1. Research question

Competition is in the air we breathe. Competition drives the free market economy, as firms compete for customers, service providers compete for clients, and workers compete for jobs. Competition drives democratic political systems by way of determining the outcomes of elections. Athletes compete for victory and glory, students compete for admission to prestigious schools, and researchers compete for funding. Scientists, film makers, artists, and architects compete for awards, and reality TV contestants strive to prepare the most delicious dish, dance the best dance, and get to stay on the island. The list goes on.

Classically, competition motivates people to outperform their counterparts, typically through superior skill or greater effort. In the current studies, we are interested primarily in the dark side of competition, namely, will competitors avail themselves of the option to sabotage their counterparts, even at a cost to themselves? Does the risk of sabotage frustrate competitive effort, or does it rather spur extra effort? For the effects of competition (bright and dark) to obtain, how intense does the competition need to be? Must winning come with a tangible benefit? Does pure social comparison suffice? Might participants engage in competitive behavior when they merely know that another person is performing the same task, absent ever receiving feedback about that person’s performance?

2. Competitive behavior

Competitions are classically conceived as the deliberate participation in formal and structured contests that accrue zero-sum tangible rewards to the contestants (Bronson and Merryman, Reference Bronson and Merryman2014; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Cron and Slocum1998; Haran and Bereby-Meyer, Reference Haran, Bereby-Meyer, Garcia, Tor and Elliot2024; Tor and Garcia, Reference Tor and Garcia2023). The power of competition and the grip that it holds on our imagination stem from the fact that competitions tend to generate substantial rewards based on even the slightest differences in performance.

Given the outsized and ubiquitous role that competition plays in our social worlds, it is no surprise that it has attracted a considerable amount of research attention from experimentalists working both in economics (e.g., Bull et al., Reference Bull, Schotter and Weigelt1987; Orrison et al., Reference Orrison, Schotter and Weigelt2004) and psychology (e.g., Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Tor and Gonzalez2006; Harackiewicz et al., Reference Harackiewicz, Abrahams and Wageman1987; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Lin and Zhang2019; see Haran and Bereby-Meyer, Reference Haran, Bereby-Meyer, Garcia, Tor and Elliot2024). A common insight derived from both bodies of research is that competitive settings trigger motivations that tend to boost the effort exerted toward the goal of prevailing (Garcia and Tor, Reference Garcia and Tor2009; Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Tor and Schiff2013; Haran and Ritov, Reference Haran and Ritov2014; Kilduff, Reference Kilduff2014; Murayama and Elliot (Reference Murayama and Elliot2012); Piest and Schreck, Reference Piest and Schreck2021). Economists have focused on competitive incentive structures, variations in tournament rules, and deviations from normative principles (e.g., Bull et al., Reference Bull, Schotter and Weigelt1987). Topics of interest include the dispersion of the value of the prize (Harbring and Irlenbusch, Reference Harbring and Irlenbusch2011), the distribution of prizes among multiple winners (Amaldoss et al., Reference Amaldoss, Meyer, Raju and Rapoport2000), and the effect of disparities in opening positions (Zizzo and Oswald, Reference Zizzo and Oswald2001). Psychologists have focused primarily on the feelings, perceptions, motivations, and intentions of actors in competitive situations (Haran and Bereby-Meyer, Reference Haran, Bereby-Meyer, Garcia, Tor and Elliot2024; Tor and Garcia, Reference Tor and Garcia2023). Topics of interest have included the proximity to a standard (Garcia and Tor, Reference Garcia and Tor2007; Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Tor and Gonzalez2006), the temporal dynamics of competitive behavior (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Lin and Zhang2019), the size of the competitor field (Garcia and Tor, Reference Garcia and Tor2009), and individual differences in competitive behavior (Reese et al., Reference Reese, Garcia and Edelstein2022; Spence and Helmreich, Reference Spence, Helmreich and Spence1983).

Incentivized competitions account for many of the examples mentioned above, such as in the free market economy, political elections, workplace promotions, legal disputes, and professional sports. In these instances, competitive behavior is motivated straightforwardly by the rewards that are bestowed on the winner. Yet, tangible rewards are not necessary to motivate competitive behavior. People engage quite regularly in competitive behavior in contests that are devoid of any such rewards (Charness et al., Reference Charness, Masclet and Villeval2014; Tor and Garcia, Reference Tor and Garcia2023). Such is the case when siblings compete for the love and attention of their parents and divorced parents compete for the approval of their children, members of a swim team race one another in practice with a desire to come out ahead, high school classmates vie for popularity, and street basketball players strive for the respect of their peers. Indeed, studies show that competitive behavior is observed when people are merely ranked on the basis of their relative performance (Azmat and Iriberri, Reference Azmat and Iriberri2010; Charness et al., Reference Charness, Masclet and Villeval2014; Kosfeld and Neckermann, Reference Kosfeld and Neckermann2011; Rustichini, Reference Rustichini2008).

The dominant psychological explanatory framework for competitive behavior in the absence of tangible rewards is social comparison theory (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Tor and Schiff2013; Haran and Bereby-Meyer, Reference Haran, Bereby-Meyer, Garcia, Tor and Elliot2024; Suls and Wheeler, Reference Suls and Wheeler2012). As postulated by Leon Festinger (Reference Festinger1954), people habitually seek information about others, against whom they compare themselves. For one, comparative knowledge of one’s performance and abilities assists people in the evaluation of their qualities and thus helps maintain a stable and accurate self-view (see Mussweiler et al., Reference Mussweiler, Corcoran, Crusius and Chadee2011; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Wayment, Carrillo, Sorrentino and Higgins1996). Such self-evaluation helps calibrate one’s relative position and abilities, and thus informs judgments and decisions pertaining to the subject of the competition (Tor and Garcia, Reference Tor and Garcia2023). Second, people engage in social comparison to serve the ubiquitous need for maintaining a positive self-image (Alicke and Sedikides, Reference Alicke and Sedikides2009). One way to satisfy this self-enhancement motive is by comparing oneself to less successful and less skilled people (Taylor and Lobel, Reference Taylor and Lobel1989; Wills, Reference Wills1981). Such downward comparisons tend to enhance one’s sense of superiority and generate positive affect (McFarland and Ross, Reference McFarland and Ross1982; Roese and Olson, Reference Roese and Olson2007; Wheeler and Miyake, Reference Wheeler and Miyake1992), as confirmed also by neuro-physiological evidence (Fliessbach et al., Reference Fliessbach, Weber, Trautner, Dohmen, Sunde and Elger2007).

Related to social comparison is a body of research that goes under the title of social facilitation. This theoretically enigmatic line of research captures the tendency of both humans (Triplett, Reference Triplett1898) and non-human animals (Reynaud et al., Reference Reynaud, Guedj, Hadj-Bouziane, Meunier and Monfardini2015) to alter their performance in the presence of conspecifics, i.e., other members of the same species (Belletier et al., Reference Belletier, Normand and Huguet2019; Markus (Reference Markus1978); Seitchik et al., Reference Seitchik, Brown, Harkins, Harkins, Williams and Burger2017). These effects have been found to both enhance and hinder performance (see Bond and Titus, Reference Bond and Titus1983; Geen and Gange, Reference Geen and Gange1977; Zajonc, Reference Zajonc1965; Zajonc and Sales, Reference Zajonc and Sales1966). We focus here on enhancement, which is the more relevant effect.

The research on social facilitation encompasses two types of social settings. Coaction refers to situations where two or more participants perform the same action in the presence of one another. For example, Triplett’s (Reference Triplett1898) seminal article reports that competitive cyclists recorded faster times when racing against other cyclists than when racing against the clock (Blascovich et al., Reference Blascovich, Mendes, Hunter and Salomon1999; Bond and Titus, Reference Bond and Titus1983; Zajonc, Reference Zajonc1965). Likewise, Berridge (Reference Berridge1935) demonstrated the superior performance of weight lifters when lifting in front of other weight lifters as compared to lifting in private. Another line of research shows that social facilitation can be spurred by the mere presence of observers (Blascovich et al., Reference Blascovich, Mendes, Hunter and Salomon1999; Bond and Titus, Reference Bond and Titus1983; Zajonc, Reference Zajonc1965). For example, weight lifters display higher performance when lifting in front of a passive audience as compared to lifting in private (Rhea et al., Reference Rhea, Landers, Alvar and Arent2003). Whether through coaction or through mere presence, social facilitation is understood to be mediated by people’s apprehension of being evaluated (Henchy and Glass, Reference Henchy and Glass1968), which is explainable in turn by the need for self-enhancement (Baumeister, Reference Baumeister1982). But for any such evaluation to occur, the actor needs at least to be observed by the second party. As stated by Berridge (Reference Berridge1935), social facilitation is predicated on the bystander observing ‘the sight and sound of others making the same movements or trying to do the same thing’ (p. 40). Indeed, studies fail to find social facilitation effects when the bystander is blindfolded or uninterested (Cottrell et al., Reference Cottrell, Wack, Sekerak and Rittle1968; Paulus and Murdoch, Reference Paulus and Murdoch1971).

