Key findings

-

• Foodborne outbreak of multidrug-resistant STEC O26:H11 stx2a/eae associated with 50% of cases developing haemolytic uraemic syndrome.

-

• Likely vehicle was contaminated dried fruit sold as mini snack-packs for children.

-

• Batch numbers of the packs were unavailable and targeted microbiological testing of the food was not possible.

-

• In the absence of microbiological links to the food vehicle, use of multi-source weight of evidence frameworks supports the evidence for public health action.

Introduction

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) are a diverse pathotype of E. coli, defined by the production of Shiga toxin and the detection of Shiga toxin genes (stx), stx1 and/or stx2. There are at least 10 different well-established types of Shiga toxin (stx1a, stx1c, stx1d, and stx2a-stx2g) [Reference Koutsoumanis1]. Recently, additional novel stx subtypes have been described [Reference Lindsey2]. STEC cause abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea that can range from mild to severe and blood-stained. Strains of STEC producing Stx2a and Stx2d are most frequently associated with clinical symptoms at the severe end of the clinical spectrum, and with causing Haemolytic Uraemic Syndrome (HUS) – a potentially fatal, systemic condition characterized by thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia, and acute kidney injury [Reference Scheutz3, Reference McGeoch4]. Antibiotic treatment of STEC infection is contraindicated, as there is evidence that antibiotic-induced injury to the bacterial membrane triggers the acute release of large amounts of Shiga toxin [Reference Agger5]. The toxin preferentially targets the small blood vessels in the gut and the kidneys but can also cause cardiac, respiratory, and neurological complications, as well as progression to HUS.

STEC are zoonotic, foodborne, human gastrointestinal pathogens. STEC can colonize the gut of healthy ruminants and, in the UK, the animal reservoir is predominantly cattle and sheep. STEC are transmitted to humans via direct contact with animal faeces, or consumption of food or water contaminated with animal faeces. STEC has a low infectious dose (10–100 organisms) and person-to-person transmission can occur at high rates among households and institutional settings, such as schools, nurseries and care homes. In the UK, foodborne outbreaks of STEC have been caused by both domestically produced food, such as cooked minced beef and minced lamb, unpasteurized dairy products, and fresh produce contaminated by irrigation water or rainwater run-off containing animal faeces, as well as food imported from other countries [Reference Jenkins6–Reference Cunningham8].

Historically in the UK, STEC O157:H7 was the most frequently isolated STEC serotype from patients with HUS and severe bloody diarrhoea therefore, diagnostic and surveillance algorithms focused on this specific type [Reference Adams9]; although non-O157 STEC serotypes, most notably STEC O26:H11, were commonly reported elsewhere [Reference Bielaszewska10–Reference Krug20]. Outbreaks of STEC O26:H11 have been reported in the United States and 10–20]. Foodborne outbreaks of STEC O26:H11 have been linked to contaminated beef products, unpasteurized dairy products and flour [Reference Bielaszewska10–Reference Krug20]. Studies in Germany, France, and the UK have highlighted the emergence of highly pathogenic variants of this serotype associated with causing HUS [Reference Bielaszewska10, Reference Delannoy21–Reference Chase-Topping23].

The first foodborne outbreak in the UK caused by STEC O26:H11 was detected in 2019 and linked to the salad content of pre-packed sandwiches [Reference Butt24]. However, it is possible that, due to the focus on the detection of STEC O157:H7, foodborne gastrointestinal disease caused by STEC O26:H11 from domestically produced and imported food has been taking place beneath the surveillance radar for many years. The implementation of PCR for detection of gastrointestinal pathogens, including expansion for the majority of STEC serotypes such as O26:H11, has improved the surveillance of non-O157 STEC in the UK [Reference King25].

Systematic, national surveillance of gastrointestinal disease outbreaks in the UK is undertaken by the Health Security Agency (UKHSA), Public Health Wales and Public Health Scotland (PHS). In November 2023, routine microbiological surveillance at UKHSA identified a cluster of cases of STEC serotype O26:H11 stx2a/eae and a multi-agency Incident Management Team was convened. The aim of the investigation was to identify the source of infection and implement control measures to protect public health. This report describes the outbreak investigation and highlights the microbiological and epidemiological challenges encountered.

Methods

Microbiology investigations

In the UK, faecal specimens from hospitalized or community cases with symptoms of gastrointestinal disease are routinely cultured in local hospital microbiology laboratories for identification of STEC O157:H7. At the time of this investigation, approximately 40% of laboratories in the UK used commercial PCR assays for the detection of gastrointestinal pathogens, including STEC (i.e., also detecting non-O157 STEC) [Reference Vishram26]. Faecal specimens from patients where there is a clinical suspicion of HUS and/or testing positive for STEC by PCR and culture-negative for STEC O157:H7 on CT-SMAC agar were submitted to the Gastrointestinal Bacteria Reference Unit (GBRU) at UKHSA for confirmation by PCR and culture [Reference Jenkins27]. In Scotland, all culture negative high-risk faecal samples are submitted to the Scottish E. coli O157/STEC Reference Laboratory (SERL) for PCR testing and, if positive, STEC culture (Ref Scottish Guidance).

