Introduction

Generational gaps in electoral choice are a prominent feature of contemporary European politics (Lichtin et al. Reference Lichtin, Van Der Brug and Rekker2023; Rekker Reference Rekker2024; Mitteregger Reference Mitteregger2025). Research has shown that these gaps do not only reflect differences in issue preferences across cohorts but also the different weight that cohorts attach to different issue dimensions when choosing which party to vote for: what Jocker et al. (Reference Jocker, Van der Brug and Rekker2025) call ‘generational realignment’. For instance, among younger cohorts, preferences over sociocultural issues – most consistently, on the issue of immigration – tend to be a better predictor of both vote choice (Van der Brug and Rekker Reference Van der Brug and Rekker2021; Jocker et al. Reference Jocker, Van der Brug and Rekker2025) and left–right self-placement (De Vries et al. Reference De Vries, Hakhverdian and Lancee2013; Steiner and Hillen Reference Steiner and Hillen2021) than among older cohorts. These cohort differences have sometimes been linked to the political socialization context that more recent generations grew up in. As Jocker et al. (Reference Jocker, Van der Brug and Rekker2025, p. 921), put it, ‘the political understandings of today’s youth are shaped when sociocultural issues increasingly define party competition’. However, existing studies have not fully theorized the connection between issue salience, political socialization, and issue voting, nor have they tested explicitly whether it is really the exposure to salient new issues early on in life that produces lasting effects on voting behavior.

This paper proposes a novel framework for understanding how context-level issue salience (the collective importance political actors assign to an issue) shapes voters’ issue congruence (the extent to which individuals vote for the party they agree with on a given issue) via political socialization (the process of acquisition of enduring political preferences in adolescence).

The theory connects insights from two distinct traditions in the study of electoral behavior. For the ‘issue voting’ literature, voters tend to choose the party platform that matches their views on the issues they care about the most at the time of voting (Clarke Reference Clarke2009; Lefkofridi et al. Reference Lefkofridi, Wagner and Willmann2014; Gidron Reference Gidron2022; Brader et al. Reference Brader, De Sio, Paparo and Tucker2020; Steiner and Hillen Reference Steiner and Hillen2021). ‘Political socialization’ models, conversely, see electoral choices as downstream from preferences that form during the ‘impressionable years’ of adolescence and remain stable thereafter (Inglehart Reference Inglehart1967; Sears and Valentino Reference Sears and Valentino1997; Daniele et al. Reference Daniele, Aassve and Le Moglie2023). If both insights are true, then it follows that the salience contexts experienced in adolescence should have long-term implications for voter-party congruence, for two reasons. First, because adolescence is a critical period for the formation of partisan attachments, individuals are likely to sort themselves into parties based on the issues that are most salient at that time; once formed, these attachments tend to remain stable over the course of life (‘sorting’). Second, adolescence is also crucial for the development of political preferences, meaning that individuals who inherit familial partisan attachments are more likely to adopt party-consistent views on issues for which parties send clearer signals – that is, on salient issues (‘cueing’).

The offshoot of these two processes is that cohorts socialized in periods of high salience of a given issue should be relatively more likely to vote for parties that they agree with on that issue over their life course. We test the implications of this model on what we consider to be the most theoretically interesting issue: immigration. While immigration attitudes are rather stable both over time (Kustov et al. Reference Kustov, Laaker and Reller2021) and across cohorts (Lancaster Reference Lancaster2022), the relationship between immigration preferences and party choice is significantly heterogeneous on both accounts (Van der Brug and Rekker Reference Van der Brug and Rekker2021; Jocker et al. Reference Jocker, Van der Brug and Rekker2025). The increase in immigration issue voting over time has convincingly been linked to the rise in salience of the issue (Green-Pedersen Reference Green-Pedersen2006; Mader and Schoen Reference Mader and Schoen2019; Dennison and Geddes Reference Dennison and Geddes2019; Kustov et al. Reference Kustov, Laaker and Reller2021). However, we do not know whether these shifts in immigration salience also have long-term, generational consequences, i.e., if high-immigration salience environments have shaped generations of voters that are especially ‘congruent’ with their party of choice over the issue of immigration. Therefore, this paper’s research question can be stated more narrowly as: does growing up at a time when immigration is salient make people more likely to vote for parties whose immigration stance they agree with?

We address this question with two empirical studies: a cross-country analysis of survey data from 10 European countries (‘Study 1’) and a within-country study on survey data from Germany (‘Study 2’). Past issue salience measures in the two studies are drawn, respectively, from Comparative Manifesto Project data and from the ‘most important issues’ item fielded in repeated surveys in Germany since 1986. In both cases, our empirical strategy leverages differences in the timing and extent of the rise in salience of immigration across polities: in Study 1, across countries; in Study 2, across German federal states. This allows us to compare individuals from the same cohort but who were exposed to different immigration salience environments. To briefly preview our findings, both analyses point at a small but significant positive association between the salience of immigration experienced by individuals in their mid-to-late teenage years and their congruence with their party of choice on the issue of immigration.

This paper makes two main contributions. First, our findings speak to the literature on the realignment of European voters around sociocultural issues, most prominently immigration (De Vries et al. Reference De Vries, Hakhverdian and Lancee2013; Ford and Jennings Reference Ford and Jennings2020; Steiner and Hillen Reference Steiner and Hillen2021; Van der Brug and Rekker Reference Van der Brug and Rekker2021; Jocker et al. Reference Jocker, Van der Brug and Rekker2025). We show that there is a generational dimension to this process: for voters who came of age at times of high salience of immigration, assessment of parties’ stances on immigration is a stronger predictor of electoral choice. Moreover, by taking into account the cross-context heterogeneity and non-linearity of immigration salience trends in our empirical identification of salience context effects, our approach goes beyond existing studies, which differentiate simply between older and younger cohorts (Lichtin et al. Reference Lichtin, Van Der Brug and Rekker2023; Jocker et al. Reference Jocker, Van der Brug and Rekker2025). Second, this paper contributes to the literature on issue salience, a concept that is generally studied as an individual-level variable with proximate, short-term consequences for electoral behavior. Instead, we show that context-level salience can also be an important long-term influence on voter-party agreement.

Related literature

Political socialization

Starting with the seminal work by Mannheim (Reference Mannheim and Kecskemeti1952) and Hyman (Reference Hyman1959), a large literature in sociology and political science has argued that some fundamental political dispositions develop early on in life and remain relatively stable over individuals’ life course. Early research already identified a variety of agents of this process of ‘political socialization’, ranging from micro-level contexts like the family – which favor the transmission of values across cohorts – to the influence of broader social trends and events (what Hyman Reference Hyman1959, p. 132, calls ‘the Zeitgeist’), which instead may yield generational value change.

Subsequent empirical work has found extensive evidence that individuals who go through the same experiences at the same stage in their lives tend to develop distinct common outlooks and patterns of behavior. Socialization experiences have been linked to a variety of effects on political preferences (Colwell Quarles Reference Colwell Quarles1979; Russel et al. Reference Russel, Johnston and Pattie1992; Gimpel et al. Reference Gimpel, Celeste Lay and Schuknecht2003; Lau and Redlawsk Reference Lau and Redlawsk2018; Madestam and Yanagizawa-Drott Reference Madestam and Yanagizawa-Drott2012; Schuman and Cornig Reference Schuman and Cornig2012; Bartels and Jackman Reference Bartels and Jackman2014) and voting behavior (Firebaugh and Chen Reference Firebaugh and Chen1995; Franklin Reference Franklin2004; Bhatti et al. Reference Bhatti, Hansen and Wass2012; Dinas Reference Dinas2012; Erikson and Stoker Reference Erikson and Stoker2011; Rico and Jennings Reference Rico and Jennings2016; Daniele et al. Reference Daniele, Aassve and Le Moglie2023). A common finding in these studies is that the ‘impressionable years’ (Inglehart Reference Inglehart1967) of adolescence are central to the acquisition of political attitudes and habits that last a lifetime. Indeed, at this stage of psycho-social development, when individuals have less experience and therefore higher margins for cognitive gains, attitudes are more pliable and receptive to external stimuli (Sears and Valentino Reference Sears and Valentino1997; Bartels and Jackman Reference Bartels and Jackman2014).

