Introduction

Technocracy and the role of experts in political decision making has become an increasingly debated topic (Bertsou & Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020a). There has been an expansion of independent, non‐partisan institutions, together with a frequent presence of technocrats in cabinets (Alexiadou, Reference Alexiadou, Bertsou and Caramani2020; Alexiadou & Gunaydin, Reference Alexiadou and Gunaydin2019; Dargent, Reference Dargent2015; McDonnell & Valbruzzi, Reference McDonnell and Valbruzzi2014). Citizens’ mistrust towards party politicians, party government and their capacities to answer contemporary challenges has favoured supportive attitudes of experts’ role in decision making (Bertsou & Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020b; Bertsou & Pastorella, Reference Bertsou and Pastorella2017; Bickerton & Invernizzi Accetti, Reference Bickerton and Invernizzi Accetti2017, Reference Bickerton, Invernizzi Accetti, Bertsou and Caramani2020; Caramani, Reference Caramani2017; Font et al., Reference Font, Wojcieszak and Navarro2015). Understanding how public attitudes towards that role evolve and develop is thus increasingly necessary.

Two related aspects deserve a closer look. The first one is the stability of the attitudes towards technocracy and experts’ role in political decision making. The second one is the public's preferences for different types of experts, given that they are not a monolithic group (Caramani, Reference Caramani, Bertsou and Caramani2020). The latter involves analyzing the way in which preferences for experts’ role in political decision making might vary according to the type of political problem to be handled and the specific professional background of the experts. This entails going beyond the study of general technocratic attitudes and to explore how different kinds of experts and framings of a political problem affect public preferences for experts’ role in real‐world scenarios.

As Bertsou and Caramani (Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020b) argue, public debate around technocracy will likely intensify as the complexity of problems and their management increase. These increased complexities will enhance the responsibility‐responsiveness tension (Mair, Reference Mair2009). Complex problems, for which the search of efficacious solutions within the standard margins of party government is especially challenging, will encourage preferences for policies drawing on expert knowledge. At the same time, policies aimed at responding to complex and multidimensional problems face trade‐offs when trying to attain goals difficult to reach simultaneously, and to represent diverse preferences and constituencies. In these cases, not even the ‘expert cure’ (Dommett & Temple, Reference Dommett and Temple2020) will be problem‐free, as the technocratic rhetoric suggests. Which goal should be given priority? Which experts should be given political authority? Which specialized knowledge should drive decision making? And to which political conflicts – or to which facets of any given political problem – should the expert knowledge be applied? These are all aspects that we should expect to be sources of conflict for complex and multidimensional contemporary policy controversies.

The COVID‐19 pandemic is, precisely, the epitome of how some contemporary problems challenge the capacity of national party governments to implement successful policies. But the COVID‐19 crisis also illustrates the difficulties of applying expert knowledge to solving complex and multidimensional problems. On the one hand, even if the pandemic – as a political crisis – shares features with some other types of external shocks that involve trade‐offs with distributive consequences, the magnitude and intricacy of the problem is unprecedented in contemporary history. During the COVID‐19 pandemic crisis, technocratic discourses in the form of statements stressing the need for a scientific approach for efficient problem solving have abounded. In this regard, the pandemic constitutes a situation of such complexity for conventional democratic governments that it may foster technocratic attitudes. On the other hand, the pandemic soon experienced politicization (Louwerse et al., Reference Louwerse, Sieberer, Tuttnauer and Andeweg2021) and, given its impact on both the public health and the economy, was publicly presented in such multidimensional light. Thus, the public debate around the management of the pandemic and its trade‐offs exemplifies the range of views regarding who the most adequate actors (party politicians or experts) should be in charge of the political management of any crisis. Very interestingly, in the case of preferring experts, there are also a range of views regarding what is the most appropriate expertise to follow. Thus, the COVID‐19 pandemic allows for a better comprehension of key dynamics that affect technocratic attitudes understood as favourable inclinations towards experts’ role in political decision making (Bertsou & Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020b).

Accordingly, this article has two main aims. First, we study the variation of technocratic attitudes following external shocks. Specifically, we analyze how the COVID‐19 pandemic has affected pre‐existing public attitudes towards the involvement of experts in political decision making. Next, we analyze another important element related to these attitudes: the types of experts preferred by the public. We analyze choices between a conventional party politician and an independent expert to manage the COVID‐19 crisis and we, then, focus on the circumstances that might influence the type of expert chosen to manage such a complex issue. Using a complex and multidimensional problem – the COVID‐19 pandemic – with both public health and economic facets, we analyze how the way in which the problem is framed, stressing its public health or its economic implications, affects the choice of the type of official preferred to manage such a problem.

We pursue the first aim by drawing on the results of panel data from two surveys conducted in Spain before (March 2019) and another during the pandemic (June 2020). The questionnaire in both survey waves measured technocratic attitudes with a battery of 10 questions validated by the most recent literature on the topic (Bertsou & Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020b). With this approach, we are able to capture the extent to which opinions about the role of experts have changed with the onset of the pandemic. We address the second goal by inserting a survey experiment in the June 2020 wave. The experiment combines two complementary and nested manipulations: a conjoint design (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014) and a framing experiment (Chong & Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007; Tversky & Kahneman, Reference Tversky and Kahneman1981). The conjoint captures preferences over whether independent experts or party politicians should manage the pandemic crisis in Spain. The framing manipulation evaluates whether such preferences are malleable depending on which dimension of the crisis is emphasized: public health or economic activity. Public preferences on the role of Mando Único, that is the Chief Officer in charge of leading the response to the coronavirus, are relevant because they likely affect citizens’ government evaluation and have electoral consequences (Heyne & Costa Lobo, Reference Heyne and Costa Lobo2021) given the prominence of the management of the pandemic crisis in the political debate.

