Introduction

Since the late 1990s, the third wave of democratisation has given way to the third wave of autocratisation (Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019; Diamond Reference Diamond2021). While twentieth-century dictatorships typically relied on deterrence to maintain compliance of the general population, most autocracies today apply significantly different strategies to remain in power. Empowered elites, the rise of the liberal world order, and economic and informational globalisation made it harder to maintain isolated repressive dictatorships (Guriev and Treisman Reference Guriev and Treisman2022). Therefore, typical modern-day autocracies refrain from overt repression, seek to keep a democratic facade and organise elections. Although elections are not free and fair, they are nevertheless meaningful and competitive (Guriev and Treisman Reference Guriev and Treisman2022). Such regimes are referred to as competitive authoritarian (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2002, Reference Levitsky and Way2020; Diamond Reference Diamond2021).

Corruption—broadly defined as the use of public office for private gain (Rose-Ackerman and Palifka Reference Rose-Ackerman and Palifka2016)—plays an important role in such regimes as incumbents rely on it to consolidate and maintain power by (re)distributing wealth and economic opportunities through corrupt networks (Johnston 2006; Mungiu-Pippidi Reference Mungiu-Pippidi2006). Evidence shows that competitive authoritarian regimes (and in a broader sense, hybrid regimes) are the most prone to corruption (McMann et al. Reference McMann2020). However, a closer examination of corruption in competitive authoritarian settings unfolds an intriguing picture: such regimes often take significant measures to curb certain types of corruption (Quah Reference Quah1999; Ang Reference Ang2020b).

For instance, in Malaysia, a large-scale corruption scandal (“1MDB”) led to the introduction of a series of significant anti-corruption measures (Dettman and Gomez Reference Dettman and Gomez2020). Evidence also shows that certain forms of corruption were effectively curbed in Russia (Rochlitz et al. Reference Rochlitz, Kazun and Yakovlev2020) and Hungary (Ligeti et al. 2020). Perhaps the most famous example—the outlier of many corruption studies—is Singapore, where a highly successful anti-corruption framework has been implemented (Quah Reference Quah1999; Abdulai Reference Abdulai2009). For many years, the country has been ranked among the least corrupt countries globally by Transparency International.

This study aims to explain these puzzling outcomes. To that end, by contrast to the prevalent, but recently, increasingly criticised (Heywood Reference Heywood2017) country-level approach to corruption, I delineated different types of corruption within countries and argue that these incur various costs and benefits for the regime. The regime, presumed to be a rational utility maximiser, assesses the net costs and benefits (i.e. the net gains) associated with corruption types, and decides to enhance or curb them based on these assessments. The principal ambition of this article is to present an explanatory framework that elucidates the various factors that influence the net gains of corruption types in the context of competitive authoritarianism. While the present paper does not aim to provide solid empirical proof for the presented explanatory framework, its applicability is demonstrated by case studies of two corruption types in Hungary. This ambition is relevant for the following reasons.

Firstly, the article contributes to the streams of literature focusing on the relationship between regime types and corruption (Rock Reference Rock2009; Saha et al. Reference Saha2014; McMann et al. Reference McMann2020), and corruption in competitive authoritarian and similar regimes (Quah Reference Quah1999, 2013; Fritzen Reference Fritzen2005; Chang and Golden Reference Chang and Golden2010; Hollyer and Wantchekon Reference Hollyer and Wantchekon2015). The within-country approach applied in this study allows for considering various novel drivers of corruption that country-level studies are not able to capture, thereby adding new insights to these streams of research.

Secondly, the present article also contributes to the rapidly growing body of literature concerned with various aspects of the recent wave of democratic decline and emerging hybrid regimes (Cianetti et al. Reference Cianetti, Dawson and Hanley2018; Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019; Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2020; Diamond Reference Diamond2021; Guriev and Treisman Reference Guriev and Treisman2022) by considering the crucial, but so far relatively neglected role of corruption in the emergence and maintenance of competitive authoritarian (and other, similar) regimes. Similarly, Cianetti et al. (Reference Cianetti, Dawson and Hanley2018) argued that there is a need to move away from narrowly institutionalist approaches in research on de-democratisation and “to better integrate the role of illiberal socio-economic structures such as oligarchical structures or corrupt networks” (Cianetti et al. Reference Cianetti, Dawson and Hanley2018: 243).

The article is organised as follows. In Sect. “Conceptual and theoretical review”, the relevant streams of research are briefly reviewed. In Sect. “Conceptualising corruption types and patterns”, the outcomes of interest (types and patterns of corruption) are conceptualised. In Sect. “Net gains from corruption”, the explanatory framework of net gains from corruption is described. In Sect. “The framework in practice: two cases from Hungary”, two case studies are presented to demonstrate the pertinence of the framework. In Sect. “Discussion”, some key questions regarding the framework are discussed. Finally, Sect. “Summary and conclusions” offers a summary and concluding remarks.

Conceptual and theoretical review

Corruption: quantitative or qualitative differences?

The appearance of corruption indices with broad temporal and geographical coverage (e.g. Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, the Word Bank’s Control of Corruption indicator, and various corruption indices of the Varieties of Democracy project) has resulted in a surge in cross-national large-n studies of corruption (for reviews, see Lambsdorff Reference Lambsdorff and Rose-Ackerman2007; Dimant and Tosato Reference Dimant and Tosato2018). These studies have significantly enhanced comprehension of the country-level patterns, drivers, and effects of corruption. However, the majority of these studies—often implicitly—apply a unidimensional approach to corruption assuming that corrupt acts are relatively homogenous (Graycar Reference Graycar2015; Andersson Reference Andersson2017; Ang Reference Ang2020b) and that corruption varies among countries in terms of quantity, rather than quality (Johnston 2006).

This problem has caught the attention of many students of corruption. Some scholars have taken on to delineate different corruption patterns at the country level (e.g. Johnston 2006; Mungiu-Pippidi Reference Mungiu-Pippidi2006; Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2008). Others have sought to discern different forms of corruption. The most salient distinction lies between petty and grand corruption. Petty corruption refers to smaller bribes typically paid by citizens to low-level bureaucrats, whereas grand corruption involves a systematic and large-scale appropriation of public goods by high-level state officials (Rose-Ackerman and Palifka Reference Rose-Ackerman and Palifka2016). Graycar’s (Reference Graycar2015) more nuanced classification framework identified types of actions (e.g. bribery, extortion), activities (e.g. procurement, appointing personnel), sectors (e.g. construction, energy), and places (e.g. countries, regions).

