Series Preface

Urban Climate Change Research Network

Third Assessment Report on Climate Change and Cities (ARC3.3)

William Solecki (New York), Minal Pathak (Ahmedabad), Martha Barata (Rio de Janeiro), Aliyu Salisu Barau (Kano), Maria Dombrov (New York), and Cynthia Rosenzweig (New York)

Cities and the urbanization process itself are at a crossroads. While the world’s urban population continues to grow, cities are increasingly pressed by chronic and acute stresses like increasing inequity, polluted air and waters, limited governance, and financial capacities, along with entrenched spasmodic crime and conflict – and the COVID-19 pandemic. Climate change has now exacerbated these problems and in many cases created new ones, at a time when cities are asked to be the bulwark of the climate-solution space. The advent and application of new technologies and strategies associated with the internet, environmental sensing, multi-modal transport, and innovative planning and design strategies portend a new golden age for cities. Some cities provide glimmers of this possible future, but persistent stresses and intermittent crises, along with climate change, push against progress. In the Urban Climate Change Research Network’s (UCCRN’s) Third Assessment Report on Climate Change and Cities (ARC3.3), we address these issues head-on and present state-of-the-art knowledge on how to bring all cities and their residents forward to a more sustainable future.

An absolute necessity now exists for cities everywhere, both in the Global North and Global South, to aggressively work to fulfill their potential as leaders in climate change action. In the Global North, the task is for cities to address the emerging challenges from the changing climate and the exigencies of compliance with the UNFCCC Paris Agreement. For cities in the Global South, there is the double burden of achieving climate-resilient development, that is, meeting increasing demand for housing, energy, and infrastructure for burgeoning populations, while confronting simultaneous requirements to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and adapt to a changing climate (UNEP & UN-Habitat, 2021). In all geographies, the implementation of transformative mitigation and adaptation in cities can be an instrument to generate livelihoods for those with lower purchasing power and can enhance capacity to better respond to shocks like future pandemics, energy supply chain spasms, and food security emergencies (UNDP, 2022).

Benchmarked Learning

ARC3.3 builds upon the preceding UCCRN Assessment Reports on Climate Change and Cities (ARC3), ARC3.1 (2011) and ARC3.2 (2018). The purpose of the ARC3 series is to provide the benchmarked knowledge base for cities as they affirm their essential responsibility as climate change leaders. The ARC3 Series, with newly added ARC3.3 Elements, presents knowledge that builds on accumulated and shared experiences and thus advances and deepens with time.

In ARC3.1, cities were identified as key actors – “first responders” – in rising to the challenges posed by climate change (Rosenzweig et al., Reference Rosenzweig, Solecki, Hammer and Mehrotra2011). According to ARC3.1, “Cities around the world are highly vulnerable to climate change but have great potential to lead on both adaptation and mitigation efforts.”

In ARC3.2, this focus advanced into understanding how cities can achieve their potential by establishing a multifaceted pathway to transformation (Rosenzweig et al., Reference Rosenzweig, Solecki, Romero-Lankao, Mehrotra, Dhakal and Ali Ibrahim2018). It provided a roadmap for cities to fulfill their leadership potential in responding to climate change. According to ARC3.2, “As cities mitigate the causes of climate change and adapt to new climate conditions, profound changes will be required in urban energy, transportation, water use, land use, ecosystems, growth patterns, consumption, and lifestyles.”

Now, as the urgency of climate change is brought home daily, ARC3.3 offers the knowledge needed to speed up and scale up urban action on climate change. To accomplish this, it presents practical methods and case study examples for accelerating change into rapid transformation in cities across the globe.

UCCRN Assessment Process

The ARC3.3 authors were either self-nominated or nominated by a third-party and were selected by the ARC3.3 Editorial Board through comprehensive vetting that prioritizes expertise, diversity, gender, and geographic balance. Each author team develops a robust assessment of an Element topic using the latest literature, while also conducting new research. All Author Teams are responsible for conducting a stakeholder engagement session during the writing period with the goal of ensuring relevance to a diverse group of urban decision-makers. During self-coined “stakeholder soundings,” authors present emerging major findings and key messages to stakeholders, including city leaders from the authors’ home cities, for their feedback. UCCRN also coordinates a rigorous iterative peer-review process for each ARC3.3 Element that engages with both academic and practitioner experts, both in and out of the network.

The UCCRN’s Case Study Docking Station (CSDS) is a searchable database designed to facilitate peer learning between and among cities, benchmark actions over time, and enable cross-comparisons of city case studies.Footnote 1 The CSDS includes more than 200 peer-reviewed case studies covering a range of topics such as climate change vulnerability, hazards and impacts, and mitigation and adaptation actions for specific sectors. The CSDS has a total of sixteen searchable variables.Footnote 2 For example, users can filter searches by climate zone, city population size, human development index, gross national income, or mitigation versus adaptation, or directly type in keywords and city names. Case study examples include flood adaptation in Bridgetown, cloudburst planning in Copenhagen, and climate action financing in Durban.

Cities are vanguard sites for opportunities to enhance equity and inclusion. Besides the ARC3.3 Justice for Resilient Development in Climate-Stressed Cities Element, equity and inclusion permeate every ARC3.3 Element. City experts delve into the multiple dimensions of climate change justice: distributive (relating to the differential vulnerability of groups and neighborhoods), contextual (relating to the root causes of vulnerability), and procedural (relating to participation in decision-making for climate change interventions) (Foster et al., Reference Foster, Leichenko, Nguyen, Blake, Kunreuther, Madajewicz, Petkova, Zimmerman, Corbin-Mark, Yeampierre, Tovar, Herrera and Ravenborg2019). The concepts of recognitional (valuing of diverse identities) and restorative justice (restoring dignity and repairing the societal harm caused by earlier actions) are now emerging, as well. Elucidation of ways to achieve all types of climate justice for the most vulnerable urban groups and equal access to financial and technological resources for all cities underpins ARC3.3.

ARC3.3 Elements

City-centered assessments have been conducted by UCCRN since its founding in 2007. With more than 2,000 scholars and experts from cities around the world, UCCRN is addressing the research agenda that was formulated at the IPCC Conference on Cities and Climate (Prieur-Richard et al., Reference Prieur-Richard, Walsh, Craig, Melamed, Pathak, Connors, Bai, Barau, Bulkeley, Cleugh, Cohen, Colenbrander, Dodman, Dhakal, Dawson, Greenwalt, Kurian, Lee, Leonardsen, Masson-Delmotte, Munshi, Okem, Delgado Ramos, Sanchez Rodriguez, Roberts, Rosenzweig, Schultz, Seto, Solecki, van Staden and Ürge-Vorsatz2018).Footnote 3 Key components of this research agenda include urban planning and design, green and blue infrastructure, equity, health, sustainable production and consumption, and finance. More than 300 UCCRN authors have now advanced this research agenda and other critical topics through ARC3.3 (Solecki et al., 2025), which consists of twelve peer-reviewed monographs to be published as Cambridge University Press Elements, both separately and together, throughout 2025 and 2026.

Within twelve critical topics on climate change and cities, ARC3.3 synthesizes the latest scientific knowledge in the field while presenting new research findings and offering clear policy recommendations.Footnote 4

1. Learning from COVID-19 for Climate-Ready Urban Transformation

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed gaps in city readiness for simultaneous responses to pandemics and climate change, particularly in the Global South. However, these concurrent challenges present opportunities to reformulate current urbanization patterns, economies, and the dynamics they enable. This Element focuses on understanding COVID-19’s impact on city systems related to mitigation and adaptation, and vice versa, in terms of warnings, lessons learned, and calls to action.

2. Justice for Climate-Resilient Development in Climate-Stressed Cities

To ensure climate-resilient urban development, both adaptation and mitigation must include the broader city context related to equity, informality, and justice. Responses to climatic events are conditioned by the informality of the existing social fabric, institutions, and activities, and by the inequitable distribution of impacts, decision-making, and outcomes. This Element discusses differential exposure to climate events as well as distributive, recognitional, procedural, and restorative justice.

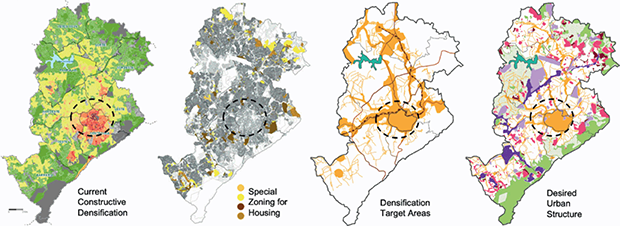

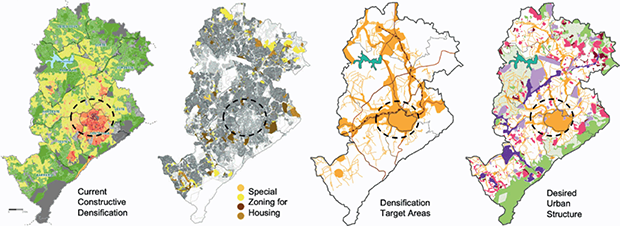

3. Planning, Urban Design, and Architecture for Climate Action

Planners, urban designers, and architects are called on to bridge the domains of research and practice and evolve their capacity and agency by developing new methods and tools that are consistent across multiple spatial scales. These are required to ensure the convergence of effective outcomes across metropolitan regions, cities, neighborhoods, and buildings. This Element evaluates how the fields of planning, urban design, and architecture integrate climate mitigation and adaptation and presents a manifesto for urban transformation using science-informed methods and tools.

4. Financing Urban Transitions to Climate Neutrality and Increased Resilience

This Element documents the availability of, and access to, finance for mitigation and adaptation in urban areas in both the Global South and Global North. It evaluates current international flows, national policies, and municipal utilization capacities across private and public sectors, nongovernmental (NGOs), and community-based organizations (CBOs). Global financial capital is abundant but often flows to corporate investments and real estate development rather than into critical efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change in cities. It presents innovative financial mechanisms including insurance and mobilization strategies for cities. Political will and public pressure are crucial to effectively redirect these funds.

5. Urban Climate Science: Knowledge Base for City Risk Assessments and Resilience

Cities alter the climate system both within their boundaries and nearby through interactions with impervious land surfaces, energy generation facilities, and transportation systems. These processes that occur on urban scales are interacting with larger-scale climate change processes to exacerbate extreme events that impact urban dwellers. This Element provides observations and projections of temperature, precipitation, and sea level change for the cities engaged in ARC3.3 and assesses the latest research on urban heat and precipitation islands, compound extreme events, and indicators and monitoring, including the use of remote sensing in urban settings.

6. Governance, Enabling Policy Environments, and Just Transitions

The nature of governance, as a concatenation of social institutions and practices embedded at different scales, suggests the need for an integrated approach to address the complex challenges of climate change in cities. This Element sets forth multi-level governance structures for climate action across urban, regional, national, and international levels, analyzes the inclusion of urban actions in nationally determined contributions (NDCs), and assesses the potential for urban transitions and transformations.

7. Infrastructure for a Net Zero and Resilient Future in Cities

Without infrastructure, cities could not exist. Infrastructure determines urban forms, functions, economic development, and people’s livelihoods and well-being. By developing transformative infrastructure, cities can achieve ambitious GHG emission reductions, build resilience to climate impacts, and ensure inclusive and diverse access to services. This Element explores infrastructure planning concepts like life cycle analysis, decentralization, and integration, and emphasizes the need for equitable, resilient systems designed according to future climate projections.

