Introduction

More than 20 years ago, Klingemann and Fuchs (Reference Klingemann and Fuchs1995) noted a universal rise in non‐conventional forms of participation, which they considered the most important transformation Western democracies had undergone since the Second World War. They argued that the rise of protest has changed the informal rules of interaction between citizens and their representatives (also see Dalton Reference Dalton2008). Citizens learned to rely on protest to scrutinise their representatives and keep political parties in check. Since then, protest developed from a marginal form of participation to one of the main arenas of mobilisation. The spread of protest became the subject of a voluminous literature on the ‘normalisation of protest’. Outlining this development, Meyer and Tarrow (Reference Meyer and Tarrow1998, p. 4) name three important aspects: protest has evolved from a sporadic to a perpetual element of politics, it is used by a more diverse constituency for wider claims and social movements themselves have become professionalised and more conventional.

Our study aims to revisit the spread of protest from a comparative, European perspective. We focus on the first two aspects of ‘normalisation’, namely the level and, in our case, the ideological composition of protest as part of the widening of the constituency of protest. By the latter, we mean whether the characteristic predominance of the left in protest found in previous literature (Hutter & Kriesi Reference Hutter, Kriesi, van Stekelenburg Roggeband and Klandermans2013; Soule & Earl Reference Soule and Earl2005, p. 347) holds over time and across countries with diverse historical backgrounds. We see both the extent of protest and the ideological component as important parts of the normalisation argument.

We follow recent studies of electoral and protest politics (Hutter & Kriesi Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Lorenzini, Wüest and Häusermann2020) that examine differences across the European regions. Regarding party systems, this literature has confirmed differences in patterns of competition and the degree of institutionalisation across Northwestern, Southern and Eastern Europe; leading to different forms of linkages between citizens and their representatives (Wineroither & Seeber Reference Wineroither and Seeber2018). For protest, the take‐away message is more ambiguous. Though some studies point out the particularities of protest in Southern and Eastern Europe (e.g., Ekiert & Kubik Reference Ekiert, Kubik, Fagan and Kopecký2018), Europe‐wide comparisons tend to universalise the Northwestern European protest experience.

In this regard, the link between ideology and protest is particularly interesting, since arguments for the development of ‘social movement societies’ as well as for a predominance of the left have both been derived from the impact of the New Left (e.g., Hutter & Borbáth Reference Hutter and Borbáth2019; Meyer & Tarrow Reference Meyer and Tarrow1998; Van Aelst & Walgrave Reference Van Aelst and Walgrave2001). This experience, however, is specific to Northwestern Europe. Other countries tend to be omitted from comparative research, not least since population surveys are typically less widely available and cover a shorter time horizon. Studies that include post‐communist countries (e.g., Torcal et al. Reference Torcal, Rodon and Hierro2016) often solely focus on differences in the level of protest rather than on the different character of protest participation (for an exception, see Bernhagen & Marsh Reference Bernhagen and Marsh2007; Kostelka & Rovny Reference Kostelka and Rovny2019). We think that our understanding of protest in Europe as a whole – and particularly in Southern and Eastern European countries – benefits theoretically and empirically from a closer look at cross‐regional differences in protest patterns.

We argue that the relation between left–right orientations and protest is highly context dependent and shaped by historical and present‐day regime access. Groups whose ideological views are not represented in current politics are more likely to protest. In addition, when the ideological views of groups have been historically excluded from power, this may have long‐lasting effects on the composition of protest. We rely on this mechanism to explain cross‐regional differences in the relationship between citizens’ ideological orientations and their protest participation.

To present our argument, we begin by outlining the previous literature on the role of left–right orientations and normalisation. We proceed by first examining historical legacies and then the current political constellation as two facets of regime access. We then introduce our data and methodological approach, after which we present our results. We find little participation by the left in protest in Eastern Europe, and widespread protest especially by left‐wing citizens in Southern Europe. On exploring this further, we encounter a different influence of ideology as a function of exposure to the former regime, of partisanship and of opposition to the current government.

The Northwestern European experience: Predominance of the left or normalisation of protest?

Most of the evidence we have regarding the relation of left–right placement and protest stems from the aforementioned strands of literature: the normalisation of protest and the argument about the continued predominance of the left. The normalisation of protest literature documents that over the past decades, non‐violent demonstrations have become part of the conventional repertoire of politics in Northwestern European societies. This is due to the post‐1968 trend of increasing protest in which new social movements played a crucial role. The rise of new social movements had two consequences. First, it widened the issue repertoire of the protest arena. With mobilising for the environment, peace, women and LGBT+ rights, protests over traditional ‘bread and butter’ issues lost their dominance (Hutter & Borbáth Reference Hutter and Borbáth2019). Second, partly as a result of mobilisation on these issues, new social movements mobilised groups previously unlikely to protest (Van Aelst & Walgrave Reference Van Aelst and Walgrave2001, p. 462). In particular, the success of New Left movements potentially attracted counter‐mobilisation by the right on issues such as immigration and European integration (Gessler & Schulte‐Cloos Reference Gessler, Schulte‐Cloos, Kriesi, Lorenzini, Wüest and Häusermann2020). Hence, protest became available to (almost) all citizens to express their grievances.

Diverging from this, studies of protest behaviour have argued that the left continues to dominate the protest arena. Though ideology has a small impact on participation in conventional politics, protest seems to be the one field in which the left is more strongly represented (Van Der Meer et al. Reference Van Der Meer, van Deth and Scheepers2009). One reason for this is a difference in the arenas preferred by the political left and right. Hutter and Kriesi (Reference Hutter, Kriesi, van Stekelenburg Roggeband and Klandermans2013, p. 282) argue that movements of the right prioritise the electoral channel, leading to a dominance of the left in protest. Thus, participation by the two camps follows a different logic with the right opting for orderly forms of mobilisation. Although parties may play an intermediary role, most authors, including Hutter and Kriesi (Reference Hutter, Kriesi, van Stekelenburg Roggeband and Klandermans2013), explain this difference with citizens’ attitudes and issue positions. According to this view, citizens on the right prefer conventional forms of participation, while citizens on the left endorse social change by all available means.

These theories are not necessarily contradictory. The entrenchment of patterns of participation in personal values means that ideological differences may persist but slowly shrink over time. Therefore, a pan‐European assessment of normalisation should move from a static view of citizens’ protest proximity towards evaluating the process of convergence over time.

Northwestern Europe as a model?

While initial outlines of the social movement society argument explicitly dealt with post‐transition societies (e.g., Kubik Reference Kubik, Meyer and Tarrow1998), attention to circumstances that are different to those in Northwestern Europe has faded. Instead, in assessing the development of social movement societies, most comparisons take Northwestern Europe as a standard and focus on participation levels, rather than differences between ideological groups. Southern Europe is usually included in the range of potential social movement societies (despite the absence of the New Left protest wave there in the 1970s) since the level of protest in these countries matches or even exceeds Northwestern Europe. In contrast, as Gagyi (Reference Gagyi2015) has argued, differences between Northwestern and Eastern European social movements are typically understood in terms of inadequacy or backwardness. In comparative studies, Eastern Europe is frequently compared to ‘less developed’ countries that exhibit lower protest participation (Rucht Reference Rucht, Dalton and Klingemann2007, p. 713). For these countries, the conventionality of protest is assumed to increase with modernisation and progressive cultural change.

