“I don’t know if it’s a curse or a gift sometimes [that I didn’t inherit my mom’s darker skin coloring]. You know? But my other brother—we have different dads—he like, ‘You light-skinned. That’s why the White people love you. You have the Caucasian persuasion!’ [laughs]” –48-year-old, light-skinned Black male interview participant (Yadon Reference Yadon2025)

A rich literature across the social sciences has examined struggles for political power based on group cleavages. One of the most defining cleavages in American politics is race (Blumer Reference Blumer1958; DuBois Reference DuBois1903). Categorical race is consistently and strongly associated with political attitudes, group attachment, political participation, and access to resources and opportunities (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2003; Gause Reference Gause2022; Gillion Reference Gillion2013; Kinder and Sanders Reference Kinder and Sanders1996; Lajevardi Reference Lajevardi2020; Lee Reference Lee2008; Leslie Reference Leslie2022; Perez Reference Perez2015). In addition to categorical race, the lightness or darkness of one’s skin tone is also consequential. The preference for lighter skin, known as colorism, is intertwined with racism to maintain a racial hierarchy, whereby Whiteness/lightness is the “ideal” (Banks Reference Banks1999; Brown and Lemi Reference Brown and Lemi2021; Burch Reference Burch2015; Davis Reference Davis1991; Dhillon-Jamerson Reference Dhillon-Jamerson2018; Fanon Reference Fanon1952). In contrast, darker skin signals one’s proximity to Blackness and is often associated with institutional gatekeeping and discrimination. For example, darker-skinned Black people have less wealth, lower wages, higher unemployment, less education, lower occupational prestige, greater social rejection, worse health outcomes, and worse outcomes in the criminal justice system than lighter-skinned Black people, on average (Burch Reference Burch2015; Eberhardt et al. Reference Eberhardt, Davies, Purdie-Vaughns and Johnson2006; Goldsmith et al. Reference Goldsmith, Hamilton and Darity2007; Hebl et al. Reference Hebl, Williams, Sundermann, Kell and Davies2012; Keith and Herring Reference Keith and Herring1991; Monk Reference Monk2021). Many of these patterns date back centuries, with the contemporary magnitude of these color-based disparities often being equal to or larger than that of race-based disparities (Monk Reference Monk2021).

This association between race, color, and systemic outcomes signals that White people recognize finer-grained color-based differences between out-group members. Indeed, White people historically created and continue to reify associations between skin color and perceived value (Ostfeld and Yadon 2022). Moreover, colorism persists despite evidence that overt discrimination and explicit racism have decreased over time (Hebl et al. Reference Hebl, Williams, Sundermann, Kell and Davies2012; Monk Reference Monk2021). Yet, the literature on White racial attitudes largely theorizes that out-groups are perceived homogeneously (e.g., Kinder and Sanders Reference Kinder and Sanders1996). Given evidence that skin color may be increasingly salient politically alongside the growing share of non-White political candidates (Lemi Reference Lemi2020; Ostfeld and Yadon 2022; Yadon Reference Yadon2025), it is worthwhile to re-examine these assumptions of out-group racial homogeneity. More deeply theorizing how the multidimensionality of race operates in society complements the growing literature of nuanced racialized experiences (Burch Reference Burch2015; Eberhardt et al. Reference Eberhardt, Davies, Purdie-Vaughns and Johnson2006; Leslie Reference Leslie2022; Masuoka Reference Masuoka2011).

Consistent with this, I explore when, where, and how skin color matters for Whites’ evaluations of Black male and Black female political candidates. Drawing from group position theory, I argue that Whites’ more negative reactions to darker-skinned Black people are rooted in concerns about maintaining the dominant status and privileges associated with Whiteness (Bobo and Hutchings Reference Bobo and Hutchings1996; Jardina Reference Jardina2019). Because darker skin is more prototypical and signals closer proximity to Blackness, it can also signal racial group attachment and potentially serve as a stronger signal of threats to Whites’ power. In the realm of political candidates, then, lighter-skinned Black candidates may be perceived as more similar to Whites and less threatening to Whites’ dominant status. This is consistent with existing evidence that Whites’ evaluations of light-skinned Black political candidates and White candidates are largely indistinguishable (Lerman et al. Reference Lerman, McCabe and Sadin2015; Terkildsen Reference Terkildsen1993; Weaver Reference Weaver2012).

Given the gendered nature of racialization and colorism (Hunter Reference Hunter2002; Lemi and Brown Reference Lemi and Brown2020), it is likely that Black women candidates will be perceived in different ways from their Black male counterparts even when they share a similar complexion. Recent work highlights that Black women face unique obstacles compared to Black men in terms of perceptions, stereotypes, and more (Brown Reference Brown2014; Brown and Lemi Reference Brown and Lemi2021; Yadon Reference Yadon2025). Indeed, light-skinned Black women, dark-skinned Black women, light-skinned Black men, and dark-skinned Black men are likely to confront distinct stereotypes and types of discrimination, even as there are some stereotypes more generally applied to Black men, Black women, light-skinned Black people, and dark-skinned Black people. It is plausible that female candidates will be viewed distinctly from male candidates even when they share a similar skin tone, then. I present competing expectations for whether darker-skinned Black female candidates may be rewarded or punished by White voters on account of race-based and color-based intersectionality. Thus, an important contribution of this project is expanding the literature on race, skin tone, and candidate evaluations to extend the primary focus from male candidates by incorporating Black women candidates in my second survey experiment.

