1. Introduction

The deleterious consequences of overconfidence have been well documented (e.g., Bazerman and Moore, Reference Bazerman and Moore2013). Hence, limiting or reducing overconfidence is desirable. Because overconfidence has multiple causes, understanding the antecedents of any specific form of overconfidence may present a path to its reduction (Moore, Reference Moore2023). In our empirical work, we focus on a generally unrecognized source of overconfidence that is embedded in the decision process itself.

During a decision, predecisional distortion of information can operate to create unwarranted confidence in the selected option. The distortion bias occurs when new information is judged as more supportive of a currently favored alternative than is justified by the nature of the information itself. The phenomenon of distortion-driven confidence at the decision level has been demonstrated in a study of one group of decision makers often characterized as particularly overconfident, entrepreneurs (Boyle et al., Reference Boyle, Russo and Kim2025). In that study, entrepreneurs were tasked with deciding whether or not to launch a venture, with relevant information presented sequentially. Tracking their levels of confidence and information distortion throughout their decisions revealed not only how confidence escalated during the decision process but also how overconfidence emerged because of that process.

Entrepreneurs were studied because of their recognized propensity for overconfidence (Busenitz, Reference Busenitz1999; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Woo and Dunkelberg1988). For example, entrepreneurs have been found to be more overconfident than managers in large organizations (Busenitz and Barney, Reference Busenitz and Barney1997). Although their overconfidence is considered a stable individual trait (e.g., Forbes, Reference Forbes2005; Pirinsky, Reference Pirinsky2013), the findings of Boyle et al. (Reference Boyle, Russo and Kim2025) suggest that at least some of the overconfidence they exhibit may be distortion-driven. This prompts the question: Does the phenomenon of distortion-driven confidence extend more generally to other types of decision makers engaged in a different type of decision task? In most cases, entrepreneurs can be assumed to have a pre-existing preferred outcome (namely, to launch their venture), so the decisions of entrepreneurs may not be entirely representative of more customary business decisions, ones in which managers may be initially agnostic or uncertain about the outcome.

In the present work, a study of the effect of the distortion bias on confidence was undertaken with MBA students having prior business experience who engaged in a typical business-management decision. The primary goal was to determine if the same relationship between distortion and confidence observed in entrepreneurs would also emerge in a non-entrepreneurial business decision if a preferred course of action developed naturally. A positive outcome to this inquiry would further support the phenomenon of distortion-driven overconfidence more generally. A secondary objective was to test if two psychometric scales (need for cognition and tolerance for ambiguity) might correlate with any such overconfidence.

1.1. Overconfidence

While unwarranted confidence is commonly ascribed to entrepreneurs, there is considerable evidence for the presence of overconfidence in many business and other decisions (e.g., Chochoiek et al., Reference Chochoiek, Huber and Sloof2024; Meikle et al., Reference Meikle, Tenney and Moore2016). Indeed, overconfidence has been described as the most common of biases (see, e.g., Bazerman and Moore, Reference Bazerman and Moore2013; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Tenney and Haran2015; Plous, Reference Plous1993). It has been observed across a wide range of mundane and consequential judgments and decisions in its various forms (e.g., Moore and Healy, Reference Moore and Healy2008). Despite its prevalence, overconfidence is not well understood, especially the form of it that leads to an excessive faith in the quality of one’s judgment (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Carter and Yang2015) or confidence that the truth is known (Moore and Schatz, Reference Moore and Schatz2017). Mitigating overconfidence has proved challenging. For example, even in the presence of timely and clear objective feedback about past performance, overconfidence about future performance can persist (e.g., in store managers, Huffman et al., Reference Huffman, Raymond and Shvets2022; fund managers, Gaba et al., Reference Gaba, Lee, Meyer-Doyle and Zhao-Ding2023; athletes, Krawczyk and Wilamowski, Reference Krawczyk and Wilamowski2017; expert chess players, Heck et al., Reference Heck, Benjamin, Simons and Chabris2025).

Overconfidence is costly to society as a whole (e.g., Grubb, Reference Grubb2015; Odean, Reference Odean1998), as well as to individual decision makers, including professional ones. It results in firms introducing too many new products (Simon and Houghton, Reference Simon and Houghton2003) or the wrong ones (Feiler and Tong, Reference Feiler and Tong2022); stock traders misvaluing stocks (Adebambo and Yan, Reference Adebambo and Yan2018); and of course, entrepreneurs launching ventures injudiciously (Cain et al., Reference Cain, Moore and Haran2015; Invernizzi et al., Reference Invernizzi, Menozzi, Passarani, Patton and Viglia2017). There is little evidence that professional experience averts overconfidence (Ben-David et al., Reference Ben-David, Graham and Harvey2013; Campbell and Moore, Reference Campbell and Moore2024; Podbregar et al., Reference Podbregar, Voga, Krivec, Skale, Parežnik and Gabršček2001). CEOs and high-level executives, presumably with considerable business acumen, are susceptible to overconfidence when making judgments and forecasts (e.g., Chen et al., Reference Chen, Crossland and Luo2015; Ho et al., Reference Ho, Huang, Lin and Yen2016; Malmendier et al., Reference Malmendier, Tate and Yan2011). As Meikle et al. (Reference Meikle, Tenney and Moore2016) noted, beyond the realm of business decisions, the adverse effects of overconfidence may extend to fraud or serious conflict.

