerial demonstrations served as not only a warning to the Japanese, but also as a deterrent to the various groups of Chinese spectators, including collaborationist armies, local bandits, and especially the Communists. General Shepherd explained that the “show of force” during the Qingdao ceremony targeted “both the Japs and the Communists,” adding that “it did impress the local population when the word got out that we had this tremendous military force and they’d better damn well be good or else we’d destroy them.”61 Despite such optimistic portrayals, the actual effects of this massive display were mixed. The CCP did not really buy the American claims of dominance and tried to stage its own shows of strength. Ultimately, there was a limit to the power of American spectacles within “a Nationalist island in a Communist sea.”62

The initial attitudes of the CCP seemed cooperative in their interactions, yet these were already marked by underlying tension. In September 1945, General Worton arrived in China with an advance team, becoming the first group of Allies to arrive in North China. In Beijing, he was said to have met with Zhou Enlai, Mao’s right-hand man and a skilled diplomat. In their intense hour-long exchange, Zhou made it clear that the Communists would fight fiercely to prevent the marines from taking Beijing. In reply, Worton emphasized that he was not looking for trouble, but the battle-hardened IIIAC, backed by superior air power support, could overcome any resistance if necessary. Shortly thereafter, the marines arrived in Beijing without facing major opposition.63 The CCP also abandoned its plan to seize Qingdao because US military personnel had already landed there and refused to relinquish control. The city ultimately remained the last Nationalist city in Shandong to fall to Communist forces. Throughout the period, the CCP waged fierce propaganda campaigns against the US forces but steered clear of direct military conflicts, recognizing their superior strength. However, the American threat of force did not always deter the Communists’ actions. Their army, along with irregular forces, frequently disrupted US operations by destroying roads and rail tracks, attacking local repairmen, and orchestrating ambushes and sabotage missions. This guerrilla-style harassment, which Mao elucidated clearly in his writings, avoided open battles but posed a constant and continuous challenge and threat to the occupying forces.

Frederick W. Mote, then a young officer with the Office of Strategic Services, recorded an incident shortly after the marines’ landing that, while “in itself of little import,” symbolized “the overall situation then developing in North China.” On October 30, 1945, during a short train ride from Tangshan back to Tianjin, he was traveling with a Japanese army major when soldiers from the 8th Route Army stopped the train by placing a barrier across the tracks and firing rifles. They boarded the train, disarmed the Nationalist officers onboard, ripped off their epaulets with official insignia, and confiscated their wallets, while leaving civilian passengers unharmed and treating the American serviceman with respect. Afterward, these Communists shouted slogans, fired shots into the air, and quickly vanished into the dense millet fields. Mote, who would later earn a bachelor’s degree from Nanjing University and become a founding figure in the study of China and East Asia in America, provided a compelling interpretation of the event. He noted that although Chinese Communists at the time were “capable of no more than making an occasional, well-planned display of this kind,” this “staged event was to enhance their presence and to diminish their opponents’ dignity.” He further explained the Communists’ way of demonstrating power: These “ostentatiously ragtag soldiers were telling us that the Japanese military was no longer important, the helpless Chinese government officers could be shown utter contempt, and the Americans were a negligible anomaly.”64

