Technology means constant social revolution.

Language has a curious way of sticking around. We still say “the sun rises,” even though we know it is we who turn into the sun. So it shouldn’t surprise us that we’ve inherited the largest, most powerful, and most centralized infrastructure for shaping thought and behavior in human history, but we still haven’t gotten around to calling it what it is. We persist in describing these systems as “information” or “communication” technologies, despite the fact that they are, by and large, designed neither to inform us nor help us communicate – at least in any way that’s recognizably human. We beat our breasts about “fake news” and other varieties of onerous content because it’s easier than taking aim at the fundamental problems with the medium itself: that it’s an answer to a question no one ever asked, that its goals are not our goals, that it’s a machine designed to harvest our attention wantonly and in wholesale.

The proliferation of ubiquitous, portable, and connected general-purpose computers has enabled this infrastructure of industrialized persuasion to do an end run around all other societal systems and to open a door directly onto our attentional faculties, on which it now operates for over a third of our waking lives. In the hands of a few dozen people now lies the power to shape the attentional habits – the lives – of billions of human beings. This is not a situation in which the essential political problem involves the management or censorship of speech. The total effect of these systems on our lives is not analogous to that of past communications media. The effect here is much closer to that of a religion: it’s the installation of a worldview, the habituation into certain practices and values, the appeals to tribalistic impulses, the hypnotic abdication of reason and will, and the faith in these omnipresent and seemingly omniscient forces that we trust, without a sliver of verification, to be on our side.

This fierce competition for human attention is creating new problems of kind, not merely of degree. Via ubiquitous and always connected interfaces to users, as well as a sophisticated infrastructure of measurement, experimentation, targeting, and analytics, this global project of industrialized persuasion is now the dominant business model and design logic of the internet. To date, the problems of “distraction” have been minimized as minor annoyances. Yet the competition for attention and the “persuasion” of users ultimately amounts to a project of the manipulation of the will. We currently lack a language for talking about, and thereby recognizing, the full depth of these problems. At individual levels, these problems threaten to frustrate one’s authorship of one’s own life. At collective levels, they threaten to frustrate the authorship of the story of a people and obscure the common interests and goals that bind them together, whether that group is a family, a community, a country, or all of humankind. In a sense, these societal systems have been short-circuited. In doing so, the operation of the will – which is the basis of the authority of politics – has also been short-circuited and undermined.

Uncritical deployment of the human-as-computer metaphor is today the well of a vast swamp of irrelevant prognostications about the human future. If people were computers, however, the appropriate description of the digital attention economy’s incursions upon their processing capacities would be that of the distributed denial-of-service, or DDoS, attack. In a DDoS attack, the attacker controls many computers and uses them to send many repeated requests to the target computer, effectively overwhelming its capacity to communicate with any other computer. The competition to monopolize our attention is like a DDoS attack against the human will.

In fact, to the extent that the attention economy seeks to achieve the capture and exploitation of human desires, actions, decisions, and ultimately lives, we may view it as a type of human trafficking. A 2015 report funded by the European Commission called “The Onlife Manifesto” does just that: “To the same extent that organs should not be exchanged on the market place, our attentional capabilities deserve protective treatment … in addition to offering informed choices, the default settings and other designed aspects of our technologies should respect and protect attentional capabilities.” The report calls for paying greater attention “to attention itself as a [sic] inherent human attribute that conditions the flourishing of human interactions and the capabilities to engage in meaningful action.”1

Today, as in Huxley’s time, we have “failed to take into account” our “almost infinite appetite for distractions.”2 The effect of the global attention economy – that is, of many of our digital technologies doing precisely what they are designed to do – is to frustrate and even erode the human will at individual and collective levels, undermining the very assumptions of democracy. They guide us and direct us, but they do not fulfill us or sustain us. These are the “distractions” of a system that is not on our side.

These are our new empires of the mind, and our present relation with them is one of attentional serfdom. Rewiring this relationship is a “political” task in two ways. First, because our media are the lens through which we understand and engage with those matters we have historically understood as “political.” Second, because they are now the lens through which we view everything, including ourselves. “The most complete authority,” Rousseau wrote in A Discourse on Political Economy, “is the kind that penetrates the inner man, and influences his will as much as his actions” (p. 13). This is the kind of authority that our information technologies – these technologies of our attention – now have over us. As a result, we ought to understand them as the ground of first political struggle, the politics behind politics. It is now impossible to achieve any political reform worth having without first reforming the totalistic forces that guide our attention and our lives.

Looking to the future, the trajectory is one of ever greater power of the digital attention economy over our lives. More of our day-to-day experience stands to be mediated and guided by smaller, faster, more ubiquitous, more intelligent, and more engaging entry points into the digital attention economy. As Marc Andreessen, an investor and the author of Mosaic, the first web browser I ever used, said in 2011, “Software is eating the world.”3 In addition, the amount of monetizable attention in our lives is poised to increase substantially if technologies such as driverless vehicles, or economic policies such as Universal Basic Income, come to fruition and increase our amount of available leisure time.

Persuasion may also prove to be the “killer app” for artificial intelligence, or AI. The mantra “AI is the new UI” is informing much of the next generation interface design currently under way (e.g. Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa, or Google Home), and the more that the vision of computing as intelligent, frictionless assistance becomes reality, the more the logic and values of the system will be pushed below the surface of awareness to the automation layer and rendered obscure to users, or to any others who might want to question their design. Already, our most common interactions with some of the most sophisticated AI systems in history occur in contexts of persuasion, and the application of AI in so-called “programmatic” advertising is expected to accelerate.4 One major reason for this is that advertising is where many of the near term business interests lie. Much of the cutting edge of AI research and development now takes place within the walls of companies whose primary business model is advertising – and so, having this existing profit motive to serve, it’s only natural that their first priority would be to apply their innovations toward growing their business. For example, one of the first projects that Google’s DeepMind division put their “AlphaGo” system to work on was enhancing YouTube’s video recommendation algorithm.5 In other words, it now seems the same intelligence behind the system that defeated the human world champion at the game Go is sitting on the other side of your screen and showing you videos that it thinks will keep you using YouTube for as long as possible.

Yet the affinity between advertising and AI extends well beyond the incidental fact that advertising is the current business context in which much leading AI development today occurs. In particular, the problem space of advertising is an extremely good fit for the capabilities of AI: it combines a mind-boggling multiplicity of inputs (e.g. contextual, behavioral, and other user signals) with the laserlike specificity of a clear, binary goal (i.e. typically the purchase, or “conversion,” as it’s often called). Perhaps this is why games have been the other major domain in which artificial intelligence has been tested and innovated. On a conceptual level, training an algorithm to play chess or an Atari 2600 game well is quite similar to training an algorithm to advertise well. Both involve training an agent that interacts with its environment to grapple with an enormous amount of unstructured data and take actions based on that data to maximize expected rewards as represented by a single variable.

