Case Presentation

Celia is a 54-year-old patient diagnosed with AJCC Stage II estrogen receptor-positive, Her2-negative invasive ductal carcinoma of the left breast at age 50. She received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, followed by lumpectomy and sentinel node biopsy, adjuvant whole breast radiation, and has been on an aromatase inhibitor for almost three years. She presents to the clinic to discuss worsening vaginal dryness and painful sex. She describes any sexual activity as “burning,” and any penetration feels “like papercuts”. She reports these symptoms started during chemotherapy but have worsened over time. She now avoids any sexual activity with her partner, and this makes her anxious. During her visit, she endorses very low desire since starting the aromatase inhibitor, and she explains that this is very distressing for her.

Etiology of Sexual Health Concerns in Female Cancer Patients

By 2026, more than 10 million US cancer survivors will be women, and at least half of those women will experience life-altering disruptions in sexual function as a sequela of their diagnosis or treatment [Reference Dizon, Suzin and McIlvenna1]. While sexual function concerns have common themes, the diverse presentation of these patients depends on preexisting health conditions, stage at diagnosis, and treatments received. Each patient’s perception of these issues is also variable and affected by cultural norms, societal acceptance, and even hygiene traditions passed down within families.

The spectrum of sexual health concerns ranges from psychological to physical effects. The diagnosis itself can lead to shame, distress, and patients’ confrontation with their own mortality. The physical manifestations include those arising from estrogen suppression which can be due to anti-estrogen medication, ovarian suppression during treatment, ovarian injury from cytotoxic chemotherapy, or bilateral oophorectomy. The likelihood of resolution of these symptoms is directly proportional to the availability of evidence-based patient education including mitigation strategies but also the familiarity of their providers with addressing these concerns.

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), formerly known as vaginal atrophy, is a well-known but understudied effect of induced menopause or estrogen blockade, which are two treatment strategies in the pre- or postoperative setting. GSM is an inclusive term that describes changes to the female vulva, vestibule, vagina, and pelvic floor. Prolonged estrogen suppression or receptor modulation, either by ovarian suppression or anti-estrogen therapy, systemic therapies influencing ovarian function, and surgical ovarian resection may lead to GSM. The sexual sequelae include vaginal dryness, painful sex, recurrent urinary tract infections, and incontinence. In a South Florida sexual health after cancer program at a National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated cancer center, patients presenting for care reported: 53% vaginal dryness, 45% painful sex, 10% urinary symptoms, and 5% problems with orgasm. These chief complaints are reported by more than 80% of patients found to have severe atrophy-related disruptions in their urogenital exams, and almost half were found to have a narrowed vaginal introitus precluding penetrative sexual intercourse [Reference Satish, Pon, Calfa, Perez and Rojas2]. With evolving targeted therapies and improved cancer survival, inadequate treatment of these quality-of-life and relationship-altering sequelae may lead to poor therapy compliance, tempering the field’s progress in long-term oncologic outcome improvements [Reference Baumgart, Nilsson, Evers, Kallak and Poromaa3].