All strains of STEC isolated from faecal specimens were sequenced via Illumina Nextseq 1,000 or Miseq platforms, and serotype, stx subtype profile and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) types were derived from each genome, as described previously [Reference Chattaway28–Reference Dallman30]. A soft-core genome alignment was generated from SnapperDB v0.2.8 [Reference Dallman30] of outbreak genomes; this alignment had recombination masked by Gubbins v2.0.0 [Reference Croucher31] and a maximum-likelihood phylogeny was constructed using IQTree2 v2.0.4 [Reference Nguyen32].

AMR determinants were sought using ‘Gene-Finder’, a customized algorithm that uses Bowtie2 (v.2.3.5.1) to map reads to a set of reference sequences and Samtools (v.1.8) to generate an mpileup file, as previously described [Reference Gentle33]. The presence of resistance genes was defined based on 100% read coverage and > 90% nucleotide identity relative to the reference sequence, with the exception of β-lactamase variants that were determined with 100% identity using the reference sequences downloaded from the Lahey (www.lahey.org) and National Center for Biotechnology Information β-lactamase data resources (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pathogens/beta-lactamase-data-resources). Known acquired-resistance genes and resistance-conferring mutations relevant to β-lactams (including carbapenems), fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, chloramphenicol, macrolides, sulphonamides, tetracyclines, trimethoprim, rifamycins, and fosfomycin were included in the analysis. Chromosomal mutations focused on variations in the quinolone resistant determining regions of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE. Isolates that had AMR determinants known to confer resistance to three or more classes of antimicrobial were defined as MDR.

Data availability statement

FASTQ reads from sequences in this study can be found at the UKHSA Pathogens BioProject at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (accession number: PRJNA315192).

Epidemiological investigations: Case detection

Prospective and retrospective case ascertainment was undertaken by reviewing all whole genome sequencing data held in the UKHSA and SERL. Previous analysis of the relatedness of isolates of STEC has shown that isolates from cases epidemiologically linked to the same outbreak fall within the same 5-SNP single linkage cluster therefore, confirmed cases were defined by this threshold (Table 1). Additionally, contact tracing was undertaken by regional teams in all three nations which enabled identification of probable cases. UKHSA and PHS operates a national enhanced surveillance system for STEC [Reference Butt34]. Therefore, STEC cases are initially interviewed with an Enhanced Surveillance Questionnaire (ESQ), which collects standardized information on the patient’s clinical presentation, food history, travel history, contact with animals, and environmental exposures for the 7 days prior to illness onset.

