Introduction

The international wildlife trade is a multi-billion-dollar industry, with the live pet trade representing a major component (Bush et al. Reference Bush, Baker and Macdonald2014). While the pet trade offers economic opportunities (Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, Griffiths, Fraser, Raharimalala, Roberts and St John2018), it also poses risks, depleting wild populations (Tingley et al. Reference Tingley, Harris, Hua, Wilcove and Yong2017), introducing invasive species (Reino et al. Reference Reino, Figueira, Beja, Araújo, Capinha and Strubbe2017) and endangering animal welfare (Baker et al. Reference Baker, Cain, van Kesteren, Zommers, D’Cruze and MacDonald2013). Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic grimly demonstrates the dangers posed by zoonotic disease transmission (Swift et al. Reference Swift, Hunter, Lees and Bell2007, Oxford Martin Programme 2020).

The pet trade is expected to grow with rising affluence (Challender et al. Reference Challender, Harrop and MacMillan2015) and media representation of exotic species (Nekaris et al. Reference Nekaris, Campbell, Coggins, Rode and Nijman2013), bringing additional challenges. One of these is the expansion of wildlife products onto ecommerce and social-media platforms (Sajeva et al. Reference Sajeva, Augugliaro, Smith and Oddo2013, Lavorgna Reference Lavorgna2014). Limited enforcement on mainstream websites means that trade has largely not yet shifted to anonymous networks (the ‘dark web’) (Roberts and Hernandez-Castro Reference Roberts and Hernandez-Castro2017). Therefore, the internet provides a unique opportunity to gain insights into legal and illegal wildlife trade (Vaglica et al. Reference Vaglica, Sajeva, McGough, Hutchison, Russo, Gordon, Ramarosandratana, Stuppy and Smith2017). In particular, social media can facilitate a broad range of functions and can provide both public and private spaces and communication channels (Lavorgna Reference Lavorgna2014).

Recent studies of trade on social media have investigated a broad range of taxa, including mammals (Siriwat and Nijman Reference Siriwat and Nijman2018), parrots (Martin et al. Reference Martin, Senni and D’Cruze2018) and orchids (Hinsley et al. Reference Hinsley, Lee, Harrison and Roberts2016). Although social-media posts rarely show transactions (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Cai and Mackey2020), they can provide information on species composition, welfare and hygiene standards, and trade routes. While some studies have aimed to quantify trade by identifying unique advertisements (e.g. Morgan and Chng Reference Morgan and Chng2018), there has been little consideration of the heterogeneity of ways that traders advertise and promote species, such as posts without sale-related text (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Cai and Mackey2020) or posts featuring shipments (Martin et al. Reference Martin, Senni and D’Cruze2018). Furthermore, the content and patterns of post-engagement, particularly in comments, can provide opportunities to understand the ways in which social media facilitates trade (Morgan and Chng Reference Morgan and Chng2018) and to explore trade networks but have to date received little attention.

In this study, we sought to use social-media activity to explore the current trade in West African birds. This region is of particular interest because prior to the EU ban on imports of wild-caught birds in 2005, Senegal, Mali, and Guinea were major exporters of live birds, responsible for 70% of exports in birds listed in the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) (Reino et al. Reference Reino, Figueira, Beja, Araújo, Capinha and Strubbe2017). However, 116 species that accounted for the majority of trade from these countries were removed from CITES Appendix III in 2007 (CITES 2007), meaning that CITES Parties were no longer required to report on trade in these species. Since this time, there has been little monitoring of trade in birds from the region and little is known about the current species composition, scale or direction of trade. Existing published data is outdated (e.g. Ruelle and Bruggers Reference Ruelle and Bruggers1983, Clemmons Reference Clemmons2003) and there is little monitoring of non-CITES-listed species, including frequently-traded songbirds (Passeriformes) (FAO 2011, CITES 2019). At the 18th CITES Conference of Parties, calls were made for more data on trade in songbirds, with trade in Africa highlighted as the least well understood on a continental scale (CITES 2019). The region also contains several regularly-traded bird species of conservation concern, particularly Grey and Timneh Parrots Psittacus erithacus and Psittacus timneh, both of which are listed as ‘Endangered’ on the IUCN Red List (IUCN 2020) as a result of overexploitation for the international pet trade (Birdlife 2020). With the decline in demand for birds in Europe, and the Middle East and Asia playing a larger role in driving demand for exotic pets (Bush et al. Reference Bush, Baker and Macdonald2014), research is needed to identify the risks to biodiversity and humans posed by new trade patterns.

Aiming to gain an insight into the composition, direction and implications of trade from the region, we analysed social-media posts featuring West African birds from previously known bird traders over a four-year period. We further analysed information on trade routes extracted from post images and text, and investigated spatial patterns of post-engagement in order to understand the role of social media in facilitating connections with buyers around the world.

Methods

Background and ethics

We gathered posts from an international social-media platform that was selected for its popularity and range of functions. Following on from similar studies (Hinsley et al. Reference Hinsley, Lee, Harrison and Roberts2016, Martin et al. Reference Martin, Senni and D’Cruze2018), the platform will not be explicitly named. Information was only gathered if we could reasonably assume that it was intentionally made public. Traders made posts to solicit trade and the only personal information that was analysed was location information stated clearly on the page. Identifying information was removed from the database following analysis and no de-anonymising information has been published. Finally, there was no communication with users. The study was approved by the University of Exeter’s ethics committee (eCORN002679 v3.4) and followed ethical guidance from the British Psychological Society (2017) and Kosinski et al. (Reference Kosinski, Matz, Gosling, Popov and Stillwell2015).

