In the early 1970s, journalists, policymakers, and corporate executives in the United States grew concerned with a growing group of college students, telephone tinkerers, and electronics hobbyists who dubbed themselves “phone phreaks.” The phreaks, whose name reflected a phonetic play on “phone” and “freak,” were “college students high on electronic circuitry, freckle-faced teen-agers,” “pranksters,” and “blind kids,” wrote Los Angeles Times columnist Maureen Orth. They knew telephones “the way Ralph Nader knows General Motors.”Footnote 1

Phreaking, as its practitioners described it, was the practice of manipulating and experimenting with the American telephone system. The icon of American telephony was AT&T, or the “Bell System,” a public monopoly and America’s dominant telephone service provider. To the phreak, Bell was an “electronic playground.”Footnote 2 It was a “huge game and Ma Bell was ‘it,’” as one Bell security agent described the phreaks who bedeviled him.Footnote 3 A phreak’s principal tool was the “Blue Box,” a multifrequency device that allowed its users to call anyone, anywhere, anytime—for free. As Ron Rosenbaum wrote in “Secrets of the Little Blue Box,” an October 1972 Esquire feature, “it gives you the power of a super operator.”Footnote 4 By the mid-1970s, front-page features in the Wall Street Journal suggested that tens of thousands of Americans, from college students to businessmen, celebrities, and white-collar criminals, dabbled in phreaking.Footnote 5 What compelled such a wide berth of Americans to wrangle their way through the Bell System?

As phreaking gained notoriety, observers in the press pointed to parallels between phone phreaking and the broader countercultural movements of the 1960s and 1970s. As one Washington Post columnist noted in 1971, “sophisticated chiselers with pocket-sized electronic ‘blue boxes’” were not so much curious college students or harmless hobbyists as activists and punks inspired by the New Left, especially the provocateur Abbie Hoffman.Footnote 6 In the New York Times, columnist Michael Drosnin concurred by casting phone phreaking as an outgrowth of Hoffman’s “radical ideology” of “theft-without-guilt,” an ideology that understood “America as a society based on the rip-off.”Footnote 7

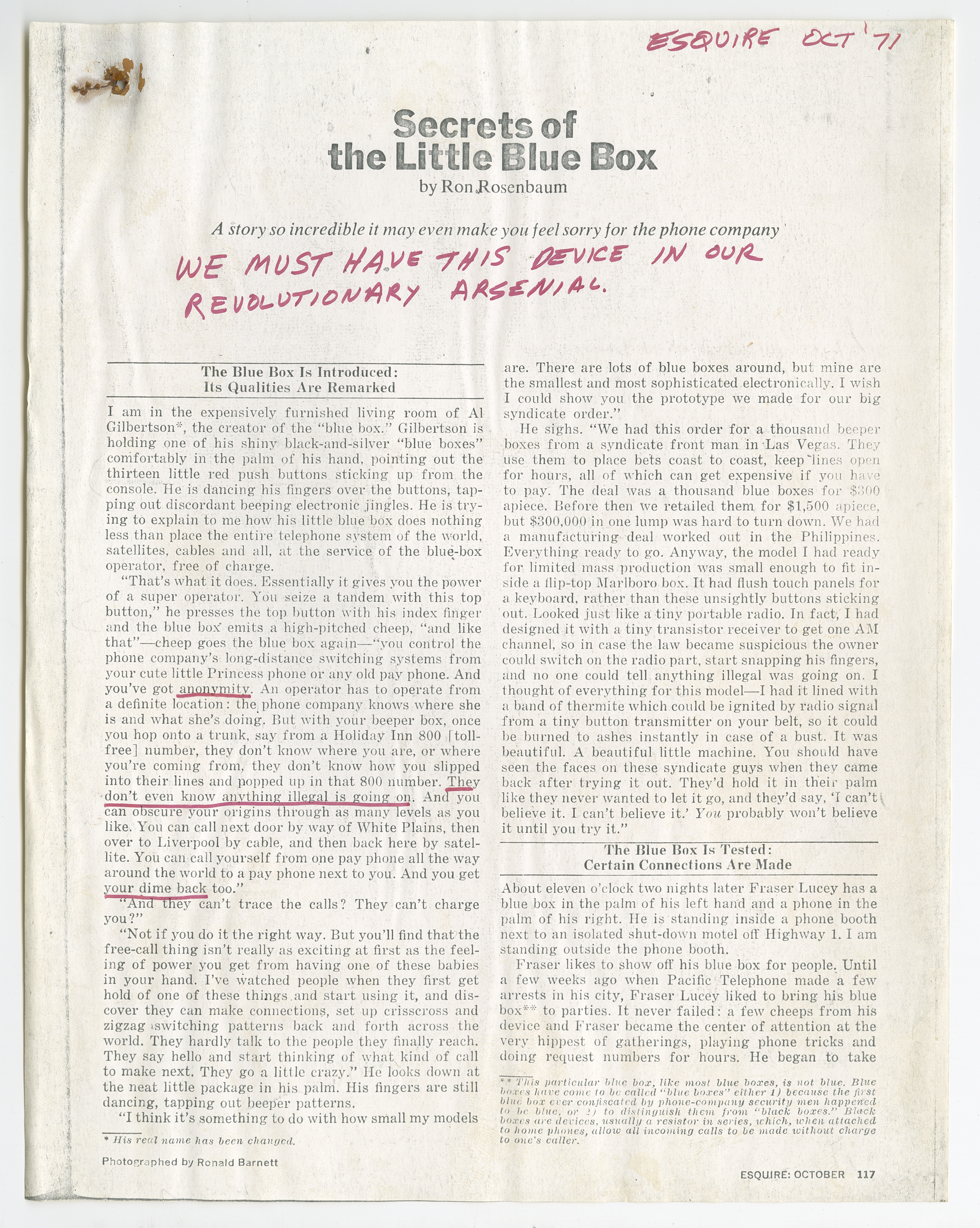

Ripping off the telephone company was a recurring theme in Hoffman’s writing and speaking in the early 1970s. In Steal This Book, Hoffman’s 1971 bestselling outline for waging “Monkey Warfare” against American government and corporations, Hoffman wrote that “as long as there is a phone company, and as long as there are outlaws, nobody need ever pay for a call.”Footnote 8 More importantly, though, Hoffman argued that phreaking was an activist act; with practice, a phreak’s tools could become the implements of dissatisfied Americans seeking political change. Thus, when Hoffman acquired a copy of Rosenbaum’s 1972 essay on the Blue Box, he studiously underlined many sentences and scribbled “Dig it!” at many points in the margins. But no annotation was more telling than his declaration atop the cover page: “WE MUST HAVE THIS DEVICE IN OUR REVOLUTIONARY ARESENAL.”Footnote 9 (Figure 1) Hoffman, in short, saw phreaking as a radically new tool to revolutionize and democratize technology in modern America.

Figure 1. Abbie Hoffman’s copy of Ron Rosenbaum’s “Secrets of the Little Blue Box,” a famous feature article in the October 1971 issue of Esquire.

Source: Ron Rosenbaum, “Secrets of the Little Blue Box,” “Legal Dope,” box 2019-050/14, Abbie Hoffman Papers. Photo: camh-dob-035240_0001, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, Austin, Texas.

Critiques of AT&T resonated across American life in the 1960s and 70s. Indeed, Hoffman was hardly alone: the 1970s saw signs, t-shirts, leaflets, magazines, and buttons emblazoned with the phrase “Ma Bell is a Cheap Mother!” and more to the point, “Fuck the Bell System!”Footnote 10 AT&T’s unsurpassed size and influence as the country’s largest public monopoly, its longstanding ties to military-industrial institutions and law enforcement, its discrimination against women and minorities, and the oppressive conformity within its intellectual and cultural climate—together, these elements made the Bell System a principal part of the American system writ large. Domestic political actors mounted sustained demonstrations against the Vietnam War, staged labor action against race and gender discrimination, and sounded alarms about creeping practices of technological surveillance. AT&T was a plausible adversary for those seeking change in each of these domains—and an easy object for the ire of those who simply sought to rage.Footnote 11 To its critics on the New Left, like Hoffman, AT&T’s telephone lines were reinterpreted as the wires of American empire.Footnote 12 Even in mainstream American society, where AT&T stood as a traditional symbol of the country’s innovation, businessmen and lawmakers increasingly saw AT&T as a paradigmatic monopoly and prime target for antitrust law.Footnote 13

These critiques of the Bell System, and the broader political economic systems it represented, were sketched in the Youth International Party Line (YIPL), a magazine Hoffman co-founded to bridge phone phreaking with New Left political preoccupations and repackage them in the provocative language of the Youth International Party (YIP). In 1967, New Left activists Abbie and Anita Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Nancy Kurshan, and Paul Krassner created YIP as a new, experimental organization for coordinating protests. YIP joined other organizations on the New Left in embracing the promise of “participatory democracy” and creating decentralized and cooperative social, cultural, and economic institutions as foils to those in the mainstream.Footnote 14

This article examines how activists and phone phreaks turned YIPL into an organ for sharing information about the Bell System. Its pages constituted a collective paper workbench advancing the “alternative” technology of phreaking and articulating its uses as a political tool to fight “the system.”Footnote 15 As such, YIPL’s pages offer a glimpse into the processes of “mutual shaping” by which politicians, businessmen, journalists, social movements, and communities of telephone users determined the social significance of the telephone system and debated the politics of emerging technologies in modern America.Footnote 16

Like other watchwords of the era, “system” had many meanings in modern America. Some were inflected by novel advances in science and technology, emerging social movements, and short-run political developments, while others reflected longstanding currents in American political culture or recurring features of the ideological struggles that characterized the Cold War. System could easily become a floating signifier, attaching to any structure or object of opposition: capitalism, American foreign policy, law enforcement, sexual norms. Which is to say, the more people talked about systems, the less they seemed to agree about what “systems” meant.Footnote 17 Despite its diffuse uses, however, Yippies and phreaks offered a unique articulation of “system” amid this period’s profusion of metaphors—among them “the man,” “the machine,” and “Big Brother.” For the phreaks, invoking this metaphor rendered the Bell System into a powerful metonym for the broader American political economic order.Footnote 18

