Introduction

In the late nineteenth century, the question of national identity fuelled the efforts of many musicians in the United States to distinguish themselves from Europeans. At this time, Edward MacDowell held a liminal position, well-known and active in Europe but also championed as a leading figure of US musical identity. As the country reached its centennial in 1876, efforts to foster US cultural and economic interests grew more prevalent. In the 1880s, conductor Frank Van der Stucken organized novelty concerts to showcase new orchestral music by US composers, and he presented an American Festival of five concerts held in New York’s Chickering Hall in November 1887. In his first concert, he included the Hamlet portion of Edward MacDowell’s Hamlet. Ophelia. Zwei Gedichte für grosses Orchester, positioning MacDowell and his composition as important components of US music and identity.

Although Van der Stucken foregrounded the ‘American’ dimension of the piece by programming Hamlet in his American Festival, MacDowell’s symphonic poem holds layers of cultural meaning in its various associations with European artistic, dramatic and musical figures. MacDowell wrote Hamlet. Ophelia. Zwei Gedichte für grosses Orchester, op, 22, in Frankfurt in 1884. The style and motivic material of MacDowell’s symphonic poem are reminiscent of Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, suggesting an aesthetic and thematic connection. At the time of MacDowell’s composition, Wagner had been dead for less than a year. Wagner’s music and aesthetics had wide-reaching influence, permeating cultural life beyond Bayreuth and other German cities to countries as distant as England and the United States. A Wagnerian spirit resonates in MacDowell’s Hamlet and Ophelia both in MacDowell’s compositional style and in the piece’s allusions to the world of London theatre. MacDowell composed his symphonic poem after he and his wife returned from their honeymoon in London, a city imbued with cultural Wagnerism in the late nineteenth century. While in London, MacDowell and his wife saw the intense dramatic portrayals of the famous Shakespearean actors, Henry Irving and Ellen Terry. Accounts of Irving and Terry describe the tragic romance of their Shakespearean interpretations, suggesting their enactment of Hamlet might be understood through the lens of Wagnerism and the tragedy of Tristan und Isolde. MacDowell’s dedication of his symphonic poem to Irving and Terry indicates his musical response to the influence of their dramatic aesthetic. Traces of these interwoven cultural connections can be perceived in the music, inviting listeners to imagine the musical Hamlet and Ophelia as the overlapping figures of Henry Irving and Ellen Terry, their portrayals of the Shakespearean characters, Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, and the young newlyweds Edward and Marian MacDowell.

As the piece’s compositional background indicates, MacDowell’s symphonic poem embodies a confluence of many elements moving and transforming through different environments. These rich cultural layers of MacDowell’s Hamlet implicate issues of national identity and aesthetic value, issues that clarify the competing positions of the composer: as a nuanced cosmopolitan composer exhibiting English, French and Germanic elements in his work; as a US composer valorized to promote national identity; and as a proponent of aesthetic value transcending national origin. With such cultural intercrossings present in the music, the inclusion of Hamlet in the American Festival reflects a late nineteenth-century US musical national identity composed of multi-cultural complexity. This article explores each cultural layer of MacDowell’s Hamlet and Ophelia to position the symphonic poem as a microcosm of the rich cultural landscape of the United States at the close of the nineteenth century.

To parse the many dimensions of the microcosmic symphonic poem, this article spans MacDowell’s biography, his piece’s creative origins and Wagnerian spirit, its intersection with Henry Irving, Ellen Terry and their Shakespearean interpretations, and its performance in Frank Van der Stucken’s American Festival. Primary source documents illustrate the depth of the microcosm as manuscript evidence illuminates the flow of ideas from MacDowell’s engagement with the New German School, London theatre and supporters of US identity. New dimensions of the cultural and aesthetic richness of MacDowell’s experiences and activities are revealed through his musical sketches, correspondence and his wife’s biographical and autobiographical writing. Furthermore, newspaper reviews and MacDowell’s own public writing indicate the meaningful position of the composer and his symphonic poem in the American Composers’ Concert movement, its efforts to promote US music and the true cultural hybridity of the US landscape. The microcosm of MacDowell’s Hamlet and Ophelia also points to the breadth of the flow of musical and cultural ideas, bringing attention to the transatlantic movement of musical aesthetics, ideologies of the New German School, and conceptions of national identity, as well as the transformation of such ideas as they move through different cultural situations.

Exploring MacDowell’s Hamlet as a microcosm of the United States illuminates the plurality of US musical culture. While MacDowell has traditionally been recognized as a cosmopolitan American composer, the simple label ‘cosmopolitan’ fails to capture the nuanced complexity of MacDowell’s multi-cultural background and creative output.Footnote 1 The frequent use of the term ‘cosmopolitan’ to succinctly describe the many composers who lived and worked in different geographic regions masks the rich experiences of such composers on their journeys and the multi-cultural meanings contributed to their output. MacDowell’s international growth and his deep immersion in the cultural environments within which he worked reveal the complexity of his cosmopolitan stature and the entangled nature of national striving bestowed on his music. Examining the story of MacDowell’s Hamlet and its position in the first concert of Frank Van der Stucken’s American Festival illuminates MacDowell’s stature as more than simply a ‘cosmopolitan American composer’, revealing a new understanding of his late nineteenth-century US identity and its cultural entanglement.

Cultural Transfer and Defining US Musical National Identity

During the latter half of the nineteenth century, culture-bearers of the United States felt a strong pull to engage in the international cultural arena while also constructing a strong domestic national community. The US sought to establish its national individuality through patterns of cultural transfer, assimilating and rejecting European cultural precedents. Several accounts of music history in the US explore the attempts of musicians to establish a unique national school producing music of a distinctive identity.Footnote 2 These accounts trace the efforts to integrate US vernacular musical elements with European orchestral musical traditions in the time frame of the late 1800s to the early 1900s, moving from nineteenth-century US imitation of European style to active pursuit of Americanism. Many discussions of US musical culture draw attention to the nuances of the transatlantic cultural and musical interactions of the time. For example, Douglas Shadle’s Orchestrating the Nation examines the intellectual and cultural perspectives surrounding US identity and music in the nineteenth century through the lens of canon formation.Footnote 3 Shadle describes American receptivity toward European culture and the influence of German musical models – in particular, the ‘nascent idea that the symphony could express a national identity, project distinct political connotations, and serve as an agent of cultural uplift and ennoblement’.Footnote 4 Speaking in terms of cultural capital, Shadle explains processes of conferring value upon music and shifting perceptions of ideology and aesthetics that minimized US symphonies in the public consciousness. Shadle focuses his discussion on the value of European musical ideas adapted into US culture:

[T]he story of American orchestral music is both national and international. The realities of cultural and material exchange within the United States and across the Atlantic deeply affected … the rapid circulation of people, objects, and ideas across the ocean, and with a large body of performance repertoire that was shared with European orchestras, the American symphonic enterprise of the nineteenth century was one of the most vibrant intercultural exchanges in all of Western music history.Footnote 5

As US culture-bearers sought to establish national identity, they adapted various European models of aesthetics, discourse and practices of music, art, literature and theatre. European repertoire, orchestral institutions and press culture provided examples for US musical development. Many of these cultural components had already undergone processes of intercrossing, and they continued to shape and be shaped by US ideals and social life.

In addition to the musical dimension of cultural transfer, literary and dramatic ideas moved and transformed through cultures. This phenomenon is demonstrated by Shakespeare in the transatlantic network of the late nineteenth century. While eighteenth-century England centred Shakespeare as a British master and strong national poet, his legacy spread beyond the borders of England and transformed throughout many cultures in Europe and the US.Footnote 6 Shakespeare’s texts underwent changes as translators selected different words to convey the prose’s affect, meter and meaning in new languages. Editors compiled Shakespeare’s works for different purposes, publishing complete texts, well-known excerpts or selections in oration textbooks. The cultural practices of drama and theatre around the world further transformed Shakespeare’s works. Actors adapted the plays in different ways, cutting out sections to limit characters, shorten the performance or tell a certain version of the story. The choices of inflection and gesture that accompanied each actor’s delivery communicated personal and cultural values of the themes and underlying messages of the plays. These transformations of Shakespeare demonstrate the adaptability and interactivity of cultural elements.