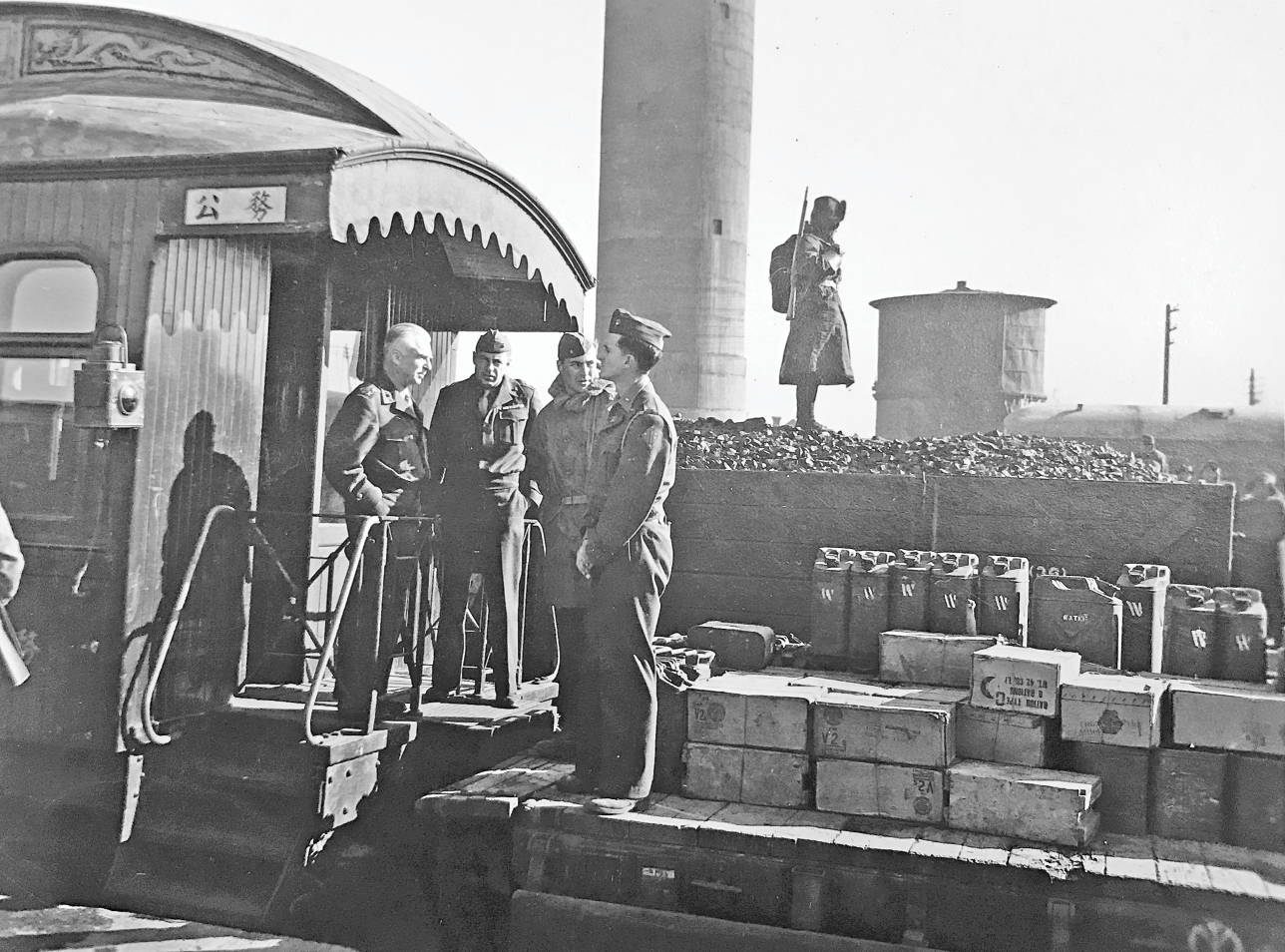

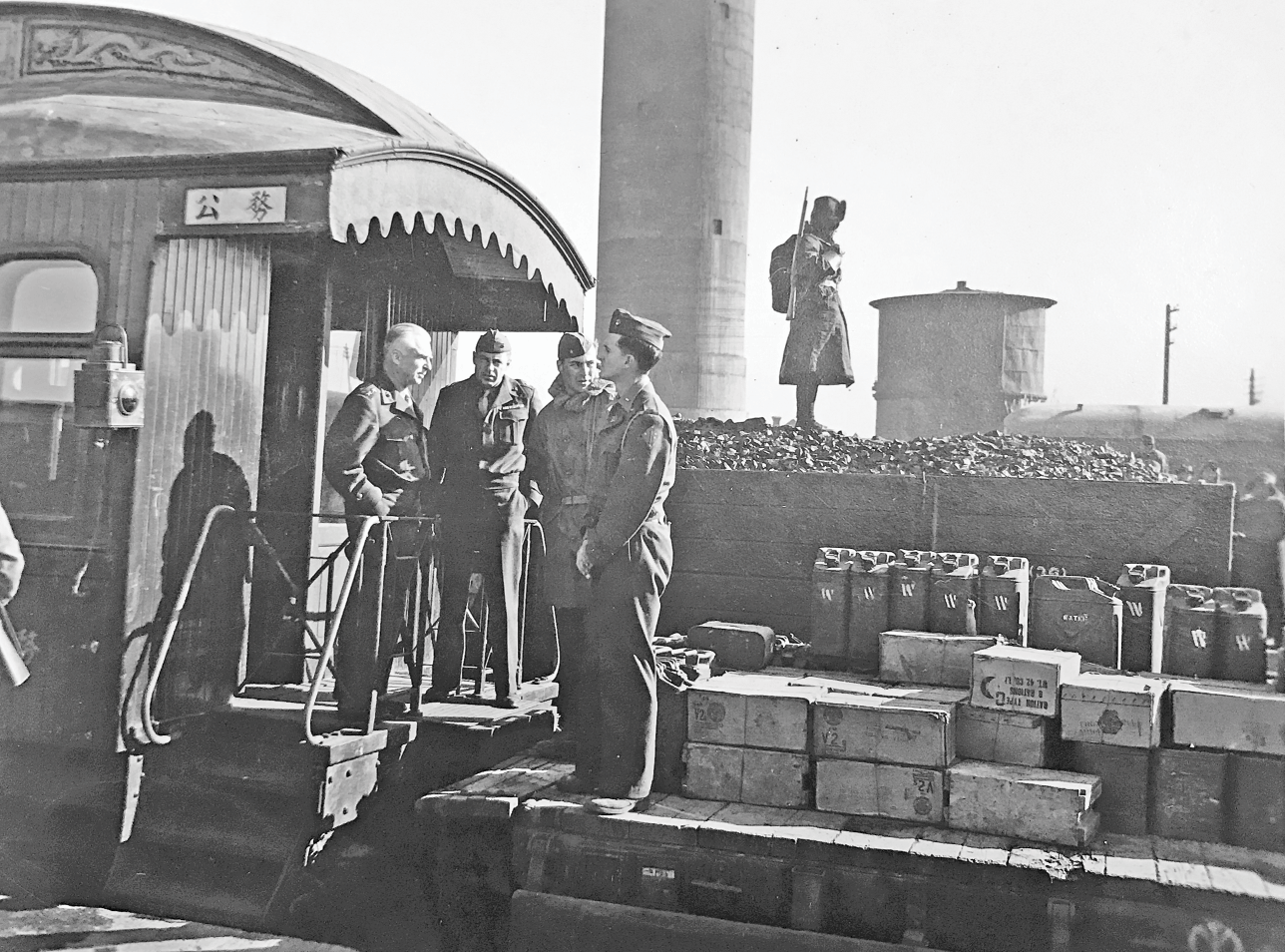

Chronic small-scale raids and intermittent conflicts were a constant presence during American routine operations. Marines “riding shotgun” on coal trains and trucks faced frequent harassment and were vulnerable to sniper fire and explosions on tracks and roads. For instance, on November 14, 1945, the train carrying Major General DeWitt Peck, commander of the 1st Marine Division, was attacked while traveling from Tangshan to Qinhuangdao. Near Guye (Kuyeh), where a break in the railroad tracks had occurred, snipers exchanged fire with the marines for more than three hours. The attack was described as “never very big,” but “enough” to prevent laborers from repairing the tracks. The following morning, fire continued, and a Chinese workman triggered a land mine that exploded, killing several others (see Figure 1.7). In response, General Peck secured permission for an airstrike on a nearby village suspected of harboring the attackers. After a warning was issued and simulated strafing runs were made, the hostile fire ceased. With the repairs expected to take days, General Peck returned to Tangshan and opted to fly to his destination instead (see Figure 1.8).65

Figure 1.8 General DeWitt Peck inspects the marines in Tangshan, December 1945. MCHD.

Figure 1.8Long description

An armed guard stands atop a pile of coal in an adjacent cargo wagon. In the background, railway station structures, including boilers and a tower, are visible.

Direct armed confrontations were rare but deadly. Between October 1945 and December 1947, there were thirteen fatalities and forty-three wounded among navy and marine personnel.66 The first major clash between Communist and American forces occurred in the Anping Incident on July 29, 1946. A marine convoy was ambushed en route from Tianjin to Beijing by approximately five hundred Communist troops.67 The convoy consisted of twenty-three vehicles carrying marines and Chinese National Relief and Rehabilitation Administration supplies. The attack resulted in three marine deaths and twelve wounded, out of forty-three American military personnel. According to the American investigation, such a heavy toll occurred because the marine personnel were “completely unaware of the premeditated danger as evidenced by the disorganized manner in which they deployed and defended themselves.”68 The Anping Incident caught the attention of the highest leaders in both nations and thereby left a rare collection of detailed archival materials unmatched by other similar incidents. As it occurred in the middle of the Marshall Mission to China, all three sides of the Peiping Executive Headquarters conducted an investigation of their own but reached opposite conclusions.