Our study contributes to the scholarship on technocratic attitudes in several ways: First, the results reveal that, even with conservative estimates due to ceiling effects, technocratic attitudes have increased in the wake of the coronavirus outbreak, meaning that citizens manifest more favourable preferences for technocratic governance. This change is rather one of growth in the favourable attitudes towards experts’ involvement in political decision making than a change in other dimensions of technocratic attitudes, such as elitism or anti‐politics orientations. Second, we find that attitudes translate into choices when citizens are asked to pick a person to direct the governmental office in charge of leading the response to the pandemic, although this position implies, in addition to technical decisions, making political judgments and decisions affecting multiple levels of government. Our conjoint analysis shows that people's preference for technocrats is a dominant one: independent experts are more preferred than party politicians, and the expertise attribute overrides any other candidate characteristic. Finally, we provide evidence on the variation in the demand for different types of experts. Through our framing experiment, we find that the COVID‐19 crisis is associated with a particular call for expert knowledge in public health to manage the government response to the pandemic. However, the saliency of this type of expertise is conditional on the way in which the pandemic is framed and the lenses through which citizens interpret the challenges posed by the coronavirus crisis. Stressing the public health elements of the COVID‐19 crisis and its policy correlates amplifies the preference for experts with a professional background in the health sector, although such prevalence vanishes if the pandemic is framed with an emphasis on the economic impact of the coronavirus crisis, such as business closures and massive unemployment. When facing the latter situation, people are indifferent in their preferences for the type of expert, either a professional in public health or one in economics. These findings confirm that context – the specific political problem to be solved – conditions the widespread and favourable attitudes towards experts’ roles.

The paper is organized as follows: in the next section we provide a review on the concepts of technocracy, technocratic attitudes and preferences for experts. We also elaborate arguments to hypothesize on the stability of technocratic attitudes in the face of exogenous shocks as well as on the preferences for different types of experts. In the third section, we present the research design (the panel survey, the conjoint analysis and the framing experiment) and the main characteristics of the data. The results are presented and discussed in the fourth section. We conclude by highlighting our main findings and suggesting some potential avenues for further research.

Technocratic attitudes, their stability and the preference for different types of experts

Technocratic attitudes in times of crisis

Technocracy is the exercise of political power by an elite of experts based on their competence, efficiency, neutrality and expertise (Caramani, Reference Caramani2017; Centeno, Reference Centeno1993; Dargent, Reference Dargent2015; Fischer, Reference Fischer1990; Meynaud, Reference Meynaud1969). Technocracy, as a system of government, mode of making political decisions, form of representation or source of legitimacy of the political power, is premised on the advantages that experts supposedly have compared to elected party politicians. In the idealized technocratic interpretation, experts’ decisions would secure attention to the long‐term objective needs of the whole society above short‐term aims, particularistic goals, and the influence of special interests to which party politicians’ actions respond. Experts would make decisions according to a neutral, scientific, evidence‐based knowledge, procuring efficacious policies (Caramani, Reference Caramani, Bertsou and Caramani2020; Radaelli, Reference Radaelli1999; Sanchez‐Cuenca, Reference Sanchez‐Cuenca, Bertsou and Caramani2020). As a form of legitimation, technocratic reasoning is applied to a variety of grades of experts’ involvement, from non‐partisan technocratic cabinets and prime ministers to experts’ advisory roles (Pastorella, Reference Pastorella2016).

Although a growing body of literature has focused on the varieties of technocratic governance, the analysis of public support for experts’ involvement in decision making still is in a developing stage. This line of research has been developed in studies by Bertsou and Pastorella (Reference Bertsou and Pastorella2017), and Bertsou and Caramani (Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020b) on technocratic attitudes among European publics, extending the related and path‐breaking study by Hibbing and Theiss‐Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss‐Morse2002) on stealth‐democracy attitudes (see Coffé & Michels, Reference Coffé and Michels2014; Lavezzolo & Ramiro, Reference Lavezzolo and Ramiro2018; Webb, Reference Webb2013).

Technocratic attitudes, defined as attitudes ‘favourable to technocratic governance’ (Caramani, Reference Caramani, Bertsou and Caramani2020), involve being in favour of delegating decision capacity to experts, positive orientations towards experts’ competence and responsibility, and mistrust towards party politics and representative democracy. Bertsou and Caramani (Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020b) have defined three different dimensions within technocratic attitudes: orientations towards expertise, elitism and anti‐politics. Individuals showing technocratic attitudes display favourable orientations towards giving expertise and experts (individuals with superior education qualifications and sector expertise) a greater political role; elitist orientations, that is distrust towards people's political capacity and knowledge; and low trust in parties and elected politicians. Studies show that sizable sections of Western publics display technocratic attitudes (Bertsou & Pastorella, Reference Bertsou and Pastorella2017; Bertsou, Reference Bertsou2021; Bertsou & Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020b; Heyne & Costa Lobo, Reference Heyne and Costa Lobo2021).

The balance between legitimacy and efficacy promised by the representative democratic government ideal (Mair, Reference Mair2009; Caramani, Reference Caramani, Bertsou and Caramani2020) has been subject to populist and elitist criticisms. When that balance is not maintained in terms of the delivery of efficacious policies, when the system of government fails its promise of providing efficacy, the elitist critiques and the appeals for technocratic solutions are expected to grow together with the inclination of the public opinion to support technocratic arrangements. Representative democratic party government is experiencing challenges that make likely the rise of technocratic attitudes (Mair, Reference Mair2013).

In general, complex problems, severe crises and perceived incapacity of governments will favour the experts’ role for two additional reasons: first, because experts are thought to be able to elaborate and make decisions independently of the partisan bickering that might arise at critical times; second, because – facing situations of crisis that require an ‘objective’ judgement – experts are thought to be able to make decisions shielded from interest group's capture. Both reasonings relate to the de‐politicization of policy decisions suggested by the technocratic ideal. Consequently, the scientific and objective nature of expert knowledge results as especially appealing when party governments prove unable to govern competently (Caramani, Reference Caramani, Bertsou and Caramani2020). In short, party government should assure output legitimacy (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge2012) and when not delivered the calls for alternative political arrangements strengthen. Technocracy and the presumed competence of independent experts are presented as providing that extra output legitimacy (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1999). The growth in the support for technocratic arrangements and for an enhanced role for experts in political decision making should more likely take place in situations in which the public might identify a ‘party failure’ (Caramani, Reference Caramani, Bertsou and Caramani2020), a failure of the usual operations of party government.

