1 Introduction

It is rare to witness the birth of a new technology, a new tool for entrepreneurship, a new investable asset class, and a new way of controlling financial decisions. Yet financial technologies (FinTech) represent all four, and so, unsurprisingly, their applications and the advancements that underlie them, like AI and blockchain, have sparked much fascination.Footnote 1 While these technologies advance rapidly, existing statutes and regulatory frameworks have not kept pace. The resulting regulatory uncertainty, exacerbated by coordination failures across agencies and jurisdictions in the United States (U.S.), risks stifling innovation and limiting benefits for consumers and small businesses. Although regulation must adapt, substantial uncertainty remains about what market failures and economic distortions may arise and what regulatory tools will mitigate them effectively.

In this study, I examine FinTech regulation through an economic and institutional lens. To analyze how regulation can effectively evolve requires understanding the economic forces driving FinTech development. I use a temporal structure (past, present, and future) to contextualize FinTech’s evolution and highlight emerging regulatory trade-offs. This temporal approach is valuable for seeing the dynamics and parallels between these transformative technologies, and the synergies between their emergent combination (AI × crypto). Without comprehensively understanding the institutional and economic purposes across technologies, such as platform-building in initial coin offerings (ICOs), extending existing regulations often leads to simplistic solutions like banning ICOs because the costs associated with fraud prevention are deemed excessive. Furthermore, this high-level, temporal approach permits novel insights into what regulatory solutions can reduce economic distortions across the financial system and enable long-term stability.

I begin by characterizing the rise of FinTech and comparing and contrasting it with historical examples. Traditionally, financial innovation delivers core financial functions, such as transferring value, managing risk, and mobilizing savings, more efficiently or inclusively. However, the current wave of innovation differs from historical ones. First, the locus of innovation has shifted from incumbent financial institutions marginally improving a single product or service to technology-focused entities redesigning financial infrastructure. By creating entirely new financial infrastructures, developers combine multiple types of innovation in the sense of Schumpeter (Reference Schumpeter1934) that encompass new products, processes, markets, and supply, even creating new opportunities for core financial capabilities or at least blurring previous boundaries. Finally, much of this innovation is open-source and composable, unlocking tremendous entrepreneurial activity that was traditionally impossible in financial services without being a bank.

Empirical evidence from a comprehensive dataset on FinTech startups and their fundraising activity between 2012 and 2024 shows that while conventional FinTech initially dominated funding and entry, AI and crypto ventures have gained significant momentum, with the AI × Crypto domain growing especially rapidly recently. Geographic analysis shows that the U.S. and China display dense footprints across nearly all FinTech domains, with the U.S. exhibiting an exceptionally high concentration of AI × Crypto startups, suggesting an advanced position in integrating these technologies and underscoring the urgency for regulatory clarity that properly considers the parallels across FinTech domains.

Next, I examine the specific catalysts for the current wave of financial innovation, including institutional ones like the great financial crisis and technological ones like meaningful cost reductions brought about by digitization (Goldfarb and Tucker, Reference Goldfarb and Tucker2019). Then, I show parallels in the economics underlying four distinct yet interrelated domains of FinTech innovation, including conventional FinTech applications (e.g., peer-to-peer lending and crowdfunding), AI-powered financial services (e.g., robo-advising and asset management), blockchain-based solutions (e.g., decentralized finance (DeFi), decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), non-fungible tokens (NFTs), and other Web3 applications), and finally, emergent AI × crypto services.

From an economic perspective, AI decreases the cost of prediction and exploration (Agrawal et al., Reference Agrawal, Gans and Goldfarb2018). AI has many use cases in finance, including robo-advisors, equity research, risk assessment, and credit scoring (D’Acunto et al., Reference D’Acunto, Prabhala and Rossi2019; Berg et al., Reference Berg, Burg, Gombovic and Puri2020; Cao et al., Reference Cao, Jiang, Yang and Zhang2020; Grennan and Michaely, Reference Grennan and Michaely2021). More recently, portfolio management, asset pricing, and even corporate finance are also areas that have benefited from the latest AI advances, such as transformer methods, reinforcement learning, and large language models (LLMs). For instance, “AlphaPortfolio” developed by Cong et al. (Reference Cong, Tang, Wang and Zhang2021) and tree-based asset pricing methods pioneered by Cong et al. (Reference Cong, Feng, He and He2023a) are some examples of applications going beyond off-the-shelf to tap into the power of AI. A point of tension with AI development is that algorithms can be biased or built upon data that violates privacy concerns (Bartlett et al., Reference Bartlett, Morse, Stanton and Wallce2022; Cong and Mayer, Reference Cong and Mayer2022). A layered regulatory approach is emerging to ensure AI systems are trustworthy and provide at least some baseline protections. For example, federal frameworks often incorporate voluntary industry standards, states reference federal guidelines when crafting local laws that may exceed federal requirements, and companies design practices to comply with and anticipate future regulations. However, more forward-looking, adaptive frameworks will be necessary as AI evolves.

Smart contracts, which are software programs potentially with AI capabilities stored on a blockchain that can receive external data in real-time and execute when certain conditions are met, enable a new category of financial service entrants called decentralized finance (DeFi) (Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Ramachandran and Santoro2021; John et al., Reference John, O’Hara and Saleh2022). From an economic perspective, DeFi is automation that reduces market power by democratizing access to financial services, while enhancing commitment mechanisms through transparent and secure transaction records. These benefits can reduce the cost of building and/or coordinating complex financial and managerial services. Yet in reality, the distributed DeFi structures might be costly to maintain and even more challenging to coordinate. Thus, consistent with other FinTech innovations, DeFi simultaneously reduces existing economic inefficiencies while introducing new ones. Therefore, it is essential to consider these novel costs when evaluating the efficiencies gained from circumventing traditional financial intermediaries and their associated fees, inefficiencies, and potential for rent-seeking behavior.

While capital began to be meaningfully raised for AI × crypto projects around 2020, primarily in data and compute, the generative AI boom of 2022 accelerated crypto developers’ interest in integrating these two technologies. Projects typically fall into four subcategories: compute, data, models, and applications. Compute projects create marketplaces leveraging idle GPU resources, offering flexible, lower-cost solutions than centralized alternatives. Data-focused ventures use blockchain-enabled marketplaces to monetize and exchange high-quality data efficiently. Model-oriented projects incentivize decentralized contributions of specialized AI models, while application-focused platforms combine frontier AI with blockchain to disseminate AI agents on blockchains. For example, some agentic applications act as decentralized autonomous entrepreneurs (DAEs) such as the Gaka-chu (Ferrer et al., Reference Ferrer, Berman, Kapitonov, Manaenko, Chernyaev and Tarasov2023), thus creating a seemingly new core financial capability catalyzed by synergies at the intersection of AI and crypto.

Legal frameworks hardly exist for AI × crypto applications, especially those with a capacity for autonomous financial transactions. Therefore, I evaluate different legal analogies for their recognition, including corporate personhood, animal rights, and product liability. Corporate personhood might provide a locus of responsibility, treating AI systems similarly to corporations with defined rights and obligations. Alternatively, an analogy to animal rights could suggest basic protections against exploitation, while product liability frameworks could hold developers accountable for harmful outcomes resulting from defective AI products. Each analogy has strengths and limitations, leading me to conclude that future frameworks may need to evolve toward hybrid models that integrate aspects of these various legal analogies to maintain existing societal rights and duties.

The insights from AI × crypto integration suggest that FinTech innovations, despite their benefits, can create or exacerbate familiar economic distortions such as agency conflicts, information asymmetries, moral hazard, and coordination failures. Therefore, my analyses highlight instances where standard regulatory tools like the price mechanism and entry/exit solutions can mitigate such distortions. For example, stablecoin reserve requirements mitigate distorted economic incentives through a price mechanism, or licensing requirements can be used to screen out low-quality service providers.

At the same time, there are legal areas where applications of existing precedent are more contentious. In such instances, regulatory frameworks must adapt to these challenges. For example, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) applied logic from a prior case in what has become known as the “Howey Test” to clarify when a token transitions from a “security” to a “utility token.”Footnote 2 The determining factors are the expectation of profit and the extent of decentralization. Unsurprisingly, developers of DeFi applications make subtle design choices so that an expectation of profit is not present. These design choices enable developers to fail the Howey Test and thereby avoid the burden of compliance with securities regulation. Or as an AI example, in 1939, Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter coined the phrase “fruit of the poisonous tree” in developing doctrine governing the admissibility of evidence in court (Frankfurter, Reference Frankfurter1939). As the metaphor suggests, if the “tree,” or a source of evidence, is tainted, so is its “fruit.” A parallel concept for the importance of data integrity in AI-driven financial products has recently been applied, suggesting that illegitimately acquired data may taint the entire AI-based model or application.

Another frequently disputed topic is secondary liability, which could create issues for DeFi aggregators, liquidity providers, and even DAO community members if the DAO facilitates unlawful behavior. While safe harbors may provide a solution for well-intentioned DeFi creators, it is worth noting that perpetual safe harbors, such as those associated with Section 230 for platform companies, appear to have long outlived their use (Citron and Wittes, Reference Citron and Wittes2017; Smith and Alstyne, Reference Smith and Alstyne2021). Notably, at their discretion, most platform companies adjudicate disputes (e.g., over copyright infringement, appropriateness of content, and/or counterfeit products). Despite several attempts, no private solution for a blockchain-based adjudication system has gained much traction. From a forward-looking perspective, RegTech-enabled adjudication could be a promising area for regulators to step in.

