Introduction

The Nerja Cave, located in the Sierra de Almijara, in the village of Maro (Nerja, Málaga, Spain) constitutes one of the most relevant chronostratigraphic and archaeological sequences of the Western Mediterranean. Remains from the Late Pleistocene until the Middle Holocene evidencing human activities have been recovered (Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2008).

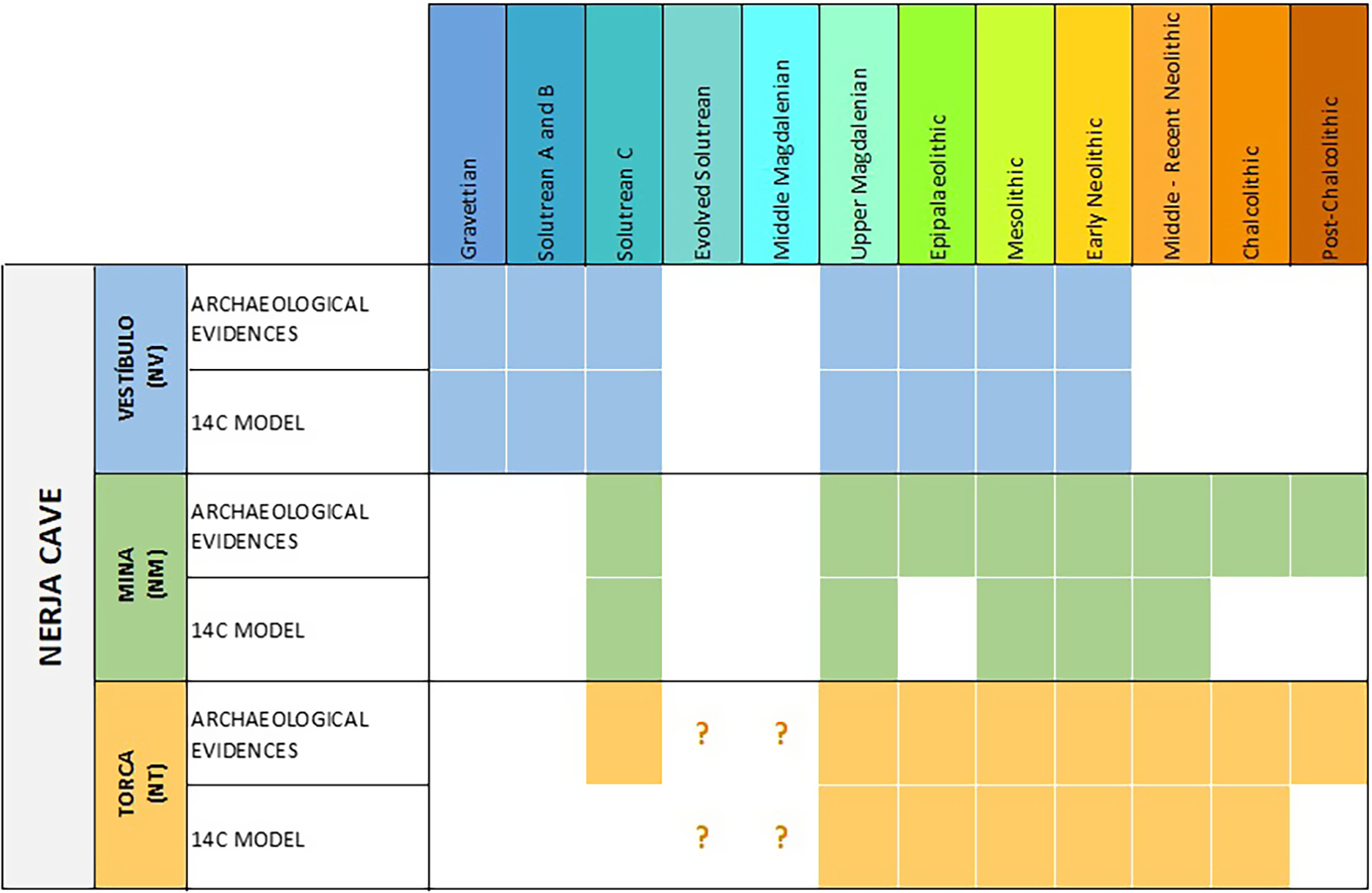

The external chambers of the cave are made up of two subcircular sinkholes and a large mouth compartmentalized into different chambers—the Vestíbulo chamber (NV), the Mina chamber (NM) and the Torca chamber (NT)—which constitute a long archaeological sequence with evidence from the Gravettian, the Solutrean, the Magdalenian, the Epipalaeolithic, the Mesolithic, the Neolithic, the Chalcolithic and later periods (Jordá Pardo et al. Reference Jordá Pardo, Aura Tortosa, Rodrigo and Badal2003) (Figure 1). Since the second half of the 20th century, a variety of research teams have performed excavations and studies of materials. Among them, the geoarchaeological, technoeconomic, bioarchaeological, molecular, radiometric and cave art studies are particularly important.

Figure 1. Map of the location of the Nerja Cave within the Iberian Peninsula. Topography of the NC with details of the external chambers and excavation area (Modified version of García Borja et al. Reference García Borja, Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo and Salazar García2014).

In 1960, Professor Pellicer Catalán sent the first carbonized seed sample from the Nerja Cave to be dated. To date, 179 radiocarbon dates have been obtained from the external chambers, the Upper galleries, and the Lower galleries. In this paper, we focus on the radiometric dating samples from the stratified archaeological contexts of the external chambers of the Nerja Cave (Aguilera Aguilar et al. Reference Aguilera Aguilar, Medina Alcaide and Romero Alonso2015; Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, García Borja, García-Puchol, Badal García, Pérez Ripoll, Pérez Jordá, Pascual Benito, Carrión García and Morales Pérez2013b; Fernández et al. Reference Fernández, Sanchidrián, Jiménez-Brobeil, Remolins, Díaz-Zorita, Subirà, López-Onaindía, Maroto, Roca and Román2020; García Borja et al. Reference García Borja, Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo and Salazar García2014; Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2006; Sanchidrián Torti and Márquez Alcántara Reference Sanchidrián Torti, Márquez Alcántara, Sanchidrián Torti, Márquez Alcántara and Fullola Pericot2005). The rest of the dates derive from cross dating of CaCO3 from speleothems, cave art panels from the Upper and Lower galleries, and carbon samples collected from the surface and concavities linked to points of light in deep chambers (Medina Alcaide et al. Reference Medina Alcaide, Cristo Ropero, Romero and Sanchidrián Torti2012; Medina Alcaide et al. Reference Medina Alcaide, Sanchidrián Torti and Zapata Peña2015; Medina Alcaide et al. Reference Medina Alcaide, Cabalín, Laserna, Sanchidrián Torti, Torres, Intxaurbe, Cosano and Romero2019; Medina Alcaide et al. Reference Medina Alcaide, Vandevelde, Quiles, Pons-Branchu, Intxaurbe, Sanchidrián Torti, Valladas, Deldicque, Ferrier and Rodríguez2023; Sanchidrián Torti and Márquez Alcántara Reference Sanchidrián Torti and Márquez Alcántara2003; Sanchidrián Torti et al. Reference Sanchidrián Torti, Márquez Alcántara, Valladas and Tisnérat-Laborde2001; Sanchidrián Torti et al. Reference Aura Tortosa and Jordá Pardo2012; Sanchidrián Torti et al. Reference Sanchidrián Torti, Valladas, Medina Alcaide, Pons-Branchu and Quiles2017; Valladas et al. Reference Valladas, Pons-Branchu, Dumoulin, Quiles, Sanchidrián Torti and Medina Alcaide2017).

Using only the corpus of the radiocarbon dates of the Nerja Cave (from now on NC), Bayesian chronological modeling has been carried out to correlate the chronocultural phases of the three chambers. This type of approach, comprising both radiometric and statistical studies, provides information of immense value for the knowledge of the Prehistory of the South of the Iberian Peninsula.

Stratigraphic context

This archaeological sequence for the NC was established using information provided by fieldwork between 1959 and the present day. The excavations in these chambers were led by a variety of directors. Those led by Dr. Jordá Cerdá in the NV and NM chambers and Dr. Pellicer Catalán in the NM and NT chambers are of particular importance (Hopf and Pellicer Català Reference Hopf and Pellicer Català1970; Jordá Pardo Reference Jordá Pardo and Jordá Pardo1986; Jordá Pardo et al. Reference Jordá Pardo, Aura Tortosa and Jordá Cerdá1990; Pellicer Català Reference Pellicer Català1990; Pellicer Català and Acosta Martínez Reference Pellicer Català, Acosta Martínez, Pellicer and Acosta1997).

The geoarchaeological, radiometric and technoeconomic studies enabled the lithostratigraphic and archaeological correlation of the NV and NM chambers (Jordá Pardo Reference Jordá Pardo and Jordá Pardo1986). Here, 12 different stages of sedimentation were recorded, which correspond to 7 lithostratigraphic units and various discontinuities related to erosion processes, for the Late Pleistocene and the Early and Middle Holocene occupation of the cave (Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2008, Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2009; Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Pérez Ripoll, Jordá Pardo, García Borja, Morales Pérez, García-Puchol, Avezuela Aristu, Pascual, Pérez Jordá, Tiffagom, Gijaba Bao and Carvalho2010c; Aura Tortosa and Jordá Pardo Reference Aura Tortosa and Jordá Pardo2014). These erosional actions were documented in most of the contacts between the stratigraphic levels of the NV and NM chambers (Figure 2) (Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, Pérez Ripoll, Badal García, Morales Pérez, Avezuela Aristu, Tiffagom, Jardón and Mangado2010b; Jordá Pardo Reference Jordá Pardo and Jordá Pardo1986; Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2009). Besides, the most recent intervention in the NM 2008 of the Mina chamber (Aguilera et al. Reference Aguilera Aguilar, Medina Alcaide and Romero Alonso2015), we do not have information on the geoarchaeological studies published. Due to this, we do not know the correlation between this intervention and the interventions made by Dr. Jordá Cerdá in the NM and NV.

Figure 2. Summary table of the sequence identified and occupation phases in the Vestíbulo (A), Mina (B) and Torca (C) chambers. Modified version of Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2008; Aura Tortosa et al. 2010b. Data have been added from Aguilera Aguilar et al. Reference Aguilera Aguilar, Medina Alcaide and Romero Alonso2015 (A and B), and Fernández et al. Reference Fernández, Sanchidrián, Jiménez-Brobeil, Remolins, Díaz-Zorita, Subirà, López-Onaindía, Maroto, Roca and Román2020; Pellicer Català and Acosta Martínez Reference Pellicer Català, Acosta Martínez and Jordá Pardo1986, Reference Pellicer Català, Acosta Martínez, Pellicer and Acosta1997; Pellicer Català Reference Pellicer Català1990; Sanchidrián Torti and Márquez Alcántara Reference Sanchidrián Torti, Márquez Alcántara, Sanchidrián Torti, Márquez Alcántara and Fullola Pericot2005 (C).

There are no geoarchaeological studies of the NT chamber. It preserves records of the Late Pleistocene and the Holocene. There is a tentative proposal for the NT chamber trenches (Pellicer Català and Acosta Martínez Reference Pellicer Català, Acosta Martínez and Jordá Pardo1986, Reference Pellicer Català, Acosta Martínez, Pellicer and Acosta1997; Pellicer Català Reference Pellicer Català1990; Sanchidrián Torti and Márquez Alcántara Reference Sanchidrián Torti, Márquez Alcántara, Sanchidrián Torti, Márquez Alcántara and Fullola Pericot2005). However, the differences between the excavation methodologies do not allow us to establish a clear correlation.

