I. Introduction

A central question in the tort of private nuisance is how its core principles, developed in the nineteenth century, ought to evolve to meet the needs of modern societies.Footnote 1 This article traces the tort’s evolution through two landmark decisions of the UK Supreme Court which sought to address this question: Coventry v Lawrence Footnote 2 and Fearn v Tate Gallery Board of Trustees.Footnote 3

This exercise reveals the following developments. In Coventry v Lawrence, the Supreme Court reformulated nuisanceFootnote 4 in significant ways but left several foundational questions unresolved. In Fearn v Tate Gallery, the Supreme Court again reconfigured the tort, the effect of which was to embed the uncertainties from Coventry v Lawrence more deeply into the conceptual structure of nuisance, without bringing further clarification. The aim of this article is to highlight two consequences of these developments. First, Fearn v Tate Gallery makes it necessary to revisit Coventry v Lawrence, to identify and resolve the uncertainties which permeate that decision and which now, since Fearn v Tate Gallery, require urgent clarification. Second, Fearn v Tate Gallery alters the terms on which those uncertainties should be resolved: solutions developed in the aftermath of Coventry v Lawrence cannot be accommodated within the reconfigured architecture of nuisance following Fearn v Tate Gallery.

The article unfolds as follows. Section II identifies three principal areas of uncertainty created by Coventry v Lawrence: the assessment of locality; the doctrine of coming to the nuisance; and the principles governing remedies. It shows that each area was left in a state of confusion, with core underlying questions unanswered. However, at the time, these uncertainties occupied a relatively minor place within the structure of nuisance and were therefore tolerable.

Section III turns to Fearn v Tate Gallery. It shows that Fearn v Tate Gallery introduced extensive structural changes to nuisance, magnifying these uncertainties and elevating their centrality within the tort. Their resolution has therefore become urgent.

Section IV considers possible ways forward. Each uncertainty had attracted scholarly attention following Coventry v Lawrence.Footnote 5 However, Fearn v Tate Gallery materially alters the terms of the debate; the frameworks developed pre-Fearn v Tate Gallery cannot be accommodated within the restructured tort. This article proposes a Fearn-compliant path towards resolving the uncertainties inherited from Coventry v Lawrence, bridging the gap between these two landmark decisions.

One clarification is required before proceeding. This article does not address the full range of problems underlying nuisance, which extend far beyond the two decisions considered here. Deeper questions exist as to the coherence and conceptual identity of the tortFootnote 6 and as to its proper role in advancing values such as human rights and environmental protection.Footnote 7 These questions will not be resolved by the proposals advanced in this article, which pursue the narrower goal of mitigating specific problems created by the uneasy relationship between the two most significant Supreme Court decisions on nuisance of the twenty-first century.

II. Three Uncertainties from Coventry v Lawrence

Coventry v Lawrence concerned a successful nuisance claim in respect of noise generated by the defendant’s motor-racing stadium near the claimant’s home. The decision’s significance extends well beyond its facts. Across five substantive opinions, the Supreme Court considered how central features of nuisance, dating back “almost 150 years”, should evolve to accommodate “modern planning control” and the need for “varied [land uses] to coexist in a modern society”.Footnote 8

In pursuing this task, the Supreme Court restated core principles of nuisance and engaged with fundamental questions about the role accorded to public interest considerations, pre-existing activities and different kinds of loss. However, these questions remained unresolved, creating three notable areas of uncertainty which are examined in turn: the assessment of locality (Section II(A)), coming to the nuisance (Section II(B)) and remedies (Section II(C)). Each subsection begins with a brief account of the relevant principles, then examines the uncertainty created in Coventry v Lawrence and concludes by considering why that uncertainty remained tolerable at the time.

A. The Locality Principle

In its 1865 decision St. Helen’s Smelting Co. v Tipping, the House of Lords affirmed that whether an interference with enjoyment of land amounts to a nuisance depends “on the circumstances of the place where [it] occurs”.Footnote 9 This “locality principle” was subsequently applied in a series of nineteenth-century decisions, notably Sturges v Bridgman.Footnote 10 In these decisions, “locality” was conceived in unnuanced terms: those living “in a town” were expected to tolerate “operations of trade” in their vicinity and those on a “street [with] numerous shops” could not complain if a “shop is opened next door”.Footnote 11

In Coventry v Lawrence, the Supreme Court restated the principle to address modern complexities which were absent in Sturges v Bridgman: as Lord Carnwath observed, land uses are diversifying, such that a “locality may not conform to a single homogeneous identity, but rather may consist of a varied pattern of uses”.Footnote 12 Additionally, land use is now shaped by “many factors” including planning law and other regulatory controls, rather than by “market forces” alone.Footnote 13

In adapting the locality principle to these challenges, the Supreme Court introduced two significant ambiguities. First, in expanding locality beyond “a single homogeneous identity”,Footnote 14 uncertainties arose as to what activities are considered when characterising a locality. Second, in accounting for regulatory controls, questions were left open as to the significance of planning law to liability in nuisance.

1. The first ambiguity: activities relevant to characterising a locality

A central issue in Coventry v Lawrence was the extent to which a defendant’s own activity should count in assessing locality. The answer to this question, however, is the same for the defendant’s activity as for “any other activity in the neighbourhood”; thus, any uncertainties extend beyond the defendant’s use to all other uses which might characterise a locality.Footnote 15

A core question here concerns the relevance of “unlawful” uses. Lord Neuberger, for the majority, held that “unlawful” uses are “notionally stripped out of the locality when assessing its character”.Footnote 16 However, he did not clarify the scope of this exclusion or the meaning of “unlawful” and the examples offered introduce further uncertainty. For instance, Lord Neuberger stated that “a use in breach of planning law is unlawful” and therefore excluded, but he added that such a use would “perhaps” be taken into account after all if “planning permission was likely to be forthcoming”.Footnote 17 This leaves two key issues unresolved. First, it is unclear how uses in breach of planning law can be deemed “unlawful”: breach of planning law is not itself prohibited and becomes prohibited only if the planning authority exercises its discretion to enforce and the enforcement notice is ignored.Footnote 18 Second, even if breach of planning law were inherently “unlawful”, it is unclear why the likelihood of future permission would alter that conclusion: unless retrospective, that permission would not cure the unlawfulness for the period before grant.

Similarly, Lord Neuberger held that activities amounting to a nuisance are unlawful and excluded.Footnote 19 However, he qualified this statement: if the “actual activities” have already been the subject of a successful nuisance claim in which the court refused an injunction, then they would be taken into account in any subsequent claims, because “whether or not the activities can be described as ‘lawful’, […] they have effectively been sanctioned by the court”.Footnote 20 Lord Neuberger did not specify whether the subsequent claim must be brought by the same claimant or may be brought by others adversely affected by the defendant’s activities. His reference to “actual activities” suggests no such restriction, but his later summary – that the principle applies to situations where the court “award[ed] the claimant damages rather than an injunction” – suggests the reverse.Footnote 21 The difficulty is that a claimant who has already succeeded in nuisance in respect of the defendant’s “actual activities” cannot bring further claims in respect of the same activities,Footnote 22 making such a restriction incoherent. Conversely, if Lord Neuberger’s analysis extends to claims brought by anyone affected by the same activities, the result is also incoherent, since refusal to grant an injunction to one claimant should not make such a significant difference to claims brought by others.

Together, these examples indicate that Lord Neuberger did not exclude all unlawful uses from the assessment of locality: uses likely to receive future planning permission or that have been “sanctioned” by the court in nuisance are not excluded despite being (on his view) unlawful. More broadly, land use may be unlawful for many reasons and it remains unclear which suffice for exclusion. Steel suggests, for example, that uses amounting to a public nuisance are excluded;Footnote 23 it is uncertain what other sources of unlawfulness would suffice under Lord Neuberger’s framework.