In pursuit of a deeper understanding of overconfidence, researchers have queried the causes of it (e.g., Li et al., Reference Li, Hale and Moore2025; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Carter and Yang2015; Moore, Reference Moore2023); whether it is as prevalent in the actual world of decisions as it is in the research literature (Meikle et al., Reference Meikle, Tenney and Moore2016); or if the magnitude of reported overconfidence might be overstated (Moore and Schatz, Reference Moore and Schatz2017). In the present work, our focus was less on the magnitude of overconfidence and more on how confidence developed during a decision as a consequence of a biased decision process involving the distorted interpretation of information. Accordingly, we traced the decision process of non-naive decision makers engaged in a realistic (although hypothetical) business task using methodologies previously developed to identify and assess information distortion and to track attendant decision confidence.

1.2. Information distortion

As with entrepreneurs, managers confronting important binary decisions receive some diagnostic information sequentially. As new information arrives serially over time, that additional information must be interpreted, specifically as to whether it favors one alternative course of action over the other. Hence, managers need to update their current understanding of the situation and possibly revise their preferences. Normatively, information judged as supporting a currently preferred action should strengthen that preference, while information judged as supporting an alternative action should weaken it. At least, from a Bayesian perspective, the strength of preference should be updated to reflect the full information inclusively (Russo, Reference Russo2018).

If new information is judged as more supportive of a leading alternative than is warranted by an objective assessment of the information itself, this biased interpretation constitutes information distortion. Such a bias can emerge whenever a desire for consistency operates. That is, a nonconscious goal of decision makers to view units of information as consistent with a current belief can predispose them to different interpretations of identical information, depending on whichever course of action is currently believed to be the leader (Russo et al., Reference Russo, Carlson, Meloy and Yong2008). Leaders tend to emerge spontaneously in decisions, as does a consistency goal (Russo et al., Reference Russo, Carlson, Meloy and Yong2008; Simon et al., Reference Simon, Pham, Le and Holyoak2001, Reference Simon, Krawczyk and Holyoak2004). Then, as new information is encountered during a decision, it is consolidated into a coherent decision process in which increased support is found for the option that is leading. This phenomenon, known as predecisional information distortion, is distinct from post-decision confirmatory actions (Russo et al., Reference Russo, Medvec and Meloy1996; see also DeKay, Reference DeKay2015, for an overview).

The phenomenon of predecisional information distortion, defined as the biased interpretation of new information to support a current leader, appears with regularity in studies of decision making (see also, Brownstein, Reference Brownstein2003; Holyoak and Simon, Reference Holyoak and Simon1999; Kostopoulou et al., Reference Kostopoulou, Russo, Keenan, Delaney and Douiri2012). The presence of it has been verified by numerous approaches. For example, in a study of boxing decisions (Tyszka and Wielochowski, Reference Tyszka and Wielochowski1991) judges assigned points (e.g., for punches landed) to two boxers over three rounds, with the order of rounds manipulated experimentally. Because boxers who had been seen in early rounds to be candidates for winning the overall match were awarded more points throughout the match, including in later rounds that they objectively lost, the difference in point totals served to indicate the bias.

In studies of legal decisions and others (Holyoak and Simon, Reference Holyoak and Simon1999; Simon et al., Reference Simon, Pham, Le and Holyoak2001, Reference Simon, Krawczyk and Holyoak2004), distortion was inferred from shifts in the evaluations of information from pre-decision to post-decision. Typically, in the context of a legal decision, participants evaluated a set of arguments, half of which objectively supported one verdict while the other half supported the opposite verdict. Holyoak and Simon (Reference Holyoak and Simon1999) reported that over the course of a decision individuals’ evaluations of such arguments shifted so as to lend stronger support to their final verdict. Whichever outcome was selected, post-choice the arguments were reinterpreted to align with it. Related studies, in which interim evaluations were also provided prior to the final decision, confirmed the presence of these shifts during the decision and not just after it (Simon et al., Reference Simon, Pham, Le and Holyoak2001, Reference Simon, Krawczyk and Holyoak2004).

To more clearly reveal bias taking place during a decision, Russo and colleagues (e.g., Carlson and Russo, Reference Carlson and Russo2001; Russo et al., Reference Russo, Meloy and Medvec1998) developed a ‘leader-signed’ measure of information distortion. With this method, distortion is judged as present whenever a unit of information is evaluated as supporting an action most likely to be the one finally selected (the ‘leader’) to a greater extent than is justified by the objective diagnostic value of the information itself. Although leader-signed distortion usually relates to the leading action, it is also possible to determine the degree of distortion not just pro (in favor of) the leading action but anti (against) the trailing actions (e.g., Blanchard et al., Reference Blanchard, Carlson and Meloy2014; DeKay et al., Reference DeKay, Miller, Schley and Erford2014; Nurek et al., Reference Nurek, Kostopoulou and Hagmayer2014). Although conceptually distinct, neither pro-leader nor anti-trailer distortion is normatively justifiable in the Bayesian calculus (Russo, Reference Russo2018).

Regardless of the methodology, the presence of information distortion in decisions has been reliably reported across multiple decision domains and multiple classes of decision makers, at least at the aggregate level (Russo, Reference Russo2015). Furthermore, while there is a concern that the process of measuring distortion might accentuate it, there is considerable evidence for the presence of spontaneous distortion emerging in choice tasks involving no process-tracing measures (e.g., Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Meloy and Russo2006; Miller et al., Reference Miller, DeKay, Stone and Sorenson2013) or even no decision (e.g., Glöckner et al., Reference Glöckner, Betsch and Schindler2010; Simon et al., Reference Simon, Pham, Le and Holyoak2001). Although we fully expected to observe non-negligible distortion develop spontaneously in the present research, our objective was not to precisely quantify the magnitude of distortion. Rather, our focus was on tracing how distortion developed over the course of a decision and its resultant effect on confidence levels.