Perhaps an intuition about this affinity between advertising and algorithmic automation lay behind that almost mystic comment of McLuhan’s in Understanding Media:

To put the matter abruptly, the advertising industry is a crude attempt to extend the principles of automation to every aspect of society. Ideally, advertising aims at the goal of a programmed harmony among all human impulses and aspirations and endeavors. Using handicraft methods, it stretches out toward the ultimate electronic goal of a collective consciousness. When all production and all consumption are brought into a pre-established harmony with all desire and all effort, then advertising will have liquidated itself by its own success.6

It’s probably not useful, or even possible, to ask what McLuhan got “right” or “wrong” here: in keeping with his style, the observation is best read as a “probe.” Regardless, it seems clear that he’s making two erroneous assumptions about advertising: (1) that the advertising system, or any of its elements, has “harmony” as a goal; and (2) that human desire is a finite quantity merely to be balanced against other system dynamics. On the contrary, since the inception of modern advertising we have seen it continually seek not only to fulfill existing desires, but also to generate new ones; not only to meet people’s needs and demands, but to produce more where none previously existed. McLuhan seems to view advertising as a closed system which, upon reaching a certain threshold of automation, settles into a kind of socioeconomic homeostasis, reaching a plateau of sufficiency via the (apparently unregulated) means of efficiency. Of course, as long as advertising remains aimed at the ends of continual growth, its tools of efficiency are unlikely to optimize for anything like sufficiency or systemic harmony. Similarly, as long as some portion of human life manages to confound advertising’s tools of prediction – which I suggest will always be the case – it is unlikely to be able to optimize for a total systemic harmony. This is a very good thing, because it lets us dispense at the outset with imagined, abstracted visions of “automation” as a generalized type of force (or, even more broadly, “algorithms”), and focus instead on the particular instances of automation that actually present themselves to us, the most advanced implementations of which we currently find on the battlefield of digital advertising.

Looking forward, the technologies of the digital attention economy are also poised to know us ever more intimately, in order to persuade us ever more effectively. Already, over 250 Android mobile device games listen to sounds from users’ environments.7 This listening may one day even extend to our inner environments. In 2015, Facebook filed a patent for detecting emotions, both positive and negative, from computer and smartphone cameras.8 And in April 2017, at the company’s F8 conference, Facebook researcher Regina Dugan, a former head of DARPA (the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency), took the stage to discuss the company’s development of a brain–computer interface.9

Dugan stresses that it’s not about invading your thoughts – an important disclaimer, given the public’s anxiety over privacy violations from social network’s [sic] as large as Facebook. Rather, “this is about decoding the words you’ve already decided to share by sending them to the speech center of your brain,” reads the company’s official announcement. “Think of it like this: You take many photos and choose to share only some of them. Similarly, you have many thoughts and choose to share only some of them.”10

The company refused to say whether they plan to use information collected from the speech center of your brain for advertising purposes.

We face great challenges today across the full stack of human life: at planetary, societal, organizational, and individual levels. Success in surmounting these challenges requires that we give the right sort of attention to the right sort of things. A major function, if not the primary purpose, of information technology should be to advance this end.

Yet for all its informational benefits, the rapid proliferation of digital technologies has compromised attention, in this wide sense, and produced a suite of cognitive-behavioral externalities that we are still only beginning to understand and mitigate. The enveloping of human life by information technologies has resulted in an informational environment whose dynamics the global persuasion industry has quickly come to dominate, and, in a virtually unbounded manner, has harnessed to engineer unprecedented advances in techniques of measurement, testing, automation, and persuasive design. The process continues apace, yet already we find ourselves entrusting enormous portions of our waking lives to technologies that compete with one another to maximize their share of our lives, and, indeed, to grow the stock of life that’s available for them to capture.

This process will not cross any threshold of intolerability that forces us to act. It came on, and continues to evolve, gradually. There will be no voice or light from the sky showing how we’ve become ensconced in a global infrastructure of intelligent persuasion. There will be no scales dropping from eyes, no Toto pulling back the curtain to reveal the would-be wizards pulling their levers. There will be no sudden realization of the gravity and unsustainability of this situation.

Milton Mayer describes how such a gradual process of normalization made even living under the Third Reich feel like no big deal. In his book They Thought They Were Free, he writes:

But the one great shocking occasion, when tens or hundreds or thousands will join with you, never comes. That’s the difficulty. If the last and worst act of the whole regime had come immediately after the first and smallest, thousands, yes, millions would have been sufficiently shocked … But of course this isn’t the way it happens. In between come all the hundreds of little steps, some of them imperceptible, each of them preparing you not to be shocked by the next … And one day, too late, your principles, if you were ever sensible of them, all rush in upon you. The burden of self-deception has grown too heavy, and some minor incident, in my case my little boy, hardly more than a baby, saying “Jewish swine,” collapses it all at once, and you see that everything, everything, has changed and changed completely under your nose … Now you live in a world of hate and fear, and the people who hate and fear do not even know it themselves; when everyone is transformed, no one is transformed … The system itself could not have intended this in the beginning, but in order to sustain itself it was compelled to go all the way.11

No designer ever went into design to make people’s lives worse. I don’t know any software engineers or product managers who want to undermine the assumptions of democracy. I’ve never met a digital marketing manager who aims to make society more outraged and fearful. No one in the digital attention economy wants to be standing in the lights of our attention. Yet the system, in order to sustain itself, has been compelled to go all the way.

This is an intolerable situation. What, then, is to be done? Like Diogenes to Alexander, we urgently need to look up at these well-meaning Alexanders of our time and tell them to “stand out of our light.” Alexander didn’t know he was standing in Diogenes’ light because it didn’t occur to him to ask. He was focused on his offer and his goals, not Diogenes’ goals or what was being obscured by his offer. In the same way, the creators of our digital technologies don’t know that they’re standing in our light because it doesn’t occur to them to ask. They have focused on their goals and their desired effects, rather than our goals or the important “lights” in our lives they may be obscuring.

For us, responding in the right way means treating the design of digital technologies as the ground of first struggle for our freedom and self-determination: as the politics behind politics that shapes our attentional world and directs downstream effects according to its own ends. Yet this new form of power does not go by the usual names, it does not play by the usual rules, and indeed those who wield this power take pains to pretend – despite the strenuous cognitive dissonance of such a claim – that they are not wielding any great political power at all. Yet it is plain that they do.

Ultimately, responding in the right way also means changing the system so that these technologies are, as they already claim to be, on our side. It is an urgent task to bring the dynamics and constraints of the technologies of our attention into alignment with those of our political systems. This requires a sustained effort to reject the forces of attentional serfdom, and to assert and defend our freedom of attention.

A perceptive and critical reader may object here that I’ve given too much airtime to the problems of the digital attention economy and not enough to its benefits. They would be quite right. This is by design. “Why?” they might ask. “Shouldn’t we make an even-handed assessment of these technologies, and fully consider their benefits along with their costs? Shouldn’t we take care not to throw out the baby with the bath water?”

No, we should not. To proceed in that way would grant the premise that it’s acceptable for our technologies to be adversarial against us to begin with. It would serve as implicit agreement that we’ll tolerate design that isn’t on our side, as long as it throws us a few consolation prizes along the way. But adversarial technology is not even worthy of the name “technology.” And I see no reason, either moral or practical, why we should be expected to tolerate it. If anything, I see good reasons for thinking it morally obligatory that we resist and reform it. Silver linings are the consolations of the disempowered, and I refuse to believe that we are in that position relative to our technologies yet.

The reader might also object, “Are any of these dynamics really new at all? Does the digital attention economy really pose a fundamentally new threat to human freedom?” To be sure, incentives to capture and hold people’s attention existed long before digital technologies arose: elements of the attention economy have been present in previous electric media, such as radio and television, and even further back we find in the word “claptrap” a nice eighteenth-century analogue of “clickbait.” It’s also true that our psychological biases get exploited all the time: when a supermarket sets prices that end in .99, when a software company buries a user-hostile stipulation in a subordinate clause on page 97 of their terms-of-service agreement, or when a newspaper requires you to call, rather than email, in order to cancel your subscription. However, these challenges are new: as I have already argued here, this persuasion is far more powerful and prevalent than ever before, its pace of change is faster than ever before, and it’s centralized in the hands of fewer people than ever before.

