Introduction

In August 2019, the Burundian legislature imposed ethnic and gender quotas on the composition of the Burundi Constitutional Court.Footnote 1 This reform was in line with earlier institutional reforms, but was at the same time surprising. Burundi is arguably the most consociational polity on the African continent, and ethnic power-sharing has been at the heart of the negotiated settlement of the civil war and of recurrent cycles of deadly ethnic violence.Footnote 2 The country’s transition from armed conflict to peace was fundamentally based on the institutional accommodation of its ethnic segmentation. Seen from that perspective, regulating the composition of the Constitutional Court and transforming it into what appears to be a “power-sharing” court seems a logical component of a wider process of institutional design. Nonetheless, the reform also raises a number of questions regarding its timing, scope and political expediency. Why did it take almost 15 years after the first post-conflict elections in 2005 to extend ethnic quotas from the legislative and executive branches and the security sector to the judiciary and the Constitutional Court? Did the reform of the Constitutional Court merely affect its composition or also alter its powers and decision-making rules, transforming it into a different type of court? Even more puzzling, why was it desirable for the government to introduce ethnic quotas for the Constitutional Court when in June 2018, barely one year earlier, it had introduced a constitutional sunset clause foreshadowing the potential removal of ethnic quotas from Burundi’s constitutional design? At the same time, gender quotas were introduced for the composition of the judiciary and the Constitutional Court; this novelty followed the use of gender quotas for other institutions (including the government and the two chambers of Parliament). Their introduction is also surprising and remarkable, as judicial gender quotas have been problematized based on merit and the principle of judicial independence.Footnote 3 So far, only a handful of countries have followed Ecuador, which was the first country to adopt a judicial gender quota, in 1997.Footnote 4

This case study on Burundi’s Constitutional Court is idiographic and instrumental, and seeks to inform theory and enrich the scholarship on the use of quotas in the judiciary. The research question that guides this study is: What is the function of identity-related quotas in the Burundi Constitutional Court? In combination with a review of the (rather limited) literature on identity-based criteria for the staffing of judiciaries, our empirical analysis of the history, functioning and case law of the Burundi Constitutional Court allows us to develop a typology of courts in countries with ethnic, gender or other identity-related quotas. Our analysis shows that the Burundi Constitutional Court combines characteristics of four types of courts: reflective courts, affirmative action courts, position-sharing courts and – counterintuitively, to a minor extent – power-sharing courts. For each of these types of court, we analyse the identity-based quotas that regulate their composition in light of their societal context, function, status and decision-making rules. We also look at how the four types of court handle concerns regarding judicial independence, which their quota-based composition may give rise to. Beyond its contribution to the legal and political scholarship on Burundi, our article hosts an encounter between three strands of literature: literature interested in affirmative action and political representation, scholarship that studies constitutional design in segmented societies, and literature that analyses the link between power-sharing and conflict resolution.

The article proceeds as follows: a first section sketches the context of our case study, showing how the institutional accommodation of ethnicity was a crucial stepping stone towards conflict settlement. The next section introduces Burundi’s Constitutional Court, focusing on its turbulent history and the ethnic and gender dimensions of its composition. Finally, to answer the central question, the article develops a typology of courts with identity-related quotas and applies this to Burundi.

Burundi’s transition from ethnic violence to peace through institutional accommodation of ethnicity

In 1966, four years after its return to independence as a monarchy, Burundi became a single-party republic. During the next 25 years, approximately, there was a major gap between the constitutional silence on the existence and institutional relevance of the ethnic segmentation of society on the one hand and socio-political reality on the other. At the constitutional level and in official political discourse, ethnic amnesia prevailed. With a focus on citizenship, all Burundians were said to make up one ethnic group, an approach that is strikingly similar to the one currently adopted in Rwanda, Burundi’s neighbour with the same ethnic make-up.Footnote 5 On the ground, however, ethnicity (alongside other factors, such as regionalism) was a main driver of political competition, exclusion and mass violence. Political, military, economic and judicial power was concentrated in the hands of the leadership of the Union pour le Progrès National (UPRONA) (Union for National Progress), an exclusively male military elite belonging to the Tutsi demographic minority segment from southern Burundi. This long-standing situation of inequalities was referred to by Hutu movements as Burundi’s version of apartheid.Footnote 6 Like many other African countries, Burundi was also affected by the post-Cold War wind of change. While the 1991 Charter of National Unity – an irrevocable “supra-constitutional” pact, according to its own terms – confirmed the central idea of national unity based on citizenship, irrespective of ethnic or regional differences, the 1992 Constitution not only introduced multi-party politics in Burundi but also recognized the need “to take into account the diverse components of the Burundian population”.Footnote 7 This clause applied to the composition of the government, the list of candidates for the National Assembly elections and the leadership of political parties, but – of particular interest here – not the judiciary.Footnote 8 According to the commission of experts that drafted the 1992 Constitution – chaired by Gerard Niyungeko, who later became the first president of the Constitutional Court – the goal of this provision was “not to institutionalize ethnic, regional or other quotas” but to bring together people of different ethnic and regional backgrounds.Footnote 9 With the benefit of hindsight, this was the first step in a long and gradual process of increased institutional accommodation of Burundi’s ethnic segmentation. Throughout this process, gender issues, including constitutional quotas for women, piggybacked on the constitutional recognition of ethnicity.

In October 1993, the assassination of President Melchior Ndadaye (of the Front pour la Démocratie au Burundi (FRODEBU) (Front for Democracy in Burundi)), the first democratically elected president belonging to the Hutu demographic majority segment, four months after his election unleashed a decade of ethnic civil war. A Tutsi-dominated government army fought against Hutu-dominated rebel movements. This armed conflict took a huge toll on civilians on both sides of the ethnic divide. In the capital city of Bujumbura, in a process that was tellingly referred to as “Balkanization”, some of the neighbourhoods that were previously inhabited by Hutu and Tutsi became ethnically separated.Footnote 10 Initially, power-sharing deals failed to produce a cessation of hostilities, but sanctions imposed by neighbouring countries and the more active involvement of international mediators – initially the former President Nyerere of Tanzania, later the former President Mandela of South Africa – led to a breakthrough. Unlike in neighbouring Rwanda, peace in Burundi did not result from a military victory. A series of negotiated settlements, particularly the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement (APRA) of August 2000 and the General Cease-Fire Agreement of November 2003 with the rebel movement Conseil National pour la Défense de la Démocratie – Forces pour la Défense de la Démocratie (CNDD-FDD) (National Council for the Defence of Democracy – Forces for the Defence of Democracy), ended the armed conflict. The cornerstone of the negotiated peace was the ethnic power-sharing arrangements that affected almost the entire institutional landscape of the newly designed Burundian state. Burundian women’s organizations, in collaboration with an international network of women’s rights advocates, skilfully used the Arusha peace process and the subsequent negotiations as a window of opportunity to put gender concerns on the negotiation table.Footnote 11 According to Nindorera, the 2004 negotiations on a new, post-conflict constitution amounted to a “power-play over quotas”.Footnote 12 Indeed, in 2005, Burundi became the only country on the African continent to constitutionalize ethnic quotas for the composition of the National Assembly (60 per cent Hutu, 40 per cent Tutsi), Senate (Hutu–Tutsi parity), government (maximum 60 per cent Hutu, maximum 40 per cent Tutsi), defence and security institutions (Hutu–Tutsi parity), the staff of state-owned enterprises (maximum 60 per cent Hutu, maximum 40 per cent Tutsi) and municipality administrators (no more than 67 per cent belonging to the same ethnic group), but not for the judiciary.Footnote 13 The quotas guaranteed a representation of the demographic majority Hutu segment, estimated at around 85 per cent of the population and since 1966 largely excluded from senior state positions. At the same time, they guaranteed an “over-representation” of the demographic minority Tutsi segment, estimated to be around 14 per cent of the population who, also in light of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in neighbouring Rwanda, were fearful of a “bare majority” rule that might constitute an existential threat.Footnote 14 These quotas were an essential part of a highly consociational post-conflict reconfiguration of the Burundi state.Footnote 15 Gender quotas (a 30 per cent guaranteed representation of women) were introduced for the National Assembly, Senate and government, but not for the other above-mentioned institutions.