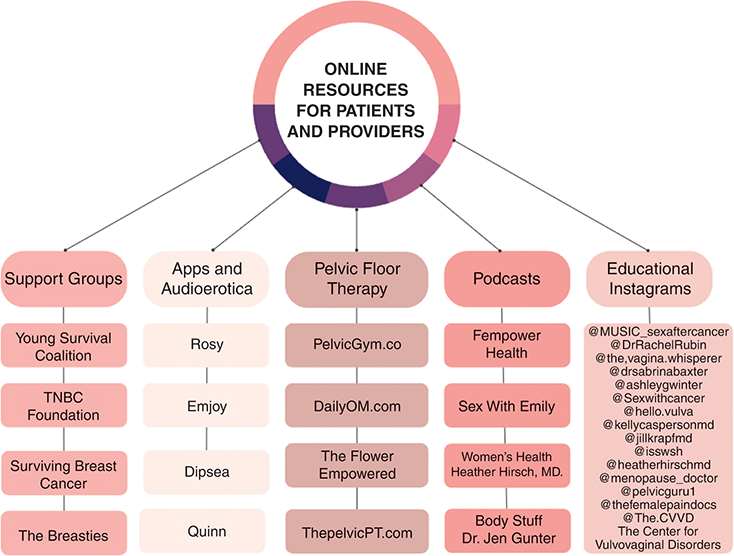

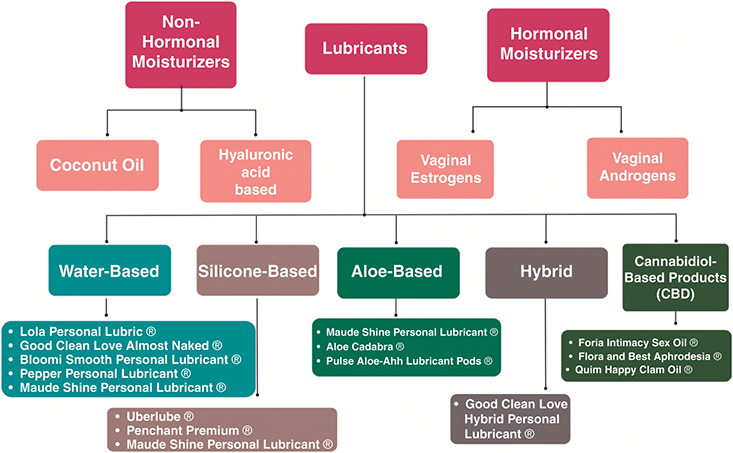

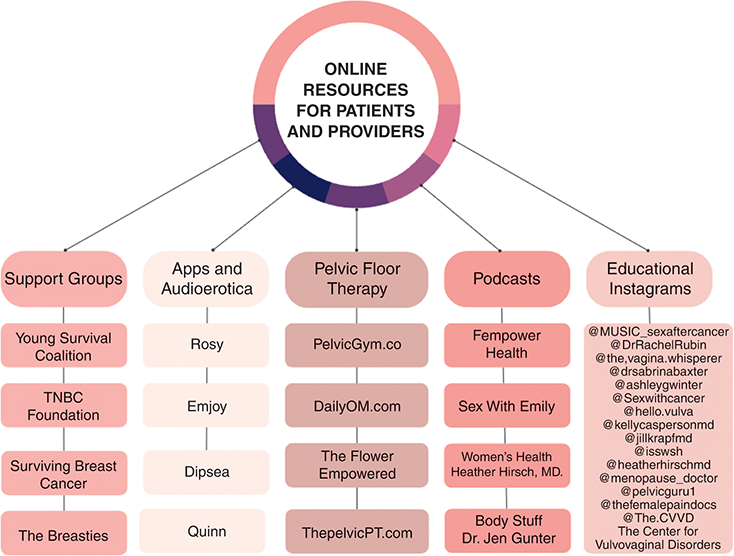

During treatment, women diagnosed with cancer may put their intimate lives on hold, indefinitely. The psychosocial hit of the diagnosis is quickly followed by rapid-fire diagnostic, staging, and subspecialist appointments until treatment is started. Their multimodal treatment regimen, coupled with the ongoing demands of daily living, caretaker activities, and professional careers, often translates to a hiatus from sexual activity, partnered or unpartnered. Many women report that the diagnostic phase of their cancer journey does not include a discussion about the sexual side effects of treatment. This contrasts with a study that found that over 50% of male patients diagnosed with prostate cancer receive information about how treatment will impact their sexual function, and this information often plays into the therapeutic route chosen after a shared decision-making discussion [Reference Wells-Prado, Ross and Simon Rosser4]. This moment prior to or at the initiation of therapy represents an opportunity for preparation and a discussion of best practices moving through treatment that can prevent the most severe sequelae. Strategies for approaching this discussion will be reviewed in this chapter. An author-curated collection of online resources for patients and providers to assist in these discussions is shown in Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1 Online sexual health resources for patients and providers

Sexual Health Concerns During and After Treatment

The Effect of Anti-Estrogen Therapies in Women with Estrogen-Sensitive Cancer

Anti-estrogen medications are a common culprit of sexual health concerns for women with breast and gynecologic cancer, but women with other cancer types may experience similar symptoms through other mechanisms. Approximately 70–80% of all breast cancer are hormone receptor-positive. As such, most women will receive anti-estrogen therapy after surgery (adjuvant therapy) to reduce the risk of recurrence. Anti-estrogen therapy, also known as hormone or endocrine therapy, functions by blocking or degrading estrogen receptors in the breast and other tissues or by suppressing circulating estrogen through peripheral aromatase inhibition. These drugs include selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs), and aromatase inhibitors (AIs). Adjuvant anti-estrogen therapy has been shown in multiple large trials to improve disease-free survival for postmenopausal women with invasive breast cancer [5]. Aromatase inhibitors may also be used in the treatment of gynecologic malignancies such as endometrial cancer and some types of ovarian cancer [Reference Slomovitz, Filiaci and Walker6].

Sexual Side Effects in Women on Anti-Estrogen Therapy

According to the North American Menopause Society, the normal postmenopausal estradiol (E2) range is likely lower than previously measured with conventional assays [Reference Richardson, Ho and Pasquet7]. With the more accurate measurements, the Society postulates that normal postmenopausal E2 is < 10 pg/mL [Reference Pinkerton, Liu and Santoro8]. A recent study utilizing the ultra-sensitive liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) method revealed that women on AIs may drive serum E2 levels as low as 0.16 pg/mL [Reference Santen, Mirkin, Bernick and Constantine9]. Prolonged estrogen deprivation can induce even more dramatic changes in vaginal architecture resulting in vaginal shortening, stenosis, and a complete inability to participate in penetrative sexual activity.

Anti-estrogen therapy is effective in both the preventive and adjuvant setting, but the side effect profile influences patient adherence [Reference Chlebowski and Anderson10, Reference Fallowfield, Cella and Cuzick11]. The gynecologic sequelae of anti-estrogen therapy lead to genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) symptoms including vaginal dryness, irritation, pain with sexual intercourse, bleeding after sex, recurrent vaginal infections, increased urinary tract infections, and dysuria. Those receiving treatment with anti-estrogen therapy, the effects of which may be multiplied by prior cytotoxic chemotherapy, are put into a “supermenopause” and report even more frequent and severe adverse effects on the vulva and vagina that can significantly impact quality of life [Reference Gandhi, Chen and Dagur12]. While natural menopause has been shown to increase the risk of hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in women, this risk is more profound in women an on anti-estrogen therapy: approximately half of the women on aromatase inhibitors report decreased libido, and 74% report insufficient lubrication [Reference Baumgart, Nilsson, Evers, Kallak and Poromaa3].

Symptoms of GSM and sexual dysfunction appear to be more common with aromatase inhibitor use when compared to tamoxifen use. In a survey study using the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) to evaluate sexual dysfunction among breast cancer survivors, women who had taken aromatase inhibitors were 1.6 times more likely to report sexual dysfunction when compared to the group that did not receive endocrine therapy [Reference Gandhi, Butler and Pesek13].

Younger women may be more dramatically impacted by abrupt changes in sexual function and are more likely to receive a recommendation for prolonged (>5 years) anti-estrogen therapy [Reference Burstein, Lacchetti and Griggs14]. Despite this recommendation, between 30–50% of breast cancer survivors are not compliant with their anti-estrogen medication, with >40% of women prescribed tamoxifen not adhering to therapy due to side effects, and 70% prematurely stopping anti-estrogen therapy before five years [Reference Chlebowski and Anderson10, Reference Fallowfield, Cella and Cuzick11]. Similarly, women who report severe side effects are five times more likely to stop taking their medication prematurely [Reference Bell, Dalton and McNeish15]. Better addressing these quality-of-life concerns including GSM and female sexual dysfunction has the propensity to improve treatment compliance.

Treatment of Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: Moisturizers

Avoiding Irritants

Vaginal or vulvar surgery, prolonged estrogen suppression, chemotherapy, or immunomodulating treatments may result in hypersensitivity of the delicate tissues of the vulva or vagina to certain product ingredients. Patients reporting the sensation of burning or irritation may have a worsening of their GSM symptoms from irritating products. For some, the onset of symptoms brings the temptation to apply a variety of drugstore feminine hygiene products including soaps and wipes, but this can lead to an exacerbation of symptoms. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), common vulvar irritants include but are not limited to: cleansers, fragrances, lubricants, bodily fluids such as urine and sweat, and moisture. Studies estimate that between 20–40% of women still practice vaginal douching, which disrupts the vaginal flora and increases the pH of the vagina [Reference Arbour, Corwin and Salsberry16]. Exposure to fragranced products is associated with the development of contact dermatitis, and therefore patients with sensitive skin should avoid their use [Reference van Amerongen, Ofenloch and Cazzaniga17]. These irritants are prevalent in sanitary pads, tampons, toilet paper, and bubble baths. Similarly, patients should avoid intravaginal soap use, only wear undergarments made of 100% cotton, avoid laundry detergents with fragrance, and promptly change out of wet swimsuits after water activities.

