1 Introduction

There is long-standing fascination with the study of colour among scholars from linguistics, psychology, art, and cognitive science. Scholars from various fields, including linguistics, psychology, art, and cognitive science, have long been fascinated by the study of colour. However, the cognitive and emotional significance of colour use, particularly in the context of literature and language, has not been fully explored. In this Element, we aim to address this gap by examining the relationship between language, emotion, and colours through a comprehensive approach that integrates cognitive linguistics, literary analysis, psychology, and corpus linguistics. As such, we propose the following research questions:

1. How are colour concepts utilised in language and literature?

2. How are colour concepts employed symbolically in literature, and what cognitive or emotional effects do these symbolic uses have on readers?

3. How is the absence of colour in literature perceived by readers?

To answer these research questions, this Element takes an interdisciplinary approach, linking cognitive science, psychology, and literary studies to reveal how colours shape thought, emotion, and literary expression. It is organised into three main sections, each offering distinct insights that together advance the Element’s central aims.

Section 2 explores how languages across cultures identify and categorise colours, revealing near-universal patterns in colour hierarchies. It establishes that colour terms are deeply rooted in metaphorical expressions and carry strong emotional connotations across languages, providing a foundation for the linguistic exploration of colour concepts. It explores how certain colours are tied to universal cognitive processes that transcend cultural boundaries, while others are more culturally specific. In addition, this section examines how, in literary fiction, authors draw on cultural colour symbolism to depict characters’ inner emotional states, as well as their moral qualities and flaws, which has the potential to reinforce these traits schematically in readers’ minds. This section highlights how specific colours act as symbolic markers in literature, guiding readers’ emotional and conceptual engagement with characters.

Section 3 links metaphor and psychology. Using Pager-McClymont’s model of pathetic fallacy (Reference 55Pager-McClymont2021a, Reference Pager-McClymont, Pöhls and Utudji2021b, Reference Pager-McClymont2022, Reference Pager-McClymont2023), it examines how this literary technique maps emotional experiences to colourful environmental descriptions. By integrating findings from psychology on colour and emotion with literary analysis of pathetic fallacy, this research reveals a clear correspondence between scientific and literary representations of mood. Going beyond general links between psychology and language, this section highlights how textual uses of colour reveal experiences of discomfort and uneasiness, with bottom-up mappings of discomfort is brown and uneasiness is grey. The contributions of this section lie in its interdisciplinary approach, highlighting how colour can influence readers’ emotional responses and exploring the potential of creative metaphors to enrich understanding and engagement.

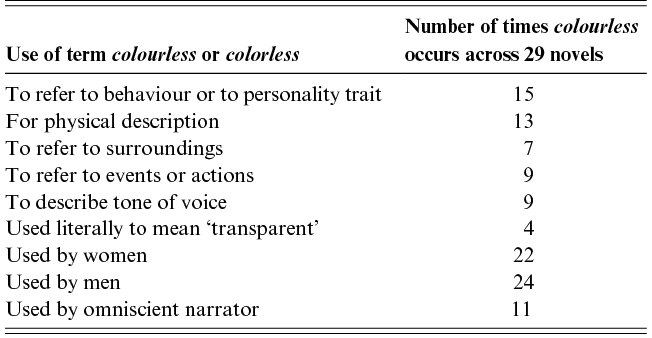

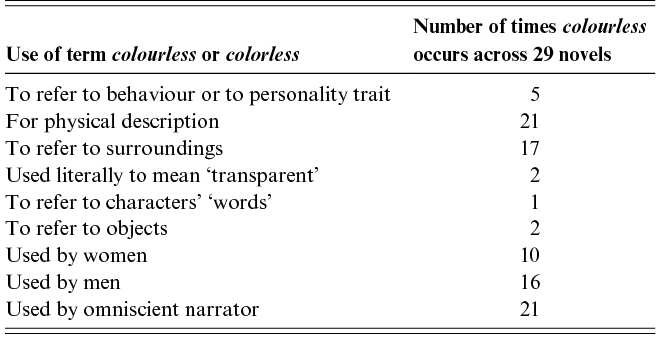

Section 4 delves into the often-overlooked concept of colourlessness or absence of colours and its impact on perception, using Modernist literature (The Modernist Literature Project Corpus) as a case study. Utilising corpus linguistics, this section uncovers how colourless descriptors are used figuratively to evoke mood, tone, and emotional detachment, revealing that the absence of colour is as meaningful as its presence. The findings convey that colourless is predominantly used negatively in Modernist texts, often to describe characters and their surroundings. This finding is notable for showing the cognitive and emotional significance of ‘non-colours’, offering insight into the ways readers may respond to and interpret literary texts.

Each section contributes a unique perspective, showing that colours are more than mere visual stimuli – they play a central role in cognitive and emotional processing and are key components of language and literary expression. By combining literary criticism with cognitive linguistics and psychological research, this Element provides a focussed interdisciplinary analysis of colour, illuminating how humans perceive, conceptualise, and interpret colours specifically within language and literature.

This Element is transformative in its approach because it investigates colour concepts across multiple fields – literary studies, psychology, and corpus linguistics – while consistently employing cognitive linguistics as the central analytical framework. This Element considers how colours function as more than decorative details, suggesting that they may influence readers’ mental representations of scenes, characters, surroundings, and events – a connection explored in depth through the analyses in subsequent sections. By drawing on multiple disciplines, this research provides a more nuanced understanding of colour in literature, with insights from each field integrated and interpreted through cognitive linguistic frameworks. For example, research in psychology has shown that certain colours tend to evoke specific emotional responses, providing empirical context for our literary analysis. The research findings presented in this Element go beyond mere description by employing cognitive linguistics to show that colour concepts influence how readers mentally construct and engage with texts.

To clarify the systematic approach underlying this Element, each section applies complementary methods – literary analysis, cognitive linguistics, corpus linguistics, and psychology – in a coordinated framework. Literary analysis identifies patterns of colour usage and symbolic functions, cognitive linguistics maps conceptual associations, psychological studies illuminate emotional and perceptual responses, and corpus linguistics provides empirical support across texts. By integrating these approaches, the Element ensures that insights from one field inform and reinforce those from another, creating a coherent methodology for examining how colour shapes both the structure of literary texts and readers’ cognitive and emotional engagement. This framework also offers a replicable model for future research, demonstrating how interdisciplinary analysis can be systematic, cumulative, and adaptable to other aspects of literary study.

2 Colour Concepts: From Verbal to Cognitive Processes

This section lays the linguistic and cultural groundwork by showing how colour concepts can activate schemas and conceptual mappings, preparing the way for the psychological and metaphorical analyses of Section 3. This section is organised as a cline that moves from the linguistic categorisation of colours to their interpretive potential in literary texts, foregrounding the cognitive linguistic perspective that meaning arises through conceptual structures and schemas. It begins with the language of colour, examining colour lexemes, their semantic ranges, and idiomatic expressions, while also attending to the cross-cultural variation that demonstrates how different communities segment and label the colour spectrum. From this foundation, the section turns to the cognitive and cultural associations between colour and emotion, showing how affective meanings are not inherent properties of colours but emerge through entrenched conceptual mappings and cultural models. The final section focusses on literature as a domain in which colour lexemes extend beyond their descriptive function to operate symbolically, which can activate, reshape, or even challenge established schemas. Drawing on cognitive linguistic frameworks such as Schema Theory and Conceptual Metaphor Theory, this section emphasises how colour meanings are constructed through conceptual mappings, cultural models, and schema activation, demonstrating that colour lexemes are not fixed labels but dynamic resources for meaning-making. In this way, the section progresses from analysing colour as a matter of meaning, to understanding it as a vehicle of perception and emotional resonance, and finally to interpreting it as a literary and cultural resource with the power to complicate or transform established ways of seeing.

2.1 The Language of Colours

Scholarly approaches to the examination of the linguistic and literary realisation of colour in literary discourse are addressed in this Element. Beyond the myriad of terms that identify primary (red, yellow, and blue) and secondary colours, there are semantically related words such as bright and luminous, which also possess significance in modern languages. The origin of the naming of colours across distinct and diverse cultures occurred in similar order: black, white, red, green, yellow, and blue (Dedrick, Reference Dedrick1998; Biggam and Kay, Reference Biggam and Kay2006; Biggam et al., Reference Biggam, Hough, Kay and Simmons2011; Loretto et al., Reference Loreto, Mukherjee and Tria2012; Kaskatayeva et al., Reference Kaskatayeva, Mazhitayeva, Omasheva, Nygmetova and Kadyrov2020). The colour spectrum pervades not just the modern lexica and the visual world but also our emotions, perceptions, and cognition.

