3.1 Assessing the Level of Policy Triage

In Chapter 2, we introduced the concept of policy triage and discussed the factors accounting for the variation in the degree of policy triage across implementation authorities. Now, we demonstrate how these conceptual and theoretical considerations can be studied empirically. We start with a detailed discussion on how we assess the level of policy triage. We then present our empirical understanding of the explanatory factors that account for variation in the frequency and intensity of policy triage. In the third step, we reflect on the rationale for our case selection. Finally, we detail our methodological approach to assess our dependent and independent variables.

We rely on the concept of organizational policy triage to compare variation and changes in organizational implementation performance. Policy triage involves prioritizing some policies or implementation tasks over others to handle a growing implementation burden with limited resources.

In essence, any type of triage decision involves both losses and gains. For instance, in the area of medicine, where the concept of triage was initially developed, it means “sorting” patients based on their needs for care and prioritizing the treatment of some patients over others (FitzGerald et al., Reference FitzGerald, Jelinek, Scott and Gerdtz2010). While modern medical triage systems are designed to maximize the number of survivors, it still means that some patients have to wait longer or receive lower quality health services (losses), while others are treated immediately with the best medical care possible (gains). Similarly, in the context of policy implementation, policy triage implies that implementation bodies strategically move resources from the execution and enforcement of one or some policies to others. The impacts of these triage decisions and what they imply for overall implementation performance depend on two aspects.

First, it makes a difference how many policies are covered by such a triage “system.” Triage frequency captures how often implementation bodies engage in trade-off decisions and whether resource redistribution occurs between some or all policies an implementation authority is in charge of. Second, it is important to know whether prioritization implies that implementing authorities completely disregard some policies or tasks or only reduce the scale of activities associated with implementing certain policies. In contrast to triage frequency, triage intensity thus refers to the scope of resource redistribution. In combination, we can expect that organizational policy triage is particularly pronounced if triage decisions are taken frequently and, at the same time, entail the extensive reshuffling of resources between different policies.

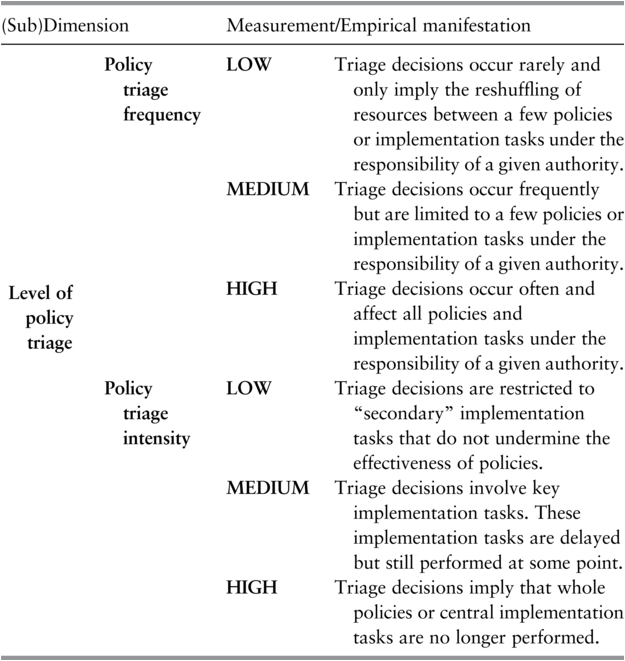

To allow for a direct comparison of the two dimensions, we rate both triage frequency and intensity as “low,” “medium,” or “high.” “Low” triage frequency means that triage decisions rarely occur and involve the reshuffling of resources between a few policies or implementation tasks. “High” triage frequency, by contrast, entails that trade-offs in implementation occur often and that almost all policies and implementation tasks under the responsibility of a given authority are subject to triage decisions. Triage intensity can be considered “low” if some policies are (partially) neglected to the advantage of others, but this negligence is restricted to secondary implementation tasks (consultation, research activities) that do not directly undermine the effectiveness of a given policy. “High” triage intensity implies that there are far-reaching trade-offs between policies, resulting in a situation where organizations completely quit and abandon the implementation of certain policies or central implementation tasks, such as on-spot inspection or the monitoring of emissions of dangerous pollutants. “High” triage intensity also means that implementation tasks requiring accurate analysis and control, such as the authorization of industrial plants or the granting of social allowances, are merely “rubber-stamped” by the implementation body instead of thoroughly examined.