This is a watershed moment on the trajectory of divesting our media, that is to say our attentional world, of the biases of print media, a trajectory that arguably has been in motion since the telegraph. But this process is more exponential than it is linear, tracking as it does the rate of technology change as a whole. The fact that this can be placed on an existing trajectory means it is more important, not less, to address.

It’s also wrongheaded to say that taking action to reform the digital attention economy would be premature because we lack sufficient clarity about the precise causal relationships between particular designs and particular types of harm. We will never have the sort of “scientific” clarity about the effects of digital media that we have, say, about the effects of the consumption of different drugs. The technology is changing too fast for research to keep up, its users and their contexts are far too diverse to allow anything but the broadest generalizations as conclusions, and the relationships between people and digital technologies are far too complex to make most research of this nature feasible at all. Again, though, the assumption behind calls to “wait and see” is that there’s a scenario in which we’d be willing to accept design that is adversarial against us in the first place. To demand randomized controlled trials, or similarly rigorous modes of research, before setting out to rewire the attention economy is akin to demanding verification that the opposing army marching toward you do, indeed, have bullets in their guns.

Additionally, it’s important to be very clear about what I’m not claiming here. For one, my argument is in no way anti technology or anti commerce. This is no Luddite move. The perspective I take, and the suggestions I will make, are in no way incompatible with making money, nor do they constitute a “brake pedal” on technological innovation. They’re more of a “steering wheel.” Ultimately, this is a project that takes seriously the claim, and helps advance the vision, that technology design can “make the world a better place.”

Also, it’s important to reiterate that I’m not arguing our nonrational psychological biases are in themselves “bad,” nor that exploiting them via design is inherently undesirable. As I wrote earlier, doing so is inevitable, and design can greatly advance users’ interests with these dynamics, when it’s on their side. As Huxley writes in his 1962 novel Island, “we cannot argue ourselves out of our basic irrationality – we can only learn to be irrational in a reasonable way.” Or, as Hegel puts it in Philosophy of Right, “Impulses should be phases of will in a rational system.”1

Nor, of course, am I arguing that digital technologies somehow “rewire” our brains, or otherwise change the way we think on a physiological level. Additionally, I’m not arguing here that the main problem is that we’re being “manipulated” by design. Manipulation is standardly understood as “controlling the content and supply of information” in such a way that the person is not aware of the influence. This seems to me simply another way of describing what most design is.

Neither does my argument require for its moral claims the presence of addiction.2 It’s enough to simply say that when you put people in different environments, they behave differently. There are many ways in which technology can be unethical, and can even deprive us of our freedom, without being “addictive.” Those in the design community and elsewhere who adopt a default stance of defensiveness on these issues often latch on to the conceptual frame of “addiction” in order to avoid having to meaningfully engage with the implications of ethically questionable design. This may occur explicitly or implicitly (the latter often by analogy to other addiction-forming products such as alcohol, cigarettes, or sugary foods). As users, we implicitly buy into these ethically constraining frames when we use phrases such as “digital detox” or “binge watch.” It’s ironic that comparing our technologies to dependency-inducing chemicals would render us less able to hold them ethically accountable for their designs and effects – but this is precisely the case. When we do so, we give up far too much ethical ground: we help to erect a straw man argument that threatens to commandeer the wider debate about the overall alignment of technology design with human goals and values. We must not confuse clinical standards with moral standards. Whether irresistible or not, if our technologies are not on our side, then they have no place in our lives.

It’s also worth noting several pitfalls we should avoid, namely things we must not do in response to the challenges of the attention economy. For one, we must not reply that if someone doesn’t like the choices on technology’s menu, their only option is to “unplug” or “detox.” This is a pessimistic and unsustainable view of technology, and one at odds with its very purpose. We have neither reason nor obligation to accept a relationship with technology that is adversarial in nature.

We must also be vigilant about the risk of slipping into an overly moralistic mode. Metaphors of food, alcohol, or drugs are often (though not always) signals of such overmoralizing. A recent headline in the British newspaper The Independent proclaims, “Giving your Child a Smartphone is Like Giving them a Gram of Cocaine, Says Top Addiction Expert.”3 Oxford researchers Andy Przybylski and Amy Orben penned a reply to that article in The Conversation, in which they wrote,

To fully confirm The Independent’s headline … you would need to give children both a gram of cocaine and a smartphone and then compare the effects … Media reports that compare social media to drug use are ignoring evidence of positive effects, while exaggerating and generalising the evidence of negative effects. This is scaremongering – and it does not promote healthy social media use. We would not liken giving children sweets to giving children drugs, even though having sweets for every meal could have serious health consequences. We should therefore not liken social media to drugs either.4

Similarly, we must reject the impulse to ask users to “just adapt” to distraction: to bear the burdens of impossible self-regulation, to suddenly become superhuman and take on the armies of industrialized persuasion. To do so would be akin to saying, “Thousands of the world’s brightest psychologists, statisticians, and designers are now spending the majority of their waking lives figuring out how to tear down your willpower – so you just need to have more willpower.” We must also reject the related temptation to say, “Oh well, perhaps the next generation will be better adjusted to this attentional warfare by virtue of having been born into it.” That is acquiescence, not engagement.

Additionally, education is necessary – but not sufficient – for transcending this problem. Nor will “media literacy” alone lead us out of this forest. It’s slightly embarrassing to admit this, but back when I was working at Google I actually printed out the Wikipedia article titled “List of Cognitive Biases” and thumb-tacked it on the wall next to my desk. I thought that having it readily accessible might help me be less susceptible to my own cognitive limitations. Needless to say, it didn’t help at all.

Nor can we focus on addressing the negative effects the attention economy has on children to the exclusion of addressing the effects it has on adults. This is often the site of the most unrestrained and counterproductive moralizing. To be sure, there are unique developmental considerations at play when it comes to children. However, we should seek not only to protect the most vulnerable members of society, but also the most vulnerable parts of ourselves.

We also can’t expect companies to self-regulate, or voluntarily refrain from producing the full effects they’re organizationally structured and financially incentivized to produce. Above all, we must not put any stock whatsoever in the notion that advancing “mindfulness” among employees in the technology industry is in any way relevant to or supportive of reforming the dynamics of the digital attention economy. The hope, if not the expectation, that technology design will suddenly come into alignment with human well-being if only enough CEOs and product managers and user experience researchers begin to conceive of it in Eastern religious terms is as dangerous as it is futile. This merely translates the problem into a rhetorical and philosophical frame that is unconnected to the philosophical foundations of Western liberal democracy, and thus is powerless to guide it. The primary function of thinking and speaking in this way is to gesture in the direction of morality while allowing enough conceptual haze and practical ambiguity to permit the impression that one has altered one’s moral course while not actually having done so.

Perhaps most of all, we cannot put the blame for these problems on the designers of the technologies themselves. No one becomes a designer or engineer because they want to make people’s lives worse. Tony Fadell, the founder of the company Nest, has said,

I wake up in cold sweats every so often thinking, what did we bring to the world? … Did we really bring a nuclear bomb with information that can – like we see with fake news – blow up people’s brains and reprogram them? Or did we bring light to people who never had information, who can now be empowered?5

Ultimately, there is no one to blame. At “fault” are more often the emergent dynamics of complex multiagent systems rather than the internal decision-making dynamics of a single individual. As W. Edwards Deming said, “A bad system will beat a good person every time.”6 John Steinbeck captured well the frustration we feel when our moral psychology collides with the hard truth of organizational reality in The Grapes of Wrath, when tenant farmers are evicted by representatives of the bank:

“Sure,” cried the tenant men, “but it’s our land … We were born on it, and we got killed on it, died on it. Even if it’s no good, it’s still ours … That’s what makes ownership, not a paper with numbers on it.”