Colours and related terms are often found in linguistic devices such as idiomatic and conceptual metaphors – although the latter, as we argue in this section, are not merely linguistic devices. Idioms containing colour concepts are widely used in spoken discourse, often carrying strong positive or negative evaluations. These linguistic constructions allow one concept to be transferred or mapped onto another so that we can be tickled pink when happy or green with envy when jealous. The emotional associations generated by colour concepts and descriptors vary amongst spoken languages and are rooted in native cultures (Hupka et al., Reference Hupka, Zaleski, Otto, Reidl and Tarabrina1997). In contrast to English, Germans would be yellow with envy (gelb von Neid) and if they had too much to drink they would be blue (blau sein). Some colour-related idiomatic expressions are the same across language, but colour descriptors often have varying connotations across cultures, and it is key to acknowledge that there are nuances in cultural colour perception. For example, in French the idiomatic phrase to express rage is être vert de rage (to be green with rage) whereas in English rage is associated with red. Similarly, avoir une peur bleue (to have a blue fear) associates blue and fear. In English blue tends to represent sadness (to feel blue) or feature more colloquial risqué ideas such as to tell blue jokes. This illustrates the varied linguistic and cultural associations of colour in discourse and it demonstrates how deeply intertwined colours are with emotion, reflecting both universal patterns and culturally specific nuances across languages.Footnote 1

2.2 Colours, Cognition, and Emotions

Colours are an inherent part of our surroundings and impact how we view the world – though it is worth pointing out that colour perception can vary amongst individual (i.e., turquoise is often debated to be green or blue) and some individuals do not perceive colours due any level of blindness. Nevertheless, colours are frequently used to express emotions as discussed earlier, or to express other abstract concepts (i.e., something unexpected is out of the blue, something uncertain is a ‘grey area’, or being unaware of something is to be in the dark). The association of colours with emotions can be cultural and/or social. When colours and emotions occur in tandem, the focus is on the abstract symbolism of the colour rather than on any – and perhaps more concrete – visual or linguistic characteristics (Jonauskaite et al., Reference Jonauskaite, Abu-Akel, Dael, Oberfeld, Abdel-Khalek, Al-Rasheed, Antonietti, Bogushevskaya, Chamseddine, Chkonia, Corona, Fonseca-Pedrero, Griber, Grimshaw, Hasan, Havelka, Hirnstein, Karlsson, Laurent, Lindeman, Marquardt, Mefoh, Papadatou-Pastou, Pérez-Albéniz, Pouyan, Roinishvili, Romanyuk, Salgado Montejo, Schrag, Sultanova, Uusküla, Vainio, Wąsowicz, Zdravković, Zhang and Mohr2020a: 18; see also Hupka et al., Reference Hupka, Zaleski, Otto, Reidl and Tarabrina1997; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Shu and Mo2014). For example, in the United Kingdom, the colour white is worn by a bride, whereas in India it is the colour of mourning and brides wear red.

For cognitive stylisticians, style is not primarily a linguistic phenomenon but, rather, a social and ideological one. Hence, the persistent matching of one colour (e.g., red) with one emotion (e.g., anger) can help to build a schema (e.g., ‘red equals anger’, see Hupka et al., Reference Hupka, Zaleski, Otto, Reidl and Tarabrina1997). In such instances, the correspondence between a given colour and its corresponding emotion is conceptual in the sense that it reflects the ways in which we interpret the world. Palmer and Schloss (Reference Palmer and Schloss2010) show that people easily link colours with emotions and many of these associations are analogous across cultures. There is a high-level of cross-cultural similarities between colour and emotion perceptions, and close geographic and strong linguistic connections between languages produce similar levels of association (Jonauskaite et al., Reference Jonauskaite, Abu-Akel, Dael, Oberfeld, Abdel-Khalek, Al-Rasheed, Antonietti, Bogushevskaya, Chamseddine, Chkonia, Corona, Fonseca-Pedrero, Griber, Grimshaw, Hasan, Havelka, Hirnstein, Karlsson, Laurent, Lindeman, Marquardt, Mefoh, Papadatou-Pastou, Pérez-Albéniz, Pouyan, Roinishvili, Romanyuk, Salgado Montejo, Schrag, Sultanova, Uusküla, Vainio, Wąsowicz, Zdravković, Zhang and Mohr2020a). The effect that context and culture have on mental states and emotions in colour-related expressions is significant as the interpretation, perception, and connotation can vary cross-culturally. Through online surveys, Jonauskaite et al. (Reference Jonauskaite, Wicker, Mohr, Dael, Havelka, Papadatou-Pastou, Zhang and Oberfeld2019) investigate colour–emotion pairings amongst 711 native English, German, Chinese, and Greek speakers. Participants were asked questions concerning 12 colour terms and 20 discrete emotions, resulting in 240 colour–emotion pairs. The researchers concluded that variances in the results could be partially attributed to different colour metaphors that exist in the native language and their resulting interpreted meaning. Colours may generate different associations because of the schema (or mental construal) that is produced. As mentioned previously, the idiom green with envy is part of the English-speaking culture. In Russian, there are two options: to be white with envy if they are feeling compassionate or black with envy when expressing negative or spiteful emotions. The mental representation of colour varies across languages, as there is no globally acknowledged schema for specific emotions. Research by Jonauskaite et al. (Reference Jonauskaite, Parraga, Quiblier and Mohr2020b) on colour–emotion associations suggests there is a human universal basis, but no associations are shared at 100%, thus also highlighting the subjective and unique processing of emotions.

The correspondence between colours and emotions can thus be metaphorical, allowing individuals to draw on shared concepts (colours) to convey a more personal or subjective concept (emotions). This aligns with Lakoff and Johnson (Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980: 153) who argue that ‘metaphor is primarily a matter of thought and action and only derivatively a matter of language’. This implies that although metaphors are usually considered thought processes, they primarily frame our perception of the world by associating concepts with one another. During the reading process, the use of colours to describe elements of a scene such as a room, an item or even a character, contributes to readers’ mental representation of the scene. In fact, depending on readers’ personal and subjective experience and the culture or society in which they live, their favouring of one colour over another might impact their views of the scene being read. Although the positive and negative association of colours is cultural, personal and thus subjective, there is a consensus amongst cognitive researchers that certain colours are typically associated with specific concepts across cultures and languages. Particularly in the field of metaphor research, positive emotions are typically associated with the idea of light (a bright day), and negative emotions with darkness (dark thoughts) (Arnheim, Reference Arnheim1969; Lakoff and Johnson, Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980; Meier and Robinson, Reference Meier and Robinson2005; Forceville and Renckens, Reference Forceville and Renckens2013). This is in agreement with anthropologists Berlin and Kay (Reference Berlin and Kay1969; see also Kay et al., Reference Kay, Berlin and Merrifield1991) who argue that there is a categorisation of colours across languages, the main two being black which is often seen as negative and white often being seen as positive.

This contrast is also prevalent in literature, particularly in the representation of key events or characters, where colour choices can contribute to the activation of underlying schemas and guide readers’ interpretations. For example, in Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (Reference Brontë1847/2021), Cathy’s two love interests Heathcliff and Edgar are portrayed as opposite of each other (Le Fanu, Reference Le Fanu2003; Imsallim, Reference Imsallim2014). Heathcliff is tumultuous and described with dark attributes as shown in the passages: ‘he little imagined how my heart warmed towards him when I beheld his black eyes withdraw so suspiciously under their brows’; and ‘he is a dark-skinned gipsy in aspect, in dress and manners a gentleman’). On the other hand, Edgar is calm and devoted to Cathy. He is described with light and fair attributes, which is a source of jealousy for Heathcliff. This is expressed in the sentences: ‘I must wish for Edgar Linton’s great blue eye’, and ‘I wish I had light hair and a fair skin, and was dressed and behaved as well’. The two men’s opposite personality traits are reflected in their physical appearances: Heathcliff is portrayed negatively through darker attributes, and Edgar is represented positively with lighter traits. Although not a Black man, Heathcliff is racialised and treated as a member of a lower class (Soberano, Reference Soberano2023: 147; Althubaiti, Reference Althubaiti2015: 202) – hence the term ‘gipsy boy’ to describe him. Throughout the novel, the use of those colourful oppositions extends to Cathy’s relationship with the two men.

These juxtaposed colour tones are at times symbolic and unique to a particular narrative or attributed with broader conceptual significance in the overall storyline. Such symbolism illustrates how colour in literature is more than descriptive: it participates in meaning-making by cueing readers to interpretive patterns and narrative schemas. Colours are often used in literature not just to describe, but also to evoke conceptual and emotional responses (see Section 3), reflecting cultural models and guiding the activation of schematic knowledge. Section 2.3 demonstrates how powerful and symbolic colours can be in the varied literary examples discussed, highlighting their role in structuring readers’ understanding and extending beyond literal representation.