For both triage frequency and intensity, “medium” constitutes an intermediate category. This is the case if, for instance, triage decisions occur rather frequently but only involve trade-offs among a limited number of policies and implementation functions. Likewise, we might talk of “medium” triage intensity if central implementation tasks are not fully suspended but put at the end of the “queue.” In other words, central implementation tasks are substantially delayed but (still) performed at some point. Our central considerations are summarized in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1Long description

The table has two columns for subdimension and measurement or empirical manifestation. It has a row for the level of policy triage, which has two sub-rows labeled policy triage frequency and policy triage intensity. Each sub-row is divided into low, medium, and high. For policy triage frequency: Row 1. Low. Triage decisions occur rarely and only imply the reshuffling of resources between a few policies or implementation tasks under the responsibility of a given authority. Row 2. Medium. Triage decisions occur frequently but are limited to a few policies or implementation tasks under the responsibility of a given authority. Row 3. High. Triage decisions occur often and affect all policies and implementation tasks under the responsibility of a given authority. For policy triage intensity: Row 4. Low. Triage decisions are restricted to secondary implementation tasks that do not undermine the effectiveness of policies. Row 5. Medium. Triage decisions involve key implementation tasks. These implementation tasks are delayed but still performed at some point. Row 6. High. Triage decisions imply that whole policies or central implementation tasks are no longer performed.