Next, I explore modifying existing regulatory tools, such as offering safe harbors with sunset provisions, and new regulatory applications such as RegTech, a term encompassing FinTech innovations that enhance the regulatory process. For example, many traditional market manipulation tactics, including wash trading and pump-and-dump schemes, port to digital asset markets. These practices undermine market integrity, inflate project valuations misleadingly, and harm investor trust. Regulators have intensified efforts to curb such manipulative practices through enforcement actions. Enhanced surveillance and transparency (e.g., RegTech-embedded monitoring and even automated enforcement) could deter market manipulation further. RegTech can also help with the complexities of finding solutions for jurisdictional issues, such as taxation, and compliance issues (e.g., portable Know Your Customer (KYC)). This is critical as many cybercrimes have been enabled by DeFi capabilities (Cong et al., Reference Cong, Harvey, Rabetti and Wu2023c), yet we also know that blockchain transparency and forensics can help regulators to detect and prosecute criminals (Cong et al., Reference Cong, Grauer, Rabetti and Updegrave2023b).

While adapted regulatory tools and RegTech solutions are promising, the sheer magnitude of new risks emerging from rebuilding the infrastructure for financial services means regulators will need a multifaceted approach. Thus, encouraging aspects of self-regulation with governmental oversight, such as adopting standardized approaches and metrics for decentralization, would be beneficial as would be collaborative governance arrangements, such as regulatory sandboxes, where stakeholders, including developers, incumbents, academics, and consumer advocates, must overcome adversarial positions and engage with regulators to create balanced policies. Importantly, though, in doing so, the collaborators must credibly commit to not tilting the rules in favor of a single participant in the sandbox.

The remainder of the Element is structured as follows: Section 2 establishes the historical context of financial innovation, defines core financial functions, and presents data documenting the rise of FinTech startups. Section 3 examines the economic incentives shaping innovation and market entry across specific FinTech domains and common distortionary forces. Section 4 reviews existing regulatory approaches, and Section 5 proposes actionable regulatory solutions before concluding.

2 The Rise of FinTech (Past)

2.1 Defining FinTech through Core Financial Functions

FinTech has become a catch-all term for innovations that leverage digital tools to deliver financial services more efficiently, inclusively, and transparently. In a seminal paper, Philippon (Reference Philippon2016) defines FinTech as covering

digital innovations and technology-enabled business model innovations in the financial sector. Such innovations can disrupt existing industry structures and blur industry boundaries, facilitate strategic disintermediation, revolutionize how existing firms create and deliver products and services, provide new gateways for entrepreneurship, democratize access to financial services, but also create significant privacy, regulatory, and law enforcement challenges. Examples of innovations that are central to FinTech today include cryptocurrencies and blockchain, new digital advisory and trading systems, artificial intelligence and machine learning, peer-to-peer lending, equity crowdfunding and mobile payment systems.

While this definition is prescient and informative, to understand the institutional context in which FinTech emerged, one must lay the groundwork by answering foundational questions from the past. First, what core functions does the financial system provide, and why are these functions central to economic activity? Second, what allocative or productive inefficiencies justify governments and regulators intervening in the supply and demand dynamics of financial services?

Economic theory identifies six core capabilities supplied by well-functioning financial systems, for example, see detailed explanations in Freixas and Rochet (Reference Freixas and Rochet2008). First, financial markets enable the clearing and settling of payments to facilitate commerce. From ancient barter systems to modern online payments, finance ensures that buyers and sellers can transact with confidence, minimizing counterparty risk (i.e., the probability that one party in a financial transaction will default on their contractual obligation, resulting in a loss for the other party) and transaction costs (i.e., all expenses incurred in the process of exchange beyond the price of the good or service itself such as search costs, bargaining costs, and enforcement costs associated with contract fulfillment).

Second, financial markets provide mechanisms for pooling funds to undertake large-scale projects. This pooling function makes it possible to assemble capital from diverse sources, ranging from individual savers to corporate treasuries to institutional investors. This pooled capital can then be channeled into ventures too large or complex for any single entity. Moreover, by subdividing ownership (i.e., through securitization processes such as those associated with issuing equity), financiers allow investors to diversify across multiple businesses, thus managing their exposure to risk from any single default or loss.

A third function of the financial system, particularly that of intermediaries, is transforming assets to facilitate better resource transfer across time or maturity, region or denomination, and industries. Finance allows households to save today for future consumption (e.g., via retirement savings), permits firms to invest capital in high-return projects (e.g., via corporate venture capital), and facilitates reallocating tangible and intangible assets when economic conditions shift. This intermediation balances the liquidity needs of firms and households while fostering a more dynamic economy. A fundamental feature of this resource transfer and reallocation is that the underlying assets have been transformed to better meet the demands of various actors.

Fourth, and related to the transformation of assets, is the transformation of risk-return profiles and the ability to manage risk. Financial instruments and markets offer many ways to manage risk. Through insurance contracts, derivatives, or loan syndication, parties can price, hedge, and distribute different types of risk. This bundling and decomposition of risk-and-return profiles helps financial and nonfinancial actors remain resilient to changing circumstances.

Fifth, financial markets contribute to price formation and informativeness. Stock prices, interest rates, and other market signals aggregate vast amounts of decentralized information about underlying economic prospects. When these prices reflect fundamental values, capital flows to its most productive uses. However, where informational frictions persist, the market may misprice assets, leading to instability.

Sixth, financial systems provide ways to mitigate incentive alignment problems when there is information asymmetry or agency costs. For example, banks have always had a role to play in managing the imperfect information provided by borrowers, such as the meaningful effort exerted by loan officers to gather soft details. Beyond asymmetric information, principal-agent relationships permeate finance, from shareholders delegating to empire-building managers to retail investors needing advice from honest, unconflicted financial advisors. Through novel contract and security design features, financial service providers help to align incentives.

The financial system provides a foundation for economic activity by fulfilling these six functions. Historically, banks have primarily been responsible for delivering these six functions. Banks were in this privileged position because their business model of taking in deposits and making loans enabled them to provide unique services like payments to the general public that were not as feasible for other business models without the advent of digital tools.

Summarizing these core capabilities enables a broad perspective of FinTech innovation. Namely, any innovation meant to improve or build upon these core financial functions is part of the “FinTech” landscape. From an innovation perspective, Schumpeter (Reference Schumpeter1934) distinguished between five types of innovations, which include (i) new products, (ii) new methods of production, (iii) new sources of supply, (iv) exploitation of new markets, and (v) new business models. What is striking about FinTech startups is that they often combine more than one type of innovation, especially outside of the conventional FinTech realm. For example, blockchain provides a new method of production, which, when combined with smart contracts, enables new business models that arguably have a competitive advantage because they can offer new, customized products or include those traditionally excluded from financial markets.

The transformative potential of FinTech, therefore, should not solely be judged by a single technical merit (e.g., better credit prediction from AI) but rather by its combined capacity to enhance the six core functions of any financial system. It is also true that this powerful interconnectedness among the innovations means that new core capabilities are emerging as part of the system. Given these developments, in the subsequent subsections, I will describe the core technologies underlying FinTech (i.e., AI, blockchain, smart contracts, digital assets, etc.) and their emergent combination (AI × crypto).

This functional perspective also helps explain why a future with potentially novel regulatory solutions may be the appropriate response in the FinTech era. Another unique facet in this era of FinTech innovation is that the innovations have not been limited to new entrants trying to work within the system. Instead, the entrants are trying to build a whole new financial infrastructure, typically on blockchains, rather than improving access to or making the existing traditional system more efficient. By creating a whole new infrastructure, especially one that is open-source and allows anyone to build upon it, the barriers to entry in financial services, such as high fixed costs from compliance, have been dramatically lowered. This, in turn, encourages even more entry and competition, ushering in meaningful change to the financial system. This innovation is typically associated with efficiency gains, yet novel and unpredictable risks, potentially necessitating a new definition of systemic risk (Adrian and Brunnermeier, Reference Adrian and Brunnermeier2016).

Before I introduce the specific technologies underlying this era of FinTech and data on their prevalence, I want to put their development in historical context, making it easier to see where traditional regulatory solutions for innovation are likely to face challenges.

2.2 Financial Innovation in Historical Context

It is well established that young, high-growth entrepreneurial firms are essential for innovation and economic growth. Indeed, innovation often serves as a competitive advantage for new entrants to gain market share and generate profits in established industries. In addition, regulatory barriers are known to prevent entry or distort prices in such a way as to inhibit entrepreneurship. Historically, the banking industry and the financial system generally have not had as many entrepreneurial entrants as other industrial sectors. Thus, it’s essential to understand how financial innovations come about and how much this current wave of innovations differs from prior ones.

Focusing on parallels and divergences in the pattern of financial innovation reveals that in past eras, a single type of innovation in the Schumpeter sense often emerged from incumbents to achieve efficiency gains in core financial capabilities, which contrasts starkly with this era of FinTech innovation. Yet both this era and previous eras of financial innovation seem catalyzed by either cost reductions associated with technological progress or in response to institutional change. Typically, a given technological advance in business methods reduced costs and drove efficiency gains in financial services, and these more efficient practices spread throughout the industry, influencing the overall efficiency. Shifts in the regulatory landscapes only occurred after increased adoption (Tufano, Reference Tufano2003; Lerner and Tufano, Reference Lerner and Tufano2012). In these cases, financial innovation emerged as a solution to frictions common in financial services, such as high levels of asymmetric information, transaction costs, or tax constraints.

As an example, consider how early financial innovation enabled faster transactions. There is no new product, but rather, there is a new method to produce it. The automated teller machine (ATM) exemplifies this type of early financial innovation, as it significantly transformed retail banking by automating transaction processing and providing convenience to customers. While ATMs reduced transaction costs and improved service accessibility, they reinforced banks’ roles rather than displacing them. Next, consider new products, such as a unique way to structure a security (e.g., tax-advantaged municipal bonds) or introducing credit cards. Again, like with ATMs, these products improved service accessibility. In these instances, no new core financial service was offered, and the underlying infrastructure (e.g., banks and intermediaries) remained the same.

