1. Introduction

Financial aid programs have been extensively evaluated in the past twenty years. While they promise to increase access to higher education for lower-income students and enhance social mobility, the vast amount of papers published on the topic struggle to reach a consensus on their effectiveness. One important aspect of the problem is the difficulty to compare findings across programs and settings and to understand how context-dependent the findings are. This paper attempts to provide answers to those questions by analyzing an experiment that provided exogenous types and amounts of post-secondary aid to a diverse population of students and exploring the variability of the impacts across socioeconomic and institutional contexts. The experiment was implemented in 2008-2009 among 1,248 high school students living in four different Canadian provinces (Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and Saskatchewan). We tracked students ten years later and collected data on a large range of educational and financial outcomes.

As part of the experiment, students made a series of binary choices between immediate and unconditional cash, and financial aid to be provided conditional on enrolling in a post-secondary program within the next two years, with varying amounts of cash and aid across questions. At the end of the experiment, one choice was randomly picked, and the corresponding amount of cash or financial aid was offered to the student. We leverage the exogenous variation in financial aid induced by this design to explore the short and medium-run impacts of financial aid on students’ outcomes.

The literature studying the impacts of financial aid on students’ achievement and future outcomes has been a very active area of research in the past twenty years, in the U.S. primarily, but in other parts of the world as well (see Dynarski et al. (Reference Dynarski, Page and Scott-Clayton2023) for a recent review). Our paper contributes to that literature by combining several features that we believe are unique to our study: the exogenous variation in the financial aid amounts and types induced by the design of the experiment, the sampling of a general population of students, and the collection of long-run follow-up data on a variety of outcomes. Due to the eligibility criteria governing the allocation of financial aid in natural settings, a vast majority of papers aimed at assessing the causal impacts of existing aid programs rely on regression-discontinuity designs, which focus on a specific population of students falling around the eligibility threshold (see the early work of Van der Klaauw (Reference Van der Klaauw2002) or more recent examples such as Card and Solis (Reference Card and Solis2022), Gurantz (Reference Gurantz2022), Aguirre (Reference Aguirre2021), Eng and Matsudaira (Reference Eng and Matsudaira2021), Bettinger et al., (Reference Bettinger, Gurantz, Kawano, Sacerdote and Stevens2019), Denning et al., (Reference Denning, Marx and Turner2019), Scott-Clayton and Zafar (Reference Scott-Clayton and Zafar2019)). While providing a credible identification strategy, this approach makes the extrapolation to different student populations and contexts challenging and limits the exploration of heterogeneity in financial aid impacts. A few recent papers tried to overcome those limitations by relying on randomized designs such as Angrist et al. (Reference Angrist, Autor, Hudson and Pallais2015) or Angrist et al. (Reference Angrist, Autor and Pallais2022), who conducted a randomized evaluation of the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation’s scholarship program in Nebraska and found positive effects on enrollments, especially in four-year programs, and higher Bachelor’s degree completion, with stronger effects on students historically less likely to attend college. Another recent example is Carlson et al. (Reference Carlson, Elwert, Hillman, Schmidt and Wolfe2019) and Carlson et al., (Reference Carlson, Schmidt, Souders and Wolfe2025), who find positive effects of grant offers among Wisconsin college students on GPA and persistence, but limited impacts on degree completion. In the Canadian context, Renée (Reference Renée2025) evaluates the Future to Discover experiment and finds positive impacts of grants on four-year college enrollment but no effects on subsequent graduation and longer-term labor market outcomes. Our paper expands that literature by not only looking at the short and long-run impacts of financial aid but also exploiting the diversity of our sample to explore the interaction between financial aid and institutional and socioeconomic contexts.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, after providing some background information on the study, we present the experiment and data in more detail. Section 3 describes our empirical strategy and discusses our findings. Section 4 provides concluding remarks.

2. Experiment

2.1. Context

The experiment, referred to as the Willingness to Borrow project, was financed by the Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation, and conducted by the Social Research and Demonstration Corporation (SRDC) and the Centre Interuniversitaire de Recherche en Analyse des Organisations (CIRANO) in 2008 and 2009 in four Canadian provinces: Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and Saskatchewan. It was part of a series of research projects aimed at favoring access to post-secondary education for Canadian students. Students in our sample were in 12th grade or CEGEP (Quebec students) at the time the experiment took place.

