The news media’s normative purpose in democratic society—informing the public—has a long and fitful relationship with profit-seeking commercial enterprise (Hamilton Reference Hamilton2004; Lippman Reference Lippman1922). Yet ongoing technological shifts in the contemporary news market put renewed stress on the media’s ability to fulfill its democratic functions. Editorial decisions about what news to cover and how to cover it are more dependent on more observable audience engagement; today’s news infrastructure both relies on engagement-driven algorithms to shape information flows and provides heaps of audience tracking data to news providers (Petre Reference Petre2021). Because a small, highly engaged core audience contributes most of the digital currencies that revenue-starved outlets depend on (Tyler et al. Reference Tyler, Grimmer and Iyengar2022; Usher Reference Usher2021), news organizations today have strong incentives to package news to appeal to these prolific consumers and seek virality in the online spaces they inhabit (Munger Reference Munger2020). The way that people consume news is also changing: news engagement takes place more frequently through ‘news snacking’ (Molyneux Reference Molyneux2018) via social media and mobile apps, usually on smaller screens (Dunaway and Searles Reference Dunaway and Searles2023; Pew Research Center 2019), giving the news media only narrow windows through which to communicate critical information. These broad shifts in the news market call for renewed scholarship on a classic question in the study of political communication: can the public learn key political information that is ‘central to issues of governing’ (Patterson Reference Patterson1993, 29) from exposure to typical forms of contemporary news coverage?

In a pre-registered survey experiment with a large non-probability sample of US adults (n = 2, 233), I provide clear empirical evidence that the public is less likely to learn critical political information from the news as it is typically packaged by mainstream media organizations today. Presenting respondents with several experimentally manipulated articles adapted from recent news stories, I examine respondents’ ability to learn from each of four different political coverage ‘styles’ (the presentation, framing, and organization of the content) that are common in contemporary US media, or a fifth ‘public interest’ news style that prioritizes accessible, up-front communication of key information. Despite providing identical information content, I find that respondents are less able to recall critical information when exposed to typical news styles, particularly when exposure is brief. These learning penalties are steepest among respondents who are less politically engaged at baseline—suggesting that typical styles widen information disparities among the American public—but penalties also persist even for the most engaged consumers. I also show that ‘under-informative’ styles are not perceived by readers to be any less informative than the public interest style, despite the observed decline in actual recall of key information. Finally, I demonstrate that the public interest style can increase mass support for democratizing policies, whereas under-informative styles do not produce this benefit even when reporting on identical threats to democracy.

The Evolving Economics of News

The commercial nature of the press is nothing new, and news outlets have historically catered to their audience’s preferences (Hamilton Reference Hamilton2004; Lippman Reference Lippman1922; Zaller Reference Zaller2017). Yet the economic and political conditions under which American news media operate today make reconciling the industry’s commercial and normative purposes especially difficult. On the supply side, advancing communication technologies have lowered barriers to market entry and the media environment has consequently fragmented, with legacy media organizations steadily losing market power (Arceneaux and Johnson Reference Arceneaux and Johnson2013; Hindman Reference Hindman2018; Prior Reference Prior2007). On the demand side, consumers have enjoyed increasingly broad choice in venues and content. Because few consumers prefer political news over other options (for example, entertainment), much of which is free, paying audiences for political news have shrunk substantially (Darr et al. Reference Darr, Hitt and Dunaway2018; Hayes and Lawless Reference Hayes and Lawless2021; Hopkins Reference Hopkins2018; Prior Reference Prior2007). Today’s core audience for political news—that is, the narrow high-interest audience that engages frequently—differs from the broader public both demographically and politically (Hersh Reference Hersh2020; Hopkins Reference Hopkins2018; Klar Reference Klar2014; Krupnikov and Ryan Reference Krupnikov and Ryan2022; Prior Reference Prior2007; Usher Reference Usher2021). These ‘deeply engaged’ (Krupnikov and Ryan Reference Krupnikov and Ryan2022) ‘news fans’ (Prior Reference Prior2007) tend to be more partisan, more ideological, and more personally entertained by politics (Hersh Reference Hersh2020; Krupnikov and Ryan Reference Krupnikov and Ryan2022)—traits which profoundly shape the kinds of political coverage they find appealing.

High-engagement consumers contribute the bulk of the digital currencies (clicks, page views, reshares, etc.) that matter to today’s online news market, visiting orders-of-magnitude more political websites than the median consumer (Tyler et al. Reference Tyler, Grimmer and Iyengar2022, 1063) and frequently seeking out news content that gratifies their partisan interests (Iyengar and Hahn Reference Iyengar and Hahn2009; Lorenz et al. Reference Lorenz, Schmitt, McGregor and Malmer2023; Tyler et al. Reference Tyler, Grimmer and Iyengar2022). This demand in turn affects what journalists choose to produce (Hamilton Reference Hamilton2004) and, as I argue, how they package it. Increasingly desperate for both dollars and eyeballs, news outlets use newly available tools for tracking audience engagement (such as Chartbeat, NewsWhip, and Parse.ly, which track click rates, page views, time-on-page, article-by-article ratings, etc. [Petre Reference Petre2021]) to cater more carefully to the demands of their surviving core audience (Mukerjee et al. Reference Mukerjee, Yang and Peng2023). Whereas in prior epochs of mass media the extensive margin (selling a bundled product to another customer) mattered most to news producers, today the intensive margin (clicks per customer) is both highly visible and deeply relevant for economic viability.

Although catering to core consumers may make good business sense, the consequences for democracy are less clear. Recognizing a need to serve a broader public, many media professionals couch efforts to make politics more entertaining as a means of attracting a wider base of consumers and encouraging information-seeking (Blanchett et al. Reference Blanchett, Brin and Duncan2024).Footnote 1 Indeed, major news stories can regularly reach much of the public through occasional direct engagement (that is, a few times per week rather than many times per day [Guess Reference Guess2021]) and through indirect channels like social media, mobile apps, and aggregators (Pew Research Center 2023 b), comprising a large portion of the public’s media diets. Consumers often access these digital spaces without any intent to consume political news, but the decentralized nature of information flows in those spaces enables political news to still reach them. Accordingly, many people believe that news of sufficient importance will automatically reach them organically or algorithmically (Gil de Zúñiga and Diehl Reference Gil de Zúñiga and Diehl2019); others habitually rely on secondhand sources to learn about the news (Palmer and Toff Reference Palmer and Toff2022).

Yet orienting political news coverage towards entertainment may ultimately constitute doubling down on news junkies who already find politics entertaining (Trexler Reference Trexler2024, Reference Trexler2025), as outlets mistake intensity of engagement for breadth.Footnote 2 Furthermore, this strategy might make learning from the news more difficult than it needs to be—especially for incidental audiences that consume infrequently. Irregular and incidental news exposure is particularly important for democratic accountability because such exposure allows news information to reach most of the public (Guess Reference Guess2021; Pew Research Center 2023 a). Incidental exposure to news content can thus help the broad public to make choices that best serve their interests (Lupia Reference Lupia1994, Reference Lupia2016; Popkin Reference Popkin1991)—if the content is relevant to the issues of democratic governance at hand and comprehensible to a broad audience. The dominant forms of news coverage that appeal to the core audience may not meet that standard, thus limiting political learning even conditional on exposure.

Additionally, what news does reach people incidentally through social media and similar environments is a function not only of what news gets produced (which tends to be styled to the core audiences’ tastes), but also of the affordances of the medium through which it is accessed. Social media does not filter news for importance so much as for controversy and drama (Berger and Milkman Reference Berger and Milkman2012; Holiday Reference Holiday2013; Settle Reference Settle2018), skewing the type of news that is likely to reach people organically through these channels. Social media platforms, news apps, and news aggregators (Apple News, Google News, etc.) also limit information processing even when news is accessed. These formats favor short-form content packaged in bite-sized ‘snacks’ (Molyneux Reference Molyneux2018), offering breadth but not depth. Paywalls and other digital frictions frequently inhibit access to content beyond the headline. News engagement typically occurs through ubiquitous handheld devices such as phones and tablets, which encourage shorter news browsing sessions and reduce information processing relative to larger screens (Dunaway and Searles Reference Dunaway and Searles2023). Because news exposure today—whether intentionally sought or incidentally encountered—often entails accessing very limited content, the potential informational impact of news is weighted heavily towards headlines and any accompanying topline summaries. When these elements favor the entertaining aspects of politics rather than substance, we should expect limited exposure to also impart little understanding of the issues at stake.