To test these expectations, I rely on two survey experiments with White Americans to examine how colorism operates in terms of candidate evaluations of both male and female Black political candidates.Footnote 1 Using technological advancements to realistically alter skin tone for both studies, I isolate the influence of skin tone when other characteristics are held constant (e.g., features and hair). In short, I find that White voters do view Black candidates differently based on both the candidate’s skin tone and the candidate’s gender. White identity and partisanship are both found to play meaningful but nuanced roles in how candidates are perceived. This project contributes to the scholarly literatures on prejudice, hierarchy, and electoral politics as more people of color—and women of color, specifically—are running for political office (Lemi Reference Lemi2020; Leslie et al. Reference Leslie, Masuoka, Gaither, Remedios and Chyei Vinluan2022). Specifically, the findings underscore the importance of theorizing about and measuring race as a multidimensional construct given that the intersections of race, skin tone, and gender shape electoral opportunities.

Theoretical Framework

Given the historical legacy of varied perceptions and treatment of Black people based on skin tone (Monk Reference Monk2021), color-based differentiations are likely to continue to manifest in electoral politics. How this might operate depends on a number of factors, including the candidate’s gender and the voter’s characteristics. Consequently, I build from the handful of studies finding evidence of how race and color influence White voters’ evaluations of Black male political candidates (Lerman et al. Reference Lerman, McCabe and Sadin2015; Terkildsen Reference Terkildsen1993; Weaver Reference Weaver2012) to develop a framework anticipating when and how skin color and gender may work in tandem to influence Whites’ political attitudes. I discuss how the combination of race, gender, and skin tone may differentially influence perceptions of a candidate, and how these characteristics may change in impact depending on context.

Skin Tone and Candidate Evaluations

A growing body of research examines how Black candidates are perceived by voters, though much less focus has been paid to skin tone specifically (e.g., Bonilla, Filindra, and Lajevardi Reference Bonilla, Filindra and Lajevardi2022; Karpowitz et al. Reference Karpowitz, King-Meadows, Monson and Pope2021; Leslie, Stout, and Tolbert Reference Leslie, Stout and Tolbert2019; Stephens-Dougan Reference Stephens-Dougan2020; Stout Reference Stout2015). I argue that White voters may respond more positively to Black candidates with lighter skin than those with darker skin for two primary reasons. First, people are more comfortable with those who look more like themselves. Indeed, people are generally interested in and prefer those who are similar to them in terms of appearance, attitudes, or other attributes (Davis Reference Davis1991; Finkel and Baumeister Reference Finkel and Baumeister2019; Zajonc Reference Zajonc1980). Assessing faces is a primary means by which people determine similarity, affect, and attitudes toward others (Bailenson et al. Reference Bailenson, Iyengar, Yee and Collins2008; Zajonc Reference Zajonc1980). Political messaging that elicits emotional responses through facial cues, images, or music increases attentiveness to campaigns and shapes perceptions of candidates (Brader Reference Brader2006). For political candidates, facial similarity serves as a significant cue beyond partisanship when a viewer is unfamiliar with a candidate (Bailenson et al. Reference Bailenson, Iyengar, Yee and Collins2008).

Thus, non-verbal cues like appearance influence perceptions of candidates. A candidate’s skin tone may be an especially powerful cue because skin color often operates in more subconscious ways than race (Blair et al. Reference Blair, Judd and Chapleau2004; Weaver Reference Weaver2012). While there are norms of political correctness surrounding race, skin tone largely lacks similar norms despite its powerful association with life outcomes (Blair et al. Reference Blair, Judd and Chapleau2004; Monk Reference Monk2021). As summarized by political scientist Vesla Weaver (Reference Weaver2012, p.166), “Unconscious bias around skin color is not governed by conscious norms of equality, and therefore, not subject to control.” Because the appearance of White and lighter-skinned Black people is more similar (Davis Reference Davis1991; Graham Reference Graham1999), Whites will likely view lighter-skinned Black candidates more positively than darker-skinned candidates.

Accordingly, a handful of published studies have explored the relationship between skin tone and candidate evaluations across voters of different ethnoracial backgrounds (Burge, Wamble, and Cuomo Reference Burge, Wamble and Cuomo2020; Lemi and Brown Reference Lemi and Brown2019; Lerman, McCabe, and Sadin Reference Lerman, McCabe and Sadin2015; Orey and Zhang Reference Orey and Zhang2019). Evidence from the more limited set exploring White voters signals that skin tone does influence Whites’ candidate evaluations (Lerman et al. Reference Lerman, McCabe and Sadin2015; Terkildsen Reference Terkildsen1993; Weaver Reference Weaver2012). The first study taking up this question used a convenience sample of White jury pool members in Louisville, Kentucky, to rate a single male candidate of varying race and skin tone (Terkildsen Reference Terkildsen1993). This revealed that Whites were less willing to vote for and gave more negative evaluations of darker-skinned Black candidates relative to lighter-skinned Black candidates. Building from this, Weaver (Reference Weaver2012) conducted experiments with nationally representative samples of White participants who read about two male candidates side by side with varied race, skin color, phenotype, names, and ideology. Here, White conservatives were less likely to vote for a darker-skinned Black candidate and rated him as less hardworking and trustworthy relative to a White opponent. When evaluating two Black candidates, the lighter-skinned candidate consistently received more positive trait evaluations than his darker-skinned counterpart. Thus, Weaver concludes that the “magnitude of the effect of race on candidate evaluation depended primarily on color” (Reference Weaver2012, p.188). Most recently, Lerman et al. (Reference Lerman, McCabe and Sadin2015) find that the combination of Whites’ partisanship and ideology matters in nuanced ways for their evaluations of a Black male candidate. Although these papers rely on different research designs, samples, and methods of altering a candidate’s skin tone, each finds that lighter-skinned Black male candidates fare better than darker-skinned male candidates among White voters in a survey experimental context.