1.3. Confidence and information distortion

The relationship between confidence and distortion is understood to be bidirectional (Glöckner et al., Reference Glöckner, Betsch and Schindler2010; Holyoak and Simon, Reference Holyoak and Simon1999; Simon et al., Reference Simon, Pham, Le and Holyoak2001, Reference Simon, Krawczyk and Holyoak2004). That is, as is almost uniformly reported in studies, confidence in the current leader biases the evaluation of new information, such that the stronger the preference or the higher the confidence at any point, the more likely it is that subsequent information will be judged as supportive of that leader (e.g., Chaxel et al., Reference Chaxel, Russo and Kerimi2013; DeKay et al., Reference DeKay, Patiño-Echeverri and Fischbeck2009, Reference DeKay, Stone and Miller2011; Polman and Russo, Reference Polman and Russo2012). In turn, that greater (although potentially unjustified) support can engender more confidence in the leader. Over the course of the decision, the cycle can be repeated, essentially bootstrapping higher levels of confidence (DeKay et al., Reference DeKay, Patiño-Echeverri and Fischbeck2009).

The action of distortion-driven confidence has yet to receive the same degree of attention as the other part of the cycle, confidence-driven distortion. Prominent exceptions include DeKay et al. (Reference DeKay, Patiño-Echeverri and Fischbeck2009) and (Reference DeKay, Stone and Miller2011), who reported a positive relationship between the evaluation of information and attendant certainty or preference on a unit-by-unit basis during a sequential decision. That is, throughout a decision, the greater the distortion of any unit of information toward a leader, the greater the confidence or preference in the current leader at that stage of the decision. Over the course of the entire decision such preference or confidence increments can accrue, leading to elevated final confidence. Related work reported distortion as mediating such a shift in preference from the beginning to the end of a decision (DeKay et al., Reference DeKay, Stone and Miller2011, Reference DeKay, Stone and Sorenson2012; see also, Charman et al., Reference Charman, Kavetski and Mueller2017). Thus, the greater the observed degree of support for a course of action judged to be present at any stage of a decision, the greater the observed level of confidence in that action, with those effects flowing through to confidence in the final decision.

Expanding on this work, Boyle et al. (Reference Boyle, Russo and Kim2025) traced the process of confidence building as a function of distortion over the course of an entire decision. In that study, entrepreneurs were tasked with deciding whether to recommend the launch of a hypothetical new business venture. As part of the decision, several units of relevant, yet overall neutral, information were evaluated sequentially. Each unit was followed by a measure of perceived informational diagnosticity (i.e., did the information support launching the venture?) and of current confidence (that the final decision would be to launch). Those two measures tracked distortion levels and decision confidence throughout the entire decision. Consistent with past research, evaluation of a new unit of information was found to be dependent on how confident entrepreneurs were that the current leader would be their final choice. The process tracing measures also revealed that increases in confidence (either toward launching the venture or not launching the venture) were driven by the distortion of information which had been designed to be equally supportive of each alternative course of action. Thus, during the decision, the greater the degree of distortion of information to favor a course of action, the greater the tendency to be more confident in the superiority of that course of action. Notably high levels of distortion were observed in the entrepreneurs – and not unexpectedly, high levels of confidence.

The key question of whether the relationship between distortion and confidence extends to a different class of decisions with a different group of decision makers was explored in the present work. The primary objective was to confirm the relationship between distortion and confidence. A secondary goal was to explore whether two candidate predictors of distortion-driven confidence might emerge, specifically, a need for cognition (Cacioppo et al., Reference Cacioppo, Petty and Feng Kao1984) and a tolerance for ambiguity (Budner, Reference Budner1962).

1.4. Other predictors of information distortion

The ability to identify in advance individuals who might be more susceptible to the bias of distortion-driven confidence would be a positive step toward mitigating it. Published distortion research identifying individual difference measures that predict distortion or attendant confidence (e.g., Russo et al., Reference Russo, Meloy and Medvec1998, Reference Russo, Meloy and Wilks2000) is scant. In one study, a hypothetical consumer choice task, decision makers primed with a prevention focus distorted information more than those primed with a promotion focus (Doh et al., Reference Doh, Rim, Kim and Lee2025). Confidence was not reported, so any relationship between distortion and confidence under the study conditions remains uncertain. Having to justify one’s final decision has also been found to result in a decrease in distortion, but only if it was unusually high to begin with (Russo et al., Reference Russo, Meloy and Wilks2000).Footnote 1

Amelioration tactics such as admonishments to work harder have not been found to reduce distortion (nor has actually working harder, as measured by time on task). Furthermore, subjective measures of awareness of engaging in distortion have not correlated with objective measures of distortion (e.g., DeKay et al., Reference DeKay, Stone and Miller2011; Russo et al., Reference Russo, Meloy and Medvec1998, Reference Russo, Meloy and Wilks2000; Russo and Yong, Reference Russo and Yong2011). Other candidate predictors, such as performance on a cognitive reflection task (Frederick, Reference Frederick2005), preference for consistency (Cialdini et al., Reference Cialdini, Trost and Newsom1995), personal need for structure or a personal fear of invalidity (as reported by Nurek et al., Reference Nurek, Kostopoulou and Hagmayer2014), have also failed to correlate with distortion. Indeed, besides confidence (e.g., Chaxel, Reference Chaxel2016) and a desire for consistency (Russo et al., Reference Russo, Carlson, Meloy and Yong2008), very few individual predictors seem to be associated with distortion, although surprisingly, a positive mood leads to more of it (Meloy, Reference Meloy2000; Russo et al., Reference Russo, Meloy and Wilks2000).