These examples indicate too that “unlawfulness” is used loosely, extending beyond prohibited activities: breach of planning law is not prohibited. This raises the question of what other non-prohibited activities might nevertheless be excluded. Steel, for instance, suggests that “unreasonable” uses are “presumably” excluded even if not unlawful;Footnote 24 Lord Neuberger’s analysis leaves space for this possibility, without resolving it.

2. The second ambiguity: the role of planning law

Lord Neuberger, for the majority, held that the existence of planning permission is irrelevant to the assessment of locality in nuisance.Footnote 25 However, significant uncertainty arises from his disagreement with Lord Carnwath, who noted in his dissent that the “wide variety of circumstances in which planning decisions may be made” makes it inappropriate to lay down “general propositions about their relevance” to nuisance.Footnote 26 In disagreement with Lord Neuberger, Lord Carnwath considered that the impact of planning permission on locality should depend on the circumstances underpinning the grant.Footnote 27 For example, he accepted that “strategic” planning decisions, which result from “a considered policy decision” made after “a balancing of competing public and private interests”, could change the character of the locality – a proposition expressly rejected by Lord Neuberger.Footnote 28

These disagreements generate uncertainty because Lord Neuberger’s own reasoning demonstrates that Lord Carnwath’s concern cannot be ignored:Footnote 29 in Coventry v Lawrence, the circumstances surrounding the defendant’s planning permission were highly unusual and, under Lord Neuberger’s own account of the locality principle, could not safely be disregarded.

One unusual feature was that the defendant had a permanent, personal planning permission. Personal permissions are granted only “exceptionally”, in the presence of “strong […] personal grounds”, to permit uses that “would normally not be allowed”; they are furthermore usually temporary and would “scarcely ever be justified” for a “permanent building”.Footnote 30 Lord Neuberger held these circumstances irrelevant: all that mattered was that “the use in question did have planning permission”.Footnote 31 Yet, these circumstances strongly suggest, in planning terms, that the permitted use was not considered ordinarily allowable or reasonable; given Lord Neuberger’s exclusion of “unlawful” uses from the locality, it is striking that these circumstances were ignored.

In addition to a personal permission, the defendant in Coventry v Lawrence had a certificate of lawful use and development (“CLEUD”). A CLEUD is an equally unusual kind of planning permission: it is granted retroactively for uses in breach of planning law that have become immune from enforcement through long use of typically 10 years.Footnote 32 The grant of a CLEUD indicates that, due to the passage of time, “the general interest in proper planning control should yield” to the status quo;Footnote 33 yet, in declining to take it into account, Lord Neuberger observed simply that the “CLEUD was of no relevance, other than as evidence […] that the activities […] had been going on for ten years”.Footnote 34 This is difficult to reconcile with Lord Neuberger’s own conclusions on “unlawful” uses: a CLEUD confirms that an activity has persisted for 10 years in breach of planning law and should therefore be excluded from the locality because it is (on Lord Neuberger’s view) unlawful. Indeed, Lord Neuberger stated that unlawful activities are excluded irrespective of “whether they have been going on for a few days or many years”, save only that a right to commit the interference might be acquired after 20 years.Footnote 35 On this logic, evidence of an “unlawful” activity that has persisted for 10 years should point strongly towards exclusion from locality.

These findings reinforce Lord Carnwath’s view that the circumstances in which planning permission is granted cannot be ignored in assessing locality: on Lord Neuberger’s own account, such circumstances should be material, at least in relation to “unlawfulness”. Lord Neuberger’s blanket rejection of the relevance of planning permission to the character of the locality, therefore, generates significant uncertainty.

Nevertheless, three factors suggest that these uncertainties occupied a minor place within the nuisance framework established in Coventry v Lawrence and were therefore tolerable at the time. First, the Supreme Court stressed that locality was just one element of a broader unreasonableness inquiry; it was not determinative of liability. As Lord Neuberger affirmed, “an activity can be a nuisance even if it conforms to the character of the locality”.Footnote 36 Including an activity in the assessment of locality did not preclude a finding of liability. More broadly, Lord Neuberger noted that the locality principle often has limited significance: “[in] many cases, it is fairly clear whether or not a defendant’s activities constitute a nuisance” without needing to address locality.Footnote 37 On this view, uncertainties as to the precise scope of the locality principle do not significantly undermine the workability of the tort.

Second, although the relevance of planning permission to locality remains uncertain, planning law was treated in Coventry v Lawrence as relevant to liability in other ways. All five justices agreed that the terms of a planning permission and materials before a planning authority such as planning officers’ reports, were relevant to the unreasonableness inquiry.Footnote 38 As locality was only one factor within that broader assessment, the irrelevance of planning permission to locality did not exclude planning law from influencing liability elsewhere. Moreover, planning law was seen as directly relevant to liability in cases where the claimant asserts a novel interest not yet recognised as actionable in nuisance: while planning permission does not bar an existing claim, courts may refuse to extend nuisance to new interferences if planning law already regulates them.Footnote 39

Third, planning law was not the only lens through which public interest considerations entered the locality principle. Other public interest indicators were considered in Coventry v Lawrence as relevant to locality. As Lord Carnwath observed, the public interest was inherent in Lord Westbury’s formulation of the principle in St. Helen’s v Tipping: a person living in a town must put up with trade precisely because trade was “for the benefit of […] the public at large”.Footnote 40 Similarly, neighbours to a “major football stadium” cannot complain of disturbance precisely because it is a “necessary price for an activity regarded as socially important”.Footnote 41 Lord Carnwath expressly acknowledged the role of the public interest in assessing locality, noting that the “public interest comes into play […] in evaluating the pattern of uses […] against which the acceptability of the defendant’s activity is to be judged”.Footnote 42 Thus, although the role of planning permission within locality remained unclear, the public interest – which planning law is said to represent – was independently accommodated within that principle.

B. Coming to the Nuisance

A further uncertainty in Coventry v Lawrence concerns time. Defendants sometimes seek to defeat a nuisance claim by arguing that their activity predates the claimant’s acquisition or use of the affected land. This is known as “coming to the nuisance”. Before Coventry v Lawrence, courts consistently rejected the defence,Footnote 43 most notably in Bliss v Hall Footnote 44 and Sturges v Bridgman.Footnote 45 However, in obiter, Lord Neuberger sought to restate these principles, thereby undermining the clarity of both the status and content of coming to the nuisance.

Lord Neuberger distinguished between two situations. Where a claimant continues to use their land “for essentially the same purpose” as they did before the defendant’s activity began, no defence arises.Footnote 46 But where a claimant “builds on, or changes the use of” their land after the defendant’s activity began, a defence is potentially available. Lord Neuberger sought to maintain strict separation between these two situations, stating that the second situation “raises a rather different point from the issue of coming to the nuisance”.Footnote 47 However, as Kennefick observes, this distinction is “unconvincing”: Lord Neuberger’s approach amounts to a “limited and badly disguised” form of the defence.Footnote 48 Indeed, in Sturges v Bridgman, the defence was rejected even though the nuisance arose after the claimant built near the edge of his land once the defendant’s activity had begun. The limits and status of Lord Neuberger’s defence therefore remain uncertain.

Lord Neuberger’s approach allows defendants to rely on their pre-existing activity if five conditions are met:

-

(1) the activity “affects the senses” only (rather than physically damaging the affected land);

-

(2) it was “not a nuisance” before the claimant’s building or change of use;

-

(3) it is “reasonable and otherwise lawful”;

-

(4) it is “carried out in a reasonable way”; and

-

(5) it “causes no greater nuisance” than at the time of the claimant’s building or change of use.Footnote 49

Regarding the second condition, Lord Neuberger did not explain whether the activity must not have been a nuisance to anyone or only to the claimant. Immediately before setting out his five conditions, Lord Neuberger framed his defence as intended for activities “originally not a nuisance to the claimant’s land”,Footnote 50 but his test itself contains no such restriction. This ambiguity matters in cases where a claimant adopts a use consistent with the surrounding area. Consider a noisy factory adjoining a row of 50 houses. The claimant builds a house on a vacant plot at the end of the row. The factory was not a nuisance to the claimant’s land before construction, but it may have been a nuisance to the existing houses. Whether Lord Neuberger’s second condition is satisfied in such cases remains uncertain.