Beyond the level of protest, we know little about its ideological composition outside of Northwestern Europe. The social movement society argument implies that over time, an equal distribution emerges as protest becomes increasingly common. In contrast, Dalton and colleagues (Reference Dalton, Van Sickle and Weldon2010) have argued that the effect of left–right placement and the relation between post‐materialist values and protest strongly depend on the openness of the political context and the level of economic development. They suggest that it is primarily in politically and economically well‐off societies that ideology comes to shape individuals’ propensity to protest. In politically less open countries, citizens have fewer opportunities to mobilise, leading to a weaker effect of ideological polarisation on protest.Footnote 1 However, Dalton and colleagues rely on differences that are far larger than the differences within Europe to show the influence of economic and political development. Furthermore, in line with the social movement society approach, they suggest the spread of protest is merely a question of progress in institutional development. We contest the implicit assumption of a linear developmental process of modernisation. Instead, we suspect the relation between ideology and protest, as well as the level of protest, is affected by historical and present‐day regime access. In what follows, we develop our argument about legacies and differences in regime access that influence patterns of protest.

Historical legacies and protest in Southern and Eastern Europe

For both arguments – the predominance of the left and the normalisation of protest – historical experiences were central. In Northwestern Europe, the nexus between protest movements and the left is linked to the cultural revolution and to the emergence of the new social movements of the 1970s (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Koopmans, Duyvendak and Giugni1995). Similarly, the social movement society argument relies on the spread of the New Left's ideas across society. In this sense, the 1970s and 1980s still form the decisive protest experience for Northwestern European countries (Hutter & Borbáth Reference Hutter and Borbáth2019).

However, the New Left has been absent or at least more fragmented in other regions of Europe. In Southern Europe, the left has been split between a dominant communist and a moderate social‐democratic wing. The dominance of the communist ideology among the left opposition contributed to reservations towards the critical movements of 1968 and the following decades. In addition, three Southern European countries – Greece, Portugal and Spain – were ruled by right‐wing authoritarian regimes, which persecuted left‐wing ideas, forcing left movements to organise outside institutional politics. Italy is a partial exception, given that elections were regularly held and that since the ‘apertura a sinistra’ in the early 1960s, the non‐communist left has been increasingly integrated into the government. Nevertheless, similar to the other three countries, the electorally strong Italian Communist Party was systematically excluded from government until the collapse of the First Republic in 1992. In the absence of large new social movements, the left in these countries remained radical or social‐democratic without a significant turn towards new cultural issues (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1988). For a long time, the protest arena and unconventional politics were the only opportunity for the left to express itself politically. Hence, while protest became a normal means of doing politics, it remained a domain of the left with little normalisation.

As in Southern Europe, the political development of Eastern Europe has been shaped by pre‐democratic legacies. The former Eastern European regimes were justified with communist ideology. During their four‐decades‐long rule, the communist regimes appropriated the symbols of left‐wing politics and kept these countries isolated from the influence of New Left ideas. Liberal, Christian‐democratic and others who were ideologically opposed to the regime had to organise below the state's radar. Consequently, unlike in Southern Europe, the role of historical opposition falls to right‐wing forces in Eastern Europe. In this regard, the 1989 regime change did not lead to the breakthrough of New Left forces as previous governing parties often kept their dominant position among the left in electoral politics. Instead, the post‐transition phase saw the transformation of the left in a different way: a left‐right consensus emerged on questions regarding privatisation, property rights and free markets as they came to be conceived as a progressive break with the past. Mobilisation in the name of social justice became associated with the communist past and post‐communist left parties were reluctant to challenge the neoliberal character of the socio‐economic transition (e.g., Tavits & Letki Reference Tavits and Letki2009). According to comparative analyses of protest in Poland (Ekiert & Kubik Reference Ekiert and Kubik2001, p. 184), economic protests focussed on pragmatic ‘everyday concerns’, and did not feed into a comprehensive ideological challenge of the existing order.

Given the limited influence of the New Left in these two regions, we expect historical regime access to play a strong role, leading to opposite mobilisation patterns in Southern and Eastern Europe. Therefore, contrary to the normalisation perspective that expects equal or converging levels of protest by citizens with different ideological views, we expect that:

H1: In Northwestern and Southern Europe, respondents who identify as left are more likely to participate in protest than those who identify as right. In Eastern Europe, the opposite applies.

Historical legacies and individual‐level behaviour

Inquiring into the reasons behind these aggregate patterns, we may ask how legacies of regime access affect current day protest patterns on the individual level. Such an analysis may provide further evidence regarding the importance of historical legacies relative to other factors like economic and political development. In this regard, Pop‐Eleches and Tucker (Reference Pop‐Eleches and Tucker2017) distinguish two ways to conceptualise the effect of the long‐term consequences of communism on individual‐level attitudes and behaviours. Citizens may behave differently because they ‘live in a post‐communist country’ or because they ‘lived through communism’. They argue that rather than the mere fact of living in a post‐communist country, it is having lived through communism (including its education system) that leaves a lasting impact on citizens. The post‐communist legacy is then not primarily the current economic or political situation of the country, but the past socializing experience individuals living in this country have been exposed to.

Indeed, the literature has shown that the grievances of citizens who were socialised under communism may be different than those of subsequent generations. Notably, having lived under communism brings a comparative perspective to citizens’ evaluations of regime performance (Gessler & Borbáth Reference Gessler and Borbáth2019). Our emphasis on individual‐level determinants is in line with a recent paper, which finds that absolute differences in cultural orientations between regions do not disappear with the economic development of post‐communist countries due to the persistence of cohort‐level differences (Beugelsdijk & Welzel Reference Beugelsdijk and Welzel2018). These differences may also impact participation in protest, which in many countries was the dominant form of public participation during the transition period (Ekiert & Kubik Reference Ekiert and Kubik2001).

Revisiting the relationship between left–right positioning and protest on the basis of this distinction, we follow Pop‐Eleches and Tucker and expect that individual exposure to communism results in left‐wing citizens being less likely to participate in protest. This is based on the mechanisms we have outlined in the previous section: the legacies of communism, such as the de‐legitimisation of left‐wing protest, manifest themselves in the experiences of individuals. While Pop‐Eleches and Tucker exclusively focus on the effect of communist legacies on individual‐level behaviour, we believe the conceptual framework is similarly useful in understanding the legacies of past regimes in Southern Europe. Della Porta et al. (Reference Della Porta, Andretta, Fernandes, Romanos and Vogiatzoglou2018) examine how the legacies of the former regimes and the transition are instrumentalised by Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and Greek protest movements to mobilise for their goals. Although they do not focus on individual‐level differences, their findings suggest that this strategy might primarily rally those who have direct experiences with right‐wing authoritarianism and were excluded from power due to their left‐wing ideas. Similar to communism, the legacy of right‐wing oppression might taint protest participation for conservative goals in the minds of citizens. As Della Porta and colleagues show, historical legacies shape the protest scene in fundamental ways and impact the interaction of social movements and the state. Therefore, we expect that in the two regions, a similar mechanism leads to a different conditional effect of exposure:

H2A: Past exposure to communism deters citizens on the left from protest participation.

