Introduction

European integration has profoundly affected national parliaments – the core arenas of domestic politics. Early accounts, often summarised as the ‘deparliamentarisation thesis’, cautioned that the transfer of competences to the European Union (EU) would erode parliamentary control over the executive (Norton Reference Norton1995; Raunio Reference Raunio1999). However, later studies refuted these alarms, showing that the establishment of European Affairs Committees (EACs) and other oversight bodies enhanced parliaments’ formal powers (Raunio and Hix Reference Raunio and Hix2000; Winzen Reference Winzen2012; Auel, Rozenberg and Tacea Reference Auel, Rozenberg and Tacea2015). More recently, a related line of research has challenged the idea that European integration creates an ‘opposition deficit’ in national parliaments (Mair Reference Mair2007, Reference Mair2013) and instead points to an increasingly active opposition in EU affairs, with heightened contestation both within EACs (Karlsson and Persson Reference Karlsson and Persson2018; Karlsson, Persson and Mårtensson Reference Karlsson, Persson and Mårtensson2024; Karlsson, Mårtensson and Persson Reference Karlsson, Mårtensson and Persson2025) and in plenary debates (Rauh and de Wilde Reference Rauh and de Wilde2018).

However, little is still known about how the EU political system itself – with its supranational rules and treaty-based obligations – reshapes the conflicts underpinning national parliamentary decision-making. Does EU membership depoliticise domestic policymaking, as argued by scholars stressing the EU’s structural bias towards market-liberal solutions (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1999, Reference Scharpf2010; Bartolini Reference Bartolini2005; Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair2009; Mair Reference Mair2013; Zürn Reference Zürn2022)? Or does it instead fuel politicisation by activating a new cleavage dimension centred on national identity (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2008, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Kriesi, Grande, Lachat et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008, Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012)? This tension between depoliticisation and politicisation constitutes the core puzzle of this study. The main argument is that the structural constraints of the EU political system simultaneously drive depoliticisation and politicisation in national parliaments, muting opposition in policy areas strongly influenced by supranational constraints while intensifying it where domestic discretion remains. To test this argument, we present a systematic analysis of how EU membership reshapes opposition behaviour across all policy areas on the national parliamentary agenda. In contrast to previous studies that capture opposition through parliamentary speeches (Rauh and de Wilde Reference Rauh and de Wilde2018) or expressions of criticism in EU-deliberations (Karlsson and Persson Reference Karlsson and Persson2022; Persson, Karlsson, Lehmann et al. Reference Persson, Karlsson, Lehmann and Mårtensson2024; Karlsson, Mårtensson and Persson Reference Karlsson, Mårtensson and Persson2025), we focus on how concrete opposition behaviour in parliamentary committees, measured as motions and reservations, change as a direct consequence of a country’s accession to the EU.

Our analysis focuses on Sweden’s entry into the EU in 1995, drawing on unique longitudinal data of decision-making in the Riksdag from 1970 to 2022. Using difference-in-differences (DiD) models and treating the accession as a natural experiment, we isolate the effect of EU membership on patterns of parliamentary opposition for a period extending more than five decades. Sweden joined the EU alongside Austria and Finland. Its accession coincided with the Maastricht Treaty and the shift from permissive consensus to constraining dissensus (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009), generating unusually strong adaptive pressures given Sweden’s tradition of Social Democratic dominance and a strong state (Lindvall and Rothstein Reference Lindvall and Rothstein2006). These tensions were reflected in the narrow 1994 referendum (51% in favour), which revealed deep ideological divisions in Swedish society.

While parliamentary conflict rose sharply in the post-accession period (Loxbo and Sjölin Reference Loxbo and Sjölin2017), Sweden also developed some of the highest levels of EU scrutiny (Auel, Rozenberg and Tacea Reference Auel, Rozenberg and Tacea2015) and one of the strongest records of compliance with EU law (Falkner and Treib Reference Falkner and Treib2008). This paradox – sharp domestic contestation combined with strong EU scrutiny and extensive legal compliance – makes Sweden a most likely case of EU-induced cleavage transformation in national parliaments (Kriesi, Grande, Lachat et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008, Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012; Kriesi Reference Kriesi2010). Consequently, if parliamentary opposition is reshaped in the Swedish case – where heightened overall contestation coincides with intense compliance pressures – it would suggest that EU membership may have similar effects across other member states as well.

The findings demonstrate that Sweden’s entry into the EU quite drastically reshaped opposition behaviour in the Riksdag. Directly after EU accession, opposition plummeted within economic and tax policy (ETP), where EU rules strictly constrain national competences. The decline continued without reversal into the 2020s, supporting the view that the EU political system depoliticises economic governance (Bartolini Reference Bartolini2005; Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair2009; Scharpf Reference Scharpf2010; Zürn Reference Zürn2022). By contrast, opposition increased gradually in policy areas tied to national identity and social protection, where domestic control remains (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009; de Wilde and Zürn Reference de Wilde and Zürn2012). Consequently, the results show that the EU political system conditions domestic parliamentary conflict by swiftly depoliticising policy areas constrained by supranational market integration while more gradually politicising those where national sovereignty remains.

Sweden’s experience demonstrates how EU accession can profoundly restructure parliamentary conflict in a single country, while also offering insights of broader comparative relevance. These patterns are not unique to Sweden but likely extend to other member states, which all confront the structural constraints of the EU political system, albeit to varying degrees.

The paper proceeds as follows. We first outline our theoretical framework and develop hypotheses on how the EU political system reshapes national parliamentary opposition. Next, we describe the data and methods and then present the empirical results. We conclude by discussing how these findings advance our understanding of how European integration reshapes parliamentary politics.

Conceptualising parliamentary politicisation and depoliticisation

A vast body of literature maintains that European integration depoliticises national decision-making, as governments delegate competences to supranational bodies and externalise policymaking to non-partisan institutions (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1999, Reference Scharpf2010, p. 239; Bartolini Reference Bartolini2005, p. 405; Mair Reference Mair2013, pp. 129–133; Zürn Reference Zürn2022). This process diminishes the relevance of the left-right ideological divide in domestic politics (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair2009) and strengthens supranational coordination, especially in economic areas (Laffan and Schlosser Reference Laffan and Schlosser2016; Pircher and Loxbo Reference Pircher and Loxbo2020). However, since the Maastricht Treaty, the EU has also become increasingly politicised in the national arena (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2008, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Kriesi, Grande, Lachat et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008, Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012; de Wilde and Zürn Reference de Wilde and Zürn2012), and contestation over EU affairs has intensified within national parliaments (Helms Reference Helms2008; Karlsson and Persson Reference Karlsson and Persson2018; Rauh and de Wilde Reference Rauh and de Wilde2018; Persson, Mårtensson and Karlsson Reference Persson, Mårtensson and Karlsson2019; Persson, Karlsson, Lehmann et al. Reference Persson, Karlsson, Lehmann and Mårtensson2024; Karlsson, Mårtensson and Persson Reference Karlsson, Mårtensson and Persson2025).

