Introduction

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) is a chronic, potentially fatal spectrum of diseases caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and continues to be a serious public health challenge worldwide. Since the beginning of the epidemic, 32.0 million people have died of AIDS-related illnesses and an estimated 37.9 million people globally are living with HIV at the end of 2018 [1]. According to the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 262 442 people have died from AIDS-related illnesses from 1985 to the end of October 2018. There were approximately 849 602 people living with HIV/AIDS at the end of October 2018 in China. The prevention and control of HIV/AIDS still face a daunting challenge.

Nearly all the HIV-infected individuals exhibit a progressive depletion of CD4+T lymphocytes and imbalance in CD4+T-cell homoeostasis, the hall mark of HIV infection. HIV infections appear immunodeficiency, a manifestation of clinical symptoms, and inevitable progression to AIDS eventually. Accumulating evidence indicated that the increase of HIV plasma viral load, decrease of CD4+ lymphocyte counts and concomitant comorbidities were associated with disparities in survival whether receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) or not [Reference Nosyk2–Reference Chew and Bhattacharya4]. With the widespread use of ART, new HIV infections have declined by an estimated 16% and AIDS-related mortality has declined by 33% since 2010 [1]. However, the number of deaths due to HIV/AIDS was still high worldwide in 2018 [1]. These findings emphasise the need to investigate major determinants of HIV/AIDS survival, even though the natural disease progression of HIV infection remains elusive. Hence, it becomes extremely essential and challenging to address and explore the significant factors associated with natural course and progression to immunodeficiency among HIV infections who have not received ART.

According to the duration from HIV to AIDS, disease progression is categorised into rapid, typical and long-term non-progression in the absence of ART [Reference Wang5, Reference Salgado6]. Typical progressors (TPs) have a typical depletion of CD4+T cells and high HIV-RNA, and progression to AIDS occurs within 5–10 years of acquiring HIV. And rapid progressors (RPs) have CD4+T cell counts below 200 cells/mm3 or develop AIDS-related illnesses within 3–5 years after HIV infection [Reference Jarrin7, Reference Geng8]. However, the long-term non-progressors (LTNPs), a very small percentage of HIV-infected individuals (1–5%) remain asymptomatic, with a durable maintenance of CD4+T cell counts ⩾500 cells/mm3, low levels of viral replication and can remain healthy without significant progression for more than 10 years without ART [Reference Teixeira9]. Most of the previous studies primarily focused on the differences of disease progression between LTNPs and TPs/RPs [Reference Wang5, Reference Geng8]. However, the factors associated with TPs and RPs remain uninvestigated [Reference Jiao10, Reference Li11]. There might be some differences of natural disease progression between TPs and RPs among some factors.

Propensity score matching (PSM) was proposed by Rosenbaum and Rubin [Reference Rosenbaum and Rubin12] in 1983, as a tool to estimate and reduce the causal effects of measured confounding factors in observational studies. PSM has been widely applied in medical research, especially when a randomised controlled clinical trial is difficult to perform. In this study, we aimed at investigating the differences between TPs and RPs among HIV-infected individuals to identify the factors associated with the natural progression of HIV infection after adjusting for potential confounders by using PSM.

Methods

Study subjects

There were 13 142 HIV/AIDS patients in a high-risk area of Henan Province between 1995 and 2016. A retrospective study was conducted to assess the natural disease progression from HIV to AIDS among HIV-infected individuals in the absence of ART. HIV-positive status of all subjects was confirmed by testing positive for HIV using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and western blot analysis. HIV-infected individuals and AIDS patients were followed-up every 6 and 3 months, respectively. Seropositive individuals who had not received ART were selected. Those subjects aged less than 15 years at diagnosis were excluded from the study, as diagnostic criteria and clinical stage are inconsistent among patients less than 15 years and over 15 years.

Measurements and definition

The socio-demographic information including age at diagnosis, gender, census register, marital status, nationality, occupation, education level, disease status (HIV or AIDS), contact with HIV/AIDS patients, spouse HIV status, mode of transmission, sample sources and baseline CD4+T cell counts was recorded. The criteria of AIDS-defining in the study include CD4+T count <200 cells/mm3 after HIV infection or having at least one symptom after HIV infection such as continuous irregular fever of unknown origin over 38 °C for more than 1 month, pneumocystis pneumonia, oral candidiasis, toxoplasma encephalopathy and so on [Reference Wang5, Reference Salgado6].