But the community-oriented, anti-war, and countercultural politics of phreaking in the early 1970s morphed into an anarchistic and techno-libertarian politics by the late 1980s. Such a transformation from New Left to libertarian is a familiar story for American historians. As Fred Turner shows, the “New Communalism” created by techno-enthusiast hippies contained the seeds of a market-friendly politics, which ascended as “neoliberalism” as the tenets of a once-radical “counterculture” became the foundation for a libertarian “cyberculture.”Footnote 19 Period portrayals of “the revolution [as] not something to be fought for, but something to be relaxed into, lived and experienced in the moment,” transformed the processes of self-making and remaking into the principal terrain of political activity.Footnote 20 According to Gary Gerstle, challenges to midcentury “political order” from the New Left prized the self as the site of political change, valorized the individual, and, ironically, became a vector for “neoliberal” ideas in the United States and abroad.Footnote 21 The New Left-to-libertarian or neoliberal arc comports with the critical posture of academics and politicos vexed by the New Left, then and now, who waved away the Yippies as nothing more than “cultural leftists” who eschewed politics and, above all, as Hoffman himself opined in 1968, chased “risk, drama, excitement, and bullshit.”Footnote 22

In following phone phreaking’s trajectory from a tool claimed by New Left communities in communitarian, anti-war, and labor struggles of the 1970s, to an increasingly libertarian politics in the 1980s, historians can view the origins of American techno-libertarian politics in a new light.Footnote 23 More than a catalog of one political vision’s decline, or the revelation that one political movement contained the seeds of another, this history points to enduring continuities between the Yippies-turned-phreaks of the 1970s and the hacker cultures of the 1980s and 1990s.Footnote 24

By examining phreaking in the political context of AT&T’s political and infrastructural omnipresence in twentieth-century America, we bridge the interests of historians who map “political orders” and “socio-technical regimes” with the concerns of scholars invested in reassembling the cultures and practices of groups like the phreaks.Footnote 25 Writing on Silicon Valley is exemplary of this synthesis, but readers of recent historiography may well wonder how the tension between politics and technology manifests in the vast geography of modern America, well beyond the Bay Area.Footnote 26 The history of hacking, which academic and popular accounts often study in institutions like Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), share some geographical and conceptual constraints.Footnote 27

Indeed, phreaks and hackers complicate the typical boundaries historians use to categorize states, corporations, science, and technologies, and thereby provide an opportunity to weave methods across these historical subfields.Footnote 28 Phreaks, users on the margins of American telephony, took to writing, protesting, and technological practice to express themselves and seek political change. Seeking to understand the ideas, practices, and relationships between communities of users gets beyond well-told stories about politicians, executives, and engineers, while revealing an unlikely case of innovators, maintainers, disruptors, and everyday people reconfiguring and cocreating the technologies that shape their lives.Footnote 29 The site of that analysis here is the infrastructure of the United States’ telecommunications system, whose crossed wires were the sites for many of the most pressing political conflicts of the twentieth century.Footnote 30

That phone phreaks and hackers do not just merely argue about technology, but “also argue through it,” suggests that technical practice be taken seriously as a political activity.Footnote 31 In forums like YIPL, phreaks and, eventually, hackers created “recursive publics” vitally invested in the material and technical evolution of technology and technological systems; the legal, ethical, and conceptual dimensions of technological development; and the relationships between social and political imaginaries and real possibilities—and, conversely, the structures technology reinforces and the futures it renders impossible.Footnote 32 Phreaking, like practices of hacking, coding, patching, tinkering, and sharing, reconstituted the relationships between Americans and the broader technological systems they lived with and through.Footnote 33 Examining the political justifications for phreaking as vernacular politics uncovers a Yippie-influenced point of origin for “hacker culture,” with all its pranking, dark humor, and ambivalent politics.Footnote 34 But the politics of phreaking were only temporarily settled in the early 1970s. Like the widespread invocation of “the system” itself, phreaking came to represent a variety of political views in modern America.

The Bell System

The Bell System emerged as the backbone of American telecommunications from the social, political, and technological shocks to American life in the late nineteenth century. Founded in 1875, the American Telegraph & Telephone Company (AT&T) entered a phase of aggressive expansion (or, as one historian thematized the company’s history in 1939, “industrial conquest”).Footnote 35 After a series of acquisitions in the 1880s, AT&T came to be. Led by the bullish AT&T president Theodore N. Vail, a master of corporate intrigue and political maneuvering, AT&T secured the status of a public monopoly in U.S. telephone service in 1913, a position it would hold until the early 1980s.Footnote 36

Come the mid-twentieth century, AT&T had become a symbol of the American corporation. By 1960, AT&T was the world’s largest corporation. It employed over 1 million people—a workforce containing 7,452 Smiths, 5,880 Johnsons, 3,934 Williamses, 3,600 Browns, and 3,547 Joneses—and was an employer surpassed only by the federal government. AT&T’s assets totaled over $114 billion, more than General Motors, Ford, General Electric, Chrysler, and IBM combined. It made $16 million a day and $11,000 per minute. The Bell System owned a total of 24,000 buildings, from small brick facades on midwestern Main Streets to a brand-new, 2-million-square-foot headquarters for Southern Bell in Atlanta. It owned a fleet of 177,000 motor vehicles, including jeeps, scooters, and industrial trucks for material transportation. The AT&T long distance division even owned vessels to lay cable deep undersea.Footnote 37

If the cumulative size of its subdivisions testified to AT&T’s unparalleled capacity, the research and development within Bell Laboratories earned the company its reputation as the epicenter of technological innovation in the twentieth century. Therein, scientists, engineers, and technicians developed the transistor and early semiconductors, laying the foundation for modern computing. Amid the Cold War space race, they deployed the first communications satellite, the Telstar 1; and as cellular communications rose to prominence, they created some of the first cell phone networks. For many Americans, Bell Labs was the epitome of innovation. In the words of one journalist, it was the American century’s “idea factory.”Footnote 38 Western Electric, Bell’s manufacturing wing, was viewed in the same vein. To the public, Western Electric’s business was nothing short of “manufacturing the future.”Footnote 39

In the mid-twentieth century, the number of telephones in the United States grew dramatically. For example, in 1855, a decade after AT&T was created, there were 340,000 telephones in use across the United States. By 1965, this number had multiplied by a factor of over 275 to 93,656,000—83% of which were Bell telephone models.Footnote 40 According to a 1969 report by McKinsey, the Bell System telephone network alone contained over a trillion components, ranging from colored phones to cable lines between major metropolitan areas.Footnote 41

For the first half of the twentieth century, the telephone company was represented by the operators: thousands of employees, mostly women, who would answer and connect callers to whomever they were trying to reach. But as Americans spread out in the postwar period—moving for work, for school, or simply to hit the road—the volume of long-distance dialing traffic ballooned.Footnote 42 Executives at AT&T and engineers at Bell Labs realized that it would simply be impossible for a network stitched together with human switches (operators who connected calls manually by switchboard) to meet Americans’ growing demand to talk over the telephone. Automation, they decided, would chart the path to a more robust telephone network. With the introduction of automated switching machines that routed long-distance calls, and new multifrequency tones in telephone equipment, the Bell System’s network became what engineer Phil Lapsley called a “mechanized brain,” and for its time, the “largest machine in the world.”Footnote 43

The innovative automation of Ma Bell’s network was a massive success—so much so that Bell openly advertised the inner workings of its long-distance system. In Popular Mechanics, Bell published an advertisement likening long-distance automatic dialing to “playing a tune for a telephone number” on a “musical keyboard,” with each “key” corresponding to specific digital tones.Footnote 44 Bell released educational materials like the film “Speeding Speech,” which described the technical operations of the system at length, even recording the exact tone sequences for each key.Footnote 45 And its flagship scientific journal, the Bell System Technical Journal, published a nearly step-by-step guide to using the new digital frequencies to start and end long-distance telephone calls.Footnote 46 Ma Bell, a monopoly at the peak of its influence in American life, did not fear that its secrets would fuel competition. But the Bell System’s open distribution of technical information made it into a testing ground and back alley for an odd assortment of college students, tinkerers, bookies, and countercultural radicals: the phone phreaks.

The Origins of Phreaking

Drawing on the information Bell made publicly available, hundreds of hobbyists and tinkerers developed several methods to access the telephone network. As their numbers grew and the practice of information sharing developed regular channels of communication between individuals, a community of phone phreaks was born. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Joe Engressia, a blind student with perfect pitch at the University of South Florida, earned the name “Whistler” after he discovered that he could whistle the exact 2600Hz tone into the telephone to make free calls.Footnote 47 Other phreaks, like Sid Bernay, discovered that a toy whistle in a Cap’n Crunch cereal box emitted the same 2,600Hz tone needed to access the new Bell System long-distance network.Footnote 48 Telephone users could make free calls by recording the “ping” of a pay coin slotted into a pay phone, playing the recording into the receiver, and deceiving operators.Footnote 49

Plastic toys, perfect pitch, and clever tricks could only take phone phreaks so far, however. While the Bell System installed automated long-distance dialing mechanisms in the early 1950s and 1960s, other phone phreaks were at work constructing devices to mimic and exploit the multifrequency tones used in Bell’s new touch-tone system. Of the multifrequency devices phone phreaks created, none was more powerful (or infamous) than the Blue Box. Blue Boxes were thirteen-pushbutton devices that connected their users to the long-distance network by emitting the tones necessary to access it. With the invention and distribution of transistors in the 1950s and 1960s, handheld, battery-powered, and cheap Blue Boxes became feasible and widespread.Footnote 50 Blue Boxes could be constructed with parts purchased at a local hardware store or refashioned from electronic pianos and doorbells. Anyone with a rudimentary understanding of electronics could build one.

Phone phreaking quickly became a technical pastime with social significance. The phone phreaks were one of the many communities of young (mostly white) men who identified as hobbyists and tinkerers after World War II.Footnote 51 As droves of mass-market radios, gadgets, and computers entered the consumer market, local and national groups of students, hobbyists, and enthusiasts of amateur radio, microcomputing, and gaming, for example, made tinkering and improving technology into a shared purpose and proving ground for intellectual and masculine identities.Footnote 52 Historians of such communities demonstrate the paradoxes of their peripheries: they purported to prize technical skill above all else, welcoming “geeks,” “nerds,” and demobilized American G.I.s alike in the process, while often reproducing gendered and racial prejudices that reflexively closed their ranks to many other Americans.Footnote 53

The phreak’s obsession with technical knowledge made demonstrations of skill into socially significant performances among peers. In the late 1960s at MIT and Harvard, for example, students gained access to the Department of Defense’s Automatic Voice Network (AUTOVON) lines and started calling Strategic Air Command bases. “Our interest wasn’t in making free calls but in fooling a system that wasn’t designed to be fooled,” one of the students reported. “It was a challenge,” he continued, one that “revealed some aspects of the system that the company had ignored or poorly designed.”Footnote 54 Phreaking allowed its practitioners to claim social status they otherwise lacked. Steve Wozniak would later describe his time phone phreaking as a period in which he was a technical “leader,” a pioneer “doing something that nobody would really believe was possible.”Footnote 55 While Wozniak was a student at the University of California, Berkeley, he partnered with Steve Jobs to make and sell Blue Boxes to other students in his college dormitory. With each box, the duo included a paper slip that read “you have the world in your hands.”Footnote 56 All phreaks seemed to share this feeling when they plied the telephone system—Blue Box in hand.