Although both depoliticisation and politicisation are results of European integration, most research isolates one dynamic – either how institutional constraints mute partisan contestation (Bartolini Reference Bartolini2005; Mair Reference Mair2007, Reference Mair2013), or how actors ignite new conflicts (Kriesi Reference Kriesi2010; Hutter and Grande Reference Hutter and Grande2014; Hutter and Kriesi Reference Hutter and Kriesi2022). What remains unclear is how these developments together shape domestic politics over time, in particular patterns of parliamentary opposition. The present study addresses this gap. In the EU context, we argue that depoliticisation and politicisation in parliamentary decision-making are best analysed through opposition behaviour (Karlsson and Persson Reference Karlsson and Persson2018). Governments are bound by supranational obligations, which give them strong incentives to mute domestic conflict (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1999, Reference Scharpf2010; Tallberg Reference Tallberg2002; Tallberg and Johansson Reference Tallberg and Johansson2008). By contrast, opposition parties are not subject to such constraints, making their behaviour a more revealing indicator of the extent to which European integration prompts depoliticisation or politicisation in parliamentary decision-making (Mair Reference Mair2007, Reference Mair2013).

Following Kirchheimer (Reference Kirchheimer1957), we understand parliamentary opposition as the degree to which non-governing parties express disagreement with the government through open criticism of its proposals and the articulation of counterproposals (Kirchheimer Reference Kirchheimer1957, pp. 130–135; Norton Reference Norton2008, pp. 238–239; Loxbo and Sjölin Reference Loxbo and Sjölin2017, p. 590; Karlsson and Persson Reference Karlsson and Persson2022, p. 290). Drawing on Schattschneider’s (Reference Schattschneider1960) conception of politics as a struggle over political alternatives, we suggest that parliamentary decision-making becomes politicised when opposition parties actively compete with the government by rejecting its policies and advancing alternative policy proposals. By contrast, decision-making shifts towards depoliticisation the more government and opposition converge on the same policy agenda and ideological disagreements diminish – what Kirchheimer (Reference Kirchheimer1957) described as the ‘waning of opposition’.

We argue that a country’s accession to the EU influences the degree of parliamentary depoliticisation and politicisation through two different mechanisms – one abrupt and one gradual. The first is a critical juncture (Gerschewski Reference Gerschewski2021), in which new institutional constraints immediately disrupt established patterns of contestation. The second one is an adaptive mechanism (Pierson Reference Pierson2000), through which actors learn and gradually adjust their strategies to new constraints.

The impact of the EU political system and the dimensions of embeddedness

In this study, we examine how the EU political system shapes parliamentary opposition through its institutional structure: supranational delegation tends to mute domestic conflicts, whereas national discretion leaves room for politicisation. To capture this variation within a national parliament, we distinguish between policy areas that are internationally embedded and those that are domestically embedded.

Internationally embedded policy areas are constrained by external legal, procedural, or normative obligations. Such embeddedness precedes EU membership and is rooted in broader processes of interdependence, where international regimes – governing trade, finance, and security – had already constrained national autonomy, particularly in smaller states (Keohane and Nye Reference Keohane and Nye1977). Similarly, Ruggie’s (Reference Ruggie1982) notion of ‘embedded liberalism’ illustrates how international economic openness during the post-war era created external commitments that partly depoliticised domestic decision-making. We argue that a country’s EU accession substantially reinforces these tendencies within internationally embedded policy areas by adding a new layer of supranational constraints (Bartolini Reference Bartolini2005; Abbott, Levi-Faur and Snidal Reference Abbott, Levi-Faur and Snidal2017). Specifically, by delegating decision-making autonomy in certain areas to supranational institutions, accession formally narrows the scope for domestic contestation, while also incentivising national politicians to tone down conflicts and present unified policy positions (Majone Reference Majone2001; Tallberg Reference Tallberg2002).

Domestic embeddedness, by contrast, refers to policy areas largely under national jurisdiction with few or no external constraints. In these areas, accession does little to narrow policy alternatives, allowing national actors more room to politicise different choices. Notably, when domestically embedded policy areas concern national identity or welfare in the context of European integration, partisan actors are especially prone to exploit the absence of supranational constraints, mobilising Eurosceptic sentiments to defend national arrangements against liberalisation and external pressures (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2008, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Kriesi, Grande, Lachat et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012; Hutter and Grande Reference Hutter and Grande2014).

Consequently, the abrupt and adaptive mechanisms outlined above should operate differently depending on whether policies are internationally or domestically embedded. In internationally embedded areas, the more extensive supranational constraints should trigger an abrupt break in patterns of contestation, with subsequent adaptation consolidating a new equilibrium. By contrast, in domestically embedded domains, where external constraints are weak or absent, we anticipate no immediate break. Instead, we expect that developments in these domains primarily follow the adaptive mechanism, as parties learn to exploit new opportunities.

In the following section, we develop hypotheses on how these dynamics translate into observable patterns of parliamentary depoliticisation and politicisation.

Parliamentary depoliticisation after EU membership

Our first hypothesis (H1), the depoliticisation hypothesis, builds on the premise that a country’s EU accession depoliticises internationally embedded policies. We expect this pattern to be particularly pronounced in economic and tax policy (ETP), where EU accession deepens international embeddedness through the four freedoms while supranational harmonisation of the internal market directly constrains domestic policy alternatives.

The EU is characterised by a structural bias that favours the free movement of capital over domestic regulation, making economic policy deeply constrained by supranational authority. Bartolini (Reference Bartolini2005, p. 246) even argues that the EU has elevated market liberalism to ‘the level of supreme law’, subordinating all other political objectives to the goal of economic integration. We expect accession to trigger an abrupt change in patterns of opposition, driven by these constraints. Specifically, the imposition of binding EU rules is expected to narrow the range of viable alternatives, locking in market-liberal solutions (Zürn Reference Zürn2022) and muting traditional left-right conflicts over economic regulation (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair2009; Mair Reference Mair2013). Delegation of economic policymaking to non-majoritarian institutions (NMIs), such as the European Central Bank, likely reinforces these effects by further insulating policymaking from partisan politics (Thatcher and Stone Sweet Reference Thatcher and Stone Sweet2002; Thatcher Reference Thatcher2005). In such a context, domestic contestation over regulatory alternatives that once lay at the core of economic politics becomes contained, leaving only those options compatible with the EU’s liberal economic order (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1999; Reference Scharpf2010; Bartolini Reference Bartolini2005; Zürn Reference Zürn2022).

