Introduction

As Europe has received more immigrants in the past decades, it has become all too evident that liberal democracies are still challenged by the fact of difference, above all, cultural and religious difference (Sniderman and Hagendoorn Reference Sniderman and Hagendoorn2007; Dancygier Reference Dancygier2010; Geddes and Scholten Reference Geddes and Scholten2016). The commonalities of intolerance of difference – the fear of change, the strains of dislocation, the anxieties and resentments of the socially and psychologically marginal – are well-established (eg Gibson Reference Gibson1992; Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009; Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2017). It is accordingly natural to suppose that the challenge of inclusion of Muslims in Western Europe at its core is a variation of the challenge of inclusion of minorities in America. Comparable forces are at work (see eg Zolberg and Woon Reference Zolberg and Woon1999).

In this study, however, we demonstrate why the challenge of inclusion of Muslims may prove even more formidable. Minorities have the same rights to freedom of expression and assembly as majorities. However, acceptance of religiously grounded values that conflict with the values of contemporary liberal democracies poses a problem, the full dimensions of which have not been appreciated. There is, of course, the well-documented first-order conflict of opposing substantive values – between, for example, the right of women to equal standing with men versus the limits that conservative Islam deems proper for women (eg Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Ivarsflaten and Sniderman Reference Ivarsflaten and Sniderman2022). But a second-order conflict has gone unrecognized. Communication of religiously grounded beliefs often takes the form of performative utterances, instances of when to say something is also to do something – namely, to call for adherence. This call for compliance is itself a source of conflict. And a certain combination of the substantive and the speech-act dimensions of value conflict can massively undercut support for the fundamental democratic rights of religious minorities.

Empirically, we focus on support for the civil liberties of Europe’s largest religious minority, Muslims. Muslims have an unassailable right to civil liberties under constitutional law in a liberal democracy. Our interest is in public support for such rights in the face of controversy and conflicting demands. Muslims are not monolithic. Many adhere to conservative interpretations of Islam; many do not. We focus on Muslims with religiously conservative beliefs in our study because their civil liberties and religious freedom pose the toughest challenges to both political leadership and the general public in contemporary Western European liberal democracies. Conflicts on this form therefore require special scholarly attention (Dancygier Reference Dancygier2024; Ivarsflaten, Helbling, Sniderman et al. Reference Ivarsflaten, Helbling, Sniderman and Traunmüller2024).Footnote 1

We test the two-dimensional value conflict hypothesis in a series of classical tolerance experiments (Stouffer Reference Stouffer1955; Sullivan, Piereson and Marcus Reference Sullivan, Piereson and Marcus1982). The experiments measure support for Muslims’ civil rights – to hold a public rally, to rent a room in a public library, and to hold a meeting. The background premise is always that the gathering conforms to relevant time, place, and manner regulations. Consistent with previous research, we expect that experimentally introducing a substantive conflict between culturally liberal and conservative religious values reduces public support for minority rights. Our innovation is to also experimentally manipulate the speech-act at the public event – whether it is communicative, ‘to discuss’ or ‘to explain’, ie to convey a religious tenet, or performative, ‘to preach’, ie both to convey a religious tenet and call for adherence to it.

Experimentally varying performative and communicative utterances in the context of religiously grounded values brings out two original results. First, even in the absence of a substantive conflict with culturally liberal values, calls for adherence to an Islamic tenet lead to a substantively significant reduction in support for Muslims’ right to assembly. Second, when both dimensions of value conflict, the content and the speech act, put pressure on culturally liberal citizens, we see a society-wide failure to uphold Muslims’ civil liberties. The combination of Muslims favoring a conservative religious tenet and calling for adherence to it transforms a majority supportive of Muslims’ right to assembly into a majority opposed to it.

The theory of speech acts

Taking a lead from the theory of speech acts (Austin Reference Austin and Urmson1962; Searle Reference Searle2011), we focus on performative utterances – instances of when ‘the issue of the utterance is the performing of an action’, (Austin 1961: p. 5) or more colloquially, instances of when to say something is also to do something. Two iconic examples bring the idea home:

‘(E. a) “I do (sc. Take this woman to be my lawful wedded wife)” – as uttered in the course of the marriage ceremony.

(E. b) “I name this ship the Queen Elisabeth” – as uttered when smashing the bottle against the stem’ (ibid).

Saying the words, ‘I take this woman to be my lawful wedded wife’, is not merely to say something; it is to do something. To name a ship is not merely to say something; it is to do something.

Assertions of religious tenets are performative utterances, instances of when to say something is also to do something – namely, to call for adherence. To preach that homosexuality is a sin is not just to convey the idea that homosexuality is wrong. It is also to inherently require adherents to abhor homosexuality. To preach that a Muslim woman may not work without the permission of her husband is not merely to communicate an article of faith. It is also to inherently require Muslim women to obtain the permission of their husbands to work. Assertions of faith thus couple the communication of a value and a call for compliance with it.

Recognizing the performative function of assertions of faith brings into the open, for the first time, the full challenge liberal democracies face in reconciling conflicts between majority values and minority religious convictions on terms acceptable to both. On the one side, liberal democracies owe Muslim minorities the full rights of citizenship, very much including freedom of religion, expression, and assembly. On the other side, the doubling of substantive and speech-act dimensions gives conflicts between liberal and religiously grounded values an intense sting.