Research into individual differences in predicting confidence or overconfidence has yielded mixed findings, depending on, for example, the nature of the decision task, the measures used to identify overconfidence, and the type of overconfidence being measured (e.g., Binnendyk and Pennycook, Reference Binnendyk and Pennycook2024; Li et al., Reference Li, Hale and Moore2025; Logg et al., Reference Logg, Haran and Moore2018; Schaefer et al., Reference Schaefer, Williams, Goodie and Campbell2004). Li et al. (Reference Li, Hale and Moore2025) concluded that ‘overestimation and overplacement do not seem to consistently correlate with trait measures’ but overprecision ‘correlates with itself across domains and time’ (p. 27). Lawson et al. (Reference Lawson, Larrick and Soll2025) also concluded that overconfidence correlates over time for individuals, but noted stable individual differences (e.g., dominance, narcissism) predictive of overconfidence. Li et al. treated overconfidence as a bias in itself and measured it using a subjective probability distribution. In the present work, we tested the association of our candidate trait predictors (described in detail in Section 3.2) with the outcome of an objective change in confidence driven by distortion.

2. Participants

Two samples of students from MBA programs in U.S. universities completed the decision task. The size of the first sample was 89. Three declined to indicate their gender; of the remaining 86, 30 identified as female. Reported age, indicated by categories, ranged from 20 to 59 (modal response 30–39, n = 45). The size of the second sample was 53, with 26 identifying as female. Age was reported in years (median = 24). Prior full-time experience was reported by 70 percent (median = 5.0 years). Because the decision task and the measures (except as noted below) were identical for the two samples, the data were combined for the purpose of analysis, for a total of 142 respondents. (Analyses conducted on the samples separately yielded results consistent with those from the combined analyses.)

3. Method

3.1. Task and procedure

We created a challenging business decision task requiring decision makers to balance competing preferences for two options. The task involved a decision regarding the launching of an advertising campaign that had the potential to increase a firm’s market share but which might mislead some consumers. It required decision makers to consider information that objectively supported both options, launching or not launching the campaign. However, the decision, which had an ethical dimension, had no objectively right answer. Thus, our focus was on the decision process, not the final choice.

The information on which the decision was based consisted of an introductory scenario followed by four additional units of information (‘attributes’) presented one at a time. The introductory scenario included the following information:

Assume that you are the senior executive responsible for marketing and advertising at a large consumer products company… . Currently, you face an important decision. You must decide whether to launch an advertising campaign that claims your established oat bran cereal, Classic Baker’s Oat Bran Cereal, reduces cholesterol, which is an important health benefit… . The question is whether the proposed ad is the best one to launch. One of the concerns you have is whether the claim in the proposed ad is actually true. That is, you are uncertain if the information you have really shows that your oat bran cereal does in fact lower cholesterol… .

Each attribute was presented as a paragraph, written to be approximately neutral overall by providing a balance of confirming and disconfirming evidence of the desirability of each of the two options (the complete introductory scenario and four attributes are set forth in the Appendix). In other words, each attribute on average should have had about the same degree of support for either launching or not launching the campaign. This neutrality allowed information distortion, if it occurred, to be more apparent (Russo et al., Reference Russo, Meloy and Medvec1998).

To achieve the balance, each attribute was pretested, rewritten, and pretested again as needed. In contrast to the actual study, no decision was required in the pretests. To prevent the spontaneous development of a preference toward one option influencing the next attribute evaluated, we tested each attribute on different groups of individuals (Russo et al., Reference Russo, Meloy and Medvec1998), including MBA students not involved in the study. Following Polman and Russo (Reference Polman and Russo2012), we judged an attribute to qualify as neutral if its mean evaluation on a scale from 1 (‘strongly supports not launching’) to 9 (‘strongly supports launching’) did not differ by more than 1 in absolute value from the midpoint of 5 (‘favors neither launching nor not launching’).

To refine the balance of information presented in each attribute, a number of iterations were required, with more than 500 respondents involved in the evaluation of the attributes over a series of rounds of pretesting. Each respondent evaluated a single attribute. Some of the attributes required more iterations to achieve neutrality than others (i.e., within ±1 scale rating of the scale mid-point). The goal was that attributes would be judged on average close to neutral by individuals having no prior preference for either outcome. Large samples (up to 60+) were employed at later stages to ensure that our goal was achieved for each of the four attributes. Although the introductory scenario was designed to present information supporting each of the options, it was not included in the calibration process undertaken for the attributes.