2.3 Colours, Schemas, and Literature

Drawing on the principles of Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL), we conceptualise meaning-making as occurring along a continuum, with culture (the generalised, shared systems of meaning) at one end, and individual interpretation (the particular) at the other (Martin and White, Reference Martin and White2005: 25). Literature occupies a central position on this spectrum, functioning as a semiotic artefact that draws on culturally embedded meanings while simultaneously inviting diverse individual responses. As Butt and Lukin (Reference Butt, Lukin, Halliday and Webster2009: 214) observe, ‘textual organisation is metonymic (our emphasis) with respect to complex cultural configurations which may be, or may not be, explicitly encoded elsewhere in the culture’. In this sense, literature may be understood as offering partial, indirect representations of cultural knowledge. This dynamic interplay between cultural resources and individual interpretation is further illuminated by Schema Theory, which posits that a reader’s engagement with a text is shaped by pre-existing cognitive structures and conceptual knowledge – that is, schemas. These schemas, comprising socially acquired background knowledge, are continuously ‘reinforced’ or ‘challenged’ in the act of reading (Cook, Reference Cook1990: 244). Like SFL, Schema Theory foregrounds the dialectical relationship between individual cognition and broader socio-cultural semiotics: schemas are shaped by culture and enacted by individuals, just as linguistic choices in texts are both socially patterned and personally interpreted. In stylistic analysis, schemas thus serve as ‘skeletal frameworks’ of conceptual knowledge that help explain how readers process and interpret literary texts (Wales, Reference Wales2011: 376; see also Bartlett, Reference Bartlett1995), offering a valuable complement to SFL’s concern with the cultural patterning of language. This section explores the metonymic potential of colour representation in literature through examples from American and French texts. Drawing on Schema Theory and SFL, we adopt a bottom-up analytical approach: we first examine how colours function within the immediate textual environment before situating their meanings within broader cultural and ideational schemas. The aim is to demonstrate how the language of colours can shape not just meaning, but also mental representation of a scene or textual element beyond the colour itself.

Our first example is Alice Walker’s epistolary novel The Color Purple (1982). In this context, Celie’s longing for a purple dress reflects her association of the colour purple with royalty (Krafts et al., Reference Krafts, Hempelmann and Oleksyn2011: 9). However, in Letter 12 near the end of the novel, Shug (Celie’s friend and love interest) states, ‘I think it pisses God off if you walk by the color purple in a field somewhere and don’t notice it’. In this instance, the colour purple emphasises the importance of small pleasures in life, which Celie has had too little of because of the hardship and abuse she has experienced (Wu and Wei, Reference Wu and Wei2022; Anwer, Reference Anwer2023). Four years before the publication of the novel, over 100,000 women donning shades of purple marched in Washington, D.C. for the Equal Rights Amendment (Bennetts, Reference 49Bennetts1978). Since then, in America, purple has come to represent women’s strength and resilience against various forms of sexual, verbal, and political abuse and neglect. In The Color Purple, the colour purple may not, on its own, prompt readers to fully activate a royalty or abuse schema, but American readers familiar with or particularly attuned to domestic abuse may draw on their contextual knowledge to activate this latent schema. Indeed, in today’s America, the colour purple is used every October in campaigns and advertisements for Domestic Violence Awareness Month. Should the reader activate this schema via textual cues, then it will become reinforced.

In certain literary narratives, colours are repeated, creating a link between characters in addition to being a leitmotif. Such an example can be observed in Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (Reference Flaubert1857/2021), in which Emma Bovary, a daydreamer often lost in her fantasies, has an affair with a younger man named Leon. The colour blue is omnipresent and there are fifty-six occurrences in the novel, reminding readers that Emma tends to have her ‘head in the sky’ as well as it being the colour of Leon’s eyes (Tipper, Reference Tipper1989: 105). Furthermore, both characters are often described as wearing blue clothing when together; there are numerous items of décor, such as curtains or vases, that are also blue. Examples from the story include: ‘his legs, in blue stockings’, ‘this letter, sealed with a small seal in blue wax’, ‘in post chaises behind blue silken curtains’, ‘she wanted for her mantelpiece two large blue glass vases’, and ‘she wore a small blue silk necktie’. The omnipresence of the colour blue in Madame Bovary represents the relationship between Emma and Leon and its significance for Emma. Specifically, it symbolises Emma’s aspiration towards the absolute or, put more simply, her dreams (Knapp, Reference Knapp1980: 13). In this respect, the schema of the prototypical French reader can become reinforced since blue explicitly symbolises liberty and freedom in the French flag (Tipper, Reference Tipper1989: 106; Joao Cordeiro, Reference Joao Cordeiro, Bogushevskaya and Colla2015: 213). For the two French authors of this element, the link between blue and freedom gets very quickly activated upon their reading of Madame Bovary. While non-French readers may not activate the same schema, blue tends to generally represent possibility and infinity – a schema that many narratives activate. In Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, for instance, the colour blue – associated with the sea in that novel – represents Edna Pontellier’s fantasised life breaking from gendered duties, much like Emma Bovary. These examples illustrate Wales’s argument (Reference Wales2011: 277) that colours function as leitmotifs in Western literature.

In other narratives, colours are used to convey an implicit message to readers, acting as a more abstract leitmotif. This is the case for Melville’s Moby Dick (Reference Melville1851/1988), in which scholars interpret the whiteness of the sperm whale as Ahab’s search for spirituality, since white is often associated with Christianity (Stoll, Reference 57Stoll1951; Redden, Reference Redden2011). In chapter 42 of the novel, entitled ‘The Whiteness of the Whale’, Melville (Reference Melville1851/1988: 212) writes:

Whiteness is not so much a color as the visible absence of color, and at the same time the concrete of all colors: it is for these reasons that there is such a dumb blankness, full of meaning, in the wide landscape of snows – a colorless, all color of atheism which we shrink.

This passage features the lexical field of whiteness (‘snows’, ‘absence of color’, ‘blankness’, and ‘colorless’ – for a discussion on colourless, see Section 4). This demonstrates how important the use of the colour white is throughout the novel. It also illustrates the significance of the choice of colour for the whale and what it means for Ahab’s chase: white is the absence of colour, mirroring Ahab’s deprivation of faith as shown by the phrase ‘color of atheism’ in the earlier passage (Callahan, Reference Callahan2003). Interestingly, Melville plays with the meaning potential inscribed in the American nineteenth-century context in which white represented purity and innocence, exemplified by the tradition of white wedding dresses at that time. In this context, readers may activate the schema whiteness is innocence (Kha and Nhung, Reference Kha and Nhung2024: 43), meaning that Ahab’s actions will be perceived as particularly evil.

In literature, the colour pink often characterises innocence. In Lolita, the pink attire worn by Lolita greatly contrasts with the sinister material of the novel. In this case the omnipresence of the colour pink contributes to dramatising the plot. For instance, the twelve-year-old Lolita is perceived as a sexual object because she wears pink; the colour is a symbol of youth, making Lolita a sexual object in the eyes of Humbert the paedophile (Plevíková, Reference Plevíková2016: 74). The fact that Humbert is attracted to her bright, youthful clothing is metaphorically dark in itself. The colour pink works towards characterisation because the author seems to use their cultural schemas associating pink and innocence for their reader to experience the tension between innocence and duplicitousness in the text. Lolita offers a site of tension between schema reinforcement and schema disruption: the colour pink, according to a near-universal schema, represents youth and innocence (Koller, Reference Koller2008: 396). Conversely, the very subject matter of the novel turns pink as the colour of sinfulness, thus potentially challenging the readers’ schemas. Literature articulates the dialectic relationship between the universal and the individual. To understand a text, we typically activate our existing schemas (top-down approach). Yet, when reading the text, textual cues may activate, reinforce, refresh, or disrupt these existing schemas (bottom-up approach).

Finally, colours can be used to convey political ideologies such as parties (Burriss and McComb, Reference Burriss and McComb2001). For instance, in the American system, red typically represents the Republican party, whereas blue represents the Democrats. Communism is equally associated with the colour red. This also applies to political literature such as Stendhal’s Le Rouge Et Le Noir (The Red and the Black) (1830/2020), which sees the evolution of the protagonist Julien, who aims to rise above his humble upbringing to reach higher social and political status. Pollard (Reference Pollard1981) argues that since this bildungsroman was written during the French Restoration, red is likely to represent Jacobinism and black represents Clericalism; both colours are frequently referenced throughout the novel. Alternatively, red can be thought to reflect Napoleon’s glory, whereas black symbolises the Restoration. The polarity of the two colours reflects Julien’s political dilemma and the temptation he faces to betray his beliefs for an elevated social status. What this, and the other previous examples, suggest is that, in the context of colour in literature, schema activation relies on a pairing of a colour (something concrete) and an ideal or an ideology (something abstract). In this sense, colour symbolism – much like Conceptual Metaphor Theory (hereafter CMT) – relies on a stimulus–response pair, summarised by neuroscientists as ‘neurons that fire together wire together’ (see Section 3 for a more in-depth discussion on CMT). When a colour activates the same schema repeatedly, the schema becomes strengthened as a response.