Both the Communists and the Nationalists tried to exploit the incident for their own political gains. The Communist side insisted this was an American intrusion into the “liberated area,” together with the Nationalist forces, and that the Americans fired first. Although their later investigation reports revealed new information that local Communist forces initiated the attacks without the prior knowledge of the Yan’an authorities, the Communist leadership did not change its initial claim and instead continued to frame incidents like Anping as evidence of American direct assistance to the Nationalist Party in the civil war. The Nationalists, on the other hand, hoped to stir anti-Communist sentiment and ease tension from the killings of anti–civil war democratic leaders Li Gongpu and Wen Yiduo about two weeks prior to the Anping Incident.69 Under American pressure to downplay the incident, Nationalist media did not launch a full-scale propaganda war. However, Chiang Kai-shek could not ignore this opportunity and instructed subordinates to organize a series of public memorial services and events. On August 2, several Nationalist high officials attended the American memorial in Tianjin, and Chiang himself sent condolences to General Rockey to express “deep sympathy and regret over this loss and suffering.”70 Another public memorial service was organized by the Tianjin municipal government and attended by several thousand locals. The Nationalist Government instructed various local social organizations to send condolences and demand the punishment of the criminals.71 As Theodore H. White and Annalee Jacoby, correspondents for Time and Life in China, described in their best-selling book Thunder Out of China: “Communist guerrillas, who had watched American marines league with Kuomintang troops to bar them from the railway lines for so many months, grew trigger-happy. … The Kuomintang greeted the incident with sedate good cheer as finally sealing Communist-American enmity; the Communists immediately unloosed a barrage of propaganda denouncing America.”72 In the end, with fake evidence from both sides, General Marshall observed, “Delaying tactics, vicious propaganda, et cetera, have been the order of the day.”73 Indeed, the joint Nationalist-Communist-American investigation of the Anping Incident broke down in September, soon followed by the collapse of the peace talks.

Another major attack occurred in less than a year. In the dim light of dawn on April 5, 1947, four well-organized groups of armed Communist forces, roughly three hundred troops assisted by another three hundred locals, attacked the Xinhe (Hsin Ho) ammunition dump near Tanggu in Hebei Province. The little-known attack resulted in five marines dead and sixteen injured, the vast majority being the guards. Twenty-eight marines were on patrol at the arsenal at the time while a total of six hundred marines were stationed in Tanggu. The ambushing forces led by Wu Hong (Woo Hung) from a local branch were reportedly well equipped, using a mixture of arms, including Japanese and Soviet automatic weapons. After the successful raid on ammunitions, they burned down the dump when the marine reinforcements arrived.74 In fact, it was not the first time the 1st Marine Division at Xinhe was attacked by locals led by Wu Hong. On the night of October 3, 1946, “dissident forces” attacked the same ammunition supply point. A private on guard in the sentry tower was fired upon, followed by several hundred Chinese men armed with rifles and three automatic weapons and dressed in nondescriptive blue-gray coats with leggings, resulting in one marine wounded. Afterward, commanding general S. L. Howard recommended that the commander of the Seventh Fleet file an official protest to Communist leader Mao Zedong, demanding the responsible people be punished and thirty-two cases of stolen US ammunition returned.75 The request presumably was not met, as the second attack scaled up in just half a year.

More common than the aforementioned major incidents were the ever-present impromptu or organized attacks. For flyers conducting extensive patrols to provide intelligence, cover, and support for ground troops, their reconnaissance aircraft frequently landed with bullet holes in their fuselages. Although MAG-32 bombers flew well above the range of Communist small arms, the constant risk of being shot at, crashing, or captured remained a persistent threat.76 For marines stationed in the middle of a “hornet’s nest,” danger was constantly looming. Lieutenant Simms was in charge of a remote detachment in Hebei Province, which consisted of eighty troopers tasked with protecting the bridges and railway tracks. In March 1946, they were caught between the Nationalists and the Communists in the area, literally in the heavy crossfire.77 Sledge recounted a typical “incident at Lang Fang,” an unwalled village of about five hundred people located along the railway line between Beijing and Tianjin. Forty marines under the command of a lieutenant were sent to protect the division’s radio relay station and stayed inside a walled compound with barbed wire on top of the parapet. They were surrounded by a variety of troops, ranging from friendly to hostile, “all armed to the teeth and vying to fill the power vacuum resulting from Japan’s surrender.” On the night of October 26, 1945, his company was caught in a fierce fight between several thousand collaborationist troops and members of the Communist forces with eighty-one-millimeter mortar shells. The American commanding officer eventually had to send the Japanese troops to guard the railroad station instead in order to avoid involvement in the conflict.78 In the words of White and Jacoby, “The United States marines, the Kuomintang, the former puppets, and the Japanese army, in one of the most curious alliances ever fashioned, jointly guarded the railways against the Chinese partisans … Our flag flew in the cockpit of a civil war.”79

To live in isolated areas in North China, especially extended outposts close to Communist-controlled territories, was a lonely and perilous affair. Sometimes, accidental encounters could turn hostile. On December 4, 1945, two marines hunting rabbits were shot by suspected Communists near Anshan, forty miles southwest of the marine-held city of Qinhuangdao. One private was killed and a corporal survived by feigning death, despite being shot in the leg while lying on the ground. In response, a light infantry force was dispatched to a small village just a mile southwest of Anshan to confront the gunmen, issuing an ultimatum: “to surrender the murderers within a half hour” or the village would be shelled. When the time expired, the marines fired “24 60-mm mortar shells” toward the Chinese village.80 Afterward, The Washington Post published a critical editorial titled “Semper Fidelis,” the motto of the United States Marine Corps, which began with a question: Is it to “the tradition of American justice” that “the United States Marines are forever faithful”?81 A. A. Vandegrift, Commandant of the Marine Corps, responded by sending a letter to the editor and publisher, protesting this portrayal. He clarified that the gunfire was not directed into the village but into the open ground before it, breaking two windowpanes without causing any bloodshed. Vandegrift defended the actions of the marine officer in charge, explaining that his purpose was twofold: to coax the village residents into the open for questioning and searches for firearms, and “to remind the community, which appeared to him to be harboring the assailants, that force was available and would be used, if necessary, to prevent assaults upon Marines.”82 Although opposed to the continued presence of marines in China and critical of Chiang Kai-shek, the four-star general – who had served in Tianjin and Beijing in the 1920s and 1930s – felt compelled to defend his men and the Corps in the face of public criticism. The editorial, however, critiqued these actions, noting that to the Chinese, the American act of taking the village as a collective hostage and firing at it resembled the recent atrocities committed by Japanese troops – ironically, the very forces currently facing trial in American military courts. Furthermore, the editorial argued that this show of force, intended to “‘civilize’ these stubborn ‘natives,’” failed to achieve its aim.83 At the end of the ultimatum, not a single villager emerged. Four days later, on December 11, The New York Times reported another incident under the alarming headline “U.S. Marine Is Shot by Chinese Civilians.” The article detailed how an unarmed marine sergeant had been shot and wounded by three Chinese people he encountered on the outskirts of Tianjin. According to the headquarters’ report, the sergeant, who was on horseback, smiled and greeted the civilians. In response, they also smiled before drawing pistols and firing.84 It was only a logical speculation that the second group of gunmen were inflamed by the earlier shelling of the North China village.