In this study, we have proposed a first correlation between the three chambers and the different excavation trenches (see Figures 2 and 7). The differences between chambers and archaeological excavations have been considered in its application. Consequently, we have carried out some tests and approaches that have allowed us to detect correlation problems, both stratigraphic and chronocultural. It has provided us with information on the different uses and occupations of the cave by human groups. We have been able to confirm different depositional events of archaeological remains for the chambers, and to distinguish a greater number of cultural phases and different human occupation.

Material and methods

14C samples

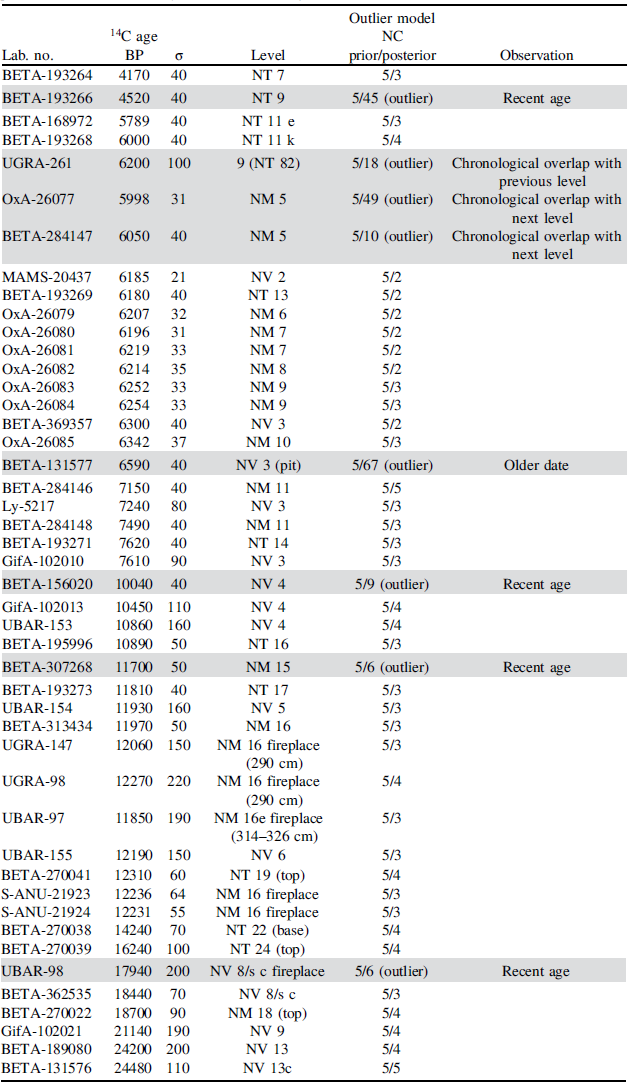

We compiled all the 14C samples for the external chambers of the NC between 28 and 1.7 ka BP uncalibrated (between 30 and 3.7 ka cal. BP). There are samples which fall outside this period in other spaces. As for analysis, a database was created. It compiles the most relevant information about the samples, as well as the archaeological contexts to which they are associated (see Table 1).

Table 1. Collection of radiocarbon dates of the NC (NV, NM and NT chambers). Information on the full collection of dates (104) used in this project. The samples which did not pass the validity test and/or which have no known lab code (52) are marked in grey (see Table S1 of the supplementary information). The rest of the samples were used to build the chronological models (marked in white in this table). The table gives information about their archaeological position, sample type, method of analysis, age, and standard deviation, laboratory identification and cultural attribution. The reference includes the sample data and its context

The radiocarbon dates constitute essential information for the determination of the chronological framework. Yet, the use of radiocarbon dating results poses a range of different problems. These include the analysis of intrusive samples, inaccurate relationships with the dated event or the shaping of apparent contexts, the analysis of contaminated samples, the effect of post-depositional processes, palimpsests or the “old wood effect,” the marine reservoir effect in samples or collection problems, among others (Ascough et al. Reference Ascough, Cook and Dugmore2005; Banks et al. Reference Banks, Bertran, Ducasse, Klaric, Lanos, Renard and Mesa2019; Bernabeu Aubán Reference Bernabeu Aubán2006; Bernabeu Aubán et al. Reference Bernabeu Aubán, Barton and Pérez Ripoll2001; Bowman Reference Bowman1990; Hajdas et al. Reference Hajdas, Ascough, Garnett, Fallon, Pearson, Quarta, Spalding, Yamaguchi and Yoneda2021; Jordá Pardo et al. Reference Jordá Pardo, Mestre i Torres and García Martínez2002; Pettitt and Zilhão Reference Pettitt and Zilhão2015; Sanchidrián Torti and Márquez Alcántara Reference Sanchidrián Torti and Márquez Alcántara2003; Wood Reference Wood2015; Zilhão Reference Zilhão1993, among other papers).

Given these issues, a validity test has been performed to check the correspondence between the value of the radiocarbon dates, their stratigraphic position and the archaeological context (Banks et al. Reference Banks, Bertran, Ducasse, Klaric, Lanos, Renard and Mesa2019; Mestre i Torres Reference Mestre i Torres1995, Reference Mestre i Torres2000, Reference Mestre i Torres2003, 2008). As part of this process a series of prerequisites has been used (Cuesta et al. Reference Cuesta, Jordá Pardo, Maya and Mestre i Torres1996; Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2008; Mestre i Torres Reference Mestre i Torres1995; Mestre i Torres and Nicolás i Mascaró 1997). These are an analytical (this encompasses precision and accuracy prerequisite), physical-chemical and archaeological (representativity) prerequisites. Moreover, these have already been used in previous works and other sites (Álvarez-Fernández et al. Reference Álvarez-Fernández, Jordá Pardo, Arias, Bécares Pérez, Martín-Jarque, Portero, Teira and Douka2021; Banks et al. Reference Banks, Bertran, Ducasse, Klaric, Lanos, Renard and Mesa2019; Extrem-Membrado Reference Extrem-Membrado2020; Jordá Pardo et al. Reference Jordá Pardo, Mestre i Torres and García Martínez2002; Jordá Pardo and Maestro González Reference Jordá Pardo, Maestro González, Aura Tortosa, Álvarez Fernández and Jordá Pardo2023, among others). The samples are not compliant with these prerequisites have failed the validity test and have, therefore, been discarded (see SI Table 1 in the Supplementary information).

The first prerequisite is the technical or analytical dimension in which the sample must meet certain conditions of accuracy and precision, as described in SI Table 1.

Accuracy is based on the correct relationship between the calendar date attributed to the dated material and the radiocarbon date obtained by the laboratory (Mestre i Torres Reference Mestre i Torres2003). It is essential that the laboratory effectively measures the 14C content and performs a correct elimination of the contamination of the sample, which in turn, will depend on the indications made by the archaeologist (Mestre i Torres and Nicolás i Mascaró 1997). The application of sample pretreatment protocols and ultrafiltration methods help to improve the accuracy of the samples (Bird et al. Reference Bird, Ayliffe, Fifield, Turney and Cresswell1999; Bowman Reference Bowman1990; Higham et al. Reference Higham, Jacobi and Bronk Ramsey2006). The accuracy requirement discards all dates of the Gakushuin Laboratory (GaK) and one data from UBAR. Regarding laboratory accuracy, we have rejected all dates of the Gakushuin Lab (GaK) (18 samples, see Table S1), as, firstly, it has been observed that the dates provided by this laboratory present the problem of being older than the dated archaeological contexts and as, secondly, their protocols are qualitatively poor (Blakeslee Reference Blakeslee1994; Carballo Arceo and Fábregas Valcarce Reference Carballo Arceo and Fábregas Valcarce1991; Cuesta et al. Reference Cuesta, Jordá Pardo, Maya and Mestre i Torres1996). The UBAR-344 sample was discarded because the laboratory could not date it more accurately due to the intrinsic factors of the sample (see Table 1 in this paper and Table S1). Specifically, they were unable to determine the Asn value of this sample, as well as the unexpected values for the net count rate, the decision and detection limit, among other observations of the sample, which generated low precision and made it impossible to complete the age calculation and determine the standard deviation of the sample. For this reason, they could only report that this sample was older than 9000 years BP. The isotopic results of charcoal and bone samples also contribute to the laboratory quality control. For this study, we only have the isotopic values of 18 samples, so we cannot evaluate it wholly.

The precision of radiocarbon age refers to the time margin in which the true radiocarbon date is found (Cuesta et al. Reference Cuesta, Jordá Pardo, Maya and Mestre i Torres1996). Radiocarbon age is expressed as a Gaussian distribution, which is composed of the BP data and the standard distribution of this data. The precision of the radiocarbon age is greater when the standard deviation is smaller, as this results in a narrower Gaussian distribution associated and a more limited possible time span for the true radiocarbon date (Mestre i Torres Reference Mestre i Torres2000, Reference Mestre i Torres2003). A significant number of the dates from the external chambers are 14C conventional measurements and have a standard deviation, which ranges from 20 to 4800 years. However, the validity of the precision dating may be conditioned by the availability of measurements, the precision of other samples at the same level, other precision problems that may arise, and other possibilities (Mestre i Torres Reference Mestre i Torres2000). In previous studies, the precision criterion was established at 400 years (Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2008). However, the precision requirement for radiocarbon measurements is that their standard deviation should be as small as possible. In order to ensure precision, we have validated all measurements with standard deviations of less than 250 years, in line with recent studies (Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Extrem-Membrado and Jordá Pardo2020; Extrem-Membrado Reference Extrem-Membrado2020). We have used this standard deviation for two reasons. The first is to eliminate the problems of representativity derived from samples with very high deviations since their Gaussian distribution exceed the chronologies of the cultural phases to which these dates are linked. Other researchers have also determined that the degree of validity of samples with high accuracy can be linked to the relationship of that dating to its analogs (Mestre i Torres Reference Mestre i Torres2000), so some samples have been discarded because their level analogs have small outliers. Some of these samples have taxonomical and life identifications (see Table S1).

The second prerequisite would be the physical/chemical dimension. It refers to the capacity of the material to yield a valid radiocarbon date. Most of the samples are made out of organic material and satisfy this requirement. The Miytilus edulis samples discussed in another paper (Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2008) can pose problems because these samples are a complex combination of organic (terrestrial or marine plants) and inorganic components (hydrosphere, lithosphere or atmosphere), as well as the possibility that the samples can be affected by the reservoir effect, the recrystallisation of carbons, among other options (Bowman Reference Bowman1990; Mestre i Torres Reference Mestre i Torres2003). We detected problems with Mytilus sp. shells when comparing them with their equivalent obtained from six pine seeds at the same levels of NV. The results of Mytilus sp. are concentrated between 10450 and 12550 BP, while those of Pinus pinea are between 7610 and 24730 BP (GifA-209–GifA-023). The Pinus pinea samples are consistent with stratigraphy and archaeological materials. Conversely, the Mytilus sp. samples exhibited incongruence with the stratigraphy and archaeological remains. These differences may have a physico-chemical causality and therefore, all Mytilus sp. dating has been discarded.

And third prerequisite is the archaeological dimension. It refers to the degree to which the radiocarbon date is representative of the archaeological context that is to be dated. Thirteen samples have also been discarded due to either contradictory information regarding their identification, alteration, intrusion or the absence of information regarding their context or incomplete inspection (see Table S1):

-

dates of human bones from the NV (Fernández Domínguez et al. Reference Fernández Domínguez, Cortés Sánchez, Pérez-Pérez and Turbón Borrega2004), as they show uncertain archaeological contexts, as well as having been subjected to thermal alterations after their extraction from the site (Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2008).

