Henri Tajfel described attachment or identification with an in-group as ‘that part of an individual’s self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership in a social group (or groups) together with the value and emotional significance attached to that group membership ’ (Reference Tajfel1981: 255) and scholars have frequently invoked this idea to describe voters’ psychological attachments to (or identification with) political parties (Campbell, Converse, Miller et al. Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960; Green, Palmquist and Schickler Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2002).Footnote 1 A mountain of work has shown the relevance of partisan attachments to vote choice, policy preferences, perceptions of party positions, party leader evaluations, perceptions of ‘objective’ facts (e.g. about the economy), and much more.Footnote 2 In this paper, we explore a related idea that, while it has received far less attention than partisan attachments, it is potentially as important to the political behavior of voters in multi-party democracies. Specifically, we ask if western publics in multi-party systems have developed (or are developing) psychological attachments to the Left and Right as socio-political groups – in addition to (or instead of) partisan attachments?Footnote 3

Several lines of research in political science have suggested the answer to this question is yes – and that the consequences of this development are profound. One example of this profundity comes from Bølstad and Dinas (Reference Bølstad and Dinas2017), who show that standard models of spatial voting (including both proximity and directional models) produce quite different predictions when spatial models are modified to account for voters’ Left/Right identities.Footnote 4 More generally, scholars who have begun to investigate the nature and extent of Left/Right attachments have argued that in addition to their implications for electoral behavior, such attachments also have implications for parties’ electoral strategies, the extent to which party systems will tend toward bipolar competition, the extent and nature of system level electoral volatility (with more intra-block and less inter-block volatility), the extent and nature of strategic voting (with attachments to ideological groups facilitating strategic voting over parties in the same ideological block), patterns of partisan conflict and cooperation (e.g. why parties seldom ‘leap-frog’ each other on the ideological space), and the distribution of electoral support for different potential governing coalitions (Hagevi Reference Hagevi2015; Bølstad and Dinas Reference Bølstad and Dinas2017, Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila Reference Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila2021, and Oshri, Yair and Huddy Reference Oshri, Yair and Huddy2022, Lee, Santoso and Stevenson Reference Lee, Santoso and Stevenson2025).

Despite the obvious conclusion that Left/Right attachments should matter, direct evidence remains limited to a small set of surveys in a few contexts. As a result, the idea has not yet gained traction among scholars running major cross-national survey projects (like the CSES or ESS) or national election studies. This creates a dilemma: we need broader survey coverage to establish whether Left/Right attachments are widespread and developing alongside or replacing traditional partisan attachments; but allocating scarce survey time to this question is only warranted if the phenomena is known to be widespread and important.

In this paper, we offer a solution to this dilemma. We show how existing survey work in western democracies – in which respondents are asked to place parties on the left-right dimension – can be used to provide indirect evidence of psychological attachments to Left/Right groups. Further, since our method can be applied to historical survey data from many countries, we can both characterize how cross-nationally widespread the phenomena is and how it has changed over time. Specifically, we argue that existing survey work can be used to measure the extent to which respondents who might have attachments to Left/Right groups evidence an out-group homogeneity effect (OH) – that is, the tendency to perceive members of an out-group as more internally similar than members of one’s own group. If they do (for a given country at a given time), we argue this should be considered strong indirect evidence that such attachments are present.

To preview our results, we find consistent and robust indirect evidence (from 20 countries between 1996 and 2020) that western publics have developed psychological attachments to the Left and Right as social-political groups and that these attachments have grown over time –in line with rising left-right polarization and ‘block politics’ (Mair Reference Mair2008; Aylott Reference Aylott, Bergman and Strøm2011; Strøm and Bergman Reference Strøm, Bergman, Strøm and Bergman2011). Further, to validate this indirect approach, we included direct measures of Left/Right attachments on three surveys in Denmark, Italy, and Sweden. Consistent with our indirect evidence, those who are more attached to either the Left or the Right, using this direct measure, perceive greater OH with respect to those groups.

Overall, this paper makes three contributions. First, it repurposes the OH effect, which is traditionally used to study perceptions of variation within out-groups, as an indirect measure of psychological attachment to ideological groups. Though indirect, this measure is grounded in a well-established social-psychological tradition that links perceived out-group similarity to group identification. Second, by leveraging existing survey data, this approach allows us to analyze Left/Right attachment across many more countries and historical periods than previously possible. This greatly expands the evidentiary basis for assessing the existence of such attachments and allows us to explore potential mechanisms that might drive their development. Third, we demonstrate construct validity of this indirect measure by showing that the OH effect correlates with direct measures of Left/Right attachments in three countries.

Existing evidence that voters in multi-party democracies identify with the Left/Right as socio-political groups

The most direct evidence that voters may be developing Left/Right identities instead of (or in addition to) their partisan identities comes from Hagevi (Reference Hagevi2015); Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila (Reference Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila2021) and Oshri, Yair and Huddy (Reference Oshri, Yair and Huddy2022). In Sweden, Hagevi (Reference Hagevi2015) found that 41% strongly identified with the Left or the Right block (74% including weak identifiers), while only 25% strongly identified with a party. In addition, half of the strong block identifiers either did not identify with any party or only weakly identified with one. Thus, Hagevi concludes (p. 74) that ‘the increasingly weak link between citizens and parties has, to a significant degree, been replaced by bloc identifications’. Similarly, Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila (Reference Kekkonen and Ylä-Anttila2021) found Finnish voters were more likely to express a close affinity to a bloc of parties located on one side of the ideological spectrum than to a single party.

Oshri, Yair and Huddy (Reference Oshri, Yair and Huddy2022) come to similar conclusions in Israel where they examined the impact of a comprehensive ‘attachment to an ideological group scale’ on vote choice, political participation, attitudes toward political rivals, motivated reasoning, and reactions to new information. Specifically, they argue that the ‘ideological “left” and “right”… mean more than certain policy directives regarding the economy or society; rather, they signal group belonging and group competition – who is “us” and who is “them”’ (p. 4). Further, they conclude that, ‘Left versus right, or liberal versus conservative… reflect symbolic group identities that carry considerable affective significance for voters, in both the US and Europe… and such affinities independently affect their political behaviour and attitudes’ (pp. 4–5).