All subjects were antiretroviral treatment-naïve, and AIDS-free at the time of diagnosis. HIV-infected individuals with regular follow-up were divided into two groups. TPs were HIV-infected individuals who exhibited one or more of AIDS-defining events within 5–10 years of seroconversion [Reference Wang5]. HIV-infected individuals whose CD4+T cell counts <200 cells/mm3 or exhibited AIDS-related illness within 5 years of seroconversion were defined as RPs [Reference Jarrin7].

Propensity score matching

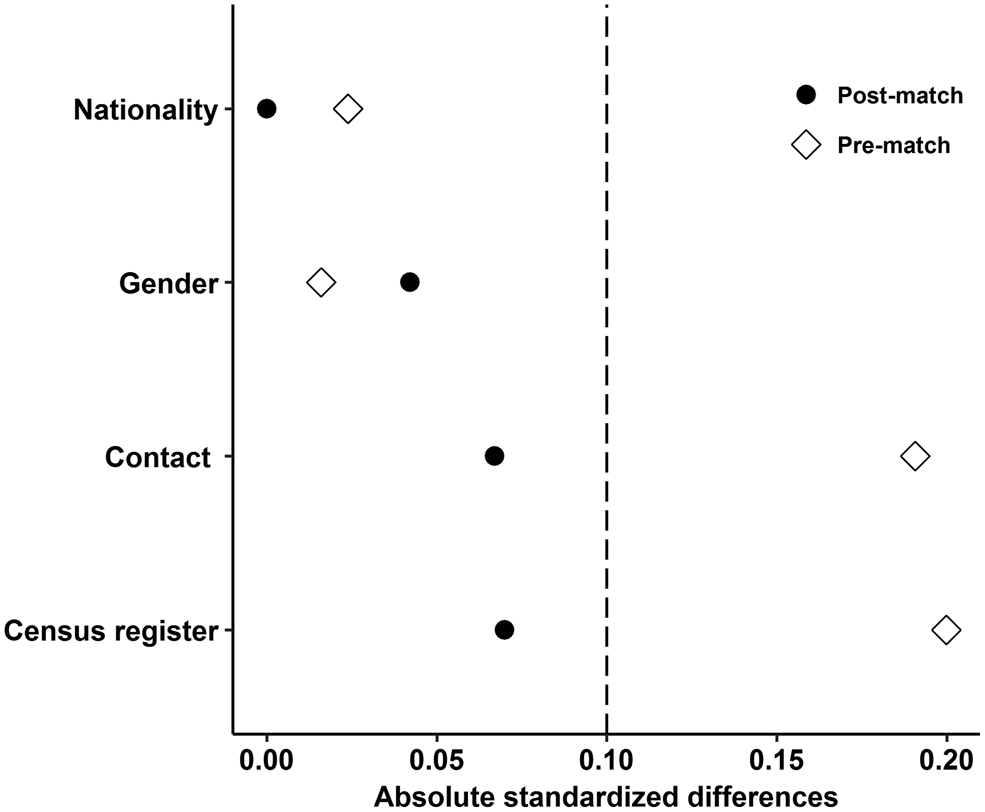

The matching factors included nationality, gender, contact with HIV/AIDS patients and census register. A logistic regression model was used to estimate the propensity score. Subjects were matched within a specified caliper 0.01 based on 1:1 nearest neighbour matching ratio, which means 20% of the standard deviation of propensity score [Reference Austin13]. Moreover, the absolute standardised difference was selected to examine the balance of all measured covariates, because it is more appropriate to assess balance in observational studies compared with the significance test [Reference Austin13–Reference Ahmed15]. After matching, all the absolute standardised differences were below 10% for all covariates indicated that these covariates exhibit no imbalances among RPs and TPs.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean (±s.d.), and categorical variables were presented as number (%). For descriptive analysis, a comparison of covariates and explanatory variables between the two groups (RPs vs. TPs) was performed using the χ 2 test or Wilcoxon rank sum test before matching. The post-match comparison was performed using the McNemar test or paired Wilcoxon-signed rank sum test. For the propensity score-matched samples, conditional logistic regression analyses were fitted to estimate the association between potential factors and the natural disease progression of HIV infection. The report of absolute standardised differences was generated using R version 3.5.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, https://www.R-project.org/). All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 22.0 software (IBM, Crop, Armonk, NY, USA). A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 2095 HIV-infected individuals (TPs: n = 379, RPs: n = 1716) meeting the eligibility criteria were included. The mean age of TPs was 38.1 (±10.1) years; the mean age of RPs was 40.5 (±9.8) years. All 379 TP HIV-infected individuals were successfully matched. Before matching, the results of covariates comparison between the two groups are shown in Table 1. After matching, absolute standardised differences for all measured covariates were below 10% indicating that these measured covariates were well balanced between TPs and RPs (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Absolute standardised differences for all measured covariates.

