Contemporary organizations have increasingly realized the benefits of a sustainable workforce due to the positive relationship with productivity and organizational effectiveness, and the negative relationship with turnover (Chernyak-Hai, Bareket-Bojmel & Margalit, Reference Chernyak-Hai, Bareket-Bojmel and Margalit2023; Eisenberger & Stinglhamber, Reference Eisenberger and Stinglhamber2011). Research shows that when employees perceive their organization as one that values their contributions and cares about their well-being, they develop a general perception of organization support (known as perceived organizational support [POS]; Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock & Wen, Reference Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock and Wen2020). POS, in turn, leads employees to experience a positive orientation toward the organization, higher psychological well-being, and better performance (Kurtessis et al., Reference Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart and Adis2017; Rhoades & Eisenberger, Reference Rhoades and Eisenberger2002). Organizational support theory (OST) explains these relationships, first, as a process of social exchange, where the employee feels obliged to show gratitude and reciprocate the organization’s supportive actions (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock and Wen2020; Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski & Rhoades, Reference Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski and Rhoades2002). Second, as a process of self-enhancement, where POS contributes to favorable employee attitudes because it fulfills the employee’s need for approval, esteem and emotional support (Armeli, Eisenberger, Fasolo & Lynch, Reference Armeli, Eisenberger, Fasolo and Lynch1998).

In general, empirical findings provide evidence for OST (Côté, Lauzier & Stinglhamber, Reference Côté, Lauzier and Stinglhamber2021; Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock and Wen2020; Kurtessis et al., Reference Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart and Adis2017). However, due to the almost exclusive focus of investigations on POS the individual-level, several scholars have recently called for more research at the unit- and organizational levels (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock and Wen2020; Jolly, Kong & Kim, Reference Jolly, Kong and Kim2021; Kim, Eisenberger, Takeuchi & Baik, Reference Kim, Eisenberger, Takeuchi and Baik2022). In particular, few studies have examined the unit-level antecedents and outcomes of unit-level POS (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock and Wen2020; Kurtessis et al., Reference Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart and Adis2017). Moreover, theory and empirical evidence suggest that employees’ perceptions are not in a vacuum; employees’ perceptions (and their relationships with important criteria) can be shaped and influenced by their units’ characteristics and shared perceptions (Festinger, Reference Festinger1954; Ward, Beal, Zyphur, Zhang & Bobko, Reference Ward, Beal, Zyphur, Zhang and Bobko2022; Wemken, Janurek, Junker & Häusser, Reference Wemken, Janurek, Junker and Häusser2021). In explaining why these unit-level contexts matter, two mechanisms are especially relevant: signaling theory and social comparison theory (Festinger, Reference Festinger1954). Through signaling processes, employees use the actions and communications of leaders and organizational agents as cues about the organization’s support for their unit (Spence, Reference Spence1978). Social comparison processes further shape how employees interpret these cues by using their coworkers’ shared perceptions as a natural reference point when evaluating their own treatment (Festinger, Reference Festinger1954; Greenberg, Ashton-James & Ashkanasy, Reference Greenberg, Ashton-James and Ashkanasy2007). In terms of POS, this means that employees tend to compare their own perceptions of organizational support to their units’ POS levels. This creates a frame of reference that influence relevant work outcomes, such as employee job satisfaction (i.e., a positive internal state resulting from a favorable affective and cognitive appraisal of one’s job; Locke, Reference Locke and Dunnette1976).

The scarcity of research about POS at the unit-level is unfortunate for theoretical and practical reasons. First, from a theoretical standpoint, we do yet not understand the contextual contingencies that constrain or amplify the relationship between individual POS and employees’ work outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction; Kurtessis et al., Reference Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart and Adis2017). As multilevel organizational theory posits (Kozlowski & Klein, Reference Kozlowski and Klein2000), unit-level factors (such as unit-POS; i.e., the shared perception among work-unit members that their organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being) may contribute to shaping individual-level relationships (e.g., POS and job satisfaction). More specifically, unit-POS can act as a contextual contingency (a moderator) because employees receive and perceive organizational support differently, depending on the unit to which they belong (Erdogan & Enders, Reference Erdogan and Enders2007; Shanock & Eisenberger, Reference Shanock and Eisenberger2006). Understanding these moderated relationships is crucial because (a) it allows us to understand the conditions under which well-established individual-level relationships in the literature (e.g., employee POS and job satisfaction) change in magnitude depending on contextual factors (i.e., unit-level POS), and (b) it extends POS theory across levels. Second, if unit-level POS is an important moderator of the individual-level relationship between employee POS-job satisfaction, then uncovering its nomological network at the unit level is an important step toward improving our understanding of unit-level POS as a key scientific construct. Finally, from a practical perspective, research about unit-level POS can suggest ways in which unit leaders and managers should tailor their acts and means to enhance the positive influences of POS depending on the perceptions of organizational support in the unit and the relative levels of support perceived by the individual.