The core objective of the current studies is to explore the lower boundary conditions of competitive behavior. We examine whether at least some forms of competitive behavior will be present even under circumstances that lack tangible incentives, do not afford social comparison, and do not even meet the minimal conditions for social facilitation. To explore this question, we set up a study that contains a crucial condition wherein participants coact with another unidentified coactor, absent incentives, while knowing that they will not even be informed of each other’s performance. This experimental setup, which we believe has not been examined in the experimental literature, will be labeled the masked coaction condition.

3. Sabotage

An emerging body of research in experimental economics reveals that competitors often adopt unseemly measures that go beyond outperforming their counterparts on the merits of the task (Chowdhury and Gürtler, Reference Chowdhury and Gürtler2015). Extant research on the dark side of competition (Charness et al., Reference Charness, Masclet and Villeval2014) includes cheating (Preston and Szymanski, Reference Preston and Szymanski2003), punishment (Abbink et al., Reference Abbink, Brandts, Herrmann and Orzen2010), risk taking (Genakos and Pagliero, Reference Genakos and Pagliero2012), and, most germane to this study, sabotage (Charness et al., Reference Charness, Masclet and Villeval2014; Harbring and Irlenbusch, Reference Harbring and Irlenbusch2008, Reference Harbring and Irlenbusch2011). Sabotage amounts to crippling an opponents’ performance, as opposed to boosting one’s own (Ambrose et al., Reference Ambrose, Seabright and Schminke2002; Amegashie, Reference Amegashie2012; Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Matthews and Schirm2010), whether by means of decreasing or destroying the opponent’s productive effort (Amegashie, Reference Amegashie2012; Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Matthews and Schirm2010; Harbring and Irlenbusch, Reference Harbring and Irlenbusch2011), raising their cost of production (Salop and Scheffman, Reference Salop and Scheffman1983), under-reporting their performance (Rigdon and D’Esterre, Reference Rigdon and D'Esterre2017), diminishing their score (Charness et al., Reference Charness, Masclet and Villeval2014), or forcing them to operate under adverse physical conditions (Poortvliet, Reference Poortvliet2013). Such unethical behavior is more likely to occur when individuals can exploit perceived unfairness of distribution as an excuse (Gino and Pierce, Reference Gino and Pierce2010). The introduction of sabotage has the effect of intensifying competitive behavior (del Corral et al., Reference del Corral, Prieto-Rodríguez and Simmons2010; Harbring and Irlenbusch, Reference Harbring and Irlenbusch2005, Reference Harbring and Irlenbusch2008) while also generating acrimony between the protagonists and thus darkening the competition (Kilduff et al., Reference Kilduff2014, Reference Kilduff, Galinsky, Gallo and Reade2016). Importantly, studies find that the presence of sabotage results in participants exerting lower levels of effort in the completion of their tasks (Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Matthews and Schirm2010; Charness et al., Reference Charness, Masclet and Villeval2014; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Lin and Zhang2019).

4. Study 1

4.1. Study Overview

In the primary study of this paper, participants were given a simple task that is incentivized and timed. We examined competitive behavior at four levels of competition intensity between pairs of participants who were randomly matched and kept anonymous from one another. All participants were informed of their own time of completion. Two of the conditions were set up as formal, structured competitions, by which a bonus was awarded to the participant who completed the task faster than their counterpart. In one of those conditions, the task difficulty of the respective participants was kept constant and known (the bonus condition). In the other, participants were not privy to the difficulty of their counterpart’s task (the uncertainty condition). The other conditions were set up as coaction. That is, participants were informed that there was another participant performing the same task, but each one would complete the task independently, with no tangible benefit to be gained. In one of these conditions, we announced at the outset that we would share both participants’ time of completion with each of them upon completion of the experiment (the unmasked coaction condition), but in the other, we mask the counterpart’s performance (the masked coaction condition), effectively barring the possibility of social comparison. Orthogonally, half of the participant pairs were given the option to sabotage their counterpart, by way of lengthening their recorded time of completion. Engaging in sabotage would be costly to the sabotaging participant. The other half was given no such option. Competitive behavior was measured, first, by the effort invested in the task and, second, by resorting to sabotaging the counterpart.

These forms of behavior map onto the distinction between attack and defense measures in the domain of intergroup conflict (De Dreu and Gross, Reference De Dreu and Gross2019). Sabotage amounts to an attack of the opponent (by way of lengthening their recorded time of completion), against which they can try to defend by boosting their effort (and thus shortening their recorded time). To avert preemptive sabotage (but nonetheless collect complete data), we employed the strategy method (Fischbacher et al., Reference Fischbacher, Gächter and Quercia2012), by which only one participant’s sabotage decision would be put into effect, as determined by a random draw after the completion of the task. This meant that a participant who engaged in sabotage could not be sabotaged in return.

Our study design enables us to replicate some extant findings and to tackle novel theoretical questions. At the general level, we expect that competitive behavior—both effort and sabotage—would vary more or less linearly in relation to competition intensity. The bonus and uncertainty conditions are designed to capture a classic competition, and the unmasked coaction condition is designed to capture a classic situation of social comparison. The masked coaction condition seeks to test a novel boundary condition. Based on the extant literature, this condition—which offers no tangible rewards and precludes the ability to compare one’s performance to the counterpart’s—should not give rise to competitive behavior at all. To the best of our knowledge, the extant literature has not examined the effect of sabotage in this setting. Any such effect, if observed, could not be explained by way of incentivized behavior, social comparison theory, or even social facilitation theory.

In all, our (preregisteredFootnote 1 ) hypotheses can be summed up as follows:

-

1. Competitive effort (measured by speed of task completion) will increase with the intensification of the competition.

-

2. When the option for sabotage is available, some participants will engage in sabotage, and its use will increase with the intensification of the competition.

-

3. Sabotage will be used even in the minimalist condition of masked coaction.

-

4. Both effort and sabotage will increase in conditions of heightened uncertainty.

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Sample size and participants

We conducted a power analysis to determine the sample size using software G*Power.Footnote 2 Focusing on the effects that are most challenging to establish, i.e., direct comparisons between 2 conditions, our goal was to obtain .8 power, in a 2-sided test, to detect a medium effect size of .5 at the standard .05 alpha error probability. For that, we would have needed 51 observations per condition. To provide a small buffer, we invited 60 participants for each of the 9 conditions. In actuality, 8 of the treatments had 59–62 participants, and one treatment had 72. For estimating the effect of the sabotage option, we can pool the data over all 4 conditions providing power to detect an effect of size .25.

Participants were randomly drawn from the 6,000 participants registered in the joint subject pool of the Bonn Max Planck Institute and the Econ Lab of Bonn University. Our sample was 376 female, 178 participants were male, and 6 indicated their gender as diverse. Participants were on average 26.36 years old, of whom 89% were students, majoring in a variety of fields. We conducted 24 sessions, which were run between late June and August 2022. As COVID-19 restrictions were in place, we implemented the experiment online. Participants were each assigned to a single treatment and were blinded to all other treatments.