The COVID‐19 pandemic and its management exemplify one of those situations. On the one hand, studies have found that satisfaction with governments’ pandemic responses has trailed COVID‐19 confirmed cases and mortality rates (Lazarus et al., Reference Lazarus, Ratzan and Palayew2020). Countries such as Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States have shown comparatively low levels of satisfaction with government responses, correlating with the severe impact of the pandemic (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Lee, Dong and Taniguchi2020). On the other hand, the technical complexity of the pandemic might transform it into a ‘hard issue’ (Carmines & Stimson, Reference Carmines and Stimson1980) and, as Bertsou (Reference Bertsou2021) finds, the public prefer experts over elected representatives in decision making at least for some hard issues. Using a simplified measurement of technocratic preferences, Amat et al. (Reference Amat, Falcó‐Gimeno, Arenas and Muñoz2020) find they grew during March 2020 in Spain.

Throughout 2020, the COVID‐19 pandemic has brought the role of experts in political decision making to the forefront of the public debate. While most of the discussion has been around giving experts and scientists a more prominent role in shaping the policy decisions to be then adopted by governments, there have also been some statements closer to the technocratic ideal, meaning that experts should have a leading role (even above political authorities) in handling the COVID‐19 crisis (see, for example, World Medical Association, 2020). During the first wave of the pandemic, in the Spring of 2020, the perceived lack of efficiency of the policies implemented by governments, the perception that governments were not doing enough and that they were not being able to keep the population safe, fostered mistrust in government (Fietzer et al., Reference Fietzer2020; Rieger & Wang, Reference Rieger and Wang2020) as well as pleas for the competence associated with scientific and experts’ skills. Whether these claims were properly technocratic, whether they aimed at scientists setting the policy goals or merely at guiding how to attain the goals defined by the government, the poor results of government policies nurtured the claims for a greater role of experts in decision making.

Therefore, in a critical situation as the one experienced during the COVID‐19 pandemic, we expect the support for technocratic attitudes to have grown when compared to the situation prior to the COVID‐19 crisis (Hypothesis 1). Additionally, and related to the first expectation, given the attributes the public associate to experts, we expect that individuals will prefer independent experts to party politicians to be in charge of the political and technical management of the COVID‐19 crisis (Hypothesis 2).

Preferences for different types of officials and experts

However, even if the technocratic ideal assumes the existence of an objective expert knowledge able to solve political problems benefitting the whole society, and even if relevant segments of Western publics seem to believe so, there is no sufficient evidence proving that this belief persists – and, more importantly, how – when confronted with real, immediate, complex and multidimensional problems. Who exactly are the experts? What type of experts are the ones preferred by the public? What are the qualifications valued by the public to solve specific problems? These are all questions for which we do not have clear answers with the current state of knowledge on technocratic attitudes. As Caramani (Reference Caramani, Bertsou and Caramani2020) argues, the expert elite is not a monolithic group; the public might show different predispositions to the involvement of different types of experts.

Following an accepted definition, we consider technocrats to be independent experts, with a high level of specialization derived from educational qualifications or professional experience, not affiliated to any party, unelected non‐partisan individuals without previous party‐political experience (Caramani, Reference Caramani, Bertsou and Caramani2020; Centeno & Silva, Reference Centeno and Silva1998; Tucker, Reference Tucker2018; Vibert, Reference Vibert2007). A technocrat is an expert with the capacity to make decisions; thus, she is an expert with executive capacity, not just the mere capacity to implement decisions adopted by the government (Bickerton & Invernizzi Accetti, Reference Bickerton, Invernizzi Accetti, Bertsou and Caramani2020; Caramani, Reference Caramani, Bertsou and Caramani2020; Meynaud, Reference Meynaud1969). Therefore, technocrats are experts, but not all experts are technocrats. A party politician might possess relevant expertise in a policy field, but that will not make her a technocrat because she is not an independent expert. Party politicians who have a professional specialization in a policy field and perform a government role are known as technopols (Alexiadou, Reference Alexiadou, Bertsou and Caramani2020) and they have been found to be preferred to non‐specialized party politicians in some contexts (Lavezzolo et al., Reference Lavezzolo, Ramiro and Fernández‐Vázquez2020), but they are not technocrats. Amidst this variety of different types of experts, one of our main goals and contributions is to understand better how the preference for the involvement of experts and technocrats in political decision making develops, and what are the mechanisms that make individuals prefer one type of expert above another.

Technocracy is essentially about knowledge meant to improve policies (Sanchez‐Cuenca, Reference Sanchez‐Cuenca, Bertsou and Caramani2020). Therefore, we should expect that which experts the public will consider most adequate to manage a political problem will vary depending on the nature of the specific problem. Additionally, because technocracy is based on the merits of the superior educational credentials or sector expertise of given individuals, and these qualifications are what legitimize the experts’ capacity to make decisions, we should expect the public to assess the adequacy of certain experts above others based not only on the nature of the problem, but also on the sector expertise of the experts. Hence, we deem it likely that the public will discern – among different types of experts – who, according to their sector expertise, can best handle a specific political problem. Accordingly, we derive our next set of expectations: that the preference for specific types of experts is conditional on the way in which the political problem to be handled is framed (see Hypotheses 3a and 3b).

The complex and multidimensional COVID‐19 pandemic poses a very suitable situation to test these expectations in a realistic context. We understand the COVID‐19 pandemic as an external shock, a multifaceted political problem with a single cause but with public health and economic facets. The management of the pandemic by all government officials has unveiled the multidimensional nature of the problem. After the first months of the pandemic, numerous government officials, incumbent politicians and opposition spokespersons in many countries have considered and traded the benefits of decisions prioritizing public health versus economic concerns. Almost every government spokesperson has highlighted at some point or another the existence of a trade‐off between public health and the economy when presenting the policies aimed at fighting the pandemic, and these trade‐offs have been constantly present in the public debate (see, for example, Covert, Reference Covert2020 and European Parliament, 2020). The cost of damaging the economy in order to save lives, the public health benefits of restricting people's mobility and business opening hours, the costs in public health terms of attenuating the restrictions on individuals and business and ‘reopening’ the economy quickly to minimize job losses, were all publicly debated. Therefore, we not only expect the public to prefer experts to party politicians to handle the pandemic crisis (as stated in Hypothesis 2), we also expect them to discern the type of expert most appropriate for adopting decisions, conditional on the facet (public health vs. economy) of the COVID‐19 pandemic crisis at stake:

-

• If the COVID‐19 pandemic is framed such that – besides its obvious public health and economic facets – the public health elements of the problem and its policy correlates are stressed, individuals will prefer experts with professional experience in public health to manage the problem more than in the control group scenario (Hypothesis 3a).