On the fifth condition, Lord Neuberger gave no guidance on how to determine the timing of the claimant’s change of use. Building and change of use are gradual; identifying a precise moment is difficult. Lord Neuberger cited Kennaway v Thompson Footnote 51 as an example of his suggested approach.Footnote 52 Yet the approach taken in Kennaway v Thompson was markedly different: in that decision, the relevant time was when the claimant applied for planning permission.Footnote 53 Submitting a planning application does not equate to a change of use: in Kennaway v Thompson, the claimant did not build her house until three years later. More generally, planning applications may be rejected or the use applied for may never materialise. Lord Neuberger’s approval of Kennaway v Thompson, without clarification, introduces considerable uncertainty about timing.

Moreover, Lord Neuberger did not say that a defence exists whenever the five conditions are satisfied: he stated only that “it may well be wrong” to impose liability when they are met.Footnote 54 This suggests the existence of further, unstated limits. Lord Neuberger’s attempts to reconcile his new approach with existing case law support this interpretation. In distinguishing Sturges v Bridgman, he emphasised that the claimant’s building works there “merely involved an extension to an existing building”.Footnote 55 This implies that building extensions do not trigger Lord Neuberger’s new defence; however, no such qualification appears in the five conditions. This raises doubt about the possibility of other unstated limits.

Nevertheless, several factors suggest that these uncertainties were of limited importance in Coventry v Lawrence. Although Lord Neuberger described his framework as “a defence”,Footnote 56 he envisaged it operating through the locality principle: by treating the defendant’s activity as “part of the character of the neighbourhood”.Footnote 57 As noted in Section II(A), the locality principle was framed in Coventry v Lawrence as one component of the broader unreasonableness inquiry. Even if Lord Neuberger’s five conditions were met, a court could still find the activity unreasonable despite contributing to the locality’s character. Conversely, where the five conditions were not met, a defendant might still avoid liability if the interference was deemed reasonable, even if the activity was inconsistent with the locality. Thus, ambiguity in Lord Neuberger’s framework on coming to the nuisance did not decisively affect the operation of nuisance as structured in Coventry v Lawrence.

C. Remedies

Once the claimant establishes an actionable nuisance, the court must determine the appropriate remedy. For future interferences,Footnote 58 courts have discretion under section 50 of the Senior Courts Act 1981 to award an injunction or damages in lieu thereof. Prior to Coventry v Lawrence, the exercise of this discretion was guided by Shelfer v City of London Electric Lighting Co. (No. 1), in which Smith L.J. set out four “tests” that, if all satisfied, pointed towards refusing an injunction and awarding damages instead.Footnote 59 As Lee notes, these tests “were interpreted very narrowly and applied rigidly”.Footnote 60 All five justices in Coventry v Lawrence signalled a departure from this approach, favouring a more flexible framework: where the Shelfer test is met, an injunction should “normally” be refused, but, where it is not, additional factors may still be considered.Footnote 61

In introducing this new approach, Lord Neuberger acknowledged the “risk of introducing a degree of uncertainty into the law”.Footnote 62 Two uncertainties are particularly significant. First, the range and weight of relevant factors remain undefined. Second, where an injunction is refused, the proper basis for calculating damages in lieu thereof is unsettled.

1. The first ambiguity: relevant factors and their weight

Lord Neuberger stressed that the remedial discretion “should not […] be fettered”, but he also suggested that courts ought to “lay down rules as to what factors can, and cannot, be taken into account”.Footnote 63 This implies that some factors are impermissible, but none were identified; only illustrations of relevant factors were provided. These include the defendant’s conduct: damages may be appropriate if the defendant “acted fairly and not in an unneighbourly spirit”, whereas an injunction may be “necessary” if the defendant’s conduct was “high-handed”.Footnote 64 The likely impact of an injunction on the defendant’s activity is also relevant, particularly if it “may have to shut down”.Footnote 65 Importantly, “the public interest” is a further relevant factor: courts may consider, for instance, that “the defendant’s employees would lose their livelihood” or that “many other neighbours in addition to the claimant are badly affected”.Footnote 66

The weight afforded to these factors was not explained. In particular, the importance of public interest considerations remains ambiguous. Lord Neuberger, for the majority, stated only that “it is very easy to think of circumstances in which [the public interest] might […] not begin to justify [refusing or awarding] an injunction”.Footnote 67 He did not, however, identify any such circumstances, apart from noting that an injunction “may well not be […] appropriate” where it “would involve a loss to the public” and “stop the defendant from pursuing” their activity.Footnote 68

However, as Lord Carnwath observed, most nuisance claims do not involve “such drastic alternatives” as shutting down the defendant’s activity or else allowing it to continue unchanged; an injunction can often “set reasonable limits for [the activity’s] continuation” or be “combine[d] with an award of damages”.Footnote 69 In such circumstances, the weight afforded to the public interest is unclear. Moreover, what counts as “stopping” the defendant’s activity is uncertain. As Lee notes, businesses rarely face a “simple close down/stay open dichotomy”; relocation, for example, does not amount to closure, yet its “impact on local communities” may be similar.Footnote 70 Even if an activity continues in limited form, “the costs of complying with an injunction [may be passed on to] communities”.Footnote 71 The role of the public interest in such situations remains ambiguous, leaving trial judges in the “invidious position” of navigating conflicting and incomplete opinions or else reverting to Shelfer v City of London Electric Lighting Co. (No. 1) on the ground that Coventry v Lawrence is “entirely lacking in workable guidance”.Footnote 72

More fundamentally, no attempt was made in Coventry v Lawrence to clarify what counts as “the public interest”, even though, as Lee notes, “public interests […] are contested and plural, and not easily separated from private or individual interests”.Footnote 73 In particular, no distinction was drawn between defendant-sided and claimant-sided public interests: Lord Neuberger identified both the risk of lost income to “the defendant’s employees” and the fact that “many other neighbours in addition to the claimant” are affected, as examples of public interests.Footnote 74 But these are not equivalent: defendant-sided interests may readily weigh against an injunction, while it is difficult to see how claimant-sided interests could weigh in favour of one. The purpose of an injunction is to protect the claimant’s property right only and its terms are tailored to that limited function. This was recognised in Austin v Miller Argent (South Wales) Ltd., where it was noted that “any remedy is likely to be directed to the precise conditions prevailing at [the claimant’s] home” and unlikely to benefit neighbours beyond “the immediate vicinity of” the claimant’s land.Footnote 75 If an injunction is refused, all of the defendant’s employees keep their jobs; if granted, only the claimant, and perhaps a few neighbours very close by, benefit. The fact that “many other neighbours” are affected cannot, therefore, plausibly carry weight in favour of an injunction. This asymmetry undermines the coherence of treating both interests as equivalent examples of “the public interest”.