“Under-Informative” News

Contemporary news outlets use several approaches to make their political coverage more engaging for core consumers. These editorial decisions include committing newsroom resources to specific stories or beats and choosing which stories get placed on the front page, featured as ‘top news’, sent out in push alerts, posted to social media, discussed in subscriber newsletters, and so on. One would certainly expect these decisions to shape the substance of the news that consumers are exposed to, for example by shifting coverage away from substantive policy issues, candidate records, and other content compatible with ideas of ‘public journalism’ (for a formal discussion, see for example Haas and Steiner Reference Haas and Steiner2006, 241), and instead towards content regarding more superficial aspects of politics like horse-race polling or personality coverage. Yet even stories that do provide substantive content relevant for political decision-making can still be presented in a style that makes that key information less prominent and accessible by hiding it behind flashier content.Footnote 3

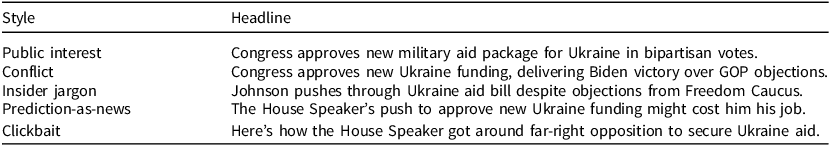

In this study, I examine four ‘under-informative’ styles of coverage that each make learning from political news more difficult.Footnote 4 That is, conditional on both the inclusion of useful political information in the story and exposure to that content, I test whether readers can easily learn key information when the news is packaged in these styles. The four under-informative styles that I examine are: the conflict style, which dramatizes conflict between political forces; the insider jargon style, which references specialized lingo, terminology, and characters without translating their meaning or relevance to a lay audience; the prediction-as-news style, which stakes predictions on future political events; and the clickbait style, which strategically withholds key information to elicit marketable consumer engagement. These four under-informative styles are not mutually exclusive per se,Footnote 5 but I contrast all four with a specific alternative, the public interest style, which explicitly prioritizes communicating relevant policy and governance information such that learning this information requires minimal cognitive effort from the public. To illustrate, Table 1 shows five different ways one could write a headline about Congress’s bipartisan votes to fund a new military aid package for Ukraine in April 2024, which focus on different aspects of the story and vary in their accessibility. I briefly discuss the key characteristics of each style in turn.

Table 1. Example headline in each coverage style

Conflict

Extant research notes the predominance of conflict frames, which focus attention on a story’s purported winners and losers, throughout modern political journalism (Cappella and Jamieson Reference Cappella and Jamieson1997; Dunaway and Lawrence Reference Dunaway and Lawrence2015; Patterson Reference Patterson1993; Rosenstiel Reference Rosenstiel2005).Footnote 6 Conflict frames are attractive in part because they appeal to journalistic norms of balance and objectivity, allowing reporters to articulate the perspectives of both sides while positioning themselves as neutral observers. While not limited to a partisan context (Han and Federico Reference Han and Federico2018), conflict frames in US media typically present American politics as a struggle between Republican and Democratic forces. Though potentially entertaining—Farnsworth and Lichter (Reference Farnsworth and Lichter2011) equate it to ‘politics as sports’, which can best appeal to highly invested partisan consumers—this depiction of politics distracts from substantive policy matters and downplays the deliberative bargaining processes of democratic governance (Patterson Reference Patterson1993).

Insider Jargon

Political journalists frequently engage with their most politically active audiences, both through their work (e.g., interviewing) and through online discussion spaces like comment sections, news apps, and social media (Dunaway and Searles Reference Dunaway and Searles2023; Krupnikov and Ryan Reference Krupnikov and Ryan2022; McGregor Reference McGregor2019; Usher Reference Usher2021). Because these audiences are both heavily invested in politics and extremely visible to journalists, news outlets naturally come to speak a common jargon with this particular subpopulation—and both journalists and their core audience can use jargon to signal expertise and ‘savviness’ (Zaller Reference Zaller2017) to gain social status.

Journalism schools teach numerous practices for engaging a broad audience, such as the ‘inverted pyramid’ framework (providing the most important newsworthy information first and relegating the nuanced details to later) and writing for moderate reading levels. Headlines in particular typically require some compelling contextualization to be meaningful (and interesting) to a broad reader base. However, because the core audience dominates the demand signals visible to journalists (Krupnikov and Ryan Reference Krupnikov and Ryan2022; McGregor Reference McGregor2019; Tyler et al. Reference Tyler, Grimmer and Iyengar2022), outlets regularly instead adopt the ‘insider jargon’ style of news coverage (Trexler Reference Trexler2025). This style employs specialized language and terms (surnames, acronyms, jargon, and the like), which can be used as stand-ins for lengthy or complex counterparts, especially within the tight space constraints of a headline or push alert, and allows journalists to deploy savvy, sophisticated news analysis as a hook. The background contextualization of actors, processes, and terminology that could make the news story more accessible and interpretable to a broader audience (Broockman et al. Reference Broockman, Kaufman and Lenz2024; Jerit Reference Jerit2009) is thus relegated to further down the article—or even left absent.

Prediction-as-News

Horse-race polling coverage (Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Norpoth and Hahn2004; Hillygus Reference Hillygus2011; Traugott Reference Traugott2005) and probabilistic election forecasting by news outlets (Toff Reference Toff2017) represent a booming market for prediction-as-news, and many aspects of US politics only receive substantial news coverage in the context of elections (Huber and Tucker Reference Huber and Tucker2024). While polling coverage is perhaps its most visible form, prediction-as-news encompasses a broader phenomenon of situating predictions of some outcome as newsworthy events in their own right. Such stories need not pertain to elections or even politics. For example, Soroka et al. (Reference Soroka, Stecuła and Wlezien2015) show that economic news tends to report (uncertain) leading indicators of future economic performance more often than observable concurrent or lagging indicators of current economic performance. These stories are usually of greatest interest to consumers who deeply invested in the topic (for example, partisans, political hobbyists), who closely follow each twist and turn of political affairs—that is, habitual consumers.

Clickbait

Economic pressures on the media intensify the need to elicit consumer attention, and particularly consumer attention that can be measured and marketed to advertisers—that is, metrics like clicks and page visits. So-called ‘clickbait’ headlines manipulate basic psychological biases to pique consumer curiosity to draw a click, often under false pretenses, and are therefore valuable to news outlets (at least in the short run) because they attract more measurable engagement that can be advertised to advertisers (Berger and Milkman Reference Berger and Milkman2012; Green et al. Reference Green, McCabe, Shugars, Chwe, Horgan, Cao and Lazer2025; Holiday Reference Holiday2013; Munger Reference Munger2020).Footnote 7 Munger (Reference Munger2020) observes that this advantage is especially true for news circulated on social media, where credibility is often equated with sharing metrics rather than long-term outlet reputation. While those baited into clicking may find less value on the other side than they hoped (Dunaway and Searles Reference Dunaway and Searles2023; Munger et al. Reference Munger, Luca, Nagler and Tucker2020), other consumers who simply scan a clickbait headline without reading further (the overwhelming majority) will likely learn little of value from it, and may also ‘learn’ misperceptions from the misleading headline (Graham et al. Reference Graham, Hillygus and Trexler2024).

Public Interest

If the conflict, jargon, prediction, and clickbait styles are all potentially under-informative for the public, how should journalists present political news? Prior scholarship points to ‘public journalism’, which prioritizes journalism’s civic and democratic responsibilities in news production, as a practicable alternative to conventional approaches (Haas Reference Haas2007; Haas and Steiner Reference Haas and Steiner2006). In keeping with the principles of public journalism, I define the ‘public interest’ style of coverage as centering the normative role of the press in packaging political news. The explicit goal of the public interest style is to communicate news about public affairs ‘in ways that voters can understand and act upon’ (Patterson Reference Patterson1993, 29) with minimal processing effort, thus efficiently arming the mass public (as the principal of a democracy) with the information it most needs to participate in the democratic process and orient the behavior of government (as the public’s agent). Public interest style news prioritizes informing the public about government policy, proposals, and performance in a ‘condensed and easy-to-digest’ (Zaller Reference Zaller2017, 2) format, while all other potentially newsworthy features of a story (conflict, intrigue, process, personality, rhetoric, etc.) are given an ancillary role and relegated to the lower reaches of the inverted pyramid. This means that the critical information is presented first and is clearly communicated in headlines and ledes (as accessible, self-contained summaries of news). Because the press is a core institution of democracy, public interest style news also prioritizes ‘democracy framing’ to clearly communicate contemporary threats to the democratic process itself, even if doing so requires relaxing adherence to other journalistic standards of balance and point–counterpoint coverage (Jang and Kreiss Reference Jang and Kreiss2024; Peterson et al. Reference Peterson, McGregor and Block2025).