3.2 Assessing the Determinants of Policy Triage

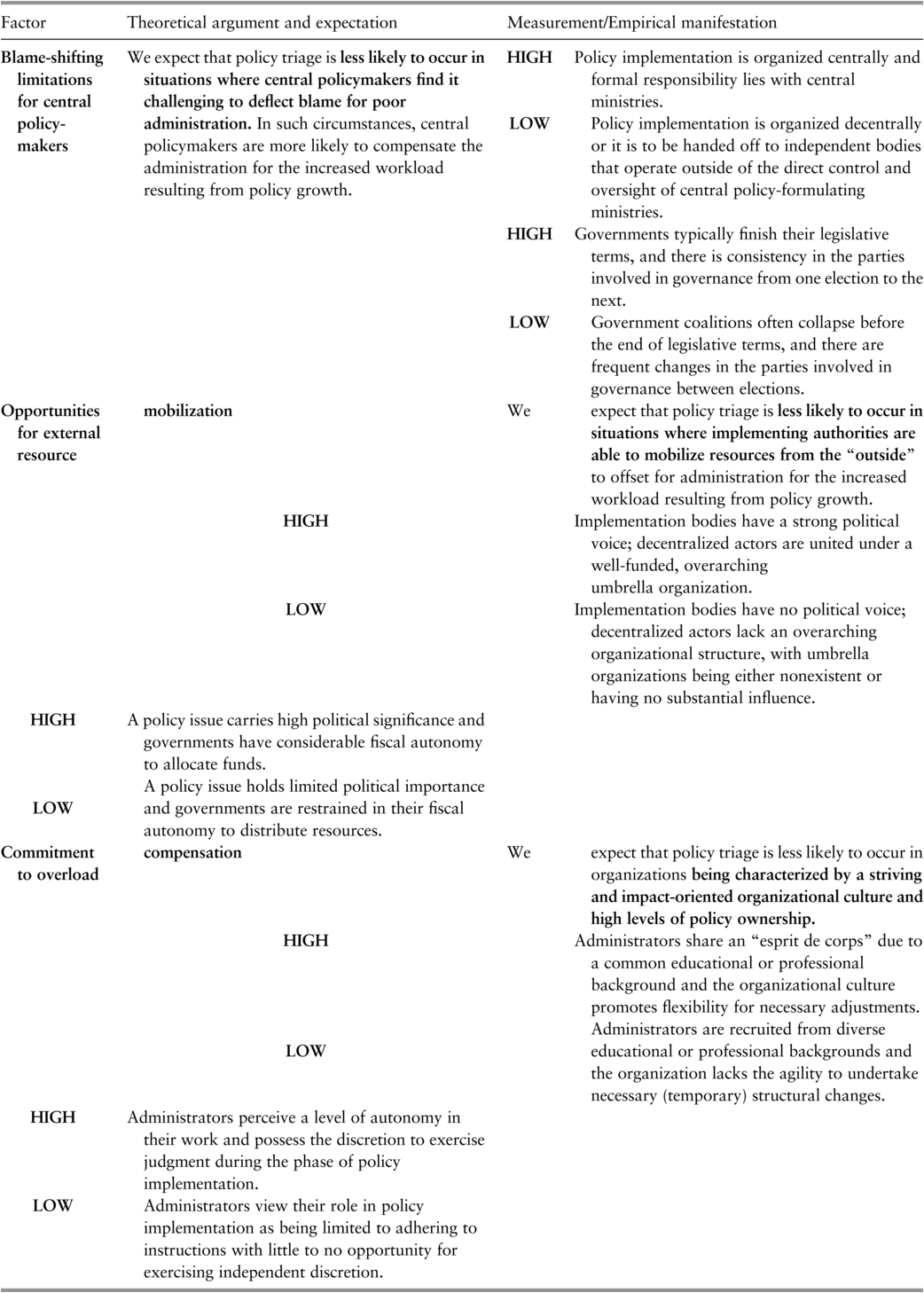

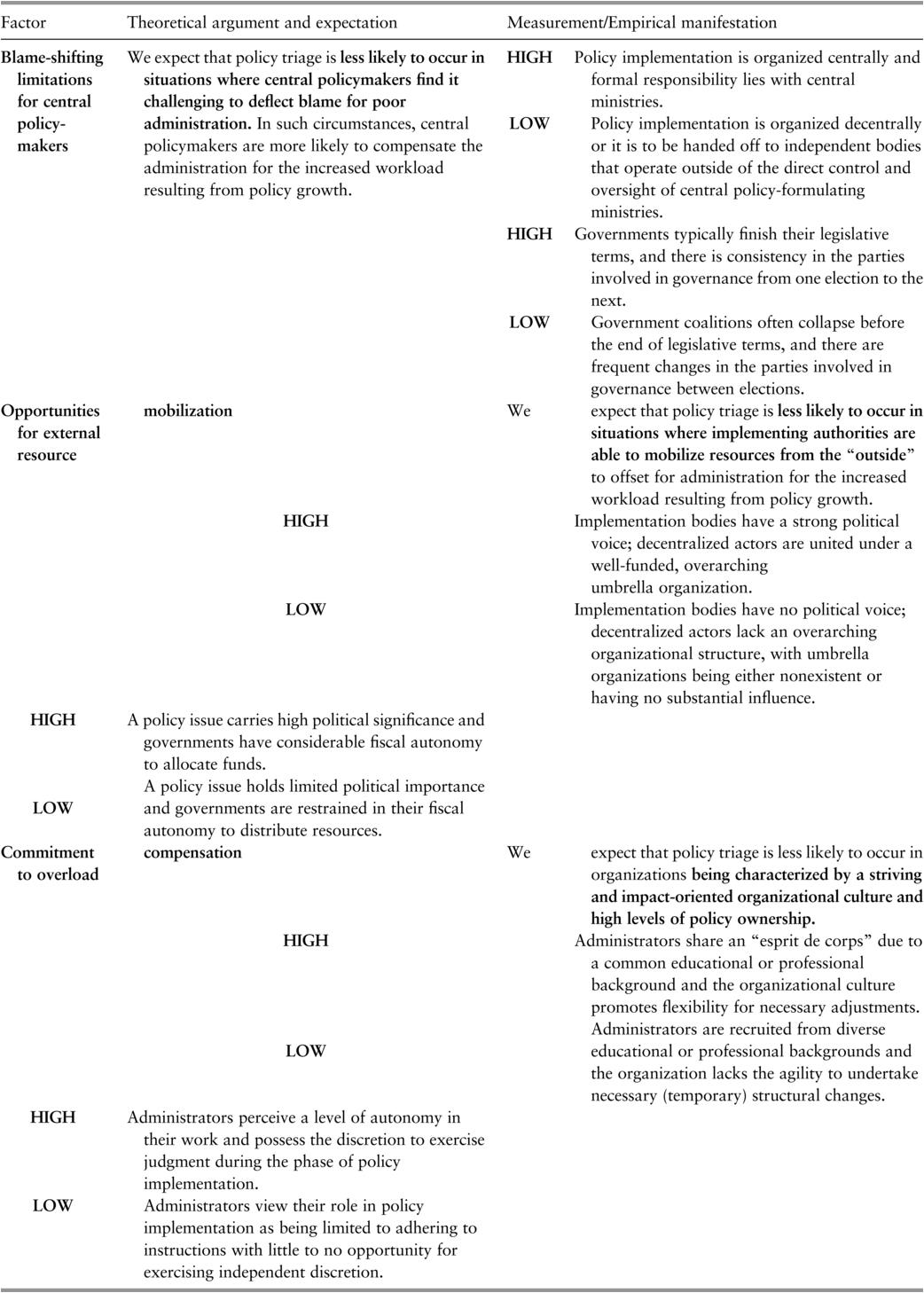

In Chapter 2, we identified three distinct factors to determine the level of policy triage. These are (1) blame-shifting limitations for central policymakers; (2) the implementation authorities’ opportunities to mobilize external resources; and (3) the extent to which implementation authorities are committed to making things work despite lacking resources.

We argue that (1) political blame-shifting limitations for central policymakers arise from various factors, including the design of delegation structures and political stability. Empirically, two distinct delegation “models” can be identified: The first is a centralized model where the policy formulators are also involved in policy execution, meaning the entity that creates policies is responsible for their implementation. The second, a decentralized model, involves delegating significant implementation responsibilities to local entities or independent organizations, often outside the direct oversight of central policy-formulating ministries. In the centralized configuration, the close involvement of the central ministry in implementation activities makes it more difficult to shift political blame, leading to a “high” limit on blame-shifting opportunities. In contrast, the decentralized approach allows central policymakers to distance themselves from direct implementation responsibility and accountability, providing them with broader avenues to shift blame for any failures, thus indicating a “low” limit on blame-shifting opportunities.

Following a similar logic, we expect that political stability increases the responsibility for policy success or failure. Essentially, we anticipate that policymakers will engage more diligently in the policymaking processes when there is a greater likelihood that they will be responsible for implementation, rather than passing the baton to a future government. Put simply, if they are the ones to “face the music,” we predict they will compose their policies with greater care. To assess a country’s political stability, we rely on two main indicators: On the one hand, political stability is considered “high” when legislative terms are completed without the dissolution of the government coalition or the initiation of a vote of no confidence. Likewise, stability is marked as stronger when at least one member of the governing coalition remains in power over consecutive terms. Conversely, countries experiencing frequent premature termination of legislative terms and significant shifts in governing parties after elections are categorized as having a “low” level of political stability.