While these studies have laid a foundation for understanding how skin tone operates in electoral politics, opportunities remain to continue building on their findings. For example, how should we make sense of the varied subgroups of Whites that use a Black candidates’ skin tone as a cue across these studies? And, how would the skin tone of a Black female candidate influence these patterns? To the first question, I argue that explicitly incorporating a broader framework regarding status and position in society may be useful for richer theorizing. To this end, my theoretical framework builds from group position theory, which argues that racial prejudice is a reflection of group competition and concerns about status and power in a multiracial society (Blumer Reference Blumer1958). Competition and racial hostility emerge based on perceptions of positioning within the social order “that in-group members should rightfully occupy relative to members of an out-group” (Bobo and Hutchings Reference Bobo and Hutchings1996, p.955). Moreover, the groups’ status may be made more salient due to big events, such as the election of a Black president or the growing number of non-Whites in the United States (Jardina Reference Jardina2019).

I argue that this theorizing of categorical race should be extended to incorporate finer-grained markers of race, such as skin tone. As noted, darker complexions among African Americans stands as a more drastic contrast to the appearance of many Whites. This is important as colorism operates as a feature of anti-Blackness, with darker skin serving as a cue for proximity to Blackness and resulting in a stronger application of racialized stereotypes (Banks Reference Banks1999; Harris Reference Harris2008; Yadon Reference Yadon2025). Thus, a candidate’s skin tone may influence perceptions of proximity or similarity across racial groups (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Telles and Hunter2000; Schachter et al. Reference Schachter, Flores and Maghbouleh2021). Specifically, a Black candidate with light skin may be viewed as potentially sharing more similar preferences with Whites. This perceived similarity can be viewed as a proxy for perceived group interests.Footnote 2 Empirically, this expectation of greater perceived similarity being meaningful to White voters is bolstered by evidence that White people were more supportive of Barack Obama when his White family or White supporters were highlighted in campaign advertisements (Hutchings et al. 2021). Consequently, a Black political candidate with dark skin may serve as a stronger signal to Whites, reminding them of racial group differences and, in turn, potential threats to group status or interests.

Importantly, these signals should be particularly important to certain subgroups of Whites—namely those concerned about maintaining their dominant status, especially given recent evidence that Whites feel heightened levels of threat (Craig and Richeson Reference Craig and Richeson2014; Jardina Reference Jardina2019). Indeed, threats to Whites’ racial group status may encourage them to take up their White identity more strongly, with this identity being an outgrowth of challenges to their group’s position (Jardina Reference Jardina2019). If this is the case, Whites who identify strongly with their racial group should take more negative views of darker-skinned candidates. Similar patterns should be observed among Whites who identify as Republican or conservative given the association between these political identities and racialized attitudes (Carmines and Stimson Reference Carmines and Stimson1989; Egan Reference Egan2020). In contrast, there should not be strong effects for other groups that do not elevate Whiteness or maintenance of tradition as explicitly (e.g., based on education). Importantly, measures of White identity are associated with views toward tradition, hierarchy, authority, and change (Jardina Reference Jardina2019). Thus, incorporating a measure of White identity into this study alongside other traditional sociopolitical measures allows for a test of this hypothesis:

(H1) White voters who are especially concerned with maintaining Whites’ status and power in society (e.g., strong White identifiers) will penalize darker-skinned Black candidates more harshly than lighter-skinned Black candidates

Accounting for Gender plus Skin Tone in Candidate Evaluations

Until this point, my focus has been on considering how the skin tone of a candidate may influence voter evaluations. Considering the combination of race, gender, and skin tone adds further complexity and important nuance, however. Black women face unique obstacles compared to Black men in terms of perceptions, stereotypes, and more (Brown Reference Brown2014; Brown and Lemi Reference Brown and Lemi2021; Yadon Reference Yadon2025). For example, African Americans routinely believe that darker-skinned Black people receive the worst treatment by police, and that this is often understood to be targeted at darker-skinned Black men (Yadon Reference Yadon2022, Reference Yadon2025). Other examinations highlight that stereotypical portrayals of welfare beneficiaries are perceived as not just being about Black women but darker-skinned Black women specifically (Yadon Reference Yadon2025). Thus, a growing body of evidence suggests that race, gender, and skin tone interact to influence one’s experiences. Understanding the link between race, skin tone, gender, and electoral politics is particularly important to investigate given the growing pool of non-White political candidates in recent years (Lemi Reference Lemi2020; Leslie et al. Reference Leslie, Masuoka, Gaither, Remedios and Chyei Vinluan2022). Given that the literature focused on skin tone and candidate evaluations among White voters has mostly focused on Black male candidates, there is much left to be learned about potential differences (and similarities) based on candidate gender and race.

It is likely, then, that the discussion of potential threat associated with group position discussed in the last section should be amended to incorporate gender. Although darker skin tones of African Americans may signal greater potential threat to Whites, it is possible that these differences could be attenuated by gender. Put differently, a darker-skinned Black woman is likely to be viewed quite differently from a darker-skinned Black man. Although darker-skinned Black people are often stereotyped as being physically stronger and physically aggressive (Parrish 1946), this stereotype may be applied especially strongly to darker-skinned men in a political context. Men are the overwhelming perpetrators of violent crime,Footnote 3 and research shows that Black men are over-represented in news coverage related to crime (Dixon and Linz Reference Dixon and Linz2000; Dixon and Maddox Reference Dixon and Maddox2005; Gilliam and Iyengar Reference Gilliam and Iyengar2000). This may mean that darker-skinned Black male candidates may be viewed especially negatively by White voters. In turn, it is possible that darker-skinned male and female candidates may be perceived and evaluated quite differently by White voters despite their shared race and skin tone.