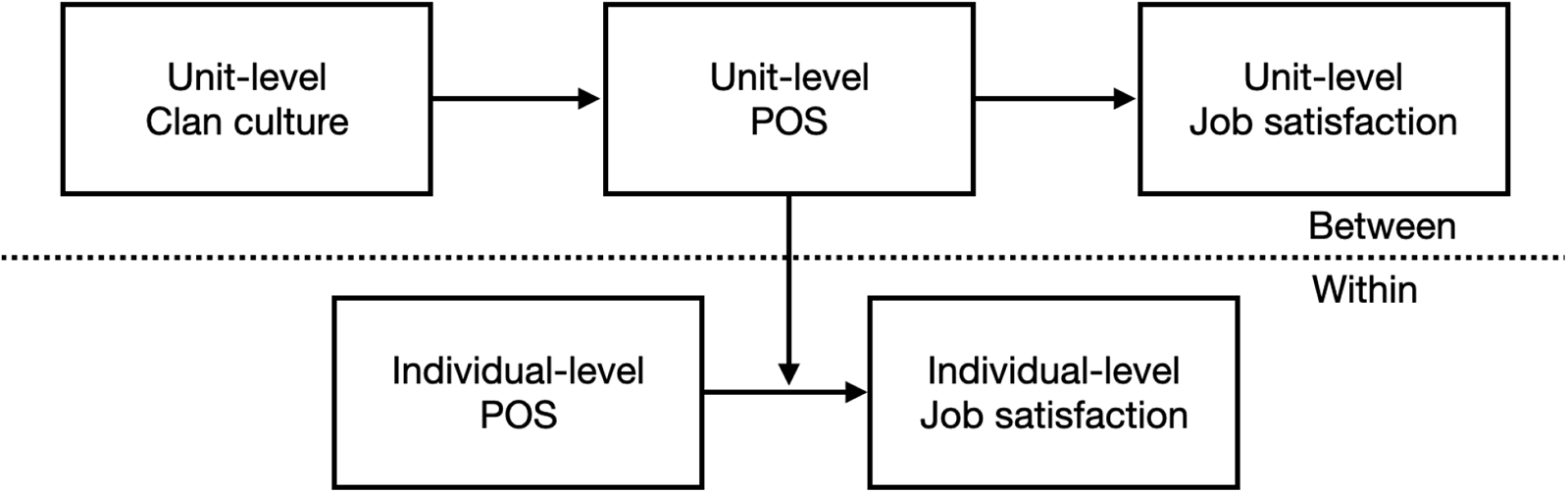

Therefore, the first aim of this study is to examine the moderator influence of unit-level POS on the individual-level relationship between employee POS and job satisfaction. Moreover, to contribute to clarifying the nomological network of unit POS, we investigate unit clan culture as a potential antecedent, and unit job satisfaction (i.e., a shared favorable affective and cognitive appraisal of the job among work-unit members) as a potential outcome, of unit POS. We posit that unit clan values (i.e., collaboration, attachment, and support) signal to work units that their employees are cared for and supported by the organization, which in turn elicit the process of social exchange and self-enhancement that promotes unit-level job satisfaction (Armeli et al., Reference Armeli, Eisenberger, Fasolo and Lynch1998; Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock and Wen2020; Gouldner, Reference Gouldner1960). Our multilevel research model is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The proposed research model.

We aim to provide three contributions to the literature. First, we expand the understanding of the relationship between employee POS and job satisfaction by identifying a relevant boundary condition (unit POS; Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock and Wen2020; Kurtessis et al., Reference Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart and Adis2017). By adopting a multilevel perspective, our study helps understand how and why unit POS shapes the relationship between employee POS and job satisfaction, acting as a cross-level moderator. Previous studies (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Beal, Zyphur, Zhang and Bobko2022) have shown similar cross-level interactions but they focused on other climate facets (diversity climate) and outcomes (employee trust perceptions). As far as we know, this is the first study that examines how and why unit POS moderates the individual level relationship between individual POS and job satisfaction. Second, we identify unit clan culture as a correlate of unit POS. Previous research that has examined organizational levels of POS (e.g., Kim et al., Reference Kim, Eisenberger, Takeuchi and Baik2022) has overlooked how POS may differ due to antecedents such as work-unit culture. With our study, we contribute to improving our knowledge about the nomological network of unit POS. Third, by adopting a multilevel perspective, we contribute to developing POS theory across levels, moving it ‘beyond the individual-level POS considered in almost all POS research’ (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock and Wen2020, p. 117). Our study offers ideas and empirical evidence that can help future research and theoretical models to embrace a multilevel perspective. Doing so will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the role that POS plays in work units.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses

A multilevel conceptualization of POS

To clarify the theoretical foundation of our multilevel model, we articulate how several complementary theories jointly explain why POS emerges, how it influences employee attitudes, and why unit-level context shapes these processes. As mentioned previously, our approach is anchored in OST and is the primary theory underlying our proposed model. OST specifies the mechanisms through which employees develop perceptions on whether their organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock and Wen2020). According to OST, POS emerges from employees’ interpretations of organizational actions and policies that convey care, fairness, recognition, and investment in their socioemotional needs (i.e., clan culture values; Eisenberger & Stinglhamber, Reference Eisenberger and Stinglhamber2011). The relationship between POS and positive employee attitudes – such as job satisfaction – is primarily explained through social exchange theory (SET). SET proposes that supportive organizational treatment generates felt obligations and norms of reciprocity (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Reference Cropanzano and Mitchell2005; Gouldner, Reference Gouldner1960). When employees perceive strong organizational support, they tend to reciprocate through favorable attitudes and behaviors, which often manifest as higher job satisfaction. SET therefore clarifies why POS leads to positive employee outcomes.

Because employees work in social environments rather than isolation, individual perceptions of support are shaped by how coworkers interpret and respond to organizational actions. Two mechanisms help explain this contextual influence. First, Signaling Theory contends that employees use observable organizational practices and leader behaviors as cues regarding the organization’s intentions and priorities (Spence, Reference Spence1978). Such signals are particularly influential when expectations are ambiguous, prompting employees to rely on local cues to understand the organization’s stance toward their unit. Second, Social Comparison Theory explains how employees evaluate their own experiences relative to those of coworkers (Festinger, Reference Festinger1954; Greenberg et al., Reference Greenberg, Ashton-James and Ashkanasy2007). Employees draw on the shared perceptions within their work unit as a proximal reference point, which shapes how strongly their own POS influences attitudes such as job satisfaction. In combination, signaling and social comparison mechanisms clarify how unit-level characteristics shape the connection between individual POS and employee outcomes.

Together, these theories provide a coherent multilevel foundation. OST explains why POS emerges through clan culture values, SET explains why POS matters for job satisfaction, and signaling and social comparison theories explain how unit-level contexts shape these relationships. Conceptualizing POS at multiple levels is thus important to fully understand the role this construct play in work units. To further illustrate this, we present a hypothetical case of two employees, Sarah and Waheed, from different units within the same organization. Consider Sarah, a sales employee, who scores a 4 on a 1–5 scale of POS (where 5 signifies maximal POS). She firmly believes that her opinions matter that mistakes are forgiven, and that assistance is readily available if she encounters any work-related issues. However, Sarah’s score is below her unit’s average (unit POS) score of 4.8. Suppose also that Sarah’s scores is the lowest in her unit. Similarly, Waheed, an accountant, also report a score of 4 on the same scale. However, in Waheed’s unit, the average POS score is 2. Suppose also that Waheed’s score is the highest in his unit. Sarah and Waheed have the same raw individual score in POS. However, because they have different relative scores regarding their respective units’ average scores, it is likely that their experiences are qualitatively different (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Beal, Zyphur, Zhang and Bobko2022). To account for these differences, the within- (individual-level) and between- (unit-level) components of POS must be considered. The within-component shows the relative standing of employees within their respective units, considering the unit average as the reference point. The between-component reflects differences between units’ average scores. As we explain later, we posit that the individual-level relationship between the within-components of POS and job satisfaction depends on units’ average POS (i.e., the between-component of POS). Multilevel Structural Equation Modeling (ML-SEM) allows researchers to decompose variables that vary at multiple levels, into their within- and between-components and model the relationships involving these components at different levels. Therefore, conceptualizing POS at multiple levels (individual and unit) using the appropriate analytical methods allows us to obtain a rich and fine-grained understanding of its role in work units.

Individual-level POS & job satisfaction

Our model assumes a positive relationship between individual-level POS and job satisfaction (that is, the within components of the two variables). This expectation follows directly from OST, which explains why supportive organizational treatment should translate into more favorable job attitudes through complementary mechanisms grounded in social exchange and self-enhancement/need fulfillment (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Reference Cropanzano and Mitchell2005; Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock and Wen2020; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Eisenberger, Takeuchi and Baik2022). From a SET perspective, employees interpret discretionary organizational actions – such as providing resources, fairness, developmental opportunities, and involvement – as signals that the organization values them and is committed to their well-being (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock and Wen2020; Judge, Zhang & Glerum, Reference Judge, Zhang and Glerum2020; Spector, Reference Spector2022). Such signals foster an obligation to reciprocate with positive attitudes toward the organization and one’s job, including higher job satisfaction (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock and Wen2020; Gouldner, Reference Gouldner1960). In parallel, OST proposes that POS contributes to satisfaction by meeting socioemotional needs for esteem, approval, belongingness and emotional support, which are central predictors of evaluative work attitudes (Deci, Olafsen & Ryan, Reference Deci, Olafsen and Ryan2017; Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock and Wen2020).