Although the vast majority of post-secondary institutions in Canada are public and benefit from government funding, higher education systems differ from one province to another in terms of the amount of funding public universities receive and in terms of the tuition fees they charge. Average annual undergraduate tuition fees for Canadian full-time students in 2008-2009 were 3,238 CAD in Manitoba, 5,667 CAD in Ontario, 2,180 CAD in Quebec, and 5,064 CAD in Saskatchewan.Footnote 1 Moreover, Quebec tends to have a more generous financial aid system compared to the other three provinces.

Ten years later, we partnered again with SRDC to collect follow-up data from the individuals who took part in the 2008-2009 study and explore how the financial aid some students received following the experiment affected their post-secondary education and finances.

2.2. Data

The study consists of five types of data: parental and student surveys collected at baseline, an artefactual field experiment, a numeracy test, payment records corresponding to the choices made during the experiment, and a follow-up survey. Of the 1,248 students who initially participated in the baseline survey and experiment, we obtained follow-up data in the 2020-2021 survey for 512 of them. This section focuses on the presentation of the experiment. More details on the other data sources and a presentation of the sample’s characteristics can be found in Appendix A.

The experiment is the main originality of the study. It was conducted after the students completed the baseline survey and it contains three parts: two series of questions aimed at measuring time and risk preferences and a series of 22 binary choices between different amounts of cash to be provided within a week, and different types and amounts of financial aid packages (grants, loans, or mixtures of grants and loans) to be provided conditionally on enrolling in full-time post-secondary education.Footnote 2 Financial aid provided within the experiment could be combined with financial aid coming from another source outside of the experiment, and loans were offered at the same rate as governmental institutions. This paper focuses on the 22 binary choices on financial aid. Appendix B shows how the choices were presented to the students.

Table 1 below presents the different amounts of cash and aid for each of the 22 choices, as well as the proportion of students who chose aid over cash. Note that for packages including a mixture of a grant and a loan, the amount of each type of aid is reported in the two distinct columns corresponding to grant and loan amounts but the two were offered as a bundle. For instance, the sixth row corresponds to a binary choice between $25 cash and a $2,000 aid package split between a $1,000 grant and a $1,000 loan. The asterisks refer to income-contingent loans. As expected, we see that for a fixed amount of financial aid, as the amount of cash increases, the take-up of financial aid decreases, and symmetrically, for a fixed amount of cash, as the amount of aid increases, the take-up increases. The table also reveals that students prefer grants over hybrid packages of the same amount, and they prefer hybrid packages over loans. It should be noted that the amounts of aid offered in the experiment are high, given tuition fees in Canada (see Section 2.1). A $2,000 grant, for instance, covers approximately one year of undergraduate studies in Quebec.

Table 1 Take-up rates for the different amounts of grant and/or loan versus cash offered

Note: The first three columns indicate the amounts of cash payment, grant, and loan offered for each of the 22 binary choices. The last column gives the proportion of students who chose the grant and/or loan rather than the cash payment among the baseline sample (N=1,248). The asterisks indicate income-contingent loans.

At the end of the experiment, one of the choices was randomly drawn, and the corresponding amount of cash or aid was given to the student, ensuring that choices were incentivized. This is also the source of exogenous variation on which our identification strategy relies to estimate the impact of financial aid on different outcomes.

However, following unexpected issues in the management of loans, SRDC decided to transform all financial aid offers into grants, meaning that students received grants corresponding to the amount of aid they had chosen in the binary choice that was drawn, regardless of whether that choice was a loan, a grant, or a hybrid package. Students found out about the change only after they contacted SRDC to arrange for the payment of the aid, after enrolling in a post-secondary program. For our analysis, this change implies that we will group all types of aid packages together when looking at post-enrollment outcomes and interpret the receipt of financial aid as a reduction in the cost of education.