8. Nature-Based Solutions: Enhancing Capacity to Respond to Shocks and Stresses

There is a growing acknowledgment that a disproportionate amount of attention and finance is invested in hard infrastructure to mitigate and adapt to climate change in cities. In contrast, soft infrastructure, which is the use of natural features and processes, has been comparatively overlooked until recently. This Element assesses the ways that nature-based solutions (NbS) – such as reforestation, urban parks, street trees, sustainable urban drainage systems, and community gardens – can enhance the capacity of cities to reduce GHG emissions and enhance resilience to climate stresses.

9. Circular Economies for Cities

Circularity – an economic system where waste and pollution is minimized and resources are continuously reused – has the potential to transform cities and city systems in both the Global North and the Global South. Sustainable consumption and production and supply and demand factors are increasingly coming into focus in cities. This Element discusses the linkages of circular economies to climate action planning, the water–energy–food–system nexus, and just, local development.

10. Data and the Role of Technology

Over the past decade, changes in internet penetration and the development of new information and communication technologies have catalyzed an ecosystem of approaches that employ “big data” and “smart tools” to support adaptation and mitigation. Artificial intelligence and machine learning play a large role in this new technological ecosystem. This Element assesses the opportunities and challenges for cities as they employ these new technologies and evaluate emerging tools for their utility in climate change responses.

11. Perception, Communication, and Behavior

This Element explores the latest research on how urban residents perceive climate change so the effectiveness of actions can be improved. An important corollary to this is the role that communication plays in how mitigation and adaptation actions are adopted by cities. In the event of a climate disaster, the way that cities communicate has a direct effect on residents’ perceptions of risks and their subsequent behaviors, such as evacuation or strategic relocation. The Element addresses how behaviors by urban inhabitants can be encouraged to change mobility patterns and energy use in order to reduce GHG emissions, while simultaneously helping citizens to prepare for increasing climate extremes.

12. Health and Well-Being

Climate change, especially increasing extreme events, are exacerbating the risks of mortality, disease, and injury and the impacts on physical and mental health and well-being in many cities. Climate change also has indirect impacts on health through disruptions in food supply and water availability. This Element assesses the latest findings on all aspects of the intersection of health and climate change for urban residents – including built form, such as the presence of natural spaces.

ARC3.3 Major Findings and Key Messages

Besides the basic assessment content, each Element includes a statement of major findings and key messages. Major findings bring forward significant new knowledge that emerged through the assessment process, while key messages are recommendations for new direction efforts and activities with a specific focus on opportunities to speed up and scale up urban climate action.

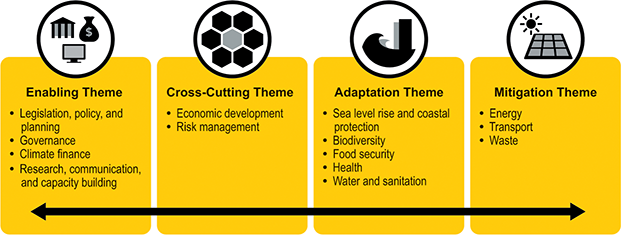

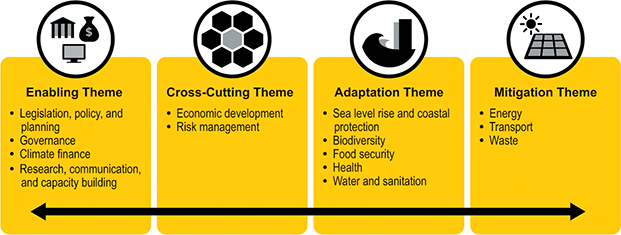

Cross-Cutting Themes

Cities are complex social–ecological–technological systems. While ARC3.3 is composed of twelve separate Elements, together they comprise multiple synergies, interdependencies, and points of intersection. To address these connections, each Element addresses its own selection of relevant cross-cutting themes. Figure 1 illustrates how significant recurring themes appear within the Element and the interlinkages to related Elements. Cross-cutting themes (CCTs) encompass drivers of urban function, change, and management; governance of cities across municipal, state/provincial, national, and international levels; and the role of city-level models and data.

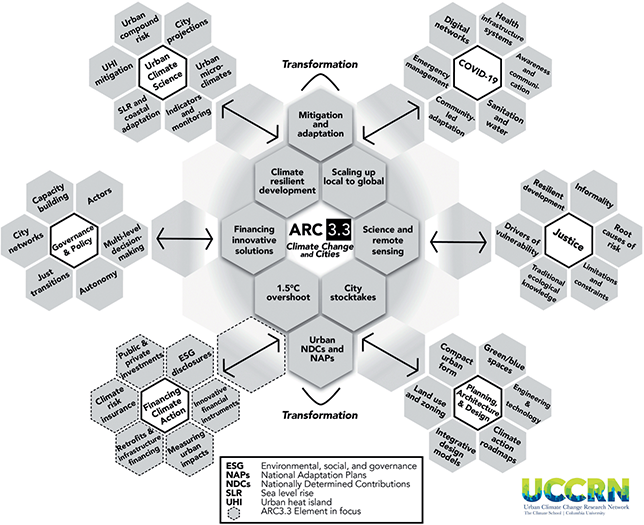

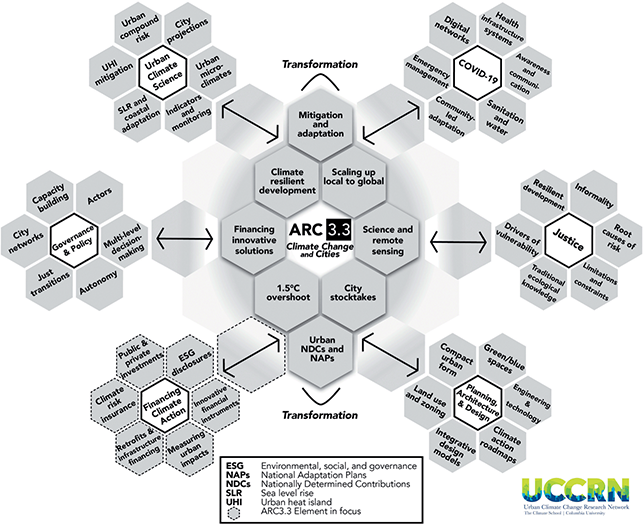

Figure 1 Cross-cutting themes associated with the overall ARC3.3 assessment and the first six Elements, with the Finance Element in focus. This figure is also available to view online at www.cambridge.org/meyer-et-al

Figure 1Long description

The diagram has a central hexagon labeled ARC 3.3 Climate Change and Cities. Surrounding this central hexagon are eight hexagons labeled: Climate resilient development, Mitigation adaptation (with the word Transformation above it), Scaling up local to global, Science and remote sensing, City stocktakes, Urban N D C s and N A P s (with the word Transformation below it), 1.5-degree Celsius overshoot, and Financing innovative solutions. This group is further connected to 6 other clusters of hexagons with different labels all around it. Cluster 1: Urban Climate Science. It is surrounded by 6 hexagons labeled City projections, Urban micro-climates, indicators and monitoring, S L R and coastal adaptation, U H I mitigation, and Urban compound risk. Cluster 2: COVID-19. It is surrounded by 6 hexagons labeled Health infrastructure systems, Awareness and communication, Sanitation and water, Community-led adaptation, Emergency management, and Digital networks. Cluster 3: Justice and Equity. It is surrounded by 6 hexagons labeled Informality, Root causes of risk, Limitations and constraints, Traditional ecological knowledge, Drivers of vulnerability, and Resilient development. Cluster 4: Planning, Architecture and Design. It is surrounded by 6 hexagons labeled Green/blue spaces, Engineering and technology, Climate action roadmaps, Integrative design models, Land use and zoning, and Compact urban form. Cluster 5: Financial Action. It is surrounded by 6 hexagons labeled E S G disclosures, Innovative financial instruments, Measuring urban impacts, Retrofits and infrastructure financing, Climate risk insurance, and Public and private investments. Climate 6: Governance and Policy. It is surrounded by 6 hexagons labeled Capacity building, Actors, Multi-level decision-making, Autonomy, Just transitions, and City networks. At the bottom, there is a note explaining abbreviations: E S G - environmental, social, and governance, N A Ps - National adaptation plans, N D Cs - Nationally determined contributions, U H I - urban heat island, and S L R - sea level rise. The diagram is branded with U C C R N Urban Climate Change Research Network at the bottom right.

Because the fundamental contribution of the ARC3 series is to enable a learning process for urban climate action, CCTs across the ARC3.3 Elements aim to shed light on cause-and-effect relationships and elucidate effective entry-points for interventions. This focused knowledge of urban social–ecological–technological systems can inform planners, implementers, and other city actors as they undertake ways to translate the latest science into climate action in their own urban communities.

Conclusion

We are pleased to present the Financing Urban Transitions to Climate Neutrality and Increased Resilience Element of the UCCRN Third Assessment Report on Climate Change and Cities (ARC3.3). This important Element sets forth the knowledge foundation as well as the practical tools needed to unlock much-needed resources for city climate action, both mitigation and adaptation. The authors make a powerful argument for broadening the conceptualization of finance in order to convince both public- and private-sector actors – including global funds, multinational development banks, national governments, and private-sector organizations – that cities are indispensable climate partners worthy of investment. The Element thus simultaneously provides the key information needed to both jumpstart and upscale finance for city climate action.

Foreword I – Eugenie Birch, Lawrence C. Nussdorf Professor of Urban Research and Education, University of Pennsylvania; Co-Director, Penn Institute for Urban Research

With the world’s population growth exploding – 2050 will see the addition of some two billion inhabitants, primarily in cities in low- and middle-income countries of Africa and Asia – public and private decision-makers are pressed to meet basic infrastructural needs (transportation, water and sanitation, public space, electricity, social service facilities) while responding to such global issues as climate change, poverty eradication, and sustainable economic growth. Further, the COVID-19 pandemic revealed additional weaknesses in national and subnational infrastructure. Finally, countries are experiencing inflation and high interest rates – phenomena that affect how the cities of the world are managing.

Since cities produce more than 70 percent of the planet’s total CO₂ emissions, they present the critical arena for the implementation of climate-resilient development strategies – ones that address mitigation, adaptation, and poverty alleviation simultaneously (Luqman et al., Reference Luqman, Rayner and Gurney2023). With some 60 percent of global infrastructure needed in 2050 yet to be built, huge investments are required. UN-Habitat estimates that in emerging-economy cities alone, annual costs range from US$20 million to US$50 million in small cities (under 100,000 inhabitants) to US$140–500 million in medium cities (100,000 to million inhabitants), and US$600 million in large cities (+1 million inhabitants). This adds up to $4.3 TK, a sum greatly exceeding today’s current spending of US$831 billion reported by the City Climate Finance Leadership Alliance’s 2024 State of City Climate Finance report. Despite some progress in city-focused financing, the existing mechanisms fall short of the magnitude of resources needed.

The question is how to raise the funds required. The answer calls for designing a fit-for-purpose financing architecture to replace today’s circa-1940s system developed when the world was not nearly so urbanized. This monumental challenge is not impossible. Financing Urban Transitions to Climate Neutrality and Increased Resilience shows the way. It calls for blended finance (public and private investments) supported by improved risk assessment models and the development, refinement, and implementation of new investment tools.