Several studies have found support for the theoretical underpinnings of OST (SET and self-enhancement) and the relationship between POS and job satisfaction is well-established (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock and Wen2020; Kurtessis et al., Reference Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart and Adis2017; Rhoades & Eisenberger, Reference Rhoades and Eisenberger2002). In Kurtessis et al. (Reference Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart and Adis2017) meta-analysis, the relationship between employee POS and job satisfaction was examined across 154 previous studies and a total sample of 64,303 employees. Their results showed a moderately strong correlation between POS and job satisfaction (r = .57). Beyond meta-analytic evidence, primary studies across diverse occupations and national contexts consistently replicate this association, supporting the generalizability of OST’s predictions (Larsman, Pousette & Törner, Reference Larsman, Pousette and Törner2024; Maan, Abid, Butt, Ashfaq & Ahmed, Reference Maan, Abid, Butt, Ashfaq and Ahmed2020; Zeng, Zhang, Chen, Liu & Wu, Reference Zeng, Zhang, Chen, Liu and Wu2020). Thus, based on strong theoretical arguments and empirical evidence, we expect that POS will be positively related to job satisfaction at the individual level.

The moderator role of unit-level POS

We posit that the individual-level relationship between POS and job satisfaction is moderated by unit-level POS (that is, the between component of POS). Employees do not think and act in a vacuum (Festinger, Reference Festinger1954; Lerner & Tetlock, Reference Lerner and Tetlock1999), and organizations can be more (or less) supportive of some units within the same organization (Eisenberger & Stinglhamber, Reference Eisenberger and Stinglhamber2011; Kozlowski & Klein, Reference Kozlowski and Klein2000). For instance, in times in which talent is scarce for some positions, the HR department may receive more support from the organization to retain and attract talent. Thus, within a given organization, there may be between-unit variability in unit-level POS.

Within units, POS perceptions tend to become shared among unit members for several reasons. First, unit members share the same proximal organizational representative: the unit leader or manager. S/He is a channel through which the organization provides support (i.e., information, resources, and care) to unit members (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski and Rhoades2002; Self, Holt & Schaninger, Reference Self, Holt and Schaninger2005). Also, by interacting with unit members, unit leaders can inform them about the supportive practices developed by the organization. In other words, unit leaders act as interpretive filters and can contribute to establishing a shared unit-level of POS (González-Romá, Peiró & Tordera, Reference González-Romá, Peiró and Tordera2002; Kozlowski & Doherty, Reference Kozlowski and Doherty1989). Second, employees who belong to the same work unit interact frequently. Through these interactions, they communicate and discuss the meanings they attribute to the organizational support practices implemented by the organization in their unit, developing in this way a shared perception of these practices, that is, unit-level POS (González-Romá & Peiró, Reference González-Romá, Peiró, Schneider and Barbera2014). Therefore, unit-level POS can be conceptualized as a shared unit construct (Kozlowski & Klein, Reference Kozlowski and Klein2000).

However, despite the factors that promote shared POS perceptions within units, there still is room for some variability in individual POS perceptions (González-Romá et al., Reference González-Romá, Peiró and Tordera2002). Unit-POS can provide a reference context that influence how individuals make sense of their perceptions and experiences (Johns, Reference Johns2006; Salancik & Pfeffer, Reference Salancik and Pfeffer1978; Ward et al., Reference Ward, Beal, Zyphur, Zhang and Bobko2022). This happen because individuals engage in social comparisons when objective criteria or comparison standards are unavailable (for a review, see Greenberg et al., Reference Greenberg, Ashton-James and Ashkanasy2007). The evaluation of how supportive or non-supportive an organization is perceived, is a typical case where objective standards are absent. In such cases, the absence of objective standards makes employees prone to use their most proximal environment (their work unit) as a reference (Greenberg et al., Reference Greenberg, Ashton-James and Ashkanasy2007; Mumford, Reference Mumford1983). Thus, unit-level POS provides a signal to employees about the amount of support they can expect in their work units (Karasek & Bryant, Reference Karasek and Bryant2012; Spence, Reference Spence1978).

This signaling function is more powerful for units with a low unit-level POS than for units with a high unit-level POS (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Beal, Zyphur, Zhang and Bobko2022). The basis for this asymmetry is that people are more sensitive to negative compared to positive events (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer & Vohs, Reference Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer and Vohs2001). This means that support-related events that occur in work units with low POS, such as experiencing support when facing problems with accomplishing work, make individual POS more salient than in work units with high POS. In work units with low POS, individual POS will have a greater influence on job satisfaction because employees in these units generally cannot count on their organization to deal with support-related negative events (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Beal, Zyphur, Zhang and Bobko2022). In work units with high POS, support-related negative events are not as salient as in units with low POS (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Beal, Zyphur, Zhang and Bobko2022), and employees feel that they can count on the organization to deal with them. Thus, individual POS will not be as influential to determine job satisfaction as in units with low POS. Based on the ideas presented above, we propose the following hypothesis involving a cross-level interaction:

Hypothesis 1: Unit-level POS moderates the positive relationship between employee POS and job satisfaction, so that the relationship is stronger when unit-level POS is low than when unit-level POS is high.

Work-unit clan culture and unit-level POS

Most studies on the antecedents of POS have been conducted at the individual-level (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock and Wen2020). To understand the role played by unit-level POS, which we defined as the shared perception among work-unit members that their organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being, we need to clarify its nomological network by uncovering its correlates. One of the potential antecedents of unit POS is work-unit clan culture values, defined as shared flexible and internally oriented values of attachment, support, and collaboration (Cameron & Quinn, Reference Cameron and Quinn2011; Quinn & Rohrbaugh, Reference Quinn and Rohrbaugh1983). These values aim to foster affiliation to produce positive affective employee evaluations toward the organization and come from the fundamental belief that ‘organizations succeed because they hire, develop, and retain their human resource base’ (Cameron, Quinn, DeGraff & Thakor, Reference Cameron, Quinn, DeGraff and Thakor2006, p. 38). Often, these values has been described as a reflection of family-like work environments (Alayo, Maseda, Iturralde & Calabrò, Reference Alayo, Maseda, Iturralde and Calabrò2023; Cameron & Quinn, Reference Cameron and Quinn2011).