3. Empirical analysis

3.1. Econometric specification

Our empirical approach leverages a key feature of the experimental design: the random draw of one of the binary choices made by the students, as described in the previous section. This unique design generates exogenous variation in the amount and type of financial aid offered to students, allowing us to estimate their causal impact. We follow two estimation strategies corresponding to two types of subsequent educational outcomes: 1. the decision to enroll in post-secondary education and the decision about the type of program to enroll in, which were made before the payment of the aid was effective, as payments were conditional on enrollment, and 2. post-enrollment outcomes. For the former, we regress different binary variables corresponding to different types of programs on the amount of grant or loan offered during the experiment:

where G, L, and GL are the amounts of grant, loan, and hybrid packages offered, and X is a vector of covariates including the 22 choices made by the students during the experiment, their baseline numeracy score, as well as another set of control variables from the baseline surveys (sex, parental income, whether the school was in a rural area or not, a mastery score assessed by the Pearlin scale, a school motivation score, a self-evaluation of math and verbal skills, and a score capturing students’ level of information on the labor market).

Our estimation strategy relies on the assumption that, conditional on the 22 choices, the amount of financial aid offered is exogenous, allowing us to identify the causal effect of increasing financial aid offers on enrollments. To assess the plausibility of this assumption, we tested the correlation between different students’ characteristics and the amounts of grant, loan, and hybrid packages offered, conditional on the 22 choices, on the baseline and follow-up samples. Results are presented in Appendix C and show that most baseline characteristics are not significantly correlated with financial aid, even in the presence of attrition, which supports the plausibility of our experimental design.

We should also note that 7% of our sample (37 students out of 512) systematically chose cash over aid in all 22 choices. These students had a zero probability of receiving financial aid and therefore do not contribute to the estimation of the impacts of financial aid offers (see Rubin and Imbens (Reference Rubin and Imbens2015)). If these students were students who had no intention to enroll in post-secondary education, it implies that our estimated impacts only apply to a population of students who had some expectation to attend post-secondary education.

For post-enrollment outcomes, we use a two-stage-least-squares (2SLS) strategy to estimate the impact of the amount of aid effectively received and instrument the effective amount of aid received by the amount offered. As explained in Section 2.2, all students who received financial aid post-enrollment received a grant, since loans were systematically converted into grants. Our specification is the following:

where G, L, GL, and X are the same variables described above, and A is the amount of financial aid (grant) received by the student. The identification strategy here relies on the assumption that, conditional on the 22 choices, the amounts offered are uncorrelated with unobserved determinants of the outcomes, ξ (exclusion restriction). We expect this assumption to hold by virtue of the random draw, and, although we cannot directly test it, the analysis presented in Appendix C tends to provide empirical support for it. We also show in the next section that the amounts of aid offered are highly correlated with the amounts received, confirming that the instruments are not weak.

3.2. Results

We first present in Table 2 the effect of financial aid offers on enrollments in the overall sample, distinguishing between three types of binary variables. Thefirst variable indicates that the student enrolled in any post-secondary program after high school, the second variable indicates that the student enrolled in a two-year college or other short programs, and the third one indicates that the student enrolled in a four-year college, covering the three possible options the students could report for their first post-secondary program.Footnote 3 The three columns correspond to the three types of financial aid offers (in thousand dollars). The results suggest that the effect of an increase of $1,000 in the amount of grant offered is close to zero on all three enrollment variables. While imprecisely estimated, loan offers have larger effects, reducing the probability of enrolling in a four-year college by about 6.8pp, in favor of two-year colleges (+5.2pp). The effects in the overall sample are noisy and do not allow us to draw robust conclusions. However, heterogeneity analyses reveal that this substitution effect masks important differences across provinces, which we discuss in further detail at the end of this section.

Table 2 Impact of financial aid offers on enrollments

Note: OLS regressions of each enrollment variable on the three types of randomly drawn financial aid offers (in thousand dollars). The first three columns give the effect of each type of offer on the different enrollment variables, with the standard errors in parentheses below. * for p-value < 0.1, ** for p-value < 0.05, and *** for p-value < 0.01. Column N gives the number of observations in the regression. Control variables: 22 binary choices and a set of baseline variables described in section 3.1.

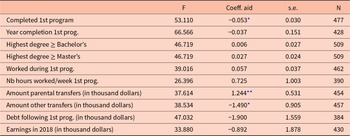

Next, we focus on the impact of effectively receiving financial aid on post-enrollment outcomes related to the completion and financing of post-secondary education, as well as earnings ten years after the experiment. Our approach uses 2SLS regressions of outcome variables on the amount of aid received (in thousand dollars) instrumented by the amount of aid offered with the lottery. Table 3 presents the results in the overall sample, with the different outcomes on each row. The first column shows the F-statistics of the corresponding first-stage regression. The second column provides the estimates with their standard error in the third column.