Foreword II – Kevin Chika Urama, Chief Economist/VP for Economic Governance and Knowledge Management Complex, African Development Bank Group

Cities across the world consume 78 percent of global energy and produce over 60 percent of total GHG emissions while covering only 2 percent of the world’s surface. As UN Secretary-General António Guterres rightly put it, “cities are where the climate battle will largely be won or lost and the choices that will be made on urban infrastructure in the coming decades … will have a decisive influence on the emissions curve.”Footnote 5

Nonetheless, the reality is that there is what I call “the paradox of climate action financing in cities.” Despite their huge climate finance needs resulting from their undisputable role in driving global warming – and hence in meeting Paris Agreement goals – and their being home to 55 percent of the world’s population – a figure expected to rise to 68 percent by 2050 – cities remain largely underfinanced, in particular in Africa, jeopardizing their transition to climate neutrality and resilience.

Addressing the enormous climate investment gap for cities in Africa and elsewhere is critical for putting the world on a sustainable development path and, subsequently, for meeting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The world is not short of capital to finance all climate adaptation and mitigation in cities. However, to attract those resources, we need to better understand the dynamics of climate finance for cities. This requires sustained efforts to build a strong knowledge base on issues such as: the potential costs of climate-related events in cities; private-sector climate investment decisions; appropriate institutional arrangements; and the specific needs of cities in the Global South, particularly in Africa.

The Third Assessment Report on Climate Change and Cities has kept the promise of previous reports produced by UCCRN by advancing our knowledge in the important area of climate change mitigation and adaptation in cities. In particular, the ARC3.3 Finance Element comes at a decidedly opportune time, as the global community needs sound knowledge to ramp up efforts to address the acute climate challenges facing cities around the world. The Element highlights the critical role of public-sector measures, innovative financial instruments for urban areas, the insurance industry, and the development of financial markets in cities of the Global South in addressing market failures and moving more funds toward urban climate change actions. It further provides pragmatic directives to key stakeholders to fast-track financial flows to cities and address the climate crisis they currently face.

Dealing with urban climate change does not have to be a zero-sum game, with winners and losers, but can be turned into a win-win solution for all stakeholders. Cities are projected to present a climate investment potential of nearly US$30 trillion by 2030, of which US$1.3 trillion will be in Africa. Investors, cities, and public actors will need to work together to actualize this potential.

Series Editors’ Introduction to Financing Urban Transitions to Climate Neutrality and Increased Resilience

Despite adequate supplies of global capital, climate action in cities – both in often-overlooked small and medium-sized cities and in the growing urban megacities in the Global South and Global North – has long been stymied by a lack of effective financing. Once funded, cities often face difficulty in measuring the results of climate action in their localities, further hindering investments. To address this multifaceted impasse, the ARC3.3 Element Financing Urban Transitions to Climate Neutrality and Increased ResilienceFootnote ‡ presents ways to expand conceptual frameworks, integrate risk from worsening climate hazards, and develop innovative financial instruments, including insurance. It also engages with the need for cities to enhance their financial acumen through capacity expansion and training.

The Element has a special focus on African cities, where needs for financing are particularly dire. While the flow of finance is the driving force for building climate-resilient cities in Africa, urban climate finance flows to cities averages there just US$3 billion a year in 2018 (CCFLA, 2021). Despite a 10.9 percent increase in 2018, the whole of Africa secured only 3.5 percent (US$46 billion) of global foreign direct investment – leaving large parts of its growing cities described by financiers as “high risk” and citizens deemed “unbankable.” As of 2015, Africa faced an estimated 40 percent infrastructure financing gap, which is almost certainly higher in the continent’s rapidly growing cities.

Overall, the ARC3.3 Finance Element contributes to the acceleration of equitable and actionable multi-level flows of innovative financing required for cities to achieve their long-called-for and essential climate leadership. It assesses recent analyses of the role of cities as financial agents of climate change solutions and how to advance and secure financing. It provides much more explicit directives to key public and private-sector actors needed to facilitate accelerated flows and improved accessibility of critical resources required to fast-track collective responses to the climate crisis.

This Element not only explains why city governments and institutions that manage and sustain everyday city life often lack financial resources for climate action, but also presents concrete financial mechanisms to address these challenges. The meaningful integration of financing into many settings, especially in developing country contexts or under conditions of informality, faces a variety of challenges, including the role of powerful vested interests, entrenched inequities, corruption, and broader market forces that drive development. Finance, insurance, and real estate developers, as well as other private-sector and multi-level government actors, have key responsibilities in enabling city transformations.

The ARC3.3 Finance Element authors argue that cities need to adhere to the evolving standards related to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations in order to unlock greater climate finance. This global movement will guarantee that investments support the broader goals of a just transition rather than exclusively benefiting a privileged few by remaining focused on private profits. This Element also lays out how NbS connect to the SDGs and how together they fit into the ESG framework. The approach should help make investing in natural capital more attractive to institutional investors with relatively long horizons, especially for Global South projects.

The Element then focuses on the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and its role in setting standards for climate-related financial reporting. It emphasizes that disclosing climate-related information is becoming an important factor determining borrowing costs since investors impose higher costs on municipalities that they perceive have greater exposure to climate risks.

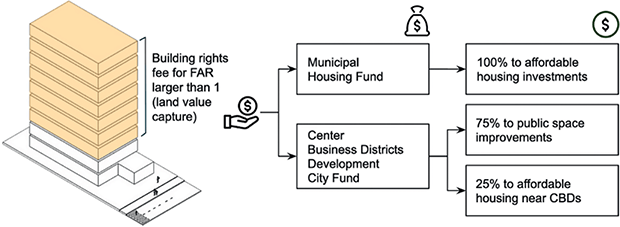

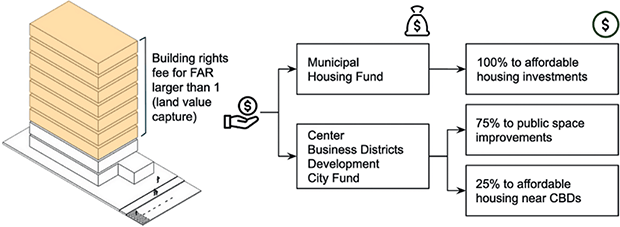

The ARC3.3 Finance Element presents innovative mechanisms for tackling climate change effectively and enhancing resilience by prioritizing adaptation and associated risk reduction to attract investment. It introduces the social, economic, and environmental value of mitigation actions (SVMA) framework, which complements ESG and TCFD measures. Financial tools and mechanisms that aim to mobilize funds for climate-related initiatives include green bonds, natural capital pricing, land value capture (LVC),Footnote 6 carbon pricing, energy service companies (ESCOs), and de-risking strategies. A key mechanism described in the Element is how insurance can play a crucial role in managing climate risk for cities, its functions, limits, accessibility, and affordability, and scenarios for sustainable insurance in the face of climate risk (Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Sushchenko and Schwarze2025).

This Element calls for profound and urgent scaling up and speeding up of urban climate action. New ways forward are transformative flows through finance systems both within and between cities. The goal is to achieve fully resourced financing for equitable, resilient net-zero cities. Following the recommendations set forth in the ARC3.3 Finance Element will empower all city actors to unblock climate finance for action in their own urban communities.

Major Findings and Key Messages

Major Findings

1. Sufficient investment capital exists in world markets to finance needed climate change mitigation and adaptation in cities. However, that capital is largely locked in corporate investments and real estate, and it is not yet directed to supporting urban climate action. Greater political will and public pressure is required to move more funds toward urban climate change mitigation and adaptation measures (Sections 1 and 6.3).

2. Studies of economic impacts of climate change in cities understate potential costs by failing to include the cumulative effects of direct losses from heat, fires, floods, and storms. Investors, governments, and multinational financial institutions thus underestimate the returns from avoided losses available through reduced urban climate change impacts due to mitigation and adaptation (Section 7.6).

3. An urgent need exists to both build financial capacity and increase financing for cities in the Global South, especially for climate adaptation, which receives much less funding than mitigation. Despite the importance of climate finance in building resilient cities in the Global South, urban climate finance in Africa, for example, remains significantly low, with their cities receiving only an average of US$3 billion annually (Sections 2, 5.1, and 7.3).

4. Market rate debt is among the top instruments for urban climate finance. For example, among international banks the European Investment Bank (EIB) has allocated some of the largest volumes of direct urban climate mitigation loans. Urban loans for climate mitigation and adaptation allocated from the EIB between 2017 and 2021 totaled approximately US$124 billion to mostly EU countries. Other common financial instruments include green bonds, pricing natural capital, land value capture, carbon pricing, and de-risking (Section 2).

5. Cities that incorporate sustainability issues and co-benefits of climate projects into their master plans are more likely to receive additional funding. Data show that cities incorporating climate resiliency and environmental and social co-benefits into urban master plans were between two and two and half times more likely to identify opportunities for advancing action, including new businesses and financing resources, than projects that did not (Section 4.2).

6. Recent formalization of the International Sustainability Standards Board nonfinancial disclosure standard is important to ensure expanded climate expenditures in cities. This standard is maintained by the Taskforce on Climate-Related Disclosures (TCFD). Voluntary regulations regarding climate finance mobilization or disclosure of nonfinancial (i.e., ESG) information in financial markets are evolving into legally binding provisions, already promulgated in China and the EU (Section 4.1).

7. Climate investments in cities are a growing priority for both public and private parties as well as for multilateral development banks (MDBs). Climate finance negotiations at COP29 in Baku resulted in a pledge to mobilize US$300 billion annually for developing countries by 2035, with the long-term target to increase climate finance flows to US$1.3 trillion per year by 2035. This US$1.3 trillion target includes private-sector finance; however, the pledge still falls short of the financial needs of vulnerable nations and remains yet to be fully specified following COP30. The MDBs also pledged to increase climate financing to US$120 billion by 2030: a 60 percent increase from the amount in 2023. Enabling conditions for private sector participation include carbon markets, the introduction of carbon taxes, and fostering of energy service companies (ESCOs) (Section 9).

Key Messages

1. Climate change financing in cities should align with both the ESG framework and the SDGs to promote a just transition to a low emissions and resilient world. The ESG framework and the SDGs are synergistic, especially in relation to SDG 11, which aims to “make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable.” By integrating both frameworks, cities can foster more equitable and resilient communities that harness both environmental and economic progress. This alignment also ensures that investments drive broader social outcomes, such as poverty reduction and inclusion. A dual focus on ESG and SDGs will create long-term value that benefits all urban residents, particularly vulnerable populations.

2. The “climate investment trap” must be addressed, where by the underdeveloped financial markets pose risks for investors that translate into higher costs for accessing climate finance. Limited experience with formal debt instruments and financial markets leaves cities in the Global South with poor credit ratings, further raising the cost of capital and limiting access to credit markets. Measures to support local climate impact data collection and analysis and training to improve credit standings must be priorities for addressing the Global North–South divide in access to urban climate finance.

3. Public-sector measures, such as guarantees, and forms of blended finance, such as combining public funds with private capital, are necessary to attract private investment for climate change action in cities. Carbon prices, carbon credits, biodiversity funding, and other prospective local income sources (e.g., land value capture) can be additional sources of revenue for cities, in addition to traditional public funding, such as loans, direct investments, grants, and development aid funds.

4. Development and implementation of innovative financial instruments for urban areas are urgently needed. These include green bonds, nonfinancial returns on investment, public-private climate partnerships, and debt-for-climate swaps. By diversifying funding sources and utilizing blended finance models, cities can decrease risks and ensure more stable and reliable finance flows. Additionally, these mechanisms can foster greater private-sector involvement, aligning financial returns with broader environmental and social outcomes.