-

• If, however, the COVID‐19 pandemic is framed such that – besides its obvious public health and economic facets – the economic implications of the problem and its policy correlates are stressed, individuals will prefer experts with professional experience in economics to manage the problem more than in the control group scenario (Hypothesis 3b).

Research design and data

We test these hypotheses through a study of the Spanish case. The COVID‐19 pandemic affected Spain severely during the so‐called first wave (March–June 2020). The first death was recorded on 3 March, the pandemic spread and the confirmed cases of COVID‐19 grew exponentially reaching the peak of the curve at the end of March. The maximum number of daily deaths occurred at the beginning of April (almost 1,000 per day) and Spain became the country with most deaths per million. In mid‐March the government declared the State of Emergency entailing a near total lockdown, with business and education facilities closed and only the so‐called essential activities allowed. Some measures aimed at easing the dire economic consequences of the public health decisions were hastily implemented: publicly funded furlough schemes and income support programmes. The State of Emergency lasted between 13 March and 21 June, with the curve of the pandemic spread flattening at the beginning of June. Thus, in Spain the COVID‐19 crisis manifested harshly during the first half of 2020, with both very negative health (high number of cases and deaths) and economic effects (high figures of unemployment and workers in furlough schemes), and a multiplicity of policies aimed at attenuating these impacts and at managing the economy‐health trade‐offs (near‐total lockdown between March and May, easing of measures in May and June, declaration of State of Emergency, policies of economic support). The succession of dramatic public health and economic consequences made the ‘health versus the economy’ dilemma an ever‐present element in the public debate during the first semester of 2020 (El País, 2020b).

Our empirical analyzes combine two complementary strategies: panel data and two survey‐embedded experiments. With these two approaches we can estimate both the over‐time change in technocratic attitudes due to the emergence of the COVID‐19 pandemic and to study experimentally how the framing of the nature of this crisis affects preferences for who should be in charge of managing the situation.

The longitudinal analysis leverages the fact that we included the same set of 10 questions tapping technocratic attitudes in two surveys, the first fielded before the pandemic (March 2019) and the second administered while it was unfolding (June 2020). Of the 2,400 participants in the March 2019 survey, about 1,200 of them also participated in the June 2020 one. That is the sample used for the longitudinal analysis. Both surveys were administered by Netquest, a survey firm that recruits participants from a standing pool of respondents, in line with other firms like Yougov. The two survey samples are representative of the Spanish adult population in terms of gender, age and region of origin.Footnote 1

The 10 questions included in both waves were first proposed and validated by Bertsou and Caramani (Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020b) to provide a comprehensive measurement of technocratic orientations.Footnote 2 With this battery of questions we calculate an index based on their average. We also computed a Cronbach's alpha test to check that these items are internally consistent. The result gives us a scale reliability coefficient of 0.7, which is an acceptably high value for this type of exercise. In what follows, we present the question wording of each item and, with a descriptive purpose, we relate them to each of three dimensions of technocracy discussed in Bertsou and Caramani (Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020b): elitism, expertise and anti‐politics:Footnote 3

What is your degree of agreement with each of the following sentences? Use a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 means ‘totally disagree’ and 10 ‘totally agree’

Elitism

(1) Ordinary people don't know what policies are good for them

(2) Political leaders should make decisions according to their best judgment, not the will of the people

Expertise

(1) Politicians should be like managers and fix what does not work in society

(2) The leaders of my country should be more educated and skilled than ordinary citizens

(3) Social problems should be addressed based on scientific evidence, not ideological preferences

(4) The problems facing my country require experts to solve them

Anti‐politics

(1) The best political decisions are taken by experts who are not politicians

(2) Political parties do more harm than good to society

(3) Politicians just want to promote the interests of those who vote for them and not the interest of the whole country

(4) Politicians spend all their time seeking re‐election instead of fixing problems

Having fielded these questions before and after the COVID‐19 outbreak allows gauging whether the pandemic has affected attitudes towards technocratic arrangements. Moreover, it makes it possible to explore whether the change is larger for any specific dimensions of technocracy, elitism, expertise or anti‐politics. The panel structure allows us to evaluate the intra‐individual changes between the two waves, which does not mean that we can extract causal estimates, but it does mean that we limit the influence of many variables that do not usually vary over time.

Our second empirical approach moves beyond the measurement of technocratic attitudes to analyze choices as to whether an independent expert or a party politician should be in charge of managing Spain's government response to the COVID‐19 crisis. We also uncover preferences regarding whether the background of the candidate should be in public health or in the economy, two key facets of the crisis. To do so, we embedded an experiment in the second wave of the survey (June 2020) that combines two manipulations: a conjoint design and a framing experiment.

Conjoint designs are employed to reveal individuals’ preferences over objects with multiple traits in order to isolate the effect of each single trait on individuals’ choices (Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). We apply a conjoint design to examine survey respondents’ preferences over the type of person who should be at the top of the Spanish Mando Único (Chief Officer), a position created by the State of Emergency declared between March and June 2020 in Spain. It was the maximum authority in charge of coordinating the response of the central and regional governments to the COVID‐19 pandemic. The Mando Único was a key position: Nominated by the Prime Minister, this authority had ample executive capacity to establish rules and policies with legal force across the entire country. The Mando Único thus had to balance scientific criteria, on the one hand, with political considerations, on the other, particularly in dealing with elected officials in regional governments. Therefore, the Prime Minister faced the dilemma of appointing a trusted politician – thus ensuring political loyalty – or picking a well‐respected expert, eventually opting for the former.Footnote 4 The seriousness of the situation around the declaration of the State of Emergency entailed that the Mando Único position was subject to media scrutiny, with the main news outlets often covering the topic such that we can assume respondents are very likely familiar with the meaning of the official role (see, for example, ABC, 2020; El País, 2020a).