Regime types

Corruption manifests in diverse forms and is driven by distinct factors across different political regimes (Johnston 2006). To analyse such regime-dependent factors, it is necessary to establish a broad typology of political regimes. In line with the influential multi-dimensional approach to democracy, the latter is defined as a political regime which consists of five interrelated constituent elements: democratic election, political participation rights, civil rights, horizontal accountability, and effective power to govern (Merkel Reference Merkel2004). At the other end of the spectrum, (closed) autocracy is defined as a regime in which ‘the chief executive is not subjected to de jure multiparty elections’ (Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019: 1109). Finally, the encompassing term hybrid regime denotes the grey zone between autocracy and democracy (Wigell Reference Wigell2008). Hybrid regimes are diminished forms of authoritarianism or democracy and share certain features of both ideal types (Bogaards Reference Bogaards2009).

This article focuses on corruption in competitive authoritarian regimes. Competitive authoritarianism is a particular type of hybrid regime ‘in which the coexistence of meaningful democratic institutions and serious incumbent abuse yields electoral competition that is real but unfair’ (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2020: 51). Competitive authoritarianism has been increasingly prevalent worldwide (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2020; Diamond Reference Diamond2021; Guriev and Treisman Reference Guriev and Treisman2022). Although some analysts have argued that such regimes have an inherent transitional character, and converge either towards democracy or autocracy (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2013), it appears that they have certain socio-political anchors that may stabilise them, at least over the medium run (Guriev and Treisman Reference Guriev and Treisman2022). Unlike some other types of hybrid regimes, in competitive authoritarianism political power is centralised, and the government is relatively free to implement policies and use the state apparatus for their own goals. However, unlike in fully authoritarian contexts, governments in competitive authoritarian settings face significant constraints both in domestic and international arenas (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2002, Reference Levitsky and Way2020; Guriev and Treisman Reference Guriev and Treisman2022).

Corruption in competitive authoritarian settings

Both empirical (Rock Reference Rock2009; McMann et al. Reference McMann2020) and theoretical (Mungiu-Pippidi Reference Mungiu-Pippidi2006) accounts underpin that democracy and corruption exhibit an inverted curvilinear relationship. In fully authoritarian settings, the regime enjoys a nearly uncontested power monopoly. It can seize public assets at will and has little incentive to share the gains by allowing other groups to benefit from corruption. Therefore, while corruption is pervasive, it typically remains limited to areas that directly benefit the ruling elite. In democracies, the presence of formal and informal institutions that uphold public integrity and accountability contributes to the attainment of the lowest levels of corruption. In hybrid regimes (including competitive authoritarian ones), the ruling elite’s power monopoly is challenged but accountability institutions are not fully in place, which makes way for higher levels of corruption.

However, while by and large, competitive authoritarian (and in a broader sense, hybrid) regimes are the most prone to corruption, a closer examination sheds light on interesting patterns: the prevalence of different corruption types varies largely in such contexts. Evidence shows that some forms of petty corruption are effectively curbed by such regimes (Hollyer and Wantchekon Reference Hollyer and Wantchekon2015; Ang Reference Ang2020a; Ligeti et al. 2020; Rochlitz et al. Reference Rochlitz, Kazun and Yakovlev2020).

By contrast, grand corruption typically flourishes in competitive authoritarian settings (McMann et al. Reference McMann2020), often to an extent characterised by state capture, whereby (a large share of) state institutions are captured by the ruling elites and laws and policies are formulated to their benefit (Hellman et al. Reference Hellman, Jones and Kaufmann2003), rather than to pursue the public interest. State capture may occur through influencing law and policy making, influencing policy implementation and/or disabling accountability institutions (Dávid-Barrett Reference Dávid-Barrett2023). As such, state capture may play a crucial role in maintaining political power. Yet, competitive authoritarian rulers are not always keen to (fully) capture the state: Singapore, for instance, has been effective in curbing not only petty but also grand corruption (Quah Reference Quah1999; Abdulai Reference Abdulai2009).

What factors may explain these counterintuitive outcomes? Although country-level studies are of limited use when it comes to describing and explaining within-country corruption patterns, some insights may still be applicable to the latter ambition. Firstly, many studies have analysed how institutions and actors may constrain corruption (for a review see Dimant and Tosato Reference Dimant and Tosato2018). Secondly, some contributions have focused on corruption in hybrid and authoritarian settings specifically, analysing the role of ideological commitment (Hollyer and Wantchekon Reference Hollyer and Wantchekon2015), the time horizon and the type (i.e. personalistic or single-party) of the regime (Chang and Golden Reference Chang and Golden2010), and political will for anti-corruption measures (Quah Reference Quah1999; Fritzen Reference Fritzen2005; Abdulai Reference Abdulai2009) as drivers of corruption. A few other contributions have sought to describe and/or explain different patterns of corruption (e.g. Johnston 2006; Mungiu-Pippidi Reference Mungiu-Pippidi2006) and state capture (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2008; Innes 2014) in various contexts, including competitive authoritarianism.

Conceptualising corruption types and patterns

Although the literature briefly reviewed in Sect. “Corruption in competitive authoritarian settings” puts forward valuable insights that may contribute to describing and explaining within-country corruption outcomes in competitive authoritarianism, the country-level approach applied by the majority of these contributions is not well suited for the present purposes. A few studies considered different forms of corruption within countries (e.g. Ang Reference Ang2020a, Reference Ang2020b; Johnston 2006; Mungiu-Pippidi Reference Mungiu-Pippidi2006), but they did not seek to decompose country-level patterns into constituent elements systematically and applied a primarily country-level perspective.

Shifting the level of analysis downwards, I propose a novel approach to studying countries’ corruption patterns by conceptualising it as the ensemble of different corruption types. Corruption types are defined based on two dimensions of Graycar’s (Reference Graycar2015) classification framework, denoting sets of corrupt transactions that are relatively similar in terms of the specific actions involved (e.g. bribery, clientelism, nepotism, extortion), and the sector in which they occur (e.g. construction, retail, healthcare, customs and immigration, public administration). For instance, bribery in customs and immigration, and clientelism in public procurements constitute types of corruption. Arguably, in a given country and time, corrupt transactions within corruption types are relatively similar in terms of characteristics relevant to the present discussion (in particular, the costs and benefits they incur to the regime; see Sect. “Net gains from corruption”).