H2B: Past exposure to right‐wing authoritarianism deters citizens on the right from protest participation.

Electoral politics: Partisanship and the moderating effect of government ideology

Notwithstanding the importance of direct exposure to the former regimes, its role in explaining cross‐regional differences might prove transitory as it wears off with generational replacement. Instead of conceiving legacies as cultural, we have highlighted regime access as the mechanism behind these differences. Even though the transition to democracy changed the operation of this mechanism, we believe it continues to influence protest behaviour in the post‐transition period, independent of generational replacement. With reasonably free and fair elections, representation by political parties and government composition become the most important determinants of access. Therefore, we introduce a second set of factors explaining regional differences in the ideological composition of protest: the interaction between the protest arena and the electoral arena. We focus on two moderating factors in particular: partisanship and the ideology of the government.

At the individual level, proximity to a party provides citizens with access to a regime by providing them an entry‐point. Numerous studies have shown that participation in the electoral and the protest arenas are complementary (e.g., Teorell et al. Reference Teorell, Torcal, Montero, Montero van Deth and Westholm2007, p. 354). First, voters who identify with parties are among the most efficacious citizens. They are interested in politics, are part of politically mobilised networks, follow the news and know the most about political issues. Second, political parties directly mobilise supporters in the protest arena. Borbáth and Hutter (Reference Borbáth, Hutter, Kriesi, Lorenzini, Wüest and Häusermann2020) have shown that diverse parties regularly organise or sponsor protests. Consequently, party identification is among the best predictors of protest (Van Aelst & Walgrave Reference Van Aelst and Walgrave2001).

However, the literature documents that important East–West differences in the role of parties in mobilising protest exist beyond the regime legacies we have outlined. When protest is supported by parties in Northwestern and Southern Europe, it is mostly left‐wing parties (and occasionally the extreme right) that mobilise. Conservative or Christian–Democratic parties have been reluctant to organise in the streets (Borbáth & Hutter Reference Borbáth, Hutter, Kriesi, Lorenzini, Wüest and Häusermann2020). Because of this asymmetry, party identification should increase the differences between left and right citizens. In Eastern Europe, in contrast, political parties have been identified as the main mobilisers for all kinds of participation, including protest (Teorell et al. Reference Teorell, Torcal, Montero, Montero van Deth and Westholm2007, p. 351). Studies of single countries and comparative evidence suggest that right‐wing parties in particular have been the most active in sponsoring protest in Eastern Europe (e.g., Greskovits Reference Greskovits2017). Coupled with the weakness of Green and New Left parties and the reluctance of post‐communist left parties to mobilise protest, we argue this contributes to a different pattern of participation where citizens on the right are more likely to protest. Therefore, we expect that partisan identification enhances the effect of ideology, rendering those groups that we believe to be active in protesting even more likely to protest:

H3A: In Northwestern and Southern Europe, party identification strengthens the effect of left‐wing ideology on respondents’ propensity to protest.

H3B: In Eastern Europe, party identification strengthens the effect of right‐wing ideology on respondents’ propensity to protest.

Additionally, we expect that ideological congruence with the current government defines contemporary regime access and influences the composition of protest. Individuals who voted for parties that do not enter government, so‐called electoral ‘losers’, have higher incentives to protest compared to electoral ‘winners’ (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005, pp. 45–47). Instead of links to parties that do not enter government, Van Der Meer et al. (Reference Van Der Meer, van Deth and Scheepers2009) rely on ideological distance to operationalise the ‘winners’ versus ‘losers’ dichotomy and find that citizens who are ideologically most distant from the government in office are more likely to protest. Generally, electoral losers’ disappointment with the results and their lower likelihood of seeing their policy preferences implemented may make them more likely to protest.

Regarding regional differences, (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005; Anderson & Mendes Reference Anderson and Mendes2006) argue that losers are less likely to give their consent in new democracies. The difference between old and new democracies is driven by the comparatively higher electoral stakes in the latter. As Mair (Reference Mair1997) notes in an influential essay, both policy and institutional choices in younger democracies are highly consequential and frequently an object of contestation in electoral campaigns. Therefore, any election might have grave consequences for those who end up losing. Moreover, it takes time before the electorate in newer democracies becomes accustomed to losing. The results of Anderson and Mendes (Reference Anderson and Mendes2006, p. 105) indicate that after about 20 years, the difference between old and new democracies noticeably shrinks. The institutionalisation of the democratic system reduces the stakes of elections and contributes to passing this threshold. In this regard, the effect might distinguish Eastern Europe from Northwestern and Southern Europe, where regime change occurred several decades ago.

H4: Ideological distance to the government has a smaller effect on protest in Northwestern and Southern Europe compared to Eastern Europe.

However, the above, mostly demand side centred perspective does not take direct mobilisation by the government into account and presupposes a similar dynamic for governments of different colour. While protest is typically used by citizens as a tool against the government, the literature on government sponsored protest highlights that governments may strategically decide to mobilise protest to show their popular backing (e.g., Peace Marches in Hungary, see: Susánszky et al. Reference Susánszky, Kopper and Tóth2016). Government mobilisation might lead to a higher share of protest by electoral winners and leads us to refine the previous expectation on regional differences by introducing the ideology of governments and their varying willingness to mobilise. Following our discussion on the role of historical regime access, we argue that governments close to the previous regime are less likely to mobilise protest. Particularly, in Eastern Europe, where the regime change is more recent, mobilisation by left‐wing governments brings back the memory of state organised street parades with mandatory participation, a heritage which left‐wing governments are unlikely to claim. In contrast, right‐wing governments benefit from state‐sponsored historical commemorations. Celebrations of anti‐communist uprisings and national holidays that were typically not observed by the previous communist regimes provide ample opportunities for right‐wing citizens to participate in public political events. This allows the right to formulate an exclusive claim to represent the national identity by appealing to their historic opposition status and heritage of anti‐communist resistance. Hence, we consider the colour of the government as a further contextual factor behind regional differences:

H5: Under right‐wing Eastern European governments, low ideological distance leads to higher protest, whereas under left‐wing Eastern European governments, high ideological distance leads to higher protest.