Table 3 Impact of receiving financial aid on studies and finances

Note: 2SLS regressions of each variable on the amount of financial aid received by the student instrumented by the amount of financial aid offered through the lottery. The first column gives the F statistics of the first-stage regression. The second column gives the coefficient of the amount of aid received (in thousand dollars), with the standard error in the third column.

* for p-value < 0.1, ** for p-value < 0.05, and *** for p-value < 0.01. The fourth column gives the number of observations in the regression. Control variables: 22 binary choices and a set of baseline variables described in section 3.1.

The first noticeable result is the high value of the F-statistic, above 25 in all regressions, confirming the strength of the instruments.Footnote 4 Turning to the first set of outcomes related to post-secondary programs, the results show that an increase of $1,000 in financial aid leads to a decrease of 5.3pp in the probability of completing the first program. Several possible unintended effects of financial aid provision could explain this result. One hypothesis is that financial aid led students to choose lower-quality post-secondary institutions, as found in Bucarey et al. (Reference Bucarey, Contreras and Muñoz2020), or induced them to choose a different curriculum, as found in Sjoquist and Winters (Reference Sjoquist and Winters2015), for instance. Another possibility is that increases in financial aid change the composition of students attending post-secondary education, increasing the share of students with lower probabilities of persisting to completion. As discussed below, the negative effect on completion is driven by students whose parents did not go to college. While those students may have similar skills (we control for numeracy scores in all regressions, in particular), they may still face higher barriers in navigating the post-secondary education system.

On the other hand, we do not find any significant impact on the time needed to complete the first program, nor on the probability of completing a program above the Bachelor’s or Master’s level. The impacts on the probability of working during the first program or the number of hours of work are imprecisely estimated.

The next set of outcomes relates to the financing of post-secondary education. We first examine parental transfers, measured by asking students about the amount of money they received from their parents to finance their studies during their first program (excluding accommodation costs), and that they do not have to pay back. Another outcome is the amount of other transfers received by the students, which covers grants or scholarships received from the government, from private sources, money received from other family members, and any other money students received to finance their studies during their first program. The amount of debt is measured by simply asking students how much student debt (defined as money borrowed to pay for their studies) they had accumulated by the end of their first program. All three measures are adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Table 3 shows that parents significantly increase financial transfers with the receipt of financial aid, while transfers coming from other sources are crowded out. For an increase of $1,000 in financial aid, parents increase the amount of money provided to their child by $1,244, suggesting that parental transfers act as complements to financial aid. The amount of student debt at the end of the first program goes down slightly with financial aid, but the effect is not statistically significant.

Finally, and in line with the null or slightly negative impacts of financial aid on educational achievements, the impact on earnings around the age of 30 (measured as the personal total pre-tax earnings in 2018) has a negative sign but is not significantly different from zero.

As the effect of financial aid likely differs across institutional and socioeconomic contexts, we conducted further analyses to explore the potential heterogeneity of our findings. We focused on two dimensions. First, we distinguish Quebec from the other three provinces where the cost of education is substantially higher (see Section 2.1). Second, we distinguish between students having at least one parent who went to university and students whose parents did not go to university to assess the potential of financial aid to foster intergenerational mobility. The tables are presented in Appendix E, with the first two showing the OLS estimations on enrollments and the last two showing the 2SLS estimations on educational outcomes and finances.

While the impact of the grant offers does not reveal any clear heterogeneity, it is interesting to note the more nuanced impacts of loan offers. Table A.7 shows that in Quebec, those offers induce a substitution between short and longer studies, with a clear negative impact on the probability of enrolling in a two-year college and a positive (although noisy) impact on the probability of enrolling in a four-year college. In other provinces, the loan offers produce opposite results, increasing the probability of enrolling in short studies at the expense of longer studies. The differences in effects (columns P-val Δ) are significant at the 5 and 10% level, respectively, for two-year and four-year college enrollment. Although several potential mechanisms could be at play, one can note that an increase by the same given amount in loan covers a higher share of the tuition fees for a four-year college in Quebec, on average, compared to other provinces, as discussed in Section 2.1, which could contribute to the difference in enrollment we observe between the two subgroups.