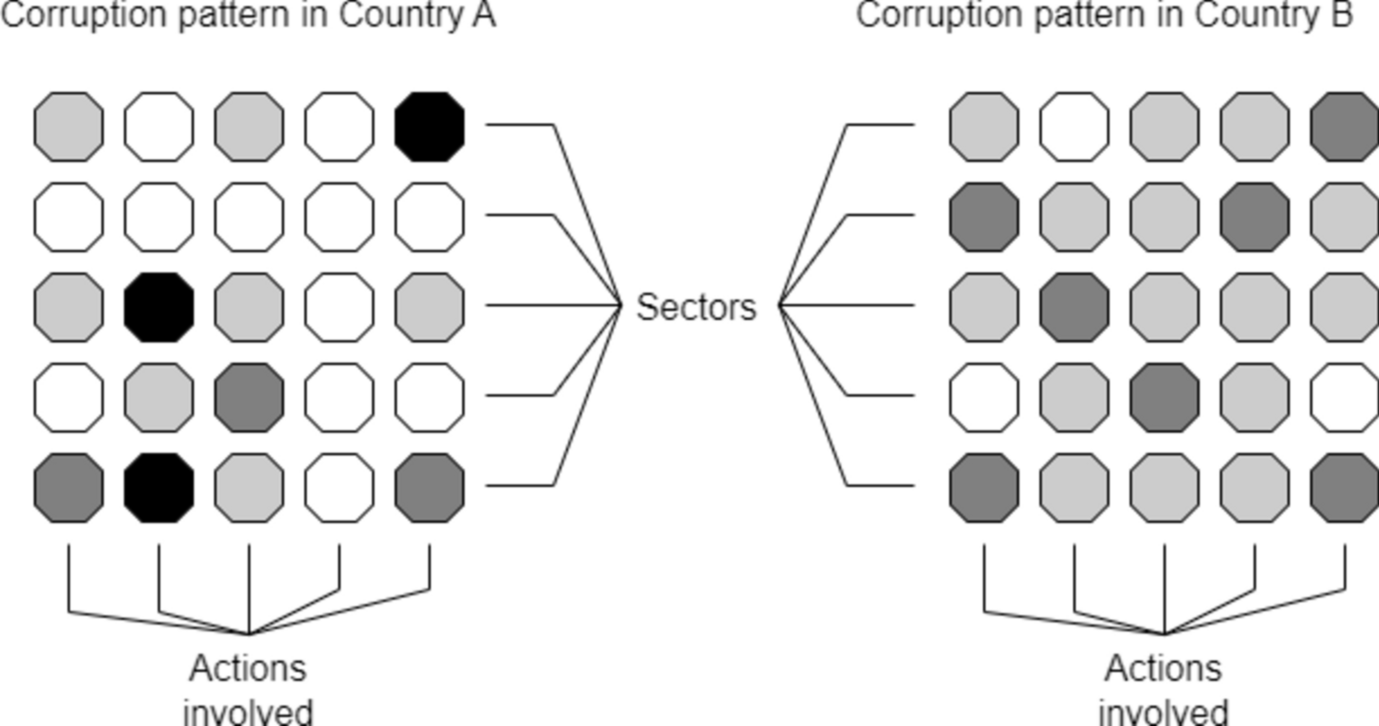

The schematic figure below illustrates the corruption patterns of two countries. In Country A, several corruption types are rampant, while a few others are very limited. In Country B, the majority of corruption types are present but moderate (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Illustrative examples of corruption patterns. Octagons represent types of corruption (e.g. bribery in police, clientelism in public procurement), and darker shades indicate that the given type of corruption is more common.

Net gains from corruption

What explains patterns of corruption in competitive authoritarian regimes? Broad evidence supports that political will for anti-corruption efforts (Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2000) is a vital—potentially necessary and sufficient —condition of successful anti-corruption interventions in non-democratic settings (Fritzen Reference Fritzen2005; Abdulai Reference Abdulai2009; Ristei Reference Ristei2010; Quah 2013). As I argued in Sect. “Conceptual and theoretical review”, competitive authoritarian regimes may effectively curb certain types of corruption while enabling others. This implies that such regimes’ will to curb corruption varies significantly across corruption types. What may explain this variance?

