Introduction

Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology is gaining an entry into the fields of wildlife research and monitoring (Linchant et al. Reference Linchant, Lisein, Semeki, Lejeune and Vermeulen2015, Christie et al. Reference Christie, Gilbert, Brown, Hatfield and Hanson2016, Barnas et al. Reference Barnas, Newman, Felege, Corcoran, Hervey, Stechmann, Rockwell and Ellis-Felege2017). In particular, ornithological studies have taken advantage of UAV technology (Sadrá-Palomera et al. Reference Sadrá-Palomera, Bota, Viñolo, Pallarés, Sazatornil, Brotons, Gomáriz and Sadra2012, Chabot and Bird Reference Chabot and Bird2015, Goebel et al. Reference Goebel, Perryman, Hinke, Krause, Hann, Gardner and LeRoi2015, Weissensteiner et al. Reference Weissensteiner, Poelstra and Wolf2015, Barnas et al. Reference Barnas, Newman, Felege, Corcoran, Hervey, Stechmann, Rockwell and Ellis-Felege2017, Lyons et al. Reference Lyons, Brandis, Callaghan, McCann, Mills, Ryall and Kingsford2018). The increased use of UAVs has been followed by a growing body of literature concerning the disturbance effects on avian wildlife by UAVs (Vas et al. Reference Vas, Lescroël, Duriez, Boguszewski and Grémillet2015, Christie et al. Reference Christie, Gilbert, Brown, Hatfield and Hanson2016, McEvoy et al. Reference McEvoy, Hall and McDonald2016, Barnas et al. Reference Barnas, Newman, Felege, Corcoran, Hervey, Stechmann, Rockwell and Ellis-Felege2017, Borrelle and Fletcher Reference Borrelle and Fletcher2017, Brisson-Curadeau et al. Reference Brisson-Curadeau, Bird, Burke, Fifield, Pace, Sherley and Elliott2017, Mulero-Pázmány et al. Reference Mulero-Pázmány, Jenni-Eiermann, Strebel, Sattler, Negro and Tablado2017, Lyons et al. Reference Lyons, Brandis, Callaghan, McCann, Mills, Ryall and Kingsford2018, Weimerskirch et al. Reference Weimerskirch, Prudor and Schull2018). Several of these studies have noted that the responses of birds to UAVs may vary between species (Borrelle and Fletcher Reference Borrelle and Fletcher2017, Brisson-Curadeau et al. Reference Brisson-Curadeau, Bird, Burke, Fifield, Pace, Sherley and Elliott2017, Mulero-Pázmány et al. Reference Mulero-Pázmány, Jenni-Eiermann, Strebel, Sattler, Negro and Tablado2017, Lyons et al. Reference Lyons, Brandis, Callaghan, McCann, Mills, Ryall and Kingsford2018, Weimerskirch et al. Reference Weimerskirch, Prudor and Schull2018). Thus, using an UAV for research for ornithological studies might require guidelines on UAV application specific to the species or group of species to be studied. For instance, using UAVs for counting and observing migratory waterfowl such as geese, in their roosting and foraging areas might become an effective tool for future conservation planning (e.g. establishing hunting quotas and Ramsar areas), which is often governed by international legislation and conventions such as Ramsar (Fox et al. Reference Fox, Ebbinge, Mitchell, Heinicke, Aarvak, Colhoun, Clausen, Dereliev, Faragó, Koffijberg, Kruckenberg, Loonen, Madsen, Mooij, Musil, Nilsson, Pihl and Van Der Jeugd2010) and the Bonn Convention (Horn et al. Reference Horn, de la Vega, Asmus, Schwemmer, Enners, Garthe, Binder and Asmus2017).

The aim of this study is to evaluate guidelines for UAVs as a tool for researching geese by estimating the level of disturbance to geese posed by an approaching quadcopter UAV as well as the risk of birds flushing during UAV approach. On this basis a series of recommendations are suggested to minimise disturbance when operating an UAV in the vicinity of geese, which were found relevant for minimising the risk of birds flushing as well as for improving the ethical treatment of such species during research.

Materials and methods

Species investigated

Twenty-four flocks of wild geese were approached by an UAV (DJI Phantom 4 Pro) to evaluate the risk of flocks flushing at various distances between the UAV and the flock as well as to evaluate the degree of disturbance caused by the UAV. Each UAV flight was controlled manually using the DJI GO 4 Drone application (Version 4.0.6). Initially, the UAV flying altitude was set to 50 m (Table 1). However, to accommodate the nervous behaviour of the birds the flight altitude was later set to 100 m. The flocks studied were found on agricultural fields in Northern Jutland, Denmark, from 7 March to 6 April 2017 (Table 1) and consisted of the following species: Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis, Pink-footed Goose Anser brachyrhynchus, Greylag Goose Anser anser, Canada Goose Branta canadensis and Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons.