Finally, an older tradition of scholarship has long recognized the possibility that individuals might identify with the Left/Right, instead of (or in addition to) parties. For example, Arian and Shamir (Reference Arian and Shamir1983) argued that in Israel, ‘left and right labels… do not denote ideology and surely do not reflect ideological conceptualization and thinking’. Instead, these voters use the left-right dimension to affectively orient themselves to the political parties and to sort them (and other individuals) into two affectively charged categories: the ‘Left’ and the ‘Right’ (pp. 140–42). Similarly, in his influential work exploring the left-right concept, Bobbio (Reference Bobbio1996) explicitly recognizes the affective nature of these distinctions for many people. Specifically, he argues: ‘because the left/right distinction has very strong axiological connotations, people who belong to either side will tend to define their own side with words that are axiologically positive and the other side with words that are axiologically negative’ (pp. 37). This clearly suggests that the concept of left and right, as is used in politics, may not be a neutral classification of ideologies, but instead involves emotional and value-based attachments.

Further, research and commentary on the modern development of Western European party systems hints at this same idea. This work has observed that party attachments have been steadily weakening in many western multi-party democracies, creating space (and perhaps demand) for superordinate attachments that voters can use to orient themselves to politics in the absence of (or in addition to) partisan cues (e.g. Dalton, McAllister and Wattenberg, Reference Dalton, McAllister, Wattenberg and Dalton2002; Garzia, Ferreira Da Silva and De Angelis Reference Garzia, Ferreira Da Silva and De Angelis2022). Likewise, many scholars have noted an increasing tendency toward bipolar block competition in the western democracies (e.g.Bale Reference Bale2003; Mair Reference Mair2008) that is often supported by a ‘presidentialization’ of multi-party competition in which Left and Right blocks approach elections as personalized contests between their respective block leaders (e.g. Poguntke and Webb Reference Poguntke and Webb2005; Forestiere Reference Forestiere2009). Indeed, based on such trends, Mair (Reference Mair2008: 226) concluded that:

The balance of the European polities has appeared to shift in favour of the bipolar mode. This marks quite a substantial change in the functioning of European party systems… party competition is now more likely to mimic the two-party pattern through the creation of competing pre-electoral coalitions which tend to divide voters into two contingent political camps . [emphasis added]

Given increasing levels of left-right block competition, scholars like Hagevi (Reference Hagevi2015: 74) complete the argument by suggesting that such competition will ‘result in emotional and intellectual attachments to these blocs in the electorate’.Footnote 5 Indeed, Bantel (Reference Bantel2023) demonstrates exactly such attachments, concluding that for the majority of western democracies, ‘comprehending affective polarization based solely on partisan divisions limits us to studying affective partisanship rather than affective polarization , ie the dislike of out-partisans rather than political out-groups’. Instead, he argues that political scientists should conceptualize the underlying structure of the left-right as demarcating two political groups (the Left and Right) to which individuals tend to develop psychological identifications in addition to, or instead of, partisan attachments (p. 2).

Overall, it is clear from different strains of the literature that voters in western democracies increasingly see the Left and Right as socio-political groups to which they can form psychological attachments. Understanding and quantifying this phenomenon should be a key research priority. Thus, our aim in this paper is to examine indirect evidence on this phenomenon across a broader set of countries and time periods than prior works.

Using the OH effect as indirect evidence of psychological attachments to the left and right as social groups

The OH effect is the tendency to perceive members of one’s own social group as more variable on a given trait than a relevant out-group. The OH effect has been empirically identified in many different social groups – including national groups (Haslam, Oakes, Turner et al. Reference Haslam, Oakes, Turner and McGarty1995), religious groups (Hewstone, Islam and Judd Reference Hewstone, Islam and Judd1993), age groups (Linville, Fischer and Salovey Reference Linville, Fischer and Salovey1989), artificial laboratory groups (Rubin, Hewstone and Voci Reference Rubin, Hewstone and Voci2001), and political groups (Ostrom and Sedikides Reference Ostrom and Sedikides1992; Nicholson Reference Nicholson2012). The OH effect is central in social psychology because differences in the perceived variability of traits across social groups can suggest differences in the extent to which individuals rely on and are confident in stereotyping, as well as levels of prejudice and discrimination (e.g. Rubin and Badea Reference Rubin and Badea2012: 367).

Most explanations of the OH effect draw on Self Categorization Theory (SCT) or Social Identity Theory (SIT). SCT-based accounts argue that people typically think about out-groups in intergroup contexts that highlight ‘us versus them’, which reduces attention to differences among out-group members and thus produces perceived homogeneity (Hornsey Reference Hornsey2008; Leonardelli and Toh Reference Leonardelli and Toh2015). In contrast, people tend to think about their own group in intragroup contexts that prime ‘me versus us’, encouraging attention to within-group differences and leading to perceived in-group heterogeneity.

SIT-based explanations argue that people, motivated to protect self-esteem and maintain a positive social identity, perceive their in-group as more heterogeneous than a relevant out-group on negative traits. This enables individuals to maintain distance from a negative stereotype by attributing the trait to some in-group members but not to themselves, while seeing the out-group as consistently high on it. For example, a man may see all women as stubborn, but only some men as stubborn, ensuring sufficient variability to reasonably except himself from the negative stereotype. Of course, this explanation of the OH effect only applies to stereotypically negative traits (Kelly Reference Kelly1989; Voci Reference Voci2000). As Rubin and Badea (Reference Rubin and Badea2007) summarize, ‘the need for a positive social identity should motivate the perception of OH only on out-group negative traits, not on out-group positive traits’. Usefully, however, the key trait examined below is a stereotypically negative one and so this limitation (and consequent differences in trait level predictions from SCT and other theories of the OH effect) is not consequential for our study.