Table 1. The covariates comparison between RPs and TPs before PSM

Noticeably, statistically significant differences in descriptive variables including the mode of transmission of HIV, sample sources, age at diagnosis and CD4+T cell counts at baseline before and after matching was observed. Education level also differed significantly between the two groups after matching. No statistically significant differences were observed in potential predictors including occupation, marital status and spouse HIV status after matching (Table 2).

Table 2. Patient's demographic characteristics before and after PSM

VCT, voluntary counselling and testing.

a The ‘others’ included ‘no spouse’ and ‘unknown’.

Factors associated with the natural disease progression of HIV infection

Table 3 presents the results of the univariate and multivariate conditional logistic regression analyses of potential factors associated with the natural disease progression of HIV infection. Univariate analyses demonstrated that education level, mode of transmission, sample sources, age at diagnosis and baseline CD4+T cell counts were significantly associated with HIV disease progression (P < 0.05). Covariates including occupation, marital status and spouse HIV status were not significantly associated with HIV disease progression (P > 0.05).

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analyses of the factors associated with natural disease progression of HIV infections

VCT, voluntary counselling and testing; OR, odds ratio.

In the multivariate analyses, education level was no longer statistically significantly associated with HIV disease progression (P > 0.05). HIV-infectors through sexual transmission were more likely to develop AIDS compared with those infected through contaminated blood transmission (odds ratio (OR) 0.56, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.36–0.85). The HIV-infected individuals who were older at diagnosis were more likely to develop AIDS (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.58–0.89) as compared with the younger. The HIV-infected individuals identified through unique survey were less likely to develop AIDS compared with subjects diagnosed at a medical institution (OR 7.01, 95% CI 2.99–16.44). HIV-infected individuals who had higher baseline CD4+T cell counts were less likely to develop AIDS (OR 3.37, 95% CI 2.59–4.38) compared with those who had low CD4+T cells.

Discussion

In the current study, a conditional logistic regression model was applied to investigate the association between the potential factors and natural disease progression of HIV infection based on the propensity score-matched samples. The analyses revealed that the progression to AIDS was faster in HIV-infected individuals infected through sexual transmission and older ages at diagnosis. Interestingly, HIV-infected individuals who were identified through unique survey were less likely to progress to AIDS after HIV diagnosis. Besides, higher CD4+T cell counts at baseline delayed the progression to AIDS.

Nevertheless, the results of previous studies investigating the impact of mode of transmission on the progression of HIV infection were inconsistent [Reference Sabin and Lundgren16]. Yang et al. [Reference Yang17] suggested that in comparison with HIV-infected individuals infected through contaminated blood transmission, HIV-infected individuals infected through homosexual transmission had significantly lower mortality risk, while HIV-infected individuals whose transmission was through heterosexual transmission exhibited higher mortality risk. Conversely, Chen et al. [Reference Chen18] and Yan et al. [Reference Yan19] found that compared with those infected by blood transmission, HIV-infected individuals infected by homosexual transmission exhibited a significantly higher hazard ratio for progression to AIDS. In their opinions, the high rate of progressing to AIDS among homosexual patients may be due to less social and familial support, stigma, psychological characteristics and so on. In the current study, HIV-infected individuals through sexual transmission were at higher risk of developing AIDS than those through blood transmission. These findings may be attributed to the following reasons. HIV-infected individuals through sexual route exhibited higher plasma HIV load and lower CD4+T cell counts compared with those infected by blood transmission, resulting in a faster progression to AIDS among those infected by the sexual route [Reference Vlahov20]. Furthermore, HIV-infected individuals who were infected through sexual transmission may on the other hand have an increased risk of acquiring human papillomavirus, syphilis, candidiasis, herpes and genital ulcer disease [Reference Mukanyangezi21, Reference Liu22].