Darker-skinned female candidates, by contrast, face their own separate set of stereotypes on account of their gender. Women are generally seen as more compassionate and nurturing, as well as less competitive, intelligent, and arrogant than men (Prentice and Carranza Reference Prentice and Carranza2002). Black women, and especially those with darker complexions, can be stereotyped as loud and outspoken (Wilder Reference Wilder2010). This connection between being passionate about issues important to you and politics has been highlighted by news media since the 2020 Presidential election. For instance, news coverage has described Black women as working to “save” the Democratic Party and as the party’s most reliable voting bloc, including Black women’s significant efforts toward electing President Joe Biden in 2020 (e.g., Berry Reference Berry2024; Botel Reference Botel2020; Hall Reference Hall2020; Riccardi Reference Riccardi2022). This suggests a tension between factors that could potentially harm White voters’ perceptions of a darker-skinned Black woman candidate like being outspoke or passionate—or could be viewed positively by some voters as potential signals of commitment to working on behalf of one’s community as a political official.

These factors around race, skin tone, and gender give way to competing expectations. Consistent with the broader colorism literature, it is possible that darker-skinned Black women may be additionally penalized due to their intersecting identities. Indeed, stereotypes are not determined just by race or gender alone, but by the combination of both raced-gendered identities simultaneously (McConnaughy and White Reference McConnaughy and White2011). The prominence of color-based stereotypes related to competence, work ethic, or aggression may mean that darker-skinned Black candidates, whether male or female, will be evaluated more negatively by White voters than their lighter-skinned counterparts. Similarly, lighter-skinned candidates regardless of their gender may be viewed more positively by Whites given perceived similarity to White voters and reduced threat to Whites’ group interests. Conversely, a Black female candidate could be viewed as more ill-suited for politics by White voters, since political interest and engagement are more often associated with men than women (Verba, Burns, and Schlozman Reference Verba, Burns and Lehman Schlozman1997). In this case, the darker-skinned Black female candidate could be especially strongly penalized given both her skin tone and gender signaling her “outsider” status within American politics.

On the other hand, it is possible that in some contexts the combination of attributes often associated with darker-skinned Black women—that is, being compassionate, outspoken, and not afraid to speak truth to power—can be viewed as a positive. Indeed, there is evidence that skin tone and gender interact to influence evaluations of Black political candidates among Black voters. Two recent studies have found that darker-skinned Black candidates are often perceived more positively than lighter-skinned candidates by Black voters, including having a better work ethic and being better at representing the racial group’s interests (Orey and Zhang Reference Orey and Zhang2019; Burge, Wamble, and Cuomo Reference Burge, Wamble and Cuomo2020). Thus, these studies highlight that darker skin can serve as a marker of perceived racial authenticity and be held in high esteem within Black communities, which is consistent with evidence from other contexts outside of electoral politics (Harvey et al. Reference Harvey, LaBeach, Pridgen and Gocial2005; Yadon Reference Yadon2025).

Of course, what factors are influential for Black voters may not be directly analogous to what will be influential for White voters. Still, it is plausible that at least some Whites, namely White Democrats, would be apt to lean on perceptions of a racially authentic darker-skinned woman co-partisan candidate to align with their own views. This may be especially likely given recent media portrayals of Black women as the backbone of the Democratic Party. Such a pattern would also be consistent with evidence of growing liberalization of White racial attitudes among White Democrats in recent years (Engelhardt Reference Engelhardt2021; Jardina and Ollerenshaw Reference Jardina and Ollerenshaw2022), and more specifically, that White Democrats are increasingly supportive of Black politicians (Mikkelborg Reference Mikkelborg2025; Weissman Reference Weissman2025). In combination, these potentially cross-cutting forces lead to competing expectations about the role that gender and skin tone may play among White voters:

(H2) Gender-Color Disadvantage for Darker-skinned Female Candidates: White voters will evaluate dark-skinned female candidates most negatively relative to any other color-gender subgroup (i.e., dark-skinned male candidates, light-skinned female candidates)

(H3) Color (but not Gender) Disadvantage for Darker-skinned Candidates: White voters will evaluate dark-skinned female candidates similarly to dark-skinned male candidates by White voters

(H4) Gender-Color Advantage for Darker-skinned Female Candidates: White voters will evaluate dark-skinned female candidates most positively relative to any other color-gender subgroup (i.e., dark-skinned male candidates, light-skinned female candidates)

Experimental Design

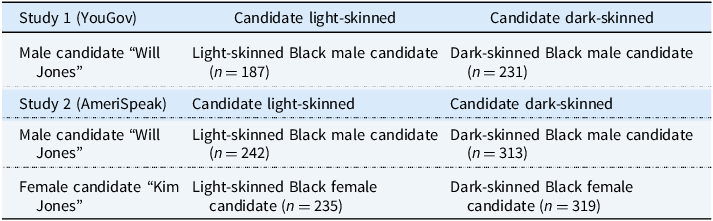

To examine how the skin tone of a Black political candidate is associated with Whites’ views, I conducted two survey experiments with non-Hispanic White Americans.Footnote 4 Both studies use a similar premise: each showed participants a campaign website of a political candidate purportedly running for a non-partisan city council position in Philadelphia. The website included a brief biography and a photo of the candidate without reference to partisanship, ideology, or substantive policy views.Footnote 5 The central component manipulated across conditions is the skin tone featured in the campaign website photos (see Table 1; Appendix 1). In contrast to studies that morph clusters of images, this study capitalizes on technological advancements that allow a graphic designer to realistically alter the lightness/darkness in appearance of a single image drawn from the Chicago Face Database (Ma et al. Reference Ma, Correll and Wittenbrink2015).Footnote 6 This reliance on a single photo means that other racialized features or background factors stay constant (e.g., age, perceived experience), unlike when using different images that are morphed together. Because only the darkness of the candidate’s skin tone changes across conditions, the experimental design provides a direct test of the causal impact of skin tone—distinct from other characteristics like facial features, hair texture, or factors like the candidate’s expressed partisanship or platform.