Study approach and sampling strategy

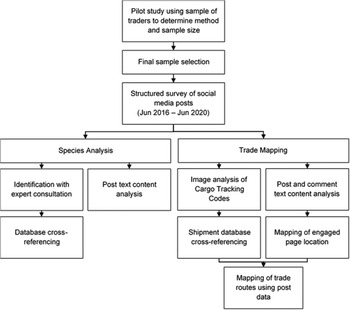

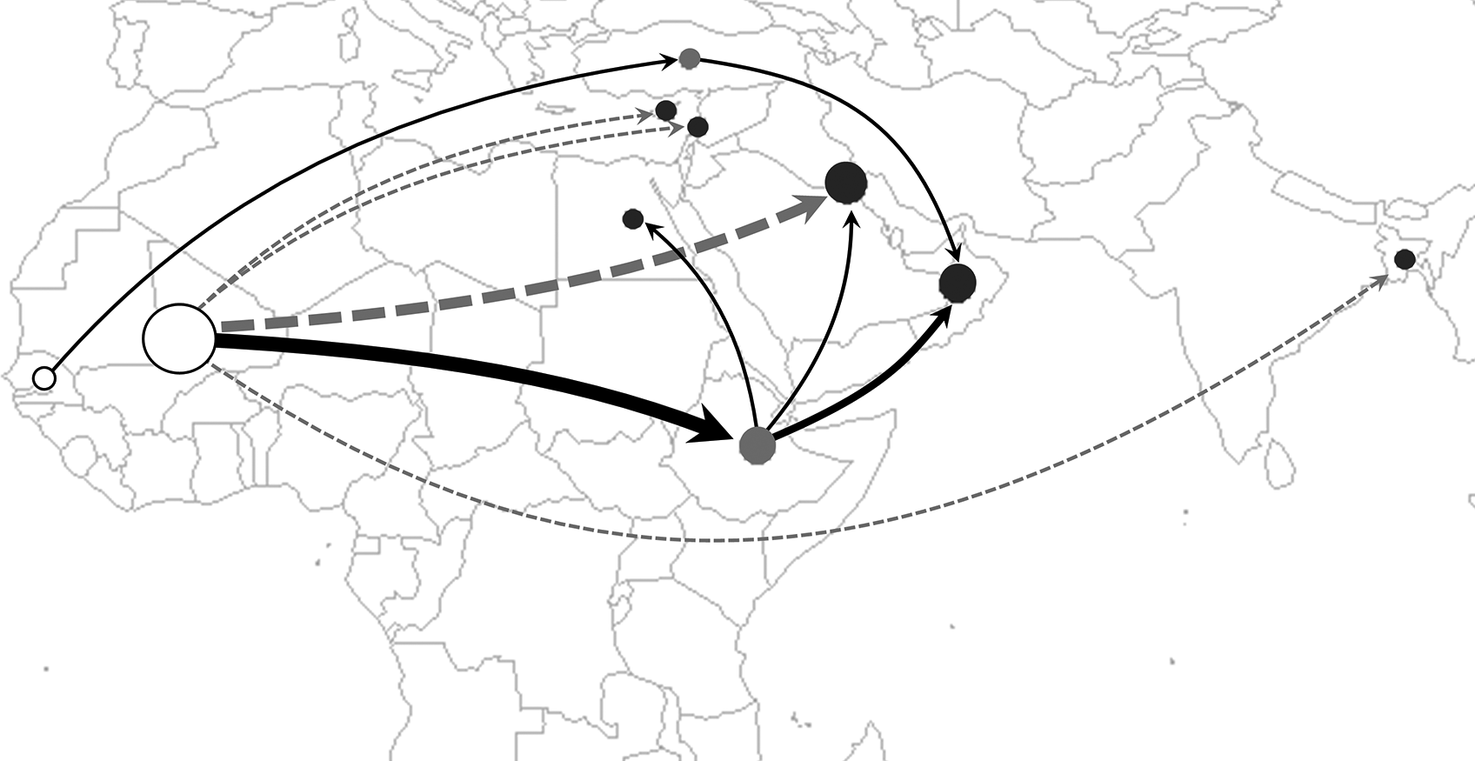

Our study approach had two key research objectives and incorporated three main analytical streams: species analysis, Cargo Tracking Code analysis, and content analysis of post and comment text, which fed into both objectives (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Diagram of study approach steps and analysis workstreams.

Following a pilot study (see Appendix S1 in the online Supplementary Material), we identified nine pages known a priori to be involved in commercial trade of birds from West African states (Guinea, Senegal, and Mali), based on intelligence from the World Parrot Trust, that had at least one post advertising trade or had comments asking about trade since June 2017. These pages were identified as ‘seed-pages’ and posts created and shared by them were named ‘S-posts’. We then gathered data on pages that were associated with S-posts by commenting, sharing, being tagged in a comment or having a post shared to their page, referred to as ‘A-pages’. In order to capture comment engagement, we also recorded any S-posts that had been shared by A-pages, which we labelled ‘A-posts’.