The deadly confrontations involved life-threatening situations and chilling details. But more often, marine “intruders” in Communist-controlled areas were fired upon, with some captured and later released. The length of their detention varied, depending on the success of their rescue missions, which in turn was contingent on the larger political environment, local dynamics, rescuers’ maneuvers, and sheer luck. In December 1945, photo planes sent from Okinawa to Qingdao crashed en route and three crew members were captured in northern Shandong. Thomas E. Williams, an intelligence officer, led a successful mission of five men and later received a Bronze Star for rescuing three American aviators from the Communist territory. Williams attributed his success to the rapport he established over friendly and elaborate talks, meals, group photos, and most importantly drinking a local brandy together. He painted a rosy picture of local Communist captures, and the two sides seemed to have eventually established a set of “working relations.” Several Communist officials even went to Qingdao with Williams, followed by other members who brought back an injured aviator, carrying him on a litter, as well as the bodies of ten marine aviators who had been killed in the crashes. The deceased were transported in elaborate Chinese caskets, their bodies having been carefully prepared by an undertaker.85

Another successful operation involved seven members of a detachment guarding bridges on the Beijing–Shenyang Railway, a critical route the Nationalists used to move troops to Manchuria against the Communists. On July 13, 1946, these leathernecks from the 7th Marines were captured and held for eleven days by Communists in North China. The group had gone out to procure ice from a nearby village to celebrate a private’s scheduled homecoming and upcoming twentieth birthday.86 While one member escaped capture by hiding in the icehouse, the marine search team was unable to locate the captives, who had been quickly relocated. The seven marines were eventually released on July 24 by the Communists, who demanded the Americans apologize for their unlawful entry into the liberated area.87 Despite the ordeal, the marines later described their detention experience as “prisoners’ adventures” that involved rough rides on mule carts “touring” Communist areas no one had visited before. One marine even said, “We would have had a fine time – if we hadn’t been so scared.”88 A New York Times article, filled with vivid details, described how local Communist leaders, with a sense of sincerity or naivety, propagated their message to the American servicemen and even tried to convert them to the Communist cause. An interpreter named Mr. Li, a graduate of Princeton University, spent most of the morning lecturing them on the accomplishments of the Communist government. After discussing the political situation of China with the American captives, the CCP commissar further reminded them how his unit had saved and smuggled the crew of a crashed B-29 through dangerous Japanese lines back to their interior base three years earlier.89 Upon their release, the commissar invited the marines to a fourteen-course meal, which ended with a group photo. Despite these “good gestures,” the American captives were said to have maintained their victor identity and appeared “ungrateful” in the eyes of the Communists. In a “friendly game,” the marines played basketball with CCP soldiers who carried pistols. The American team, including two loaned men from the Chinese side, “lost the game” and “a little ‘face’ at the same time.” But the former captives insisted that they saved some face after their dog, now also a captive, won every fight against the dogs the Communists brought in for a match.90

Rescue missions present some of the most vivid and colorful accounts of Chinese Communists in marine narratives. Many of these operations were later recounted by GIs with a sense of adventure and humor. Compared with the evil Fu Manchu in the colonial era or the insidious brainwashing captors in The Manchurian Candidate during the height of Cold War hysteria, Chinese Communists in these personal tales and media reports appeared more human, often shifting between friends and foes, hosts and captors.91 However, official documents reveal that these encounters often carried high stakes and great risks, especially after the civil war escalated and General Marshall’s mediation mission failed. Rescue efforts became more difficult, requiring high-level, lengthy negotiations. For instance, on December 25, 1947, a Christmas hunting party of marines from Qingdao exchanged fire with local Communist forces about thirty miles outside the city. The clash left one marine dead and four captured, who were then held for nearly one hundred days before their release on April 1, 1948. As in previous cases, the captives were subjected to elaborate “educational lessons” through lectures and readings, and by eating, living, and traveling together with their captors. Local Communist authorities did not believe the Americans were on a simple recreational outing so far from their base and accused the marines of supporting the Nationalist war effort and engaging in “aggressive activity of imperialism.”92 They also demanded an apology and admission of responsibility from the Americans, along with acknowledgment of US complicity in the civil war. Rather than seeking ransom, the Communists aimed to negotiate with high-level American officials on terms that positioned the Communists as an equal and legitimate government. Although the American military generally denied these allegations as false, these incidents – along with the resulting personal, military, and diplomatic exchanges – directly questioned the efficacy of the American tactic of deference and claim of dominance in the region.

Not all incidents ended up as harmless “touring” adventures. Communist forces were seen and felt as a real threat to the lives of marines tasked with key occupation duties of guarding munitions, coal mines, bridges, railroads, and warehouses. Some soldiers expressed dissatisfaction that these incidents usually received scant attention and were reduced to “a bland, colorless paragraph in a routine report.”93 Wary of their political implications, high-ranking US officials downplayed such events and remained largely silent in their public statements. In the aftermath of the Anping Incident, for example, General Marshall urged restraint and low exposure on the American side. He was concerned with how both the Communists and Nationalists exploited such incidents for their propaganda purposes.94 Similarly, following the shooting of two marines in Anshan, an area where “Chinese irregulars previously have fired on marines guarding coal train,” General Rockey declared to the news agency that “he believed it had no military significance.”95 Shortly after the second Xinhe dump attack, marines quietly withdrew from the dump and turned the ruins over to the Nationalist army rather than retaliating. In general, the US military did not engage in overt confrontation or retaliation following these clashes. The direct use of force against the CCP was restrained, despite superior American firepower that included a formidable combat force of tanks, fighter aircraft, artillery, and infantry directly from the Pacific. Following clashes with the Communists, marines stationed close to “bandit areas” were often instructed to be on high alert, stay neutral in local confrontations, and open fire only if being attacked or their mission was directly threatened. Instead, the strategy of consolidation was adopted to minimize the exposure of marines to vulnerable positions. This approach involved consolidating forces in more concentrated locations and relocating soldiers from stretched railroad lines and remote areas to major cities under Nationalist Government control. In North China, the American military added barbed wire and extra defenses, increasing regular patrols in barracks and camps, and renewing safety drills including oversized tanks and marine fighters. These practices were meant to be a show of force to the hostile groups watching, but they did not always work.96