Secondly, we evaluate the implementation authorities’ capability to procure external resources by examining two key factors. First, for implementation authorities to successfully acquire external resources, they must have a political voice. Second, there must be a general availability of resources to draw upon.

In order to mobilize additional resources from external sources, implementers require a political voice. They need the ability to form and articulate a unified opinion on the one hand and must be given the opportunity to convey their concerns to policymakers on the other. Proper articulation requires an organization to be able to gather feedback from different subunits in order to assess resource requirements on an organizational scale. Consequently, well-organized authorities are more likely to articulate their concerns and opinions effectively, as opposed to those that are more fragmented. Furthermore, implementers operating within a decentralized model – such as local authorities – encounter another challenge. While it might be presumed easier for smaller organizations to gauge their resource requirements, the necessity for coordination to forge a unified stance across multiple entities introduces a layer of complexity. We argue that this complexity can be alleviated by the presence of well-resourced, influential umbrella organizations such as local government associations, for example. When demands are leveraged via such organizations, we expect chances to acquire additional resources to increase significantly as opposed to a scenario where multiple implementers attempt to act independently.

Implementers then also need to be provided the opportunity to express their needs in consultations with the formulating level, formally and/or informally. However, the frequency of these consultations is less critical than whether implementers find them to be effective. The key is not merely the occurrence of discussions but whether these interactions lead to tangible outcomes, such as increases in resources. Simply put, the value of consultations is measured by their impact, recognizing that talk is cheap without subsequent action and thus may not suffice to address the implementers’ needs. Therefore, we categorize political voice as “high” in situations where organizations can effectively articulate their resource needs to a receptive and responsive audience. Conversely, we label political voice as “low” for organizations that struggle to define their needs coherently and lack the channels to effectively convey their stance to those in a position to address them.