-

3 dates have been considered as percolations of Magdalenian materials at the top of Solutrean levels and are consistent with the alterations caused by the burials excavated in 1962 (Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2006) (see Table S1).

-

A sample of Ovis-Capra has also been questioned and was considered as a possible sample of goat that was deposited naturally in the cave (Martins et al. Reference Martins, Oms, Pereira, Pike, Rowsell and Zilhão2015). The faunal study has not considered this option in the results of the taphonomical study (García Borja et al. Reference García Borja, Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo and Salazar García2014, Reference García Borja, Salazar García, Jordá Pardo, Pérez Ripoll and Aura Tortosa2018). Problems in the preservation of collagen were detected during the pretreatment process (0.1% collagen yield) (García Borja et al. Reference García Borja, Salazar García, Jordá Pardo, Pérez Ripoll and Aura Tortosa2018). These elicited the application of non-standard or experimental methods for sample measurement (Brock et al. Reference Brock, Higham, Ditchfield and Bronk Ramsey2010).

-

7 samples have been labeled anomalous due to discrepancies between the archaeological remains and cultural phase indicated by the results (Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, García Borja, et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, García Borja, García-Puchol, Badal García, Pérez Ripoll, Pérez Jordá, Pascual Benito, Carrión García and Morales Pérez2013; García Borja et al. Reference García Borja, Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo and Salazar García2014, Reference García Borja, Salazar García, Jordá Pardo, Pérez Ripoll and Aura Tortosa2018; González Gómez et al. Reference González Gómez, Sánchez-Sánchez and Villafranca-Sánchez1987; Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2008; Sanchidrián Torti and Márquez Alcántara Reference Sanchidrián Torti, Márquez Alcántara, Sanchidrián Torti, Márquez Alcántara and Fullola Pericot2005). Some of these samples yield ages that are older than the context in which they are documented. Others yield the opposite.

We also discarded samples due to lack of different types of information. We have discarded 1 sample from the NV and 3 samples from the NM because we lacked detailed information about the excavation process and its correlation with the other trenches. The stratigraphic information about the cuts and levels excavated in the NV sample is unknown. As for the NM samples, these present a profile associated with the interventions made by Pellicer in 1985 and 1986, for which the stratigraphic information is also unknown as well as the details of the profile intervention and its relation to the rest of the interventions for the chamber.

The sample originating from a burial has also been discarded due to the lack of a detailed examination of the marine diet, just as indicated in a recent study (Martínez-Sánchez et al. Reference Martínez-Sánchez, Bretones-García, Valdiosera, Vera-Rodríguez, López Flores, Simón-Vallejo, Ruiz Borrega, Martínez Fernández, Romo Villalba and Bermúdez Jiménez2022). Additionally, other problems associated to the application of the reservoir effect such as the spatio-temporal variation of marine carbon or marine upwelling effect must be considered. These and other factors have been extensively identified and analyzed (Broecker Reference Broecker2009; Lanting and van der Plicht Reference Lanting and van der Plicht1998; Monge Soares et al. Reference Monge Soares, Gutiérrez Zugasti, González-Morales, Matos Martins, Cuenca-Solana and Bailey2016; Stuiver and Braziunas Reference Stuiver and Braziunas1993; Stuiver and Polach Reference Stuiver and Polach1977). Hence, and also due to the fact that the sample has been calibrated utilising both a reservoir effect obtained through an average ΔR for the Mediterranean region and a specific ΔR based on the sample closest to the site (Fernández et al. Reference Fernández, Sanchidrián, Jiménez-Brobeil, Remolins, Díaz-Zorita, Subirà, López-Onaindía, Maroto, Roca and Román2020; Gómez-Puche and Fernández-López de Pablo Reference Gómez-Puche and Fernández-López de Pablo2024; Martínez-Sánchez et al. Reference Martínez-Sánchez, Bretones-García, Valdiosera, Vera-Rodríguez, López Flores, Simón-Vallejo, Ruiz Borrega, Martínez Fernández, Romo Villalba and Bermúdez Jiménez2022), these issues discarding it to avoid incorporating uncertainties into the chronometric modeling of the Nerja Cave.

Finally, we also discarded a sample for which there was no lab code (see Table S1).

Bayesian models

As shown, 52 dates were discarded after the validation test (see Table S1), yielding a total of 52 samples to model. We calibrated all these dates using the program OxCal 4.4. (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey1995, Reference Bronk Ramsey2009a), the IntCal20 curve for the Northern Hemisphere (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Austin, Bard, Bayliss, Blackwell and Bronk Ramsey2020) to create Bayesian chronological models based on the archaeological information and the dates of the external chambers of the NC (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey1995, Reference Bronk Ramsey2009a; Buck and Juárez Reference Buck, Juárez, Barceló and Morell2020; Lozano Medina and Capuzzo Reference Lozano Medina, Capuzzo, Barceló and Morell2020). All the dates are within a 95.4% high probability distribution (HPD), reported in cal. BP.

The differences among the chambers studied—regarding available stratigraphic and archaeological information—show the different levels of knowledge available for each chamber. Due to this, first, we have created a model for each of the chambers that grouped radiocarbon dates into Phases (NV, NM and NT). The individual models for each chamber consider the stratigraphic information and the sequential organization of their depositions in levels. These are phase models based on the sequence for which we have the most complete information for each chamber. And second, we have created an integrated phases model which brings together the models for the three chambers (NC), taking into account the dates accepted for previous models (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2008, Reference Bronk Ramsey2009a). In these models, we include the dates that could not be included in the individual chamber models because we do not have information of the possible correlation between the deposits of each intervention.

The models report the start and the end of each phase with the command Boundary. This command enables the identification of an event that could not been possible to date directly and the estimation of its probability distribution based on the known dates of the preceding and subsequent phases (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009a). The boundaries allow us to make an approximation to the duration of the hiatuses or to periods of time for which we do not have information due to erosive actions between the contact of stratigraphic levels. Furthermore, we have used the Span command, to probabilistically estimation the duration of each phase in the NC model. The Span function can be used to determine the duration of groups of events that could have occurred in each phase. We have used the Span command because we consider it to be more appropriate and a source of more accurate results for our data.

Most archaeological sites have been shown to consist of different depositional events or actions. In the case of our site, we do not have detailed studies on the number of depositional events, and therefore, on the palimpsest that make up the different stratigraphic levels identified in each intervention (Karkanas and Goldberg Reference Karkanas and Goldberg2018: 196). In some cases, we have information that is related to the minimum spatial archaeological unit that shows some homogeneity (Barceló and Bogdanovic Reference Barceló, Bogdanovic, Barceló and Morell2020), being the case of some fireplaces, burials or other things. In some studies, the chronological position of the depositional event has been mentioned to be close to the isotopic event, although with some delay between them (Andreaki et al. Reference Andreaki, Barceló, Antolín, Gassmann, Hajdas, López-Bultó, Martínez-Grau, Morera, Palomo and Revelles2022; Barceló and Bogdanovic Reference Barceló, Bogdanovic, Barceló and Morell2020). In this study, all the radiocarbon samples represent different isotopic events (except in the case of NM 9, which corresponds to 2 dates originating from the same sample). These are grouped in different stratified levels in the phases model for each chamber and according to their archaeological cultural attribution in the NC phases model. A general “t” type test of the Outlier_Model was performed on all models to quantify the probabilistic degree to which samples agree within the overall model structure and its components (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009b). We have assigned a prior 5% probability to each sample of being an outlier and considered acceptable those samples with a posterior probability equal to or less than 5. Also, we use the R_Combine command for two dates of the same sample (in NM 9 level). In these cases, the SSimple “s” type Outlier_Model was used (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009b; Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk Ramsey, Dee, Lee, Nakagawa and Staff2010).

The samples that were analyzed underwent AMS and conventional 14C measurement have been used for the models. Some of the conventional radiometric results consist of charcoal aggregates from a single level or from fireplace contexts identified during the excavation. In some phases, we used these samples because we did not have AMS samples for that phase or level. In other cases, other samples were available, and we wanted to observe whether the conventional dating samples were adequate for that level and phase. The outlier model test has identified some of these samples as inconsistent with the rest of the samples from the same phase or level. This inconsistency is likely due to ageing or rejuvenation of the phase, which may have occurred as a result of sample aggregation. Consequently, we did not use the samples identified as outliers by the outlier model for the NC model, which combines the models of each chamber.

Results

We propose a two-stage approach to the Bayesian modeling is optimal for this site due to the characteristics of the excavation process, stratigraphy, and sedimentation, as well as the known archaeological information. This procedure comprises, firstly, modeling each chamber independently and, secondly, developing a general model encompassing all the external chambers of NC. In this section, we present the individual models for each of the chambers. With this done, we test the individual models against a general phases model for the site. The results for all the chronological models are displayed in the supplementary material (Tables S 2.1.–5.2.) and in Figures 3–6.

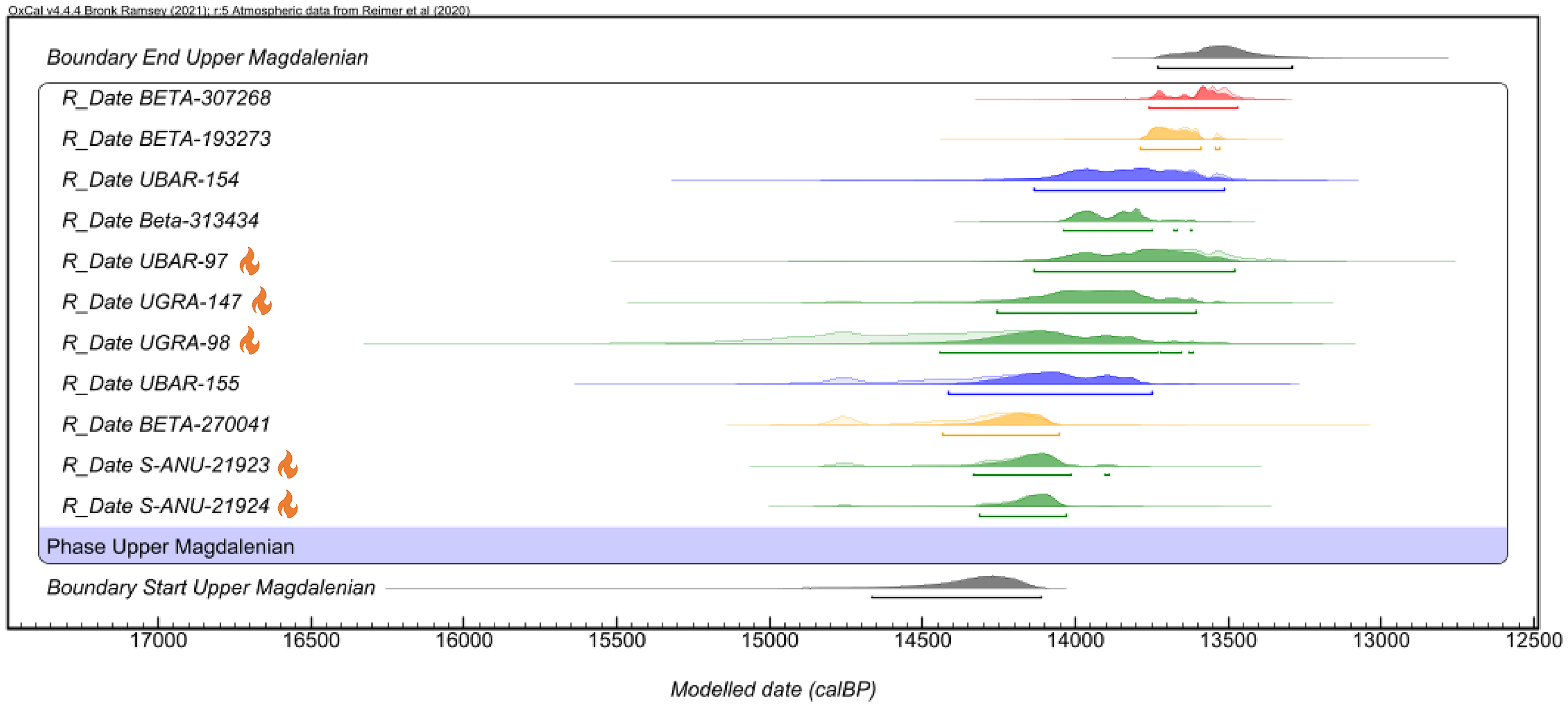

Figure 3. Bayesian chronological model of the Nerja Vestíbulo chamber (NV). Each of the dates included in the model with the command R_Date is represented in blue and the outliers in red.