Clan culture values promote unit-level POS through the experience of support by employees (Cameron & Quinn, Reference Cameron and Quinn2011; Quinn & Rohrbaugh, Reference Quinn and Rohrbaugh1983). In relation to unit-level POS, Levinson (Reference Levinson1965) argue that the personification of the organization, which is the basis of POS, evolves due to the continuity provided by culture. Employees form discrete exchange relationships with differing organizational targets, such as leaders and colleagues from within one’s unit and other departments, and perceive such targets in the degree to which they are shaping and implementing culture values (Hayton, Carnabuci & Eisenberger, Reference Hayton, Carnabuci and Eisenberger2012; Lavelle, Rupp & Brockner, Reference Lavelle, Rupp and Brockner2007). Those units which experience the prevalence of shared clan values of attachment, support, and collaboration experience high-relational exchanges between the unit and the organization, which develop into unit POS (Dufour, Andiappan & Banoun, Reference Dufour, Andiappan and Banoun2022; Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski and Rhoades2002; Self et al., Reference Self, Holt and Schaninger2005).

Empirical evidence at the individual-level suggests support for a relationship between a unit clan culture and unit-level POS. Generally, clan values such as attachment and collaboration have consistently been shown as antecedents of individuals’ POS (Kurtessis et al., Reference Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart and Adis2017; Myklebust, Motland, Bjørkli & Fostervold, Reference Myklebust and Motland2020; Vieira-dos Santos & Gonçalves, Reference Vieira-dos Santos and Gonçalves2018). For example, Vieira-dos Santos and Gonçalves (Reference Vieira-dos Santos and Gonçalves2018) found, in a cross-sectional study of 635 employees from higher education institutions, a positive relationship between perceptions of clan values and POS. Based on theoretical and empirical evidence, we suggest:

Hypothesis 2: Work-unit clan culture is positively related to unit-level POS.

Unit-level POS and unit-level satisfaction

To further clarify its nomological network at the unit-level, we propose that unit-level POS is positively related to unit-level satisfaction, defined as a shared favorable affective and cognitive appraisal of the job among work-unit members. Similarly to the antecedents of POS, most studies have undertaken an individual-level approach to the relationship between POS and outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction; Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock and Wen2020). The main reasoning behind an aggregate approach is that shared perceptions can shape collective affective and cognitive responses (Ostroff & Bowen, Reference Ostroff, Bowen, Klein and Kozlowski2000; Whitman, Van Rooy & Viswesvaran, Reference Whitman, Van Rooy and Viswesvaran2010). In other words, the individual-level experience of job satisfaction becomes shared when a work-unit has similar job experiences, which in turn shape similar affective and cognitive evaluations, with some degree of favor or disfavor (Whitman et al., Reference Whitman, Van Rooy and Viswesvaran2010). These job experiences results from the fact that employees within the same work-unit share the work environment and its conditions; employees share colleagues, a common workspace, values, practices, and procedures (Whitman et al., Reference Whitman, Van Rooy and Viswesvaran2010). Ultimately, this creates a bounded context that should influence a common interpretation, understanding, and evaluation of job experiences (Kozlowski & Hattrup, Reference Kozlowski and Hattrup1992; Salancik & Pfeffer, Reference Salancik and Pfeffer1978).

While there are several studies that examine unit-level satisfaction, most of these have examined how unit-level satisfaction is related to unit-level performance (Harter, Schmidt & Hayes, Reference Harter, Schmidt and Hayes2002; Whitman et al., Reference Whitman, Van Rooy and Viswesvaran2010). A few studies have empirically examined and found support for the empirical relationship between unit-level support and unit-level satisfaction (González-Romá, Peiró, Subirats & Mañas, Reference González-Romá, Peiró, Subirats, Mañas, Vartiainen, Avallone and Anderson2000; González-Romá et al., Reference González-Romá, Peiró and Tordera2002; Lindell & Brandt, Reference Lindell and Brandt2000). For example, in a study of work-unit characteristics and work outcomes in a regional public health service, González-Romá et al. (Reference González-Romá, Peiró and Tordera2002) found that unit-level colleague support shared a positive relationship with work-satisfaction across 197 work-units. Based on these theoretical arguments and empirical evidence, we propose:

Hypothesis 3: Unit-level POS is positively related to unit-level job satisfaction.

Method

Study design and recruitment of participants

The current study is a part of a larger research collaboration between the Department of Research at the Norwegian Police University College and the Department of Psychology at the University of Oslo. The aim is to examine characteristics of the Norwegian police organization, a national Norwegian public sector organization. The project follow the Helsinki Declaration on Ethical Standards for Research on Human Beings and has been approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (project id: 55,279). Data for the present study were collected through a cross-sectional survey administered electronically (Hafstad et al., Reference Hafstad, Bang, Bjørkli, Myklebust and Fostervold2024).

All employees in a rural police district received an email invitation containing a survey link, resulting in a census-based sampling approach rather than selective sampling. This approach was chosen to maximize representativeness, ensure adequate unit-level sample sizes, and reduce selection bias in multilevel analyses. Using a census approach ensured that employees from all units were invited, making the achieved sample structurally representative of the district’s workforce distribution with respect to role composition, demographic profile, and unit membership. This was especially important for the present study because the research questions required sufficient variability both within and between units to estimate multilevel relationships reliably. Moreover, because the Norwegian police is a hierarchically integrated national organization, unit structures and work processes are relatively standardized across districts, further supporting the broader relevance of the sampled district to comparable police contexts. The survey was open during work hours, and the district police chief endorsed the data collection to encourage broad participation while emphasizing voluntary participation. Thus, all participation in the research project was voluntary, and the participants could withdraw their consent at any time. The participants were also informed about the storing and processing procedures of materials and that no individual answers would be disclosed.

A total of 960 employees received the survey, and 317 (33%) employees completed the full survey. The sample consisted of 240 (75.7%) employees and 77 (25.4%) leaders. The percentage of men was (58.4%); 40.4% were women and 1.3% of the respondents declined to answer this question. The age ranged from 23 to 67 years old with a mean age of 43 years old (SD = 10.52). The 317 employees were part of a total of 48 working units. Work units was defined as the group of employees who hierarchically depend on the same leader. Those working groups that did not consist of three or more respondents was removed from the analysis (González-Romá, Fortes-Ferreira & Peiró, Reference González-Romá, Fortes-Ferreira and Peiró2009). Consequently, 45 workgroups were used to analyze the data. The median unit size was 5 (Mean= 6.29, SD = 4.75).

Measures

All questionnaire instruments used in this study had undergone formal translation and back-translation procedures as part of the broader research program. Following Brislin (Reference Brislin1980) guidelines, scales were translated from English to Norwegian by a bilingual subject-matter expert, independently back-translated into English by another bilingual researcher, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion to ensure semantic equivalence. Several of the measures had already been adapted and validated for the Norwegian police context in previous studies (Hafstad et al., Reference Hafstad, Bang, Bjørkli, Myklebust and Fostervold2024; Myklebust et al., Reference Myklebust, Hafstad, Bjørkli, Fostervold and Bjørklund2025; Myklebust et al., Reference Myklebust and Motland2020; Koritzinsky, Reference Koritzinsky2015), where psychometric evaluation supported their reliability and construct validity.

