Introduction

The European Union (EU) is repeatedly found to suffer from a communication and participation deficit, perceived as far away from people’s lives, providing little room for directly experiencing European politics. Social media were welcomed as a promising way to communicate to European publics directly, circumventing the gatekeeping position of mass media (De Wilde Reference De Wilde2019) and giving EU institutions greater agenda-setting power regarding their own public image (Michailidou Reference Michailidou2008). In 2023, social media platforms were used by almost 60% of individuals in the EU (Eurostat 2024), demonstrating their potential to reach a broad audience, thereby increasing opportunities for experiencing and engaging with EU politics.

Social media communication is not only shaped by the sender (Marwick and Boyd Reference Marwick and Boyd2011; Bruns Reference Bruns2013) but also influenced by the affordances of different platforms, guiding how users can engage in terms of liking, sharing, or communicating in the comment section (Evans, Pearce, Vitak, et al. Reference Evans, Pearce, Vitak and Treem2017; Kakavand Reference Kakavand2024). Moreover, social media often follow a visual logic which is generally found to increase engagement (Highfield and Leaver Reference Highfield and Leaver2016). Images are more likely to attract (immediate) attention and present information on a holistic-associative basis, communicating meaning more comprehensively (Graber Reference Graber1996; Autenrieth and Neumann-Braun Reference Autenrieth and Neumann-Braun2011; Schill Reference Schill2012; Vraga, Bode and Troller-Renfree Reference Vraga, Bode and Troller-Renfree2016; Leaver Highfield and Abidin Reference Leaver, Highfield and Abidin2020). Visual communication has, therefore, gained relevance in political communication (Farkas Reference Farkas2023) and is a promising route for increasing public visibility for, and potentially also engagement with, a political entity with contested democratic credentials like the EU. Accordingly, our study is guided by the question: To what extent do different (visual) content features in EU social media communication enhance user engagement?

We focus on (1) the image types and other visual features used in the social media communication of EU institutions and (2) user engagement, accounting also for (3) differences across platforms. So far, the literature focuses on descriptive analyses of EU social media contents with a broader interest in EU legitimacy (Rocca, Lawall, Tsakiris et al. Reference Rocca, Lawall, Tsakiris and Cram2024; Özdemir Graneng and de Wilde Reference Özdemir, Graneng and de Wilde2025), EU campaigning on social media (Fazekas, Popa, Schmitt et al. Reference Fazekas, Popa, Schmitt, Barberá and Theocharis2021), the broader topic of engagement and Euroscepticism (De Wilde, Michailidou and Trenz, Reference De Wilde, Michailidou and Trenz2014; De Wilde, Rasch and Bossetta Reference De Wilde, Rasch and Bossetta2022), or the Europeanising potential of social media (Hänska and Bauchowitz Reference Hänska and Bauchowitz2019); such analyses routinely control for the presence of multimedia features (Bene, Magin, Jackson et al. Reference Bene, Magin, Jackson, Lilleker, Balaban, Baranowski, Haßler, Kruschinski and Russmann2022; Özdemir and Rauh Reference Özdemir and Rauh2022). Scholarship has investigated visual politics and discourse in the EU, especially with regard to symbolism and logos (Bruter 2003, Reference Bruter2009; Cram and Patrikios Reference Cram, Patrikios, Lynggaard, Manners and Löfgren2015; Popa and Dumitrescu Reference Popa and Dumitrescu2017; Casiraghi, Cusumano and Chryssogelos Reference Casiraghi, Cusumano and Chryssogelos2024). Yet, visual communication is, to our best knowledge, not a focus of EU social media research so far, and thus we do not know what visual contents may be more successful in engaging users, potentially amplifying EU communication.

We, therefore, used a mixed-methods approach to content-analyse static visual and textual EU social media communication as well as user engagement between 2015 and 2022. Comparing Facebook and Instagram, we also contribute to the evolving academic discussion on social media affordances (Evans, Pearce, Vitak et al. Reference Evans, Pearce, Vitak and Treem2017; Kakavand Reference Kakavand2024). We followed three steps: (1) we employed an inductive-deductive image-type analysis (Grittmann and Ammann Reference Grittmann, Ammann, Petersen and Schwender2011; Tarnutzer Lobinger and Lucchesi Reference Tarnutzer, Lobinger and Lucchesi2024), on a subsample of posts (n = 400). We inductively identified recurring image types, connecting these image types to broader categories in the literature. (2) We used these image types to implement a manual quantitative visual content analysis (n = 4,800). (3) Building on the results, we implemented a computational approach and analysed 46,467 posts, including more than 20,000 pictures. Eventually, we explored the influence of different (visual) content features on user engagement in a regression analysis. Our results highlight the crucial role of social media affordances in explaining engagement.

Theoretical framework

Europeanised communication in a networked public sphere

The public sphere is an intermediate communication system between citizens and political decision-makers (Castells Reference Castells2013), defined as a ‘constellation of communicative spaces in society that permit the circulation of information, ideas, debates’ (Dahlgren Reference Dahlgren2005, p. 14). Social media are increasingly factored in and explicitly focused on in conceptualisations of the public sphere (Dahlgren Reference Dahlgren2005; Bruns Reference Bruns2023; also Habermas Reference Habermas2021), emphasising the networked character emerging with the structural diversification of communication spaces. This implies easier access for more actors and also more personalised environments (Maier, Waldherr, Miltner et al. Reference Maier, Waldherr, Miltner, Jähnichen and Pfetsch2018, p. 5). The increased importance of social media also highlights the ideal nature of one unified public sphere (eg Gitlin Reference Gitlin, Curran and Liebes1998; Kruse Norris and Flinchum Reference Kruse, Norris and Flinchum2018; also Habermas Reference Habermas2006), instead promoting a pragmatic view focused on studying multiple, interconnected public spheres. Such approaches also acknowledge the increasingly fluid and interwoven nature of public and private communication that, empirically, cannot be neatly separated (Bruns Reference Bruns2023; see also Gitlin Reference Gitlin, Curran and Liebes1998; Dahlgren Reference Dahlgren2005).

While research on EU social media communication is evolving, this pragmatic view on the networked, fragmented structure of the public sphere is mirrored in EU research. The empirical reality suggests a fragmentation along national borders, based on the idea that national public spheres are vertically (top-down, eg news contents focusing on the EU and its institutions) and horizontally (eg news contents focusing on other EU member states) Europeanised (Koopmans and Erbe Reference Koopmans and Erbe2004; Kleinen-von Königslöw Reference Kleinen - von Königslöw2012). This resonates with the idea that there are many public spheres under a European roof, united by the fact that public communication revolves around the issue of European politics in the broadest sense. Such approaches have been discussed in terms of issue spaces, defined as ‘the spatial shape of any particular, empirically observable issue discourse’ (Stoltenberg Reference Stoltenberg2021, p. 8; also, Bruns Reference Bruns2023; Luoma-aho and Vos Reference Luoma-aho and Vos2010).

While theoretical models of a networked public sphere (eg Bruns Reference Bruns2023) pertain to different communication channels fragmented along language barriers, the idea of Europeanised public spheres implies that member states have their own political and media context defining national public spheres that increasingly include European content. Building on these considerations, we embed our analysis in a theoretical model of multiple, potentially overlapping, coinciding, and/or mutually influencing Europeanised public spheres: within a constellation of different member states and different intermediate communication channels. Given its underexplored nature, we limit our analysis to social media to enhance the overall discussion with regard to direct public communication by EU institutions in particular.