3.2 Instrument and measures

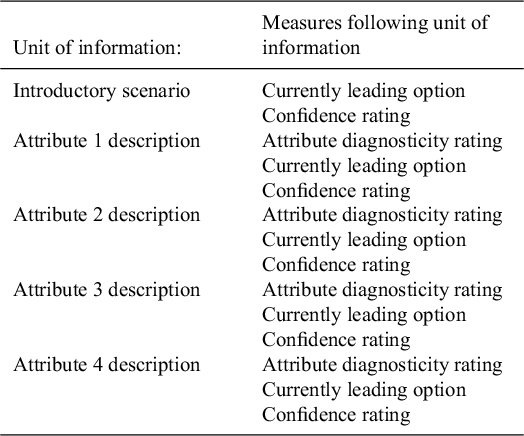

Process measures. Following Boyle et al. (Reference Boyle, Russo and Kim2025), participants were introduced to the decision task with a pageFootnote 2 presenting the introductory scenario. The four attributes presented sequentially came next, each on a separate page. Three process-tracing measures followed each unit of information.Footnote 3 The first was an evaluation of the attribute conveyed by the statement, Given just the information on this page, consider the extent to which you agree with the following statement: This information favors launching the proposed advertising campaign. Responses were captured on a 9-point scale anchored by 1 (‘strongly disagree’) and 9 (‘strongly agree’). This measure identified perceived diagnosticity of the attribute, and served to identify information distortion. Second, participants were asked, Based on all the information you have seen so far, which of the two options [do not launch/launch] seems the better one at this point? The response identified the current leading alternative (the leader). Finally, the participants provided a measure of confidence, Based on all the information you have seen, and knowing that more information may be coming, how certain are you that you will launch the campaign? Responses were recorded on an 11-point scale ranging from 0% to 100% (‘Absolutely certain I will not launch the campaign’/’Absolutely certain I will launch the campaign’), with a midpoint of 50% (‘I could go either way’), in increments of 10. The first and third measures (attribute evaluation and confidence, respectively) were the same as those used in Boyle et al. The second measure, designating the current leader, has been employed in previous stepwise-evolution-of-preferences studies of distortion (e.g., Boyle et al., Reference Boyle, Hanlon and Russo2012; Chaxel et al., Reference Chaxel, Russo and Wiggins2016; DeKay et al., Reference DeKay, Stone and Sorenson2012; Meloy and Russo, Reference Meloy and Russo2004; Polman and Russo, Reference Polman and Russo2012). Table 1 presents a summary of the sequential presentation order of the units of information (and subsequent measures) on which participants based their decision.

Table 1 Order of presentation of units of information and measures following each unit

Final decision measures. Following the four attributes, participants were asked to make a final decision to either launch or not launch the ad campaign. They then indicated their final confidence (How certain are you that you have made the right decision?) on a scale of 50–100 (‘Very uncertain/complete toss-up’/‘Very certain/no doubt in my mind’), in units of 5. Demographic information was gathered after the final decision.

Awareness measure. The procedure and materials were identical for both samples, except that for the second sample three additional measures were presented following the decision task and before collecting demographic data. The first was a measure to determine if decision makers might be aware of any personal decision bias. To that end, the following reflective measure was incorporated: While you were examining the information about the Oat Bran case, do you think you were you able to evaluate the information without being biased toward either launching or not launching the advertisement? Responses were captured on a 7-point scale anchored by 1 (‘not at all biased’) and 7 (‘highly biased’). Given the reported null associations of self-awareness of distortion and actual levels of distortion, we expected no awareness of distortion-driven confidence in our participants.

Trait measures. Next, participants in the second sample encountered two psychometric measures, Need for Cognition (Cacioppo et al., Reference Cacioppo, Petty and Feng Kao1984) and Tolerance for Ambiguity (Budner, Reference Budner1962), hereafter, NFC and TA, respectively. Our goal was to determine if either of those scores might be correlated with any increase in confidence during a decision. For example, a NFC might lead to more careful and systematic processing of information, which should inhibit distortion and thus distortion-driven overconfidence. On the other hand, more effort might lead to even greater levels of distortion as decision makers strived for decision coherence, which in turn could yield greater confidence. A TA might lead to lower levels of distortion if a goal of consistency was less activated, and thus to smaller changes in confidence. Given the exploratory nature of the present study, we adopt an empirical frame and forgo formal predictions.

4. Analyses and results

4.1 Divergence of ratings and confidence

Our core claim is that information distortion is a driver of confidence in a sequential choice task. As information is judged to be more supportive of a leader, confidence in that leader increases. We reveal this by tracking the ratings and certainty levels of each decision maker as they advanced through the decision. Recall that higher values on the 1–9 rating scale indicated greater distortion toward launching the campaign, and lower values indicated greater distortion toward not launching the campaign. On the 0–100 certainty scale, higher values indicated greater confidence of launching the campaign, and lower values indicated greater confidence of not launching the campaign. Increasingly extreme responses on either scale reflected greater divergence between the two options as more information was received. To reveal divergence in evaluations, we computed the individual slopes of attribute ratings over the course of the decision. To reveal diverging confidence to launch or not to launch the campaign, we computed individual slopes of certainty ratings throughout the decision. Any divergence on a scale from a similar starting point, across the repeated responses on that scale, was indicated by a correlation between the slope of the responses and their mean.

Confidence slope. To show the trend in confidence that occurred for each individual over the course of the entire decision, we adopt the general approach of Boyle et al. (Reference Boyle, Russo and Kim2025). A slope of the change in confidence was computed for each decision maker (n = 142). The slopes, which were based on the five separate reports of confidence that followed the fiveFootnote 4 units of information, was computed using a linear contrast score: certSlope = (–2 x initial confidence) + (–1 x confidence at attribute 1) + (0 x confidence at attribute 2) + (1 x confidence at attribute 3) + (2 x confidence at attribute 4). The individual slopes revealed the trend (if any) in each decision maker’s confidence during the decision. Positive slopes indicated that the confidence decision makers would choose to launch the campaign increased over the course of the decision. Conversely, negative slopes indicated that their confidence they would choose to launch the campaign decreased over the course of the decision – equivalent to their having an increased confidence in not launching the campaign. Greater values in either direction denoted more pronounced changes in confidence. Computed certSlope values ranged from –130 to 300, with mean = 28.4; Figure 1 presents the distribution of individual certSlope values.