Data collection

We gathered data between April and June 2020, where we surveyed all relevant posts from a four-year period between 1 June 2016 and 1 June 2020. We accounted for the heterogeneity in ways traders might use posts by recording any post featuring or related to trade in West African birds, including updates to profile and cover pictures, shared posts, live videos and posts featuring generic photos copied from other sources. A detailed analysis of how multiple information sources in posts can be used to infer trade activity using this dataset is available in Davies et al. (Reference Davies, Hinsley, Nuno and Martin2021). We recorded posts shared from before the sampling period but not the original posts. Duplicate posts were recorded in order to capture comment engagement. However, to avoid duplication in species identification, all posts containing the same combination of media files (e.g. three photos containing species x and y) were identified using the same post identification code (PIC). PICs were then used as the sample unit for species identification rather than posts (further details on data collection are provided in Appendix S1).

We extracted photos, videos, post text and comments from all relevant posts and examined them to derive our key variables (Table 1). We collected comment text using an online comment-exporting service (https://exportcomments.com/). Where necessary, we translated non-English text using Google translate (https://translate.google.com/). To give an indication of private engagement, we recorded and compared the total and publicly-visible number of comments and number of times the post had been shared. All seed-pages and A-pages were given a unique random ID code and any stated location information recorded.

Table 1. Description of key variables derived from post media, text and comments, organised by research objective.

a Variables are labelled to indicate their source: I = post imagery, T = post text, P = page information, C = comments.

Species analysis

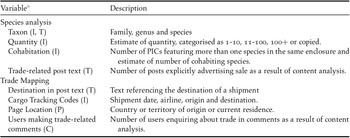

Species identification was conducted in consultation with two experts on West African birds following a percentage agreement test (Appendix S1). Where possible, the species, genus and family of visible birds was recorded. If it was not possible to identify species or genus with reasonable certainty, only the family was recorded. The number of birds for each species in each post was estimated using categories 1–10, 11–100 and 100+ (Martin et al. Reference Martin, Senni and D’Cruze2018); image quality and movement in and out of shot prohibited greater precision. This does not represent the true volume, as posts were often not independent because they showed the same images or facilities. To check if images were copied, we checked all photos using Google’s reverse-image search function. If the image existed on another site unrelated to the trader, we did not estimate quantity for the species and classified it as ‘copied’. We counted the number of PICs that featured an enclosure with more than one species in it and estimated the number of visible co-present species. To estimate the study’s adequacy in identifying the species that traders were offering, we calculated a species accumulation curve and an extrapolated species richness estimate (Colwell et al. Reference Colwell, Chao, Gotelli, Lin, Mao, Chazdon and Longino2012) using the ‘vegan’ package (v2.5-6; Oksanen et al. Reference Oksanen, Blanchet, Friendly, Kindt, Legendre, McGlinn, Minchin, O’Hara, Simpson, Solymos, Stevens, Szoecs and Wagner2019) with R version 4.0.2 (R Core Team 2020) (Appendix S1).

To explore the potential conservation and disease implications of trade in these species, we cross-referenced our list of species with those recorded in relevant databases. The global conservation status of each species was determined using the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN 2020). Potential invasion risks were assessed using the Global Invasive Species Database (GISD 2020a), which includes species that threaten native biodiversity, and the Global Avian Invasions Atlas (GAVIA), which is a comprehensive database of historical and contemporary alien introductions and populations (Dyer et al. Reference Dyer, Redding and Blackburn2017). We assessed health risks using data from the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) World Animal Health Information System (WAHIS)-Wild interface 2008–2017, as collated by Can et al. (Reference Can, D’Cruze and Macdonald2019). This database gathers incidence reports from OIE member countries regarding 54 diseases in wild animals thought to pose a potential disease risk to humans and other animals.

Trade mapping

We identified trade routes from posts featuring transport carriers and that stated a shipment’s destination. Where possible, Cargo Tracking Codes visible in imagery were used to identify the date, route and airline of shipments using a tracking database (https://www.track-trace.com/aircargo). We determined the location of users primarily using the country named in the page description or stated as the location of birth and/or residence (Di Minin et al. Reference Di Minin, Tenkanen and Toivonen2015). When the location of residence and birth differed, the location of residence was recorded because it was more recent. For seed-pages, this was cross-referenced using information from posts and comments, which led to the location being corrected for one seed-page.

Content analysis

We used content analysis to identify posts and comments where an interest in selling or buying birds was explicit. All text was independently read and categorised by two researchers (AD and AN) and any disagreements were discussed and resolved. Post-text agreement was 97.5% and comment-text agreement was 96.5%. Post text explicitly offered trade if it stated that the reader could have the bird; referred to animals being for sale, in stock or available; or referenced a price. Text referencing shipments, shops or businesses without meeting these criteria were not counted.

Comments made by seed-pages on their own posts were excluded from analysis, as were comments only containing images. A comment enquiring about trade either expressed that the individual wanted an animal; asked about price or the possibility of exporting to a country; or requested further contact with the trader. Comments only asking for the trader’s location or about other shipments without meeting other criteria were not counted. The location of all A-pages and those A-pages that made trade enquiries were mapped using the rworldmap version 1.3-6 (South Reference South2011) to investigate spatial patterns of engagement. Descriptive summaries were produced and due to high skewness, numerical data was summarised with the median and interquartile range. Species frequency was summarised as the number and percentage of PICs in which a species appeared.