4.2.2. Study design and materials

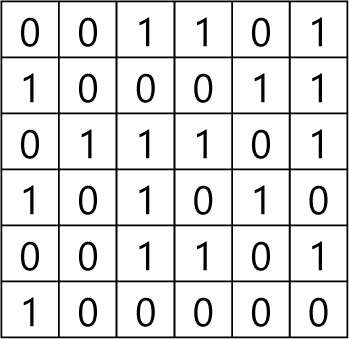

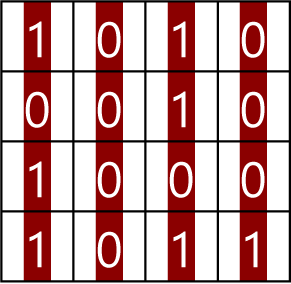

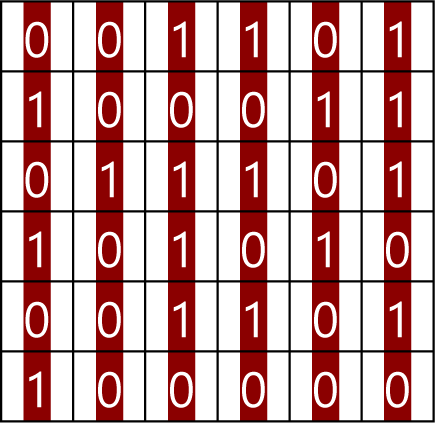

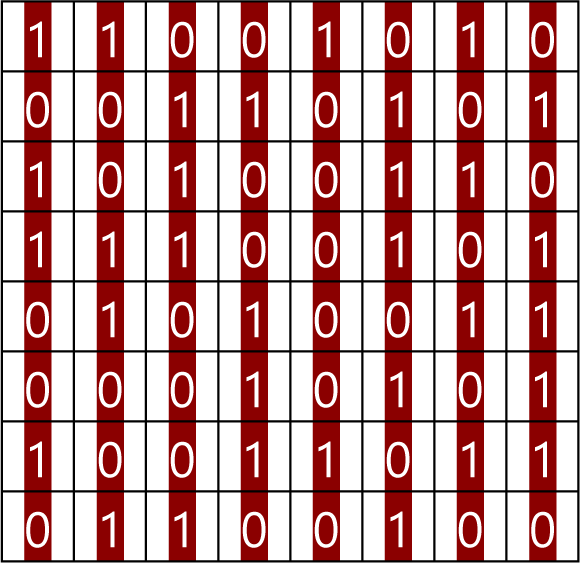

We ran an online lab experiment that was administered on an oTree platform (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Schonger and Wickens2016) and complied with prevailing ethical regulations.Footnote 3 Participants were presented with the tedious real effort task of counting 1’s and 0’s in 10 tables containing 6x6 cells each, as depicted in Figure 1. This task, which has been used successfully in prior research (Carpenter and Huet-Vaughn, Reference Carpenter, Huet-Vaughn, Schram and Aljaz2019), offers a particularly clean design as performance does not depend on ability or learning (Abeler et al., Reference Abeler, Falk, Goette and Huffman2011). Tables that were counted incorrectly were replaced with new tables, up to a maximum of 15 tables. For completing 10 tables correctly, participants would earn 1 ECU per table. Participants were informed that a failure to count 10 tables correctly would negate their earnings but, in actuality, all participants completed the task. Hence, formally, participants received a piece rate, but effectively they all earned the same amount of 10 ECU.Footnote 4 As the rate of 1 ECU was equivalent to .5€, the main task yielded a compensation of 5€. We used participants’ time taken to complete the task as the measure of their effort.

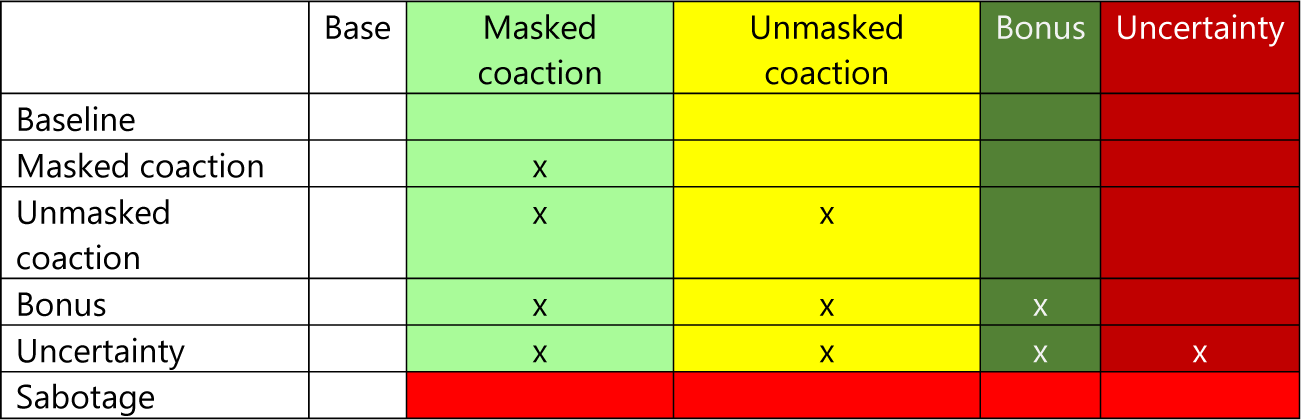

Competitive intensity was manipulated across the following conditions.

-

1. Baseline condition: participants perform the task alone, and are not matched with other participants.

-

2. Masked coaction condition: participants are informed that they are matched with another participant who would perform the same task. They are also told that there would be no consequences to their relative performance, and that they would not be informed about the other’s performance. Effectively, this treatment lacks incentivized competition, and it precludes both social comparison and social facilitation.

-

3. Unmasked coaction condition: this condition is similar to masked coaction, except that participants are told that they would be informed of their counterpart’s performance at the end of the experiment. This condition lacks monetary incentives but makes social comparison possible.

-

4. Bonus condition: this condition is similar to the unmasked coaction, except for the addition of a monetary bonus of 5 ECU that would be awarded to the participant who completed the task faster than their counterpart.

Figure 1 Real effort task.

-

5. Uncertainty condition: this condition is similar to the bonus condition with an added dimension of uncertainty. Participants are told that their (and their counterparts’) tables could come in one of 3 sizes: 4x4, 6x6, or 8x8. Each table size would be equally likely and would be randomly drawn independently for each participant. Participants would be privy to the size of their own tables, but not to the size of their counterpart’s tables. Given that bigger tables take longer to count, this condition introduced uncertainty with respect to the expected relative performance, and it also made it possible for a participant to consider herself being treated unfairly, with the counterpart enjoying the benefit of an easier task.

Within each of the conditions (with the exception of baseline), half of the pairs were introduced to the option of sabotaging their matched counterpart. The other half were given no such option. Exercising sabotage came at a cost to the saboteurs. Participants were to receive a second endowment of 2 ECU, which was for them to keep, but which could be used to fund acts of sabotage. Any integer percent of this endowment spent on sabotage would lengthen the recorded time of their counterpart by the same percentage. Thus, by spending 10% of the endowment, one could lengthen their counterpart’s time by 10% (say, from 130 seconds to 143 seconds). Following Fischbacher et al. (Reference Fischbacher, Gächter and Quercia2012), we employed the strategy method by which only one participant’s sabotage decision would be implemented, as determined by a random draw after the completion of the task. Sabotage decisions were to be made upfront, before performing the task.

After the completion of the task, participants in all but the baseline and the masked coaction condition were incentivized to estimate the time it took their counterpart to complete the task, and they were also informed how they performed relative to their counterpart. Using the standard test from Holt and Laury (Reference Holt and Laury2002), we elicited risk preferences from all participants. We also asked all participants a series of unincentivized questions probing their attitudes toward the game and toward competition more generally. We also recorded demographic information.Footnote 5

4.3. Results

4.3.1. Earnings

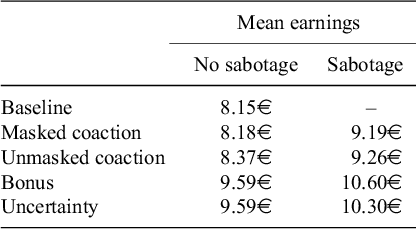

Table 1 summarizes the mean earnings. As we run down the columns, we see that earnings increase as the competition intensifies, which is best understood as increased effort. The introduction of a bonus increases the joint earnings by 5 ECU (2.5€), and the presence of the sabotage option adds the unused fraction of the 2 ECU (1€) endowment.Footnote 6