While Burundi was initially showcased as an example of successful peacebuilding with a strong international footprint, including the presence of a United Nations military peacekeeping force, optimism about the country’s transition towards democracy and the rule of law soon waned.Footnote 16 Elections were held in 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2020, gradually resulting in a total state capture by the CNDD-FDD. According to insiders, the CNDD-FDD never successfully transformed into a political party but rather continues to be dominated by an opaque clique of “generals”, all of them male, senior Hutu military leaders from the “maquis” era.Footnote 17 While Burundi has not experienced major ethnic violence since the first post-conflict elections, a remarkable achievement in itself, its democratic performance, according to Freedom House, worsened from “partly free” in 2005 to “not free” since 2015. In 2015, for the first time in its postcolonial history, Burundi experienced mass demonstrations against the incumbent President Nkurunziza’s third-term ambitions; the protests culminated in a failed coup d’état attempt, followed by the violent repression of suspected opponents.Footnote 18 Aid sanctions were imposed by the European Union in 2016, and in October 2017, the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court opened an investigation. A new constitution was adopted by referendum in 2018; presidential elections were then held in 2020, won by Evariste Ndayishimiye (CNDD-FDD, Hutu). The EU sanctions were lifted in February 2022, because, according to the EU, the elections “opened a new window of hope for the population of Burundi”.Footnote 19

As far as the institutional accommodation of ethnicity is concerned, the 2018 Constitution largely endorsed the ethnic and gender quotas arrangement of the 2005 Constitution. However, four changes are worth mentioning. First, the national intelligence service is no longer considered a security sector institution alongside the army and the police, so ethnic parity no longer applies to its composition.Footnote 20 Second, the absolute-majority rule for the adoption of ordinary laws (instead of the two-thirds qualified majority required by the 2005 Constitution) has watered down the political impact of the guaranteed 40 per cent Tutsi presence in the National Assembly.Footnote 21 Third, ethnic quotas (maximum 60 per cent Hutu, maximum 40 per cent Tutsi) and gender quotas (minimum 30 per cent women) were extended to the judiciary, a remarkable novelty in Burundi’s institutionalization of ethnicity and gender.Footnote 22 The introduction of these two quotas was motivated by the recommendations emerging from a high-level national meeting on the judiciary – a sector traditionally controlled by Tutsi – held in August 2013. According to some of the Hutu participants,Footnote 23 it had become clear that 77 per cent of judges and prosecutors continued to be Tutsi.Footnote 24 Seen from that angle, almost a decade after the election of a Hutu president, quotas were needed to remedy the long-standing exclusion of Hutu as well as women from the judiciary. Finally, the 2018 Constitution introduced a soft sunset clause for the use of ethnic quotas by requiring the Senate, within five years, to evaluate the quotas applicable to the legislative, executive and judicial branches, “in order to put an end to or extend the ethnic quota system”.Footnote 25 The clause does not cover gender quotas.

The Senate launched its evaluation in July 2023; at that time, it was composed of 36 elected senators, including 16 women (44 per cent), and 3 co-opted Twa senators representing the Twa minority. It is worth noting that although half of the senators were Hutu and the other half were Tutsi, most of them (34 out of 36) were members of the ruling CNDD-FDD party. Methodologically and procedurally, the evaluation lacked clarity.Footnote 26 Public hearings were held with stakeholders in all provinces; in addition, national-level meetings were held with representatives of political parties, non-governmental organizations, judicial staff, religious groups, etc. In December 2023, the Senate submitted its report and recommendations to President Ndayishimiye. The report, which was not made public, concludes that some 48 per cent of interlocutors were in favour of maintaining the ethnic quotas, while 52 per cent were in favour of removing them from the Constitution.Footnote 27 Its recommendations were rather open-ended, without clearly favouring an end to or a continuation of the quotas in the long run. The Senate recommended inter alia that more analysis was needed, that the Twa minority should be better protected and that merit should prevail over ethnic identity when attributing positions, but also that more time is needed to heal old wounds before removing the ethnic quotas. It concluded that ethnic quotas are, in the short term, to be maintained in the Constitution, pending preparation of the people’s minds. At the same time, the report insisted that the Burundian people should also be represented based on gender and other characteristics, such as disability and age, in all government bodies. At the time of writing, President Ndayishimiye has not given any indication of the conclusions he may draw from the Senate’s evaluation. Also in December 2023, the Senate discussed a report submitted by its “regular” commission in charge of monitoring compliance with constitutional quotas.Footnote 28 The commission reported that 50.13 per cent of all judges and prosecutors are Hutu, while 49.8 per cent are Tutsi. It concluded that the constitutional quotas were not (yet) respected and recommended that the quotas be kept in mind on the occasion of future recruitments.

The Burundi Constitutional Court

Burundi’s Constitutional Court was first established under the 1992 Constitution. This coincided with the explicit incorporation of international human rights standards as part of Burundi’s constitutional law, the constitutional recognition of multi-partyism and the constitutional independence of the judicial branch. The Court was designed as a cornerstone of protection of the rule of law. Among its main powers, it was in charge of verifying the constitutionality of laws and decrees, and it was also charged with interpreting the Constitution. Furthermore, it verified the validity of elections, played a role in electoral dispute settlements and proclaimed results. From its early days, individual and legal persons used the Court, inter alia to successfully challenge a new media law and new amnesty legislation on human rights grounds. However, rather than being seen as a judicial body in charge of human rights protection, the Court was soon perceived (and indeed used) as a counter-majoritarian judicial instrument in the hands of the political opposition, in particular after the electoral victory of Ndadaye and his FRODEBU party. This experience sharply contrasted with a judicial culture that had prevailed for several decades and was nicely reflected in the 1974 Constitution: “[J]udges are subjected, when exercising their functions, to the authority of the law, the options of the party and the revolutionary conception of law.”Footnote 29 In other words, the (single) party UPRONA prevailed over the judiciary.