Results

We identified a total of 427 relevant posts, with 221 unique post identification codes (PICs), that related to the West African bird trade, of which 341 (79.9%) were posts by trading pages (S-posts), and 86 (20.1%) were shared by other users (A-posts). There was an average of one entry per PIC (1–2, range = 1–23) and an average of 34 posts per seed-page (14.5–59, range = 2–99). Post entries were present in 44 of the 48 months of the sampling period, with an average of five S-posts per month (3–10, range = 1–46). We identified 574 A-pages, 63 of which shared A-posts. Location could be determined for 378 A-pages (65.9%). A total of 1563 comments by 515 pages were collected from 182 posts. A third of shares of S-posts (37.6%, n = 97) and a small proportion of comments (7%, n = 118) were not publicly visible, so could not be recorded.

Species analysis

We identified birds in 199 PICs (90%), whereas in other PICs birds were either not visible, a whole photo album was shared or there was no media. In 45 PICs (20.4%), at least one identification was not made at species level. Shipments appeared in 50 PICs (64 S-posts) and birds were explicitly advertised in 74 S-posts (21.7%). We recorded 721 identifications, with an average of one identification per PIC (1–4, range = 1–25). This included 26 families, 51 genera and 83 species (Appendix S2). Species could not be determined with certainty for 69 identifications, most frequently in the families Estrildidae (n = 28), Viduidae (n = 21) and Sturnidae (n = 9). Therefore, several finch, starling and whydah species may have been present but could not be accurately identified. A species accumulation curve, with a predicted total species richness of 95.4 ± 7.6 (Figure 2), suggests that the study effort was sufficient to capture around 87% of the species presented by the traders in this study.

Figure 2. Species accumulation curve with 95% confidence intervals, showing cumulative number of species identified by post identification code (n = 199).

Parrots were frequently represented, and accounted for the two most common species, namely Rose-ringed Parakeets Psittacula krameri (26.2%, n = 58) and Senegal Parrots Poicephalus senegalus (18.6%, n = 41). Furthermore, Psittacidae (n = 68) and Psittaculidae (n = 61) were the most common families. The Estrildidae family was also well represented (26.2%, n = 58), with Yellow-fronted Canaries Crithagra mozambica being the third most common species (17.2%, n = 38).