The elements of national identity, Shakespearean interpretation and musical aesthetics collide in MacDowell’s Hamlet and its position in the dynamic artistic world of the late nineteenth century. European actors and musicians travelled to the United States, touring in performances and engaging with US cultural institutions. Similarly, US composers travelled to Europe to study in conservatories and train with prominent musicians, returning home with their new experiences and European perspectives. Through the agential work of performers, composers, conductors and critics, US musicians adopted European standards of musical aesthetics in composition, performance, programming and reception. MacDowell’s Hamlet acts as a microcosm of these elements in late nineteenth-century US musical life, facilitating an exploration of MacDowell’s interactions with Shakespearean and musical aesthetics, the significant experiences of cultural perspectives on Shakespeare that shaped his interactions, and the evolution of these dimensions converging in his Hamlet and Ophelia.

Edward MacDowell, Shakespeare and the New German School

MacDowell’s musical and cultural activities stretch back to his childhood, and a brief overview of his background will set the stage for exploring how his complex cultural entanglement would continue to develop and come to bear on late nineteenth-century conceptions of US national identity. Born in New York in 1860, Edward Alexander MacDowell spent his childhood with a Quaker upbringing, reading, drawing and studying piano. He began taking piano lessons in the late 1860s with Juan Buitrago, a family friend from Colombia, and later with Pablo Desvernine from Cuba. The repertoire MacDowell studied, and the wide variety of performances presented in New York’s musical scene, likely exposed him to music of different cultures and influenced his musical creativity.Footnote 7

MacDowell received his first taste of Europe in 1873, when he and his mother toured Ireland, Scotland, England, Belgium, Germany, Switzerland and France. After his initial visit, MacDowell returned with his mother in 1876 to study piano and composition at the Paris Conservatoire. He received private piano training under Antoine-François Marmontel before he was admitted into the Conservatoire in 1877. MacDowell left after two years of study, moving on to pursue his education at Stuttgart, Wiesbaden and Frankfurt. In Frankfurt, he studied at the Hoch Conservatory with Carl Heymann and Joachim Raff. While Raff had been a student of and personal assistant to Franz Liszt in Weimar, his aesthetic ideals were more eclectic than Liszt’s, striving for a balance between ideals of the progressive New German School and those of a more conservative perspective. MacDowell developed a close relationship with Raff, and, after leaving the conservatory in 1880, MacDowell continued private training in composition with Raff until the latter’s death in 1882.

In 1881, MacDowell joined the Allgemeiner Deutscher Musikverein (ADMV), a musical society founded by Liszt and Franz Brendel in 1861 to promote the ideals of the New German School (Figure 1). Joining the ADMV had important ramifications for MacDowell’s musical future and that of the United States; the society became a model for MacDowell’s aesthetics and pursuits of national identity, giving greater attention to inclusivity, integration and artistic merit over nationality. The organization held festivals each year in German cities for the performances of new works by composers engaging in the aesthetics of Liszt and Wagner. A dispute arose within the ADMV in the 1880s as members debated widening the inclusivity of the organization. While some wanted to continue promoting exclusively German music, others – including Liszt – wanted to extend support to foreign composers, such as Saint-Saëns and Tchaikovsky, who held aesthetic ideals similar to those of the New German School. As an indication of the broadening membership, the 1882 ADMV festival was to be held in Zurich, the first time a festival would occur outside of Germany. MacDowell submitted his Erste moderne Suite for consideration to be performed in the 1882 ADMV festival, and Liszt responded with his support and recommendation for its acceptance. Liszt’s endorsement positioned MacDowell as one of the few foreigners in the Germanic ADMV and bolstered his early career. MacDowell’s successful performance at the festival exposed him to Liszt and other members of the ADMV who shared his compositional innovation, programmatic aesthetic and productivity with cultural engagement. As MacDowell’s career progressed, his music continued to reflect aesthetics like those of Liszt and the New German School, but he created his own distinct musical identity. Like his mentor Raff, MacDowell adapted to different cultural environments, working within them but maintaining his own style and language of music.

Figure 1. MacDowell’s ADMV membership card. Library of Congress, Music Division, Edward and Marian MacDowell Collection (EMMC), Box 33.

MacDowell’s affiliation with the New German School’s aesthetics further extends to German appreciation of literature and drama through his selection of source material. By choosing the subjects of Hamlet and Ophelia for his symphonic poem, MacDowell’s composition joined the intercrossing of the German adoption of England’s Shakespeare. The narrative of Hamlet resonated with the late eighteenth-century cultural Sturm und Drang aesthetic of German art, music and literature of the time, conveyed through individual subjectivity, extremes of emotion and dramatic genius.Footnote 8 An early nineteenth-century translation of Hamlet by August Wilhelm Schlegel served as the dominant source of the drama, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe included a scene of actors staging Hamlet in his book, Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre. Goethe’s interpretation of the play and aesthetics of performance influenced many German productions of Hamlet, which were characterized by an idealized acting style of gracefulness, beauty and harmony.Footnote 9

The composers of the New German School reflected the cultural appreciation of Shakespeare in their own music and writings, aligning Shakespearean aesthetics with their own. Liszt identified Shakespeare as a master of communicating genuine human experience:

Shakespeare unveiled for us the unshielded glow of love so much better … Like love in real life shows us, lovers are imaginative, and they overcome obstacles and fight against difficulties: this is how he portrays them to us. Before us he unveils their powerful truth of Feeling and convinces us of their virtuous glory, and he also illuminates even the most minor characters with the lights of his palette. His scenes are complete with all of the pathetic levers that play upon our lives and influence our destiny.Footnote 10

Furthermore, Liszt highlighted Hamlet as one of the ‘immortal personages’ – alongside Goethe’s Faust, Byron’s Childe Harold, Chateaubriand’s René, Senancour’s Obermann and George Sand’s Lélia – that exemplify ‘artistic Feeling’.Footnote 11 The subjects of Liszt’s programmatic music reveal the literary and artistic works he deemed worthy of musical treatment, including Dante’s Divine Comedy and Goethe’s Faust. Turning at last to Shakespeare, Liszt composed a symphonic poem of Hamlet in 1858.Footnote 12 Several scholars have noted the likely influence of the German actor Bogumil Dawison on Liszt’s conception of the musical Hamlet, citing Dawison’s performances in Weimar and encounters with Liszt.Footnote 13 The connection between Liszt and Dawison indicates the high esteem in which the composer held Shakespeare’s works and the prominence of a distinct cultural interpretation of Shakespeare. While it is uncertain whether MacDowell might have been influenced in any way by Liszt’s Hamlet, MacDowell’s creativity resonated with that of Liszt. MacDowell constructed characters in his symphonic poems in the style of Liszt’s musical portraits, capturing the personae of Hamlet and Ophelia in a manner similar to Liszt’s character sketches. Furthermore, MacDowell’s selection of Hamlet as a musical topic suggests he also held a deep appreciation of Shakespeare and deemed the tragedy worthy of musical treatment just as Liszt did.

Richard Wagner exhibited an even stronger admiration of Shakespeare, an idolization that overlapped with his admiration of Beethoven. The pair of artistic masters made a profound impression on Wagner and spurred his creativity.Footnote 14 Wagner was entranced by Beethoven, and he described his fascination after hearing one of Beethoven’s symphonies for the first time:

I soon conceived an image of [Beethoven] in my mind as a sublime and unique supernatural being, with whom none could compare. This image was associated in my brain with that of Shakespeare; in ecstatic dreams I met both of them, saw and spoke to them, and on awakening found myself bathed in tears.Footnote 15

Wagner’s vision correlated his reverence of Beethoven with his reverence of Shakespeare, an inspirational pairing that further develops in Wagner’s essay about an imagined pilgrimage to meet with Beethoven. In Wagner’s fantasized conversation, Beethoven speaks of creating a true musical drama to set before an audience, and Wagner asks Beethoven how it can be achieved:

“And how must one go to work”, [Wagner] hotly urged, “to bring such a musical drama about?” “As Shakespeare did, when he wrote his plays”, was the almost passionate answer.Footnote 16

The imagined exchange indicates Wagner’s belief that his musical hero would share his admiration for Shakespeare.Footnote 17 Even from a young age, Wagner drew from the thematic and poetic elements of Shakespeare’s works, writing a tragedy entitled Leubald und Adelaïde at the age of fifteen. He modified the plot of Hamlet to serve as the basis of his story and included elements of King Lear, Macbeth and Goethe’s Götz von Berlichingen, and ‘one of the chief characteristics of its poetical form [he] took from the pathetic, humorous and powerful language of Shakespeare’.Footnote 18 As these examples demonstrate, Shakespeare held a prominent position in the minds of the New German School leaders, and his powerful prose meshed with their music and aesthetics. MacDowell likely shared not only musical aesthetics with the New German School, but also cultural and artistic values that reflected a similar admiration for Shakespeare.