Though communities of phreaks remained mostly white and male, their collaborative and competitive pursuits did not exclude others as a rule. Susy “Thunder” Headley, one of the few women involved, recalled that “Everybody was trying to outdo everybody else to see who was greater, who was better, who had better access, who could get into the tightest or best systems.”Footnote 57 Technical prowess could mean acceptance in a community of phreaks. Phone phreaking introduced blind users to a community that welcomed their acute sense of hearing and unique interests in the Bell System. Engressia, for example, described his entry into the phreak scene as “opening up a new world.” Learning with and about “the phone,” he continued, became a “shaping force on my whole life.” With friends like phreaks, Engressia garnered a respect that U.S. society otherwise withheld.Footnote 58

Descriptions of phone phreaks as teenage pranksters and obsessive technicians dominated writing about the phenomenon early on. In 1968, media accounts stressed a tension between the passive love of a hobby and an active embrace of that hobby’s political significance, between views of the Bell System as a virtual playpen for testing a phreak’s telephonic prowess and as a proving ground for political action. In the late 1960s, Wall Street Journal columnist Ronald Kessler described phreaks as young men and “engineer types” who wanted to prove that “‘the system’ can be beaten.” Free calls were simply a “fringe benefit.” Crucially, the columnist contrasted this movement of “free phoners” and their relentless pursuit to “outfox” the telephone company with the visible sit-ins, be-ins, and love-ins of the 1960s youth movements.Footnote 59 Technical challenges and pursuits, he concluded, stood beyond politics. Within the next several years, however, the Yippies appropriated phreaking as a tool of political protest.

Phreaky Politics

In 1971, Abbie Hoffman and a Cornell University engineering major, Alan Fierstein, writing under the pseudonym Al Bell, co-founded the Youth International Party Line (YIPL). YIPL sought to make phone phreaking into a new tool on the New Left. The Bell System was not viewed favorably among the phone phreaks publishing YIPL. In its first issue, the editors described their purpose as educating the American public about the “phone company’s part in the war against the poor, the non-white, the non-conformist.” The Bell System was against “the people,” and YIPL’s editors encouraged readers to share the magazine with friends, colleagues, and local libraries.Footnote 60 By invoking the “party line,” a practice of sharing telephone service between households in rural America, the editors evoked ideas of community-led technology.Footnote 61

“YIPL is a Public Service,” stated an August 1971 statement of purpose. Its function was to “bridge the communications gap” between Americans by “spread[ing] any information” that was blocked by “monopolies like THE BELL SYSTEM.” “For those of you who don’t understand exactly who the hell we are, let me make one thing perfectly clear,” YIPL’s editors wrote: “We are not them.” Readers were encouraged to reproduce useful pieces from the magazine and distribute copies at “strategic locations,” to tell their friends, to write articles for YIPL, and to share articles with any “half-decent paper” in the reader’s town.Footnote 62 Later issues “authorized” every reader to represent YIPL and encouraged them to prepare radio programs on “phone politics and technology” for local stations.Footnote 63

Alongside organizations and publications on the New Left, YIPL mobilized ideas widespread in postwar counterculture about the individual as the primary unit of political activity, a person whose malleable identity could be remade in the image of tomorrow’s politics. When Hoffman wrote that phreaks were “America’s last great inventors,” he meant this technologically—and politically.Footnote 64 In YIPL’s pages, as in pop art and glossy magazines, politics appeared in compelling sets of beliefs ready for modification. As an early editorial in the journal instructed in a bulleted list:

-

YIPL is anti-corporate technology

-

YIPL is how to do it

-

YIPL is for you

-

YIPL is you

-

YIPL is you sending in articles

-

YIPL is you teaching others

-

YIPL is you yelling at us when we say dumb things

-

YIPL is yelling at you when you don’t say things

-

YIPL is in need of your support, and your friends

-

AT&T and ITT want to catch YIPL but they know that YIPL is growing into the whole lot of together people that YIPL is.Footnote 65

As the magazine evolved, YIPL’s editors emphasized that their magazine should be a channel for a community to share information: its contents would be entirely “reader-supplied.” The goal was to make the magazine into a “centralized information pool … well-stocked with useful hints” about the telephone system, food system, media, and transformation networks.Footnote 66 It was also to include tips on the latest “corporation ripoffs, establishment fucks, healthful hints,” and contacts of potential readers.Footnote 67 “All useful ideas will be published,” the editors promised.Footnote 68 “You are the source of information,” instructed a later issue, forming a “radical yellow pages.”Footnote 69 Phreaking itself was styled as a universal tool. “Anyone can be a phone phreak, regardless of technical knowledge,” Hoffman wrote. “You need not be a certain age, sex, or anything,” and—better still—Hoffman wrote that “every phone phreak gets away with it.”Footnote 70 Readers were encouraged to support YIPL by “reprinting” and distributing it to friends, while always keeping a “stock of Xeroxed copies” ready-to-hand for would-be Yippies. Put differently, “When you get the shit, be sure to duplicate it immediately.”Footnote 71

Beyond reproducing articles, readers were encouraged to plug YIPL into the decentralized network of activist and countercultural instructions flowering on the New Left. A May 1972 missive admonished readers to “START YOUR OWN LOCAL CHAPTER OF YIP!” Holding workshops, “information drives,” educational meetings, or other convenings with health clinics, food coops, libraries, headshops, day care facilities, radio stations, newspapers, bookstores, and local television and radio stations or “any communications medium that reaches many people” was encouraged.Footnote 72

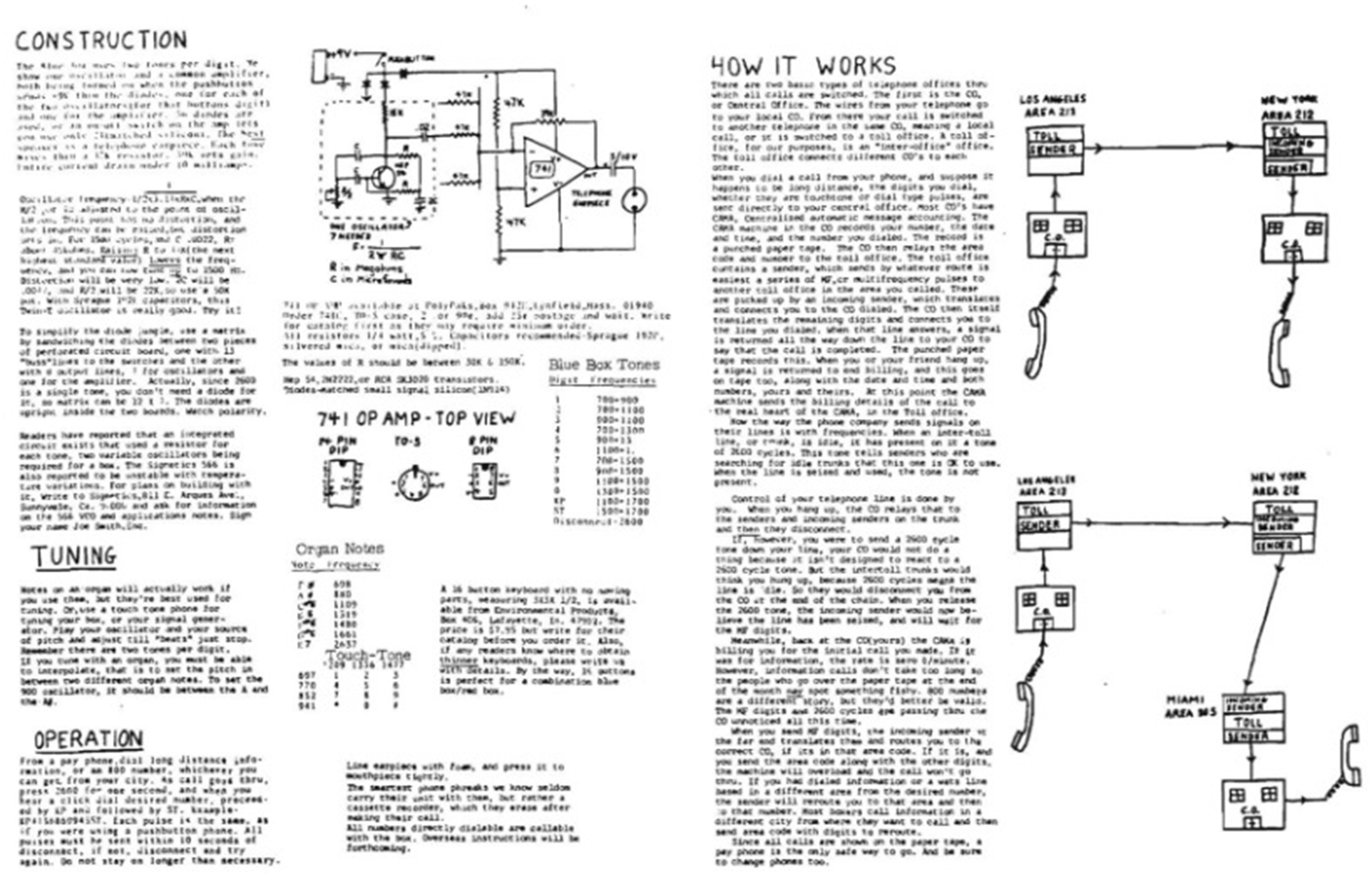

The magazine featured hundreds of diagrams, guides, and parts lists for the building of multifrequency devices phone phreaks used. (Figure 2) Beyond construction manuals, it published guides to manipulating telephone operators, using stolen credit card codes, and cheating utilities and the Postal Service on bills. Other articles instructed readers in a range of low-tech hacks to circumvent paying at pay phones, parking meters, and vending machines—using everything from #14 washers, ice, and bottle caps to fool meters and Ma Bell—and to lower utility meter bills, make fake IDs, and pick locks. In the early 1970s, one YIPL contributor named Jack Flash described the phreak philosophy, in part, as prolonged “underground warfare against mindless mechanical bandits.”Footnote 73 The Bell System personified monopolistic corporations and government power alike. Thus, as Hoffman explained in an early issue, these were not mere schemes for free stuff; they were practices for actualizing “pay phone justice,” strategies for accessing public services.Footnote 74

Figure 2. A diagram for constructing a blue box from the August 1972 (no. 12) issue of Youth International Party Line, the foremost publication on phone phreaking in the 1970s.

Source: Youth International Party Line, August 1972 (no. 12), 2.