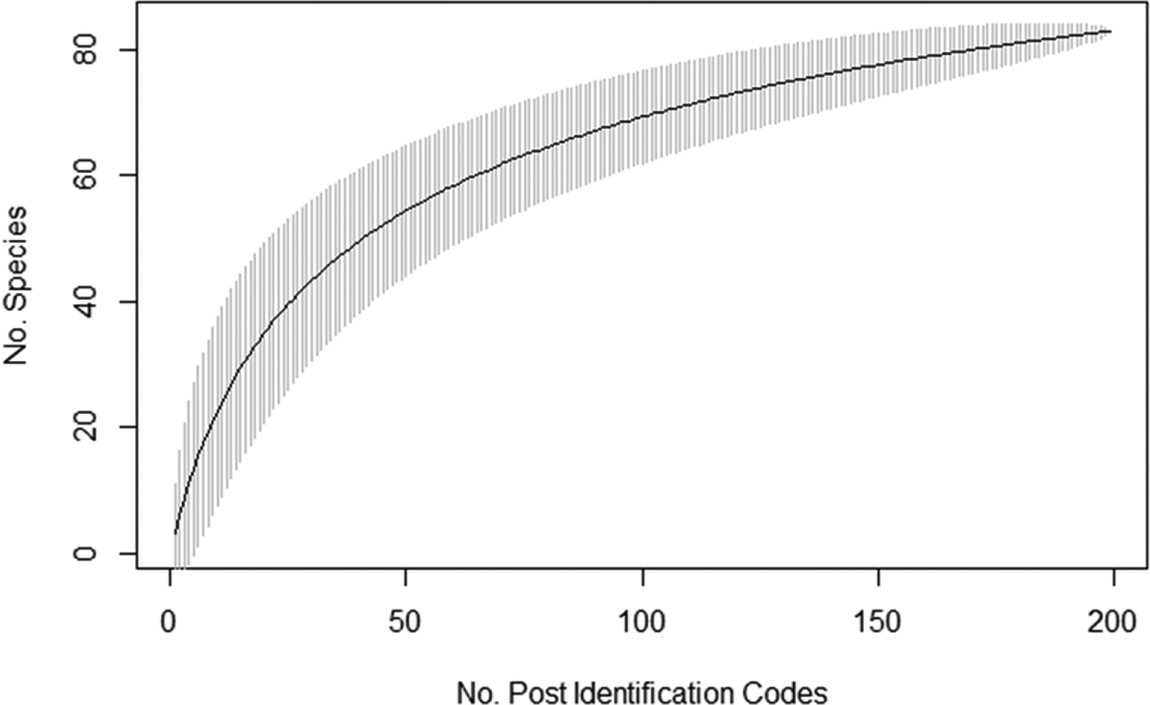

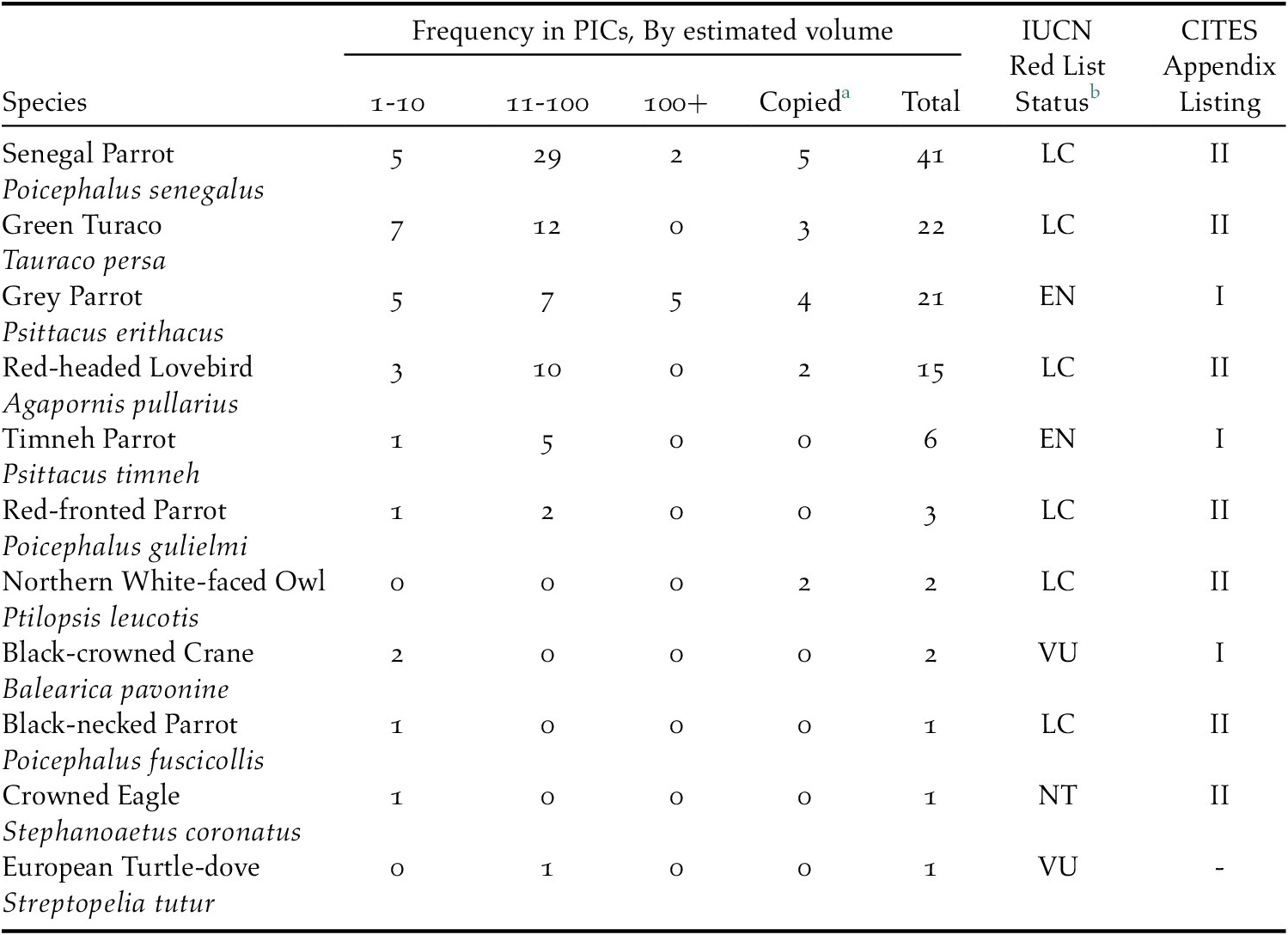

Four species are listed as Threatened on the IUCN Red List and 22 are considered to be in decline (IUCN 2020), while nine species were listed on the CITES appendices (Table 2). Three species listed on CITES Appendix I, namely Grey Parrot, Timneh Parrot and Black-crowned Crane Balearica pavonina, were shown and advertised by traders. Excluding posts created before their listing date (02/01/17), Grey Parrots were featured in eight S-posts (seven PICs), with seven S-posts explicitly offering trade, while Timneh Parrots were featured in six S-posts (four PICs), with two featuring shipments and four containing trade-related text. Black-crowned Cranes appeared in one post after their listing date (26/11/19), although this did not explicitly advertise trade.

Table 2. The frequency, estimated quantity, IUCN Red List status and CITES appendix listing for all observed Threatened or CITES-listed species.

a In estimated volume, copied indicates that the bird was represented in an image copied from another website.

b LC = Least concern, NT = Near threatened, VU = Vulnerable, EN = Endangered.

Two species were not previously listed by the IUCN as being used for ‘pet/display animals’ under ‘Use and Trade’ (IUCN 2020). These two species were the Adamawa Turtle-dove Streptopelia hypopyrrha, observed in nine S-posts (nine PICs, all 1–10 individuals) by a single trader; and the Four-banded Sandgrouse Pterocles quadricinctus, observed in six S-posts (three PICs, all between 11–100 individuals) by three seed-pages.

Of the observed species, 42 had at least one alien population or introduction recorded in the GAVIA database and in 17 species, at least one instance was attributed to the caged-bird trade. Three species, the Rock Dove Columba livia, Common Waxbill Estrilda astrild and Rose-ringed Parakeet, were also listed in the GISD.

The OIE WAHIS-Wild database recorded disease incidents in nine observed species (Appendix S1). Posts showed enclosures that were frequently stocked to high densities and contained multiple species, with 61 PICs featuring at least two co-housed species and some enclosures containing at least eight species (equivalent conditions are shown in Appendix S3).