“We’re sorry. It’s not us. It’s the monster. The bank isn’t like a man.”

“Yes, but the bank is only made of men.”

“No, you’re wrong there – quite wrong there. The bank is something else than men. It happens that every man in a bank hates what the bank does, and yet the bank does it. The bank is something more than men, I tell you. It’s the monster. Men made it, but they can’t control it.”7

The bank isn’t like a man, nor is the technology company, nor is any other brand nor signifier that we might use to represent the boundary conditions of these technologies that shape our lives. There is no one to blame. Knowing this, however, presents us with a choice of two paths. Do we conjure up an image of a “monster” at whom to direct our blame, and take a path which, while psychologically rewarding, is likely to distract from the goal of enacting real change in the real world? Or do we take the second path, and look head-on at the true nature of the system, as messy and psychologically indigestible as it seems to be?

The first path would seem to lead us toward a kind of digital mythology, in which we engage in imagined relationships with personified dynamics of our informational environment, much as the ancients did with their physical and emotional environments.8 Yet if we take autonomy seriously, we cannot help but note that in Steinbeck’s example it is not the displaced farmers, but rather the bankers, who invoke the idea and, we might say, the brand of the “monster.” Similarly, in the realm of digital technology, it is less often users than companies who produce the representations that serve as the primary psychological and emotional points of connection. In fact, these brands and representations may be the elements of technology design over which users have the least amount of control of all. What this path would entail, then, is acquiescence to a mythology that, while psychologically satisfying, would be (and in many cases already is) even more engineered than the products they represent, or than the decisions that those products are designed to induce.

The second path would entail looking the “monster” in the eye, and seeing it for the complex and multifaceted environment that it is. Such an approach would be akin to what the philosopher Luciano Floridi has called “infraethics,” or attention to the infrastructural, “first-order framework of implicit expectations, attitudes, and practices that can facilitate and promote morally good decisions and actions.”9 In a sense, the perspective of infraethics views society itself as a sort of persuasive technology, with a persuasive design goal of maximizing moral actions.

None of this implies, however, that we can simply stand by and expect the attention economy to fix itself. Noble mission statements and inspirational marketing claims can neither produce nor substitute for right design. “Some of the major disasters of mankind,” writes Alfred North Whitehead, “have been produced by the narrowness of men with a good methodology.”10 Similarly, countertechnologies and calls for players in the attention economy to voluntarily reform may serve as bandages that temporarily stem some localized bleeding – but they are not the surgery, the sustainable systemic change, that is ultimately needed. Besides, they implicitly grant that first, fatal assumption we have already roundly rejected: that it’s acceptable for the technologies that shape our thinking and behavior to be in an adversarial relationship against us in the first place.

After acknowledging and avoiding these pitfalls, what route remains? The route in which we take on the task of Herbert Marcuse’s “great refusal,” which Tim Wu describes in The Attention Merchants as being “the protest against unnecessary repression, the struggle for the ultimate form of freedom – ‘to live without anxiety.’”11 The route that remains is the route in which we move urgently to assert and defend our freedom of attention.

How can we begin to assert and defend our freedom of attention? One thing is clear: it would be a sad reimposition of the same technocratic impulse that gave us the attention economy in the first place if we were to assume that there exists a prescribable basket of “solutions” which, if we could only apply them faithfully, might lead us out of this crisis. There are no maps here, only compasses. There are no three-step templates for revolutions.

We can, however, describe the broad outline of our goal: it’s to bring the technologies of our attention onto our side. This means aligning their goals and values with our own. It means creating an environment of incentives for design that leads to the creation of technologies that are aligned with our interests from the outset. It means being clear about what we want our technologies to do for us, as well as expecting that they be clear about what they’re designed to do for us. It means expecting our technologies to proceed from a place of understanding about our own views of who we are, what we’re doing, and where we’re going. It means expecting our technologies and their designers to give attention to, to care about, the right things. If we move in the right direction, then our fundamental understanding of what technology is for, as the philosopher Charles Taylor has put it, “will of itself be limited and enframed by an ethic of caring.”1

Drawing on this broad view of the goal, we can start to identify some vectors of rebellion against our present attentional serfdom. I don’t claim to have all, or even a representative set, of the answers here. Nor is it clear to me whether an accumulation of incremental improvements will be sufficient to change the system; it may be that some more fundamental reboot of it is necessary. Also, I won’t spend much time here talking about who in society bears responsibility for putting each form of attentional rebellion into place: that will vary widely between issues and contexts, and in many cases those answers aren’t even clear yet.

Prior to any task of systemic reform, however, there’s one extremely pressing question that deserves as much of our attention as we’re able to give it. That question is whether there exists a “point of no return” for human attention (in the deep sense of the term as I have used it here) in the face of this adversarial design. That is to say, is there a point at which our essential capacities for life navigation might be so undermined that we would become unable to regain them and bootstrap ourselves back into a place of general competence? In other words, is there a “minimum viable mind” we should take great pains to preserve? If so, it seems a task of the highest priority to understand what that point would be, so that we can ensure we do not cross it. In conceiving of such a threshold – that is, of the minimally necessary capacities worth protecting – we may find a fitting precedent in what Roman law called the “benefit of competence,” or beneficium competentiae. In Rome, when a debtor became insolvent and couldn’t pay his debts, there was a portion of his belongings that couldn’t be taken from him in lieu of payment: property such as his tools, his personal effects, and other items necessary to enable a minimally acceptable standard of living, and potentially even to bootstrap himself back into a position of thriving. This privileged property that couldn’t be confiscated was called his “benefit of competence.” Absent the “benefit of competence,” a Roman debtor might have found himself ruined, financially destitute. In the same way, if there is a “point of no return” for human attention, a “minimum viable mind,” then absent a “benefit of competence” we could also find ourselves ruined, attentionally destitute. And we are not even debtors: we are serfs in the attentional fields of our digital technologies. They are in our debt. And they owe us, at absolute minimum, the benefit of competence.

There are a great number of interventions that could help move the attention economy in the right direction. Any one could fill a whole book. However, four particularly important types I’ll briefly discuss here are: (a) rethinking the nature and purpose of advertising, (b) conceptual and linguistic reengineering, (c) changing the upstream determinants of design, and (d) advancing mechanisms for accountability, transparency, and measurement.

If there’s one necessary condition for meaningful reform of the attention economy, it’s the reassessment of the nature and purpose of advertising. It’s certainly no panacea, as advertising isn’t the only incentive driving the competition for user attention. It is, however, by far the largest and most deeply ingrained one.

What is advertising for in a world of information abundance? As I wrote earlier, the justification for advertising has always been given on the basis of its informational merits, and it has historically functioned within a given medium as the exception to the rule of information delivery: for example, a commercial break on television or a billboard on the side of the road. However, in digital media, advertising now is the rule: it has moved from “underwriting” the content and design goals to “overwriting” them. Ultimately, we have no conception of what advertising is for anymore because we have no coherent definition of what advertising is anymore.2

As a society, we ought to use this state of definitional confusion as the opportunity to help advertising resolve its existential crisis, and to ask what we ultimately want advertising to do for us. We must be particularly vigilant here not to let precedent serve as justification. As Thomas Paine wrote in Common Sense, “a long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right.”3 The presence of a series of organizations dedicated to a task can in no sense be justification for that task. (See, e.g., the tobacco industry.) What forms of attitudinal and behavioral manipulation shall we consider to be acceptable business models? On what basis do we regard the wholesale capture and exploitation of human attention as a natural or desirable thing? To what standards ought we hold the mechanisms of commercial persuasion, knowing full well that they will inevitably be used for political persuasion as well?