For patients who present with GSM and report the use of potentially offending topicals or irritant exposure, complete cessation of topical products while substituting single-ingredient organic coconut oil to the external vulva is an effective first step in treatment. Nonpetroleum emollients such as bland oils protect the irritated skin from acidic urine, giving it a chance to heal before adding in a hyaluronic acid or hormone vaginal moisturizer as discussed in the following sections. Patients should also be encouraged to study ingredient lists for all vulvar moisturizers or sexual activity lubricants (and to select their own lubricant) to avoid irritating chemicals. For patients concerned about hygiene with the elimination of vaginal washes, a discussion regarding how cessation of vaginal washes and wipes can reconstitute the vaginal lactobacilli and decrease vaginal infections may be helpful [Reference Brotman, Ghanem and Klebanoff18]. The addition of a bidet toilet attachment may also help patients feel more comfortable moving away from this hygiene ritual.

Vaginal Moisturizers

The conversation between a patient with GSM and her provider should start with a discussion regarding the difference between moisturizers and lubricants. Moisturizers have a distinct role from lubricants. By reducing friction at the time of sexual activity or dilator use, lubricants lead to decreased discomfort during and after these activities. Lubricants are used “in the moment.” Moisturizers, on the other hand, should be thought of similarly to moisturizers in the (nonintimate) skincare world: as part of a “maintenance” routine. The authors propose a vulvovaginal care algorithm that starts with irritant elimination and the regular use of nonhormonal moisturizers. The regimen may be weekly, two to three times weekly, or nightly, and may be adjusted according to symptom severity and evolution. Local hormone therapy can be added in the weeks or months after initiating a nonhormonal regimen if patients have persistent symptoms, as will be discussed later in this section.

Nonhormonal Vaginal Moisturizers

Oil-based therapies for vaginal moisturization include coconut oil, olive oil, and Vitamin E oil. While oils are commonly found in patients’ pantries and may be seen as more “holistic” or “natural,” data proving their effectiveness is limited, especially when compared to newer “higher-tech” nonhormonal moisturizers containing hyaluronic or lactic acid. However, they may be helpful when used as an emollient to protect irritated or radiated vulvovaginal epithelium, for periurethral protection from dysuria, or as a treatment “base” in which additional therapies can be added. Coconut oil is reported to have antimicrobial, antifungal, and antioxidant properties. In vitro studies have demonstrated growth inhibition of both clostridium dificile and several species of candida by virgin coconut oil [Reference Ogbolu, Oni, Daini and Oloko19, Reference Shilling, Matt and Rubin20]. Limited evidence suggests that vitamin E vaginal suppositories may be a viable alternative to estrogen-based topical therapy in select patients, as its antioxidant properties may work to repair the vaginal epithelium [Reference Porterfield, Wur and Delgado21]. Patients should be counseled against the use of petroleum jelly as a moisturizer or lubricant since incomplete refinement of petrolatum or petroleum jelly is associated with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which are possible carcinogens [22]. In sexually active patients, it is important to note that oil-based moisturizers may not be compatible with latex condoms.

Synthetic vaginal moisturizers containing hyaluronic acid (HLA) or lactic acid reduce GSM symptoms and improve sexual function. In healthy reproductive-aged women, the vaginal microbiome is characterized by the predominance of lactic-acid-producing Lactobacillus species. Lactic acid may suppress pathogenic bacteria, and therefore supplementation with exogenous lactic acid is thought to work the same way [Reference Plummer, Bradshaw and Doyle23]. Hyaluronic acid is a polymer of disaccharides that has the unique capacity to retain water. The use of hyaluronic acid-based vaginal preparations three times per week for eight weeks improved patient symptoms and vaginal health indices as measured by the Vaginal Health Index (VHI) in 46 postmenopausal women with symptoms of GSM [Reference Nappi, Martella and Albani24].