Public interest style news represents a significant departure from the four ‘under-informative’ styles. Unlike the conflict style, public interest news engages with the implications of political debates for substantive policy and normative outcomes rather than for partisan strategy. Unlike the insider jargon style, public interest news explicitly aims to make stories accessible to a broad and non-specialized audience. Unlike the prediction-as-news style, public interest news focuses on communicating current events as newsworthy events in their own right. And unlike the clickbait style, public interest news aims to present the most critical information clearly, succinctly, and directly, rather than strategically withholding that information to solicit marketable engagement from the consumer. Importantly, public interest style coverage can include information about partisan conflict, wonky details, and forecasting analyses about downstream political events—but public interest news prioritizes more central information first, before addressing these other elements later in the story. By prioritizing policy-, governance-, and norm-relevant information in its coverage, the public interest style offers a path for consumers at all levels of engagement to easily extract the information they need to understand current events in the context of existing policy and norms, interpret them through the lens of their own political values, and apply this knowledge to future political behavior.

Hypotheses

Each of the four typical styles of political news coverage identified above (conflict, jargon, prediction, and clickbait ) is potentially ‘under-informative’ in the sense that it ‘magnifies certain aspects of politics and downplays others, which are often more central to issues of governing’ (Patterson Reference Patterson1993, 29), thus depressing the mass public’s ability to extract key information from news coverage that could facilitate their political participation and decision making. While each (at least ostensibly) offers the consumer some news information, not all information is equally valuable for mass engagement in politics and governance (Lupia Reference Lupia2016). Because these styles downplay or obfuscate information ‘more central to issues of governing’, consumers may be less likely to recall such information even conditional on exposure, as recall also requires encoding and recovery of that information from memory. After all, news is only informative to the extent that it successfully informs—and this requires that the information be accessible to the broad public. Relative to the public interest style, then, I expect the following:

Hypothesis 1: Under-informative styles of political news coverage reduce the amount of key information recalled after exposure to news content.

Because these contemporary styles are primarily aimed at a core audience that is much more politically engaged than the mass public as a whole, we should expect that consumers’ ability to extract key information from a news story varies as a function of political engagement. Habitually engaged consumers are likely to find these styles appealingFootnote 8 and are likely able to use prior knowledge to make accurate political inferences from the policy information buried within them (Lupia Reference Lupia1994; Lupia and McCubbins Reference Lupia and McCubbins1998). In contrast, less engaged consumers who encounter such styles incidentally may find them inaccessible and struggle to connect the styled content to known policies, actors, values, and priorities. I therefore expect the following.

Hypothesis 2: Individual political engagement moderates the degree to which under-informative styles reduce information recall, such that (a) less engaged individuals recall less from such styles of coverage and (b) more engaged individuals recall more information.

Indeed, under-informative news styles may be a cause of the winnowed audiences for political news, in addition to a byproduct: while a small audience may find these styles appealing and consume them voraciously (Trexler Reference Trexler2024, Reference Trexler2025), many in the broader public may find them uninteresting or even outright uninformative—and therefore not worth their time. Many people are turned off by partisan politics (Prior Reference Prior2007) but are more willing to engage with policy issues (Groenendyk et al. Reference Groenendyk, Krupnikov, Ryan and Connors2025), while others seek to avoid news more generally (Toff et al. Reference Toff, Palmer and Nielsen2023), in part because of the characteristics of news available to them (Toff and Kalogeropoulos Reference Toff and Kalogeropoulos2020). Recent experimental evidence also shows that the public hungers for critical context about existing rather than potential policy, which can better enable them to understand the implications of current events (Thorson Reference Thorson2024). It is possible that under-informative styles are thus broadly perceived as such, especially among the less politically engaged. In contrast, broad failures to perceive these styles as uninformative would help explain the current incentive structure for news outlets to produce such content. I thus consider whether the following are true:

Hypothesis 3: Under-informative styles of political news coverage are perceived as less informative by consumers.

Hypothesis 4: Individual political engagement moderates perceptions of under-informative styles, such that (a) less engaged individuals perceive such styles as less informative and (b) more engaged individuals perceive such styles as more informative.

Similarly, under-informative styles may damage the broader credibility of the media. Scholars have long argued that focusing on conflict and drama engenders cynicism towards politics (see, for example, Cappella and Jamieson Reference Cappella and Jamieson1997; Patterson Reference Patterson1993). More recently, scholars have explored whether these same tendencies also affect the credibility of the news media itself (see, for example, Martins et al. Reference Martins, Weaver and Lynch2018; Toff et al. Reference Toff, Palmer and Nielsen2023) and have likewise identified clickbait as a source of media distrust (Molyneux and Coddington Reference Molyneux and Coddington2020; Scacco and Muddiman Reference Scacco and Muddiman2016, but see Munger et al. Reference Munger, Luca, Nagler and Tucker2020 and Luca et al. Reference Luca, Munger, Nagler and Tucker2022). The media may also lose trust by making too many inaccurate predictions (for example, recent criticism after major polling errors in US elections; see discussion in Jennings and Wlezien Reference Jennings and Wlezien2018). The jargon style may limit consumers’ self-perceived ability to understand political news and apply it, thus reducing trust in the media (Edgerly Reference Edgerly2022). In each case, disparities in preferences and knowledge between the politically engaged and the politically disengaged may produce heterogeneous effects on media trust from exposure to these contemporary styles. I therefore consider whether the following are true:

Hypothesis 5: Exposure to under-informative styles of political news coverage reduces overall media credibility.

Hypothesis 6: Individual political engagement moderates the effect of news styles on media perceptions, such that (a) less engaged individuals rate the media as less credible and (b) more engaged individuals rate the media as more credible.

Experimental Design

I conduct a pre-registered survey experiment that exposed participants to news content that manipulated style but held the underlying information constant.Footnote 9 I recruited a national non-probability sample of 2,249 US adults via the Prolific survey respondent marketplace. The survey was fielded on 21 and 22 September 2023. Respondents were paid $2.50 to complete the survey, which took the median respondent sixteen minutes. I removed sixteen observations for failing multiple pre-registered quality checks; this procedure provided a final sample for analysis of n = 2, 233. Supplementary Material (SM) Section B provides additional details about the sample composition and exclusion criteria.Footnote 10

After providing informed consent, respondents answered background questions regarding their news consumption habits and political opinions. I use a subset of these responses to estimate baseline engagement with politics. I adapt the approach from Johnston et al. (Reference Johnston, Lavine and Federico2017) to create a pre-registered weighted political engagement index from three components. The first component is a simple average of two questions, each measured on a five-point scale: their level of attention to politics and their interest in political campaigns. The second component is the self-reported number of days per week that the respondent consumes news about politics. The third component is the number of correct answers to seven factual political knowledge questions that vary widely in difficulty (see SM A.3). For each index component, I rescale the component to vary between 0 and 1. As pre-registered, I then weight the first two (subjective) components at 0.25 each and the (objective) knowledge component at 0.5 to generate the final index score for each individual.Footnote 11

Respondents were assigned to one of five conditions by simple random assignment. These conditions correspond to the four under-informative styles under study (conflict, jargon, prediction, or clickbait) and the ‘public interest’ style (held as the control condition). Following treatment assignment, respondents sequentially viewed three vignettes that resemble news articles. Each article drew on real news coverage to report a developing news story from the fielding period. One story discussed the passage of a Texas law that gives the Texas Secretary of State the power to remove locally elected officials from office and directly administer elections specifically in Harris County (home to Houston). Another story discussed ongoing court proceedings over Congressional redistricting in New York, in which Democrat lawmakers sought to draw more politically favorable district lines. The remaining story discussed stalled attempts by Congress to impose a code of ethics on Supreme Court justices after revelations of lavish gifts came to light. Each respondent viewed all three vignettes, with the order of the three stories randomized.

These three topics were selected for their normative and policy importance: voters generally dislike when their elected representatives are summarily removed from office by unelected bureaucrats, when elected representatives choose their voters (instead of the reverse), or when public corruption goes unaddressed. Together, the stories cast both parties in a poor light vis-à-vis democratic norms: while the Texas story clearly implicates Republicans for norm-breaking behavior, the New York story does the same for Democrats, and the Supreme Court ethics story is (at least in theory) non-partisan. The topics also vary in their obscurity; both of the state-level stories are less likely to be familiar to the broader US population,Footnote 12 whereas substantial media coverage of the ongoing ethics crisis at the Supreme Court likely garnered broader awareness.