MacDowell seems to have agreed with Liszt and Wagner that ‘immortal personages’ were appropriate topics for symphonic poems. Beyond Hamlet and Ophelia., which marked his first foray into the genre of the symphonic poem, he set to music the figures and narratives of other significant works, demonstrating a similarity to Liszt and Wagner in his topicality. MacDowell followed his first symphonic poem with Lancelot und Elaine (after the poetry of Alfred Lord Tennyson), Lamia (after the poetry of John Keats) and Die Sarazenen and Die schöne Aldâ (both after The Song of Roland).Footnote 19 MacDowell’s symphonic poems depict the characters, moods and events surrounding the title figures and their stories. His tonal language alludes to that of Liszt and Wagner, with local chromaticism colouring discrete musical events while the overall forms are guided by tonal progressions suggesting the development of the drama and character transformation.

Throughout his career, MacDowell also composed several solo piano pieces that further reflect Germanic influences in the rich, complex harmonic language and descriptive titles. In a study on resonances between MacDowell’s piano pieces and the compositions of Richard Wagner, Francis Brancaleone presents detailed analyses of motives in MacDowell’s pieces that suggestively allude to Wagner’s music and style. Brancaleone outlines general features of Wagner’s compositional style that MacDowell had integrated into his own style, including melodies constructed of motives, harmony emanating from the polyphonic texture of motives, shifting sonorities of altered chords and evasion of the tonic.Footnote 20 Beyond these shared stylistic tendencies, Brancaleone identifies in several of MacDowell’s piano pieces direct quotations and allusive motives referencing Wagner’s music.Footnote 21 For example, in MacDowell’s ‘Erzählung’ (‘Story’), op. 17, no. 1, a motive recalls the ‘Glance’ motive from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. The motive appears at dramatic moments of MacDowell’s piece, and he integrates it into other passages by combining fragments of Wagner’s motive with his own. Brancaleone suggests that the allusion can support the interpretation of ‘Erzählung’ as a love story, perhaps an autobiographical story of MacDowell’s love for Marian Nevins, to whom he had proposed marriage in 1883, around the time of the piece’s composition.Footnote 22 While Brancaleone’s interpretation cannot be verified as MacDowell’s intention, it seems that Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde nevertheless carried great emotional meaning to MacDowell. In her autobiographical accounts, Marian MacDowell describes her husband’s response to his first encounter with Tristan und Isolde:

MacDowell wasn’t over twenty-five when he first heard TRISTAN AND ISOLDE in Frankfort [sic]. I remember feeling much disturbed when suddenly, after the opera was about half finished, he said, “Now I want to go”. It seemed to me rather dreadful to leave in the middle of the performance, and it would give the impression that we didn’t like the music, and I reproached him when we were outside, and he said, “I just couldn’t emotionally stay any longer. It’s so new and magnificent. Tomorrow night we will hear it again”.Footnote 23

Marian’s anecdote illustrates MacDowell’s powerful reaction to Wagner’s music drama and indicates how Wagnerian musical allusions imbue MacDowell’s creative output with additional layers of meaning.

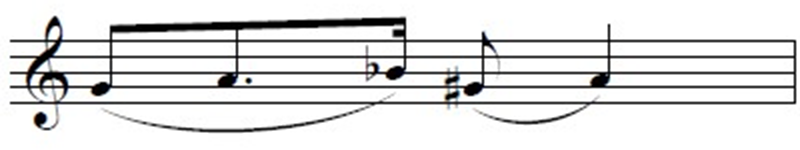

An allusion to Tristan und Isolde also appears in MacDowell’s Hamlet and Ophelia, suggesting that the themes of passion, death and tragedy in Wagner’s music drama may provide a lens for interpreting MacDowell’s Shakespearean adaptation. The transition section of the Hamlet movement exposition features the French horns repeating a motive reminiscent of a leitmotif from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde (Example 1). In her article on MacDowell’s programmatic aesthetic, Dolores Pesce identifies the motive in Hamlet as an allusion to the ‘Longing for Tristan’ leitmotif from Wagner’s drama and asserts that the allusion represents Hamlet becoming ‘distracted by love’.Footnote 24 Eric Chafe describes Wagner’s ‘Longing for Tristan’ leitmotif as a combination of the desire and glance motives, integrating the ideas of the transcendence of desire and the longing glances of lovers looking beyond the individual (Example 2).Footnote 25

Example 1. Tristan longing motive in MacDowell’s Hamlet movement, bars 70–77. Edward MacDowell, Hamlet. Ophelia. Zwei Gedichte für Grosses Orchester, op. 22 (New York: G. Schirmer, 1885).

Example 2. “Longing for Tristan” leitmotif in the Prelude to Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde.

The allusive motive recurs throughout MacDowell’s symphonic poem and effectively maps Tristan and Isolde’s tragic love onto the relationship of Hamlet and Ophelia, creating an intertextual connection that foregrounds the romantic dimension of Shakespeare’s characters. The significant Tristan allusion in MacDowell’s Hamlet demonstrates the depth of MacDowell’s aesthetic engagement with the New German School and perhaps also a German notion of Shakespeare. However, a distinctive English impression of Shakespeare adds another cultural dimension to MacDowell’s symphonic poem.

Henry Irving, Ellen Terry and Wagnerism in London

While the dramatic and musical style associated with the New German School may have had a direct impact on MacDowell’s Hamlet and Ophelia, a more specific Wagnerian aesthetic may have indirectly influenced MacDowell during his time in London. Throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century, Wagner’s music and ideas exploded through the Western world.Footnote 26 His progressive aesthetics attracted attention, and his music dramas gained wide-spread support from European audiences. In the 1870s, Wagner moved to Bayreuth and opened the Festspielhaus, which became the mainstay of realizing productions of his music dramas. By the time of his death in 1883 and for decades afterwards, the spirit of Wagner’s ideas spread through cultures around the world as the full-fledged movement of Wagnerism. Despite his controversial musical and political ideologies, many followers regarded Wagner as ‘the Master’. Wagner’s ideas of Gesamtkunstwerk and Zukunftsmusik spread well beyond Germany and infused many aspects of cultural life in various societies.

The significance of the musical allusion to Tristan und Isolde in MacDowell’s Hamlet is indicative of the Wagnerian thought that permeated theatrical, artistic and musical life throughout the Western world. As Marian MacDowell’s anecdote indicated, the MacDowells first attended a performance of Tristan und Isolde in Frankfurt, but their honeymoon immersed them in the cultural life of London, a city also heavily influenced by Wagnerism. By understanding these cultural dimensions in interpreting MacDowell’s symphonic poem, the composition can communicate not just Wagnerian themes but traces of London’s historical culture as well.