Our conjoint experiment presents respondents with pairs of candidates for the Mando Único position. Each candidate has the following traits:

-

• Gender

-

• Age

-

• Region of origin

-

• Type: expert versus party politician

-

• Professional background: public health versus economy

-

• Political party: none, Socialist Party, Popular Party, Podemos, Citizens, VOX.

The appearance of candidate profile pairs is the following:

When presented with the pair of potential heads of the Mando Único, respondents are asked to pick the one they think would be best for the job. Each respondent is presented with five pairs of candidates, one pair at a time. Values for all candidate attributes are fully randomized with only one restriction: expert candidates take the value none in the political party attribute. In other words, experts in our study are technocrats, that is technically proficient individuals that are not affiliated to any political party.Footnote 5

In our analyzes, we are particularly interested in the impact of the candidate's type – expert or politician – and in that of her professional background. Following the best practices in conjoint designs, we included the remaining traits – gender, age and region – for two purposes: First, to increase the realism of the candidate profiles. Second, and most crucial, to isolate the impact of candidate type from that of the other characteristics. Indeed, had we omitted the additional traits, respondents presented with a candidate who is, say, an expert, would likely make inferences about her gender, age or even region, thus conflating the impact of expertise with that of the other variables.

To evaluate whether exposing respondents to different interpretations of the nature of the crisis affects how they make their choices in the conjoint design, the survey includes a framing experiment (Chong & Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007; Tversky & Kahneman, Reference Tversky and Kahneman1981). The framing experiment appears in the survey before the conjoint design, that is, before respondents are asked to choose among candidate pairs. Each frame in this experiment is a statement that emphasizes a dimension of the COVID‐19 pandemic, either as a threat to public health or as an economic crisis. This design thus generates three experimental conditions: (1) control, (2) public health and (3) economy. Each respondent is randomly assigned to one of these experimental groups.

The control condition in the framing design presents a brief text stating that the crisis has both a public health and an economic dimension.Footnote 6 The public health and the economy frames begin with the control condition statement but then make a much stronger emphasis on either of the two dimensions of the crisis, public health or the economy. The former emphasizes the health risk associated with the virus and advocates the adoption of restrictive measures to fight it. The latter draws attention to the (dire) economic impact of the pandemic and proposes to ease restrictions to reactivate the economy. These two frames capture the essence of a key political and social debate raging during the Spring of 2020, which revolved around which dimension governments should prioritize: (1) whether to adopt measures to flatten the pandemic spread at the expense of economic activity or (2) to ease restrictions on mobility and business operations even if that could facilitate the pandemic spread. We estimate OLS regression models. All regression results using experimental data for the conjoint analysis are robust to the introduction of respondent fixed effects.

Results

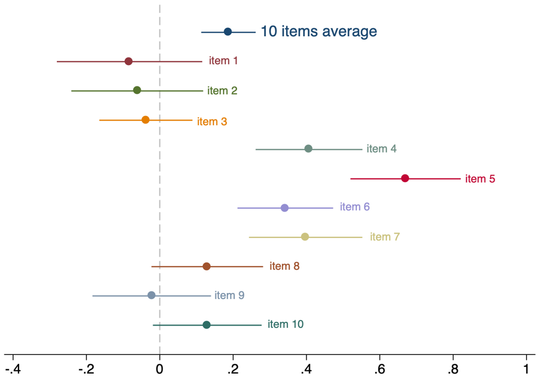

Figure 1 shows the average difference of the technocratic attitude index and of the 10 survey items separately between March 2019 and June 2020. Overall, the mean of the index has increased 0.19 points, moving from 6.84 in March 2019 to 7.03 14 months later. Although the magnitude of the change is apparently small, such an increase represents 15 per cent of the standard deviation of the dependent variable. We think it is worth reading these results in relative terms, considering that in the first wave half of the values of the technocratic attitudes index were concentrated on a 1.6 points range, that is, between 6.2 and 7.8, and that 95 per cent of the sample averaged their technocratic preferences between 5 and 9 on a 0–10 scale (see the Figure A.1 in the online Appendix for the distribution of technocratic attitudes in wave 1, and Table A.1 for descriptive statistics in both waves). The difference in means for the technocratic attitudes index is statistically significant and it empirically supports the expectations announced in the first hypothesis.

Figure 1. Changes in technocratic attitudes following the COVID‐19 outbreak. Respondents that participated in both survey waves (N = ∼1200). Each point presents the average change in opinion between March 2019 and 2020 together with its 95 per cent confidence interval. The 10 items of the technocratic attitudes battery are included. The uppermost result, 10 items average, reports how the 10‐item average has shifted between the two time points. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Once we examine each of the survey questions separately, it becomes clear that the behaviour of four specific items drives the increase of respondent's preferences for technocracy. The magnitude of the changes in items 4, 5, 6 and 7 between the two waves of the panel are 0.40, 0.67, 0.34 and 0.40, and they represent 17, 29, 17 and 18 per cent of the standard deviation of the respective items. Again, it is worth reading these magnitudes taking into account how the values of the responses on the 0–10 scale are distributed during the first wave of the panel. For items 4 and 5, 75 per cent of the sample had chosen a value between 7 and 10; for item 6 the concentration is even higher, 75 per cent of the sample had chosen values between 8 and 10; while for item 7 the segment that gathers 75 per cent of the sample is between the values 6 and 10. Hence, if anything, we may be underestimating the effect of the pandemic on these attitudes due to ceiling effects.

The behaviour of these four items across time allows us to draw a conceptual lesson. Items 4 to 6 have in common that they belong to one of the three dimensions of technocratic attitudes as discussed in Bertsou and Caramani (Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020b), that is, the orientations towards the ‘expertise’ side of technocracy; and item 7, although being part of the anti‐party aspect of technocracy, it also explicitly refers to preferences for experts over politicians. After conducting a confirmatory factor analysis, we confirm for the Spanish case that these four items, together, capture certain singularity as demonstrated by Bertsou and Caramani (Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020b) for nine other democracies; and so that the change of preferences in the wake of the coronavirus outbreak reveals an increase in people's preferences for experts rather than a change in the other two dimensions of technocratic attitudes, that is, elitism and anti‐politics sentiments.Footnote 7

The second hypothesis shifts from the realm of attitudes to that of choices. It focuses on whether independent ‘expertise’ is a valued trait among potential public officials in charge of managing the COVID‐19 crisis. As explained above, we have carried out a conjoint analysis where respondents are asked to select a candidate to fill the position of Mando Único (Chief Officer) evaluating a set of his/her attributes: gender, region of birth, age, type (independent expert or party politician), party affiliation and professional background/sector expertise (economy or public health).