Each vignette was carefully tailored to maintain content equivalence across conditions, but with the news style of the article manipulated. The headline provided the first signal of the story’s approach to coverage: headlines noted partisan sparring in the conflict condition, used specialized terms in the jargon condition, suggested probable final outcomes in the prediction condition, hinted enticements in the clickbait condition, and bluntly stated each story’s normative importance in the public interest condition. The first paragraph then introduced the story’s main points with a language and structure that was uniform across conditions, but with key phrases manipulated to highlight different aspects of the story as its central implication. For example, in the jargon condition, the Texas story noted ‘key implications for McCarthy’s tenure in the 2024 elections’, whereas in the public interest condition swapped ‘democratic rights’ for ‘McCarthy’s tenure’. Four short body paragraphs followed this introductory paragraph (64 to 69 words each). Each paragraph adopted one of four specific coverage styles to discuss the news story (conflict, jargon, prediction, or public interest; as I discuss below, the clickbait style did not have an associated body paragraph). That is, the conflict paragraph discussed the story in win/loss terms for Democrats and Republicans, the jargon paragraph employed specialized terminology and uncontextualized characters, the prediction paragraph provided analysis on how subsequent events might play out, and the public interest paragraph focused on the story’s policy and normative implications. For example, in the New York gerrymandering story, the conflict paragraph notes that ‘[b]oth parties have been quick to accuse the other of hijacking the normal process’, the jargon paragraph discusses the back-and-forth of ‘litigation over New York’s Congressional district maps’ and that ‘an appellate court ruled in Democrats’ favor in July’, the prediction paragraph portends that the court battle ‘could doom Republicans’ hopes of keeping their slim majority’, and the public interest paragraph provides context that the ‘current districts were drawn by a neutral, court-appointed official to make elections more competitive’ and that gerrymandering ‘is forbidden by the state constitution’. The full text of each vignette is provided in SM B.3.

To maintain strict equivalence in terms of information content across conditions, all four paragraphs for each story were shown in identical form to all respondents. To manipulate style, these body paragraphs were displayed in a different order: the first body paragraph corresponded to the respondent’s assigned condition (for example, respondents assigned to the jargon condition always saw the jargon paragraph first), and the remaining three paragraphs were randomly ordered (at the respondent–article level). Thus, all respondents in all conditions were exposed to (and given an opportunity to consume) any of the information contained within a given vignette, but some information was given priority placement.

The clickbait condition employed a slightly different randomization procedure. Clickbait is conceptualized primarily as provocative headlines (or provocative ledes) that spur additional engagement, but the body content of a clickbait article need not share these same characteristics. Rather than presenting a clickbait body paragraph, I provide only a clickbait-style headlineFootnote 13 and fully randomize the other elements of the vignette. Two key phrases in the introductory paragraph are selected with independent random draws from those used in the other four conditions, and all four body paragraphs that follow are randomly ordered. The clickbait condition thus still presents all of the same informational content, but unlike the other conditions the prominence of any particular piece of information is constant in expectation.

Finally, I vary intensity of news exposure by limiting the amount of time that respondents can view each (randomly ordered) story. Specifically, I provide an opportunity for an in-depth read with no time constraint on the first vignette, encourage some skimming behavior with a 60-second limit on the second vignette, and simulate a more rushed or partial exposure with a 30-second limit on the third vignette. Respondents were informed of these limits (or lack thereof) in advance. The median respondent viewed the three vignettes for 85 seconds, 60 seconds, and 30 seconds, respectively.Footnote 14 Because the vignettes are all of similar length (between 307 and 319 words each) and the stories are randomly ordered, the variation in maximum exposure time allows me to evaluate heterogeneity in treatment effects between a (potentially) in-depth read of the first story and increasing degrees of skimming behavior in the subsequent stories.Footnote 15

While imposing a strict time limit is artificial, competing needs for one’s time are all too common. Most news consumers engage in substantial skimming when not faced with explicit time limits, particularly on digital devices (Dunaway and Searles Reference Dunaway and Searles2023) and in online spaces that generate incidental exposure, where many consumers even share headlines and links without actually having consumed much (or any) of the underlying content (Ward et al. Reference Ward, Zheng and Broniarczyk2023). In contrast, respondents to a paid research survey have artificial incentives to read thoroughly. The explicit time limits thus act to prompt behavior that is more similar to everyday news consumption than what the unusual experimental setting might otherwise induce.

Outcome Measures

Following exposure to each individual vignette, I asked respondents several questions about the story they just viewed. After viewing each story, respondents were asked the extent to which they agree or disagree that the story was ‘engaging’, ‘informative’, ‘useful’, and ‘newsworthy’, with each item measured on a balanced seven-point scale from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. As pre-registered, I combine the informative, useful, and newsworthy items into a additive index of perceived informativeness (Cronbach’s α = 0.93, indicating excellent internal reliability), rescaled to vary between 0 and 1.Footnote 16

To measure respondents’ ability to recall key information from the story, respondents were then asked to answer four multiple-choice recall questions about key points discussed in the respective stories. Each question included one correct recall option alongside four decoy options, as well as an ‘I don’t know’ option. As shown in SM A.3, item response theory models using these items exhibit good discrimination parameters for each item and a useful range of difficulty parameters across each story’s four items. For each vignette viewed, I sum the number of correct answers to the four recall questions specific to the story presented, forming an individual measure of information recall (0 to 4) for each of three vignettes with varying time constraints (no time limit, a slight time constraint of 60 seconds maximum, and a severe constraint of 30 seconds maximum, respectively).

All recall questions for each story relate to points made most explicit in the public interest (control) paragraph, though inferences about these same points could certainly be drawn from other parts of the article regardless of the treatment condition. Concentrating the recall items on information most clearly presented in the control paragraph reflects the theoretical framework: I argue that typical styles of political news coverage are ‘under-informative’ because they obscure key information about policy issues and democratic norms that are relevant to citizens’ political decision making. By placing information about partisan maneuvering or polling predictions at the fore, news producers are necessarily relegating other information further down the page. Furthermore, the headline and introductory framing of an article help guide the consumer to what the news producer considers most worth reading—and this need not be what is most informative for democratic participation. Thus, while drawing the recall items primarily from the public interest paragraph generates a mechanical effect on recall from paragraph positioning (which is partially a function of treatment assignment), there may also be a non-mechanical effect produced by what the headline and lede suggest the reader should pay most attention to. That is, in the wild, where writers choose to position substantive versus entertaining elements of their political coverage may draw consumers’ attention to one thing over the other, even when taking the time to engage with an entire article.

I measure general confidence in the media with three items, adapted from Madson and Hillygus (Reference Madson and Hillygus2020), which ask respondents how often they consider the media to be ‘accurate’, ‘trustworthy’, and ‘informative’, each on a five-point scale from ‘never’ to ‘always’. I combine these three items into an additive index (rescaled to vary between 0 and 1), measured both pre-treatment and after all stories are viewed (pre-treatment index Cronbach’s α = 0.88, indicating good internal reliability). Pre- and post-treatment measurement allows me to assess within-subject change in general attitudes towards the media as a function of repeated exposure to different styles of news coverage.

Finally, I measure support for three policies related to key democratic norms both pre-treatment and after all vignettes are completed. Specifically, I ask respondents whether they would support or oppose certain norm-breaking actions by legislators, each on a balanced six-point scale from ‘strongly oppose’ to ‘strongly support’, which I combine into a single additive index (Cronbach’s α = 0.57, indicating minimally acceptable internal reliability), rescaled to vary between 0 and 1. These three actions are: the adoption of geographically targeted election laws (that is, different election rules for different populations within the same jurisdiction), gerrymandering legislative districts for partisan gain, and imposing a code of ethics on court officials (reverse-coded).Footnote 17 The pre- versus post-treatment measures assess within-subject change in support for norm-breaking policies as a function of repeated exposure to a given style of coverage.