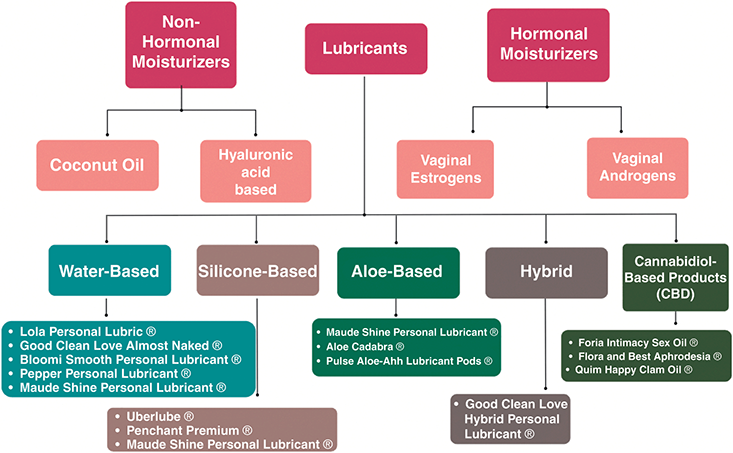

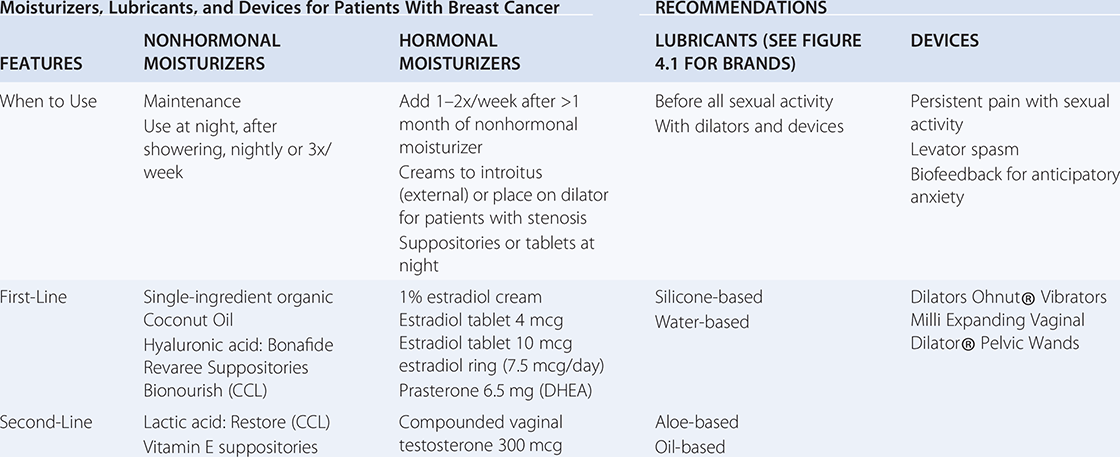

Hyaluronic acid vaginal suppositories may result in similar improvement in GSM symptoms when compared to vaginal estrogen. A randomized trial of 56 postmenopausal women received either vaginal conjugated estrogen (0.62 mg) or hyaluronic acid vaginal moisturizer as a tablet preparation. Both groups demonstrated improvement in GSM symptoms, vaginal pH, and dyspareunia [Reference Jokar, Davari, Asadi, Ahmadi and Foruhari25]. The effectiveness of HLA was more recently demonstrated in partnered and unpartnered women with a history of estrogen-sensitive uterine cancer. Daily application of HLA for two weeks, then three to five times per week improved vulvovaginal health and sexual function [Reference Carter, Goldfarb and Baser26]. Figure 4.2 outlines moisturizer types and detailed recommendations of lubricant brands, by type.

Vaginal Estrogen

Vaginal Estrogen in Women Without Estrogen-Sensitive Cancer

Hormonally unresponsive cancers proliferate independently of hormonal substrates due to a lack of hormone receptors. Vaginal estrogen therapy is not contraindicated, and instead, should be encouraged in women with GSM and hormone-unresponsive cancer. These cancers include cervical, vulvovaginal squamous, colorectal, and hematologic malignancies [Reference Sinno, Pinkerton and Febbraro27].

Vaginal Estrogen in Women With Estrogen-Sensitive Cancer

The most effective treatment for GSM is vaginal estrogen, but prior studies have shown that absorption of vaginal estrogen may temporarily increase circulating estradiol, which limits provider comfort with its use in women with a history of hormone-sensitive cancer [Reference Santen, Mirkin, Bernick and Constantine28]. A recent retrospective Danish study of patients treated for breast cancer between 1997–2004 suggested an increased risk of recurrence in certain breast cancer patients through an analysis of hormone users versus nonusers. Within this study, the only comparison suggesting an increased risk of recurrence in vaginal estrogen users was limited to those on aromatase inhibitors. Notably, the breast cancer treatment regimens predate modern guidelines in that Her2-targeted therapies were not used, and many with estrogen receptor positive tumors did not take endocrine therapy, therefore recurrence rates were higher than contemporary estimates. Furthermore, important confounders of recurrence including body mass index and physical inactivity were not accounted for [Reference Cold, Cold and Jensen29]. Therefore, these data must be considered in light of the competing increased risk of recurrence associated with endocrine therapy noncompliance in patients whose GSM symptoms go untreated.

Studies examining vaginal estrogen use in women with gynecologic malignancies report rare adverse outcomes with comparable recurrence to those not prescribed vaginal estrogen. In a multicenter, retrospective cohort study, 244 women with a diagnosis of either endometrial, cervical, or ovarian cancer were prescribed vaginal estrogen. Overall adverse events were low, and recurrence rates were comparable to those of the general population. Despite the North American Menopause Society’s (NAMS) endorsement that hormone therapy is safe for use in patients with early-stage, low-grade, surgically-treated-treated endometrial cancer, completely resected ovarian cancer, colorectal, and lung cancer, vaginal estrogen is still underutilized in these populations due to past dogma [Reference Chambers, Herrmann, Michener, Ferrando and Ricci30].

Treating GSM in women with estrogen-sensitive cancer represents a complex clinical challenge. While local hormone therapy applied to the vulvar and/or vaginal mucosa is distinct from “systemic” hormonal therapy given through oral or transdermal routes, increases in circulating estradiol may still occur, although temporary. For this reason, despite its proven superiority to nonhormonal moisturizers, some clinicians are still hesitant to prescribe low-dose vaginal estrogen to women on anti-estrogen therapy for fear of absorption-related increases in serum estradiol and the hypothetical increased risk of cancer recurrence [31].

There is no established threshold for the “safe” level of estradiol in women with a history of estrogen-sensitive cancer. The North American Menopause Society released a symposium report in 2020 that sought to establish normal postmenopausal estrogen ranges. They determined that estradiol levels were age-dependent and ranged from a mean of 8.2 pg/mL in women 40–45 to 3.5 pg/mL in women >70 years of age [Reference Pinkerton, Liu and Santoro8]. Absorption of vaginal estrogen is higher when the mucosa is atrophic and decreases with time, usually after two to four weeks. Lower doses of vaginal estradiol with less frequent dosing leads to smaller plasma estradiol increases. Santen et al. recently updated a prior review of the literature measuring systemic absorption of estradiol utilizing highly-specific LC-MS. Serum estradiol in women using low-dose (10 mcg) and ultralow-dose (4 mcg) estradiol suppositories ranged from 4.6–14.8 pg/mL for the 10 mcg dose to 3.6–3.9 pg/mL for the 4 mcg dose, and these increases resolved by the fourth day of treatment for those using the 4 mcg dose [Reference Santen, Mirkin, Bernick and Constantine9]. The authors concluded that systemic estrogen absorption with low-dose or ultralow-dose vaginal estrogen is minimal, suggesting that the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) “black box” warning linking estrogen and breast cancer is likely overstated given that there is not a significant increase in serum estradiol levels with very low dose vaginal estradiol formulations. According to a 2016 ACOG Committee Opinion, low-dose vaginal estrogen may be more appropriate in patients taking tamoxifen since this medication binds to receptors in breast tissue, blocking estrogen’s downstream effects, and therefore its efficacy is not impacted by the potential absorption of vaginal estrogen [Reference Biglia, Bounous and D’Alonzo32].