More generally, the main argument in this paper does not depend on the details of these different explanations of the OH effect. Instead, it follows for any explanation of the OH effect that requires an individual evidencing such an effect to identify with the relevant in-group. Essentially all published mechanisms that we have identified in the literature make this assumption.Footnote 6 For example, in their 2012 review of the various mechanisms underlying the OH effect, Rubin and Badea (p. 368) begin with the following general characterization of the relevant literature:

The dominant focus in the study of perceived group variability has been the influence of the perceiver’s group affiliation . The classic finding in this area is that people tend to perceive significantly more variability among members of groups to which they belong (in-groups) than among members of groups to which they do not belong. [emphasis added]

Indeed, our reading of the literature is not only that the perceiver’s group affiliation is a ‘dominant focus’ of these explanations, but that it is a necessary (though not sufficient) condition for the effect to occur.Footnote 7 That is, the various explanations all have the form: If an individual identifies with group j and [various mechanisms] then the OH effect follows.Footnote 8

Consequently, we would not expect to observe an OH effect in the perceptions of individuals who do not identify with the relevant groups. In our case, this means that we would not expect individuals who do not identify with Left/Right groups to evidence such an effect. Likewise, the observation of such an effect for an individual or group of individuals should push us toward the conclusion that these individuals have such attachments.Footnote 9

For example, imagine someone living in Texas whose attachment to Texas is uncertain. If she consistently believes Texans to be less homogenous than Californians (or people from other states) on relevant traits, then we would take this as indirect evidence that she has identified as a Texan.Footnote 10 Similarly, in countries (and time periods) where many voters have strong psychological attachments to the Left and Right as social-political groups, we should observe correspondingly large OH effects.

Estimating the OH effect for potential identifiers with left/right groups

The typical empirical study of the OH effect in social psychology starts with a set of subjects who are known apriori to identify with a group (typically, but not always, defined by race, ethnicity, gender, or class) and then asks those identifiers about individual-level trait variability in their own group and one or more relevant out-groups. Given our goal is to leverage the existing corpus of survey data on left-right party placements to estimate the OH effect for potential Left/Right identifiers across countries and over time, there are three ways that our design must necessarily differ from the typical social-psychological study. In this section, we discuss each of these design differences conceptually and save a detailed discussion of the exact measures we use until our Empirical Design section.

First, unlike the typical social-psychological study, we do not have information that designates survey respondents, apriori, as Left or Right identifiers. Our aim is precisely to infer whether such identifications exist from the presence or absence of an OH effect. Thus, the first challenge in our study is to identify sets of respondents who may plausibly be Left/Right identifiers (we call these ‘potential Left/Right identifiers’) and test for OH effects among those groups. Usefully, the surveys on which we rely provide two candidates for identifying pools of potential Left/Right identifiers: partisans of parties usually associated with the left/right and individuals who place themselves on the left or right of the center point on the traditional left-right self-placement question.Footnote 11 ,

That said, given the need to identify potential Left/Right identifiers before testing for an OH effect, we also conduct a placebo test (reported in online Appendix E). Here, instead of using the criteria above, we randomly assign respondents to ‘potential Left’, ‘potential Right’, or non-identification groups, run all models on these random groupings many times, and average the results. As expected, these randomly constructed groups show no OH effect.

Second, our surveys do not ask respondents to evaluate the variability of other individuals on a characteristic. Instead, our surveys ask respondents to indicate the positions of a set of parties on a relevant trait dimension. The first difference (position placements vs. variability judgments) is easily addressed because respondents are typically asked about several parties and so we can construct a measure of perceived variability from the several perceived party placements.

The second difference (a focus on parties instead of individuals) is well justified if people can think of parties as members of ideological groups. Usefully, there is a huge literature in social psychology that attests to the fact that people often rely on exemplars when making judgments about the members of social groups, including their traits and variability in those traits (Linville, Fischer and Salovey Reference Linville, Fischer and Salovey1989; Smith and Zárate Reference Smith and Zárate1992; Hogg Reference Hogg2001; Platow and van Knippenberg 2001; Barreto and Hogg Reference Barreto and Hogg2017; Bröder, Gräf and Kieslich Reference Bröder, Gräf and Kieslich2017). Work in political psychology makes the same point for partisan groups (Myers and Hvidsten Reference Myers and Hvidsten2025; Nicholson, Coe, Martinsson et al. Reference Nicholson, Coe, Martinsson and Heit2016). For example, Myers and Hvidsten (Reference Myers and Hvidsten2025) show that exposure to information about counter-stereotypical partisan exemplars (party elites) changes individuals’ levels of partisan animosity. Even more relevant, Nicholson, Coe, Martinsson et al. (Reference Nicholson, Coe, Martinsson and Heit2016) found that Swedish survey respondents rated politicians from different parties as much less distinct from each other when the politicians were framed in terms of the superordinate ideological (left-right) groups in addition to a partisan frame. Individuals had no problem thinking of party leaders as members (and exemplars of) left-right social groups when that frame is activated – as it is when they are asked to place parties on a left-right scale.Footnote 12

Finally, political scientists studying partisan polarization in the US, such as Iyengar and Westwood (Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015), have taken a similar view – explicitly including organizations, like the NRA and Greenpeace, as exemplars of Republican and Democratic social groups, respectively. Given this, we think it is reasonable to assume that when asked to place parties on the left-right, respondents think of these parties as members of (and even exemplars of what it means to be a member of) the Left or Right – so that when they place out-group parties much closer together than in-group parties this is due to the same psychological process that leads to the oft-demonstrated OH effect in assessments of individuals.