Support for the civil liberties of minorities

Progressive attitudes towards individual autonomy, the environment, abortion, and homosexuality have gained ground in liberal democracies around the world (eg Inglehart and Welzel Reference Inglehart and Welzel2007; Welzel Reference Welzel2013; Inglehart Reference Inglehart2018). But public opinion tends to follow a thermostatic model: a movement in one direction provokes a counter-movement in the opposite direction (Wlezien Reference Wlezien1995; Soroka and Wlezien Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010). Thus, the advance of cultural liberalism has reinvigorated cultural conservatives to defend tradition, social order, and nationalism (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). In turn, centering politics on social and cultural issues rather than the economic axis historically dominating political competition has motivated working class voters, holding more culturally conservative views, to abandon the traditional left and vote for the radical right, especially when issues of immigration and border control become central in politics (see eg Kitschelt and McGann Reference Kitschelt and McGann1995; Ivarsflaten Reference Ivarsflaten2005; Kriesi, Grande, Lachat et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Bartels Reference Bartels2023).

The conflict between cultural liberalism and cultural conservatism is without doubt the central focal point in contemporary cultural divides (eg Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Van der Noll, Saroglou, Latour et al. Reference Van der Noll, Saroglou, Latour and Dolezal2018; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Helbling and Traunmüller Reference Helbling and Traunmüller2020; Choi, Poertner, and Sambanis Reference Choi, Poertner and Sambanis2022a). Conflict on this order is interpersonal, with the culturally liberal lining up on one side and the culturally conservative on the other. Our concern is when two liberal values, for example, support for gender equality and support for the inclusion of minorities, come into conflict with one another (eg Sniderman and Hagendoorn Reference Sniderman and Hagendoorn2007; March Reference March2009).Footnote 2 This type of value conflict is intrapersonal, liberals sometimes choosing in favor of gender equality, sometimes in favor of minority rights. Hence, the liberal value conflict hypothesis (H1).

H1: When the liberal value of minority rights comes into conflict with other liberal values, such as, for example, gender equality, support for the civil liberties of Muslims will be reduced, especially among cultural liberals.

The performative utterance hypothesis draws attention to the speech-act dimension of value conflicts. For an Imam to declare, ‘A Muslim should not shake hands with a member of the opposite sex’, is to enjoin a Muslim man from touching a woman, or a Muslim woman from touching a man.Footnote 3 Assertions of religious tenets entail a call for adherence, and adherence is the duty of the devout Muslim. Opposition to the call for the religiously faithful to comply with religiously grounded values is a separate and additional source of conflict. Hence, the performative utterance hypothesis (H2).

H2: Assertions of Islamic tenets, independent of reactions to conflicting substantive values, will reduce commitment to Muslims’ civil liberties.

The conjunction hypothesis concerns the combined impact of the two dimensions of value conflict – both the content and the speech act.

H3: The combination of asserting an Islamic tenet (the speech-act dimension) that conflicts with a culturally liberal value (the substantive dimension) can lead cultural liberals to withdraw support for the rights of Muslims and join those on the right in opposition to Muslims’ rights to freedom of assembly and freedom of speech.

Data and methods

The data analyzed here are not only collected in three different countries, but in three different kinds of online panels. All studies have been formally approved to be in compliance with the human-subject guidelines of the authors’ home institutions and with the relevant national and EU regulations on research ethics and data protection. Most (5, see Table 1) experiments were fielded in the Norwegian Citizen Panel (NCP), a high-quality research-based panel with a random sample directly drawn from the Norwegian population registry above the age of 18. Participation in the panel is by informed voluntary consent, and participants can enter a draw to win one of three prizes valued at USD 500. All content fielded in the NCP is approved by an internal review board and is thoroughly piloted before being fielded. Deception is prohibited. The experiments were part of the NCP waves 18, 22, and 24 (Ivarsflaten, Arnesen, Dahlberg et al. Reference Ivarsflaten, Arnesen, Dahlberg, Løvseth, Eidheim, Peters, Knudsen, Tvinnereim, Böhm, Bye, Bjånesøy, Fimreite, Schakel and Gregersen2023a; Ivarsflaten, Dahlberg, Løvseth et al. Reference Ivarsflaten, Dahlberg, Løvseth, Bye, Bjånesøy, Böhm, Fimreite, Schakel, Gregersen, Elgesem, Nordø, Peters, Dahl and Faleide2023b, Reference Ivarsflaten, Dahlberg, Løvseth, Dahl, Bye, Bjånesøy, Gregersen, Böhm, Elgesem, Schakel, Fimreite, Nordø and Knudsen2023c) and respondents in the sample were recruited through multiple waves. Some respondents are more likely to respond and to stay on as panel participants. Survey weights are therefore used to correct for known biases regarding gender, age, region, and education. Studies of the representativity of online survey samples recommend this combination of a probability sample with survey weights as best practice (eg Cornesse and Blom Reference Cornesse and Blom2020).