In light of this ongoing controversy, for women with a history of estrogen-sensitive cancer, the authors recommend eliminating potential irritants and initiating a regimen of a nonhormonal moisturizer followed by the introduction of once- or twice-weekly low-dose vaginal estrogen for persistent symptoms (as opposed to the daily regimen utilized in the absorption studies). For patients with mild symptoms, starting with single-ingredient organic coconut oil may be sufficient, while a hyaluronic acid suppository may be better suited for those with severe symptoms. For women in whom symptoms persist at two months, once-weekly low-dose vaginal estrogen can be initiated and increased to twice weekly after two weeks. Oftentimes if regular sexual activity can be re-initiated, treatment with vaginal estrogen can eventually be tapered down to once weekly or stopped.

Vaginal Androgens

Recent studies have focused on the use of vaginal androgens to treat symptoms of GSM and sexual dysfunction. The tissues of the vulva and vagina have receptors for both androgens and estrogen, and the glands responsible for lubrication during arousal require androgens to function. Deficiencies of both hormones occur naturally during menopause, and patients with severe GSM are often found to have focal pain at specific points in the vulvar anatomy near the ostia of the Bartholin’s glands (4:00 and 8:00 o’clock) and Skene’s glands (1:00 and 11:00 o’clock), which are sites dependent on androgens [Reference Dew, Wren and Eden33]. This pain can culminate in severe penetrative dyspareunia and eventually chronic neuropathic pain.

DHEA or Prasterone

The androgens dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), DHEA, and androstenedione do not have androgenic activity unless they are converted to either testosterone or dihydrotestosterone (DHT), where they exert their action locally. In peripheral tissues, the prohormone DHEA is converted to the more active testosterone and DHT, exerting its action in the same cells where their synthesis takes place with minimal release into the circulation [Reference Traish, Vignozzi, Simon, Goldstein and Kim34]. After their local formation and intracellular use, testosterone and DHT are inactivated and transformed into water-soluble glucuronide derivatives and eliminated through the circulation [Reference Labrie35]. They may also be converted to estrogens by aromatase. Theoretically, an increase in serum testosterone may lead to increased serum estradiol, although this conversion may be at least partially inhibited by aromatase inhibitors.

In 2016, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of an androgen formulation for vaginal use, a 6.5 mg prasterone (synthetic DHEA) suppository for the use of dyspareunia in postmenopausal women. DHEA made within the body is generated and secreted from the zona reticularis of the adrenal glands, and its secretion frequency and quantity decreases with age [Reference Labrie, Luu-The and Bélanger36]. Another notable function of DHEA is that it is a potent noncompetitive inhibitor of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase which lowers the production of oxygen free radicals leading to decreased oxidative stress and inflammation, which mechanistically may also contribute to the symptoms seen in the vulva and vagina. Vaginal prasterone was found to improve GSM symptoms including painful sex in postmenopausal women, demonstrating improvement in both subjective and objective measures [Reference Liu, Lin, Huang, Ivy and Kuo37, Reference Schwartz and Pashko38].

DHEA was more recently studied in women with a history of breast cancer. The double-blind randomized Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology (NCCTG-N10C1) Trial compared compounded vaginal DHEA to a plain vaginal moisturizer [Reference Labrie, Archer and Bouchard39]. Four hundred and sixty-four women with a history of breast or gynecologic cancer were randomized to either DHEA or plain moisturizer. Women on AIs who received DHEA experienced the same level of improvement in vaginal symptoms as those not on AIs without a subsequent change in serum estradiol. This finding supports that vaginal DHEA is not working through estrogenic means and may be an appropriate treatment for this population [Reference Barton, Sloan and Shuster40]. A Guideline Summary released by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) in 2018 recommended consideration of vaginal DHEA (prasterone) or vaginal estrogen in appropriately counseled women with breast cancer who did not respond to nonhormonal treatments [Reference Carter, Lacchetti and Andersen41]. The limitation to widespread uptake of this FDA-approved commercially available prasterone product is cost: it is expensive for some women without commercial insurance who are not eligible for the coupon program.

Vaginal Testosterone

Vaginal application of testosterone has not been FDA-approved for the treatment of vulvovaginal symptoms and/or sexual dysfunction related to women’s cancer treatment, but its compounded form has been studied in women with breast cancer. In 2011, Witherby et al. treated 21 women on aromatase inhibitors with GSM symptoms with daily vaginal compounded testosterone cream for four weeks. Half of the study group received a dose of 150 mcg, and the other half 300 mcg. In both arms, serum estradiol levels remained well below the cutoff for the menopausal range (20 pg/mL) at <8pg/mL. The investigators also found symptom improvement in both arms that persisted more than a month after therapy [Reference Witherby, Johnson and Demers42]. A more recent study looked at global sexual functioning outcomes in 12 patients on aromatase inhibitors prescribed the same four weeks of therapy. Serum hormone levels were not measured but all domain scores of the FSFI were noted to significantly improve [Reference Dahir and Travers-Gustafson43].

The efficacy of vaginal androgens compared to vaginal estrogen in women on AIs has been compared in two prospective trials. In 2016, Melisko et al. found that patients using a 1% testosterone cream (5000 mcg in 0.5 gm dose) every night for two weeks, then three times per week had similar improvements in vaginal symptoms and sexual interest compared to those who received an estradiol vaginal ring [Reference Melisko, Goldman and Hwang44]. The large dose of vaginal testosterone utilized in this study (5000 mcg compared to 300 mcg in study by Witherby et al.) was based on data treating sexual desire disorders in postmenopausal women [Reference El-Hage, Eden and Manga45] but resulted in elevated serum total testosterone (greater than the postmenopausal range of 2 ng/dL to 45 ng/dL in 24 of 27 patients). A nested case-control cohort of women from the Women’s Health Eating and Living (WHEL) study did not find an increased risk of breast cancer recurrence in women with higher baseline testosterone levels, but this question necessitates further study [Reference Rock, Flatt and Thomson46].

In summary, studies have demonstrated improvement in vaginal health and sexual function with large doses of vaginal testosterone (5000 mcg) that resulted in significant increases in serum testosterone, the significance of which is unknown in cancer survivors. Lower doses of vaginal testosterone (300 mcg) may produce improvement in vaginal health and potentially overall sexual satisfaction without the derangements in sex steroid hormone levels described in studies utilizing the larger testosterone dose (5000 mcg) or vaginal estrogen. However, the authors recommend initiating therapy with FDA-approved formulations instead of compounded hormones due to concerns regarding dose, purity, efficacy, and safety, which will be discussed further in the following section.