A similar logic applies to tax policy. While the EU does not impose its own taxes, legislation on indirect taxation is extensive and often requires harmonisation to safeguard the internal market (see the tax chapters in the TFEU, Art. 110–118 and tax policy related to other policy areas: Art. 45–66, TFEU; Art. 191–192, TFEU; Art. 107–109, TFEU). Moreover, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) consistently prioritises free movement of capital over national tax autonomy, which results in an implicit pressure to maintain low taxation on mobile capital (Scharpf Reference Scharpf2010). This renders large parts of tax policy internationally embedded within the EU, thereby further constraining the scope for domestic contestation. Over time, we expect the constraining impact of these institutional arrangements to be reinforced by the adaptive mechanism, as opposition parties gradually internalise the futility of contesting internationally embedded ETP.

However, incentives differ across the party system. Conservative and liberal parties generally endorse EU-aligned policies as they fit their market-oriented ideologies (Marks and Wilson Reference Marks and Wilson2000; Hooghe, Marks and Wilson Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002). By contrast, social democratic and radical left parties face increased barriers to advocating market regulation and, therefore, downplay alternatives that are no longer feasible (Ladrech Reference Ladrech2000). As a result, parliamentary opposition from both left and right parties is likely to diminish, as they increasingly converge on similar ideological positions (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair2009). Consequently, the explanation we advance is structural rather than agency-based. By narrowing feasible policy alternatives in internationally embedded ETP, we argue that EU membership reduces partisan conflict.

In sum, we expect EU accession to depoliticise parliamentary decision-making in internationally embedded ETP through both mechanisms: an immediate critical juncture, where accession reduces the range of viable alternatives, and a gradual adaptive process, where opposition parties consolidate the new equilibrium over time.

H1 (depoliticisation hypothesis): A country’s accession to the EU depoliticises internationally embedded ETP, with opposition dropping immediately after accession and remaining low over time.

Parliamentary politicisation after EU membership

Our second hypothesis (H2), the politicisation hypothesis, proposes that domestic embeddedness is a key driver of parliamentary politicisation after EU accession. European integration has been associated with a shift in political contestation from economic redistribution to national identity and Euroscepticism (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2008, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Kriesi, Grande, Lachat et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012). We argue that EU accession fuels this shift within national parliaments. At the same time, we anticipate growing contestation concerning the socially protective functions of the state that continue to be exercised domestically rather than at the EU level (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1999, Reference Scharpf2010; Rommel and Walter Reference Rommel and Walter2017).

On this basis, we expect pronounced politicisation after accession in what we term national identity and protection policies (NIPP). This category relates to two sets of policy issues. The first concerns immigration, law and order, and cultural affairs, which lie at the core of the GAL–TAN dimension (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Kriesi, Grande, Lachat et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012). The second concerns welfare protection, labour market regulation, and public service and infrastructure.Footnote 1 In these areas, the state maintains a protective function vis-à-vis market liberalisation, a function that has become increasingly politicised through European integration (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1999, Reference Scharpf2010; Hurrelmann, Gora and Wagner Reference Hurrelmann, Gora and Wagner2013; Rommel and Walter Reference Rommel and Walter2017). Although the issues included in NIPP derive from distinct dimensions of political conflict – cultural and distributive – they remain largely domestically embedded. This implies that key decision-making authority ultimately rests with the national parliaments. If supranational authority expands within NIPP, we anticipate opposition intensity to decline, mirroring the depoliticisation of ETP. However, as long as domestic embeddedness prevails, EU accession should turn NIPP into a hotspot for parliamentary contestation.

Given that domestically embedded NIPP remains under national discretion, we do not expect EU accession to trigger an abrupt shift in opposition levels, as hypothesised for ETP in H1. Instead, we expect an adaptive process in which opposition parties gradually learn to navigate the new opportunity structures. Specifically, while supranational constraints mute contestation, we expect that political actors shift their attention towards policy areas that remain under domestic control where contestation is more feasible, such as those included in NIPP. In this perspective, politicisation refers to a structural shift in opportunity structures; while parties might differ in the extent to which they exploit these opportunities, our focus lies on the structural transformation itself rather than on partisan variation.

H2 (politicisation hypothesis): A country’s accession to the EU politicises domestically embedded NIPP, with opposition rising gradually after accession and remaining elevated over time.

Taken together, H1 and H2 posit that EU accession prompts an asymmetric reallocation of parliamentary opposition, with an abrupt and durable depoliticisation of internationally embedded ETP, coupled with a gradual politicisation of domestically embedded NIPP.

Data and methods

To test our hypotheses, we build on and expand the data assembled and analysed by Loxbo and Sjölin (Reference Loxbo and Sjölin2017). Our database has been created from content analyses of reports on government propositions from all standing committees in the Swedish parliament for a period of over 50 years, from 1970 to 2022. When studying parliamentary opposition using these data, we focus on how parties formally position themselves through motions and reservations on proposals discussed during parliamentary committee deliberations, which precede plenary debates and votes (Damgaard Reference Damgaard1973; Damgaard and Mattsson Reference Damgaard, Mattsson, Döring and Hallberg2004; Loxbo and Sjölin Reference Loxbo and Sjölin2017).Footnote 2

The database consists of detailed information on parties’ positions on government proposals from over 5300 committee reports. We adopt the same sampling strategy as Loxbo and Sjölin (Reference Loxbo and Sjölin2017), and select the mid-parliamentary session years from each of the 16 election periods in our study.Footnote 3 This strategy avoids the high levels of conflict that typically characterise election years, and – considering that some elections are more conflictual than others – minimises systematic variation linked to electoral cycles. This approach, thus, enhances comparability across time. The database includes information on all government proposals debated and decided upon by the Swedish parliament across 26 distinct years, representing 18 different governments. Sweden’s EU accession took place in 1995 during the 9th government in our data, 1994–1998 (see Table A3 for further details).

During the period covered in this study, government formation in Sweden was shaped by the left-right bloc divide, with eight governments formed by centre-right coalitions and ten by the Social Democrats – eight minority one-party cabinets and two minority coalition governments with the Green party. While most government formations between 1970 and 2022 have resulted in formal minorities, they have often functioned as de facto majority governments – so-called ‘majority government in disguise’ (Strøm Reference Strøm1990, pp. 61–62) – by securing parliamentary majorities through formal or informal arrangements with support parties outside the government (Table A3). Accordingly, while a few substantiative minority governments existed during the time frame of our study, the overall relationship between government and opposition in Sweden from 1970 to 2022 does not deviate systematically from the majority-minority patterns that are typical of other parliamentary regimes in Western Europe (Bergman, Ecker and Müller Reference Bergman, Ecker, Müller, Wolfgang and Hanne Marthe2013, pp. 40–41).

