Introduction

Classical biological control (hereafter, biocontrol) can provide cost-effective, landscape-level control for invasive insect pests in forests (Kenis et al. Reference Kenis, Hurley, Colombari, Lawson, Sun and Wilcken2019; but see MacQuarrie et al. Reference MacQuarrie, Lyons, Seehausen and Smith2016). The release of specialist natural enemies (biocontrol agents) such as predators, parasitoids, or pathogens sourced from the pest’s native range aims to regulate invasive populations within the pest’s new range. In the long term, biocontrol can offer a self-sustaining complement to other integrated pest management tools, such as chemical or silvicultural control, which may be insufficient in reducing pest damage below economically or ecologically acceptable levels or are not feasible over large areas (Davidson and Rieske Reference Davidson and Rieske2016; Archer et al. Reference Archer, Crane and Albrecht2022). Because biocontrol involves the introduction of nonnative species into the invaded region (Huffaker et al. Reference Huffaker, Simmonds, Laing, Huffaker and Messenger1976), its risks and benefits must be carefully considered before implementation (Abram et al. Reference Abram, Franklin, Brodeur, Cory, McConkey, Wyckhuys and Heimpel2024). In cases of shared invasive pests, a biocontrol programme developed and applied in one invaded region can be adapted for use in a similar ecoregion affected by the same pest, along with the benefits of drawing on existing knowledge and expertise (Lyons Reference Lyons, Mason and Gillespie2013). However, the ecological context unique to the novel invaded region may warrant additional assessments to ensure the programme’s success and efficacy (Stastny et al. Reference Stastny, Corley and Allison2025). For example, predation by the natural enemy complex already present in the newly invaded region may differ from that in other regions, with potential implications for the level of mortality required by the biocontrol agents to achieve pest control, as well as their interactions with the resident natural enemies. The life cycle of the target pest in the newly invaded region relative to its phenology in its native range or in other invaded regions must also be examined to inform the selection and, ultimately, the sourcing and releasing methods of biocontrol agents (Huffaker et al. Reference Huffaker, Simmonds, Laing, Huffaker and Messenger1976; Crimmins et al. Reference Crimmins, Gerst, Huerta, Marsh, Posthumus and Rosemartin2020; Barker and Coop Reference Barker and Coop2023; Dorman et al. Reference Dorman, Kaur, Anderson, Sim, Tanner and Walenta2024). Collectively, this basic research guides the initiation and optimisation of a biocontrol programme and establishes the foundation for further monitoring to evaluate the establishment, spread, and efficacy of biocontrol agents.

A recent damaging invasive forest pest in eastern Canada (Canadian Food Inspection Agency 2017), the hemlock woolly adelgid, Adelges tsugae Annand (Hemiptera: Adelgidae), is an aphid-like insect native to Japan and other parts of eastern Asia, as well as to the Pacific Northwest, that threatens hemlock, Tsuga spp. Carrière (Pinaceae), in eastern North America (McClure Reference McClure1987; Orwig et al. Reference Orwig, Thompson, Povak, Manner, Niebyl and Foster2012; Abella Reference Abella2018). Even before its discovery in eastern Canada, A. tsugae had been spreading in the eastern United States of America since the mid-20th century and now occurs in that country from northern Alabama to Maine and west into Kentucky, Michigan, and Ohio (United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service 2024). This region is marked by widespread decline and mortality of both eastern hemlock, Tsuga canadensis (Linnaeus) Carrière, and the endemic Carolina hemlock, T. caroliniana Engel (Orwig et al. Reference Orwig, Thompson, Povak, Manner, Niebyl and Foster2012; Limbu et al. Reference Limbu, Keena and Whitmore2018). An ecological foundation species, eastern hemlock provides specialised habitats for biodiversity (Rohr et al. Reference Rohr, Mahan and Kim2009; Ingwell et al. Reference Ingwell, Miller-Pierce, Trotter and Preisser2012) and plays integral roles in nutrient and hydrological cycling, as a frequent component of riparian corridors, and in carbon sequestration (Holmes et al. Reference Holmes, Murphy, Bell and Royle2010; Li et al. Reference Li, Preisser, Boyle, Holmes, Liebhold and Orwig2014). The loss of hemlock due to A. tsugae has significant consequences on associated fauna, including fish (Ross et al. Reference Ross, Bennett, Snyder, Young, Smith and Lemaire2003), amphibians (Siddig et al. Reference Siddig, Ellison and Mathewson2016; Ochs and Siddig Reference Ochs and Siddig2017), birds (Tingley et al. Reference Tingley, Orwig, Field and Motzkin2002), and mammals (Yamasaki et al. Reference Yamasaki, DeGraaf, Lanier, McManus, Shields and Souto2000; Degrassi Reference Degrassi2018). Considerable investments in research and implementation of multiple integrated pest management tactics have been dedicated to mitigating these ecological impacts in the United States of America (Aukema et al. Reference Aukema, Leung, Kovacs, Chivers, Britton and Englin2011; Mayfield et al. Reference Mayfield, Bittner, Dietschler, Elkinton, Havill and Keena2023). Although effective in local or targeted applications, chemical control using systemic neonicotinoid insecticides is feasible only at the scale of select hemlock stands and may pose environmental risks to other organisms (Sweeney et al. Reference Sweeney, Thompson and Popescu2021; Edge et al. Reference Edge, Heartz, Lagalante, Lewis and Sweeney2025). Over the last two decades, in particular, biocontrol involving multiple species has been increasingly implemented in integrated pest management programmes to manage A. tsugae across forested landscapes in the United States of America (Mayfield et al. Reference Mayfield, Bittner, Dietschler, Elkinton, Havill and Keena2023).