2. The second ambiguity: quantification of damages in lieu of an injunction

Traditionally, damages in lieu of an injunction were assessed by the diminution in the value of the claimant’s land resulting from the continuation of the nuisance.Footnote 76 The Supreme Court in Coventry v Lawrence accepted this as a starting point, but it declined to decide the proper approach.Footnote 77 Two alternatives were suggested. The first, proposed by Lord Neuberger, was that damages should, “where […] appropriate”, be “assessed by reference to the benefit to the defendant of not suffering an injunction”.Footnote 78 He gave no guidance as to when this approach would be “appropriate” and noted arguments suggesting that this might “never, or only rarely” be the case.Footnote 79 Lord Clarke agreed that this method might sometimes be suitable, but also suggested that there is “no reason in principle” against quantifying damages by reference to the “reasonable price for a licence to commit the nuisance”.Footnote 80

Lord Carnwath, by contrast, declined to endorse either alternative. He emphasised that these approaches had been used only for “clearly defined interference[s] with […] specific property right[s]”, such as trespass or breach of restrictive covenant: he doubted that these approaches would be transferable to amenity nuisance, which involves “less specific” harms.Footnote 81 These uncertainties are significant, given that the approach to discretion adopted in Coventry v Lawrence may lead to injunctions being refused more frequently. The absence of clear guidance on choosing among the three suggested bases or on whether others might be permissible undermines certainty in the remedial framework. And while Lord Neuberger conceded that clearer principles would “have to be worked out […] on a case by case basis”,Footnote 82 there is little evidence suggesting that such principles have materialised. In the right to light context, courts have occasionally refused injunctions and quantified damages by reference to the reasonable price obtainable through negotiation.Footnote 83 In other contexts, however, there is little sign of courts refusing an injunction on the flexible basis advanced in Coventry v Lawrence,Footnote 84 unless the Shelfer criteria were also satisfied.Footnote 85

Nevertheless, there are reasons to regard these uncertainties as tolerable. A recurring theme in Coventry v Lawrence was the close connection between liability and remedies. Lord Sumption, for example, observed that “the question what impact the grant of planning permission should have on liability […] and the question what remedies should be available in nuisance are closely related”: both are concerned with how best to “reconcile public and private law in the domain of land use where they occupy much the same space”.Footnote 86 The interconnectedness between liability and remedies meant that the same set of factors appeared at both stages: as Section II(A) illustrates, the public interest, planning law and the defendant’s conduct were not irrelevant to liability. The remedies question did not, therefore, bear the full weight of these considerations. In this light, uncertainties surrounding discretion and quantification were tolerable, because other mechanisms allowed these factors to enter the nuisance inquiry.

D. Conclusion to Section II

In reformulating core aspects of nuisance, Coventry v Lawrence introduced significant uncertainties, of which this section has identified three. First, the locality principle became unclear, both as to what activities contribute to the pattern of uses and as to the role of planning law. Second, the status and scope of coming to the nuisance were obscured by Lord Neuberger’s obiter framework, which allowed defendants, in certain circumstances, to rely on their pre-existing activities to defeat a claim. Third, the principles governing remedies were unsettled by the move towards a more flexible approach to injunctions, coupled with a lack of guidance on quantifying damages in lieu thereof.

Yet, these uncertainties did not, at the time of Coventry v Lawrence, render the tort unworkable. Each uncertainty was largely contained by the broader architecture of nuisance set out in that decision. The uncertainties surrounding locality and coming to the nuisance were tempered by the overarching unreasonableness inquiry, of which locality was only one component. The ambiguities relating to remedies were mitigated by a framework which treated liability and remedies as deeply interconnected, thereby dispersing the burden of accommodating public interest and regulatory considerations across both stages of analysis.

The next section turns to Fearn v Tate Gallery, arguing that the Supreme Court’s reasoning in this case dismantled this scaffolding which had previously contained the uncertainties in Coventry v Lawrence. Re-engagement with these uncertainties is now no longer optional, but imperative.

III. The Impact of Fearn v Tate Gallery on the Uncertainties from Coventry v Lawrence

Fearn v Tate Gallery concerned a nuisance claim arising from the defendant’s operation of a public viewing gallery, which allowed large numbers of visitors to look directly into the claimants’ neighbouring flats. In finding for the claimants, a three-to-two Supreme Court majority reshaped nuisance in two far-reaching ways. First, the concept of “unreasonableness” was recast as merely a “conclusion” about the lawfulness of the defendant’s activity, rather than the core standard for determining liability.Footnote 87 Second, a principle of “common and ordinary use” was introduced as the near-determinative criterion for assessing lawfulness in nuisance.Footnote 88

Although Lord Leggatt sought to ground these developments in “principles […] settled since the 19th century”,Footnote 89 they are novel. Lord Leggatt relied in particular on the 1860 decision of Bamford v Turnley, in which Bramwell B. held that “ordinary use […] of land” does not attract liability in nuisance.Footnote 90 However, as Lord Sales noted in dissent, this does not support the broader and very different proposition advanced by Lord Leggatt: that “only acts which constitute […] ordinary use” escape liability in nuisance.Footnote 91 Lord Leggatt also reliedFootnote 92 on Carnwath L.J.’s remark in Barr v Biffa Waste Services Ltd. that “reasonable user” is merely “a different way of describing old principles”.Footnote 93 However, those comments were directed at a very different point: that a defendant cannot avoid liability simply by demonstrating that their use – as distinguished from the interference it causes – is reasonable.Footnote 94 Lord Leggatt’s rejection of unreasonable interference as the standard of liability therefore represents a departure from the status quo.

This section argues that these developments dramatically raise the stakes of the uncertainties left unresolved in Coventry v Lawrence: they transform peripheral ambiguities into fundamental questions at the conceptual centre of the tort. The discussion proceeds in three parts, with each part addressing one area of uncertainty. Each subsection begins by examining the failure in Fearn v Tate Gallery to resolve the uncertainty inherited from Coventry v Lawrence, before demonstrating how the majority’s reasoning renders clarification newly urgent.

A. The Locality Principle

Lord Leggatt, delivering the only speech for the majority in Fearn v Tate Gallery, devoted just four paragraphs to the locality principle, focused exclusively on the nineteenth-century decision of Sturges v Bridgman.Footnote 95 After summarising the facts and reasoning in Sturges v Bridgman, Lord Leggatt observed only that the locality there was not “devoted to manufacture”, but was instead “primarily residential, with professionals […] conducting business from their homes”.Footnote 96

This strikingly limited account fails to engage with the complexities identified in Coventry v Lawrence. As explained in Section II(A), Coventry v Lawrence addressed the need to adapt the locality principle to modern environments where varied land uses coexist, shaped by planning and regulatory controls. Fearn v Tate Gallery offered no guidance on navigating these complexities, instead presenting a model in which localities bear singular labels such as “residential area” or “manufacturing town”. By sidestepping the refinements developed in Coventry v Lawrence, the majority left unresolved the core uncertainties surrounding locality.

The facts of Fearn v Tate Gallery underscore this problem. The trial judge assessed the locality as encompassing “a mixture of residential, cultural, tourist and commercial purposes”.Footnote 97 However, Lord Leggatt did not explain how this hybrid character should inform liability; instead, he treated as decisive the absence of any “other viewing platform” nearby and the lack of evidence that the defendant’s activity “should actually be expected” in the area.Footnote 98 This reasoning reflects the logic of Sturges v Bridgman: locality protects prevalent uses and so the character of a neighbourhood depends simply on how many users engage in a particular activity. By contrast, Coventry v Lawrence stressed the opposite problem: a singular use – such as a motor-racing or football stadium – may dominate and define a mixed-use locality despite being numerically exceptional and unexpected at its inception. It is this recognition that produced the core uncertainty in Coventry v Lawrence: which activities should, and should not, count in assessing locality. As Steel observes, “one would expect that the fact that the predominant land use in an area has changed should alter the entitlements of persons in that area”:Footnote 99 in Fearn v Tate Gallery, the viewing gallery, attracting half a million visitors annually,Footnote 100 might well constitute exactly the kind of singular, predominant use to trigger the issue.Footnote 101 Yet Fearn v Tate Gallery is silent on this point, treating locality as a question of numbers and of actual, not entitled, expectations. This silence magnifies, rather than resolves, the uncertainties left by Coventry v Lawrence.