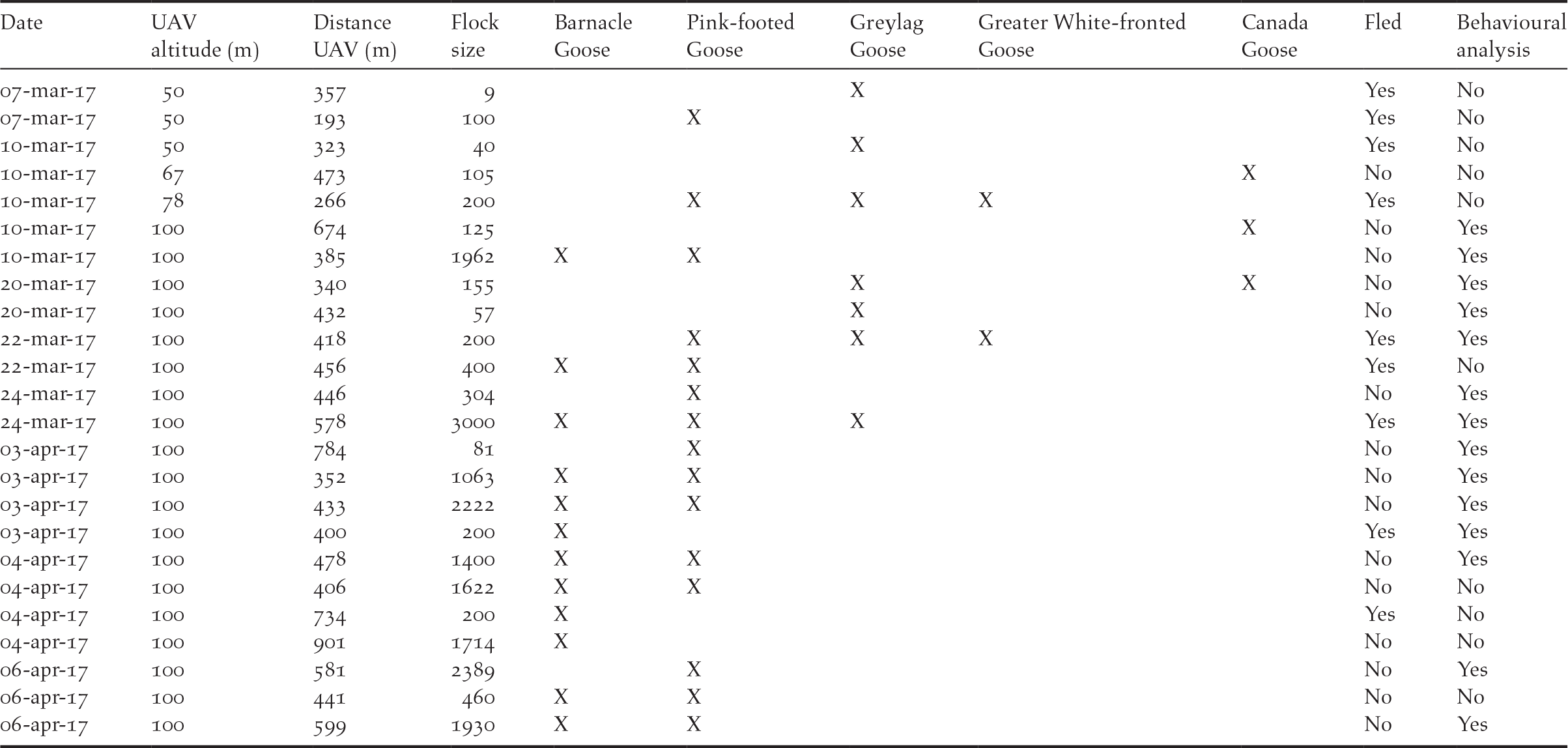

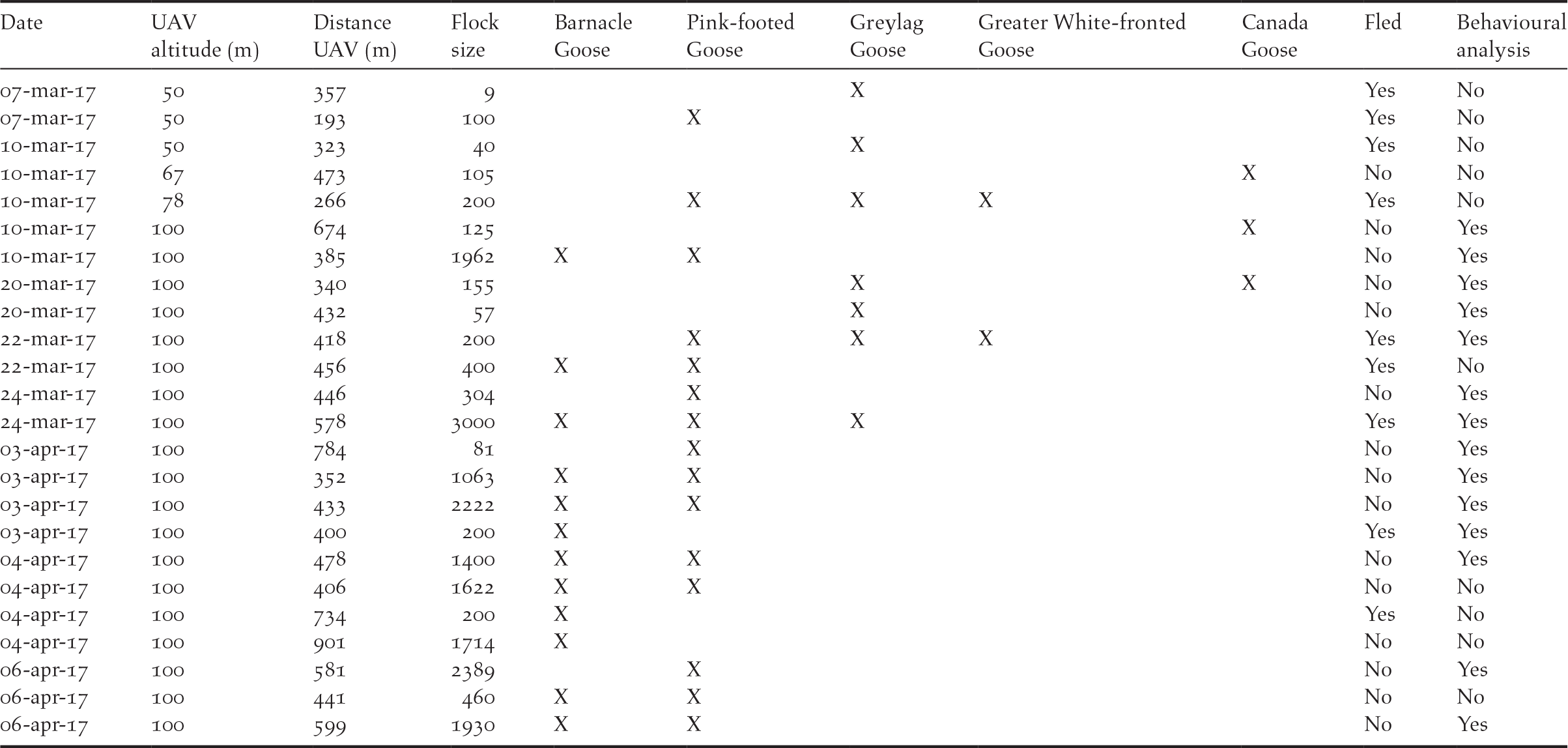

Table 1. Twenty-four studied flocks including following information: Dates for data collection, flight altitude (m), distance (m) from UAV take-off to the flocks, flock size counted on UAV recordings or estimated by observers from the ground, indication (X) of different species, unsuccessful overflight (indicated with ‘Yes’ and ‘No’), and flocks included in behavioural analysis (indicated with ‘Yes’ and ‘No’).

Estimation of UAV-caused disturbance

The disturbance effects of UAVs on geese were evaluated by estimating the percentage of individuals in a flock showing vigilant behaviour (scanning for predators or flying away) both prior to the UAV flight as well as during UAV overflight at various distances between the UAV and the flock. Percentage of vigilant behaviour will be referred to as disturbance level. The behaviour of the birds was monitored through video recordings of each flock using a telescope mounted with a video camera from an observer positioned on the ground. The video camera was pointed at a representative part of the flock, including as many birds as possible (tens to hundreds of individuals).