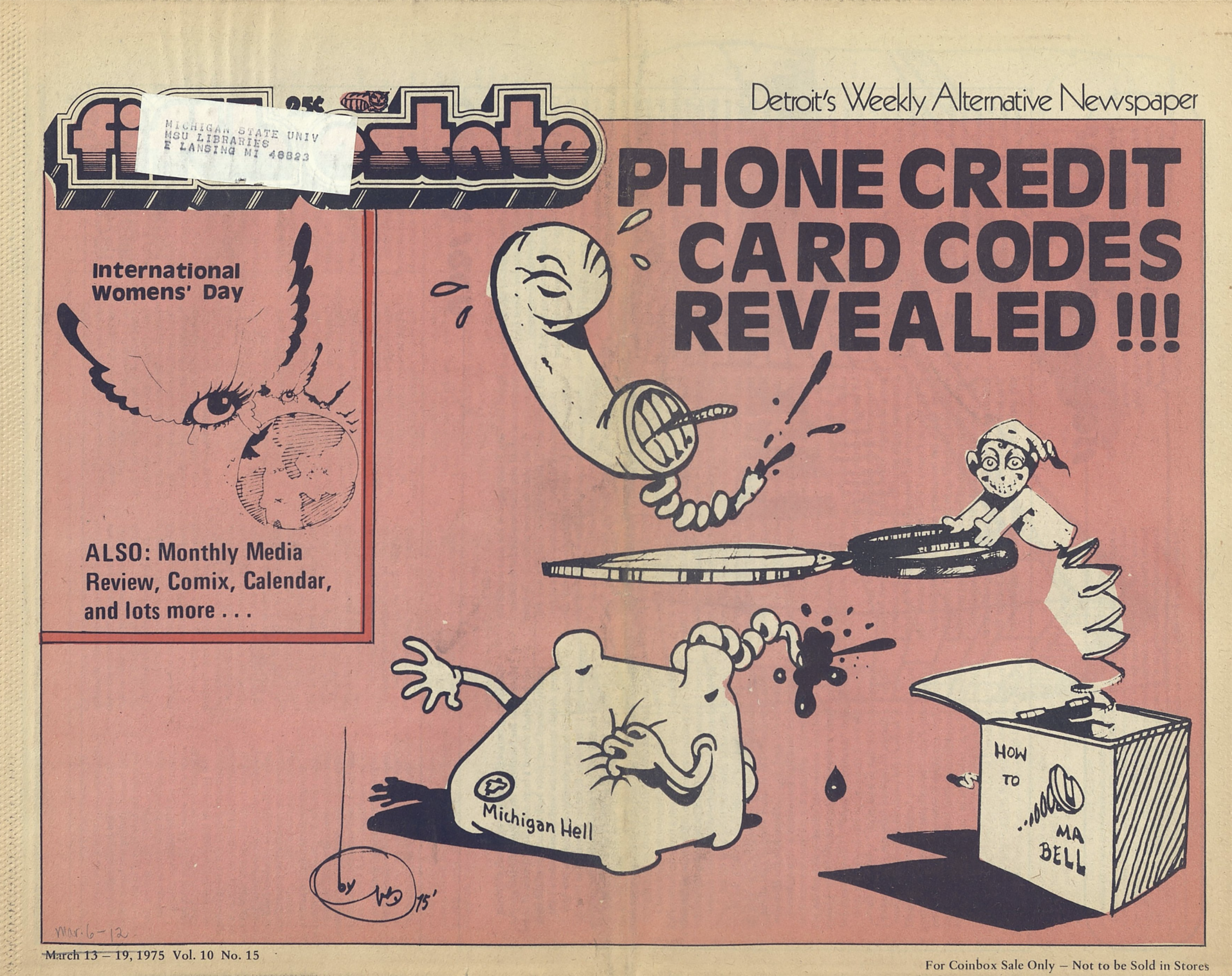

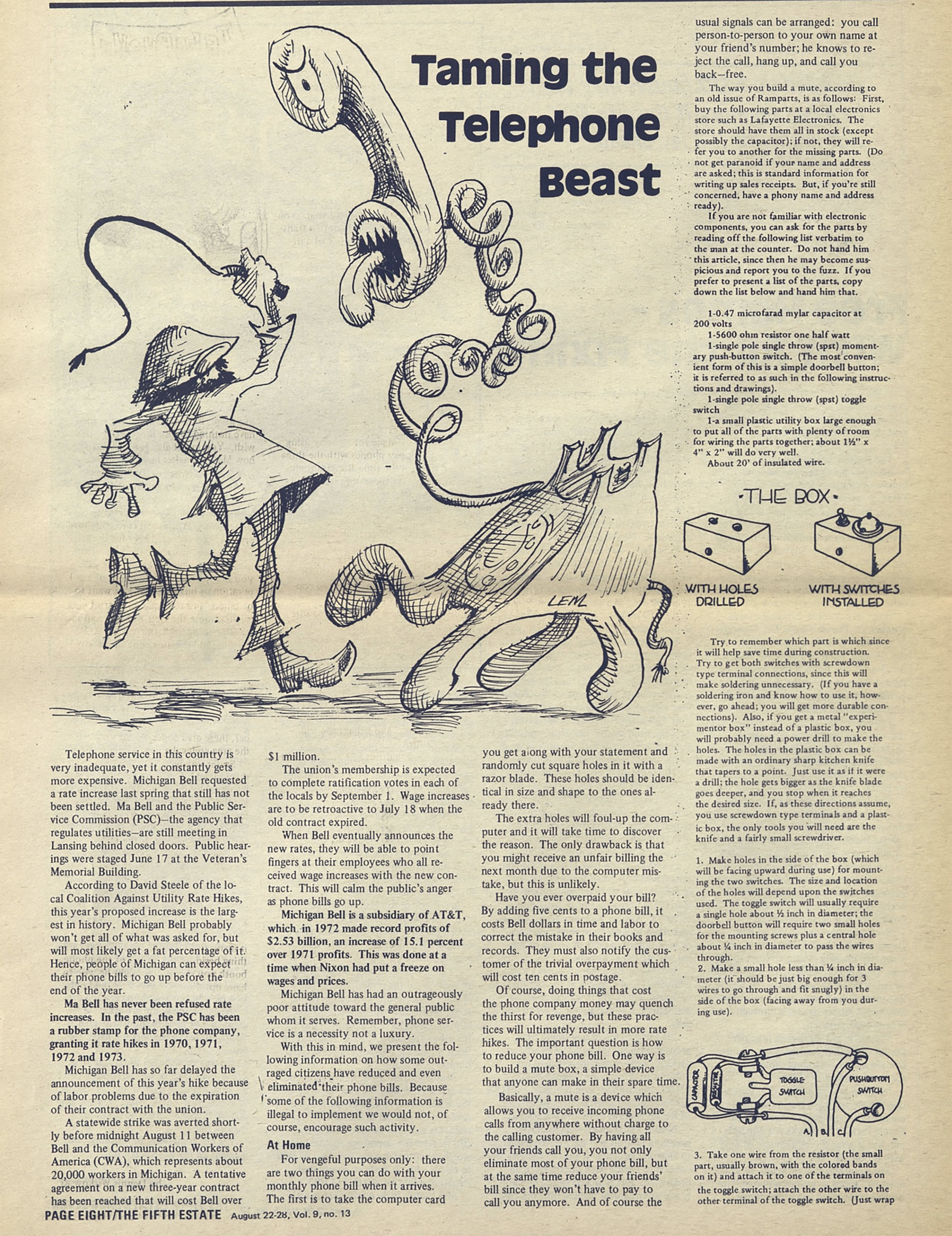

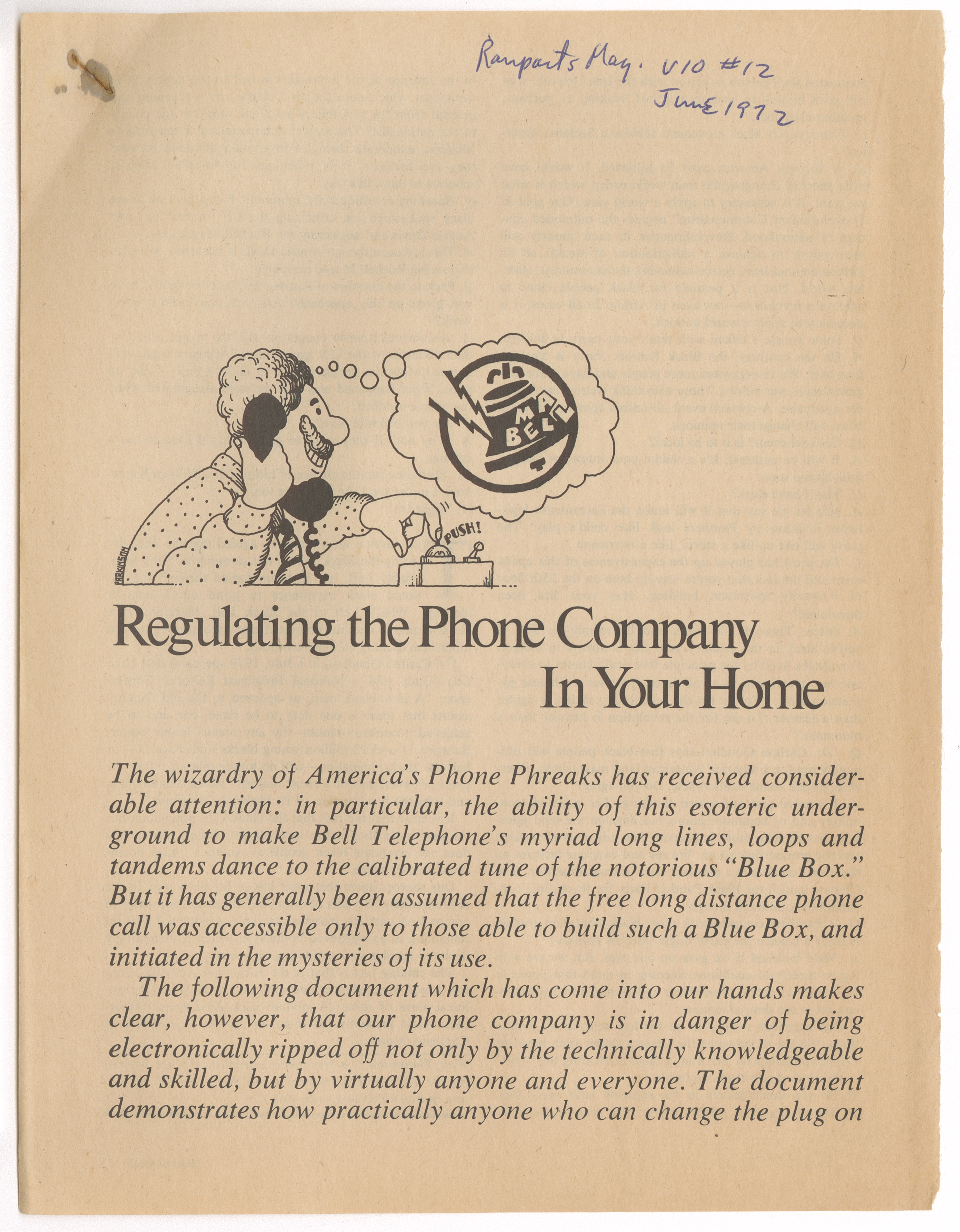

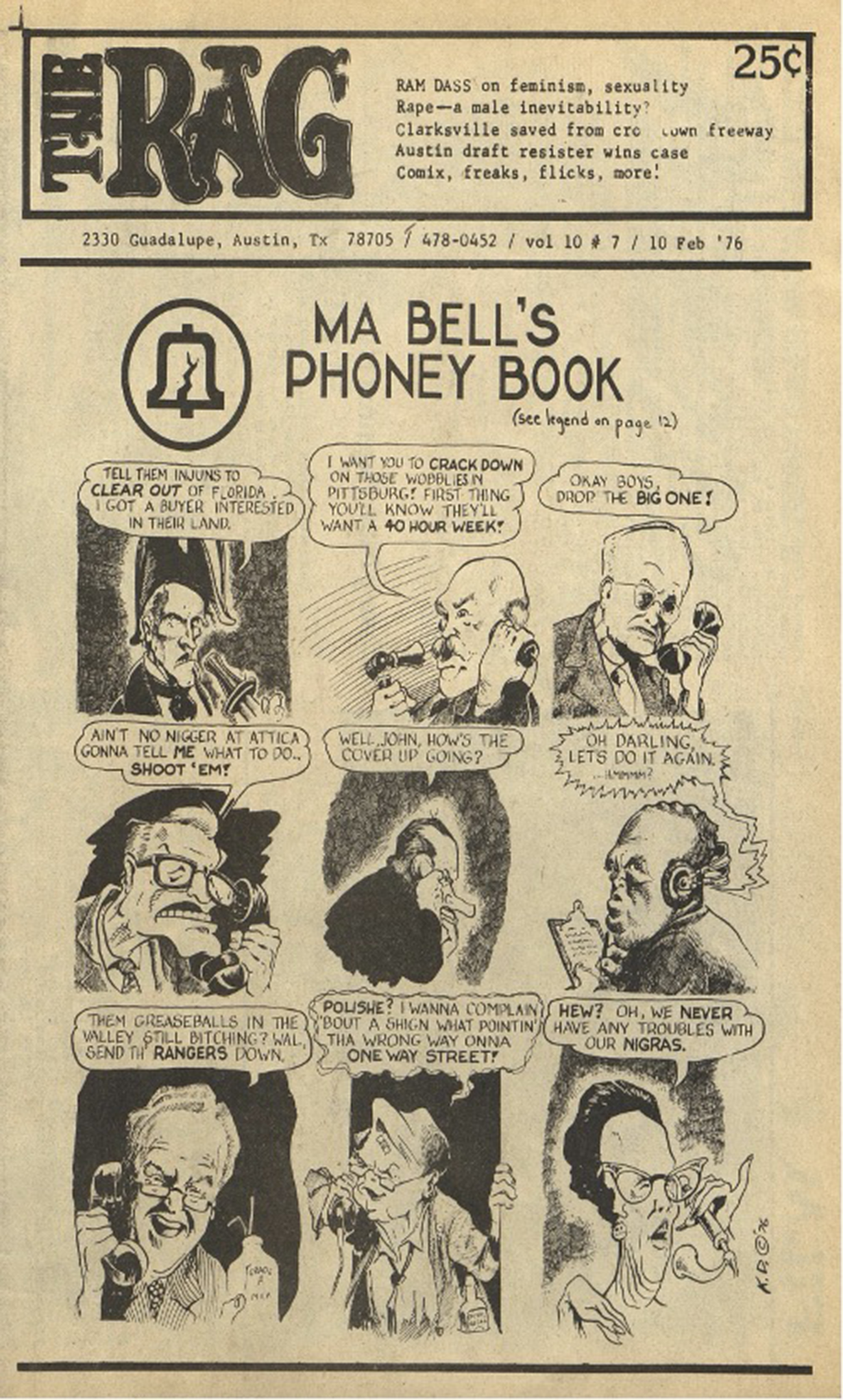

In the wider remit of New Left publications, information about phone phreaking was depicted simultaneously as the schematics for malicious pranks and the information required for technical mastery. In the Detroit-based magazine The Fifth Estate, for example, readers encountered phreaks as malicious pranksters ripping off the system (Figure 3) in the form of a jack-in-the-box clown. Popping out of a crate labeled “how to screw Ma Bell” and brandishing scissors, the phreak cuts the cord of a hissing Michigan Bell telephone. Other images depicted phreaks as adventurous musketeers “taming the telephone beast” (Figure 4). And Ramparts Magazine(Figure 5), the muckraking zine published out of San Francisco, published a guide to the Blue Box as a tool “virtually anyone and everyone” could use, providing all Americans with the opportunity to “regulate” the phone company at home.Footnote 75 In all three, the Bell System’s telephones were stylized as technological monsters deserving of regulation and democratic oversight.

Figure 3. Cover image from the March 1975 (vol. 10, no. 15) issue of Fifth Estate, a new left affiliated magazine produced in and distributed from Detroit, Michigan.

Source: Fifth Estate 10, no. 15 (March 13, 1975), cover page.

Figure 4. Image from an August 1974 (vol. 9, no. 13) issue of Fifth Estate, a New Left affiliated magazine produced in and distributed from Detroit, Michigan, depicting the Blue Box as a tool to “tame” the Bell System.

Source: Dennis Witkowski, “Taming the Telephone Beast,” Fifth Estate 9, no. 13 (August 22, 1974), 9-10.

Figure 5. The article header for Roy Oklahoma’s 1972 article in Ramparts vol. 10, no. 12.

Source: Roy Oklahoma, “Regulating The Phone Company in Your Home,” in “Legal Dope,” box 2019-050/14, AHP. Photo: camh-dob-035241_0001, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History.

These efforts to exploit the Bell System related to the Yippies’ previous attempts to manipulate the American media environment. YIPL was an extension of the New Left’s Youth International Party (YIP). YIP’s leaders advocated for politics led by youth using gimmicks, pranks, and media-grabbing tactics and guided by aspirations toward alternative ideals and institutions. The party member, or “Yippie,” would become a multipurpose activist in an era defined by new media. As Hoffman wrote, “If the press had created ‘hippie,’ could not we five hatch the ‘yippie’?”Footnote 76 The recurring theme of YIP’s activities became testing the relationship between protest and the media environment. “The commercial is information,” Hoffman wrote in his 1968 manifesto, Revolution for the Hell of It, and information in a mass-consumerist media environment could be manipulated.Footnote 77 Within Hoffman’s writing was an early insight about virality: “Media is free,” he argued. “Use it. Don’t pay for it. Don’t buy ads. Make news.”Footnote 78

The Yippies’ aspiration to make news and manipulate attention manifested in grand media-grabbing gimmicks. The first, an October 1967 anti-Vietnam War march on the Pentagon, ended with Hoffman proposing to “levitate” the Pentagon and perform an exorcism of its “evil spirits.”Footnote 79 New journalist Norman Mailer reported on the march in The Armies of the Night, where he described the throngs of Yippies as “legions of Sgt. Pepper’s Band,” suspended between reality and fiction, between “history and the comic book, between legend and television, the Biblical archetypes and the movies.”Footnote 80 “The aesthetic at last was the politics,” Mailer wrote.Footnote 81 Yippie Jerry Rubin argued much the same when he declared that “Rebellion begins on your face.”Footnote 82 Appearance, lifestyle, and aesthetics became political terrain. According to one popular countercultural refrain, “The revolution is the way you live your life.”Footnote 83