The turbulent history of the new court, including its de facto dissolution in January 1994, mirrored the highly unstable political context in which it operated. Less than two years after the first bench was appointed in March 1992, the Court fell apart, not coincidentally breaking up along ethnic lines. In January 1994, the two Hutu members of the Court resigned. Some days later, the five remaining members, all of them Tutsi, were dismissed by the government. The institutional crisis was occasioned by the Court’s handling of a constitutional amendment regarding the modality of the presidential election.Footnote 30 On several other occasions, the Constitutional Court was the subject of major controversy, although not for ethnicity reasons. For instance, in June 2008, at the request of the CNDD-FDD secretary general via the speaker of the National Assembly, the Court “dismissed” 22 members of Parliament who had resigned or been expelled from the CNDD-FDD.Footnote 31 Even more controversial was the Court’s interpretation, in May 2015, of the 2005 Constitution that allowed the incumbent President Nkurunziza to run for a third term.Footnote 32 The ruling constituted a dramatic blow to the perceived independence and legitimacy of the Court.

For the purpose of our analysis, we now focus on the composition of the Court and in particular the ethnic and gender identity of its members. First, we take a look at the organic legislation regulating the composition (and functioning) of the Court; then we will present its actual composition since its establishment in 1992. Between 1992 and 2001, neither the Constitution nor the organic laws on the Court contained any reference to the ethnic or gender dimension of its composition.Footnote 33 This changed to some extent after the APRA was signed in August 2000. Both the 2001 Transitional Constitution and the 2005 Constitution contained a general requirement that “the judiciary is structured in order for its composition to reflect the whole population. Recruitment and appointment procedures of the judiciary must consider the need to improve an ethnic and gender balance.”Footnote 34 While neither the sections of both constitutions dealing with the Constitutional Court nor the organic legislation adopted on that basis contained a similar reference to ethnicity, gender and the composition of the Court, the general requirement logically also applied to it. As mentioned, the 2018 Constitution marked another step in the institutionalization of ethnicity and gender as part of the judicial design. While, again, the section on the Constitutional Court in the 2018 Constitution remains silent on ethnicity or gender, the general requirement for the judiciary to reflect a regional, ethnic and gender balance is now specified, adding that judges and prosecutors “include a maximum of 60% Hutu and a maximum of 40% Tutsi. A minimum of 30% women is guaranteed.”Footnote 35

The Constitution does not specify how this provision should be interpreted. Do the quotas apply to all judges and prosecutors taken together, or at the level of every individual court and tribunal? As for the Constitutional Court, its organic law of August 2019 included an explicit reference stating that its composition “is done in accordance with the constitutional equilibria”.Footnote 36 The 2018 Constitution stipulated that the members of the Court remain in office until the 2020 elections.Footnote 37 Hence it was not until December 2020 that new members of the Constitutional Court were appointed by the president. Remarkably, the presidential decree appointing the new members only mentions their gender, not their ethnic identity or region of origin.Footnote 38 However, when introducing the nominees to the Senate (in charge of approving the appointment of the members of the Court),Footnote 39 the Minister of Justice did also mention these two points.Footnote 40 Even more remarkably, the newly appointed court was clearly not composed in accordance with the constitutional gender quotas: only one woman was appointed, which amounts to approximately 14.2 per cent, rather than 30 per cent as required by the 2018 Constitution and the 2019 Organic Law read together. When in December 2023 two non-permanent members were replaced, the “error” was not corrected: two men (one Hutu, one Tutsi) were replaced by two other men (one Hutu, one Tutsi).Footnote 41 With the appointment of three Tutsi members out of seven, ie 42.8 per cent, the composition does meet – as closely as mathematically possible – the ethnic quotas.