In eastern Canada, A. tsugae was first detected in southern Ontario in 2012, where it has since become established in multiple locations (Canadian Food Inspection Agency 2024). In 2017, the pest was discovered in five counties of southwestern Nova Scotia, Canada (where it likely was introduced up to a decade earlier) and has since spread rapidly across the southwestern portion of the province up to and including Halifax County (Canadian Food Inspection Agency 2024). Although detection of incipient populations of A. tsugae is difficult, given its cryptic nature and parthenogenetic reproductive process, its invasion in eastern Canada has proceeded at a pace comparable to that observed in the United States of America (MacQuarrie et al. Reference MacQuarrie, Gray, Bullas-Appleton, Kimoto, Mielewczyk and Neville2025), with populations rebounding quickly from near-complete mortality during severe cold spells (MacQuarrie et al. Reference MacQuarrie, Derry, Gray, Mielewczyk, Crossland and Ogden2024). In Nova Scotia, A. tsugae has caused significant hemlock decline and mortality in 85 000 ha of forest to date (J.O., unpublished data), suggesting the symptoms and rate of tree impacts are similar to those seen in the northeastern United States of America (Orwig et al. Reference Orwig, Foster and Mausel2002). The pest presents a serious threat to hemlock and its ecological and cultural value throughout most of its range in eastern Canada (Emilson et al. Reference Emilson, Bullas-Appleton, McPhee, Ryan, Stastny and Whitmore2018; Emilson and Stastny Reference Emilson and Stastny2019). Proactive adoption of the integrated pest management approaches that have been used to manage the pest in the United States of America offers an opportunity to expedite their implementation in Canada, potentially contributing to earlier mitigation of ecological impacts (Emilson et al. Reference Emilson, Bullas-Appleton, McPhee, Ryan, Stastny and Whitmore2018). However, gaps remain in the basic knowledge of the pest’s ecology and life cycle in the recently invaded range.

Hemlock in the eastern United States of America (and, presumably, eastern Canada) is highly susceptible to A. tsugae due to a lack of specialist predators of A. tsugae (McClure Reference McClure1987; Wallace and Hain Reference Wallace and Hain2000) and tree resistance (Oten et al. Reference Oten, Merkle, Jetton, Smith, Talley and Hain2014; but see Kinahan et al. Reference Kinahan, Grandstaff, Russell, Rigsby, Casagrande and Preisser2020). Interestingly, A. tsugae also exists as a distinct, native strain in the Pacific Northwest, where it causes minimal damage to hemlock (McClure Reference McClure1987; Havill et al. Reference Havill, Shiyake, Lamb, Footitt, Yu and Paradis2016). In that region, top–down regulation by native predators has been invoked as a significant driver of population dynamics of A. tsugae (Mausel et al. Reference Mausel, Kok and Salom2017; Crandall et al. Reference Crandall, Lombardo and Elkinton2022). Beginning in 1992, long-term management of the invasive A. tsugae has centred on the releases of multiple species of specialist predators from its native ranges, including Japan, China, and the Pacific Northwest (Havill et al. Reference Havill, Shiyake, Lamb, Footitt, Yu and Paradis2016; Mayfield et al. Reference Mayfield, Bittner, Dietschler, Elkinton, Havill and Keena2023). This biocontrol programme was preceded by research that demonstrated that population regulation by resident natural enemies in the invaded range in the eastern United States of America was insufficient (McClure Reference McClure1987; Montgomery and Lyon Reference Montgomery, Lyon, Salom, Tigner and Reardon1995; Wallace and Hain Reference Wallace and Hain2000). The rapid spread and impacts of A. tsugae on hemlock in Nova Scotia strongly imply a similar lack of population regulation by resident natural enemies, but this has not been investigated.

A critical factor in the effectiveness of a biological control programme is the synchronisation of the biological control agents’ development with that of the target pest in the invaded range (Godfray et al. Reference Godfray, Hassell and Holt1994; Van Nouhuys and Lei Reference Van Nouhuys and Lei2004; Hicks et al. Reference Hicks, Aegerter, Leather and Watt2007; Abell et al. Reference Abell, Bauer, Miller, Duan and Van Driesche2016). Quantification of the target’s development in the invaded range is essential because the timing and duration of various life stages may vary from those observed in the insect’s native range (Wolkovich and Cleland Reference Wolkovich and Cleland2011). Leading to its biocontrol programme in the United States of America, the phenology of A. tsugae was examined extensively both in the Pacific Northwest (hereafter, “native range” for the purposes of this paper) and in the eastern United States (McClure Reference McClure1987; Gray and Salom Reference Gray, Salom, Salom, Tigner and Reardon1996; Zilahi-Balogh et al. Reference Zilahi-Balogh, Humble, Lamb, Salom and Kok2003; Joseph et al. Reference Joseph, Mayfield, Dalusky, Asaro and Berisford2011; Dietschler et al. Reference Dietschler, Bittner, Lefebvre, Schmidt, Jubb and James2024). However, given the distinct climate of the invaded areas in Nova Scotia, the timing of A. tsugae life stages can be expected to differ from those reported elsewhere. These differences in phenology can have important implications for several components of integrated pest management, including monitoring, regulation, and active management. For instance, information on pest phenology helps substantiate regulatory actions by identifying high-risk periods, such as when mobile crawler stages are present. Similarly, control treatments must be applied during the appropriate developmental stage to exert population regulation, particularly in the case of biological control that uses specialist predators and parasitoids (Gray Reference Gray2016; Crimmins et al. Reference Crimmins, Gerst, Huerta, Marsh, Posthumus and Rosemartin2020; Barker and Coop Reference Barker and Coop2023). Monitoring of the pest’s development also offers insights into its population factors, such as those associated with mortality and growth, and interactions with the host tree and native fauna. Accurate phenological information on A. tsugae in Nova Scotia is therefore essential for the selection, sourcing, and release of specialist natural enemies in this region, as well as for informing effective regulatory parameters on movement.