Two video recordings were made of each flock. The first video was recorded prior to UAV flight to estimate the unaffected behaviour of the birds (control recording). The second video was recorded during the UAV overflight and was used to estimate the birds’ response to the approaching UAV (response recording). The length of each control recording was set to 10 minutes while the length of response recordings was not specified due to difference in UAV approach distances between flocks.

Responses to the approaching UAV were estimated from control- and response recordings from 14 of the 24 studied flocks (Table 1). The data for the remaining 10 flocks were excluded due to insufficient video quality to estimate behaviour or due to flying altitudes being below 100 m as a means of reducing variables which might affect disturbance levels. From the 14 flocks two datasets were made: ‘Pink-footed Geese’ (n = 3), and ‘combined flocks’ (all studied species n = 14). Analysed behaviour was categorised into non-vigilant behaviour (e.g. resting, pruning feathers and foraging) and vigilant behaviour (scanning for predators and flying away).

For estimation of disturbance level prior to UAV overflight, behaviour was evaluated from 10 still frames derived from each control recording. Thus, a total of 30 still frames were analysed for specific behaviour for flocks containing Pink-footed Geese and 140 still frames for combined flocks. The still frames were randomly selected by using Research Randomizer (Version 4.0) (Urbaniak and Plous Reference Urbaniak and Plous2015).

The estimation of disturbance level during UAV overflight was likewise based on specific behaviour evaluated from randomly selected still frames derived from the response recordings. Each response recording varied in length as a result of differences in the UAV approach distance. To ensure an even representation of every recording, the number of still frames per recording was standardised by dividing recording length (in seconds) by 15 seconds. A maximum of 10 random still frames were selected per response recording. The analysed time interval of the response recordings started at UAV take-off and ended at the point in time when the UAV reached the edge of the flock. In cases where the bird flock fled, an additional still frame was added at the point of flight, as this was considered to be a disturbance level of 100%. Thus, from the response recordings a total of 25 still frames were analysed for specific behaviour for flocks of pink-footed geese and 121 still frames for combined flocks.

To investigate the potential correlation between bird vigilance and distance between the UAV and the edge of the flock (UAV-to-flock distance), each analysed response frame was assigned a horizontal UAV-to-flock distance. UAV-to-flock distances was measured in QGIS (Version 2.18.4) using the plugin NNJoin (Version 1.3.1) by projecting the flock’s geographic location and the UAV flight path (retrieved from the DJI GO 4 Drone application, containing both time and GPS coordinates) into QGIS. The geographic location of each flock was manually digitized in QGIS (Version 2.18.4) based on the aerial images obtained by the UAV, by manually pointing out each individual bird. Images were projected into QGIS using the geo-referencing plugin GDAL (Version 3.1.9) in the form of large mosaics created using GNU Image Manipulation Program (GIMP) (Version 2.8.20) with at least four recognisable landmarks (road signs, trees, ditches, etc.) used as geo-referencing points. Distortion effects from the camera lens was not accounted for in this study as in QGIS they were observed to cause only a couple of meters uncertainty, thus of minor influence on the analysis. In the case of the flocks fleeing before UAV-images could be obtained, the geographic location of each flock was additionally monitored prior to UAV take-off by measuring distance and angle (degrees from north) to 40 randomly selected geese within each flock using a pair of range finding binoculars (VECTOR 21) from a known GPS location (obtained using a mobile application ‘Handy GPS’). Rangefinder GPS locations of the flocks were then acquired through trigonometric calculations using the measured degrees, distances and the observer positions.

The relationship between bird vigilance and distance between the UAV and the flock was examined by plotting disturbance levels (estimated proportion of vigilant behaviour) as a function of UAV-to-flock distances (horizontal distance from the approaching UAV to the flock edge). To determine at what point the geese showed significant increased vigilant behaviour as a response to the approaching UAV, average disturbance level and average distance was plotted with 95% confidence at intervals of 100 m for combined flocks, while using distance intervals of 200 m for flocks of Pink-footed Geese due to fewer data points. Unaffected behaviour was shown for each plot as a baseline of mean disturbance level based on the control recordings.

Estimation of flushing risk

The risk of birds fleeing as a response to the approaching UAV was investigated by calculating the percentage of UAV overflights successfully capturing aerial images of foraging bird flocks (defined as successful overflights). The risk was calculated across all the studied flocks (n = 24), for overflights performed at altitudes below 100 m (n = 5), and for overflights performed at 100 m (n = 19). Additionally, the distance between the flock edge and UAV take-off point was investigated as a possible factor influencing success rate by comparing take-off distances for successful and for non-successful overflights.