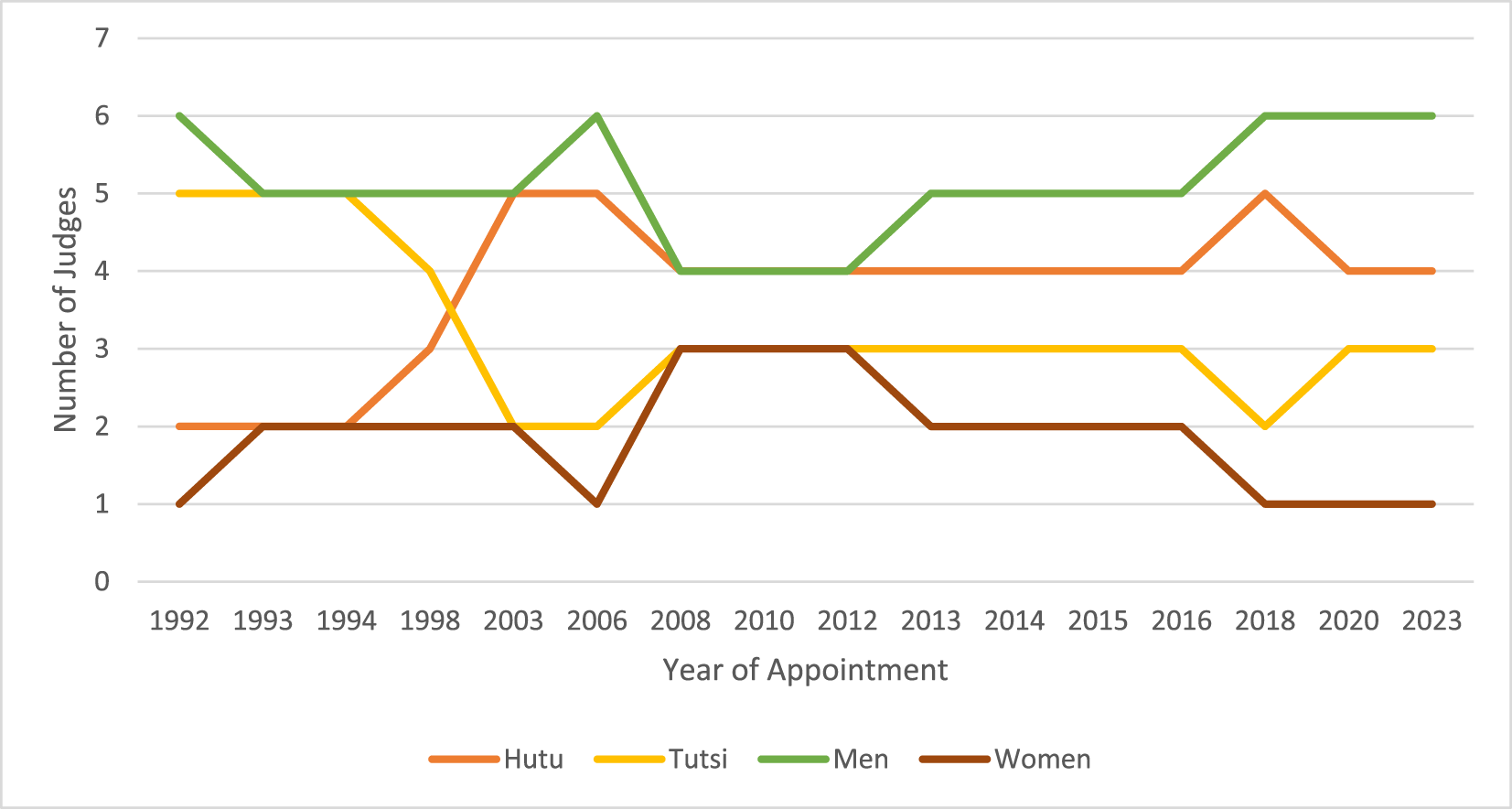

This begs the question of whether the 2018 Constitution and the 2019 Organic Law on the Court meaningfully impacted the Court’s composition in terms of the ethnic and / or gender identity of its members. As Figure 1 shows, the composition of Burundi’s Constitutional Court was never mono-ethnic; throughout its history, at least two members of the Court have been from the other ethnic identity segment. It also shows that, except for 1993 and 1994, the ethnic identity of the majority of court judges mirrors that of the president of the republic.Footnote 42 When the first bench was composed in 1992, five Tutsi judges and two Hutu judges were appointed by President Pierre Buyoya (Tutsi). In 1993 (from July) and 1994, the president was Hutu. Although in August 1993, three judges were replaced, the same ethnic composition was maintained (five Hutu and two Tutsi). The most reasonable explanation is that at the time, President Ndadaye (Hutu) and his FRODEBU party had not yet realized the potential political impact of the Court, and in addition, there was a shortage of Hutu with a legal degree, who were instead appointed in other positions considered more important. Buyoya, after returning to power through a coup d’état in 1996, appointed four Tutsi judges and three Hutu judges in June 1998. In 2003, Domitien Ndayizeye (Hutu) replaced Buyoya for the second part of the transition, as agreed in the APRA. Since then, the president and the majority of Constitutional Court judges have always been Hutu. However, the number of Tutsi judges (mostly three, at some point two, out of seven) has always exceeded their presumed demographic weight (14 per cent, which would proportionally amount to one out of seven).

Figure 1. Ethnic and gender composition of the Constitutional Court.

Since its establishment, the Court’s bench has always comprised men and women but in different proportions. Starting with one female member in 1992, the number of women reached a “peak” with three judges from 2008 to 2012, before it gradually decreased, returning to one from 2018 onwards. This random variation is hard to explain; as mentioned, under the 2019 Law on the Court at least two women should have been appointed in 2020. Finally, it is worth saying that the Court was twice presided over by a woman: Domitille Barancira from 1998 to 2006 and Christine Nzeyimana from 2007 to 2013.

We conclude that the 2018 Constitution, which institutionalized ethnicity and gender as part of the judicial design, has had hardly any real-life impact on the ethnic and gender composition of the Constitutional Court. What insight does this provide about the rationale for introducing the ethnic and gender quotas requirement, and more importantly, what does it tell us about the nature of the Burundi Constitutional Court? Does it qualify as a typical power-sharing court similar to constitutional courts in other consociational settings like Belgium and Bosnia–Herzegovina – as one might expect, given the overall institutional environment following the signing of the APRA and the 2005 Constitution? Or should we see ethnic quotas merely as a variation on gender quotas, to reflect society in the composition of the Court or to make up for historical under-representation?

A typology of courts with quotas

In this section, we develop a typology of courts, using Burundi as a case study and referencing the wider literature. This typology concerns courts – in general, or limited to apex courts – whose composition is determined by ethnic, gender or other identity-related quotas. We distinguish four types: reflective courts, affirmative action courts, power-sharing courts and position-sharing courts. We compare these different types from six analytical perspectives: (i) the social and historical context in which the court operates, (ii) the function of the quotas, (iii) the status of the court, (iv) the modalities of the composition of the court, (v) the court’s decision-making rules, and (vi) a judicial independence perspective (see Table 1). Importantly, the last two types only refer to quotas related to cleavages between national groups. This means that ethnic quotas can refer to any of these four types, while gender quotas are in principle only indicative of the first two.

Table 1. Typology of courts with quotas

In what follows, we first identify types concerned with “identitarian representativeness”. The use of quotas to this effect is very slowly gaining ground. Although theoretically relevant for courts at all levels of the judicial pyramid, in practice, where they apply, they are usually limited to apex courts. For example, in Belgium, the law imposes that the Constitutional Court is composed of an equal number of Dutch- and French-speaking judges, with at least one-third of judges of each gender.Footnote 43 Kumm finds that quotas contribute to the legitimacy of a court in two cases: “to overcome historical patterns of discrimination and exclusion” and to make sure that “parties can plausibly believe that their point of view will be appropriately understood and assessed”.Footnote 44 We argue that these words describe two different types of court, with different purposes, ways of dealing with the judicial independence obstacle, and legal regimes. We therefore distinguish between reflective courts and affirmative action courts, two types that may apply to courts at all levels of the judicial hierarchy. A reflective judiciary is one that “fairly reflects societal diversity in terms of race, gender, religion, [and] nationality” to send signals of trustworthiness.Footnote 45 By contrast, affirmative action courts are more concerned with equal access to the judicial profession.

Next, we distinguish between power-sharing courts and what we call position-sharing courts, a typology that applies to apex courts only. In these cases, the composition of the courts reflects the politically salient cleavages in a divided society. For a power-sharing court, its aim is to contribute to stability in a divided, and therefore fragile, political system. This may also be an effect of position-sharing courts, but their primary function is to contribute to the satisfaction of elite interests and to safeguard the negotiated power equilibrium. In what follows, we discuss these types in more detail. We show how the Burundi case, to a varying extent, fits all four types.