This section highlights the entanglement between schemas and the use of colour concepts as symbols in literature. Since literary works are produced within a specific context with its specific meaning-making conventions, it would be surprising if literary works did not (re)produce some of the meanings already contained in the culture. After all, as Jean-Paul Sartre argues (Reference Sartre1974: 275) that the writer cannot escape their ‘insertion in the world, and [their] writing are the very type of a singular universal’. What stems from these observations is that the reading experience ultimately mobilises readers’ schemas, relying on their existing mental reservoir of knowledge. The reading experience can either reinforce these schemas by representing them in a similar way or, perhaps less frequently, disrupt them by re-presenting them in a new way. In any case, colour symbolism relies, like CMT, on associative thinking: one concept becomes linked to another through iterative use.

2.4 Conclusion

In conclusion, this section has demonstrated that colour concepts cannot be reduced to simple descriptive terms; rather, they operate as complex linguistic and cultural resources. We showed that colours often function pragmatically, particularly when embedded in idiomatic expressions, where they convey affective and culturally specific meanings. This discussion highlighted how colour is deeply entangled with emotion, not only reflecting individual perception but also embodying shared cultural models. Building on this, the section illustrated how colour lexemes, by virtue of their descriptive precision and affective resonance, are particularly salient in literature, where they extend beyond scene-setting to act symbolically, index broader cultural schemas, and at times challenge entrenched associations. Taken together, the analyses underscore the cognitive linguistic perspective that colour meanings are constructed through conceptual mappings and schema activation, shaping both mental representations and interpretive practices. Thus, the section has traced a progression from the linguistic encoding of colour to its emotional and cultural resonances, and finally to its interpretive force in literature, showing how colour operates as a dynamic site of meaning-making at the intersection of language, culture, and cognition.

The decision to begin the Element with this cline, and to ground the analysis in examples from literature, is intentional. Literature provides a particularly rich site in which to observe both the perception and reception of colourful concepts, offering evidence of how colour terms are processed, interpreted, and extended beyond literal description. Starting with this range of examples establishes a foundation for the sections that follow, which approach colourful concepts from different but complementary angles. Section 3 considers colour in relation to metaphor and psychology, with a focus on pathetic fallacy as a point where natural description and emotional projection intersect. Section 4 shifts attention to the absence of colour, examining the lexeme colourless and its effects through a corpus-based study of Modernist literature. Taken together, these sections demonstrate the variety of contexts in which colourful concepts can be explored and the different kinds of impact they have, moving from lexical description to cultural resonance and literary interpretation.

3 Colour Concepts, Metaphor, and Psychology

This section builds on the schema analyses of Section 2 by examining how colour concepts operate metaphorically and psychologically, mapping emotions onto both vivid hues and muted tones. By analysing the metaphorical effects of colours on reader perception, Section 3 paves the way for Section 4’s focus on the literary significance of colourlessness. In this section, we use pathetic fallacy, which links emotions to surroundings, as a case study. Our environment generally impacts our experiences because of the comfort (or lack thereof ) it brings us (Grandjean et al., Reference Grandjean1973; Persinger, Reference Persinger1975; Cunningham, Reference Cunningham1979; Howarth and Hoffman, Reference Howarth and Hoffman1984; Baylis et al., Reference Baylis, Obradovich, Kryvasheyeu, Chen, Coviello, Moro, Cebrian and Fowler2018, amongst others). Colours are an inherent part of our surroundings and play ‘an important role in our life. […] Our experience with objects within our surroundings has a lot to do with our response to their colours. It is a visual language therefore it can give alert or warning, to reflect mood or to represent emotions’ (Kumarasamy et al., Reference Kumarasamy, Devi Apayee and Subramaniam2014: 2). Pathetic fallacy (henceforth PF; a term coined by Ruskin (Reference Ruskin1856/2012)) is a literary technique that links surroundings and emotions, and as such PF can be used to underpin how emotions can be mapped onto surroundings. We use examples in literature taken from Pager-McClymont’s corpus of PF (Reference Pager-McClymont, Pöhls and Utudji2021b) to evidence how this is achieved and link our findings to existing research in psychology, revealing that specific colours, colour descriptors, and tones are part of our conceptualisation of emotions.

3.1 Defining Pathetic Fallacy as a Metaphor

Pager-McClymont’s recent works (Reference 55Pager-McClymont2021a, Reference Pager-McClymont, Pöhls and Utudji2021b, Reference Pager-McClymont2022, Reference Pager-McClymont2023) develop a model of PF which is formulated through an interdisciplinary lens. This was prompted by the necessity for a contemporary and methodical conceptual framework for PF, a concept featured in the English National Curriculum (Department for Education, 2013a, 2013b) and integrated into educational curricula. This model was constructed based on empirical data obtained from surveys administered to English educators. Notably, when asked to articulate their understanding of pathetic fallacy, 53% (n = 134) of respondents interpreted it as the projection of human emotions onto nature, while 36% construed it as a form of personification. The absence of a precise definition by the Department for Education and other educational materials produced by exam boards such as AQA or Edexcel leaves interpretation up to individual educators and education boards, thereby contributing to variations in how PF is conceptualised, leading to discrepancies surrounding its definition (for a more in-depth literature review, see Pager-McClymont (Reference 55Pager-McClymont2021a)).

Pager-McClymont’s construction of the PF model is underpinned by foregrounding theory (Miall and Kuiken, Reference Miall and Kuiken1994; Van Peer, Reference van Peer2007; Leech, Reference Leech2008), which elucidates how linguistic elements stand out within a text by means of parallelism, external deviation from linguistic norms, or internal deviation from established textual patterns. PF is defined by Pager-McClymont as the projection of emotions onto surroundings by an animated entity, whether implicitly or explicitly depicted in the text. This definition necessitates three criteria: the presence of an animated entity (implicit or explicit); vivid descriptions of the surroundings to facilitate readers’ recognition of scene depictions and the mirroring effect of PF; and the depiction of emotions. Emotion encompasses various responses to internal or external events, with positive or negative valence, spanning mood, preferences, personality traits, and affective states, whether explicitly or implicitly conveyed in texts. Furthermore, three linguistic indicators akin to Short’s (Reference Short1996: 263) ‘linguistic indicators of viewpoint’ are identified for PF, encompassing imagery (figures of speech), repetition (lexis or syntax), and negation (lexical, morphological, and adverbial). Additionally, to date six effects of PF on narratives have been identified: foreshadowing; explicit communication of emotions; character development; building ambience; generating humour; and influence on readers’ empathetic responses depending on specific mappings.

Pager-McClymont argues that PF is an extended metaphor (meaning that it can run on several paragraphs of text, as opposed to a single sentence or phrase, see Pager-McClymont, Reference Pager-McClymont, Pöhls and Utudji2021b: 102) and can thus be analysed in terms of Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT). One of CMT’s claims is that ‘metaphor is primarily a matter of thought and action and only derivatively a matter of language’ (Lakoff and Johnson, Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980: 153). This suggests that metaphors are part of our processing of the world around us before they are verbalised. CMT proposes that one conceptual domain a (the target domain) is understood in terms of another conceptual domain b (the source domain), and thus the metaphor is the cross-domain mapping (meaning correspondence) and can be phrased as such: a is b (Lakoff and Johnson, Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980: 250; Kövecses, Reference 53Kövecses2002: 5–6).

Metaphors that feature an emotion as a target domain (i.e., instances of PF) are labelled ‘emotion metaphors’ (Kövecses, Reference Kövecses and Gibbs2008: 380). Kövecses explains that there is a link between conceptual metaphors and conceptual metonymies (a concept or object being referred to by substitution to one of its attributes (Wales, Reference Wales2011: 267–268)). Indeed, certain physical manifestations of emotions or behaviours such as tears or turning away are ‘conceptual metonymies’ of emotions: they are single elements representing the emotion (Kövecses, Reference Kövecses and Gibbs2008: 382). This is important to PF, as emotions can be present implicitly, thus requiring to be inferred. Conceptual metonymies of emotions allow readers to infer how a character might be feeling without the emotion needing to be explicitly expressed. For example, in the sentence ‘she thought she missed him, and tears ran down her cheeks as she walked in the rain’, the tears are metonymies of sadness, and the rain mirrors this sadness, as both the tears and the rain have the same downward motion.