Understanding the dynamics of networked Europeanised public spheres and the input of EU institutions themselves is crucial for evaluating the EU’s democratic credentials. Citizens need information and debate about the EU as a basis to exert democratic control, for example, for holding elected political decision-makers accountable for the EU’s political outcomes (Habermas Reference Habermas1962). For the EU, however, these democratic credentials have been contested for long. Discussed as the democratic deficit, one of the challenges to EU legitimacy is to bring remote, that is, complex and opaque, EU politics closer to (citizens’) home (Follesdal and Hix Reference Follesdal and Hix2006): this implies a participation deficit (Michailidou Reference Michailidou2008), prominently manifested in notoriously low voter turnout in EU elections (Gattermann de Vreese, and van der Brug Reference Gattermann, de Vreese and van der Brug2021). Relatedly, the communication deficit long implied low news visibility of EU affairs in public debate (Boomgaarden, De Vreese, Schuck et al. Reference Boomgaarden, De Vreese, Schuck, Azrout, Elenbaas, Van Spanje and Vliegenthart2013): in the wake of several accumulating crises, this lack of communication has decreased and given way to increased negative reporting and Euroscepticism. While heightened visibility in public debate should generally be welcomed from a democratic theory point of view, negative public discourse and party campaigning against the EU are contributing to an erosion of the EU’s legitimacy (De Wilde Reference De Wilde2019), confronting EU leaders with a constraining public dissensus that effectively limits their discretion in moving the EU forward (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009).

Remoteness

Remoteness, one of the central challenges for the EU’s legitimacy, is often associated with difference – in the sense of remoteness or difference from dominant meanings and interpretations of the world (Membretti Dax and Machold Reference Membretti, Dax, Machold, Membretti, Dax and Krasteva2022, p. 18). Follesdal and Hix (Reference Follesdal and Hix2006, p. 536) described remoteness in their classic account of the EU’s democratic deficit as follows: ‘Psychologically, the EU is too different from the domestic democratic institutions that citizens are used to. As a result, citizens cannot understand the EU, and so will never be able to assess and regard it as a democratic system writ large, nor to identify with it’. Remoteness in the EU debate, thus, is also described in terms of difference: in cognitive terms regarding its difference from the national context and the resulting difficulty to understand what it is and does; this makes it hard to evaluate its political output and make informed decisions in EU elections, for example. It is also described in affective terms regarding the difficulty to develop a European identity (Kuhn Reference Kuhn2015). This can be rooted in a lack of opportunity to overcome these differences: a lack of first-hand experience, public debate, and regular exposure to diverse information and opinions about it, which would help with familiarising oneself with EU politics and forming an opinion about it (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1999; Boomgaarden, De Vreese, Schuck et al. Reference Boomgaarden, De Vreese, Schuck, Azrout, Elenbaas, Van Spanje and Vliegenthart2013).

Remoteness, in cognitive and affective terms, is mirrored in the second-order paradigm used to describe EU elections, implying the prevalence of the national context as a lens, yardstick, or proxy for citizens to understand and evaluate the EU (eg Anderson Reference Anderson1998; De Vries Reference De Vries2018). The same finding prevails in analyses of EU news media coverage where a national angle dominates (eg Boomgaarden, De Vreese, Schuck et al. Reference Boomgaarden, De Vreese, Schuck, Azrout, Elenbaas, Van Spanje and Vliegenthart2013). Thus, the debate overall highlights the (national) differences that still prevail amongst member states and their citizens, identifying different national contexts as EU citizens’ point of reference (Eisele and Heidenreich, Reference Eisele, Heidenreich, Nai, Grömping and Wirz2025). Communication with the aim of bridging remoteness in the EU should, therefore, be understood as communication tailored to the ultimate goal of overcoming these differences. This is to foster a political community of European citizens as the precondition for a legitimate political entity, that is, one that is built on values and beliefs that are shared within this community (Beetham Reference Beetham1991; Scharpf Reference Scharpf1999).

User engagement

Connecting back to the debate about the constraining dissensus (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009), existing studies of social media communication about the EU come to quite sobering results, highlighting the negativity of user comments (De Wilde Michailidou and Trenz Reference De Wilde, Michailidou and Trenz2014), higher user engagement with national politics (Bene, Magin, Jackson et al. Reference Bene, Magin, Jackson, Lilleker, Balaban, Baranowski, Haßler, Kruschinski and Russmann2022), and even traits of populism in user comments (Galpin and Trenz Reference Galpin and Trenz2019). Yet, in a time where people increasingly stop actively seeking news and get their information about politics curated by social media algorithms (eg Gil de Zúñiga Copeland and Bimber Reference Gil de Zúñiga, Copeland and Bimber2014), the possibility of direct communication between EU institutions and EU citizens via social media platforms has the potential of bridging remoteness. As such, social media platforms live off user attention and engagement (eg Lamot and Paulussen Reference Lamot and Paulussen2024), defined as ‘the extent to which varying functionalities like comment fields or “e-mail a friend” links were used’ (Larsson Reference Larsson2023, p. 2747). In that sense, engagement metrics offer unique opportunities for monitoring users’ interaction with and exposure to content (Ksiazek Peer and Lessard Reference Ksiazek, Peer and Lessard2016). But the dependence on engagement also makes social media users effective secondary gatekeepers of visibility (Singer Reference Singer2014), increasing pressure on the communicator to adapt to the social media logic (Lamot and Paulussen Reference Lamot and Paulussen2024).

User engagement is, therefore, an ambivalent indicator that is difficult to connect to larger concepts such as legitimacy or trust: it only shows that people clicked on something, but not why. How users interact with content on social media is highly influenced by algorithmic curation where complex machine learning models largely operate in a black box, ordering, highlighting, and suggesting content (Salgado and Bobba Reference Salgado and Bobba2019; Lamot and Paulussen Reference Lamot and Paulussen2024). Given the theoretical ambiguity, we focus on user engagement as an indicator of success in creating visibility on social media platforms. Visibility, as the basic rationale of the EU communication literature of the past decades goes (Eisele and Heidenreich Reference Eisele, Heidenreich, Nai, Grömping and Wirz2025), is a necessary condition for legitimacy as it allows familiarising and understanding as a basis for social judgements such as legitimacy (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1999). However, visibility is contingent: it does, in itself, not allow further conclusions as to its effects since this depends on what exactly becomes more or less visible.

Studies focusing on shareworthiness (Trilling Tolochko and Burscher Reference Trilling, Tolochko and Burscher2017) have looked into the feature patterns in contents that might induce user engagement. This research highlights the role of different news values present in a post in triggering engagement, such as negativity and conflict, emotions, and proximity (Trilling Tolochko and Burscher Reference Trilling, Tolochko and Burscher2017; García-Perdomo, Salaverría, Kilgo et al. Reference García-Perdomo, Salaverría, Kilgo and Harlow2018). Visual communication is found to be particularly engaging (Vraga, Bode and Troller-Renfree Reference Vraga, Bode and Troller-Renfree2016): images resemble reality and are often interpreted as directly picturing it (Graber Reference Graber1996), while allowing for subjective interpretation by different people. Visuals can help people remember information more easily and help create an emotional connection (see León Negredo and Erviti Reference León, Negredo and Erviti2022, p. 977), which again corroborates the relevance of visual communication as a potential path to bridging the EU’s remoteness from its citizens.

Cognition and affection are important for categorising user engagement: while likes, as one of the most common ways to engage with social media content, can be seen as ‘click-speech’, expressing usually a positive reaction, they might be used as recognition, or to ‘express a variety of affective responses such as excitement, agreement, compassion, understanding, but also ironic and parodist liking’ (Gerlitz and Helmond Reference Gerlitz and Helmond2013, p. 1358). In that sense, liking content is described as being affectively triggered, responding to sensory and visual features of a post (Kim and Yang Reference Kim and Yang2017). Comments require a higher level of cognitive effort and are seen as ‘speech acts that contribute to the collective interpretation and engagement’, driving a (political) discussion (Bossetta Dutceac Segesten and Trenz Reference Bossetta, Dutceac Segesten, Trenz, Barisione and Michailidou2017, p. 6). In contrast to liking, commenting is found to be cognitively triggered, induced by rational and interactive features of a post (Kim and Yang Reference Kim and Yang2017, also Marcella Baxter and Walicka Reference Marcella, Baxter and Walicka2019).