Reflective courts versus affirmative action courts

A reflective judiciary is concerned with substantive representation, a topic that has mainly been discussed in relation to political decision-making bodies. Concerning the judiciary, it is more controversial. On the upside, reflective courts contribute to the court’s trustworthiness; according to Mayer, Davis and Schoorman’s Ability, Benevolence and Integrity (ABI) model, ability, benevolence and integrity are important signals of trustworthiness.Footnote 46 A reflective court signals benevolence, ie the willingness to take into account the parties’ specific needs, which in turn leads to judgments that are better informed (ability) and perceived as more fair (integrity). In this vein, the Canadian Supreme Court argues that its members must be reasonably reflective of the diversity of society, as this “helps to ensure that, in any particular case, the Court can benefit from a range of viewpoints and perspectives. A reasonably reflective court also promotes public confidence in the administration of justice as well as in the appointment process.”Footnote 47 Reflective policies consider the under-representation of specific groups as a structural deficit. Such policies usually address gender gaps, but are not necessarily limited to gender. Regarding electoral gender quotas, it has been argued that women’s rights are unidentified or unformed as a whole, but can be articulated in concrete cases throughout the decision-making procedure through the presence of women.Footnote 48 Applied to the judiciary, the argument holds that women’s perspective on the outcome of judicial decisions can only be secured through the presence of women on the bench. In practice, the results as to whether female judges make a difference are mixed.Footnote 49 In her case study on Ghana, Dawuni shows that women judges promote women’s rights if other conditions are fulfilled, such as laws guaranteeing women’s rights and an enabling socio-cultural climate.Footnote 50 To make a marked difference, a substantial number of women on the bench along with gender sensitization is needed.Footnote 51 This means that the female perspective is essential, also in the absence of practices of discrimination – even if such practices were the initial reason to argue for quotas. It also means that the under-representation of a dominant gender group in society is considered equally problematic, and may lead to the formulation of a neutral gender quota. For example, in Belgium, article 34, paragraph 5, of the Special Law on the Constitutional Court states that “[t]he Court has at least one-third of judges of each gender”.

Under a reflective court model, quotas aim at securing the continual consideration of a group’s interests in judicial outcomes; as a consequence, they do not have to be temporary. In addition, a group is not necessarily represented in proportion to social reality. Instead, it must be sufficiently represented to have a meaningful voice in the decision-making process. Generally, a threshold of 30 per cent is considered sufficient for “critical mass”.Footnote 52 This is exemplified by the Belgian Constitutional Court (a one-third requirement) and the Burundi judiciary (see below).

In the case of affirmative action courts, the concern is not so much trustworthiness but access to the bench. It is not believed that women make a difference, because quotas, under this model, do not address a problem of substantive representation.Footnote 53 Instead, in this model under-representation is considered a problem of access to the judiciary: under-representation of a group may be an indicator of unequal chances of being appointed as a judge. The purpose of any measure under this model is to redress a historical injustice. Consequently, quotas are only acceptable if they are (explicitly or implicitly) temporary: they are no longer justified once a balance is reached. Under the proportionality principle, equal access is balanced against other rights and principles;Footnote 54 therefore weak quotas are preferred over strong quotas, in terms of number and enforcement mechanisms. In reflective and affirmative action courts, decision-making rules are not typically different from other courts without identity-related quotas.

Legal scholars mainly see room for judicial quotas if their purpose is to redress historical patterns of discrimination and exclusion.Footnote 55 The Venice Commission also refers only to this purpose to explain formal quotas in the organization of courts.Footnote 56 Even then, quotas are generally not considered an obvious means to diversify the judiciary, given the principle of judicial independence. Upon closer inspection, it appears that the diversity versus independence argument presents a false dilemma. The main goal of judicial independence is to protect courts from majoritarian capture, to secure objective decision-making based on legal merit alone.Footnote 57 Compared to other courts, both reflective and affirmative action courts enjoy the same safeguards against the influence of political actors. The implicit assumption, however, is that ensuring diversity comes at the expense of expertise, affecting objective – ie legal merit-based – decision-making “ability” in a model of trustworthiness. In reflective politics, this is not necessarily the case, provided that all groups are offered the same opportunities to be trained and build expertise. By making better-informed decisions, a more diverse court can even enhance objective decision-making.

Other rights and freedoms, however, stand in the way of affirmative action courts. Where there is no claim for structural representation, the purpose of redressing historical injustice is only one of the arguments to be balanced against, for example, individuals’ right to have access to a mandate, even if they belong to the dominant group. Therefore quotas are only seen as a last resort, when other efforts to guide under-represented groups towards judicial offices, for example by giving access to legal training or changing the selection method, lead to insufficient results.

Is Burundi illustrative of reflective or affirmative action courts?

Burundi is illustrative of both reflective and affirmative action courts. There are strong indications that reflective politics explain quotas in the Burundi judiciary: the 2005 and the 2018 constitutions both state that “[t]he judiciary is structured in such a way as to reflect in its composition the whole population”.Footnote 58 Both constitutions subsequently require that the procedures of recruitment and appointment in the judicial corps respect ethnic and gender balances, with the 2018 Constitution also referring to regional balance. More broadly, both constitutions require that public administration in general must be “largely representative of the Burundian nation and must reflect the diversity of its components”. Recruitment policy must be based on “the need to ensure a large ethnic, regional and gender representation”.Footnote 59

At the same time, affirmative action quite understandably seems to have played an important role when ethnic and gender quotas were introduced in the judiciary. We have already referred to the historical legacy of discrimination and exclusion of Hutu in the judiciary, in particular at senior levels. This in turn was directly related to long-standing horizontal education inequalities and in particular the historically almost mono-ethnic (Tutsi) staff in the law faculty of the public Université du Burundi.Footnote 60 As for gender, the 2011 Civil Society Monitoring Report regarding UN Security Council Resolution 1325 noted that:

“Progress has been made within the judiciary: 14.8% of the positions are held by women compared to the period before, during which no positions were held by women. The slow progress in this area could be explained by women’s late entry into this field. There is a strong perception in the Burundian culture that law and justice are the exclusive responsibility of men.”Footnote 61

Niyonkuru details how, by September 2020, the representation of women at senior levels of the judiciary had increased to 28.6 per cent, which comes very close to the constitutional 30 per cent requirement.Footnote 62 More broadly, the 2005 and the 2018 constitutions require that public administration in general must not only reflect the diversity of the population, but recruitment policy must also be based on “the need to correct disequilibria” from the past.Footnote 63

Despite their similarities in terms of context and function, gender quotas and ethnic quotas are treated differently in Burundi. Gender quotas refer to women, not men, which is a clear reference to the historical pattern of exclusion of women. Nonetheless, the case can be made that affirmative action has played a bigger role when it comes to ethnic quotas. In terms of the modalities of court composition, the quotas for women show the characteristics of reflective courts: there is a 30 per cent threshold, and no limit. By contrast, the 2018 Constitution assigned the Senate the task of evaluating the ethnic quotas in the executive, legislative and judicial branches, with a view to either ending or continuing this system. So at the same moment when ethnic quotas for the judiciary were introduced, the Constitution announced their possible removal following an evaluation to be held within five years. The open-ended nature of the recommendations put forward by the Senate’s evaluation report is also in line with its findings regarding the ethnic composition of the judiciary: more affirmative action is needed for Hutu to redress their past exclusion. Although they are not supposed to be permanent, removal of the quotas would be premature. Furthermore, in addition to their temporal nature, the ethnic quotas significantly exceed the “classical” threshold of 30 per cent typical of reflective courts; at the same time, they are not proportional to the demographic share of both groups in the population. From the perspective of affirmative action, the 60/40 per cent quotas are also puzzling. If they were mostly (or only) meant to remedy past discrimination against Hutu, why is the Hutu segment (presumably 85 per cent of the population) apportioned a maximum of 60 per cent of the judges and prosecutors? Vice versa, why is the Tutsi segment, historically dominant in the judicial sector, entitled to 40 per cent of the positions, while it presumably makes up 14 per cent of the population? From a pure affirmative action perspective, this is hard to explain. The 60/40 division also applies to the Constitutional Court specifically. Combined with the status of the Court as an apex court, this seems more indicative of a power-sharing court, which we discuss below.