Also, typically, these innovations were not the type of invention for which banks would seek IP protection. Thus, while credit cards transformed payment methods, they did not significantly alter the financial infrastructure. Notably, Bank of America issued the first credit card, but there was a belief that early credit cards may not have been considered novel enough for patent protection. Moreover, given the high cost of entry in the financial services industry, most financial institutions relied on other competitive advantages like their existing customer relationships, brand recognition, and distribution networks to fend off competitors. In fact, it was only after the 1998 State Street Bank decision that the financial services industry started to pursue IP protection regularly (Hall, Reference Hall2009).

From a historical perspective, the current wave of innovation is different for several reasons, but only a few reasons lead to regulatory differences. First, the locus of innovation has moved from banks being the innovators to technology-focused entities and FinTech startups being the innovators (Lerner et al., Reference Lerner, Seru, Short and Sun2024). This transformation marks a change whereby traditional banks have ceded innovative capabilities to tech-driven newcomers. Part of this may be that this cycle of financial innovation has focused less on business-centric applications and the business method improvements incumbents typically pursued and more on consumer-centric ones, where the user design experience is paramount.

To understand why this distinction alone does not necessitate regulatory differences, consider neobanks. These digital-only startups embody a single type of innovation, that of business model innovation. Neobanks essentially provide a more user-friendly interface to traditional banking services while still operating within the established financial system. Neobanks often use a bank-partnership model. The partner bank holds the deposits and issues the debit cards, while the neobank provides the customer-facing app, technology infrastructure, and customer service. Unlike traditional banks that rely on interest income, neobanks generate revenue through subscription fees for premium services, referral fees for third-party financial products, and fee income from specific services like expedited transfers. In this sense, it is clear that the regulatory scrutiny should focus on where bad actors are likely to engage, such as deceptive marketing practices and the exploitation of behavioral biases. These are all areas where regulators have experience, and the approach parallels easily. Yet most FinTech innovations now encompass multiple innovations in the Schumpeter sense.

Another reason this wave of innovation is different is that information itself has become the central commodity being transacted, not merely a facilitator of a financial exchange. The tension between more efficient information-gathering capabilities and strategic selection of information sets represents an economic trade-off that prior regulatory frameworks have not adequately addressed. When firms can selectively harvest consumer data at near-zero marginal cost, the resulting information asymmetry creates not merely a private advantage but a potential market failure. Similarly, when blockchain-based smart contracts need information external to the smart contract to execute the agreement (e.g., current exchange prices, which oracles can provide), understanding new risks associated with accessing that information (i.e., biased or manipulated representation) is critical. As is explored in Section 3.8, this information issue is central to the emerging FinTech technologies, including AI and blockchain.

Yet another feature that makes this wave of innovation so different is that the innovators are trying to create an entirely new financial infrastructure rather than simply improving access to or reducing friction in the existing system. In this sense, the current wave of financial innovation, which, at times, is trying to replace traditional intermediaries with automated protocols or smart contracts does not have natural regulatory parallels as the markets may provide similar core capabilities, but the infrastructure used to generate the capability doesn’t necessarily have the same centralized bottlenecks like a small number of brokers that current regulatory can focus on.

Perhaps, more importantly, and uniquely, this achievement of creating a new infrastructure has been done in a much more open-source way than any past innovation. This is making it a lot easier for anyone to build something new. This also enables customization and composability of financial primitives at an unprecedented scale. When such primitives interconnect in a Lego-like fashion, it allows for new core capabilities to be offered by the financial system (e.g., see my discussion of DAEs and entrepreneurship as a novel service in Section 3.7). By lowering the barriers to entry and innovation, the new financial system will likely be more efficient along some dimensions (e.g., less concentrated, so less rent extraction), yet, at the same time, the ease of entry will attract bad actors and speculators.

Along with technological innovation, institutional forces serve as powerful catalysts for financial innovation by establishing frameworks that shape market behavior and economic activity. An example of institution-driven financial innovation is the development of index funds in the 1970s. They emerged as a direct response to institutional constraints in the investment management industry. Before their creation, the prevailing institutional structure favored active management despite mounting evidence that most active managers failed to outperform market indices after fees. Thus, there was pent-up demand for a cost-effective investment vehicle. Recognizing this inefficiency, Vanguard’s founder created the first publicly traded index fund.

This example, however, reinforces the ideas we saw when technological progress rather than institutional changes catalyzed innovation. Early periods of FinTech innovation were characterized by a single type of innovation (typically product or process innovation). They occurred in response to persistent inefficiencies or failure to serve market participants optimally. However, they never created a new financial system, nor did they combine multiple types of innovation in Schumpeter’s sense.

In contrast, recent FinTech innovations introduce novel institutional arrangements and reshape how trust, governance, and control are managed in financial transactions. Unlike previous institutional structures, blockchain technology can reduce reliance on traditional intermediaries. Yet, these decentralized structures pose new regulatory challenges, from definitional questions such as what defines custody to deeper concerns related to accountability, risk management, and financial stability.

Combining AI with blockchain further compounds these complexities by increasing the potential for economic distortions. AI-driven predictive technologies can amplify systemic risks, create market manipulation vulnerabilities, and exacerbate informational asymmetries in these new financial markets. These distortions present challenges distinct from historical precedents, necessitating entirely new regulatory approaches.

Thus, while previous literature has acknowledged the complexity introduced by financial innovation, including its potential for substantial externalities, it does not speak to the specific distortions introduced when integrating multiple types of innovation in the Schumpeterian sense and which AI × crypto applications exemplify. As I argue in this Element, AI and blockchain are integrating, and therefore, it is helpful to view the regulation from an integrated approach. When combined, the economic distortions these technologies create can differ from individual ones, although we can learn from the individual ones. In this sense, the sum of the parts equals more than the parts individually because of these synergies, and new solutions are required to address the unique risks associated with this powerful combination.

2.3 Domains of FinTech Innovation

Below is a high-level overview of the major areas of FinTech that will form the backdrop for this Element and the dataset described below. The classification reflects common market segments and the interplay of emerging technologies with traditional financial services (TradFi).

First, there is conventional FinTech, which focuses on enhancing existing services rather than reinventing them from scratch. For example, peer-to-peer (P2P) lending platforms connect individual borrowers and lenders directly, reducing overhead costs and streamlining loan approvals. Similarly, Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) solutions aim to disrupt traditional consumer credit markets by offering short-term installment financing, often at the point of sale. Each of these developments addresses long-standing friction in cost and speed within mainstream finance and is the most similar to the ATM or credit card examples from history. Conventional FinTech shares the most parallels with earlier financial innovations (e.g., ATMs, credit cards) in that they tend to be process or product-oriented and are not recreating new infrastructure outside the traditional financial system, nor are they creating a new financial function.

A second category focuses on applying AI to core financial functions through automation, personalization, and predictive capabilities. AI-powered robo-advisors now provide personalized investment recommendations at a fraction of traditional management fees, democratizing wealth management services. In lending, AI can analyze real-time, big data beyond traditional credit scores to assess risk more accurately, expanding access to credit for underserved populations. Fraud detection systems leverage AI to identify suspicious patterns in real-time, dramatically reducing financial crimes while minimizing false positives that previously created friction for legitimate customers. Meanwhile, LLMs have transformed customer service through intelligent chatbots that handle routine inquiries instantly, allowing human agents to focus on more complex tasks. While AI promises efficiency gains and improved accuracy, it also raises concerns about transparency, data privacy, and potential biases embedded in its models.

A third category focuses on the blockchain and Web3 technologies that underpin cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum, but their use cases extend beyond digital currency. By providing a decentralized, tamper-resistant ledger, blockchain can expedite settlement times, reduce transaction fees, and enable automated smart contracts, which are self-executing code that enforces contract terms without central intermediaries. Digital assets have blossomed beyond simple payment tokens to encompass stablecoins and many other types, each with potentially distinct regulatory considerations (Cong and Xiao, Reference Cong, Xiao, Pompella and Matousek2021).

DeFi furthers blockchain’s potential, constructing financial products like lending, trading, and insurance on open protocols without traditional intermediaries. In DeFi, governance may lie with DAOs, whose rules and operations are encoded in software and collectively decided upon by token holders (Appel and Grennan, Reference Appel and Grennan2023). Finally, Web3 components like NFTs introduce digital scarcity into art, collectibles, and real estate. Their unique identifiers mean each token can represent a distinct piece of digital (or physical) property. Soul-bound tokens (SBTs) build on the scarcity introduced with NFTs by serving as identity-bound, nontransferable assets, which are valuable for credentialing or reputation systems.

Finally, an emerging frontier is the fusion of AI with blockchain technologies, which has colloquially been called “AI × Crypto.” Early ventures in this domain apply cryptoeconomic frameworks to accelerate AI development. Although major centralized AI providers have dominated the field through economies of scale, new projects are developing decentralized alternatives by experimenting with novel model architectures and incentive platforms. Broadly, four areas define this space: (1) decentralized compute networks offering pooled GPU resources for training and inference as highlighted by Cong et al. (Reference Cong, Tang, Wang and Zhao2023g); (2) coordination platforms incentivizing AI model development or enabling specialized inference approaches; (3) DAEs, which are AI agents and related tools and applications that can closely replicate traditional workflows and engage in entrepreneurial endeavors; and (4) decentralized general intelligence (DGI) which aims to produce an application layer similar to what has been put forth by OpenAI and Anthropic, namely, a productized AI solution for consumer or enterprise use.