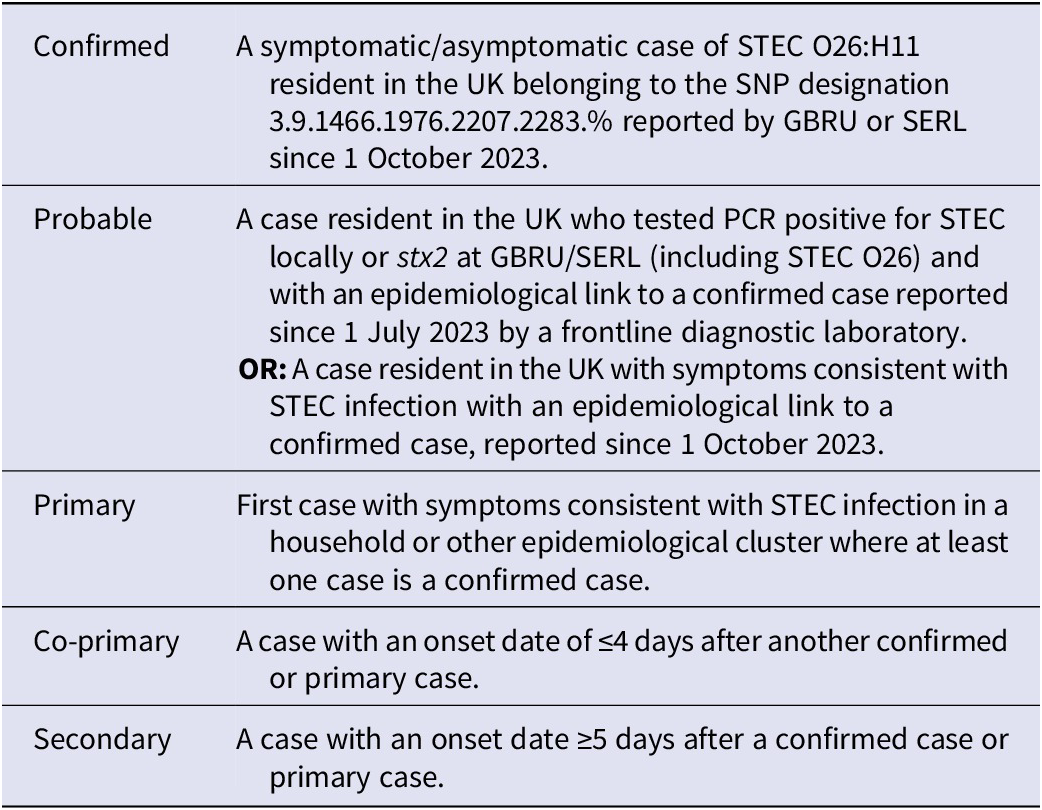

Table 1. Case definitions used in the investigation of the STEC O26 outbreak in the UK, October 2023 to September 2024

Descriptive epidemiology

Initial review of ESQ data did not elucidate a signal for a vehicle of infection. Consequently, the first five primary cases reported were re-interviewed via telephone using an open-ended, iterative exploratory approach to generate a hypothesis. Consequently, a targeted questionnaire for hypothesis testing was generated, and used to interview an additional 15 primary cases that responded to requests for further follow-up. Details of hypothesized vehicles (including product description, purchase location, and loyalty card information where available) reported by interviewed cases were shared securely with Food Safety Authorities for food chain investigations and product trace-back.

All data from interviews were collected in compliance with data protection guidelines. Public health authorities in the UK have delegated authority, on behalf of the Secretary of State, to process Patient Confidential Data under Regulation 3 The Health Service (Control of Patient Information) Regulations 2002. Regulation 3 makes provision for the processing of patient information for the recognition, control, and prevention of communicable disease and other risks to public health.

Analytical epidemiology: Case–control study

A case–control study was undertaken across all four UK nations. Sample size calculations were undertaken using OpenEpi (Fleiss’ formula with continuity correction, with the following assumptions: 80% power; 95% confidence level; assumed exposure in controls: 20%; assumed exposure in cases: 60%); a minimum detectable odds ratio was calculated to be 6.

Controls were recruited via a market research panel and frequency matched to cases by age group (0–1, 2–4, 5–9, 10–17, 20–29, 30+ years) to ensure representativeness given the large proportion of cases aged under 5 years. Based on power calculations, controls were recruited on a control: case ratio of at least 4:1, with the exception of the 0–1 year age group in which controls were only obtained in a 3:1 ratio as there was difficulty obtaining sufficient number of controls in this age category. The inclusion criteria for controls required no history of diarrhoea and/or vomiting and no travel within or outside the UK in the 7 days prior to questionnaire completion. Controls completed bespoke online questionnaires focused on exposures of interest; case data were obtained from trawling questionnaires.

Univariable analysis of each exposure variable was undertaken; odds ratios (OR), p-values (calculated using the Wald test), and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported for each exposure. Exposures with raised odds of illness (i.e., OR > 1) and p-value ≤0.2 were considered for inclusion in multivariable analysis

Firth’s multivariable logistic regression was used to fit models and obtain adjusted Odds Ratios and 95% CIs; a forward stepwise approach was utilized to select variables, retaining those that improved model fit using the model with a constraint to compare via the likelihood ratio test [Reference Heinze and Schemper35]. Stratified analyses were performed to assess confounding and effect modification; data were analysed using R version 4.2.1, RStudio 2022.07.0 + 548 and STATA version 17.0.

Microbiological sampling of food

One hundred and one multipack units of a multi-pack dried fruit product denoted Product X from a variety of brands and retailers reported by primary cases were collected by UKHSA staff and local Environmental Health Officers between 10/01/2024 and 09/04/ 2024. An additional seven were provided by cases with residual product in their houses (notably, all cases were unsure as to whether they consumed suspected multi-pack products during their incubation period). A supplier of multi-pack dried fruit of interest identified from food chain investigations submitted another 45 samples from the country of origin. All 153 samples were transported in accordance with the FSA Food Law Code of Practice to UKHSA Food, Water & Environmental Microbiology laboratories at ambient temperature.

Samples were examined for STEC based on the ISO/TS 13136:2012 method (ISO 2012) and using a ‘SureTect™ E. coli O157:H7 and STEC Screening PCR Assay’ (Thermofisher, Basingstoke, UK), performed according to the manufacturer’s instruction on a QuantStudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems) [Reference Faulds36]. Briefly, this involved enrichment in buffered peptone water, screening by real-time PCR for stx, O157:H7 and eae genes, followed by subculture onto cefixime tellurite sorbitol MacConkey and tryptone bile glucuronic agars, and finally, PCR for any stx-positive sample enrichments.