Kövecses (Reference Kövecses and Gibbs2008: 382–383) also suggests that there could be a ‘master metaphor’ of emotions. According to his findings, primary emotions such as love or anger share a source domain: natural forces. This is salient to PF, as the emotions expressed are the target domain and they are understood through the surroundings in the mirroring process. Consequently, the master metaphor of PF is emotion is surroundings (Pager-McClymont, Reference Pager-McClymont2022), and it can be linked to known conceptual metaphors such as Kövecses’s emotion is natural forces (Reference Kövecses and Gibbs2008: 381) and Shinohara and Matsunaka’s emotion is external meteorological/ natural phenomenon that surrounds the self (Reference Shinohara, Matsunaka, Forceville and Urios-Aparisi2009: 270). Others are linked to Lakoff and Johnson’s ‘orientational metaphor’ (Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980: 10–11) emotion is vertical orientation, as well as more creative metaphors such as emotion is colour tone. This latter master metaphor is the focus of this section.

To analyse how the source domain (colours) influences readers’ perception of the target domain (emotions), we observe the saliency of the source domain. Stockwell (Reference Stockwell1999: 138) argues that saliency is ‘more peculiar to the individual’s worldview and culture, accumulated through social experience’, thus the most salient aspect of the source domain might vary amongst individuals or texts. Stockwell (Reference Stockwell1999: 137) suggests that in the example of the ‘image metaphor’ given by Lakoff and Turner (Reference Lakoff and Turner1989: 90) ‘my wife … with the waist of an hourglass’, the most salient characteristic perceived by readers is likely to be the shape of the hourglass as opposed to the cold glass it is made of or its sand. Therefore, in the analysis of PF as a conceptual metaphor, we discuss how the most salient characteristics of the source domains enable readers to mentally represent the emotions expressed (target domain). We also discuss how the cross-domain mapping between the emotion and the colour contributes to these effects of PF as identified in Pager-McClymont’s model.

3.2 Emotions Are Colour Tones: Shades of Pathetic Fallacy

Our surroundings are significantly portrayed through colours (with the exception of individuals on the spectrum of (colour-)blindness). Colours are also used to express our emotions on a day-to-day basis: to ‘feel blue’, to ‘see red’, to be ‘green with envy’ (Jonauskaite et al., Reference Jonauskaite, Parraga, Quiblier and Mohr2020b: 1). As discussed in Section 2.1, although these associations can vary from one culture or individual to another. Despite this, the association of colours and emotions can also occur naturally due to ‘perceptual pairing’: they are associations that arise directly from sensory experience (specifically, how the perception of a colour (e.g., seeing a red patch) triggers emotional or cognitive responses (based on Wang et al., Reference Wang, Shu and Mo2014: 153; Jonauskaite et al., Reference Jonauskaite, Parraga, Quiblier and Mohr2020b: 3)). Thus, emotional concepts are linked to abstract representations of colour concepts, rather than to specific perceptual or linguistic characteristics of colour, as we evidence later.

3.2.1 Good Is Light and Bad Is Dark

Metaphor researchers consensually discuss positive emotions in terms of ‘light’ and negative emotions in terms of ‘dark’, leading to the cross-domain mappings good is light (i.e., ‘a bright day’) and bad is dark (i.e., ‘dark thoughts’) (Arnheim, Reference Arnheim1969; Lakoff and Johnson, Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980: 50–53; Lakoff et al., Reference Lakoff, Espenson and Schwartz1991: 190; Meier and Robinson, Reference Meier and Robinson2005; Forceville and Renckens, Reference Forceville and Renckens2013). According to Arnheim (Reference Arnheim1969: 313), these two associations ‘go as far back as the history of man’, and the affective link and contrast between light and darkness is due to the symbolic representation of good and evil. The texts included in this research feature multiple examples of colour tones as part of the surroundings that illustrate emotions. Most examples can be divided into two categories: light and dark. Therefore, the master metaphor that emerges is emotion is colour tone, and since the colour tones are part of the surroundings, this mapping falls under the master metaphor of PF emotion is surroundings (see Pager-McClymont, Reference Pager-McClymont, Pöhls and Utudji2021b: 269–274).

Firstly, the mapping bad is dark is prevalent. An example of this can be observed in Act II Scene II of Macbeth (Shakespeare, Reference Shakespeare1606/2014: 34–35):

This scene is Lennox’s description of the night King Duncan was murdered by Macbeth. The audience knows the murder occurred, but Lennox does not. The three criteria of PF according to Pager-McClymont’s definition are present: Lennox is the animated entity, and he expresses his anguish and worry over events of the nights through negative terms such as ‘terrible’, ‘woeful’ or ‘lamentings’. This negative feeling is reflected by the dark surroundings (i.e., ‘the night has been unruly’ or ‘obscure bird’). Lennox’s bad feeling of anguish is the target domain, and the dark atmosphere of the scene is the source domain, thus providing the metaphor bad is dark. In this instance, the opaque dark tone of the surroundings is the most salient characteristic of the source domain mapped onto the anguish expressed by Lennox (the target domain). This cross-domain mapping builds ambience (Stockwell, Reference Stockwell, Stockwell and Whiteley2014: 365) and reinforces the suspense already present in the scene due to the dramatic irony or ‘suspense paradox’ (Carroll, Reference Carroll, Vorderer, Wulff and Friedrichsen1996: 147–150) of Lennox not knowing of Duncan’s murder whilst the audience is aware of it. Indeed, suspense relies on a level of uncertainty in a scene due to characters facing conflicting situations, and the tension of the suspense only lifts when a denouement occurs (Iwata, Reference 52Iwata2009: 253; see also Carroll, Reference Carroll, Vorderer, Wulff and Friedrichsen1996). In the case of Macbeth, this occurs when the truth about King Duncan’s murder is revealed.

Secondly, the mapping good is light is equally prevalent as bad is dark. For instance, in chapter 11 of Jane Eyre (Brontë, Reference Brontë1847/2007), Jane describes her first morning at Thornhill:

The chamber looked such a bright little place to me as the sun shone in between the gay blue chintz window curtains, showing papered walls and a carpeted floor, so unlike the bare planks and stained plaster of Lowood, that my spirits rose at the view. Externals have a great effect on the young: I thought that a fairer era of life was beginning for me, one that was to have its flowers and pleasures, as well as its thorns and toils.

The three criteria in Pager-McClymont’s model of PF are present: Jane is the animated entity represented by the personal pronoun ‘I’. Her feelings about Thornhill are explicitly positive (‘gay’, ‘my spirit rose’, ‘fairer’, ‘pleasures’), as are the surroundings (‘bright little place’, ‘sun shone’, ‘window’). In fact, the metaphor ‘my spirit rose up’ is in itself enclosed in the orientational metaphor good is up (Lakoff and Johnson Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980: 10–11) to fully convey Jane’s positive emotions. In addition to this metaphor, the use of PF projects Jane’s feelings onto the ‘bright’ surroundings. In this instance Jane’s positive emotions are the target domain and the light present in the scene through the sunshine and windows is the source domain, thus generating the cross-domain mapping good is light. The passage describes Jane’s first impression of Thornhill, and this is particularly interesting, as so far in the narrative Jane has had mostly negative experiences in her life, such as living with the Reeds (her aunt and cousins) who tormented her, or struggling at Lowood charity school. However, she describes the room at Thornhill positively, thus creating a contrast with her past experiences. Indeed, a direct comparison is drawn by Jane herself between Thornhill and Lowood: ‘unlike the bare planks and stained plaster of Lowood’ or ‘fairer era of life was beginning for me’ (our emphasis). This contrast in perception of surroundings foreshadows the rest of the plot, as eventually Jane and Mr Rochester will marry and live in Thornhill. Therefore, the use of PF with the mapping good is light signposts to readers how special Thornhill is in the development of the story.

The cross-domain mappings of bad is dark and good is light are also present in The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (Stevenson, Reference Stevenson1886/2018), along with another colour metaphor: discomfort is brown (see Pager-McClymont, Reference Pager-McClymont, Pöhls and Utudji2021b: 271). The novel features a man with a split personality: Dr Jekyll, an academic, and Mr Hyde, his evil personality. As discussed, Arnheim (Reference Arnheim1969) suggests that the concept of light is associated with the concept of good, whereas the concept of dark is associated with evil. This aspect of the conceptual metaphors bad is dark and good is light is salient to the characters of Jekyll and Hyde. Indeed, the first description of both characters occurs in chapter 2 (Stevenson, Reference Stevenson1886/2018, our emphasis), in which Mr Utterson states: ‘‘this Master Hyde, if he were studied,’ thought he, ‘must have secrets of his own; black secrets, by the look of him; secrets compared to which poor Jekyll’s worst would be like sunshine’’. The colour black (darkest colour tone possible) is associated with Hyde and the notion of light through ‘sunshine’ is associated with Jekyll, who is portrayed as a respectable and good character. Therefore, the conceptual metaphors bad is dark and good is light are representative of the characters’ personalities and the contrast between the two, thus contributing to their characterisation (see also Alter et al., Reference Alter, Stern, Granot and Balcetis2016).