2.4 Data on FinTech Innovation

To evaluate trends in FinTech innovation, I assembled data on FinTech startup entry from four major providers: Messari, Dove Metrics, Crunchbase, and Preqin – each of which has some advantages and caveats in terms of comprehensive FinTech data on funding, founding dates, and company-level details. For instance, Messari, which later acquired Dove Metrics, has the most comprehensive data on crypto startups, including unofficial announcements of funding via Twitter. Crunchbase and Preqin are more traditional sources of data for startups. Preqin has some of the most comprehensive fundraising data, but this gives it a bias toward firms that receive at least some VC funding, whereas Crunchbase typically has details even on young startups that may not have raised meaningful capital yet. By harmonizing across these sources, I aim to provide a more complete view of both traditional venture-funded startups (the standard route for conventional FinTechs), and those financed through more novel mechanisms, such as token-based financing. Online Appendix A details the initial aggregation.

To classify the startup’s business description into one of the FinTech domains, I employ a multistep classification procedure. The four categories or domains include traditional FinTechs, AI, Blockchain, and AI × Crypto. This process began with targeted keyword searches (e.g., blockchain, artificial intelligence, stablecoin, etc.) and was subsequently refined using large-language-model (LLM) filters tailored to identify nuanced business model references. Finally, I conduct manual checks for borderline or ambiguous cases, resulting in the final dataset. This multi-step approach balances scalability and rigor, enabling a detailed analysis of domain-level patterns while maintaining a high degree of classification accuracy. For the exact keywords and prompts used to classify, please see Online Appendix A.

2.5 Summary Statistics

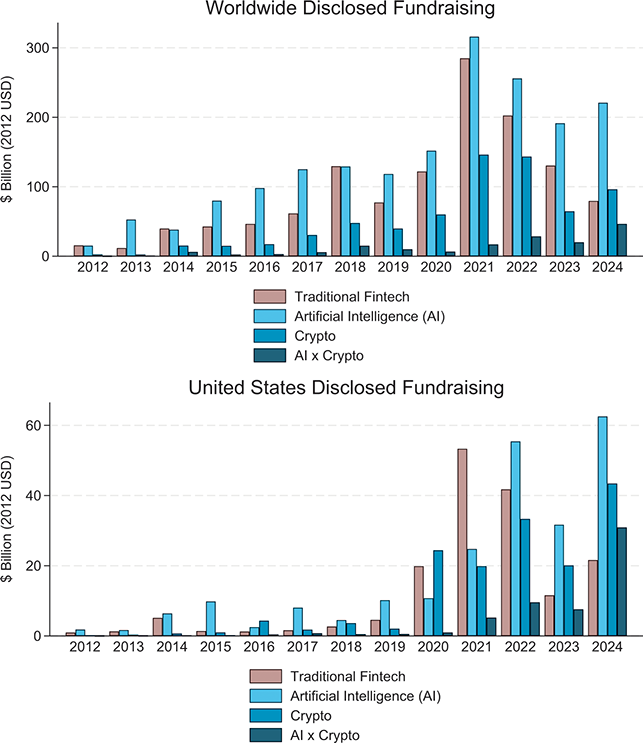

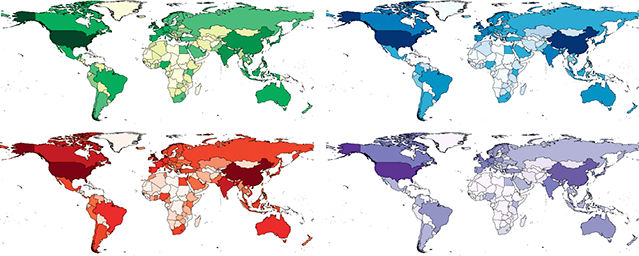

Figure 1 provides a high-level view of how total disclosed FinTech fundraising has evolved worldwide and in the U.S. from 2012 through 2024. Globally, the total amount of capital raised that has been publicly disclosed has grown markedly over this period across all four subcategories of FinTech innovation: traditional FinTech, AI, crypto, and combined AI × crypto. Yet the relative contribution of each category diverges over time. In the early 2010s, funding was dominated by more conventional FinTech business models focused on payments, peer-to-peer lending, and robo-advising, while AI- and crypto-focused ventures initially raised only modest amounts. By the late 2010s and into the early 2020s, however, AI and crypto reached parity or surpassed traditional FinTech startups in terms of total funding, signaling an inflection point in investor preferences. Although starting from a small base, the AI × crypto segment displays especially rapid growth, reflecting demand for solutions that integrate these technologies. Notably, although U.S. fundraising volume is proportionally smaller than global totals, it echoes the same upward trajectory and category shifts, highlighting the prominent role of U.S.-based startups in shaping FinTech innovation despite meaningful regulatory uncertainty and related challenges.

Figure 1 Total disclosed FinTech fundraising (2012–2024). The figures depict the total disclosed FinTech fundraising globally and in the United States from 2012 through 2024. The business models of the funded startups are categorized into Traditional FinTech, AI, Crypto, and AI × Crypto.

Figure 1Long description

This figure contains two bar charts showing the total amount of disclosed fundraising by any FinTech startup from 2012 to 2024, measured in billions of 2012 U.S. dollars. The top chart displays worldwide fundraising with values ranging from less than $10 billion in 2012 to peaks above $300 billion in 2021. Four categories of startups are shown in different colors: Traditional Fintech (tan), AI (light blue), Crypto (medium blue), and AI × Crypto (dark blue). The data show lower levels of fundraising from 2012 to 2015, gradual growth from 2016 to 2019, dramatic increases from 2020 to 2021, with 2021 reaching the highest peak, followed by declining but still substantial levels from 2022 to 2024 (doubling levels from 2016 to 2019). The bottom chart shows U.S. fundraising with the same categories and time periods, but lower overall values ranging from near zero in 2012 to approximately $60 billion at the 2024 peak. The pattern is similar to the worldwide data from 2012 to 2019, but departs in 2020. The U.S. shows its highest fundraising levels in 2024 rather than 2021, particularly driven by increases in the AI and AI × Crypto categories. In contrast, Traditional FinTech is the second-largest category worldwide in 2023. Both bar charts use stacked bars where each segment represents the contribution of each funding category to the total disclosed fundraising for that year.

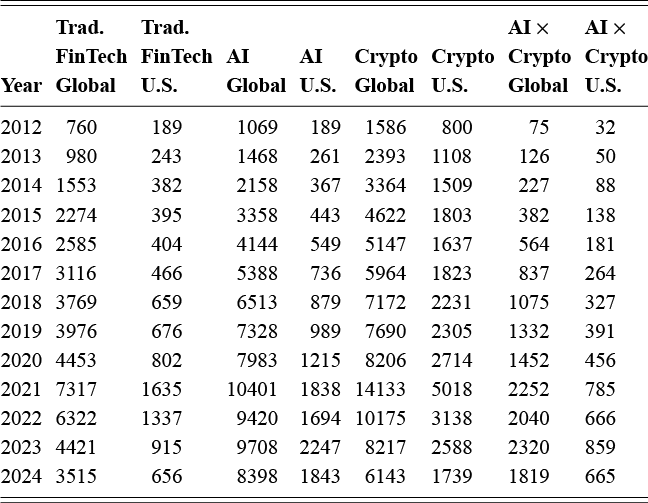

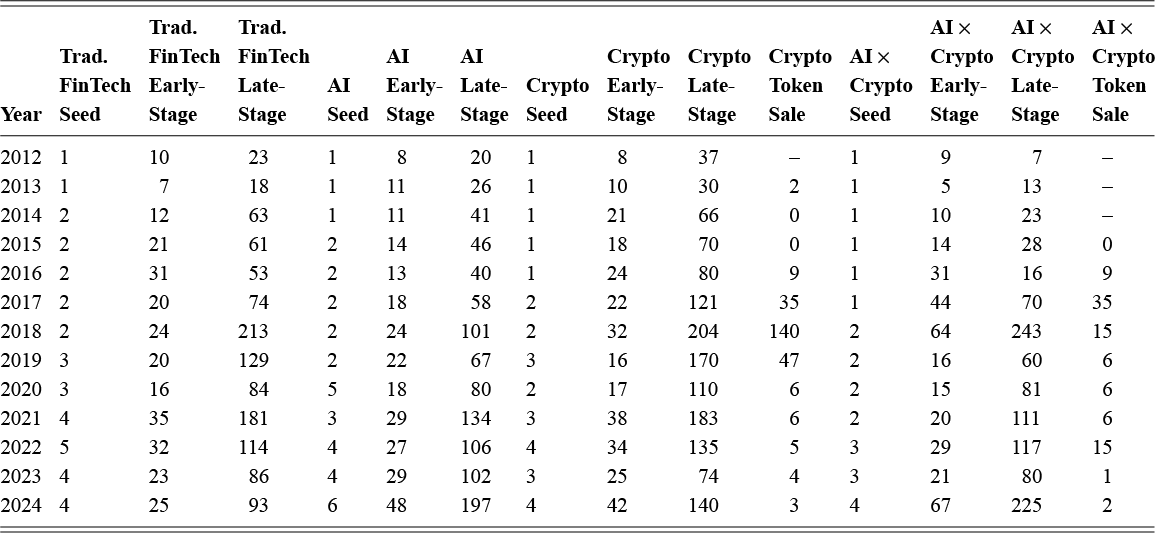

Turning from the aggregate funding trends documented in Figures 2 to the specific startup counts, Table 1 provides a breakdown of the number of unique startups funded each year in the U.S. and globally between 2012 and 2024. Again, the counts are disaggregated by the four subcategories of FinTech innovation. In addition, the columns are further broken out by global versus U.S. totals. The data reveals several trends. First, traditional FinTech and AI startups show the largest absolute increases over time, reflecting the continued maturation of these technologies worldwide. Second, crypto-focused ventures exhibit a marked rise from modest beginnings in the early 2010s to increasingly substantial numbers by the mid-2020s, coinciding with the broadening of crypto into DeFi and other applications. Importantly, from a regulatory perspective, the AI × crypto category, although starting from a relatively low base, displays a steep upward trajectory both within the U.S. and globally. This latter observation highlights the growing convergence of AI-driven and blockchain-based innovations in the FinTech sector. This trend, along with other parallels between the branches of FinTech, requires a more integrated regulatory framework rather than separate oversight. Finally, the U.S. numbers, in particular, indicate that policymakers must be prepared to handle the compound challenges posed by AI × crypto startups, given the rapidly expanding presence of these startups and their revealed preference for U.S. locations.