Despite deliberate silence from the high-level leadership, marine newspapers reported incidents of Communist raids on camps and harassment along train tracks, as well as “kidnapping incidents” when GIs entered areas controlled by the Communists.97 Back in the United States, news of the dire situation in China and GI casualties reached a wide audience through both mainstream and small-town newspapers. A combat correspondent for the Tulsa Daily World in Oklahoma reported that marines barely escaped sniper fire over their heads even while watching movies, as well as faced frequent highway ambushes. The Chinese Communists aimed to “create enough ‘incidents’ to arouse American public opinion.”98 Another newsman from the Hickory Daily Record in North Carolina wrote about Bessemer City native Private First Class William R. Rabb, who was one of the two sentries on guard duty during a well-planned Communist attempt to destroy a large ammunition dump. The explosion was described as producing “a great burst of orange light and a thundering roar that smashed windows for five miles around.”99 Through vivid accounts like these, the American public closely followed developments in China, and many became increasingly alarmed. At home, wives and mothers bombarded their congressional representatives with letters and requests to “bring the boys back home.” Leftist media, labor organizations, and citizen groups campaigned for the withdrawal of the US military from China and rallied against America’s imperialist stance in postwar Asia.100 For instance, from November 11 to November 30, 1946, the Division of Public Liaison in the State Department received a total of 182 public letters concerning China, of which 95 percent urged the “withdrawal of troops and termination of all aid to Chiang.”101

Veterans, now no longer restrained by wartime censorship laws, wrote and protested against their prolonged stay long after WWII had ended. One army officer wrote to his sweetheart back home, lamenting, “Having defeated the Japanese, the troops do not like being played as pawns in this Chiang-Mao political game.”102 Another marine private expressed, “We had survived fierce combat in the Pacific, and now none of us wanted to stretch his luck any further and get killed in a Chinese civil war. We felt a terribly lonely sensation of being abandoned and expendable.”103 Frustrated GIs signed petitions to General Wedemeyer and the Congressional Investigation Committee on Demobilization, asking the pointed question, “Why are we here?” They organized mass meetings outside the China Theater headquarters in Shanghai, “mirroring the same activities in Yokohama, Tokyo, Manila, Guam, Saipan, Honolulu and Frankfort.”104 Around the world, thousands of veterans took to the streets from V-J Day to January 1946, protesting the delayed demobilization. On Christmas Day alone, twenty thousand troops marched in protest in Manila, joined by others from across the Pacific. Ultimately, clashes with Chinese Communists, causing harm to American soldiers and Chinese villagers, exacerbated the already low morale and public opinion back home.105

As for the CCP, it remains unclear how much its central leadership at Yan’an knew about the planning of local armed conflicts with the American forces. Most of the smaller skirmishes are still little known today due to a lack of investigations or access to classified records. It seems that CCP forces had orders to avoid open hostilities for the most part, but local troops sometimes acted more aggressively and on their own. In the Anping Incident, for example, Zhou Enlai, who was representing the Party in the ceasefire negotiations in Beijing, only found out that it was a local Communist initiative in the later stages of the investigation but chose to continue the cover-up.106 An armed direct clash with the American military in the middle of the peace talks was not in line with the Communist policy, which did not want to provoke the Americans, but rather preferred a neutralized American position. It is thus more likely, as Marshall insightfully pointed out, that the incident occurred because local forces had been energized by the powerful Communist anti-American campaign that linked the American military presence to assisting the Nationalists in the civil war. Once launched, the trajectory of propaganda did not always adhere to the official Party line. Individuals mobilized by the propaganda might take initiative on their own, as in the Anping ambush and the killing of John Birch, an American missionary turned soldier.107 Overall, the Communist Party had been protesting against the Americans’ actions of “interfering with Chinese sovereignty and participating in the Nationalist army’s attack of Communist-controlled area.”108 Mao’s interview with American journalist Anna Louise Strong in August 1946 also sent a clear message regarding the American show of force: “The atomic bomb is a paper tiger which the U.S. reactionaries use to scare people,” and the Americans are terrifying only “in appearance … but in reality they are not so powerful.”109