3.2.2 Discomfort Is Brown

In The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (Stevenson, Reference Stevenson1886/2018), good is light and bad is dark are not the only conceptual mappings between colours and emotions. Indeed, as the story progresses and the boundaries between Hyde and Jekyll’s personalities become blurred, the most prevalent colour present is brown, and it is often featured when other characters display emotions of anguish and discomfort. For instance, the passage further down is from chapter 10 and follows the Carew murder’s discovery committed by Hyde (Stevenson, Reference Stevenson1886/2018, our emphasis):

A great chocolate-coloured pall lowered over heaven, but the wind was continually charging and routing these embattled vapours; so that as the cab crawled from street to street, Mr. Utterson beheld a marvellous number of degrees and hues of twilight; for here it would be dark like the back-end of evening; and there would be a glow of a rich, lurid brown, like the light of some strange conflagration; and here, for a moment, the fog would be quite broken up, and a haggard shaft of daylight would glance in between the swirling wreaths. The dismal quarter of Soho seen under these changing glimpses, with its muddy ways, and slatternly passengers, and its lamps, which had never been extinguished or had been kindled afresh to combat this mournful reinvasion of darkness, seemed, in the lawyer’s eyes, like a district of some city in a nightmare.

The three criteria of PF are present, as Mr Utterson is the animated entity and the lexical field of death (‘pall’, ‘wreath’, and ‘mournful’) hints at Hyde committing murder. Mr Utterson displays negative feelings of anguish or discomfort (‘embattled’, ‘lurid’, ‘strange’, and ‘nightmare’). The surroundings are mostly described through spatial deixis (‘Soho’, ‘street to street’, and ‘cab’) and through colour tones. Indeed, although the idea of ‘darkness’ is also present, brown is the colour used to describe the surroundings, not black: ‘chocolate-coloured’, ‘hues of twilight’, ‘rich, lurid brown’, and ‘muddy’. Moreover, the term ‘pall’ not only reminds readers of Hyde’s crime, but it also suggests decay that is typically of an earthy brown colour. Therefore, Mr Utterson’s feeling of discomfort is the target domain mirrored by the source domain of the surroundings’ brown tones, thus creating the cross-domain mapping discomfort is brown. In this example, the brown tones of the surroundings build ambience but are also character-building. Indeed, brown is the colour obtained when all the other colours are mixed together: when light colours are mixed, light brown is obtained, when dark colours are mixed, dark brown or near-black colour is created (Edwards, Reference Edwards2004: 74). We argue that the prevalence of the colour brown in the passage following Hyde’s crime is not coincidental: it implicitly conveys Jekyll and Hyde’s mixed personalities.

Another example of discomfort is brown is implicitly featured when the potion created by Dr Lanyon and Jekyll to dissociate himself from Hyde changes colours (Stevenson, Reference Stevenson1886/2018, our emphasis):

He sprang to it, and then paused, and laid his hand upon his heart; I could hear his teeth grate with the convulsive action of his jaws; and his face was so ghastly to see that I grew alarmed both for his life and reason.

[…] I rose from my place with something of an effort and gave him what he asked.

He thanked me with a smiling nod, measured out a few minims of the red tincture and added one of the powders. The mixture, which was at first of a reddish hue, began, in proportion as the crystals melted, to brighten in colour, to effervesce audibly, and to throw off small fumes of vapour. Suddenly and at the same moment, the ebullition ceased and the compound changed to a dark purple, which faded again more slowly to a watery green.

The colours of the potion are first red, then purple, and finally green (‘first a reddish hue’, ‘changed to dark purple’, ‘watery green’). When those three colours are mixed, the colour obtained is brown (Edwards, Reference Edwards2004: 74). Dr Lanyon feels ill-at-ease with Jekyll’s behaviour and the creation of the potion (‘grew alarmed’, ‘something of an effort’). The colour brown – here the blend of all stages of the concoction – is a potential metonymy of the overall potion and its effect on the narrative. It is also the manifestation of Dr Lanyon’s discomfort, suggesting he realises the impact the potion will have on Jekyll and Hyde’s mixed personality. This example demonstrates that in literature, known conceptual metaphors such as good is light and bad is dark are present but so are more novel instances of conceptual metaphors like discomfort is brown. Each instance of metaphor associating emotions to colour concepts is an instance of PF and contributes to the process of building characters and ambience.

3.2.3 Uneasiness Is Grey

Another example of a colour metaphor is uneasiness is grey, which can be observed in chapter 9 of The Woman in Black (Hill, Reference Hill1983/2011):

The first thing I noticed on the following morning was a change in the weather. As soon as I awoke, a little before seven, I felt that the air had a dampness in it and that it was rather colder and, when I looked out of the window, I could hardly see the division between land and water, water and sky, all was a uniform grey, with thick cloud lying low over the marsh and a drizzle. It was not a day calculated to raise the spirits and I felt unrefreshed and nervous after the previous night.

The passage takes place after Arthur and his dog Spider spend a night at Eel Marsh House, where supernatural and eerie events had previously occurred. PF’s three criteria are present: Arthur is the first-person narrator (‘I’), and he explicitly expresses his feelings of uneasiness (‘I felt unrefreshed and nervous’) after the events of the night, seemingly depressed to have awoken at the house and realising the events were not a dream. The surroundings are described and the colour grey is dominant in this description (source domain), mirroring Arthur’s negative emotions (target domain). The cross-domain mapping uneasiness is grey can thus be generated. The most salient characteristic of the colour grey mapped onto Arthur’s feelings is the mix of black and white. Indeed, grey is a combination of those two tones, blurring them together, similarly to how the sea, the land, the sky, and the clouds are described in the previous extract. Additionally, the cloud and the drizzle, combined with the grey tones of the scene, could represent Arthur’s uncertainty of the events of the previous night. Indeed, his judgement can be considered as clouded or foggy because he is unsure of what happened or of what he saw or heard.

Furthermore, the idea of uncertainty and uneasiness being emphasised through grey tones is also present in chapter 1 of Dracula (Stoker, Reference Stoker1897/2013):

As we ascended through the Pass, the dark firs stood out here and there against the background of late-lying snow. Sometimes, as the road was cut through the pine woods that seemed in the darkness to be closing down upon us, great masses of greyness which here and there bestrewed the trees, produced a peculiarly weird and solemn effect, which carried on the thoughts and grim fancies engendered earlier in the evening, when the falling sunset threw into strange relief the ghost-like clouds which amongst the Carpathians seem to wind ceaselessly through the valleys.

The three criteria of PF in the model are present: the narrator describing the scene is Jonathan Harker and he is on a journey with Slovak men (hence the ‘we’ or ‘us’). Harker’s feelings of uneasiness and uncertainty are expressed through negative language (i.e., ‘weird and solemn’, ‘grim’, ‘strange relief’, and ‘ghost-like’). The scene occurs at night and the surroundings are trees, mountains, and snow. Interestingly, the dominant colour of the surroundings is grey, as it is the only colour directly named (‘greyness’). There is also a mix of two tones suggesting the overall dominance of the colour grey: the ‘darkness’ (here likely meaning black because of the night) is mixed with the ‘ghost-like’ clouds and the snow, both of which are white, thus emphasising the grey colour in the extract. Harker is not sure of where he is heading and the surroundings do not allow him to see what is around him, leading him to feel uncertain and uneasy (target domain) about his journey with the Slovaks. The grey colour of the surroundings (source domain) mirrors his uncertainty, thus generating the cross-domain mapping of PF uneasiness is grey. This correspondence has for effect to not only convey explicitly Harker’s feelings but also to build the ambience of the scene and its suspense: Harker is uncertain of what will happen, and he is uncertain of what surrounds him; thus, one could say he is in a ‘grey area’ until he privy to the details of the journey. This last point is further developed in Section 3.4.

These analyses have demonstrated that PF as a conceptual metaphor maps the characters’ emotions onto the surroundings (such as colours). Some of these metaphors are known conceptual metaphors (i.e., good is light, bad is dark) and others are more novel, such as brown is discomfort or uneasiness is grey. However, one can wonder if the association between those emotions and the specific colours of brown and grey also exists in the psychological impact of colours on human emotions. The next section aims to discuss this point and draws parallels between the correspondences observed in our analysis of literature and data from empirical studies in psychology.