Some measures were piloted [Koritzinsky, Reference Koritzinsky2015], others in related studies conducted between 2020 and 2024 (Hafstad et al., Reference Hafstad, Bang, Bjørkli, Myklebust and Fostervold2024; Myklebust et al., Reference Myklebust, Hafstad, Bjørkli, Fostervold and Bjørklund2025; Myklebust et al., Reference Myklebust and Motland2020) and other in cross-national collaborations (Wojtczuk-Turek et al., Reference Wojtczuk‐Turek2024). These pilots involved small groups of police employees, students and other employees who assessed clarity, relevance and item wording. Minor linguistic adjustments were made based on participant feedback, ensuring that items were understandable, culturally appropriate, and applicable to the operational and administrative context of the Norwegian police.

Clan culture. Clan culture was operationalized and measured using four items developed by Kuenzi (Reference Kuenzi2008). The items was translated and back translated and piloted on a Norwegian sample (Koritzinsky, Reference Koritzinsky2015). As recommended when organizational culture is the measure of interest, clan culture was operationalized following a referent-shift consensus model (Chan, Reference Chan1998), where the work unit was the reference point. One sample item is ‘In this unit, employees develop supportive, positive working relationships among organization members.’ Items used a 5-point Likert-type scale with semantic anchors on both sides, ranging from (1) ‘definitely false’ to (5) ‘definitely true’. The reliability of the scale at the individual-level as estimated by the omega (ω) coefficient was satisfactory (ω = .89). The Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (1) obtained [ICC(1) = .31] indicated that 31% of the variance resided at the unit level. Moreover, the value computed for ICC(2) (.88) indicated that the unit mean in this variable was reliable. The within-unit agreement (rWG(j) = .85) was above the recommended threshold of .70 (LeBreton & Senter, Reference LeBreton and Senter2008). All these results supported aggregation to the unit level (Biemann, Cole & Voelpel, Reference Biemann, Cole and Voelpel2012; Lance, Butts & Michels, Reference Lance, Butts and Michels2006).

Unit- and individual-level POS. POS (individual-level ω = .92) was measured using an eight item scale developed by Eisenberger, Cummings, Armeli and Lynch (Reference Eisenberger, Cummings, Armeli and Lynch1997). The items were translated and back translated for this study. Unit-POS was operationalized following a referent-shift consensus model (Chan, Reference Chan1998), in which the referent was the organization. One sample item is, ‘This organization is willing to help employees if they need a special favour.’ Items used a 5-point Likert-type scale with semantic anchors on both sides, ranging from (1) ‘definitely false’ to (5) ‘definitely true’. The Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (1) obtained [ICC(1) = .29] indicated that 29% of the variance resided at the unit level. Moreover, the value computed for ICC(2) (.90) indicated that the unit mean in this variable was reliable. The within-unit agreement (rWG(j) = .85) was above the recommended threshold of .70 (LeBreton & Senter, Reference LeBreton and Senter2008). All these results supported aggregation to the unit level.

Unit- and individual-level job satisfaction. Job satisfaction (individual-level ω = .87) was measured by a three item scale developed by Cammann, Fichman, Jenkins and Klesh (Reference Cammann, Fichman, Jenkins, Klesh, Seashore, Lawler, Mirvis and Cammann1983). The items were translated and back translated for the purpose of this study. Unit job satisfaction was conceptualized as a direct consensus model of aggregation (Chan, Reference Chan1998). One sample item is, ‘All in all, I am satisfied with my job.’ Items used a 5-point Likert-type scale with semantic anchors on both sides, ranging from (1) ‘definitely false’ to (5) ‘definitely true’. The Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (1) obtained [ICC(1) = .13] indicated that 13% of the variance resided at the unit level. Moreover, the value computed for ICC(2) (.84) indicated that the unit mean in this variable was reliable. The within-unit agreement (rWG(j) = .76) was above the recommended threshold of .70 (LeBreton & Senter, Reference LeBreton and Senter2008). All these results supported aggregation to the unit level.

Control variable. We considered employee age as a potential control variable. Ng and Feldman’s (Reference NG and Feldman2010) meta-analysis showed that employee age was weakly related to job satisfaction (weighted corrected r = .18, 95% Confidence Interval = (.17, .19)). Moreover, socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen, 1991) posits that there is a life-long selection process through which older adults are more likely to find jobs they enjoy and fit better to their personal characteristics. Thus, to remove alternative explanations and show the unique relationship between employee POS and job satisfaction, we controlled for employee age. However, after testing our research model including employee age, we observed that its relationship with job satisfaction was zero (b = .00). Moreover, the results obtained without employee age were similar to those obtained including it. Therefore, following Bernerth and Aguinis’ (Reference Bernerth and Aguinis2016) recommendation, for the sake of parsimony and to maximize statistical power, we report the results without employee age.

Data analysis procedures

The hypothesized relationships were tested simultaneously at the individual- and unit-level using Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2017). This program decomposes the variance of the variables that vary at the individual- and unit-level (POS and job satisfaction) into two orthogonal components: within (individual-level) and between (unit-level), and allows researchers to model them at the corresponding level.

We employed Bayesian estimation because the frequently used Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation yielded convergence problems. Moreover, when using ML estimation with Mplus, the program reported that ‘the predictor variable on the WITHIN level [POS] refers to the whole observed variable’. This meant that the program did not use the within component on POS to model relationships at the within (individual) level, but the whole POS variable (with its within and between components). Doing so involves conflated estimates of individual-level relationships, which are undesirable (see Preacher et al., Reference Preacher, Zyphur and Zhang2010). To fix this problem, Mplus recommended to use Bayesian estimation with the following message: ‘To use the latent within-level part [of the predictor variable on the WITHIN level (POS)], use ESTIMATOR = BAYES in the ANALYSIS command.’ Bayesian estimation also has a number of advantages for testing research models and theories (González-Romá & Hernández, Reference González-Romá and Hernández2017, Reference González-Romá and Hernández2023). First, it works well with complex multilevel models that include random slopes (like ours). Second, it performs better than ML estimation with samples composed of a small number of higher-level units (N ≥ 25). Third, it allows researchers to directly compare alternative theories through the Bayes factor.

We used Bayesian estimation with the default uninformative priors. The Bayes estimator yields results that are similar to the ML estimator when uninformative priors are used (Van de Schoot et al., Reference Van de Schoot, Kaplan, Denissen, Asendorpf, Neyer and Van Aken2014). Together with Bayes estimates, we reported the corresponding 90% credibility intervals (CI). A credibility interval is an interval within which an unobserved parameter value falls with a particular probability. We used 90% CI because they are more suitable for hypotheses about relationships between variables with a specific expected direction based on theory (Cho & Abe, Reference Cho and Abe2013). Moreover, they are more stable than 95% CI (Kruschke, Reference Kruschke and JAGS2014).

Results

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations among the study observed variables are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and zero-order correlations of variables in this study computed at the individual level

Note: N = 317. Pairwise deletion.