Third, the typical studies of the OH effect normally ask respondents to rate groups on unidirectional trait scales (so a higher score indicates ‘more’ of the trait). In contrast, our left-right placement scale is inherently bi-directional (it gives a position rather than an amount of the trait). This matters because much of the OH effect literature distinguishes between stereotypically negative and positive traits (e.g. SIT-based explanations), – an idea that does not map neatly onto a positional scale. We argue, however, that left-right ideology can be viewed as two separate dimensions that tap the extent of (either left or right) ideological extremity. Such extremity is generally viewed as stereotypically negative (Peterson Reference Peterson2005; Simas Reference Simas2020), making these traits especially likely to exhibit OH effects under SIT.

Moderators of the OH effect

Although the OH literature makes clear that attachment to a relevant group is necessary for the effect to occur, it does not imply that attachment alone is sufficient. Indeed, several reviews of the voluminous literature on the OH effect have identified contextual factors that can moderate, eliminate, or even reverse the effect. This is important to our analysis because it suggests several variables, relevant to our setting, that should either amplify the OH effect for some of our cases or cause it to vary across our respondents, countries, and overtime in ways that we can investigate empirically.

Specifically, the previous literature has established that the OH effect is larger for real social groups than for artificial laboratory-constructed groups (Ostrom and Sedikides Reference Ostrom and Sedikides1992; Boldry, Gaertner and Quinn Reference Boldry, Gaertner and Quinn2007), for groups in direct competition (Judd and Park Reference Judd and Park1988; Ackerman, Shapiro, Neuberg et al Reference Ackerman, Shapiro, Neuberg, Kenrick, Becker, Griskevicius, Maner and Schaller2006), and for traits viewed as stereotypically negative (Rubin and Badea Reference Rubin and Badea2012; Rubin, Hewstone and Voci Reference Rubin, Hewstone and Voci2001). Since the Left and Right are real, competing groups, our setting is one in which we should expect such effects (if indeed people have developed Left/Right attachments). Likewise, as noted above, the trait we examine (parties’ left-right policy positions) can usefully be characterized as ideological extremity, a generally negative trait.

In addition, the previous literature has identified several contextual variables that are likely to induce variation in the OH effect across our respondents, countries, and overtime. These include real group variability in the target trait, the strength of group attachments (ie a bigger OH effect for stronger identifiers), and the extent of intergroup distinctiveness (ie a bigger OH effect when few individuals identify with both groups).Footnote 13

Real Variability

There is, of course, real variation in the policy positions of parties – and voters’ beliefs about the homogeneity of these positions among Left and Right parties may well reflect this reality. Thus, in all the empirical analyses below, we control for the level of real policy difference between parties. In addition, since we construct our estimate of perceived variability in left-right policy positions by aggregating across relevant parties, we also include controls (in all our empirical models) for the number of parties on the left and right, respectively.

Identity Salience

Regarding the salience of group membership, the social-psychological literature (e.g. Simon and Pettigrew Reference Simon and Pettigrew1990; Lee and Ottati Reference Lee and Ottati1995) suggests that stronger attachment to a group increases motivation to maintain a positive social identity, thereby amplifying the OH effect. Thus, we include this moderator in our analysis using two proxy measures. First, we use a measure of extremity in left-right self-placement as a proxy for the strength of attachments to Leftist or Rightist groups. Second, we use the respondent’s strength of attachment to one of the parties in the Left/Right groups.Footnote 14 For both measures, we expect bigger OH effects among respondents who have higher scores on these proxy measures. To avoid confusion, these two proxies for the contextual variable ‘strength of attachment to the Left/Right’ are distinct from the indicator variables we used in Table 1 to identify potential Left/Right identifiers (and so among whom we looked for an OH effect).

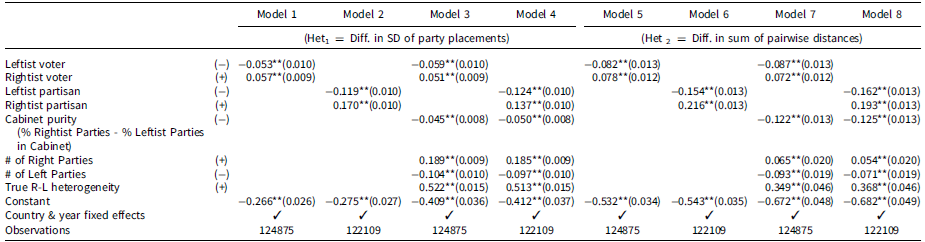

Table 1. Determinants of in-group heterogeneity and out-group homogeneity

Standard errors in parentheses, **P < 0.01.

Intergroup distinctiveness

Jetten, Spears and Postmes’s (Reference Jetten, Spears and Postmes2004) meta-analysis links the size of the OH effect to intergroup distinctiveness, which is simply the extent to which there are few individuals identifying with both groups. Thus, in a period of increasing polarization (and especially affective polarization) between the Left and Right in Western democracies (Mair Reference Mair2008; Holmberg Reference Holmberg, Dalton and Klingemann2009; Aylott Reference Aylott, Bergman and Strøm2011; Hagevi Reference Hagevi2015), we should expect the size of the OH effect among Left/Right identifiers to be increasing over time in tandem with increasing levels of Left/Right polarization. As noted earlier, Peter Mair and others have argued that bipolar politics has been displacing traditional multi-polar politics in many democracies, and this may drive the development of Left/Right attachments over time (as Hagevi suggests). Thus, after presenting aggregated results, we explicitly model heterogeneity in the Left/Right OH effect over time, showing that the effect has been growing apace with polarization.

Finally, beyond the moderators suggested by the socio-psychological literature, the political science literature on how voters perceive parties’ left-right positions points to additional factors we need to account for. Fortunato and Stevenson (Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2013) and Adams, Weschle and Wlezien (Reference Adams, Weschle and Wlezien2021) show that voters tend to perceive parties as having more similar positions on the left-right scale when the parties cooperate formally in cabinets or informally in many other ways. Thus, all the analyses below control for the ‘purity’ of left or right parties’ cooperation patterns in government – that is, whether they cooperate only with parties on their own side.