The database was assembled using a combination of hand-coded and semi-automatic content analyses (Pircher Reference Pircher2023). The units of analyses are individual reports on government bills set up by one of the 16 standing committees of the Swedish parliament. A range of stability tests confirms the reliability of the variables. Inter-coder reliability tests demonstrate a coding agreement of 96% for 25% of the whole database between 1970 and 2014 (Loxbo and Sjölin Reference Loxbo and Sjölin2017, p. 596). Moreover, all variables used in the present study (see below) were subjected to an additional inter-coder reliability test. The measure of reliability, Krippendorff’s Alpha (Kalpha), considers the observed and expected disagreement between the measures produced by the two coders.Footnote 4 The average score was high (Kalpha = 0.98), which reflects that the content analysis considers structured committee reports and is based on straightforward counts with few interpretations.

Operationalising key variables

While previous studies have focused on short-term trends in EU opposition expressed in plenary debates (Rauh and de Wilde Reference Rauh and de Wilde2018) or ECA deliberations (Karlsson and Persson Reference Karlsson and Persson2022), we examine long-term shifts in concrete parliamentary decision-making. Our time-series data spans approximately 25 years before (1970–1995) and after (1995–2022) Sweden’s EU accession in 1995.

As detailed in Table A3 in the online Appendix, we define opposition parties as parties not holding executive power formally outside ruling government coalitions or support arrangements (Karlsson and Persson, Reference Karlsson and Persson2022; Persson, Karlsson, Lehmann et al. Reference Persson, Karlsson, Lehmann and Mårtensson2024). Our dependent variable is labelled opposition intensity and is composed of two key indicators of each opposition party’s disagreement with a government proposal. Firstly, our data register the frequency of counterproposals – motions – to a committee recommendation, which represents the parliamentary majority (normally the government).Footnote 5 If an opposition party issues several counterproposals, it demonstrates that it finds numerous aspects of the proposal unacceptable or problematic. Consequently, more counterproposals indicate a deeper opposition to the proposal as a whole, whereas fewer motions suggest isolated concerns about specific details.

Secondly, we account for the frequency of opposition parties’ reservations to the committee report, which are legally formalised statements of dissent in the Swedish parliament.Footnote 6 As with motions, fewer reservations reflect targeted objections to limited parts of a proposal, whereas a greater number shows that an opposition party is committed to formally documenting its dissent and challenging the majority’s view on several issues. In summary, the dependent variable in our study, opposition intensity, measures the mean frequency of all opposition parties’ (see Table A3) counterproposals and reservations to each committee report. Although we treat motions and reservations as complementary forms of parliamentary contestation, we acknowledge that they may capture somewhat different opposition strategies. To ensure that our findings are not driven by one of the measures, we also analysed motions and reservations separately (Tables C12–C13).

To operationalise H1 and H2, we classify the committee reports into one of the 16 policy areas, as outlined in Table B1. Each policy area consists of multiple subcategories, capturing the specific content of government proposals. In addition, we distinguish between internationally and domestically embedded policies, depending on whether a policy primarily concerns Sweden’s internal affairs or involves international agreements, cross-border cooperation or legislative processes linked to international commitments (for details and coding specifics, see Table B2).Footnote 7 To operationalise H1, we construct a category – ETP – that includes monetary and fiscal policy, budget-related policy, corporate and income taxation, indirect taxes, trade policy, and state intervention. Within ETP, we further distinguish between domestically embedded policies, which remain primarily under national control, and internationally embedded policies. Tables B1 and B3 provide details on the coding of these subcategories.

To operationalise H2, we construct the category NIPP, which includes constitutional policy, law and order, cultural policy, immigration policy, policy for public service and infrastructure,Footnote 8 social policy, and labour market policy (for details, see Table B4). These policies often shape debates on national independence, security, collective goods, and welfare provisions. As outlined above, we expect politicisation to be strongest in domestically embedded NIPP, where national politicians retain greater control over policies. In contrast, internationally embedded NIPP – such as external migration policies or cross-border legal frameworks – are subject to international coordination, potentially limiting domestic contestation. Table B4 provides a detailed overview of these subcategories.

While these policy categories are broad, our detailed coding scheme systematically accounts for policy content and scope (domestic or international), as detailed in Tables B1–B2. The coding has undergone multiple stability tests, confirming a high degree of reliability, with independent coders reaching almost identical classifications across over 5300 observations.

As control variables, we include a range of generic features of committee reports that are likely to correlate with varying opposition levels and potentially confound the effect of EU accession. Specifically, the models in the following section control for whether a policy proposal implies (a) new costsFootnote 9; (b) new or amended legislationFootnote 10; (c) is subjected to rules limiting opposition to the yearly budget (introduced in 1997) (Calmfors Reference Calmfors and Pierre2015, p. 602; Lewin and Lindvall Reference Lewin, Lindvall and Pierre2015, p. 589)Footnote 11; and (d) concerns controversial lifestyle issues of relevance for the GAL-TAN dimension.Footnote 12 In addition, we account for the few proposals that explicitly reference the institutions of the EU or international organisations such as the UN, NATO, OECD, WTO, or World Bank, ensuring that such exceptional cases do not bias the estimates. Summary statistics for the variables in the analysis is presented in Tables A1–A2.

Methods for testing the hypotheses

Sweden’s accession to the EU in 1995 represents a critical juncture – an exogenous institutional shock – that we treat as a natural experiment. A natural experiment arises when an externally induced change functions like a ‘treatment’ while other relevant conditions remain stable. The ‘treatment’ in our design is the EU accession, while the core parliamentary setting – the standing committees and the decision-making procedures – remained unchanged. The only partial exception was the creation of the EAC (EU-nämnden), where opposition only takes the form of non-binding statements.Footnote 13

To test the hypotheses, we employ a DiD approach and use the timing of accession as the intervention (Loxbo and Pircher Reference Loxbo and Pircher2024). For (H1), internationally embedded ETP are coded as the ‘treated’ group, while the remaining policy areas serve as a control group. For (H2), domestically embedded NIPP is the ‘treated’ group. ETP and NIPP are not exhaustive categories as several other policy areas – such as foreign and defence policy, agriculture, and the environment – fall outside these definitions and are included in the control group in the respective models. Figures A1–A3 provide further details of all policy areas and their classification into treatment and control groups.

The design of our study isolates the impact of EU accession by comparing changes in opposition intensity across treated and control groups before and after 1995. The counterfactual assumption in these models is that, in the absence of accession, opposition trends in treated policy areas would have followed parallel trends to those in the control group. We, thus, interpret deviations from parallel trends during the post-accession period as evidence that EU accession influenced opposition behaviour.

One potential concern with our approach is that gaps in the time series may prevent us from exactly capturing the timing of the treatment effects. However, if Sweden’s EU accession influenced opposition intensity in the first place, we argue that such effects should be noticeable directly after 1995, when Sweden officially joined the EU. Therefore, given that our dataset covers this and the surrounding yearsFootnote 14, our main focus is on average treatment effects (ATEs) rather than dynamic effects – that is, the overall shift in opposition after EU accession. However, we consistently compare our results with time-varying estimates from dynamic models. We only draw conclusions about treatment effects if they hold across these different specifications.