Results

Estimation of flushing risk

Among all attempted overflights (n = 24) at altitudes of 50–100 m, 15 overflights successfully captured aerial images of geese on the ground (Table 1), resulting in an overall success rate of 63%. The success rate for UAV overflights at an altitude of 100 m (n = 19) was 74%, while the success rate for overflights at altitudes less than 100 m (n = 5) was 20%. The take-off distances for successful flocks was in general higher (n = 15, mean = 515 m, range= 340–901 m) compared to unsuccessful overflights (n = 9, mean = 414 m, range = 266–734 m).

Estimation of UAV-caused disturbance

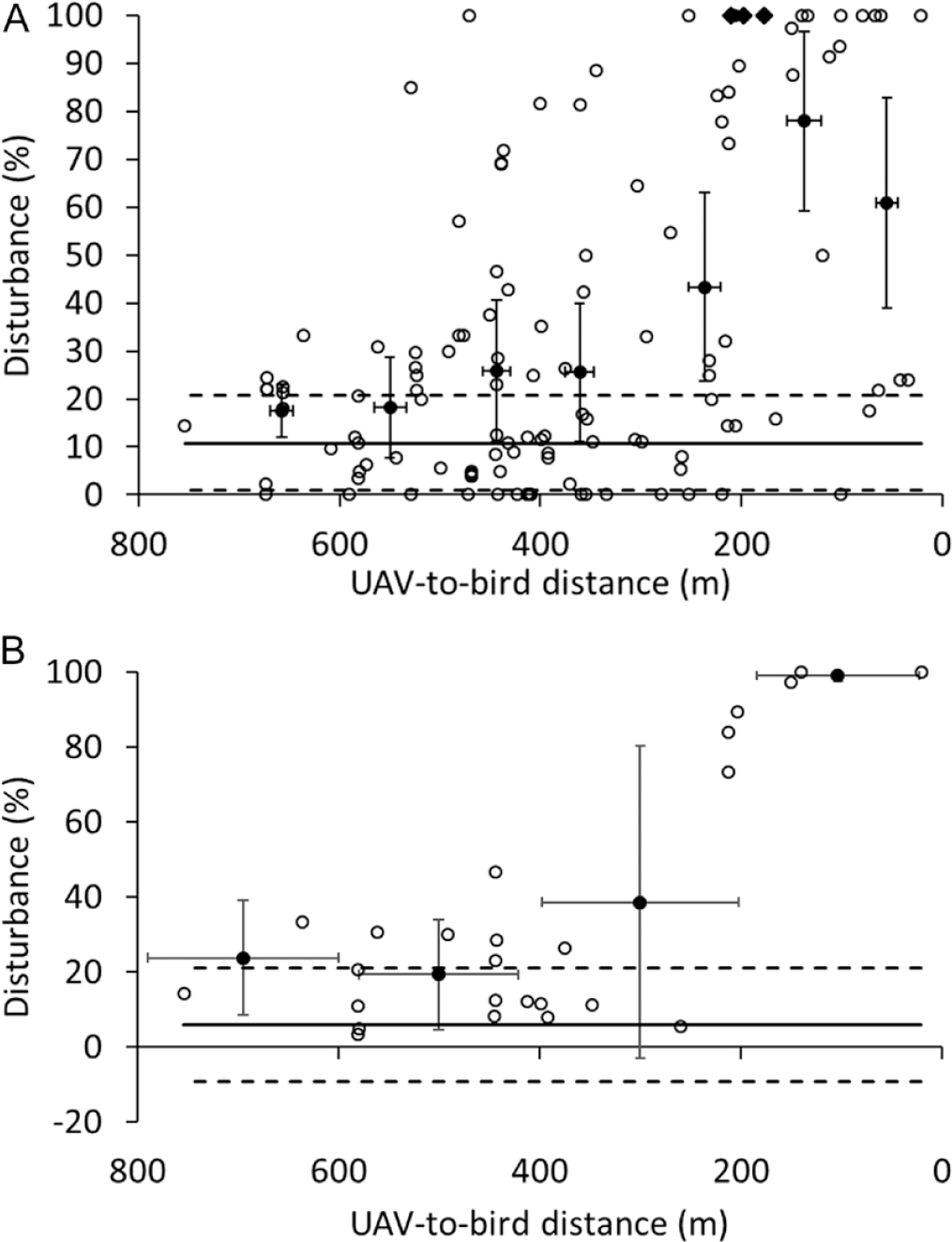

The approaching UAV was observed to have a disturbing effect on flocks of geese (n = 14), which increased with decreasing UAV-to-flock distance (Figure 1A and 1B). The disturbance levels during UAV approach significantly increased compared to mean control behaviour within UAV-to-flock distances of approximately 200 m for flocks of Pink-footed Geese (Figure 1B) and 300 m for combined flocks (Figure 1A). However, a greater dispersion of disturbance levels at various UAV-to-flock distances is observed for combined flocks (Figure 1A and 1B).

Figure 1. Disturbance level of combined flocks (A) and flocks of Pink-footed Geese (B), described as percentage of birds scanning for predators (empty circles) and whole flocks flushing (filled diamonds) as a function of the distance between the UAV and the flocks. Mean disturbance level (solid circles) with 95% confidence interval are represented at intervals of 100 m for combined flocks (A) and 200 m intervals for flocks of Pink-footed Geese (B). Mean disturbance level based on the control recordings (thick line) are shown with 95% confidence interval (dashed lines). Mean disturbance level in control recordings for combined flocks (A) and flocks of pink-footed geese (B) is 10.8% and 5.9%, respectively.

Discussion

Our study indicates that geese on land are more vigilant compared to other waterfowl resting on water when approached by UAVs, such as Mallard Anas platyrhynchos, Common Greenshank Tringa nebularia and Greater Flamingo Phoenicopterus roseus approached at 30 m altitude (Vas et al. Reference Vas, Lescroël, Duriez, Boguszewski and Grémillet2015) as well as several waterfowl and passerines approached at altitudes of 15 m and 50 m (McEvoy et al. Reference McEvoy, Hall and McDonald2016). Thus, whereas Vas et al. (Reference Vas, Lescroël, Duriez, Boguszewski and Grémillet2015) suggests a minimum take-off distance for UAVs of 100 m from flocks of birds, we recommend a take-off distance of ∼500 m when studying geese in a terrestrial setting.