5. The insurance industry is encouraged to play a dramatically more significant role in urban climate finance as investor and resilience actor. As investors, insurance companies control massive assets, and as interested parties, they are concerned with limiting future climate-induced costs through the promotion of adaptation efforts. Insurance companies could set up new alliances with cities to provide data, assess risks, and finance local adaptation, provided that the firms recognize the benefits of urban climate change risk reduction.

6. The creation of independent information centers at regional, national, and global levels can provide reliable data to reduce financial risks. Rating agencies, microfinance institutions (MFIs), multilateral development banks (MDBs), and other bodies (e.g., OECD and TCFD) could gather and provide information and promulgate risk-assessment standards. Having a unified data approach to validation and verification of climate action will help to de-risk investments.

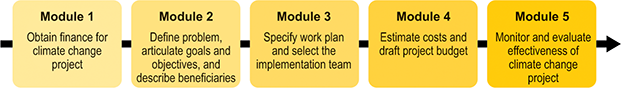

1 Introduction and Framing

Increasing impacts of climate hazards pose severe risks, especially in urban areas, where 55 percent of the world population lives today, accounting for over 70 percent of global fossil-fuel greenhouse gas GHG emissions (IPCC, Reference Pörtner, Roberts, Tignor, Poloczanska, Mintenbeck, Alegría, Craig, Langsdorf, Löschke, Möller, Okem and Rama2022a, Reference Shukla, Skea, Slade, Khourdajie, van Diemen, McCollum, Pathak, Some, Vyas, Fradera, Belkacemi, Hasija, Lisboa, Luz and Malley2022b; UNSD, 2023). This ARC3.3 Element tackles the urgent need to attract nonlocal public and private capital to enable climate action mitigation and adaptation projects in cities (Figure 2). Poor credit ratings and lack of municipal capacity place the cities of the Global South on the investment periphery, with chronically insufficient access to climate finance. The Element addresses the needs of investors to identify climate-related factors that have implications for a city’s financial conditions, such as the rising cost of capital due to growing concerns about the need for climate resilience actions.

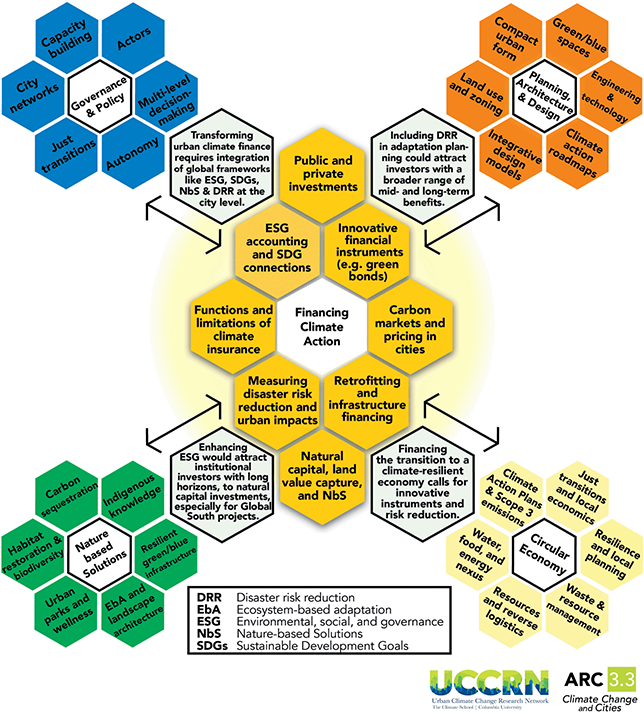

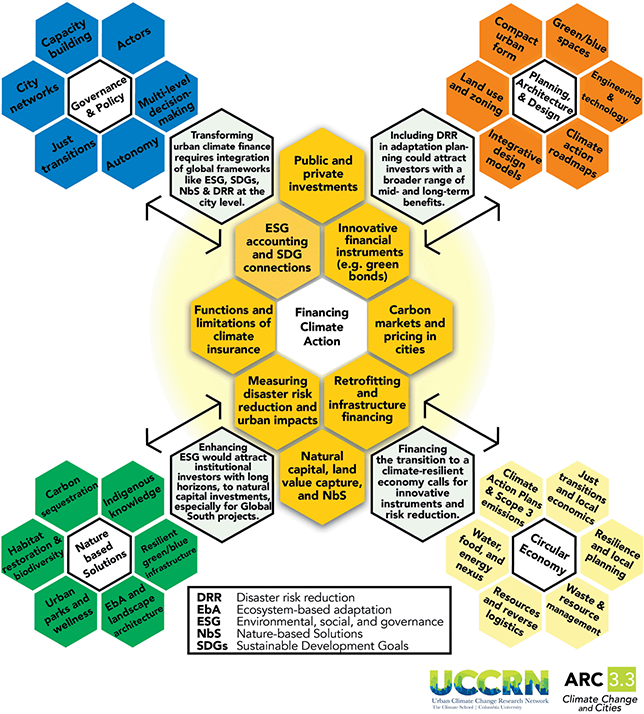

Figure 2 Cross-cutting themes linking ARC3.3 Finance to other Elements.

Figure 2Long description

At the center of the diagram is Financial Climate Action. Surrounding it are 8 hexagons with the texts Public and private investments, E S G accounting and S D G connections, Innovative financial instruments (for example, green bonds), Functions and limitations of climate insurance, Carbon pricing markets in cities, Measuring disaster risk reduction and urban impacts, Retrofitting and infrastructure financing, and Natural capital, land value capture, and N b S. This central cluster is connected to 4 other clusters, through individual actions. Cluster 1: Governance and Policy; connected through Transforming urban climate finance requires integration of global frameworks like E S G, S D Gs, N b 5 and D R R at the city level. Surrounding it are 6 hexagons with the texts: Capacity building, City networks, Just transitions, Autonomy, Multi-level decision-making, and Actors. Cluster 2: Planning, Architecture, and Design; connected through Including D R R in adaptation planning could attract investors with a broader range of mid- and long-term benefits. Surrounding it are 6 hexagons with the texts: Green/blue spaces, Engineering and technology, Climate action roadmaps, Integrative design models, Land use and zoning, and Compact urban form. Cluster 3: Circular Economy; connected through Financing the transition to a climate-resilient economy calls for innovative instruments and risk reduction. Surrounding it are 6 hexagons with the texts: Just transitions and local economics, Resilience and local planning, Waste and management resource, Resources and reverse logistics, Water, food, and energy nexus, and Climate Action Plans and Scope 3 emissions. Cluster 4: Nature based Solutions; connected through Enhancing E S G would attract institutional investors with long horizons, to natural capital investments, especially for Global South projects. Surrounding it are 6 hexagons with the texts: Carbon sequestration, Indigenous knowledge, Resilient green/blue infrastructure, E b A and landscape architecture, Urban parks and wellness, and Habitat restoration and biodiversity. The following abbreviations are noted below: D R R - Disaster risk reduction, E b A – Ecosystem–based adaptation, E S G – Environmental, social, and governance, N b S – Nature–based Solutions, S D Gs – Sustainable Development Goals.

At the city level, the most critical climate risks are extreme heat, severe storms and flooding, rising sea levels, and drought (EEA, 2022)Footnote 7. Improving sustainability and upgrading the nonfinancial disclosure and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) targets across the diverse levels of economic systems will improve the likelihood that cities will fulfill their potential in contributing to meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Agreement warming target (UN, 2015; UNFCCC, 2015b; Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Yaqub and Lee2023).

Urban infrastructure investment includes both mitigation (such as new sustainable power systems and measures to improve energy efficiency) and adaptation projects, including responding to climate-driven disasters and enhancing resilience to future threats (such as building sea walls). Adaptation is likely to be the dominant immediate need, since over 70 percent of the world’s cities had already experienced climate change costs over a decade ago (C40, 2023). This need is most extreme in the Global South, where self-financing adaptation capacities such as those offered by insurance for losses are less widely utilized due to low incomes and inability to pay insurance premiums. The poorer the people, city, or country, the less they will be able to afford the prior funding that insurance and related processes require.

Furthermore, the economic models on which the funding targets are based often fail to incorporate all adverse climate consequences. That flaw leaves the overall commitment to funding climate response and disaster avoidance far lower than it needs to be (Trust et al., Reference Trust, Joshi, Lenton and Oliver2023). While urban climate finance more than doubled to US$831 billion between 2017 and 2022, only US$10 billion was allocated to adaptation projects during 2021–2022 (CCFLA, 2024). Limited municipal capacity to manage programs is a partial explanation for the failure to focus on cities, but so are the systems and institutions through which funds flow from the Global North to the Global South, largely funding nations rather than any subnational units.

Moreover, the inadequacy of those flows has long been evidently problematic for cities because of high-level policy discussions, such as those occurring at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conferences of the Parties (COPs). These discussions have rarely addressed the main domestic issue facing cities in the Global South – i.e., gaining access to the capital that flows to their countries – since financial flows are controlled at the national level.

Climate finance flows from high- and middle-income to low-income countries continue to represent a critical gap, especially when it comes to adaptation funding (UNEP, 2024). The picture of inadequate funding for climate action gets even worse when we focus on cities, where at least 68 percent of all people are predicted to live by 2050 (UN-Habitat, 2022). This growth will mean adding 2.5 billion people to urban areas by 2050, with 90 percent of this increase taking place in Africa and Asia alone and 95 percent of all growth in the Global South as a whole (IPCC, Reference Pörtner, Roberts, Tignor, Poloczanska, Mintenbeck, Alegría, Craig, Langsdorf, Löschke, Möller, Okem and Rama2022a, Reference Shukla, Skea, Slade, Khourdajie, van Diemen, McCollum, Pathak, Some, Vyas, Fradera, Belkacemi, Hasija, Lisboa, Luz and Malley2022b; WEF, 2022a). Yet cities are engines of productivity, generating more than 80 percent of global economic output, so support for their efforts to respond to climate change is essential (WEF, 2022a).

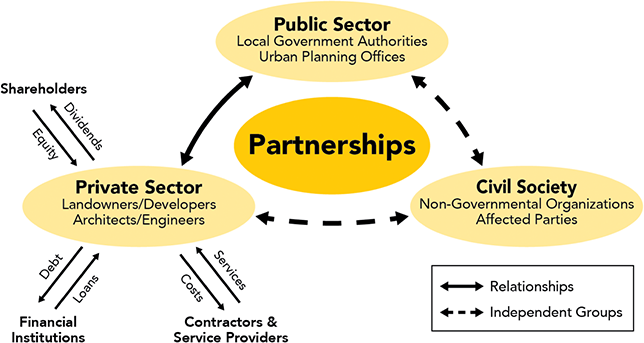

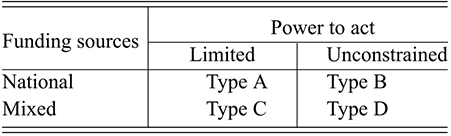

Figure 2 highlights the intersections of the Finance Element with other Elements of ARC3.3 and serves as a framing visualization for the entire analysis. One of the major cross-cutting themes relates to governance levels. International public-sector flows include bilateral arrangements and loans from multilateral development banks (MDBs), all of which are negotiated and implemented at the national level. The limited extent to which national funds flow to cities and the lack of power granted to cities to use these funds may be the primary causes of the constrained capacity of the local public sector to take climate action.