Table 1. Research designs for candidate experiments

Study 1 was conducted with YouGov and featured only a male candidate, Will Jones. In March 2019, 500 White respondents were recruited from YouGov’s panel, which draws a stratified sample and uses matching techniques to approximate the demographics of the national population on observable covariates. Using a complementary design, Study 2 was conducted in late Fall 2023 by NORC AmeriSpeak at the University of Chicago recruiting nearly 1,300 White Americans from September to December 2023. Descriptive statistics from both samples are provided in Appendix Table A1.1. The primary change to Study 2 was that in addition to the candidate being a light-skinned or dark-skinned man (Will Jones), there were two additional treatment arms added featuring a light-skinned or dark-skinned woman (Kim Jones). Thus, the candidate’s appearance is randomized for participants such that they could view one of four possible candidates: a dark-skinned man, dark-skinned woman, light-skinned man, or light-skinned woman. Importantly, the candidate images used in Study 2 are the same as the images used in Study 1 (see Appendix 1). Because most studies have historically relied upon a male candidate, a goal of this study is to examine what role the combination of gender and skin tone play in influencing Whites’ perceptions.

To assess how colorism manifests in Whites’ views of political candidates, I include three sets of dependent variables in both studies. The first set of variables examines general support for the candidate using three measures: a feeling thermometer of warmth toward the candidate, willingness to vote for the candidate, and willingness to use the researcher’s funds to donate to the candidate’s campaign. The second set examines trait evaluations of the candidate. These items often are associated with race-based stereotypes—for example, the candidate’s work ethic, trustworthiness, morality, or intelligence. One additional item asks participants if the candidate is likely to “care about people like me.” The third set of dependent variables relates to expected job performance, including how well the candidate would manage issues like jobs, health, education, poverty, or crime, if elected. Study 2 was conducted in two waves: all pretest items, including measures of White identity, were measured only in Wave 1 to reduce concerns about priming participants (but see d’Urso, Bonilla, and Bogdanowicz Reference d’Urso, Bonilla and Bogdanowicz2025), while the experiment and all candidate evaluation variables were included only in Wave 2.

The analyses presented here are limited to White respondents who correctly identified the candidate’s race as African American in the post-test manipulation check. A series of robustness checks demonstrate that the results remain consistent even if an alternate manipulation check is used (e.g., correctly reporting another detail about the photo) and in the full sample with no exclusion criteria. Analyses are conducted without survey weighting given the randomized nature of the survey experiment, but the results remain consistent when weights are employed. All variables are coded 0–1 for the analyses below.

Results

To begin, I examine how a Black political candidate’s skin tone influences Whites’ perceptions over time (comparing Studies 1 and 2) and whether there is variation based on the candidate’s gender within Study 2.

Turning first to Study 1, White Americans differentiate between Black male candidates based on skin tone to some extent across all three domains at the aggregate level: overall support for the candidate, trait evaluations, and expected job performance (Figure 1).Footnote 7 Although there are no differences in feeling thermometer scores of the candidate or willingness to donate to their campaign, differences do emerge with respect to vote choice. On average, Whites are five percentage points less willing to vote for the male candidate when he is dark-skinned versus light-skinned (p < .10). With respect to trait evaluations, some evidence suggests the darker male candidate is perceived more negatively. For example, the dark-skinned male candidate is rated as six percentage points less hardworking (p < .05) and six percentage points less likely to care about people like them than the light-skinned male candidate (p < .10). This pattern also occurs in terms of expected performance. Here, too, the darker-skinned male candidate is perceived as less likely to be effective in some domains—for example, jobs (p < .05) or health (p < .10). These patterns suggest that White people do not perceive or evaluate all Black male candidates equally. Instead, White voters favor a lighter-skinned male candidate despite his shared biography with the darker-skinned male candidate.

Figure 1. Main effects of candidate skin tone on Whites’ attitudes in Study 1.

Note: Predicted values estimated using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression with 95 percent confidence intervals.

In Study 2, however, there is no difference between Whites’ evaluations of the Black male candidate based on his skin tone. Where the lighter-skinned male candidate had been consistently viewed more positively in Study 1, just a few years later in Study 2 the darker-skinned male candidate is viewed equally as positively as his lighter-skinned male counterpart in each of the three domains. Given the long-standing literature focusing on male candidates and demonstrating a harsher penalty for darker-skinned Black candidates relative to those with lighter skin, this is a surprising finding running counter to the broader pattern observed in the literature (Lerman, McCabe, and Sadin Reference Lerman, McCabe and Sadin2015; Terkildsen Reference Terkildsen1993; Weaver Reference Weaver2012).

What about evaluations of the female candidate in Study 2? Recall that there were competing expectations about the extent to which the combination of gender and skin tone may mean Black women candidates will be either rewarded or punished by White voters. In the aggregate, there is evidence in support of H4: the darker-skinned female candidate is often viewed more positively by White voters than her lighter-skinned female counterpart (Figure 2). Although there is no difference in feeling thermometer scores between the female candidates, White voters are around four percentage points more likely to vote for the darker-skinned female candidate than the lighter-skinned female candidate (p < .05). Similarly, they are more likely to use the money offered by the researchers to make a larger donation to the darker-skinned female candidate—on the order of approximately 27 cents more (p < .01). In terms of trait evaluations, the darker-skinned female candidate is evaluated as consistently having more positive overall traits when combining across all the trait-related items (p < .01). This includes being perceived as harder working than her lighter female counterpart by about four percentage points (p < .05). The darker-skinned female candidate is also expected to do a better job overall across the various job performance-related items (p < .01). In short, then, there is no evidence that the darker-skinned Black female candidate is penalized by White voters in Study 2. This highlights that the combination of gender and race creates categorically distinct groups where colorism is not applied equally across groups, nor simply as an added dimension of discrimination.