A reevaluation of advertising’s raison d’etre must necessarily occur in synchrony with the resuscitation of serious advertising ethics. Advertising ethics has never really guided or restrained the practice of advertising in any meaningful way: it’s been a sleepy, tokenistic undertaking. Why has this been so? In short, because advertisers have found ethics threatening, and ethicists have found advertising boring. (I know, because I have been both.)

In advertising parlance, the phrase “remnant inventory” refers to a publisher’s unpurchased ad placements, that is, the ad slots of de minimis value left over after advertisers have bought all the slots they wanted to buy. In order to fill remnant inventory, publishers sell it at extremely low prices and/or in bulk. One way of viewing the field of advertising ethics is as the “remnant inventory” in the intellectual worlds of advertisers and ethicists alike.

This general disinterest in advertising ethics is doubly surprising in light of the verve that characterized voices critical of the emerging persuasion industry in the early to mid twentieth century. Notably, several of the most prominent early critical voices were veterans of the advertising industry. In 1928, brand advertising luminary Theodore MacManus published an article in the Atlantic Monthly titled “The Nadir of Nothingness” that explained his change of heart about the practice of advertising: it had, he felt, “mistaken the surface silliness for the sane solid substance of an averagely decent human nature.”4 A few years later, in 1934, James Rorty, who had previously worked for the McCann and BBDO advertising agencies, penned a missive titled Our Master’s Voice: Advertising, in which he likewise expressed a sense of dread that advertising was increasingly violating some fundamental human interest:

[Advertising] is never silent, it drowns out all other voices, and it suffers no rebuke, for is it not the voice of America? … It has taught us how to live, what to be afraid of, how to be beautiful, how to be loved, how to be envied, how to be successful … Is it any wonder that the American population tends increasingly to speak, think, feel in terms of this jabberwocky? That the stimuli of art, science, religion are progressively expelled to the periphery of American life to become marginal values, cultivated by marginal people on marginal time?5

The prose of these early advertising critics has a certain tone, well embodied by this passage, that for our twenty-first-century ears is nearly impossible to ignore. It’s a sort of pouring out of oneself, an expression of disbelief and even offense at the perceived aesthetic and moral violations of advertising, and it’s further tinged by a plaintive, interrogative style that reminds us of other Depression-era writers (James Agee in particular comes to mind). But it reminds me of Diogenes, too: when he said he thought the most beautiful thing in the world was “freedom of speech,” the Greek word he used was parrhesia, which doesn’t just mean “saying whatever you want” – it also means speaking boldly, saying it all, “spilling the beans,” pouring out the truth that’s inside you. That’s the sense I get from these early critics of advertising. In addition, there’s a fundamental optimism in the mere fact that serious criticism is being leveled at advertising’s existential foundations at all. Indeed, reading Rorty today requires a conscious effort not to project our own rear-view cynicism on to him.

While perhaps less poetic, later critics of advertising were able to more cleanly circumscribe the boundaries of their criticism. One domain in which neater distinctions emerged was the logistics of advertising: as the industry matured, it advanced in its language and processes. Another domain that soon afforded more precise language was that of psychology. Consider Vance Packard, for instance, whose critique of advertising, The Hidden Persuaders (1957), had the benefit of drawing on two decades of advances in psychology research after Rorty. Packard writes: “The most serious offense many of the depth manipulators commit, it seems to me, is that they try to invade the privacy of our minds. It is this right to privacy in our minds – privacy to be either rational or irrational – that I believe we must strive to protect.”6

Packard and Rorty are frequently cited in the same neighborhood in discussions of early advertising criticism. In fact, the frequency with which they are jointly invoked in contemporary advertising ethics research invites curiosity. Often, it seems as though this is the case not so much for the content of their criticisms, nor for their antecedence, but for their tone: as though to suggest that, if someone were to express today the same degree of unironic concern about the foundational aims of the advertising enterprise as they did, and to do so with as much conviction, it would be too embarrassing, quaint, and optimistic to take seriously. Perhaps Rorty and Packard are also favored for their perceived hyperbolizing, which makes their criticism easier to dismiss. Finally, it seems to me that anchoring discussions about advertising’s fundamental ethical acceptability in the distant past may have a rhetorical value for those who seek to preserve the status quo; in other words, it may serve to imply that any ethical questions about advertising’s fundamental acceptability have long been settled.

My intuition is that the right answers here will involve moving advertising away from attention and towards intention. That is to say, in the desirable scenario advertising would not seek to capture and exploit our mere attention, but rather support our intentions, that is, advance the pursuit of our reflectively endorsed tasks and goals.

Of course, we will not reassess, much less reform, advertising overnight. Until then, we must staunchly defend, and indeed enhance, people’s ability to decline the harvesting of their attention. Right now, the practice currently called “ad blocking” is one of the only ways people have to cast a vote against the attention economy. It’s one of the few tools users have if they want to push back against the perverse design logic that has cannibalized the soul of the web. Some will object and say that ad blocking is “stealing,” but this is nonsense: it’s no more stealing than walking out of the room when the television commercials come on. Others may say it’s not prudent to escalate the “arms race” – but it would be fantastic if there were anything remotely resembling an advertising arms race going on. What we have instead is, on one side, an entire industry spending billions of dollars trying to capture your attention using the most sophisticated computers in the world, and on the other side … your attention. This is more akin to a soldier seeing an army of thousands of tanks and guns advance upon him, and running into a bunker for refuge. It’s not an arms race – it’s a quest for attentional survival.

The right of users to exercise and protect their freedom of attention by blocking any advertising they wish should be absolutely defended. In fact, given the moral and political crisis of the digital attention economy, the relevant ethical question here is not “Is it okay to block ads?” but rather, “Is it a moral obligation?” This is a question for companies, too. Makers of digital technology hardware and software ought to think long and hard about their obligations to their users. I would challenge them to come up with any good reasons why they shouldn’t ship their products with ad blocking enabled by default. Aggressive computational persuasion should be opt-in, not opt-out. The default setting should be one of having control over one’s own attention.

Another important bundle of work involves reengineering the language and concepts of persuasive design. This is necessary not only for talking clearly about the problem, but also for advancing philosophical and ethical work in this area. Deepening the language of “attention” and “distraction” to cover more of the human will has been part of my task here. Concepts from neuroethics may also be of help in advancing the ethics of attention, especially in describing the problem and the nature of its harms, as in, for example, the concepts of “brain privacy” or “cognitive liberty.”7

For companies, a key piece of this task involves reengineering the way we talk about users. Designers and marketers routinely use terms like “eyeballs,” “funnels,” “targeting,” and other words that are perhaps not as humanized as they ought to be. The necessary corrective is to find more human words for human beings. To put a design spin on Wittgenstein’s quote from earlier, we might say that the limits of our language mean the limits of our empathy for users.