Therefore, a summary of our empirical project (focusing on leftist voters, but the same applies to rightists) is simply:

If survey respondents who identify with a leftist party or place themselves on the left of the left-right dimension, judge the set of rightist parties to be more homogenous in their left-right positions than the set of leftist parties, we will take this as evidence for the existence of a Left/Right OH effect and infer that such respondents have (on average) developed psychological attachments to the Left as a social group (in addition to, or instead of, usual partisan attachments).

Empirical design

To empirically explore the argument laid out above, we rely on a wealth of cross-national survey data available from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES). The final dataset we assemble contains responses to relevant survey questions made by over 120,000 respondents from 20 advanced Western democracies in the period 1996–2020 (86 surveys). Table A1 in online Appendix A summarizes the countries and surveys covered by our work.Footnote 15

To capture voters’ perceptions of in- and out-group heterogeneity, we use survey items in which respondents place parties on the left-right dimension. We categorize parties as either leftist or rightist by first calculating the average left-right placement of each party based on responses from all respondents. If a party’s average placement is less than the midpoint, we classify it as leftist and if the average is greater than the midpoint, we classify it as rightist.Footnote 16 Since the party placement questions use a 0–10 scale, parties with average positions greater than 5 are assigned to the rightist group and those less than 5 to the leftist group.Footnote 17 In the vast majority of cases, this simple rule classifies parties on the left and right in exactly the way most informed observers would. However, to ensure the robustness of our results to this classification, in Appendix B we replicate our results using four alternative classifications that exclude various sets of parties for which a left/right classification may be ambiguous.Footnote 18

After separating parties into Left and Right, we measure each respondent’s perceived ideological heterogeneity using two different indicators.Footnote

19

Our first measure is

![]() $He{t_{1j}} = SD_j^R - SD_j^L$

, where

$He{t_{1j}} = SD_j^R - SD_j^L$

, where

![]() $SD_j^R$

is the empirical standard deviation of respondent j’s placements of all rightist parties and

$SD_j^R$

is the empirical standard deviation of respondent j’s placements of all rightist parties and

![]() $SD_j^L$

the standard deviation of respondent j’s placements of all leftist parties. Increasingly positive values of this variable indicate that the respondent perceives the rightist parties to be more ideologically heterogeneous than the leftist parties (while increasingly negative values indicate the opposite).

$SD_j^L$

the standard deviation of respondent j’s placements of all leftist parties. Increasingly positive values of this variable indicate that the respondent perceives the rightist parties to be more ideologically heterogeneous than the leftist parties (while increasingly negative values indicate the opposite).

Our second, alternative, measure (Het

2j) relies on respondents’ perceived ideological distances between parties. For each respondent, we first calculate the absolute value of her perceived pairwise left-right distance for every party pair in each of the Left/Right groups. We then sum these perceived pairwise differences for all party pairs in a group, average it over the total number of pairs in the group, and finally calculate the difference between the Left and Right groups. Formally, the measure is

![]() $H{et_{2j}} = {{2}\over{{r\left( {r - 1} \right)}}}\mathop \sum \nolimits_{m = 1}^{r - 1} \mathop \sum \nolimits_{n = m + 1}^r \left| {p_j^m - p_j^n} \right| - {{2}\over{{l\left( {l - 1} \right)}}}\mathop \sum \nolimits_{s = 1}^{l - 1} \mathop \sum \nolimits_{t = s + 1}^l \left| {p_j^s - p_j^t} \right|$

, where

$H{et_{2j}} = {{2}\over{{r\left( {r - 1} \right)}}}\mathop \sum \nolimits_{m = 1}^{r - 1} \mathop \sum \nolimits_{n = m + 1}^r \left| {p_j^m - p_j^n} \right| - {{2}\over{{l\left( {l - 1} \right)}}}\mathop \sum \nolimits_{s = 1}^{l - 1} \mathop \sum \nolimits_{t = s + 1}^l \left| {p_j^s - p_j^t} \right|$

, where

![]() $p_j^m$

and

$p_j^m$

and

![]() $p_j^n$

represent respondent j’s placements of party m and n associated with the rightist party group (with r members) and

$p_j^n$

represent respondent j’s placements of party m and n associated with the rightist party group (with r members) and

![]() $p_j^s$

and

$p_j^s$

and

![]() $p_j^t$

represent respondent j’s placements of party s and t associated with the left party group with l members). As with Het

1j, more positive values of Het

2j indicate relatively more perceived heterogeneity for the rightist group over the leftist group.

$p_j^t$

represent respondent j’s placements of party s and t associated with the left party group with l members). As with Het

1j, more positive values of Het

2j indicate relatively more perceived heterogeneity for the rightist group over the leftist group.

Once we have calculated Het 1j and Het 2j for each respondent,Footnote 20 we must then identify each respondent as a potential Left identifier, a potential Right identifier, or neither. As discussed above, we do this in two different ways (and show, in Appendix B, that these classifications are robust to several alternative classification strategies). First, we categorize a respondent as a potential Leftist identifier if she placed herself from 0 to 3 (inclusive) on the 0–10 left-right scale, a potential non-identifier (the reference group) if she placed herself between 4 and 6, and as a potential Rightist identifier if she placed herself at or greater than 7.Footnote 21 In the tables below, we name the two indicator variables capturing potential Left/Right identifiers Right Self Placement and Left Self Placement.

The second proxy is the respondent’s self-reported party identification. Specifically, we assign all respondents who identify with a leftist party as potential Leftist identifiers, those that identify with rightist parties as potential Rightist identifiers, and everyone else as potential non-identifiers (the reference group, including non-partisans and partisans of the parties that do not belong to the Left or Right).Footnote 22 In the tables below, we call the two relevant indicator variables Right Partisan and Left Partisan.