Figure 2. Main effects of candidate skin tone and gender on Whites’ attitudes in Study 2.

Thus, Study 2 presents evidence of two primary things. First, that Black male and female candidates—even those who share a skin tone—are evaluated differently from one another by White voters. This signals the importance of continuing to theorize and study the influence of race and gender in electoral politics, especially as a more diverse pool of candidates is running for political office (Lemi Reference Lemi2020; Leslie et al. Reference Leslie, Masuoka, Gaither, Remedios and Chyei Vinluan2022). Second, Black female candidates do not appear to receive an automatic penalty because of their gender relative to their male counterparts. Indeed, darker-skinned Black female candidates are the gender-skin tone subgroup of Black candidates consistently viewed most positively by White voters. This suggests that the negative stereotypes often associated with darker complexions may be attenuated among Black women as a result of their gender. This is consistent with prior theorizing and evidence that Black men and women face different racialized experiences and stereotypes (e.g., Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1990; Hancock Reference Hancock2007; McConnaughy and White Reference McConnaughy and White2011).

What are the factors driving the differences in attitudes toward the candidates featured in Studies 1 and 2? My theoretical framework suggests that Whites who are most concerned about maintaining their dominant status in society should take more negative views of darker-skinned candidates. To this end, there should be a moderating effect of variables like White identity—given its direct link to group position (Jardina Reference Jardina2019)—as well as Republican partisanship or conservative ideology, given their links to maintaining traditions, which historically placed Whites above other racial groups. As political scientist Ashley Jardina (Reference Jardina2019, p.263) notes, “White identity is defined both by an anxiety about encroachment from other groups, and a recognition that being white has its privileges.” Indeed, threats or challenges to Whites’ racial group status may compel them to develop a stronger sense of White identity. Importantly, relatively simple measures of White identity—such as “How important is your race to your identity?”—are associated with views toward tradition, hierarchy, authority, and resistance to disrupting the status quo (Jardina Reference Jardina2019). Thus, I incorporate this measure of White identity into my studies to capture underlying perceptions of threat to Whites’ status.Footnote 8

Consistent with these expectations and H1, there are a number of treatment effects associated with White identity in Study 1. The interaction between levels of Whites identity and exposure to the treatment reveal that strong White identifiers take a consistently negative view of the dark-skinned candidate (Figure 3). Strong White identifiers feel 12 percentage points cooler toward the dark-skinned male candidate (p < .05) and are 14 percentage points less willing to vote for him (p < .05). Recall that participants were also prompted to donate up to $2 to the candidate’s campaign with the researcher’s funds. Strong White identifiers who viewed the dark-skinned male candidate donated less than half as much as their counterparts who saw a light-skinned male candidate—44 cents versus 97 cents (p < .10). In contrast, Whites who said their racial identity was not important to their sense of self were statistically indistinguishable in their willingness to donate to either the lighter-or darker-skinned male candidate (79 cents vs. 98 cents).

Figure 3. Treatment effects moderated by respondent’s level of White identity in Study 1.

Note: Marginal effects estimated using OLS regression with 95 percent confidence intervals.

With respect to trait evaluations, there are significant interactions between level of White identity and treatment assignment across the board in Study 1. Strong White identifiers are 13 percentage points less likely to believe the candidate cares about people like them (p < .10) and between 17 to 20 percentage points less likely to believe the candidate is hardworking (p < .05), trustworthy (p < .01), moral (p < .01), or intelligent (p < .01). Finally, these more negative assessments also extend to expected job performance. The darker candidate was perceived as between 15 and 24 percentage points less effective in dealing with jobs (p < .05), health (p < .05), crime (p < .01), poverty (p < .01), and education (p < .05) by strong White identifiers.

Recall from the last section that there was no evidence in Study 2 that the darker-skinned candidate, whether male or female, was viewed more negatively by White voters. Accordingly, White identity is not associated with White voters’ evaluations of the candidates in Study 2 (Figure 4). As expected, there is some suggestion that the darker-skinned candidate—and the darker-skinned female candidate in particular—are viewed somewhat more negatively in the eyes of strongly identified White voters, but these interactions do not reach statistical significance. The only place where the effect is approaching traditional levels of statistical significance is with respect to the Black male candidate. Here, strong White identifiers appear slightly less likely to vote for the darker-skinned male candidate (p < .08 one-tailed).

On the whole, there is a meaningful difference between Study 1 in Spring 2019 and Study 2 in Fall 2023 in terms of the relative importance of White identity. In Study 1, a simple yet theoretically rooted measure of White identity reveals potent effects regarding how White identifiers use skin tone as a heuristic for differentiating between Black political candidates. This appeared to underscore that not only do White people differentiate between Black people based on skin tone, but that some subgroups are especially prone to using darker skin tone as a signal for more strongly applying anti-Black stereotypes. By the time of Study 2 in Fall 2023, however, the relative import of White identity is much lower with respect to evaluations of Black political candidates. This may suggest that levels of White identity have decreased over time, while other factors, such as partisanship, remain centrally important (Jardina Reference Jardina2020; Jardina, Kalmoe, and Gross Reference Jardina, Kalmoe and Gross2021). Another contextual shift that may help explain this shift is related to heightened media portrayals of Black women as the backbone of the Democratic Party following the 2020 election of President Joe Biden (Berry Reference Berry2024; Botel Reference Botel2020; Hall Reference Hall2020; Riccardi Reference Riccardi2022). There is also evidence in recent years of growing liberalization of White racial attitudes among White Democrats (Engelhardt Reference Engelhardt2021; Jardina and Ollerenshaw Reference Jardina and Ollerenshaw2022), including evidence most pertinent for this project that White Democrats are increasingly supportive of Black politicians (Mikkelborg Reference Mikkelborg2025; Weissman Reference Weissman2025). This is consistent with the patterns of more positive evaluations of the candidates at baseline in Study 2 compared to Study 1. Consequently, I examine how partisanship is influencing White voters’ evaluations of Black political candidates in my studies in the next section.