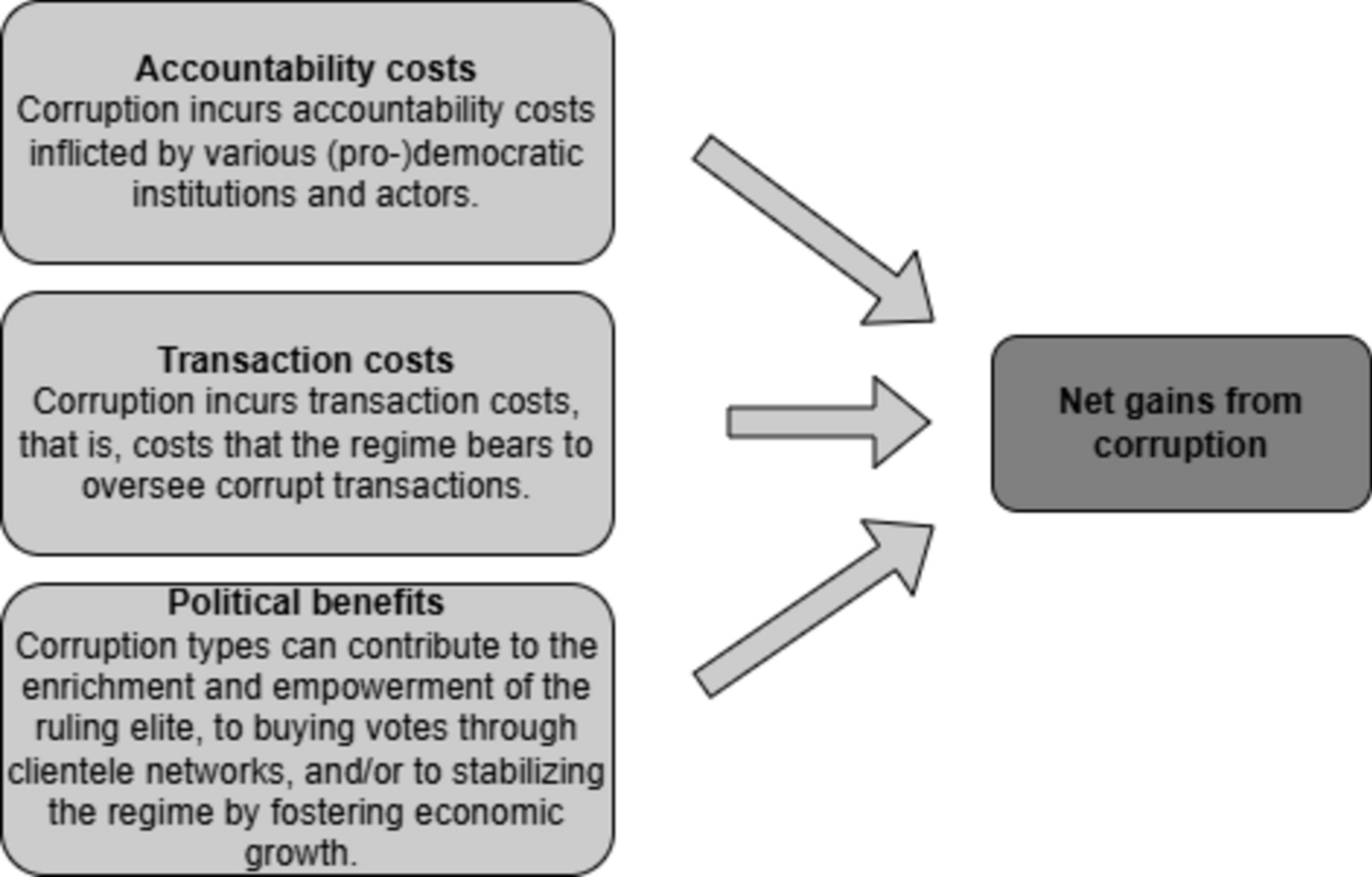

Put simply, the influential institutional economist approach to corruption (Becker and Stigler Reference Becker and Stigler1974; Rose-Ackerman Reference Rose-Ackerman1975; Klitgaard Reference Klitgaard1988; Rose-Ackerman and Palifka Reference Rose-Ackerman and Palifka2016) assumes that corrupt actors are rational utility-maximisers who engage in corruption if it is profitable to them. The profitability is determined by the incentives created by the institutions in which the actors operate. Building on this approach, I posit that competitive authoritarian regimes assess and weigh the costs and benefits—that is, the net gains—associated with different corruption types and curb or enable them based on this calculation. The costs and benefits are influenced by various intervening factors, falling under the following broad categories: accountability costs, transaction costs, and political benefits (McMann et al. Reference McMann2020). In the following three subsections, I discuss these in detail.

The model applied in the present article differs from the classical institutional economics approach in two main aspects. Firstly, in contrast to the traditional model which considers individuals, here the focal actor is the regime itself, presumed to be a rational and unitary agent. Secondly, the net gains of corruption arising on the regime’s part are considered at the level of distinct corruption types, rather than for corruption in general.

Accountability costs

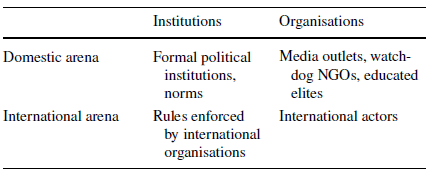

Accountability costs refer to punishments inflicted by democratic institutions and pro-democratic actors vis-á-vis the government and are influenced by various factors. To enumerate these factors, I use the metaphor of North (Reference North1990), who argued that institutions (including laws, regulations, and norms) can be thought of as the rules of the game, whereas organisations are players in the game. Both institutions and organisations (and in a broader sense, actors) may inflict accountability costs that regimes must bear for corruption. Notably, while the distinction between institutions and actors is sometimes blurred, it is useful to discern them theoretically. Accountability costs inflicted by institutions are incurred in a mechanistic manner, often in the form of binding rules or shared norms; by contrast, in the case of accountability costs inflicted by actors, the agency of particular persons and organisations plays an important role. It is also useful to discern the domestic and the international arenas. These dimensions delineate four potential sources of accountability costs (Table 1).

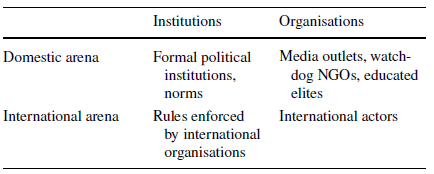

Table 1 The four factors influencing accountability costs of corruption types.

Source created by author

Firstly, formal political institutions, such as elections, political and civil rights, and independent legislatures and courts, strongly influence accountability costs associated with corruption types.Footnote 1 Arguably, these institutions may incur varying costs for different types of corruption. For instance, independent legislatures may only constitute constraints for those types of corruption for which they possess a legal mandate to intervene. Whilst competitive authoritarianism is characterised by diminished democratic institutions, these institutions are nonetheless present to some extent and may act as constraints on the regime’s power (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2002; Guriev and Treisman Reference Guriev and Treisman2022). Informal institutions, or norms, also matter. Societies are characterised by a level of permissiveness towards corruption in general (Lavena Reference Lavena2013) and also hold beliefs about the moral acceptability of distinct types of corruption. For instance, people may be indulgent concerning bribing bureaucrats but largely condemn extortion in education.

Secondly, still within the domestic arena, organisations and actors also influence accountability costs. Shifting from the neo-institutionalist perspective, some recent contributions have emphasised the role of actors who inhabit institutions (e.g. Voronov and Weber Reference Voronov and Weber2020). In the context of competitive authoritarianism, Guriev and Treisman (Reference Guriev and Treisman2022) argue that well-informed, educated elites may effectively oppose the government. Furthermore, other pro-democratic actors and organisations, such as independent media outlets (Bhattacharyya and Hodler Reference Bhattacharyya and Hodler2015) and civil organisations (Treisman Reference Treisman2000), may also exert significant pressure on the government and thereby influence the accountability costs of corruption.

Thirdly, accountability costs are also shaped by binding rules imposed by international and intergovernmental organisations. For instance, the EU has specific rules about how member states can access and spend EU funds (White Reference White2010). The European Anti-Fraud Office also has a mandate to investigate cases that involve suspicions of fraud. For example, in response to allegations of extensive clientelism in the allocation of EU funds, in 2022 the European Commission initiated a rule of law procedure against Hungary, which lead to the withholding of a substantial portion of the EU funds that the country was entitled to receive (Stevis-Gridneff et al. 2022).