Power-sharing courts versus position-sharing courts

As we conceptualize position-sharing courts as a novel category, we proceed differently here from the first section. Using the above-mentioned analytical entries, we discuss the characteristics of power-sharing courts and position-sharing courts separately.

Power-sharing courts

In terms of their historical and social context, power-sharing courts occur in divided societies. In these societies, salient questions are decided along ethnic lines. As a result, important sub-groups, if not involved in decision-making, risk permanent exclusion. For a long time, it remained under-exposed in the literature on power-sharing that this also applies to courts. Graziadei noticed that, for example, the Bosnian Constitutional Court tends to divide along ethnic lines on ethnically salient questions; he pointed out that as a result, the Court risks losing legitimacy, causing the excluded groups to seek refuge in extra-legal outlets.Footnote 64

The function of power-sharing courts is to decide issues of what Hirschl calls “mega-politics”, ie cases of “utmost political significance that often define and divide whole polities”.Footnote 65 Consociational arrangements in divided polities aim to constrain majoritarian rule to include the views of otherwise excluded sub-groups in the decision-making. As part of that arrangement, the court’s task is one of pacification: to secure stability by enforcing constitutional limitations on majoritarian prerogatives and de-escalating politically salient conflicts between constituent groups in a divided system.Footnote 66 The topics falling under this function are diverse and context-related, ranging from the design of electoral districts to divisive language issues, veto rights of constituent groups in central decision-making bodies, and segmental autonomy.

Power-sharing courts are typically apex courts.Footnote 67 This means that even in the same legal system, quotas in the judiciary and apex courts can have different functions, because power-sharing courts’ task to decide cases of “mega-politics” comes with the expectation that they contribute to stability in a divided and fragile political system. To fulfil their task, these apex courts are composed so as to represent – or even over-represent – the significant ethnic groups. Graziadei sees this as the key requirement for a power-sharing court: “At a minimum, a power-sharing court is an apex court in a power-sharing system, provided that its composition reflects the politically salient cleavages (regional / national / religious / linguistic).”Footnote 68 On this basis, he distinguishes strong and weak power-sharing courts; in the former, the relevant ethnic groups are equally represented.Footnote 69 Examples are the Belgian Constitutional Court, the national judges (alongside three international judges) in the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the regional Administrative Court of Bozen / Bolzano in South Tyrol, Italy.Footnote 70 By contrast, weak power-sharing courts reflect the relevant ethnic groups on a proportional basis, which means that the composition is dominated by the majority nation – for example in Switzerland, North Macedonia or Northern Ireland.Footnote 71

Regardless of the choice for proportional or parity representation, no segment may dominate in the operation of the Court.Footnote 72 Instead, decisions are consensus-based; to ensure this, specific rules guide the decision-making process. Consociational minority vetoes are, however, generally avoided, because the right to a fair trial obliges the court to decide within a reasonable time.Footnote 73 Instead, procedural and organizational rules facilitate consensus-making, for example by preventing decisions from being made in the absence of one segment, prohibiting dissenting opinions or rotating the presidency, which has a tie-breaking vote.

In power-sharing courts, the institutionalization of diversity deviates from the mainstream approach to judicial independence. Instead of protecting the court from political actors, this model seeks to ensure that individual judges act as the representatives of a particular ethnic group that is part of the political power-sharing mechanism.Footnote 74 The presumption that judicial independence is a guarantee for judicial decision-making based on legal merit alone is rejected in the model of power-sharing courts. The literature on judicial politics gives ample evidence that the way judges use their interpretative space when applying constitutional rights and freedoms is determined by their personal characteristics and ideological preferences, as well as by strategic considerations.Footnote 75 In divided societies, the presumption is that the ethnic background of judges is one of the factors that determines their position within this interpretative space.Footnote 76 In this environment, the decisions of a court dominated by judges of one ethnic group will easily be seen as the biased outcomes of a court seeking to further the interests of that group only. The requirement of neutrality, traditionally implied in the principle of judicial independence, now transforms into a requirement of balance. A balanced composition is expected to reach balanced outcomes, able to secure stability and pacification. This is why in power-sharing courts, ethnic quotas are complemented by procedural and organizational rules that stimulate consensus-making. In the absence thereof, the court cannot succeed in ensuring pacification and stability.

Position-sharing courts

Bogaards rightly explains that not all power-sharing agreements amount to consociationalism. All too often, governments of national unity – like those established in Kenya and Zimbabwe in 2008 as a short-term emergency response mechanism to counter widespread post-electoral violence and stop further escalation of ethnic conflict – are classified in the literature as cases of power-sharing and even of consociationalism.Footnote 77 The terms power-sharing and consociationalism have increasingly been used interchangeably. Power-sharing has, however, frequently been primarily used as a war-termination mechanism in the context of a civil war. In those cases, it is used as an essential cornerstone of a wider negotiated settlement which, especially since the early 1990s and the increased involvement of international mediators, has been prioritized over military victories. From such a conflict-settlement perspective, Hartzell and Hoddie argue that to be successful – ie to avoid an early relapse into civil war – power-sharing ideally combines political, economic, territorial and security dimensions.Footnote 78 In all these spheres, positions are granted to fighting elites in order for them to lay down arms. Mediators thus seek to attract elites to strike cake-sharing deals, very often with international donor support in order to turn the deal into a non-zero-sum, win–win situation. The judiciary is usually not an important aspect in those deals, which come about in contexts where the rule of law mostly exists only on paper; in such contexts, it is merely one of the public sectors in which positions (jobs, salaries, benefits, privileges, etc) can be attributed. For elite actors and their interests, prestigious positions in apex courts are most attractive. This is the context in which position-sharing courts may come about.