It is also possible that the returns to different types of studies vary across provinces, which can play an important role in the effect of loan offers that, at the time students made their enrollment decisions, had to be paid back. Our baseline survey provides some evidence that students in provinces other than Quebec are more likely to perceive positive returns to two-year colleges compared to Quebec students. When asked if ‘People who get a two-year college education will make more money over their lifetime than those who just get a high school education.’, 76% of the students in our follow-up sample agree in provinces other than Quebec versus 65% in Quebec, while there are no clear differences in the perceived returns to four-year college across provinces. Similarly, 36% of the students from other provinces declare that ‘[they are] hesitant to undertake a four-year college education because of the amount of debt [they are] likely to accumulate by the time [they] graduate’, compared to 29% in Quebec.

Table A.8 also indicates that increases in loan amounts have a negative effect on four-year college enrollment among students coming from lower-educated families, while having a positive effect on more advantaged students, but the estimates are not statistically significant, and the difference between the two is significant at the 20% level only.

Looking now at post-enrollment impacts, the analyses reveal that the reduction in the probability of completing the first program of study is driven by students coming from lower-educated families, with a reduction of 13.8pp compared to 1.7pp in the rest of the sample (Table A.10). The table also indicates that they increase their number of hours worked during that program while their more advantaged peers reduce them with increases in the amount of financial aid received, but the estimates are imprecise and should be interpreted with caution (the difference between the two effects is significant at the 17% level only). The complementary effect of financial aid on parental transfers is also substantially stronger among students whose parents did not go to university (Table A.10) and in the provinces of Manitoba, Ontario, and Saskatchewan (Table A.9), the latter difference being significant at the 10% level. Once again, one possible interpretation of the difference across provinces could be that post-secondary studies are, on average, less costly and the financial aid system more generous in Quebec compared to other provinces, where students might be more likely to turn to their parents to complement the aid they receive.

We can last note an increase in the probability of completing a Master’s degree or higher with a reduction in the cost of education among students with at least one college-educated parent, as well as an increase in earnings around the age of 30. Those estimates, however, remain imprecise and should be interpreted with caution.

4. Conclusion

This paper analyzes the short and medium-run impacts of a unique experiment conducted among high-school students in four different Canadian provinces. By leveraging the exogenous variation in the amount of financial aid offered to the students, we show that reductions in the cost of education have, on average, modest effects on education choices and finances. We also find that such reductions do not lead to a decrease in parental transfers. On the contrary, parental transfers increase significantly, in particular among students coming from lower-educated families and in provinces where the cost of education is higher. Heterogeneity analyses reveal additional interesting differences across contexts and socioeconomic backgrounds. While financial aid policies are often seen as a tool to provide access to post-secondary education to students coming from more disadvantaged environments, our results suggest that students with more educated parents could benefit more from the aid in our setting. Although the precision of the estimates is limited, our results indicate that when offered financial aid, more advantaged students enroll in longer studies, work less while studying, and their longer-term earnings are increased. Opposite results can be observed among students coming from lower-educated families.

Our findings point to several directions for future research. One is to explore how financial aid programs affect the education students pursue through a more qualitative lens. Do they lead students to apply to higher-quality institutions? Do they lead them to choose different types of majors? Our analysis and a large share of research on financial aid focus on quantitative outcomes. Better understanding the impacts on qualitative outcomes could help unpack some of the unintended consequences of those programs and better inform policy discussions. Another understudied area of research is the interaction between public and parental transfers. Our results show sizeable responses to financial aid among lower-educated parents. Future research could explore the underlying mechanisms behind this novel result to shed light on the ways financial aid programs intervene in the decision-making process about post-secondary education and its financing within families.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/esa.2025.10025.

Acknowledgements

We thank the late Claude Montmarquette (CIRANO), who was at the inception of the “Willingness to Borrow” project, for introducing us to the experiment analyzed in this paper and allowing us to use the data. We also thank the Social Research and Demonstration Corporation (SRDC), which was in charge of collecting the data for the initial experiment as well as for the follow-up survey. Data and codes used in this paper can be obtained from the authors upon request.

Statements and Declarations

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.