Fourthly, international actors may also influence accountability costs by incentivising the implementation of provisions enhancing accountability through various formal and informal means, such as conditional aid. In the frame of the European Neighbourhood Policy, for instance, the EU pressured neighbouring countries to implement various pro-democratic measures, including some that promote accountability and transparency (Lavenex and Schimmelfennig Reference Lavenex and Schimmelfennig2011). The EU also pressed prospective members to implement anti-corruption measures (Kartal Reference Kartal2014; Ristei Reference Ristei2010).

Notably, competitive authoritarian regimes may seek to lower accountability costs through various ways. For instance, such regimes often fuel political polarisation and partisan sentiment to reduce electoral retribution for corruption (Hajnal Reference Hajnal2024). They may take measures to discredit independent civil organisations, critical media outlets, and international organisations involved in anti-corruption. Finally, they can dismantle and undermine formal accountability institutions, such as the judiciary.

In some instances, the discussed factors may influence overall accountability costs independently from one another. In other cases, they interact. For instance, competitive authoritarian regimes may have relatively well-elaborated legal anti-corruption frameworks and powerful anti-corruption bodies. However, in the absence of more general accountability institutions, these tools are either futile or applied by the regime to harass the opposition and other critics. The case of Ukraine also illustrates the above point. Under the leadership of Petro Poroshenko, the country implemented comprehensive anti-corruption legislation. However, weak accountability institutions, including the National Anti-Corruption Bureau and the Specialised Anti-Corruption Prosecutor's Office, hindered the proper functioning of these laws. The judiciary, plagued by corruption and inefficiency, further compromised anti-corruption efforts. In sum, despite the presence of anti-corruption measures, accountability costs generally remained low (Freedom House 2018; Kramer 2020).

Transaction costs

Transaction costs of corruption in general terms are defined as ‘the costs of searching for partners, determining contract conditions, and enforcing contract terms’ (Lambsdorff Reference Lambsdorff2002: 221). Adopting the concept to the present framework, I use the term to refer to costs that the government must bear to oversee (sets of) corrupt transactions to manipulate resource allocation through corruption.

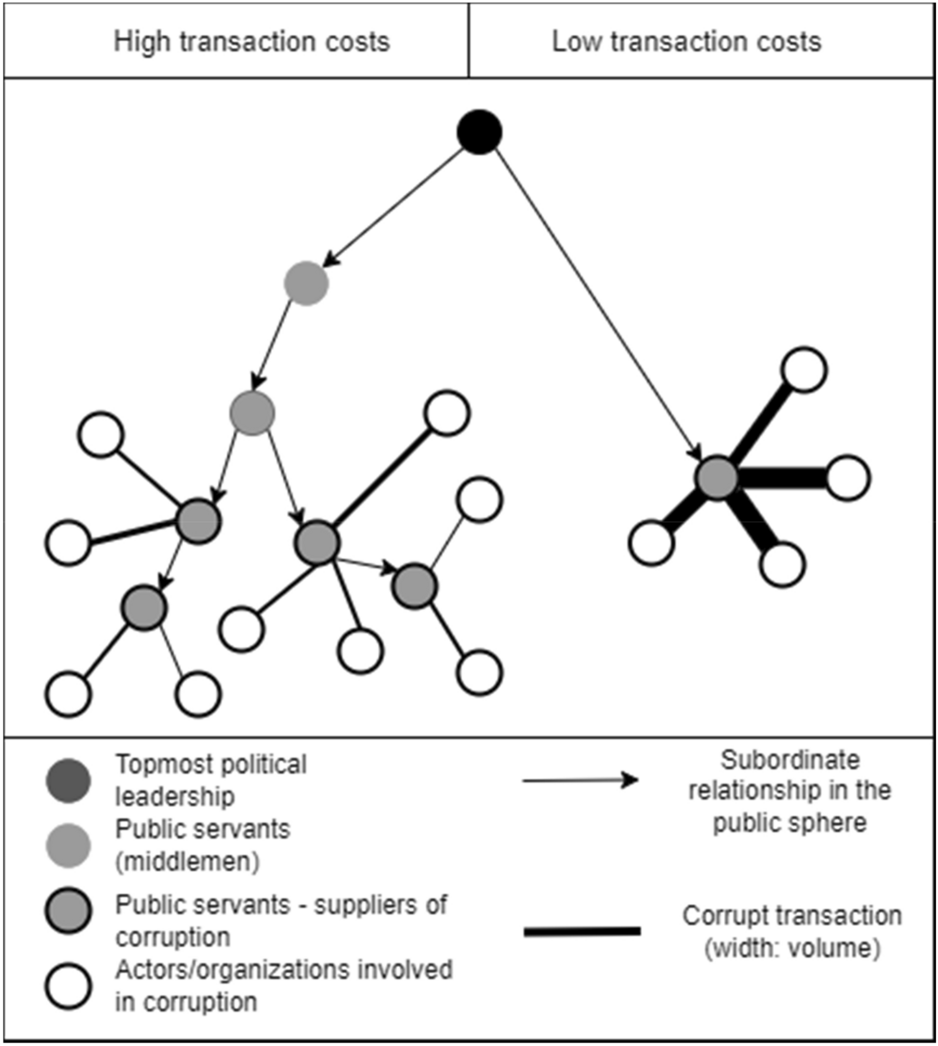

I propose that transaction costs of corruption depend on two characteristics of corrupt transactions. Firstly, they are influenced by the distance between the supplier of corruption (i.e. the public official who abuses their position) and the topmost political leadership in the hierarchical structure. Arguably, involving more middlemen increases transaction costs. Secondly, transaction costs depend on the average volume of corrupt transactions: it is less costly to oversee (sets of) transactions if the average volume of single transactions is high. Notably, transactions are not necessarily monetary but may involve the exchange of other assets (e.g. jobs, concessions, permits, etc.). The figure below illustrates two corruption types, one with high, and another with low transaction costs (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Examples of corruption types with high or low vertical transaction costs.

For instance, in the case of clientelism in infrastructure procurement, transaction costs are typically low: suppliers of corruption, that is, public procurement agencies, are close to the chief executive in the hierarchy, whereas the average volume of transactions is high, as infrastructure procurement contracts typically involve relatively large amounts of money. By contrast, low-level bribery in the police constitutes an example of high transaction costs corruption types: (potentially) corrupt police officers are relatively far from the topmost political leadership, whereas bribes are low.

Political benefits

The previous two subsections focused on the costs that regimes must bear for enabling or practising different types of corruption. On the other side of the balance, corruption types may also yield political benefits for the regime through one or more of the following three ways.