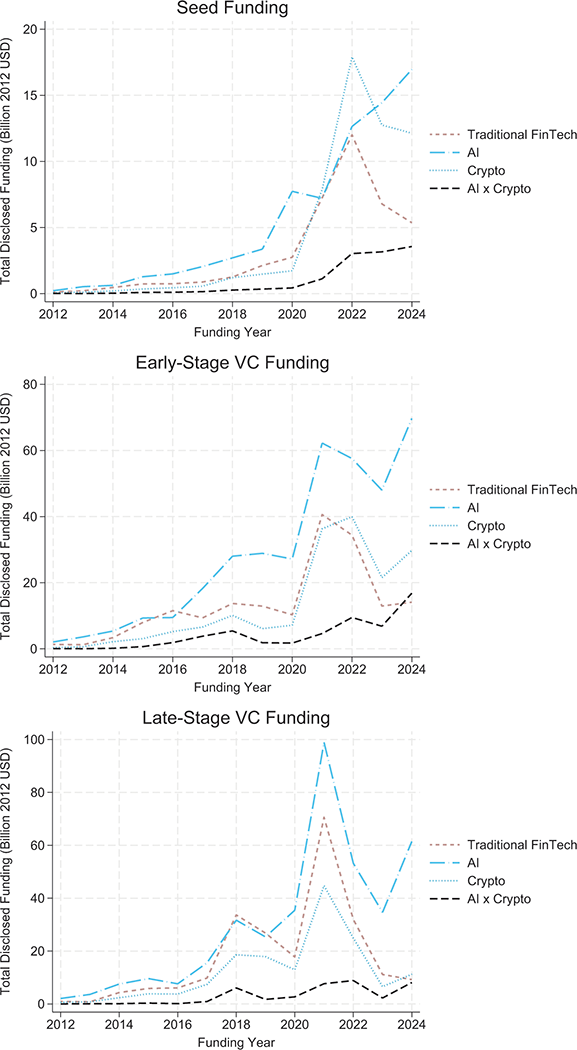

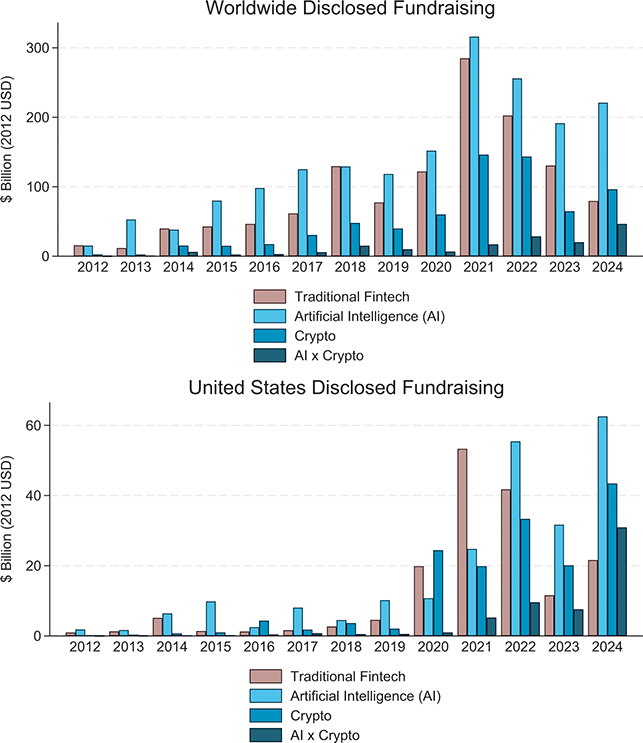

Figure 2 Total disclosed FinTech fundraising by stage (2012–2024). The figures depict the total disclosed FinTech fundraising by stage of startup (seed funding, early-stage, or late-stage funding) for the global sample from 2012 through 2024. The business models of the funded startups are categorized into Traditional FinTech, AI, Crypto, and AI × Crypto.

Figure 2Long description

This figure contains three line charts showing different stages of startup funding from 2012 to 2024, with the total amount of global fundraising measured in billions of 2012 U.S. dollars displayed on the y-axis and funding year on the x-axis. Each chart displays four categories of startups in different colors and patterns: Traditional Fintech (solid tan), AI (long-dash, light blue), Crypto (dotted, medium blue), and AI × Crypto (dashed dark blue). The top chart shows seed funding with values ranging from near 0 to $20 billion. All categories initially show lower levels of seed fundraising, followed by steady growth through 2019, and then sizable increases from 2020. Crypto funding shows the most dramatic increase, peaking at around 18 billion in 2022 before declining slightly. Traditional FinTech also peaks in 2022 at approximately $12 billion, while AI and AI × Crypto peak in 2024, reaching about $18 and $4 billion, respectively. The middle chart displays Early-Stage VC Funding with values from $0 to $80 billion. The pattern is similar but more pronounced, with AI showing explosive growth, reaching approximately $70 billion by 2024. The bottom chart shows Late-Stage VC Funding with values from $0 to $100 billion. This stage shows the most dramatic variations, with AI reaching nearly $100 billion in 2021. Traditional FinTech and Crypto both echo this volatile pattern, while AI × Crypto remains relatively modest, not exceeding $10 billion throughout the period. All three charts show a general pattern of low activity in early years, significant growth starting around 2016, peaks around 2021 to 2022, and varying degrees of decline or stabilization in the later years.

| Year | Trad. FinTech Global | Trad. FinTech U.S. | AI Global | AI U.S. | Crypto Global | Crypto U.S. | AI × Crypto Global | AI × Crypto U.S. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 760 | 189 | 1069 | 189 | 1586 | 800 | 75 | 32 |

| 2013 | 980 | 243 | 1468 | 261 | 2393 | 1108 | 126 | 50 |

| 2014 | 1553 | 382 | 2158 | 367 | 3364 | 1509 | 227 | 88 |

| 2015 | 2274 | 395 | 3358 | 443 | 4622 | 1803 | 382 | 138 |

| 2016 | 2585 | 404 | 4144 | 549 | 5147 | 1637 | 564 | 181 |

| 2017 | 3116 | 466 | 5388 | 736 | 5964 | 1823 | 837 | 264 |

| 2018 | 3769 | 659 | 6513 | 879 | 7172 | 2231 | 1075 | 327 |

| 2019 | 3976 | 676 | 7328 | 989 | 7690 | 2305 | 1332 | 391 |

| 2020 | 4453 | 802 | 7983 | 1215 | 8206 | 2714 | 1452 | 456 |

| 2021 | 7317 | 1635 | 10401 | 1838 | 14133 | 5018 | 2252 | 785 |

| 2022 | 6322 | 1337 | 9420 | 1694 | 10175 | 3138 | 2040 | 666 |

| 2023 | 4421 | 915 | 9708 | 2247 | 8217 | 2588 | 2320 | 859 |

| 2024 | 3515 | 656 | 8398 | 1843 | 6143 | 1739 | 1819 | 665 |

Note: This table shows the number of unique startups funded each year across four FinTech subfields: traditional FinTech, AI, Crypto, and AI × Crypto. Both global and U.S.-specific counts are provided.

Next, I explore a more granular view of how funding flows vary by startup maturity. Figures 2 and 3 break down publicly disclosed FinTech fundraising into seed, early-stage VC, and late-stage VC categories. These figures build upon the startup counts provided in Table 1 by clarifying not only how many ventures are funded in each subsector but also how heavily they are financed at different points in their life cycles, which helps assess the sector’s trajectory and the potential regulatory touchpoints.