Political socialization is most often associated with the circumstances in which young people first engage directly with politics in a democracy: during elections (Dinas Reference Dinas2012; Bhatti and Hansen Reference Bhatti and Hansen2012; Dassonneville and McAllister Reference Dassonneville and McAllister2018), when information is more readily available (Campbell and Wollbrecht Reference Campbell and Wollbrecht2006; Lau and Redlawsk Reference Lau and Redlawsk2018; Zeglovits and Aichholzer Reference Zeglovits and Aichholzer2014). Our argument develops two key findings in this literature: first, that party images and attachments formed when one first encounters party politics tend to remain ‘sticky’ thereafter (Tilley Reference Tilley2002; Jennings and Niemi Reference Jennings and Niemi2014; Tyler and Iyengar Reference Tyler and Iyengar2023); second, that the formation of enduring political attitudes depends on the availability and clarity of political information during the ‘impressionable years’ (Sears and Valentino Reference Sears and Valentino1997; Valentino and Sears Reference Valentino and Sears1998; Osborne et al. Reference Osborne, Sears and Valentino2011). These insights are reflected in our model’s distinction between ‘sorting’ and ‘cueing’ mechanisms, respectively.

At the same time, this paper advances our understanding of political socialization processes in two senses. First, while most existing studies focus either on issue or on party preferences, our contribution examines the congruence between the two. Secondly, we focus on the issue of immigration, which has not been central to this literature (with some recent exceptions, e.g., Jeannet and Drazanova Reference Jeannet and Drazanova2023 and Laaker Reference Laaker2024).

Issue salience and political change

The term ‘salience’ is often used but rarely defined (Epstein and Segal, Reference Epstein and Segal2000; Taylor and Fiske, Reference Taylor and Fiske1978; Wlezien, Reference Wlezien2005). On the one hand, it indicates the importance that political actors assign to different issues. On the other hand, it also captures the degree to which an issue is prominent in people’s minds (Taylor and Fiske Reference Taylor and Fiske1978). The concept has long been central to theories of issue voting (Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Mitchell and Welch1995; Bélanger and Meguid Reference Bélanger and Meguid2008), which posit that individuals tend to choose the political platform that matches their preferences on the most salient issues (Clarke Reference Clarke2009; Lefkofridi et al. Reference Lefkofridi, Wagner and Willmann2014; Gidron Reference Gidron2022; Brader et al. Reference Brader, De Sio, Paparo and Tucker2020; Steiner and Hillen Reference Steiner and Hillen2021). Indeed, a great deal of political competition in democratic polities is not so much about swaying voters’ issue stances as it is a struggle over which issues are made salient to them (Green-Pedersen Reference Green-Pedersen2006; Green-Pedersen Reference Green-Pedersen2007; Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Green-Pedersen and Jones2006; Rovny and Edwards Reference Rovny and Edwards2012; Wagner and Meyer Reference Wagner and Meyer2014; Lukes Reference Lukes2021).

Salience has emerged as a prominent conceptual tool to explain major patterns of political change of the last decades in Europe, including the ‘realignment’ of electorates away from the traditional economic left-right axis and the increase in support for new parties. In this perspective, these shifts are not primarily driven by changes in voters’ preferences but rather in their priorities: changes most prominently associated with the rise in salience of immigration and other non-economic issues (Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2008; Dennison and Geddes, Reference Dennison and Geddes2019; Ford and Jennings, Reference Ford and Jennings2020; Kustov et al,. Reference Kustov, Laaker and Reller2021; Dennison and Kriesi, Reference Dennison and Kriesi2023). Crucially for our purposes, recent work suggests that the extent to which immigration preferences are predictive of political and electoral outcomes has not only increased over time but also varies across cohorts (De Vries et al. Reference De Vries, Hakhverdian and Lancee2013; Steiner and Hillen Reference Steiner and Hillen2021; Steiner Reference Steiner2023; Mitteregger Reference Mitteregger2024; Jocker et al. Reference Jocker, Van der Brug and Rekker2025). This paper contributes to this line of research by clarifying the role of salience in this process of ‘generational realignment’: i.e., it is specifically cohorts who grew up in high-immigration salience environments that exhibit particularly high levels of voter-party agreement on immigration. Moreover, our operationalization of ‘issue congruence’ as the extent to which individuals say that they agree with their party of choice’s immigration position is novel in this literature, which instead tends to rely on the correlation between individuals’ and parties’ positions on polytomous scales.

Theory

Our argument juggles three key ‘variables’: issue salience during political socialization is theorized to affect issue congruence. We argue that this is due to how salient contexts affect partisanship formation through ‘sorting’ and attitude formation through ‘cueing’. These processes can be stylized as follows: on the one hand, individuals form long-lasting partisan identities on the basis of where parties stand on issues that are salient during their ‘impressionable years’ (sorting); on the other hand, in this phase, individuals form partisanship-consistent attitudes more easily on issues where they receive clearer signals as to where parties stand (cueing).

Crucially, the sorting and cueing mechanisms make two distinct assumptions as to the nature of adolescents’ political attitudes: the former assumes that issue preferences are exogenous, and partisanship follows from the interplay of preferences and context; the latter assumes that partisanship is exogenous, and issue preferences follow from the interplay of partisanship and contextFootnote 1 . In fact, these processes are likely endogenous and simultaneous, and this paper is necessarily agnostic as to their relative weight.Footnote 2 At any rate, for our purposes, both theoretical mechanisms lead us to the same conclusion: high salience of an issue during an individual’s formative years should increase her likelihood to vote for parties that align with her views on the issue thereafter.

Before proceeding to discuss the mechanisms in turn, two relatively prosaic assumptions must be made. First, political choice is bounded: there is not an infinite number of parties with enough combinations of issue positions to satisfy all voters, so that a degree of issue incongruence between (at least some) voters and their party of choice is unavoidable. Secondly, issue salience context at the time of political socialization is to some extent exogenous: while of course it amounts to the sum of the individual-level prominence each voter attaches to the issue, it is also heavily influenced by political events outside of any one voter’s control.

Sorting

Our stylized theory of partisanship formation starts from the assumption that adolescents encounter politics already having developed a set of basic dispositions towards social objects. These may be formed through moral reasoning, a function of self-interest, or otherwise ‘inherited’ from their families and social context – likely, a combination of all three. In this framework, socialization is a distinctive window of time because partisanship is formed. We further posit that adolescents evaluate the available choice set of political platforms, attaching different weights to different issues: the more they believe an issue to be important, the more weight it will carry in determining party preference (RePass Reference RePass1971; Brader et al. Reference Brader, De Sio, Paparo and Tucker2020; Costello et al. Reference Costello, Toshkov, Bos and Krouwel2021). Much has been written, for instance, on the plight of ‘left-authoritarian’ voters in Europe, who tend to find themselves cross-pressured between left-liberal and right-authoritarian parties, and who have increasingly aligned themselves with the right as ‘sociocultural’ issues have come to the fore of political competition (Lefkofridi et al. Reference Lefkofridi, Wagner and Willmann2014; Walgrave et al. Reference Walgrave, van Erkel, Jennart, Lefevere and Baudewyns2020; Steiner and Hillen Reference Steiner and Hillen2021; Gidron Reference Gidron2022).

In this process of platform evaluation, the weights attached to each individual issue are in turn endogenous to the issue salience environment through two channels. The first is straightforward: individual-level salience. The more the public, the media, and parties talk about an issue, the more likely it will be that an individual will think and care about it. The second consists in how high issue salience reduces informational costs. When an issue dominates the agenda, information about the parties’ policy choice set on that issue will be ‘cheaper’, making partisan sorting on it less cognitively demanding than on issues that parties do not feel the need to emphasize (and therefore require more information-seeking ‘work’ from voters).

Finally, in this perspective, partisan choices made during socialization are particularly relevant to partisan identity, as voting reinforces partisan loyalty (Sears and Valentino Reference Sears and Valentino1997; Sears and Funk Reference Sears and Funk1999; Dinas Reference Dinas2014). Thus, even if the process of policy platform evaluation and party choice may be iterated at every election, later in an individual’s life, this will take place downstream from previous choices, which have cemented partisan identities. Thus, salience contexts experienced during political socialization – when, by assumption, partisanship is something akin to a blank slate – should keep casting a shadow on party choice for voters.

A possible fly in the ointment for our argument is that, over an individual life course, the choice set of parties – and even political systems in toto – may change, making past partisan choices and loyalties moot. However, we believe that contextual factors affecting partisan sorting at the time of socialization can still influence long-term voter-party issue congruence. As well as partisan identity, political choice in adolescence may in fact crystallize forms of ‘macro-partisanship’ (such as being ‘on the left’, or ‘on the right’, or ‘pro-independence’, or ‘Peronist’), which are stable in spite of party label churn within these ideological families. Thus, even if parties come and go, individuals’ socialization experience may still have an influence over the choice set of parties one considers (Oscarsson and Rosema Reference Oscarsson and Rosema2019).