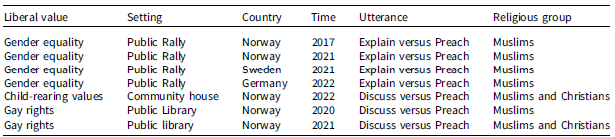

Table 1. Overview of trials

One of the public rally experiments was fielded in Germany in 2022. Respondents were recruited from an online panel by the survey company Respondi. Participation in the study was by voluntary informed consent, and participants received a small standard fee for their participation. This is a nonprobability panel that by design matches the general German population in terms of gender, age, and education. Survey weights are therefore not used in this data. The total sample has 2691 respondents. The current sample has 51 per cent female respondents, the mean respondent is 47 years old (SD = 15 years), and about 23 per cent of the sample have higher university education. Non-probability online panels have been found to attract more respondents who do not pay sufficient attention when responding and who therefore introduce noise in the data (Peyton, Huber, and Coppock Reference Peyton, Huber and Coppock2021). We therefore included attention checks in this survey. Section B in the online Supplementary Material shows results excluding respondents who failed attention checks. The results are close to identical to those of the full sample, so we present results based on the full sample in the paper.

The final public rally experiment was fielded in Sweden in 2021 in the Swedish Citizen Panel (SCP) as part of panel wave 41. The SCP is a research-purpose online panel run by the Laboratory of Opinion Research (LORE) at the University of Gothenburg. Respondents in the SCP are recruited with both probability- and non-probability-based methods. Participation is always by informed voluntary consent, and studies have to be approved by a national ethics committee before being fielded. The sample for the reported experiment was probability-based. The net sample size for the study was 2380, of which 1364 completed the full survey for an AAPOR RR5 response rate of 55 per cent. The completed sample has 51 per cent female respondents. The respondents are between 18 and 85 years old (Martinsson, Andreasson, Andersson et al. Reference Martinsson, Andreasson, Andersson, Cassel, Enström and Rosberg-Carlsten2021), and 27 per cent of the respondents have a university education of more than three years.

Since the hypotheses concern the responses of non-Muslims, we excluded respondents who identified as Muslim from the analyses to the extent possible. In the Norwegian samples, there were fewer than 10 Muslims in each trial.Footnote 4 Forty-eight respondents were dropped from the German sample. Results with Muslim respondents included can be found in Section B in the Supplementary Material. There are no substantial differences. For the Swedish sample, we did not have access to a measure of religious identity. Similar samples drawn from the Swedish population have between 2 and 3 per cent Muslims. If the sample we use contains a similar share, results may include up to 50 Muslim respondents. We would have liked to exclude these respondents from the analysis for the sake of consistency, but we have no reason to believe that results would change.

Research design

The empirical data is collected in three Western European countries where commitment to liberal ideals is believed to be strong, but where we have also seen significant far-right mobilization (eg Bjånesøy, Ivarsflaten and Berntzen Reference Bjånesøy, Ivarsflaten and Berntzen2023): Sweden, Norway, and Germany. In Norway, the experience with a prominent far-right party, the Progress Party (FrP), promoting exclusionary ideas about Muslims dates back to the late 1980s (Jupskås Reference Jupskås2015). In Germany and Sweden, the rise to political influence of far-right parties that portray Muslims as an existential threat is more recent, as we saw with the electoral breakthroughs of the Alternatives for Germany (AfD) in the 2010s and of the Sweden Democrats (SD) in the 2000s (Valentim Reference Valentim2024). Muslims have a significant minority presence in all three countries today, but Muslim communities in Germany, especially of Turkish background, have a somewhat longer history than Muslim communities in Sweden and Norway (Helbling Reference Helbling2012). There are also some notable differences between the countries when it comes to the regulation of majority religions, since the separation of state and church is mandated in the German Basic Law, while in Sweden and Norway, formal separation of church and state is fairly recent, as separation was formalized in 2000 in Sweden and in 2017 in Norway.

In all three countries, we examine the hypotheses empirically in a series of value conflict experiments. The question format in each trial is a variant of a classical tolerance experiment, in that the question is not to agree or disagree with a value, but to agree or disagree to uphold central civil liberties (Stouffer Reference Stouffer1955; Sullivan, Piereson, and Marcus Reference Sullivan, Piereson and Marcus1982). All experiments concern upholding the rights of Muslims to freedom of assembly. The baseline condition in the Public Rally Experiment is anodyne on purpose. It reads as follows:

Some [Norwegian/Swedish/German] Muslims have asked permission to hold a public event to explain Islamic values. How much do you agree or disagree that they should be allowed to hold the event?

In the baseline condition, we expect support for Muslims’ right to assembly to be high for most respondents, and especially among culturally liberal and left-leaning respondents who favor minority inclusion. In the three experimental conditions, we vary the two dimensions of interest independently and jointly, expecting to see reductions in support for Muslims’ civil liberties, and especially strong reductions in the conjunction condition. Along the substantive dimension, we introduce a value conflict to a randomized subset to test H1. In the Public Rally Experiment, we do this by replacing the general reference to ‘Islamic values’ with a term that specifically references conservative religious values, ‘conservative ideas about women’s position in Islam’.

To test H2, the performative utterance hypothesis, we vary whether the religious value is expressed in the form of a communicative or performative utterance. In the public rally example, we randomly assign respondents either to an ‘explain’ or to a ‘preach’ condition. To test H3, both dimensions are altered jointly so that there is a call for adherence to an Islamic tenet at odds with a culturally liberal value. In the example above, the wording in the joint condition becomes:

Some [Norwegian/Swedish/German] Muslims have asked permission to hold a public event to preach conservative ideas about women’s position in Islam. How much do you agree or disagree that they should be allowed to hold the event?