Figure 1 Correlations of measures of distortion (meanRate = average attribute rating; 1 = does not favor launching campaign, 9 = favors launching campaign) and confidence (meanCert = average confidence rating; 0 = certain not to launch, 100 = certain to launch); attSlope and certSlope (which depict, respectively, individual changes in ratings and confidence during the decision; positive if toward launch, negative if toward not launch).

Attribute rating slope. We adopted a parallel approach to create a slope measure of change in ratings over time.Footnote 5 The slope of the change in ratings was based on the four separate ratings that followed the four attributes. For each individual a rating trend was computed using a linear contrast score: attSlope = (–3 x rating at attribute 1) + (–1 x rating at attribute 2) + (1 x rating at attribute 3) + (3 x rating at attribute 4). Positive slopes indicated that the degree of distortion toward launching the campaign increased over the course of the decision, and negative slopes indicated that the degree of distortion toward not launching the campaign increased over the course of the decision. Greater values in either direction denoted more pronounced support for a leader. Computed attSlope values ranged from –20 to 24, with mean = 1.91; Figure 1 presents the distribution of individual attSlope values.

4.2 Relationship between information distortion and confidence

If distorted evaluation of the presented information was a driver of inflated confidence, then the correlation between the slope of attribute ratings (attSlope) and slope of confidence (certSlope) should be positive. Figure 1 provides a summary of the results of a test of the relationship between the two slopes, along with several related tests (all tests are one-sided unless otherwise noted). The key finding is the significant positive correlation between attSlope and certSlope of r = .279 (all values rounded to two digits in Figure 1; p = .0004), which reveals that as participants’ attribute ratings diverged in support of one of the options, their confidence toward that option also increased. Not surprisingly, the correlation (r = .711, p = .0000) was high between individual mean confidence (meanCert = 43.9) and individual mean rating (meanRate = 4.94). As expected, meanRate correlated highly with certSlope (r = .449, p = .0000), an indication that decision makers who engaged in greater distortion tended to have the greatest changes in associated confidence. Reflecting the other side of the confidence-distortion-confidence cycle, meanCert also predicted attSlope, but less strongly (r = .133, p = .0573).

Thus, the higher the mean of the attribute ratings (i.e., the more attributes were judged as supporting launching the campaign), the greater the increase in confidence (a positive slope) toward launching the campaign; and the lower the mean of the attribute ratings (i.e., the more attributes were judged as supporting not launching the campaign), the greater the increase in confidence (a negative slope) toward not launching the campaign. In other words, as decision makers viewed additional units of information, confidence about their current leader being their final decision increased as a function of distortion of that information. More extreme ratings indicated greater distortion, which provided support for increasing confidence in the leader. Consequently, as revealed by the correlation between the slopes of ratings and certainty, the greater the divergence of the ratings toward the respective options, the greater the divergence in levels of confidence.

4.3 Awareness of bias

There was little evidence that individuals were aware of any personal bias, a result consistent with findings reported in past distortion research. Recall that our self-awareness (SA) measure (‘able to evaluate the information without being biased’) ranged from 1 (‘not at all’) to 7 (‘highly’). The mean of 3.0 suggested moderate self-awareness of a possible bias. However, because the range of responses covered the entire scale, a more relevant question was: How did individual responses relate to actual levels of distortion-driven confidence? If those who had greater increases in confidence also judged themselves as more likely to be biased it would support the premise that decision makers can recognize their own biased judgment process. Our confidence-trend measure included positive (increasing confidence in launching the campaign) as well as negative (increasing confidence in not launching the campaign) values. To relate all greater increases in confidence with potentially higher values of SA, the absolute values of slopes were used. Thus, greater slopes always indicated increasing confidence regardless of the leader. Attesting to the opacity of actual bias in the judgments of decision makers, the correlation between SA and absolute confidence trend was r = –.005 (p = .49). The conclusion is that decision makers' own-assessments of bias were unreliable.

4.4 Other predictors of distortion-driven confidence

In evaluating the possible influence of NFC and TA, the absolute slope for confidence was again used. The correlation between NFC and the confidence slope was r = –.020 (p = .44), which revealed no association between higher NFC and larger changes in confidence toward the leading option. The correlation between TA and the confidence slope was r = –.039 (p = .39), which revealed no association between TA and larger changes in confidence toward the leading option. We address some of the implications of these null results in the next section.

5. Discussion

A study of decision makers with business experience engaged in a realistic business decision task confirmed that distortion-driven confidence could develop even when decision makers had no prior preference for one of the outcomes. The results revealed that distortion of information to support the emerging leader drove higher levels of confidence in that leader. The present work extended that of Boyle et al. (Reference Boyle, Russo and Kim2025), which demonstrated that during an entrepreneurial decision confidence increased as a function of information distortion. By employing a different (non-entrepreneurial) decision task, our results confirmed the generality of the phenomenon of distortion-driven confidence, as did the use of a different class of decision makers. The expected relationship between information distortion and confidence was observed in decision makers having significant business experience.Footnote 6

As they confronted new information, decision makers systematically interpreted the information as favoring whichever alternative was currently leading. Over the course of the decision, support for that alternative built, which in turn yielded increased confidence unwarranted by the actual information available. The process went undetected by decision makers, as they were unmindful of any bias they might have had to illegitimately inflate their confidence during their decisions. Nor was their confidence associated with a NFC or TA.