The general availability of resources for policy implementation is not always limited by a lack of communication but often by the actual resources that can be mobilized. Resource availability varies across sectors and countries, with some countries naturally having access to more resources than others. Although taking on debt is a potential strategy to enhance administrative capacity, it becomes less feasible for countries that had (parts of) their fiscal control being transferred to international or supranational organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or the European Commission. A notable instance illustrating this constraint was the oversight by the “European Troika” of the budgets of various Southern European countries starting in 2010. Furthermore, the significance attributed to different policy areas can influence resource allocation, with governments tending to prioritize sectors that have a direct impact on citizens’ lives. Fernández-i-Marín, Knill, Steinbacher & Steinebach (Reference Fernández-i-Marín, Knill, Steinbacher and Steinebach2024) found that policies affecting citizens directly are more likely to receive funding. For instance, the implementation of social benefits is closely watched by the public, who can easily gauge the effectiveness of policy execution based on the timely receipt of promised benefits. Conversely, evaluating the enforcement of air quality standards might be more challenging for most.

Considering these elements, we define the general availability of resources as “high” in scenarios where governments have significant freedom to make budgetary decisions and when societal attention on an issue is strong. This includes situations free from international fiscal oversight and self-imposed financial limitations, like debt brakes. Conversely, we view resource availability as “low” in contexts where budgetary autonomy is restricted by external controls and societal interest or awareness in a policy area is minimal.

Thirdly, we evaluate the degree to which implementation authorities demonstrate commitment to success despite resource constraints based on their organizational culture and the degree of policy ownership. We focus on two aspects that enable organizations to develop a proactive, impact-oriented culture that enables administrators to go beyond their roles. A key factor identified in literature is the degree of heterogeneity within the organization. Administrators who share a common educational or professional background typically find it easier to align on a common goal and objective. This is because they are likely to have similar foundational knowledge and understand common practices and principles within their field.

Therefore, we classify the level of extra engagement to be “high” in scenarios where staff members predominantly share a professional background, and the organizational culture promotes flexibility for necessary adjustments. Conversely, this propensity is considered “low” in settings where staff come from varied professional backgrounds and the organization lacks the agility to undertake necessary (temporary) structural changes in response to challenges.

Another factor that may influence the commitment of implementation authorities is the level of policy ownership. Policy ownership refers to the extent to which administrators perceive their role in policy implementation as independent and significant rather than as mere recipients of orders and instructions. It gauges the meaningfulness of the policy to the administrators and their belief in the impact their actions have within their operations. This sense of ownership motivates administrators to be more proactive and invested in the policy implementation process, recognizing themselves as independent and crucial contributors to the policy’s success. We classify the level of policy ownership as “high” when administrators feel they have a certain autonomy and discretion to exercise judgment during the implementation phase. Conversely, we consider it “low” when administrators feel only “instrumentalized,” confined to a rigid role that limits them to executing directives and leaves little to no space for personal initiative or decision-making autonomy.

Table 3.2 summarizes the theoretical dimensions considered and the indicators we use to measure them. At the indicator level, we apply a simple aggregation rule: The overall value is classified as “low” if all subdimensions are also rated “low.” The same applies to a “high” overall value when all individual ratings are “high.” If the ratings are divergent – for example, a mixture of “high” and “low” – we classify the overall value as “medium.”

Table 3.2Long description

The table has three columns for factor, theoretical argument and expectation, and measurement or empirical manifestation. Measurement or empirical manifestation has two sub-rows for high and low.

Row 1. Blame-Shifting Limitations for Central Policy-Makers:

Theoretical argument and expectation: We expect that policy triage is less likely to occur in situations where central policy-makers find it challenging to deflect blame for poor administration. In such circumstances, central policy-makers are more likely to compensate the administration for the increased workload resulting from policy growth.

Measurement or empirical manifestation: High: Policy implementation is organized centrally and formal responsibility lies with central ministries. Policy implementation is organized decentrally or it is be handed off to independent bodies that operate outside of the direct control and oversight of central policy-formulating ministries. Low: Policy implementation is organized centrally and formal responsibility lies with central ministries. Policy implementation is organized decentrally or it is be handed off to independent bodies that operate outside of the direct control and oversight of central policy-formulating ministries. High: Governments typically finish their legislative terms, and there is consistency in the parties involved in governance from one election to the next. Low: Government coalitions often collapse before the end of legislative terms, and there are frequent changes in the parties involved in governance between elections.

Row 2. Opportunities for External Resource Mobilization:

Theoretical argument and expectation: We expect that policy triage is less likely to occur in situations where implementing authorities are able to mobilize resources from the outside to offset for administration for the increased workload resulting from policy growth.