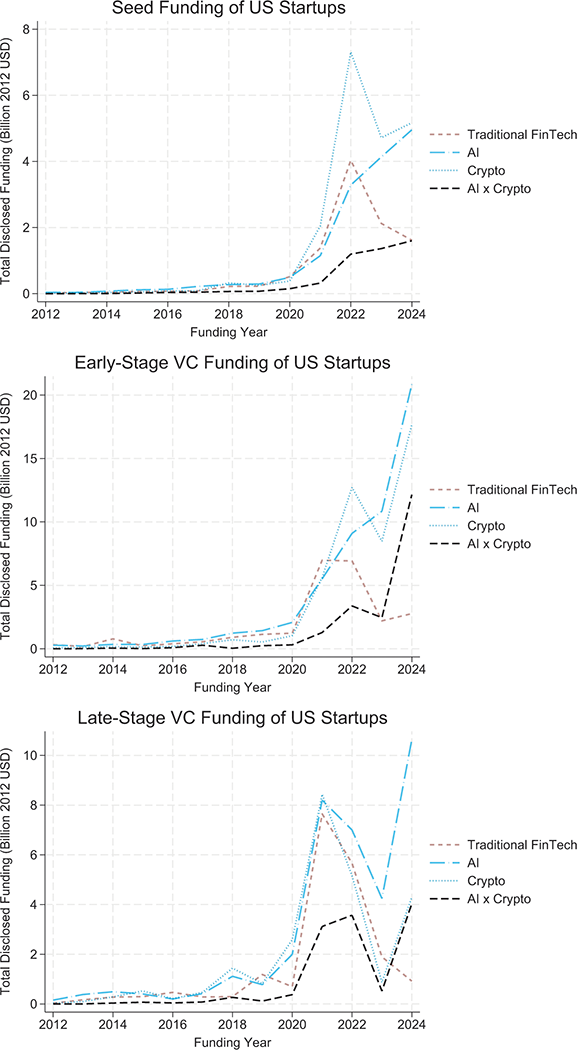

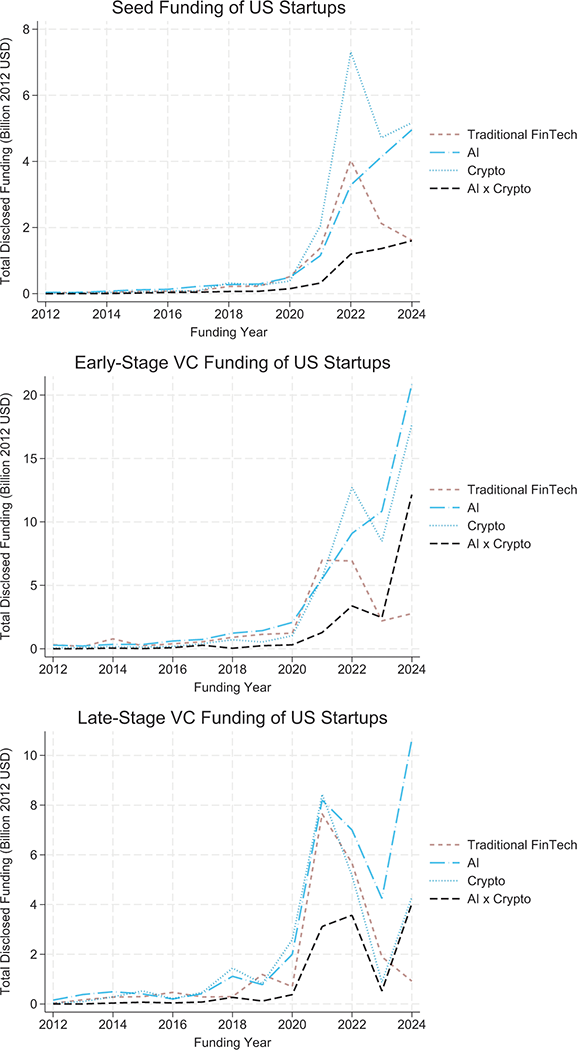

Figure 3 U.S. FinTech funding by stage of startup (2012–2024). The figures depict the total disclosed FinTech fundraising by stage of startup (seed funding, early-stage, or late-stage funding) for the U.S. sample from 2012 through 2024. The business models of the funded startups are categorized into Traditional FinTech, AI, Crypto, and AI × Crypto.

Figure 3Long description

This figure contains three line charts showing different stages of startup funding from 2012 to 2024, with the total amount of U.S. fundraising measured in billions of 2012 U.S. dollars displayed on the y-axis and funding year on the x-axis. Each chart displays four categories of startups in different colors and patterns: Traditional Fintech (solid tan), AI (long-dash, light blue), Crypto (dotted, medium blue), and AI × Crypto (dashed dark blue). The top chart shows seed funding with values ranging from near $0 to $8 billion. All categories initially show lower levels of seed fundraising, followed by steady growth through 2019, and then sizable increases beginning in 2020. Crypto and AI each received about $5 billion in seed capital in 2024, with AI continuing to surge and Crypto exhibiting more volatility, having previously peaked at around $7.5 billion in 2022 before declining to under $4.5 billion in 2023 to rebound in 2024. Traditional FinTech also peaks in 2022 at approximately $4 billion, but does not rebound and continues to decline to less than $2 billion in 2024. AI × Crypto peaks in 2024, reaching about $2 billion. The middle chart displays Early-Stage VC Funding with values from $0 to $20 billion. The pattern is similar but more pronounced, with AI, Crypto, and AI × crypto all showing explosive growth and reaching new heights in 2024 while Traditional FinTech declines. The bottom chart shows Late-Stage VC Funding with values from $0 to $10 billion. Like the previous charts, Traditional FinTech diverges while all others are heading toward new peaks, although late-stage crypto projects are not raising funds nearly as much as early-stage ones.

Figure 2 focuses on global trends and reveals that, although seed-stage funding for traditional FinTech dominated early in the sample, AI startups commanded an increasing share of early-stage and late-stage funding by the late 2010s. Crypto investments, while initially small, gained momentum in the early 2020s, with AI × Crypto showing growth during the seed and early-stage rounds after 2020. For example, in 2023–2024, AI × Crypto exhibits near-parity with traditional AI in certain stages, suggesting enthusiasm for combined AI × Crypto solutions.

Figure 3 shows an analogous breakdown for U.S. startups, tracing similar patterns but with some notable differences in the relative magnitudes across subsectors. Seed funding for U.S. AI ventures, for instance, accelerated significantly around 2021 and overtook Traditional FinTech by 2022. Crypto and AI × Crypto remains smaller in the seed stage than globally, but has surged more prominently in early- and late-stage rounds, indicating that U.S. investors place a heightened emphasis on scaling ventures in these emerging technologies.

When comparing global versus U.S. trends, the principal divergence lies in the timing and intensity of early-stage investments in AI × Crypto, with dramatic spikes in recent years in the U.S. compared to more moderate increases globally. This suggests that the U.S. continues to play a dominant role in nurturing advanced FinTech innovation and startups, despite regulatory uncertainty. A second trend in the figures is that investor attention is shifting from smaller seed bets in toward more substantial later-stage commitments for narrowly focused innovations (e.g., either AI or crypto in isolation), reinforcing the need to develop cohesive regulatory structures that can adapt to the scaling FinTech ecosystem.

Building on the stage-specific insights provided by Figures 3 and 4, Table 2 provides a complementary perspective by detailing average funding round sizes (in millions of 2012 U.S. dollars) for each FinTech subcategory across seed, early-stage VC, late-stage VC, and token sale rounds. While overall funding amounts in seed rounds have grown notably over time (particularly for AI-focused ventures), early-stage and late-stage VC categories account for the largest share of capital, which makes sense since much of the ecosystem hinges on scaling established startups rather than seeding new entrants. Late-stage AI deals, in particular, stand out from 2018 onward, indicative of investor confidence in the potential for AI solutions to mature and expand. By contrast, Crypto and AI × crypto rounds, while experiencing phases of dramatic growth, display a more volatile pattern, potentially reflecting the still-evolving regulatory uncertainties they face.

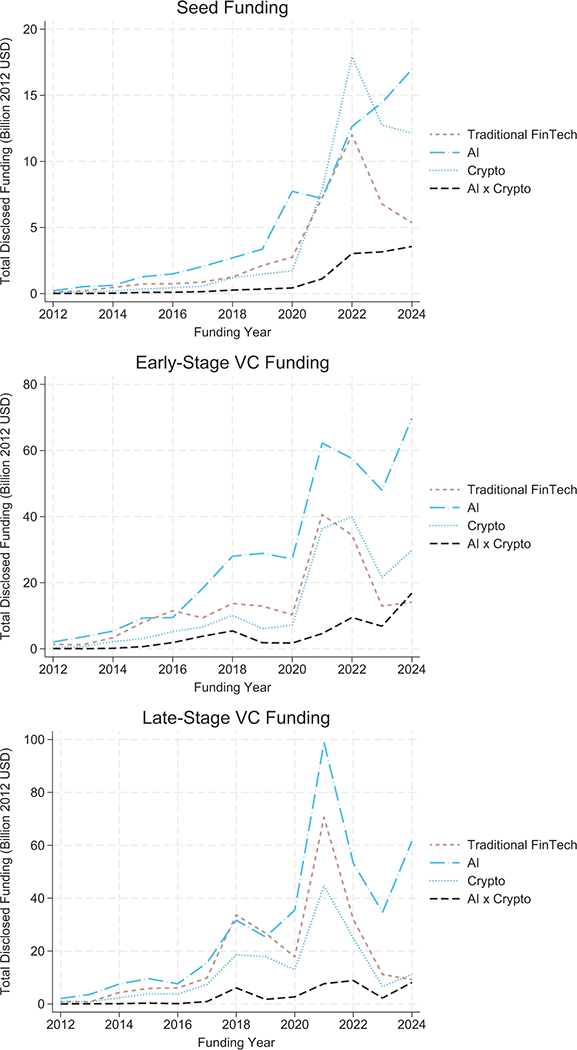

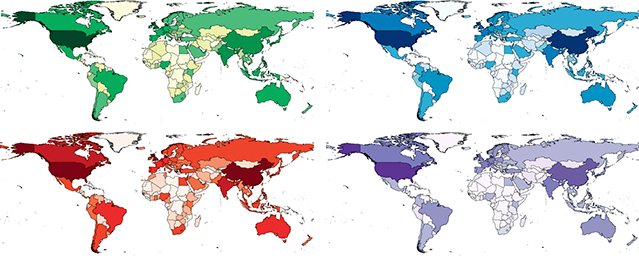

Figure 4 Heatmap of FinTech firms globally by subcategory. The figures depict the total unique FinTech firms by country. The firm’s business model has been categorized into traditional FinTech, artificial intelligence (AI), crypto, and AI × crypto. The green figure represents traditional FinTech (upper left). The red figure AI (lower left). The blue figure crypto (upper right), and the purple figure AI × crypto (lower right). The darker the color, the greater the concentration of startups. The color gradient moves from lightest to darkest with breaks at 1, 10, 20, 50, 200, 1000, 2000, 5000, and 30000 firms.