Table 1 Participants’ earnings across conditions

4.3.2. Sabotage

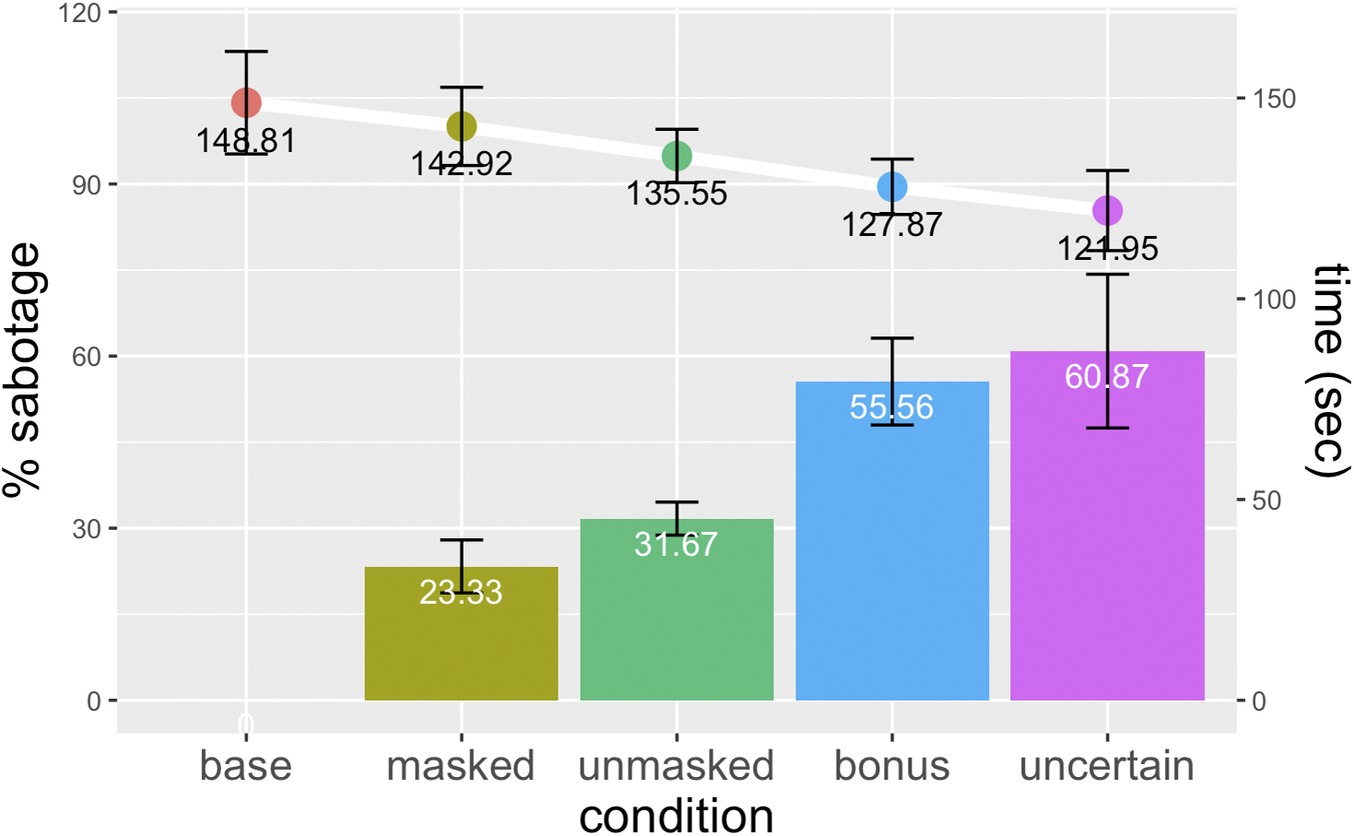

Figure 2 provides the study’s main findings. We begin with the rates of the sabotage use, which are represented by the bars. We see that when the sabotage option is made available, it is used by 23.33% of participants in the masked coaction condition, 31.67% in the unmasked coaction condition, 55.56% in the bonus condition, and 60.87% in the uncertainty condition (looking only at participants who were given tables of size 6x6 to solve). On average, the percentages of the endowment spent by participants on sabotage were 7.3% (31.3% among those who chose to sabotage at all) in the masked coaction condition, 5.72% (18.1%) in the unmasked coaction condition, 23.1% (41.6%) in the bonus condition, and 22.6% (37.1%) in the uncertainty condition (again, for participants who were given tables of size 6x6 to solve). In the bonus condition, 57.5% of participants who engaged in sabotage earned the bonus, whereas only 40.63% of those who chose not to sabotage earned it. Given that the bonus was larger (5 ECU) than the maximal cost of engaging in sabotage (2 ECU), in expectation (and ignoring individual estimates about competitive performance), sabotage was a profitable decision.

Figure 2 Sabotage and effort. Bars and left axis: % of participants engaging in sabotage. Dots and right axis: Number of seconds participants take on average to complete the task. To maintain consistency across treatments, the results for the uncertainty condition are limited to participants who were given size 6×6 tables.

Table 2 provides statistical tests. Model 1 considers the extensive margin: how likely is it, dependent on condition, that participants spend any fraction of the extra endowment to sabotage their counterpart? The regression predicts that 23.33 of participants in the masked coaction condition engage in sabotage, which is significantly different from zero (p < .001). The incidence of sabotage is not significantly higher in the unmasked coaction condition. Subsequent Wald tests show that going from unmasked coaction to bonus significantly increases the incidence of sabotage (p = .004)Footnote 7 , while there is no significant difference between the bonus and uncertainty conditions (p = .639). Taken together, the evidence points to two independent effects on the rate of sabotage: the presence of a co-actor (amounting to almost 25%) and the additional effect of the monetary incentive (amounting to more than 30%Footnote 8 ).

Table 2 Sabotage and effort by condition

Model 1: linear probability model, dv: dummy that is one if sabotage > 0. Model 2: OLS, interpreting the fraction (percentage) of the endowment used for sabotage as a continuous variable. Models 3–5: OLS, dv: seconds to complete task. Models 1–3: only data from treatments with sabotage option. Reference category: masked coaction with sabotage. Model 4–5: data from treatments without and with sabotage option. Model 4: Reference category: Baseline. Model 5: data from treatments with belief elicitation (i.e., without Baseline and Masked Coaction). Reference category unmasked coaction without sabotage. Uncertainty condition: data provided the active participant had been assigned tables of size 6x6. Reference category: Models 1–4: masked coaction, Model 5: unmasked coaction. Standard errors in parenthesis. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05, + p < .1.

We see a similar picture if, in Model 2 instead we consider the intensive margin, i.e., the percentage of their additional endowment that participants expend on sabotage. We again find a significant effect even in the minimalist masked coaction condition. On average, participants spent 7.3% for this purpose, which is significantly different from 0Footnote 9 . Once more, there is no significant difference between the masked coaction and unmasked coaction conditionsFootnote 10 . Wald tests find a significant difference between unmasked coaction and bonus (p < .001) but no significant difference between bonus and uncertainty (p = .930). The regression predicts that participants in conditions that awarded a bonus spent on average 15% more of the endowment on sabotage.

4.3.3. Effort

As the dots in Figure 2 show, the time taken to complete the task decreases linearly as the intensity of the competition increases. When operating in the condition of masked coaction, participants take an average of 142.92 seconds to complete the task. That time drops to 135.55 seconds in the unmasked coaction condition. When competing for the monetary bonus, they work even quicker, taking 127.87 seconds for completion. Performance is fastest (121.95 seconds) when competing for the bonus under conditions of uncertainty. We find a significant difference between performance in the two unincentivized coaction conditions on the one hand and the two incentivized conditions (bonus and uncertainty) on the other hand (Model 3 of Table 2). No differences were found between the two unincentivized conditions (masked coaction and unmasked coaction)Footnote 11 and, as a subsequent Wald test shows, also not between the two incentivized conditions (bonus and uncertainty) (p = .429).