Cueing

If the preceding paragraphs outlined a process through which individuals endowed with issue preferences select themselves into a partisan identity conditional on issue salience, the mechanism detailed below is the exact mirror image: the process through which individuals endowed with partisan identities develop their issue preferences conditional on issue salience. The assumptions about adolescents’ political attitudes are correspondingly flipped around: here, individuals ‘inherit’ partisanship from their parents and, more generally, familial background (Campbell and Wollbrecht Reference Campbell and Wollbrecht2006; Rico and Jennings Reference Rico and Jennings2016), and their policy preferences are endogenous to the interaction between partisanship and context. Specifically, people will tend to adopt issue stances that are consistent with their pre-existing partisanship and thus increase party-voter issue congruence, in line with the findings of existing research on polarization and partisan-motivated reasoning (Levendusky Reference Levendusky2010; Lavine et al. Reference Lavine, Johnston and Steenbergen2012; Stanley et al. Reference Stanley, Henne, Yang and De Brigard2020).

A ‘cue’ is ‘a message that people may use to infer other information and, by extension, to make decisions’ (Bullock Reference Bullock2011, p.4). Cues allow individuals to form their stances on different issues in a cognitively cheap way (Vössing Reference Vössing2021) by matching the positions of co-partisan elites (Mondak Reference Mondak1993). The higher the context-level salience of an issue, the easier it will be for voters to acquire information on where parties stand on it. As a consequence, partisanship-consistent position-taking will be easier on issues that are cued more heavily than on issues that are underplayed by parties, resulting in higher voter-party congruence on salient issues than on non-salient ones, as documented empirically across a range of political contexts (Lefkofridi et al. Reference Lefkofridi, Wagner and Willmann2014; RePass Reference RePass1971; Neundorf and Adams Reference Neundorf and Adams2018; Walgrave et al. Reference Walgrave, van Erkel, Jennart, Lefevere and Baudewyns2020; Costello et al. Reference Costello, Toshkov, Bos and Krouwel2021).

The last step left to do to complete the argument is to connect this idea of easier partisanship-consistent position-taking on salient issues to the timing of political socialization. The core of the ‘impressionable years’ thesis is that ‘individuals are most susceptible to political attitude and behavior change at younger ages’ and that ‘political attitudes crystallize as individuals near adulthood, making it improbable that these attitudes will shift during one’s adult years’ (Rosenthal and Farhart Reference Rosenthal and Farhart2023, p. 1936; see also Niemi and Jennings Reference Niemi and Jennings1991; Krosnick and Alwin Reference Krosnick and Alwin1989). Under this assumption, the political attitudes that are more heavily cued during someone’s early experience of politics should remain, over time, the ones that are most consistent with their partisanship. Conversely, attitudes that form and ‘crystallize’ in a relatively cue-free socialization context are likely to be less bundled with partisan or ideological belief systems.Footnote 3

Empirical challenges and approach

Summing up, our theory section has outlined two pathways through which issue salience at the time of an individual’s political socialization may lead to higher lifelong voter-party congruence on such issue. We now proceed to test this hypothesis specifically with respect to the issue of immigration. We chose immigration as an issue that is especially interesting from a theoretical point of view, as the stability of immigration attitudes over time and across cohorts is ostensibly at odds with evidence for a ‘realignment’ of voter behavior along this issue dimension. Moreover, there is an empirical advantage in focusing on immigration, as it yields rich cross-cohort and cross-polity variation on the independent variable. In fact, while many European countries have seen a substantial increase in the political salience of immigration in the last decades, this general trend masks marked cross-country differences in timing, pace, level, and fluctuations (Dancygier and Margalit Reference Dancygier and Margalit2019). The central hypothesis is, therefore, that voters who were exposed to high salience of immigration when they were adolescents will be more likely to vote subsequently for parties whose immigration stance they agree with.

Testing this hypothesis poses significant empirical challenges and obstacles to inference. To overcome them, we use two studies employing four different data sources with complementary strengths; moreover, we make extensive use of auxiliary analysis, which allows us to test a wide range of model assumptions about how and when political socialization takes place.

The first challenge is that political socialization contexts are cohort-level ‘treatments’, but cohorts may differ from each other for a number of reasons other than the salience environment.Footnote 4 Our approach to this problem consists in deriving independent variables – capturing the extent of individuals’ exposure to high-immigration salience environments in their ‘impressionable years’ – that vary within cohorts as well as across them. To do so, we leverage differences in historical immigration salience trends across polities: in Study 1, across European countries; in Study 2, across German federal states. It is therefore key to our empirical strategy that the extent and timing of shifts in immigration salience are sufficiently heterogeneous across the polities in our sample. The key advantage of relying on cross-polity variation in exposure to salience contexts is that this approach sidesteps the well-known identification problem that a cohort, in its linear form, is perfectly multicollinear with age and period (Mason et al. Reference Mason, Mason, Winsborough and Poole1973; Bell Reference Bell2021). While our independent variable is measured at the cohort level, individuals with the same birth year are assigned different values depending on their polity, so that this variable is not a function of birth year; therefore, it can be jointly included in a model with age or birth-year controls. However, our approach requires some assumptions: first, that the effects accounted for by birth-year (or age) controls are homogeneous across polities; second, that polity effects are constant across cohorts.

The second challenge is data scarcity. This is most acute for the independent variable: while measures of issue salience are widely established in political science, for our purposes we need a reliable and consistent measure going quite far back in time. For instance, the political socialization of a 60-year-old surveyed in 2020 took place at some point in the late 1970s. Here, we face a trade-off between (1) manifesto-based measures of salience, which can stretch back to post-war elections but are measured only episodically, and (2) survey-based measures of public issue salience, which are more fine-grained but do not stretch back in time sufficiently to cover the socialization environment of all adult participants in recent surveys. In the two studies presented, we adopt the two alternative strategies in turn. Data scarcity is also a problem for the dependent variable: voter-party congruence on immigration.Footnote 5 The standard item used in most surveys – asking ‘the best party on the most important issue’ – is not very helpful, as it would limit the analysis to the (non-random) subset of respondents who choose immigration as their top concern. Therefore, we are constrained to surveys where all respondents are asked to rate parties specifically on their immigration position.

The final challenge is that we can only get approximate priors from theory about how political socialization works, but to conduct the analysis, we are often forced to make some important simplifying assumptions about it. This is particularly relevant for three aspects of the socialization process hypothesized. First, we cannot know ex ante to what extent socialization is primarily something that happens as one ‘grows up’ and to what extent it is contingent on the occurrence of events like elections at that stage of development. Secondly, as discussed in the theory section, we are necessarily agnostic as to whether political socialization is primarily about developing partisanship from preferences or about developing preferences from partisanship. Thirdly, we cannot neatly distinguish at what exact age the relevant process of political socialization starts and when it ends. The literature suggests that this should coincide with late adolescence and with the first experience of electoral participation, but time spans are likely to vary substantially between individuals and across contexts.

Our overall approach to these issues is one of maximal flexibility, probing our relatively ‘loose’ assumptions extensively across a series of alternative models. As for the first issue, the two-study setup allows us to employ operationalization of salience contexts that assume either episodic socialization (using election year-level data in Study 1) or continuous socialization (using year-level data in Study 2). To address the second issue, we model the assumptions of exogenous partisanship (assumed by the ‘cueing’ mechanism) and exogenous immigration preferences (assumed by the ‘sorting’ mechanism) by introducing proxies for these variables as covariates in alternative specifications of the models. Of course, as we suspect these are formed concurrently through complex co-causal processes, these control variables are bound to be post-treatment to some extent; thus, in the main model specification, we do not control for either. Finally, we address the third issue by repeating the analysis with versions of the independent variable measured at many different times in an individual’s life, from plausible ‘impressionable years’ to clearly implausible ones (e.g., the context experienced in old age or infancy). These alternative specifications thus serve a similar function as placebo tests, although – as we only have a fuzzy distinction between ‘true’ timings of socialization and ‘implausible’ ones – they cannot be, strictly speaking, labeled as such.

Study 1: cross-country analysis

Data and measures

We employ data from Europinions, a web-based survey conducted between 2017 and 2019 on samples of adults from ten European countries (Goldberg et al. Reference Goldberg, van Elsas, Marquart, Brosius, de Boer and de Vreese2021): the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Spain, Czechia, Greece, France, Poland, and Sweden. Two versions of the dependent variable were recorded from a battery of items asking, ‘How suitable do you think each of the following parties is to deal with the issue of immigration?’ about the six top parties in each country (eight for the Netherlands), with possible responses ranging from 1 (completely unsuitable) to 7 (completely suitable). The item was asked in all samples only once: in April 2019, ahead of the European Parliament elections in May, so the data structure is that of a simple cross-section. First, a congruence score (immigration) integer variable was coded by assigning to each respondent the 1–7 point rating of the competence on immigration of the party the respondent intends to vote for in a national election. Secondly, we coded a binary congruence (immigration) variable, taking the value of 1 if the respondent’s party of choice is the top rated on immigration (inclusive of ties), and taking the value of 0 if the respondent rates a different party as more suitable than their party of choice to deal with the issue. Respondents who did not report a vote intention, did not rate parties on the issue, or intended to vote for a minor party (i.e., one that did not appear on the issue competence rating item) were droppedFootnote 6 .