Our analysis combines cross-sectional data of all 5317 observations with panel data aggregated to 832 policy-year observations. We use both approaches to capture the two mechanisms of change. The cross-sectional model identifies whether EU accession produced a critical juncture – a sudden structural break in opposition intensity – whereas the panel model tests whether such differences were sustained within policy areas over time, in line with the adaptive mechanism.

The cross-sectional model is specified as:

In specification (1), Yi represents opposition intensity in policy area i, indicating whether it is treated (=1) or not (=0). Post95 is a binary indicator for the post-treatment period, and the treatment effect

![]() $\left( {{{Polic}}{{{y}}_{{i}}} \times {{Post}}95} \right)$

captures the treatment effect. In the model, λt denotes year-fixed effects to control for time-specific shocks, while δc is committee fixed effects to address unobserved heterogeneity at the committee level. εi is the error term.Footnote 15

$\left( {{{Polic}}{{{y}}_{{i}}} \times {{Post}}95} \right)$

captures the treatment effect. In the model, λt denotes year-fixed effects to control for time-specific shocks, while δc is committee fixed effects to address unobserved heterogeneity at the committee level. εi is the error term.Footnote 15

The panel model (specification (2)) extends this analysis by adding a temporal dimension, which allows us to test whether the post-accession shift in opposition intensity persisted, faded, or intensified over time:

Specifications (1) and (2) are identical except that (2) adds the subscript t and reorganises the dataset to reflect mean values for each policy area and year. While both specifications assess temporal dimensions, they do so in distinct ways. The cross-sectional model tests the abrupt mechanism, identifying a discrete break before and after accession. However, the analysis is limited to within-year comparisons between treated and untreated policy areas. By contrast, the panel model tracks changes within the same policy areas across years, thereby testing the adaptive mechanism by assessing whether differences between the pre- and post-treatment periods were sustained over time. Yet, since the panel model does not reveal exactly when such adjustment occurs, the adaptive mechanism is also examined more directly in the dynamic DiD models – specification (3) – discussed below. By combining cross-sectional, panel, and dynamic specifications, we strengthen the robustness of our findings and distinguish between sudden and adaptive effects of EU accession on parliamentary opposition.

Robustness checks

For our hypotheses to hold, the results must be consistent across specifications (1) and (2) and confirm that opposition trends were parallel between the control and treatment groups before Sweden’s EU accession, while diverging significantly afterwards. In addition, we subjected the findings to a comprehensive set of robustness checks, including time-series analyses, dynamic panel models that assess autocorrelation and the stability of the results over time, and dynamic DiD models (introduced as specification (3) in the results section) that allow us to trace the yearly evolution of treatment effects. We also test for heterogeneity in treatment effects across governments and different constellations of opposition parties, and validate the results by replacing our dependent variable, opposition intensity, with an alternative measure.

Results

To recapitulate, H1 posits that EU accession depoliticised internationally embedded ETP, while H2 suggests that domestically embedded NIPP became more politicised. We base these hypotheses on the notion that supranational integration, initiated by a country’s accession to the EU, constrains national policy-makers and reshapes domestic conflicts. Figure 1 presents descriptive trends of opposition intensity across domestically and internationally embedded ETP and NIPP before and after Sweden’s EU accession.

Figure 1. Opposition intensity within domestic and international ETP and NIPP in the Swedish parliament before and after the EU accession.

Note: The vertical line marks Sweden’s EU accession (1995). In panels (C–D, G–H) centre-right parties refer to the Moderate, Liberal, Christian Democratic, and Centre parties (see Table A3 for further details). Whiskers in panels (C–D) and (G–H) are 95% CIs.

In Figure 1, panels (A–D) show time trends for ETP. We see that opposition to domestic ETP (panel A) rose slightly but remained below the overall trend. Conversely, opposition to international ETP (panel B) dropped sharply after accession. The comparisons before and after the accession across party groups further underline this difference. Although panel (C) points to a general increase in opposition to domestic ETP, the wide confidence intervals suggest that variations across years cancel out any trend. By contrast, panel (D) demonstrates a clear and consistent fall in opposition to international ETP across all party groups.

Panels (E–H) reveal the opposite trend for NIPP, indicating a gradual spike in politicisation. Panel (E) shows a sharp post-accession increase in opposition to domestically embedded NIPP, and panel (G) illustrates a rise across all parties – although strongest among the radical left and Greens. By contrast, opposition to international NIPP declined modestly after accession (panel F), while panel (H) shows only minor shifts among party groups.

Taken together, the trends in Figure 1 provide preliminary support for H1 and H2. They visually indicate that EU accession depoliticised internationally embedded ETP, while domestically embedded NIPP was increasingly politicised. To test these patterns formally, we now turn to the DiD models in Table 1.

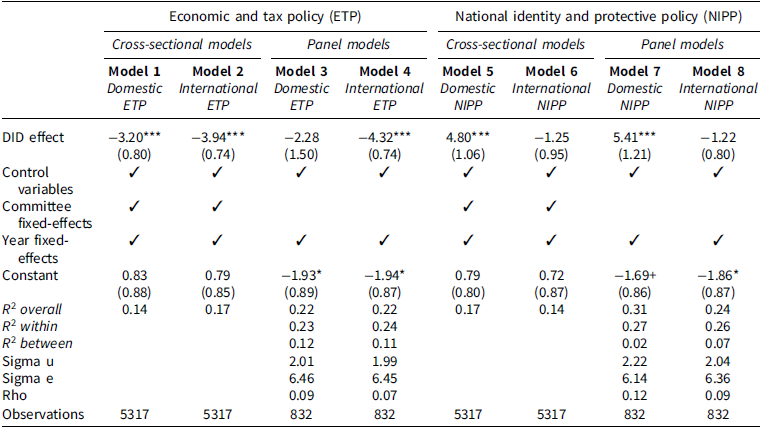

Table 1. Difference-in-differences estimations – the impact of Sweden’s EU accession on opposition intensity within ETP and NIPP

The models in Table 1 estimate the impact of Sweden’s EU accession on opposition intensity in ETP and NIPP (domestically and internationally embedded). The models pass the parallel trends testFootnote 16 and reveal a clear divide between domestically and internationally embedded policy areas that align with our hypotheses. Models 2 and 4 indicate that EU accession depoliticised internationally embedded ETP (H1), while models 5 and 7 show intensified contestation in domestically embedded NIPP (H2).

The cross-sectional models (models 1–2, 5–6) – specification (1) – compare opposition intensity before and after Sweden’s EU accession across all observations, while the panel models (models 3–4, 7–8) – specification (2) – assess whether these changes persisted over time.