The effect of Fearn v Tate Gallery is not merely to leave the locality principle unclear. The majority’s reasoning also restructures nuisance in such a way that makes locality central to liability. As Section II(A) showed, locality under Coventry v Lawrence was merely one factor within the overarching “unreasonableness” inquiry and was not determinative of liability. In Fearn v Tate Gallery, however, the majority rejected “unreasonableness” as the governing standard.Footnote 102 In its place, as Lord Sales put it in his dissent, the majority elevated the question of “ordinary use […] in a locality into […] the be all and end all of the test for nuisance”.Footnote 103 Indeed, Lord Leggatt held that the lawfulness of an interference is determined, first, by asking whether the interference is substantial and second, whether the parties’ respective uses of land are “common and ordinary […] having regard to the character of the locality”.Footnote 104 If the defendant’s use is unusual in its locality, then it is unlawful provided the interference is substantial.Footnote 105 Conversely, if it is ordinary in its locality, then it is lawful irrespective of how substantial the interference may be.Footnote 106

On this approach, ordinariness in the locality becomes near-determinative of liability (with substantiality as the only other criterion). This departs sharply from Coventry v Lawrence, where locality-consistent activities could still cause unreasonable interference and amount to a nuisance and locality-inconsistent activities could still be lawful.Footnote 107 Fearn v Tate Gallery removed these additional safeguards: locality shifted from being one of several considerations to a decisive benchmark of liability. This, in itself, is not necessarily problematic: in principle, “ordinariness” could be developed flexibly by reference to varied criteria. However, “ordinariness” was applied rigidly in Fearn v Tate Gallery. As Hariharan observes, Lord Leggatt “simply asserted” that the claimants’ use was ordinary in the locality, despite the trial judge’s finding that the flats’ design and their manner of occupation were “uncharacteristic of the neighbourhood”.Footnote 108 This reflects Lord Leggatt’s broader finding that the “right to build […] is fundamental to the […] ordinary use of land”, such that a building was ordinary in the locality irrespective of design and residential use was ordinary irrespective of the precise mode of occupation.Footnote 109 On this view, “ordinariness” is reduced to a categorical label and is insensitive to the precise features of specific uses: “buildings” and “residential use” are ordinary in the locality and questions as to whether the specific building and its specific mode of occupation are consistent with the locality, require no examination. Such an approach precludes flexible development of “ordinariness” to take account of the nuances and complexities identified in Coventry v Lawrence, leaving the locality principle to bear this weight. The ambiguities inherited from Coventry v Lawrence are therefore no longer peripheral and resolving them has become imperative.

B. Coming to the Nuisance

In Fearn v Tate Gallery, Lord Leggatt explained at length why coming to the nuisance is not a defence,Footnote 110 yet devoted only one short paragraph to Coventry v Lawrence. He merely noted Lord Neuberger’s suggestions of a defence for activities pre-dating the claimant’s change of use, remarking that these “may in future need to be revisited but do not arise for decision on this appeal”.Footnote 111 On the facts, there was dispute as to which party’s use came first, but Lord Leggatt dismissed the issue as irrelevant, stating simply that “it would not have mattered if the viewing gallery had already been operating when the [claimants’] flats were built”.Footnote 112

This cursory treatment is striking: Fearn v Tate Gallery presents exactly the sort of scenario in which Lord Neuberger’s formulation could have been decisive had the defendant’s activity predated the claimants’ flats.Footnote 113 All five of his criteria would appear prima facie satisfied: the interference affected the senses only; the activity could not have been a nuisance before the flats were built, as there were no comparable residential buildings nearby; the trial judge found the use reasonable and operated in a reasonable way; and there was no suggestion of intensification. If Lord Neuberger’s framework were accepted, the sequence of the parties’ activities would have mattered. Given this potential significance, Lord Leggatt’s cursory dismissal of the issue may suggest dissatisfaction with Lord Neuberger’s framework, yet he did not reject it, nor did he explain why it did not apply. This silence leaves the status and operation of coming to the nuisance as uncertain as before.

Here, too, Fearn v Tate Gallery does more than leave the ambiguities from Coventry v Lawrence unresolved: it magnifies their importance. Section II(B) showed that, in Coventry v Lawrence, uncertainties surrounding coming to the nuisance were cushioned by two safeguards: the locality principle and the overarching unreasonableness inquiry. The locality principle, as understood in Coventry v Lawrence, meant that whatever the status of coming to the nuisance, a defendant might escape liability if their established activity defined the character of the neighbourhood. The unreasonableness standard meant that, independently of coming to the nuisance, a defendant could escape liability by showing the absence of unreasonable interference.

Both safeguards were undermined in Fearn v Tate Gallery. As Section III(A) explained, the locality principle appears to have been pared down to a largely numerical assessment, stripped of its potential to shield singular but character-defining activities such as football stadiums or, indeed, viewing galleries. More fundamentally, unreasonableness was abandoned as a liability standard.Footnote 114 These changes leave Lord Neuberger’s version of coming to the nuisance as the only remaining doctrinal space in which to address questions about how established a defendant’s activity is within a neighbourhood and whether it is a reasonable use of land. The result is a heightened and immediate need to clarify the status and limits of this formulation.

C. Remedies

As explained in Section II(C), Coventry v Lawrence left two major uncertainties regarding remedies: how the discretion between an injunction and damages in lieu thereof is to be exercised and how the latter is to be quantified. In Fearn v Tate Gallery, Lord Leggatt devoted just three paragraphs to the first issueFootnote 115 and did not address the second. In the last of these paragraphs, Lord Leggatt acknowledged that “there is little in the way of […] guidance to be gleaned from” Coventry v Lawrence on the exercise of remedial discretion, but offered no clarification on this point.Footnote 116

This lack of engagement with remedies is understandable given that the issue was not argued before the Supreme Court.Footnote 117 However, the majority in Fearn v Tate Gallery did more than leave existing uncertainties in place: they also reshaped nuisance in a way that greatly increased the work that the remedies inquiry must perform. As explained in Section II(C), liability and remedies were closely interconnected in Coventry v Lawrence: factors such as planning law and the public interest, though primarily relevant to remedies, could also shape liability.Footnote 118 This overlap meant that the conceptual weight of those considerations was distributed across both stages of the nuisance inquiry.

Fearn v Tate Gallery dismantled this interconnection: Lord Leggatt drew a sharp division between liability and remedies, stating unambiguously that it is “wrong to treat [the public interest] as relevant to the question of liability […] rather than only […] to the question of what remedy to grant”.Footnote 119 In doing so, Lord Leggatt severed the three Coventry-compliant routes for considering the public interest and planning law at the liability stage, identified in Section II(A).Footnote 120 These were, first, that the public interest explained why persons in certain localities were expected to tolerate greater interferences than others. Second, planning conditions and evidence before a planning authority provided evidence of what was reasonable. Third, the fact that planning law already addressed a particular kind of interference weighed against expanding nuisance to cover the same ground.

All three safeguards were expressly rejected in Fearn v Tate Gallery. Lord Leggatt criticised the trial judge for factoring the public interest into the assessment of reasonableness and more generally into liability.Footnote 121 And, although visual intrusion was a novel interference, Lord Leggatt expressly rejected as irrelevant the fact that planning law already regulates overlooking and privacy.Footnote 122 The effect is that all questions of public interest, planning law and the wider regulatory context must now be addressed exclusively at the remedies stage.

This shift radically increases the burden placed on remedial discretion, yet the principles governing that discretion remain uncertain. The result is an unstable framework in which the most normatively charged elements of nuisance are funnelled entirely into the stage least clearly governed by principle. Clarifying that stage has therefore become urgent.