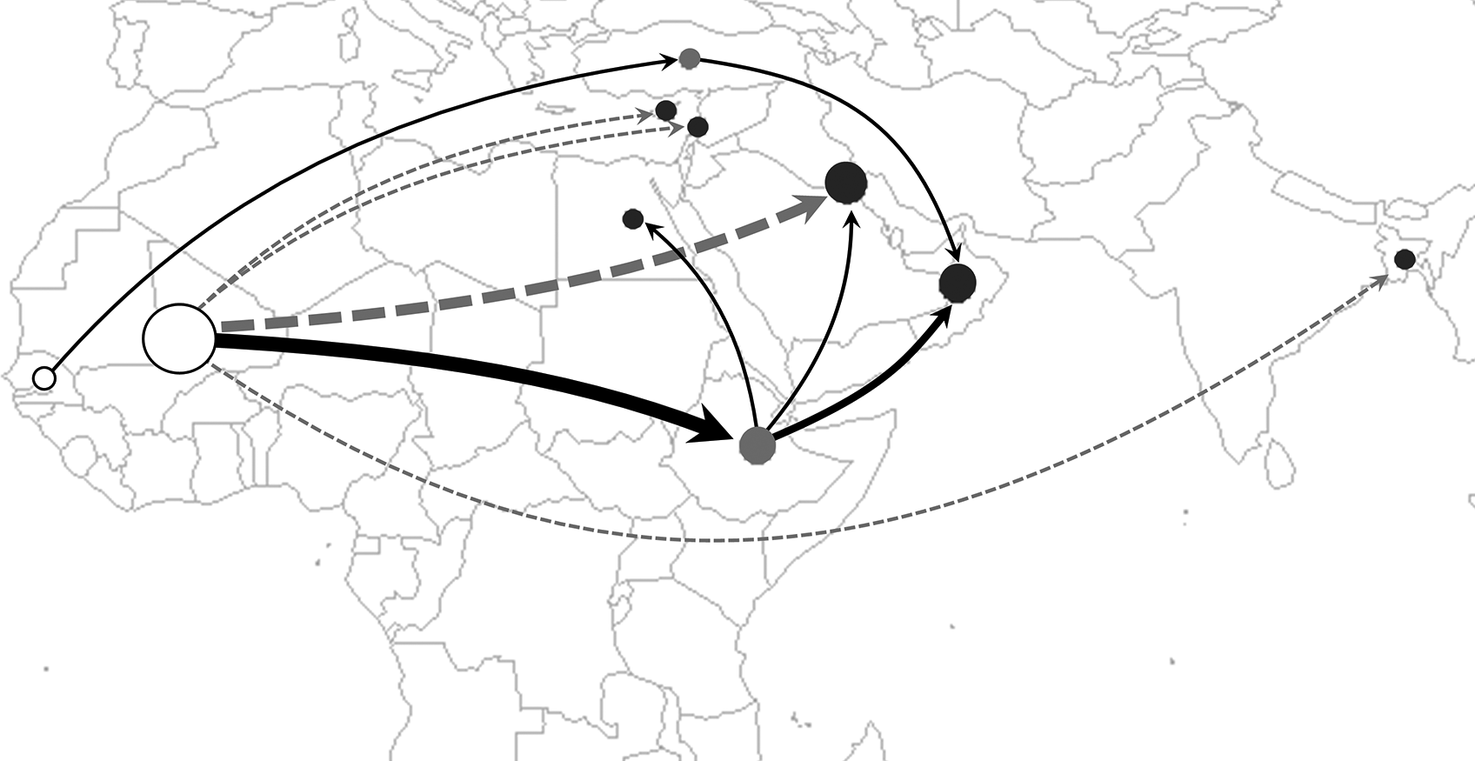

Trade route mapping

Seven S-posts from two seed-pages, both based in Mali, stated the destinations for shipments that occurred within the sampling period. Five Cargo Tracking Codes (CTCs) corresponding to verified shipments were extracted from four S-posts by three seed-pages, four exporting from Bamako, Mali via Ethiopia Airlines and one exporting from Diass, Senegal, via Turkish Airlines (Figure 3). Four shipments occurred within two months of their respective social-media posts but in one case, the post was made over a year after the shipment occurred. In one post, CTCs revealed that post text data was inaccurate, naming only one destination when the CTCs indicated two shipments. The in-text data from this post was discounted.

Figure 3. International trade routes based on information from social-media posts (n = 10). Black solid lines indicate routes validated by Cargo Tracking Codes in post images (n = 5). Grey dashed lines indicate routes described in post text (n = 6), and as such may not include transit countries. Line width is proportional to number of shipments (range 1–4). White circles indicate exporting countries, grey circles indicate transit countries and black circles indicate importing countries. Circle size is proportional to the number of routes including the country (range 1–11).

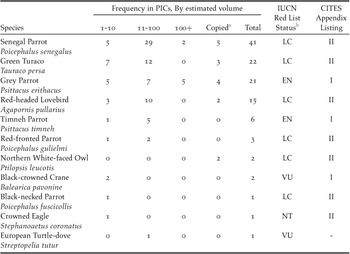

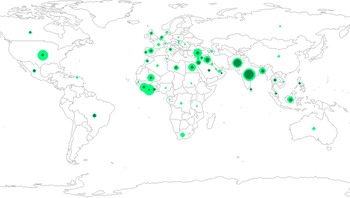

We excluded 507 comments for being made by the trader on their own post and 131 for not containing text content, leaving 925 comments for analysis. Trade enquiries occurred in 185 comments by 130 A-pages, of which location could be identified for 93 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The global location of users engaged with posts. Circles are proportional to the number of pages (range 1–43). Light circles represent all associated pages (n = 378). Dark circles represent pages that made trade-related comments (n = 93).