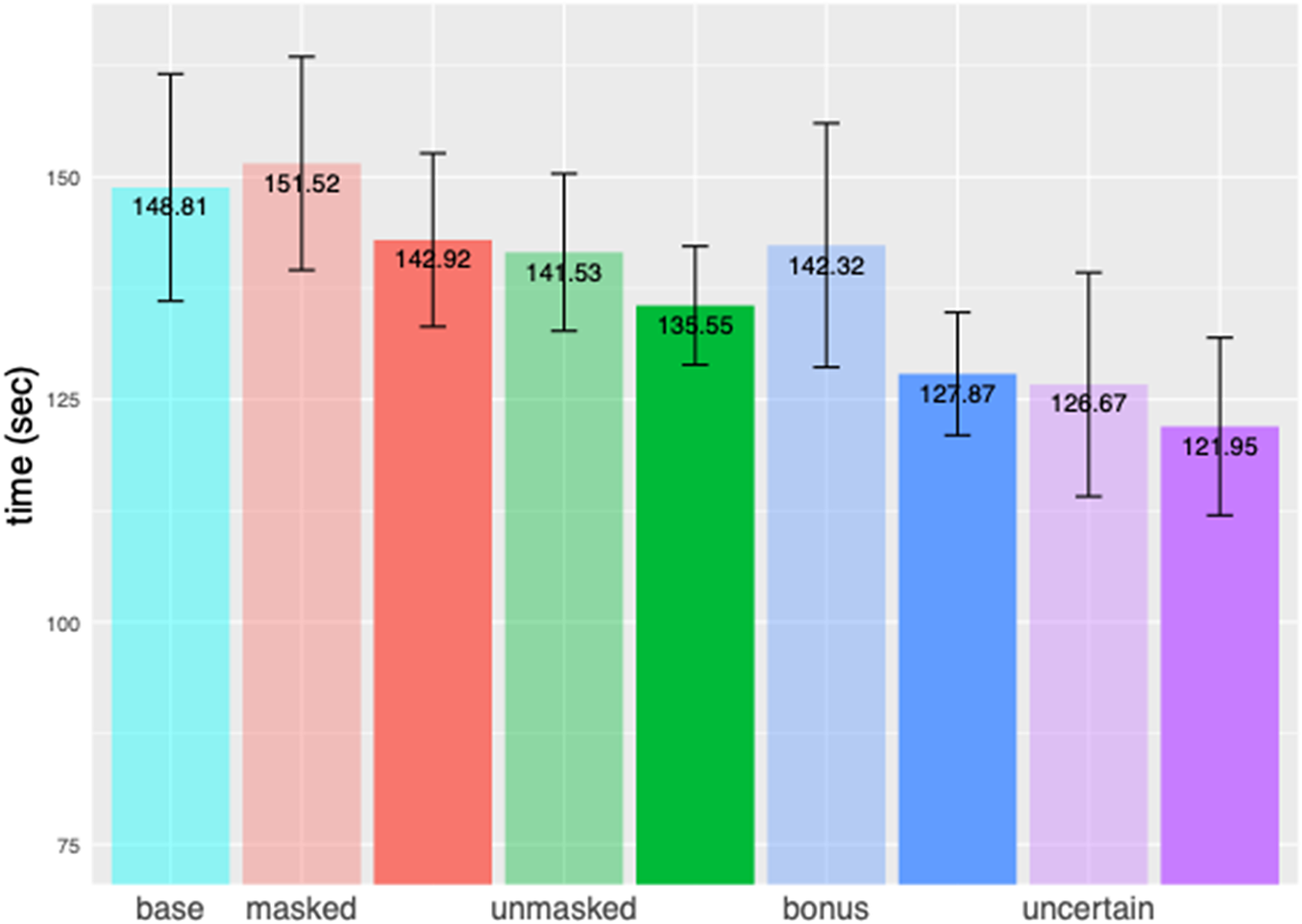

We wonder what explains the effect of treatment on effort: whether it is due to the heightened competitive motivation or to the risk of sabotage? To discriminate between these explanations, within each condition, we compared participants who were given the option to engage in sabotage with those we were not (excluding the baseline participants). As Figure 3 shows, in the absence of the sabotage option, effort is largelyFootnote 12 ordered the same way as with the sabotage option. Participants take most time—understood as exerting least effort—when they are kept in the dark about their counterpart’s performance (masked coaction—151.52 seconds). They work quicker in the unmasked coaction (141.53 seconds), and quicker when incentivized by a financial reward for winning (bonus—142.32 seconds), and even quicker under conditions of uncertainty about the competitive strength of their counterpart (uncertainty—126.67 seconds). The difference in effort when sabotage is unavailable is small.

Figure 3 Impact of sabotage option on effort. Time (in seconds) that participants take on average to complete the task. Conditions are color coded. Light colors: no sabotage option; dark colors: sabotage option. To maintain consistency among conditions, the results for uncertainty condition are limited to cases where the tables were size 6×6.

Descriptively, the presence of the sabotage option results in shorter times taken to complete the task. Model 4 of Table 2 shows that the sabotage option has a small but significant effect on effort. In this specification, we also find a weakly significant (p = .081) difference between the masked coaction and unmasked coaction conditions.Footnote 13 We thus find 2 independent effects: effort increases as the situation becomes more competitive, and it increases also with the possibility of sabotage. Actually, both effects have approximately the same size: the estimated effect of going from masked coaction to unmasked coaction is −8.684 seconds, and the estimated effect of facing the risk of sabotage is −9.347 seconds. We can clearly reject the concern that the prospect of sabotage deters effort. The risk that a competitor will engage in foul play does not stifle competitive behavior, it invigorates it.

This interpretation receives further support from Model 5 of Table 2. After the main experiment, we asked participants to estimate the time that their counterpart would take to complete the task.Footnote 14 This gives us a direct measure of perceived competitive strength. We observe that the longer participants expected their counterparts to take for completing the task, the longer they took to complete it themselves. If we control for this belief, treatment effects become either insignificant, or small and only weakly significant. By contrast, the effect of the sabotage option on effort remains unaffected and is even more highly significant. This shows that participants indeed interpret the risk of being sabotaged as a threat, to which they react with extra effort.Footnote 15

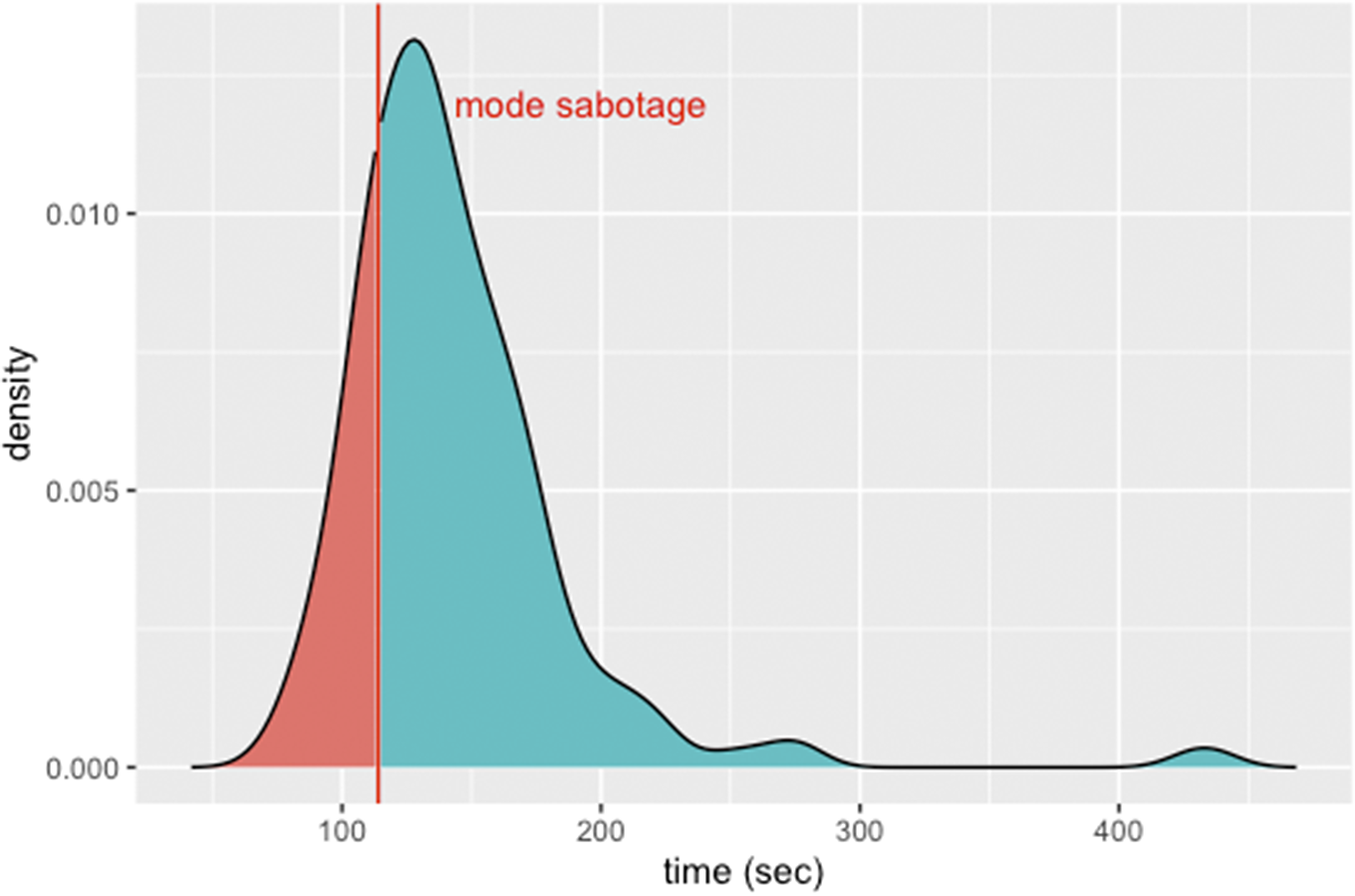

As seen in Models 4 and 5 of Table 2, the effect of the sabotage option on the task completion time is estimated at around 10 seconds. This may appear a fairly small effect given that the constant of the regression is estimated to be between 140 (Model 5) and 150 (Model 4) seconds. Thus, it would seem that participants who fear sabotage could avoid its impact by reducing their time by a mere 6 or 7%. Yet Figure 4 shows that doing so is no easy feat. The graph shows that the distribution of completion time is heavily right skewed: a small number of participants take a long time to complete the task, while on the lower end of the distribution there is very little variance. It follows that the majority of participants would find it difficult to speed up their performance.