Measurement or empirical manifestation: High: Implementation bodies have a strong political voice; decentralized actors are united under a well-funded, overarching umbrella organization. Low: Implementation bodies have no political voice; decentralized actors lack an overarching organizational structure, with umbrella organizations being either nonexistent or having no substantial influence. High: A policy issue carries high political significance and governments have considerable fiscal autonomy to allocate funds. Low: A policy issue holds limited political importance and governments are restrained in their fiscal autonomy to distribute resources.

Row 3. Commitment to Overload Compensation:

Theoretical argument and expectation: We expect that policy triage is less likely to occur in organizations being characterized by a striving and impact-oriented organizational culture and high levels of policy ownership.

Measurement or empirical manifestation: High: Administrators share an esprit de corps due to a common educational or professional background and the organizational culture promotes flexibility for necessary adjustments. Low: Administrators are recruited from diverse educational or professional background and the organization lacks the agility to undertake necessary temporary structural changes. High: Administrators perceive a level of autonomy in their work and possess the discretion to exercise judgment during the phase of policy implementation. Low: Administrators view their role in policy implementation as being limited to adhering to instructions with little to no opportunity for exercising independent discretion.

3.3 Policy Sector, Countries, and Organizations Under Study

We intend to develop and test a theory of policy triage that transcends national boundaries or contextual settings. To achieve this, we must show that our key theoretical considerations can account for variations in policy triage levels across a “diverse” range of conditions, ensuring they are not constrained to a specific set of circumstances (Seawright & Gerring, Reference Seawright and Gerring2008). We maximize the variation in contextual conditions across two dimensions, that is, the type of implementation work that must be performed and the broader institutional context in which implementing authorities operate.

To ensure a comprehensive variation concerning the first aspect, our attention is directed toward two distinct sectors: environmental and social policy. Environmental policy implementation requires attention to tasks such as licensing and oversight of industrial entities, strategic land-use management to harmonize industrial expansion with conservation imperatives, and stringent monitoring of greenhouse gas emissions along with other pollutants (Kaplaner & Steinebach, Reference Kaplaner and Steinebach2024; Nielsen, Reference Nielsen, Buffat, Hill and Hupe2015; Sevä & Jagers, Reference Sevä and Jagers2013). In contrast, the realm of social policy, especially when addressing unemployment and child benefits, is fundamentally geared toward individual support (Lipsky, Reference Lipsky2010). This involves setting up and sustaining services to help the unemployed find appropriate jobs, providing skills training to improve job prospects, and ensuring regular child benefits to support families. Simply put, while social policy primarily focuses on service delivery, environmental policy emphasizes enforcement (Hupe et al., Reference Hupe, Hill and Buffat2015; Winter, Reference Winter, Peters and Pierre2012). In addition to this, the two systems follow different “accountability” mechanisms. While in social policy, citizens can directly evaluate the quality of the services they receive, this is notably more challenging in environmental policy. In the realm of environmental policy, the support of environmental “watchdogs” is crucial for evaluating the effectiveness of policy implementation (Fernández-i-Marín et al., Reference Fernández-i-Marín, Hinterleitner, Knill and Steinebach2023a). This distinction could potentially influence how administrations approach the challenges of task prioritization and the (re)allocation of resources.

Considering the second dimension, the institutional backdrop in which public administrations operate is both complex and multifaceted. It spans a broad spectrum of considerations, from the level of centralization versus decentralization to the nature of interactions with the private sector. Additionally, there are varying perceptions of the roles that public administration should embody and execute. While administrators always have to follow both economic and democratic principles and considerations, they differ in their tendency to be oriented toward one of these “values” in practice (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Goerdel and Nicholson-Crotty2011). In what is termed as “managerial systems,” administrators are expected to run policy programs as efficiently and smoothly as possible. In legalistic systems, by contrast, the public sector is considered to be rule-bound and rule-following, with civil servants being primarily responsible for the proper execution and enforcement of public policies. These variations are likely to influence the adoption of specific strategies when handling increased implementation demands.