As the latter two analyses were conducted in the spirit of exploration and with a sample size (n = 53) small relative to other studies of individual difference measures, our findings should not be viewed as conclusive (Lawson et al., Reference Lawson, Larrick and Soll2025). Also, in contrast to other research reporting the correlation between subjective and objective measures of distortion, in the present work, we focused on the relationship between a subjective report of engaging in any biased evaluation during the decision and a tendency for confidence to increase throughout the decision. Although our null results echo those of previous studies, future work in this area would no doubt benefit from larger samples.

A further consideration is that although in the present work increases in confidence were shown to correlate with greater levels of distortion throughout the decisions, an influence of attribute presentation order cannot be ruled out. On the one hand, that every decision maker received identical information in the same order can be viewed as a strength of the present work; on the other, it can be considered a limitation. Conceivably, the increases in confidence observed over the course of the decision might be at least partially attributable to the sequence of attributes. Related also to the nature of the attributes is the fact that despite each of the units of information delivering novel, independent information, a consistent thread through them was an ethical dimension, which may have created a ‘head start’ for one of the alternatives. However, in discerning a superior alternative, a preference for an action judged as ‘more’ ethical should not excuse a biased evaluation of information. Future work would benefit from confirming the relationship between distortion and confidence in decisions having a counter-balanced presentation order of unrelated attributes.

The decisions in the present work were realistic, but admittedly, entirely hypothetical. No material consequences followed from an inferior (or superior) decision. This may have unaccountably altered the observed decisions, perhaps leading to less (or possibly more) distortion. One possibility is that when the stakes of a decision are small decision makers simply minimize judgmental effort to achieve an acceptable outcome. Uncertain is whether such an approach would produce more or less distortion. Still, surmising that greater circumspection in a more consequential decision might yield a lesser degree of distortion sidelines the importance of a desire for coherence. In high stakes decisions, greater distortion and related confidence might develop if a consistency goal were more strongly activated. On the other hand, decision makers might strive for impartiality. Even so, a general deficit of bias self-awareness would pose a challenge to limiting distortion, even for highly motivated, conscientious decision makers. These rival frames warrant an empirical resolution.

Finally, whether the resulting high levels of confidence should be labeled as “overconfidence” merits consideration. The present work does not establish a threshold at which confidence should be deemed overconfidence, even though the resulting levels of confidence were high. Nonetheless, it does demonstrate that the high levels of confidence observed are not wholly justified by an objective evaluation of the available information. This was the case regardless of whether decision makers favored launching or not launching. In the present work, decision makers received exactly the same balanced information. Absent unique knowledge, there is no essential difference between unjustified confidence and overconfidence (Parker and Stone, Reference Parker and Stone2014). We acknowledge that the challenge of definitively characterizing the degree of overconfidence arising from distortion may be the task of future research.

Should our findings be of concern to decision makers? One conclusion from DeKay et al. (Reference DeKay, Stone and Sorenson2012) is that in a given choice situation, ‘whether the effects of information distortion are harmful depends in part on the quality of the initially preferred option’ (p. 356). And, as Russo et al. (Reference Russo, Carlson and Meloy2006) noted, if decision makers who bias their attribute evaluations to support the leading option are those who would have selected that option anyway, ‘then all that these decision makers do when they distort information is build their confidence at no cost to the accuracy of their choice’ (p. 899). Yet, the outcome of a biased decision may not be entirely benign, in part because the selected option may not be optimal. Such a shortfall may have two sources.

First of all, if confidence builds sufficiently during a decision then decision makers may decide to terminate search for additional, possibly countervailing, information and settle for a suboptimal leader. Although in the present work the order and amount of information presented were fixed, in actual business decisions managers may dictate the quantity of information evaluated. If confidence builds quickly during a decision, then a course of action may be fixed upon without the benefit of reviewing additional, potentially critical, information. To a lesser extent, managers may also regulate the sequence in which information is reviewed, but not always. Therefore, when decision makers have little or no control over the order in which information arrives, a second concern is that attribute presentation order may alter the leader.

Through the manipulation of the sequence of information in a choice task, the importance of attribute order was demonstrated by Russo et al. (Reference Russo, Carlson and Meloy2006) and DeKay et al. (Reference DeKay, Stone and Sorenson2012). In both of those sequential choice task studies, researchers induced decision makers to prefer inferior options. This was done by selective placement of attributes favoring the inferior option in early serial positions. In DeKay et al., decision makers indicated a preference for gambles that were objectively inferior. In Russo et al., decision makers were induced to select an option they had personally identified earlier as inferior to another option during an initial series of preferential choice tasks. As Russo et al. reported, in a subsequent choice task involving a disguised version of the inferior option and a superior option (also disguised), decision makers were presented at the outset with an attribute that predisposed them to accept the inferior option as a leader. Then, as in DeKay et al., distortion of subsequent attributes maintained that initial leader even though those attributes conveyed information objectively favoring the superior option (see also, Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Meloy and Russo2006). Tellingly, when the choice was the inferior option in Russo et al., confidence was equivalent to when the superior option was identified. In each demonstration, the effect of establishing a suboptimal leader by way of an initial attribute flowed through to the final choice selection. Of course, decision makers (such as investors) might also be steered toward inferior options by actors with intentions less charitable than researchers.