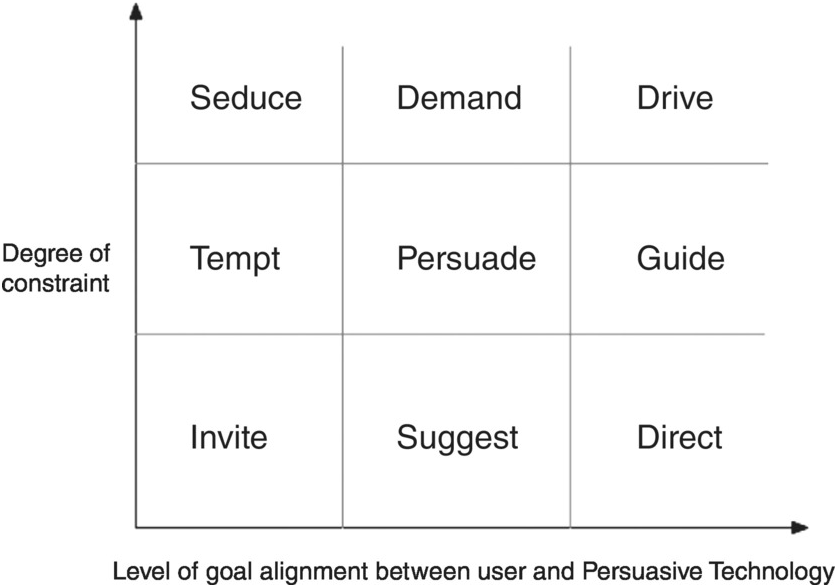

Regarding the language of “persuasion” itself, there is a great deal of clarification, as well as defragmentation across specific contexts of persuasion, that needs to occur. For example, we could map the language of “persuasive” technologies according to certain ethically salient criteria, as seen in the figure below, where the Y axis indicates the level of constraint the design places on the user and the X axis indicates the degree of alignment between the user’s goals and the technology’s goals. Using this framework, then, we could describe a technology with a low level of goal alignment and a high degree of constraint as a “Seductive Technology” – for example, an addictive game that a user wants to stop playing, and afterward regrets having spent time on. However, if its degree of constraint were very low, we could instead call it an “Invitational Technology.” Similarly, a technology that imposes a low degree of constraint on the user and is highly aligned with their goals, such as a GPS device, would be a “Directive Technology.” As its constraints on the user increase, it would become a “Guidance Technology” (e.g. a car’s assisted-parking or autopilot features) and at even higher levels a “Driving Technology” (e.g. a fully autonomous vehicle). This particular framework is an initial, rough example for demonstrating what I mean, but it illustrates some of the ways such a project of linguistic and conceptual defragmentation could go.

Clarifying the language of persuasion will have the added benefit of ensuring that we don’t implicitly anchor the design ethics of attention and persuasion in questions of addiction. It’s understandable why discussion about these issues has already seized on addiction as a core problem: the fundamental challenge we experience in a world of information abundance is a challenge of self-control, and the petty design habits of the attention economy often target our reward system, as I described in Chapter 4.

But there are problems with giving too much focus to the question of addiction. For one, there’s a strict clinical threshold for addiction, but then there’s also the colloquial use of the term, as shorthand for “I use this technology more than I want to.” Without clear definitions, it’s easy for people to talk past one another. In addition, if we give too much focus to addiction there’s the risk that it could implicitly become a default threshold used to determine whether a design is morally problematic or not. But there are many ways a technology can be ethically problematic; addiction is just one. Even designs that create merely compulsive, rather than “addictive,” behaviors can still pose serious ethical problems. We need to be especially vigilant about this sort of ethical scope creep in deployments of the concept of addiction because there are incentives for companies and designers to lean into it: not only does this set the ethical threshold at a high as well as vague level, but it also serves to deflect ethical attention away from deeper ethical questions about goal and value misalignments between the user and the design. In other words, keeping the conversation focused on questions of addiction serves as a convenient distraction from deeper questions about a design’s fundamental purpose.

Interventions with the highest leverage would likely involve changing the upstream determinants of design. This could come from, for instance, the development and adoption of alternate corporate structures that give companies the freedom to balance their financial goals with social good goals, and then offer incentives for companies to adopt these corporate structures. (For instance, Kickstarter recently transitioned to become a “benefit corporation,” or B-corp. The writer and Columbia professor Tim Wu has recently called in the New York Times for Facebook to do the same.)8 Similarly, investors could create a funding environment that disincentivizes startup companies from pursuing business models that involve the mere capture and exploitation of user attention. In addition, companies could be expected (or compelled, if necessary) to give users a choice about how to “pay” for content online – that is, with their money or with their attention.

Many of these upstream determinants of design may be addressed by changes in the policy environment. Policymakers have a crucial role to play in responding to the crisis of the digital attention economy. To be sure, they have several headwinds working against them: the internet’s global nature means local policies can only reach so far, and the rapid pace of technological change tends to result in reactive, rather than proactive, policymaking. But one of the strongest headwinds for policy is the persistence of informational, rather than attentional, emphases. Most digital media policy still arises out of assumptions that fail to sufficiently account for Herbert Simon’s observation about how information abundance produces attention scarcity. Suggestions that platforms be required to tag “fake news,” for example, would be futile, an endless game of epistemic whack-a-mole. Initial research has already indicated as much.9 Similarly, in the European Union, website owners must obtain consent from each user whose browsing behavior they wish to measure via the use of tracking “cookies.” This law is intended to protect user privacy and increase transparency of data collection, both of which are laudable aims when it comes to the ethics of information management. However, from the perspective of attention management, the law burdens users with, say, thirty more decisions per day (assuming they access thirty websites per day) about whether or not to consent to being “cookied” by a site they may have never visited before, and therefore don’t know whether or not they can trust. This amounts to a nontrivial strain on their cognitive load that far outweighs any benefit of giving their “consent” to have their browsing behavior measured. I place the word “consent” in quotes here because what inevitably happens is that the “cookie consent” notifications that websites show to users simply become designed to maximize compliance: website owners simply treat the request for “consent” as one more persuasive interaction, and deploy the same methods of measurement and experimentation they use to optimize their advertising-oriented design in order to manufacture users’ consent.

However, governmental bodies are uniquely positioned to host conversations about the ways new technological affordances relate to the moral and political underpinnings of society, as well as to advance existential questions about the nature and purpose of societal institutions. And, importantly, they are equipped to foster these conversations in a context that can, in principle, inform and catalyze corrective action. We can find some reasons to be at least cautiously optimistic in precedents for legal protection of attention enacted in predigital media. Consider, for instance, anti-spam legislation and “do not call” registries, which aim to forestall unwanted intrusions into people’s private spaces. While protections of this nature generally seek to protect “attention” in the narrow sense – in other words, to mitigate annoyance or momentary distractions – they can nonetheless serve as doorways to protecting the deeper forms of “attention” that I have discussed here.

What can policy do in the near term that would be high-leverage? Develop and enforce regulations and/or standards about the transparency of persuasive design goals in digital media. Set standards for the measurement of certain sorts of attentional harm – that is, quantify their “pollution” of the inner environment – and require that digital media companies measure their effects on these metrics and report on them periodically to the public. Perhaps even charge companies something like carbon offsets if they go over a certain amount – we might call them “attention offsets.” Also worth exploring are possibilities for digital media platforms that would play a role analogous to the role public broadcasting has played in television and radio.

Advancing accountability, transparency, and measurement in design is also key. For one, having transparency of persuasive design goals is essential for verifying that our trust in the creators of our technologies is well placed. So far, we’ve largely demanded transparency about the ways technologies manage our information, and comparatively less about the ways they manage our attention. This has foregrounded issues such as user privacy and consent, issues which, while important, have distracted us from demanding transparency about the design logic – the ultimate why – that drives the products and services we use. The practical implication of this is that we’ve had minimal and shaky bases for trust. “Whatever man you meet,” advised the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius in his Meditations, “say to yourself at once: ‘what are the principles this man entertains as goods and ills?’”10 This is good advice not only upon encountering persuasive people, but persuasive technologies as well. What is Facebook’s persuasive goal for me? On what basis does YouTube suggest that I watch one video and not another? What metric does Twitter aim to maximize with my time use? Why did Amazon build Alexa, after all? Do the goals my trusted systems have for me align with the goals I have for myself? There’s nothing wrong with trusting the people behind our technologies, nor do we need perfect knowledge of their motivations to justifiably do so. Trust always involves taking some risk. Rather, our aim should be to find a way, as the Russian maxim says, to “trust, but verify.”