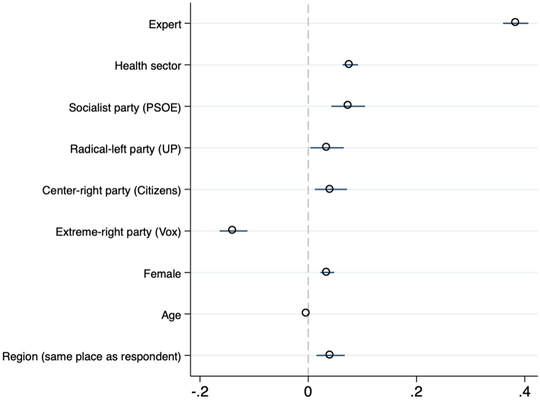

Figure 2 shows estimates for the average marginal component effects (AMCE) after regressing a dummy variable (that equals 1 if the candidate was selected and 0 otherwise) on candidates’ attributes. Coefficients can be interpreted as the marginal effect of a given attribute on the probability of choosing the candidate compared to the reference attribute value. For instance, regarding the type of candidate (whether or not she is an independent expert), being a party politician is the reference category. Thus, the ‘Expert’ coefficient indicates how being an independent expert – rather than a party politician – changes the probability of being chosen to take the position of Mando Único to coordinate and manage the government's actions to handle the pandemic. Given that we imposed some constraints in the randomization of attributes (as explained before, if the candidate type is ‘expert’ her party affiliation must be ‘none’), we factor all levels of all attributes, so we control for the variance introduced by the unequal randomization. Errors are clustered at the respondent level since each respondent is required to select one profile between a pair of candidates five times (five rounds of voting) and these observations are not independent.

Figure 2. Results: Estimates are AMCE from OLS regression. June 2020 wave (N = 2,037). The dependent variable is a dummy with value 1 if the candidate was selected and 0 otherwise. The independent variables are all levels of the candidate's attributes: Type (reference category: politician); Professional background (reference category: economy); Party affiliation (reference category: Conservative party (PP)); Female (candidate's sex: reference category: male); Age; Region (same place as respondent) (reference category: when the region of birth of the candidate and the interviewee do not match). Errors are clustered at the respondent level, with error bars showing 95 per cent confidence intervals. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Results in Figure 2 confirm the second hypothesis. Candidates with an independent expert profile are preferred to candidates with a political party profile. The ‘expert’ attribute increases the probability of being chosen by 38 per cent compared to candidates that are party politicians. This effect is statistically significant at a 99 per cent confidence level and it is robust to the inclusion of respondent fixed effects or other model specifications.Footnote 8 The magnitude of the impact of this attribute is larger than any other attribute shown to the interviewee. For example, if the candidate's profile indicates that the candidate's professional background is in the public health sector compared to the economic sector, the likelihood of being picked increases by only 7.7 per cent; being female versus male by 3.5 per cent; and a candidate matching the region of birth of the interviewees by 4.1 per cent.

Partisanship turns out to be less important than the expertise trait for respondents’ choices. Figure 2 shows the AMCE for candidate's party‐affiliation (Socialist party (PSOE), Radical‐left party (UP), Centre‐right party (Citizens) and Radical‐right party (Vox)) taking Conservative party (PP) membership as the reference category: everything else equal, a social democrat candidate (PSOE) has a 7.3 per cent higher probability of being chosen compared to a PP conservative candidate; profiles including candidates of Unidas Podemos (radical left) or Ciudadanos (center‐right liberal) yield also a positive effect compared with conservatives, 3.4 and 4.1 per cent, respectively; and being a candidate of the radical right party, Vox, decreases the probability of being chosen as Mando Único to manage the government response to the COVID‐19 pandemic about 14 per cent, that is, a considerable but still modest impact compared with the expertise pay‐off.

Another way to evaluate the importance of these political traits is to check how co‐partisanship between the candidate and interviewee influences the selection. To do so, we change the model specification substituting the rough variable of candidate's party affiliation by a dummy that equals 1 when the party that the respondent voted for in the last Spanish general election (2019) matches the candidate's party affiliation, and 0 otherwise. We find that co‐partisanship increases the probability of choosing that candidate by 8.8 per cent, while the effect of being an independent expert (vs. being a party politician) decreases just a little, from 38 to 35 per cent.Footnote 9 This result implies, for instance, that a PSOE voter, everything else equal, prefers an independent expert than a party politician from the PSOE.

These results indicate that being an independent expert, a technocrat, is the most important characteristic when assessing which profile would be the most suitable to lead the management of the pandemic. Crucially, this is a position that involves technical but also political decisions. We have been able to isolate the importance of this attribute thanks to the methodological advantages provided by conjoint analysis. This finding adds to a set of empirical studies confirming people's preferences for experts’ involvement in decision making (Bertsou & Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020b; Bertsou & Pastorella, Reference Bertsou and Pastorella2017).

As we reasoned in the formulation of Hypotheses 3a and 3b, however, we still lack knowledge about the type of experts that are valued and the specific contexts in which society demands them. In this sense, the scenario generated by the coronavirus outbreak offers a good opportunity to explore these issues, because during the management of the first wave of the COVID‐19 there were different views on how the governments should react: emphasizing the need to prioritize public health versus stressing the need to re‐launch the economic activity.

With this aim, we have complemented the conjoint experiment with a framing experiment where, before choosing between pairs of candidates, respondents are exposed to either a public health or an economy manipulation drawing their attention to different facets of the COVID‐19 crisis. This situation allows us to explore whether the framing of the crisis induces variation in the demand for different types of experts. Specifically, we do so by interacting the type attribute (independent expert/party politician) with the professional background attribute (economy/public health) for each experimental group in the framing experiment. This allows examining whether the framing of the crisis shapes preferences over which type of expert should lead the management of the crisis.