D. Conclusion to Section III

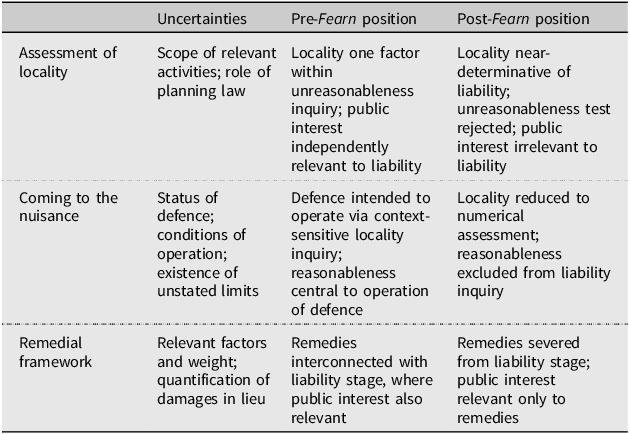

The analysis in this section reveals a clear pattern: Fearn v Tate Gallery left the uncertainties from Coventry v Lawrence unresolved, while simultaneously reshaping nuisance so that these uncertainties now lie at its core. On locality, Fearn v Tate Gallery elevated what had been one factor within a broader unreasonableness inquiry into a near-determinative benchmark, yet offered no guidance on how to characterise locality in mixed-use environments. On coming to the nuisance, Fearn v Tate Gallery removed the alternative routes by which temporal priority and reasonableness could be taken into account, while leaving the status and limits of Lord Neuberger’s proposed framework unclear. On remedies, Fearn v Tate Gallery excluded public interest and planning considerations from liability altogether, channelling them entirely into a remedial discretion the scope of which remains undefined.

The resulting position is summarised in Table 1. In Coventry v Lawrence, the uncertainties were tolerable because they were buffered by other elements of the nuisance inquiry; in Fearn v Tate Gallery, these buffers were stripped away. The new architecture of nuisance places significant normative weight on a small set of ill-defined concepts. Confronting and resolving the uncertainties underlying these concepts have therefore become pressing.

Table 1. The impact of Fearn v Tate Gallery on three uncertainties from Coventry v Lawrence

IV. A Way Forward

Section III showed that the changes to the law of nuisance introduced in Fearn v Tate Gallery make it necessary to revisit the uncertainties left by Coventry v Lawrence. This section considers how the three areas of uncertainty should be resolved. It argues that the methodologies developed in the scholarship following Coventry v Lawrence cannot be accommodated within Fearn v Tate Gallery’s revised framework and that new solutions are required. Specific, Fearn-compliant avenues towards the development of these solutions are thereafter identified.

A. The Locality Principle

In the aftermath of Coventry v Lawrence, Steel proposed a way of developing the locality principle to take appropriate account of singular, large-scale uses, such as the introduction of a football stadium into a previously residential neighbourhood.Footnote 123 He noted that Lord Neuberger’s formulation in Coventry v Lawrence suffers from a fatal “logical problem”: unlawful activities are excluded from the assessment of locality, but whether a use is unlawful depends on the result of that very assessment.Footnote 124 Steel’s solution was to accept that the introduction of an activity of such magnitude “alter[s] the entitlements of persons in that area” and should therefore change the character of the locality.Footnote 125 On this approach, “the law will generally follow the changed factual circumstances in the area” and will only rarely exclude activities from the locality.Footnote 126

This approach, however, relied on structural safeguards within nuisance that are irreconcilable with Fearn v Tate Gallery. Steel acknowledged that his approach risked being “overly favourable to persons whose conduct changes the nature of the locality”, but argued that this risk was mitigated by several factors.Footnote 127 The first was that “even if the defendant’s own activity is taken into account in full, it does not follow that the claimant must fail”.Footnote 128 But, as explained in Section III(A), that conclusion depended on the holding in Coventry v Lawrence that activities consistent with the locality could nevertheless amount to a nuisance – an approach incompatible with Fearn v Tate Gallery’s elevation of locality to a near-determinative standard.

An additional safeguard proposed by Steel was that there “ought to be limits on permissible interference” operating independently of locality: “some threshold beyond which the normality of the activity in the locality does not justify the interference.”Footnote 129 Steel argued that, although the “cases do not establish such a threshold”, it was “plausible […] that one exists”.Footnote 130 Indeed, such a safeguard was compatible with Coventry v Lawrence, where liability was governed by an unreasonableness inquiry capable of encompassing a wide range of limits. But it is incompatible with Fearn v Tate Gallery, in which the majority held that an activity ordinary in its locality is not a nuisance, no matter how substantial the resulting interference.Footnote 131 Within this framework, if nearly all existing activities count towards locality, as Steel suggested, then almost all defendants will escape liability.

New solutions are therefore required. In a post-Fearn landscape, a methodology on locality needs to accomplish three tasks. First, it must account for singular, predominant uses without allowing them automatically to redefine a locality. With locality near-decisive of liability, an “every use counts” approach would lead to liability being imposed far too rarely. Conversely, ignoring singular, locality-defining uses would collapse locality into a purely backward-looking mechanism which protects only historically and numerically prevalent uses.Footnote 132 As explained in Section III(A), Fearn v Tate Gallery itself highlighted this problem: the absence of comparable viewing galleries and of actual prior expectation that one would be built, was treated as decisive even after the defendant’s gallery became operational. This approach stretches the principle too far from its underlying justification, which Lord Carnwath in Coventry v Lawrence located in the public interest:Footnote 133 as Steel emphasised, if the locality principle is justified by the public interest, it must reflect the “entitlements” – not merely the actual expectations – of persons in the area, which evolve when character-defining uses are introduced.Footnote 134 A Fearn-compliant methodology must therefore chart a middle course where such uses are allowed to shape, but not dictate, the locality.

Second, such a middle course requires criteria for determining when an activity should be included in the locality and what weight it should carry. This task is not straightforward: as Lord Neuberger remarked in Coventry v Lawrence, “any attempt to give general guidance on such issues risks being unhelpful or worse”.Footnote 135 Clarifying the concept of “unlawfulness”, which under Coventry v Lawrence constitutes the criterion for exclusion from an assessment of locality, offers a foundation for overcoming this difficulty. To develop this concept in a Fearn-compliant manner, explicit recognition should be given to the loose sense in which it was employed by Lord Neuberger in Coventry v Lawrence. As explained in Section II(A), “unlawfulness” under Coventry v Lawrence did not extend to all activities prohibited by law, nor was it limited only to prohibited activities.Footnote 136 This loose formulation leaves space for future, Fearn-compliant development. The direction of development, it is suggested, should be towards shaping “unlawfulness” around the kinds of activities that the claimant, as a member of their particular community, is entitled to expect to be carried out, and not to be carried out, in their vicinity.

On this view, activities in breach of planning controls should be excluded because communities are entitled to expect compliance with determinations of their local planning authorities. Activities amounting to a nuisance to any neighbour (and not solely to the claimant) should be excluded, because communities can expect not to suffer tortious conduct. Where a singular, predominant use reshapes an area, whether it is included from the locality should depend on the degree to which that community is entitled to expect continuity of its existing character: no community is immune to change, but the pace of change that different communities are entitled to expect will vary.

As to weight, criteria should be set out reflecting the scale, permanence and integration of activities within the area’s overall patterns of use. A single house among factories does not alter a locality, but a single football stadium within a residential neighbourhood might do so. This again ties back to community expectations: a stadium (and perhaps a public viewing gallery) fundamentally recalibrates expectations of what must be tolerated in ways that smaller-scale, less integrated or temporary uses do not.

The third task for a Fearn-compliant methodology is to develop a normative anchor for the locality exercise, which aligns with the majority’s exclusion of public interest considerations from liability. After Coventry v Lawrence, Steel persuasively argued that “the only plausible justification of [a broad locality] principle rests upon considerations that go beyond the interests of the individual parties”.Footnote 137 But, as the majority in Fearn v Tate Gallery rejected the public interest as irrelevant to liability, a revised framing is needed.