In sum, we perceive user engagement as an indicator of success in catering to user needs programmed into intransparent algorithms. User engagement metrics can generally show if EU social media communication is successful in creating visibility on social media: increased visibility increases opportunities for EU citizens to experience EU politics more directly, which is a precondition for forming opinions about its legitimacy.

Linking visual content and user engagement

The following section draws on literature explaining the mechanisms behind user engagement more generally to formulate open research questions and hypotheses regarding (1) image types used in EU social media communication and (2) user engagement. Lastly, we also investigate (3) differences across two platforms. We develop expectations as to how different visuals and the extent of textual elements influence user engagement with EU social media communication. Given the scarce research to build on, these expectations are interdisciplinarily grounded in visual communication research and the political science literature focusing on EU legitimacy.

Image types in EU social media communication

Visual political communication draws on conventionalised patterns to portray traits of politicians. Such practices are conceptualised as political image-making, which is the strategic use of ‘visual and verbal messages, that provide a shorthand cue to audiences for the identification and enhancement of specific character traits’ (Strachan and Kendall Reference Strachan, Kendall, Hills and Helmers2004, p. 135). Scholarship has conceptualised and examined such conventionalised visuals that imply specific (symbolic) meaning as image types which allows for a systematic analysis (Schill Reference Schill2012; Müller and Geise Reference Müller and Geise2015). For example, the image type of politicians shaking hands with other leaders appeals to their agency (Grittmann and Ammann Reference Grittmann, Ammann, Petersen and Schwender2011), the type of commander-in-chief visiting troops visualises their strength as leaders (Müller and Geise Reference Müller and Geise2015), the image type of family (wo)man appeals to family values (Bast Reference Bast2024), and the type of bathing in a crowd of voters or as (wo)man of the people aims at appearing relatable (Schill Reference Schill2012).

Visual political communication research has long observed a growing professionalisation of how politicians are portrayed in the media (Schill Reference Schill2012), as well as an increase in the personalisation of strategic political communication and media coverage (Bucy and Grabe Reference Bucy and Grabe2007; Coleman and Wu Reference Coleman and Wu2015). Social media perpetuates these trends (Farkas Reference Farkas2023) and, consequently, political image-making incorporates (self-)branding strategies from other actors on social media (Marwick Reference Marwick2013; Abidin Reference Abidin2016). Such strategies emphasise features anticipated to come across as relatable and authentic (Maares Banjac and Hanusch Reference Maares, Banjac and Hanusch2021), which can result in politicians portraying themselves as ‘one of the people’ (Metz Kruikemeier and Lecheler Reference Metz, Kruikemeier and Lecheler2020) or decreasing social distance in their visual communication (Liebhart and Bernhardt Reference Liebhart and Bernhardt2017; Lalancette and Raynauld Reference Lalancette and Raynauld2019).

Research examining visual political communication on social media primarily focuses on accounts of politicians instead of political institutions and finds politicians to embrace personalisation and self-branding strategies (Lalancette and Raynauld Reference Lalancette and Raynauld2019; Metz Kruikemeier and Lecheler Reference Metz, Kruikemeier and Lecheler2020). The focus is more on actors and their achievements rather than issues (Ekman and Widholm Reference Ekman and Widholm2017). Dominant image types relate to granting politicians legitimacy by picturing them on the job, for example, giving a speech, shaking hands with other politicians, and engaging in media work (Bast Reference Bast2024). The few studies investigating parties’ or governmental institutions’ social media accounts similarly find that they focus on personalising the lead candidate(s) of their party or office holders (Filimonov Russmann and Svensson Reference Filimonov, Russmann and Svensson2016; Turnbull-Dugarte Reference Turnbull-Dugarte2019). Again, social media is used to communicate image types relating to media work and give insight into the ‘behind the scenes’ of political work (Liebhart and Bernhardt Reference Liebhart and Bernhardt2017). As EU institutions are perceived as remote and out of touch with EU citizens, we first aim to understand patterns in EU visual social media communication, generally taking stock of the image types used:

RQ1: What image types can we identify in visual EU communication contents posted on Facebook and Instagram?

Exploring the influence of (visual) content features on user engagement

In the following, four theoretical categories are in focus, identified in the literature as connecting to the broader aim of community-building: the actor- and structure-centred categories of people and place as well as the affection- and cognition-centred categories of political symbolism and political communication. People and places are identified as important categories in the visual political communication literature; affection and cognition directly link back to the EU’s remoteness in terms of cognitive complexity as well as the resulting difficulty to identify with it (Follesdal and Hix Reference Follesdal and Hix2006).

People. Research indicates that social media users engage more with images that feature people (Aramendia-Muneta Olarte-Pascual and Ollo-López Reference Aramendia-Muneta, Olarte-Pascual and Ollo-López2021). Scholarship on politicians’ social media strategies shows that images featuring politicians were much more successful in garnering likes than images without people (Brands Kruikemeier and Trilling Reference Brands, Kruikemeier and Trilling2021; Farkas and Bene Reference Farkas and Bene2021; Peng Reference Peng2021). This also connects to the debate on the personalisation of EU politics (Gattermann Reference Gattermann2022), which revolves around the idea that giving Europe a human face could help reduce the remoteness of EU politics. While this research shows that personalisation is not an easy fix, it does not focus on social media platforms which follow their own logic in engaging the audience (eg Larsson Reference Larsson2023). This leads us to the following assumption:

H1: EU communication posted on Facebook and Instagram with visual contents featuring humans generates more user engagement in comparison to EU communication with visual contents not featuring humans.

The category of ‘humans’ is rather broad and undefined. Relating back to remoteness as one of the central challenges in the relationship between the EU and its citizens, we may distinguish between politicians as the representatives of the people and the people as such. ‘Humans’ might, thus, be politicians attempting to appear as relatable and hard-working representatives of the people (Liebhart and Bernhardt Reference Liebhart and Bernhardt2017; Metz Kruikemeier and Lecheler Reference Metz, Kruikemeier and Lecheler2020; Aramendia-Muneta Olarte-Pascual and Ollo-López Reference Aramendia-Muneta, Olarte-Pascual and Ollo-López2021; Farkas and Bene Reference Farkas and Bene2021; Peng Reference Peng2021; Bast Reference Bast2024), increasing engagement with such posts:

H2: EU communication posted on Facebook and Instagram with visual contents featuring politicians generates more user engagement in comparison to EU communication with visual contents not featuring politicians.

However, another strategy of engaging the audience may be to put those arguably feeling remote at the centre of communication. The latter aspect has been discussed in studies of EU media coverage focusing on the visibility of EU citizens, arguing that increased visibility of ordinary citizens in elite-produced communication, like the news, can reduce a perception of the EU as elitist and far away from EU citizens and their daily lives (Walter Reference Walter2017a, Reference Walter2017b; also De Wilde Reference De Wilde2019). While the underlying argument of this research is helpful to establish plausibility, it does not allow more concrete conclusions as to the effects of citizens featured in EU visual social media communication on user engagement. We, therefore, formulate an open research question:

RQ2: To what extent does the visual presence of citizens in EU communication on Facebook and Instagram influence user engagement?

Place. Visual communication not featuring people is a more heterogeneous category in which different aspects of the context or places surrounding people may be relevant. Following Harvey (Reference Harvey1996), places can contribute to people’s identity, experiences, and memory, depending on how they interact with each other and the material objects in it. This identity and community formation around places has also been conceptualised as placemaking, describing the practices through which material places are socially imbued with meaning (Halegoua Reference Halegoua2020, p. 5). Placemaking can also occur through mediatisation, as images can carry an ‘imagined presence across the members of a local community, although much of the time members of such a place may not be conscious of this imagined community’ (Urry Reference Urry and Blau2004, p. 14). Further, affordances of digital media can shape how we experience place and placemaking (Halegoua Reference Halegoua2020). Digital placemaking can occur bottom-up, strategically through (government) organisations, or as a mix of both (Basaraba Reference Basaraba2023).