Here, we present the results of a multi-year study evaluating three objectives to gain foundational knowledge about A. tsugae in its novel invaded range in Nova Scotia. We conducted a series of field experiments with caged hemlock branches that excluded potential resident predators to evaluate their effects on the mortality of A. tsugae. In parallel, we characterised the existing complex of resident natural enemies by sampling infested hemlock foliage at different periods in A. tsugae development in heavily infested hemlock stands. Finally, we collected detailed information on the development of A. tsugae in Nova Scotia over multiple years. Our objectives were (1) to determine whether resident natural enemies in Nova Scotia are regulating A. tsugae populations, (2) to identify natural enemies within this complex, and (3) to provide phenological information to guide the sourcing and release of biocontrol agents.

Methods

Study system

In eastern North America, the annual life cycle of A. tsugae consists of two parthenogenetic generations (sistens, progrediens), each developing through three stages (egg, four nymphal instars, and adult). For most of its life, the insect lives permanently attached to twigs inside a secreted waxy covering called an ovisac, where the adelgid lays its eggs (McClure Reference McClure1987). In the spring, hatched sistens crawlers (first-instar nymphs) settle on new shoots and enter a summer diapause before resuming feeding and development in autumn. These nymphs continue development over winter and mature in early spring, when the sistens adults lay eggs. Mobile nymphs (“crawlers” of the progrediens generation) that hatch from these eggs actively search for feeding sites near the base of the needles on the previous year’s shoots. Progrediens crawlers are capable of long-distance dispersal at this time of year, including on migrating birds (Russo et al. Reference Russo, Elphick, Havill and Tingley2019). In its native range, significant A. tsugae mortality by predatory insects occurs mostly during the adult and egg stages (Mausel et al. Reference Mausel, Kok and Salom2017; Crandall et al. Reference Crandall, Lombardo and Elkinton2022; McAvoy et al. Reference McAvoy, Foley, Barnett, Mays, Dechaine and Salom2024). In eastern North America, A. tsugae can suffer considerable mortality during summer aestivation (McAvoy et al. Reference McAvoy, Régnière, St-Amant, Scheenberger and Salom2017) and especially in winter, following rapid and extreme temperature fluctuations (Trotter and Shields Reference Trotter and Shields2009; MacQuarrie et al. Reference MacQuarrie, Derry, Gray, Mielewczyk, Crossland and Ogden2024). At high infestations on T. canadensis, densities of A. tsugae are physically limited by the availability of preferred feeding locations along available shoots, leading to increasing density-dependent mortality of neonates in both generations, with a progressive reduction in new shoot production as the tree declines (Sussky and Elkinton Reference Sussky and Elkinton2014).

Study sites

The present study was carried out at several sites in southwest Nova Scotia from 2018 to 2022 (Table 1). The sites had advanced infestations of A. tsugae (i.e., 50% or more of trees showing decline symptoms characteristic of A. tsugae infestation), with ovisac densities on branches being either moderate or higher (i.e., > 1 ovisac per cm of twig length). Sites were chosen based on the availability of hemlock branches within 2 m of the ground. All stand types were composed of more than 25% hemlock (> 20 cm diameter at breast height) and consisted of other trees typical of the Acadian Forest Region, including Quercus rubra Linnaeus (Fagaceae), Fagus grandifolia Ehrhart (Fagaceae), Acer rubrum Linnaeus (Sapindaceae), Pinus strobus Linnaeus (Pinaceae), Larix laricina (Du Roi) K. Koch (Pinaceae), Picea rubens Sargent (Pinaceae), and Abies balsamea (Linnaeus) (Miller) (Pinaceae).

Table 1. Sites used for sampling of Tsuga canadensis foliage infested with Adelges tsugae in southwest Nova Scotia. We carried out beat sheet or beat net sampling (Beat sheet, Net) and sleeve cage (sleeve) studies at various sites. PT, start of the sleeve cage study, where a pretreatment sample was taken off each branch. Otherwise, collections were carried out on the month and day (for the same month) indicated below.

§ Samples were pooled by site for the April, May, June, and July collections.

* Due to COVID-19 travel restrictions, only an October collection was possible in 2020 following the March 2020 setup.

Predator exclusion experiments

To evaluate the role of predation by resident natural enemies on A. tsugae in Nova Scotia, we conducted predator exclusion experiments using mesh sleeve cages (1.5 m length, 150-µ mesh) around infested hemlock branches (∼1 m length; Wallace and Hain Reference Wallace and Hain2000). The experiment was repeated in two consecutive years (2020 and 2021) at three sites (Sissiboo, Weymouth Falls, and Wentworth Lake; Table 1) and in 2022 at three new sites. In 2022, we changed experimental locations (Table 1) because of widespread hemlock decline caused by A. tsugae at the 2020–2021 study sites. In all experiments, we paired caged hemlock branches with open (uncaged) branches; each pair of branches was located on the same tree or on trees within 3 m of each other. Before installing the sleeve cages in early spring or late fall, we shook the branch to dislodge potential predators, then sealed the cage around the base of the branch using a plastic zip-tie. All experiments began with a pretreatment assessment of the initial density of live A. tsugae (third-instar nymphs in fall and fourth-instar nymphs in spring) on all branches before installing cages in late fall or early spring each year. After cage installation, we sampled all branches four distinct times during the spring and summer months: twice during each of the predicted peaks of progrediens and sistens egg stages, respectively, at two- to three-week intervals except in 2020 (see next paragraph).

In November 2019, we selected 20, 30, and 15 pairs of branches that were moderately to heavily infested by A. tsugae (i.e., three or more ovisacs per centimetre of twig) at each of the three sites, respectively. In the spring and summer of 2020, COVID-related travel restrictions prevented twig sampling during the peak oviposition periods. Instead, we sampled in March and October of 2020 (when this year’s experiment ended). In late March 2021, we set up 10 pairs of branches at the same sites but selected new trees with lower densities of A. tsugae (i.e., ≤ 1 ovisac per centimetre of twig length) because we found that selecting more heavily infested branches resulted in branch dieback in both treatments by the end of the 2020 season. In 2021, COVID-related travel restrictions necessitated site visits by a local contractor (Mersey Tobeatic Research Institute, Caledonia, Nova Scotia), who subsampled branches haphazardly by removing a subterminal twig at the appropriate sampling times and shipping them to the Atlantic Forestry Centre quarantine laboratory (Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forestry Service; Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada) for processing.