These processes have become self-reinforcing, leaving cities in recipient countries with no capacity to learn to manage programs on their own behalf. This lack of municipal capacity is primarily a problem for cities interested in attracting nonlocal public and private capital to their climate response projects. But given the proportion of the global population living in and migrating to cities, this failure of multilevel governance poses a major barrier to the pursuit of global climate change adaptation and mitigation.

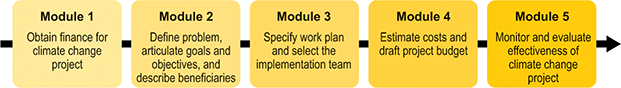

In the ARC3.3 Finance Element, Section 2 addresses climate finance gaps in the Global South, especially highlighting the lack of flows into Africa. The section concludes with an analysis of credit ratings in the Global South, highlighting the climate investment trap many low-income countries are faced with when trying to access necessary climate finance.

Section 3 highlights the importance of addressing ESG targets in climate finance. As private investors increasingly prioritize environmental and social impacts alongside financial returns, their calculations may drive greater interest in climate change responses; thus, it becomes imperative that climate change financing adheres to the ESG framework to guarantee that investments support the broader goals of a just transition, rather than exclusively benefiting a privileged few by remaining focused on private profits.

Section 4 provides insights into the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and its role in setting standards for climate-related financial reporting using a Canadian example. It emphasizes that disclosing climate-related information is becoming an important factor determining borrowing levies since investors impose higher costs on municipalities that they perceive have greater exposure to climate risks.

Section 5 explores innovative mechanisms for tackling climate change effectively and enhancing resilience by prioritizing adaptation and associated risk reduction to attract investment. It then introduces the Social Economic and Environmental Value of Mitigation Actions (SVMA) framework that complements ESG and TCFD measures, delving further into financial mechanisms that aim at mobilizing funds for climate-related initiatives.

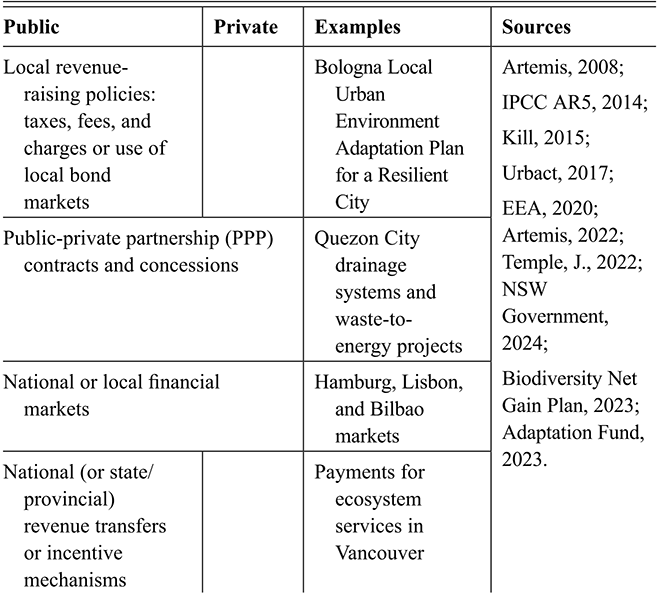

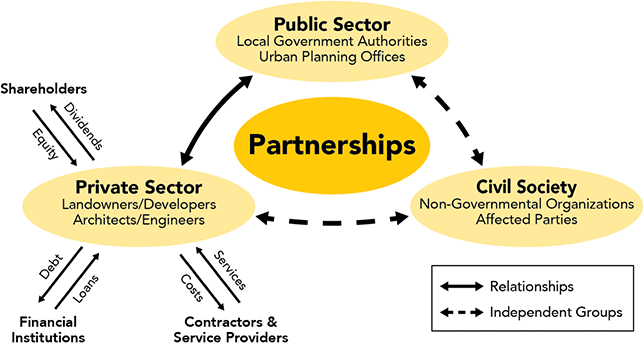

Section 6 discusses urban climate finance mobilization of public and private sectors. Methods of how cities can access public and private finance are presented, as well as the multitude of barriers cities may face when attempting to access these funding streams.

Section 7 assesses instruments that cities can utilize to activate climate finance. Green bonds, valuing natural capital, land value capture, carbon pricing, energy service companies (ESCOs, and de-risking, are all discussed to provide a wide range of potential financial instruments cities can use in a multitude of contexts).

Section 8 examines how insurance can play a crucial role in managing climate risk for cities. It covers the functions of climate insurance, its limits, accessibility and affordability issues, and scenarios for the provision of sustainable insurance in the face of climate risk.

Lastly, Section 9 presents the conclusions and recommendations to enhance the flow of finance into urban climate action.

2 Climate Finance Gaps in the Global South

Global measures of climate finance and cities access to funds often fail to consider even the minimal levels of climate investment required in cities of the Global South where urban growth will be the fastest (Mafira et al., Reference Mafira, Larasati, Mecca, Haesra and Meatlle2021). In these cities, the challenge of an acute mismatch between investment needs and available finance continues, with insufficient financial maturity, lack of investment-grade credit ratings in local debt markets, scarce diversified funding sources and stakeholders, and weak enabling environments (IPCC, Reference Shukla, Skea, Slade, Khourdajie, van Diemen, McCollum, Pathak, Some, Vyas, Fradera, Belkacemi, Hasija, Lisboa, Luz and Malley2022b). Moreover, total financing of climate-related urban investments (including, for example, the financing of zero-emission vehicles) showed roughly US$132 billion committed to North America and Europe, while cities in sub-Saharan Africa received only US$3 billion in 2018 (Climate Policy Initiative, 2021).

2.1 A Global Market Misallocation: Climate Finance in Africa

Despite a 10.9 percent increase in 2018, all of Africa secured only 3.5 percent (US$46 billion) of global foreign direct investment – leaving large parts of its growing cities described by financiers as “high risk” and citizens deemed “unbankable” (Dodman et al., Reference Dodman, Hayward, Pelling, Castan Broto, Chow, Chu, Dawson, Khirfan, McPhearson, Prakash, Zheng, Ziervogel, Pörtner, Roberts, Tignor, Poloczanska, Mintenbeck, Alegría, Craig, Langsdorf, Löschke, Möller, Okem and Rama2022). Although most African cities are acutely exposed to climate-change hazards, as of 2015, Africa faced an estimated 40 percent infrastructure financing gap, and it is almost certainly higher in the continent’s rapidly growing cities (IPCC, Reference Pörtner, Roberts, Tignor, Poloczanska, Mintenbeck, Alegría, Craig, Langsdorf, Löschke, Möller, Okem and Rama2022a).

The funds needed to finance the nationally determined contributions (NDCs) for 51 out of 53 African countries declared at COP25 is estimated to amount to a total of around US$2.8 trillion for the period between 2020 and 2030 (Guzmán et al., Reference Guzmán, Dobrovich, Balm and Meattle2022). That figure represents more than 93 percent of the GDP of all African countries combined. African governments have committed US$ 264 billion (about 10 percent of the total cost) to climate actions. The remaining US$2.5 trillion is dependent on international public and private sources since national budgets and enterprises in Africa do not have the funds for this deployment.

Based on the NDCs, costs for mitigation measures amount to 66 percent of the total (US$1.6 trillion), with results heavily weighted to a few countries, particularly South Africa, mostly for its transport needs (Guzmán et al., Reference Guzmán, Dobrovich, Balm and Meattle2022). Despite Africa being highly vulnerable to climate change and calls for a better balance of finance between mitigation and adaptation, reported adaptation needs in Africa appear to have been severely underestimated (Guzmán et al., Reference Guzmán, Dobrovich, Balm and Meattle2022).

Infrastructure needs for development are so great that it may appear that there is little room for the “luxury” of funding adaptation, let alone mitigation. Of the US$32.5 billion invested in the continent’s transport sector in 2018, only US$100 million could be identified as adaptation finance, suggesting that most finance to the sector is not climate resilient (Guzmán et al., Reference Guzmán, Dobrovich, Balm and Meattle2022). Furthermore, public- and private-sector financial institutions invested at least US$130 billion into fossil fuel companies and projects in Africa between 2016 and 2021.

While it is one of the major green finance organizations, the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) has disbursed only US$22 billion in grants and has leveraged only US$120 billion in co-financing since 1992. For Africa specifically, the GEF has invested $6.2 billion to support the implementation of over 1,800 projects (GEF, 2024). In 2020, the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) mobilized a total commitment of R3.2 billion from various UNFCCC climate financing mechanisms. The DBSA is one of very few development finance institutions that has established programs to provide finance for African cities and towns, which other funding institutions consider to be too risky. Other development finance institutions around the world added more than US$11.2 billion in financing for projects with blended concessional finance, which combines below-market-rate grants or loans to developing countries with finance from public and private sources (i.e., those excluding grants finance or project development assistance), leaving many African nations to turn to internal financing through a combination of green bonds and federal sources (Case Study 1). This figure is a minute fraction of the US$280 billion of investment by 2050 that just the 35 major cities in Ethiopia, Kenya, and South Africa will need to provide compact, connected, and clean cities. (Manthata & Spires, Reference Manthata and Spires2022).

The challenge Africa faces is not just that the Global North has failed to live up to its 2015 Paris Agreement pledge to provide a minimum of US$100 billion a year to support developing countries’ climate responses by 2025 (UNFCCC, 2024). It is that, despite its population and size, the continent has gotten only 3 percent of the funds available from all sources in the wealthy countries.

In 2019, through the collaboration of the city of Kano and the government of Nigeria, Bayero University Kano (BUK) successfully implemented its solar project, part of the Energizing Education Program (EEP). The EEP aims to provide sustainable, clean power to 37 federal universities and seven teaching hospitals across cities in Nigeria, addressing the significant energy challenges faced by these institutions. Nigeria’s dependence on clean energy, particularly in education and healthcare, is vital for sustainable development and climate action, aligning with SDG 7 (ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all).

The EEP delivered power to BUK through solar hybrid and gas-fired captive power plants: electricity generation facilities that supply energy users with a localized source of power. The 7.1 MW solar power plant at BUK, at the time the largest off-grid solar installation in Africa, provides electricity to the campus that houses over 55,000 students and 3,000 staff.

The project is part of Nigeria’s broader goal to enhance energy security and reduce reliance on costly and polluting generators (Nigeria Department of Climate Change, 2020). Funded by the Nigerian government, the full project benefited 127,000 students and 28,000 staff, with additional benefits including street lighting and the decommissioning of generators in Kano (Adeojo, Reference Adeojo2022).

The second phase of the EEP, which will expand the program to more universities and hospitals in cities across the country, will be supported by a US$105 million green bond issued by the Nigerian government with backing from the World Bank (REA, 2022). This phase will further strengthen Nigeria’s commitment to climate action and the SDGs by improving energy access, boosting productivity, and ensuring energy security. With the UN acknowledging the world’s first fully certified sovereign green bond, issued on December 18, 2017, Nigeria became the first country on the African continent and the fourth globally to issue a security that raises funds for environmental projects. This was part of the Sovereign Green Bond Programme (UNECA, 2018).

The success of this collaboration with a city university, particularly the use of green bonds, demonstrates a sustainable model for financing climate projects and sets a precedent for other African countries. By increasing participation in green finance, the program offers a replicable model for addressing energy challenges and driving climate action across the developing world.

Figure 3 The BUK Hybrid Solar Power Plant in Kano.