Empirically, we expect Right Self Placement and Right Partisan to be positively associated with our dependent variables, while Left Self Placement and Left Partisan to be negatively associated with the dependent variables. In other words, people who place themselves to the right (left) and who identify with parties on the right (left) tend to see the rightist group as more (less) heterogeneous than the leftist group.

Control variables

In addition to our dependent variables and major explanatory variables, we also include a set of control variables, as discussed above. First, using information from the ParlGov project (Döring and Manow Reference Döring and Manow2016), we construct the variable Cabinet Purity, which is the difference between the percent of rightist and leftist parties in a cabinet at the time of the survey.Footnote 23 This variable ranges from 1 to −1, where 1 means that all cabinet parties are from the rightist group while −1 means that all cabinet parties are from the leftist group. Again, Fortunato and Stevenson (Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2013) demonstrate that citizens tend to see parties ruling together in the cabinet as ideologically close to each other. Thus, we expect this variable to be negatively associated with our dependent variables.Footnote 24

Second, we control for the Number of Rightist Parties and the Number of Leftist Parties on which our heterogeneity scores were calculated. These variables simply measure the total number of leftist and rightist parties that respondents could place on the left-right scale in the CSES survey.

Third, in keeping with the literature on the OH effect that finds true trait heterogeneity to be strongly associated with perceived trait heterogeneity, we control for a measure of the true ideological heterogeneity of the left and right parties.Footnote 25 Specifically, we define True R-L Heterogeneity in the same way as our DVs (and match this measure to the DV in each specification) but instead of using each respondent’s party placements to build the measures, we use the average placement of each party across all respondents.Footnote 26 The summary statistics of these variables are presented in Table A2 in Appendix A. Finally, we include fixed effects at the country and the year levels to account for unobserved variables at each of these levels that might impact perceived relative heterogeneity.Footnote 27

Results

To investigate whether the respondents across our 20 countries and 86 surveys exhibit the OH effect for Left/Right groups, we estimate a set of linear regressions in which the dependent variable is either Het 1j or Het 2j and the main independent variables (those above the horizontal line in Table 1) are indicators for whether a respondent is a potential Left identifier, Right identifier, or neither (the baseline). The results are summarized in Table 1. In Models 1, 3, 5, 7, we rely on left-right self-placement to identify potential Left/Right identifiers, while in Models 2, 4, 6, 8, we use party attachment (to left or right parties) instead.

Both dependent variables used in Table 1 capture the extent to which respondents perceive the rightist party group to be more ideologically heterogeneous than the leftist party group. Further, for both our indicators of potential Left/Right identifiers, the baseline category is a respondent who was not classified as a potential Left/Right identifier. Thus, evidence of an OH effect for our respondents corresponds to positive coefficients for the variables Right Self Placement and Right Partisan and negative coefficients for Left Self Placement and Left Partisan.

Clearly, the results in Table 1 show exactly these effects (all statistically different from zero) and are robust to the different model specifications in the table (as well as to the many additional specifications and alternative measures reported in the Appendices).

This clear evidence of an OH effect is exactly what we would expect if our potential Left/Right identifiers have, in fact, developed psychological attachments to the Left and Right as social groups.Footnote 28 Thus, these results are clear indications that such psychological attachments are likely real, should get more attention from students of political behavior, and that direct measures of these attachments should be included in future voter surveys.Footnote 29

Beyond the results in Table 1, the literature highlights several moderators of the OH effect that should matter in our context. Specifically, we will have more confidence in the message of Table 1 if it is also the case that the OH effect changes across contexts in ways that the literature suggests it should. Thus, in the next two sections we examine (1) whether the OH effect is stronger for individuals likely to be more strongly attached to the Left/Right, and (2) whether the OH effect is increasing over time, as we would expect given rising left-right (affective) polarization in most western democracies.

The conditioning effect of attachment strength

As discussed above, the literature on the OH effect suggests that individuals with stronger in-group attachment should exhibit a larger OH effect. To test this, we created two different indicators identifying the respondents most likely to be strongly attached to a Left/Right group.

First, in models that use left-right self-placement to identify potential Left/Right identifiers, we assume that those farther from the center of the left-right scale are the respondents most likely to identify strongly with the Left/Right. We operationalize this with two dummy variables: Far Left Self Placement for respondents placing themselves at 0–2 on the 11-point left-right scale and Far Right Self Placement for those at 8–10. The reference group (coded 0 on both dummies) are those who place themselves from 3–7, inclusive.

Second, in models that use party identification to identify potential Left/Right identifiers, we assume that respondents who identify more strongly with a (left or right) party are the most likely to identify strongly with the Left/Right.Footnote 30 Using the 5-point party attachment question in the CSES, we create two dummy variables, Strong Left Partisan and Strong Right Partisan, that indicate partisans who consider themselves ‘very close’ to one of the parties we have identified as a left or right party.Footnote 31 All other respondents, including non-partisans, partisans identifying only weakly with parties belonging to the left or right, and partisans identifying with parties that are not connected with the left or right, are the reference group.

Next, we estimate the same set of models in Table 1 adding these new variables. Clearly, we expect the estimated coefficients on these new dummy variables to be in the same direction as the corresponding variables in the previous models and that the effects for these individuals will be larger than for weaker potential identifiers.

The key results are presented in Figure 1, including coefficient estimates and 95% confidence intervals, and the full results in Table C1 in Appendix C. The left panel shows results for the DV Het 1j and the right panel for Het 2j. Clearly, these results meet our expectations. The size of the OH effect for individuals who place themselves far to the left (right) or who are strong right (left) partisans is almost twice the size of the effect in the baseline models. This is consistent with the predictions of the literature on individual heterogeneity in the OH effect and so should increase our confidence that these effects are real – and that voters are indeed developing psychological attachments to the Left/Right groups.

Figure 1. The effect of the strength of group attachment.