Staging Justice: Juridical Sovereignty and Tensions with the Nationalists

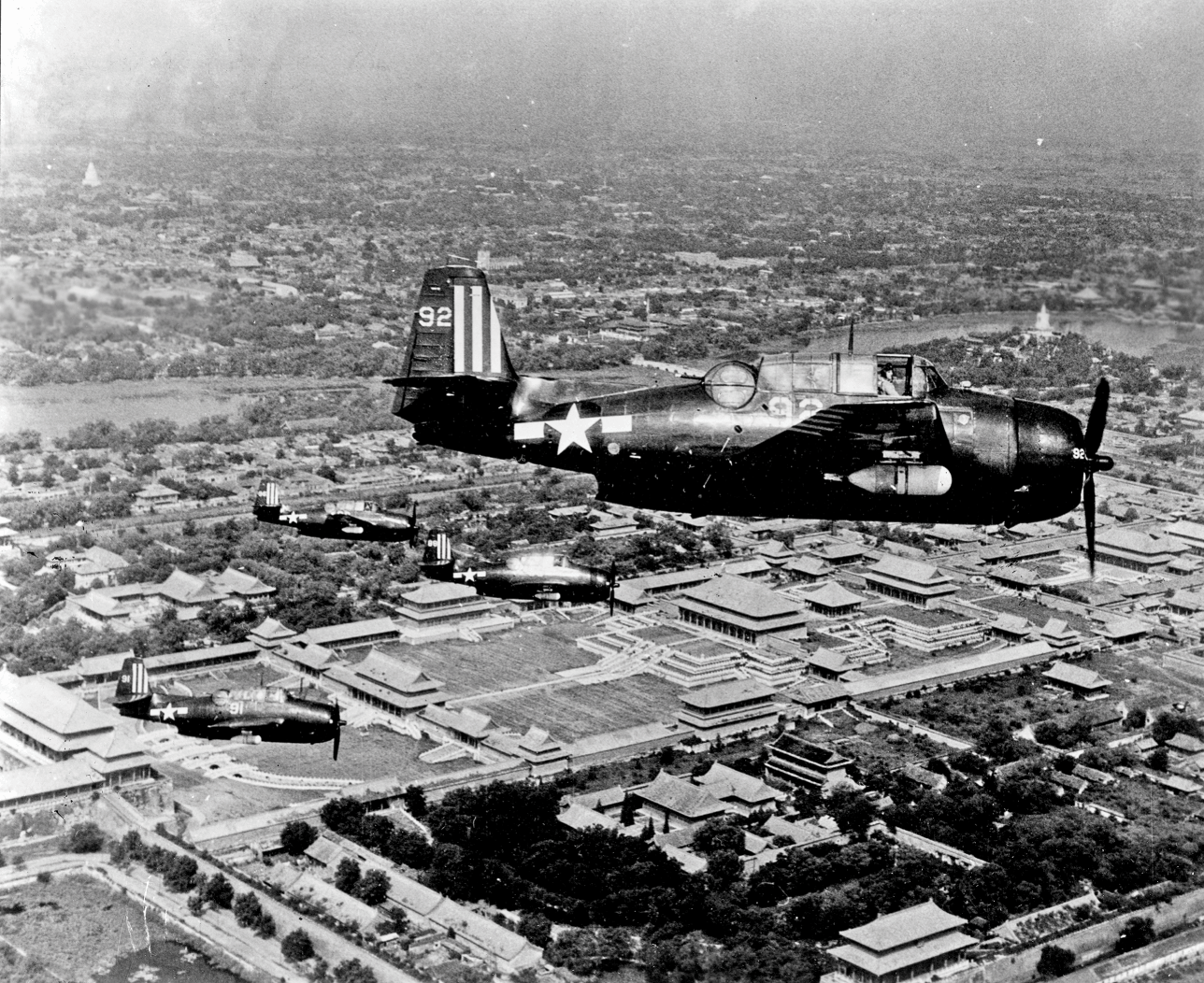

On the Fourth of July 1946 the air arm of the marine garrison celebrated the American national holiday by staging a majestic aerial display over Beijing and adjacent Communist territories. As Graham Peck observed, this “show of force” on America’s Independence Day ironically emphasized to the Chinese that “for the time being they did not have full independence to decide their own future.”110 This dramatic demonstration of power, while aimed at hostile groups, also had significant implications for the Nationalist allies, who increasingly saw these spectacles as an infringement on Chinese sovereignty (see Figure 1.9). This sentiment had already surfaced during the American-led Japanese surrender ceremonies, where Chinese leaders felt the Americans had overstepped their roles as invited guests. The sentiment became even more pronounced as Americans took charge of adjudicating Japanese war crime trials on their own, escalating tensions at the governmental level.

Figure 1.9 Navy carrier planes in a “show of force” flight over Beijing with the Forbidden City in the background, September 1945. NARA.

Almost immediately after the Japanese surrender, the American military started to arrest and adjudicate war criminals in China, three months earlier than the actions conducted by the Chinese government.111 The US Military Commission was convened by Lieutenant General Wedemeyer to try “persons, units and organizations accused as war criminals in this theater.” Over the course of these proceedings, a total of eleven cases were brought against the Japanese involving seventy-five defendants, sixty-seven of whom were convicted and ten sentenced to death. From January to September 1946, forty-seven Japanese war criminals were detained and tried by the US Military Commission in Shanghai.112 While conducting military operations to liberate the formerly Japanese controlled areas, American forces also performed a “mission of justice” by showcasing war crimes trials in China. In the name of reciprocity, the American military not only enjoyed exclusive jurisdiction over its own members, but also extended its independent jurisdiction over a variety of so-called war crimes cases involving Japanese soldiers, German civilian residents and American civilians in China, and Taiwanese POWs. This lesser-known mission provided a window into the US system of law and order in the postwar world. To achieve American standards of justice, the military staged victory and retribution – but at the cost of China’s sovereignty and the Nationalist Government’s legitimacy.