2.2 Climate Creditors in the Global South

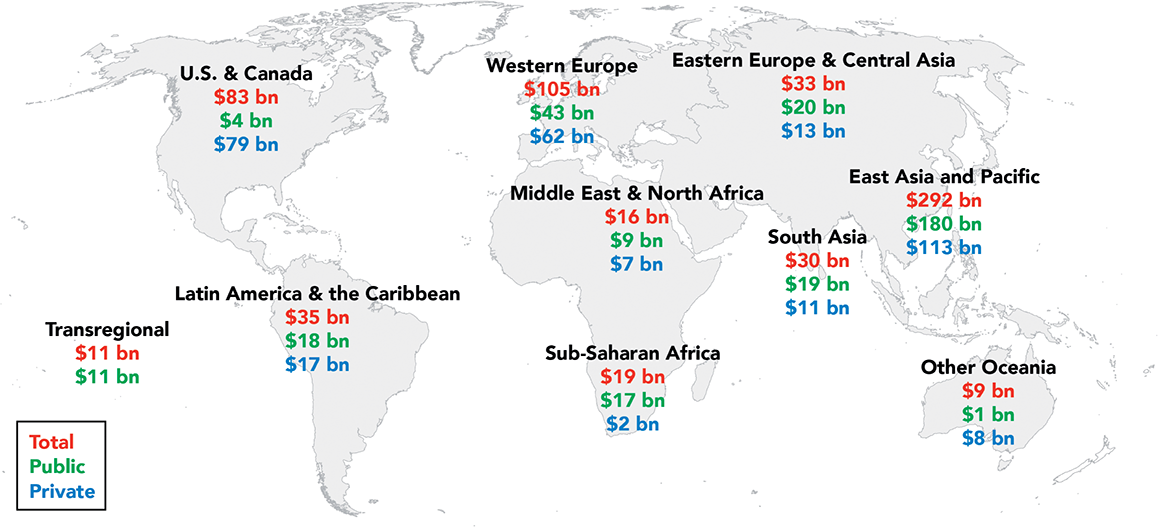

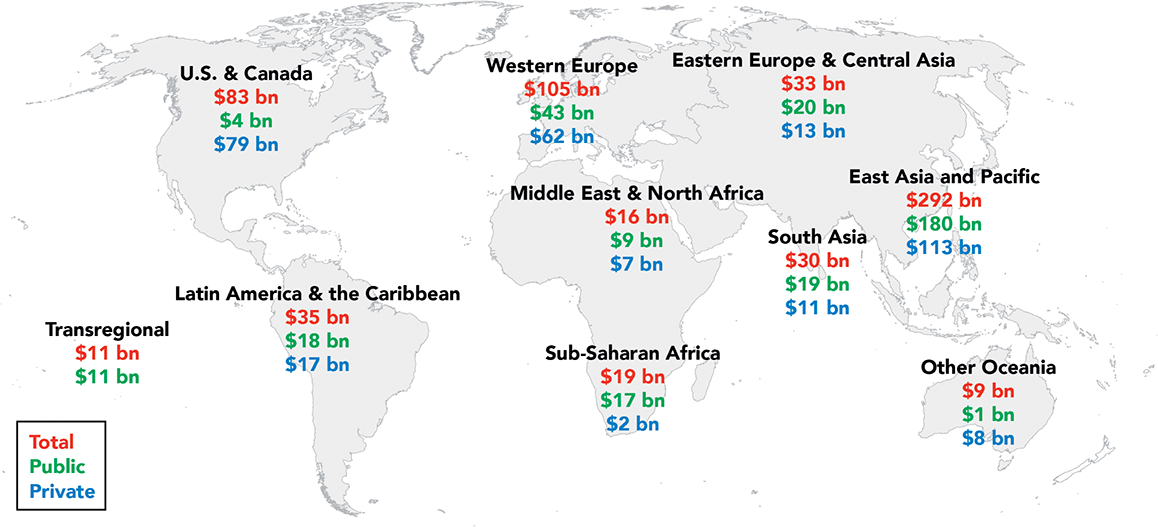

Low-income nations suffer chronically insufficient climate-related investments (Figure 4). This is due to their underdeveloped financial markets being deemed high-risk to investors, who then impose higher costs of access to climate finance (Ameli et al., Reference Ameli, Dessens, Winning, Cronin, Chenet, Drummond, Calzadilla, Anandarajah and Grubb2021). Low credit ratings accompanying these underdeveloped markets translate to higher perceived risk and restricted finance access – a phenomenon that is visible particularly at the city level, where large shifts in climate finance to cities has occurred in the Global North (Bracking & Leffel, Reference Bracking and Leffel2021).

Figure 4 Destination regions of climate finance by source (public and private), showing the annual average flows for 2019/2020 in US$ billions. For each region, three values are listed in the same order: total climate finance, public finance, and private finance.

Figure 4Long description

The Total, Public, and Private finances respectively for each region are as follows. U S and Canada: 83 billion U S D, 4 billion U S D, 79 billion U S D. Latin America and the Caribbean: 35 billion U S D, 18 billion U S D, 17 billion U S D. Western Europe: 105 billion U S D, 43 billion U S D, 62 billion U S D. Easter Europe and Central Asia: 33 billion U S D, 20 billion U S D, 13 billion U S D. Middle East and North Africa: 16 billion U S D, 9 billion U S D, 7 billion U S D. Sub-Saharan Africa: 19 billion U S D, 17 billion U S D, 2 billion U S D. South Asia: 30 billion U S D, 19 billion U S D, 11 billion U S D. East Asia and Pacific: 292 billion U S D, 180 billion U S D, 113 billion U S D. Other Oceania: 9 billion U S D, 1 billion U S D, 8 billion U S D. Transregional: 11 billion U S D, all of it public.

Market rate debt – i.e., the market price investors are willing to buy an organization’s debt – is among the top instruments for urban climate finance (Negreiros et al., Reference Negreiros, Furio, Falconer, Richmond, Yang, Tonkonogy, Novikova, Pearson, Skinner, Boukerche, Mason, Boex and 94Whittington2021). Among international banks, the European Investment Bank (EIB) has allocated some of the largest volumes of direct urban climate mitigation loans (CCFLA, 2015). According to EIB data, urban loans for climate mitigation and adaptation allocated from the EIB between 2011 and 2017 totaled US$165.4 billion and were directed to 108 countries and 228 cities globally, of which 185 cities are in the 23 EU countries and 43 cities are in 25 non-EU countries.

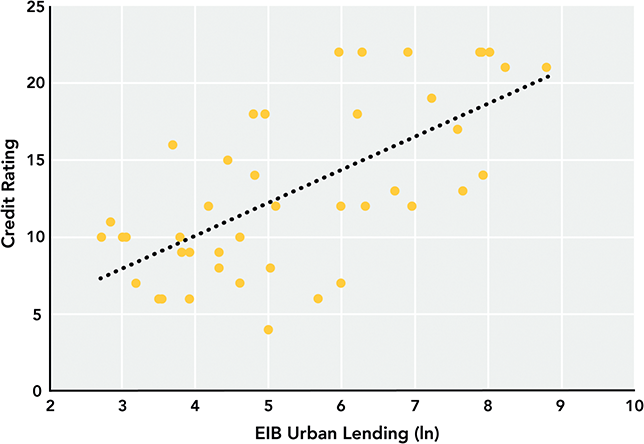

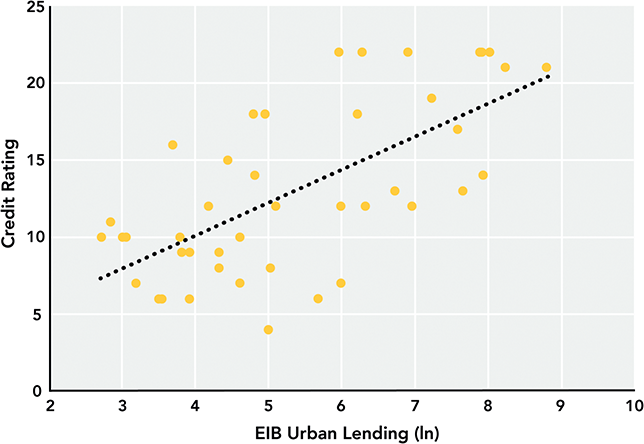

Figure 5 illustrates the positive relationship between national (sovereign) credit ratings (based on the lowest Standard & Poor’s credit rating as 1 and the highest as 22) and the collective EIB direct urban climate lending per country. While city-level credit ratings could be obtained for only a minority (37 of 228) of EIB direct urban climate loan recipient cities, city and corresponding national credit ratings are strongly correlated (p = 0.73). The figure illustrates that countries (and, by extension, their cities) with the lowest credit ratings are those with the least access to EIB direct urban climate lending, and vice versa.

Figure 5 Credit rating and European Investment Bank (EIB) urban climate lending. The larger dots signify countries’ credit ratings, which correlate with higher urban lending.

Figure 5Long description

The x-axis, labeled E I B Urban Lending, ranges from 2 to 10. The y-axis, labeled Credit Rating, ranges from 0 to 25. Most of the plots occur between credit ratings of 5 and 20, and between a lending of 3 and 8. A best fit straight line is drawn from approximately (2.5, 7) to (8.8, 20).

This suggests that lower credit ratings translate to higher costs of access to climate finance for the Global South, restricting access and perpetuating the climate investment trap. A climate investment trap refers to the scenario where the high cost of capital in low-income countries combines with severe climate change impacts, making it difficult for these countries to access credit (Vetter, Reference Vetter2021). These climate finance access restrictions hint at a large population of unacknowledged municipal and national actors with climate finance needs that may have attempted to obtain climate loans but ultimately abandoned the pursuit due to high access costs, thus preventing would-be borrowers in poorer nations from accessing climate finance entirely.

3 Transformation of Urban Climate Finance: Incorporating ESG and SDG Frameworks

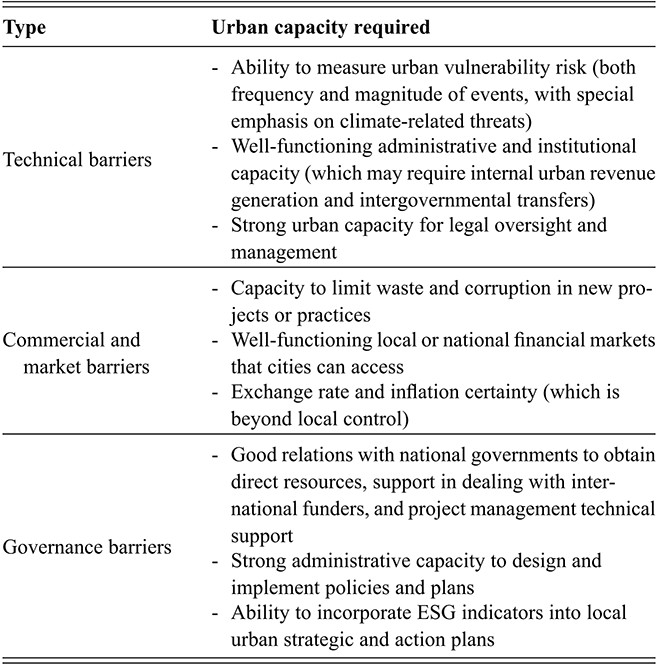

Transforming urban climate finance requires the incorporation of global frameworks and standards at the city level. These standards and frameworks include the ESG framework, the SDGs, NbS, and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (Sendai Framework).