One answer, it is suggested, lies in reorienting the concept of “reciprocity”. In Fearn v Tate Gallery, Lord Leggatt invoked the “principle of reciprocity” as the explanation for prioritising ordinary use.Footnote 138 He traced the principle to Southwark L.B.C. v Mills, where reciprocity was framed as being concerned with “show[ing] consideration” for one’s neighbour and “expect[ing]” consideration in return.Footnote 139 The picture painted here is one of mutual vulnerability: the parties must accept constraints on their use of land because they depend on the coexistence of others in adjacent spaces. But in Fearn v Tate Gallery, Lord Leggatt instead emphasised mutual demand: “people cannot fairly demand of others behaviour which they would not […] allow others to demand of them”.Footnote 140 This conceptualisation struggles to capture relationships between qualitatively different uses. Residents of adjacent flats, who engage in equivalent residential uses, may make reciprocal demands to tolerate everyday noise. But in Fearn v Tate Gallery, it is not a strong argument to say that the defendant made any demands on the claimants equivalent to the claimants’ demands on them: the gallery would not, under the principles established in that decision, have any right to demand that neighbouring flat owners refrain from allowing members of the public into their flats to gaze into the viewing gallery.Footnote 141

Reorienting reciprocity away from mutual demand, towards shared vulnerability arising from interdependence within shared spaces, allows the concept to scale from bilateral, equivalent uses, to community-level, qualitatively different uses in mixed-use environments. A focus on vulnerability frames reciprocal expectations not only around what parties demand of each other, but around what community members implicitly agree to tolerate for coexistence. This conception can guide which activities should count towards locality, what weight they should carry and how locality can remain responsive to both continuity and change in modern environments.

B. Coming to the Nuisance

In the aftermath of Coventry v Lawrence, Lord Neuberger’s five-stage defence based on temporal priority received little support in the scholarship.Footnote 142 Lee described it as “slightly odd” to reject coming to the nuisance as a defence, while “simultaneously creat[ing] an exception […] so great that it almost overwhelms the rule”.Footnote 143 Kennefick raised a more fundamental objection: Lord Neuberger’s formulation “encroaches in an unprincipled way on easements” because it “behaves like a servitude” but “transcends the limits placed on servitudes by the law of property”.Footnote 144 In Coventry v Lawrence, it was accepted that a defendant could, in certain circumstances, acquire an easement to carry on an activity otherwise amounting to a nuisance, by doing so for 20 years without objection.Footnote 145 By contrast, as Kennefick observes, Lord Neuberger’s coming to the nuisance applies to a broader class of interferences, requires only minimal priority in time and can be invoked by or against a wider class of persons than prescriptive easements.Footnote 146 For Kennefick, these conflicts mean that Lord Neuberger’s formulation “should not be followed”.Footnote 147

At the time of Coventry v Lawrence, this position would have been desirable, given the novelty of Lord Neuberger’s approach and its significant departure from previous authorities. It is necessary to emphasise, however, that under Coventry v Lawrence, temporal priority could still be absorbed into the overarching “unreasonableness” inquiry, irrespective of the status of coming to the nuisance. In Kennaway v Thompson, for example, the defendant’s pre-existing activity was deemed lawful because the claimant “decided to build a house” nearby, which was taken to signify that “she thought that the noise […] was tolerable” at the time.Footnote 148 This illustrates that temporal priority could influence liability without a distinct defence of coming to the nuisance. Steel went further, suggesting that courts should, within the unreasonableness assessment, accord to the defendant’s interest “extra weight” if their activity predated the claimant’s.Footnote 149 Such approaches were possible because, in Coventry v Lawrence, liability in nuisance was governed by an unreasonableness standard capable of accommodating varied considerations.

Fearn v Tate Gallery altered this structure. By rejecting unreasonableness as the governing standard, the majority left coming to the nuisance as the only available mechanism for recognising temporal priority. To reject the defence now would be to hold that a defendant’s priority in time is wholly irrelevant to liability. That position is untenable for two reasons.

First, coming to the nuisance is necessary to counterbalance the locality inquiry. If a single new use can sometimes change the character of a locality and thereby create liability, then a single pre-existing use should also sometimes be able to avoid liability. The locality principle creates a notable break in this symmetry. As Bagshaw observes, ordinariness in the locality applies differently to claimants and defendants: it “sets the level of interference at which a claimant can complain”, while acting as a “condition” that a defendant must satisfy to escape liability.Footnote 150 In other words, a claimant’s non-ordinary use does not bar their claim if an ordinary use would also suffer substantial interference. But a defendant’s non-ordinary use always bars their defence, even if an ordinary use would likewise have caused substantial interference.

Under the locality principle, the introduction of a new use can either change or not change the character of its locality. If it changes the locality, the consequences are symmetrical whichever party effects the change: liability arises if the claimant changes the locality and liability is avoided if the defendant does so. But if the change does not alter the locality, the consequences are asymmetrical. A first-in-time claimant succeeds whether or not their use is ordinary (as long as an ordinary use would have suffered substantial interference). A first-in-time defendant, however, escapes liability only if their use is ordinary (even if an ordinary use would have caused substantial interference). Without a counterweight, this asymmetry is problematic: it should be possible to treat with parity changes of use by claimant and defendant.Footnote 151 Coming to the nuisance provides that counterweight by allowing the defendant’s temporal priority to matter at the liability stage.

The second reason is that Fearn v Tate Gallery leaves no mechanism for dealing with intensification unless the defendant’s temporal priority can be considered. The facts of Kennaway v Thompson again illustrate this problem. The defendant boat-racing club operated a number of boats near the claimant’s land. After the claimant built a house, the defendant gradually introduced more boats, resulting in intensifying noise. It was held that, although boat-racing was consistent with the locality, the increasing number of boats made the noise interference unreasonable. As explained in Section III(A), this reasoning is now precluded by Fearn v Tate Gallery’s rejection of unreasonableness and near-determinative use of locality. Under Fearn v Tate Gallery, courts face a binary choice: boat-racing is either ordinary in the locality such that no part amounts to a nuisance or it is unusual such that all activities which cause a substantial interference are a nuisance. The possibility of a more nuanced solution, which treats as a nuisance only the intensified part of the substantial interference, is desirable. Such a solution requires a mechanism for acknowledging priority in time and coming to the nuisance is the only one that remains.

Accordingly, Fearn v Tate Gallery makes it necessary to accept some version of coming to the nuisance, not only to allow defendants to escape liability altogether, but also to enable courts to distinguish between baseline and intensified activities.Footnote 152 The challenge is to clarify the doctrine in a way that balances temporal priority against competing considerations, while avoiding the incoherences with property law identified by Kennefick.

A first step is to emphasise the features distinguishing coming to the nuisance from prescriptive easements. The core distinction, it is suggested, is that prescription is not generally concerned with priority in time, whereas priority in time constitutes the central concern underlying coming to the nuisance. It is possible to acquire certain kinds of easements via temporal priority: easements of light, for example, may arise from the continued existence of a window for 20 years. However, as Lord Hoffmann observed in Hunter v Canary Wharf, easements of light are unusual because, “[i]n the normal case of prescription, the [dominant] owner will have been doing something for the period of prescription […] which the servient owner could have stopped”.Footnote 153 In other words, easements to engage in an activity can be acquired prescriptively only if the claimant could have stopped that activity for the full 20 years. This would be the case only if the claimant, or their predecessor in title, was also, for the whole period, using their land in a way so substantially interfered with as to amount to a nuisance.Footnote 154 As such, a prescriptive easement does not arise because the defendant’s activity is first-in-time; it arises because both parties have been using their land incompatibly for a sufficiently (and equally) long period. In this light, the core distinction between coming to the nuisance and prescriptive easements is that the former is generally underpinned by priority in time while the latter is not.