In-group heterogeneity and OH over time

In this section, we investigate whether the OH effect for Left/Right groups is increasing over time, as we would expect if rising polarization has resulted in more individuals developing, or strengthening attachments to the Left/Right. To test this, we re-estimate Model 3 and Model 4 in Table 1 (ie DV = Het1), interacting the key variables with dummies for several sub-periods.Footnote 32 To illustrate these results, we plot the marginal effect of left-right group attachment on perceived heterogeneity and the associated 95% confidence intervals by type of voters and different sub-periods in Figure 2. The full estimated results are presented in Appendix G.

Figure 2. Effect of group attachment on perceived heterogeneity over time.

Once again, the results are consistent with our expectations. Regardless of the measures we employ to capture potential Left/Right identifiers or the ways we separate time periods, the size of the OH effect (ie the distance between the point estimates for left and right voters) as well as its consistency (a negative effect for leftist and a positive one for rightist) is increasing over time – with a clear and consistent OH effect emerging (as we might expect) only after 2008.

Robustness

The main contribution that we make in this article is to answer an empirical question: Are citizens in multi-party western democracies developing psychological attachments to the Left and Right? Thus, it is particularly important that we explore the robustness of the results to plausible changes in model specification, measurement, and sample – as well as to construct appropriate placebo tests. While some of these checks are discussed in the text, the details of many others (and the justification for each) must necessarily be relegated to the appendix. Looking across all these various efforts, however, we can report here that the substantive (and, to a remarkable extent, the specific numeric) results reported in the main text are robust to a wide range of such changes, including:

-

1. Using four different schemes for classifying parties as left or right (and for excluding parties whose left-right classification may be ambiguous). [Appendix B]

-

2. Increases to the minimum number of parties on the left or right required for a survey to be included in the analysis. [Appendix D1]

-

3. Excluding all respondents who might reasonably be considered partisan extremists from the analysis (leaving only 44% of the original sample). [Appendix D2]

-

4. Excluding respondents who misplaced parties to the wrong group. [Appendix D3]

-

5. Excluding the party that a respondent is strongly attached to from the calculation of her perceived left-right heterogeneity. [Appendix H]

-

6. Using different methods for dealing with respondents who appear to reverse the left-right scale when placing parties (including doing nothing). [Appendix D4]

-

7. The use of plausible controls or not [All tables in the text and Appendix], different plausible measures of some controls [Footnote 21], specifications with or without country, time, or survey fixed effects, and specifications with country and/or time random effects. [Footnote 25]

-

8. Two different ways of measuring the dependent variable. [All tables in the text and Appendix]

-

9. Two different proxies for membership in groups of potential Left/Right identifiers. [All tables in the text and Appendix]

In addition, in a placebo test in which we randomly form thousands of different groups of potential Left/Right identifiers and re-run our main models on each, we find no hint of any OH effects (see Appendix E).

We have also produced country-specific estimates of our main models (with controls) for the post-2008 period (for both the strongest potential identifiers with the Left and Right and for all respondents). Of the 168 estimates for the strongest identifiers,Footnote 33 only one estimate is statistically different from zero and in an unexpected direction. For the broader post-2008 sample (including all potential identifiers), this number increases to only 11 (6.5% of the 168 estimates). Thus, it is clear that the aggregate estimates reported above are broadly representative of the direction and statistical significance of corresponding country-by-country estimates.Footnote 34 Further, as we show in Appendix K, we find that the OH effect is also present among high-knowledge individuals, indicating that the patterns observed in this paper are not primarily driven by asymmetric political knowledge – that is, they cannot be explained simply by low-information voters failing to distinguish between out-group parties due to lack of familiarity.

Finally, in Appendix F we provide an analysis of whether potential Left/Right identifiers perceive out-group members as ideologically more extreme than in-group members. While such an effect is not strictly implied by the OH effect, in our case – where the trait in question is ideological extremity – it seems likely that for individuals affectively attached to the Left/Right the two effects would occur together. That is, an in-group member would see the out-group as more homogeneously extreme than the in-group. This is exactly what we find.

Alternative explanations

While we contend that the argument and analyses presented above provide evidence that many voters identify with the Left and Right as socio-political groups, in this section we explore two alternative explanations for the OH effects that we report. Since we do not have space in the main text to present all the arguments and evidence for these alternatives, we provide a thorough discussion (with relevant empirical results) in Appendix H. Here, we simply summarize that discussion.

The first alternative explanation assumes a voter with standard spatial preferences who cares about accurately perceiving parties’ positions in proportion to the likelihood of voting for them. For parties she would never consider supporting, she has little incentive to distinguish their policies beyond knowing they are ‘far away’. By contrast, she has stronger incentives to differentiate among parties she might vote for – for example, all leftist parties for a left-leaning voter. Thus, when asked about rightist parties, she will have little specific information to distinguish them and so will simply report similar (rightist) positions for them all. In contrast, she will have invested time and energy in understanding the distinctions between the leftist parties and so will tend to spread them out (controlling for their real positions). This mechanism can thus lead to an apparent OH effect, without requiring any Left/Right attachment.

We construct a test of the implications of this alternative (versus our argument), by pointing out that if voters behave as prescribed by this alternative (ie investing in understanding the ideological positions of parties they might vote for and not otherwise) then we should see the weakest OH effects among those who are the strongest partisans. The reason is that strong partisans are unlikely to consider voting for any other party and so, according to the logic of this argument, have little incentive to invest in understanding the ideological differences between any of the parties. Only weak partisans or non-partisans will consider multiple parties and so (if these parties are confined to one side of the ideological spectrum) will produce the kind of spurious OH effect suggested by this alternative.

Our previous analysis of the impact of partisanship on the size of the OH effect, however, does not support this implication. Instead, we found the opposite: a large and robust positive effect of the strength of partisanship on the size of the OH effect (see Figure 1).