3.3 Colour Surroundings and Psychology

So far in this section, the embraced position suggests that our perception of colours not only improves how we process events logically or through language but also influences our emotional responses by triggering positive or negative associations. (Sandford, Reference 56Sandford, Biggam, Hough, Kay and Simmons2011: 226–229). However, the emotional association with colours are ‘not universal, nor are they applicable to any one entire population, since they are constructed with individual as well as collective participation’ (Prado-León et al., Reference Prado-León, Avilla-Chaurand, Rosales-Cinco, Biggam and Kay2006: 204; see also Prado-León et al., Reference Prado-León, Schloss and Palmer2014). Certain studies claim that the psychological or emotional impact of colour on individuals lacks empirical support and that the topic is often misrepresented in popular culture (O’Connor, Reference O’Connor2011: 234). Mohr et al. (Reference Mohr, Jonauskaite, Dan-Glauser, Uusküla, Dael, MacDonald, Biggam and Paramei2018: 230–233) suggest that some of the discussions surrounding the emotional impact of colour on individuals are inconclusive because ‘affective connotations of colours are heterogeneous (for example, red represents anger and love) partly because they relate to different contexts’ (Soriano and Valenzuela, Reference Soriano and Valenzuela2009; Elliot and Maier, Reference Elliot and Maier2014; Dael et al., Reference Dael, Perseguers, Marchand, Antonietti and Mohr2016; Sutton and Altarriba, Reference Sutton and Altarriba2016). Therefore, the way we perceive the connection between colour and emotion is dependent on context (i.e., positive or negative) and also on our own personal experiences such as culture or personality, especially when colours are used for symbolism (Baker Reference Baker, McDonagh, Hekkert, van Erp and Gyi2004: 188; Elliot and Maier Reference Elliot and Maier2014). This shows that research on colour and emotion in psychology has faced significant methodological and conceptual critiques. Many studies rely on small or culturally specific samples, and affective responses to colour can vary widely depending on individual experience, context, and cultural background. In addition, popular accounts of colour–emotion associations often overstate the consistency or universality of these links, which are frequently more nuanced in empirical research. The studies discussed here are therefore not intended to establish universal psychological laws, but rather to provide illustrative evidence that patterns observed in literary portrayals of pathetic fallacy – where colour reflects or shapes emotional responses – are also reflected, to some extent, in empirical psychological research mapping emotions to surroundings. We thus draw on empirical research on specific colours to first examine whether the depiction of light and dark shades, as well as brown and grey in literature, is reflected in individuals’ personal experiences. We then compare these observations with our findings from the previous literary analysis.

Empirical studies consensually corroborate the conceptual metaphors good is light and bad is dark, as research shows that individuals tend to associate white/light tones with positive events or emotions, whereas black/dark tones are associated with negative events or emotions (Berlin and Kay, Reference Berlin and Kay1969; Edwards, Reference Edwards2004; Biggam and Kay, Reference Biggam and Kay2006; Biggam et al., Reference Biggam, Hough, Kay and Simmons2011; Sandford, Reference 56Sandford, Biggam, Hough, Kay and Simmons2011). Additionally, Edwards (Reference Edwards2004: 183–184) explains that brown is often seen as a dreary colour, despite its omnipresence in nature. It can symbolise misery or gloominess, for instance, ‘to be in a brown study’ means to be in deep thoughts. A study conducted by Prado-León et al. (Reference Prado-León, Avilla-Chaurand, Rosales-Cinco, Biggam and Kay2006) observes how Mexican participants emotionally perceive colours. Results reveal that grey is associated with emotions of sadness and fatigue, whereas brown is linked to dirtiness. Prado-León et al. (Reference Prado-León, Avilla-Chaurand, Rosales-Cinco, Biggam and Kay2006) compare their results to a study led by Mahnke (Reference Mahnke1996) that also looked at emotional reactions to colours but on Western cultured individuals. Prado-León et al. (Reference Prado-León, Avilla-Chaurand, Rosales-Cinco, Biggam and Kay2006: 210, our emphasis) make the following comparison:

Mahnke found that only black and grey were associated with mourning/sorrow, but, in our study, brown was also associated with (6.2%) sadness, even more so than black (5.1%). It is interesting that Mahnke reports that the same test was conducted in Europe in 1993 (Germany, Austria and Switzerland), and, in that study, brown and violet appeared to be associated with sorrow/mourning.

In The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, the colour brown is associated with discomfort of other characters in the presence of Jekyll and Hyde’s split personalities. However, the scene analysed provides a description of London after the Carew murder and the creation of the potion have taken place, allowing Hyde to take over Jekyll, freeing his inhibitions. In both scenes, the idea of ‘dirtiness’ can be found: London is described with the colour brown (‘muddy’) as it reflects the atmosphere of the city after the sin of murder was committed, thus suggesting the dirtiness of Hyde’s soul now that he has committed the ultimate sin. Moreover, the colours of the potion when mixed create the colour brown, potentially suggesting that it will dirty Jekyll and Hyde’s character by leading them to sins such as the Carew murder. Furthermore, both instances eventually lead to the idea of death, thus reflecting the results obtained by Prado-León et al. (Reference Prado-León, Avilla-Chaurand, Rosales-Cinco, Biggam and Kay2006) and Mahnke (Reference Mahnke1996), suggesting brown represents sadness or mourning.

Edwards (Reference Edwards2004: 187–188) describes grey as ‘the color of gloom and depression’ and uses the song Body and Soul (1930) lyrics as an example: ‘a future that’s stormy, a winter that’s gray and cold’. Grey also represents emotions of uncertainty or uneasiness. For instance, the phrase ‘grey area’ suggests an undetermined area or our uneasiness to label said area. In another study, Kumarasamy et al. (Reference Kumarasamy, Devi Apayee and Subramaniam2014) analyse individuals’ positive and negative reactions to specific colours. Although they did not observe any positive or negative trend for the colour brown (Kumarasamy et al., Reference Kumarasamy, Devi Apayee and Subramaniam2014: 9), the colour grey was seen mostly negatively, and they offer the following interpretation:

Gray evoked the highest number of negative responses compared to black and was seen as the most negative because it is associated with rainy days and elicited sad or bored emotional responses. The emotions included sadness, depression, boredom, confusion, tiredness, loneliness, anger and fear. Reasons given for the negative emotional responses to gray shows that the colour gray tends to refer to bad weather, rainy, cloudy or foggy days and bring out the feelings of sadness, depression and boredom.

These observations are salient in our analysis of PF in The Woman in Black and Dracula. In The Woman in Black the narrator, Arthur, feels negative emotions such as uneasiness due to the supernatural events of the previous night, but he also feels sadness for yet again awakening at Eel Marsh House. These negative emotions are portrayed by the greyness of his surroundings, notably the bad weather (‘thick clouds’, ‘drizzle’). In Dracula, the greyness of the surroundings is conveyed by the fog, but also the mix of the black of the trees in the night and the white of the snow, mirroring the narrator’s uneasiness due to not knowing where he is going and his fear of the others on the same journey. These two literary examples reflect the findings observed in the empirical study conducted by Kumarasamy et al. (Reference Kumarasamy, Devi Apayee and Subramaniam2014).

Overall, the literary analyses provided mirror the findings of the empirical psychological studies looking at correlations between emotions and colours. This means that the more novel cross-domain mappings of PF observed in the texts analysed in this research could in fact be more commonplace than originally thought, such as discomfort is brown and grey is uneasiness. It also shows that the notion of ‘surroundings’ is a broad concept and can include anything from objects in a room (i.e., Jekyll and Hyde’s potion) to natural elements in a scene (i.e., Eel Marsh in The Woman in Black), as argued by Pager-McClymont (Reference Pager-McClymont, Pöhls and Utudji2021b: 238). This section contributes to Pager-McClymont’s view of surroundings in PF’s mappings, as colours are an inherent part of our surroundings; thus, they can reflect emotions or even trigger them in certain instances (see Grandjean et al., Reference Grandjean1973: 174; Persinger, Reference Persinger1975; Valdez and Mehrabian, Reference Valdez and Mehrabian1994: 394; Yildirim et al. Reference Yildirim, Akalin-Baskaya and Hidayetoglu2007: 3233; Saxbe and Repetti, Reference Saxbe and Repetti2010: 71–72). In the case of PF and its mapping emotions are colour tones, colours not only explicitly convey emotions and build the ambience of a scene (i.e., Lennox’s anguish and suspense in Macbeth), but they are also character building (i.e., brown reflects Jekyll and Hyde’s mixed personality) and they can foreshadow upcoming events such as the role Thornhill plays in Jane’s story.

3.4 Conclusion

This section has demonstrated that colour is not only a descriptive feature of surroundings but also a central element in the metaphorical projection of emotions through PF. By examining examples across canonical texts, we observed how well-established mappings such as good is light and bad is dark continue to structure literary representations of affect, while more novel mappings like discomfort is brown and uneasiness is grey broaden our understanding of how emotions can be encoded. These mappings do more than mirror character states: they contribute to ambience, narrative tension, foreshadowing, and characterisation. As such, PF emerges as a particularly rich site for investigating how metaphor functions at the intersection of language, cognition, and aesthetics.