In 2022, we set up 11, 12, and 15 pairs of branches at the Bloody Creek, Annapolis Royal, and McKay Lakes sites, respectively. In all three years, we collected a twig sample (25 cm length) from all branch tips. Except as noted above, we collected twig samples before treatment and twice (i.e., 2–3 weeks apart) during the peak oviposition period of the A. tsugae sistens and progrediens adult stages. Twig samples were kept at 4 °C until they could be processed, usually within 2–4 weeks of collection, except in 2020 (within two months of collection, due to COVID-related work restrictions).

For all twig samples, we counted the number of ovisacs on the 12 most distal current-year (new growth) shoots or one-year-old twigs per branch, or until approximately 100 ovisacs had been counted. We also measured the length of each twig to determine the density of intact ovisacs containing live A. tsugae per centimetre of twig length. Outside of the egg periods of A. tsugae, we differentiated between live and dead A. tsugae nymphs based on movement (i.e., leg movement or peristalsis). To facilitate this assessment, samples were placed at room temperature the night before being processed. During the egg periods of A. tsugae, we recorded any adult that was moving or had produced eggs in an intact ovisac as “live.” We counted the total live A. tsugae on a subsample of the branch tips in 2020 (i.e., sistens sample 3) and in 2021 (i.e., sistens sample 1). Only replicates with intact (undamaged) cages at the time of assessment were included in the analyses.

Because the level of infestation affects tree growth, the relative health of the sampled branches varied among trees. For example, some branch tips had ample new shoots, whereas others had none. When adelgids settle on portions of twigs that are older than the preferred current growth, their survival is significantly decreased (McClure Reference McClure1991). For this reason, from all clippings, we sampled ovisacs from current-year shoots, with a supplementary assessment of the previous year’s (i.e., one-year-old) twigs if new growth was not available.

Surveys of natural enemies

We employed two complementary methods to examine the diversity and abundance of natural enemies found on A. tsugae–infested hemlock foliage in southwest Nova Scotia. The first method relied on dissection of ovisacs on branches collected from the open treatment during the predator exclusion experiment, allowing for detection of arthropods (including immature life stages or puparia) present on the twigs (entire sample) or directly in association with A. tsugae ovisacs (12 most distal current-year – new growth – shoots or one-year-old twigs, inspecting up to approximately 100 ovisacs; see above). The second method involved beating foliage to dislodge and collect arthropods several times throughout the year, as described below. Samples of potential natural enemies were put in 95% ethanol until they could be identified.

Beat sheet sampling

This method consisted of placing a 1-m2 beat sheet underneath two hemlock branch tips (∼1 m2 of foliage) per tree and vigorously striking the top surface of the branch tips 5–6 times with a PVC rod to dislodge any arthropods present on this foliage (Mausel et al. Reference Mausel, Salom, Kok and Davis2010). However, on one occasion, branches at two sites were sampled using a sleeve cage, instead of a sheet (Wallace and Hain Reference Wallace and Hain2000), wherein we enclosed the distal 1 m of a branch within a mesh sleeve (1.5 m in length, sampling about 0.5 m2 of foliage) and then vigorously shook the branch for 30 seconds to dislodge any arthropods. We collected the arthropods found on the sheet or in the sleeve cage, placing them in 41-mL glass vials filled with 95% ethanol.

Sampling took place at each site several times per year for a two-year period (Table 1). On each visit, we sampled between 10 and 30 trees and from two to four branch tips from each tree, or approximately 2 m2 of hemlock foliage. Samples from Bear River, Sissiboo, and Wentworth Lake in the spring and summer of 2020 were pooled among trees. In the laboratory, we sorted the samples to species where possible, targeting the Coleoptera, Hemiptera, Diptera, Hymenoptera, and Neuroptera because these groups contain most of the natural enemies that may feed on A. tsugae in eastern North America (Montgomery and Lyon Reference Montgomery, Lyon, Salom, Tigner and Reardon1995; Wallace and Hain Reference Wallace and Hain2000; Wantuch et al. Reference Wantuch, Havill, Hoebeke, Kuhar and Salom2019). In addition to the native Laricobius rubidus Leconte (Coleoptera: Derodontidae), we focused on checking for the presence of any specialised adelgid or aphid predators, which we identified to species level where possible, that could be expected to adopt this novel prey, such as coccinellids (Coleoptera) and silver fly larvae (Chamaemyiidae).

Adelgid phenology

The study was conducted at three A. tsugae–infested hemlock stands of similar size, species composition, and infestation severity within the western counties of Nova Scotia: Sissiboo, Bear River, and Wentworth Lake Municipal Park (Table 1) in 2019 and 2020. Sites were spread across southern Nova Scotia and encompassed different climatic conditions. Each site was sampled once in November and in February, biweekly in March, April, September, and October, and weekly from May to August each year, according to anticipated transitions in insect development as have been observed in the northeastern United States of America (Connecticut; McClure Reference McClure1987). At each site and for each sampling date, one branch tip (45 cm length) with A. tsugae was collected from each of 10 randomly selected hemlock trees. All samples were processed the following day. At each visit, up to 50 adelgids per branch tip were examined while focusing on the most current growth available at the time (i.e., up to 500 adelgids per site per visit). The observations were pooled across branches for each site and averaged among sites for each time point.

Statistical analysis

We fit a negative binomial generalised mixed effect linear model (function glmer.nb in R) to compare differences in the density of live, intact A. tsugae ovisacs as the response variable, using branch treatment (caged; open) as a fixed factor and site as a random effect in the model. We analysed each year and collection period separately due to changing protocols for the assessment of twigs as described above; in all cases, analyses for the current-year and previous-year shoots were separate. We fit and tested the assumptions of our models by examining residual plots and dispersion parameters of our models, as described in Zuur et al. (Reference Zuur, Ieno, Walker, Saveliev and Smith2009). Analyses were carried out in the R statistical computing environment, version 3.4.3 (R Core Team 2017). The glmer.nb model was fit using functions in the mass package (Venables and Ripley Reference Venables and Ripley2002). Means were separated using functions in the emmeans package (Lenth Reference Lenth2023).