Results

Descriptive epidemiology

Between October 2023 and September 2024, 37 confirmed cases and 3 probable cases, distributed across the UK, were reported. Whilst classifications of primary, co-primary and secondary cases were difficult to establish due to high rates of person-to-person transmission, particularly among households, epidemiological links suggest, of the 37 confirmed cases, there were: 24 primary cases (5 of which are co-primaries); 11 secondary cases (of which 6 were asymptomatic cases, presumed secondary); and 2 cases which were lost to follow-up. Of the 3 probable cases, 2 were primaries (1 co-primary) and 1 was a secondary case. The confirmed, probable, primary, co-primary, and secondary cases are defined in Table 1.

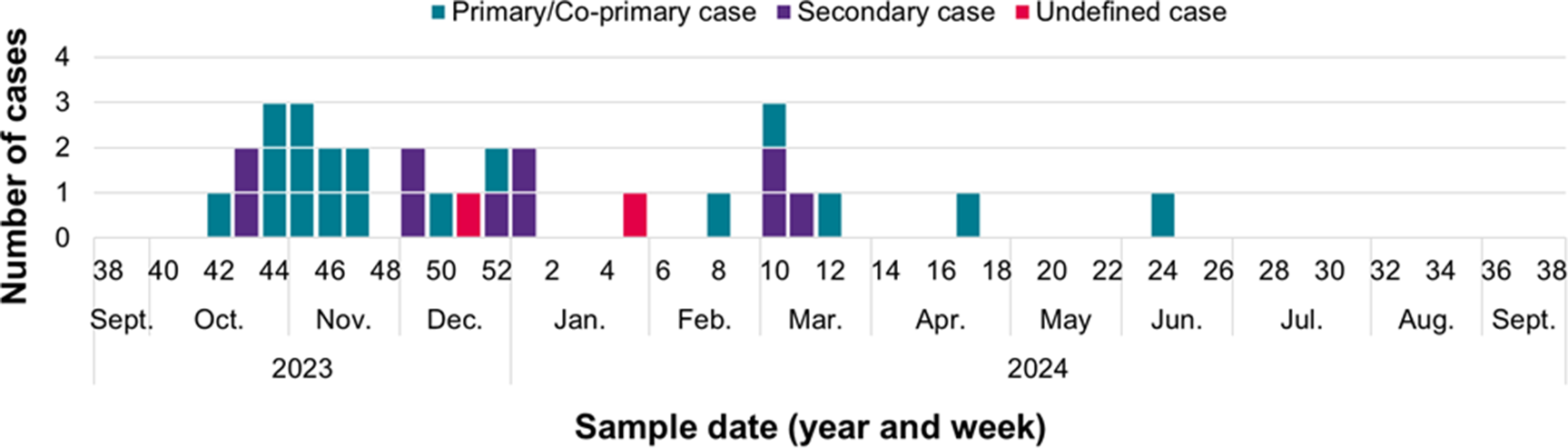

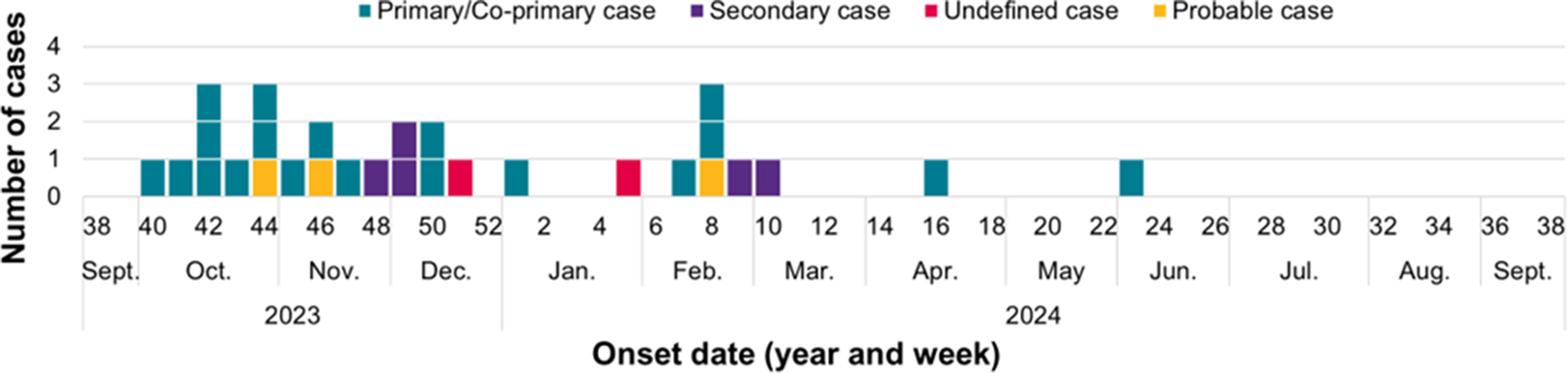

Case reporting peaked during weeks 42 of 2023 and week 1 of 2024 (Figure 1). Onset dates were available for 31 symptomatic, confirmed cases and the 3 probable cases (total = 34), and range between 07 October 2023 and 8 June 2024, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Temporal distribution of confirmed cases in the STEC O26 outbreak investigation in the UK, October 2023 to September 2024, by stool sample date (n = 36)*. *Sample dates are unavailable for 1 confirmed case.