As a practical matter, can distortion-driven confidence be prevented, or at least mitigated? Two pragmatic approaches have been identified to reduce distortion. Boyle et al. (Reference Boyle, Hanlon and Russo2012) forestalled the appearance of an entrenched leader in a group decision by installing conflicting preferences in different group members for the two options being considered. Then, so long as conflict persisted, distortion and confidence remained low. The results demonstrated the value of internal conflict in limiting overconfidence in group decisions because it disrupted the natural function of a consistency goal in creating a fixed leader. Chaxel and Han (Reference Chaxel and Han2018) further demonstrated the value of creating conflict, this time internally in individuals who had been imbued with a counterargument (CA) mindset prior to making a decision. Because a CA mindset can attenuate a desire for consistency, distortion may be reduced directly. Indeed, relative to a control group, individual decision makers in the CA group had substantially lower levels of distortion and attendant distortion-driven confidence. Thus at least two implementable strategies have been identified to limit levels of confidence, although neither completely averted distortion-driven confidence. As Chaxel and Han noted, in both the CA and control groups confidence still increased over the course of the decisions. And in Boyle et al., once a consensus emerged both distortion and confidence mounted rapidly with the arrival of new information.

6. Conclusion

The prevalence of overconfidence in judgments and decision making suggests multiple causes. No matter how it arises, overconfidence can cloud judgment. Although the causes of overconfidence are not always clear, the adverse outcomes of it are well documented. A better understanding of the antecedents of overconfidence may be useful in avoiding some of its detrimental effects. In the present work, we explored one possible source of overconfidence embedded in the decision process itself. During a decision, as a leading course of action emerges, a desire for cognitive consistency promotes an overly favorable interpretation of information in support of that leader. In turn, that unjustified support for the leader bolsters confidence in its superiority. Over the course of a decision the cycle repeats with the arrival of new information, furnishing additional support and confidence. The consequence is distortion-driven overconfidence in the chosen course of action.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jdm.2025.10025.

Acknowledgments

Two anonymous reviewers provided valuable comments and suggestions on an earlier version of this paper.

A. Appendix

A.1. Background [Introductory Scenario]

Assume that you are the senior executive responsible for marketing and advertising at a large consumer products company. You make the final decisions about all advertising campaigns. This is a challenging task – the company spends millions of dollars promoting its products to consumers, and the money must be spent as effectively as possible. As the senior executive responsible for deciding how the advertising budget will be spent, your performance will be judged on how successful your products are relative to your competitors.

Currently, you face an important decision. You must decide whether to launch an advertising campaign that claims your established oat bran cereal, Classic Baker’s Oat Bran Cereal, reduces cholesterol, which is an important health benefit. As you know, advertising plays a large role in the success of products like oat bran cereals that are essentially the same for all brands. Differentiating a brand in the mind of the consumer is an important step toward gaining or maintaining market share.

The question is whether the proposed ad is the best one to launch. One of the concerns you have is whether the claim in the proposed ad is actually true. That is, you are uncertain if the information you have really shows that your oat bran cereal does in fact lower cholesterol. As you know, the FTC monitors advertising, and has been known to fine companies that run advertisements making false claims. Your marketing group could probably come up with a different ad to run, but it is not clear if it would be as effective.

A.2. Additional information [Attribute 1]

The proposed advertising campaign would feature full-page advertisements in leading magazines targeted at adults, particularly older health-conscious adults. The ads have already been created (and tested) at considerable expense. They are ready to be placed in magazines as soon as possible. There is one concern however: You sincerely believe that Classic Baker’s Oat Bran Cereal is healthy, but you have no clinical evidence that it actually reduces cholesterol in adults. In your favor, high fiber cereals (like oat bran) are widely viewed as being healthy, and it is common for companies selling bran cereals to imply that their products promote good health.

A.3. Additional information [Attribute 2]

A critical health claim in the proposed magazine advertisement would be:

Most oat bran cereals have not been through extensive clinical testing. Classic Baker’s Oat Bran has. It was tested by researchers at a major university medical school, where participants added two ounces daily to a fat modified diet. The results? Classic Baker’s Oat Bran helped reduce cholesterol significantly as part of that diet.

This claim may be partly true. A medical school did test the effect of a low-fat diet on cholesterol levels. The diet included a small amount of Classic Baker’s Oat Bran Cereal. However, the results demonstrated that the low-fat diet, not just the oat bran itself, reduced cholesterol. If this is the case, then the study calls into question the claim that is made in your proposed ad.

A.4. Additional information [Attribute 3]

To make the best possible decision about running the proposed ad for your product, Classic Baker’s Oat Bran Cereal, you ask your assistant to collect additional information. She reports these findings:

-

(1) Your primary target market, adults over forty years old, is increasingly health conscious. They care as much about the health impact of cereals as they do about taste. Further, they seek out information about health and nutrition.

-

(2) An article in a leading medical journal reviewed recent research about the impact of oat bran on cholesterol levels. It found no conclusive evidence that consumption of oat bran provides a health benefit in terms of reduced cholesterol.

A.5. Additional information [Attribute 4]

Your market research team has tested the proposed magazine advertisement with consumers. They found that test market consumers paid attention to the ad’s message, and were persuaded. After reading the ad, consumers reported more positive attitudes about Classic Baker’s Oat Bran Cereal and indicated a higher likelihood that they would buy the product. In short, the test of the advertisement was successful. Specifically, 80 percent of consumers who viewed the test ad concluded Classic Baker’s Oat Bran Cereal was ‘healthy’. However, your target consumers also drew conclusions that were not supported by medical research about the value of oat bran cereals in reducing cholesterol. Although the research found no connection between oat bran consumption and cholesterol levels, more than half of the consumers in your test market went away believing that Classic Baker’s Oat Bran Cereal had been proven to reduce cholesterol. Despite the fact that no medical proof of the cholesterol benefits of oat bran exists, you personally believe that Classic Baker’s Oat Bran Cereal is a healthy product.