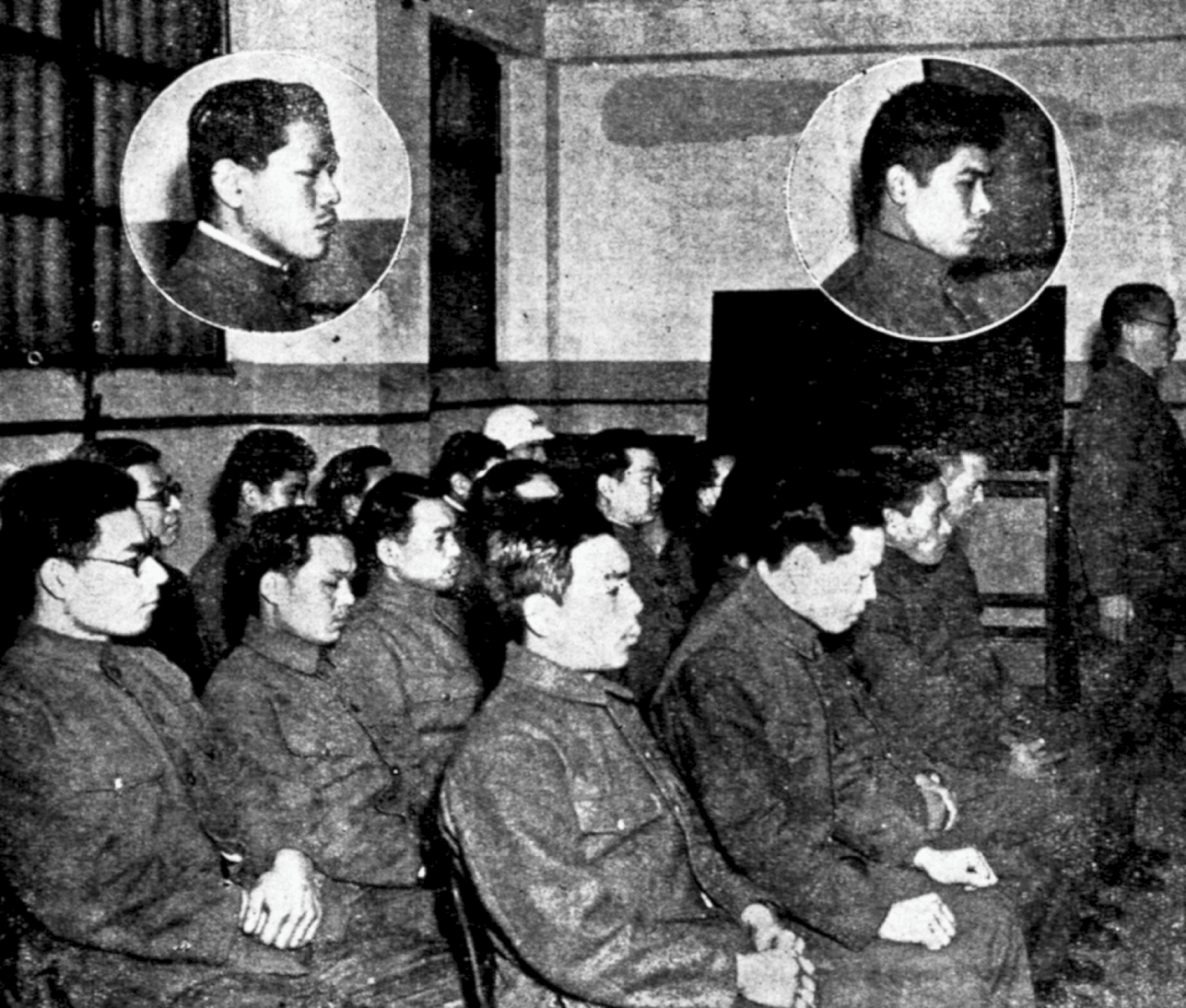

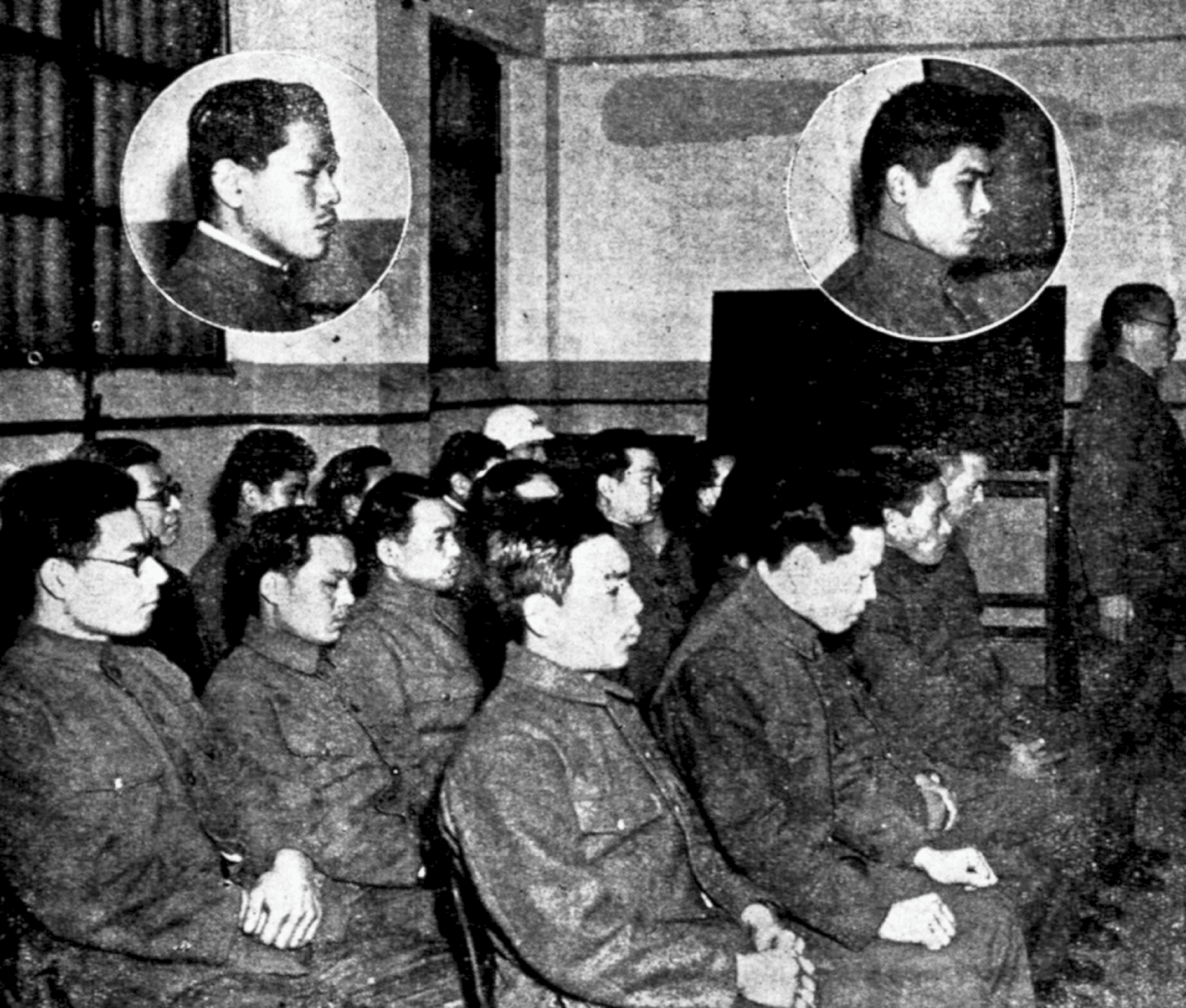

The American trial in China began in January 1946 with the sensational Hankou trial, in which eighteen Japanese were charged with the torture and murder of three downed American aviators in December 1944 after their bombing mission over Japan. Of these eighteen, five were executed, including Major General Masataka Kaburagi, chief of staff of the 34th Japanese Army headquartered in Hankou (see Figure 1.10). This became the first war crimes trial held in China and attracted attention from major Chinese and English media outlets.113 The public spectacles took place in the courtroom of the US Military Commission, located on the top floor of Tilanqiao Prison, also known as Ward Road Jail. Built by the British in the early twentieth century, this massive panopticon-like jail was the “largest prison in the Far East,” surpassing the infamous Sugamo Prison that housed war criminals from the Tokyo Trial. In a newly whitewashed room, two Chinese witnesses testified that at least one, and possibly all, of the three B-29 crewmen were burned alive by their Japanese captors. These testimonies recounted a harrowing story of beatings, torture, and a “hate parade” during which the victims were stoned and doused with water in the streets before being carried into a crematorium and thrown into the blazing ovens. Grim relics from the cremation were introduced as evidence, including “three charred belt buckles and a good luck charm.”114 General Claire Chennault, who commanded the 14th Air Force in China and directed a retaliatory air raid on Hankou, attended the hearing as a special guest, bringing further spotlight to the case. An American pilot who survived captivity as a POW in China flew back to testify, adding not only strong evidence but also emotional weight to a trial that garnered significant publicity and empathy.