Results

Predator exclusion experiments

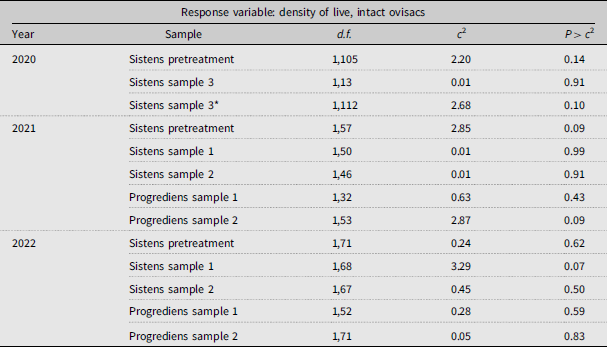

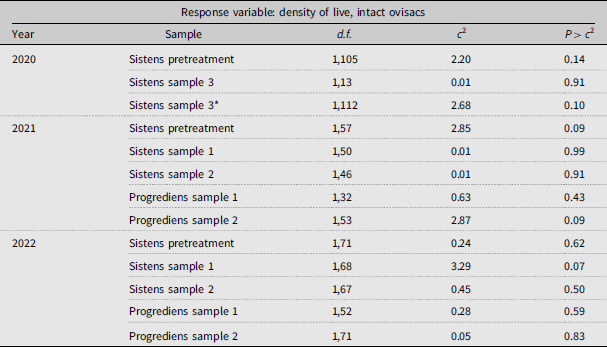

In all three years, the initial, pretreatment density of live A. tsugae on new shoots did not differ significantly between caged and open branch tips (Table 2; Fig. 1). In 2020, the density of live A. tsugae (sistens generation) remained similar between the two treatments for the October sampling period (sample 3). Likewise, at the four sample periods in both 2021 and 2022, the density of live, intact ovisacs on caged branches was similar to those on open branches (Table 2; Fig. 1). We also did not detect differences in density of live A. tsugae between the treatments on one-year-old twigs on the branch tips (Supplementary material, Fig. S1).

Table 2. Effect of the experimental exclusion of predators on the density of live, intact Adelges tsugae ovisacs on current-year shoots of Tsuga canadensis, comparing branch tips enclosed in sleeve cages versus open (uncaged) branch tips (treatment) over multiple sites and sampling periods from 2020 to 2022. Each sampling period was analysed separately (see text for details). Pretreatment samples denote the initial A. tsugae density before branch caging. See Table 1 for details on the timing of sampling. *In 2020, sistens sample 3 involved one-year-old twigs instead, due to a lack of current growth.

Figure 1. Density (number of intact ovisacs containing live A. tsugae per 10 cm of shoot ± standard error) of live, intact Adelges tsugae ovisacs at six sampling points in 2020–2022 on Tsuga canadensis branches in southwest Nova Scotia, Canada, comparing caged (C) branches that excluded predators versus open (O) branches. Grey dots show raw density (jittered for visualisation) per branch tip. Timing of sampling: March for pretreatment sistens in 2020 and March in 2021 and 2022; May and June for sistens samples 1 and 2; July for progrediens samples 1 and 2; October for sistens sample 3. See text for details.

Surveys of natural enemies

Ovisac dissections

We did not find any adult life stages of natural enemies during branch dissections, and we found very few immature specimens. For example, we found 2, 32, and 4 fly larvae in 2020, 2021, and 2022, respectively, including from the caged branches. Most of these larvae (29 of 38) were collected during the A. tsugae sistens egg stage in summer, with the remainder collected during the progrediens egg stage in spring. Six of 38 specimens were identified using DNA barcodes (see Havill et al. Reference Havill, Gaimari and Caccone2018): these comprised five Aphidoletes spp. Kieffer (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) and one Scaptomyza sp. Hardy (Diptera: Drosophilidae) (Nathan Havill, personal communication). The DNA barcoding for the remaining 32 was not successful because of DNA degradation. Four of the Aphidoletes spp. collected in 2021 and identified via molecular methods were entered into GenBank (National Center for Biotechnology Information; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) with the following sequences: PV563528, PV563529, PV563530, and PV563531. The remaining Aphioletes sp. was not assigned a GenBank number at the time of processing, and the Scaptomyza sp. was excluded because this genus does not include predators.