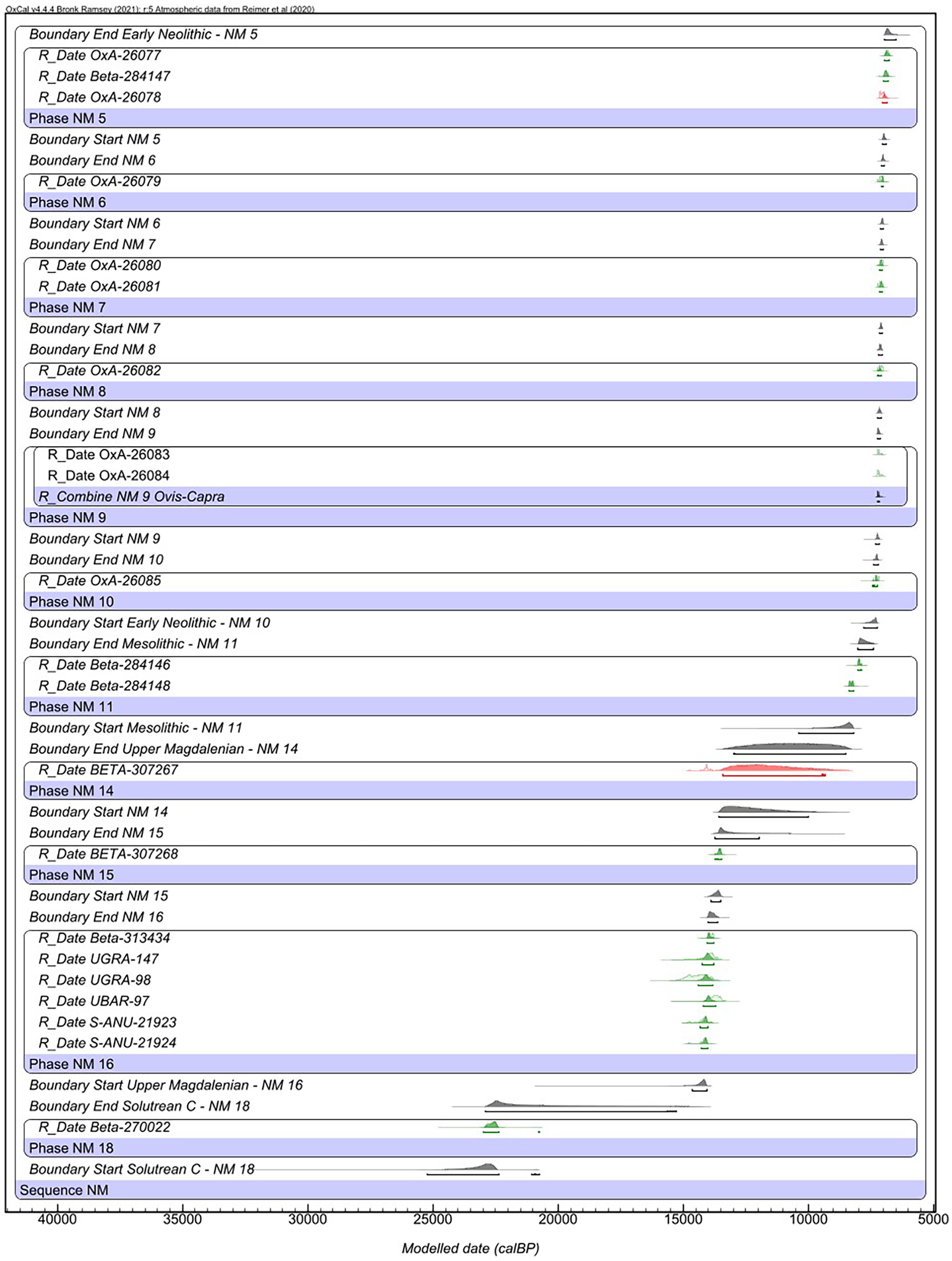

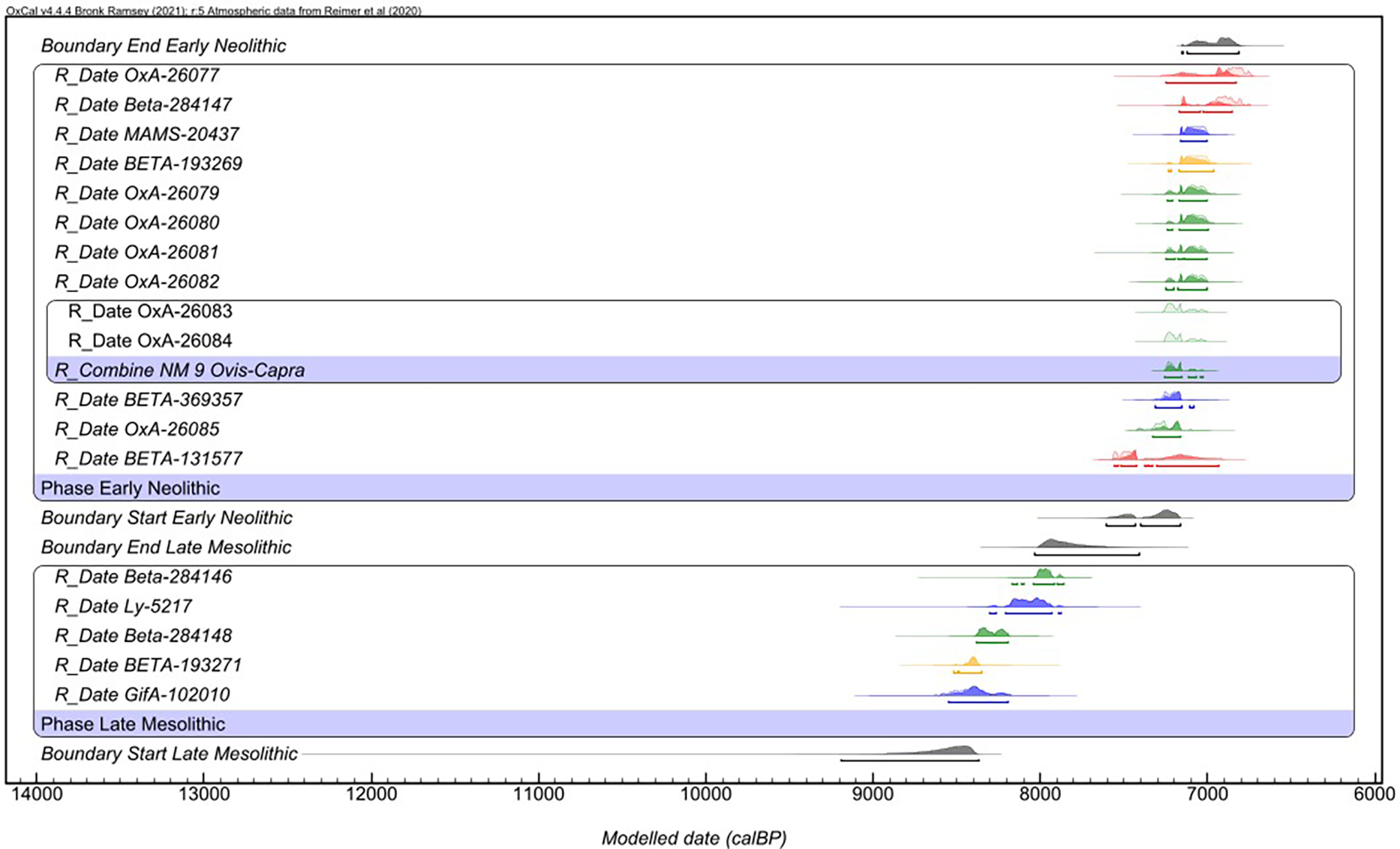

Figure 4. Bayesian chronological model of the Nerja Mina chamber (NM). The dates which have been included in the model are marked in green and the outliers in red.

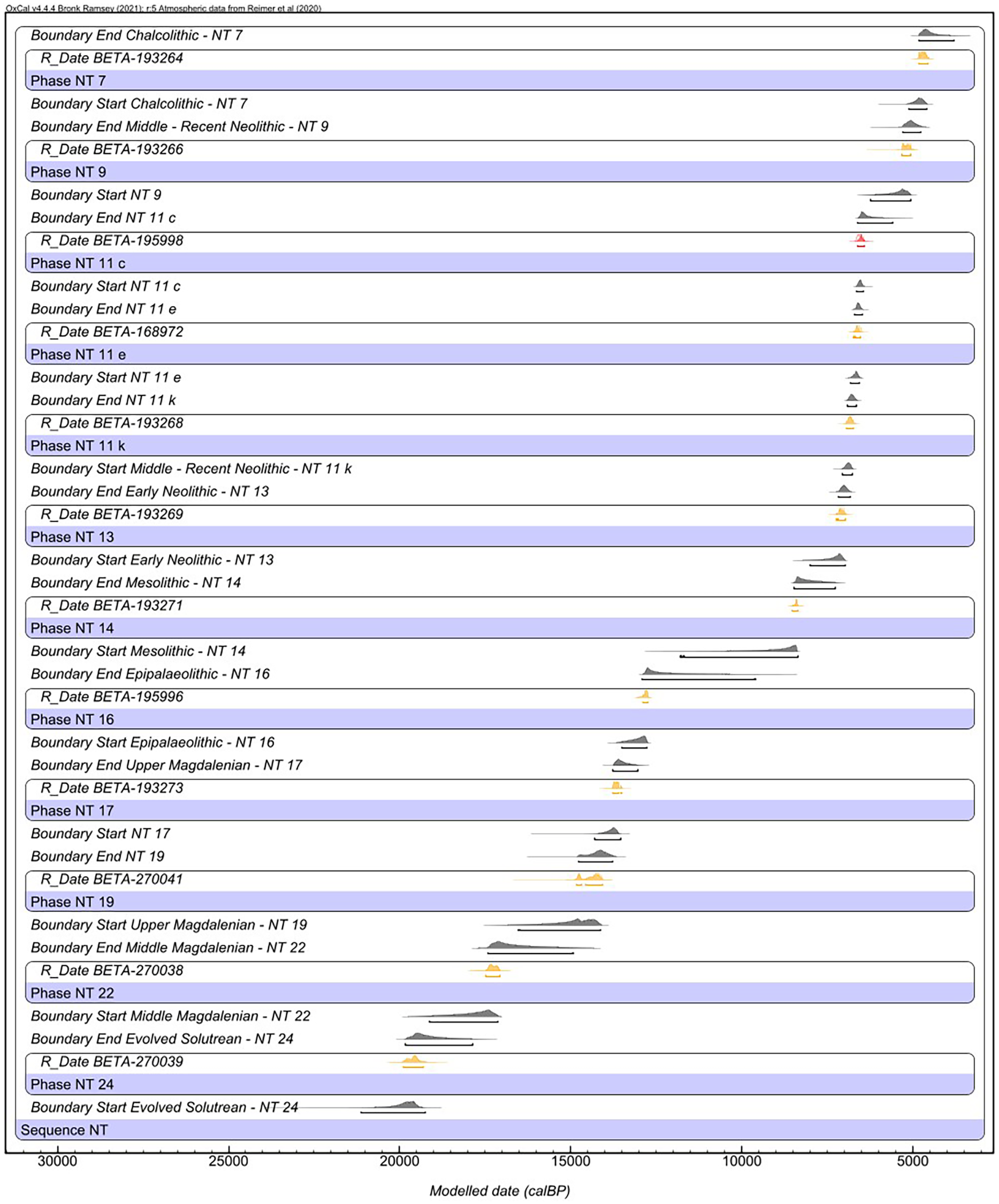

Figure 5. Bayesian chronological model of the Nerja Torca chamber (NT). The dates which have been included in the model are marked in orange and the outliers in red.