According to Peters (Reference Peters2021), the values, structures, and relationships of public administration vary significantly according to countries’ administrative traditions. An administrative tradition is “one way of creating a more comprehensive explanation of the structure and behavior of public bureaucracies (…) that defines the nature of appropriate public administration within a society” (p. 23). To ensure our results are not restricted to one specific administrative culture or influenced by factors inherent to a particular administrative background, we are examining implementing authorities in six countries, representing distinct administrative traditions (Painter & Peters, Reference Painter and Peters2010). The countries under study are Denmark (Scandinavian tradition), Germany (Germanic tradition), Italy and Portugal (Napoleonic tradition), as well as the United Kingdom and Ireland (Anglo-Saxon tradition).

Countries within the Germanic and Napoleonic traditions tend to prioritize the legalistic facets of public administration (Fisch, Reference Fisch, Sommermann, Krzywoń and Fraenkel-Haeberle2025). In contrast, those in the Anglo-American tradition lean more heavily toward managerial perspectives. The Scandinavian countries, in turn, are considered a mixture of the two “extremes” but with tendencies toward the latter (Loughlin & Peters, Reference Loughlin, Peters, Keating and Loughlin1997; Verhoest et al., Reference Verhoest, Roness, Verschuere, Rubecksen and MacCarthaigh2010). The key difference between countries in the Germanic and Napoleonic traditions lies in the interplay between central and subnational governance levels. In the Napoleonic model, bureaucrats are often seen as agents of the central government to ensure the uniform application of national policies. Meanwhile, the Germanic tradition grants bureaucrats greater autonomy, emphasizing their expertise as specialized professionals in their respective spatial and professional areas. While these might be broad-based distinctions between different countries and systems that are also prone to changes over time, recent studies have shown that these distinctions in administrative approaches are also evident in surveys focusing on administrators’ attitudes toward administrative change and innovation (Lapuente & Suzuki, Reference Lapuente and Suzuki2020).

It is important to note that even within the same sector and country, the “polity of implementation” (Sager & Gofen, Reference Sager and Gofen2022) typically comprises multiple implementing authorities. Depending on the precise administrative architecture, this can involve authorities at both the central and the subnational levels (Steinebach, Reference Steinebach2022). For every sector and country studied, we must thus further determine where the implementation tasks exactly fall. This is done and discussed in each chapter individually.

Despite the considerable differences among the public authorities in terms of their operational tasks (social service delivery versus environmental enforcement) and the institutional settings in which they operate (different administrative traditions), they all have witnessed substantial growth in the policies they need to implement. As shown in each of the individual chapters, public administrations in our sample nowadays face broader responsibilities than ever before. Not only are they tasked with implementing a greater number of policies but these policies do also vary significantly in nature.

3.4 Methodological Approach

Policy triage can come in different forms. In the example presented in the introduction of this book, for instance, the leadership of England’s Environment Agency (EA) established a formal policy triage system that was imposed and administered from the “top.” In other cases, in turn, policy triage might manifest itself in more informal routines with the exact same result, namely, that some policies or implementation tasks are privileged over others. Similarly, our key independent variables result in part from the formal features of sectoral policymaking structures and procedures. At the same time, it also depends on more informal characteristics such as the organizations’ “esprit de corps” and how strongly administrations use the institutional opportunities provided and streamline the internal procedures to actively counterpose administrative overload. In consequence, our methodological approach and data collection methods must be able to capture both the formal and informal features of the organizations in charge of policy implementation and the broader setup they are embedded in.

To deal with these different needs, we base our analysis on a combination of secondary literature, document analysis, and interviews. While the secondary literature and public documents were primarily (but not exclusively) consulted to inform the assessment of our independent variables, the expert interviews were mainly conducted to elicit views on how policy triage is practiced within the implementing authorities under scrutiny.

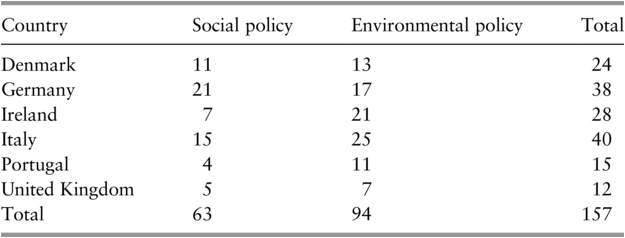

Our analysis is based on a comprehensive review of official documents with legal, statutory, or organizational relevance, originating from parliamentary, governmental, or administrative bodies. The materials consulted include reports from national and international evaluators such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), annual reports and financial statements of implementing organizations, records of parliamentary debates, and evaluations by stakeholders, including environmental advocacy groups. Furthermore, we conducted 159 anonymous, semi-structured interviews to enrich our understanding and gather diverse perspectives on the subject matter.