The cross-sectional model for domestic ETP (model 1) shows a significant post-accession drop in opposition intensity (−3.20, p < 0.001) that does not persist in the panel model (model 3, −2.28, p < 0.12). This suggests that opposition to domestic ETP fell sharply around the time of Sweden’s accession but that this shift was not consistent throughout the post-accession period. By contrast, opposition to internationally embedded ETP exhibits a sharp and durable decline. Model 2 shows a strong post-accession decrease (−3.94, p < 0.001), while the panel specification (model 4) confirms a persistent decline over time (−4.32, p < 0.001). In line with H1, the cross-sectional estimates capture an abrupt break in opposition behaviour, while the panel estimates point to a stable negative trend that is consistent with an adaptive mechanism.

The inclusion of controls for budgetary bills and changes in public expenditure (detailed in Tables A4–A5) strengthens the case that the decline in opposition within ETP was driven by EU accession and not by economic developments or the 1997 budget process reform, which explicitly sought to reduce parliamentary opposition (Bergman and Bolin Reference Bergman, Bolin, Bergman and Strøm2013, p. 266).

Moreover, the depoliticisation of ETP shown in models 1–4 was reflected in government strategy at the time of accession. For instance, Prime Minister Göran Persson (1996–2006) described decision-making on EU-related economic policy as ‘secret handshake’ with the centre-right opposition parties, designed to build consensus on the new fiscal constraints imposed by EU membership (Persson Reference Persson2007, p. 236). Official government policy also confirmed the changed economic priorities, as Sweden’s fiscal strategy after EU accession explicitly aimed to comply with the Maastricht Treaty’s budget surplus requirements (Calmfors Reference Calmfors and Pierre2015, pp. 602–603; Proposition 1997/98: 25).

While these accounts, along with a few studies (Lindvall and Rothstein Reference Lindvall and Rothstein2006; Lewin and Lindvall Reference Lewin, Lindvall and Pierre2015), already indicated that the EU accession depoliticised economic policy in Sweden, the average treatment effects in models 1–4 provide novel evidence that this shift was abrupt and long-lasting, with a profound impact on patterns of parliamentary opposition. Yet the more exact timing of these effects is analysed in Figures 2–3 below.

Figure 2. Event plots depicting average treatment effects (Sweden’s EU accession) by year (A–B, E–F) and over time (C–D, G–H) in ETP and NIPP.

Note: Event plots are based on the models in Table 1. Whiskers and shaded areas are 95% CIs.

Figure 3. Event plots depicting dynamic treatment effects (Sweden’s EU accession) in internationally embedded ETP and domestically embedded NIPP.

Note: The plots in Figure 3 illustrate dynamic treatment effects over time, complementing the average treatment effects reported in Figure 2. Whiskers are 95% CIs, while the dotted lines are 99% CIs. Full model estimates are available in Tables C1–C8.

Turning to NIPP, the results in models 5–8 align with H2. The cross-sectional model shows a post-accession increase in opposition intensity for domestically embedded NIPP (+4.80, p < 0.001, model 5), and the panel specification suggests that this rise was sustained over time (+5.41, p < 0.001, model 7). In contrast to ETP, this indicates a rise at accession and a sustained increase thereafter (see Figures 2–3 for timing).

For internationally embedded NIPP, the coefficients in the cross-sectional (model 6) and panel (model 8) specifications are negative but insignificant. Consequently, while opposition levels vary across areas within NIPP (Figure A5), we find no systematic depoliticisation comparable to ETP (models 1–4, Table 1). We suggest that the lack of a clear trend reflects differences in institutional constraints across policy areas. In economic policy, EU rules on fiscal surveillance, competition, state aid, and the single market are highly binding (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1999, Reference Scharpf2010). By contrast, in NIPP, supranational authority has expanded more recently and remains partial, leaving substantial national discretion.

Immigration policy illustrates this pattern. Despite repeated EU attempts to harmonise immigration policy, it remains primarily a national issue and has become increasingly politicised domestically. Politicisation has also extended to EU encroachment, with national actors mobilising against these intrusions (Hutter and Kriesi Reference Hutter and Kriesi2022). Thus, enhanced international embeddedness within identity- and welfare-related policies often provokes conflict because supranational authority challenges perceptions of sovereignty (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018). A similar dynamic holds for social policy. Although formally subject to shared competences (Levi-Faur Reference Levi-Faur2014), national discretion in implementation has contributed to recurring controversies over EU encroachment (Pircher, de la Porte and Szelewa Reference Pircher, de la Porte and Szelewa2024).

These examples account for the insignificant effects observed for internationally embedded NIPP. In contrast to ETP, where supranational authority muted opposition, EU encroachment in NIPP has frequently become a source of contestation. As a result, international embeddedness in these domains yields no systematic trend of depoliticisation or politicisation.

To evaluate the timing and stability of the results above, Figure 2 presents yearly estimates based on leads and lags from the models in Table 1. These estimates offer a more fine-grained test of the hypotheses by showing how the disruption at the time of accession developed into long-term trends.

In Figure 2, the cross-sectional estimates (panels A–B, E–F) illustrate the overall trends in opposition intensity before and after EU accession by comparing treated and untreated policy areas within each year. The panel estimates (C–D, G–H) follow the level of opposition intensity within the same policy areas over time and show the extent to which treatment effects were sustained.

The plots in panels (A–D) provide additional support for H1. For internationally embedded ETP, the cross-sectional estimates (panel B) confirm a sharp drop in opposition intensity immediately after accession, while the panel estimates (panel D) demonstrate a sustained decrease throughout the post-accession period. Although we see brief anticipatory effects during the membership negotiations (Aylott Reference Aylott1999),Footnote 17 the deviation from the assumption of parallel trends is minimal.

In addition, panel (A) strengthens the finding in Table 1 that opposition intensity fell to historically low levels also within domestically embedded ETP, while the wider confidence intervals in panel (C) confirm a less consistent trend over time. However, we interpret the sheer magnitude of the post-accession drop as a spillover from internationally to domestically embedded ETP. Specifically, panels (A–B) in Figure 2 show a clear sequencing – an immediate fall for internationally embedded ETP at accession, followed by a sharp drop for domestically embedded ETP one year later – indicating that opposition parties internalised the new EU constraints also in domestically embedded ETP. However, thereafter, we see that the trajectory for domestically embedded ETP is less stable but mostly negative.

Given that the post-accession decline in opposition in internationally and (partly) domestically embedded ETP is consistent across all governments and constellations of opposition parties (see Figure C4), we can reasonably exclude the possibility that it was driven by events unrelated to the EU accession, such as ideological shifts or economic crises (Bressanelli, Koop and Reh Reference Bressanelli, Koop and Reh2020). Moreover, while Figure 2 (panels A–D) shows a slight rise in opposition in the mid-2000s – coinciding with heightened political polarisation during this era (Hagevi Reference Hagevi2015; Loxbo and Sjölin Reference Loxbo and Sjölin2017) – contestation within ETP remained consistently lower during the post-accession period than before. Taken together, Table 1 and Figure 2 strongly support H1.