A year later, in protest of the 1968 Democratic National Convention’s “Convention of Death,” the Yippies held a “Festival of Life.” There, the movement’s leaders, or lead provocateurs, stressed a do-it-yourself politics premised on radical permissibility: “Amerika says: Don’t! The Yippies say Do It!” For the Yippies, the it was often absurd, contradictory, and far flung. “Free Speech is the Right to Shout ‘Theater’ in a Crowded Fire,” they advised. Theatrics, they hoped, would become “myth” and create “free advertising.”Footnote 84 Absurd acts themselves, Hoffman explained, worked to “disrupt the image” of an “orderly society.”Footnote 85 These tactics were displayed in Chicago, where the Yippies paraded a 145-pound domestic pig, Pigasus the Immortal, around town as a presidential candidate.Footnote 86 “If we can’t have him in the White House,” the Yippies declared, “we can have him for breakfast.”Footnote 87

For the Yippies, pranks, stunts, and gimmicks were substantive political actions that laid claim on public authority.Footnote 88 At the Chicago Convention, the Yippies circulated a list of broad demands that reflected everything from particular policy preferences to expansive revolutionary ideals: these included an end to the Vietnam War, full employment, the legalization of drugs, freedom for all Americans regardless of skin color, the abolition of money, widespread birth control, and new sexual liberation. A blank space for “what you want” invited readers to write themselves into politics.Footnote 89

The yawning gap between the specificity of some demands and the impossibly vague parameters of others permeated the Yippie approach to politics. At its best, this approach sourced political priorities from the crowd. As Yippie activist Judy Gumbo reminisced on the movement, Yippie strategy was essentially “anarchy with discipline.”Footnote 90 At its worst, however, critics alleged that Yippies represented the vague demands of drug-induced mobs and vacuous lifestyle consumers. Memoirs from the period suggest a universal apprehension of cracks in the social, political, and economic conventions that defined postwar American life. All signs suggested that the center would not hold. With characters like the Yippies in the headlines, journalist Joan Didion was right to observe that “Disorder was its own point.”Footnote 91

There can be no doubt that the Yippies dealt in political theater and drummed up disorder, but their dramatized departures from the American establishment were creative responses to a political landscape that appeared quite bleak, domestically and abroad. The Yippies saw the Bell System as a monopoly bringing the world to the brink. And by YIPL’s founding, those on the New Left had sharpened four critiques of the Bell System’s role within the wider American political system: its ties to the military-industrial complex, then embroiled in controversies over the war in Vietnam; its labor and business practices; reports of its surveillance practices; and the supposed conformity within its workplace. Phone phreaking, in turn, was styled as a tool to resist four forces within the American system.