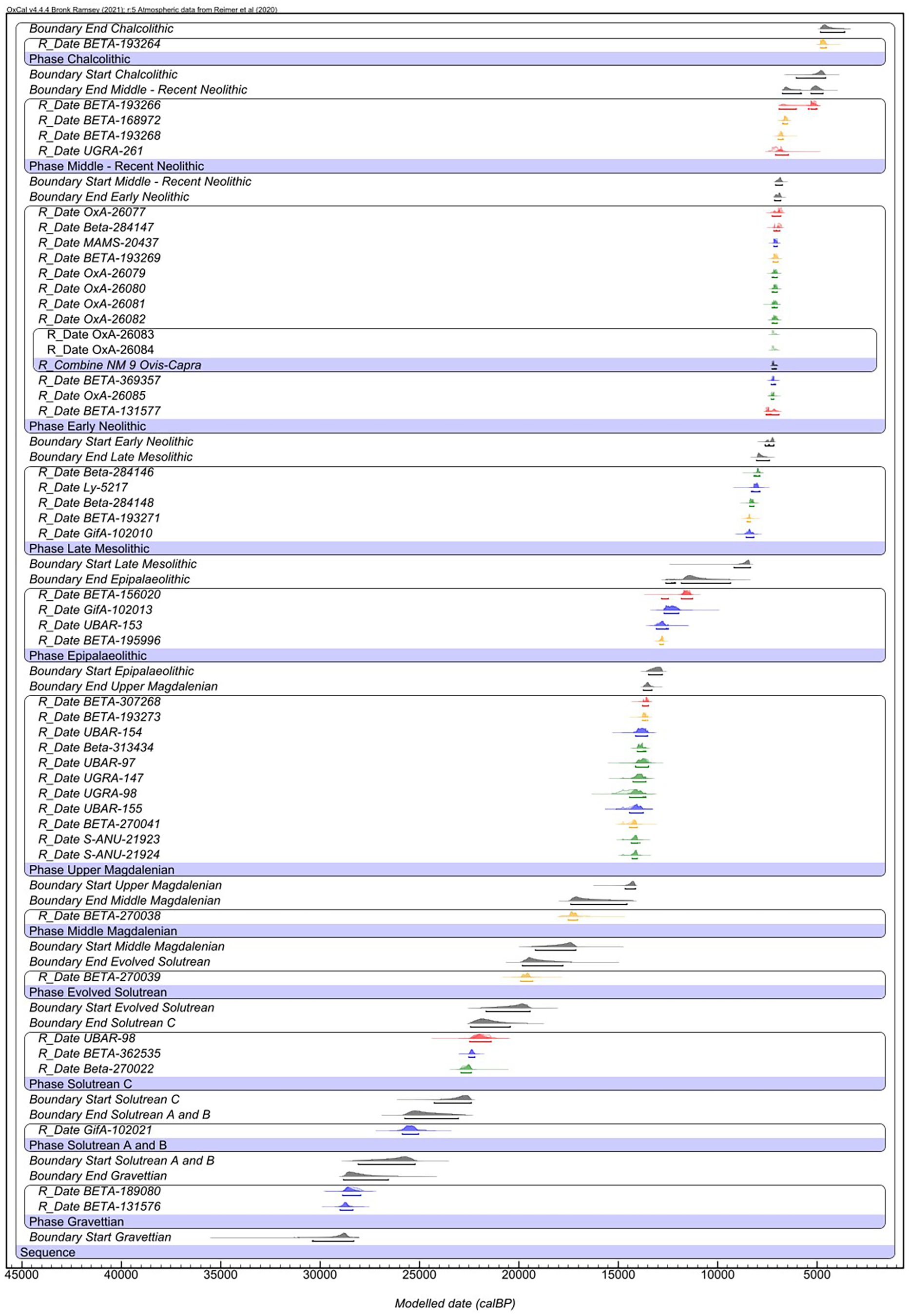

Figure 6. General Nerja Cave model (NC). The NV samples are marked in blue; the NM samples are marked in green; the NT samples are marked in orange; a sample labeled as outlier during the modeling process is marked in red.

The Vestíbulo chamber (NV)

The NV chamber model included 18 samples from excavations performed by Jordá between 1982 and 1987 (see Table S2). The 14C samples of the NV are different isotopic events, that are grouped in different levels shaped by different depositional actions. This model comprises 13 phases (Figure 3), which correspond to the different levels, that are based on the stratigraphic information published in previous papers (Jordá Pardo Reference Jordá Pardo and Jordá Pardo1986; Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2009; Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, Pérez Ripoll, Badal García, Morales Pérez, Avezuela Aristu, Tiffagom, Jardón and Mangado2010b), and linked to different archaeological phases defined from the study of the materials recovered in the chamber (Figure 2). We have a radiometric data and archaeological remains for the NV chamber that are related with the Gravettian, Solutrean, Upper Magdalenian, Epipalaeolithic, Mesolithic and Early Neolithic phases (Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2009; Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, Pérez Ripoll, Badal García, Morales Pérez, Avezuela Aristu, Tiffagom, Jardón and Mangado2010b). These archaeological phases are indicated in the model at the start or the end of the Boundaries of the phases which correspond to the stratigraphic sequence proposed for the Jordá excavations (Figure 3).

Furthermore, the model also shows the periods for which we do not have valid information. There are significant differences between these periods without valid information (see Table S2), as some represent centuries and others represent millennia of absence of information about the human occupation of the cave. In some case, these information gaps can be related to the erosional hiatuses identified during the excavation process and sedimentary studies (Jordá Pardo Reference Jordá Pardo and Jordá Pardo1986; Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2009). In addition to these stratigraphy gaps, there are also the levels documented during the excavation for which we do not have valid radiocarbon information. This happens in the case of the NV 12, NV 10 and NV 1 levels. The application of the Outlier Model in the NV model identified 3 samples as possible outliers (Table 2 ). This affected the availability of samples for the NV 11 and NV 7 level and reduced the number of samples for the NV 2 level. This samples were not used for the NC model (Table 2), after the revision the dating and previous information.

Table 2. The samples indicated by the outlier_model of the NV are shown in gray. The prior and posterior values obtained by the NV model are reported

The Mina chamber (NM)

The NM chamber model has been constructed with 21 dates of the Jordá and Pellicer excavations (see Table S3). It was not possible to include the samples of the Aguilera trench, because we lacked detailed information about the correlation with the excavations carried out by Jordá Cerdá, as we have explained in the previous section.

This model has been constructed with 11 phases (Figure 4) corresponding to the different levels, which are based on the stratigraphic information and the archaeological phases proposed for the study of the archaeological materials (Jordá Pardo Reference Jordá Pardo and Jordá Pardo1986; Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2009; Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, Pérez Ripoll, Badal García, Morales Pérez, Avezuela Aristu, Tiffagom, Jardón and Mangado2010b). We have radiometric data and archaeological remains for the NM chamber that are related with the Solutrean, Upper Magdalenian, Mesolithic and Early Neolithic phases (Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2009; Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, Pérez Ripoll, Badal García, Morales Pérez, Avezuela Aristu, Tiffagom, Jardón and Mangado2010b). We indicate the archaeological phases in the Boundaries of the different levels of the interventions carried out by Jordá in the NM chamber (Figure 4).

As in the NV, differences are observed in the time periods for which we do not have valid information for the NM chamber (see Figure 4 or Table S3). Two aspects characterise the NM. Firstly, the identification of different erosive contacts between levels of the digs performed by Jordà (Figure 2) (Jordá Pardo Reference Jordá Pardo and Jordá Pardo1986; Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2009). Secondly, there is a lack of valid samples of the NM sequence, as in the case of the NM 19, NM 13, NM 12 and the levels of the Middle Neolithic until Chalcolithic. The Outlier_Model identified 2 samples as possible outliers (Table 3), that affect the only valid sample for the NM 14 level and reduced the availability samples for the NM 5 level.

Table 3. Samples discarded (in gray) by the Outlier_Model of the NM. The prior and posterior values obtained by the outlier models for each model are shown

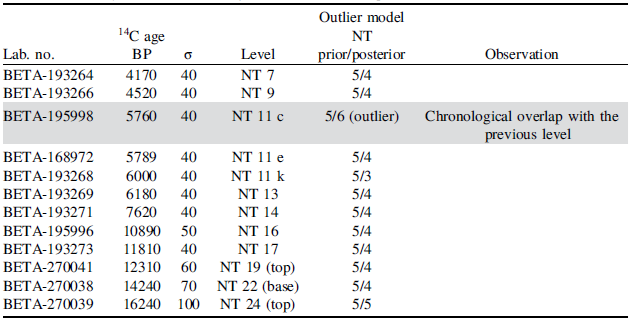

The Torca chamber (NT)

The NT chamber model has been derived from the 12 dates of the southern profile recovered in 2004 (Sanchidrián Torti and Márquez Alcántara Reference Sanchidrián Torti, Márquez Alcántara, Sanchidrián Torti, Márquez Alcántara and Fullola Pericot2005) (see Table S4). The NT model uses 12 phases (Figure 5) corresponding to the different levels, based on the available information (Sanchidrián Torti and Márquez Alcántara Reference Sanchidrián Torti, Márquez Alcántara, Sanchidrián Torti, Márquez Alcántara and Fullola Pericot2005). As has already been mentioned, we have just a single preliminary stratigraphic description, but this is not based on geoarchaeological studies or on a detailed description of the archaeological materials associated with the dates. However, the radiometric data and the described levels are related with the Evolved Solutrean, the Middle and Upper Magdalenian, the Epipalaeolithic, the Mesolithic, the Early Neolithic, the Middle-Recent Neolithic and the Chalcolithic phases (Pellicer Català and Acosta Martínez Reference Pellicer Català, Acosta Martínez, Pellicer and Acosta1997; Sanchidrián Torti and Márquez Alcántara Reference Sanchidrián Torti, Márquez Alcántara, Sanchidrián Torti, Márquez Alcántara and Fullola Pericot2005), that are indicated in the Boundaries of the levels (Figure 5).