There is an ongoing debate in political science and neighboring disciplines about how to address the replication crisis (eg Camerer et al. Reference Camerer, Dreber, Holzmeister, Ho, Huber, Johannesson, Kirchler, Nave, Nosek, Pfeiffer, Altmejd, Buttrick, Chan, Chen, Forsell, Gampa, Heikensten, Hummer, Imai, Isaksson, Manfredi, Rose, Wagenmakers and Wu2018). Some address the problem through pre-registration of hypotheses. Requiring advance specification on all fronts should increase the robustness of results. But it is not direct evidence of replicability. Sequential factorial designs are therefore our strategy.

Sequential factorial designs have the advantage of reducing the otherwise sharp trade-off between replication and discovery (Ivarsflaten and Sniderman Reference Ivarsflaten and Sniderman2022). Rather than conducting one-off trials either to replicate a previous result or to make a new discovery, the strategy is to develop a repeatable template, a basic wording of the experiment, and to repeat it multiple times. Over a series of experimental trials, new randomized treatments can be introduced, and as importantly, previous ones must be repeated. In this way, at every step in an extended sequence of studies, previous trials can be replicated exactly to make sure that what seemed a discovery is in fact a discovery, while at the same time adding new variations, thus enabling new discoveries. Research thus turns into a continuous process of learning at each step the next best step to take.

Table 1 summarizes the full set of completed trials. It shows that the majority of trials were conducted in Norway, but that critical tests were repeated in Sweden and Germany. The table also highlights that multiple versions of value conflicts were assessed, pitting the right to assembly against gender equality, child-rearing values, and gay rights, respectively. In addition, the specific setting in which Muslims wanted to exercise their civil liberties varied. We asked about the right to assembly, either in the form of holding a public rally, renting a room in a public library, or renting a community house. The Public Rally format was replicated four times; the Public Library format twice. In all, seven independent experimental trials were conducted. In two of the trials, support for the civil liberties of both Christians and Muslims was assessed.

Measures of ideological orientation

All surveys contain two measures of ideological orientation, cultural liberalism-conservatism and left-right self-placement. Cultural liberalism-conservatism is measured through items asking about views on traditional gender roles, preservation of Christian cultural heritage, multiculturalism, law and order, and environmental protection (Hooghe, Marks and Wilson Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002). Based on these items, we generate a Green/Alternative/Libertarian (GAL) – Traditional/Authoritarian/Nationalist (TAN) index. Left-right ideology is measured by the standard self-placement item (Huber Reference Huber1989; Lesschaeve Reference Lesschaeve2017).

The GAL-TAN index provides the primary indicator for purposes of hypothesis-testing, since it is a tailor-made multi-indicator measure of cultural liberalism-conservatism.Footnote 5 The left-right self-placement measure provides a corroborative test and a means to tie results in this paper more closely to previous research that often relies on this conventional measure of ideological orientation. That noted, results by either measure should be expected to be broadly in line since the cultural divide has become more prominent in contemporary politics, and scores on the GAL-TAN index are therefore increasingly likely to inform respondents’ self-placement on the left-right scale.

Results: the public rally sequence

The main sequence of experiments focused on Muslims’ right to assembly and was conducted four times, first in Norway in 2017, then extended and replicated in Sweden and Norway in 2021, and in Germany in 2022. In the baseline condition, respondents were asked whether ‘Muslims should be allowed to hold a public event to explain Islamic values’. In the joint condition testing H3, they were asked whether ‘Muslims should be allowed to hold a public rally to preach conservative ideas about women’s position in Islam’.

The main results are displayed in Figure 1.Footnote 6 The first panel in Figure 1 shows results from the public rally experiment in Norway, the second in Germany, and the third in Sweden. The first panel of Figure 1 shows substantial differences between the experimental treatments. An overwhelming majority of non-Muslim citizens support Muslim minorities’ right to assemble to explain Islamic values (about 69 per cent). Introducing an intra-personal liberal value conflict (H1) or altering the speech-act from communicative to injunctive (H2) cuts support to 39 and 52 per cent, respectively. Those are substantial drops in line with both H1 and H2. However, these drops are dwarfed by the result observed in the joint condition, when changes in both dimensions of the value conflict are combined. In this condition, support decreases to only about 19 per cent, a massive denial of Muslims’ civil liberties.

The second panel of Figure 1 shows results from a follow-up experiment that was fielded in Germany. The same experimental template was used. Key treatments were repeated to test replicability, and one new treatment was added to further probe the meaning and limitations of the previous result. More specifically, the baseline condition was repeated – a meeting to explain Islamic values. So was the substantive liberal value conflict condition – to explain ‘conservative ideas about women’. In the newly added condition, respondents were exposed to two versions of the joint condition. They were either asked, as before, to allow a public event ‘to preach conservative ideas about the position of women in Islam’, or they were asked a variant where the qualifier ‘conservative ideas’ was deleted. This last tweak was made to probe if the joint effect observed in the first trial would also occur without explicitly pointing to conservative ideas about women’s position in Islam, and hence lessening how explicitly stated was the substantive value conflict.