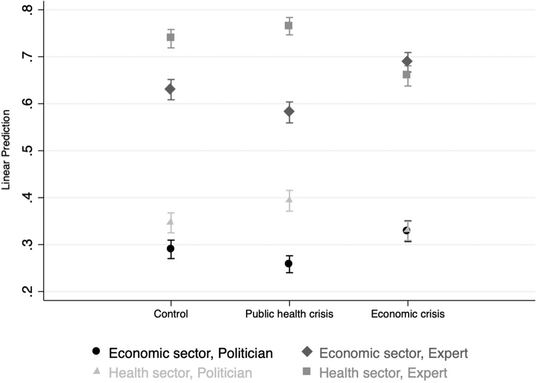

Figure 3 shows the results of this exercise and addresses Hypotheses 3a and 3b. The figure presents different predictions of the probability of being chosen based on the combination of the two attributes mentioned above for each of the three framing scenarios: a manipulation of public health crisis, a manipulation of economic crisis and the group of control. The simulations are built from the AMCE estimates as a result of OLS regressions in which a triple interaction between the type, professional background and frame is included (see Table A.3 in the online appendix for the whole set of regression results).

Figure 3. Results: Predictions on the probability of being selected Chief Officer to manage the COVID‐19 pandemic given the framing received prior to the conjoint design, the candidate's type and the candidate's professional background. June 2020 wave (N = 2,037). Simulations are built from OLS estimates where the dependent variable is a dummy with value 1 if the candidate was selected and 0 otherwise. The independent variables are two dummies to capture the effect of the manipulations (framings) plus all levels of candidate's attributes. A triple interaction between the type, professional background and framing variables is introduced. Errors are clustered at the respondent level, with error bars showing 95 per cent confidence intervals.

As a benchmark, we begin analysing the results of the control group, that is, those respondents who have been asked to choose a candidate to lead the response to the COVID‐19 without having been framed on whether the crisis mainly demanded measures to alleviate the effects on the economy or on public health. According to predictions, we confirm that the differences between independent experts and party politicians found in the validation of the previous hypothesis are not completely blurred when we disaggregate by professional background. Overall, we see a significant gap between independent experts (working either in the healthcare or economic sector) and party politicians (working either in the healthcare or economic sector).

However, there are some differences within independent experts (technocrats) and within party politicians. For those interviewees that were not exposed to any frame about the coronavirus crisis, there is a higher preference for experts in public health than for experts in economics. The difference between the two profiles is about 10 points in the probability of being chosen: the prediction that a candidate with independent expert + public health sector background is picked is 73 per cent, while the prediction for a candidate with independent expert + economic sector background is 63 per cent. Regarding the differences within party politicians, we find that respondents slightly prefer those working in public health than in the economic sector (35 and 29 per cent, respectively).

These baseline results indicate that, on the one hand, expert knowledge per se has its own value, meaning that people's preference for independent experts (technocrats) persists in real situations of crisis with multidimensional problems to be handled and, on the other hand, that the sector expertise also matters. In this case, a professional background in the area of public health is more valued than in the area of the economy to coordinate and manage the response to the coronavirus crisis, and such difference is statistically significant. We will now evaluate whether the way in which the COVID‐19 crisis is framed influences these findings.

The second column in Figure 3 shows the predictions on a candidate's probability of being chosen when people are previously framed on the pandemic with an emphasis on the public health elements of the crisis and its policy correlates. With this frame, the difference between experts (technocrats) in public health and in economics is amplified. The probability that an expert working in the public health area will be chosen is 76 per cent, while the probability of an expert from the economic sector being selected is 58 per cent. This is an 18 percentage points difference between the two types of experts, which constitutes an increase of 8 points in relation to the result found for the respondents in the control group. This difference is statistically significant at conventional levels of hypothesis testing and it confirms the expectations announced in Hypothesis 3a.

This amplification of the effect of the professional background also happens, and to a greater extent, among party politicians. After framing COVID‐19 fundamentally as a health crisis, a candidate who is a party politician with a professional background in the public health area has a probability of being elected as Mando Único of about 39 per cent, while one in the economic area has a probability of 26 per cent. This 12 percentage points difference within politicians represents more than double the one found for the control group.

Moving towards the third column of estimates in Figure 3, we see that framing the COVID‐19 pandemic as a situation that has inflicted severe costs to the economy and that requires decisive immediate actions to re‐launch the economy also produces changes in a candidate's probability of being chosen in the pairwise election compared to the results for the control group. The differences between the experts with divergent professional backgrounds almost disappear if respondents are primed with an economic crisis manipulation. The probability of being picked as COVID‐19 Chief Officer (Mando Único) is now a little bit lower if the candidate is an expert working in the public health sector (66 per cent) compared with a candidate that is an economic expert (69 per cent). Hence, the difference favouring public health experts moves from 10 percentage points in the control group (and 18 points in the public health manipulation group) to 3 points in favour for economists. In other words, the dominant preference for a public health professional over economists that we have seen so far vanishes if the experimental subjects are framed with the idea that the pandemic involves a series of important economic consequences. The direction of this change is in line with our expectations. However, the magnitude of the change is not enough to validate Hypothesis 3b. Because although individuals do prefer experts with economic expertise over public health professionals when the coronavirus crisis is stressed as an economic problem, the difference is not statistically distinct from 0. We acknowledge that such an expectation was demanding given the nature of the crisis as a public health one.

As a side note, it is worth mentioning that in the case of candidates that are not independent experts but party politicians the difference between professional backgrounds also vanishes: the prediction on the probability of being chosen is 33 per cent irrespective of the sector of their professional background (notice that both points in Figure 3 overlap).

Jointly considered, these findings reveal novel aspects of technocratic attitudes. First, that preferences for experts increase in the context of an exogenous shock as the one experienced with the coronavirus. Second, we find that, without manipulation, people give particular importance to public health experts, which makes sense given the type of crisis the COVID‐19 is. However, we see that the preference for public health expertise is sensitive to the framing of the pandemic challenge, increasing its prominence if the crisis is primed exclusively as a public health problem and blurring it if the economic implications of the crisis are stressed. This last finding points to the existence of heterogeneous preferences on an expert's involvement in policy making conditional on the context and the type of expertise. People shape their technocratic preferences based on the specific political problem to be solved.