** p < .001. SD = standard deviation. The main diagonal contains omega reliability estimates.

Individual-level, work-unit level, and cross-level relationships

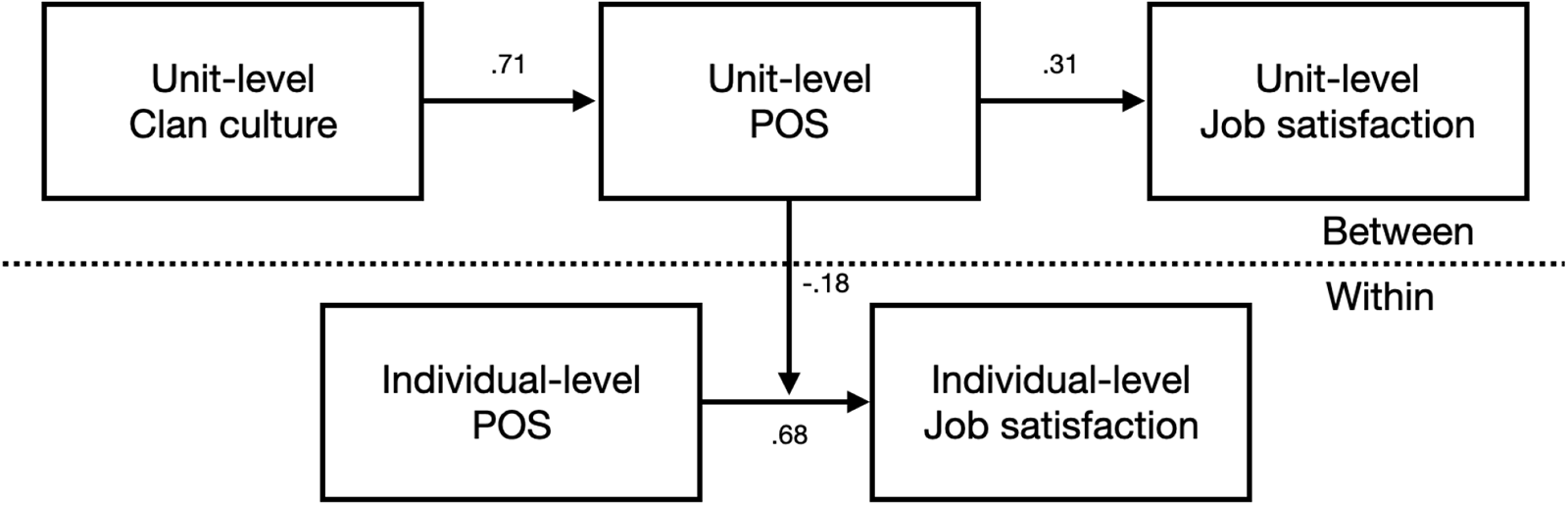

Table 2 and Figure 2 show the results from our analysis. At the individual-level, POS was positively related to job satisfaction (b = .68, 1-tailed p-value (For a positive estimate, this p-value is the proportion of the posterior distribution that is below zero. In this case, less than 05.) = .014; 90% CI = [0.159, 1.218]). This meant that, at the individual-level, employees’ relative POS (to the unit mean) was positively related to employees’ relative job satisfaction. Our model explained 8% of the variance of job satisfaction at the individual (within) level.

Figure 2. The final model. Unit-level POS is influenced by clan culture and moderates the relationship between POS and job satisfaction. Note: Unstandardized coefficients. N = 317.

Table 2. Unstandardized parameter estimates for the hypothesized model

Note: CI = credibility interval.

a slope estimating the relationship between individual POS and job satisfaction (cross-level interaction).

Regarding Hypothesis 1, we found that unit-level POS was negatively related to the individual-level relationship between POS and job satisfaction (b = − .18, 1-tailed p-value (For a negative estimate, this p-value is the proportion of the posterior distribution that is above zero. In this case, less than 05.) = .034; 90% CI = [−.356, − .010]). The values of the CI indicated that there was .90 probability that the parameter’s true value was somewhere between −.356 and −.01. This meant that there was less than .05 probability that the coefficient’s true value was 0 or positive, and there was more than .95 probability that the coefficient’s true value was negative. To facilitate the interpretation of the hypothesized cross-level interaction, we represented it in Figure 3. At low levels of unit-POS (X-axis), the relationship between individual POS and job satisfaction (Y-axis) was positive and large. However, as unit-POS increases the relationship becomes weaker, and it turns out non-significant when unit-POS ≥3.2. In addition, we computed the simple slopes associated with the individual-level relationship between POS and job satisfaction for different levels of the moderator (unit POS; see Table 3). The values obtained showed that the simple slopes were significant when unit POS was smaller or equal to the mean and nonsignificant when it was larger than the mean. These results supported Hypothesis 1. Our model explained 36% of the variance shown by slope estimating the individual relationship between POS and job satisfaction across work units.

Figure 3. The moderated relationship of unit-level POS on the relationship between individual-level POS and job satisfaction.

Table 3. Simple slopes for the POS-job satisfaction individual level relationship or different values of unit POS

Regarding Hypothesis 2, we found that, at the unit (between) level, unit clan culture was positively related to unit POS (b = .71, 1-tailed p-value < .01; 90% CI = [.528, .889]). These results supported Hypothesis 2. The model explained 56% of the variance of unit-POS.

Finally, as to Hypothesis 3, we observed that, at the unit (between) level, unit POS was positively related to unit job satisfaction (b = .31, 1-tailed p-value < .01; 90% CI = [.176, .438]). These results rendered support to Hypothesis 3. The model explained 61% of the variance of job satisfaction at the unit level.

Discussion

This study proposed and found support for a multilevel model in which unit-level POS moderated the relationship between individual-level POS and job satisfaction. Moreover, unit POS was positively associated with unit clan culture and unit job satisfaction. Our findings have several theoretical and practical implications that we discuss next.

Theoretical implications

Our study extends OST theory (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock and Wen2020, Reference Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski and Rhoades2002) by adopting a multilevel perspective. Our findings contribute to OST and the broader POS literature by specifying how POS operates as a multilevel phenomenon. Although POS has primarily been theorized and tested at the individual level, OST also implies that support perceptions emerge from interpretive processes shaped by organizational practices and social context. By demonstrating that unit-level POS moderates the individual-level POS–job satisfaction relationship, our results extend prior POS work by showing that the attitudinal consequences of POS are not solely a function of an employee’s personal support beliefs, but also of the shared support context in which those beliefs are formed and evaluated. This means that unit POS provides an important context to understand the aforementioned relationship; it is a reference that helps understand how individuals make sense of their perceptions and experiences (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Beal, Zyphur, Zhang and Bobko2022). The moderator role that unit POS plays is based on signaling theory (Karasek & Bryant, Reference Karasek and Bryant2012). Unit POS gives unit members a signal about the amount of support they can expect in their work units. In units with low average POS, employees realize that they cannot generally count on their organization to deal with support-related negative events. In these circumstances, individual-level POS becomes relevant, and thus, it is strongly and positively related to job satisfaction. On the contrary, in units with high average POS, employees generally think that they can count on the organization to deal with support-related negative events, so that these events are not as salient as in units with low POS. Thus, in units with high average POS, individual-level POS is less important as a determinant of job satisfaction. POS theory should consider the cross-level interaction found here to fully understand the role that POS plays at multiple levels. This finding advances multilevel POS theorizing by positioning unit POS as a consequential contextual property that qualifies when individual POS is most predictive of job satisfaction.

