Introduction

Central line utilization continues to rise in tandem with an increasingly complex healthcare landscape. They are life-sustaining in patients requiring hemodialysis, intravenous medications, and parenteral nutrition. Reference Rajandra, Yunos and Teo1 Although crucial for delivery of care in acute and chronic settings, central lines increase risk of healthcare-associated infections (HAI).

Central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) are a major concern globally as they are associated with severe complications, prolonged hospitalization, increased mortality, and healthcare cost. Reference Al-Khawaja, Saeed, Al-khawaja, Azzam and Al-Biltagi2 CLABSI rates differ between healthcare institutions due to variations in patient characteristics, surveillance definitions, prevention protocols, adherence to infection prevention measures, staff-to-patient ratio, and range of medical services provided. Reference Al-Khawaja, Saeed, Al-khawaja, Azzam and Al-Biltagi2 International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) reported a pooled CLABSI rate of 5.05 per 1,000 central line-days between January 2012 to December 2017, using data from medical-surgical intensive care units (ICUs) in 45 countries in Latin America, Europe, Eastern Mediterranean, Southeast Asia, and Western Pacific. Reference Rosenthal, Bat-Erdene and Gupta3 A multicenter study involving ICUs in three Malaysian hospitals revealed a CLABSI incidence rate (IR) of 4.16 per 1,000 central line-days. Reference Rajandra, Yunos and Teo1 A 2012 meta-analysis estimated the annual cost of CLABSI at USD45,814 per-case. Reference Zimlichman, Henderson and Tamir4 The United States (US) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers CLABSI as a largely preventable HAI. 5 and recommends implementation of comprehensive prevention bundles to reduce its incidence. Reference O’Grady, Alexander and Burns6

Establishing robust surveillance methods is essential for estimating baseline CLABSI incidence, identifying associated risk factors and guiding infection prevention strategies. Reference Cai, Venkatachalam and Tee7 Locally, device-associated and post-operative HAIs in ICUs are reportable to the Ministry of Health, Singapore, 8 however information on hospital-wide central line utilization, CLABSI incidence, risk factors and causative pathogens remains limited due to a small number of epidemiological and cost-analysis publications in the region. Reference Ling, Apisarnthanarak and Madriaga9

This study focusses on hospital-attributable CLABSIs (HA-CLABSI) involving all inpatients. Existing literature on HA-CLABSI largely focusses on ICUs and immunocompromised patients due to high central lines utilization and infection risks in these groups. Nevertheless, CLABSI can also occur in other settings underpinning the heterogeneity of the population for which data is lacking. For instance, the INICC reports CLABSI rates primarily from ICUs, Reference Rosenthal, Bat-Erdene and Gupta3 potentially underestimating the burden in non-ICU settings. However, with advances in medical care, and rise in aging population with chronic conditions of varying acuity, several studies have reported an increase in central line utilization and CLABSI incidence in non-ICU settings. Reference Alwazzeh, Alnimr and Al Nassri10–Reference Climo, Diekema and Warren13 As more patients transition to community care following discharge with central lines, HA-CLABSI remains an important surveillance measure that can guide interventions in hospitals.

This study aimed to determine hospital-wide HA-CLABSI incidence and risk factors at a large tertiary hospital in Singapore. By including all inpatient areas (ICUs and general wards), this study offers a comprehensive understanding of HA-CLABSI epidemiology and supports implementation of targeted infection prevention strategies.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted in Singapore General Hospital (SGH), a 1,939 bedded tertiary acute-care hospital with 63 ICU beds, active burns, hematology, oncology and solid organ transplant services, and national cardiothoracic and cancer care centers within its premises.

Study design

This was a single-center, retrospective case-control study, nested within a cohort of adult patients aged ≥18 years and had ≥1 central lines inserted for at least 48hours from admission date. The study included data from January 2018 to December 2020. Nested case-control studies employs the case-control methodology within a well-defined cohort (here, all patients with central lines inserted), wherein cases and controls are matched at the time of event. This design is suitable when time of exposure is of importance. Reference Partlett, Hall, Leaf, Juszczak and Linsell14 The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic significantly impacted hospital operations and infection prevention practices. Reference Wee, Sim and Conceicao15 Therefore, compliance with best practices may have been affected due to competing clinical and operation priorities, thereby influencing central lines care and consequently increasing HA-CLABSI risk. Reference Satta, Rawson and Moore16 Temporal matching for central line insertion date was important to mitigate the potential confounding effects of pandemic related infection prevention changes, and to ensure that cases and controls were exposed to similar risk environment and infection prevention practices.