We coded from Europinions also a series of ‘base’ control variables included in all models: age, education, gender, domicile, religiosity, and strength of party identification Footnote 7 . Moreover, we code respondents’ left-right self-identification, the party family (of their vote intention), and an immigration attitudes scale: we use these as covariates in model specifications where we assume either exogenous partisanship or exogenous preferences.Footnote 8 Finally, for the purposes of conducting placebo tests, ‘congruence score’ and ‘binary congruence’ variables analogous to our main dependent variables were coded for the four other issues that Europinions respondents were asked to rate parties’ suitability over: the EU, social welfare, the economy, and terrorism.

The key independent variable of interest was measured from Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP) data on parties’ thematic focus in their electoral manifestos (Lehmann et al. Reference Lehmann, Franzmann, Al-Gaddooa, Burst, Ivanusch, Regel, Riethmüller, Volkens, Weßels and Zehnter2025). It was computed at the country-election level as the sum of the number of quasi-sentences relating to ‘multiculturalism’ (CMP codes 607 and 608) in each manifesto as a percentage of all policy quasi-sentences, weighted by the party’s share of the vote in that electionFootnote 9 . In an election year where no party has a multiculturalism-related pledge, the variable takes the value of 0; in theory, the variable can take values up to 100 in a hypothetical election where all party manifestos include only multiculturalism-related policy quasi-sentences.Footnote 10 Figure 1 shows country-election estimates of multiculturalism salience from the CMP for the countries in the Europinions sample used for Study 1. The increase in salience of the issue over time varies substantially across countries, reaching the highest values in Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden. While recent elections tend to coincide with increased salience of the issue, this upward trend is not monotonic, with earlier ‘spikes’ in the 1990s in countries like France and Germany (as observed also in Study 2).

Figure 1. Multiculturalism salience in manifestos, by country election, from CMP.

Of course, ‘salience of multiculturalism’ is not the same as ‘salience of immigration’; however, this is the closest proxy we can obtain from text data without extensive recoding of the primary sources, which add up to over 1,200 manifestos in over 150 elections. Reassuringly, however, the CMP multiculturalism salience measures for the manifestos of the countries and parties included in the analysis are highly correlated (

![]() $ r=0.78$

) with those compiled by Dancygier and Margalit (Reference Dancygier and Margalit2019), who undertook a substantial manual classification effort (the ‘Immigration in Party Manifestos’ dataset) for a subset of country elections, limiting their analysis to the main left and right parties in each contest.Footnote

11

Moreover, the literature on multiculturalism highlights how it was a key frame for political mobilization and competition on the issue of immigration in Europe (Ivarsflaten and Sniderman Reference Ivarsflaten and Sniderman2022). In sum, although historically and in a strictly theoretical sense multiculturalism is not the same as immigration, in this particular context it is a very proximate concept.

$ r=0.78$

) with those compiled by Dancygier and Margalit (Reference Dancygier and Margalit2019), who undertook a substantial manual classification effort (the ‘Immigration in Party Manifestos’ dataset) for a subset of country elections, limiting their analysis to the main left and right parties in each contest.Footnote

11

Moreover, the literature on multiculturalism highlights how it was a key frame for political mobilization and competition on the issue of immigration in Europe (Ivarsflaten and Sniderman Reference Ivarsflaten and Sniderman2022). In sum, although historically and in a strictly theoretical sense multiculturalism is not the same as immigration, in this particular context it is a very proximate concept.

The main independent variable, multiculturalism salience in the Europinions dataset, takes the value of the CMP country-election-level multiculturalism salience in the first election the respondent was eligible to vote in, using imputed birth year as the linking variable. This follows from the assumption in the political socialization literature (Sears and Valentino Reference Sears and Valentino1997; Bhatti et al. Reference Bhatti, Hansen and Wass2012; Daniele et al. Reference Daniele, Aassve and Le Moglie2023) that the first election after the age of majority is a particularly important catalyst of the development of political attitudes. The value is recorded as ‘missing’ for respondents who were older than 23 in the first election they were eligible to vote in (this is the case for the older Czech, Hungarian, Polish, Greek, Spanish, and East German respondents who came of age prior to the democratic transition). Moreover, we use the same protocol to record, for each respondent, (1) the salience of multiculturalism in the second election they were eligible to vote in, the third election they were eligible to vote in, the fourth, and so on; and (2) the salience of multiculturalism in the election before they became eligible to vote, two elections before they became eligible to vote, three elections before, and so on. Thus, noting

![]() $ t$

as the first election the respondent was eligible to vote, we code values of multiculturalism salience from

$ t$

as the first election the respondent was eligible to vote, we code values of multiculturalism salience from

![]() $ t-10$

to

$ t-10$

to

![]() $ t+10$

. Finally, we recorded placebo-independent variables, recording the salience of other issues (in the first election after vote eligibility): welfare, economic ideology, national way of life, moral issues, labor unions, foreign policy, the European Union, the environment, and corruption. Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for the main variables of interest.

$ t+10$

. Finally, we recorded placebo-independent variables, recording the salience of other issues (in the first election after vote eligibility): welfare, economic ideology, national way of life, moral issues, labor unions, foreign policy, the European Union, the environment, and corruption. Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for the main variables of interest.

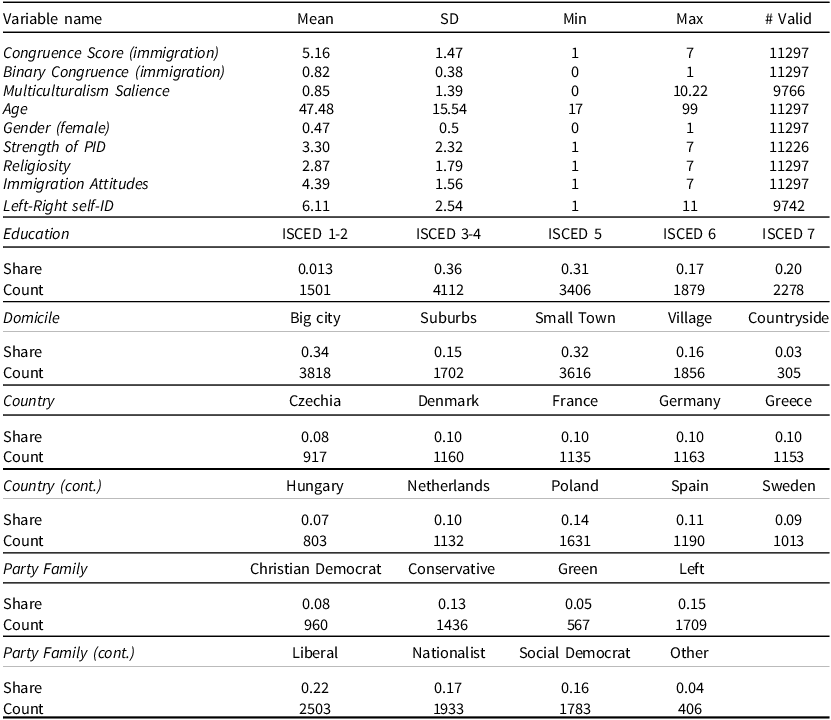

Table 1. Descriptive statistics (Study 1)

We employ linear regression models to gauge the change in the respondent’s rating of their own party on immigration associated with changes in the salience of multiculturalism in the first election a respondent was eligible to vote in. In all model specifications, we control for a fixed set of base covariates: gender, age, age squared, domicile, education, religiosity, and strength of party identification, and we include country fixed effects. Note that, as the data is cross-sectional, age and cohort are perfectly collinear; thus, controlling for a polynomial of age is the same as controlling for cohort; within the limitations of cross-sectional data, this adjustment should net out some of the cross-cohort heterogeneity due to factors other than socialization contexts. The main model (1) regresses congruence score (immigration) on the independent variable multiculturalism salience and the base covariates. In model (2), we further control for left-right self-positioning; in model (3), we let the slope for left-right self-positioning vary by country; in model (4), we control for the nominal variable party family instead of left-right self-positioning. Models 2–4 thus assume exogenous partisanship. In model (5), we control for immigration attitudes; in model (6), we let the slope for immigration attitudes vary across countries. We employ identical model specifications and control sets in logistic regression models where we regress binary congruence (immigration) on salience plus covariates. Throughout, we cluster standard errors at the country/birth-year level to account for the clustered nature of treatment assignment.