Figure 2. Temporal distribution of confirmed (n = 31) and probable (n = 3) cases in the STEC O26 outbreak investigation in the UK, October 2023 to September 2024, by onset date* (n = 34). *Onset dates are unavailable for 6 asymptomatic, confirmed cases.

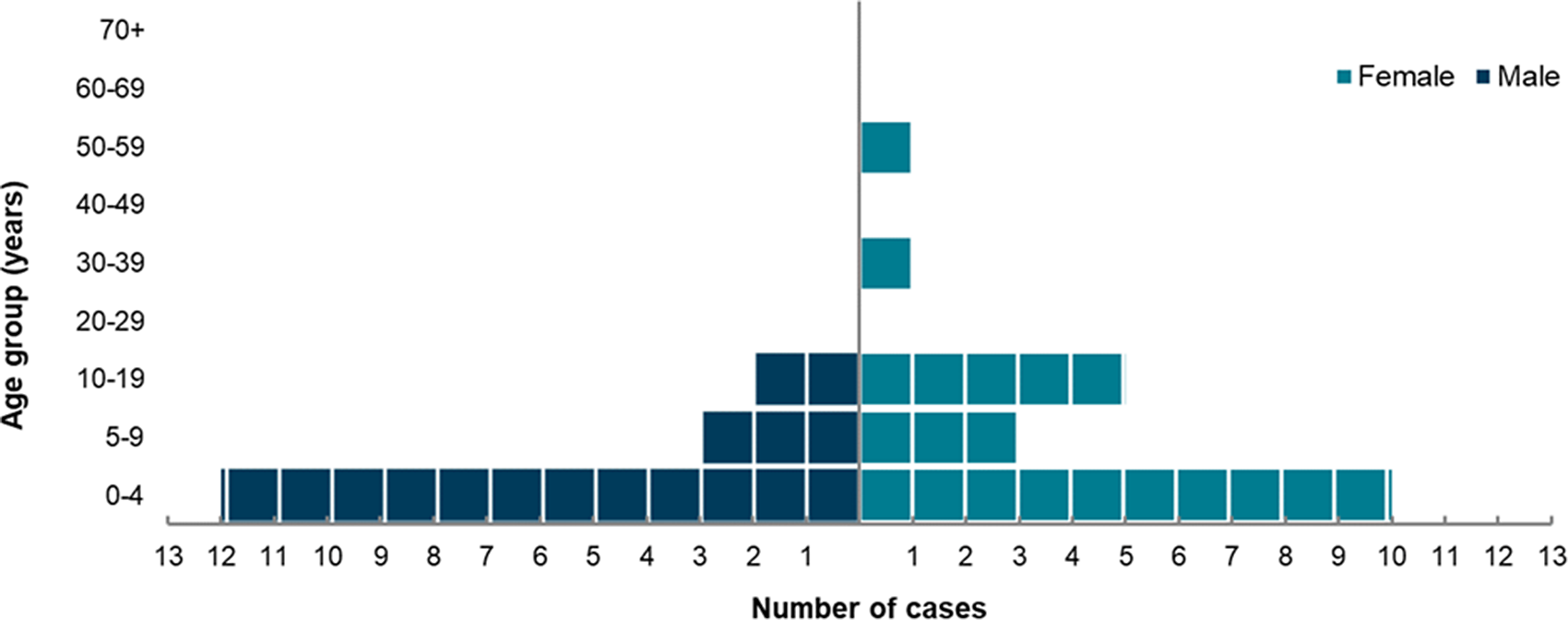

The age and sex distribution of all confirmed cases is summarized in Figure 3. Confirmed cases ranged in age from 10 months to 56 years with a median of 3 years; the 0–9 age group was most affected, accounting for 76% of confirmed cases, and 59% of all confirmed cases were aged under 5 years. There were more female (n = 20) than male (n = 17) confirmed cases (Figure 3). The 3 probable cases were all female, aged between 5 and 15 years old. Notably, there were 9 epidemiological clusters, predominantly consisting of household contacts among young siblings, indicating high rates of person-to-person transmission.

Figure 3. Age-sex distribution of confirmed cases in the STEC O26 outbreak in the UK, October 2023 to September 2024 (n = 37).

Clinical outcome data

Among the 31 symptomatic, confirmed cases, 22 reported bloody diarrhoea and 18 were admitted to hospital. Overall, 19 confirmed and probable cases developed HUS; ages ranged between 12 weeks to 15 years with a median age of 3 years, although the majority (74%) were aged 5 or under; 68% were female (n = 13).

Food history derived from ESQs of confirmed primary/co-primary cases (n = 17).