Discussion

Live birds have been trapped and exported from West Africa for decades but recent information on this trade is lacking. Our study revealed how social media is being used to promote trade and describes substantial international trade in a remarkable diversity of Afrotropical bird species. This trade has potential implications for conservation, animal welfare and biosecurity, with several species considered Threatened and identified as vectors of infectious diseases. Employing a novel approach to analysing post-engagement yielded insights into how social media facilitates trade connections around the world, and identified possible hotspots for trade, particularly in the Middle East and southern Asia.

The prediction of total species richness derived from the species accumulation curve suggests that our study captured a large proportion of the species promoted within our sample of traders. As we do not have a means to estimate the proportion of traders from the region represented by our sample, making inferences to the general population based on our sample must be done with caution. Nevertheless, the majority of species observed have been recorded previously in exports from the region including in trade reported to CITES (www.trade.cites.org: UNEP-WCMC 2020) and other country-specific reports - e.g. Senegal (Ruelle and Bruggers Reference Ruelle and Bruggers1983). This suggests that the trade observed in this study is broadly a continuation of practices that have taken place for at least several decades. We also identified species that have not been previously recognised as being traded for pet and exhibition purposes on the IUCN Red List, demonstrating how this approach can provide new insights into the scope of bird-trade in the region.

Implications for conservation

While most of the species that were observed are currently categorised by the IUCN as ‘Least Concern’, little is known of the status of many wild bird populations in West Africa or the impact of trade (Dendi et al. Reference Dendi, Luiselli, Fakae and Eniang2018). Several species, particularly songbirds such as the Yellow-fronted Canary, have been exported in very large quantities in the past and although we were unable to accurately quantify the volume of current trade, it was evident that large numbers continue to be captured.

Songbirds captured from the wild often have high levels of mortality in the first few days (Alves et al. Reference Alves, Lima and Araujo2012, Shepherd et al. Reference Shepherd, Sukumaran and Wich2004), therefore the birds seen in trade likely under-represent the true volume of birds captured. The potential threat posed to African songbirds by the live-bird trade is demonstrated by the population collapse of European Goldfinches Carduelis carduelis in western North Africa, where populations have declined by nearly 57% in the last 26 years (Khelifa et al. Reference Khelifa, Zebsa, Amari, Mellal, Bensouilah, Laouar and Mahdjoub2017). Concerningly, the practice of capturing Goldfinches using mist nets may also be impacting Palearctic migrants, many of which are in decline (Khelifa et al. Reference Khelifa, Zebsa, Amari, Mellal, Bensouilah, Laouar and Mahdjoub2017). In our study, we observed European Turtle-doves Streptopelia tutur, a migratory species that has declined by 98% in the UK since the 1970s (Burns et al. Reference Burns, Eaton, Balmer, Cladow, Donelan, Douse, Duigan, Foster, Frost, Grice, Hall, Hanmer, Harris, Johnstone, Lindley, McCulloch, Noble, Risely, Robinson and Wotton2020). While it is not possible to know if these European Turtle-doves were specifically targeted for trade, capture on overwintering grounds represents another threat to this imperilled species.

Several species of parrots were among the most frequently observed birds in our study. Parrots are among the most popular birds in trade, with African parrots making up three of the four most traded bird species listed on the CITES appendices between 2010 and 2014 (Martin Reference Martin2018). Recent field studies have highlighted how populations of African Grey and Timneh Parrots have undergone rapid population declines in parts of their range due to demand for trade (e.g. Annorbah Reference Annorbah2016, Hart et al. Reference Hart, Hart, Salumu, Bernard, Abani and Martin2016, Lopes et al. Reference Lopes, Martin, Henriques, Monteiro, Cardoso, Tchantchalam, Pires, Regalla and Catry2019), prompting CITES Parties to transfer them to CITES Appendix I in 2017. Concerningly, both species were observed on multiple occasions with some posts of Grey Parrots featuring over 100 specimens. However, the majority of these occurred before the species was transferred to Appendix I when legal international trade in wild-sourced specimens for commercial purposes ended; 59% of unique posts of Grey and Timneh Parrots occurred in the six-month period before the Appendix listing, with the rest occurring throughout the subsequent 3.5 years of the study. Senegal Parrots and Red-faced Lovebirds Agapornis pullarius were also frequently recorded and large volumes of exports have been reported to CITES (Martin Reference Martin2018). Studies of the status of wild populations of these species are lacking (Martin et al. Reference Martin, Perrin, Boyes, Abebe, Annorbah, Asamoah, Bizimana, Bobo, Bunbury, Brouwer, Diop, Ewnetu, Fotso, Garteh, Hall, Holbech, Madindou, Maisels, Mokoko, Mulwa, Reuleaux, Symes, Tamungang, Taylor, Valle, Waltert and Wondafrasah2014) despite being listed on CITES Appendix II, which necessitates exporting countries to determine that trade is non-detrimental to wild populations.

We also observed several large-bodied species which may be particularly susceptible to over-exploitation due to slow intrinsic rates of population growth (Ripple et al. Reference Ripple, Wolf, Newsome, Hoffmann, Wirsing and McCauley2017). Among these species were Great Blue Turacos Corythaeola cristata, which have experienced localised declines in West Africa (Annorbah Reference Annorbah2016) Black-crowned Cranes (IUCN Red List: ‘Vulnerable’), which were transferred to CITES Appendix I in 2019 (Kone et al. Reference Kone, Fofana, Beilfuss and Dodman2007) and several species of Hornbills. Raptors were notably absent with only a single Crowned Eagle Stephanoaetus coronatus observed in posts.