For this reason, Lord Neuberger’s second criterion – that the defendant’s activity must not have been a nuisance before the claimant’s change of use – is crucial. It should be interpreted as requiring the absence of nuisance to anyone, not merely the claimant. Such an interpretation ensures that the doctrine applies only to activities that are objectionable solely because the claimant changed their use of land and it avoids protecting activities already unlawful vis-à-vis other neighbours.

In addition, the fifth criterion – that the defendant’s activity must cause no greater nuisance than at the time of change – should be refined to target intensification. A greater nuisance may result from many factors, including increased claimant sensitivity. The criterion, however, should capture only aggravations resulting from intensification of the defendant’s activity. As the preceding paragraphs show, a major function of coming to the nuisance post-Fearn v Tate Gallery is to enable courts to fix lawful baselines above the threshold of substantial interference, while still imposing liability for later intensification. Lord Neuberger’s fifth criterion should be configured to perform precisely this function.

Finally, the relevant time for assessing intensification should be the moment when the claimant begins their changed use or building works, not when they file a planning application. A planning application does not change the use of land. At that stage, the possibility of later conflict is only hypothetical: planning applications may be refused, never implemented or implemented years later. As Lord Leggatt noted in Fearn v Tate Gallery, it is “not desirable to have litigation about possible future conflicts that may never actually occur”;Footnote 155 it is equally undesirable to allow potentially speculative planning applications to freeze the permissible level of neighbouring activities.

C. Remedies

As Section II(C) explained, a central uncertainty created in Coventry v Lawrence concerns the exercise of remedial discretion, particularly the relevance and weight of public interest considerations. To address this, Lee proposed that courts should approach the public interest by examining the process by which planning and regulatory decisions were made: asking who made the decision, with what expertise, on what evidence and who was consulted.Footnote 156 Examining these factors, Lee argued, would provide a more “robust picture of the […] public interest”, enabling “that interest to be confidently taken into account in private nuisance”.Footnote 157

Fearn v Tate Gallery transforms the terrain on which public interest considerations enter nuisance: as Section III(B) showed, the majority shifted into the remedies stage factors which were previously (also) relevant to liability. The remedies inquiry must now do significantly more work: it must absorb the entirety of the public interest dimension of nuisance. A Fearn-compliant methodology must therefore take Lee’s concern even more seriously and it must provide a principled way to conceptualise and substantiate public interest considerations, which fits wholly within the remedies framework.

Two avenues are suggested here. First, attempts should be made to distinguish claimant-sided and defendant-sided public interests more carefully, and more thought should be given to how the former can be accommodated within Fearn v Tate Gallery. As Lee notes, public interest arguments are typically defendant-led; “there is little sign of collective interests […] being used to justify enhanced protection of claimants”.Footnote 158 Fearn v Tate Gallery exacerbates this imbalance. When, under Coventry v Lawrence, public interest considerations went to “unreasonableness”, claimants could counter defendant-sided social and economic interests, with interests such as environmental protection. However, as Section II(C) explained, the remedies stage is structurally ill-suited to handling conflicts between different kinds of public interests: the refusal of an injunction fully vindicates defendant-sided interests (the defendant’s activity continues and the defendant’s employees keep their jobs), whereas granting an injunction rarely advances claimant-sided interests beyond the boundaries of the claimant’s own right (other neighbours, and the wider environment, seldom benefit). Because injunctions are tailored to the claimant’s property interest, they are a poor vehicle for giving effect to broader community and environmental concerns. Fearn v Tate Gallery’s exclusion of public interest considerations from liability forces reconsideration of how, and how far, such considerations should influence remedies: the sole gateway through which public interest factors can now enter nuisance is structurally incapable of according equal weight to both sides of the dispute.

One step in this direction may be to clarify the full spectrum of possible remedies. As Section II(C) explained, Lord Neuberger thought that public interests should carry most weight in cases where an injunction would force the defendant’s activity to close. But nuisances can often be mitigated by measures stopping short of closure, including improved insulation, reduced hours or lower intensity of operation.Footnote 159 A Fearn-compliant approach should move away from a binary “injunction versus damages” mindset, towards emphasising more nuanced possibilities, including partial injunctions combined with damages. Where a defendant successfully establishes a public interest argument, the key question should not be whether that argument displaces the presumption of injunction in favour of damages. Rather, it should be whether an injunction can be framed in terms sufficient to remove the nuisance without jeopardising the relevant public interest (for example, by limiting hours or mandating improved insulation). Only if this question is answered in the negative should damages in lieu of an injunction be considered. Even then, partial injunctions supplemented by damages should be considered where this would reduce the interference while preserving the defendant’s proven public interest.

A further complexity arises where mitigation cannot, or cannot efficiently, be carried out on the defendant’s own land, but requires works to the claimant’s property. Fearn v Tate Gallery itself illustrates this point: the nuisance could have been eliminated by installing privacy film on the claimants’ windows, which would have prevented inward viewing without reducing the claimants’ own light or views.Footnote 160 Lord Sales, in his dissent, saw no reason why the possibility of such mitigation should not inform unreasonableness and therefore liability.Footnote 161 However, the majority’s rejection of that standard removes this route and indeed Lord Leggatt rejected it expressly.Footnote 162 The result is that a defendant’s failure to adopt protective measures renders their use non-ordinary and therefore unlawful, while a claimant’s failure to adopt inexpensive, effective protection is irrelevant. By sweeping this factor away from the liability stage, the majority’s approach in Fearn v Tate Gallery necessitates a remedies framework capable of accommodating it.

The second task for a Fearn-compliant remedies framework is therefore to take account of the possibility of resolution through protective measures on the claimant’s land. This requires several clarifications to the uncertainties underlying Coventry v Lawrence. The starting point is to clarify that public interest considerations favouring the defendant should carry significant weight not only where an injunction would force closure, but also where the nuisance can be eliminated by works on the claimant’s land without materially reducing enjoyment. In such cases, the availability of claimant-sided mitigation should weigh against an injunction and in favour of damages in lieu thereof.

The next step is to clarify quantification. As Section II(C) explained, Coventry v Lawrence left uncertain the proper basis for calculating damages in lieu of an injunction: the justices accepted diminution in value of the claimant’s land as a starting point, but they left open the possibility of upward departures from this starting point. In light of Fearn v Tate Gallery, it should be clarified that the appropriate figure may, where justified, also fall below diminution in value. As Bagshaw explains, the only Fearn-compliant ways to bring about an outcome where the defendant funds remedial works on the claimant’s land are the “negotiation of a settlement” or the court’s refusal of an injunction and award of “a sum of damages […] equal to the cost of the work”.Footnote 163 The reasoning in Coventry v Lawrence does not make explicit that damages can be quantified in accordance with the cost of remedial works and this uncertainty should be resolved in the affirmative.

V. Conclusion

This article examined three areas of uncertainty created by the Supreme Court’s decision in Coventry v Lawrence: the locality principle, coming to the nuisance and remedies. The subsequent decision in Fearn v Tate Gallery was shown to necessitate a reconsideration of these uncertainties. Possible paths towards the development of Fearn-compliant solutions were suggested, focusing on the articulation of workable criteria for locality, a principled role for temporal priority and a remedial framework capable of accommodating considerations displaced from the liability stage. It was argued that a Fearn-compliant locality principle should be capable of recognising singular but large-scale uses as locality-defining; and that a version of coming to the nuisance capable both of informing liability and of addressing intensification, should be accepted. Finally, it was suggested that the remedial framework, and the role of the public interest within it, should be developed with proper account for the full range of possible measures for eliminating and mitigating a nuisance.