In this context, the function of position-sharing courts is to contribute to the satisfaction of elite interests and to safeguard the negotiated power equilibrium. Position-sharing apex courts may thus contribute to stabilization. They may also be instrumental in keeping up the appearance of a post-conflict state that adheres to the rule of law, with an apparent system of checks and balances. In that sense, they are power-affirming and, in the short term, a tool for consolidating and legitimizing a fragile equilibrium. Their composition is likely to represent the belligerent groups, with a guaranteed representation of those groups with military nuisance capacity. The quotas for each group are determined by the balance of power at the time the position-sharing agreement came into being. However, rather than acting as an autonomous branch, they are likely to subsequently ride the waves of the shifting political and military balance of power. The duration of the position-sharing court is therefore uncertain and likely to mostly reflect how the balance of power evolves in other spheres (mainly the executive branch and the security sector).

In terms of their decision-making procedures, unlike power-sharing courts, position-sharing courts are, in their organization and operation, not designed to encourage decision-making based on consensus. The requirement of balance is the crucial point that distinguishes power-sharing from position-sharing courts. In the absence of rules that facilitate judicial decision-making based on consensus, ethnic quotas risk decision-making that, rather than seeking stability and pacification for the entire community, mainly serves the vested political interests of the different groups, or the dominant group, in court. As McCulloch has observed, post-conflict power-sharing arrangements risk immobility and elite intransigence.Footnote 79 Position-sharing courts express such developments.

Is Burundi illustrative of power-sharing and / or of position-sharing courts?

In this section, we analyse the case of Burundi’s Constitutional Court using the analytical entries in Table 1.

Context Can the Burundi Constitutional Court be labelled as a power-sharing court or rather as a position-sharing court? Regarding context, the Court fits both types. It operates in a deeply divided society with ethnic power-sharing arrangements, but at the same time it was established (and later removed but re-introduced) in a negotiated post-conflict setting based on a cake-sharing deal between belligerent elites. An important question for our article is whether Burundi was still an ethnically divided society when ethnic quotas for the composition of the Court (and the wider judiciary) were introduced in 2019. The APRA of August 2000 stipulated that all signatory parties agreed that “the conflict is fundamentally political, with extremely important ethnic dimensions”.Footnote 80 The solution put forward was a new, highly consociational institutional blueprint – albeit without segmental autonomy of a federal or non-territorial nature, a classical institutional pillar of consociationalism. At the same time, the peace negotiators designed an “associative” electoral system, with important centripetal features, including the banning of ethnic parties and the use of blocked multi-ethnic electoral lists for National Assembly elections.Footnote 81 Requests by the predominantly Tutsi parties to organize such elections based on two separate electoral colleges – with Hutu candidates being elected by the Hutu electorate and Tutsi candidates by the Tutsi electorate – were rejected for being too divisive and undermining national unity. According to Haysom, the lead adviser to mediator Mandela, the institutional design put forward in the APRA “blunts the ethnic presentation of political choice and can dissipate ethnic hostility generated by raw ethnic mobilization – even though it violates the freedom of association”.Footnote 82

Was the institutional design effective in de-ethnicizing politics in Burundi? On the one hand, as mentioned above, there has been no politically motivated ethnic violence in the country since the first post-conflict general elections in 2005. During electoral campaigns and, more broadly, in public and private media, ethnicity is no longer a major issue. On the other hand, the third-term crisis in 2015 showed that ethnicity can – again – easily be instrumentalized by political elites warning of a possible genocide in the making.Footnote 83 The evaluation of the ethnic quotas conducted by the Senate in 2023 concluded that more time is needed for old wounds to heal. On the same topic, the chairman of the UPRONA party, Olivier Nkurunziza (Tutsi), stated that abolishing ethnic quotas would fuel ethnic exclusion and lead to mono-ethnic appointments.Footnote 84 Quite understandably, on the Tutsi side, the ethnic quotas thus continue to be seen as a minority protection mechanism. From an analytical perspective, however, despite the progress made in surmounting ethnic divisions, contextual factors rather point to the Burundi Constitutional Court being a power-sharing court.

At the same time, Burundi’s transition was essentially based on a cake-sharing deal between elites that merely instrumentalized ethnicity for political gains. Eyewitness accounts of participants at the Arusha peace process documented that access to political positions (and the benefits that come with them in a country where the state is the main source of employment), rather than the interests of the people they supposedly represented, was the main motivation for negotiating parties: in Arusha, “the state became a cake to be shared”.Footnote 85 The Kirundi-language term commonly used for power-sharing is kugabura ibibanza, which rather refers to the sharing of positions. Among citizens, but also among political observers, analysts and actors, Arusha-based power-sharing is even more frequently and more pejoratively referred to as amagaburanyama, literally “meat-sharing”, between elites who used to fight each other and now come together to “eat” power.Footnote 86 Finally, among Burundian and international actors involved in the peace process, there was little or no belief that in the absence of any tradition of the rule of law, and in light of the turbulent history of the Burundi Constitutional Court, the judiciary might be helpful in de-ethnicizing and de-escalating ethnopolitical conflicts.Footnote 87 In other words, in terms of the institutional context, the prerequisites for installing a credible power-sharing court were (logically) perceived to be lacking. In short, looking at context, the Burundi Constitutional Court can be qualified as a position-sharing court.

Function From an analytical functional perspective, the question arises whether, following the establishment of largely consociational institutions in 2005, the Burundi Constitutional Court has played a role in the de-escalation of ethnic conflict. We examined the Court’s case law over time to analyse its behaviour in cases with ethnic implications and assessed whether there might be a correlation between the outcome of a case and the ethnic composition of the Court vis-à-vis the ethnic composition of the political party in power. In other words, do courts with a majority of Hutu judges decide in favour of Hutu applicants, or rather in line with the ethnic identity of the president of the republic? In the same vein, do Tutsi-dominated benches rule in favour of Tutsi applicants or presidents? Applications to the Court and judgments do not refer to the applicants’ ethnic identity. Our “ethnic” analysis of the behaviour of the Court is based on our reading of the facts stated in the judgments and the contextual information that is publicly known. While we might have expected the Court to handle a considerable number of ethnicity-related cases, our analysis reveals that only five ethnically sensitive cases were brought to the Court and that they were primarily related to land issues.Footnote 88 A first conclusion, therefore, is that ethnically divisive issues do not regularly end up at the table of the Court. Land cases are an exception, rather than the rule; in a country where most people are active in subsistence agriculture, land is the most precious resource. On several occasions in the history of Burundi, commissions have been established to handle disputes between returnees (mostly Hutu) and the legal owners or de facto occupants of the land that they left behind (often Tutsi). For our analysis, we also looked at the three “older” cases (ie before the APRA and the 2005 Constitution), enabling us to compare two different eras.