From a communication perspective, the concept of place-naming is closely related to placemaking. It is defined as a process in which, first, ‘issues become associated with ‘places’; second, through their discursive connection to the same issue, these places are synthesised as relating to each other and belonging to the same issue ‘space’ (Stoltenberg Reference Stoltenberg2021, p. 8). Reconnecting to our understanding of the EU’s public sphere as an issue space, visual placemaking or-naming on social media, for example, sharing photographs of (representative) buildings and related stories, could, thus, contribute to community-building.

Scholarship examining digital placemaking primarily stems not only from urban, media, and tourism studies but also from political communication (Basaraba Reference Basaraba2023), for example, focusing on textual digital placemaking through hashtags during the refugee crisis (Ozduzen Korkut and Ozduzen Reference Ozduzen, Korkut and Ozduzen2021). Studies on digital visual placemaking do, however, not consider audience engagement. For lack of conclusive evidence in the literature, we resort to the following open research question:

RQ3: To what extent does the visual reference to places in EU communication on Facebook and Instagram influence user engagement?

Political Symbolism. Following Durkheim (Reference Durkheim1951), symbols can generally be seen as important signifiers of communities, increasing the self-consciousness of societies. Political symbols are perceived and also found to function as effective drivers of integration and solidarity amongst individuals tied together in a unified community (Klatch Reference Klatch1988, p. 139; Bruter Reference Bruter2009). They signal a common identity based on shared values and beliefs (eg Kariryaa, Rundé, Heuer et al. Reference Kariryaa, Rundé, Heuer, Jungherr and Schöning2022), which is the basis for political legitimacy (Beetham Reference Beetham1991). While image types are in themselves perceived as carrying symbolic meaning (Schill Reference Schill2012; Müller and Geise Reference Müller and Geise2015), the effects of more explicit European symbols, like the EU flag or the common currency, have been analysed and found to be central integration and legitimising tools of the EU (Bruter Reference Bruter2003; Cram and Patrikios Reference Cram, Patrikios, Lynggaard, Manners and Löfgren2015; Popa and Dumitrescu Reference Popa and Dumitrescu2017), fostering a European identity (Negri Nicoli and Kuhn Reference Negri, Nicoli and Kuhn2021). The role of such political symbols in political online communication is generally understudied; one finding, here, is that effects of national flags in social media communication increase engagement but are context-dependent (Kariryaa, Rundé, Heuer et al. Reference Kariryaa, Rundé, Heuer, Jungherr and Schöning2022). Given the scarce evidence, we explore the influence of political symbolism on user engagement with the following research question.

RQ4: To what extent does the visual presence of political symbols in EU communication on Facebook and Instagram influence user engagement?

Political Information. Another important aspect of remoteness is the dynamic complexity of the political system of the EU. This complexity leads to a public information deficit (Clark Reference Clark2014; Marquart, Goldberg, Van Elsas et al. Reference Marquart, Goldberg, Van Elsas, Brosius and De Vreese2019) as the EU is hard to explain to the public, even for experts. Accordingly, research has long highlighted that participation in European politics is mostly for knowledgeable and educated elites (eg Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger1999; Clark Reference Clark2014). Consuming political communication online has been positively linked to increased political participation (eg Valenzuela Reference Valenzuela2013; Gil de Zúñiga Copeland and Bimber Reference Gil de Zúñiga, Copeland and Bimber2014) and could help to alleviate the information and participation deficits at the core of the EU’s democratic deficit. However, communicating complex or abstract information is difficult using visual communication only (eg Highfield and Leaver Reference Highfield and Leaver2016). In response to this challenge, political campaigning on Instagram, for example, has been found to circumvent its ‘image-first’ rationale by integrating textual elements to increase the political content of posts (Hassler Kümpel and Keller Reference Hassler, Kümpel and Keller2023, p. 534). While our research is focused on visual EU communication as such, we follow this line of reasoning. Providing a more comprehensive picture, we take the extent of textual elements in visual communication as a proxy for additional political information that EU institutions post on social media. For lack of conclusive evidence regarding effects on user engagement, we pose an open research question:

RQ5: To what extent does the degree of textual in addition to visual contents in EU communication on Facebook and Instagram influence user engagement?

Differences across platforms

Lastly, user behaviour differs across different social media platforms due to differences in affordances, contexts, audience cohort, and audience expectations (Heft, Buehling, Zhang et al. Reference Heft, Buehling, Zhang, Schindler and Milzner2024). While social media are often viewed as one entity of communication, they follow distinct platform logics depending on their materiality and what kind of behaviour they afford (Evans, Pearce, Vitak et al. Reference Evans, Pearce, Vitak and Treem2017). Generally, Facebook and Instagram are thought of as platforms that foster citizen–politician connections rather than facilitating connections among politicians or politicians and journalists (Boulianne and Larsson Reference Boulianne and Larsson2023). Visual communication research still mostly focuses on single platforms without embracing a comparative approach despite studies indicating that the type of social media makes a difference in what images are communicated and with what effect (Farkas and Bene Reference Farkas and Bene2021).

Scholarship generally points to differences in social media affordances, as Facebook, for example, allows for hypertextuality by linking to external sources, whereas Instagram only allows to create connections to themes and people within the platform through tags and hashtags (Hase Boczek and Scharkow Reference Hase, Boczek and Scharkow2023). Facebook further provides more options for audience interactions through the possibility to share posts as well as multiple reactions (eg Eberl, Tolochko, Jost et al. Reference Eberl, Tolochko, Jost, Heidenreich and Boomgaarden2020), whereas Instagram only allows sharing posts in stories or as direct messages, making shares ephemeral and relocating follow-up discussions into private chats (Schreiber Reference Schreiber2017). Moreover, Instagram follows an inherently visual logic as posts cannot be purely text-based (Hase Boczek and Scharkow Reference Hase, Boczek and Scharkow2023); thus, visuals have to be especially succinct to attract audience attention, whereas in Facebook any visual could attract immediate attention when compared to text-only posts.

Research further points to different norms of what can and should be communicated on different social media platforms (Waterloo, Baumgartner, Peter et al. Reference Waterloo, Baumgartner, Peter and Valkenburg2018). Here, Instagram is perceived as a platform that allows for more affect and intimacy when compared to Facebook where audiences expect a more neutral communication style from politicians (Bossetta and Schmokel Reference Bossetta and Schmokel2023). Furthermore, content that showcases politicians in more private settings appears to be more popular on Instagram than on Facebook (Farkas and Bene Reference Farkas and Bene2021). Lastly, in EU countries, users of Facebook tend to be slightly older than Instagram users (Newman, Fletcher, Eddy et al. Reference Newman, Fletcher, Eddy, Robertson and Nielsen2023), who have been assumed to prefer ‘lighter’ and less formal communication styles (Larsson Reference Larsson2018). As such, Instagram audiences might be more inclined to engage with EU accounts as younger citizens tend to support the EU in some parts of Europe (Lauterbach and De Vries Reference Lauterbach, De Vries, Hobolt and Rodon2021). We do, however, not know whether visual communication strategies fare similarly for political institutions. Therefore, we ask:

RQ6: To what extent are there differences between Facebook and Instagram regarding the (a) contents featured in EU communication and (b) user engagement with these contents?

Data and methods

We analysed data from the social media platforms Facebook and Instagram as two established and popular platforms in Europe. Both sites rank among the most used social media in EU countries (European Parliament 2023) and feature static visual content prominently. The data were analysed in a multi-step approach, including (1) an inductive-deductive approach to identify a range of image types, (2) the development of a coding scheme and implementation of a quantitative manual content analysis based on that scheme, and (3) an automated visual content analysis based on the manually coded data.