Bioidentical Hormones

Hormone prescriptions prepared by a compounding pharmacist may combine multiple hormones (estrogens, progesterone or synthetic progestins, and androgens) into unapproved mixtures and may be administered orally, transdermally, vaginally, or through untested routes such as subdermal implants or pellets. “Bioidentical” hormones are a marketing term, as both compounded and FDA-approved hormonal formulations can be “bioidentical.” The difference between government-approved bioidentical estradiol, estrone, and medroxyprogesterone and their compounded versions is that the former are regulated and monitored for purity and efficacy. Furthermore, FDA-approved versions are sold with a package insert containing detailed patient and provider instructions, trial evidence of safety and efficacy, and government-mandated black box warnings if they exist [31].

Strategic marketing and the appeal of bespoke hormone recipes have led to an increase in the popularity of compounded hormonal formulations in recent years. The use of pelleted hormone therapy to treat menopausal symptoms is on the rise, and cancer patients may be particularly susceptible to this treatment touted as “safer” than FDA-regulated hormonal therapy. However, pelleted therapy leads to higher rates of side effects and supraphysiologic hormone levels. In 2021, Jiang et al. compared 539 postmenopausal women that received either pelleted hormonal therapy or FDA-approved therapy. The incidence of side effects was higher among those who received pelleted hormone therapy, and more than half of these patients with a uterus reported abnormal uterine bleeding. Mean and peak serum estradiol and testosterone levels were significantly higher in the pelleted hormone cohort, where peak estradiol reached 237.7 pg/mL (versus 93.45 pg/mL in the FDA products) and peak testosterone reached 194.04 pg/mL (versus 15.59 pg/mL). Notably, four women using pelleted therapy were found to have a serum estradiol >1000 pg/mL and nine women were found to have serum testosterone >400 ng/dL [Reference Jiang, Bossert and Parthasarathy47].

There is little to no evidence that hormone-containing products from compounding pharmacies are more safe or effective than FDA-approved hormone prescriptions. According to the NAMS, there is insufficient evidence to support the clinical use of compounded bioidentical hormone therapy for the treatment of menopausal symptoms, although there are serious concerns about the lack of safety data and government dosing regulation. If a patient cannot tolerate a government-approved therapy, prescribers choosing to utilize the services of compounding pharmacies should document the medical indication and provide the patient with the financial disclosures of the prescribers, pharmacists, and pharmacies. Lastly, compounding pharmacists should provide standardized content information including warnings of potential adverse effects and clearly stating that the preparation is not government-approved [31].

Vaginal Lasers

The perception of limited treatment options for sexual dysfunction has fostered an environment where patients with these quality-of-life impacting symptoms (and their providers) seek “alternative” therapies. Laser devices promising “vaginal rejuvenation” are being promoted to women in advertisements online, in spa windows, and in doctors’ offices. Using lasers to treat skin conditions goes back as early as 1963 as a method for treating moles and warts [Reference Goldman, Blaney and Kindel48]. In the years since, however, the medical aesthetics industry has gone beyond applying this technology on the external body to using it in the vagina, claiming it can treat a broad range of gynecologic and urologic conditions.

Patients with severe genitourinary changes related to cancer treatment-related estrogen deprivation or pelvic radiation may be susceptible to abnormal healing after treatment with energy-based devices, whose efficacy depends on the creation of microscopic injury and subsequent collagen formation. One of the most popular CO2 lasers was cleared by the FDA in 2014 “for use in general and plastic surgery and in dermatology.” However, the 501(k) fast-tracking program is not an “approval” in the way the FDA approves medications to be safe for consumption, but more like a system of device registration for manufacturers.

Since granting the 510(k) registration for the CO2 laser, the FDA has issued a notice alerting providers and patients that the safety of these devices has not been established for cosmetic procedures on the vulva or in the vagina. The advisory warned consumers about “bad actors” who promote the “unapproved, deceptive product” and described how devices marketed as providing “vaginal rejuvenation” caused “numerous cases of vaginal burns, scarring, pain during sexual intercourse, and recurring or chronic pain.” [49].

The argument against the use of CO2 laser devices in the medical aesthetics industry goes beyond questions of safety in patients treated for cancer: they may not even be effective. Two prospective randomized controlled trials found the device to be no better than a sham. In 2021, Li et al. reported the results of a sham-controlled, double-blinded, randomized clinical trial that included 90 women with postmenopausal vaginal symptoms treated with three treatments of a fractional microablative carbon dioxide laser four to eight weeks apart, or the same number of sham procedures where the device was placed in the vagina and turned on. There was no difference in symptom severity or histological comparisons between the laser and sham treatment groups [Reference Li, Maheux-Lacroix and Deans50]. A similar sham-controlled randomized trial including breast cancer patients did not find that treatments with the laser was superior to placebo [Reference Mension, Alonso and Anglès-Acedo51].

Cancer patients may be particularly susceptible to the marketing messages of the companies of these devices, and providers should be aware of the lack of prospective data demonstrating efficacy, along with the potential dangers. The FDA has warned at least seven manufacturers to cease advertising their products for unapproved uses. Patients who have experienced adverse events are encouraged to report their experience to the FDA’s Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) online database.

Dyspareunia

Lubricants

For pain with penetration, lubricants should be used with sexual activity and dilator use and should be distinguished from vaginal moisturizers. The optimal lubricant is one with minimal irritants that will minimize friction and therefore minimize intra- and postcoital spotting and burning. Patients should be encouraged to select their own lubricant for sexual activity instead of allowing their partner to select the lubricant. For patients that do not rely on condoms for pregnancy or infection protection, the authors recommend a silicone-based lubricant without parabens, glycerin, flavors, or other gimmicks. Water-based lubricants should be used with silicone toys or with condoms. Patients who report persistent burning after sexual activity may be irritated by an ingredient in the lubricant and they may benefit from selecting an alternative product. Oil-based lubricants are helpful for patients with persistent burning after sexual activity, but they are less slippery and will degrade latex condoms and silicone devices. Table 4.1 highlights nonhormonal moisturizer brands, hormonal moisturizer dosing, lubricant types (brands shown in Figure 4.1), and sexual devices.