Equipping designers, engineers, and businesspeople with effective “commitment devices” may also be of use. One common example is that of professional oaths. The oath occupies a unique place in contemporary society: it’s weightier than a promise, more universal than a pledge, and more individualized than a creed. Oaths express and remind us of common ethical standards, provide opportunities for making public commitments to particular values, and enable accountability for action. Among the oaths that are not legally binding, the best known is probably the Hippocratic Oath, some version of which is commonly recited by doctors when they graduate from medical school. Karl Popper (in 1970)11 and Joseph Rotblat (in 1995),12 among others, have proposed similar oaths for practitioners of science and engineering, and in recent years proposals for oaths specific to digital technology design have emerged as well.13 So far, none of these oaths have enjoyed broad uptake. The reasons for this likely include the voluntary nature of such oaths, as well as the inherent challenge of agreeing on and articulating common values in pluralistic societies. But the more significant headwinds here may originate in the decontextualized ways in which these proposals have been made. If a commitment device is to be adopted by a group, it must carry meaning for that group. If that meaning doesn’t include some sort of social meaning, then achieving adoption of the commitment device is likely to be extremely challenging. Most oaths in wide use today depend on some social structure below the level of the profession as a whole to provide this social meaning. For instance, mere value alignment among doctors about the life-saving goals of medicine would not suffice to achieve continued, widespread recitations of the Hippocratic Oath. The essential infrastructure for this habit lies in the social structures and traditions of educational institutions, especially their graduation ceremonies. Without a similar social infrastructure to enable and perpetuate use of a “Designer’s Oath,” significant uptake seems doubtful.

It could be argued that a “Designer’s Oath” is a project in search of a need, that none yet exists because it would bring no new value. Indeed, other professions and practices seem to have gotten along perfectly fine without common oaths to bind or guide them. There is no “Teacher’s Oath,” for example; no “Fireman’s Oath,” no “Carpenter’s Oath.” It could be suggested that “design” is a level of abstraction too broad for such an oath because different domains of design, whether architecture or software engineering or advertising, face different challenges and may prioritize different values. In technology design, the closest analogue to a widely adopted “Designer’s Oath” we have seen is probably the voluntary ethical commitments that have been made at the organizational level, such as company mottos, slogans, or mission statements. For example, in Google’s informal motto, “do no evil,” we can hear echoes of that Hippocratic maxim, primum non nocere (“first, do no harm”).14

But primum non nocere does not, in fact, appear in any version of the Hippocratic Oath. The widespread belief otherwise provides us with an important signal about the perceived versus the actual value of oaths in general. A significant portion of their value comes not from their content but from their mere existence: from the societal recognition that a particular practice or profession is oath-worthy, that it has a significant impact on people’s lives such that some explicit ethical standard has been articulated to which conduct within the field can be held.

Assuming we could address these wider challenges that limit the uptake of a “Designer’s Oath” within society, what form should such an oath take? In this space, I can only gesture toward a few of the main questions – let alone arrive at any clear answers. One of the key questions is how explicitly such an oath should draw on the example of the Hippocratic Oath. In my view, the precedent seems appropriate to the extent that using the metaphor of medicine to talk about design can help people better understand the seriousness of design. Comparing design to medicine is a useful way of conveying the depth of what is ultimately at stake. Medicine is also an appropriate metaphor because, like design, it’s a profession rather than an organization or institution, which makes it an appropriate level of society at which to draw a comparison.

However, one limitation of drawing on medicine as a rough guide to this terrain pertains to the logistics of when and where (and by whom) a “Designer’s Oath” would be taken. Medical training is highly systematized, and provides an organizational context for taking such an oath. A technology designer, by contrast, may have never had any formal design education – and even those who have, may have never taken a design ethics class. Even for those who do take design ethics classes (which are often electives), there is unlikely to be a moment in them when, as in a graduation ceremony, it would not feel extremely awkward to take an oath. Of course, this assumes that an educational setting is the appropriate context for such an oath to begin with. Should we instead look to companies to lead the way? If so, this would raise the further question about who should be expected, and not expected, to take the oath (e.g. front-end vs. back-end designers, hands-on designers vs. design researchers, senior vs. junior designers, etc.). Finally, there’s also the question of how such an oath should be written, especially in the digital age. Should it be a “wiki”-style oath, the product of numerous contributors’ input and discussion? Or is such a “crowd-sourced” approach, while an appropriate way to converge on the provisional truth of a fact (as in Wikipedia), an undesirable way to develop a clear-minded expression of a moral ideal? In any event, we should expect that any “Designer’s Oath” receiving wide adoption would continually be iterated and adapted in response to local contexts and new advances in ethical thought, as has been the case with the Hippocratic Oath over many centuries.

As regards the substance of a “Designer’s Oath” – an initial “alpha” version that can serve as a “minimum viable product” to build upon – I suggest that a good approach would look something like the following (albeit far more poetic and memorable than this):

As someone who shapes the lives of others, I promise to:

Care genuinely about their success;

Understand their intentions, goals, and values as completely as possible;

Align my projects and actions with their intentions, goals, and values;

Respect their dignity, attention, and freedom, and never use their own

weaknesses against them;

Measure the full effect of my projects on their lives, and not just those effects that are important to me;

Communicate clearly, honestly, and frequently my intentions and methods; and

Promote their ability to direct their own lives by encouraging reflection on their own values, goals, and intentions.

I won’t attempt here to justify each element I’ve included in this “alpha” version of the oath, but will only note that: (a) it assumes a patient-centered, rather than an agent-centered, perspective; (b) in keeping with the theme of this inquiry, it emphasizes ethical questions related to the management of attention (broadly construed) rather than the management of information; (c) it explicitly disallows design that is consciously adversarial in nature (i.e. having aims contrary to those of the user), which includes a great deal of design currently operative in the attention economy; (d) it goes beyond questions of respect or dignity to include an expectation of care on the part of the designer; and (e) it views measurement as a key way of operationalizing that care in the context of digital technology design (as I will further discuss below).

Measurement is also key. In general, our goal in advancing measurement should be to measure what we value, rather than valuing what we already measure. Ethical discussions about digital advertising often assume that limiting user measurement is axiomatically desirable due to considerations such as privacy or data protection. These are indeed important ethical considerations, and if we conceive of the user–technology interaction in informational terms then such conclusions may very well follow. Yet if we take an attention-centric perspective, as I have described above, there are ways in which limiting user measurement may complicate the ethics of a situation, and possibly even actively hinder it.

Greater measurement (of the right things) is in principle a good thing. Measurement is the primary means designers and advertisers have of attending to specific users, and as such it can serve as the ground on which conversations, and if necessary interventions, pertaining to the responsibilities of designers may take place.

One key ethical question we should be asking with respect to user measurement is not merely “Is it ethical to collect more information about a user?” (though of course in some situations that is the relevant question), but rather, “What information about the user are we not measuring, that we have a moral obligation to measure?”