Recall that White identity may operate in a complementary way to partisanship or ideology for White Americans. While partisanship and ideology are strongly related for White voters, their racial identity is not similarly correlated with either of these political groupings (Jardina Reference Jardina2019). Consistent with these expectations, I find that partisanship and ideological identification are indeed strongly correlated for Whites in my samples (r = 0.75 Study 1; r = 0.69 Study 2); however, the relationship between White identity and either partisanship or ideology is relatively weak (Partisanship: Study 1 r = 0.17/α = 0.32; Study 2 r = 0.18/α = 0.30; Ideology: Study 1 r = 0.20/α = 0.37; Study 2 r = 0.18/α = 0.30). Examining the moderating effects of White identity taps into a distinct construct from Whites’ partisanship or ideology, then. Thus, it is plausible that looking at the distinct effects of partisanship has the potential to shed light on the patterns found in both Studies 1 and 2.

In Study 1, I find similar patterns based on partisanship as I did White identity. Among White Republicans, darker skin tone of the political candidate cues more negative perceptions of the candidate across all three sets of variables (Figure 5). Republicans are 15 percentage points less likely to report a willingness to vote for the candidate when he is dark-skinned compared to light-skinned, despite their equivalent credentials (p < .01). Even more drastically, White Republicans who saw the dark-skinned candidate are 25 percentage points less likely to report being willing to vote for the candidate compared to Democrats (p < .001). Moreover, Republicans are 15 percentage points less supportive of the candidate when he is dark-skinned (p < .05). Compared to Democrats who saw the dark-skinned candidate, Republicans are nearly 20 percentage points less likely to report that a dark-skinned candidate cares about people like them (p < .01). While the pattern of donations is consistent with the broader findings, there is only suggestive effect of partisanship and exposure to the treatment (p < .06 one-tailed). Whites’ partisanship is also consistently related to assessments of the other two domains as well: trait evaluations and expected job performance of the candidate. Among White Republicans, the darker candidate is consistently perceived as less hardworking, trustworthy, moral, and intelligent (p < .05). This also spills over to perceptions of the candidate’s expected performance on both historically racialized and non-racialized issues if he were elected. The darker-skinned candidate is perceived by Republicans as likely to be less effective in dealing with jobs, health, crime, poverty, and education (p < .05). Thus, both partisanship and White identity play a consistent, meaningful role in White voters’ evaluations of the Black male candidates in Study 1.

Figure 4. Treatment effects moderated by respondent’s level of White identity in Study 2.

Figure 5. Treatment effects moderated by respondent’s partisanship in Study 1.

Note: Marginal effects estimated using OLS regression with 95 percent confidence intervals.

A different pattern emerges in Study 2. With respect to the male candidates, there is very little differentiation based on candidate skin tone by either White Republicans or White Democrats. That is, Democrats are generally warmer toward the Black male candidates than Republicans, but in this study the candidate’s skin tone is not playing nearly as meaningful a role as it did previously in Study 1 or in prior work on Black male candidates. In general, this seems to be driven by a baseline shift among respondents: White Republicans appear to view the dark-skinned male candidate somewhat more warmly, and the light-skinned male candidate often slightly less warmly, on average, in Study 2 relative to Study 1.

Although there were no differences based on skin tone for the male candidate in Study 2, there are differences for the female candidates. Interestingly, both White Republicans and White Democrats tend to view the darker-skinned Black female candidate relatively positively. Importantly, Democrats tend to rate either Black female candidate more positively than their Republican counterparts do—but, among Republicans, there often appears to be a more positive perception of the darker-skinned Black female candidate compared to her lighter female counterpart (Figure 6). This provides further evidence in support of H4 such that the darker-skinned female candidate is viewed especially positively.

Figure 6. Treatment effects moderated by respondent’s partisanship in Study 2.

Although there are no significant interaction terms in these models, the analyses highlight meaningful partisan differences. For example, with respect to vote choice, Republican respondents’ support for the lighter-skinned female candidate was over 7 percentage points lower than support for the darker-skinned female candidate (p < .05). Looking across the full set of trait evaluations, Republicans generally rated the darker-skinned female candidate about 5 percentage points more positively than her lighter-skinned counterpart (p < .05). There are no differences in the aggregate in terms of expected job performance, though, for Republican voters.

Among participants who identified as Democrats, there is somewhat less distinction made between the lighter-and darker-skinned female candidates. Both candidates were supported at relatively high rates by Democrats, including being more likely to vote for either of the female candidates relative to the male candidates. There are no statistically distinguishable differences between Democrats in terms of their perception of the female candidates’ trait evaluations or expected job performance. The only domain where there are clear differences between the two women candidates is with respect to donation amount. Recall that participants were prompted to donate up to $2 using the researchers’ money to the candidate. Here, self-identified Democrats donate around 32 cents, on average, more to the darker-skinned female candidate than to her lighter-skinned female counterpart (p < .01).

In sum, there is an interesting combination of candidate gender, candidate skin tone, and respondent’s partisanship influencing attitudes across studies. The Black female candidates are viewed quite warmly by White voters, on average. This is especially true among White Democrats, but the darker-skinned Black female candidate is also viewed more warmly in some cases than her lighter-skinned female counterpart by White Republicans. Thus, there appears to be something about darker-skinned Black female candidates that allows them to be viewed relatively positively across the political aisle in a survey experimental context. Of course, this stands in stark contrast to the findings for the darker-skinned Black male candidate in Study 1 where White Republicans were especially resistant to supporting his candidacy relative to the lighter-skinned Black male candidate. This underscores how the combination of race, skin tone, and gender can meaningfully influence voters’ perceptions, with gender potentially attenuating the effects of race-or color-based stereotypes.