Figure 1.10 Japanese defendants in the Hankou trial, featuring Major General Masataka Kaburagi standing, February 1946, Shanghai. The China Press.

Figure 1.10Long description

Major General Masataka Kaburagi stands on the far right of the picture, while the left inset features a magnified face of Private Yosaburo Shirakawa, and the right inset shows Sergeant Koichi Masuda. Sergeant Major Shozo Masui and Warrant Officer Tsutomo Fujii sit in the front row closest to the camera.

Initially, the appearance of justice seemed well maintained through procedural transparency. In the public trial, both prosecution and defense teams presented a trove of evidence gathered during pre-investigations, and witnesses from all sides were called to testify. Vigorous debates took place over the evidence and testimonies presented. However, one problematic issue was soon raised by the defense, who challenged the US jurisdiction over the Hankou trial. The defendant’s counsel, Major Levin, filed a “special plea” questioning the jurisdiction of the Commission, providing the following two reasons: (a) “The United States Government has not established a Military Government in China for the purposes of occupying territory therein.” (b) “The United States is not administering Martial Law in China. Second, The United States Government does not have rights of extraterritoriality in the Republic of China.” In opposition, the prosecutor claimed, first, that the accused were considered war criminals and therefore the Commission had jurisdiction over them pursuant to the order of the China Theater. Second, citing the examples of the Philippines and Japan, he argued that “neither military or martial law is a prerequisite to the appointment of a military commission.” In short, the prosecutor stated that the commission had jurisdiction to try war criminals in the custody of the US military authorities; it was not bound by territories. Consequently, the Commission decided to side with the prosecution and denied the defense’s motion.115

Prosecuting cases of atrocities against US soldiers might have presented a more straightforward scenario. The punishment of the “Japanese devils” who tortured and brutally murdered American flyers by American judges seemed fair, evoking fresh memories of the Chinese sufferings, for example, in the notorious Nanjing Massacre. However, in the 1946 case of a major German spy ring known as the Ehrhardt Bureau, the issue of jurisdiction was once again brought to the forefront during the trial. This time, it provoked direct scrutiny and questioning from the Chinese side. In this proceeding, twenty-seven German civilian residents in China were accused of espionage and war crimes. Although the Germans allegedly committed their crimes in China and were apprehended in China, they were tried by the Commission on the grounds that they had committed war crimes against the United States.116 The defense counsel, L. C. Yang, argued that “the War Crimes Commission had no jurisdiction to hold the trial” as these German nationals were still residents of China, and the accused came under Chinese law instead. In response, the prosecutor, Lieutenant Colonel Jeremiah J. O’Connor, stated that “the crimes were against International Law and thus do not fall under the jurisdiction of any local domestic courts,” and the trials formed part of military operations undertaken with the complete agreement of the Chinese government. During the exchanges, he added that “it appeared that the Chinese were suffering from lack of facilities and personnel to undertake such trials, but he personally could recommend an able volunteer. (Laughter).”117 The laughter, as reported by North China Daily News, was meant as a reaction to the American officer’s “humor.” But the accusation of the Chinese “lack of facilities and personnel,” and by extension, the overall incompetence of the legal system was offensive to Chinese elites who had made decades-long efforts to reform the system and fight for China’s international status. It is true that qualified Chinese personnel trained in international law remained lacking. For example, the Chinese representatives failed to prepare sufficient-quality evidence in the Tokyo Trial convened on April 29, 1946. There was also a shortage of food, coal, medical care, and facilities for Japanese prisoners in China, and more broadly, for nearly all ordinary Chinese people at the time. As a result, the Allied Powers in Japan would not extradite many main culprits to China but preferred to seek justice through American-led trials in Japan.118 But such a public comment at the historic Tilanqiao Prison, masqueraded as humor, also reflected lingering Western distrust of the Chinese legal system, what some scholars have called “legal Orientalism.”119 Notably, in the Chinese government version of the news report, the American prosecutor’s statement of recommending an “able volunteer” was translated as “Mao Sui zijian,” referencing the legendary character Mao Sui, a loyal retainer who offered his humble service to his lord during the Warring States period. This translation turned the American into a devoted guest and subordinate.120

The American “volunteer” in this case might be more able, but was an uninvited one. Compared with the Hankou case, with which Chinese elites could more easily sympathize, these trials of former Axis Power citizens roused direct critiques of the Americans interfering with Chinese sovereignty. Chinese society saw these German civilian nationals, generally grouped under the crime of espionage, as different from Japanese military personnel who committed brutal crimes against individual American victims, especially heroic flyers. Professionals opined that these Germans accused of espionage should not fall under the jurisdiction of the United States Army Forces in the China Theater, but rather the Allied forces in the China war zone or the Chinese government. Overall, the American military in China during the war, when these crimes were supposedly committed, was under the command of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. If these cases concerned major interests of America or other Allied nations, they suggested, China’s Ministry of National Defense could organize a special mixed court consisting of Sino-American military tribunals, with a Chinese judge presiding.121

The unresolved legal issues and disregard of Chinese jurisdiction undermined the projected sense of American justice and strained relations with the Chinese government. Tension arose as early as January 21, 1946, when the former German ambassador to Japan, General Eugen Ott, was brought to Tokyo as a friendly witness at the request of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers in the war crimes trials. After Adolf Hitler had dismissed him from his post as the ambassador to Japan, General Ott had lived in China since 1943 in an unofficial capacity.122 In early May 1946, Ott returned to China to visit his ill wife, all arranged by the US military without seeking Chinese permission. On May 6, China’s Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs queried the American embassy on Ott’s visit to China, expressing “some resentment over failure of American military to comply in this instance with Chinese regulations governing admission of aliens.” He stressed that “the fact of German general traveling around country as ‘guest’ of American army was embarrassing to Chinese Govt.” On May 11, Robert L. Smyth, the chargé d’affaires, telegrammed the State Department that “our military have made [a] tactless mistake, perhaps essentially unimportant but certainly unfortunate at this time when [the] Chinese are very conscious of their sovereign rights.” Perhaps because he included General Marshall in the correspondence, staff from the United States Army Forces in the Pacific under the command of MacArthur justified their actions by citing previous memorandums from the State Department. The memorandums initially had suggested that the case was not “one of importance requiring any special attention,” and after the Chinese government’s complaint, explained that “the reported disregard of Chinese regulations was unintentional.” Major General Ray T. Maddocks, the chief of staff of the United States Army Forces in the China Theater, also justified the situation by stating, “the Chinese [are] represented on the International Tribunal at Tokyo,” and therefore Ott’s presence also served their interest.123