Facebook and Instagram data

Relying on the EU’s official information,Footnote 1 a list of nine EU institutions and bodies was compiled with corresponding Facebook and/or Instagram accounts. All data from these accounts were gathered using the CrowdTangle API, including all posts,Footnote 2 metadata, and content of static visuals (ie images) for eight years (2015–2022). This timeframe was chosen as most of the targeted accounts started their platform activities in the mid-2010s. Additionally, the eight years cover several important political events, ranging from the 2015 refugee movements, the Brexit referendum in 2016, EU elections in 2019, and the Covid pandemic starting in 2020, to the escalation of the Russian invasion and start of the war in Ukraine in 2022, which may be mirrored in the EU’s social media communication strategies.

For maintaining comparability, we only included accounts available on both platforms in the statistical analysis; we, therefore, excluded the European Court of Auditors and the European Central Bank. We also ran all models with the two accounts included which yielded very similar results, underscoring the robustness of our findings.

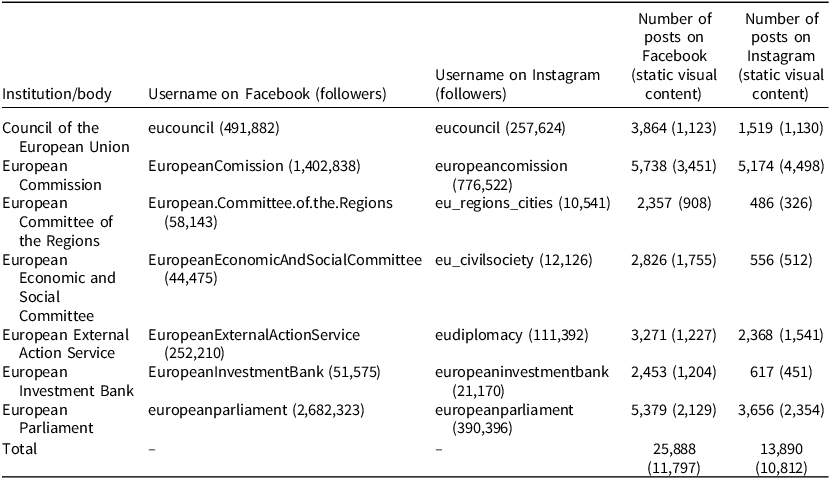

Yielding a total of n = 25,888 Facebook and n = 13,890 Instagram posts (see Table 1), we found a large share of static visuals on both platforms (with n = 11,797 posts (largest share with 45.57% of all posts) including static visual content for Facebook and n = 10,812 (largest share with 77.84% of all posts) for Instagram).

Table 1. EU institutions and bodies on Facebook and Instagram

Note: Each follower count is taken from the most recent post in the dataset (ie December 2022).

For further analyses, we used only static visuals (ie status type ‘Photo’ on Facebook and status types ‘Photo’ and ‘Album’Footnote 3 for Instagram) and different subsamples of the data. Descriptive insights into the data show that visual content involved in a post on Facebook elicits more user engagement than other communication forms. On Instagram, where every post contains some kind of visual element, static images, as compared to videos, lead to more user engagement (see online Appendix Tables A2 and A3). Moreover, omitting videos reduced the complexity of our already quite complex analysis.

A multi-step approach to coding image types

The central independent variable for our study is the image type. To uncover different types used, we employed a three-fold analysis: (1) an inductive-deductive qualitative analysis to identify distinct image types in EU social media communication and (2) a manual quantitative content analysis to quantify image types and create a foundation for the training and validation for (3) the automated visual content analysis.

(1) Identifying image types

In the first step, three researchers inductively extracted the image types for our study, based on a stratified sample of 400 pictures. The sample was stratified by account and publication year to avoid systematic biases. Each researcher examined the subsample with the aim to find patterns (Grittmann and Ammann Reference Grittmann, Ammann, Petersen and Schwender2011). We then discussed these patterns and through this discussion looked for bundles of visual ‘motifs of similar content or meaning’ (Brantner Lobinger and Stehling Reference Brantner, Lobinger and Stehling2020, p. 680). This bundling process, that is, after the inductive identification of image types, was informed by the relevant literature to ensure a thorough theoretical grounding eschewing a reinvention of the wheel. This led to 24 identified image types.

These image types relate to the political work of the EU, EU symbols, citizens of the EU, and representations of the land, culture, and technology of the EU, as well as more abstract image types capturing infographics and pictograms (see Table A4 in the online Appendix for further details). Furthermore, we noticed an image type relating to the communication of measures against the COVID-19 pandemic. We considered this as a single case study as it specifically appealed to the central interest of our study, namely citizens’ engagement by, for example, explaining mitigation measures, underlining the importance of cooperation by the public in this unique crisis. Other potential case studies were far less citizen-oriented, such as Brexit or the war in Ukraine, which focused more on political negotiations.

(2) Manual quantification

We conducted a manual quantitative content analysis on a sample of 4,800 images, annotated in an iterative process. This analysis generated first insights of the distribution of image types in the data and a better understanding of different image types’ manifestations. Importantly, we used the manually annotated data to implement and validate the automated approach.

Coding. For the quantitative manual coding, we used the information obtained in the qualitative assessment to formulate extensive coding instructions for the 24 image types (see Figure 1). Containing descriptions of the respective image types as well as individual example cases, the codebook was subject to constant development during multiple rounds of coder training, test codings, and feedback loops involving two independent coders as well as the three authors of this manuscript. Upon completion of the codebook development phase, a fresh sample of 4,800 cases was manually annotated by the two coders, exhibiting a satisfactory level of consensus with an average Krippendorff’s alpha ranging from 0.71 to 0.95 (for more details, see online Appendix Table A1).

Figure 1. Frequencies of image types in the manually coded samples by platform.

Notes: N = 4,800.

As displayed in Figure 1 (see Results section), we find that many of the image types we found in the qualitative assessment are not as relevant as they were not coded very often. The 10 most often coded image types were Pictograms, Ordinary Citizens, Behind the Scenes, Buildings, Professional Citizens, Flags, in Session, Nature, Collage, and Infrastructure.

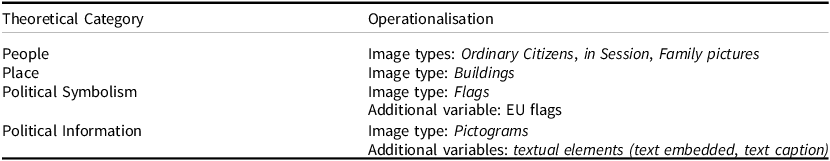

Image Type Selection for Automated Content Analysis. For implementing our machine learning approach, we needed to make sure that image types could be used to test hypotheses and explore research questions in all four categories of people, place, political symbolism, and political information. However, not all image types could be selected (1) either because they did not occur often enough, thus not providing sufficient data for learning, or (2) because the categories as clusters of images were not coherent enough, impeding a valid implementation of a machine learning approach. Based on this rationale, that is, theoretical coverage, sufficient amount of data, and increased homogeneity of clusters, we selected the following image types for the upscaled analysis of the whole corpus: Pictograms, Ordinary Citizens, Buildings, EU fags, Flags, in Session, and Family Pictures (see Table 2 for the assignment of each image type to the four categories of hypotheses and research questions).

Table 2. Operationalisation of different categories of independent variables included in the statistical analysis

Pictograms are generally understood as picture-writing, next to sound-writing (eg using the Latin alphabet), one of the two writing systems created by humans (Kolers Reference Kolers1969). We assigned this image type to the category of political information, thus perceiving it as a form of text embedded in an image. Pictograms are ‘signs that allow us to recognise in them the representation of a real object, scene, figure or animal’ (Stötzner Reference Stötzner2003, p. 296) and are thus informational; in the context of EU social media communication, it is plausible to perceive this information as political.

(3) Automated visual content analysis

To classify the visual content of the entire dataset of 22,609 pictures, we drew on automated visual content analysis. Using supervised machine learning to annotate image types on the level of the entire picture, the hand-coded material of the previous step was used to inform a model, enabling it to predict a class for each image it is shown.