The linear and logistic regression coefficients for both sets of models are presented in Table 2 in Section 5.2. We repeat this exercise, substituting measures of salience of multiculturalism in elections other than the first the respondent was eligible to vote in for the main independent variable. These alternative estimates of the relationship between salience context and congruence serve primarily as a term of comparison for the main estimate and are plotted in Figure 2 in section ‘Results’ alongside average marginal effects from the main models. Finally, in section ‘Further analysis’, we discuss a raft of robustness checks, placebo tests, and additional analysis drawing on different data sources that we employ to probe the validity of the analysis’ substantive inferences.

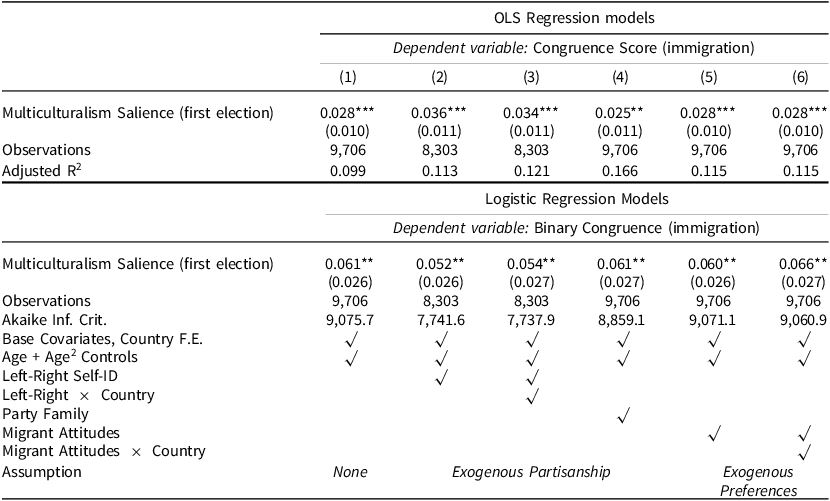

Table 2. Estimated change in congruence associated with a 1-point increase in salience of multiculturalism in the first election the respondent was eligible to vote in. The top panel reports OLS coefficient estimates, and the bottom panel reports log-odds coefficients. Base controls include gender, education, domicile, religiosity, and strength of party identification. Standard errors are clustered at the birth-year/country level

Note: *p

![]() $ \lt$

0.1; **p

$ \lt$

0.1; **p

![]() $ \lt$

0.05; ***p

$ \lt$

0.05; ***p

![]() $ \lt$

0.01.

$ \lt$

0.01.

Figure 2. Estimated change in own party’s rating on immigration (top panel) or probability of being ‘congruent’ on immigration (bottom panel) associated with a 1 pt increase in multiculturalism salience in past election (

![]() $ t$

, in red is first election R was eligible). ATEs presented correspond to regression coefficients from model 1 in Table 2; analogous visualizations of results across all 6 model specifications are presented in the Appendix, section A.1.

$ t$

, in red is first election R was eligible). ATEs presented correspond to regression coefficients from model 1 in Table 2; analogous visualizations of results across all 6 model specifications are presented in the Appendix, section A.1.

Results

Table 2 shows the results of a series of regression models where the two versions of the dependent variable – congruence score and binary congruence – are regressed on the salience of multiculturalism in the first election the respondent was eligible to vote in. For ‘congruence score’, we employed linear regression so that the coefficients in the top panel of the table indicate the estimated change in the respondent’s rating of their own party of choice on the issue of immigration associated with a one-point increase in the salience of multiculturalism when they entered the electorate. For ‘binary congruence’, we employed logistic regression so that the coefficients are to be interpreted as the expected change in log-odds of the probability of being ‘congruent’ on immigration (i.e., rating one’s party of choice as the best to handle the issue among those surveyed). The six model specifications all include controls for age, age squared, gender, education, domicile, religiosity, and strength of party identification, as well as country fixed effects. Models 2 through 4 further control for variables capturing partisanship; models 5 and 6 control for attitudes to immigration, in line with the theoretical mechanisms that assume either partisanship or issue preferences as exogenous to political socialization.

Substantively, the OLS models predict that someone who first became eligible to vote in an election that records the highest levels of salience in our data (10.22, representing the percentage of manifesto sentences related to multiculturalism) would rate their party of choice 0.28–0.34 points higher than someone socialized in an election where immigration was not salient at all. While the log-odds coefficients for the ‘multiculturalism salience’ variable in the bottom panel of the table are not easily interpreted substantively, the associated average marginal effects are comprised between 0.008 and 0.01. This corresponds, approximately, to an average 0.8–1 percentage point increase in the probability of ranking one’s party as the best to handle immigration for each unit increase in salience. The results are consistent with the hypothesis that exposure to high migration salience environments in one’s formative years leads to higher voter-party congruence on the issue of immigration. Crucially, we find that socialization effects remain roughly constant in magnitude and significance even when we condition on partisanship (models 2–4) and on attitudes towards immigration (models 5–6). This implies that it is unlikely that the higher degree of congruence associated with the experience of high immigration salience during the ‘impressionable years’ is due to these cohorts being distinctively more likely to side with certain parties or having distinctively pro- or anti-immigration views. Rather, it suggests that individuals belonging to these cohorts are more neatly ‘sorted’ into parties whose immigration positions they share, regardless of the specific type of parties and the polarity of these individuals’ immigration positions.

Figure 2 shows the results of the additional analysis conducted by re-running the same regression model as ‘model 1’ in Table 2, but varying the timing at which the salience of multiculturalism is measured. In both panels, the solid circles in red represent average marginal effect estimates, with 95% confidence intervals, for salience measured in the first election the respondent became eligible to vote in. Specifically, the solid circle in red in the top panel represents the predicted change in the congruence score associated with a one-point increase in multiculturalism salience in the first election the respondent was eligible to vote in, and the solid circle in red in the bottom panel represents the predicted change in the probability of being ‘congruent’ on immigration. Letting the first election the respondent was eligible to vote be

![]() $ t$

, the open blue circles show instead the average marginal effects for ‘multiculturalism salience’ measured at

$ t$

, the open blue circles show instead the average marginal effects for ‘multiculturalism salience’ measured at

![]() $ t-1$

,

$ t-1$

,

![]() $ t-2$

, etc. (i.e., when the respondent was younger, or in some cases unborn), as well as

$ t-2$

, etc. (i.e., when the respondent was younger, or in some cases unborn), as well as

![]() $ t+1$

,

$ t+1$

,

![]() $ t+2$

, (i.e., when the respondent was older). As discussed, these alternative estimates are not, strictly speaking, placebos: issue salience is likely correlated across elections, and changes in partisanship and attitudes may take place at different times over an individual’s life course, so that we should not necessarily expect a null. However, they are a useful benchmark for understanding to what extent the context experienced in one’s ‘impressionable years’ is distinctive in its consequences for party-voter congruence.

$ t+2$

, (i.e., when the respondent was older). As discussed, these alternative estimates are not, strictly speaking, placebos: issue salience is likely correlated across elections, and changes in partisanship and attitudes may take place at different times over an individual’s life course, so that we should not necessarily expect a null. However, they are a useful benchmark for understanding to what extent the context experienced in one’s ‘impressionable years’ is distinctive in its consequences for party-voter congruence.

In the top panel of Figure 2, where the dependent variable is ‘congruence score’, the salience of multiculturalism in the first election a respondent was eligible to vote in is the only measure that is a consistently significant positive predictor of congruence: alternative socialization estimates have statistically and substantially insignificant average marginal effects across model specifications (see also Appendix section A.1).Footnote 12 In the bottom panel of Figure 2, where the dependent variable is ‘congruence score’, we find a comparable estimate for the slope of multiculturalism salience in the last election before respondents became eligible to vote. We have reasons to believe that this can be interpreted substantively: adolescents may be receptive to political cues before they become eligible to vote. In fact, this finding actually chimes with the findings from Study 2, which suggest that the clearest effects of socialization context correspond to immigration salience measured at 16 and 17 years of age, so just before voting age (18 in most countries). Overall, these results are consistent with the established finding that the first election is particularly important for the formation of political habits (Pacheco Reference Pacheco2008; Dinas Reference Dinas2012; Daniele et al. Reference Daniele, Aassve and Le Moglie2023); however, they also suggest that some of these processes may start – at least for some individuals – slightly earlier than legal adulthood, when adolescents first start paying attention to political news.

Further analysis

In part A of the Appendix, we present a series of ancillary analyses of the cross-country analysis: robustness checks, placebo tests, and a new analysis of party-voter alignment on immigration with European Social Survey and Chapel Hill Expert Survey data.

Robustness checks

Our main findings are robust to a number of alternative modeling choices:

-

Alternative Operationalization of Congruence: We find similar results to the main models using an alternative dependent variable, which we label ‘relative congruence’, coded by taking the difference in rating between one’s own party and the mean rating of other parties (section A.2).

-

Sample Restrictions: We also re-ran our models excluding iteratively one country from the sample. The results are all positive and of consistent magnitudes with the main estimates, although statistical significance is reduced in some cases (section A.3).