Exposure information was collated from the ESQs available for 17 primary/co-primary confirmed cases; notably, many of the ESQs were only partially complete or with inconsistencies when comparing within a household. There were no commonalities in food consumption outside the home or travel within the UK. Commonly reported (i.e., reported by >50% of primary cases) food items consumed within the home included: cooked poultry; cooked beef; pasteurized cheese, milk, and yoghurt; however, there were multiple retailers and brands reported.

Exploratory results

Five cases were interviewed using an exploratory approach. A dried fruit, multi-pack product (denoted Product X) purchased from 2 supermarkets was the most commonly reported item, consumed by all five cases.

Trawl results

Of 15 primary cases interviewed via trawling questionnaire, 9 (60%) reported consuming Product X reportedly purchased from 5 different retailers; an additional 2 cases reported consuming the same dried fruit in a bulk packet. The second most commonly reported item was chicken nuggets (n = 8, 53%); however, no commonalities in type, brand, retailer, and supplier were identified.

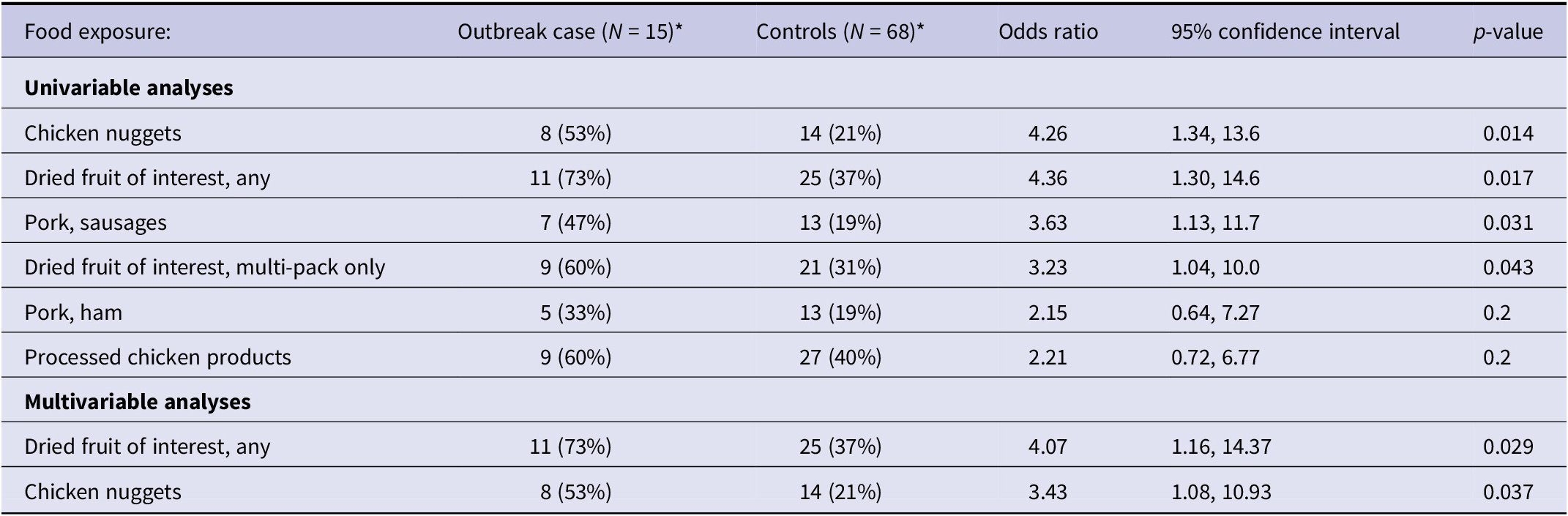

Analytical epidemiology: Case–control study

Table 2 summarizes the univariable and multivariable analyses: the final model, inclusive of age a priori¸ included ‘dried fruit of interest, any’ (OR 4.07, 95% CI: 1.16–14.37, p = 0.029), and chicken nuggets (OR 3.43, 95% CI: 1.08–10.93, p = 0.037). Notably, ‘dried fruit of interest, any’ is a compound variable consisting of both multi-pack and bulk reports of the dried fruit of interest, whereas ‘chicken nuggets’ is an individual food item. However, the majority (9/11) of reports of dried fruit in the ‘dried fruit of interest, any’ variable was for small, multi-packs of the dried fruit.

Table 2. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression results for food items of interest in the STEC O26 outbreak investigation in the UK, October 2023 to September 2024

Note: Number and proportion of cases and controls, odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values are presented for each food exposure. Univariable analysis assessed each exposure independently; results are displayed for exposures with OR > 1 and p ≤ 0.2. Multivariable analysis included age a priori, and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) are presented.

National Diet and nutrition survey (NDNS) data

Data derived from the NDNS estimated that, for children aged 0–5 years, typical consumption of any type of the dried fruit of interest was between 19 and 24% of that population over a 4-day period, although underreporting is a known issue with NDNS data.