In RCCB 31 (25 July 1994), 34 and 35 (both 26 July 1994), the applicants challenged article 6 of the Law on the Commission for the Repatriation and Reintegration of Refugees.Footnote 89 Subsidiarily, they requested the Court – with a bench composed of four Tutsi judges and one Hutu judge – to declare the Commission’s decision by which they had been expelled from their lands null and void.Footnote 90 Article 6 under review stipulated that the Commission’s decisions had the same legal value as final judicial decisions, excluding a possible appeal before regular courts. The applicants argued that the provision was inconsistent with article 140, paragraph 1, of the 1992 Constitution, which provided that judicial power was to be exercised by courts only. They stressed that they could not trust the Commission because, as an administrative institution depending on the government, it lacked the independence that courts generally enjoy.Footnote 91 The Court found the request grounded, and the provision under review was declared unconstitutional; moreover, the decision to expel them from their land was retroactively declared null and void.Footnote 92 From a procedural perspective, it is worth mentioning that only RCCB 31 was judged on its merits. Considering that the other two cases (RCCB 34 and 35) were similar to RCCB 31 in all respects, the Court held that there was no need to decide them on their merits; it only stated that the decision in RCCB 31 applied to all the cases pending before the Commission for the Repatriation and Reintegration of Refugees.Footnote 93 RCCB 34 and RCCB 35 were then dismissed.

In RCCB 256 (14 February 2012) and 274 (22 November 2013), applicants requested the Court to declare article 19 of the Law on the Commission of Land and Other Properties unconstitutional.Footnote 94 The applicants referred to RCCB 3, which determined for the first time three criteria to test the interest of an individual to apply to the Court, namely a personal, current and legally protected interest. As their properties had been attributed to other persons by the Commission of Land and Other Properties, the applicants argued that they had a personal and current interest in applying to the Court; for legal protection, they referred to article 36 of the 2005 Constitution, which guarantees the property right.Footnote 95 Based on its jurisprudence in RCCB 3 as invoked by the applicants, the Court acknowledged that the applicants had a personal and current interest; however, it held that the interest was not legally protected because it was contested by the other party to the dispute. The requests were then declared inadmissible.Footnote 96 In our view, the reasoning of the Court in these cases lacks substance and is contradictory: how could the applicants justify their interest in seizing the Court if the property right were not contested?Footnote 97

Based on this inconsistency between RCCB 256 and 274 on the one hand and RCCB 31, 47 and 51 on the other, Nukuri calls the jurisprudence of the Court in this respect a “chameleon jurisprudence” (jurisprudence caméléon).Footnote 98 The contradictory behaviour of the Court in these cases might well be explained by the politico-ethnic dimension of the laws under review. The respective commissions established by these laws had the mandate to rehabilitate repatriated refugees, who were predominantly Hutu, while the disputed properties were generally owned by Tutsi. Moreover, the respective majority parties in power (FRODEBU from 1993 and CNDD-FDD from 2005 to today) were predominantly Hutu; the repatriation and rehabilitation of refugees was one of the key elements of their electoral campaigns. Therefore, while the policy was perceived by Hutu as a rehabilitation, Tutsi considered it unjust expropriation. In RCCB 31, 34 and 35, the bench was composed of four Tutsi (including the president of the bench) and one Hutu.Footnote 99 In RCCB 256, it was composed of three Hutu (including the president) and two Tutsi, whereas there was a parity of three Hutu (including the president) and three Tutsi in RCCB 274. The data do not allow us to determine whether the judgments were made along ethnic lines: were the decisions passed by judges from one ethnic group only (using, in the last case, the casting vote of the president of the bench), or were they also backed by judges from the other ethnic group? In any case, given the inconsistency between the 1994 and the 2012–13 case law, there are no signs of a power-sharing court.

Composition and decision-making At the time when, during the period of transition (2000–2005), the 60 per cent Hutu–40 per cent Tutsi quotas were negotiated for the composition of the National Assembly and were then included in the 2005 Constitution, they reflected the balance of power of the Tutsi political elites. Quite importantly, they granted (a typically consociational) veto power to the Tutsi MPs, since a two-thirds majority was required for the adoption of any legislation and all other decisions taken by the National Assembly. At first sight, it is tempting to consider that the introduction in 2019 of the 60/40 per cent quotas for the Constitutional Court follows the same power-sharing logic.

In reality, however, this is only the case to a limited extent. The Court decides by simple majority, so the Tutsi judges hearing a case do not have a blocking minority.Footnote 100 Furthermore, no other rules encourage consensual decision-making, and there is also no (formal or informal) rule organizing a rotating presidency. On the other hand, however, judges do not publish separate opinions, which characterizes power-sharing courts, and there is also a quorum requirement of five (out of seven) judges. Hence, if 40 per cent of the seven judges (ie 2.8, rounded up to 3; see Figure 1) remain absent, they can – theoretically – block the Court from hearing a case. This has thus far remained a theoretical possibility; the minority of three Tutsi judges have never made use of this “weapon” which, in light of the early history of the Court (see above), is very likely to backfire against them.

View on judicial independence In the context of the peace process, Burundi clearly opted to prioritize a balanced composition of the apex courts over the expertise of their members. The 1992 Constitution required that the Constitutional Court judges be highly qualified jurists with at least eight years of professional experience.Footnote 101 Given the long-standing dominance of the Tutsi minority over the judiciary and at the Faculty of Law of the national university, this strongly reduced the pool of potential Hutu judges. After the APRA, the requirement of professional experience was annulled; this reflects the negotiated choice to give priority to a balanced Hutu–Tutsi composition over expertise.

Conclusion

The research question that guided the case study in this article asked about the function of identity-related quotas in the Burundi Constitutional Court. Our analysis shows that these quotas cannot be lumped together, even if they apply jointly to the same court. Gender quotas are used to make the Court reflective or to remedy past injustice. Ethnic quotas can have the same but also different functions: securing de-escalation of ethnic conflict or confirming the political balance of power in position-sharing arrangements. Our discussion of the Burundi Constitutional Court, using the typology of “quota courts” as an analytical lens, shows that quotas were inspired by various considerations, from redressing historical grievances to respecting the prevailing balance of power.

Where the literature is rather sceptical about judicial quotas based on a merit-based conception of the judicial independence principle, we argue that quotas do not necessarily affect the legal merit requirement. The judicial independence obstacle wrongly assumes that quotas undermine the requirement of legal merit and disregards the margin of interpretation that judges have in applying the law, especially when constitutional principles and values are at stake. In that respect, only the last model, which uses quotas as part of a position-sharing arrangement, is problematic.

The Burundi case shows that it is not always clear for what purpose quotas are introduced, although this is decisive for the functioning of the Court. This risks lumping the quotas together and could cloud the perception of the Court and of the groups to whom the quotas apply. The somewhat pejorative metaphor that President Ndayishimiye, on International Women’s Day, 8 March 2024, used for groups – including women – who claim positions in public institutions, comparing the state to a “jug of beer” which everyone wants to drink from, is illustrative.Footnote 102 When ethnic quotas are thus used to secure positions, this conflicts with the principle of judicial independence and may subsequently undermine the legitimacy of gender quotas that, in the case of Burundi, mostly piggyback on the ethnic quotas.

Competing interests

None