Data and methods

We use all available eight waves of the European Social Survey (ESS), covering the period from 2002 to 2016. We include all countries which took part in at least four waves of the ESS. The survey is regularly used in the literature on protest and is collected biannually across European countries. We improve on the modelling strategy of previous studies that assume the independence of observations over time (e.g., Torcal et al. Reference Torcal, Rodon and Hierro2016) by accounting for both countries and waves (years). Following recent literature on cross‐classified models with cross‐national survey data collected over time (Fairbrother Reference Fairbrother2014), we recognise that the resulting country*year combinations are not independent and are additionally nested in countries. Hence, we rely on three‐level models, with respondents nested in country*year groups and in countries.Footnote 2

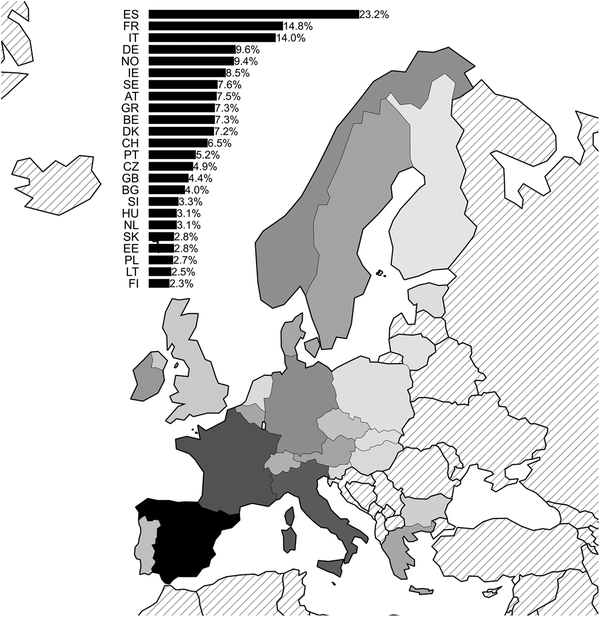

While some studies have considered protest within the context of other forms of political participation (Van Der Meer et al. Reference Van Der Meer, van Deth and Scheepers2009), we only use the survey question regarding demonstrations. Our expectations regarding normalisation only affect political protest (and not institutional participation). The dependent variable is participation in a lawful demonstration in the past 12 months. The respective question is included in every survey; it is part of a wider battery of questions on political participation with a response rate of over 99 per cent. Answers are heavily skewed towards respondents who have not participated in a demonstration during the last year. Figure 1 presents the share of protesters in each of the 25 countries we analyse. Across Europe, less than 7 per cent of respondents went to demonstrations. Only in Spain, France and Italy, did more than every tenth respondent participate in lawful protests. In 10 countries, seven of which are from Eastern Europe, the percentage of respondents who have participated in a demonstration is below 5 per cent. Hence, the regional average participation rate is 12.5 per cent in Southern Europe, 7.4 per cent in Northwestern Europe and 3.3 per cent in Eastern Europe.

Figure 1. Share of protesters across Europe.

Note: Darker shades reflect a higher average share of protesters in each country, across all ESS waves. The share is calculated based on the number of respondents who indicated that they have participated in a lawful demonstration in the previous 12 months in the respective country.

While we argue with structural differences between the three European regions, we recognise the possibility of country‐level variation in these differences. In fact, the interclass correlation shows that 13.3 per cent of the variance in protest behaviour is due to differences between country*years, and an additional 11.2 per cent is due to differences between countries. Following our theoretical framework, we assume that these differences may not only affect the level of protest, but also the link between personal ideology and protest. Therefore, we add a random slope for ideology to our three‐level models.

Independent variables

Our two key independent variables are left–right self‐placement and region. To avoid assuming a linear effect of ideology on protest, we use the 11‐point scale to group respondents into extreme left (0–1), left (2–4), centre (5), right (6–8) and extreme right (9–10).Footnote 3 We group respondents from Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom into Northwestern Europe;Footnote 4 respondents from Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal into Southern Europe; and respondents from Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Slovenia and Slovakia into Eastern Europe.

To assess the impact of exposure to previous regimes on the individual level, we follow Pop‐Eleches and Tucker (Reference Pop‐Eleches and Tucker2017) and introduce the number of years an individual lived under these regimes. In line with their operationalisation, we do not consider the first six years and only code the variable for respondents who were born in the respective country. We follow their modelling strategy and always control for age when we assess the effect of exposure. In line with Pop‐Eleches and Tucker, we interpret the measure as an indicator of socialisation under the previous regimes.Footnote 5 We only construct this measure for Eastern and Southern Europe. For the former, we count the period between 1945 and 1989 as communist years; for the latter, we code country‐specific periods for the Franco regime in Spain (1939–1975), the Estado Novo regime in Portugal (1933–1974) and the rule of the military junta in Greece (1967–1974).Footnote 6

We measure the strength of party identification with two survey items. First, respondents were asked whether they ‘feel closer to any particular political party than all other parties’. Those who answered affirmatively were asked to indicate on a four‐point scale how close they feel to this party. The combination of the two results is a five‐point scale ranging between ‘no party identification’, ‘not at all close’, ‘not close’, ‘quite close’ and ‘very close’.

To estimate the impact of distance to the government, we rely on the ParlGov dataset (Döring & Manow Reference Döring and Manow2019) and on the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, de Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks and Vachudova2015). Since the dependent variable refers to protest participation in the previous 12 months, we measure the ideological stance of the government with the ideological position of parties that were part of the government during the year prior to the ESS fieldwork. We calculate the average left–right position of government parties, weighted by their seat share. Since both the ESS and CHES rely on 11‐point scales to measure left‐right ideological positions, we are then able to calculate the absolute value of the difference between the respondents’ self‐placements and the ideological position of each government. We use this measure to test the role of ideological distance to the government.

Concerning control variables, we follow previous studies of ideology and protest to enhance comparability. To control for what Schussman and Soule (Reference Schussman and Soule2005) call ‘biographical availability’, we include age and unemployment. We include gender, following the finding that men typically protest more. Personal resources are measured with the respondents’ years of education, and the size of the municipality where the respondent lives, ranging from a big city to the countryside. To capture organisational mobilisation, we control for union membership next to party identification. At the country*year level, we follow Dalton et al. (Reference Dalton, Van Sickle and Weldon2010) and Welzel and Deutsch (Reference Welzel and Deutsch2012) by introducing controls for economic and political development alongside the ideology of the government. Economic development is measured by GDP adjusted for purchasing power parity in 2011 international dollars, political development is measured by the World Bank estimate of voice and accountability. The latter accounts for differences in the strength of civil society across countries and over time. If the alternative explanation that Pop‐Eleches and Tucker (Reference Pop‐Eleches and Tucker2017) call ‘living in a post‐communist country’ (as opposed to having lived under communism) explains regional differences, the region variable should have no additional effect after controlling for economic and political development.

We also conducted extensive robustness checks to assess if the differences in the effect of left–right ideology on protest we find are indeed due to historical and present‐day regime access. The models in the online appendix C assess to which extent the results are robust to systematic differences in the understanding of ideological labels between countries and respondents driven by variation in value orientation, issue positions, the embeddedness in social cleavages and the importance of political parties. The results confirm the conclusions of the more parsimonious specification presented in the main text.