Food chain investigation results

Product trace-back identified a singular supplier in a non-European country that exported to the five major UK retailers from which all interviewed primary cases reported purchasing Product X. Additionally, supply chain timings (crop harvesting, production, time period on sale, and use-by dates) coincided with temporal distribution of the epidemiological curve. Further food chain investigations were hampered by the limited available information on growing and processing procedures, and lack of specific batch information for Product X consumed by the cases.

Randomized sampling of for-sale products

All food samples tested yielded negative results for STEC. A total of 56 different batch codes were tested; additionally, two samples collected from cases’ houses had unknown batches.

Microbiology, genomics, and phylogenetic analysis

The outbreak strain belonged to serotype O26:H11, clonal complex 29, sequence type ST21, and had stx2a and eae. Unusually for STEC isolated from UK patients, the outbreak strain was multidrug resistant, harbouring antimicrobial resistance genes bla TEM-1, aph(6)-Id, tetA, and sul2 known to confer resistance to beta lactam antibiotics, aminoglycosides, tetracycline, and sulphonamides.

STEC O26:H11 is the second most commonly detected STEC in the UK after STEC O157, and there is an extensive back catalogue of 3,500 strains of STEC O26:H11 in the UKHSA archive. All UKHSA sequencing data is publicly available on Enterobase, a tool for exploring the genomic epidemiology of pathogens (EnteroBase). The outbreak cluster was designated HC5:265110 and EnteroBase was interrogated to determine whether the outbreak strain was present in other countries. There were no isolates in the global database that were phylogenetically closely related to HC5:265110.

Discussion

Although the number of cases linked to this outbreak was small compared to other recent foodborne outbreaks of STEC in the UK, it posed a substantial public health concern due to the high proportion of affected individuals who developed HUS [Reference Cunningham8, Reference Quinn37]. The high rate of HUS was most likely due to a combination of the high proportion of children and the pathogenicity profile of the strain [Reference Koutsoumanis1, Reference Rodwell38, Reference Byrne39]. Children under the age of 5 years are especially vulnerable to STEC infection and progression to HUS [Reference Rodwell38, Reference Byrne40]; and this outbreak strain had stx2a and eae – the combination of pathogenicity genes most frequently associated with the most severe clinical outcomes, including HUS [Reference Koutsoumanis1, Reference Byrne39, Reference Byrne40]. Additionally, 5 cases (14%) were administered antibiotics, 4 of whom developed HUS, antibiotics are contraindicated for the treatment of STEC as there is evidence that treatment can exacerbate the risk of progression to HUS, due to the sudden release of Shiga toxin from the injured bacterial cell [Reference Launders41]. Consequently, with respect to clinical management, it is important to reiterate the message that children with symptoms of gastrointestinal disease should not be treated with antibiotics unless STEC infection has been ruled out.

Multi-weight evidence – i.e., descriptive and analytical epidemiological, and food chain data – indicated a multi-pack dried fruit food (Product X) to be the most plausible vehicle of infection. In addition to the analytical epidemiological study, the descriptive analysis (including comparison with NDNS data) highlighted Product X as the singular, specific food item reported by the highest proportion of cases and, anecdotally, cases reported a high frequency of consumption. Additionally, the temporal distribution of cases correlated with the Product X supply chain, with the first peak correlating with the timing of sale based on the Best Before Date (BBD), the second peak near the end of the BBD and sporadic cases in-between indicative of a long shelf-life product, providing a reasonable level of food chain tracing investigative evidence even though the food chain investigations could not be progressed beyond this level of detail.

Whilst microbiological testing of the food failed to detect the pathogen, the difficulties associated with detecting foodborne pathogens such as STEC, particularly non-O157 STEC, in food are well-established and have been described previously [Reference Anthony42]. There are no selective enrichment methods for non-O157 STEC and although semi-selective media, such as STEC Chromagar, are available, they are not as effective as the selective media for STEC O157 [Reference Jenkins27]. The infectious dose of STEC is low, so contamination of the product may be at a low level and maybe be below the detection level of the test. A previous study concluded that unique stressors on dried fruit can induce a viable but non-culturable state in Salmonella, thus rendering it undetectable with culture-based methods even though the bacteria remain viable and maintain the potential to cause human illness [Reference Jayeola43]. Additionally, specific batch numbers could not be obtained for testing, limiting the option for targeted testing to enhance the ability to obtain microbiological evidence for a suspected food vehicle of infection in outbreak investigations. This was compounded by the very small number of samples tested proportional to the total number of units from the crop of interest, particularly given contamination was likely low-level and intermittent. Consequently, the importance of relying on multi-source weight of evidence frameworks, such as EFSA, which enable the classification of vehicles of infection in outbreaks as ‘strong’ even in the absence of confirmation of the outbreak strain presence in food items derived through testing of hypothesized food vehicles is further illustrated – particularly given the rise in WGS, which enhances confidence in source attribution [Reference Hardy44].