Table 4.1 Nonhormonal moisturizers, hormonal moisturizer dosing, lubricant types, and sexual devices

| Moisturizers, Lubricants, and Devices for Patients With Breast Cancer | RECOMMENDATIONS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEATURES | NONHORMONAL MOISTURIZERS | HORMONAL MOISTURIZERS | LUBRICANTS (SEE FIGURE 4.1 FOR BRANDS) | DEVICES |

| When to Use |

|

|

|

|

| First-Line |

|

|

| Dilators Ohnut® Vibrators Milli Expanding Vaginal Dilator® Pelvic Wands |

| Second-Line |

| Compounded vaginal testosterone 300 mcg |

| |

Vaginal Stenosis

Untreated GSM can lead to the shortening and narrowing of the vagina, known as vaginal stenosis. Vaginal stenosis (VS) is a subacute to late toxicity that was originally described in women undergoing pelvic radiation or radical surgery for gynecologic malignancies. There is currently no standard definition, but it has been described as the inability to insert two fingers in the vagina [Reference Nunns, Williamson, Swaney and Davy52] and the shortening of the vagina to less than 8 cm [Reference Flay and Matthews53]. Its prevalence in women with a history of pelvic radiation ranges from 13% to 88% [Reference Miles and Johnson54].

Vaginal stenosis has been unexpectedly observed in women receiving treatment for GSM who were receiving anti-estrogen therapy, without a history of pelvic radiation. In the OVERcome (Olive Oil, Vaginal Exercise, and MoisturizeR) study, 11% of breast cancer survivors [Reference Juraskova, Jarvis and Mok55] that presented for enrollment were found to have VS and had to be excluded from the intervention. In a sexual health after-cancer program in South Florida, approximately half the women who presented for treatment after several years of anti-estrogen therapy were found to have VS making penetrative intercourse either impossible or extremely painful [Reference Shields, Kobiella and Jeung56].

Vaginal stenosis may also prevent pelvic examinations necessary for cancer surveillance. Vaginal dilator use during cancer treatment can be particularly helpful for patients not sexually active by preserving the length and width of the vagina during periods of estrogen suppression. Dilator therapy improves elasticity but also provides biofeedback during pelvic floor relaxation exercises. Multiple studies have demonstrated that consistent use of a vaginal dilator during radiation treatment results in a reduced risk of VS [Reference Gondi, Bentzen and Sklenar57, Reference Bahng, Dagan, Brunner and Lin58, Reference Law, Kelvin and Thom59], and published practice guidelines recommend having the patient use the dilator in the vagina with a lubricant three times per week for 10 minutes per dilation [Reference Miles and Johnson60]. Dilators are ideally supplied at no cost to the patient by their medical providers, but could also be purchased through CMT medical (www.cmtmedical.com) or several other online vendors, including SoulSource®, IntimateRose®, and BioMoi® . Another sexual device helpful for patients with deep dyspareunia, termed a collision dyspareunia aid, is the Ohnut, which consists of soft, stackable rings that may be placed around the penis, dilator, or other sexual apparatus to limit the depth of penetration (Table 4.1).

Future work should focus on increasing provider and patient comfort with prescribing and utilizing dilator therapy. Patient adherence to a vaginal dilator regimen is reportedly very low. In one study, even after counseling and instruction, only 57% of patients had used the dilator at six months and only 14% dilated at the recommended three times per week [Reference Schover, Miller, Bowen, Croyle and Rowland61]. However, when dilators are utilized, they are effective. In an observational study of 89 women who received pelvic radiation, median vaginal length increased from 6 to 9 cm over four months of dilator use. The addition of vaginal hormonal therapy as described above to dilator regimens may help further reverse the effects of vaginal stenosis through remodeling of the vaginal architecture [Reference Velaskar, Martha, Mahantashetty, Badakare and Shrivastava62].

Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy

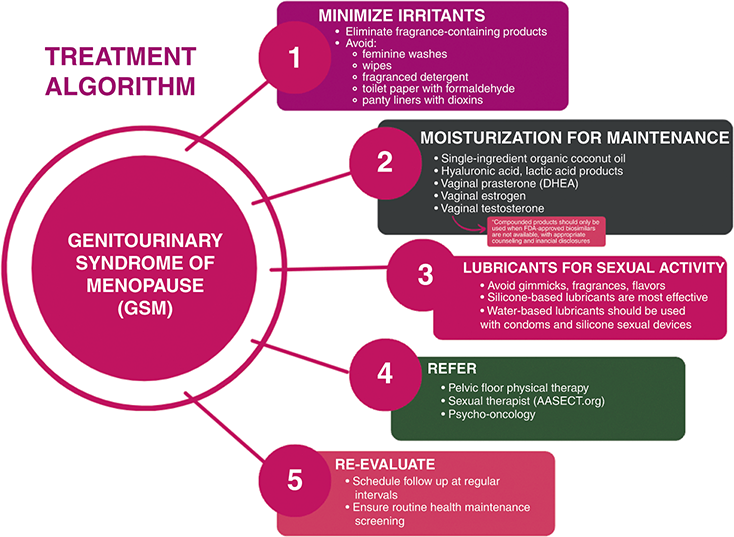

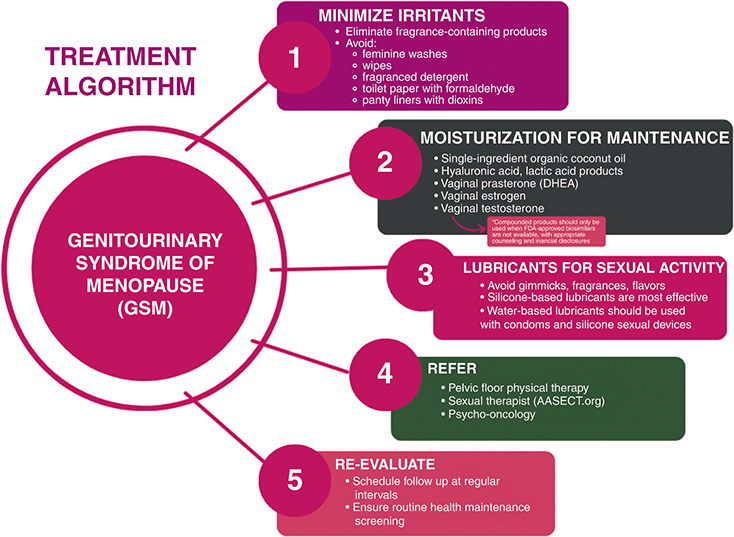

In women with GSM, pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT), provided by pelvic floor-specific physical therapists, is indicated for those with the concomitant diagnosis of pelvic floor dysfunction. In a prospective cohort study undertaken by Mercier et al., thirty-two postmenopausal women underwent PFMT for 12 weeks with a significant reduction of GSM symptoms and improved sexual function [Reference Mercier, Morin and Zaki63]. These results suggest an important indication for PFMT beyond pelvic floor weakness and urinary incontinence. A detailed external pelvic floor muscle and internal pelvic assessment are performed at a first PMFT visit, individualized to patient comfort. During this first visit, patients can expect that their pelvic floor therapist will take a detailed history, then perform both an external and internal pelvic exam, with additional orthopedic assessments as needed. Patients are usually sent home with educational materials and techniques that were taught in office to review and practice. Over the subsequent treatment visits, a personalized pelvic floor program is created, which may include continued education, yoga or stretching, biofeedback, electrical stimulation, diaphragmatic breathing, trigger point release, meditation, and with pelvic wand and dilator training, and intimate relationship preparation [Reference Wallace, Miller and Mishra64]. Figure 4.3 summarizes the authors’ recommendations for the treatment of GSM including irritant minimization, moisturization, lubricants, and referrals.

Low Desire During and After Cancer Treatment: Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder

In female patients with a history of cancer reporting sexual dysfunction, 36% report low desire as their most significant concern [Reference Satish, Pon, Calfa, Perez and Rojas2]. Low desire is complex but may be a sequela of androgen suppression, the negative stimulus of painful sexual activity, or the result of the psychologic insult of enduring a cancer diagnosis and treatment. Treating dyspareunia, if present, is the first (and easiest) step to improving desire. Second, patients should be counseled about behavioral interventions. Regular physical activity, sleep hygiene (no screens in bed), and scheduled “date night” are appropriate recommendations. If there is relationship discord, this can be addressed with a referral to a couple’s counselor or a sexual therapist. The American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors, and Therapists (AASECT) website offers a search function for licensed practitioners by zip code (www.aasect.org).

There are two FDA-approved therapies for female hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD): flibanserin and bremelanotide [Reference Portman, Brown, Yuan, Kissling and Kingsberg65, Reference English, Muhleisen and Rey66]. Flibanserin, a post-synaptic 5-HT1a agonist, a partial D4 agonist, and a 5-HT2a antagonist, is a once-a-day pill that was originally developed as an antidepressant. It is effective in treating HSDD in premenopausal women but comes with a significant side effect profile. It was originally approved with the caveat that all providers must undergo specific risk management training related to hypotension and syncope when combined with alcohol. However, these regulations have since been lifted and now the formal recommendation is that women should discontinue drinking alcohol at least two hours prior to taking flibanserin or skip their dose that evening [Reference Stevens, Weems, Brown, Barbour and Stahl67, Reference Clayton, Althof and Kingsberg68]. Bremelanotide is a novel melanocortin receptor agonist given as a subcutaneous injection prior to sexual activity. Similar to flibanserin, bremelanotide is FDA-approved in pre-menopausal women with HSDD, and has demonstrated dose-responsive improvements in desire, arousal, and reductions in sexual-related distress. [Reference Kingsberg, Clayton and Portman69]. The most prevalent side effect is nausea, with 40% of patients in two randomized trials experiencing some level after medication administration [Reference Simon, Kingsberg, Shumel, Hanes, Garcia and Sand70]. Notably, both flibanserin and bremelanotide are FDA-approved to treat HSDD in premenopausal patients, although flibanserin has reported efficacy in postmenopausal patients as well [Reference Katz, DeRogatis and Ackerman71].

While studies of patients taking both tamoxifen and flibanserin are ongoing, there is a dearth of evidence supporting their safety together in women with a history of cancer. However, both flibanserin and bremelanotide function centrally and are not sex hormone-dependent and therefore can be considered in certain situations with careful attention to drug-drug interactions.

Systemic testosterone as a treatment for HSDD was endorsed in 2019 through a Global Consensus Position Statement that included NAMS and other societies [Reference Davis, Baber and Panay72]. However, there is no universally accepted premenopausal serum concentration that predicts efficacy, and the safety of systemic androgens, particularly when some triple negative breast cancer are known to express an androgen receptor, is not known.

Case Resolution

Celia is a 54-year-old patient with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer with worsening vaginal dryness, painful sex, and low desire. She received education about irritant minimization and initiated a three-times weekly hyaluronic acid suppository for vaginal moisturization. She was also given a medium-sized dilator and instructions to use with a silicone-based lubricant three times per week. After two months, she reported significant improvement in her symptoms and reinitiated weekly sexual activity with her partner.

Take Home Points

Cancer treatment negatively impacts sexual health and is reported by more than half of female cancer survivors across disease sites, creating a high demand for both patient education and mitigation strategies.

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) is a common sequela of treatment and can result from surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiation, and estrogen-suppressing therapies.

Vaginal washes, irritating chemicals, and artificial fragrances can worsen symptoms of GSM and should be avoided.

First-line treatment for GSM in women without a history of estrogen-sensitive cancer is vaginal estrogen. The regular use of nonhormonal moisturizers such as single-ingredient organic coconut oil or commercially available moisturizers with hyaluronic acid is an appropriate first step in women with estrogen-sensitive cancer, although vaginal prasterone or low-dose vaginal estrogen may be added once or twice weekly if symptoms persist.

“Bioidentical hormones” is a marketing term, and compounded formulas should only be used when a biosimilar FDA-approved version with known dose and pharmacokinetics is not available.

Dilators are underused but effective at decreasing dyspareunia and improving vaginal stenosis when used regularly. Patient education is important to ensure treatment adherence, and the recommendation is to place the dilator intravaginally three times weekly for ten minutes.

Patients with a history of cancer with GSM should not be referred for treatment with energy-based devices including CO2 lasers. Patients experiencing adverse events should be encouraged to report their experience to the FDA’s Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) online database.

Low desire is complex, but treating dyspareunia and behavioral interventions may improve symptoms. Two FDA-approved medications for premenopausal patients with hypoactive sexual desire disorder (filbanserin and bremelanotide) have been shown to be safe and effective with caution to avoiding drug-drug interactions.