-

Alternative Operationalization of Covariates: The models are robust to different specifications of the ‘age’ control as linear or cubic functions (section A.4.1), as well as to conditioning on experience of economic downturns in formative years (section A.4.2).

-

Alternative Operationalizations of Immigration Salience: We are able to replicate the results of our main models with two alternative operationalizations of salience: (1) an alternative coding of the CMP data, which only counts negative mentions of multiculturalism (section A.4.3); and (2) an alternative ‘immigration salience’ measure, which relies on V-Party expert evaluations of issue emphasis placed by parties on different issues (section A.4.4).

Placebo tests

In section A.5 of the Appendix, we reproduce the main analysis, substituting for the dependent variable analogous measures of congruence on issues other than immigration and substituting for the independent variable analogous measures of salience of issues other than multiculturalism. We mostly obtain null results, except for some small positive coefficients for dependent variables capturing respondents’ agreement with their own party on the issues of terrorism and welfare policies (which are issues adjacent to immigration)Footnote 13 . However, these coefficients are not consistently significant across specifications of the model and of the dependent variables.

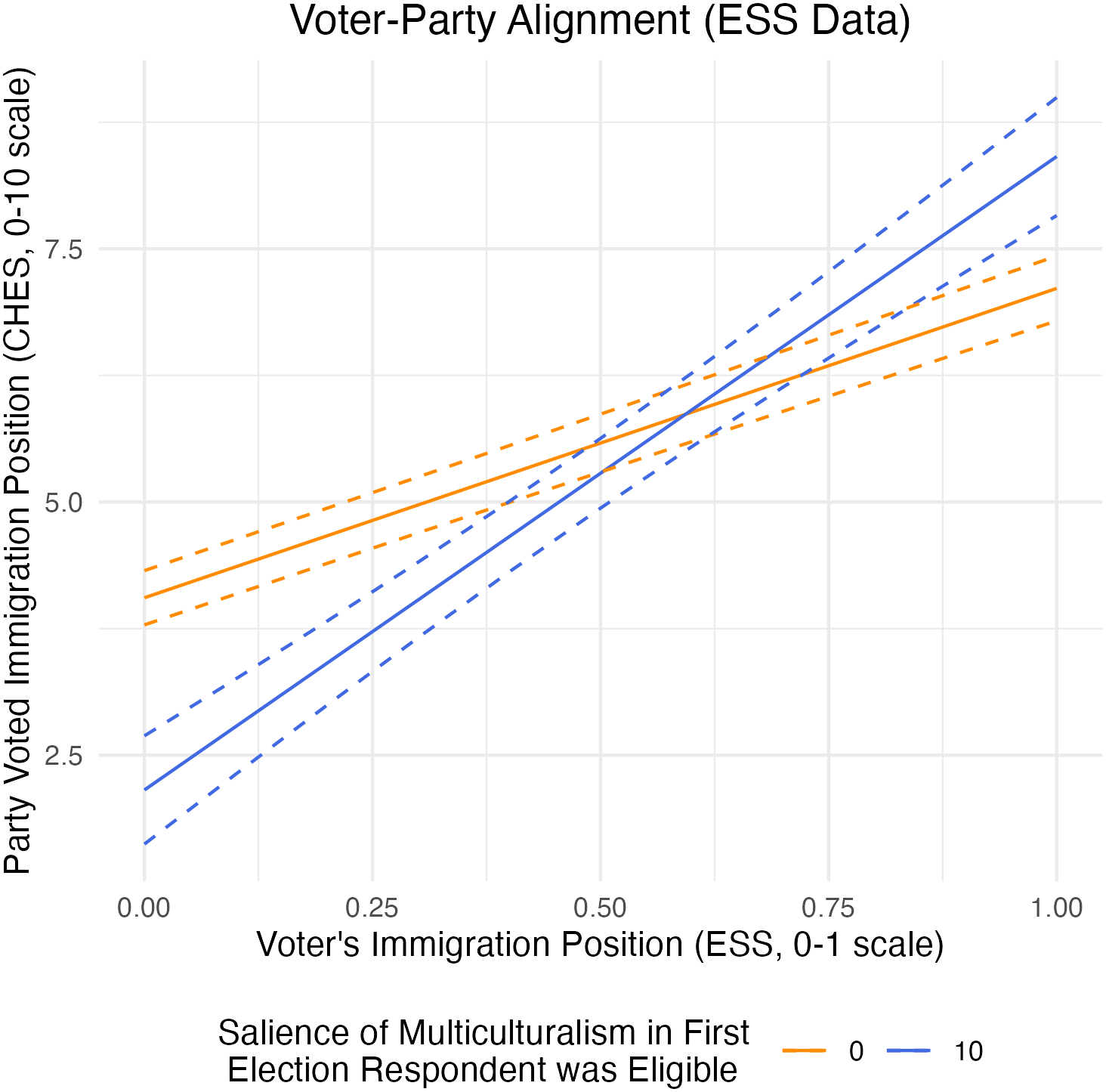

Data triangulation: analysis with the European Social Survey (ESS)

In section A.6 of the Appendix, we further validate our measure of immigration salience at the time of socialization by showing that it also predicts higher levels of alignment between voters’ positions on immigration and the immigration stances of their party of choice. To do so, we use data from the same 10 countries as in Study 1 on voters’ preferences (from the European Social Survey, ESS waves 3–10, 2006–2022) and on parties’ positions (from Chapel Hill Expert Survey, CHES, 2006–2019) (ESS 2024; Jolly et al. Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022). Extending the ‘Age-Period-Cohort’ modeling approach adopted in Jocker et al. (Reference Jocker, Van der Brug and Rekker2025), we fit a series of OLS models, where the vector of immigration positions of the party each respondent voted for in the past national election is regressed on each respondent’s own immigration position. Crucially, we interact the respondent’s immigration position with both the cohort (a categorical ‘decade of birth’ variable) and our moderator of interest: multiculturalism salience in the first election of eligibility. Conditioning on a number of ‘base’ controls – age group, gender, education, religiosity, social class, and country-year fixed effects – and further political covariates in alternative model specifications – left-right self-placement and party family – we find robust evidence in favor of the testable implications of our argument. That is, the relationship between individuals’ immigration attitudes and the immigration position of their party of choice is stronger among those who grew up at times of higher salience of immigration. This core finding is visualized in the predicted values plot of Figure 3; regression tables, additional results, and a more detailed outline of this analysis are provided in section A6 of the Appendix.

Figure 3. Predicted voter-party alignment on immigration (ESS data): marginal means and 95% confidence intervals. The marginal means are computed from an OLS model regressing the voter’s party of choice’s immigration position on the voter’s immigration position, interacted with salience of immigration in the first election of eligibility; the model controls for age group, cohort, cohort

![]() $ \times $

voter’s immigration position, social class, education, religiosity, and country-year fixed effects.

$ \times $

voter’s immigration position, social class, education, religiosity, and country-year fixed effects.

Study 2: within-country analysis

Data and measures

The within-country analysis draws on data from two long-running German surveys: ARD DeutschlandTrend (ARD-Landesrundfunkanstalten and Infratest-dimap 2023; data for 1998–2021) and Politbarometer (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2023; data for 1986–2021). The former was used to measure immigration issue congruence and the individual-level covariates, while the latter was used to estimate past immigration issue salience at the federal state/year level. Issue congruence is measured from survey items that read, ‘I will now read you some political objectives. Please tell me which party in Germany you trust the most to achieve them. [Carry out a good policy on immigration and asylum]’. The question is available for 13 years between 1998 and 2021. We code the dependent variable, binary congruence (immigration), by assigning the value of 1 if the respondent’s preferred party to deal with immigration is the same as their vote intention, and 0 if they are different. Respondents without a stated vote intention are excluded from the analysis. We code similar ‘placebo’ dependent variables for other political objectives asked in the same survey years at least as often as the immigration question: advocating for social justice, securing retirement pensions in the long term, implementing a good labor market policy, attracting investments in Germany, implementing a good healthcare policy, implementing a good foreign policy, and implementing a good environmental policy. From ARD DeutschlandTrend data, we also code covariates for age, birth year, education (three-category), income (tercile of survey item bands), federal state, gender, and party.

The independent variable is measured from the Politbarometer data as the weighted percentage of respondents who cite ‘immigration’ or related terms as one of the top two concernsFootnote 14 at the federal state-year level. Figure 4 visualizes these estimates. Crucially for our purposes, there are discernible cross-state differences in trends of immigration salience. In the first wave of high salience of immigration – which coincided with ‘one of the most contentious political debates in post-war Germany’ (Kirchhoff and Lorenz Reference Kirchhoff, Lorenz, Rosenberger, Stern and Merhaut2018, p. 51) on asylum reform, following a spike in immigration (Münz and Ulrich Reference Münz and Ulrich1998; Green Reference Green2013) and high-profile episodes of anti-migrant violence and mobilization (Karapin Reference Karapin1999) – the issue was much more salient in Western than in Eastern States.