Results

Normalisation and regional patterns of protest

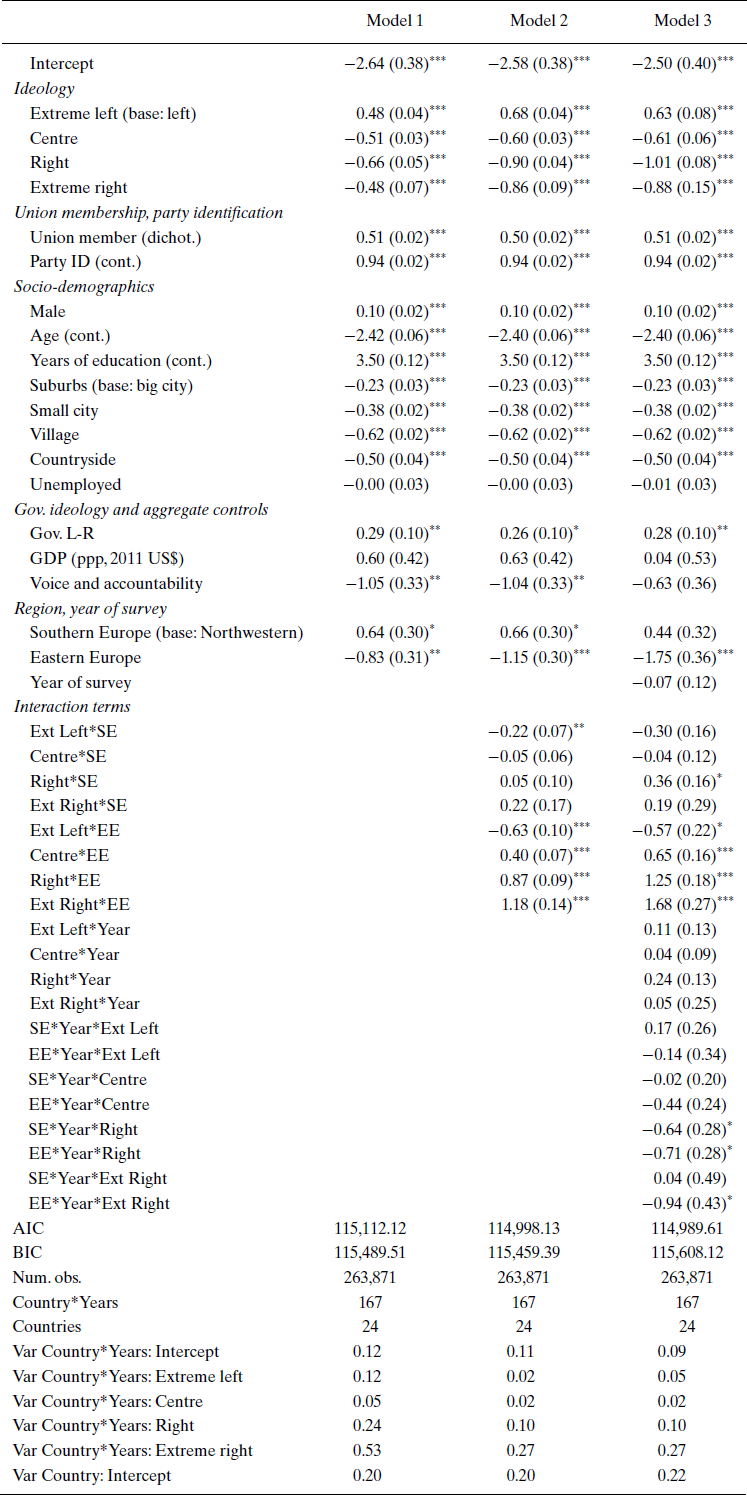

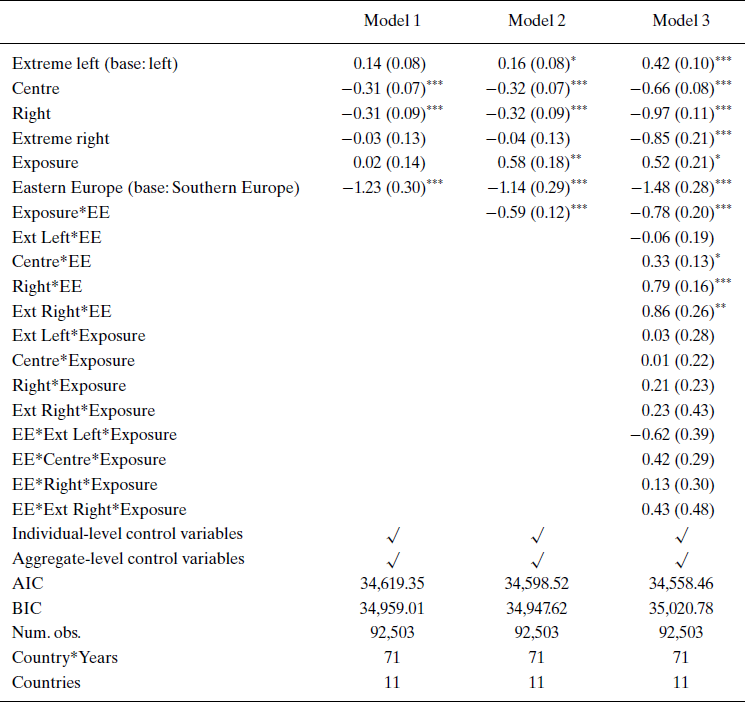

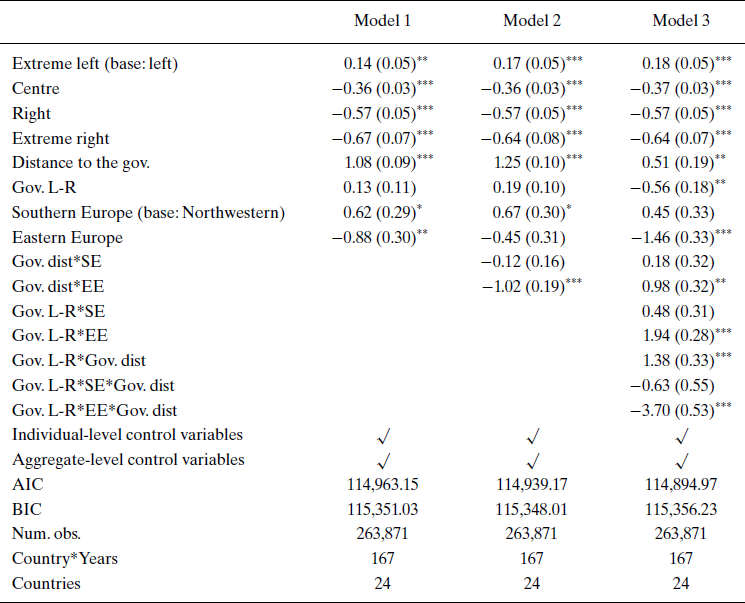

The three regression models presented in Table 1 speak to our baseline expectations. The first model includes our two key variables of interest – personal ideology and European regions – as well as the individual and aggregate control variables previously introduced. The second model includes a two‐way interaction between personal ideology and region to examine whether the effect of ideology on protest varies between the three regions. The third model includes a three‐way interaction between personal ideology, region and the year of the survey to consider normalisation as a process of over time convergence of the protest participation of different ideological groups.