There is no data about erosive contacts between levels, and we do not have dates for NT 23, NT 21, NT 20, NT 18, NT 15, NT 12, NT 10, NT 8 and NT 6 up to the first level studied for the profile (Figure 2). For the rest of the levels, we have 1 date (Table S4). The application of the Outlier Model in the NT model reported a potential outlier sample (Table 4).

Table 4. Samples discarded (in gray) for the Outlier_model of the NT. The prior and posterior values obtained by the outlier models for each model are reported

General model of phases of the Nerja Cave

Now that the chronology of each chamber has been set out, we now present the general joint model for all the chambers (Figure 6) (see Table 5 and Table S5). The 45 dates accepted for the individual models have also been used as well as 1 sample of another intervention that could not be previously correlated. We have not incorporated the samples that are identified as potential outliers in the individual models. The samples were grouped into phases according to their cultural attribution.

Table 5. Samples discarded (in gray) for the Outlier_Model of the NC model. The prior and posterior values obtained by the outlier models for each model are shown

Many samples—from the NV, NM, and NT chambers—are linked to the Upper Magdalenian and the Early Neolithic phases. There are fewer samples linked to the Mesolithic, but also from all 3 chambers. There are also other periods for which solely one sample has been documented. This is the case for the Solutrean A and B with a single sample from the NV chamber and the Evolved Solutrean, Middle Magdalenian and Chalcolithic with a sample from the NT chamber for each one.

The Outlier_Model has identified 8 samples as possible outliers (Table 5). These include 1 from the Solutrean C, 1 from the Upper Magdalenian, 1 from the Epipalaeolithic, 3 from the Early Neolithic, and 2 from the Middle-Recent Neolithic. The BETA-131577 discarded sample constitutes the first evidence from the Early Neolithic of the NC. It is an AMS sample on a fragment of Ovis aries, recovered from the NV chamber, from a pit linked to the Archaic Early Neolithic (García Borja et al. Reference García Borja, Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo and Salazar García2014; Martínez Sánchez et al. Reference Martínez Sánchez, Gámiz Caro, Vera Rodríguez, Pardo-Gordó, Gómez-Bach, Molist Montaña and Bernabeu Aubán2020). The Outlier_Model also points to other samples as a possible outlier for the end of the Early Neolithic, due to the chronological overlap with the next phase. The same applies to the oldest sample from the Middle-Recent Neolithic, which has been identified as a potential outlier because it overlaps with some samples from the previous phase. The Outlier Model also identifies 1 sample from the Solutrean C, Epipalaeolithic and Middle-Recent Neolithic as a possible outlier due to its recent chronology compared to the other samples from each phase.

The Bayesian chronological modeling built from the individual models for the chambers, the stratigraphy and the technological and typological studies, consists of 11 phases (see Figure 6 and Table S5). These correspond to the following archaeological phases; the Gravettian, the Solutrean A and B, the Solutrean C, the Evolved Solutrean, the Middle Magdalenian, Upper Magdalenian, the Epipalaeolithic, the Late Mesolithic, the Early Neolithic, the Middle-Recent Neolithic and the Chalcolithic (Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2009). Some phases are present in all the chambers and other phases are exclusively present in just one. Similarly, the spans of the archaeological phases are uneven between chambers.

The first phase is the Gravettian (see Figure 6 and Table S5), for which the model estimates a span of 0 to 718 years, due to the limited amount of data. The following phase, the Solutrean A and B, happens after a period for which there is no available information. We only have one date, and it conditions the duration of said phase (Span: 0-5). Once more, after a period of insufficient information, the Solutrean C has been modeled and is bestowed a possible extension of the most relevant phase through the modeling of 3 samples from different chambers (Span: 40–1240).

After this period, the Evolved Solutrean and the Middle Magdalenian phases have been included in the model, which are characterized by having only 1 sample, both originating from the NT. It is for this reason that the model frames the phases in boundaries of great periods of information deficits and conditions the estimated duration of these (Span: 0–5). In contrast with previous phases, the Upper Magdalenian (Start: 14667–14113 cal. BP. End: 13730–13293 cal. BP) is characterized by being one of the phases with the greatest amount of valid radiocarbon data. Although this phase has numerous samples, the model evidence that there is a chronological proximity between some samples. That yields a shorter duration than for other phases for which we have a fewer number of samples (Span: 405–949). The Epipalaeolithic is preceded by a period for which there is no information (see Table S5). For this phase we have 3 samples that evidence a marked chronological distance between them. The Outlier Model proposed a possible outlier for the more distance sample of this level. This is why the model poses a dispar duration for it (Span: 206–1698).

After a period without information, samples from the 3 chambers yield a duration for the Late Mesolithic has been modeled (Start: 9188–8365 cal. BP. End: 8030–7411 cal. BP) with a possible expansion of more than 300 years (Span: 339–643). The following phase is the Early Neolithic, which starts after a short hiatus for which there is no information. For this phase, we have more than 10 samples from the 3 chambers. These samples show considerable chronological proximity. Correspondingly, the model proposes a potential duration for the phase of between 64 and 641 years, after which there is a short period with no information. The Middle-Recent Neolithic is the subsequent phase. The model proposes a disparate duration due to the integration of two stages of the Neolithic and for the consideration of 2 samples as possible outliers (Span: 0–1945). The last phase, also after a period of information deficit, is the Chalcolithic, for which we only have 1 sample. This limits the possible expansion of the phase (Span: 0–5).

Every phase is delineated by the boundaries given by their start and end, among which we detect time differences in the hiatuses between phases for which we have no radiometric information. These hiatuses display diverse durations. However, there is a trend of longer periods of no information for the boundaries among the first phases of the Late Pleistocene occupations, from the Gravettian to the start of the Mesolithic. In contrast, the occupations associated with the Holocene display shorter hiatuses of information deficit, from the Mesolithic until the Chalcolithic. In similar fashion to the individual models made for each chamber, some of the boundaries have been linked to erosive contacts between the sequence levels of each chamber or the lack of radiometric information for certain levels (Jordá Pardo Reference Jordá Pardo and Jordá Pardo1986; Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2009). But these information vacuums can, arguably, also be linked to other factors. These include periods of decreased occupation or partial or total abandonment of the cave or chambers. Other factors could be not fully reaching the lowest part level in many of the pits and excavation sectors. Questions linger over the first occupations in NM and NT, both in relation to their chronology and their archaeological phase.

Discussion

The general Nerja Cave model on the regional scale

The model presents differences regarding the occupation of the cave because the chambers were not always used simultaneously, and this aligns with some differences in the lithic and osseous assemblages and the organic remains that were identified in the different chambers (Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, Pérez Ripoll, Morales Pérez, García-Puchol, González-Tablas Sastre and Avezuela Aristu2009, Reference Aura Tortosa, Pérez Ripoll, Jordá Pardo, García Borja, Morales Pérez, García-Puchol, Avezuela Aristu, Pascual, Pérez Jordá, Tiffagom, Gijaba Bao and Carvalho2010c). Furthermore, we observed differences when comparing the occupation periods proposed by the model with the archaeological materials recovered in each chamber (Figure 7). Some archaeological evidence associated with some phases of the NM and NT chambers were not reflected in the general model because we do not have valid radiocarbon samples for these phases in these chambers. We could see these differences in the case of the Epipalaeolithic, Chalcolithic and Post-Chalcolithic of NM, and in the case of the Solutrean C and Post-Chalcolithic of NT.

Figure 7. Comparison between the material archaeological evidence and the chronological model according to the distribution in the different chambers and cultural attribution by phases.

Currently, the archaeological remains and radiocarbon information establish the first human occupation in the NV chamber during the Gravettian. We have 2 acceptable radiocarbon dates from the NV chamber which indicate different occupation moments in this phase, supported by the archaeological remains that suggest short episodes alternating with the presence by hyena groups (Arribas Herrera et al. Reference Arribas Herrera, Aura Tortosa, Carrión García, Jordá Pardo and Pérez Ripoll2004). The activity associated with the Gravettian human groups occurred at some point during this technocomplex (Figure 6, Table S5). For this phase, lithic and osseous tools have been documented, among which a barnacle pendant is of particular note (Avezuela Aristu et al. Reference Avezuela Aristu, Álvarez-Fernández, Jordá Pardo, Aura Tortosa, Baron and Kufel-Diakowska2011). This period is documented in the region at sites such as Bajondillo (Bj-10) (Cortés Sánchez Reference Cortés Sánchez2007a) and probably in Cueva del Higueral and the Cueva de la Pileta, sites with preliminary stratigraphies (Cortés Sánchez and Simón Reference Cortés Sánchez and Simón2007; Giles Pacheco et al. Reference Giles Pacheco, Gutierrez López, Santiago Pérez, Mata Almonte, Sanchidrián and Simón1998), and/or some decontextualized or unknown collections belonging to the sites of Gorham’s, Zafarraya, Zájarra II or Serrón (Cortés Sánchez Reference Cortés Sánchez2007b).

The Solutrean A and B are identified only in the NV chamber. We only have 1 date for the Solutrean A (Date calibrated: 25861–25089 cal. BP. Table S5), which is linked to the recovery of unifacial foliaceus pieces and the permanence of certain Gravettian features. It possibly corresponds to the Gravettian–Solutrean transition. Bifacial working and Solutrean retouch are documented subsequently (Solutrean B), but we do not have any dates for this phase. After a hiatus of erosion, the Solutrean C has been described in the NV and NM. The human activity could have taken place at some events related with the Solutrean C phase (Figure 6, Table S5). The NM chamber has a date that matches this phase, but we do not know the archaeological materials associated to it. Almost synchronous with this date, the activity in the NV chamber starts. Unifacial points, microgravettes and shouldered points have been recovered among the lithic productions from Solutrean C (Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo and Fortea Pérez2006).

Unifacial pieces associated with the Solutrean A could be related to level Bj-9 of Bajondillo (Cortés Sánchez Reference Cortés Sánchez2007a), although they have recently been attributed to the Full Solutrean (Calle Román Reference Calle Román2019). The Middle and Upper Solutrean phases are found in different stratified collections such as Cueva Ambrosio (levels IV and II), and perhaps Higueral de Valleja, Bajondillo (6-8) and Gorham’s Cave (4a) among others (Aura Tortosa and Jordá Pardo Reference Aura Tortosa and Jordá Pardo2012; Cortés Sánchez Reference Cortés Sánchez2007a; Ripoll López Reference Ripoll López1986; Ripoll López et al. Reference Ripoll López, Muñoz Ibáñez and Martín-Lerma2015).

Next, the Evolved Solutrean and Middle Magdalenian are identified though only in the NT chamber (Sanchidrián Torti et al. Reference Sanchidrián Torti, Medina Alcaide and Romero2013). These phases have been identified using a radiocarbon date from each one of them (Figure 6, Table S5). The paucity of dates available for these phases is such that only an event can be discerned within the temporary interval of that particular period. Even so, it is important to point out that materials characteristic of the Evolved Solutrean and the Middle Magdalenian have not been recognized in other areas of the cave. A review of the archaeological materials of levels 22 to 24 of the NT chamber would be helpful in the clarification of the existence of these phases in the NT sequence.