When considered alongside findings from psychology, these analyses underline the interdisciplinary value of studying colour–emotion correspondences. While research shows that such associations are not universal and vary across cultures and contexts, the parallels between literary portrayals and empirical data suggest that colour operates as a salient conceptual domain for encoding affective experience. By foregrounding colours as a key aspect of surroundings within PF, this section extends Pager-McClymont’s model and highlights how colour metaphors provide insight into both literary technique and human psychology. Ultimately, this convergence invites further exploration into how readers process the interaction between environment and emotion, and how literature both reflects and shapes our perceptual and emotional lives.

4 Absence of Colour Concepts: Colourlessness in Literary Prose

This section builds on the analyses of Sections 2 and 3 by turning to the absence of colour, using a mixed-methods approach that incorporates corpus analysis to examine how colourlessness functions in literary prose and how it becomes a powerful interpretative resource. Indeed, in this section we present a broad survey of the lexeme colourless in nineteenth- and twentieth-century prose. This research is corpus-based, whilst cognitive linguistic tools such as metaphor and schemas are used to interpret the findings and showcase their impact on readerly experience. The use of a corpus allows us to identify characteristics and patterns of language to provide a replicable and reliable literary critical position on how the term is employed in a sample of prose representative of an entire literary movement: Modernism. Throughout the section, we use the following definitions: the literal meaning of the term colourless is ‘having no colour; transparent, clear’ (‘colourless’, 2024). The OED defines a colour as ‘any of the constituents into which light can be separated as in a spectrum or rainbow; any particular mixture of these constituents; a particular hue or tint’ (‘colour’, 2024).

4.1 Research Corpora and Methodology

The methodology was selected to establish a relationship between the notions put forth by the concept of colourlessness and the literary employment of the term. Corpus-based research can aid in the systematic identification of language patterns and linguistic deviations, consolidating intuited impressions. Insights can be delivered into recurring features of literary style by providing empirical evidence that identifies and confirms salient conclusions (Simpson, Reference Simpson2014). As summarised by Mahlberg and McIntyre:

A major benefit of using corpus techniques to aid stylistic analysis is that this practice enables us to address what has long been an issue with the analysis of prose fiction. This is the problem of length and the fact that most prose texts are simply too long for the stylisticians to deal with.

The application of corpus stylistics research methodologies does not replace literary or textual analysis, but instead works in conjunction to identify and quantify linguistic features, enabling generalisations to be made about the language within a text. The data analysis approaches chosen to examine the research findings are firmly grounded in established linguistic and stylistic frameworks, allowing for an in-depth understanding of the lexeme colourless in Modernist prose and cognitive linguistic tools are employed to interpret patterns.

4.1.1 Corpora Selection

Focusing on a single word requires a large number of texts to allow salient conclusions to be drawn, resulting in the need for digital editions due to the vast amount of text being searched and analysed. Additionally, complete passages were needed to develop a clear understanding of the context, meaning, and usage of colourless. These criteria negated the use of popular corpora such as the British National Corpus and the Corpus of Contemporary American, as the co-text required for a thorough analysis is often not readily available. Initially, three corpora containing nineteenth- and twentieth- century prose texts were selected for study: CLiC 19th Century Reference (Mahlberg et al., Reference Mahlberg, Stockwell, Wiegand and Lentin2020);Footnote 2 CLiC Dicken’s Novels (Mahlberg et al., Reference Mahlberg, Stockwell, Wiegand and Lentin2020); and HUM19UK.Footnote 3

The CLiC corpora website allows for simple searches on one or more terms for each of the corpora available within the online application. The HUM19UK corpus is comprised of 100 complete British novels published between the years 1800 and 1899. There is no search facility available for HUM19UK, so the texts were downloaded and examined using the search capabilities of Windows Explorer. A total of forty-six texts in all three corpora contained the lexeme colourless.

The lexeme colourless occurs fifteen times in the CLiC Dickens corpus and there are twenty-six instances in the CLiC 19th Century corpus. Additionally, the word colorless with the American spelling is found nine times in the CLiC 19th Century corpus, resulting in thirty-five uses of the lexeme in the two corpora. There are fifty-eight occurrences in total of colourless in the HUM19 corpus. The text with the highest frequency is Shirley (1849) by Charlotte Brontë, containing the lexeme colourless seven times. Two texts in the HUM19 corpus both have six occurrences of colorless: Under Two Flags (1867) by Louise de la Ramee and Robert Elsmere (1888) by Mary Augusta Ward. As there were only fifty-eight passages and three texts written by three authors, we concluded that the HUM19 corpus would also not provide a diverse representation of the notions put forth by colourless in prose. As these three corpora are comprised of nineteenth-century prose, we made the decision to create a bespoke corpus of Modernist prose (see Section 4.1.2), speculating there would be a large number of texts available in digital format, offering significantly more examples of colourless to examine and research. Our findings show that 144 texts use the lexeme colourless in the bespoke corpus – at least four times more than the corpora discussed earlier. The following sub-section explains how the corpus was created and the selection criteria used to identify those texts warranting further analysis.

4.1.2 The Modernist Literature Project

Modernism as a literary movement is characterised by the rise of industrialisation and development of the modern world in Europe and the United States between the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century and was particularly shaped by World War I. In both poetry and prose fiction, modernism is defined by an intentional departure from conventional literary methods (Childs, Reference Childs2008; Parsons, Reference Parsons2014).

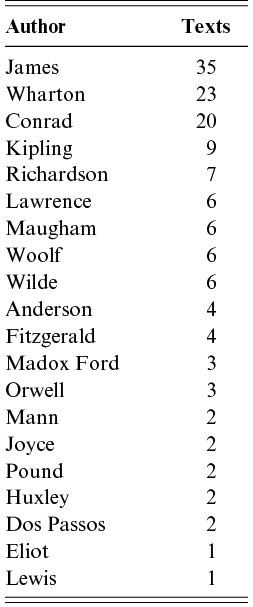

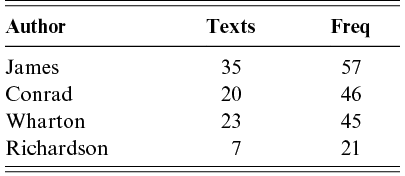

We use the Modernist Literature ProjectFootnote 4 (henceforth MLP; McClure and Pager-McClymont, Reference McClure and Pager-McClymont2022) as the starting point for this study. Presently, the MLP contains over 20 million words, 328 texts, and 31 authors. The corpus offers Modernist prose fiction, shorter prose, and poetry as well as sub-corpora for specific authors and themes. Each text has been processed by WmatrixFootnote 5 (Rayson, Reference Rayson2009) to create parts-of-speech and semantic domain tagsets that are also available on the website. The MLP includes only digital versions of texts that exist in the public domain to avoid copyright issues as the corpus is freely accessible. Therefore, some works from canonical Modernist authors such as Joyce and Hemmingway are not included.

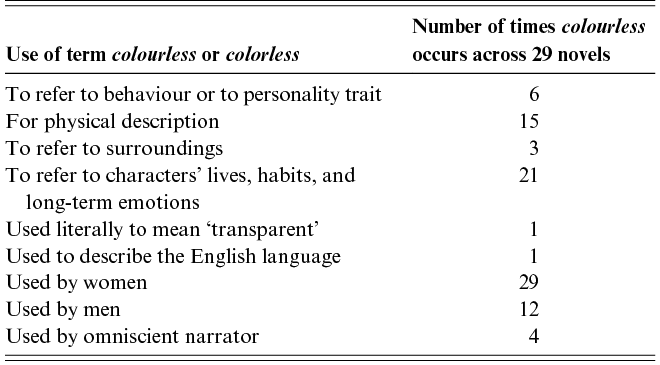

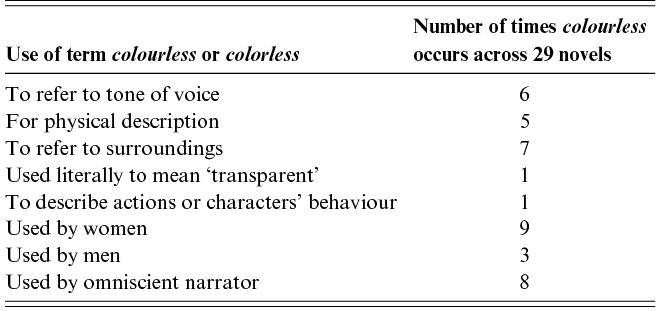

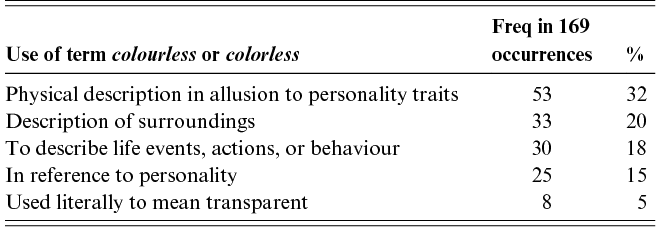

4.1.3 Methodology