3.1 ESG Accounting

Through the ESG framework, nonfinancial risks, or risks that corporations face that are not directly tied to finances such as damage from extreme climate events, are getting increased attention from nations, financial institutions, investors, and other actors at all levels of the global economic system. The importance of such risks was first reflected in the Global Risk Report published by the World Economic Forum in 2006 (WEF, 2006). On the local level, cities and regions are less likely than nations or multinational institutions to have capacity to evaluate nonfinancial risks in the form of ESG reporting. Nonetheless, they are actively promoting ESG-oriented responses in the following areas: preparing climate- and sustainability-related strategic plans; disclosing key nonfinancial risks and promoting opportunities; and implementing innovative solutions (e.g., issuing green bonds, implementing planting mangroves to reduce risk of coastal flooding, and pursuing debt-for-climate swaps).Footnote 8 They are also exchanging best available practices (e.g., learning how to prepare bankable projects).

Since climate change is already causing disruption and damage in urban areas, cities need the capacity to respond, recover, and rebuild. To develop and maintain a capacity for resilience in the face of ongoing climate change, public and private economic actors on the city level will have to adopt a comprehensive approach to address these threats and transform them into opportunities (Schwarze et al., 2018).

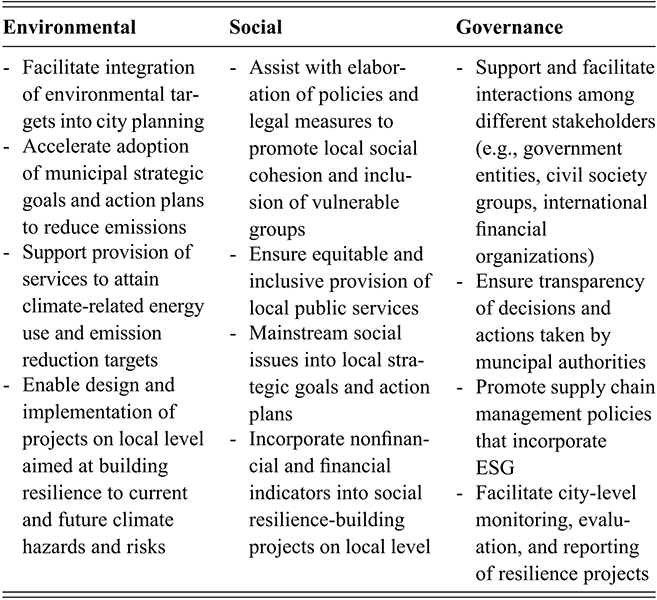

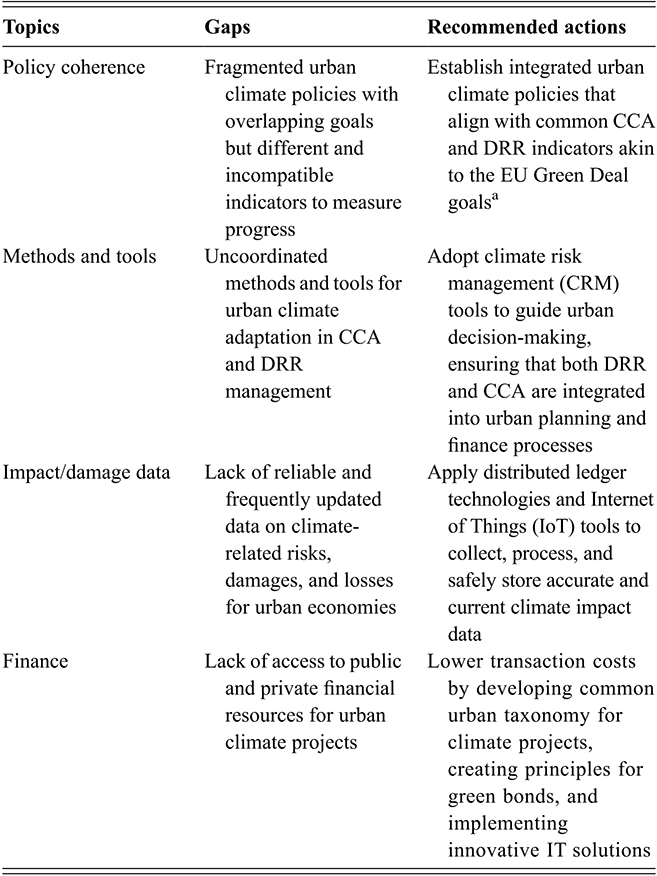

ESG provides one such approach, offering a wide range of opportunities for cities. Some relate to the concrete justification for long-term development planning. In other cases, the nonfinancial impacts (i.e., benefits and costs) associated with project proposals pursuing climate and sustainable finance need to be identified and quantified. Overall, the major benefit of the ESG approach for cities is the development of systematic approaches to dealing with nonfinancial risks and opportunities and in identifying the value generated as a result (Table 1).

Table 1 ESG opportunities for urban resilience

| Environmental | Social | Governance |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Over the last few years, there has been considerable pushback, most notably from the political right, on ESG investing. As climate change and diversity, equity, and inclusion policies have become increasingly politicized in the US, corporations annual shareholder meetings have become platforms for right-leaning activists, claiming that ESG policies undermine profit-driven business interests (Crews, Reference Crews2023; Crumley, Reference Crumley2024). In the US, the number of anti-ESG proposals quadrupled from 23 in 2021 to 112 in 2024 (The Conference Board, 2025). This growing wave of opposition highlights the intensifying debate over the role of ESG in business strategy. Despite significant backlash, 2024 has shown increased support for ESG proposals, reversing the consecutive decline from 2021 to 2023 in the US (ISS-Corporate, 2024).

3.2 Connecting ESG with the SDGs

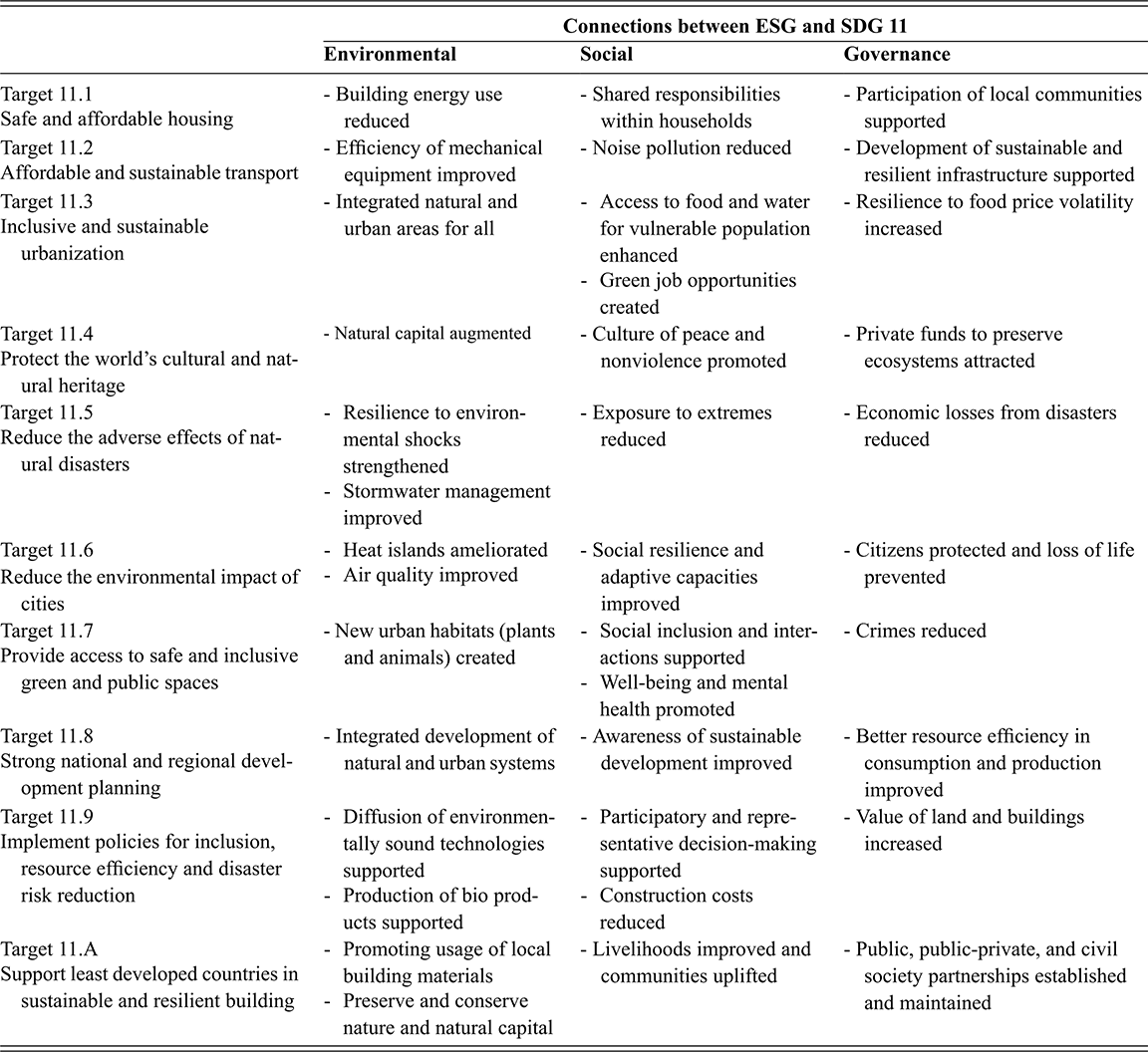

The use of ESG principles helps cities to achieve the SDGs by incorporating resilience into non-financial risk calculations (see Table 2). The ESG framework generates a basis for evaluating city actions to reduce related risks and to advance guidance for how the benefits can be incorporated into reports and financial results for cities.

Further, the ESG approach can facilitate the measurement of financial and nonfinancial risk reduction by different economic agents at the municipal level. One strategy for following the ESG framework in cities is by restoring and preserving natural capital through nature-based solutions (Frantzeskaki & McPhearson, Reference Frantzeskaki and McPhearson2022; Kauark-Fontes et al., Reference Kauark-Fontes, Marchetti and Salbitano2023). Thus, it can provide a bridge between the SDGs and projects pursuing NbS in cities, demonstrating how a project’s environmental, social, and governance components can contribute to improved resilience and more sustainable conditions for urban economic development.

Table 2 Connections between ESG principles and SDG 11

| Connections between ESG and SDG 11 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Social | Governance | |

| - Building energy use reduced | - Shared responsibilities within households | - Participation of local communities supported |

| - Efficiency of mechanical equipment improved | - Noise pollution reduced | - Development of sustainable and resilient infrastructure supported |

| - Integrated natural and urban areas for all |

| - Resilience to food price volatility increased |

| - Natural capital augmented | - Culture of peace and nonviolence promoted | - Private funds to preserve ecosystems attracted |

|

| - Exposure to extremes reduced | - Economic losses from disasters reduced |

| Target 11.6 Reduce the environmental impact of cities |

| - Social resilience and adaptive capacities improved | - Citizens protected and loss of life prevented |

| - New urban habitats (plants and animals) created |

| - Crimes reduced |

| - Integrated development of natural and urban systems | - Awareness of sustainable development improved | - Better resource efficiency in consumption and production improved |

|

|

| - Value of land and buildings increased |

|

| - Livelihoods improved and communities uplifted | - Public, public-private, and civil society partnerships established and maintained |

4 Standards and Reporting: The Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures and the Carbon Disclosure Project

Disclosure of climate-related information by cities is increasingly becoming a requirement, since investors impose higher costs on municipalities that they perceive have greater exposure to climate risks (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Yapp and Mackay2020). Investors need to consider and estimate the costs of different types of project risks, ranging from external threats through internal management capacities to action-specific impacts on the ability of the project operator to fulfill financial commitments. Material risks emerging from climate change may impact city operations and assets, as well as municipal financial health (Georgious, Reference Georgious2019). Evidence has emerged of the heightened willingness and capability of cities to incorporate and disclose climate risks. Since such disclosures demonstrate cities’ responsiveness to capital markets’ expectations and signal sustainability leadership to potential investors, public-sector leaders have noted the significance of transparency on climate-related issues (Georgious, Reference Georgious2019).