Discussion

This paper adds to a growing literature demonstrating how colorism influences candidate evaluations, making important contributions by looking at candidate gender and drawing comparisons of pre-and post-2020 data patterns. Drawing from group position theory, a theoretical framework for understanding how Black political candidates will be evaluated by White voters was developed, incorporating expectations around both skin tone and gender. My hypotheses were tested via two complementary survey experiments. In Study 1 from Spring 2019, the dark-skinned male candidate is consistently penalized by White voters relative to his lighter-skinned male counterpart. This is especially true when looking at interactions with White identity and Republican partisanship. In Study 2 from Fall 2023, however, these patterns fall away for the male candidates. Here, it is the darker-skinned Black female candidate for whom there is a more positive reception by White voters—especially so among White Democrats, but there is also some evidence of warmer views of the darker-skinned woman candidate compared to the lighter-skinned woman among White Republicans. In short, this project highlights the value of theorizing and studying the complexity of race and gender, recognizing that the combination of skin tone and gender can meaningfully influence perceptions and experiences.

The mixed pattern of results for the male political candidate is somewhat surprising and inconsistent with the prior literature, which has consistently demonstrated that White voters view lighter-skinned Black male candidates more positively than their darker-skinned male counterparts. Interestingly, the general evaluations of the candidates were much higher in Study 2 compared to Study 1. This could reflect a quirk of the sample gathered in this data collection, or it could suggest that there is something that has changed in the post-2020 political moment with respect to Whites’ evaluations of Black political candidates. Such a change would be consistent with evidence of White Democrats increasingly liberal racial attitudes and increased evidence of enthusiasm about Black political candidates (Engelhardt Reference Engelhardt2021; Jardina and Ollerenshaw Reference Jardina and Ollerenshaw2022; Mikkelborg Reference Mikkelborg2025; Weissman Reference Weissman2025). Future work would do well to further interrogate these patterns and determine how this extends toward understanding intersections of race, skin tone, and gender.

A primary contribution of this project is the incorporation of both skin tone and gender into the theory and analyses. The literature on candidate skin tone and White voter evaluations has heavily focused on Black male candidates (Lerman, McCabe, and Sadin Reference Lerman, McCabe and Sadin2015; Terkildsen Reference Terkildsen1993; Weaver Reference Weaver2012). Work on Black voter evaluations, however, has been more inclusive in incorporating gender alongside examinations of skin tone, hair, and other features, which serves as a model for this project and future research (Brown and Lemi Reference Brown and Lemi2021; Burge, Wamble, and Cuomo Reference Burge, Wamble and Cuomo2020; Orey and Zhang Reference Orey and Zhang2019).

It is noteworthy that some of the patterns found among Black voters—namely, that darker-skinned Black women was viewed more positively and received higher support in the voting booth (Burge, Wamble, and Cuomo Reference Burge, Wamble and Cuomo2020)—are also found here with respect to White voter evaluations. Consistent with my theoretical expectations, this suggests that gender can help attenuate some of the negative stereotypes associated with darker complexions among African Americans. Indeed, there was evidence that the darker-skinned Black female candidate was viewed more positively than her darker-skinned Black male counterpart. Evidence of similarly positive views of darker-skinned Black women candidates among both Black and White voters across this small but growing literature highlights the nuance of race-gendered stereotypes and perceptions which deserve greater attention to more fully understand the American racial landscape.

Future work should also continue to interrogate these patterns through both deeper theorizing and use of mixed-methods studies. The incorporation of rich qualitative data with White voters, for example, would help dig further into the differences uncovered here. That is, how do White Americans talk about Black political candidates (or Black people generally) who are lighter-and darker-skinned? How does this vary when the candidate is a man versus a woman? And what contextual factors can further influence these perceptions of Black Americans—for example, the candidate’s chosen hairstyle, family characteristics, membership in social organizations, or expressed partisanship? While a number of projects have rich qualitative data involving speaking with communities of color about issues of colorism and gender (Brown and Lemi Reference Brown and Lemi2021; Hunter Reference Hunter2005; Yadon Reference Yadon2025), no qualitative work has been conducted to date examining White Americans’ perceptions of colorism dynamics. Given that White people have been demonstrated historically and in the present day to perpetuate colorism either implicitly or explicitly, this is a clear opportunity for valuable expansion to the literature.

Overall, this article helps scholars better understand and predict the constraints and opportunities for political candidates from minoritized groups. Skin tone may be increasingly important as more diverse candidates run for office, while the American racial hierarchy shifts and alters its boundaries to incorporate more groups (Lemi Reference Lemi2020; Masuoka Reference Masuoka2011; Ostfeld and Yadon 2022; d’Urso Reference d’Urso2025). This shifting landscape may also make White voters more prone to use skin tone as a cue in their assessments both inter-personally and in electoral contexts. Future work would benefit from further examinations of White and non-White voters’ perceptions of candidates with a broader range of ethnoracial backgrounds and varying gender and appearance. Not only is the multidimensional nature of race likely to influence Whites’ perceptions of other minoritized groups beyond African Americans, but it would be useful to understand how non-White voters’ support may be influenced by an in-group-or out-group-identifying candidate’s appearance. Examining how factors such as skin tone, gender, racialized features, and racial identity shape candidate evaluations is essential for understanding the evolving dynamics of representation and public opinion in American democracy.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2025.10050.