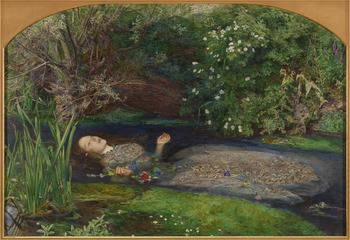

The presence of Wagner and Wagnerism in England begins with the composer’s visit to London in 1855. He conducted several concerts with the Philharmonic Society of London, and the young Queen Victoria and Prince Albert attended one of the concerts with the programme including the Tannhäuser overture.Footnote 27 By the 1870s and 80s, Wagner’s music, mythology and aesthetics had become deeply infused in London culture and society. His works and style were assimilated into English culture as a reflection of the Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic movements, sharing ideals such as the promotion of the aesthetic value of the arts over their socio-political roles, an emphasis on beauty, a style of suggestion and symbolism, sensuality and synaesthesia, escapism through the arts, and merging the arts of different media. In his book on Wagnerism, Alex Ross draws connections between the Pre-Raphaelite ‘brand of progressive nostalgia’ and ‘Wagner’s own blend of revolution and reaction’: both perspectives pursued ‘the revivification of an idealized past’ as a way to counter the stifling industrialized present.Footnote 28 Ross further describes how these perspectives manifest in artwork, highlighting, for example, the ways in which the vivid colours and sensual subjects of Pre-Raphaelite paintings ‘bring to mind the hedonistic harmonies of Wagner’s Venusberg and his Tristan love scene’.Footnote 29 The rich resonances between Shakespearean subjects and those of Pre-Raphaelite paintings can be seen in works such as John Everett Millais’s Ophelia (1852) and John William Waterhouse’s Ophelia (1894) (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Ophelia, 1852, John Everett Millais. Tate, 1894. Photo: Tate. Public domain.

Figure 3. Ophelia, 1894, John William Waterhouse. Public domain.

Pre-Raphaelite art and Wagner’s works bled into the English literary world as well, with themes echoing Shakespearean and Arthurian literature. An Arthurian revival following the 1816 publication of new editions of Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur – which included the stories of Arthur, Merlin, Lancelot, Guinevere and the lovers Tristram and Iseult – converged with the Pre-Raphaelite interest in medieval aesthetic, and these legendary tales echo in the mythology of Wagner’s music dramas.Footnote 30 Furthermore, poetry engaging with Wagner’s subjects, biographical writings of Wagner, and English translations and analyses of his prose and music appeared in the 1880s and onward. For example, beginning in 1887, the London Wagner Society published a journal called The Meister, modelled after the Parisian Revue wagnéreinne.Footnote 31 The Meister was edited by William Ashton Ellis, who also translated Wagner’s prose essays into English. British-German philosopher Houston Stewart Chamberlain wrote commentaries on several of Wagner’s musical works, published a biography of Wagner in 1895, and married Wagner’s daughter, Eva von Bülow. George Bernard Shaw, a playwright and critic active in London in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, published a Marxist analysis of the Ring cycle entitled The Perfect Wagnerite in 1898. The spirit of Wagnerism pervading London’s artistic and literary world seeped into the theatrical world as well. The renowned actors Henry Irving and Ellen Terry were at the height of their fame in the 1880s, and their powerful acting style resonated with the drama and sensuality of Wagnerian aesthetics.

In 1884, just a year after Wagner’s death, MacDowell experienced the popularity of Irving and Terry in the rich London culture steeped in Wagnerism. MacDowell returned to the US in June 1884 to marry Marian Nevins, a former American piano student he had taught in Frankfurt beginning in 1880. The wedding took place on the Nevins family farm in Connecticut on July 21, 1884, and after their marriage, the newlyweds embarked on their honeymoon in London.Footnote 32 They attended several performances of Shakespeare plays during this trip and subsequent trips to London, where they were immersed in the cultural atmosphere celebrating the famous actors Henry Irving and Ellen Terry. In her autobiographical writings, Marian MacDowell recalled their honeymoon trip and the significance of their theatrical experiences:

that first summer was in many ways the most exciting one we ever had from an artistic standpoint. It was in the very height of the fame of Henry Irving and Ellen Terry, the latter in her 30s was one of the most enchanting actresses that one could even dream of … We went to see them in MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING. We were deliriously enchanted and wanted to go over and over again but we were stopped by the fact that the decent seats were a guinea and as my sight was never very good we were forced to take these instead of going into the gallery as would have been the case ordinarily. We were dismayed to think that we had this great opportunity and could not avail ourselves of it.Footnote 33

To overcome the financial burdens preventing them from fully enjoying the theatre, the MacDowells decided to sell some of the silver inherited from Marian’s family. They received ‘quite a good sum for it; enough anyway to allow [them] to go to see Terry and Irving in pretty nearly everything they were playing’.Footnote 34 In addition to Much Ado About Nothing, the MacDowells reportedly also attended performances of Hamlet and Othello. After their honeymoon, the MacDowells returned to Frankfurt, at which point Edward turned to Shakespeare’s Hamlet as the subject of a musical composition. The title page of MacDowell’s Hamlet. Ophelia. Zwei Gedichte für grosses Orchester bears the inscription ‘Henry Irving und Ellen Terry in Verehrung gewidmet’ – ‘dedicated to Henry Irving and Ellen Terry in admiration’. MacDowell’s dedication indicates a dramatic and creative connection between his music and the two famous Shakespearean actors, suggesting that MacDowell’s encounters with Irving and Terry in the 1884 London cultural scene can provide an interpretive lens for his Hamlet and Ophelia symphonic poem.

Irving and Terry offered a unique enactment of Hamlet and Ophelia that highlighted Wagnerian nuances of tragic romance and profoundly impacted London’s theatrical scene. In 1871, Irving took the role of lead actor at the Lyceum Theatre, managed by Hezekiah Bateman.Footnote 35 Irving decided to reintroduce Shakespearean plays at the Lyceum in 1874, beginning with a successful 200-night run of Hamlet. He made many cuts to Shakespeare’s prose to shape his interpretation of the play, reducing Shakespeare’s 20 scenes to 13, removing the character of Fortinbras, and diminishing the roles of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.Footnote 36 His portrayal of Hamlet focused on creating ‘a complex, mysterious but believable human being’.Footnote 37 Irving initially starred as Hamlet opposite Isabel Bateman, the daughter of Hezekiah Bateman, as Ophelia. In 1878, after Hezekiah Bateman had passed away and his wife had transferred the lease to the Lyceum to Henry Irving, Ellen Terry took on the role of Ophelia. Terry’s first performance of Hamlet at the Lyceum with Henry Irving took place on 30 December 1878, and the next day’s reviews ‘prais[ed] her “exquisite” Ophelia and point[ed] to the “utmost importance” of her support for Hamlet’.Footnote 38 The foil of Terry’s effective portrayal of Ophelia enabled Irving to convey his interpretation emphasizing the role of love in Hamlet’s life and the turmoil of love gone awry. In Irving’s conception of the character, ‘Hamlet is a fundamentally sane man whose sensitive imagination excites a kind of hysteria at moments of stress’.Footnote 39 At this point in 1878, Irving adapted his acting edition to enhance the romantic dimension of the play: ‘When he was to play opposite Ellen Terry, [Irving] would restore some passages so as to emphasize Hamlet’s longing for Ophelia (a longing he must resist), which he had taken out when playing opposite Isabel Bateman’.Footnote 40 Irving’s conception of Hamlet’s longing and tenderness is especially meaningful to the nunnery scene, when Hamlet’s words at first seem to be a cruel rejection of Ophelia and her love:

Henry Irving says that in such speeches as ‘I loved you not’, Hamlet is using ‘the surgeon’s knife’ and that when he speaks the self-condemning lines which accompany his advice to go to a nunnery, he is attempting to ‘snatch at and throw to the heart-pierced maiden some strange, morbid consolation’. In his desire to show the frustrated longing for Ophelia which he thought lay behind Hamlet’s assumed severity, Irving engaged in what [John] Gielgud has ironically described as ‘affectionate by-play behind Ophelia’s back’. Ellen Terry, Irving’s Ophelia, who approved of the ‘love poem’ which Irving made of the part, exclaims: ‘With what passionate longing his hands hovered over Ophelia at her words: Rich gifts wax poor when givers prove unkind’.Footnote 41

Irving’s tragic conception of the ill-fated love between Hamlet and Ophelia is reminiscent of the tragedy of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, resonating with the wide-reaching influence of Wagnerism in London. The pairing of Henry Irving and Ellen Terry, with their pronounced talent and their intense interactions on-stage, thus created a precedent for London Shakespearean productions and the city’s theatrical world as a whole.