Table 1 Normalisation of protest in the three European regions

***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

As the first model shows, we indeed witness the continued predominance of the political left, whether extremist or moderate. Hence, in line with previous studies (Torcal et al. Reference Torcal, Rodon and Hierro2016), we find little support for the movement society argument regarding the ideological component of normalisation. Additionally, the model predicts a slightly higher level of protest in Southern Europe and a lower level of protest in Eastern Europe, compared to Northwestern Europe. With a few exceptions, all control variables are statistically significant and point in the expected direction. Protest is positively associated with union membership, party identification, being male, being younger than average, education, size of the municipality, right‐wing governments and living under an institutional arrangement, which is less effective in ensuring ‘voice and accountability’. Controlling for these factors, unemployment and the GDP of the country do not play a role.

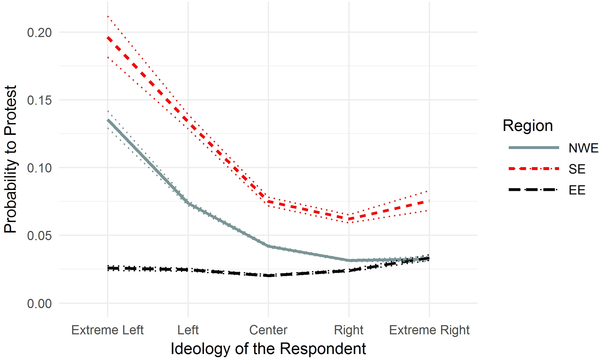

The second model shows that the three European regions differ not only in the level, but also in the type of protest they experience, even after controlling for the aggregate‐level factors previously introduced. The cross‐level interaction between the three regions and respondents’ personal ideologies shows that the effect of ideology is significantly different between Eastern and Northwestern Europe. Figure 2 presents the corresponding marginal effects.

Figure 2. Ideological composition of protest in the three European regions. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: The calculated marginal effects are based on model 2, Table 1.

As the figure shows, the difference between Northwestern and Southern Europe primarily concerns the level of protest rather than its ideological composition. In both regions, we observe the well‐established pattern of left‐dominated protest. Citizens who identify as right‐wing or extreme right‐wing are less likely to protest. As expected, Eastern Europe exhibits a different pattern: the level of protest is substantially lower than in the other regions. Moreover, within Eastern Europe, extreme right‐wing citizens seem somewhat more likely to protest than citizens on the left. While we present results on the regional level, the bivariate relationship between ideology and protest, as well as the random effect estimates of the model, confirms that the left is reluctant to protest in all Eastern European countries in our sample.Footnote 7

These results allow for interesting inter‐regional comparisons. The propensity of an extreme right‐wing individual from Eastern Europe to take part in a lawful demonstration is very similar to their ideological counterparts from Northwestern Europe. We can interpret the Eastern European pattern, either as a generally lower level of protest coupled with an extreme right that favours protest, or as a curious absence of left‐wing protest. Overall, the results confirm hypothesis H1 that suggests the comparative weakness of the left in Eastern Europe.

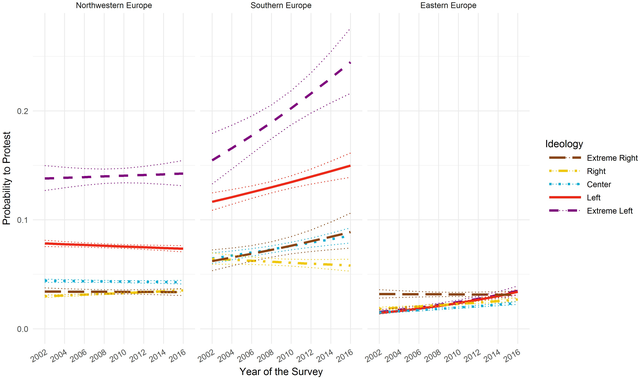

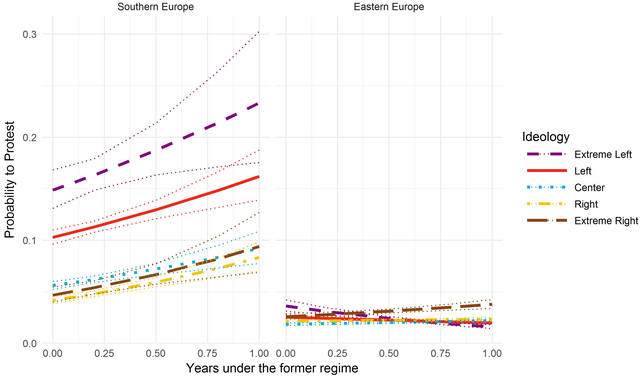

The third model shows that the three‐way interaction between region, personal ideology of the respondent and the year of the survey is not statistically significant. These results suggest that across the 14‐year period we examine here, there is no clear trend of convergence in protest by the different ideological groups in the three regions.Footnote 8 To ease its interpretation, Figure 3 presents the corresponding marginal effects.

Figure 3. Ideological composition of protest in the three regions over time. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: The calculated marginal effects are based on model 3, Table 1.

As the figure shows, the development of ideological patterns of protest over time follows a different dynamic in the three regions. In Northwestern Europe, the ideological composition of protest is remarkably stable. The extreme and moderate left dominate the protest arena. Extreme or moderate right‐wing individuals rarely protest. During the period we examine, the countries hardest hit by the economic crisis in Southern Europe witnessed the largest changes over time. Except for the moderate right, all ideological groups in Southern Europe increased their presence in the protest arena. However, greater mobilisation did not result in smaller differences between the ideological groups. The extreme left remained dominant, increasing its presence over time also relative to other ideological groups. Only the Eastern European pattern shows convergence of protest between the different ideological groups. Although at a very low level, moderate and extreme left‐wing groups draw level in their protest participation with the extreme right. By 2016, even those who belong to the moderate right or are in the centre approximate the level of protest of the extreme right.

Based on the above results, protest is normalised in none of the three European regions to the extent that we would observe an equal level of participation between the ideological groups or a clear convergence over time. In Northwestern and Southern Europe, the dominance of the left is entrenched, while in Eastern Europe, protest is mostly associated with the extreme right. Differences over time remain stable in Northwestern Europe, the left increases its relative presence in Southern Europe, and we observe convergence between the extreme right and other ideological groups in Eastern Europe. Nevertheless, protest in Eastern Europe remains a rare form of political participation, leading us to conclude that most citizens do not consider protest part of the ‘normal’ repertoire of political mobilisation.

At this point, we introduce additional variables to assess if individual exposure to the former regimes, differences in the effect of partisanship and government ideology explain the varying effect of ideology on protest in the three regions.

Individual‐level exposure to the previous regime

Given our primary explanation for the diverging patterns in the three regions rests on the impact of historical legacies, we estimate the impact of being exposed to the previous regime among citizens who live in these countries. As this introduces a comparison within Eastern and Southern Europe, it provides an additional test for the validity of our argument by examining whether differences are indeed due to living through these regimes, rather than living in a transition/post‐transition society. It also allows us to address whether the ideological composition of protest is generation specific and, consequently, whether the convergence within Eastern Europe we found in the previous section is due to generational replacement. We estimate the direct effect of exposure to the previous regime on protest (model 1), its differential effect in the two regions (model 2) and its moderating effect on the ideology of the respondent in the two regions (model 3). Table 2 shows the results.