Firstly, corruption may directly contribute to the enrichment and empowerment of the ruling elites. Nepotism and favouritism in public procurement, for instance, allow for the establishment of large business empires overseen by the topmost leadership and their inner circles. Such conglomerates grant elites economic leverage, which in turn yields more political power (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2013). One widespread mechanism through which this may happen involves funnelling corrupt gains seized through public contracting into party and campaign finance. Notably, a similar mechanism is also prevalent in democracies, whereby business organisations buy political influence in exchange for party donations (Johnston 2006, chap. 4; the main difference being the distinction between business and political elites). In a similar vein, certain types of corruption may lead to the empowerment of the ruling elite by enabling them to take control over legislation and/or policymaking and implementation in certain areas and utilise it to pursue their own purposes, that is, capture the state (Dávid-Barrett Reference Dávid-Barrett2023). For instance, extortion in commerce regulation agencies may allow ruling elites to create an uneven playing field favouring politically aligned enterprises.

Secondly, certain corruption types may contribute to clientelist vote-buying through machine politics (Hicken Reference Hicken2011; Gans-Morse et al. Reference Gans-Morse, Mazzuca and Nichter2014; Nichter Reference Nichter2014). Ruling elites may apply corruption to trade particularistic benefits in exchange for political support. While vote-buying may occur through simple exchanges of votes and money/goods, it often involves establishing and maintaining clientelistic networks for longer periods. These networks financially depend on the regime and are therefore poised to support it. For instance, public sector jobs may be awarded in a particularistic manner, in exchange for maintained political support, rather than merit, as was the case in Argentina (Auyero Reference Auyero2012). Clientelistic networks may also be sustained by granting concessions in lucrative state-controlled sectors (see Sect. “The framework in practice: two cases from Hungary”, Case B) to politically aligned businesses and individuals. Such corrupt transactions involving ‘unjustified restriction of access to public contracts to favour a certain bidder’ (Fazekas Reference Fazekas2017, p. 405) are referred to as political favouritism. Regional favouritism constitutes a specific type of the latter, whereby the regime favours politically aligned sub-governmental entities (i.e. regions and municipalities; for a review, see (Reszkető, Váradi and Hajnal, 2022). Similarly, corruption may also be used to co-opt potentially critical interest groups (Guriev and Treisman Reference Guriev and Treisman2022).

Thirdly, certain corruption types may also yield political benefits by boosting economic growth and thereby stabilising the regime. Most corruption types yield adverse economic effects, but some types favour growth: so-called ‘access money’ involves bribes paid by large corporations to politicians, allowing them to deregulate markets, win contracts, and access other privileges. In an analogy with drugs, access money is similar to steroids, in that it produces long-term adverse effects (e.g. distorted competition, higher inequality), but boosts the performance of involved corporations and hence contributes to economic growth (Ang Reference Ang2020b). Economic growth yields political benefits for competitive authoritarian regimes as it can enhance stability. Ang (Reference Ang2020a) argues that the combination of the predominance of performance-boosting types of corruption and—mitigating its adverse effects—large-scale redistributive policies enabled China a high growth rate and relative stability over the past decades. Notably, the three presented sources of political benefits are not mutually exclusive; certain types of corruption may yield more than one type of political benefit. The presented explanatory framework is summarised in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3 Summary of the explanatory framework.

The framework in practice: two cases from Hungary

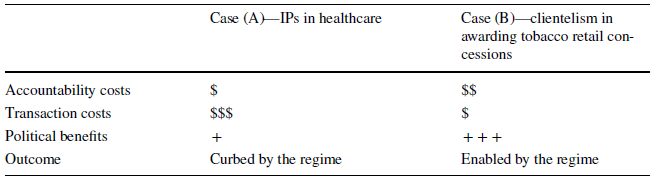

To demonstrate the applicability of the explanatory framework, I applied it to assess the net gains associated with two corruption cases (belonging to two distinct corruption types) in Hungary: informal payments in healthcare (case A) is a particular manifestation of bribery in public services, whereas clientelism in awarding tobacco retail concessions (case B) is a case of clientelism in regulation. Having experienced severe and rapid de-democratisation since the election victory of Viktor Orbán’s coalition in 2010 (Bogaards Reference Bogaards2018), Hungary can be considered an exemplary case of competitive authoritarianism. While Orbán’s regime is characterised by highly centralised and thriving grand corruption (which has played a key role in consolidating and maintaining the regime; Fazekas and Tóth Reference Fazekas and Tóth2016; Magyar Reference Magyar2016), certain forms of petty corruption were effectively curbed. Using the framework, I compared the net gains associated with the two corruption cases in terms of the presented categories of costs and benefits. This exercise is intended for illustrative purposes (i.e. to demonstrate the empirical applicability of the framework) rather than as solid empirical proof. Table 2 presents the comparison of the two cases.