Figure 4. Estimates of state-year-level salience of immigration (data from Politbarometer).

This is likely due to two main factors. First, the dramatic disparity in economic conditions following reunification meant that opportunities for migrant labor were heavily concentrated in the West – which saw its foreign population increase from 4.5m to 7m between 1988 and 1994 (Münz and Ulrich Reference Münz and Ulrich1998, p. 38) – leading to highly geographically unequal migration pressures. In fact, unlike the East, the West had been exposed to such pressures since the 1980s (Thränhardt Reference Thränhardt2002). Secondly, in this phase the East was undergoing massive economic transformations, putting pressing issues of unemployment, labor market disruption, hardship, and displacement to the fore of East Germans’ concerns (Burda and Hunt Reference Burda and Hunt2001; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt2003).Footnote 15 The salience environment of the 1990s migration wave contrasts markedly with the context of the second ‘peak’ in migration concerns, which coincided with the 2015–2016 European migrant crisis. This was a heavily ‘nationalized’ phase of migration politics: unlike the 1990s, most newcomers were asylum seekers rather than labor migrants, so that Germany’s asylum quota system distributed migration pressures more evenly over the country’s territory than had been the case in the 1990s (Schaub et al. Reference Schaub, Gereke and Baldassarri2021).

Individual-level survey data from ARD DeutschlandTrend is linked to immigration salience data at the state/year level via the respondent’s state and their age. Specifically, letting

![]() $ x$

be any age between 12 and 65, each respondent is associated with an immigration salience at age x variable, which corresponds to the average immigration salience estimate from Politbarometer for that state in the three years when the respondent was between

$ x$

be any age between 12 and 65, each respondent is associated with an immigration salience at age x variable, which corresponds to the average immigration salience estimate from Politbarometer for that state in the three years when the respondent was between

![]() $ x-1$

and

$ x-1$

and

![]() $ x+1$

years of age. For instance, a 40-year-old survey respondent from Hamburg polled in 2020 will receive as a value for immigration salience at age 20 the average of estimates for immigration salience in Hamburg in 1999, 2000, and 2001. This ‘three-year window’ approach allows us to smoothen the distribution of the independent variable, as yearly salience estimates are very ‘peaky’, while our assumption is that political socialization takes place over a diffuse period of time. In any case, in part B of the Appendix, we show that we can reproduce our main results with both narrower (one-year) and broader (five-year) windows. Table 3 shows descriptive statistics for some of the key variables used in Study 2.

$ x+1$

years of age. For instance, a 40-year-old survey respondent from Hamburg polled in 2020 will receive as a value for immigration salience at age 20 the average of estimates for immigration salience in Hamburg in 1999, 2000, and 2001. This ‘three-year window’ approach allows us to smoothen the distribution of the independent variable, as yearly salience estimates are very ‘peaky’, while our assumption is that political socialization takes place over a diffuse period of time. In any case, in part B of the Appendix, we show that we can reproduce our main results with both narrower (one-year) and broader (five-year) windows. Table 3 shows descriptive statistics for some of the key variables used in Study 2.

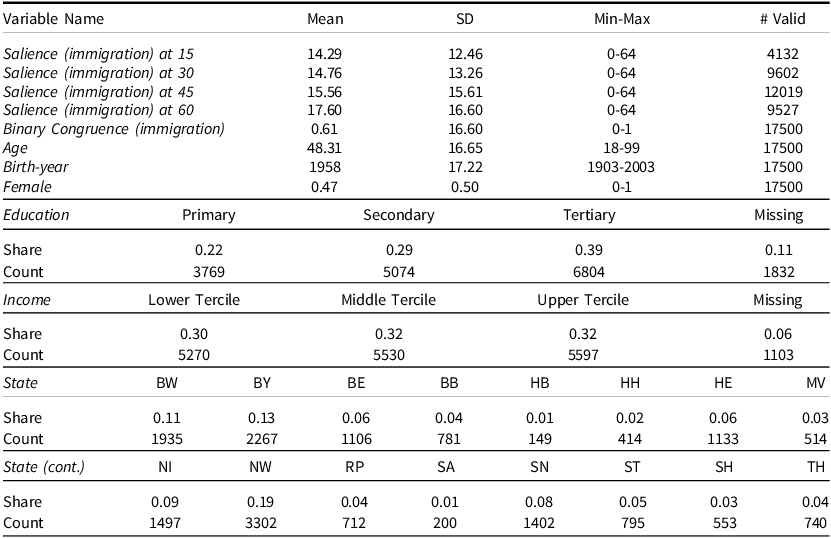

Table 3. Descriptive statistics (Study 2)

Note: Figures computed from a dataset including only observations for which the dependent variable ‘Binary Congruence immigration’ could be coded.

It is worth noting that the data we use impose some limitations on our measurement. First, because our salience estimates only go back to 1986 for West German states and to 1990 for East German states, we often have to discard a sizable chunk of older respondents in the sample, for whom immigration salience at age

![]() $ x$

cannot be computed when

$ x$

cannot be computed when

![]() $ x$

is relatively low. Secondly, the ARD data does not record the state where the respondent grew up or where she was born, so we have to make do with the state of residence as a proxy, which – while plausible for a majority of respondents – is clearly unideal.

$ x$

is relatively low. Secondly, the ARD data does not record the state where the respondent grew up or where she was born, so we have to make do with the state of residence as a proxy, which – while plausible for a majority of respondents – is clearly unideal.

We implement four logistic regression models for each independent variable (immigration salience at age

![]() $ x$

, with

$ x$

, with

![]() $ x$

comprised between 12 and 65), with binary congruence (immigration) as the dependent variable. In all cases, we control for gender, income (factor), and education (factor) and introduce federal state and survey-year fixed effects. In models (1) and (2), we control for birth year and birth year squared; in models (3) and (4), we control for age and age squared. In models (2) and (4) we further control for party (i.e., assuming exogenous partisanship). We cluster standard errors by survey year throughout.

$ x$

comprised between 12 and 65), with binary congruence (immigration) as the dependent variable. In all cases, we control for gender, income (factor), and education (factor) and introduce federal state and survey-year fixed effects. In models (1) and (2), we control for birth year and birth year squared; in models (3) and (4), we control for age and age squared. In models (2) and (4) we further control for party (i.e., assuming exogenous partisanship). We cluster standard errors by survey year throughout.

Results

Moving now to the analysis conducted on repeated cross-sectional data from Germany, Figure 5 shows the average marginal effects associated with an increase in salience of immigration when the respondent was

![]() $ x$

years of age on their probability of supporting the party they deem best to deal with immigration, for values of

$ x$

years of age on their probability of supporting the party they deem best to deal with immigration, for values of

![]() $ x$

ranging from 12 to 65. Recall that the independent variable estimate corresponds to the percentage of respondents who cite immigration as one of their top two concerns, aggregated at the state-year level, averaged over the three-year window centered in the year when the respondent was

$ x$

ranging from 12 to 65. Recall that the independent variable estimate corresponds to the percentage of respondents who cite immigration as one of their top two concerns, aggregated at the state-year level, averaged over the three-year window centered in the year when the respondent was

![]() $ x$

years old. Models 1 and 2 control for the second-order polynomial of birth year, which means that the estimates are to be interpreted in terms of the predicted variation in congruence associated with exposure to immigration salience among individuals who had otherwise similar cohort-level experiences. Models 3 and 4 swap a quadratic function of age for birth year. Finally, models 2 and 4 control for party of choice, which serves as a proxy for the assumption of exogenous partisanship.

$ x$

years old. Models 1 and 2 control for the second-order polynomial of birth year, which means that the estimates are to be interpreted in terms of the predicted variation in congruence associated with exposure to immigration salience among individuals who had otherwise similar cohort-level experiences. Models 3 and 4 swap a quadratic function of age for birth year. Finally, models 2 and 4 control for party of choice, which serves as a proxy for the assumption of exogenous partisanship.

Figure 5. Estimated average marginal effect on probability of being ‘congruent’ with their party on immigration of immigration salience when R was

![]() $ x$

years old. All models include controls for gender, income band, education, year (factor), and federal state fixed effects. Models 1 and 2 include controls for birth year and birth-year squared; models 3 and 4 include controls for age and age squared. Models 2 and 4 further control for party voted. Standard errors clustered at the survey level.

$ x$

years old. All models include controls for gender, income band, education, year (factor), and federal state fixed effects. Models 1 and 2 include controls for birth year and birth-year squared; models 3 and 4 include controls for age and age squared. Models 2 and 4 further control for party voted. Standard errors clustered at the survey level.