Turning to NIPP, the event plots in panels (E) and (G) of Figure 2 refine the conclusions drawn based on the average treatment effects in Table 1. Most importantly, while the average treatment effects in models 5 and 7 in Table 1 suggest an immediate post-accession rise in opposition to domestically embedded NIPP, the event plots show that contestation intensified gradually and peaked roughly a decade after accession.Footnote 18 Moreover, while the cross-sectional estimates (panel E) indicates that opposition levels dipped somewhat towards the end of the period, the panel estimates (panel G) show a significantly positive post-accession time trend.

The most visible decline in opposition, displayed in panel (E), occurred during the Social Democratic minority governments of 2014–2022 (Table A3). These governments struck formal agreements with selected opposition parties to curb parliamentary conflict and isolate the emerging radical right Sweden Democrats – the December and January Agreements (Bäck, Hellström, Lindvall et al. Reference Bäck, Hellström, Lindvall and Teorell2024). Yet despite deliberate attempts to institutionally diminish parliamentary conflict, the time-series estimates in panel (G) show that opposition within domestically embedded NIPP never fell back to pre-accession levels.

Taken together, the event-study plots in panels (E) and (G) clearly align with H2’s prediction of a gradual politicisation of domestically embedded NIPP. Furthermore, the plots in panels (F) and (H) confirm that internationally embedded NIPP followed a completely different trajectory, with lower levels of parliamentary conflict. While we see levels rising slightly in some of the later years, the overall time trend remains insignificant. Accordingly, despite variation over time and across different policy areas within NIPP (see Figure A5), a consistent pattern emerges in our study: opposition increased or remained in areas with fewer EU constraints while dropping where supranational competence is more prominent.

In sum, the evidence supports H1 and H2. In Sweden, the 1995 EU accession muted parliamentary opposition in internationally embedded ETP (H1), while intensifying opposition in domestically embedded NIPP (H2).

Robustness and stability checks

A series of robustness checks confirms the validity of our findings. While the main analyses in Table 1 and Figure 2 estimate the average treatment effect of EU accession on opposition intensity, the dynamic DiD specification in specification (3) refines this approach by modelling year-specific treatment effects. This allows us to verify whether the effects unfolded gradually or abruptly. The dynamic model is given by:

Specification (3) expands the panel specification (2) by incorporating lead

![]() $\left(\mathop \sum \nolimits_{k = - K}^{ - 1} {\beta _k}\right)$

and lag

$\left(\mathop \sum \nolimits_{k = - K}^{ - 1} {\beta _k}\right)$

and lag

![]() $(\mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 0}^J {\gamma _j})$

indicators for the yearly treatment effects. The leads (βk) capture opposition intensity before accession, and are aimed at detecting anticipatory effects, while the lag terms (γj) track how opposition evolved after the accession. Unlike the panel models in Table 1, which assume a constant post-treatment effect, the dynamic specification allows the treatment effect to vary year by year, thus giving us a more precise assessment of timing. Figure 3 presents dynamic event plots for internationally embedded ETP (panels A–D) and domestically embedded NIPP (panels E–H).

$(\mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 0}^J {\gamma _j})$

indicators for the yearly treatment effects. The leads (βk) capture opposition intensity before accession, and are aimed at detecting anticipatory effects, while the lag terms (γj) track how opposition evolved after the accession. Unlike the panel models in Table 1, which assume a constant post-treatment effect, the dynamic specification allows the treatment effect to vary year by year, thus giving us a more precise assessment of timing. Figure 3 presents dynamic event plots for internationally embedded ETP (panels A–D) and domestically embedded NIPP (panels E–H).

Regardless of the length of time windows in our models (Tables C1–C8), the dynamic effects in Figure 3 are consistent with the main results in Table 1 and Figure 2. Panels (A–D) in Figure 3 confirm that opposition intensity within internationally embedded ETP declined sharply directly after accession, while panels (E–H) strengthen the conclusion that opposition within domestically embedded NIPP gradually peaked in the years following accession.

Moreover, Figure 3 shows no clear anticipatory effects for ETP, while only a small pre-accession rise – confined to a single year – appears for NIPP. Accordingly, the absence of systematic pre-treatment trends strengthens the parallel trends assumption, confirming that the treatment effects were not driven by pre-existing trends. In addition, the results in Figure 3 serve as a placebo test, verifying that the accession in 1995 was the only plausible treatment year. Specifically, if external confounders had affected opposition intensity, we would have expected sharper fluctuations across pre-treatment years, which do not appear.

In the online Appendix C, we also employ fixed-effects panel regression models to validate the treatment effects. Using interaction-over-time analyses (Figure C3), these models reproduce time trends similar to the event plots in Figures 2 and 3.

As a final robustness check, we apply Arellano-Bond system GMM dynamic panel models to account for potential autocorrelation and endogeneity in opposition intensity (see Tables C9–C10). Unlike the DiD models in Table 1, this specification tracks how opposition evolves over time by controlling for lagged values of the dependent variable. The results in Tables C9–C10 confirm our main findings, showing an abrupt decline in opposition for internationally embedded ETP and a gradual increase for domestically embedded NIPP. Based on these models, we also estimate year-specific treatment effects. As seen in Figures C1–C2, these estimates are qualitatively similar to the event plots in Figures 2 and 3. The Arellano-Bond tests detect no problematic autocorrelation in second differences, and the absence of pre-trends further reinforces the parallel trends assumption.

We further address potential endogeneity by estimating the treatment effects separately for the different governments in our dataset. The results, depicted in Figure C4, confirm that the findings are not driven by specific governments or constellations of opposition parties. Finally, we test the sensitivity of our dependent variable, opposition intensity. First, we re-estimate the models using an alternative measure that instead captures the absence of opposition (Table C11), which yields substantively similar results. Second, we analyse motions and reservations separately (Tables C12–C13), and these analyses mirror the main results for both measures.

Conclusion and discussion

This study examines how Sweden’s 1995 EU accession reshaped parliamentary conflict. Drawing on DiD designs with cross-sectional, panel, and dynamic specifications, the analysis traces opposition intensity over five decades, from 1970 to 2022. The results indicate that EU accession reduced contestation in internationally embedded policy areas, particularly economic governance, while increasing conflict over domestically embedded policies related to national identity and social welfare. Thus, rather than producing an ‘opposition deficit’ (Mair Reference Mair2007), EU accession redirected parliamentary opposition, suppressing it in some domains while amplifying it in others. By focusing on concrete opposition behaviour over time, the study yields two novel findings that advance our understanding of the impact of European integration on domestic politics.