The potential for wild populations of many of the observed species to sustain current levels of capture is unknown and further investigation is urgently needed, particularly for frequently traded species such as Senegal Parrots. Direct field studies may provide valuable insights into the impact of trade and other threats; however, baseline data is frequently lacking and many species have large distributions, potentially making it difficult to detect localised impacts. Most trade we observed was overt and legal. Therefore, traders and trappers can be reliable sources of information on the changing status of wild populations (e.g. Hart et al. Reference Hart, Hart, Salumu, Bernard, Abani and Martin2016). Information such as price variation, availability and source localities might provide valuable insights into the sustainability of trade.

Implications for the spread of alien species

The global trade in live birds has led to the establishment of numerous naturalised populations outside their native range (Reino et al. Reference Reino, Figueira, Beja, Araújo, Capinha and Strubbe2017). These can have significant economic and environmental costs, such as competing with native species (Pimental Reference Pimentel2011). Just over half (51%) of the species observed in our study had a record of an alien introduction or population in the GAVIA database, some of which have been extraordinarily successful, and are now globally widespread. Self-sustaining populations of Rose-ringed Parakeets, for instance, have to date been recorded in over 35 countries across Europe, North America, the Middle East and Southern Africa (GISD 2020b). Concerns over the negative impacts of these populations have prompted eradication efforts but these have often proved challenging and there have been calls for greater regulation of international trade to prevent further spread (Shiels and Kalodimos Reference Shiels and Kalodimos2019). Rose-ringed Parakeets were the species most commonly observed in our study and were often featured in large numbers. Prior to their removal from the CITES appendices in 2007, Rose-ringed Parakeets were among the most frequently reported bird species in trade (Martin Reference Martin2018) and our data suggest that they continue to be captured and exported in large numbers from West Africa. The scale of this ongoing trade in wild Rose-ringed Parakeets has possibly not been fully appreciated by researchers and decision-makers due to their removal from the CITES Appendices and we strongly encourage greater scrutiny of this trade.

Infectious disease

Birds were frequently seen to be housed in conditions that could promote the development and spread of diseases. Large quantities of birds were observed at high stocking densities with multiple species housed in close proximity within the same room. One of the major recommendations for preventing disease transmission is reducing contact between species (Karesh et al. Reference Karesh, Cook, Bennett and Newcomb2005) and housing species together could also increase the risk of viral recombination (Julian et al. Reference Julian, Piasecki, Chrząstek, Walters, Muhire, Harkins, Martin and Varsani2013). The exportation of birds carrying infectious pathogens risks introducing diseases to importing countries (Swift et al. Reference Swift, Hunter, Lees and Bell2007). In 2006, a risk assessment of the health and welfare risks associated with imports of wild birds into the European Union, of which 88% came from the African continent at that time, concluded that the need to continue importation be carefully considered in light of the risks (EFSA 2006). Our study indicates that this threat persists in Asian countries that continue to import wild birds from Africa, as well as to transit countries such as Ethiopia (Siraw and Chaka Reference Siraw and Chaka2009). Multiple strains of beak and feather disease virus (BFDV) have been found in wild and captive Rose-ringed Parakeets in Senegal and the Gambia, as well as in Timneh Parrots seized from traders in Senegal (Fogell et al. Reference Fogell, Martin, Bunbury, Lawson, Sells, McKeand, Tatayah, Trung and Groombridge2018). Prior to their seizure, these parrots were held in a bird exporter’s facility in close proximity to a large number of other bird species, suggesting significant potential for disease transfer between species. Spill over of BFDV to wild populations threatens wild populations of endangered parrots (Regnard et al. Reference Regnard, Boyes, Martin, Hitzeroth and Rybicki2015).

Trade routes and engagement

Although we were only able to identify destination countries and trade routes in a limited number of instances, our findings were consistent with previous work that indicates a growing role of the Middle East and Asia in fuelling demand for exotic live animals from Africa (Bush et al. Reference Bush, Baker and Macdonald2014). Comments enquiring about trade were concentrated in a few notable hotspots. Countries in southern Asia, particularly India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, represented a large proportion of users making trade-related comments. The extent of trade-related interest suggests that significant demand for African birds may exist in India and highlights the possibility of important and potentially illegal trade routes circumventing restrictions aimed at curbing the spread of Avian Influenza. It is important to note, however, that in most cases it was not possible to verify movements of birds. Furthermore, differences in the number of trade-related comments between countries may be strongly influenced by regional differences in population, internet penetration and preferences for particular social-media platforms.

Patterns of engagement demonstrated the vast potential of social media to enable exporters of wildlife to connect with potential buyers in other countries. People in 56 countries spread across every continent engaged with posts featuring West African birds and many used social media to make initial trade-related enquiries. This lays bare the extraordinary power of social-media platforms to facilitate wildlife trade and raises questions about where responsibility rests for ensuring online trade does not exacerbate the risks the wildlife trade poses to biodiversity, people and the economy. We recommend that our findings be used to guide further research into the role of social media in trade, and the impacts of this trade on wild populations of popular and threatened species.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270921000551.

Acknowledgements

A special thanks to Nik Borrow and Benedictus Freeman for their support and assistance with bird identification. This work was supported by the University of Exeter, World Parrot Trust, and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska‐Curie grant agreement SocioEcoFrontiers (A.N., grant No. 843865).