Results

I test the hypotheses by estimating average treatment effects (ATEs) from exposure to ‘under-informative’ styles of political news. Specifically, I regress each outcome on a binary indicator for treatment exposure pooled across all four under-informative styles (public interest control = 0, under-informative style = 1). To improve the precision of the estimates, I include covariates for party identification, liberal–conservative ideology, gender, race, education, income, and age. Because two of the vignettes focus on stories in specific states, I also include fixed effects for residency in Texas and residency in New York to adjust for potential differences in familiarity and interest among these audiences relative to other consumers. Finally, because treatment effects on recall and perceived informativeness are estimated for each vignette individually (by length of exposure), I include fixed effects for story topic (Texas and Supreme Court, with New York held as the reference category). As the hypotheses specify directional expectations, I use one-tailed tests for significance unless otherwise noted.Footnote 18

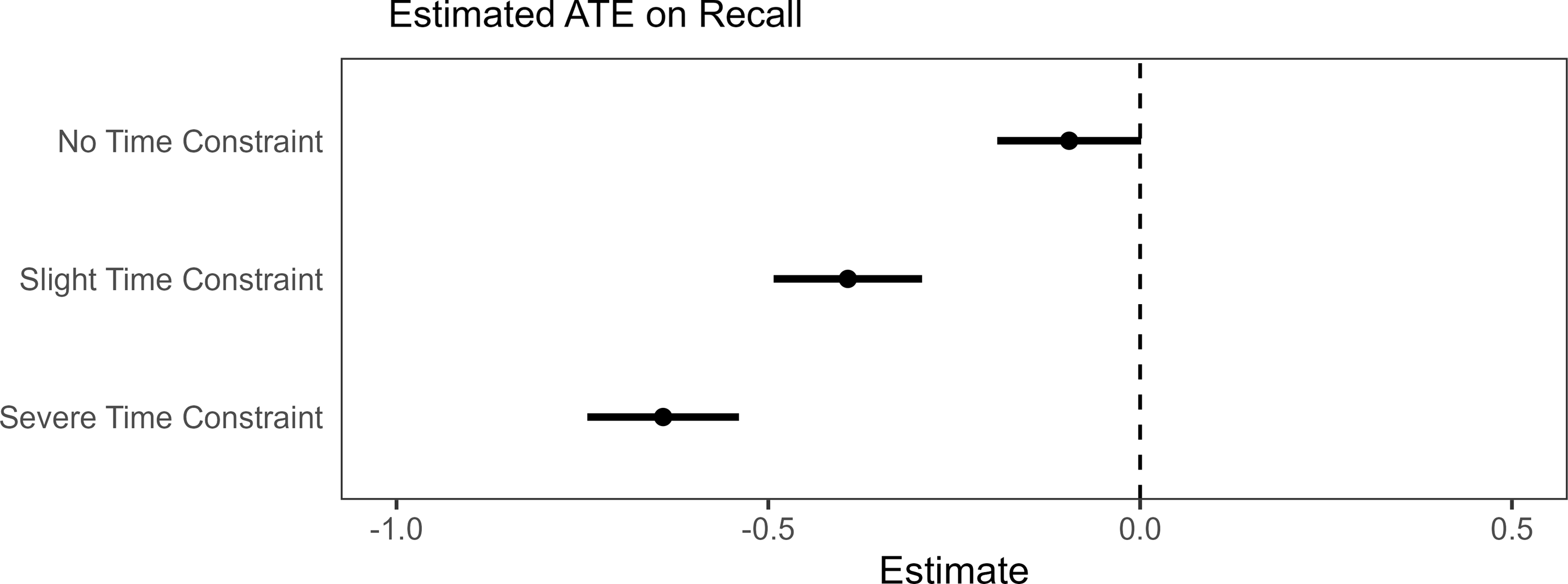

I first test the effect of exposure to typical styles on respondents’ ability to recall key information from the news stories. H1 expects that the under-informative styles will reduce information recall relative to the public interest style (the control). This is indeed what I find. For each of the three vignettes respondents viewed, Figure 1 shows the estimated ATE of exposure to an under-informative style on the number of recall questions respondents were able to answer correctly.Footnote 19 For the first vignette, respondents could view the story for as much time as desired, and thus faced little or no time constraint. Under these conditions, an under-informative style has a small negative effect on recall (estimate −0.095 correct answers, one-tailed p = 0.052), as shown in the top row of Figure 1. Under conditions of a slight or severe time constraint for the second and third vignettes (shown in the middle and bottom rows of Figure 1, respectively), average recall declines much more substantially: by −0.393 correct answers under a slight time constraint (one-tailed p < 0.001) and by −0.641 correct answers under a severe time constraint (one-tailed p < 0.001). These are substantively large penalties to recall, reducing total correct answers by as much as one third for the median respondent. Typical approaches to political news coverage are indeed under-informative, especially when exposure is brief.

Figure 1. The estimated ATE on information recall following exposure to under-informative news (pooled treatment) under different time constraints. Error bars indicate 90 percent confidence intervals. All outcomes use the full sample (n = 2, 233). For full results, see SM Table A.1.1.

Before continuing, it is worth considering whether these penalties derive from a purely mechanical effect of paragraph order—that is, where the public interest paragraph is positioned in the body of the vignette. Recall that the public interest ‘control’ condition positions the public interest paragraph as the first body paragraph (after the headline and introductory lede), whereas in most treatment conditions this paragraph is randomly positioned further down. Because the recall questions focused on information that was stated most clearly and explicitly in the public interest paragraph for each story, simple ordering effects might explain the negative impact on recall. Note that a purely mechanical effect would still align with the theoretical framework: I argue that contemporary styles of news coverage are under-informative in part because they relegate policy and governance information to the bottom of the ‘inverted pyramid’. That said, an additional psychological effect—for example, from the style’s signal of what information the reader should consider important and pay attention to—would compound this problem.

In SM A.5, I take advantage of the complete randomization of paragraph ordering in the clickbait treatment condition to compare pure ordering effects against the combined psychological and ordering effects present in other treatments. I find that the negative effect on recall from exposure to the conflict, jargon, or prediction styles is more severe than a simple ordering effect would imply. While there is clearly some mechanical effect of paragraph ordering, a substantial non-mechanical effect goes well beyond this baseline penalty. What journalists choose to emphasize early on suggests to consumers which information is most important, what to pay attention to, and how to interpret everything that follows, thus influencing how readers engage with content later in the story. When the news style does not prioritize important policy-relevant and normative information, recall of such information suffers above and beyond the mechanical function of reduced exposure from content ordering.