The repeated segments of the experiment replicate. In the reiterated joint condition, we observe a massive drop in support compared to the baseline and to the other conditions. As in Norway, only about 19 per cent of respondents think Muslims should be allowed to assemble to ‘preach conservative ideas about the position of women in Islam’. In addition, we gain a new insight. If the qualifier ‘conservative ideas’ is dropped, more than twice as many support upholding Muslims’ rights. About 45 per cent of respondents support Muslims’ right in Germany to assemble to ‘preach about the position of women in Islam’.

The third Public Rally trial was fielded in Sweden. Results are shown in the third panel of Figure 1. The baseline and joint conditions were repeated exactly as in the two previous trials. In addition, a condition was added to anchor the strong joint condition results observed so far. In the added condition, we wanted to probe if support for Muslims’ right to hold a rally in the joint condition was as low as support for Muslims’ right to gather to promote an alternative to democratic rule, Sharia law.

Again, an overwhelming majority of respondents, on the order of 65 per cent, agree that Muslims should be allowed to hold a public event ‘to explain Islamic religious values’. And again, the outcome is diametrically opposite in the joint condition. Support for Muslims’ right to hold a public rally collapses. Only about 18 per cent agree that Muslims should be allowed to hold a public event ‘to preach conservative ideas about women’. The main results replicate, and, in addition, we gain a new insight. In the joint condition, opposition to holding a public rally is as strong as opposition to a meeting being held in order to ‘promote Sharia law’. Simply put, a proposal to hold a public rally to preach conservative Islamic ideas about women brings about as complete a collapse of support for Muslims’ civil liberties as does a rally to promote an explicitly anti-democratic agenda.

Results part 2: ideological orientation

Why do we observe this volte-face in support for Muslims’ civil liberties? The reasoning underpinning the conjunction hypothesis (H3) suggests that cultural liberals or left-leaning members of the public drive the results. These voters are likely to uphold the rights of Muslims in the absence of conflicts with other liberal values that they also support. We now turn to examining this idea of value conflict on the left. To avoid conclusions based on a single measure, we employ two separate indicators of ideology: left-right self-placement and cultural liberalism-conservatism.Footnote 7, Footnote 8 We focus on the contrast between the baseline and joint conditions.Footnote 9

Figure 2 displays results for the public rally experiment conducted in Norway, Germany, and Sweden by the two measures of ideological orientation. The main pattern is the same across all trials and both measures. Culturally conservative voters and voters who place themselves far to the right on the left-right self-placement scale are unsupportive of Muslims’ civil liberties in both conditions. We want to underline this result, because it is important to research on far-right voters in Europe. Figure 2 shows that voters on the far right oppose the civil liberties of Muslims also in the absence of any substantive conflict with other liberal values and without performative utterances. The larger prevalence of negative stereotypes about Muslims among voters on the far right is one plausible reason for this result. We know that a common prejudice about Muslims in Europe is that they are all conservative zealots (Sniderman and Hagendoorn Reference Sniderman and Hagendoorn2007; Choi, Poertner and Sambanis Reference Choi, Poertner and Sambanis2022a, Reference Choi, Poertner and Sambanis2022b). Another plausible reason for the finding is that voters on the far right are far less likely to support minority inclusion and diversity as liberal democratic values. They favor exclusionary principles and assimilationist policies (Ivarsflaten and Sniderman Reference Ivarsflaten and Sniderman2022) instead.

Figure 2. Cultural liberalism and left-right self-placement, gender equality, Norway, Germany, and Sweden*.

Predicted probabilities of favoring Muslims’ rights.*Question wording and model specifications for the scales are in Section A, Tables A3, A4, and A5 of the Supplementary Material. Results in tabular form for Figure 2 are in Supplementary Material Section D, Tables D1, D2, D4, D5, D7 and D8.

The dramatic results are on the political left. When the issue is allowing Muslims to hold a public rally to explain Islamic values, support is overwhelming on the left. But when the issue is allowing Muslims to hold a public rally to preach conservative Islamic ideas about women’s roles, those on the left do a volte-face. They are as opposed as their counterparts on the right. Cultural liberals do not go quite so far, but the main finding is the same.Footnote 10 Compared to cultural conservatives, cultural liberals drive the result, for they go from being virtually unanimously in favor of Muslims’ rights in the baseline condition to only a minority upholding the rights of Muslims to freedom of expression and assembly in the joint condition. It is to be underlined that the result is virtually identical across studies. In all three countries, those on the left, under pressure, withdraw their support either completely or in great numbers.

Extension and discussion of the main results

-

1. Preaching conservative ideas about how to raise children

Ideas and ideals about child rearing are one of the traditional dividing lines between cultural liberals and conservatives (see eg Feldman and Stenner Reference Feldman and Stenner1997). And it is yet another area where values in Europe, and perhaps particularly in Scandinavia, are changing fast away from traditional, often religiously grounded, family-centric values towards ideals that afford more individual autonomy to children (Gillies Reference Gillies, Richter and Andresen2012; Helland, Križ and Sánchez-Cabezudo Reference Helland, Križ, Sánchez-Cabezudo and Skivenes2018). This change in orientation re-ignites both inter-personal value conflicts between liberals and conservatives and intra-personal conflicts between the liberal values of upholding the civil liberties of conservative religious minorities and liberal child-rearing ideals (see eg Sniderman and Hagendoorn Reference Sniderman and Hagendoorn2007).