Figure 4 Effect size. Density of time required for completing the task in the absence of sabotage. Red area: observations in which the time was below or equal when facing the risk of sabotage.

The graph shows the distribution of completion time in the absence of sabotage, for all conditions combined (except baseline). The area under the curve in red defines the fraction of participants in this condition who need as little, or even less, time than the modal participant took in the face of the sabotage option. We can see that this mode is considerably further to the left. Hence, the sabotage option pushes effort into a level of performance that only few participants meet in the absence of sabotage. Specifically, in the absence of sabotage, only 21.11% of the participants are that fast, while this holds true for 30.70% when sabotage is available.

5. Study 2

5.1. Replication of the Masked coaction condition (with sabotage)

The most intriguing finding of Study 1 was that almost a quarter of the participants in the masked coaction condition engaged in sabotage when given the option to do so. Recall that in this condition, participants had no prospect for winning a bonus and, given that the counterpart’s performance would not be revealed, there was no prospect for social comparison. To dispel the suspicion that Study 1’s finding of sabotage might have been aberrational, we conducted a follow-up study, which was intended as a replication of masked coaction with the sabotage option. As a further safeguard, we sought to dispel the suspicion that the sabotage behavior was driven by a miscomprehension of the study’s instructions. Thus, the follow-up study included a quiz, which had to be answered correctly as a condition for participation. The quiz also served to (implicitly) remind participants that (a) sabotage was costly and (b) that they would never learn of their counterpart’s performance. We aimed for 60 participants (30 pairs), though due to no-shows and dropouts, we ended up with 56 participants (28 pairs). We preregistered the replication on the same platform as the original experiment, with the same hypotheses.Footnote 16

5.2. Results

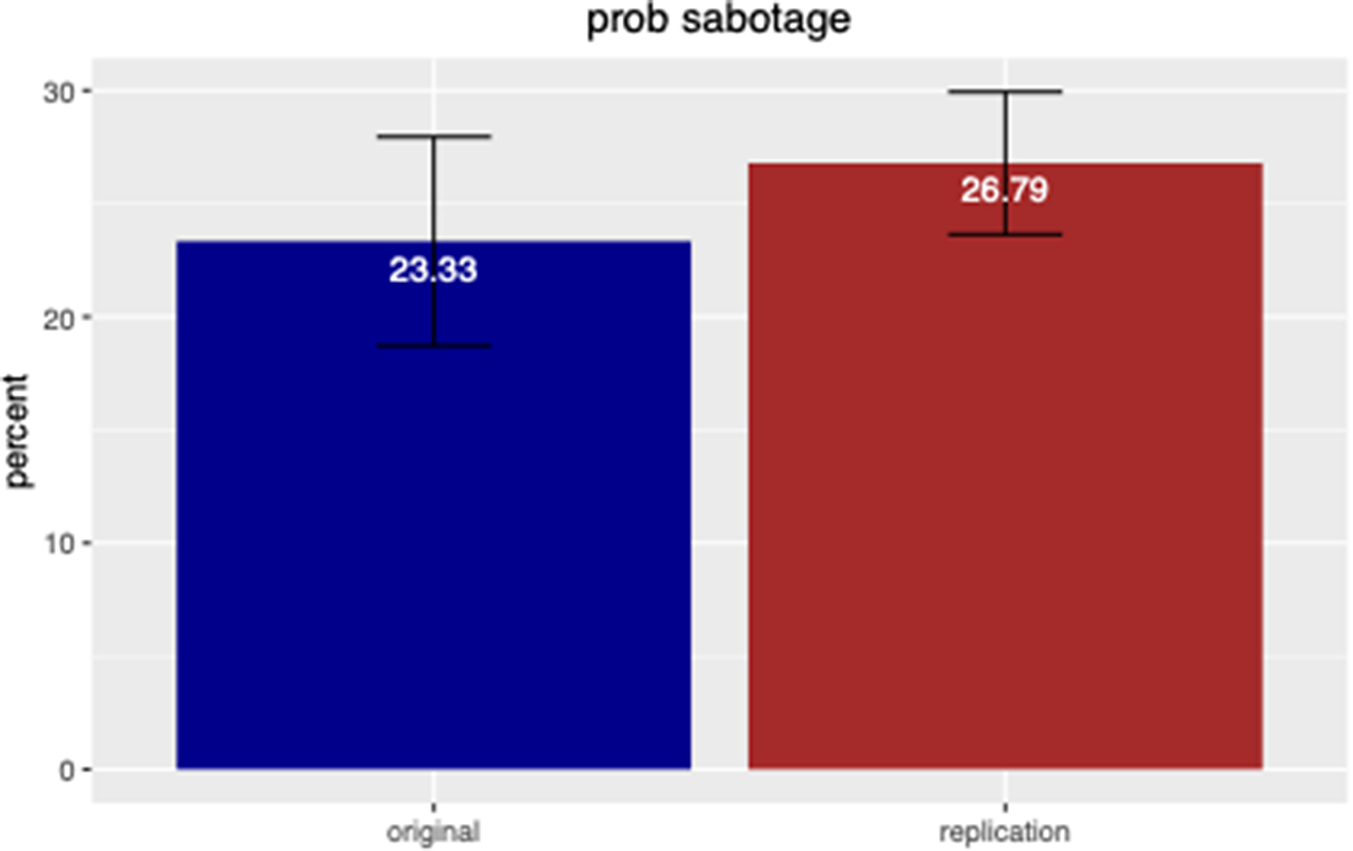

As Figure 5 shows, the findings of Study 1 were not the product of chance. The frequency of sabotage in the masked coaction condition was slightly higher than in Study 1 (26.79% v. 23.33%). The percentage of the endowment spent by participants on sabotage was 5.36%, which was slightly lower than in Study 1 (7.3%). Statistically, both the frequency and the amount of money invested in sabotage are indistinguishable between the two studies.Footnote 17

Figure 5 Probability of sabotage in masked coaction condition in both studies.

6. Discussion

The first 3 hypotheses were confirmed in that competitive behavior was found to be highly sensitive to the intensity of the competition. We see that as the competition intensified, our participants extended greater effort, as measured by their speed of task completion. The responsiveness of effort to competition intensity replicates prior research both in economics (Bull et al., Reference Bull, Schotter and Weigelt1987; Orrison et al., Reference Orrison, Schotter and Weigelt2004; Schotter and Weigelt, Reference Schotter and Weigelt1992) and psychology (e.g., Harackiewicz et al., Reference Harackiewicz, Abrahams and Wageman1987; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Lin and Zhang2019; see also Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Tor and Schiff2013). Consistent with tenets of rational self-serving behavior (e.g., Nalbantian and Schotter, Reference Nalbantian and Schotter1997), we observe heightened effort in the two conditions that awarded a monetary incentive (the bonus and uncertainty conditions). Heightened effort was likewise observed in the condition that afforded status gains (the unmasked coaction condition), as would be predicted by social comparison theory in psychology (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Tor and Schiff2013; Haran, Reference Haran2019) and by ranking competitions in economics (Azmat and Iriberri, Reference Azmat and Iriberri2010; Charness et al., Reference Charness, Masclet and Villeval2014; Kosfeld and Neckermann, Reference Kosfeld and Neckermann2011; Rustichini, Reference Rustichini2008). We see clear evidence of participants availing themselves of the option to sabotage their counterpart. Participants engaged in sabotage more often and spent more of their endowment on it as the competition became more intense. Both the rate and magnitude of sabotage were highest in the presence of a monetary incentive (the bonus and uncertainty conditions), which is consistent with the tenets of rational choice (see Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Matthews and Schirm2010; Harbring and Irlenbusch, Reference Harbring and Irlenbusch2008, Reference Harbring and Irlenbusch2011). Still, we note that even with money on the line, a sizable minority of participants did not engage in sabotage (44.44% in the bonus condition and 39.13% in the uncertainty condition). This is probably due to the inhibitory effect of moral norms. Sabotage was appreciable also in the context of social comparison, as seen in the unmasked coaction condition. This finding is notable because this condition offered participants no compensation, thus making costly punishment a negative monetary proposition. The likely explanation is that the cost of sabotage was outweighed by the psychic benefits that participants expected from the favorable social comparisons.