As shown in the figure, we find small positive effects for values of

![]() $ x$

comprised between 16 and 18 (highlighted in red). Effect estimates are consistently significant at the conventional 95% confidence level for immigration salience measured at age 17 in all four models and for ages 16 and 18 in two out of four. The point estimates for

$ x$

comprised between 16 and 18 (highlighted in red). Effect estimates are consistently significant at the conventional 95% confidence level for immigration salience measured at age 17 in all four models and for ages 16 and 18 in two out of four. The point estimates for

![]() $ x=16$

and

$ x=16$

and

![]() $ x=17$

are consistently the highest recovered.Footnote

16

Substantively, in our sample, the estimated average effect of a one-percent increase in immigration salience when the respondent was 17 is an increase in probability of being ‘congruent’ on immigration just north of one percentage point. The finding that the clearest effects are for estimates centered at 17 years of age is consistent with the finding from Study 1 that the strongest effects on immigration congruence correspond to salience of multiculturalism measured in the first election the respondent was eligible to vote in and – to a lesser extent – in the election just before. Effect magnitude is also comparable: the largest average marginal effect estimates are one order of magnitude smaller than the one recovered in Study 1, which is to be expected given that the independent variable measured from Politbarometer survey data has a standard deviation about 10 times larger than the salience scores coded from CMP data.

$ x=17$

are consistently the highest recovered.Footnote

16

Substantively, in our sample, the estimated average effect of a one-percent increase in immigration salience when the respondent was 17 is an increase in probability of being ‘congruent’ on immigration just north of one percentage point. The finding that the clearest effects are for estimates centered at 17 years of age is consistent with the finding from Study 1 that the strongest effects on immigration congruence correspond to salience of multiculturalism measured in the first election the respondent was eligible to vote in and – to a lesser extent – in the election just before. Effect magnitude is also comparable: the largest average marginal effect estimates are one order of magnitude smaller than the one recovered in Study 1, which is to be expected given that the independent variable measured from Politbarometer survey data has a standard deviation about 10 times larger than the salience scores coded from CMP data.

Finally, in part B of the Appendix, we present ancillary analysis where we further probe the robustness and assumptions of the models. First, in section B.1.1, we let the size of the ‘socialization window’ vary and find that the results are substantively similar whether we consider immigration salience context measured as the average of the three years the respondent was aged 16–18 (as in the main analysis), the five years between ages 15 and 19, or exactly in the year the respondent was 17. Second, in section B.1.2, we show that we can reproduce the main results of the analysis aggregating the salience variable at East/West rather than at the state level. Finally, in section B.2, we present the results of a series of placebo tests, where we substitute salience of immigration when the respondent was 17 with salience of other issues, and others in which we substitute voter-party congruence on immigration with congruence on other issues.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this paper combines insights from the ‘issue voting’ and ‘political socialization’ literature to develop a theory that links issue salience contexts experienced during individuals’ adolescence and voter-party congruence in the long term. We set out two mechanisms – ‘sorting’ and ‘cueing’ – through which voters may develop partisan identities and issue positions that are more tightly consistent on issues that are salient when they are in their formative years. We further argue that these identities and positions remain ‘sticky’ in adulthood, thereby affecting voter-party congruence in the long term, beyond the immediate effect of context-level issue salience on issue voting. In the empirical section, we test the implications of this theory on the specific case of the issue of immigration across a cross-country study on survey data from 10 European countries and a within-country study on repeated cross-sectional survey data from Germany. Although small, we find a noticeable effect of immigration salience during the time of socialization – measured alternatively from manifesto text data or from surveys – on voter-party congruence on immigration. The results also suggest that the phase where issue salience is most consequential for lifelong issue congruence on immigration is an individual’s late teenage years.

We acknowledge that the analysis presented may suffer from some empirical limitations. For instance, the independent variable – context-level immigration issue salience – can only be proxied by rather ‘noisy’ measures (although reassuringly we obtain results consistent with our main hypothesis with a variety of operationalizations of this variable and across different data sources). Moreover, our analysis is limited to explaining issue congruence between voters and parties, excluding non-voters from the analysis. Further research may want to theorize and investigate whether cohort differences in de-alignment (Van der Brug and Rekker Reference Van der Brug and Rekker2021; Mitteregger Reference Mitteregger2025) may also be related to socialization contexts and whether this has any bearing on our conclusions on the relationship between salience and congruence. Finally, our analysis is primarily concerned with determinants of issue congruence on the voter side (i.e., the ‘demand’ side), sidelining potential party-system-level (‘supply’ side) factors that may account for some of the cross-polity heterogeneity in issue congruence (this is more of a problem for the cross-country analysis than for the within-country analysis, as party supply can be assumed to be constant across federal states). Fully disentangling the (likely complex, con-causal) relationship between the salience of an issue, parties’ positioning on that issue, and voter-party issue congruence is beyond the scope of this analysis.

Nonetheless, we believe that this paper makes two important contributions to the literature on the issue of immigration and voting behavior. First, it complements the literature on ‘generational realignment’, which finds that immigration attitudes have become more tightly linked to left-right self-identification (De Vries et al. Reference De Vries, Hakhverdian and Lancee2013; Steiner Reference Steiner2023) and party choice (Van der Brug and Rekker Reference Van der Brug and Rekker2021; Lichtin et al. Reference Lichtin, Van Der Brug and Rekker2023; Jocker et al. Reference Jocker, Van der Brug and Rekker2025). Crucially, our work elucidates the role of salience as a key mechanism through which generational realignment may occur: immigration weighs more on the political choices and identities of more recent cohorts, at least in part because they were socialized at times of heightened debates on the issue. In this sense, this paper implicitly makes the case for moving beyond an understanding of generational realignment as a linear, structural change in patterns of political behavior across cohorts. Rather, our findings suggest that it is a phenomenon that is conditional on the evolution of political contexts in which new generations of voters learn about politics, and as such, it may be highly heterogeneous across contexts and potentially non-linear.

Secondly, our findings advance our understanding of the role of issue salience in driving electoral change. The consequences of issue salience for political behavior have been studied extensively at the individual level (how does the importance that actor

![]() $ i$

attaches to an issue affect the actor

$ i$

attaches to an issue affect the actor

![]() $ i$

’s vote choice?) and in the short term (how does the salience of an issue at a time

$ i$

’s vote choice?) and in the short term (how does the salience of an issue at a time

![]() $ t$

affect political outcomes at

$ t$

affect political outcomes at

![]() $ t$

or a proximate

$ t$

or a proximate

![]() $ t+1$

?). In contrast, our paper shows that present individual-level salience may be partly a byproduct of context-level salience in past socialization contexts.

$ t+1$

?). In contrast, our paper shows that present individual-level salience may be partly a byproduct of context-level salience in past socialization contexts.

The findings of this paper open up some avenues for further research. One potential direction would entail testing the micro-mechanisms behind the relationships uncovered, looking specifically at samples of individuals going through adolescence in different salience environment contexts. For instance, this may help understand the relative importance of sorting and cueing mechanisms in driving issue alignment.Footnote 17 Moreover, it may shed light on the role of high-profile events like elections in the socialization process and whether election timing relative to one’s age matters for the magnitude and durability of salience effects. While our findings are consistent with the argument that there is something especially ‘catalyzing’ about the circumstances of one’s first vote, they also suggest that some of these processes may start before eligibility to vote (we find some positive effects for salience in the last election prior to eligibility in Study 1 and at ages 16 and 17 in Study 2). Finally, the extent to which our hypothesis on the role of context-level salience during the time of socialization on congruence ‘travels’ to other issue domains is an open empirical question. For example, climate change has shot up the political agenda in recent decades and is starting to reshape the political behavior of younger cohorts to a substantial degree (Hoffmann et al. Reference Hoffmann, Muttarak, Peisker and Stanig2022).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1475676525100534.

Data availability statement

Replication data and files are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FU9ZD6.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Tarik Abou-Chadi, Tim Allinger, Pablo Argote, Rafaela Dancygier, Federica Genovese, Alexander Kuo, Sascha Riaz, Zeynep Somer-Topcu, the audience of the ‘Politics of Immigration’ panel at the 2023 EPOP Conference, the UCL Politics Department Seminar, the Comparative Political Economy Seminar at the University of Oxford, the Migration Politics panel at the 2024 MPSA Conference, and the Europe Workshop at Princeton University, as well as the four anonymous reviewers at the European Journal of Political Research for insightful feedback and suggestions. We also wish to extend our gratitude to Thomas Jocker and James Dennison for sharing their research material with us and to Isabelle Borucki for exceptional editorship. Francesco Raffaelli also acknowledges the support of the Einstein Stiftung (Grant Number: EVF-BUA-2022-691).