We designed an additional experiment to test whether the main results observed above extend to conflicts over how to raise children. In this experiment, respondents were asked whether a group of Muslims should be allowed to rent a local community house to hold a meeting either to ‘discuss conservative ideas about Islamic child-rearing’ or, in the joint condition, they were asked about ‘preaching’ such values. The first two conditions were kept as before; they asked about allowing Muslims to rent the community house to ‘discuss’ or to ‘preach’ ‘Islamic values’.

The results in Figure 3 are strikingly similar to all we have seen before. There is overwhelming support for Muslims’ right to assemble to hold a meeting to ‘discuss Islamic values’. And, as in the previous experiments, when the function of speech at the meeting is ‘to preach’ rather than ‘to discuss’ Islamic values, support drops significantly to about 51 per cent. This is further evidence in line with the performative utterance hypothesis (H2). ‘Discussing conservative ideas about Islamic child-rearing’ is supported at the same level as ‘preaching Islamic values’. In the joint condition, support again reduces dramatically to only about 17 per cent. This amounts to a society-wide withdrawal of support for Muslims’ civil liberties.

-

2. Discrimination: Is it Islam or is it religion?

Discrimination is denying others’ opportunities on the basis of extraneous factors – race, religion, ethnicity, gender, among them (see eg Pettigrew and Taylor Reference Pettigrew, Taylor, Edgar and Rhonda2000; Quillian Reference Quillian2006). Political discrimination is denying others’ civil liberties, ie rights of citizenship, on the basis of extraneous factors.Footnote 11 The issue in this study is the question of public support for Muslim minorities’ civil liberties – of freedom of assembly, of speech, and of religion.

But how far is the withdrawal of support for civil liberties to preach conservative ideas a reaction to Muslims specifically? Given the central role we are assigning professions of religious faith necessarily as performative utterances calling for adherence, it is more than fair to ask whether we observe a reaction to Islam specifically rather than to the two dimensions of value conflict. Is the reaction to Christians the same if they act the same way as Muslims in a Christian-heritage society?

The issue of double standards, at its core, goes to the character of a pluralist democracy (see eg Sniderman Reference Sniderman2017). Just so far as Muslims are not permitted to practice their faith as Christians are permitted to practice theirs, equality under the law is denied. It would be naïve to suppose Muslims will be treated the same as Christians, across the board, even in North Western Europe, where equality tends to be a deeply held value (Adida, Laitin and Valfort Reference Adida, Laitin and Valfort2016; Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten Reference Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten2019). Granted that Christianity no longer occupies the central place it enjoyed in Christian-heritage societies three generations ago, it is also granted that there are versions of Christianity pledged to conservative norms that clash with the contemporary norms of liberal democracies. All the same, Christianity has the advantage of having been part of the cultural-normative furniture in Christian-heritage countries for centuries. The complexities of the question are brought out by two experiments comparing responses to Muslims and Christians preaching conservative ideas in Christian-heritage societies (Adida, Laitin and Valfort Reference Adida, Laitin and Valfort2016).

Discrimination, 1st result

To address the issue of double standards, two experiments comparing support for the right to assemble to preach Muslim and Christian conservative values are brought to bear. In one, the content of the value conflict across religions is not strictly specified. In the other, it is. The more that is left to the imagination, the greater the difference we would expect to see. A Christian heritage society is more likely to give Christians the benefit of the doubt than Muslims (Helbling and Traunmüller Reference Helbling and Traunmüller2020; Choi, Poertner and Sambanis Reference Choi, Poertner and Sambanis2022a).

In the Community House Experiment, the content of the value conflict varied across religions. In one condition, respondents were asked whether Muslims should be allowed to rent a community house ‘to preach conservative ideas about child-rearing in Islam’. In another condition, respondents were asked if Christians should be allowed to rent a community house ‘to preach conservative Christian ideas about child-rearing’. Conservative ideas about child-rearing may not be the same across religions, and so this experiment does not, strictly, hold the substantive content of the value conflict constant. We find a way to avoid this problem in subsequent trials, and this does influence results in a telling way. In the study at hand, the function of speech (the speech act dimension) is constant across groups. In both instances, it is injunctive – to preach, to call for adherence.

Figure 4 displays levels of support for Muslims and Christians to hold a community meeting to preach on behalf of conservative child-rearing values. The difference in responses to Muslims and Christians testifies to a double standard. Only some 17 per cent think Muslims should be allowed to rent a community house to preach conservative ideas about child-rearing in Islam. About twice as many support the right of Christians to rent a community house to preach conservative Christian ideas about child-rearing. This is clear evidence of discrimination, even if support for the right to assemble for the Christian group is also low (at 39%).

Our intuition, though, is that this result has an ironic twist. Cultural conservatives, out of their commitment to traditional values, fail to support the civil liberties of Muslims, we have seen many times over. But because of their commitment to traditional values, we hypothesize that cultural conservatives discriminate in favor of Christians. Figure 5 displays the results of the relevant traditional values.Footnote 12 They show that those who have traditional values are more likely to back the right to assembly of Christians than of Muslims if they want to preach conservative ideas about child rearing. Cultural conservatives, though all in all less supportive of civil liberties than cultural liberals, provide a lift to the right to gather together in support of conservative child-rearing ideas – provided that they are Christian.