From the Upper Magdalenian onwards, concurrent human presence of the three chambers has been documented; parallel occupations of the external chambers are sustained discontinuously—due to the existence of erosion hiatuses—until the end of the Early Neolithic. For the Upper Magdalenian phase, there are several acceptable radiocarbon samples with chronological proximity between them (Figure 6, Table S5). This indicates a recurrent occupation of the space since different depositional events have been identified through the study of several fireplaces in the NM chamber and other remains in the NV and NT chambers (Figure 8, Table S5). Among the recovered objects, the lithic productions are oriented to the elaboration of backed armatures. Osseous industries are characterized by short and thin doubles points, needles and barbed points (Aura Tortosa Reference Aura Tortosa1995). This period gains relevance in the region since it is stratified in different enclaves such as El Pirulejo and Malalmuerzo. To these should be added the sites around Cala del Moral such as Hoyo de la Mina, Cueva de la Victoria Higuerón, and Complejo Humo (Álvarez-Fernández et al. Reference Álvarez-Fernández, Agirre-Uribesalgo, Alcover Tomàs, Aura Tortosa, Avezuela, Carriol, Fernández-Gómez, Jordá Pardo, Marlasca and Martín-Vallejo2022; Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Vadillo Conesa, Jordá Pardo, Bea, Domingo, Mazo, Montes and Rodanés2021; Such Reference Such1920).

Figure 8. Dates from the Upper Magdalenian in the NC. NT dates are marked in orange; NM dates are marked in green; NV dates are marked in blue.

Archaeological materials linked to the Epipalaeolithic have also been recovered in the three chambers, despite the fact the NM chamber is not displayed in the model because there are no valid 14C samples (Figure 7). The radiocarbon results indicate different deposition in the NV and NT chamber (Figure 6, Table S5). In both the NV and the NM, the continuity of osseous work has been noted, represented by short double thin points, some flat points, chisels and needles. Lithic productions have a reduced presence of backed armatures and an increased showing of scrapers, truncations and notches (Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, Pérez Ripoll, Morales Pérez, García-Puchol, González-Tablas Sastre and Avezuela Aristu2009, Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, Pérez Ripoll, Badal García, Morales Pérez, Avezuela Aristu, Tiffagom, Jardón and Mangado2010b, Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, Pérez Ripoll, Badal García, Tiffagom, Morales Pérez, Avezuela Aristu and De La Rasilla Vives2013a), as well as a relevant ensemble of macrolithic industry, among which carved pebbles stand out (Aura Tortosa and Jardón Reference Aura Tortosa, Jardón, Sanchidrián, Márquez and Fullola2006). In the coastal province of Málaga, remains linked to this technocomplex have been documented from Hoyo de la Mina (Such Reference Such1920), Higuerón, Cueva Victoria (Álvarez-Fernández et al. Reference Álvarez-Fernández, Agirre-Uribesalgo, Alcover Tomàs, Aura Tortosa, Avezuela, Carriol, Fernández-Gómez, Jordá Pardo, Marlasca and Martín-Vallejo2022; Fortea Pérez Reference Fortea Pérez1973; Jordá Pardo and Maestro González Reference Jordá Pardo, Maestro González, Aura Tortosa, Álvarez Fernández and Jordá Pardo2023), El Abrigo 6 of the Humo complex (Ramos Fernández et al. Reference Ramos Fernández, Cortés Sánchez, Aguilera López, Lozano Francisco, Vera-Peláez, Simón Vallejo, Sanchidrián Torti, Márquez Alcántara and Fullola Pericot2007).

All three chambers contain dates and materials related to the Late Mesolithic—including here the so-called Transition between the Epipalaeolithic and the Neolithic of the Pellicer and Acosta proposal (1985). The identification of a Mesolithic stratigraphic unit presents difficulties due to the upper-level intrusions (Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, Pérez Ripoll, Morales Pérez, García-Puchol, González-Tablas Sastre and Avezuela Aristu2009; Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, García Borja, García-Puchol, Badal García, Pérez Ripoll, Pérez Jordá, Pascual Benito, Carrión García and Morales Pérez2013b). Until now, this episode has been dealt with in conjunction with the Early Neolithic (Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2009). However, here we propose separating the Mesolithic and the intrusions from the Neolithic phase (Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, García Borja, García-Puchol, Badal García, Pérez Ripoll, Pérez Jordá, Pascual Benito, Carrión García and Morales Pérez2013b). It was not possible to include the Mesolithic burial in the first Mesolithic (Pellicer Català Reference Pellicer Català1990; Pellicer Català and Acosta Martínez Reference Pellicer Català, Acosta Martínez and Jordá Pardo1986; Fernández et al. Reference Fernández, Sanchidrián, Jiménez-Brobeil, Remolins, Díaz-Zorita, Subirà, López-Onaindía, Maroto, Roca and Román2020), and its use is pending due to the lack of detail about the calculation of diets in the human remains analyzed.

The Late Mesolithic activity was marked by the occupation of the NV, NM, and NT chambers (Figure 9, Table S5). This phase attributed to geometric Mesolithic contexts due to the recovery of trapezes with abrupt retouches, microburins and denticulated tools. These materials originate from levels NM12, NM11, and NV3, which correspond to the strata which show alterations in the stratigraphic sequence of the NV and NM chambers (Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, García Borja, García-Puchol, Badal García, Pérez Ripoll, Pérez Jordá, Pascual Benito, Carrión García and Morales Pérez2013b), generating difficulties in the definition of the transition between the Mesolithic and the Early Neolithic. At a regional level, the Mesolithic can be found in sites with continuity of previous Palaeolithic periods, perhaps in Cueva Hoyo de la Mina (Fortea Pérez Reference Fortea Pérez1973), Bajondillo (Bj/3) (Cortés-Sánchez et al. Reference Cortés-Sánchez, Calle Román, Simón-Vallejo, Lozano-Francisco, Riquelme Cantal, Vera-Peláez, Parrilla Giráldez and Macías Tejada2020) and also in sites located in Cadiz such as El Retamar (Ramos and Lazarich Reference Ramos Muñoz and Lazarich González2002) and Embarcadero del río Palmones (Ramos Muñoz et al. Reference Ramos Muñoz, Castañeda, Pérez, Vijande and Castañeda2006), and more recently Zacatín (Martínez Sánchez et al. Reference Martínez Sánchez, Aguirre-Uribesalgo, Aparicio Alonso, Bretones García, Carrión Marco, Gámiz Caro, Gutiérrez Frías, Martínez-Sevilla, Morales Muñiz and Morgado Rodríguez2024) and Cueva de los Murciélagos (Martínez-Sevilla et al. Reference Martínez-Sevilla, Herrero-Otal, Martín-Seijo, Santana, Lozano Rodríguez, Maicas Ramos, Cubas, Homs, Martínez Sánchez and Bertin2023).

Figure 9. Detail of the Mesolithic and Early Neolithic phase in the NC. NV details are marked in blue; NM details are marked in green; NT details are marked in orange. The discarded samples are marked in red.

The Neolithic constitutes the last period in which human occupation has been documented in the three chambers. The samples point to a recurrent use and occupation of the chambers during the Early Neolithic (Figure 9, Table S5). From this phase, pottery production shows vessels with non-differential rims, flat and convex bases, and decoration techniques characterized by incisions, almagra slip, and impressions (Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Badal García, García Borja, García-Puchol, Pascual Benito, Pérez Jordá, Pérez Ripoll, Jordá Pardo, Arias, Ontañón and García-Moncó2005; García Borja et al. Reference García Borja, Aura Tortosa, Bernabeu Aubán and Jordá Pardo2010, Reference García Borja, Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo and Salazar García2014; Pellicer Català and Acosta Martínez Reference Pellicer Català, Acosta Martínez and Jordá Pardo1986, Reference Pellicer Català, Acosta Martínez, Pellicer and Acosta1997). The lithic productions are Neolithic due to the pressure flaking, blades with cereal polished and geometric microliths. The recovery of domestic plants and fauna, and the use of the cave as a necropolis in the different chambers (Pellicer Català and Acosta Martínez Reference Pellicer Català, Acosta Martínez and Jordá Pardo1986; Salazar García et al. Reference Salazar García, Pérez Ripoll, García Borja, Jordá Pardo, Aura Tortosa, García Puchol and Salazar-García2017) are also relevant. For the early Neolithic of the coast of Malaga, we find data from this culture in the sites of Hoyo de la Mina, Abrigo 6/Humo, Roca Chica, Hostal Guadalupe, La Dehesilla and Zacatín among others (Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, García Borja, García-Puchol, Badal García, Pérez Ripoll, Pérez Jordá, Pascual Benito, Carrión García and Morales Pérez2013b; Cortés-Sánchez et al. Reference Cortés-Sánchez, Calle Román, Simón-Vallejo, Lozano-Francisco, Riquelme Cantal, Vera-Peláez, Parrilla Giráldez and Macías Tejada2020; García Rivero et al. Reference García Rivero, Vera Rodríguez, Díaz Rodríguez, Barrera Cruz, Taylor, Pérez Aguilar and Umbelino2018; Martín-Socas et al. Reference Martín-Socas, Camalich Massieu, Caro Herrero and Rodríguez-Santos2018; Martínez et al. Reference Martínez, Aguirre-Uribesalgo, Aparicio, Bretones, Carrión, Gámiz, González Frías, Martínez-Sevilla, Morales and Morgado2024).

As previously mentioned, there is an alteration of the levels between this phase and the preceding one, especially in the NV chamber where a pit from the Early Neolithic occupations has been documented (Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, González-Tablas, Bécares Pérez, Sanchidrián Torti, Sanchidrián and Simón1998b , Reference Aura Tortosa, Badal García, García Borja, García-Puchol, Pascual Benito, Pérez Jordá, Pérez Ripoll, Jordá Pardo, Arias, Ontañón and García-Moncó2005, Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, García Borja, García-Puchol, Badal García, Pérez Ripoll, Pérez Jordá, Pascual Benito, Carrión García and Morales Pérez2013b). It must be said that 4 samples from the Early Neolithic have been discarded during the modeling process. Among these, the Ovis aries sample BETA-131577, which originates from a pit of the NV (Figure 9) is of particular importance. This sample could link to an archaic, hypothetical phase that has been poorly defined until now (Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, García Borja, García-Puchol, Badal García, Pérez Ripoll, Pérez Jordá, Pascual Benito, Carrión García and Morales Pérez2013b; García Borja et al. Reference García Borja, Salazar García, Jordá Pardo, Pérez Ripoll and Aura Tortosa2018; Martínez Sánchez et al. Reference Martínez Sánchez, Gámiz Caro, Vera Rodríguez, Pardo-Gordó, Gómez-Bach, Molist Montaña and Bernabeu Aubán2020). The NV model accepts this sample, but, when factoring in the data from the general model of NC, the sample is marked by the Agreement index of the model and the General “t” model of outliers as not sufficiently proximate in time to the other samples of this period (Table 5). The fact that it is a sample of Ovis aries points to a possible link to the earliest Neolithic horizon for the south of the Iberian Peninsula, which has already been analyzed in other studies (Aura Tortosa et al. Reference Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo, García Borja, García-Puchol, Badal García, Pérez Ripoll, Pérez Jordá, Pascual Benito, Carrión García and Morales Pérez2013b; García Borja et al. Reference García Borja, Aura Tortosa, Bernabeu Aubán and Jordá Pardo2010, Reference García Borja, Salazar García, Jordá Pardo, Pérez Ripoll and Aura Tortosa2018). Furthermore, it is important to highlight the great distance of these levels from the Mesolithic phase due to the presence of an erosion hiatus that separated the Late Mesolithic from the Neolithic. The truth is that although the model for the NV chamber does not contradict its validity, it has not been possible define this first Neolithic occupation in the Nerja Cave according to the available data.