What are the right things to measure? One is potential vulnerabilities on the part of users. This includes not only signals that a user might be part of some vulnerable group (e.g. children or the mentally disabled), but also signals that a user might have particularly vulnerable mechanisms. (For example, a user may be more susceptible to stimuli that draw them into addictive or akratic behavior.) If we deem it appropriate to regulate advertising to children, it is worth asking why we should not similarly regulate advertising that is targeted to “the child within us,” so to speak.

Another major area where measurement ought to be advanced is in the understanding of user intent. The way in which search queries function as signals of user intent, for instance, has played a major role in the success of search engine advertising. Broadly, signals of intent can be measured in forward-looking forms (e.g. explicitly expressed in search queries or inferred from user behavior) as well as backward-looking forms (e.g. measures of regret, such as web page “bounce rates”). However, the horizon of this measurement of intent should not stop at low-level tasks: it should include higher and longer-term user goals as well. The creators of technologies often justify their design decisions by saying they’re “giving users what they want.” However, this may not be the same as giving users “what they want to want.” To do that, they need to measure users’ higher goals.

Other things worth measuring include the negative effects technologies might have in users’ lives – for example, distraction or decreases in their overall well-being – as well as an overall view of the net benefit that the product is bringing to users’ lives (as with Couchsurfing.com’s “net orchestrated conviviality” metric).15 One way to begin doing this is by “measuring the mission” – beginning to operationalize in metrics the company’s mission statement or purpose for existing, which is something nearly every company has but which hardly any company actually measures their success toward. Finally, companies can measure the broader effects of their advertising efforts on users – not merely those effects that pertain to the advertiser’s persuasive goals.

Ultimately, none of these interventions – greater transparency of persuasive design goals, the development of new commitment devices, or advancements in measurement – is enough to create deep, lasting change in the absence of new mechanisms to make users’ voices heard in the design process. If we construe the fundamental problem of the attentional economy in terms of attentional labor – that as users we’re not getting sufficient value for our attentional labor, and the conditions of that labor are unacceptable – we could conceive of the necessary corrective as a sort of “labor union” for the workers of the attention economy, which is to say, all of us. Or, we might construe our attentional expenditure as the payment of an “attention tax,” in which case we currently find ourselves subject to attentional taxation without representation. But however we conceive the nature of the political challenge, its corrective must ultimately consist of user representation in the design process. Token inclusion is insufficient: users need to have a real say in the design, and real power to effect change. At present, users may have partial representation in design decisions by way of market or user experience research. However, the horizon of concern for such work typically terminates at the question of business value; it rarely raises substantive political or ethical considerations, and never functions as anything remotely like an externally transparent accountability mechanism. Of course, none of this should surprise us at all, because it’s exactly what the system so far has been designed to do.

I’m often asked whether I’m optimistic or pessimistic about the potential for reform of the digital attention economy. My answer is that I’m neither. The question assumes the relevant task before us is one of prediction rather than action. But that perspective removes our agency; it’s too passive.

Some might argue that aiming for reform of the attention economy in the way I’ve described here is too ambitious, too idealistic, too utopian. I don’t think so – at least, it’s no more ambitious, idealistic, or utopian than democracy itself. Finally, some might say “it’s too late” to do any or all of this. At that, I can only shake my head and laugh. Digital technology has only just gotten started. Consider that it took us 1.4 million years to put a handle on the stone hand axe. The web, by contrast, is fewer than 10,000 days old.

O for a Muse of fire, that would ascend / The brightest heaven of invention

Let me tell you about two of my favorite YouTube videos. In the first, a father and his family are in their backyard celebrating his birthday. One person hands him his present, and, seeing that someone has begun video-recording the moment, he senses there’s something special about it. He takes his time opening the gift, cracking small jokes along the way. He removes the wrapping paper to find a box containing a pair of sunglasses. But these sunglasses aren’t meant for blocking out the sunlight: they’re made to let people like him, the colorblind, see the colors of the world. He reads the details on the back of the box longer than is necessary, drawing out the process as though trying to delay, as though preparing himself for an experience he knows will overwhelm him. He takes the black glasses out, holds them up, and silently examines them from all directions. Then someone off-camera exclaims, “Put them on!” He does, then immediately looks away from the camera. He’s trying to retain his composure, to take this in his stride. But he can’t help jolting between everyday items now, because to him they’ve all been transfigured. He’s seeing for the first time the greenness of the grass, the blueness of the sky, the redness of his wife’s poinsettias and her lips, finally, and the full brownness of the kids’ hair and the flush peach paleness of their faces as they smile and come to him and hug him, his eyes filling with water as he keeps repeating over and over, “Oh, wow. Oh, man.”

The second video opens with a top-down view of Earth, over which the International Space Station is hurtling. A piano plays as we fade into the ISS’s observation dome, the Cupola, where a mustached man, the Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield, floats and stares down at Earth, seemingly lost in reflection. The piano downbeats on a minor chord as he turns to the camera and sings the opening line of David Bowie’s song Space Oddity: “Ground control to Major Tom.” He continues singing as he floats down a corridor of wires and lens flares. Then a guitar appears in his hands as laptops float around him, seeming to balance on their wires like cobras. He sings, “Lock your Soyuz hatch and put your helmet on.” (In Bowie’s version the line is “Take your protein pills and put your helmet on”; Soyuz is the rocket that today takes astronauts to the ISS.) We see Hadfield singing in his padded, closet-sized quarters, singing as he floats through other shafts and rooms, returning time and again to the Cupola, bright with the light of Earth. He comes to the bridge: “Here am I floating in my tin can / Last glimpse of the world / Planet Earth is blue, and there’s nothing left to do.” (The original line, in Bowie’s version, is “there’s nothing I can do.”) I don’t remember when astronauts started to be able to use the internet in space, but in any case this video made me realize that the World Wide Web isn’t just world-wide anymore.

At its best, technology opens our doors of perception, inspires awe and wonder in us, and creates sympathy between us. In the 1960s, some people in San Francisco started walking around wearing a button that read, “Why haven’t we seen a photo of the earth from space yet?” They realized that this shift in perception – what’s sometimes called the “overview effect” – would occasion a shift in consciousness. They were right: when the first photo of Earth became widely available, it turned the ground of nature into the figure, and enabled the environmental movement to occur. It allowed us all to have the perspective of astronauts, who were up in space coining new terms like “earthlight” and “earthrise” from the surface of the Moon. (Though I can’t seem to find the reference, I think it might have been the comedian Norm MacDonald who said, “It must have been weird to be the first people ever to say, ‘Where’s the earth?’ ‘Oh, there it is.’”)

What’s needed now is a similar shift ? an overview effect, finding the earthlight ? for our inner environment. Who knows, maybe space exploration will play a role this time, too. After all, it did go far in giving us a common goal, a common purpose, a common story during a previous turbulent time. As the mythologian Joseph Campbell said, “The modern hero deed must be that of questing to bring to light again the lost Atlantis of the coordinated soul.”1 This is true at both individual and collective levels.

In order to rise to this challenge, we have to lean into the experiences of awe and wonder. (Interestingly, these emotions, like outrage, also tend to go “viral” in the attention economy.) We have to demand that these forces to which our attention is now subject start standing out of our light. This means rejecting the present regime of attentional serfdom. It means rejecting the idea that we’re powerless, that our angry impulses must control us, that our suffering must define us, or that we ought to wallow in guilt for having let things get this bad. It means rejecting novelty for novelty’s sake and disruption for disruption’s sake. It means rejecting lethargy, fatalism, and narratives of us versus them. It means using our transgressions to advance the good. This is not utopianism. This is imagination. And, as anyone with the slightest bit of imagination knows, “imaginary” is not the opposite of “real.”