Conclusion

Thanks to a research design including a panel survey, a conjoint experiment and a framing experiment, this article enhances our knowledge both on the extension and nature of technocratic attitudes in several ways. We show that technocratic attitudes have grown after the COVID‐19 external shock. These attitudes, thus, vary depending on the political context and such an external shock not only affects government popularity and other political attitudes (such as political trust), but also increases technocratic attitudes. Besides this, when confronted with a technically complex hard issue (Carmines & Stimson, Reference Carmines and Stimson1980) such as COVID‐19, individuals prefer independent experts to party politicians in decision‐making roles. Therefore, we confirm the resilience of technocratic attitudes (Bertsou & Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020b) and support preliminary evidence on the pre‐eminence that experts (rather than elected politicians) have in the eyes of the public when the issue at stake is a technically complex one (Bertsou, Reference Bertsou2021). Finally, we demonstrate how sector expertise or professional background, as well as the framing of the problem at stake, also influence the public's preferences for experts. In the context of the COVID‐19 outbreak, people give more weight to a professional background in public health when choosing the person to lead the technical and political response to the pandemic. Such preference is intensified if the coronavirus crisis is framed mostly as a public health problem but it is overridden if the pandemic is presented with an emphasis on the economic difficulties derived from the COVID‐19 outbreak. Hence, technocratic preferences are malleable and conditional.

These findings expand our knowledge on the tensions between representative party government and technocratic arrangements, and on the responsibility‐responsiveness trade‐offs affecting contemporary democracies (Caramani, Reference Caramani2017; Mair, Reference Mair2013). They point towards a sustained public disposition to prefer technocratic solutions over the conventional representative democratic ones, especially under circumstances of severe crisis as the ones presented by the COVID‐19 pandemic. Our results demonstrate that an external shock has the capacity to alter basic political orientations on the nature of the political regime: representative party democracy versus technocracy. Our findings have important implications regarding how technocratic attitudes challenge representative democracy. That the increase in technocratic attitudes is driven by a growth of pro‐expertise preferences, while the elitist and anti‐politics components do not change, might entail that technocratic attitudes are not such a grave danger for democratic politics, even if they might be clearly associated to political dissatisfaction and distrust towards governments. However, our results also show that technocratic preferences are relatively deep‐rooted and consistent, and not merely abstract orientations. Individuals not only tend to prefer experts when confronted with real‐politics situations and net choices, they also discern between different types of preferred experts depending on the features of the situation they face. Given the electoral correlates of technocratic attitudes (Heyne & Costa Lobo, Reference Heyne and Costa Lobo2021) this consistency further increases their relevance.

A caveat that applies is that part of the empirical evidence we provide relies on experimental designs, which could diminish the external validity of the findings. As experiments go, however, the specific designs we have implemented seek to maximize the realism of the situation: the conjoint refers to an actual choice that the Spanish Prime Minister had to make and the candidate profiles are as complete and as ‘lifelike’ as possible. The framing statements, moreover, reflect actual debates that were raging at the time the survey was administered. Hence, our approach combines the internal validity of experiments with the purposeful choice of designs that maximize external validity.

Certain aspects deserve further research. We should study the future evolution of technocratic preferences once the immediate effects of the COVID‐19 shock have attenuated to assess whether they return to the pre‐crisis levels. Other exogenous shocks have been found to influence political attitudes and preferences (e.g., Colantone & Stanig, Reference Colantone and Stanig2018; Foster & Frieden, Reference Foster and Frieden2017). As for the COVID‐19 pandemic, external shocks provide information on governments’ capacity to manage and handle complex problems (Ashworth et al., Reference Ashworth, Bueno de Mesquita and Friedenberg2018). Whether these effects are durable is more uncertain and seems to depend on multiple circumstances. Shocks with a large economic or social impact and lengthy in duration (as the pandemic was) might induce durable effects and their impact on attitudes may stick. In fact, previous pandemics have had important and durable effects on citizens’ attitudes (Aassve et al., Reference Aassve, Alfani, Gandolfi and Le Moglie2021). The COVID‐19 crisis thus has the potential to effect an enduring change in technocratic attitudes that will need to be assessed over time. Beyond the pandemic, one could foresee the likely frequent emergence of other major crises and shocks in the future (for example, related to climate change) that will imply additional situations where our findings on technocratic attitudes will be relevant.

Additionally, we should examine the relation between the growth of technocratic attitudes and the evolution of authoritarian attitudes, so as to explore the different ways in which a potential weakening of the support for representative party democracy might be taking place. Expanding recent work by Bertsou (Reference Bertsou2021) and Ganuza and Font (Reference Ganuza and Font2020), the public's understanding of what an expert is, the stages of decision‐making in which experts are preferred, and the type of issues on which their expertise is valued above party politicians also deserve further attention.

Acknowledgements

We thank Laura Morales, the anonymous reviewers and the editors for helpful feedback.

Funding information

This research was supported by a grant from the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness Program. Grant number: CSO2017‐89847‐P. Luis Ramiro benefited from a grant by the Fondation Maison des Sciences de l'Homme (France), Programme Directeurs d'Etudes Associés DEA 2020.

[Correction added on 8 November 2021, after first online publication: Funding details has been added in this version.]

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A.1. Summary statistics for each of the 10 survey items tapping on technocratic attitudes (wave 1 and 2).

Figure A.1. Quartiles distribution (boxplot) of 10 survey items tapping on technocratic attitudes and technocratic index (average) in Wave 1.

Figure A.2. Robustness check: The impact of candidate's attributes on the probability of being chosen (AMCE).

Figure A.3. Robustness check: Regression result with a (Co)Partisanship specification model

Table A.2. Framing experiment. Statement presented in each experimental condition

Table A.3. Regression result (AMCE): triple interaction between manipulation frame, candidate's type (expert vs. politician) and candidate's professional background (public health vs. economy)

Supplementary information