Following recent methodological developments, we relied on a deep learning approach shown to outperform more basic methods (Joo and Steinert-Threlkeld Reference Joo and Steinert-Threlkeld2022). We used transfer learning (Kroon, Welbers, Trilling et al. Reference Kroon, Welbers, Trilling and van Atteveldt2024) to avoid having to provide large amounts of manually coded data: this approach harnesses the power of models pretrained on large corpora to learn about the general occurrence and distribution of visual features. Transferring this general knowledge to a specific problem, researchers can fine-tune models by adding layers trained with their manually coded data. Combining the information learned from a vast amount of images seen in the first training stage with the pictures containing target classes, the classifiers can then infer important features for the decision-making (Peng and Lu Reference Peng, Lu, Lilleker and Veneti2023). We utilised the vision transformer model ‘vit-base-patch16–224’Footnote 4 developed at Google (Dosovitskiy, Beyer, Kolesnikov et al. Reference Dosovitskiy, Beyer, Kolesnikov, Weissenborn, Zhai, Unterthiner, Dehghani, Minderer, Heigold, Gelly, Uszkoreit and Houlsby2021), trained on 14 million images from the ImageNet21k dataset (Ridnik, Ben-Baruch, Noy et al. Reference Ridnik, Ben-Baruch, Noy and Zelnik-Manor2021). Implemented through the transformers Python library (Wolf, Debut, Sanh et al. Reference Wolf, Debut, Sanh, Chaumond, Delangue, Moi, Cistac, Rault, Louf, Funtowicz, Davison, Shleifer, von Platen, Ma, Jernite, Plu, Xu, Le Scao, Gugger, Rush, Liu and Schlangen2020), a multi-class model was fine-tuned using the manually annotated data, adding a linear layer to the existing model.

Splitting the available ground-truth data into train and test data, we were able to fine-tune and validate the approach with the training set being used for the transfer learning and the test set as a holdout sample to assess whether the classifier can correctly predict the target class for unseen data. This procedure yielded excellent performance measures with an average F1 score of 0.87 with values for the individual classes ranging from 0.77 for the image-type Family Pictures to 0.93 for the image-type Buildings (see Table A5 for an overview of performance measures for individual image types).

EU flags

Similarly to the image types, a classifier to identify the presence of an EU flag was constructed using the manually annotated data and a transfer learning approach involving an instance of the ‘vit-base-patch16-224’ (Dosovitskiy, Beyer, Kolesnikov et al. Reference Dosovitskiy, Beyer, Kolesnikov, Weissenborn, Zhai, Unterthiner, Dehghani, Minderer, Heigold, Gelly, Uszkoreit and Houlsby2021) model. Opposed to the image-type flags, representing an archetype of pictures displaying flags (irrespective of what specific flag is shown), this variable was not coded on the image-type level and is thus not exclusive to the image type Flag. In other words, a picture in our sample can be classified as the image-type buildings but, if it shows an EU flag, this variable would still indicate the presence of the EU flag, although the image-type Flags is not coded as it is not the main theme of the picture

As for the classifier for the image types, the model for EU flags yielded great performance scores with an F1 score of 0.87.

Textual elements

For coding the extent of textual elements in EU social media communication, we calculated two variables. First, we consider the text displayed on the images giving additional information to the captions of a social media posting as text embedded. Second, we incorporate the caption accompanying a picture using the text caption.

Text embedded

We calculated a variable accounting for text embedded, meaning textual structures added to a picture in an editing (or creation; ie for pictograms) process. For this variable, we first constructed a classifier to identify the presence of text embedded, again, using transfer learning. Building on the manually annotated data for this variable (Krippendorff’s alpha = 0.88 see online Appendix Table A1) and the ‘vit-base-patch16-224’ (Dosovitskiy, Beyer, Kolesnikov et al. Reference Dosovitskiy, Beyer, Kolesnikov, Weissenborn, Zhai, Unterthiner, Dehghani, Minderer, Heigold, Gelly, Uszkoreit and Houlsby2021) model, a binary classifier was constructed (F1 = 0.96, see online Appendix Table A5), indicating the presence of embedded text. Second, we chose an OCR (Optical Character Recognition) engine (eg Salamanca, Brandenberger, Gasser et al. Reference Salamanca, Brandenberger, Gasser, Schlosser, Balode, Jung, Perez-Cruz and Schweitzer2024) to determine the length of the text. Implemented through the Python wrapper pytesseract, the open-source OCR engine tesseract processes an image by recognising patterns resembling letters. We extracted the embedded text and included the word count.

Text caption

We accounted for the length of an accompanying caption, operationalised as character count.

User engagement

For our dependent variable user engagement, we used the available interaction metrics. To maintain comparability while varying the cognitive effort needed for interacting (eg Matthes Knoll and von Sikorski Reference Matthes, Knoll and von Sikorski2018), we only used likes and comments: while Facebook users can choose from a variety of reactions (ie like, love, wow, haha, sad, and angry) and can comment on or share posts, Instagram only offers liking or commentingFootnote 5 . Likes and comments were included in the analysis as the number of likes and the number of comments each post received.

Control variables

Four control variables were included to account for possible confounders in the regression analysis.

Issues

To control for the role of different contexts in which EU institutions might communicate and incorporate the text posted alongside the pictures on both platforms, we coded the issue of the caption. To this end, we used the manifestoberta model based on XLM-RoBERTa large models which were then fine-tuned using the roughly 1.5 million manually coded statements of the Manifesto Corpus (Burst, Lehmann, Franzmann et al. Reference Burst, Lehmann, Franzmann, Al-Gaddooa, Ivanusch, Regel, Riethmüller, Weßels and Zehnter2023). Issues, according to the Manifesto Project coding scheme, include 56 issues at the top level, which we boiled down to 7 top-level domains, as described in the manifesto codebook (Volkens, Krause, Lehmann et al. Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Matthiess, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2021). These domains include Economy, External Relations, Fabric of Society, Freedom and Democracy, Political System, Social Groups, and Welfare and Quality of Life (see Volkens, Krause, Lehmann et al. 2020 for detailed explanations of these categories). We incorporated domains instead of the more detailed issues to control for a rough thematic direction of a post and how it might influence user engagement. Moreover, using all 48 issues as factors would have over-complicated the statistical models (see below), making it impossible to validly estimate the effects of all variables.

Sentiment

We incorporated the tonality of the caption operationalised as sentiment, using the Lexicoder dictionary by Young and Soroka (Reference Young and Soroka2012). It encompasses 4,567 valenced keywords (2,858 for negative and 1,709 for positive) and is shown to work well for political communication and social media texts. Following the authors’ recommendations, multiple steps of preprocessing of the text were applied (eg removing punctuation and special characters). Final sentiment scores for each caption were calculated using the R package quanteda (Benoit, Watanabe, Wang et al. Reference Benoit, Watanabe, Wang, Nulty, Obeng, Müller and Matsuo2018). Comparing the words in the individual captions with the keywords from the dictionary, we calculated the sum of all words indicating positive sentiment minus the sum of all scores from negative words. Lastly, we divided this score by the number of words to account for the length of the caption.

Over time dynamics

We incorporated further control variables taking into account whether the post was made during the election period in 2019 (ie within the six weeks before the EU election on May 26) and the year it was published.

Analysis strategy

As indicated above, we assumed that the cognitive as well as technical mechanisms would interact (ie like or comment) with content work differently on platforms. Therefore, we decided to analyse platforms separately, calculating four models to assess the influence of image types, the inclusion of textual elements, and the control variables on the number of likes and comments, respectively.