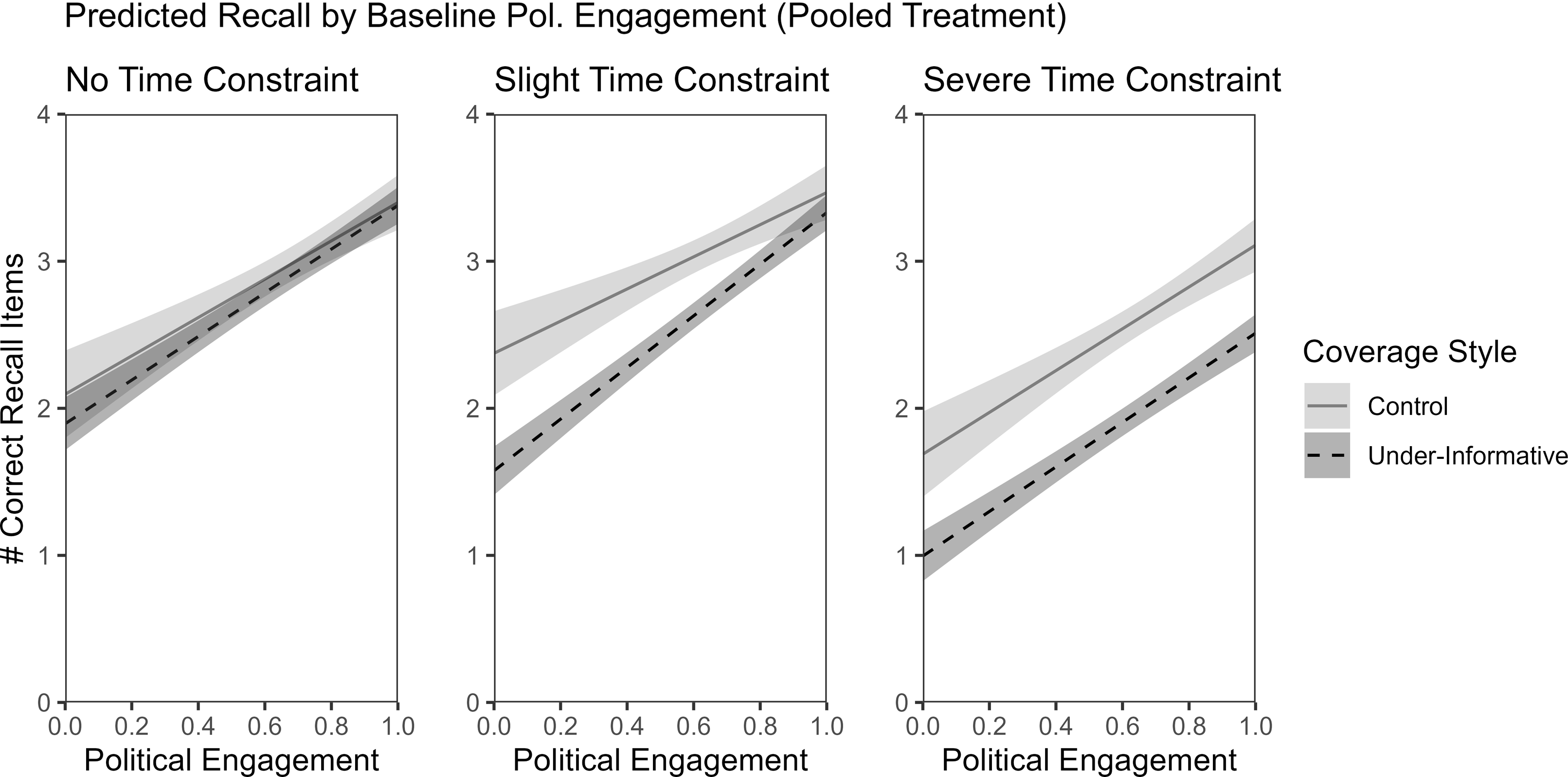

I next consider the importance of baseline political engagement—that is, respondents’ prior knowledge and habitual attention to politics. Do under-informative styles of news affect consumers’ ability to recall information equally, regardless of their baseline engagement? H2 expects that negative effects on recall will be primarily concentrated among less engaged consumers—those who would typically encounter political news incidentally or infrequently. To test H2, I add baseline political engagement as a covariate and add a linearFootnote 20 interaction term between baseline engagement and the binary pooled treatment indicator (results are reported in SM Table A.1.3). In support of expectations, I find that the coefficient on the treatment indicator is sharply negative when respondents are forced to skim (slight time constraint estimate −0.799 correct answers, one-tailed p < 0.001; severe time constraint estimate −0.692 correct answers, one-tailed p < 0.001), indicating large declines in recall among the less politically engaged. However, high baseline engagement only sometimes enables consumers to overcome the learning penalty when exposed to under-informative styles—and these styles never produce superior recall than the public interest style, even among the most politically engaged. Under a slight time constraint, high-engagement respondents exposed to an under-informative style performed only slightly worse, whereas low-engagement respondents suffered large penalties (treatment–engagement interaction estimate 0.663 correct answers, one-tailed p = 0.008). In contrast, under a severe time constraint, consumers across the engagement spectrum suffered large penalties when exposed to under-informative styles (interaction estimate 0.094 correct answers, one-tailed p = 0.365). In other words, ‘speaking their language’ does not spur increased news learning from the core audience.

To show this dynamic more clearly, Figure 2 presents the predicted number of correct answers on the recall items in the treatment or control conditions under each time constraint. The positive slopes show that high-engagement respondents outperform low-engagement respondents across the board, reflecting some degree of previous knowledge and ability to make accurate inferences from limited information. But the time available to process a story does matter. Given ample time, respondents at all levels of engagement performed nearly (but not quite) as well regardless of coverage style, as shown in the left-most panel. In the middle panel, under a slight time constraint, the most engaged respondents still performed almost as well regardless of style, but moderate- and low-engagement respondents performed much worse when exposed to an under-informative style. Under a severe time constraint—having only 30 seconds to process the story—respondents at all engagement levels performed much worse when presented with an under-informative style, as shown in the right-most panel.

Figure 2. The predicted number of correct answers on recall items under each time constraint, conditional on baseline political engagement and treatment assignment. Shaded areas indicate 90 percent confidence intervals. All outcomes use the full sample (n = 2, 233). For full results, see SM Table A.1.3.

Though most (but not all) of these effects are mechanical functions of limited exposure, this again reflects the theoretical framework: how news outlets choose to package their political coverage affects what kinds of political information (and how much) consumers can learn from both full and limited exposure. Relegating public interest information to later in a news story harms political learning, especially when engagement is more superficial, as tends to be the case for mobile and social media news browsing (Dunaway and Searles Reference Dunaway and Searles2023; Molyneux Reference Molyneux2018).

Perceptions of Under-Informative News

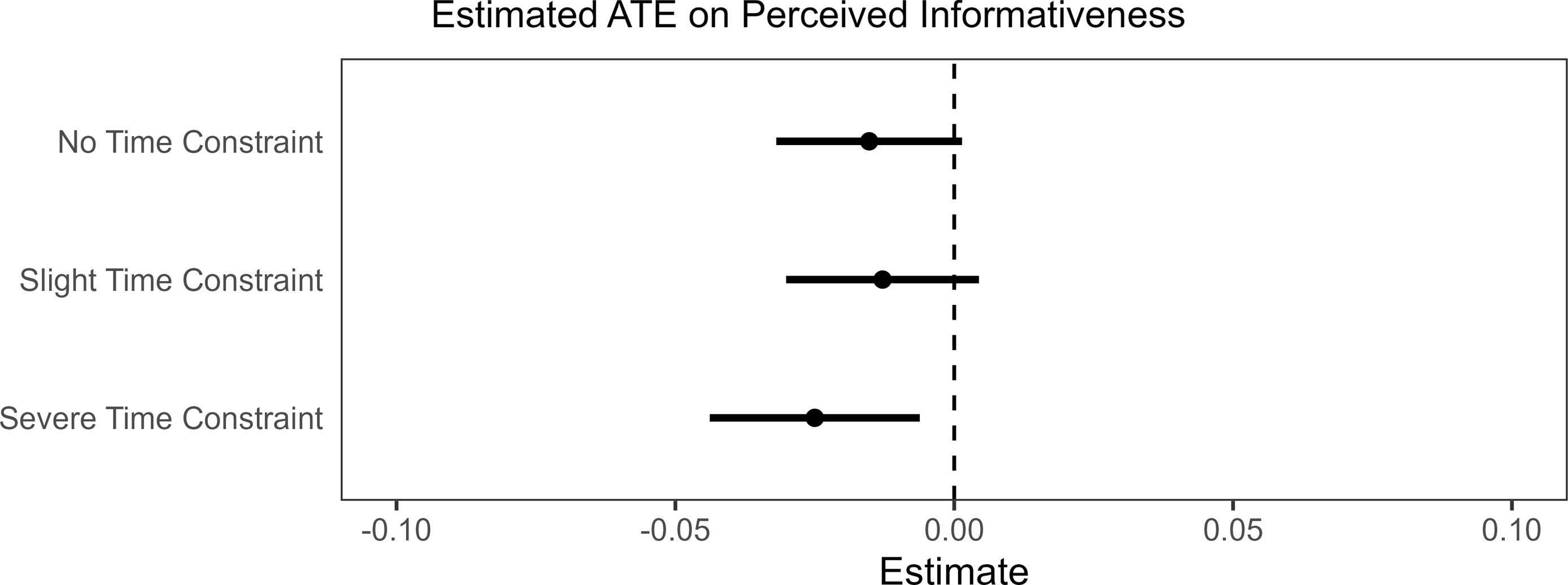

I now turn to respondents’ perceptions of under-informative news. Are news styles that focus on conflict, use insider jargon, conduct predictive analysis, or dangle clickbait perceived as less informative by their readers, as H3 expects? Regressing the perceived informativeness index for each vignette on pooled treatment (reported in SM Table A.1.5), I find that the effect is small and mostly insignificant, as shown in Figure 3. In the most severe case, when exposure is most constrained, the estimated ATE is −0.025 (one-tailed p = 0.015). Though statistically significant, this is a substantively small change from a baseline of 0.698 in the control condition. When time is not constrained or only slightly so, the estimated ATE on perceived informativeness is even smaller and not statistically significant (one-tailed p = 0.066 and p = 0.111, respectively).

Figure 3. Figure displays the estimated average treatment effect (ATE) on perceived informativeness of under-informative news (pooled treatment) under each time constraint. Error bars indicate 90 percent confidence intervals. All outcomes use the full sample (n = 2, 233). For full results, see SM Table A.1.5.

Nor does this minimal effect on perceived informativeness vary by baseline political engagement. Whereas H4 expects that less (more) engaged respondents would view the treatment styles as less (more) informative, I find that when adding an interaction with political engagement, neither the coefficient on the treatment indicator nor the interaction is statistically significant (see SM Table A.1.6). Regardless of their baseline engagement, respondents do not seem to view ‘under-informative’ news stories as more or less informative than public interest style news.

I find similar results when analyzing effects on broader media credibility. Exposure to three news articles written in an under-informative style did not affect respondents’ perceptions of the media as accurate, informative, or trustworthy, as shown in SM Table A.1.7. And once again, this (lack of an) effect does not vary by baseline political engagement; respondents across the engagement spectrum have similar views of the media’s credibility, and this was not affected by exposure to different styles of coverage.