4.1 Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD)

Established in 2015 by the G20 and the Financial Stability Board, the TCFD framework has become an important tool for city governments to formulate their climate reporting (Figure 6). The TCFD recommendations were initially developed by the private sector as a standard for the climate risk disclosures individual firms should be expected to make to potential investors. Cities, recognizing that potential funders would demand the same sort of data, are increasingly adopting the disclosure standards for their own internal decision-making and external reporting. The TCFD recommendations for firms have been reformulated into specific disclosure standards and, as of 2024, are managed and administered by the International Sustainability Standards Board. The Board is the global entity responsible for developing standards for a baseline of sustainability disclosue (IFRS, 2023).

Figure 6 Core elements of recommended climate-related financial disclosures.

Figure 6Long description

On the left side is a diagram of four circles, each inside the last one. From outermost to innermost, they are labeled: Governance, Strategy, Risk Management, and Metrics and Targets. The Accompanying text reads as follows. Governance: Organizational oversight around climate-related risks and opportunities. Strategy: Overall planning for actual and potential impacts and resilience. Risk Management: Specific processes to identify, assess, and respond. Metrics and Targets: Goals and indicators used to evaluation effectiveness.

4.2 Carbon Disclosure Project

Established in 2000, the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) is the most developed initiative to support the disclosure of nonfinancial risks. Jointly with Local Governments for Sustainability (ICLEI), it serves as a broad environmental disclosure organization, providing an overview of ESG metrics for companies, nations, provinces, states, and regions, as well as for over 1,000 cities globally (CDP, 2024; CDP, 2025). A different initiative, established in 2008 specifically by and for cities, is the Covenant of Mayors (transformed into the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy [GCoM] in 2016), which unites over 12,000 cities and local governments to support the elaboration of city plans for climate change mitigation and adaptation regarding ESG considerations (GCoM, 2023).

However, due to limited capacities, local authorities are not always able to provide the data on projects needed to pursue funding from investors (UNFCCC, 2019). To bridge this gap, the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group offers technical assistance for incorporating cities’ sustainability priorities into bankable investment proposals that fit into the ESG framework and expectations of financial institutions (C40, 2023). The Global Covenant of Mayors has also aligned with the City Climate Finance Gap Fund to provide technical assistance for project development and funding applications specifically for municipalities in the Global South (World Bank Group, 2024).

A CDP review of cities that participate in its reporting programs provides evidence of the importance of data collection for pursuit of financing. In 2024, CDP found that 611 cities reported climate and environmental data using the CDP-ICLEI Unified Reporting System, representing a 23 percent increase since 2023 (CDP, 2024). Participation is not limited to cities in more affluent countries, with 34 cities in Africa and 293 in Latin America reporting their efforts, as well as close to 50 from Asia outside China and Japan. Over 40 percent of the reporting cities are in the Global South (CDP, 2021).

Climate mitigation action planning starts with the establishment of a baseline, which is typically a greenhouse gas emissions inventory for the city. However, only 544 of the cities reporting to CDP had such inventories in 2020. Of them, only 399 had climate action plans, that is, a formal document that can enable greater access to external funding. Even fewer cities incorporated their climate plans into their overall strategic planning framework. Yet such integration of climate is key to identifying both prospects of intervention and sources of project funding.Footnote 9 CDP data show that cities incorporating sustainability issues into their master plans were between two and two and half times more likely to identify opportunities for climate action, including creation of new businesses and garnering of additional funding (CDP, 2021).

Beyond focusing on the economics of sustainability, CDP also found that cities citing the social and governmental co-benefits of their proposed climate projects – the other legs of the triple bottom lineFootnote 10 – were two and a half times more likely to attract project finance than those that did not (CDP, 2022). As a complementary framework to other planning, the TCFD – and similar reporting protocols that include measurement of co-benefits – pave the way in quantifying climate-related information in financial terms to identify infrastructure investment needs for green projects and enhance cities’ access to national government and other sources of external funding (Georgious, Reference Georgious2019).

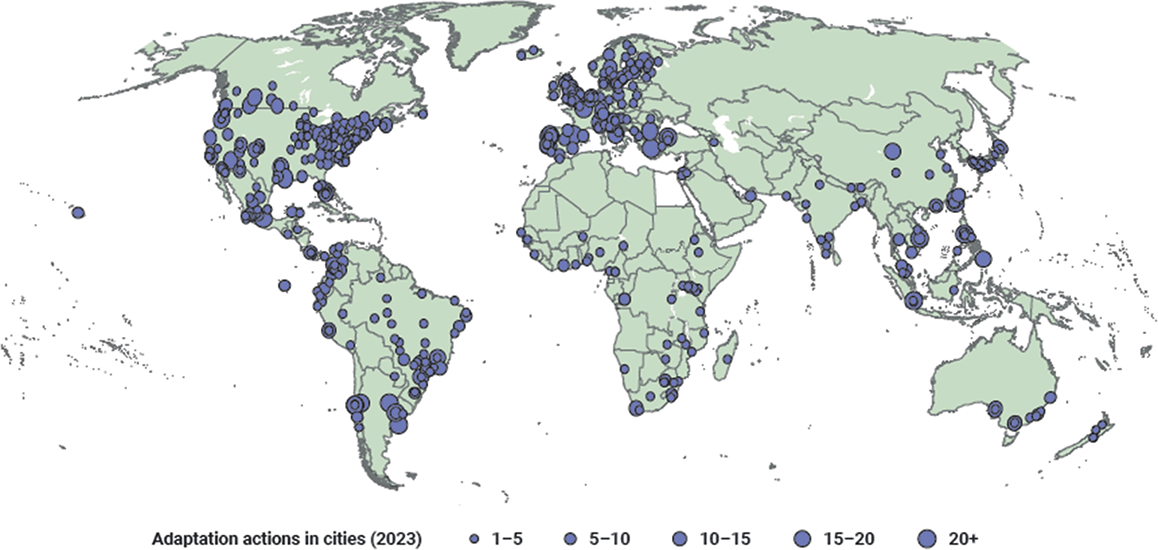

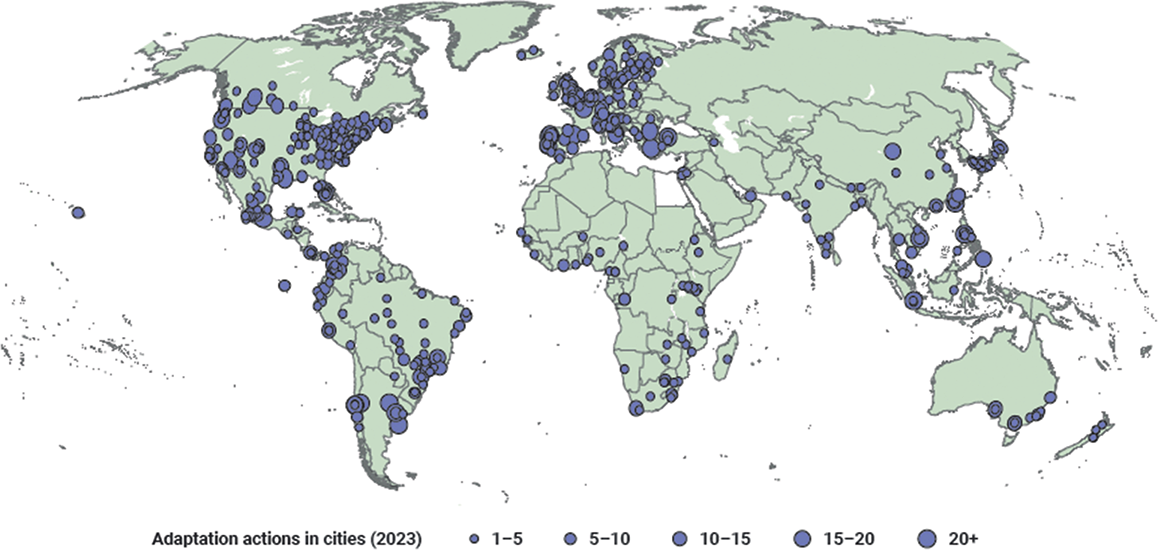

4.3 Examples of Multi-City Reporting

Figure 7 presents the distribution of self-reporting cities globally, as well as the number of adaptation actions reported, as collated by UNEP. The European Union offers an example of international collaboration in promoting and monitoring city responses to climate change. The European Commission, working with GCoM, does not just collect data through its international MyCovenant reporting platform but offers cities capacity building, technical assistance, sharing of best practices, and peer-learning opportunities. The objective of the collaboration initiative is to provide participating cities with information on alternative practices and tools to enable decision-makers in cities of any size to identify priority sectors, set emission reduction targets and adaptation goals, and plan relevant actions (European Commission Joint Research Centre, 2022).

Figure 7 Distribution of self-reporting cities and number of adaptation actions reported per city.

Canada, a wealthy country with low population density, has responded to the need for better tracking of climate responses. The country had annual insured climate-related losses of over Can$1 billion between 2014 and 2019, with payouts in 2018 reaching nearly Can$2 billion. The unexpected massive fires in the spring and summer of 2023 resulted in even higher costs. Many Canadian cities now include municipal climate risk disclosure in short- and long-term financial planning, operational budgets, and capital investment (Case Study 2). Canada has long been promoting municipal carbon accounting and sustainability measurement along with policy development in pursuit of urban climate response. It has the financial resources and advanced management systems that many nations lack. However, it is far from unique. Municipal accounting efforts have been growing across the globe, with positive impacts on cities’ capacity to attract funding for projects (WRI, 2023; Yin et al., Reference Yin, Sharifi, Liqiao and Jinyu2022), although much more needs to be done.

In response to the growing costs and risks of climate change, over 650 Canadian municipalities declared a climate emergency in 2024 due to unprecedented wildfires and storms, and heightened their adaptation efforts (MacDonald et al., Reference MacDonald, Zhou, Telfer, Clarke, Meaney, Giordano, Linton, Tanguay, Tozer, ElAlfy, Ordonez-Ponce and Talbot2024). Through a variety of voluntary platforms, cities across Canada currently report climate change-related information, including GHG emissions. The voluntary platforms align with the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) framework.

Many medium- and larger-sized Canadian cities report using a Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) standard that is based on the internationally recognized GHG Protocol for Cities (GHG Protocol, 2022). Cities use CDP scores to drive investment and procurement decisions towards a zero-carbon sustainable and resilient economy.

Guided by TCFD standards, Toronto included climate-related disclosure in its 2024 Annual Financial Report, along with an unaudited note about GHG emissions targets and reporting in its consolidated financial statements (City of Toronto, 2024). With the application of TCFD, the city mapped public climate-risk policies and centralized them into a single document. This demonstrated the maturity of the city’s governance related to climate change and established a basis for the assessment of financial risks, as well as the cost savings associated with climate risk management (Georgious, Reference Georgious2019). Those data, in turn, provide an empirical financial basis for funding requests and reporting to support both GHG reduction and resilience strategies and action plans.