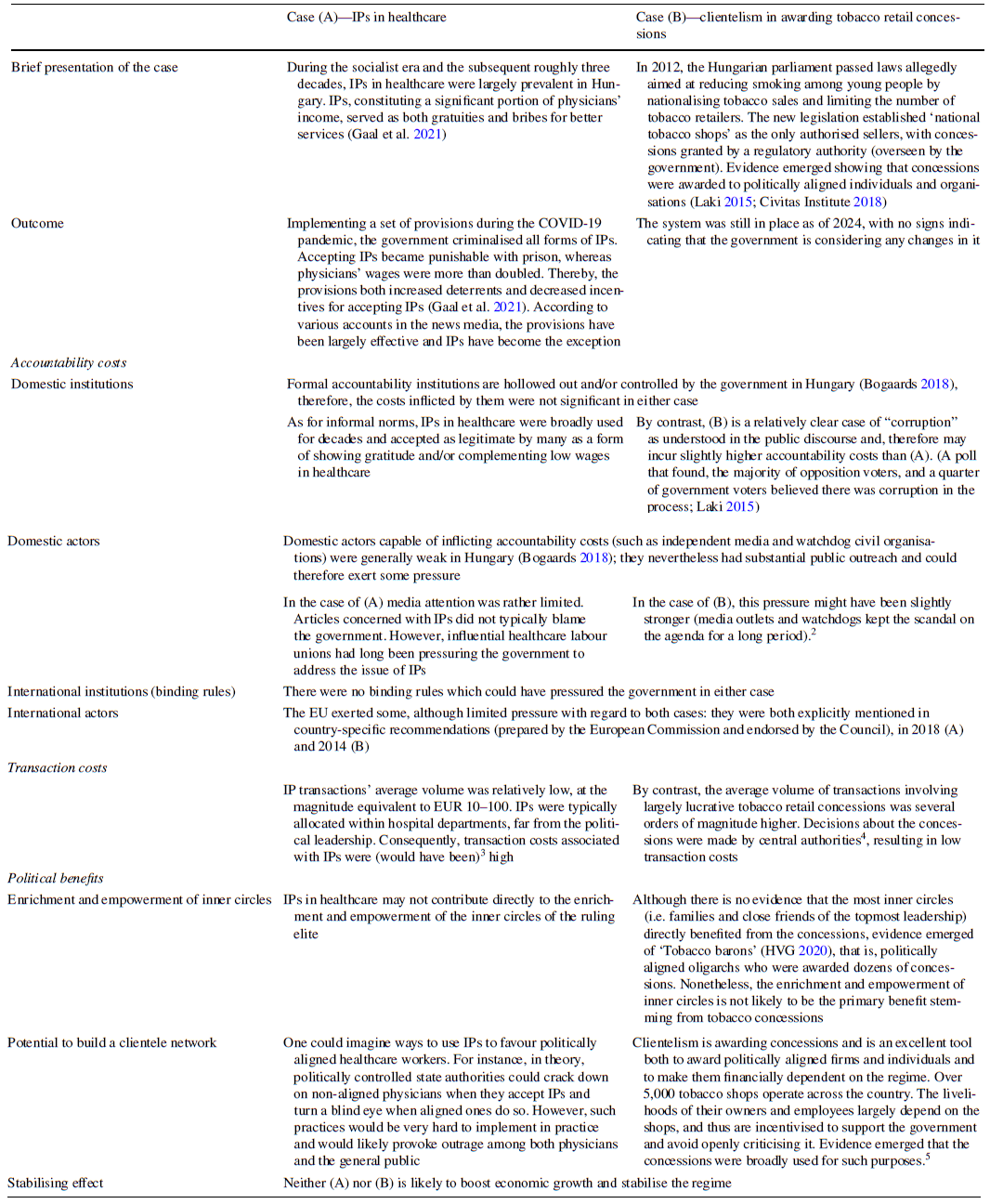

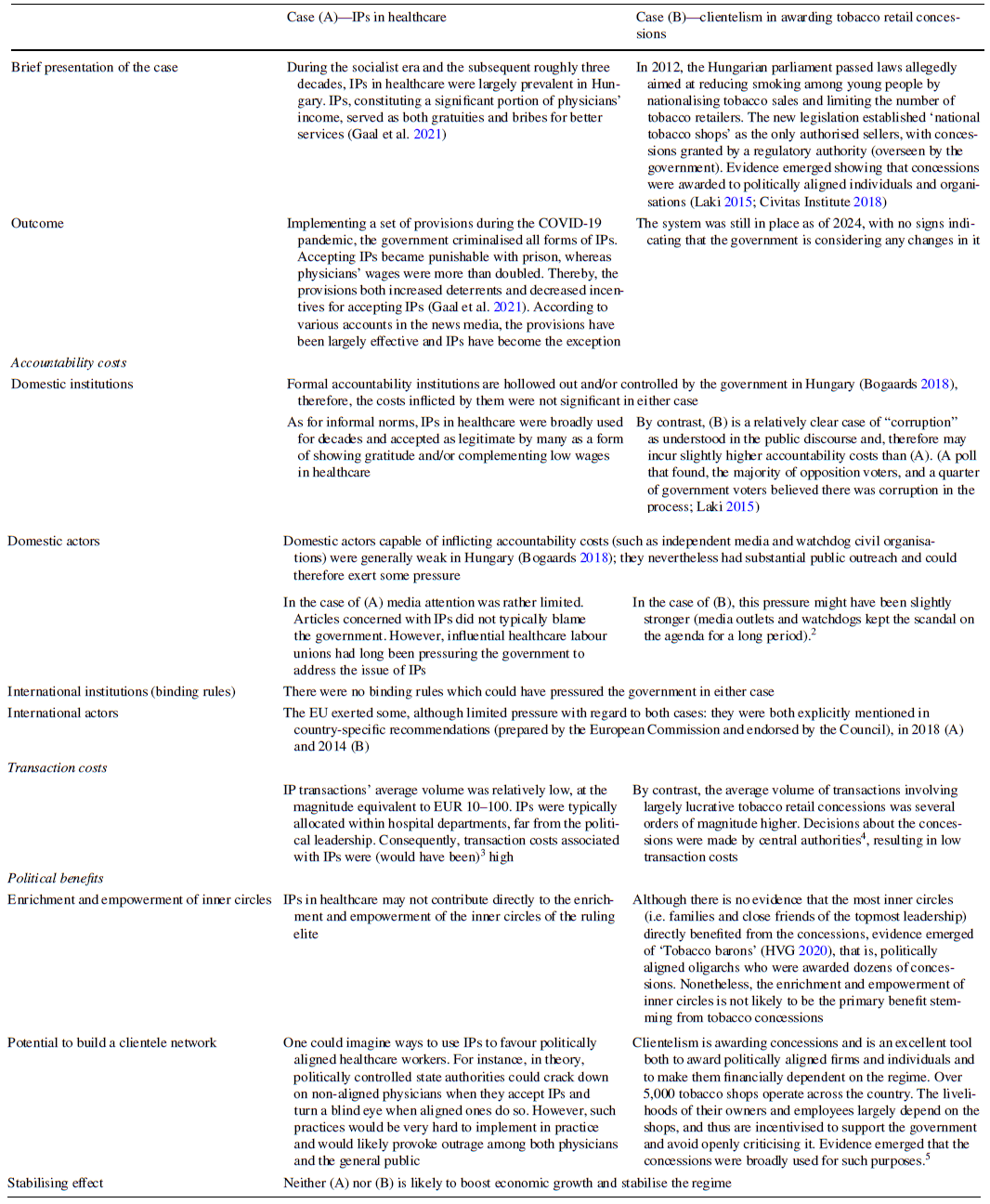

Table 2 Analysis of the two cases on the basis of the presented framework.