Second, our results refine the explanatory logic of OST by integrating social exchange reasoning with the idea that employees’ reciprocity-based responses depend on the perceived reliability and clarity of support cues in their proximal context. Meta-analytic evidence has established that individual POS relates to job satisfaction (Kurtessis et al., Reference Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart and Adis2017), typically interpreted through SET’s reciprocity mechanisms. Our cross-level interaction adds theoretical nuance to this dominant account: in units where shared POS is low, individual differences in POS appear to matter more for job satisfaction, consistent with the argument that perceived support becomes a more diagnostic resource for evaluating one’s employment relationship when the collective context offers weaker or more inconsistent support expectations. Conversely, in units where shared POS is high, the incremental role of individual POS is attenuated, suggesting that a strong, shared support environment may reduce variability in how employees translate personal support beliefs into satisfaction. The implication for OST/SET is that POS processes should be conceptualized not only as individual exchange perceptions but as exchange perceptions embedded in unit-level interpretations.

Third, our findings extend the nomological network of POS at higher levels of analysis. Prior research has provided substantial evidence on individual-level antecedents and outcomes of POS (Kurtessis et al., Reference Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart and Adis2017), but considerably less is known about POS as a unit-level shared construct (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Rhoades Shanock and Wen2020). By showing that unit POS is positively associated with unit clan culture values and unit job satisfaction, we provide theory-consistent evidence that shared support perceptions are meaningfully embedded in unit cultures characterized by collaboration, cohesion, and mutual care, and that these shared perceptions relate to collective evaluative states. This complements OST by suggesting that unit POS is not merely an aggregate of individual sentiments, but an emergent unit property with theoretically coherent antecedents and outcomes.

Finally, along with some recent research, our findings also have implications for multilevel theory in organizations. Our results are congruent with the results obtained by Ward et al. (Reference Ward, Beal, Zyphur, Zhang and Bobko2022). In their study, they investigated the relationships between diversity climate and employee trust. They found that unit diversity climate moderated the positive relationship between individual perceptions of diversity climate and employee trust, so that the relationship was stronger when unit diversity climate was low. The study by Ward et al. (Reference Ward, Beal, Zyphur, Zhang and Bobko2022) and our present study highlight the importance of accounting for higher-level constructs (unit diversity climate and unit POS, respectively) as cross-level moderators that provide a reference context for individual-level relationships. This reference context provides a platform to fully understand the individual-level relationships between similar constructs operationalized at lower levels (individual diversity climate perceptions and individual POS) and individual-level outcomes (employee trust and job satisfaction, respectively). These findings uncover a moderator role rarely examined which should be considered in multilevel organizational theory and research.

However, beyond these core findings, our results should be interpreted in light of other potential explanations and boundary conditions that may shape POS processes and provide possibilities for future research. For example, future research could benefit from examining second-order interactions and how this may influence the strength of the moderating effect of unit POS. A recent study by Choi et al. (Reference Choi, Oh, Park, Colbert, Kim and Kang2025) show that the strength of unit POS moderate the relationship between unit POS and task performance and organizational citizenship behavior. Furthermore, they found that task interdependence moderated the two-way interaction in such a way that unit POS was amplified in groups with higher task interdependence. This suggests that future research can benefit by examining the how unit size, task interdependence, and the degree of interaction among members can influence the extent to which shared perceptions consolidate and become psychologically meaningful (Kozlowski & Klein, Reference Kozlowski and Klein2000; Ostroff & Bowen, Reference Ostroff, Bowen, Klein and Kozlowski2000). For instance, if we are to take social comparison theory at face value, social comparison mechanisms are likely stronger in small, highly interdependent units where employees frequently observe one another’s treatment. In contrast, signaling processes may dominate in larger or more structurally differentiated units where employees rely primarily on leader actions to infer organizational support. However, how and when this is crucial is yet to be discovered.

Finally, the national cultural context in this study may also act as a boundary condition. Norway’s egalitarian norms and high societal trust may amplify the salience of shared support perceptions compared to more hierarchical cultures, where organizational cues may be interpreted differently (Jolly et al., Reference Jolly, Kong and Kim2021; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Eisenberger, Takeuchi and Baik2022). The Norwegian context is characterized by relatively egalitarian social structures, low power distance, and high levels of generalized trust (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2011). These cultural features increase the likelihood that employees view their work unit as a salient and reliable reference point for interpreting organizational signals. As a result, shared perceptions of support may consolidate more easily, strengthening the moderating role of unit POS on the relationship between individual POS and job satisfaction. In cultures with similar egalitarian orientations – such as the Nordic countries or other high-trust welfare states – shared support perceptions may operate in comparable ways.

By contrast, in more hierarchical, high power-distance contexts, the dynamics we observed may unfold differently. In such settings, employees may rely more heavily on formal authority structures or organizational status hierarchies than on peer-based social comparison processes when interpreting support. Similarly, in environments characterized by low institutional trust or strong economic insecurity, organizational cues may be interpreted with greater skepticism, weakening the influence of unit-level POS. These cultural contingencies suggest that the multilevel processes identified in our study may be most pronounced in contexts where employees feel empowered to interpret and discuss organizational support collectively, and where peer norms carry substantial informational and social weight. Future research should therefore examine how the national culture context intersects with unit culture to shape the emergence and impact of POS across contexts.

The potential for reverse causality. Although our theoretical model specifies directional relationships among unit clan culture, unit POS, and unit job satisfaction, the cross-sectional nature of our data means that alternative causal explanations cannot be ruled out. For example, units that are already characterized by high collective job satisfaction may be more likely to interpret organizational actions favorably and therefore develop stronger shared perceptions of organizational support. Under this alternative account, unit POS could partially reflect the positive affective tone of satisfied units rather than functioning strictly as an antecedent.

Similarly, at the unit level, clan culture values may not only shape perceptions of organizational support but may also be reinforced by them. Units that collectively perceive strong organizational support may be more inclined to promote behaviors associated with collaboration, attachment, and mutual care, thereby strengthening clan-like values over time. This possibility suggests that clan culture and unit POS may evolve together through iterative social processes rather than through a strictly unidirectional pathway.

While our theoretical rationale is consistent with prior research on POS emergence and multilevel processes, these alternative temporal explanations highlight the need for longitudinal designs to establish causality. Future studies could disentangle the potential for such dynamics by using repeated measurement of unit POS, clan culture values, and unit-level satisfaction, and employ cross-lagged panel models to ascertain directionality over time.