Support for Democratic Norms

Beyond their direct effects on the public’s knowledge of politics, one troubling possibility is that their relative minimization of democratic norms and norm-breaking (in favor of ‘game’ elements such as partisan clashes, legal maneuvering, and election forecasting) might impact the public’s support for future norm-breaking. I test this possibility by regressing the post-treatment index of support for norm-breaking policies on the treatment indicator, controlling for the pre-treatment index value.Footnote 21 In contrast to the under-informative styles, I find that exposure to public interest style coverage lowers support for norm-breaking behavior, thus strengthening support for democratic norms (estimated ATE −0.018, two-tailed p = 0.005). On average, those exposed to the public interest style vignettes reduced their support for these norm-breaking practices by 0.019, while those assigned to an under-informative style barely move at all (by −0.001 on average). This is a small but substantively meaningful change, on the order of a tenth of a standard deviation (mean support pre-treatment is 0.185, standard deviation 0.194). Public interest style coverage meaningfully helps reinforce democratic norms, whereas under-informative styles do not.

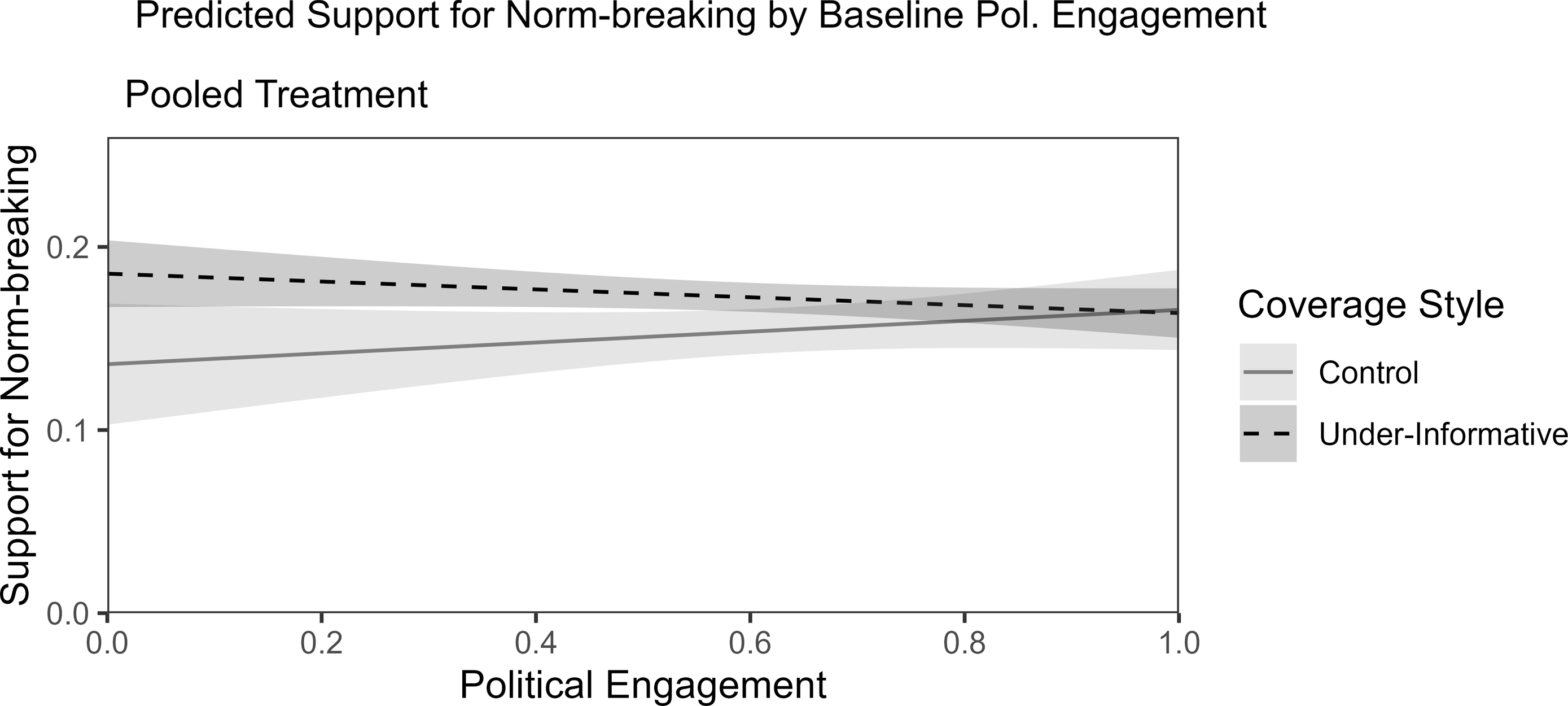

These salutary, norm-reinforcing effects are concentrated primarily among the less politically engaged. I extend the above model by interacting the treatment indicator with baseline political engagement (see SM Table A.1.8); Figure 4 displays the predicted post-treatment position on the norm-breaking policy support index by baseline political engagement and treatment assignment. On the right-hand side of the figure, the treatment style appears to have no effect on high-engagement respondents’ post-treatment support for norm-breaking behavior. In contrast, on the left-hand side of the figure, we see that less politically engaged respondents exposed to public interest style stories report substantially less support for norm-breaking behavior than those exposed to under-informative styles.

Figure 4. The predicted post-treatment support for norm-breaking policies, conditional on baseline political engagement and treatment assignment. Shaded areas indicate 95 percent confidence intervals. All outcomes use the full sample (n = 2, 233). For full results, see SM Table A.1.8.