Inspecting the dependent count variables (see online Appendix Figure A1), we decided for a negative binomial regression given the overdispersed Poisson distribution. The models were estimated through the Stan probabilistic programming language (Carpenter, Gelman, Hoffman et al. Reference Carpenter, Gelman, Hoffman, Lee, Goodrich, Betancourt, Brubaker, Guo, Li and Riddell2017) and the R package brms (Bürkner Reference Bürkner2017), using Bayesian methods. To account for potential unobserved heterogeneity across sources, we clustered standard errors at the account level (ie random effects). Variation is adjusted at the level of the individual account, and differences, such as potentially higher engagement due to varying audience dynamics or follower numbers, are absorbed by the account-level clustering. For better interpretability of resulting coefficients, all independent variables and controls that were not initially dichotomous were rescaled to range from 0 to 1. All four models converged with Gelman–Rubin convergence not exceeding 1 (Gelman and Rubin Reference Gelman and Rubin1992).

Results

We were first interested in the image types generally included in EU social media communication (RQ1, see Figure 1). According to our manual content analysis, the most frequently found images are Pictograms, meaning visual content that shows stylised abstractions of people, landscapes, or symbols, generally understood as picture-writing (Kolers Reference Kolers1969; Stötzner Reference Stötzner2003). Out of the seven most frequent image types, three relate to persons, namely Ordinary and Professional Citizens as well as politicians shown during parliamentary sessions (in Session). Images frequently convey Behind the Scenes impressions, showing, for example, preparations for press conferences or insights that are usually not meant for the public. Many pictures show Buildings and Flags as main content; only few images relate to the Covid pandemic (Case Study (Covid)) or focus on passports (see Figure 1).

Focusing only on the image types included in the automated analysis, we find differences across the two platforms. On Facebook, Pictograms are the most prominent of the six image types measured (14.49%); Instagram focuses mostly on Ordinary Citizens (11.64% as opposed to 8.86% showing Pictograms) which is also a prominent category on Facebook (9.48%). Posts rarely depict politicians in a more formal setting defined as Family Pictures (2.13% on Facebook; 2.91% on Instagram).

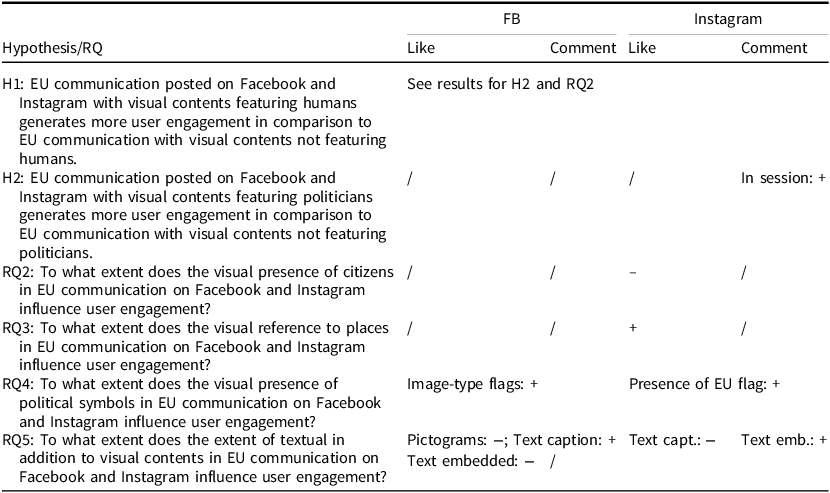

Turning to effects on user engagement, we find that likes and comments on Facebook and Instagram vary across posts containing different image types (for a descriptive overview, see online Appendix Tables A6–A9). We find mixed evidence regarding whether images depicting humans increase user engagement (H1). While on Instagram, politicians in Session increases comments (β = 0.3 or 35% increaseFootnote 6 ), and other types showing people do not have the same effect (see Figures 2 and 3 and online Appendix Tables A10–A13). On the contrary, we find that the depiction of Ordinary Citizens decreases likes on Instagram. The results provide support for H2, which states that showing politicians elicits more user engagement; they also tackle RQ2 in that the presence of Ordinary Citizens in a social media post does not positively influence user engagement but rather slightly decreases it.

Figure 2. Estimated posterior fixed-effects parameters for likes on Facebook (left) and Instagram (right).

Notes: Means of posterior samples are represented as dots. Thin lines represent 95% credible intervals. n = 11,552 for Facebook (left) and n = 10,797 for Instagram (right). Reference group for Image Types is the category ‘Other’; for Years it is 2015; and for Topics it is ‘External Relations’.

Figure 3. Estimated posterior fixed-effects parameters for comments on Facebook (left) and Instagram (right).

Notes: Means of posterior samples are represented as dots. Thin lines represent 95% credible intervals. n = 11,552 for Facebook (left) and n = 10,797 for Instagram (right). Reference group for Image Types is the category ‘Other’; for Years it is 2015; and for Topics it is ‘External Relations’.

Buildings, the most prominent image type on Instagram, has a positive effect on likes but not comments. For Facebook, we find no effect of this image type, suggesting that the visual presence of places does not spark user engagement (RQ3).

Turning to RQ4, Flags are the strongest positive predictor of likes and comments on both platforms, although politicians in Session elicit slightly more comments on Instagram. Flags as political symbols, therefore, are found to be the strongest predictor of user engagement. Examining the effect of an EU flag shown (be it within the image-type Flags or not), the results showed no effect for comments on Facebook. On Instagram, in turn, we find a positive effect with a slightly increased number of likes (β = 0.16; 17% increase) and comments (β = 0.28; 32% increase), similarly to likes on Facebook (β = 0.06; 6% increase).

Turning to RQ5, we were interested in the effects of additional political information, indicated by the presence of textual elements. The most common image type on Facebook, Pictograms, has a slight negative impact on the number of comments on the platform, with no effects on likes on Facebook and Instagram, but a slight positive effect on comments on Instagram. We also found very mixed results across the two platforms for both text embedded and text caption: first, the longer a text embedded in an image is, the less people are likely to like the post on Facebook, with no effect for comments on the platform. In turn, people appear to appreciate longer additional textual information embedded in pictures on Instagram, making them more likely to receive comments, but not likes. Considering the caption text, the effect is almost reversed for the two platforms. Here, a longer caption distinctly boosts likes and comments on Facebook. On Instagram, a longer caption text decreases the number of likes with no effect on comments. Table 3 provides an overview of hypotheses and research questions and corresponding results.

Table 3. Overview of effects on user engagement by platform and engagement type

Regarding our control variables, we found that more positive sentiment decreases the number of comments. Considering the topic addressed in the caption, it is mostly Fabric of Society that sparks engagement on both platforms (although Political System is the strongest predictor among caption topics for comments on Instagram), whereas topics like Economy or Social Groups decrease engagement across both platforms and engagement types. While being posted during the election period did not make a difference, we found a strong impact of the different years under investigation, especially for Instagram. Here, user engagement was distinctly higher in the year 2018 and later, as compared to 2015, indicating an increase in engagement over time that stagnates around 2018 or 2019. This reflects the general development and popularity of Instagram (Weston Reference Weston2023).

Discussion and conclusion

Our study explored the image types used in visual EU social media communication and the engagement they trigger on Facebook and Instagram as two of the most popular social media platforms today. Focusing on the EU’s democratic deficit, manifested in its participation and communication deficits, we argued that the creation of visibility is a necessary condition for enabling a direct experience of EU politics, potentially leading to greater familiarity and, in turn, reduced remoteness. Social media communication, especially visual communication, was identified as having great potential in this respect, while still remaining under-researched in the academic EU debate.

Regarding the image types used in EU social media communication, results reveal that Pictograms were the most prominent image type. Pictograms in general have been found to be an effective way of communication across languages and cultures (eg Clawson, Leafman, Nehrenz et al. Reference Clawson, Leafman, Nehrenz and Kimmer2012; Barros, Alcântara, Mesquita et al. Reference Barros, Alcântara, Mesquita, Santos, Paixão and Lyra2014). This result could be read as the EU institutions’ strategy to effectively speak to all EU citizens with the same contents, aiming to unify a linguistically diverse audience. In addition, the prominent image types that we identified can, based on the relevant literature, be read as an attempt to motivate users to engage by, for example, featuring citizens themselves (Ordinary and Professional Citizens), making EU politicians more relatable by showing their behind-the-scenes and active work (Behind the Scenes and in Session), Buildings and Nature as connections to places, and Flags symbolising the unity and diversity of the EU as a political community.