Figure 4Long description

This figure shows four world map heatmaps displaying the global distribution of FinTech firms by subcategory. The maps are arranged in a grid, each representing a different FinTech category, where color intensity indicates the concentration of startups by country. In the top left is Traditional FinTech, represented by a concentration map with green shading, where the darkest green indicates the highest firm density. The United States, parts of Europe (particularly the UK and Germany), China, and India have the darkest green coloring, indicating the highest concentrations of traditional FinTech firms. Other regions show varying lighter shades of green. The top-right map uses blue shading to represent the concentration of AI firms. Similar to the traditional FinTech map, the United States, China, parts of Europe, and India are colored the darkest blue. The pattern closely mirrors the traditional FinTech distribution but with some regional variations in intensity. The bottom left map displays Crypto startup concentration using red shading. The United States is depicted in a very dark red, indicating a high concentration. Parts of Europe, particularly the UK, also exhibit a dark red color. Other regions, including parts of Asia and some European countries, show moderate to light red shading. Finally, the lower right map shows the category of AI × crypto using purple shading. This map shows a more limited geographic concentration, with the United States being the dominant region. At the same time, most of the world remains very light purple or white, indicating lower firm density in this hybrid category. The color gradient moves from lightest to darkest with breaks at 1, 10, 20, 50, 200, 1000, 2000, 5000, and 30000 firms. The figure illustrates the total number of unique FinTech firms by country, categorized by business model type.

| Year | Trad. FinTech Seed | Trad. FinTech Early-Stage | Trad. FinTech Late-Stage | AI Seed | AI Early-Stage | AI Late-Stage | Crypto Seed | Crypto Early-Stage | Crypto Late-Stage | Crypto Token Sale | AI × Crypto Seed | AI × Crypto Early-Stage | AI × Crypto Late-Stage | AI × Crypto Token Sale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 1 | 10 | 23 | 1 | 8 | 20 | 1 | 8 | 37 | – | 1 | 9 | 7 | – |

| 2013 | 1 | 7 | 18 | 1 | 11 | 26 | 1 | 10 | 30 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 13 | – |

| 2014 | 2 | 12 | 63 | 1 | 11 | 41 | 1 | 21 | 66 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 23 | – |

| 2015 | 2 | 21 | 61 | 2 | 14 | 46 | 1 | 18 | 70 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 28 | 0 |

| 2016 | 2 | 31 | 53 | 2 | 13 | 40 | 1 | 24 | 80 | 9 | 1 | 31 | 16 | 9 |

| 2017 | 2 | 20 | 74 | 2 | 18 | 58 | 2 | 22 | 121 | 35 | 1 | 44 | 70 | 35 |

| 2018 | 2 | 24 | 213 | 2 | 24 | 101 | 2 | 32 | 204 | 140 | 2 | 64 | 243 | 15 |

| 2019 | 3 | 20 | 129 | 2 | 22 | 67 | 3 | 16 | 170 | 47 | 2 | 16 | 60 | 6 |

| 2020 | 3 | 16 | 84 | 5 | 18 | 80 | 2 | 17 | 110 | 6 | 2 | 15 | 81 | 6 |

| 2021 | 4 | 35 | 181 | 3 | 29 | 134 | 3 | 38 | 183 | 6 | 2 | 20 | 111 | 6 |

| 2022 | 5 | 32 | 114 | 4 | 27 | 106 | 4 | 34 | 135 | 5 | 3 | 29 | 117 | 15 |

| 2023 | 4 | 23 | 86 | 4 | 29 | 102 | 3 | 25 | 74 | 4 | 3 | 21 | 80 | 1 |

| 2024 | 4 | 25 | 93 | 6 | 48 | 197 | 4 | 42 | 140 | 3 | 4 | 67 | 225 | 2 |

Note: This table shows the average funding round size in $ millions of 2012 USD across four FinTech subfields: traditional FinTech, AI, Crypto, and AI × Crypto. These are global numbers.

The inclusion of token sale funding highlights another important way FinTech startups can raise funds for their business. Although ICOs achieved notoriety between 2017 and 2018 due to a slew of fraudulent offerings before falling out of favor, particularly in U.S. markets, due to intensifying regulatory scrutiny (Lyandres and Rabetti, Reference Lyandres and Rabetti2023). Nevertheless, the data indicate that private and public token sales continue to provide capital for crypto startups worldwide. This underscores the continued importance of token-based fundraising for specific segments of the FinTech community, and it aligns with a need to rethink optimal approaches to regulating token sales.

Finally, building upon the preceding analyses of funding dynamics, Figure 4 offers a geographic perspective on FinTech startups by illustrating the global distribution of unique FinTech startups in each subcategory with traditional FinTech in green, AI in blue, crypto in red, and AI × crypto in purple. Each panel employs a color gradient, where darker shades indicate a higher concentration of startups, with thresholds ranging from 1 to 30,000 ventures. This visual representation accentuates the extent to which certain countries have become FinTech hubs, revealing both macro-level dominance and subcategory-specific strengths.

Two countries, the U.S. and China, display dense footprints across nearly all FinTech subfields. India, the United Kingdom, and Canada emerge as significant second-tier centers, outpacing most other regions in terms of FinTech startups. Russia, Singapore, and Brazil are also highlighted by darker gradients in specific subcategories, indicating entrepreneurial strength, albeit focused a somewhat narrower set of specific FinTech applications like crypto. Interestingly, the transition from conventional FinTech to the most recent AI × Crypto wave reveals subtle yet important shifts in geographic clustering. While numerous European countries exhibit some depth in AI or Crypto individually, the U.S. stands out for its incredibly high concentration of AI × Crypto startups, surpassing China and all other countries in this combined category while being on par in individual categories like AI. This suggests that the U.S. may occupy a relatively advanced position in integrating AI and blockchain innovations, reflective of a confluence of capital availability, technological expertise, and entrepreneurial dynamics that collectively shape its FinTech landscape.

3 The Economics of FinTech Growth (Present)

The empirical evidence demonstrates substantial capital allocation and entrepreneurial activity across various FinTech domains. This pattern of investment and innovation raises a fundamental question: What economic forces are driving the development and adoption of these technologies? Building on the historical examples illustrating that financial innovation typically occurs in response to cost reductions brought about by technological progress or in response to institutional change, this section overviews the economic factors propelling innovation, adoption, and entry in various FinTech domains.

First, I provide a brief background on the institutional factors contributing to the supply and demand dynamics that has led to this era of FinTech innovations before subsequently diving into the details of specific cost-reducing technologies, including conventional FinTech applications (3.2), AI (3.3), blockchain, digital assets, and smart contracts (3.4), DeFi and DAOs (3.5), NFTs and SBTs (3.6), and finally, AI × crypto (3.7). The section concludes by reviewing the common economic themes that emerged regardless of the specific technology. Examining these forces helps to isolate the common economic distortions for which standard regulatory solutions exist, like price regulation or a firm’s entry and exit decisions. The review also helps clarify the extent to which unusual or novel distortions are arising that may necessitate new regulatory solutions.

3.1 The Supply and Demand Dynamics Driving FinTech Growth

The 2008 financial crisis is the primary institutional catalyst for the current era of FinTech innovation. The crisis revealed substantial shortcomings in regulation, highlighting how financial oversight struggled to keep pace with financial innovation, which was mostly centered around new products (e.g., new forms of securitization). This gap incentivized change through both necessity and opportunity. It prompted the development of new regulatory frameworks, entrepreneurial entry by FinTech startups, and questioning the financial system’s core risk management capability.

Specifically, in the 2008 financial crisis aftermath, a paradigm shift occurred in financial innovation, marking what, in retrospect, is the genesis of the modern FinTech era. The financial crisis shifted supply and demand. Namely, it increased the supply of talent working on financial inefficiencies and fundamentally changed the features consumers and investors demanded from their financial services providers. By exposing structural vulnerabilities within the traditional financial system, the crisis catalyzed both sides to realize that fundamental reforms were needed. Notably, given that certain financial innovations had contributed to systemic instability, there was a recognition that subsequent technological advancements would require a different approach.

On the supply side, this post-crisis environment reawakened those associated with the cyberpunk movement to work on solving the peer-to-peer money challenge. While many of the original pieces were there, it was the seminal whitepaper by Nakamoto (Reference Nakamoto2008), which introduced Bitcoin as a decentralized alternative to conventional financial infrastructure, and drew technical and engineering talent to financial system inefficiencies. The entrepreneurial talent in the high-tech sector started to reorient its expertise from cryptography and electrical engineering toward financial frictions and shortcomings of the system, therefore, it represents a defining characteristic of modern FinTech.

The financial crisis, however, did more than just shift talent. The 2008–2009 financial crisis, triggered by innovations in mortgage securitization, provides a stark illustration of how complexity and opacity can enable systemic risks to accumulate undetected. Securitization, which bundled residential mortgages into tradable securities, was initially designed to spread risk and lower borrowing costs. However, as Griffin (Reference Griffin2021) documents, this innovation became a vehicle for systemic risk due to pervasive misreporting, fraud, and conflicts of interest among key players. The complexity of these instruments obscured underlying risks while creating incentives for originators to extend credit to borrowers unable to sustain their loans.

This crisis experience shaped the subsequent FinTech revolution through a demand channel. First, the erosion of trust in traditional financial institutions created the demand for more trustworthy institutions. As such, business models emphasizing transparency and decentralization of power became more popular. Bitcoin’s introduction in 2008 explicitly positioned itself as a response to the crisis, offering a trustless, peer-to-peer financial system that would eliminate the need for potentially unreliable intermediaries. Second, increased regulatory oversight forced some banks to reduce traditional lending post-crisis. This created market opportunities for financial innovations that could improve access to financial services for these marginalized groups in a manner akin to the ATMs and credit cards of early innovation eras. For example, new platforms emerged to fill gaps in credit markets, with crowdfunding and peer-to-peer lending offering alternatives to traditional intermediation. Third, the 2008 financial crisis highlighted the importance of better risk assessment and monitoring tools. This demand for better intelligence, coupled with the massive cost reductions attributable to digitization, made it easy for executives to justify investments in the technologies that incorporate big data and advanced AI.