Table 2 The effect of exposure to the former regime

Note: All estimates in Table 2 in the online appendix B. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

As model 1 shows, exposure to the previous regime has no direct effect on respondents’ decisions to participate in protest. However, the lack of a direct effect is due to the opposite direction of the effect in the two regions (model 2). While in Southern Europe, exposure to right‐wing authoritarianism mobilises protest, in Eastern Europe, exposure to the former communist regime does not. To clarify the Eastern European pattern and test our hypothesis, model 3 introduces the three‐way interaction between region, personal ideology and exposure. Figure 4 presents the marginal effects.

Figure 4. Marginal effect of exposure to the former regime on the ideological composition of protest in Southern and Eastern Europe. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: The calculated marginal effects are based on model 3, Table 2.

Whereas in Southern Europe the ideological differences are not significant – all groups are equally mobilised by greater exposure – in Eastern Europe, the reaction of respondents to exposure is moderated by their ideological views. Respondents on the left, especially the extreme left, are less likely to protest the more they lived under communism. In contrast, respondents who belong to other ideological groups, especially the extreme right, are more likely to protest the more they lived under communism. The three‐way interaction does not reach the conventional threshold of statistical significance due to the lack of differences in Southern Europe and the small effect of ideology in Eastern Europe. The latter makes it difficult to identify any effects specific to Eastern Europe, despite the relatively large sample. Nevertheless, the pairwise contrasts between the extreme/moderate left and the extreme/moderate right across different levels of exposure in Eastern Europe are all significant. To the extent that Eastern Europeans protest, they seem to behave according to our expectations. Therefore, we take these results to confirm our hypothesis H2A regarding Eastern Europe, but not H2B regarding Southern Europe.

Partisanship and the ideology of the government

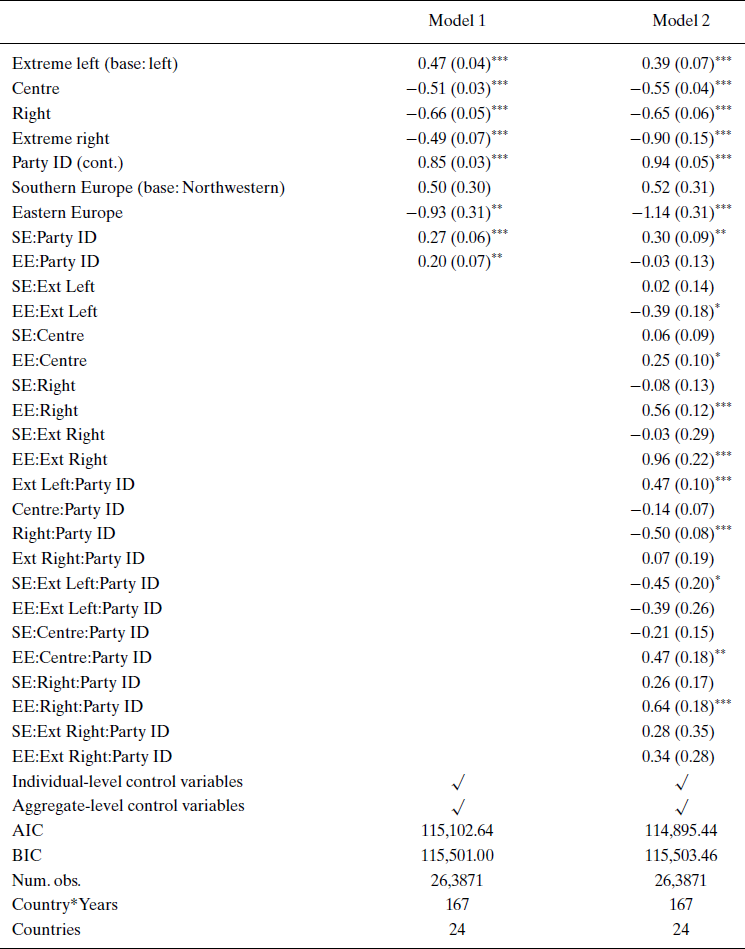

We now turn to the effects associated with contemporary regime access, namely the role of partisanship and the ideology of the government. The results previously presented in Table 1 confirm our expectation that stronger party identification contributes to a greater proximity to protest. However, our hypothesis referred to the moderating effect of these factors on the composition of protest in the three regions. To test the hypothesis, we estimate interaction effects between region, party identification and citizens’ ideological beliefs. Table 3 presents these results.

Table 3 The effect of partisanship on the ideological composition of protest

Note: All estimates in Table 3 in the online appendix B. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

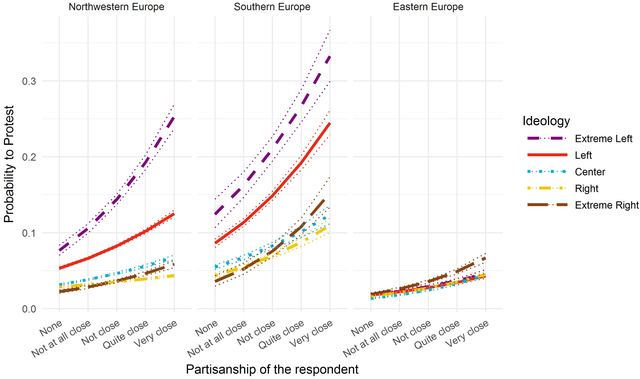

Model 1 confirms the expectation that party identification is associated with higher protest participation in all three regions. Model 2 shows that this effect varies according to the ideology of the respondent. The model shows that party identification influences the ideological composition of protest. Figure 5 presents the corresponding marginal effects.

Figure 5. Marginal effect of party identification on the ideological composition of protest in the three European regions. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: The calculated marginal effects are based on model 2, Table 3.

Party identification disproportionally increases radical and moderate left‐wing protest in Northwestern and Southern Europe compared to Eastern Europe. Particularly, protests in Northwestern Europe are to a greater extent dominated by extreme‐left party identifiers than protests in other parts of Europe. We take this to confirm our hypothesis H3A. In contrast, in Eastern Europe, protests are to a greater extent dominated by extreme‐right party identifiers than protests in the other two regions. We take this as evidence of hypothesis H3B.

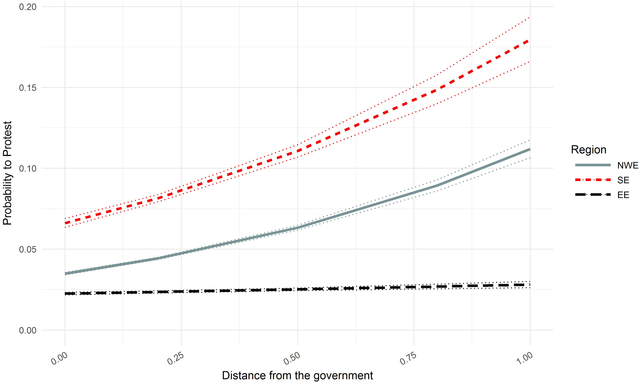

To test our hypotheses regarding the role of the government, we introduce our measure of ideological distance from the position of the government and we estimate its interaction with the two regions and subsequently with the left‐right position of the government conditional on the three regions. Table 4 presents the results. As model 1 shows, ideological distance to the government leads to a higher level of protest among all ideological groups. Once we introduce this measure, the left‐right position of the government has no statistically significant effect on the level of protest. Model 2 shows that the effect of the ideological distance to the government varies in the three regions. Figure 6 shows the results.