The link between MacDowell’s creativity and that of Irving and Terry is evidenced in a letter that MacDowell wrote to Irving asking for the actor’s permission for the dedication of the symphonic poem (Appendix 1). In the letter, MacDowell expresses his admiration for the actor and the impact Irving had on MacDowell’s conception of Hamlet. While MacDowell may have approached his music with other sources of Shakespearean inspiration, his letter shows that Irving and Terry were foremost in his imagination:

Having seen Miss Terry and yourself a number of times at the Lyceum in Shaksperian [sic] plays, I tried on my return to Germany to compose some pieces using Shaksperian characters as subjects. Now as the compositions were first thought of after having seen Miss Terry and yourself I would be very much pleased if you would allow me to dedicate them to you, and with Miss Terry’s permission to her also.Footnote 42

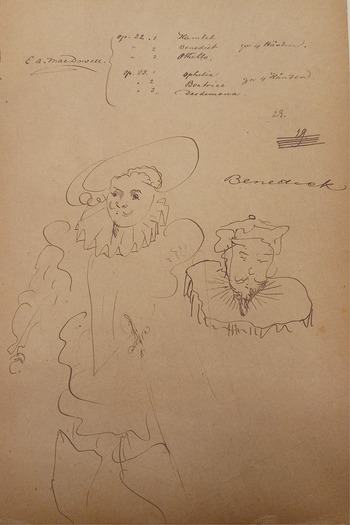

MacDowell’s letter to Irving also reveals how he originally planned to organize his Shakespearean music. He evidently wanted to create two separate works, an opus 22 and an opus 23, to be dedicated to Irving and Terry respectively. MacDowell’s sketchbooks provide further clues regarding his initial conception of his Shakespearean programmatic music. His notes on the back cover of his sketchbook outline a pair of pieces for four-hand piano: Opus 22 would consist of three parts alluding to Hamlet, Benedict and Othello, respectively, and opus 23 would also consist of three parts alluding to Ophelia, Beatrice and Desdemona (Figure 4).Footnote 43 Two drawings labelled ‘Benedick’ beneath these notes offer an image of MacDowell’s visual imagination of Shakespearean characters alongside his musical imagination. The facial features and costuming of the figure in MacDowell’s illustration bear striking similarities to a watercolour image of Henry Irving as Benedict by caricaturist Carlo Pellegrini, similarities that point to the importance of the visual aspect in MacDowell’s imagination (Figure 5). Furthermore, the gendered separation outlined in MacDowell’s original plan strengthens the association between the music and the Shakespearean actors, with the male characters portrayed in the piece dedicated to Henry Irving and the female characters in the piece dedicated to Ellen Terry. By recognizing the gendered distinction, it might be understood that MacDowell’s music represents not simply the Shakespearean characters but rather the distinct interpretations of these characters embodied in the acting of Irving and Terry and their resonance with Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde. While MacDowell’s original plan consisted of six Shakespearean characters, only Hamlet and Ophelia feature in his final symphonic poem (Figure 6).Footnote 44 Indeed, identifying the musical themes embodying Hamlet and Ophelia allows for the simultaneous imagination of Irving and Terry enacting the characters in a Wagnerian aesthetic in MacDowell’s musical imagination. It should be noted that the following analysis does not seek to claim that nineteenth-century listeners interpreted MacDowell’s music in the same ways. While contemporary audiences may have had similar imaginations, this analysis seeks to synthesize the layers of MacDowell’s experiences and inspirations to present the current reader with a new way of listening to the symphonic poem that captures the dynamic nineteenth-century multi-cultural dimensions of MacDowell’s composition.

Figure 4. Inside back cover of MacDowell’s sketchbook, outlining two Shakespearean compositions and illustrations of Benedict from Much Ado About Nothing. Library of Congress, EMMC, Box 4, ‘E. A. MacDowell, First Sketches, 18.11.1884’.

Figure 5. Sir Henry Irving as Benedict from Much Ado About Nothing, watercolour by Carlo Pellegrini, 1883. The costuming and facial features bear resemblances to those in MacDowell’s sketches in Figure 4. National Portrait Gallery, Primary Collection, NPG 5073. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Figure 6. MacDowell’s title page to Hamlet. Ophelia. Zwei Gedichte für grosses Orchester bearing the inscription at the top: ‘Henry Irving und Ellen Terry in Verehrung gewidmet’ – ‘dedicated to Henry Irving and Ellen Terry in admiration’. Library of Congress, EMMC, Box 8, folder 1.

Interpreting MacDowell’s Hamlet and Ophelia

MacDowell’s symphonic poem expresses the themes of Shakespeare’s drama and the subjectivities of the tragedy’s characters. Each movement of the symphonic poem might be interpreted as a character sketch representing Hamlet and Ophelia respectively, though elements of narrativity may also be interpreted in the musical trajectory and the interaction of distinctive character themes. In this sense, it follows in the footsteps of Liszt’s Faust Symphony, which creates musical portraits of Faust, Gretchen and Mephistopheles in each movement while also suggesting narrative threads through thematic transformation and interplay.Footnote 45 The characters of MacDowell’s symphonic poem may be understood through persona theory, a method for ‘hypothesizing a fictional or virtual persona in the music whom listeners experience as an agent expressing genuine emotion’.Footnote 46 As the music unfolds, listeners may identify distinctive themes and imagine the persona of each character suggested by the instruments, timbre and musical style.

A dark and atmospheric introduction opens the Hamlet movement, evoking the setting of Elsinore and the suspenseful mood of Shakespeare’s narrative as Hamlet meets the ghost of his father at midnight. The slow introduction abruptly transitions to the Allegro agitato section, growing in intensity as violin trills build up to the fortissimo primary theme, which can be interpreted as Hamlet’s persona (Example 3). Several musical elements, such as the high energy and fast tempo, trills and grace note flourishes and accented rhythms, suggest Hamlet’s despair over the death of his father and agitation over his conflicted pursuit of revenge. Hamlet’s musical subjectivity can be interpreted as a distressed, unsettled character, with the key of D minor connecting to the element of suffering.Footnote 47 As listeners experience Hamlet’s musical persona in the primary theme, they might specifically imagine Henry Irving’s portrayal of Hamlet, drawing on MacDowell’s dedication to the prestigious and innovative actor and connecting the music to MacDowell’s experiences of 1884 London (Figure 7). In this case, the Hamlet in MacDowell’s music is Irving’s impassioned Hamlet, anguished by the ill-fated love he shares with Ophelia, and also reflecting the tragic character of Wagner’s Tristan.

Example 3. Hamlet theme, Hamlet movement, bars 29–43. Edward MacDowell, Hamlet. Ophelia. Zwei Gedichte für Grosses Orchester, op. 22 (New York: G. Schirmer, 1885).

Figure 7. ‘The Late Sir Henry Irving as Hamlet’, portrait by Edwin Long. New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Billy Rose Theatre Collection.

As the foil to Hamlet’s primary theme, the secondary theme conveys the persona of Ophelia (Example 4). In the key of F major, Ophelia’s theme takes a distinctive mediant relationship to Hamlet’s D minor, and the smooth, lyrical melody contrasts against the agitated energy of Hamlet’s persona. This theme is confirmed as Ophelia’s persona when it becomes the main theme of the second movement titled ‘Ophelia’, though the listener may identify Ophelia’s persona in the nineteenth-century custom of considering the secondary theme to be feminine:

The second theme, on the other hand, serves as contrast to the first, energetic statement, though dependent on and determined by it. It is of a more tender nature, flexibly rather than emphatically constructed – in a way, the feminine as opposed to the preceding masculine.Footnote 48

Example 4. Ophelia theme, Hamlet movement, bars 98–121. Edward MacDowell, Hamlet. Ophelia. Zwei Gedichte für Grosses Orchester, op. 22 (New York: G. Schirmer, 1885).

Furthermore, the lush violin timbre and woodwind accompaniment may recall the woodwinds of Gretchen’s theme in Liszt’s Faust Symphony and invoke a conventional sense of femininity. Again, the listener might map the persona of Ellen Terry onto the musical representation of Ophelia, imagining the actress’s distinct embodiment of Shakespeare’s character and her resonance with the Wagnerian tragic love of Isolde (Figure 8).