Practical implications

For organizations and managers, our study has important practical implications. First, we found that unit clan culture was positively related to unit POS, which in turn was positively related to unit job satisfaction. We did not hypothesize the indirect ‘effect’ of unit clan culture on unit job satisfaction via unit POS because the focus of our study was on the role of unit POS as a cross-level moderator and its correlates at the unit-level. However, we estimated this indirect effect to support our first practical implication. The result obtained (indirect effect = .22, SE = .07, 90% Monte Carlo Confidence Interval = [.11, .34]) showed that it was statistically significant and positive. Based on this, we suggest that managers and organizations should promote clan values as a way to enhance unit satisfaction through unit POS. The positive relationship between unit clan culture and unit POS suggests that cultivating shared values of collaboration, mutual care and interpersonal support within work units can meaningfully enhance how employees interpret the organization’s intentions. To create clan cultures, managers can work to create a pleasant and supportive work atmosphere by recognizing and rewarding supportive behavior, and emphasizing collaboration, cohesion and teamwork. To further promote these values, managers could model inclusive behavior (e.g., openly soliciting input from all unit members during meetings and acknowledging diverse perspectives; Gürbüz, Van der Heijden, Freese & Brouwers, Reference Gürbüz, Van der Heijden, Freese and Brouwers2024; Hollander, Reference Hollander2012; Shore, Cleveland & Sanchez, Reference Shore, Cleveland and Sanchez2018), encourage collective problem solving (for instance, by organizing short team huddles where employees jointly address operational challenges; Chapin, Brannen, Singer & Walker, Reference Chapin, Brannen, Singer and Walker2008; Di Nota, Scott, Huhta, Gustafsberg & Andersen, Reference Di Nota, Scott, Huhta, Gustafsberg and Andersen2024; Malcolm, Seaton, Perera, Sheehan & Van Hasselt, Reference Malcolm, Seaton, Perera, Sheehan and Van Hasselt2005), and reward acts that signal care for coworkers (such as recognizing employees who assist colleagues during peak workload periods or who proactively share critical information; Brimhall & Palinkas, Reference Brimhall and Palinkas2020). Such practices are likely to be especially effective when implemented consistently within units, as they serve as repeated, observable cues that shape employees’ shared interpretations of organizational values.

Second, as our results point out, managers of units with low levels of average POS should know that in these units, individual-level POS is crucial for employee job satisfaction. In these units, managers could promote job satisfaction by cultivating unit members’ individual POS. In units with low average POS, employees rely more heavily on their own experiences to infer organizational intent, making individualized actions particularly influential. Managers in these units can prioritize direct, personalized signals of support – such as frequent developmental feedback, individualized recognition, and one-on-one check-ins – to strengthen individual POS and improve job satisfaction (Steelman & Wolfeld, Reference Steelman and Wolfeld2018). In contrast, in units with high average POS, collective practices may exert a strong influence at the unit level, affecting all the unit members. Here, managers may focus on maintaining transparent communication, reinforcing shared norms that signal organizational care, and ensuring consistent access to supportive resources. These differentiated strategies based on the results we observed at different levels underscore that enhancing job satisfaction requires different practices depending on the level of the addressed outcome (individual vs unit).

Finally, our results suggest that organizations should monitor unit-level variation in POS rather than assuming uniformity across the organization. Doing so allows managers to identify units where support signals are weak, inconsistent, or misaligned with organizational intentions. When such discrepancies are detected, organizations can intervene in several targeted ways. For example, leadership development efforts can focus on helping supervisors and managers translate organizational policies into day-to-day supportive behaviors, such as providing timely information, offering resource access, or showing individualized consideration (Gürbüz et al., Reference Gürbüz, Van der Heijden, Freese and Brouwers2024; Shore et al., Reference Shore, Cleveland and Sanchez2018; Steelman & Wolfeld, Reference Steelman and Wolfeld2018). Likewise, structured onboarding and socialization practices can ensure that new employees receive consistent cues about support, regardless of the unit they join. In addition, establishing unit-specific feedback loops – such as regular pulse surveys, facilitated team reflections, or short debriefs following critical events – can help managers track whether support signals are being interpreted as intended and quickly address emerging gaps. By systematically addressing unit-level disparities in POS, organizations can create more coherent support experiences and reduce unevenness in employee well-being across the broader system.

Limitations and future research recommendations

Our study has some limitations concerning our sample and our research design. First, our results are from a rural police district in Norway, and the differences in perceptions between unit- and individual-level POS may be sample-specific. Although the organizational structure of the Norwegian police is nationally standardized, rural districts differ from urban districts in size, task variation and resource availability, which may shape both the emergence and interpretation of support signals. Thus, caution should be made when interpreting our results; generalizability beyond the police organization remains an open question. Future research should examine whether similar multilevel relationships emerge in other public-sector domains or in organizational fields with different cultural norms, governance systems, or work designs.

Second, as mentioned above, this study used a cross-sectional research design, which hampers our ability to examine the direction of relationships (Spector, Reference Spector2019). This means that alternative causal sequences – such as unit satisfaction shaping unit POS, or unit POS reinforcing clan-like values – cannot be ruled out. However, our research model is congruent with prior theory and empirical evidence on unit POS, which suggests that the hypothesized relationships were plausible. Despite this, longitudinal and cross-lagged designs are needed to more clearly determine temporal ordering and disentangle potential reciprocal influences among the study variables.

Finally, this study may be prone to common method bias due to the data being gathered by self-report questionnaires (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). Although POS and job satisfaction are inherently perceptual constructs that are most appropriately assessed through self-report, relying on a single method at one point in time raises the possibility that shared method variance inflated some of the observed relationships. Scholars have noted, however, that the practical impact of common method variance is often overstated, and empirical evidence suggests that its effects are typically modest and do not fully account for theoretically grounded relationships (Brannick et al., Reference Brannick, Chan, Conway, Lance and Spector2010). Nevertheless, the possibility remains, and future research would benefit from incorporating alternative data sources – such as supervisor ratings, behavioral indicators of support practices, archival performance data, or time-separated measurement – to triangulate employee perceptions and reduce method-related concerns. Combining perceptual and non-perceptual indicators would also allow researchers to examine how different sources of information converge or diverge in shaping the emergence and consequences of POS at multiple levels.

Conclusion

This study advances the literature on POS by demonstrating that POS is inherently multilevel and shaped by both individual experiences and shared unit-level interpretations. By integrating OST with insights from signaling and social comparison processes, we show that unit POS serves as a meaningful context in which employees evaluate organizational treatment and form attitudes such as job satisfaction. Our findings further clarify the nomological network of POS by identifying unit clan culture as an antecedent and unit-level job satisfaction as an outcome of shared support perceptions. Together, these results highlight that understanding employee attitudes requires attention not only to individual perceptions but also to the collective frames through which these perceptions are interpreted.

The implications of our work extend beyond theory. The results underscore the importance of cultivating supportive unit cultures, tailoring managerial practices to local support conditions, and recognizing that employees’ reactions to organizational actions are shaped by both individual experiences and shared unit norms. By embracing a multilevel perspective, future research can continue to refine our understanding of how organizations foster supportive environments that enhance employee well-being.

Funding Statement

The project is funded by the Norwegian Police University College.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.