2According to the searchable database of news articles concerned with corruption in Hungary (k-monitor.hu), almost 400 articles have appeared about clientelism in tobacco retail. Less than half of those discussed IPs in healthcare (up until the point it was curbed), with the majority of these articles not explicitly blaming the government

3There is no evidence that the allocation of IPs was centrally controlled

4Until 2022, the National Tobacco Retail Non-Profit Ltd., after 2022, the Prime Minister’s Office was in charge

5An opposition member of parliament noticed that the properties of the word processor file for the draft of the act (which was also shared with the Commission) indicated that the document was edited by János Sánta, the owner and manager of Continental Tobacco Corporation and a close friend of János Lázár, the head of the Prime Minister’s Office at the time. Later, more than 500 concessions were granted to people with close ties to Continental Tobacco Corporation. Moreover, in a leaked voice recording, a mayor from the governing block contended that ‘the important thing is that [the bid winners] should be devoted rightists’ (Laki, 2015; Civitas Institute, 2018)

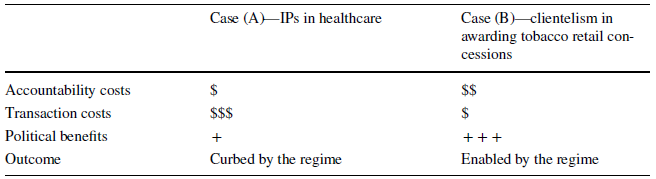

Table 3 summarises the broad results of the assessment. Case (B) outperforms type (A) in terms of net gains: although (B) incurred slightly higher accountability costs, the transaction costs were higher in the case of (A), and, most importantly, (B) yielded substantial political benefits, in contrast to (A). In line with these findings and the expectations derived from the presented model, the regime abolished IPs in healthcare, whereas clientelism in tobacco retail remains largely prevalent.

Table 3 Summary of costs and benefits associated with the two cases (Legend: + : limited/no benefits; + + : moderate benefits; + + + : substantial benefits; $: limited/no costs; $$: moderate costs; $$$: substantial costs).

Source created by author

Discussion

The two case studies demonstrated the empirical applicability of the presented framework. Firstly, although the assessment of the costs and benefits is not based on soundly operationalised variables, it is still feasible by conducting a thorough qualitative analysis. Secondly, the findings are also consistent with the focal assertation of the explanatory framework, that is, competitive authoritarians curb corruption types which yield low net gains for them, and enable those which yield high net gains.

How do net gains vary across corruption types identified by other, extant corruption typologies? One may argue that petty corruption is associated with low net gains, whereas grand corruption is associated with high net gains. On the one hand, the presented framework underpins this general pattern: by and large, petty types of corruption tend to have lower overall net gains as their transaction costs are typically high, whereas their potential political benefits are low. On the other hand, the framework also shows that this is not necessarily the case. For instance, some petty corruption types may be associated with high political benefits.

The latter point is illustrated by the following example. Eduard Shevardnadze, the president of Georgia from the collapse of the USSR until the Rose Revolution, implemented several measures that encouraged certain types of petty corruption. Provisions stipulated that cab drivers had to show up for a medical check-up every day. Impossible to comply with, this provision incentivised both cab drivers and public bureaucrats to engage in corruption. Arguably, this measure was primarily motivated by the high political benefits of this corruption type: involved actors were made vulnerable by potential corruption charges and were thereby less likely to oppose the regime (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2019, chp. 4).

Another important question regarding the framework concerns its applicability in other-than-competitive authoritarian contexts. Although some of the presented factors also influence corruption in other institutional settings, the framework as a whole is only applicable in the context of competitive authoritarianism. For instance, in fully autocratic settings accountability costs are typically negligible; in weak and failing states, the presumption that corruption is determined by policies implemented by the government does not hold; whereas in democratic settings, corruption is a deviation, not an instrument to maintain and consolidate power (Johnston 2006); therefore, it would be largely exaggerated to claim that the incumbent simply weighs the costs and benefits of corruption types and curb or enable them accordingly. In other types of hybrid regimes, the framework may be applicable, in cases where the given regime type resembles competitive authoritarianism in key aspects.

Finally, it is important to discuss the implications of the well-documented reverse causal relationship between democracy and corruption (Drapalova et al., 2019) concerning the presented framework. Put simply, democratic institutions are supposed to hold the government accountable. If these institutions deteriorate, potentially corrupt actors face fewer constraints, which leads to increased levels of corruption. In turn, as outlined in Sect. “Political benefits”., corruption may be used as a tool to undermine democratic political competition (e.g. by buying political support). Although this pattern does not undermine or contradict the explanatory framework, the association between accountability costs of corruption types (in particular, accountability costs inflicted by domestic actors and institutions) and the prevalence of corruption types may involve reverse causality.

Summary and conclusions

Although competitive authoritarian countries are particularly prone to corruption, regimes in such contexts often take measures against certain types of corruption. To account for these variations, first, a novel level of analysis is proposed, namely corruption types. The article posits that competitive authoritarian regimes decide to curb or enable corruption types based on a rational calculation considering the costs and benefits—that is, the net gains—associated with different types of corruption. The article presents an explanatory framework which sheds light on various factors that influence these costs and benefits. The applicability of the framework is demonstrated with case studies about two corruption cases in Hungary: IPs in healthcare and clientelism in awarding tobacco retail concessions.

The following main conclusions emerge. Firstly, shifting the level of analysis from the country-level to the within-country level opens up new avenues to study corruption and explain corruption outcomes. Secondly, the framework showcases the multiplicity and complexity of the factors influencing corruption in competitive authoritarian settings. Academics, policymakers, and other actors seeking to take on corruption in such contexts should consider the multifaceted nature of corruption and the broad range of factors potentially influencing it. Thirdly, the analysis also underpins the importance of the institutional setting in the context of studying corruption: the large share of the costs and benefits discussed are not relevant in democratic or fully authoritarian contexts.

Future contributions could test the presented explanatory framework and put it to empirical use. Qualitative case studies may analyse the mechanisms through which the presented drivers interact and result (or not) in different corruption patterns. In the light of the complex causal interrelations of the constituent elements, set-theoretic methods may be particularly suitable for this purpose. Should sufficient data be available for this, large-n quantitative studies could operationalise and measure some of the drivers discussed in the framework and assess whether they are associated with specific corruption outcomes. Furthermore, although the framework is extensive, it is far from exhaustive. Future studies may also complement it by adding novel drivers. Finally, one could enlarge the scope of the framework by considering other-than-competitive authoritarian regimes.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Corvinus University of Budapest.

Data Availability

No datasets are analysed or generated, as the work proceeds within a theoretical approach.

Data availability

The author confirms that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Declarations

Competing interests

The author has no conflict of interest to report.