Figure 8. ‘Ellen Terry as Ophelia in “Hamlet”’, platinum print by Window & Grove, 1878, published 1906. National Portrait Gallery, NPG – Ax131301. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Imagining Irving and Terry as the Hamlet and Ophelia in the music takes on greater significance alongside the ‘Longing for Tristan’ allusion that first appears in the transition. The Wagnerian motive highlights the tragic romantic dimension of the relationship between Hamlet and Ophelia, a tragic romance that infused the performances by Irving and Terry. Even off-stage, the actors fascinated audiences with their allure, offering a sense of romance and intrigue. The MacDowells were evidently influenced by their experiences of Irving and Terry in London’s lively atmosphere:

Both [Irving and Terry] had been successful prior to their partnership, but together they achieved a rare artistic synergy. Rumors swirled about their possible romantic attachment (he was separated from his wife and she was separated from the second of three husbands when the MacDowells saw them), which only added to the intensity of their onstage chemistry. Small wonder that Edward’s creativity was inspired by their performances.Footnote 49

The highlighted element of tragic love has a profound impact on the musical interpretation of Shakespeare’s drama, guiding listeners to imagine the multi-dimensional characters in MacDowell’s symphonic poem. Hamlet’s musical theme is composed of layers of Irving’s enactment of Hamlet, Irving himself and Tristan, and Ophelia’s theme consists of Terry’s Ophelia, Terry herself and Isolde (Figure 9). The romanticized figures of Edward and Marian MacDowell might even be mapped onto the characters of Hamlet and Ophelia by recognizing the intimate setting of their honeymoon.

Figure 9. Henry Irving and Ellen Terry in the nunnery scene from William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, black and white lithograph of a painting by Edward H. Bell, 1879. Public domain.

To be sure, the Hamlet movement and the Ophelia movement can function independently as stand-alone pieces; conductors like Frank Van der Stucken, discussed below, successfully programmed one movement or the other in concert. Yet the two movements share important musical links, especially as regards Ophelia’s thematic material. Structured in a ternary form, the Ophelia movement features Ophelia’s theme in the opening and closing sections and the Tristan longing motive in the contrasting middle section, though Hamlet’s theme does not appear. The Tristan motive appears for the first time in the flute, clarinet and violin, and later in the violin and viola, infusing the Ophelia movement with a sense of desire reciprocating the longing in the Hamlet movement. Ophelia’s theme recurs in variations throughout the movement, appearing in different registers and timbres, and with different textures of accompaniment, perhaps illustrating the onset of her madness and tragic death.Footnote 50

While some aspects of this analysis may have resonated with nineteenth-century audiences, the interpretations laid out here serve to bring together the various dimensions introduced throughout this article to engage the reader in an imaginative listening experience steeped in MacDowell’s creative background. Recognizing the significance of the layered cultural expressions allows listeners to interpret the characters and narratives in the symphonic poem more meaningfully, and it also facilitates an understanding of how MacDowell’s Hamlet and Ophelia functions as a microcosm of cultural life in the late nineteenth century. The musical Hamlet and Ophelia illustrate MacDowell’s conceptions of the Shakespearean characters, and the Wagnerian allusion highlights the tragic love between them. The music and its layers of meaning invite listeners to imagine Hamlet and Ophelia channeling the emotion of Tristan and Isolde and the late nineteenth-century drama of Irving and Terry. MacDowell’s symphonic poem thus serves as a microcosm of the complexity of cultural life at the time, drawing inspiration from various sources and adapting ideas to create something new. The final layer of Hamlet and Ophelia to be explored is the US identity it assumed and represented as a featured composition in Frank Van der Stucken’s American Festival. In this sense, the microcosm of MacDowell’s symphonic poem reflects the broader trends of cultural transfer that influenced US culture at the end of the nineteenth century. The final section of this article explores the ideas circulating in the US musical scene of the late nineteenth century and the position of MacDowell’s Hamlet and Ophelia within that scene.

Wagnerism in the US and the American Composers’ Concert Movement

As described at the beginning of this article, US culture-bearers sought to define a unique national identity, and musicians pursued efforts to express this distinctive identity through music. Many musicians turned to standards of European musical life as a model, and US music identity fell in the tension between imitating European style and striving for ‘Americanism’.Footnote 51 MacDowell’s Hamlet and Ophelia demonstrates this tension through its Germanic influences and Wagnerian allusions coupled with MacDowell’s own American identity. In this way MacDowell’s symphonic poem offers a representation of the broader tensions in US musical identity, explored here through the efforts of the American Composers’ Concert Movement to elevate American musicians over the prevalence of Wagnerism and other European influences in the US.

Just as Wagnerism permeated the cultural life of London, the Wagnerian aesthetic and intrigue infused US culture in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Wagnerism spread through the US, largely through the activities of conductors, including Carl Bergmann and Theodore Thomas, and music critics, such as William Apthorp and Henry Krehbiel. Carl Bergmann was of German origin and moved to New York in 1849. As conductor of the New York Philharmonic Society orchestra in 1855, he achieved success in presenting performances of Wagner’s music. Bergmann gave the US its first taste of Wagner’s music in 1852 and conducted the first all-Wagner concert in the US in 1853. He also conducted the first hearing of a complete Wagner opera in the US with his April 1859 performance of Tannhäuser at the New York Stadt Theater.Footnote 52

German-born conductor Theodore Thomas emerged as another prominent US culture-bearer and supporter of the New German School. In May 1862, he conducted the first US performance of Wagner’s overture to Die fliegende Holländer, reflecting Bergmann’s approach in promoting progressive New German School works in his concerts. Thomas sought to refine his programming formula combining serious and light music – ‘a mixture of daring and prudence that would not just please the public but challenge, educate, and uplift it’.Footnote 53 Realizing his programming formula, he used Beethoven and Wagner as his ‘pillars’ to attract and educate audiences and introduce them to new repertoire.Footnote 54 Thomas focused much of his attention on audiences in New York, Cincinnati and Chicago, and, beginning in 1869, he toured with his orchestra throughout the US, giving concerts in several cities along what would later be called the ‘Thomas Highway’.Footnote 55

The emphasis placed on Wagner, the New German School and European composers in general contributed to the question of US national musical identity. Musical life in the US featured a great deal of European music while the music of US composers received little attention. The American Composers’ Concert movement arose in response to the dominance of Wagnerism and European music, seeking to elevate the status of music by US musicians. Through the programming decisions and promotional efforts of the American Composers’ Concert movement, the national and cultural dimensions of MacDowell’s symphonic poem took on new meaning in the evolving conception of national identity. Just as the American Festival positioned Hamlet and Ophelia and its layers of cultural influence as a model of American music, the American Composers’ Concert movement overall asserted an American identity through the music of US composers adapting and integrating diverse cultural ideas into something new.

The American Composers’ Concert movement began in the 1880s to address the prevalence of European music in the United States. Throughout the nineteenth century, the majority of concerts in the US presented European masterpieces. Even US composers of the time cultivated a cosmopolitan style, infusing their works with the Germanic sounds familiar to US audiences. As the United States entered the 1880s, though, US musicians sought a more distinctive identity and public recognition. After the nation’s centennial in 1876, a spirit of Americanism grew alongside measures of trade protectionism to promote domestic interests. This American spirit extended into the musical realm of the nation with sentiments to decentre the European dominance in performances. Activists advocated for the works of US composers by programming concerts consisting exclusively of American music. In his book on the American Composers’ Concerts movement, E. Douglas Bomberger traces the motivations and strategies of activist organizations.Footnote 56 Founded in 1876, the Music Teachers’ National Association gathered to exchange and broaden cultural ideas and to foster social interaction in their musical networks. In 1883, the organization moved toward advocacy and initiated an agenda to recognize American composers. The agenda led to the first American Composers’ Concert on 3 July 1884, organized by Calixa Lavallée at the MTNA convention in Cleveland, OH. Consisting entirely of works by US composers, the programme featured pieces such as Arthur Foote’s Gavotte, John Knowles Paine’s Spring Idyll and George W. Chadwick’s Scherzino, with Lavallée himself performing on piano. The MTNA continued to hold such concerts at their annual conventions, performing new songs, piano pieces and chamber works of US composers.