Introducing uncertainty to the monetary competition increased both effort and the use of sabotage. These behaviors are likely explained by a heightened vigilance triggered by the prospect that the counterpart was assigned an easy task.

Based on extant research (Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Matthews and Schirm2010; Charness et al., Reference Charness, Masclet and Villeval2014; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Lin and Zhang2019), one would expect that the prospect of sabotage would result in less effort being exerted on the task. Recall, however, that we found the opposite effect: when the option of sabotage was available, participants worked faster, which we interpret as investing greater effort. A likely explanation for this discrepancy has to do with the experimental design. In those previous studies, participants were presented with the sabotage option well into the multi-phase process and only after receiving feedback about their relative performance. In our study, the decision to engage in sabotage was made before the commencement of the task and thus absent any feedback. With no knowledge of their relative performance, our participants were probably less likely to experience the euphoria of leading over their counterpart or the despondency of trailing them, either of which could be expected to result in reduced effort. Alternatively, participants might have interpreted the possibility of sabotage as information about the intensity of competition: not only do they have to live up to heterogeneity in ability, and hence competitive strength, but they must also prepare for the risk of foul play by their counterpart. Given the absence of institutional protection against sabotage, the only feasible way to win would be to work even harder at the task.

A focal objective of our studies was to test competitive behavior in the novel condition of masked coaction, which afforded no prospect for either monetary or status gains. In the basic treatment, i.e., absent a sabotage option, we found no evidence of competitive behavior, that is, exertion of greater effort. In this regard, our findings are consistent with Haran and Ritov’s (Reference Haran and Ritov2014) observation that competitive behavior tends to be muted when the counterpart has not been singled out (‘unspecified’), as opposed to being identifiable (even if merely by means of a randomly generated ID number). But our participants’ behavior changed markedly once the option for sabotage was added into the mix. This was manifested by both an exertion of greater effort (on average) and by engagement in sabotage by a sizable minority. In other words, the sabotage option resulted in both enhanced productivity and dark behavior. We show that people avail themselves of sabotage even absent material incentives, with no prospect of being compared, and when social facilitation is infeasible. The mere abstract knowledge that another person is engaging in the same task was apparently enough to lead a sizable fraction of participants to engage in sabotage.

6.1. Why sabotage?

As mentioned, engaging in sabotage in the presence of a monetary incentive can be readily explained as rational behavior in that earning the bonus outweighed the cost of the sabotage. It is not difficult to explain resorting to sabotage also in the unmasked coaction condition, where the cost could be justified by the psychic benefits that follow from favorable social comparisons. However, it is harder to explain why 23% and 26% of participants in the masked coaction conditions would incur the cost of sabotaging with neither monetary nor social benefits to be gained. What might explain this enigmatic behavior?

Unfortunately, our data do not provide a definitive explanation. The best we can do is offer possible lines of inquiry. For one, sabotage might have stemmed from a strategic reaction to the prospect of being sabotaged by the counterpart. In other words, these participants sought to preempt being harmed by their counterpart’s defection, an eventuality that was substantiated by the considerable rate of actual sabotage. True, our design adopted the strategy method (Fischbacher et al., Reference Fischbacher, Gächter and Quercia2012), by which for each pair of participants, only one participant’s sabotage decision would be implemented. This meant that a participant whose sabotage was put into effect could not be sabotaged in return, and it would follow that neither of the (assumedly rational) participants would engage in sabotage to fend off the risk of being sabotaged. But it is still possible that our participants did not fully internalize the implications of the strategy method or that their rational inclinations were overwhelmed by retaliatory impulses. Indeed, studies show that retaliatory behavior is largely reflexive rather than being a product of deliberative thinking and rational calculation (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Buckley and Carnagey2008; Vandermeer et al., Reference Vandermeer, Hosey, Epley and Keysar2019).

It is also possible that the observed sabotage was not so much an expression of competitive behavior as a manifestation of appetitive aggression, that is, a personal preference for committing aggressive acts. Such a preference is observed, for example, in behaviors such as sport hunting, playing violent video games, and viewing violent sports such as UFC, boxing, and hunting. Elbert and colleagues have proposed that human aggression is activated through a biologically prepared reward circuitry, which reinforces a lust for attacking and fighting (Elbert et al., Reference Elbert, Moran, Schauer and Bushman2017, Reference Elbert, Schauer and Moran2018; West and Chester, Reference West and Chester2022). According to this view, aggressive acts serve to boost the aggressor’s mood and sense of pleasure (Chester et al., Reference Chester, DeWall, Derefinko, Estus, Lynam and Peters2016; Reference Chester, Clark and DeWall2021; De Quervain et al., Reference De Quervain, Fischbacher, Treyer, Schellhammer, Schnyder and Buck2004), and they could well explain engaging in sabotage absent any apparent rationale.

Our findings of sabotage—particularly when viewed as an expression of aggression—run against the grain of the well-established observation that people are basically kind and generous to one another. Studies show that people exposed to another person receiving electrical shocks are willing to suffer the shocks in their place (Batson et al., Reference Batson, Duncan, Ackerman, Buckley and Birch1981), people go out of their way to help a stranger in trouble (Darley and Batson, Reference Darley and Batson1973), people engage in costly third-party punishment when witnessing others being treated unfairly (Boyd et al., Reference Boyd, Gintis, Bowles and Richerson2003; Fehr and Gächter, Reference Fehr and Gächter2002), and many people share some of the money given to them in dictator games with no expectation of recovering it (Engel, Reference Engel2011). At the same time, however, studies also show that people engage in various forms of anti-social behavior such as nastiness (Abbink and Sadrieh, Reference Abbink and Sadrieh2009; Zizzo and Oswald, Reference Zizzo and Oswald2001), taking of property from others (Bar-Gill and Engel, 2025), cheating (Preston and Szymanski, Reference Preston and Szymanski2003), anti-social punishment (Abbink et al., Reference Abbink, Brandts, Herrmann and Orzen2010), and sabotage (Amegashie, Reference Amegashie2012; Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Matthews and Schirm2010; Charness et al., Reference Charness, Masclet and Villeval2014; Harbring and Irlenbusch, Reference Harbring and Irlenbusch2011). It follows that it cannot be said that people are monolithically generous or invariably hostile. Rather, people seem to have the capacity to be both, with the emergent behavior being influenced by the features of the situation. We propose that one such feature is the manner in which participants are primed by the presentation of the task. Recall the famous study of Liberman et al. (Reference Liberman, Samuels and Ross2004), where framing a prisoner dilemma’s game as the ‘Wall Street Game’ resulted in high rates of defection and framing it as the ‘Community Game’ resulted in higher levels of cooperation. Such a priming effect might well have played a role also in our study, in that introducing the idea of sabotage could have evoked an ethos of competitiveness. The notion that sabotage had such a priming effect is compatible with the weapon priming effect, by which the mere presence of a weapon tends to induce aggression-related cognitions and to enhance aggressive behavior (Benjamin and Bushman, Reference Benjamin and Bushman2016; Berkowitz and LePage, Reference Berkowitz and LePage1967). Moreover, making sabotage a permissible component of the rules of the game could have been interpreted as a normative approval of this course of action. That sense of legitimacy, in turn, could have weakened inhibitions that participants might have otherwise felt toward the infliction of harm on their unwitting opponents.

Perhaps the most likely explanation can be extrapolated from a particular genre of social comparisons. Think, for example, of the negative feeling that creeps in upon hearing that your high school nemesis just landed a high-flying job, when your child is outperformed at the second-grade flute recital, and when someone in your neighborhood just purchased a car that is faster or flashier than yours. Indeed, studies find that people engage in comparisons spontaneously, under conditions that render them quite irrational (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Giesler and Morris1995). A study titled ‘The man who wasn’t there’ found that people responded affectively to comparisons with targets who were primed subliminally and who served no plausible reference for comparison (Mussweiler et al., Reference Mussweiler, Ruter and Epstude2004). Comparisons with superior but irrelevant targets have been found to result in negative feelings, whereas comparisons with irrelevant inferior targets induce positive feelings (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Giesler and Morris1995; see Mussweiler et al., Reference Mussweiler, Corcoran, Crusius and Chadee2011). Research shows that people suffering from adverse medical conditions compare themselves to patients who are afflicted by even worse conditions (Buunk et al., Reference Buunk, Gibbons and Buunk2013; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Wood and Lichtman1983; Tennen, Reference Tennen, Suls and Wheeler2000). Findings of the better-than-average effect show that people habitually compare themselves favorably to vast and anonymous cohorts (Alicke and Govorun, Reference Alicke, Govorun, Alicke, Dunning and Krueger2013). The targets in all of these comparisons are typically unaware that they are serving as comparative reference points and thus do not perceive themselves as engaging in any sort of comparison (Garcia and Tor, Reference Garcia, Tor, Garcia, Tor and Elliot2024; Graf-Vlachy et al., Reference Graf-Vlachy, König and Hungenberg2012). The fact that these comparisons occur unilaterally and entirely inside one’s head makes the comparative exercise utterly illusory, with the resulting sense of self-enhancement best understood as illusory superiority (Hoorens, Reference Hoorens1993).