Regarding the effects of posted content on user engagement, our results paint, at first sight, a rather mixed picture but can be interpreted as an expression of underlying structural differences across the platforms. Featuring humans works, but to a limited degree: the visual presence of politicians increases engagement, but the way they are featured matters. Instagram users react more to less arranged pictures of politicians in Session, engaged in their daily work. This finding speaks to Instagram’s general logic of showcasing more personal images and supports research comparing politicians’ visual communication on Facebook and Instagram, which indicated that Instagram users approve more of ostensibly authentic and more private content (Farkas and Bene Reference Farkas and Bene2021; Bossetta and Schmokel Reference Bossetta and Schmokel2023).

The presence of citizens on pictures seems to, at least slightly, decrease users’ likes on Instagram. This is a surprising finding given that people are often linked to higher engagement in the literature focusing on visual communication on social media (Bakhshi Shamma and Gilbert Reference Bakhshi, Shamma and Gilbert2014; Peng Reference Peng2021) and also topics like citizen initiatives are found to yield more engagement for EU social media communication (Rocca, Lawall, Tsakiris et al. Reference Rocca, Lawall, Tsakiris and Cram2024). While actual effects of EU communication featuring citizens were not in focus of the relevant EU literature (eg Walter Reference Walter2017a, Reference Walter2017b), it is motivated by the underlying assumption that the presence of citizens in elite communication could help to bridge remoteness between the EU and its citizens. However, EU social media communication featuring humans could also be interpreted as an attempt to only appear relatable which may not be perceived as credible or authentic. Results on politicians’ visual communication indicated similar mixed findings (Farkas and Bene Reference Farkas and Bene2021). These results merit further investigation to draw more substantial conclusions.

Similar to the depiction of politicians and EU officials, users react to political symbolism, but to different representations of it: the image-type Flags, that is, an image in which flags are in focus, elicits user engagement on Facebook. On Instagram, where users are generally younger than on Facebook, they engage with images featuring the EU flag. Flags as such are connected to the societal symbol function of visuals which are often used to tap the emotional power associated with them (Schill Reference Schill2012). (National) flags are usually understood as a symbol for a political community, strongly influenced by historical developments, and often associated with positive emotions (Becker, Butz, Sibley et al. Reference Becker, Butz, Sibley, Barlow, Bitacola, Christ, Khan, Leong, Pehrson, Srinivasan, Sulz, Tausch, Urbanska and Wright2017). The EU’s coherence as a community is, however, contested; nationalist tendencies are apparent all across the union, manifested in the rise of radical right and left parties, united in their anti-EU stance (eg Brack Reference Brack2020). A more fine-grained analysis of the effect of individual flags should be conducted to better understand these results.

The visually anchored nature of communication on Instagram shows stronger results regarding the effects of (different features of) images in comparison to Facebook. Visual references to places increase likes on Instagram but have no effect on comments; they are also insignificant for interaction on Facebook in general. Additional text can help to engage users on Instagram if it is embedded in the visual, which further informs the literature on Instagram and political campaigning (eg Hassler Kümpel and Keller Reference Hassler, Kümpel and Keller2023). Our analysis of Facebook, in contrast, shows stronger results for text-related variables, in line with the platform’s affordances and logics. A visual anchoring seems generally less successful than on Instagram as text embedded in the image, and also Pictograms as an image type decrease interaction with the post. In contrast, additional text outside visual components, such as a caption, makes users engage on Facebook.

These findings emphasise the different ways users consume EU communication on different platforms: when coming across a new post, Facebook users might read the text first and engage with it, whereas on Instagram, the visual logic presents the image first and requires audiences to click to expand the caption. Likes on Instagram can therefore be expected to be more closely linked to the visual than the caption text. This might also be indicated in the finding that images with embedded text received slightly more comments on Instagram, which could be interpreted as an immediate textual response to text visible in the timeline (in contrast to a haptic like). Future research should disentangle this relationship further.

Overall, our results emphasise the crucial moderating function of social media affordances, dynamically ‘emerging from the relationship between the user, the object, and its features’ (Evans, Pearce, Vitak et al. Reference Evans, Pearce, Vitak and Treem2017, p. 40). It is, thus, crucial to keep the specific users in mind when devising a communication strategy that aims at stimulating the whole range of user behaviour invited on specific platforms for successfully creating visibility. This highlights the fact that EU communication, like any other communication on social media, is subject to the commercial logics created by for-profit organisations, shaping the dynamics of public political debate in unparalleled ways (eg Zuboff Reference Zuboff2015). These dynamics are already ingrained in the broader process of mediatisation, implying an increased adaptation to the media logic (Strömbäck Reference Strömbäck2008), and become more visible with the rise of social media: The relevant platforms offer great potential for creating opportunities for EU experience, given their increased outreach and importance in public debate. But they also force a commercial audience logic of popularity on any communication (eg Singer Reference Singer2014; Lamot and Paulussen Reference Lamot and Paulussen2024), also of public institutions communicating for transparency rather than profit.

While our study is, to our best knowledge, the first to undertake a systematic evaluation of EU visual social media communication of different platforms, it comes with several limitations. First of all, only two platforms were included in our analysis. The strong differences we found across these two platforms warrant a more explicit focus on the consequences of different affordances of platforms. To complement already existing research engaging in large-scale comparisons of social media affordances (Peng Reference Peng2021; Bossetta and Schmokel Reference Bossetta and Schmokel2023), scholars should invest in including more platforms to further substantiate results for this crucial public communication space.

In addition, working with image types implies that many aspects of a visual representation remain unaccounted for. Using only one classification per image means missing out on many more details which could explain user engagement. Future studies should also consider videos, given their increasing importance, especially on Facebook, but also TikTok, for example. Also the fact that an image might be (labelled as) AI-generated is an interesting additional variable to consider.

Moreover, the theoretical ambiguity of social media engagement could be alleviated by considering user comments. While we took the sentiment and topic of captions into account, we did not include an analysis of comment contents to keep a clear focus on EU visual communication and how successful it is in creating visibility. We do, therefore, not know whether user comments were accepting or critical of the EU’s communication. In addition, the longevity of effects of social media communication is an important aspect when thinking about legitimacy as a rather slow-moving and inert phenomenon. Leveraging methodologies such as diary and experience sampling methods or panel experimental surveys could help to create insights in this respect.

Lastly, while results suggest that EU communication fares similarly as other political communication on social media, the EU as a case study is still fairly specific. Our results inform the specific debate about EU social media communication, but they might not be generalisable to other political organisations with a different setup and context. Future research should invest in comparing cases to better evaluate the consequences that social media affordances might have for differently structured political entities.

Regardless, our study provides rich empirical findings, via a large-scale exploration of different image types in the social media communication of EU institutions and user engagement. Regarding the potential to create visibility and thereby opportunities for experiencing EU politics, the patterns found in visual EU social media communication broadly align with the literature on what makes social media posts more or less engaging, even if not all strategies seem successful. Engagement patterns show the strategic importance of tailoring communication to the affordances and audiences of different platforms which is a crucial point for practitioners developing EU social media campaigns. It is also an important step in developing the scholarly debate on EU communication in the digital age.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1475676526100668

Data availability statement

The data and code needed to reproduce all analyses in this study are available on the Open Science OSF.io under the following link: osf.io/6zvp5.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Duoduo Hua and Ting Zhang for their diligent and reliable support with the visual content analysis. The authors would furthermore like to thank the participants of the panel ‘Political Communication in the Digital Age’ at the ECPR’s 2024 Standing Group of the European Union’s Biennial Conference in Lisbon as well as the participants of the colloquium of the Research Department Global Governance at the Berlin Social Science Centre for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics statement

This study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Department of Communication at the University of Amsterdam prior to data collection.