A greater dispersion of disturbance levels was observed in the behavioural analysis across the range of UAV-to-flock distances for combined flocks (Figure 1A) compared to flocks of Pink-footed Geese, which might indicate that different species react differently to disturbances caused by UAVs. This is also in line with a study by Weimerskirch et al. (Reference Weimerskirch, Prudor and Schull2018), who noted that different species reacted differently to UAV disturbance. Thus, when using UAVs to study geese it might be advantageous to consider the sensitivity of the species.

Low flight altitudes were observed to decrease the success rate considerably, which is consistent with Weimerskirch et al. (Reference Weimerskirch, Prudor and Schull2018), who also observed that all studied species became increasingly disturbed with decreasing UAV overflight altitudes. We recommend overflight altitudes of 100 m when studying geese. It should be noted that legal permission might be needed in some countries to achieve the recommended flight altitude and take-off distances presented in this study, as drone legislation in most countries sets restrictions on flight altitudes as well as prohibits the use of UAVs outside visual lines of sight of the operator (Stöcker et al. Reference Stöcker, Bennett, Nex, Gerke and Zevenbergen2017).

Behaviour was evaluated as dichotomous data (vigilant vs non-vigilant) as this was considered sufficient while also being time efficient. However, for further studies disturbance could be quantified in greater detail by categorising behaviour into multiple variables with a different degree of vigilance, e.g. fleeing individuals being more disturbed than individuals scanning for predators. Additionally, it might be interesting for future studies to take several factors known to affect the vigilance of birds into account, including flock size (Beauchamp Reference Beauchamp2008), species composition (Kristiansen et al. Reference Kristiansen, Fox, Boyd and Stroud2000, Randler Reference Randler2004), and season (Lazarus and Inglis Reference Lazarus and Inglis1978).

In conclusion, both take-off distances closer to the flocks as well a low flying altitude were observed to increase the risk of birds flushing. Thus, to minimise the risk of geese flushing and improve the ethical treatment during research, we recommend a take-off distance of ∼500 m and a flying altitude of 100 m when studying geese in a terrestrial setting. Additionally, we recommend taking species into account when planning UAV flights.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Aalborg Zoo Conservation Foundation (AZCF), (grant number 02/16 and 01/17). Finally, we thank the Associate Editor and two anonymous reviewers for invaluable suggestions and help in improving the manuscript.