Ma Bell at War, at Home, and Abroad

In the late 1960s and early ’70s, the New Left’s most salient critique of the Bell System focused on its ties to the U.S. government and the war in Vietnam. AT&T was one of the key beneficiaries of wartime booms in federal spending and a cornerstone of the military-industrial research system developed in the post-WWII period, to the extent that one journalist described the research relationship between the company and the government as a “marriage.” During World War II, Bell Laboratories designed, and Western Electric built, many of the cutting-edge technologies deployed in theaters of war. At home, Bell built U.S. missile defense systems, including Project Nike and the Safeguard Program, and constructed a private military telephone network, known as AUTOVON, that would ensure the “survivability” of the U.S. government and allow the president to deliver a “doomsday signal” to mobilize the United States’ missiles in the event of widespread nuclear warfare.Footnote 92 Bell’s relationship with the Pentagon was so close, in fact, that secretaries of defense and Pentagon officials occasionally blocked antitrust efforts targeting AT&T because of its central role in military infrastructure, especially the nuclear stockpile at facilities like Sandia National Laboratories.Footnote 93 It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that when social critic Lewis Mumford searched for a name for the ever-growing system of technologies mediating and controlling society in the late 1960s, he landed on “the Pentagon of Power.”Footnote 94 It was no coincidence that Western Electric, the “Makers of Bell Telephones,” were also the “Managers of the Nation’s Nuclear Stockpile.”Footnote 95

If Bell’s connection to the state was clear at home, it was glaringly obvious if Americans looked for evidence abroad. Starting in 1966, American consumers protested a 10% telephone excise tax that the government imposed to finance the Vietnam War. In 1967, the Committee on Nonviolent Action estimated that, combined with a 1% excise tax on automobiles, the U.S. telephone tax would raise $1.2 billion in the 1967 fiscal year. The Committee translated this sum into “about twenty days of killing in Vietnam.”Footnote 96

Protests against the telephone company’s connection to Vietnam coincided with historic labor action against AT&T. In the 1970s, AT&T was the largest employer of women in the United States. Over half of its total employees were women. Though 99.9% of Bell operators were women, these employees were systematically excluded from management and craft jobs. In 1970, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) petitioned the Federal Communications Commissions to reject a rate increase proposed by AT&T. The EEOC’s aim was to pressure Ma Bell to end its practice of exclusively hiring women for specific low-rung jobs in the company. This was well known: as journalist Sonny Kleinfeld quipped, AT&T was “the corporate personification of male chauvinism and racism.”Footnote 97 Meanwhile, the Communications Workers of America (CWA), “a powerful industrial trade union,” sought a new contract and better labor conditions amid AT&T’s nationwide transition to electronic switching—the technology that enabled phone phreaking to take off.Footnote 98

These conditions led to a CWA strike. In July 1971, over 500,000 AT&T workers declared a strike against the System. Strikers outside of Bell offices across the country printed signs demanding change: “women are relegated to the dullest jobs, paid sub-standard wages, and are treated like both small children and slaves … Ma Bell Is a Cheap Mother!”Footnote 99 For their part, YIPL and other New Left publications encouraged solidarity between phone phreaks and Bell employees. “Write us,” YIPL’s editors instructed Bell employees, with experiences of “working for the largest, most powerful piece of shit in the world.” Examples of “sexism, racism, anti-semitism, pigism, and any other ism you can think of” were encouraged.Footnote 100

YIPL’s first issue went to print while the CWA strike raged on. YIPL quoted CWA president Joseph Beirne on the practices of surveillance within the Bell System: “[T]he telephone industry has developed equipment for monitoring its operators, its service assistants, its commercial office employees,” Beirne stated, “in short, all its employees who deal with customers.” The result, he continued, was that American customers were being “monitored at the same time.”Footnote 101

Bell’s labor-monitoring practices aside, the possibility of wiretapping loomed large in American life. As historian Sara Igo shows, it was an “open secret” that anyone ranging from a hard-nosed detective to a Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agent could “listen in” on American phone calls.Footnote 102 As attorney Samuel Dash told a 1959 Senate subcommittee, “almost every police wiretapper, whether he be a plainclothesman or an assistant district attorney, if he is assigned to supervise wiretapping … has a contact in the telephone company.” This practice, he continued, was “condoned by the company itself.”Footnote 103 “The FBI plugs into Ma Bell,” someone would later write for the Yipster Times about the revolving door of contacts between the Bell System and American law enforcement.Footnote 104

Related to the Bell System’s government ties, labor practices, and role in the surveillance of citizens, the New Left saw Bell’s culture as the picture of postwar conformity. Its employee was the “organization man” incarnate, complete with a grey flannel suit.Footnote 105 Consider “Living in Butte with Mother Bell,” an essay about “the businessman’s dream,” working for “the grand mother of American business, the androgynous bid daddy: Ma Bell.” The writer, Rob Evans, describes his experience at the subsidiary Mountain Bell. “The Ma Bell mold presses ever more tightly about the worker,” Evans wrote. “He’s expected to work not simply at Mountain Bell or for Mountain Bell: he’s expected to work with Mountain Bell; but he must first accept the mold.”Footnote 106 AT&T’s executives, for their part, seemingly embraced Bell’s place in American life as the paradigmatic American corporation.Footnote 107 In 1967, for example, a junior executive at AT&T put it explicitly: “In the office we call it ‘The System,’ and use of the word ‘the’ means dogmatic finality. The wall comes up pretty fast when you start tampering with the way things are done within The System, and you either slow down and do things Bell’s way or knock your brains out.”Footnote 108 Or, as a seventeen-year employee of the Bell Telephone Company wrote in a magazine article reflecting on “life in the Bell System,” “the pecking order was clear.”Footnote 109

Taken together, the Yippies, CWA members, phone phreaks, and social critics saw the Bell System as the system. This view is captured by a 1976 cover image of The Rag, which visualized Ma Bell as the central nervous system channeling commands from the heights of American political, economic, and cultural power. (Figure 6) It depicted Andrew Jackson authorizing Native American removal; Richard Nixon covering up the Watergate scandal; business executives thwarting labor movements; and a grotesque caricature of an operator or FBI agent listening in on sexual intercourse. The telephone pictured here was a tool of American wrongdoing across time, space, and circumstance. Ma Bell, as civil liberties advocates quipped at the time, was Big Brother’s handmaiden.Footnote 110

Figure 6. Cover image from the February 1976 (vol. 10, no. 7) issue of The Rag, a new left-affiliated magazine produced in and distributed from Austin, Texas.

Source:The Rag 10, no. (Febraury 10, 1976), cover page.

Phreaks at Odds

Critiques of the Bell System in YIPL, Fifth Estate, Ramparts, Borrowed Times, and other New Left publications attracted readers for their rhetorical force and compelling imagery. In these pages, telephone lines were anatomized as the central nervous system in the body electric of an evil American empire, the tools of discipline and punishment for monopoly power, and the oppressive molding that clamped upon Americans through corporate culture and surveillance apparatuses alike. Collectively, these critiques rendered the Bell System into a symbol of the post-war American political order Hoffman and the Yippies sought to transform or topple with a microphone in one hand—and a Blue Box in the other.

From the outset, however, YIPL’s best-laid plans were subject to criticism from within and without. In the second issue, the magazine published journalist Russell Baker’s extended critique of Hoffman’s writing on the telephone system. “I wonder if you have really thought out the implications of the grand philosophical idea of destroying the telephone company,” Baker observed. After all, the Bell System’s very size and scope made Hoffman’s rip-offs possible. More important, Baker argued that participants in American counterculture and social movements required telephones. The American activist “needs a telephone the way a monkey needs a banana,” and telephones were “as much a part of his uniform as denim, dried lentils and a coiffure from Michelangelo’s Moses.” To wit, would “the next phone company,” one rebuilt after some unspecified act of destruction, tolerate the same level of activist use and fraud? Baker stated that “The present telephone company is the best of all possible telephone companies for the counter-culture.”Footnote 111

Hoffman responded by allowing part of Baker’s critique. It was true, he wrote, that “even us Yippies don’t wish to hatch our coast-to-coast conspiracies using dixie cups with waxed string stretched between them.” “As the level of technological development increases,” Hoffman suggested, the goal should be a “society free to all the people.” Such should be the role of a public utility, at least to Yippies like Hoffman. “Until AT&T and the other corporations really become public services,” Hoffman asserted, “we’ll continue to rip them off every chance we get.”Footnote 112

But Hoffman’s insistence revealed an instability at the heart of the Yippie-YIPL political program: what, exactly, would reconstitute the Bell System as a “public service”? Without specifics, critiques of the Bell System relied on a reflexive critique of anything that appeared to be part of “the system.” The system, as such, became a floating signifier.

These tensions in YIPL’s critiques of AT&T were evident early on. Indeed, some YIPL readers went too far in their exploits. In a letter titled “Monkey Warfare,” referencing Hoffman’s Steal This Book, a reader suggested using a mixture of epoxy glue for “imaginative forms of protesting,” such as cementing the keyholes and coin slots in locks, parking meters, and telephones. The editors responded that readers needed to ask themselves, “How can I fuck the pigs, and help my sisters and brothers?” Indiscriminate destruction of technological infrastructure, the editors suggested, could just as easily harm an average American in need of an emergency call.Footnote 113

While YIPL’s editors resisted the excesses of technical practices at the nexus of the New Left and phone phreaking, they often had much less to say about the interpersonal and manipulative techniques phreaks used to accomplish their goals. Besides multifrequency devices, a phreak’s greatest asset was his voice. As one phreak explained in a 1973 National Public Radio (NPR) interview, “some of the best phone phreaks don’t use any hardware at all. You can talk people in the telephone company into doing stuff for you.”Footnote 114 Talking to and manipulating others was dubbed “social engineering” by phone phreaks. The phreak Chesire Catalyst would later describe it as follows: “Engineering is when you take a wrench to a bolt, turn it, and something happens. Social engineering is when you take a telephone, get somebody who’s dumb as a bolt on the other end, and turn it.”Footnote 115 Or, as Hoffman wrote in his extensive notes on phreaking, “Lying is the most common phone ripoff ever invented.”Footnote 116 To some phreaks, people were instrumental to the practice and display of their technical pursuits.