In 1885, Texas-born Frank Van der Stucken introduced orchestral repertoire into the American Composers’ Concert movement. Though also a successful composer, Van der Stucken gained renown as a conductor, succeeding Leopold Damrosch as conductor of New York’s Arion Society in 1884. Directing the German-American singing society gave Van der Stucken the social and financial backing to pursue his performance endeavours. Van der Stucken strove to present new compositions to audiences, organizing a series of ‘Novelty Concerts’ during the 1884–85 concert season to feature the performances of new orchestral works by composers such as Grieg, Tchaikovsky, Massenet and Dvořák. The last of the four concerts in the series, held on 31 March 1885, consisted entirely of American compositions. It included John Knowles Paine’s Prelude to Oedipus Rex, Dudley Buck’s Overture to Scott’s Marmion, George Templeton Strong’s Symphonic Poem to La Motte-Fouqué’s Undine and the US premiere of MacDowell’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in A minor (second and third movements), among other pieces. The concert was a success, and critics praised Van der Stucken’s execution of the concert and ruminated on the future of US music. Van der Stucken continued his Novelty Concerts, featuring both US and European compositions, over the next few years, while the MTNA continued holding American concerts at their conventions.

The next substantial step for the American Composers’ Concert movement occurred in November 1887 with Van der Stucken’s American Festival, a series of five concerts to be held in New York. Van der Stucken organized the music to devote three evening concerts to orchestral and choral-orchestral works, an evening of chamber music and an evening of organ, piano and choral works. By structuring the festival in such a way, Van der Stucken provided space for recognizing US composers of each genre. The first concert of the American Festival, held at Chickering Hall on November 15, 1887, featured John Knowles Paine’s ‘Spring’ Symphony, George E. Whiting’s Air for baritone from The Tale of the Viking, Henry Holden Huss’s Rhapsody for pianoforte and orchestra, L.A. Russell’s Pastoral for soprano solo, chorus and orchestra, MacDowell’s Hamlet and Harry Rowe Shelley’s Dance of the Egyptian Maidens. Works by composers such as Arthur Foote, Dudley Buck, Johann Beck, George W. Chadwick and Van der Stucken himself appeared on the programmes of the remaining four concerts.

The position of Hamlet on the programme of Frank Van der Stucken’s first American Festival concert suggests that MacDowell and his composition represented ideal features of US music that the conductor and critics sought to promote. Van der Stucken composed Shakespearean music of his own, and his support of MacDowell’s Hamlet suggests the popularity of an Americanized Shakespeare that would be accessible to all audiences and foster US identity.Footnote 57 A review of the concert indicates that Van der Stucken’s efforts to elevate US composers through such concerts were highly esteemed, and MacDowell’s Hamlet met considerable success:

The first of Mr. Frank Van der Stucken’s concerts of American music was given at Chickering Hall last evening before an audience that was both large and enthusiastic … It has been an important part of Mr. Van der Stucken’s practice as a conductor to present new music, and he has shown uncommon generosity toward American composers, playing their works frequently and with loving fidelity. The fruits of such labor must ripen sooner or later, and native composers will be encouraged to stretch their unfledged wings in the future as they have not been in the past. American musicians and all who hope to see the beginning of an American school of music owe Mr. Van der Stucken a substantial debt of gratitude … [John Knowles Paine’s “Spring Symphony”] shared with E. A. Macdowell’s symphonic poem, “Hamlet”, the honors of the evening. The latter is, however, the more striking composition of the two. Its purpose is clear and is distinctly exposed. The stormy character of the opening bars fittingly portrays the conflict of emotions in the princely Dane, and the frequent passionate bursts ending in abrupt and suddenly suspended fortissimo are admirably expressive, while the cantabile music in melody and movement signifies clearly the melancholy and love of Hamlet. The scoring is strong and richly colored, and on the whole the composition is one of no small merit. Mr. Macdowell’s abilities have been recognized abroad, and he is now an instructor in one of the German conservatories … Footnote 58

As the reviewer indicates, Van der Stucken’s promotion of US composers and the work of these musicians contributed to the formation of a distinct US musical national identity. The reviewer’s praise of Hamlet suggests that, in the eyes of the public and music critics, MacDowell held a promising position to achieve the identity of this US school of music. MacDowell is presented as a composer of quality music, and the description of Hamlet reflects contemporary reception of piece’s expressive power and dramatic musical characterization. This distinction elevates MacDowell as a positive representation of US music. Furthermore, the reviewer illustrates the value of the special attention Van der Stucken gave to US composers through his organization of such concerts. As another critic notes, Van der Stucken’s programming presented important opportunities and ideal settings for the performance of US musical works:

the programs for the five concerts arranged by Mr. Frank Van der Stucken, the energetic and aspiring young conductor, were made up entirely of the works of native American composers. Editorially we speak at length of the good effect of these concerts on the cause of a future American national musical art, and it remains for us here only to say what was done and shown at the three entertainments so far given, and to state at the outset that the performances under Mr. Van der Stucken’s careful and almost loving guidance, and with his sympathetic interpretation by a large and admirable orchestra and with competent soloists, gave the works of our American writers a chance to be heard under most advantageous circumstances … The most important work on the program was E. A. MacDowell’s (now living in Wiesbaden, Germany) symphonic poem in D minor, entitled ‘Hamlet’. It is a pendant to the same composer’s ‘Ophelia’, which was brought out by Mr. Van der Stucken last year. It is strong and manly in conception, noble in invention and effectively orchestrated.Footnote 59

As the reviewer also notes, Van der Stucken’s work contributed significantly towards the ‘cause of a future American national musical art’, claiming MacDowell’s Hamlet to be the most important piece of the occasion. The reviewer makes a suggestive comment about the perceived masculinity of Hamlet, which is ‘strong and manly in conception’, indicating a gendered dimension to the Shakespearean symphonic poem and perhaps insinuating that strength and virility reflect an ideal US national identity. Van der Stucken had presented MacDowell’s Ophelia the previous year, introducing the US public to the other half of MacDowell’s Shakespearean music. A review of the Ophelia performance offers similar conceptions of the music’s implications of national identity and gendered characterization:

The novelties of the evening were without exception interesting. Mr. McDowell’s [sic] symphonic poem had a double significance – as a poem of intrinsically beautiful music, and as an indication that though Mr. Van der Stucken has changed the style of his concerts somewhat, he adheres to his patriotic and admirable purpose of encouraging American composers. Mr. McDowell is bringing honor to his native land. It is, perhaps, to be regretted that in order to win the attention which he deserves he is obliged to give his activities to Germany, but his influence on the American movement will be felt so long as we have conductors who second him as Mr. Van der Stucken has done … Mr. McDowell has invented beautiful melodies and treated them effectively – melodies, moreover, which have a poetical mood and a characteristic. One cannot say that the composer has given musical delineation to all the elements in Ophelia’s character, but the sweet melancholy is there, the tender soul and the modest, maidenly mind turned awry by sorrows undeserved.Footnote 60

The reviewer praises MacDowell’s musical creativity, his role as a US composer elevating the music of his native country, and the noble efforts of Van der Stucken to bring such awareness to US musicians.