Our findings of sabotage in the masked coaction condition can be viewed as an extension of illusory comparisons to the domain of competition: under certain situations, some people will conjure a competition where there is none, and will behave competitively against an illusory competitor. Such behaviors could include both exerting more effort and engaging in antisocial practices to undermine the unwitting counterpart. As with other forms of illusory superiority, the likely explanation for such behavior is the need for self-enhancement (see Hoorens, Reference Hoorens1993). Working harder and undermining the counterpart are ways to inflate one’s sense of self, a need whose fulfillment is independent of monetary gains and is hedonically valuable even in the absence of an identifiable counterpart.

6.2. Normative aspects

From a welfare perspective, sabotage is generally deemed as a problematic proposition. For one, engaging in sabotage is often costly, as it is habitually operationalized in experimental studies, including our own. That cost amounts to sheer waste. Recall that prior studies found that sabotage results also in decreased productivity, thus compounding the waste. In contrast, we found that sabotage resulted in appreciable increases in effort. At first blush, this welfare enhancement might lead one to be more willing to accept incorporating sabotage as a means for boosting productivity. Yet, there are good reasons to resist celebrating this finding. For one, before we promote widespread sabotage, we would need first to identify the boundary conditions for the productivity boost, especially since other studies found drops in productivity. Data will also be needed to find the optimal conditions for ensuring that the productivity gains outweigh the costs of sabotage. The reason for caution run even deeper, as the normalization, let alone encouragement, of sabotage presents a series of challenges. By enabling sabotage, we are opening the door to distorting the competition, such that the meritless party can be declared the winner by virtue of thwarting the purpose of the competition. That prospect can readily lead contestants to rely more on sabotage and less on productivity, thus generating a welfare loss. Fearing sabotage, contestants could turn to sabotage to preempt sabotage by their counterpart, thus triggering a wasteful destruction war. Over time, this process can make contestants increasingly cynical about the value of competition and the wisdom of investing effort, perhaps even discouraging them from participating in the competition altogether.

6.3. Limitations

This project is not free of concerns over external validity. Recall that we ran both studies using a sample that comprised largely of students recruited from the joint subject pool of the Bonn Max Planck Institute and the Economics Lab of Bonn University. While the students reported majoring in a variety of fields, it is possible that a disproportionate number of them had been exposed to the concepts of homo economicus and game theory. It should also be noted that due to its novelty, this study was set up in a bare-bones configuration. That means that our findings do not capture the variety of situational factors that could moderate the tendency to engage in sabotage, such as social and reputational considerations, features that prime participants toward competition or cooperation (see Liberman et al., Reference Liberman, Samuels and Ross2004), and more. It is our hope that these limitations will be addressed by way of replicating the paradigm with diverse samples and across a variety of experimental settings.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Appendix

[For the reader’s convenience, we have color coded the instructions to correspond to the different treatment conditions]

Instructions

Welcome to this experiment. In the experiment, you can earn a substantial amount of money. It is therefore important that you take the time you need for understanding the instructions of each part of the experiment.

The experiment has 7 parts. We will inform you about each part before it begins.

Part 1

In this experiment, you are randomly matched with another participant. Both of you will be presented with tables containing 0s and 1s. Your task will be to count the number of 1s in each table. You will earn 1 ECU for each table that you count correctly. For each table you count incorrectly, the computer will give you a new table, up to a max of 15 tables. If, after having received all 15 tables, you have not counted 10 tables correctly, you will not be compensated for the tables. All of this also holds for your counterpart.

Tables look like this.

The tables come in 3 different sizes: 4x4, 6x6 or 8x8.

Each size is equally likely to appear in the study. Each one of you will receive just one size of tables. The table size will be determined randomly, and separately for you and for your counterpart. Hence the two of you may receive tables of a different size.

The tables will appear after all other parts of the experiment, but before you receive feedback on this and all other parts of the experiment.

If you complete your 10 tables faster than your counterpart (irrespective of the size of the tables), you will receive a bonus of 5 ECU (in addition to the money you earn from counting the tables). If your counterpart will complete the task faster, the bonus will go to her. Time will be recorded in milliseconds. In the unlikely event of a tie, the two of you will split the bonus.

We will record the time that it took you and your counterpart to complete the 10 tables.

Note that you will, however, only be informed about the time that was recorded for yourself, not about the time recorded for the other participant.

At the end of the experiment, we will inform you both of time that was recorded for each one of you.

You will now receive two practice tables for each of the 3 possible sizes, to familiarize yourself with the task. Once you have completed the practice tables, you will be informed how long it took you to complete them. For solving these practice tables, you will not earn extra money, and there will be no consequences for completing them incorrectly. All of this also holds for your counterpart.

We are summarizing the central features of the design:

You will earn 1 ECU for each table in which you correctly report the frequency of the number 1.

Together with another participant, you are forming a group. You will, however, not receive any feedback about the other participant.

Together with another participant, you are forming a group. We will inform you both which one of you counted 10 tables correctly faster than the other.

Together with another participant, you are forming a group. Whoever counts 10 tables correctly faster will receive a bonus of 5 ECU.

Together with another participant, you are forming a group. Each of you will receive tables of size 4x4, 6x6 or 8x8. The size will be randomly determined. Each size is equally likely. The size you have has no impact on the size of tables for the other participant. Whoever counts 10 tables correctly faster will receive a bonus of 5 ECU

Each one of you receives an additional endowment of 2 ECU. The endowment may be used to prolong the time that is recorded for the other participant by at most 100%.

Part 2

In this part of the experiment, we are asking you for your estimate. We remind you it took you *** seconds to count the number of 1s in the two test tables.

You are now being asked to predict how many seconds it will take your counterpart to correctly count the number of 1s in 10 tables. We ask this question separately for each size of tables. If your estimate for the size of table that will actually be assigned to your counterpart is within +/- 20 seconds, you will earn an additional ***.

Part 3

Both you and your counterpart have the option to submit a request to extend the time recorded for the other player’s completion of the tables. To help you fund such a request, you will be given an additional endowment of 2 ECU. You may choose to invest any fraction of your endowment toward this option, up to a max of 100%. For any fraction of the endowment you invest, we will extend the time recorded for your counterpart’s completion of the tables by the same percentage. For example, if you invest 10% of your endowment and it took your counterpart 500 seconds to complete her tables, her recorded time will be extended by 50 seconds (500 + 50 = 550 seconds). If you choose to invest your entire endowment, her recorded time will increase by 500 seconds (500 + 500 = 1000 seconds). Any fraction of the endowment that you decide not to invest is for you to keep.

You will be asked to submit 3 requests, one for each of the table sizes. But note that the only request that will count is the one that corresponds to the table size that will be assigned to you, regardless of the table size assigned to your counterpart. Note also that the table size assigned to your counterpart will not be known to you until the very end of the entire experiment.

While both you and your counterpart may submit a request to extend the other’s recorded time, only one person’s request will be implemented. That implementation will be decided at the end of the experiment. With probability 50% your request will be implemented. With a probability of also 50% the request of the other participant will be implemented. If it turns out that the person randomly selected had decided not to submit a request, then no time extension will be implemented at all.

Please recall that we will only inform you about the time it took you to correctly count 10 tables.

Please recall that we will inform you both about the time it took each of you to correctly count 10 tables, and the time the other participant has needed.

For your earnings from estimating the time the other participant needs for correctly counting 10 tables a potential extension of the time recorded for him is irrelevant.

You are now being asked whether you would choose to submit such a request and, if so, what fraction of your endowment you chose to invest. If you do not want to extend the time that is recorded for the other participant, please indicate ‘0’.

Part 4

<Holt Laury test for risk preference>

Part 5

Questionnaires

Part 6

<Tables to solve>

Part 7

< Feedback on all parts of the experiment >