The first finding is that Sweden’s EU accession led to an immediate and sustained drop in parliamentary opposition to government proposals in internationally embedded economic and tax policy. This supports the argument that supranational integration depoliticises economic governance by insulating it from domestic contestation (Bartolini Reference Bartolini2005; Blyth and Katz Reference Blyth and Katz2005; Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair2009; Scharpf Reference Scharpf2010). These findings also shed new light on the ‘deparliamentarisation thesis’ in earlier research (Norton Reference Norton1995; Raunio Reference Raunio1999). While we do not study parliamentary control over the executive, our observations clearly align with the spirit of this thesis, suggesting that national parliaments indeed have become less important arenas for contestation in these domains.

However, our second finding points in the opposite direction, suggesting that the EU reshaped parliamentary contestation in more complex ways than the deparliamentarisation thesis suggests. We find that domestically embedded policy areas linked to national identity and social protection became increasingly politicised after accession. In contrast to the idea that European integration marginalises national parliaments, this indicates that they continued to function as central arenas of contestation over sensitive policy areas where national control remains. Unlike the abrupt decline in ETP, opposition gradually intensified in the years following EU accession. We, thus, show an adaptive process of politicisation, as national actors gradually mobilise where supranational constraints remain weak.

Conversely, when these policies were subject to international embedding – such as immigration and social policy in later years – opposition went down but followed no consistent pattern. Accordingly, while our results underscore that the degree of national discretion is decisive in shaping parliamentary contestation after EU accession, depoliticisation is most extensive and enduring in the EU’s core economic sphere.

Our findings contribute to two strands of research. First, they contribute to the literature on how European integration reshapes parliamentary decision-making, moving beyond studies focused on formal scrutiny powers (Winzen Reference Winzen2012; Auel, Rozenberg and Tacea Reference Auel, Rozenberg and Tacea2015) or parliamentary debates (Rauh and de Wilde Reference Rauh and de Wilde2018; Karlsson, Mårtensson and Persson Reference Karlsson, Mårtensson and Persson2025). A central contribution of our temporal analysis is to demonstrate that the distribution of national and supranational competences in the EU political system influences whether national opposition wanes or intensifies. When supranational constraints limit national discretion, parliaments drift towards a ‘surplus of consensus’ (Dahl Reference Dahl1966, p. 397) – especially in the EU’s core economic domain. By contrast, when national discretion remains prominent, conflict intensifies, particularly around questions related to identity and social welfare. In short, our study suggests that supranational integration sets the boundaries between conflict and consensus in national parliaments. This finding adds to the literature on differentiated politicisation (de Wilde, Leupold and Schmidtke Reference de Wilde, Leupold and Schmidtke2016), showing that integration redistributes parliamentary conflict by muting it where decision-making is externalised and amplifying it where national competences remain high.

Second, our findings contribute to the literature of cleavage formation, suggesting that the EU itself structures domestic political conflict (Kriesi, Grande, Lachat et al. 2008, Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Kriesi Reference Kriesi2010). Specifically, our findings further underscore the argument that the suppression of contestation over economics not only fostered ‘policies without politics’ (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2020), but also fuelled new conflicts around identity and social protection. Accordingly, our results indicate that European integration ‘hits home’ by redirecting domestic conflict into domains that have been shown to be prone to the mobilisation of authoritarian populists (Zürn Reference Zürn2022). By gradually disconnecting public opinion from economic policymaking (Beaudonnet and Gomez Reference Beaudonnet and Gomez2024), this development might further fuel Euroscepticism and potentially heightening the risk of democratic backsliding.

We argued that Sweden is the most likely case of EU-driven restructuring of parliamentary conflict. This implies that analogous dynamics should be observable in other EU countries, although with lower intensity and at different times. Among the countries joining the EU alongside Sweden in 1995 – Austria and Finland – research shows similar patterns of depoliticisation and politicisation. In Austria, EU fiscal rules, combined with the corporatist Sozialpartnerschaft, further reduced partisan contestation over economic policy (Pernicka and Hefler Reference Pernicka and Hefler2015), while immigration and Euroscepticism gradually came to dominate the political agenda (Hutter and Grande Reference Hutter and Grande2014). Likewise, in Finland, EU accession reinforced party consensus on macroeconomic governance, whereas debates over sovereignty and identity were politicised gradually over subsequent years (Arter Reference Arter2010; Mattila and Raunio Reference Mattila and Raunio2012). Developments in Denmark, joining the EC in 1973, further strengthen our results by illustrating that elite consensus over economic policy (Sitter Reference Sitter2001; Bartolini Reference Bartolini2005, p. 243) coexisted with growing conflicts over immigration and sovereignty far earlier than in neighbouring Sweden (Green-Pedersen and Krogstrup Reference Green-Pedersen and Krogstrup2008).

In Central and Eastern Europe, the 2004 EU accession influenced domestic conflict in similar ways. Economic governance was quickly channelled into supranational arrangements, while political conflict gradually focused on identity and sovereignty (Vachudova Reference Vachudova2008; Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2019). In Western Europe, more broadly, the depoliticisation of economic policymaking was substantially reinforced by the Eurozone crisis, whereas the politicisation of migration and Euroscepticism intensified as challenger parties consolidated their positions (Hobolt and Tilley Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2020; Hutter and Kriesi Reference Hutter and Kriesi2022). Brexit epitomises how this escalating conflict over identity and sovereignty at the expense of economic concerns (Hobolt Reference Hobolt2016; Vasilopoulou and Wagner Reference Vasilopoulou and Wagner2017) can shape political outcomes.

Accordingly, while this study is among the first to provide a detailed analysis of how European integration reshapes patterns of national parliamentary opposition, the broader literature suggests that the mechanisms we identified – the depoliticisation of economic governance coupled with a gradual politicisation of identity and sovereignty – most likely travel across countries and periods, even if their intensity and timing vary.

Although Sweden provides a most likely case for observing EU-driven restructuring of parliamentary conflict, our design limits the generalisability of the findings. Cross-country studies are needed to map variations, for example, whether institutional arrangements for EU scrutiny (Winzen Reference Winzen2012), executive–legislative relations (Loxbo and Sjölin Reference Loxbo and Sjölin2017), and party systems (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018) condition how EU-related constraints shape parliamentary opposition. Further research should also explore how identity-based politicisation may fuel democratic backsliding by reshaping legislative behaviour (Sedelmeier Reference Sedelmeier2017; Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2019) and how EU institutions respond – through technocratic insulation or democratic reform – and thereby affect the Union’s long-term legitimacy and resilience (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2020; Zürn Reference Zürn2022).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1475676526100711.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available as supplementary material accompanying this article. The data files have been made available by Cambridge University Press upon publication.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editors of the European Journal of Political Research and the anonymous reviewers for their exceptionally constructive feedback on earlier versions of this article. We are also grateful to the participants of the Swedish Network of European Studies Conference (2025) and the EPSA Working Group on Multilevel Politics in Europe (Madrid, 2025) for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Funding statement

This research received no external funding.

Competing interests

Nothing to report.

Ethical approval

Not relevant.