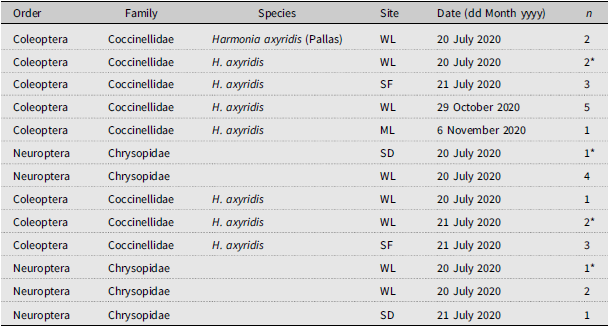

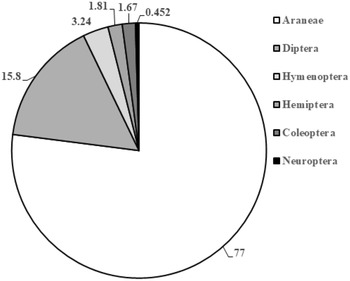

Beat sheet sampling

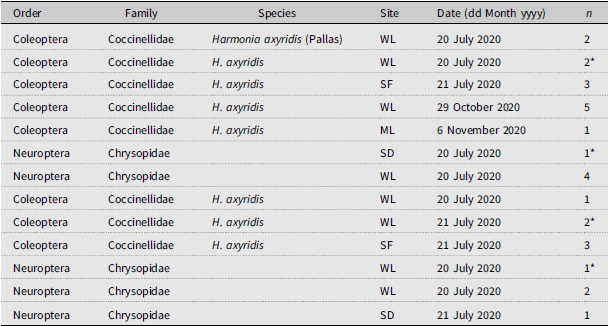

We recovered approximately 2653 arthropod specimens from beat sheet sampling during 2020 and 2021 (Table 3; Fig. 2). Of these, approximately 77% were spiders, with the remainder (∼23%) being insects. Coleoptera and Diptera represented 1.7% and 15.8% of the total arthropods collected, respectively, when data were pooled from 2020 and 2021, whereas Hymenopterans and Neuropterans represented 3.24% and less than 1%, respectively. Our surveys did not detect any specialist predators of adelgids, such as the nonnative Laricobius erichsonii Rosenhauer (Coleoptera: Derodontidae) released repeatedly in the mid-1900s to control the introduced balsam woolly adelgid, Adelges piceae (Ratzeburg), or Laricobius rubidus LeConte, a native predator of the native pine bark adelgid, Pineus strobi (Hartig) (Hemiptera: Adelgidae) (Clark and Brown Reference Clark and Brown1958; Zilahi-Balogh et al. Reference Zilahi-Balogh, Broeckling, Kok and Salom2005). We did not detect any adult chamaemyiids, which in their larval stage are also native predators of P. strobi. Of the notable generalist predators reported from A. tsugae population surveys in the United States of America (e.g., McClure Reference McClure1987; Montgomery and Lyon Reference Montgomery, Lyon, Salom, Tigner and Reardon1995; Wallace and Hain Reference Wallace and Hain2000), we recovered only Harmonia axyridis (Pallas) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) (n = 11; Table 3; Supplementary material, Table S1), and several chysopids (Neuroptera) (n = 10; Table 3; Supplementary material, Table S1).

Table 3. List of insect predators collected using beat sampling (sheet or net) in eastern hemlock stands infested by Adelges tsugae in southwestern Nova Scotia, Canada, in 2020 and 2021. Site locations (see Table 1 for coordinates) are listed using the following abbreviations: WL, Wentworth Lakes; SF, Sissiboo “F”; ML, MacKay Lakes; SD, Sissiboo Dam. Asterisk denotes a specimen that was in larval form at the time of collection; all others were adults; “n” indicates the number of individuals (adults or larva/nymph) collected on the date of sampling.

Figure 2. Arthropods with eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) foliage infested with Adelges tsugae during beat sampling in southwest Nova Scotia, Canada, during 2020 and 2021. Numbers represent the percentage of total arthropods (n = 2653) collected using beat sampling (beat sheet or beat net).

Adelgid phenology

The patterns observed in the timing of development were generally consistent between the 2019 and 2020 datasets; because of this, to better highlight regional phenology, we amalgamated all data into one visualisation (Fig. 3). Adult sistens with eggs (Fig. 3, purple bars) were observed from late April to early July. These eggs gave rise to progrediens crawlers (Fig. 3, black bars), which we observed on foliage from mid-May to mid-July each year. Progrediens developed over a 10-week period, with each instar and adults with eggs overlapping considerably from mid-May to mid-July each year. The sistens crawlers (purple bars) were active from mid-July to late August each year, entering an aestival diapause that lasted until early October. Following this diapause, sistens nymphs developed rapidly in fall, attaining the third-instar stage before the end of December. Adelgids remained as third-instar nymphs until the end of March, when they became fourth-instar nymphs. It took about a month thereafter for adults to appear in the population (Fig. 3). We noted considerable overlap of the egg and crawler stages of the sistens and progrediens generations.

Figure 3. The occurrence of life stages of Adelges tsugae on Tsuga canadensis in southwest Nova Scotia, Canada, averaged across multiple sampling sites for 2019 and 2020; see text for details. The adult stage also includes the egg stage. For reference, triangles indicate the midpoints of the observed occurrence of progrediens and sistens egg stages, respectively, in Connecticut, United States of America (CT; invaded range) and British Columbia, Canada (BC; native range), as reported in McClure (Reference McClure1987) and Zilahi-Balogh et al. (Reference Zilahi-Balogh, Humble, Lamb, Salom and Kok2003).

Discussion

Throughout our predator exclusion experiments, we observed similar densities of live A. tsugae in both open and caged branches, suggesting a dearth of resident natural enemies that have adopted the pest as prey. This observed pattern was consistent among years, sites, and collection periods within each year and was similar to findings from the United States of America (McClure Reference McClure1987; Montgomery and Lyon Reference Montgomery, Lyon, Salom, Tigner and Reardon1995; Wallace and Hain Reference Wallace and Hain2000). Our experiments demonstrate that A. tsugae in southwestern Nova Scotia does not experience sufficient predation by resident natural enemies to prevent deleterious effects on hemlock. Indeed, we had to abandon the sites used in 2020 and 2021 due to severe decline of hemlock canopy (including some tree mortality) under increasing A. tsugae infestations, and we observed similar dynamics at the sites of our phenological and beat sheet sampling (see below). The lack of natural enemies that prey on the two generations of A. tsugae is likely a key factor in the rapid buildup and spread (i.e., 12–13 km per year in Nova Scotia; MacQuarrie et al. Reference MacQuarrie, Gray, Bullas-Appleton, Kimoto, Mielewczyk and Neville2025) of A. tsugae and of subsequent damage to hemlock in southwestern Nova Scotia.