However, while American Composers’ Concerts arguably helped to bolster his reputation and the reputation of US composers overall, MacDowell’s attitude towards the ideals they conveyed was ambivalent. He initially did not object to the inclusion of his works in American Composers’ Concerts, but as they continued into the 1890s, he sought to distance himself from them. MacDowell asserted that the practice of programming concerts made up solely of US music effectively isolated national music from the international world of art in a way that ‘encouraged an unhealthy musical protectionism’.Footnote 61 As a result, music would be programmed based on national character rather than aesthetic merit, which ultimately skewed the standard of judgment for US works. Musicians, audiences and the press would recognize a concert’s status as ‘American’ and, depending on their opinions of American concerts, would praise or condemn the music without even hearing it. MacDowell articulated his views on the aesthetic and political motivations of such concerts of US music:

Another matter that I think has been to the detriment of individual effort in composition for many years is that kind of Americanism in art that believes in ‘American’ concerts and the like. An ‘American’ concert is, in my eyes, an abomination, for the simple reason that it is unfair to the American. Such a concert offers no standard of judgment, owing to our want of familiarity with the works presented. Then, if our work is preferred to another, it only does harm to the weaker work, without helping the stronger one to any fixed value. Added to this, an ‘American’ concert is a direct bid for leniency on the part of the public, which, I need hardly say, is immediately recognized by it. American music must and will take its position in the world of art by comparison with the only standard we know – that of the work of the world’s great masters, and not by that of other works equally unknown to the world. In other words, we crave comparison with the best in art, not only the best in America. If our musical societies would agree never to give concerts composed exclusively of American works, but, on the other hand, would make it a rule never to give a concert without at least one American composition on the programme, I am sure that the result would justify my position in the matter.Footnote 62

From MacDowell’s perspective, concerts should include works by US composers as well as European composers, recognizing the best selections of all great music, not just the best of US music. In this way, concert programming would avoid the exclusivity and protectionism that MacDowell found to be detrimental to US music.

The emphasis placed on the pursuit of a distinctive US identity downplayed the nuanced multi-cultural dimensions of many composers and their music, and the reception of US music tended to highlight national identity more so than musical elements. As MacDowell’s changing perspectives towards American Composers’ Concerts indicate, the nationalistic agenda neglected genuine assessments of the music’s aesthetic quality and the rich diversity of the composers’ backgrounds. MacDowell’s version of national identity instead embraced diversity and immersive cosmopolitanism, reaching toward the element of universality in musical style. Through this view of national identity, the nation is conceived as a cultural entity made up of many parts. It recognizes the diverse backgrounds of US peoples as valuable contributions to the identity of the nation. As Hamlet reveals, the layers of meaning accrued through the music’s creation and reception demonstrate the entangled intersection of the seemingly opposite poles of nationalism and universality and illuminate the complexity underlying MacDowell’s status as more than merely a ‘cosmopolitan American composer’.

Hamlet as Microcosm of Late Nineteenth-Century US Culture

The many cultural layers of the composition and reception of MacDowell’s symphonic poem foreground issues of national identity and aesthetic value. Exploring these issues through the lens of Hamlet reveals the various dimensions of the composer: as a multi-cultural composer exhibiting English, French and Germanic elements in his work, as a US composer upheld as an icon of national identity, and as a proponent of aesthetic value transcending national identity. MacDowell’s experiences in London and Germany contributed to his composition, and traces of these cultural intercrossings can be perceived in the music and lend meaning to the piece’s performance in the United States. Hamlet highlights the ways in which the composer’s ideas and experiences converged in his music, infusing his creative output with elements of cultures on both sides of the Atlantic. The inclusion of MacDowell’s symphonic poem in Frank Van der Stucken’s American Festival contradicts nationalistic exclusivity but supports the adaptivity and entangled histories of national identity. Hamlet also tells a deeper and broader story of national identity and aesthetic value, illuminating the flow of various ideas through various cultures and the ways in which these ideas transformed and intertwined throughout the process. Transatlantic concepts of Shakespearean drama and musical ideologies circulate around Hamlet, its composition and its US performance and reception. In this way, MacDowell’s symphonic poem serves as a microcosm of the true hybridity of the adaptive US cultural identity of the late nineteenth century.

Hamlet is representative of MacDowell’s general output, and many of his other compositions such as Lancelot und Elaine or his Indian Suite reflect similar nuanced multi-cultural backgrounds and layered musical meanings offering further snapshots of the close of the nineteenth century. Furthermore, while MacDowell is the primary creative agent in the microcosm of Hamlet, many other agents interacted with him and his ideas to shape musical life. The wide-reaching influence of composers such as Franz Liszt, Richard Wagner and Joachim Raff spread to the United States and shaped the aesthetic landscape of growing musical institutions in the US. Writers of the European press played a key role in the development of US media and the different ideological threads communicated to the public, contributing to the exchange and adaptation of cultural ideas. Beyond the realm of music, the international travel of actors and transatlantic dissemination of Shakespearean interpretations further contributed to the transformative flow of artistic and dramatic expression. In autumn of 1880, US Shakespearean actor Edwin Booth travelled to Britain and performed Othello with Henry Irving, alternating the roles of Othello and Iago with Irving while Ellen Terry played Desdemona. In 1883, Irving and Terry embarked on their first tour in the US. They arrived at Staten Island on 21 October 1883, and they performed in cities including Indianapolis, Chicago, St. Louis, Baltimore, Boston and Pittsburgh. The two actors entranced US audiences and introduced them to their interpretation of Shakespeare popularized in London. Shakespeare’s works have spread around the world since the 1600s, and his prose has evolved and shifted through different media to tell stories of cultural and national identity.

The musical microcosm of Hamlet reveals the intersection and layering of multiple processes of exchange that occur many times over, shedding light on the complex network of ideas and values from different cultures combining and transforming as they interact. MacDowell’s composition illustrates just one such story from the late nineteenth century, tracing multiple cultural threads and following the intercrossings to elucidate and explore their impacts. Examining the cultural layers of a musical composition allows scholars to look more critically at the history of musical identity in the US. Applying a similar approach to music and composers of rich cultural backgrounds active in the formative period of the nation’s development – such as John Knowles Paine or George Templeton Strong – allows for the more nuanced analysis of US musical life and the cultural elements that aggregated to fuel its growth. In a world of increasing globalization and in a musical field of evolving perspectives, the exploration of a musical microcosm offers an approach to observing the meaningful dimensions at play in the intersections of society, culture, politics and aesthetics moving through different artistic media and telling different stories about accrued cultural thought.

Appendix 1: Transcription of Edward MacDowell’s draft letter to Henry Irving

Figure Appendix 1a. MacDowell’s draft letter to Henry Irving, page 1. Library of Congress, EMMC, Box 32, Letter book.

Figure Appendix 1b. MacDowell’s draft letter to Henry Irving, page 2. Library of Congress, EMMC, Box 32, Letter book.

14.11.84 Mr. Charles Ferriss(?)

c/o Box Off: Lyceum Theater

14.11.84 Mr. Henry Irving

Star Theater (Broadw – + 13th St)

New York

Dear Mr. Irving,

I come to you with a favor hoping most heartily that you will grant it. Having seen Miss Terry and yourself a number of times in London at the Lyceum in Shaksperian plays I was so much impressed, I tried on my return to Germany to compose a number of some pieces using those Shaksperian characters you have acted, as subjects. Now as the compositions were first thought of after having seen Miss Terry and yourself I would be very much pleased if you would allow me to dedicate them to you, and with Miss Terry’s permission to her also. In asking this I of course run the risk of your not knowing my name and as I know in order to grant my request you would certainly wish to form some idea of my position as composer, I enclose from May, a criticism of my op. two pianoforte Suites, op. 10–14. I simply send this that you may see that my music is certainly of an earnest character. The pieces are called

Character-Skizzen

(Character-Sketches)

Von

E.A. MacDowell

Op. 22–23

The dedication would simply be

(for op. 22.) Henry Irving

Verehrungsvoll gewidmet.

(for op. 23) Ellen Terry

Verehrungsvoll gewidmet

(respectfully dedicated)

If you wished any change in the dedication I would will be only too happy to make it. As the pieces are coming out in the early Winter, I would be more than obliged if I could you would give me an answer as soon as you conveniently could. Hoping you will grant my request and that you will pardon me for troubling you. I remain yours faithfully, E.A. M____

Rebecca Schreiber is a musicologist based in Cincinnati, Ohio. She received her PhD from the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music (CCM) in 2023. Her research focuses include American music, programme music, nineteenth-century music, and music and gender. Rebecca has presented at several conferences in the US, including the national meetings of the American Musicological Society and the Society for American Music. Her work has been published in the Journal of the Society for American Music (spring 2022) and Oxford Bibliographies in Music. Rebecca has taught courses at CCM and Xavier University, and she also contributes programme notes to the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, creates digital content for the University of Cincinnati Press, and assists with special collections at the CCM music library.