-

3. Preaching that homosexuality is a sin

Our final extension of the main finding takes the form of two Public Library Experiments. In these, an additional central liberal value is introduced, equal treatment based on sexual orientation (gay rights). One purpose of these experiments is to test whether the conjunction hypothesis (H3) also extends to this case. The main design principle, accordingly, is again to vary the substantive and speech-act dimensions of the value conflict independently and jointly. In the second experiment, we again compare responses to Muslims and Christians, but this time, the conservative content to be preached across the two religions is the same – homosexuality is a sin.

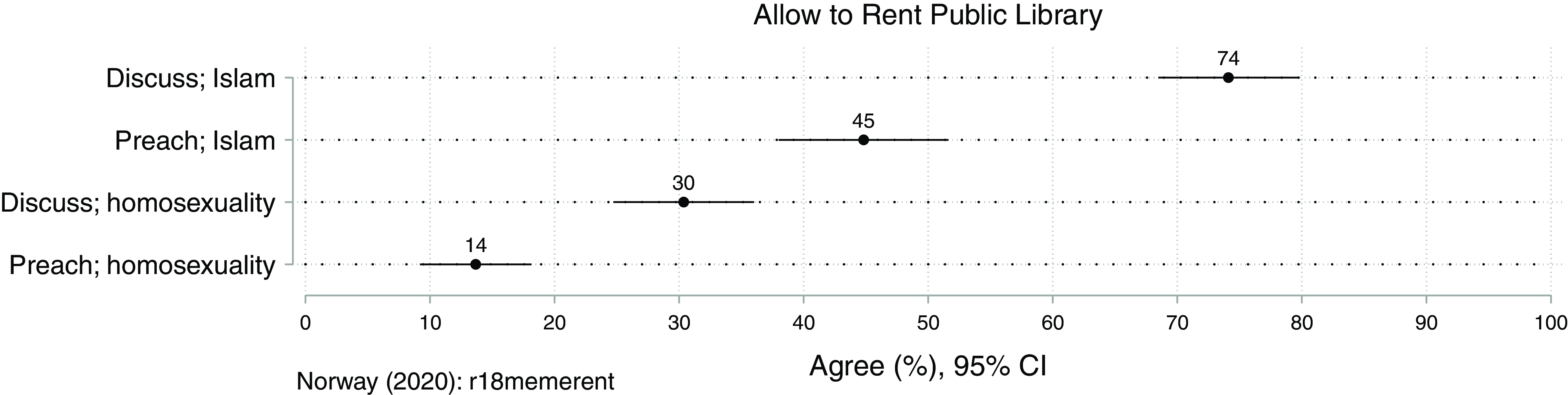

In the baseline condition of the first experiment, respondents are asked whether a group of Norwegian Muslims should be allowed to rent a room in a public library for a meeting ‘to discuss Islamic values’. In the performative utterance condition, respondents are asked to approve renting the room if the purpose of the meeting is ‘to preach Islam as the one true faith’. For the value-conflict variations, the wording in this trial is purposefully explicit. Rather than asking about conservative ideas, we ask if Muslims should have the right to assemble either ‘to discuss’ or ‘to preach’ ‘traditional Islamic views of homosexuality as a sin’. Again, the expectation is that in the joint condition, when both dimensions put heavy pressure on respondents with liberal values, support for Muslims’ civil liberties is likely to be minuscule.

Figure 6 replicates and extends the previous results. If the speech-act at the meeting is communicative and the value conflict is not pressed, support is overwhelming, at about 74 per cent. But if the speech-act is prescriptive, ‘to preach Islam as the true faith’, support drops substantially to about 45 per cent. This is again in line with the performative utterance hypothesis (H2).

Figure 6 further shows that if the substantive content of the meeting is to discuss Islamic doctrine that homosexuality is a sin, only about 30 per cent believe that Muslims should be allowed to rent a room in a public library. Cutting even this small number by a significant amount would be eye-catching. Still, this is what we find in the joint condition. Less than half, only about 14 per cent, support a meeting to ‘preach traditional Islamic views of homosexuality as a sin’. Renting a room to preach Islamic values about homosexuality being a sin is denied at the same level as holding a public rally to preach conservative ideas about women in Islam or promoting sharia laws.

Discrimination, 2nd result

The explicit formulation of the content of the conservative ideas in Islam in the Public Library Experiment provides an opportunity to keep constant a feature that varied in the child-rearing trial. Conservative ideas about child-rearing in Islam are not necessarily the same as conservative Christian ideas about child-rearing. But preaching that homosexuality is a sin is the same regardless of religion. And what is more, in the context under study, Norway, the main Christian church (Den norske kirke) no longer preaches that homosexuality is a sin. This is the result of remarkable mobilization and development within the church and in society at large, which, among other things, led to a unanimous communiqué issued by all the church’s bishops in 2022, 50 years after same-sex relations had been decriminalized in Norway. The communiqué recognized that the church’s attitudes and communication ‘through the years have caused many human beings profound harm and pain’, and that ‘on this occasion, we wish to express our recognition and joy that the church has many homosexual and lesbian members and employees and confirm their contribution to the community’.Footnote 13 Liberalization of church doctrine and practice began in the 1970s following de-criminalization. Same-sex marriages have been allowed in the main Christian church of Norway since 2016.