If some of YIPL’s early political stances emphasized empathy and solidarity with Bell employees—especially during the waves of strikes in the early 1970s—others eroded the political salience of solidaristic ties between those within the Bell System and those without. In an article on avoiding Bell fraud investigations, for example, a YIPL contributor suggested phreaks take an aggressive stance toward Bell employees. “If a nasty supervisor bitch calls, be nasty offensive,” a piece in YIPL instructed. Bell’s “special security pigs,” part of the telephone security division, “spend their full time tracking us down” and deserved even more derision if encountered.Footnote 117 “This isn’t paranoia, it’s fucking good sense,” advised one phreak.Footnote 118 In the Detroit-based Fifth Estate, Dennis Witkowski advised readers about making free calls by being “aggressively persistent” and “demanding” an immediate connection to the requested number. If the operator refused, Witkowski advised readers to try and “threaten to destroy the phone booth and demonstrate your sincerity” by “banging the receiver on the glass while shouting angry curses.” If the operator hung up, you could always “try again with a different operator.”Footnote 119

The tension between Yippie aspirations and the realities of phreaking were highlighted by the performance of social engineering. The key to fooling telephone operators, YIPL and other New Left publications advised, was the sound of professionalism. Approximate the verbal behaviors of “Mr. or Mrs. Pig Businessperson,” advised a different publication.Footnote 120 Perform “like the distinguished businessperson.”Footnote 121 As a column in YIPL summarized it, “Always sound middle-aged, and in a hurry and pissed at operators, but willing to give her one chance.”Footnote 122 Hoffman also described how would-be phreaks could use readily available distinct code number (DCN) and code letters—to say nothing of laminated, wallet-sized guides titled “Steal This Phone Card,” complete with a picture of Hoffman himself (Figure 7)—to determine telephone credit card information with ease.Footnote 123 The most important trick was to convince operators of one’s identity. In a “firm, business-like tone,” Hoffman offered instructions down to the pacing and intonation of phreaking: “Operator this is a credit card call,” a phreak should state. “My credit card number is _ _ _ (pause) _ _ _ _ (pause) _ _ _ (pause) _.” Providing or faking individual names, phone booth numbers, and the name and city of the business would assuage the operator of any doubts. Above all, never “panic and hang up,” Hoffman wrote, press forward in a “mildly impatient and condescending” tone, and all would be smooth sailing.Footnote 124

Figure 7. A wallet sized “Steal This Phone Card” from the 1970s/’80s.

Source: “Steal this phone card,” in AHP. Photo: camh-dob-035263_0001, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

While techniques of social engineering signaled cracks in the foundation of solidarity between Yippies, phone phreaks, and Bell System employees, they also represented a new fulfillment of the old aspiration toward media manipulation demonstrated in Yippie feats of the late 1960s. Manipulation of the media environment toward political or prank-worthy ends was the Yippie’s signature move, and the telephone was nothing if not an integral component of the American media infrastructure. But what component parts of the media environment required manipulation? Were there meaningful differences between a news anchor and a telephone operator? If the Yippies saw in media the power to activate the American people—if readers were to take seriously that “YIPL is you”—the wanton manipulation of others seemingly undermined trust between parties and prevented the possibility of working together.

By 1973, these tensions were clear to any close reader. As the catalog of YIPL content swelled with aggressive phone phreak techniques and reflexive hatred of the system, some readers wrote to insist on a more complicated reality. In July 1973, a phreak named Nancy in Denver urged phreaks to “remember that the phone co’s lackeys are poor and starving like u, probably hate the phone co. as much as we do, and also are being exploited by it. They aren’t the enemy.”Footnote 125 The totalizing image of Ma Bell as the Phone “Kompany,” Nancy suggested, oversimplified a complex arrangement of companies and communities of employees who depended on regular paychecks.

Such tensions were no less visible when phreaks gathered later that year at the third annual phone phreak convention. There, a correspondent for The Guardian contrasted phreaks merely interested in telephones with “technological hippies,” such as the phreaks writing for YIPL, who saw Ma Bell as a monopolistic public enemy. To the journalist, however, the “‘Bell Telephone System’ as such doesn’t exist.” It was, as readers like Nancy suggested, a conglomerate of separate companies working in conjunction, rather than a malicious, monopolistic octopus wrapping its tentacles around all facets of American life.Footnote 126

When YIPL’s editors changed in 1973, the line between the technical and Yippie genres of phone phreaking shifted. Hoffman stepped back from his role at YIPL, most likely to pursue other projects. Shortly after, the magazine changed its name to TAP, an acronym for the Technological American Party and, later, the Technological Assistance Program. The editors described TAP’s purpose as that of “a people’s warehouse of technological information.”Footnote 127 As TAP’s editors refined a new editorial line, they purported to abandon politics altogether: TAP “is no longer Technological American Party. TAP is TAP. We are not a political party. We do not advocate anything, as an organization.” The journal would simply print any technical information that was otherwise “unavailable or unclear,” with priority for any information the editors deemed helpful to the “most readers.”Footnote 128 But politics is never far from technology. A potent strain resonant with the New Right soon reared its head in TAP’s pages.

The Changing Politics of Phreaking

Later that year, in December of 1973, a TAP reader recommended a catalog of electronics, surveillance units, weapons, law enforcement gadgets, and police equipment published by the group American Colonial Armament. “It’s a little right wingy in tone,” the reader observed, but it covered “just about everything Abbie mentions in Steal This Book.”Footnote 129 As the 1970s wore on and TAP attempted to uphold its status as a non-political entity, resonances between the Yippie style of politics and an ascendant conservative coalition grew louder. Old YIPL critiques of the Bell System morphed into libertarian critiques of the state and an anti-establishment political culture.

By the mid-1970s, some phreaks described their technical practices in a distinctly libertarian political vernacular. When a new TAP editor Jim Phelps, for example, styled his schematics for the “Fone Fucker”—a device for reminting up to 300 pennies per hour into dime-sized coins, all to fool pay phones—he described himself in a tradition of agitators who debased the state’s currency and “preceded its collapse.” But Phelps could hardly explain the sweep of the historical pattern he referenced in a short column in TAP. He recommended that readers turn to “anti-Amerikan-Establishment authors like Hayek, Hazlett, Rothbard, and von Mises.”Footnote 130 Thereafter, “Mr. Phelps” penned a regular column featuring militias, weapons, currencies, and body armor outfitters. Other readers wrote in to recommend magazines like Car & Driver as “one of the most libertarian straight publications I’ve seen.”Footnote 131 In turn, TAP became something of a recommendation algorithm for 1970s magazines catering to (mostly male) readers with the intoxicating thematic brew of heroic adventuring, masculine consumerism, war in exotic territories, and sexual conquest.Footnote 132

Meanwhile, by the mid-1970s, reporting and commentary on the women within TAP hit a wall. In 1976, TAP editor Tom Edison pleaded for any sign of female readership. “Surely somewhere out there in our readership,” he wrote, “are wives, sisters, girlfriends, and lovers who either are or know phone operators.” Sharing information with TAP, Edison suggested, would be a political act. “You’ll be doing a hell of a lot more for Women’s Lib than you even realize!”Footnote 133 But women readers, if there were any, failed to furnish a single letter, column, or piece of commentary while Edison and Phelps held sway.

Instead, contributors like Phelps pressed ahead with references to libertarian politics, free markets, and post-state futures. “Not only is a diamond ‘forever,’” he wrote, “so is the free market.”Footnote 134 In the apocalyptic or survivalist future Phelps envisioned, readers would need tools to survive. Hence, in an editorial entitled “Your Mission: Join Radio Free America,” Phelps wrote to celebrate the growth of amateur “guerilla radio” stations in the United States. Phelps fantasized about broadcasting John Galt’s speech from Atlas Shrugged during New York City’s electricity “blackouts” in the late 1970s. While Americans listened with battery-powered transistor radios for news, they would hear Ayn Rand’s Galt explain “what is wrong with The System and what can be done about it.” Referencing E. M. Forster’s science fiction and Roberto Vacca’s speculation about the next “dark age,” Phelps wrote that blackouts would continue until “the Final Blackout—when The System collapses of its own technological complexity and interdependence.”Footnote 135 Phelps lambasted readers to remember their role in the debates about the system. “And what are YOU doing, dear reader, to reduce YOUR dependence on the collapsing System?” Phelps implored TAP readers to do more than mess with Ma Bell: “I don’t mean cheating the utility and phone companies; I mean learning to get along without them. Get into Ham and CB radio and other methods of communication. Learn about alternate sources of power.”Footnote 136

Many TAP contributors continued to focus on phone phreaking, but Phelps explicitly pushed readers onto other subjects. In time, TAP’s shifting politics obscured YIPL’s original focus on telecommunications and the Bell System. Phelps wrote about the “tax revolts” of the 1970s, for example, describing the efforts of libertarian investment and tax advisers like Rene Baxter, who advocated for “tax refusal.” While readers who collected “welfare or unemployment” had no need for the information, Phelps argued that everyone else ought to take note. “You have Big Brother by the BALLS!” Phelps advised: “So squeeze him like he’s been squeezing you!”Footnote 137 Later, Phelps would compare IRS agents to members of the Gestapo. Still, he advised that “FDR (ugh!) once said ‘We have nothing to fear but fear itself.’” “[D]on’t fear the IRS,” Phelps wrote, “FIGHT THEM!”Footnote 138

Efforts to decenter the Bell System became more explicit. In a 1976 editorial on the “Biggest Monopoly of All” in American politics, Phelps was even more explicit: “No, it’s not The Phone Company,” he asserted. “It’s The Establishment. Big Brother. Da Guviment,” and “Big Brother’s victims must pay whether or not they receive any ‘service.’ Payments are called ‘taxes.’” The piece likened the American revolution to a “Libertarian REVOLUTION” and compared taxes in the 1970s to those in the 1770s. “We’re as bad off now as we were under King George,” Phelps wrote. But Phelps observed that a “Second Libertarian Revolution” was taking place, one that opposed “monopolies, victimless crime laws, taxes, gov’t secrecy” and asserted that “the gov’t which governs least, governs best!!”Footnote 139 The tactics of Phelp’s “revolution” remained unclear, but a bottom-of-page reference to Western-style gang violence might have raised some reader concerns. “Do you remember in the westerns, when the Sheriff would organize a Posse,” Phelps asked. “Can’t you just see Tricky and Spiro and all the rest of them, hung by the neck, the bodies remaining for the vultures?”Footnote 140

When some readers expressed concern about the reemergence of politics in TAP, to say nothing of opposition to Mr. Phelps’ particular politics, other editors shut down the conversation. As editor Tom Edison wrote, those readers who chafed against “the light social criticism” or references to political books and magazines should look for information somewhere else. Politics and technology were inseparable, he asserted. “Stay in your room and play with your Blue Box and yourself,” Edison wrote, “and one day, when the phone goes dead and the lights go out and you finally stick your head out the door to see just what the hell is going on, don’t be surprised to find people lying on the ground dying of pollution and radiation or people being swooped up in mass arrests thanks to S-1! Remember, 1984 IS closer than you think!).” Edison went on, “I don’t know where these vegetables live but today technology depends on social, political, and economic conditions and anybody who doesn’t recognize this is a fool!” Be foolish, he concluded, and “sub to Popular Mechanix!”Footnote 141 Even as they chastised phreaks to account for the “social, political, and economic conditions,” Edison and Phelps flattened those conditions into a binary of support for or opposition to big government. Though this libertarian turn in phreaking’s politics reflected, in some ways, a flourishing of anti-statist ideas first articulated by Hoffman, the late 1970s saw the atrophying of TAP’s ability to talk about politics in more complicated terms.