Fruit for drying can become contaminated when the crop is exposed to irrigation water or rainwater run off containing animal faeces or during extreme weather events, such as flooding; post-harvest contamination may occur during the drying and packing processes. Although not a reservoir of infection in the same way as ruminants, small mammals, birds, and insects can become transiently colonized by STEC and act as transmission vectors. Dried fruit was suspected as the cause of an outbreak of Salmonella Agbeni in Norway in 2018–2019 [Reference Johansen45] and recently, an isolate of Salmonella Hvittingfoss sequence type (ST) 2,501 isolated from sultanas during routine microbiological testing was submitted to GBRU, providing further evidence that dried fruits are a plausible food vehicle of gastrointestinal pathogens (UKHSA in-house data). Additionally, the whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data, which indicated the strain was not domestic in origin, supported the analytical and food chain evidence that the vehicle was likely an imported dried fruit product.

Despite the close collaboration between UK public health agencies, food safety agencies, local authorities and the food business operator throughout the duration of this outbreak, investigating outbreaks linked to a food source from another country can be challenging. The main objectives of an investigation are to prevent further cases by an immediate intervention (e.g. by halting distribution of a food or by recalling it from market retailers) and by longer term prevention efforts to identify processes or practices that need to be changed to avoid future incidents of contamination [Reference Lasky46]. Both aspects of this part of the investigation are difficult to co-ordinate remotely, without legislative recourse for control of zoonotic pathogens in products of non-animal origin and across language barriers.

Detection of STEC in food remains a challenging problem. Thus, robust epidemiological studies can – and do – provide a sufficient scientific evidence base for identifying the vehicle of infection, however, in this outbreak, there were insufficient primary cases to enable an analytical study during the peak of the outbreak. Consequently, at that point in time and given the total number of confirmed cases was small, despite the weight of descriptive epidemiological evidence, there was insufficient proportionality to justify a recall of over 60 million annual units of Product X supplied to the UK by the one producer.

Acting on the early warnings from colleagues in Europe and elsewhere documenting the emergence of STEC O26, public health agencies across the UK have been working over the last two decades to improve STEC diagnostic and surveillance algorithms to detect and type non-O157 STEC causing HUS and contributing to foodborne outbreaks. Adoption of commercial gastrointestinal PCR at the local level is a positive development, improving routine and outbreak surveillance.

Without robust and reliable methods for detecting STEC from food, food business operators cannot monitor the food safety risks associated with their product prior to sale. This means that standard, HACCP-based approaches to ensuring a safe food product is placed on the market are not feasibly implementable by food business operators. This additionally confirms the need for reliance upon pathogen-specific, weight of evidence frameworks whereby, even in the absence of isolates derived through the microbiological sampling of suspected food vehicles in an outbreak scenario, multi-source descriptive and analytical epidemiological and food chain evidence can – and should – be utilized for public health protection action. Furthermore, WGS continues to be the most important tool we have at our disposal for outbreak detection and strain characterization, including the pathogenicity and the antimicrobial resistance profiles and to provide phylogenetic evidence of the geographical origin of the outbreak strain. Further investment in WGS for surveillance of gastrointestinal pathogens in countries around the world, and expansion of regional and global surveillance networks for information sharing to detect and investigate outbreaks will mitigate the risk of foodborne threats at home and abroad [Reference Ammon and Tauxe47, Reference Gomes48]. For STEC, where detection of the causative agent in food is particularly challenging, we stress the importance of multi-source weight of evidence frameworks that promote the application of epidemiological and food chain evidence as key drivers that can provide the necessary, robust evidence base for public health action.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all members of the incident management team for their contributions during this outbreak, including colleagues from the UK Health Security Agency, including the involved Health Protection Teams, Public Health Wales, Public Health Scotland, Food Standards Agency and Food Standards Scotland.

Author contribution

Rosie Collins: Investigation, Analysis, Writing, Final approval; Claire Jenkins: Conception & Design, Analysis & Interpretation, Supervision & Resources, Writing & Editing, Final approval; Orlagh Quinn: Investigation, Final approval; Amy Douglas: Investigation, Editing, Final approval; Lesley Allison: Investigation, Editing, Final approval; Andrew Nelson: Investigation, Final approval; Frieda Jorgenson: Investigation, Editing, Final approval; Ben Sims: Investigation, Final approval; David R. Greig: Analysis & Interpretation, Final approval; Sooria Balasegaram: Analysis & Interpretation, Supervision & Resources, Editing.

Funding statement

Claire Jenkins and Sooria Balasegaram are affiliated to the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Gastrointestinal Infections at University of Norwich in partnership with UKHSA, in collaboration with University of Newcastle and are based at UKHSA. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or UKHSA.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.