The second alternative explanation we explore in Appendix H is the (likely subconscious) desire of survey respondents who are partisans of a given party to protect the ideological distinctiveness of their party relative to others. Thus, they will tend to ‘push’ other parties away from the position of their party, which can result in a spurious OH effect (as illustrated in Appendix Figure H1.1). That said, this alternative yields an implication that directly contrasts with the implications of our story and thus allows a clear test between the two accounts. Specifically, as we show in Appendix H, this ‘partisan distinctiveness’ argument implies that if we recalculate our OH effect (for partisans) excluding their parties, the OH effect should be largest for partisans of leftist (rightist) parties located in the middle of their ideological group, and smaller for partisans of the most extreme or most centrist parties. Figure H1.2 provides the relevant results, which clearly refute this implication. Table H1.1 further demonstrates that the main results remain robust when we recalculate the dependent variables excluding each partisan’s supported party.

Using direct survey measures of left-right attachments: proof of concept

One motivation for doing the large-scale, indirect investigation provided above was to assess whether it makes sense to invest significant resources in collecting more direct measures of attachment to the Left or Right as socio-political groups. Clearly, our analysis suggests that such an investment is warranted. That said, we can also provide some preliminary evidence that such direct measures are likely to ‘work’ as expected. One way to do that is to build a multi-item survey battery that directly measures an individual’s psychological attachment to the Left or Right and then examine if that direct measure is associated, at the individual level, with the strength of the OH effect in left-right party placements.

Below we estimate such correlations to provide a preliminary direct test of the argument we have made (and demonstrated indirectly) above. Specifically, we rely on a series of original pilot surveys that we conducted in Denmark, Italy, and Sweden, on which we were able to include question batteries designed to directly measure respondents’ psychological attachment to the Left and, separately, to the Right.Footnote 35

The survey information, specific questions, justification, estimation strategies, and detailed results are provided in Appendix I (we used appropriate IRT models to estimate attachment to each group from a well-validated group attachment question battery). Figure 3 summarizes the main result:

Figure 3. Effect of group attachment on perceived group heterogeneity.

These findings indicate that individuals who are more psychologically attached to the Left or the Right as socio-political groups exhibit a greater OH effect in their left-right placements of the parties. Those strongly attached to the Right (Left) perceive parties on the Left (Right) as more homogeneous than those who are weakly attached. This individual-level, direct evidence reassures us that the widespread and growing OH effect that we have observed across many countries reflects genuine psychological attachment to the Left and the Right.

Conclusion

We began this paper by highlighting the empirical literature that has begun to demonstrate that some western voters are developing psychological attachments to the Left and Right as social-political groups and highlighted the implications of this development for intragroup and intergroup volatility in vote choices, the frequency and nature of strategic voting, voter satisfaction with electoral outcomes, and a myriad of other important political behaviors and attitudes that have long been tied to such affective political attachments. This is an important paradigm shift, indicating that political competition in multi-party systems may, in practice, be perceived by voters as dividing into two broad camps, with far-reaching consequences for our understanding of coalition politics, intra-bloc strategic voting, and polarization. Indeed, if this phenomenon is cross-nationally widespread and growing (as we have argued it is), one can hardly imagine a more consequential development for understanding the electoral behavior of Western publics.

Unfortunately, however, the empirical work on this topic so far has been confined to a few isolated surveys and so has not yet motivated scholars to invest in directly measuring these attachments across a broad set of Western democracies. The purpose of this paper was to indirectly examine if this phenomenon appears to be happening in a large set of countries over a long-time period, with the goal of deciding if investment in more direct measurement is warranted. Our results suggest clearly that it is. Specifically, we show that the OH effect for Left/Right groups is robustly apparent in many Western democracies and that it is growing over time – as we would expect if such attachments developed in tandem with increasing levels of bipolar political polarization (as some scholars have suggested).

That said, our evidence is indirect. Consequently, it cannot serve as the final measure of the extent and nature of Left/Right attachments. Only direct measures (ideally built from carefully constructed question batteries), which we have attempted to do, will provide the kind of precise estimates of these attachments that are necessary if we are to understand: (1) their relationship to partisan attachments – e.g. do they exist alongside partisan attachments or do they replace them?, (2) their implications for voting behavior (including strategic voting), (3) their effect on satisfaction with electoral outcomes and thus democratic stability. Such direct measures will also be necessary to properly characterize cross-national differences in the extent and nature of these attachments and then to explore the causes of these differences. For example, do such differences reflect corresponding differences in the extent of left-right polarization (Gidron, Adams and Horne Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020), differences in electoral institutions, or something else?

While these questions should be the subject of future work, we conclude with a preview of one important downstream consequences of psychological attachment to Left and Right groups (and one that – if absent – would mean such attachments are probably not worth trying to measure): the impact of psychological attachment to the Left and Right on the distribution of support for parties – controlling for psychological attachments to individual parties. Does an attachment to the Left and Right impact voting above and beyond psychological identities? In Appendix L, we use the direct, individual-level, measures of psychological attachment to the Left and (separately) to the Right that were mentioned above (and explained in Appendix I) along with measures of respondents’ partisan attachments to show that the impact of psychological attachments to the Left and Right on vote choices in Sweden, Italy, and Denmark are both sensible and consequential. In general, greater attachment to the Left or Right is strongly associated with respondents’ support for parties that are seen as farther left or right, respectively, even after controlling for partisan attachments.

Thus, we conclude with an empirically justified call for students of comparative political behavior to invest in the development of appropriate survey batteries across a large number of countries to directly measure psychological attachments to the Left and Right alongside traditional partisan attachments. At the same time, our findings suggest that such attachments may already be shaping electoral behavior, structuring party competition, and influencing democratic attitudes across many Western democracies.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S147567652610070X.

Data availability statement

The data and replication files for this paper are publicly available on the EJPR website.

Funding statement

The authors do not receive any funding for this project.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.