Consistent with previous studies [Reference Hall23, Reference Tancredi and Waldman24], older-aged subjects had a higher risk of disease progression to AIDS in our analyses. Notably in the elderly HIV-infected individuals, an ageing immune system with diminished immune function, low recovery capability and higher comorbidities have been well documented. Moreover, Phillips et al. [Reference Phillips and Pezzotti25] indicated that older HIV-infected individuals exhibited a significantly higher risk of progressing to AIDS than younger regardless of their comparable CD4+T cell counts and viral loads, which further supports the findings of the current study. Teklu et al. [Reference Teklu26] and Shrosbree et al. [Reference Shrosbree27] found that HIV-infected individuals with older age at the time of diagnosis exhibited a higher risk of late diagnosis, which maybe a cause for faster disease progression among the elderly. Therefore, an early diagnosis of HIV infection among the elderly is crucial for optimising prognosis. Taken together, older people living with HIV is markedly associated with a number of challenges including physical, clinical and immunological due to the delayed diagnosis, poor treatment outcomes and more frequent medical comorbidities. More attention should be paid to the older population infected with HIV. Besides, both older HIV-infected individuals and their care providers need to maximise prevention efforts against comorbidities and remain vigilant for early signs of illness.

The CD4+T cell count is recognised as a marker of the degree of immune deficiency in HIV-infected individuals. Notably, as expected, the results showed that HIV-infected individuals with higher CD4+T cell counts at baseline exhibited a slower disease progression in the current study. HIV primarily affects the immune system and causes a progressive depletion of CD4+T cells, and imbalance in CD4+T-cell homoeostasis, and eventually leads to immunodeficiency, a manifestation of clinical symptoms, comorbidities and inevitable progression to AIDS. Goujard et al. [Reference Goujard28] found that a lower CD4+T cell counts at baseline as a significant potential predictor of rapid progression to AIDS in untreated HIV-infected individuals. Noticeably, for specific immune responses to infection including intracellular pathogens, CD4+T cell counts have been reported to be the most significant predictor of disease progression and survival of HIV infection [Reference Muller29–Reference Zhang31]. Besides, the different thresholds of CD4+T cell counts, as a vital criterion, recommending initiation of ART in HIV-infected individuals have been proposed at different times including when the CD4+ less than 200 cells/mm3 during earlier days, 350 cells/mm3 in 2008, and 500 cells/mm3 in 2013. Nevertheless, the WHO released the second edition of the consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection in 2015, recommending lifelong ART for all HIV/AIDS patients regardless of clinical status or CD4+ cell counts to reduce AIDS-related mortality [Reference Bellino32]. Constantly, the Chinese health system follows the test-and-treat policy for ART initiation from 2016.

A pivotal strategy, especially in developing countries, is voluntary counselling and testing (VCT), which has emerged to be effective at reducing the risk of acquisition or transmission of HIV through a process involving individualised counselling, with knowledge of one's HIV status [33]. VCT could improve the detection rate of HIV/AIDS and discover new HIV infections timely. Recent studies have demonstrated that VCT could motivate people to change risky sexual behaviours related to HIV, and increase odds of using condoms and engaging in protected sex among HIV-infected individuals [Reference Coates34–Reference Cawley36]. However, in the current study no significant association between VCT and disease progression of HIV infection was observed, possibly due to the low quality of VCT services including shortage of staff, imbalanced allocation of health resources, lack of routine HIV testing and management [Reference Cawley36Reference Apanga37]. Also, we found that HIV-infected individuals identified through a unique survey had a slower progression than those diagnosed at a medical institution. This finding may be attributed to the fact that those diagnosed with HIV infection sought medical care to a hospital for other illnesses or clinical symptoms, for HIV infection. Simultaneously, HIV testing motivated by symptoms would cause a late diagnosis for HIV-infected individuals. Further results of previous studies also showed that those diagnosed at medical institutions were at higher risk of late-stage diagnosis of HIV compared with other sample sources [Reference An38]. Moreover, it is possible that the HIV-infected individuals who participated in the unique survey received early access to diagnosis, treatment and support, and HIV care.

As a tool to adjust observed confounders in observational studies, PSM may reduce study bias substantially if all potential confounders are observed and considered. However, there are inevitably some other unobserved confounders in the study. Besides, the component ratio of predictors before and after PSM may change. Just as we have observed, the proportion of mode of transmission, sample sources and age at diagnosis in this study have changed after matching, there may be selective bias.

In conclusion, the findings of the current study provide evidence of remarkable association of significant factors including mode of transmission, age at diagnosis, baseline CD4+T cell counts and sample sources with natural disease progression of HIV to AIDS between TPs and RPs in the absence of ART.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants for their contribution to the study.

Financial support

This work was supported by the National Major Science and Technology Projects of the 13th five-year plan of China (grant number 2018ZX10715009).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no financial conflict of interest.