Variation by Style

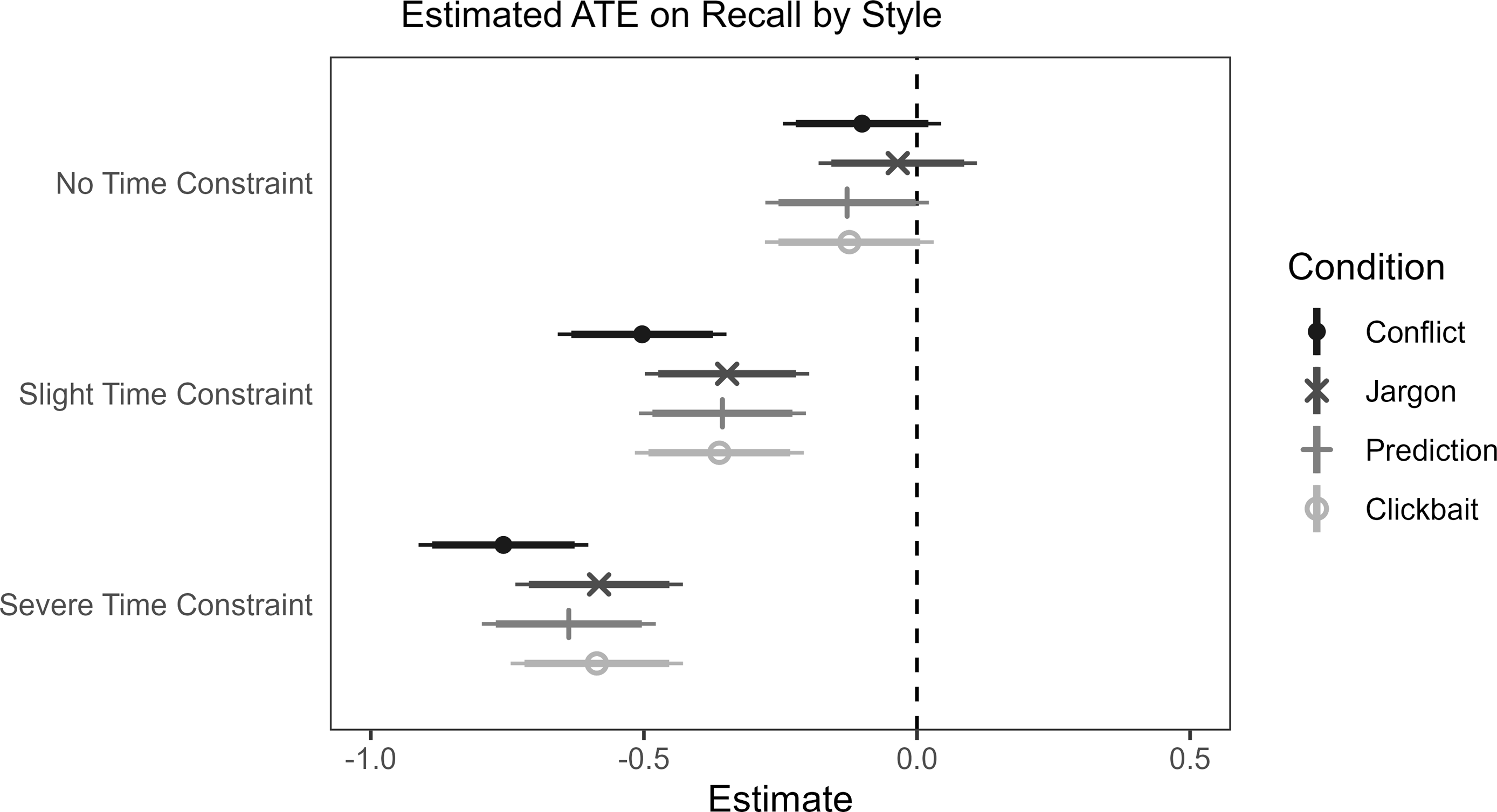

Are some under-informative styles more detrimental than others? To test this possibility, I regress recall on a binary indicator for each treatment style (plus control covariates).Footnote 22 Figure 5 displays the estimated ATE of each under-informative style on information recall following exposure under each time constraint. The point estimates for each style are remarkably similar within time constraints. When facing no time constraint, respondents exposed to a prediction style (estimate −0.128, one-tailed p = 0.047) or clickbait style (estimate −0.124, one-tailed p = 0.058) exhibit a slight reduction in recall relative to the control, but these two styles are not significantly different from the conflict or jargon treatments (which are not significantly different from the control). Under a slight or severe time constraint, though, respondents exposed to all four treatment styles performed much worse than the public interest control. When exposure is constrained, the conflict style stands out for the sharpest declines in recall—a concerning difference, given the prevalence of conflict styles in news coverage (Dunaway and Lawrence Reference Dunaway and Lawrence2015). Respondents in the conflict condition performed worse under a slight time constraint than those in the jargon, prediction, and clickbait conditions (F-tests for equivalence p = 0.046, p = 0.064, and p = 0.078, respectively). Under a severe time constraint, conflict-treated respondents performed much worse than those in the jargon and clickbait conditions (F-tests for equivalence p = 0.028 and p = 0.038, respectively; p = 0.150 versus the prediction condition).

Figure 5. The estimated average treatment effect (ATE) on information recall following exposure to under-informative news for each treatment style, by variation in time constraint. Thick (thin) error bars indicate 90 (95) percent confidence intervals. All outcomes use the full sample (n = 2, 233). For full results, see SM Table A.1.2.

The treatment styles also differ in their effects on support for norm-breaking behavior (see SM Table A.1.8). Respondents assigned to the jargon style, which repackages many of the same key details as the public interest style but in more arcane language, show similar post-treatment support for norm-breaking behavior to the control group (estimated ATE 0.006, two-tailed p = 0.439), but the other three under-informative styles all show substantial increases in support for norm-breaking (conflict estimate 0.021, two-tailed p = 0.007; prediction estimate 0.024, two-tailed p = 0.003; clickbait estimate 0.021, two-tailed p = 0.009).

Discussion

Contemporary styles of political news, which I term ‘under-informative’, struggle to communicate information ‘central to issues of governing’ (Patterson Reference Patterson1993, 29) to the public. In comparison to the public interest style, which prioritizes communicating such information as directly and accessibly as possible, under-informative styles make extracting this information more difficult. Only consumers who have the capacity or interest to devote significant time to a news story (Stroud Reference Stroud2017), or who benefit from extensive prior engagement with political news (or both), are able to recall a similar level of key information from an under-informative news article. By burying information about public policy, governance, norms, and the political values behind flashier content, under-informative styles substantially reduce the probability that consumers will encounter that information and encode it in memory.

These risks are especially pronounced for consumers who are less habitually engaged with political news. In this tightly controlled experimental study, respondents with lower political engagement at baseline were able to recall fewer key pieces of information from under-informative styles when faced with even just a slight time constraint, whereas the most engaged respondents were primarily affected when presented with a severe time constraint. Several possible mechanisms might enable high-engagement consumers to more easily pick out critical information. Faster reading speeds and higher reading comprehension may enable them to simply absorb information more quickly and completely. Enhanced familiarity with the terminology and structure of political news may make the content more accessible and interpretable (Zaller Reference Zaller1992). Greater prior political knowledge may enable more accurate inferences and extrapolations from limited or veiled information. A larger store of political information in procedural memory may facilitate encoding new information and enable recall to working memory (Zaller and Feldman Reference Zaller and Feldman1992). But regardless of the precise mechanism at work, there are still limits: even for the most politically engaged consumers, very brief encounters with under-informative news will impart little information that is relevant for public citizenship.

There is reason to believe that very brief encounters with political news are the rule rather than the exception in today’s media environment—even for politically engaged consumers. While near-infinite consumer choice has allowed many citizens to opt out of directly consuming political news (see, for example, Prior Reference Prior2007), the growth of social media (as well as other forms of digital media, such as podcasts, news aggregators, and mobile push alerts) presents significant new opportunities for outlets to reach consumers incidentally, or through intentional but brief news browsing sessions (Dunaway and Searles Reference Dunaway and Searles2023; Molyneux Reference Molyneux2018). Given these channels’ prevalence among young people (Pew Research Center 2023 a), the evidence presented here may suggest that under-informative news styles may contribute to both young voters’ reduced political participation (Holbein and Hillygus Reference Holbein and Hillygus2020) and greater tolerance for anti-democratic behavior (Frederiksen Reference Frederiksen2024). Reorienting to instead succinctly communicate what the public most needs to know may help fulfill the Fourth Estate’s normative purpose of facilitating mass democratic participation.

Why is the public interest approach not the norm, given journalists’ professionalized ideals and robust scholarly evidence that more informative news leads to better democratic outcomes (Soroka and Wlezien Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010, Reference Soroka and Wlezien2022)? The null effects on consumer perceptions of under-informative news can provide some insight into the economic dynamics at work in the current under-informative news equilibrium. If consumers do not perceive contemporary styles of coverage to be less informative, the most consistent and habitual consumers may feel no compunction in preferring them for their greater entertainment value. Faced with significant economic pressures to produce more engaging content (Bennett Reference Bennett2003; Hamilton Reference Hamilton2004; Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Norpoth and Hahn2004) and presented with demand signals dominated by news junkies (Krupnikov and Ryan Reference Krupnikov and Ryan2022; McGregor Reference McGregor2019; Trexler Reference Trexler2024; Tyler et al. Reference Tyler, Grimmer and Iyengar2022), news outlets would have few incentives beyond professional norms to communicate the day’s news through the objectively more informative lens.

Competing normative pressures (that is, regarding balance and neutrality) and fears of upsetting some partisan consumers may further discourage journalists from employing the public interest style to cover partisan threats to democracy (Jang and Kreiss Reference Jang and Kreiss2024; Peterson et al. Reference Peterson, McGregor and Block2025). Yet this study provides empirical evidence that the public interest style strengthens support for democratic norms, especially among less engaged consumers, whereas under-informative styles do little to highlight threats to democratic norms. This salutary benefit offers an additional empirical reason to privilege the media’s democratic functions over its professional traditions of balance.

Considered together, the public interest style’s positive effects on both learning and support for democratic norms suggests that it offers the industry a potential path to fulfilling its core democratic purpose—but one that is not without risks in an already difficult business environment. This challenge elevates the critical importance of identifying alternative models for sustaining journalism that do not depend on the clicks and pocketbooks of a highly engaged minority (Trexler Reference Trexler2026; Usher Reference Usher2021), so that the Fourth Estate can better serve the needs and interests of the public as a whole.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123425101300.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/GCFXTO.

Acknowledgments

I thank Alex Coppock, Johanna Dunaway, Ben Epstein, Jon Green, Sunshine Hillygus, Christopher Johnston, Andrew Kenealy, Kevin Kiley, Shannon McGregor, Eric Merkley, Phil Napoli, Trent Ollerenshaw, Erik Peterson, Mallory SoRelle, Stuart Soroka, Emily Thorson, and Stephen Vaisey for helpful comments that improved the research. I also thank seminar participants at workshops at Duke University and the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, as well as panel participants at the 2024 Midwest Political Science Association Conference, the 2024 International Society of Political Psychology Annual Meeting, and the 2024 American Political Science Association Annual Meeting.

Financial support

This research was generously supported by a grant from the James S. and John L. Knight Foundation, and by a J. Peter Euben Graduate Research Grant in Political Science from the Worldview Lab at the Kenan Institute for Ethics at Duke University.

Competing interests

None to disclose.

Ethical standards

This human subjects research was conducted in accordance with protocol #2024-0002 approved by the Campus Institutional Review Board of Duke University.