It is still pending to carry out a more complete study of the radiocarbon sample of this period. This would enable us to improve the model and define the archaic phase and the transition concerning the Mesolithic phase. A review of the ceramic material of the Early Neolithic and new AMS analysis with preference for carbonized samples of grains and legumes, as well as for bones identified as domestic animals (Martínez Sánchez et al. Reference Martínez Sánchez, Gámiz Caro, Vera Rodríguez, Pardo-Gordó, Gómez-Bach, Molist Montaña and Bernabeu Aubán2020), focusing on those with evidence of consumption, could contribute to a better definition of this phase and thus clarify the chronology for the first spread of agriculture and farming in the Southern Iberian Peninsula (Pardo-Gordó Reference Pardo-Gordó2020). Moreover, the radiocarbon analyses of human remains recovered from the NM and NT chambers could elucidate whether there was simultaneous use of the cave for both occupation and burial functions, which was a common practice among Neolithic societies.

Only in the NM and NT chambers it has been possible to document analyzed materials related to the Middle-Recent Neolithic (Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2009; Pellicer Català and Acosta Martínez Reference Pellicer Català, Acosta Martínez and Jordá Pardo1986). On a radiometric level, we only have valid samples for the NT and NM chambers (Figure 7, Table S5). Similarly to the Early Neolithic, human remains have been recovered in the NM chamber (Salazar García et al. Reference Salazar García, Pérez Ripoll, García Borja, Jordá Pardo, Aura Tortosa, García Puchol and Salazar-García2017). This Middle Neolithic is the least known for the Peninsular Neolithic stages, but in recent years data linked to these chronologies have begun to be collected and analyzed (García-Rivero et al. Reference García-Rivero, Taylor, Umbelino, Price, García-Viñas, Bernáldez-Sánchez, Pérez-Jordà, Peña-Chocarro, Barrera-Cruz and Gibaja-Bao2020). This event has been observed in the region in sites such as Cueva del Toro (Málaga), Cueva de La Dehesilla and Cueva de los Murciélagos de Albuñol (García-Rivero et al. Reference García-Rivero, Taylor, Umbelino, Price, García-Viñas, Bernáldez-Sánchez, Pérez-Jordà, Peña-Chocarro, Barrera-Cruz and Gibaja-Bao2020; Martín Socas et al. Reference Martín Socas, Camalich Massieu, Buxó, Chávez Álvarez, Echallier, González Quintana, Goñi Quinteiro, Hernández Moreno, Mañosa and Orozco Köhler2004), among other sites.

In these chambers, archaeological evidence has been recovered from the last prehistoric occupation of the NC, which has been linked to the Chalcolithic. We have a 14C sample from the NT chamber (see Table S5). The estimation for the start is influenced by the gap without information existing between the end of the Middle-Recent Neolithic and the start of the Chalcolithic phase. This analysis and definition could be improved with a more detailed study for these phases. The estimation for the end extends to chronologies posterior to the Chalcolithic, beyond the Bell Beaker complex and the Bronze Age. The Jordá and, mainly, the Pellicer and Acosta digs in the NM and NT chambers documented materials associated with the Chalcolithic and later periods (Jordá Pardo Reference Jordá Pardo and Jordá Pardo1986; Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa Reference Jordá Pardo and Aura Tortosa2009; Pellicer Català and Acosta Martínez Reference Pellicer Català, Acosta Martínez and Jordá Pardo1986). The pottery remains are linked to the transition between the Final Neolithic and the pre-Bell Beaker period, comparable with the carinated pots horizon (García Borja et al. Reference García Borja, Aura Tortosa, Jordá Pardo and Salazar García2014, Reference García Borja, Salazar García, Jordá Pardo, Pérez Ripoll and Aura Tortosa2018). On the other hand, continuity in the use of polished stone has been identified with the presence of axes and adzes, as well as in the lithic production of large blades and bifacial arrowheads with concave base (Pellicer Català and Acosta Martínez Reference Pellicer Català, Acosta Martínez and Jordá Pardo1986). The new radiocarbon dates as well as a review of the archaeological remains and the stratigraphic contexts for the NT could contribute to the improvement of the periodisation and the existing knowledge for the Chalcolithic and later periods of the NC. For these chronologies we find sites such as La Pileta, Los Millares, El Barranquete, Sima del Angel, La Navilla or La Valencina among others (Cortés-Sánchez et al. Reference Cortés-Sánchez, Lozano-Francisco, Simón-Vallejo, Jiménez-Espejo, Odriozola Lloret, Macías Tejada and Morales Muñiz2023; Villalba-Mouco et al. Reference Villalba-Mouco, Oliart, Rihuete-Herrada, Childebayeva, Rohrlach, Fregeiro, Celdrán Beltrán, Velasco-Felipe, Aron and Himmel2021).

Discussion about the Bayesian models

As mentioned above, for this work we have made a phases model of each chamber of the NC (NV, NM and NT) and a general phase model for all the external chambers. The choice of the type of model to be applied should be linked to the characteristics of our deposit and the research questions. The difference between the phases and between each type of model is rooted in the utilized information; on one hand, the individual models use the excavation levels of each chamber and intervention and, on the other, the general phase model of NC uses information about the cultural designation for the materials. We have chosen to use the information from the excavation levels to construct the phases of the individual models due to the complexity of each chamber. However, this type of model does not allow, in some cases, the correlation of the different interventions carried out for the chamber in a unique model, as shown for the case of Torca, nor the complete correlation of all the trenches and chambers of the site. It is for this reason that it is essential to do a phase model that utilizes the cultural adscription of each excavation level to correlate the 3 chambers and the different interventions.

Similarly, a sole general model proposal for the site, along with a phase model, based on the cultural adscription of the archaeological materials entails a simplification of the site dynamics, as well as a sidestepping of the stratigraphic information and sedimentological studies for each chamber. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated how the acceptance of phase models hides information gaps between depositional events and accepts the inversion of levels, the percolation of samples, among other options. The phases model of each chamber has allowed us to verify level inversions in some levels that are part of the same archaeological phase, such as in the level NV 11 or in NM 14. This would not have been possible with a phase model of the cultural designation that accepted all the samples (Extrem Membrado Reference Extrem-Membrado2020). The phase model casts doubt on some radiocarbon dates of a phase due to the erosional hiatuses that we have for some levels of the chambers or because we do not have dates for all the levels that make up this phase. Therefore, to critically evaluate the samples, we must generate phase models for each chamber and finally correlate the spaces from a phase model of the site.

However, the phase models for each chamber have a limited interpretation for estimating the start and end boundaries of each phase due to the limited radiocarbon dates available for each level. Most of the phases that used stratigraphic levels for the construction of the NV, NM, and NT models consisted of only 1 or 2 samples (except for the NM 16 and NM 5). This limited information that allows us to know that a human activity event occurred at some point or was a unique event within a calibrated date range, and these dates can be represented by both the start and the end of the activity associated with the level. A similar situation is observed for the Gravettian, Solutrean A and B, Evolved Solutrean, Middle Magdalenian and Chalcolithic periods in the NC model. We could also explain the limited span proposed for the phases that are composed of 1 date (Span: 0–5). The paucity of available information for these phases is such that only a moment of activity can be discerned within the temporary interval of that particular period. Another possibility is the variable duration proposed for the span, which is generated from 2 dates (Gravettian span: 0–718) or phases for which the modeling considers only 2 samples as non-outliers and have a close chronology (Middle–Recent Neolithic: 0–1945).

Despite the limitations with the dates available, the construction of a general phases model for all the chambers is an excellent option for correlating the different chambers with evidence of prehistoric human occupation. In this model, we can group the dating of each chamber into the corresponding phases. This model has allowed us to observe the uses of the cavity and the joint dynamics of the chambers with human occupations of the NC, as well as whether the chambers were occupied in the same phases and their possible contemporaneity. It has also allowed us to detect issues that have not been fully defined and that may be of interest in future research.

Conclusions

The external chambers of the NC now have a radiocarbon sequence that corresponds to the period between ca. 30372 and 3597 cal. BP. It indicates a recurrent occupation from the Upper Pleistocene until the Holocene, despite the documentation of various hiatuses of variable duration. The analysis has enabled the identification of 11 archaeological phases with different deposition events. These extended human occupations of the NC, as well as the confirmation of visits to the Lower and Upper galleries of the cave, reflect recurrent use of the cave by prehistoric human groups that left behind a varied ensemble of archaeological remains linked to different technocomplexes.

The samples that have been utilized here acquire relevance not due to the calibrated results, but because they provide evidence of the different stages of human occupation/activities of the NC as they have a close relationship with the stratigraphic contexts and the archaeological remains. Our central interest in this work was to link the radiocarbon samples with the different occupation phases of the NC and to establish the possible time frames in which we could confirm the occupation of the site in the external chambers which contain stratified deposits. Moreover, the Bayesian application has revealed the different uses of the cave, as well as the close temporal relationship between habitat and burial functions. Also, various phases which have remains relating to both habitat and burial functions are still pending to be studied.

The stratigraphic and sedimentary studies for the chambers evidence different erosions between levels. For this reason, we consider more appropriate to use boundaries for the start and end of the phases. Although we do not have the information to know the degree of erosion, we can say that Bayesian chronological modeling is useful to explain the periodisation of the specific points in time for which we have no radiometric data and that, to an extent, may be a partial or direct consequence of these actions. There are other factors that could potentially condition the hiatuses of information deficit, namely the lack of dates linked to the start and end of each phase, the lack of validity of half of the samples we have for the cave, among other options.

This review of the radiocarbon samples for the Nerja Cave has shown there is a high percentage of samples which display atypical values. Tasks such as the collection of new radiometric data which enables the internal evolution of the Solutrean and Magdalenian, also the establishment of the first Neolithic horizon in the cave, as well as an improved study of the final occupation phases of the external chambers are still pending. It is necessary to reduce the uncertainty of these phases for which we only have one or few valid dates, despite documenting and recovering archaeological materials associated with them. However, the valid samples have contributed solid chronostratigraphic data via the Bayesian modeling. Although new dating for the levels with none, one, or a few dates could reduce the boundary constraints and improve the time range for some technocomplexes, and especially for the individual models of each chamber. It has enabled partial clarification of the sequence of the site, the correlation with the chambers and the periodization of the occupations of the cave. Undoubtedly, the Nerja Cave provides a broad radiocarbon sequence for contexts from the Upper Palaeolithic until the Chalcolithic of the Southern Iberian Peninsula.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2025.10183

Acknowledgments

This paper has been funded by project PROMETEO (CIPROM 2021/036) by Generalitat Valenciana, Direcció General de Ciència i Investigació, Conselleria d’Educació, Universitats i Ocupació and by project PID2021-127141NA-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13013/501100011033 and FEDER a way to make Europe. VEM was supported by predoctoral contract from project PROMETEO (CPI-22-640) by Generalitat Valenciana, Direcció General de Ciència i Investigació, Conselleria d’Innovació, Universitats, Ciència i Societat Digital; and currently is beneficiary by predoctoral grant Atracció del Talent del Vicerrectorat de Investigació de la Universitat de València (UV-INV-PREDOC22-2228793). This paper is part of VEM’s PhD thesis, and all authors agree. SPG is supported by Ramón y Cajal program (RYC2021-033700-I) funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13013/501100011033 and FEDER a way to make Europe. Several authors are part of the research group PREMEDOC (GIUV2015-213).