As we saw above, Christians’ preaching in favor of conservative child-rearing was not explicitly formulated as calls for adherence to values that are more conservative than those advanced by the main Christian church. Christians preaching that homosexuality is a sin is qualitatively different for this reason. And what stands out in the results shown in Figure 7 is the near complete collapse of support for both Muslims’ and Christians’ right to assemble to preach such religious ideas. No more than one in every six agree that either has a right to rent a room in a community facility to preach that homosexuality is a sin. And as Figure 8 shows, this is because right-leaning and left-leaning citizens both refuse the right of Christians and Muslims to rent a room for the purpose of preaching that homosexuality is a sin.

Discussion and conclusion

It has been long and well-established that cultural liberals are more supportive of the rights of minorities than are cultural conservatives. The results of multiple experiments in multiple countries presented in this article, however, demonstrate that culturally liberal voters will – in specified circumstances – consistently defect. And the defection is massive. Cultural liberals and those on the left approach or line up right alongside cultural conservatives and those on the right in opposing Muslims’ civil liberties. The problem-puzzle at the center of this study is why.

Part of the answer is content – what we have labeled the substantive dimension of value conflict. Cultural liberals are internally conflicted when liberal values concerning gender equality, gay rights, and child rearing ideals come into conflict with the liberal value of protecting the citizenship rights of Muslim minorities. But substantive conflict, by itself, does not turn cultural liberals en masse from supporters into opponents of Muslims’ civil liberties. Something more is required.

The ‘something more’, we have shown, is bound up with the nature of religious practice per se. Assertions of religiously grounded values are performative utterances, instances of when saying is also doing, namely, calling for adherents to comply with a requirement of faith. It is just because religious injunctions are not mere communications but commands to do this and not to do that, that there is a double conflict – both about the content and about the speech act. The result, our results demonstrate, is to exacerbate conflicts with religiously grounded values, so much so that the largest number on the left will line up with the largest number on the right in opposition to the core democratic rights of Muslims.

In his work on polyarchy, Dahl insisted on ‘a distinction between sometimes confusing usages of the terms “democracy”: one to describe a goal or ideal, an end perhaps never achieved and possibly not even fully achievable in actuality’, and polyarchy, ‘the distinguishing features of the actual political systems commonly called “democratic” or “democracies” in the modern world’ (Dahl Reference Dahl1984: 228). The distinction matters, Dahl contended, because the democratic ideal is not static: it is responsive to changes in circumstances and makeup of polyarchies over time.Footnote 14

So it is here. Democratic ideals are pluralistic; liberty and equality are only two of them. And each is itself pluralistic, equality perhaps especially. New versions of value conflicts are therefore built into democratic advances. Hence, our focus on conflicting claims for equal standing and respect for Muslims and for women and gays. With time, political ingenuity and, perhaps especially, prosperity, conflicting value claims can be reconciled, minimized, or evaded. But when value conflicts are fresh, choices must be made.

One part of the public opinion patterns we have documented is reassuring. Despite the hostile public debates that have been raging in all societies under study on Muslims, and given how the far right has seized on portrayals of Islam as a conservative religion that does not support women’s rights and homosexuality, it is telling that we find that cultural liberals uphold support for Muslims’ right to assembly in most conditions in our study. This is evidence of resistance, among a considerable section of the wider public, to narratives that for decades now have tried to portray all Muslims as a threat to societal progress towards gender equality and gay rights. Consistent with previous studies (eg Ivarsflaten and Sniderman Reference Ivarsflaten and Sniderman2022), the results presented here showed that voters on the far right distinctively perceive Muslims generically as a threat. Our contribution to this larger debate is to call out the special challenge, at the current stage of democratic development, of accommodating religiously grounded speech. Most cultural liberals, faced with calls for Muslims to adhere to conservative Islamic values, join cultural conservatives in opposition to Muslims’ rights to freedom of religion and expression.

A final lesson to take away from this study is the insight gained by examining when Muslims are treated differently and worse than Christians by the general public in questions about civil liberties. The results on this point are suggestive rather than dispositive, but we believe that what they suggest is crucial. When Christians call for adherence to conservative tenets that are directly at odds with values that the larger society, and even the main Christian church, now endorses, opposition to their right to freedom of expression is as common as with Muslims. But when there is some room for interpretation, preaching conservative ideas in Christianity is given the benefit of the doubt, especially by cultural conservatives. Conservative ideas in Islam are, by contrast, not given the benefit of the doubt. Preaching conservative ideas in Islam is treated as beyond the pale by all.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1475676526100759

Data availability statement

Data available here: Bjånesøy, Lise; Esaiasson, Peter; Ivarsflaten, Elisabeth; Paul M. Sniderman, 2026, ‘Replication Data for “Preaching Conservative Ideas: The Speech-Act Theory of Value Conflict”’, https://doi.org/10.18710/8XX2LW, Dataverse.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the European Research Council for generous funding for data collection through the ERC-CoG-grant INCLUDE #101001133. The authors are deeply grateful for the many colleagues who have provided feedback to earlier versions of the manuscript at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, at the General Conference of the European Consortium of Political Research, and at invited talks at seminars and workshops at the universities of Vienna, Aarhus, Bergen, Stanford, Stockholm, the European University Institute, and North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The authors alone are responsible for the data analysis and conclusions.

Funding statement

The Study is supported by the ERC Consolidator Grant#101001133.

Competing interests

There are no competing interests

Ethical statement

All studies have been formally approved to be in compliance both with the human-subject guidelines of the authors’ home institutions and with the relevant national and EU regulations on research ethics and data protection.