With regard to the interviews, we employed a purposive sampling strategy. We interviewed implementers working in different types of social and environmental implementation authorities in their countries. Depending on the exact institutional setup and the allocation of implementation tasks and competencies, this involved implementers from central agencies, state-level agencies, or local authorities. All interviews were conducted via phone or Zoom between April 21, 2021, and March 10, 2023, and each one lasted between 25 and 125 minutes (with an average of about 50 minutes). Table 3.3 summarizes the number of interviews conducted for each country and policy sector.

| Country | Social policy | Environmental policy | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | 11 | 13 | 24 |

| Germany | 21 | 17 | 38 |

| Ireland | 7 | 21 | 28 |

| Italy | 15 | 25 | 40 |

| Portugal | 4 | 11 | 15 |

| United Kingdom | 5 | 7 | 12 |

| Total | 63 | 94 | 157 |

The table indicates that with the exception of Germany, we consistently conducted a higher number of interviews in the environmental policy sector than in the social policy sector. The need for a greater number of interviews in our study stems from the decentralized nature of environmental policy implementation. This area of policy typically involves a diverse range of organizations, necessitating extensive interviews to ensure a thorough understanding. Moreover, environmental policy execution relies heavily on local implementers in many countries, making it crucial to conduct a broader set of interviews. This approach helps to account for local idiosyncrasies that might not reflect the experiences of all implementers, providing a more balanced and comprehensive perspective on the implementation process. Furthermore, the varying number of interviews across countries underscores the relationship between the number of interviews needed and the complexity of a country’s administrative framework. For example, our research required a greater number of interviews in countries with decentralized systems, like Germany, as opposed to those with more centralized structures, such as Portugal and Denmark.

After the interviews and the transcription, all interviews were anonymized. Anonymity increased the likelihood that our interviewees discuss their practices and circumstances openly. Moreover, we expected that political principals could use interview results to target and blame specific interviewees who admitted that they could not do their job as stipulated in their contracts. This concern was also substantiated by multiple interviewees who, at the outset of their interview, sought further assurance from us regarding the confidentiality of their remarks.

Compiling insights from multiple officials and sources to aggregate knowledge at the organizational level comes with several challenges. To ensure the reliability of the information gathered, we adopted a “negotiated agreement approach” as outlined by Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Quincy, Osserman and Pedersen2013). This process involved at least two coders engaging with each transcribed interview, assessing the organization and its context relative to core indicators discussed earlier. In the second step, coders compared their interpretations. In cases where discrepancies emerged, they discussed their codes to reach a consensus for the final version. If disagreements persisted, a third coder was brought in for further deliberation. Once all discrepancies were resolved and agreed upon, we went through all cases of negotiated agreements, double-checking the accuracy of the final coding. This rigorous process enhanced the reliability and validity of our data, lending credibility to our research outcomes.

3.5 Conclusion

In this chapter, we clarified how we study the levels of policy triage and its principal explanatory factors. To concretize the abstract concept of policy triage into measurable components, we distinguished between the frequency of policy triage occurrences and their severity. Additionally, we have detailed our empirical approach to understanding the determinants that influence the levels of policy triage. For a comprehensive examination, we strategically selected six “diverse” countries and two policy sectors. The countries chosen exhibit variations in their administrative traditions. The policy sectors examined – social policy and environmental policy – involve a broad spectrum of responsibilities from delivering public services to enforcing environmental regulations. This methodical choice of cases enables us to test our theoretical propositions in distinct contextual settings.

From a methodological standpoint, we have argued that the study of our dependent and independent variables necessitates the use of a mix of secondary literature, document analysis, and expert interviews. While we predominantly relied on secondary literature and public records to inform the assessment of our independent variables, the expert interviews provided indispensable insights into the actual practices of policy triage within the agencies under examination. This multifaceted approach not only facilitates the identification of a consensus within organizations but also helps to verify and triangulate the information collected.

In the subsequent seven chapters, we aim to accomplish two primary objectives. Firstly, we will demonstrate that the levels of policy triage systematically vary according to the explanatory factors we have identified. Secondly, we aim to substantiate the assertion that policy triage patterns are not the product of singular factors but rather emerge from the complex interplay and configuration of multiple factors.