Indeed, in time, allusions to violence were matched by articles on tools for committing it: guns. In fact, TAP editors even invoked Hoffman alongside calls to bear arms. In a 1979 issue dedicated to “Abbie Hoffman and all our other revolutionaries, wherever they are,” TAP editor Mr. Phelps, self-described as a “lovable, larcenous, lecherous Libertarian,” assembled an issue focusing on opposition to gun control.Footnote 142 Across from the dedication to Hoffman, on the lefthand side of the front page, TAP displayed information from the Citizens Committee for the Right to Keep and Bear Arms, later renamed the Second Amendment Foundation, on a plan to pressure the Postal Service to issue a “pro-gun rights postage stamp.”Footnote 143 The article even included a cutout mailer to order stamps from the Committee. TAP thus connected its readers to one of a group of gun rights “grassroots warriors” who radicalized and mobilized Americans into the politics of “gun country” during the Cold War.Footnote 144

The reintroduction of politics into TAP was never without resistance, however. As fringe libertarian and new right organizations proliferated in the late 1970s, TAP’s editors occasionally voiced concern about overlaps between their readers and those communities. In a note on the “anti-semitic pro-Nazi bullshit” sold by the controversial publisher Loompanics, TAP’s editors observed that “many of these Free Enterprise/Survivorist types are just neo-fascists.” The editors did not intend to kick off a “big political argument,” but felt compelled to make the observation because “there are some anarcho-communist YIP type phreaks too.”Footnote 145 Yet TAP’s editors, and its readers, rarely reflected on the direction of their own publication. When they did, it was mostly halfhearted. In 1980, in a TAP editorial prefaced with “Politix: I know most phreax aren’t into this too much these days,” the editors argued that the “biggest danger of fascism right now comes further to the right then even Ronald Ray-gun.” The actors of concern were not survivalists, preppers, or militias, but Jerry Falwell—a “pseudo-Christian version of the Ayatollah Khomeini.”Footnote 146

Then too, many readers simply encouraged the libertarian turn in TAP’s politics. In 1977, one reader based in the United Kingdom wrote to thank TAP for the injection of “Libertarian stuff.” It was “exactly what I’m into politically,” the reader wrote. The material was a useful reminder that “phones aren’t everything.” “There’s only one thing a government should do for its people,” the reader went on, “and that’s to keep ’em free.”Footnote 147

Some readers wished for more emphasis on the themes of apocalypse and survival introduced by Phelps. John J. Williams, a TAP subscriber from New Mexico and president of a company called Consumertronics, wrote to TAP bluntly: “I think that your stuff is too esoteric,” and “most people don’t share your dislike of Ma Bell.” What would a hypothetical average reader think of TAP if Williams, who held an M.S. in electrical engineering and owned a consumer electronics business, “still get[s] lost on some of your articles”? TAP’s politics were simply unpopular: “1960s are gone,” Williams wrote, “this is ‘Looking-Out-For-No.1 Time.” An “obsession” with utilities like AT&T, Williams wrote, would make for a “limited financial future.” The subject du jour was “SURVIVAL.” “I have found,” Williams relayed, that many American consumers had come to expect “Armed Rebellion” “Total Economic Collapse,” “and/or Foreign Power Invasion.” All these specters loomed large in the imagination of Consumertronics customers according to its owner; all signs pointed to catastrophe “very soon.” “So don’t be alarmed if they don’t get excited about credit card calls and red boxes,” Williams continued. “Change your format to reflect this change in people’s interests and objectives,” he advised, and TAP would surge.Footnote 148 1984 did not spell the end of civilization. But that year the Bell System was broken up in a federally mandated divestiture—and TAP’s New York office shuttered its doors.

Phreaking’s Afterlives in American Politics and Culture

TAP ceased publication in 1984. But collapse was, perhaps, unsurprising to close readers of previous issues. Throughout the mid- to late 1970s, TAP’s editors lamented declining subscriptions and disengaged readers. As Phelps himself put it, “the initial fascination has worn off.”Footnote 149 Beyond faded polish, points of possible explanation for decline were plenty: the Bell System’s technology improved rapidly, requiring ever-more technically sophisticated articles prone to losing reader interest; labor settlements and the end of the war in Vietnam blunted the bite of the demands that animated YIPL in the 1970s; editorial priorities changed such that TAP ventured into already saturated content spaces while leaving longtime readers, who were primarily interested in telecommunications, uncertain about the magazine’s direction.

At the same time, external factors played an important role. In the late 1970s, the telephone system became harder to access. The system itself fractured into smaller units, especially after the Bell breakup in the 1980s. And a steady clip of wire fraud prosecutions discouraged would-be phone phreaks. Evolving computer technologies, too, attracted many phreaks into the new (though intimately connected) electronic playground of microcomputing. Indeed, computers were connected through the telephone system, offering the intellectually curious and politically active phreak new opportunities for experimentation. Yet, TAP seemed to miss the opportunity to explore those connections. “[T]he more we understand computers and other implements of modern societal control, the better chance we have to subvert them,” one TAP contributor observed. But the financial and educational resources required to operate a computer meant that “there aren’t many revolutionary computerfreaks.” Information sharing, in the style of YIPL in the early 1970s, could reshape this reality. Yet TAP’s readers constantly wondered why the journal did not publish more on computers and computer hacking. “We have the medium (TAP), but WHERE’S THE INFORMATION?” The reader concluded: “WHATDAFUCK?”Footnote 150

But YIPL-turned-TAP was, in some ways, vexed from the beginning by its Yippie provenance. TAP, in this sense, shared a fate with Yippie politics writ large. By the early 1970s, the Yippies were in sharp decline. Hoffman and Rubin were no longer spokespeople.Footnote 151 The core group of organizers devolved into a “honeycomb of cells” scattered across the country.Footnote 152 Then too, shifts in the practices and perceptions of TAP mirrored those of Hoffman himself. As Hoffman’s biographer notes, by the late 1980s, Hoffman was “increasingly part of the system.” His actions looked rehearsed; his words rang hollow. It was as if he read from the script of a “movie revolutionary and a matinee idol of defiance.”Footnote 153

At first, memory of YIPL and TAP fared no better. In early 1985, for example, a reader of Popular Communications wrote to that magazine’s editors asking about the “phone phreak” publication known as TAP. “Have you ever heard of it?” The editor even lauded the publication as “well done.” Yet the same editor lamented TAP’s “major shift in emphasis away from telecommunications” and toward “silly material relating to the preparation and use of street drugs.”Footnote 154 Others offered more nuanced remembrances. In 1988, a reader letter in Monitoring Times recalled a “group called TAP in New York” and its “fun anarchy.”Footnote 155

But TAP’s Yippie origins were not without devotees. In 1984, the heir to YIPL/TAP’s publishing on phone phreak culture came in the form of 2600: The Hacker Quarterly. Named for the 2600Hz tone phone phreaks used to access Bell’s long-distance telephone network, 2600 completed the synthesis of interests in telephony and computing that TAP failed to grasp. In 1989, 2600’s founding editor, the hacker Eric Corley, who went by Emmanuel Goldstein, remembered TAP and eulogized Hoffman. YIPL/TAP, he wrote, was “the first publication to look at technology through hacker eyes.” Indeed, it was “doubtful” that 2600 would exist, the editorial continued, if previous magazines had not paved the way.

After Hoffman committed suicide in 1989, phreaks and hackers dedicated their many words to eulogizing Hoffman.Footnote 156 Corley was no exception. Though Hoffman never “hacked” into computer systems, Corley dubbed him “a hacker of the highest order.” Hoffman had earned this title because he “hacked authority” through the Yippies and TAP, and, in the process, stood “up to the ultimate computer system known as Society.” Authorities of the 1960s and 1970s treated Hoffman then as they treated computer hackers in the 1980s: as a “pest” who never feared “point[ing] out the flaws” in society.Footnote 157 For all the nostalgia in their remembrances, by 1989, 2600’s editors admitted that Hoffman’s influence was decidedly limited. “We’re sorry he never really seemed to reach the younger generation,” the editors wrote. Still, 2600 advised its readers to pause when “playing with a computer somewhere” and “say hello to Abbie. He’ll be right there.”Footnote 158

The idea of Hoffman and the phone phreaks of the 1970s became a founding mythology for the hackers, crackers, phreaks, and digital misfits who coalesced into a “computer underground” in the late 1980s.Footnote 159 The ensuing decades saw no fewer than four editions of a Steal This Computer Book, which introduced computer users to ideas about hackers and computer security, or Steal This File Sharing Book, wherein readers learned how to peruse the “warez” of pirated software from dominant (and perhaps monopolist) corporations like Microsoft.Footnote 160 The Webster’s New World Hacker Dictionary even styled Hoffman and YIPL as foundational for modern hacker culture.Footnote 161 In the 1990s, debates about the nature of hacking even erupted between so-called “Bellheads” and “Netheads,” or hackers reared in the phreak’s day versus those who came of age on the electronic bulletin board systems of the 1980s and early 1990s.Footnote 162 The phreak’s techniques, gimmicks, and Yippie-inspired penchant for the dramatic prank went on to shape the computerized countercultures of the 1980s, guiding what communities of hackers saw as socially and politically viable on the horizons of cyberspace.

More importantly, Hoffman continues to influence hackers. Take the hacktivists within the unruly global hacker group, Anonymous. Jeremy Hammond, for example, cut his hacktivist teeth by founding and editing a website called Hack This Zine, an homage to Hoffman’s work, and hacking conservative websites.Footnote 163 Like Hoffman, Hammond’s writing blended both technical expertise and political commitment. From 2013 to 2020, Hammond was in prison for hacking a private intelligence firm, Stratfor, and leaking data to Anonymous. As one fellow hacker told Rolling Stone, Hammond was nothing less than a “modern-day Abbie Hoffman.”Footnote 164 Such legacies of the political phreaking Hoffman represented, it seems, will continue to surprise.

In tracing the evolution of phone phreaking from a New Left-inflected act of resistance against the Bell System to a touchstone of libertarian hacker culture, we complicate the neat periodization of American political and technological change. Phreaking’s early entanglement with antiwar activism, labor struggles, and critiques of monopoly capitalism underscores how technical practices are embedded within broader movements for social transformation. Its later adaptation into a politics of individual autonomy and technological resistance reveals the porous boundaries between the New Left, libertarianism, and hacker communities. By reading phreaking as both a material intervention in the infrastructure of American telephony and a symbolic gesture toward reimagining “the system,” we see how users, activists, and tinkerers alike participated in shaping the meanings and possibilities of technology in modern America. This trajectory not only reframes the origins of hacker culture but also challenges us to see technological practice itself as an enduring—and contested—form of political action.