Importantly, our surveys of advanced infestations did not detect any specialist native predators on A. tsugae, despite our study spanning multiple years and multiple sites to account for spatiotemporal fluctuations of predator populations, as suggested by Wallace and Hain (Reference Wallace and Hain2000). This result is surprising, given that two adelgid specialist derodontids, L. rubidus and L. erichsonii, have been recorded from southwest Nova Scotia (Majka Reference Majka2007), and A. tsugae has likely been present in the region for at least a decade (Stastny et al. Reference Stastny, Roscoe, Fidgen, Vankosky and Martel2024). The pine bark adelgid predator, L. rubidus, can complete development on A. tsugae and has been found in association with A. tsugae populations in the eastern United States of America (Zilahi-Balogh et al. Reference Zilahi-Balogh, Broeckling, Kok and Salom2005; Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Brewster, Havill, Salom and Kok2015; McAvoy et al. Reference McAvoy, Foley, Barnett, Mays, Dechaine and Salom2024); L. erichsonii was widely released in Atlantic Canada for biological control of the balsam woolly adelgid (Clark and Brown Reference Clark and Brown1958), although host range information for this species is lacking. Our findings highlight that the absence of specialist natural enemies may partly explain the rapid spread and impacts of A. tsugae in Nova Scotia, similar to the circumstances in the eastern United States of America (Wallace and Hain Reference Wallace and Hain2000). In contrast, A. tsugae appears to be well regulated by predators in the Pacific Northwest (e.g., Lamb et al. Reference Lamb, Salom and Kok2005; Crandall et al. Reference Crandall, Lombardo and Elkinton2022).

We report here a few noteworthy observations from our predator exclusion experiment. First, we did occasionally collect larval Diptera foraging in twig samples of caged branches, indicating that female flies managed to oviposit through the mesh or before its installation. We were able to identify these species through molecular diagnostics of six specimens: five of these were Aphidoletes spp., and one was Scaptomyza sp. Wallace and Hain (Reference Wallace and Hain2000) had recovered Aphidoletes spp. as both adults and larvae in Virginia, United States of America, although numbers of both were low. One species, Aphidoletes thompsoni (Möhn), was released in eastern Canada as a biological control agent for A. piceae in Nova Scotia in 1966 and 1967, although no measurable effect on A. piceae was recorded (Schooley et al. Reference Schooley, Harris, Pendrell, Kelleher and Hulme1984). In most instances when we found fly larvae within the cages, it was in areas already sustaining heavy impacts from A. tsugae. We did not observe fly larvae preying on live A. tsugae. Second, we observed that twig samples from caged branches appeared to be healthier than those from open branch tips. We suspect the cages prevented immigration from A. tsugae crawlers dispersing from the canopy and thus greatly reduced the propagule pressure on these replicates. Lastly, when cages were left in place for an extended period (2020), we did not see differences in the density of A. tsugae on caged and open branches (Figs. 2 and 3), suggesting that the physical effect of the cages did not have a major influence on the outcomes.

Our surveys of arthropod communities in infested hemlock stands in southwest Nova Scotia, using beat sheet sampling as a complementary method to detect dominant and relatively host-specific natural enemies, yielded primarily generalist and opportunistic predators. The majority (77%) of these were spiders, which are increasingly recognised as an important source of generalist predation of forest insect pests (Riechert Reference Riechert1999; Bowden et al. Reference Bowden, van der Meer, Moise, Johns and Williams2023). Although spiders have not yet been shown to suppress populations of A. tsugae, ascertaining their possible direct or indirect effects (via consumption of A. tsugae or of biocontrol agents, respectively) may increase our understanding of A. tsugae population regulation (Mallis and Rieske Reference Mallis and Rieske2011). The next most common group of natural enemies that were collected were Diptera (16% of all arthropod specimens), primarily as larvae and adults, but we found no adelgid specialist dipteran or coleopteran predators (< 2.0% of individuals collected). Both Laricobius rubidus and La. erichsonii are adelgid specialists found in Nova Scotia (Majka Reference Majka2007), with La. rubidus observed to both feed and complete development on A. tsugae in both lab and field studies (Zilahi-Balogh et al. Reference Zilahi-Balogh, Broeckling, Kok and Salom2005; Story et al. Reference Story, Vieira, Salom and Kok2012). The most common coleopteran predator that we collected was H. axyridis. Harmonia axyridis, a ubiquitous, introduced polyphagous predator of aphid and coccid species, has been recovered during A. tsugae natural enemy surveys and field experiments in the United States of America (Wallace and Hain Reference Wallace and Hain2000; Mausel et al. Reference Mausel, Salom, Kok and Fidgen2008). Although observed to feed on both A. tsugae sistens ovisacs and adults (Flowers et al. Reference Flowers, Salom and Kok2005), H. axyridis’s regulation of A. tsugae populations in field evaluations is minimal (Mausel et al. Reference Mausel, Salom, Kok and Fidgen2008; but see Flowers et al. Reference Flowers, Salom and Kok2006). Similar to other surveys, we recorded the presence of adult lacewings (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) (McClure Reference McClure1987; Wallace and Hain Reference Wallace and Hain2000), although numbers were low even when compared with the small numbers of other insects collected in 2020 and 2021.

Collectively, these findings are significant because we conducted our surveys at sites with advanced infestations of A. tsugae, with high abundances of this alternate prey. On the other hand, its infestations may have displaced native insects, whose predators may not have yet adapted to A. tsugae as a prey source or may not have yet increased numerically in response to its availability. Branch sampling that involves rearing out insect material has been used to evaluate Laricobius spp. abundance (Mausel et al. Reference Mausel, Salom, Kok and Davis2010) and may be more suitable for specialist predators associated with hemlock woolly adelgid ovisacs or for species that are rare or difficult to dislodge. However, in combination with the predators found during sampling of open branches, we conclude, based on our sampling methods, that the resident natural enemy complex in Nova Scotia exerts only minor and incidental predation that does not offset this pest’s high population growth rates.