What are the massive cost reductions brought about by digitization? As Goldfarb and Tucker (Reference Goldfarb and Tucker2019) delineate, five cost changes came about because of digital technologies’ capacity to encode information as bits. Digitization reduces search, replication, transportation, tracking, and verification costs. This, combined with Moore’s law and Kryder’s law, which respectively posit the exponential growth of processing power and storage capacity, meant that computation and storage costs also declined. In such a state, it is natural to see an increase in the supply of applications using computationally intensive cryptographic proofs or big-data-driven AI algorithms.

3.2 Conventional FinTech Applications

Conventional FinTech applications, including digital payments, credit expansion via BNPL, peer-to-peer lending, and crowdfunding, are part of the first wave of FinTech innovations. Typically, traditional FinTech founders and innovators create a competitive advantage by introducing economic benefits such as reduced transaction costs and increased accessibility. However, these features that attract customers often pose novel regulatory challenges. For example, regulators face new concerns about consumer privacy and exploiting vulnerable populations. Despite conventional FinTech applications being incremental iterations of financial products and services that regulators are familiar with, the dilemmas they pose to regulators are similar to those brought about by more radical innovations like AI and DeFi. Therefore, a higher-level view of the economics of these conventional FinTech applications helps provide a valuable analogue to the economic issues that regulators face with the more radical innovations.

First, consider digital payments, which enable instant, remote transactions between two parties. These digital payments raise new privacy risks that do not exist with cash or traditional credit cards. Payment system operators can now collect detailed data on individual consumer purchases, including item-level data on what was bought, where, and when. This data can be combined with personal information like phone numbers, email addresses, and home addresses to build detailed profiles of consumers’ lives. Consumers are concerned about these infringements on their privacy, and over time, they have come to oppose their data being collected and shared (Goldfarb and Tucker, Reference Goldfarb and Tucker2012). Thus, a rationale for regulatory intervention in this setting is typically not about alleviating a specific constraint or distortion but about following the broad guiding principle of ensuring privacy. Thus, from a high-level perspective, it is worth evaluating how different ensuring privacy in payments is from settings like Meta’s more revolutionary attempt at a stablecoin or AI innovators’ decisions to include private data for training their models. Perhaps, surprisingly, the underlying economics are not that different.

At a high level, many U.S. laws and regulations encourage intervention if deception occurs. Now, consider this analogy. Just like large retail corporations cannot advertise a sale on TVs for $100 but only have one in stock, then lead the consumer who tried to buy the $100 TV to buy another similar yet much more expensive TV, in the FinTech context, startups should not be allowed to advertise convenience only to lead users to products that feature convenience bundled with data extraction, which is much more expensive to consumers. It is a classic bait-and-switch that exploits the underlying psychology of consumers. The lower advertised price “baits” the consumers, then the salesperson or AI-recommendation app “switches” the consumer to a higher-priced item. Therefore, users need to realize that whether it is a conventional FinTech application or a new Web3 application, some developers are attempting to deceive them, so they should exercise caution.

Insights from behavioral economics help to explain why consumers are vulnerable (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2013). Consumers are more likely to trust new products and services when they are easier to understand. New technology often provides intuitive, user-friendly interfaces that make it easy for consumers to adopt without deep thinking. Yet thinking through the risks of using such technology requires one to allocate attention to effortful mental activities and make complex calculations (e.g., my probability of being a victim of a cybercrime from sharing my data). However, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has long classified certain deceptive or unfair advertising practices and prohibits violating those advertising rules. Since 1968, the FTC has not permitted bait-and-switch advertising. Typically, if the FTC takes action against a company for false advertising, they are likely to issue a cease-and-desist order, and in some cases, to go a step further and require that the company engage in corrective advertising, in which the company explicitly states that the former advertising claims were untrue. Thus, one potential regulatory solution could be to go through the FTC and encourage FinTech startups to stop doing this and engage in corrective advertising that would serve a FinTech literacy role. FinTech literacy as a regulatory solution is discussed in greater detail in Section 5.

Next, consider a similar scenario with a mobile payment app that enables purchases with a single tap, and a proposed regulatory solution in California. The payments app collects data on every transaction, including what was purchased, where, and when. The app uses this data to provide personalized recommendations and offers, enhancing the user’s shopping experience. From an economic perspective, the convenience provided by the app is valuable. It saves time, simplifies budgeting, and offers tailored discounts, making the shopping process more efficient and providing users with higher utility. Psychologically, the user is driven by the ease of use and immediate benefits. The app’s interface is designed to be intuitive, requiring minimal effort to operate. The instant gratification of quick payments and personalized deals appeals to the user’s present bias. The user might also trust the app due to its association with a reputable brand, reinforcing their willingness to share personal data.

What did California regulators do when faced with a trade-off between enabling the growth of efficient digital payment systems and protecting consumer privacy? California implemented an outright ban, as outlined in the Song-Beverly Credit Card Act. The parallel from that Act would be to prohibit payment systems and merchants from requiring or requesting personal information as part of payment transactions, unless the consumer affirmatively opts in. This would preserve the privacy status quo from the cash/credit card era and maintain a level playing field across payment types. However, it could slow the adoption of digital payments because specific business models would not be viable without the ability to monetize consumer data. In this sense, startup entry would be lower with such bans, which could reduce overall consumer welfare. Thus, if one wants to preserve entrepreneurial entry, a solution based on FinTech literacy may be more appealing.

Another area of innovation in payments brought about by FinTech companies is BNPL, which is a form of short-term consumer credit that allows users to split purchases into installment payments, often with minimal or no fees if paid on time. BNPL has seen explosive growth in recent years, with transaction volumes rising from $33 billion in 2019 to an estimated $120 billion in 2021. This growth has been driven by increasing adoption by both consumers and merchants. From a consumer perspective, BNPL can help alleviate liquidity constraints and smooth consumption. By allowing consumers to break up payments over time with limited upfront commitment, BNPL can make purchases more affordable, especially for those with limited savings or credit access. Consistent with this, Balyuk and Williams (Reference Balyuk and Williams2023) find that liquidity-constrained consumers are more likely to use BNPL and that BNPL access facilitates expenditure smoothing around income shocks.

However, BNPL also carries risks of encouraging overspending and leading to debt accumulation, especially among younger and lower-income users. Maggio et al. (Reference Maggio, Katz and Williams2023) show that BNPL access increases spending levels for all consumers, even those not liquidity-constrained. They argue this is hard to explain with standard intertemporal substitution motives. It is more consistent with the “liquidity flypaper effect” where the additional retail liquidity from BNPL sticks where it hits, fueling short-term spending.

From the merchant’s perspective, offering BNPL as a payment option can significantly boost sales. Berg et al. (Reference Berg, Burg, Keil and Puri2023) conduct a randomized experiment with a large e-commerce retailer and find that the mere availability of a BNPL option at checkout increases sales by approximately 20 percent. The spending response to BNPL availability is much larger than to the availability of other payment methods like PayPal. Interestingly, Berg et al. (Reference Berg, Burg, Keil and Puri2023) find that the merchant’s profits from increased sales facilitated by BNPL outweigh initial costs in terms of consumer defaults, helping to rationalize the rapid merchant adoption of BNPL. However, to the extent that the market becomes saturated and BNPL becomes so ubiquitous that it leads to defaults, the long-run gains may not be so advantageous.

Thus, like we saw with payments and regulators’ difficulty in achieving a broad mission of ensuring privacy when behavioral economics is considered, behavioral responses to BNPL suggest regulatory challenges. In the long run, evidence indicates the potential for welfare-reducing overconsumption, increased defaults, and worse credit in equilibrium. For consumers facing liquidity constraints, the additional purchasing power and flexibility of BNPL can smooth consumption and improve welfare. However, the same features may induce some consumers to overspend in ways that ultimately reduce welfare. For merchants, the sales boost from BNPL can outweigh the costs, unless defaults and other risks are poorly managed. From a regulatory perspective, regulators must grapple with the counterfactual. BNPL is far from first best because of behavioral tendencies, but it may be superior to a counterfactual of payday lending. Moreover, regulatory interventions that may require segmenting populations based on their behavior are complex, often leading to framing solutions like opt-out versus opt-in, rather than one-size-fits-all information disclosures.

Third, consider P2P lending platforms, which offer the potential to expand access to credit by enabling direct matching of borrowers and lenders via online marketplaces. P2P lending can serve borrowers who struggle to get loans from traditional banks. They may also offer better rates to borrowers and higher returns to lenders by reducing overhead costs and enabling more granular risk-based pricing. However, P2P lending raises concerns around credit risk, investor protection, and fair lending compliance. Current P2P platforms make minimal disclosures to lenders about how loans are underwritten. Lenders may not understand the risks they are taking on. There are also concerns P2P lenders could bypass consumer protection laws and enable predatory lending or unfair discrimination using non-traditional data.

Regulators must balance the goal of expanding access to credit against the need to protect potentially vulnerable lenders and borrowers. Overly restrictive regulations could eliminate the cost advantages of P2P lending. However, under-regulation risks enabling excessively risky or abusive lending practices. One approach could be to subject P2P platforms to disclosure and oversight requirements similar to traditional consumer lending, including standardized reporting, usury limits, ability-to-repay rules, and fair lending audits. This would create a more level playing field. However, it may increase the costs of running the platform and reduce the supply of credit that such platforms provide.