Table 4 The effect of distance to the government on the ideological composition of protest

Note: All estimates in Table 4 in the online appendix B. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

Figure 6. Marginal effect of distance to the government on protest in the three European regions. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: The calculated marginal effects are based on model 2, Table 4.

As the figure shows, ideological distance to the government leads to higher protest in Northwestern and Southern Europe, but has a very limited impact on protest in Eastern Europe, even considering the generally lower level of protest as a baseline. To assess the robustness of our results given the findings of Anderson and Mendes (Reference Anderson and Mendes2006), we estimate a three‐way interaction with the year of the survey to examine if the pattern is different in the first years of the ESS. The results included in the online appendix A, Table 2 and Figure 5 show that the effect of ideological distance to the government was never larger in Eastern Europe than in the other two regions throughout the timespan of the ESS. We take these results as clear evidence of the lack of a stronger loser effect in Eastern European protest and we reject H4.

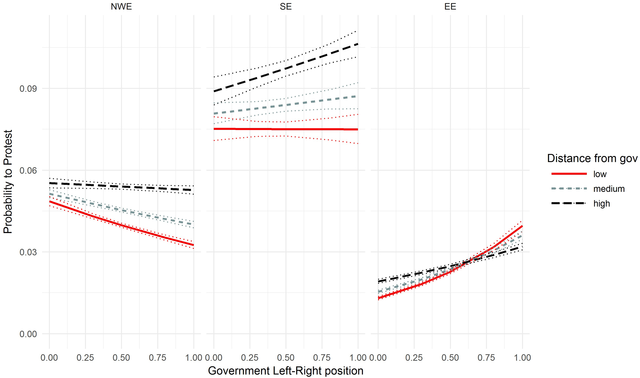

Having established that our data do not confirm the stronger loser effect in Eastern Europe, we turn to examine our hypothesis on the moderating role of government ideology on the ‘winner’–‘loser’ effect in this region. We estimate a three‐way interaction with region, distance to the government and ideology of the government. As model 3 shows, the interaction is statistically significant, confirming our expectation that the role of government ideology distinguishes Eastern Europe from the two other regions. In Northwestern Europe, we see a declining probability to protest by those close to the government under right‐wing governments, suggesting the right mostly protests when it is in opposition. In Southern Europe, we observe more protest under right‐wing governments due to an increase in protest by left‐wing citizens opposing the government. In Eastern European, right‐wing governments similarly experience a higher level of protest than left‐wing governments. However, as Figure 7 shows, the increase is partly driven by citizens on the right. Citizens who are ideologically close to governments on the right protest more than those who are ideologically distant. In contrast, under left‐wing governments, citizens who are ideologically distant protest more than those who are ideologically close. We take this as evidence of our hypotheses H5 on the different role of government ideology in mobilising protest in the three regions.

Figure 7. Marginal effect of distance to the government moderated by the ideology of the government on protest in the three European regions. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: The calculated marginal effects are based on model 3, Table 4.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have examined the extent of normalisation of protest across Europe. While taking part in demonstrations has become an important avenue for citizens to influence policies between elections, major differences remain in the extent to which they use this. In Northwestern Europe, our results confirm the established finding of relatively widespread protest dominated by the left. In this region, both the level and the composition of protest are stable with no clear trend over time. In Southern Europe, taking part in demonstrations became a more widespread phenomenon during our period of observation. Nevertheless, the more widespread protest mobilisation did not result in smaller ideological differences. The radical and moderate left continue to dominate protest in Southern Europe. Protest in Eastern Europe is markedly different than in the other two regions. Protest remains a rare form of political participation, predominantly used by the extreme right. While we found evidence of increasing mobilisation of other ideological groups, protest did not become more prevalent over time.

We have suggested that the mechanism of historical and current regime access explains regional differences. Our results confirm our expectation that in Eastern Europe, citizens who have historically been in opposition are more likely to protest. In Southern Europe, we found that exposure has no effect on the ideological composition of protest and increases the likelihood of protesting across the board. While we can only speculate, we believe that these differences may be driven by the way legacies are politicised in the two regions. While in Eastern Europe, issues like nostalgia, lustration and property restitution are contentious and salient debates, the relationship with the former regime remains a cleavage, but is less salient in party competition in Southern Europe.

Moving beyond legacies, we have shown that regime access continues to play a role in shaping patterns of protest. Party identifiers are more likely to protest and their presence contributes towards the differences between the ideological groups in all three regions. In line with the results of previous research (Borbáth & Hutter Reference Borbáth, Hutter, Kriesi, Lorenzini, Wüest and Häusermann2020), which found a higher share of left‐wing parties among protest organisers in Western Europe and right‐wing parties in Eastern Europe, we believe that direct mobilisation by parties in protest contributes to this effect. Moreover, citizens who identify with a different ideology than the government are more likely to protest. Contrary to Anderson and Mendes (Reference Anderson and Mendes2006), we do not find a higher level of mobilisation among election losers in new compared to old democracies. We explain the lack of differences through the mobilisation of election winners by right‐wing Eastern European governments.

Although protest undoubtedly gained in importance across Europe, citizens with different ideological beliefs do not take part in demonstrations as much as the normalisation argument would lead us to expect. As our research shows, the differences between ideological groups are a function of the past and present of the general dynamic of regime access. Hence, we believe that it is important to refine the common assumption of protest being a source of progressive political renewal and cultural change. As one of the major arenas of direct citizen involvement, the dynamic in protest mirrors general lines of conflict, contingent on the broader socio‐historical context. This in turn has implication on who gets heard, to which extent protest participation mitigates or increases political inequalities and, ultimately, whose policy preferences are enacted.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank three anonymous reviewers, Hanspeter Kriesi, Dorothee Bohle, Ondřej Císař, Sarah Engler, Béla Greskovits, Tim Haughton, Swen Hutter, Philippe Joly, Hannes Kröger, Jiří Navrátil and Jan Rovny for their valuable feedback. The paper further benefitted from discussions at the ECPR General Conference, the European Social Survey Regional Network Conference in Budapest and the CEU Annual Doctoral Conference. Endre Borbáth would also like to acknowledge financial support by the Volkswagen Foundation.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix A: descriptive statistics and additional models

Appendix B: regression tables with all estimates included in the paper

Appendix C: robustness checks – additional models

Appendix D: robustness checks – only countries with extensive over time coverage

Appendix E: robustness checks – distinguishing between the Northern and the Western European regions

Replication Files