The phenology of an invasive insect is a key factor in its population dynamics and interactions with natural enemies in a new region, with implications for pest management that includes biocontrol (Stastny et al. Reference Stastny, Corley and Allison2025). The most conspicuous difference in the development of A. tsugae in Nova Scotia compared to other well-studied invaded regions was the relatively delayed onset of the progrediens egg and crawler stages (Fig. 3), which occurred at least a month later than in the populations found in Virginia (Gray and Salom Reference Gray, Salom, Salom, Tigner and Reardon1996) and Connecticut (McClure Reference McClure1987). We suspect that the timing of development in Nova Scotia is similar to that in maritime regions of the northeastern United States of America (e.g., southern Maine, coastal New Hampshire, and Massachusetts), which share the same plant hardiness zones; however, published data on A. tsugae phenology in these regions are lacking. The relative asynchrony in development between Nova Scotia and British Columbia (Zilahi-Balogh et al. Reference Zilahi-Balogh, Humble, Lamb, Salom and Kok2003) is unsurprising, given the differences in climate (i.e., plant hardiness zones 5b, 6a, 6b in Nova Scotia versus 8a–8b in British Columbia), the role of photoperiod in the phenology of A. tsugae (Salom et al. Reference Salom, Sharov, Mays and Neal2001), and the fact that the invasive strain originated from Japan (Havill et al. Reference Havill, Shiyake, Lamb, Footitt, Yu and Paradis2016). We nonetheless observed similar timing of the peak sistens egg stage and aestivation break between the two regions (Fig. 3; Zilahi-Balogh et al. Reference Zilahi-Balogh, Humble, Lamb, Salom and Kok2003). This phenological match is particularly important because, in British Columbia, it coincides with the aestivation break of one of the region’s native specialist predators of A. tsugae, the beetle, Laricobius nigrinus Fender (Coleoptera: Derodontidae) (Zilahi-Balogh et al. Reference Zilahi-Balogh, Humble, Lamb, Salom and Kok2003), which feeds on developing sistens nymphs. This beetle has been released as a biocontrol agent in eastern North America since 2003 (Mayfield et al. Reference Mayfield, Bittner, Dietschler, Elkinton, Havill and Keena2023), and the developmental synchrony between this predator sourced from coastal British Columbia and A. tsugae in its invaded range is critical to its successful establishment (Zilahi-Balogh et al. Reference Zilahi-Balogh, Humble, Lamb, Salom and Kok2003; Mausel et al. Reference Mausel, Salom, Kok and Fidgen2008).

The patterns of development of A. tsugae that we observed in Nova Scotia were consistent between 2019 and 2020 and highlight the characteristics of the pest’s complex life cycle. Previous studies (McClure Reference McClure1987; Gray and Salom Reference Gray, Salom, Salom, Tigner and Reardon1996) reported a significant sequential overlap of A. tsugae life stages, although outside of the targeted periods for biocontrol. In Virginia, Gray and Salom (Reference Gray, Salom, Salom, Tigner and Reardon1996) found up to 12 different life stages present across multiple sites in late May; in Nova Scotia, we observed a similar overlap, with a maximum of eight life stages co-occurring in June (Fig. 3). Phenological studies previously conducted in Virginia (Gray and Salom Reference Gray, Salom, Salom, Tigner and Reardon1996), Connecticut (McClure Reference McClure1987), and in the native range of A. tsugae in British Columbia (Zilahi-Balogh et al. Reference Zilahi-Balogh, Humble, Lamb, Salom and Kok2003) show significant yearly fluctuations in A. tsugae development, and these may become more pronounced with increased weather stochasticity under climate change. Our study provides baseline phenology data for current climatic conditions and a reference for comparisons with other regions and plant hardiness zones in eastern Canada that are likely to be invaded by the pest in the future.

Multiple strategies are needed to suppress A. tsugae infestations to mitigate its continued spread and ecological impacts in eastern North America (Emilson and Stastny Reference Emilson and Stastny2019; Mayfield et al. Reference Mayfield, Bittner, Dietschler, Elkinton, Havill and Keena2023). Our study highlights the negligible effect of predation by the resident natural enemies associated with A. tsugae in Nova Scotia. The lack of population regulation in the pest’s invaded range has been invoked as the basis of a biocontrol component of integrated pest management for A. tsugae. In the eastern United States of America, efforts to control the invasive pest now involve, to a varying degree, several specialised predators that are phenologically synchronised with its prey: the beetles Laricobius nigrinus and La. osakensis (Montgomery and Shiyake), and the silver flies Leucotaraxis argenticollis (Zetterstedt) and Le. piniperda (Malloch) (Diptera: Chamaemyiidae) (Mayfield et al. Reference Mayfield, Bittner, Dietschler, Elkinton, Havill and Keena2023). Except for La. osakensis, which is native to Japan, these predators are native to British Columbia and other areas of the Pacific Northwest, where they appear to exert strong population regulation (Crandall et al. Reference Crandall, Lombardo and Elkinton2022). A similar biocontrol programme has been recommended to control the invasive A. tsugae in eastern Canada (Emilson et al. Reference Emilson, Bullas-Appleton, McPhee, Ryan, Stastny and Whitmore2018; Emilson and Stastny Reference Emilson and Stastny2019; Stastny et al. Reference Stastny, Roscoe, Fidgen, Vankosky and Martel2024), and research is underway to examine the candidate agents’ suitability and to optimise their sourcing and releases. Our findings suggest that Nova Scotia is phenologically well suited for the redistribution of La. nigrinus from its native populations in British Columbia, but Leucotaraxis silver flies are less suitable due to the marked asynchrony between A. tsugae eggs in British Columbia and in Nova Scotia. In combination with the existing data from other invaded regions in the United States of America, our study provides baseline information to guide a phased adoption of an existing biocontrol programme to reduce the pest’s impacts on eastern hemlock in Canada.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.4039/tce.2025.10018.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Matt Smith from Parks Canada (Maitland Bridge/Caledonia, Nova Scotia) and Colin Gray from Mersey Tobeatic River Institute for their assistance with field work in this study. They also thank Donna Crossland for help with field work, Chantelle Kostanowicz for help with processing beat sheet samples, Jessica Cormier for lab assistance, and Dr. Nathan Havill for his assistance in molecular identifications. They are grateful to Dr. Jon Sweeney and anonymous reviewers for constructive feedback on this manuscript and acknowledge SERG-I for funding a portion of this work.