HA-CLABSI Definition

CLABSI was determined based on the US National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) guidelines. 17 A patient was considered to have CLABSI, if they had a central line inserted and met one of the following criteria— (i) a positive blood culture with a recognized bacterial or fungal pathogen not considered as common commensal by the NHSN; (ii) same NHSN-defined common commensal identified from a blood culture with two or more blood specimens drawn on separate occasions, in the presence of at least one of the following symptoms— fever (≥38 °C), chills, or hypotension; (iii) organisms identified in the blood culture were not attributable to infection at another body site. 17 HA-CLABSI was defined as CLABSI event occurring on or after 3rd calendar day of hospital admission.

Patients

All adult inpatients who met the NHSN criteria for HA-CLABSI during the study period were included as cases. Controls were selected from a pool of inpatients with at least one central line inserted but did not develop CLABSI throughout their hospitalization or end of study period, whichever occurred first. Cases and controls were matched on a 1:2 ratio based on insertion date, wherein controls with central lines inserted ±30days of their corresponding case’s insertion date were included. If multiple controls met the matching criteria, the two with central line insertion dates closest to that of the corresponding case were selected.

Data collection

Demographic, clinical, and central line-related variables were selected based on existing literature and biological plausibility. Data was collected through review of electronic medical records. Clinical data collection was anchored on a pre-defined at-risk window. At-risk period for cases was defined from central line insertion date to positive blood culture date (i.e., HA-CLABSI diagnosis date). For controls, at-risk period extended from central line insertion date to the corresponding case’s HA-CLABSI date or control’s discharge date or study period end, whichever occurred first (referred to as censoring date for controls).

Demographic variables included age at admission, and sex. Clinical variables included mobility status, basal metabolic index, underlying comorbidities, neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count < 1,500 cells/mm3), transfer to high-risk areas (ICU, intermediate care area [ICA] and high-dependency [HD] units) spanning up to 14 days prior to start of at-risk period, acquisition of multidrug-resistant organisms (MDRO) in the same admission prior to central line insertion, and prior bloodstream infection within four weeks preceding central line insertion. Indications for central line insertion included chemotherapy, hemodialysis, total parenteral nutrition (TPN), prior surgery, and administration of antibiotics and immunosuppressants. Patients were classified as having dependent mobility status if admission nursing documentation described them as “wheelchair-bound,” “bed-bound,” or “requiring assistance with mobility.” Patients with end-stage renal failure requiring hemodialysis, history of organ transplant, hematologic malignancy, or administration of chemotherapy or immunosuppressants during at-risk period were considered immunocompromised. Underlying comorbidities were identified using the International Classification of Diseases– Tenth Revision, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM) diagnostic codes. Central line-related variables included type of central line (central venous catheter [CVC], peripherally inserted central catheter [PICC], port-a-cath, vascular catheter), number of lumens and insertion site (brachial, jugular, subclavian, femoral, basilic). MDROs included methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE). Inpatient mortality was defined as death occurring in the same hospitalization episode, after HA-CLABSI diagnosis for cases and after censor date for controls.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in R version 4.0.1. Reference Core Team18 Categorical data were summarized as counts and percentages. Continuous variables were evaluated for normality using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and histograms and presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). Comorbidities with biological plausibility of association with HA-CLABSI and sufficient sample size were included in bivariate analysis. Conditional logistic regression was used for bivariate analysis between outcome (case-control status) and individual variables. Unadjusted odds ratios (OR) with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p-values were recorded. Variables with biological plausibility and p-values < 0.05 in the bivariate analysis were included in the multivariable regression. Collinearity of these variables was assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Backward stepwise multivariable conditional logistic regression was performed to identify independent risk factors for HA-CLABSI and their corresponding adjusted ORs (aOR), 95% CI and p-values were noted. Variables with p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. At each step of multivariable regression, variables were removed based on their highest p-value. Model fit was assessed using Akaike Information Criterion and Nagelkerke R 2. HA-CLABSI IR was expressed per 1,000 central line-days.

Ethics

A waiver of consent was obtained from the SingHealth Centralized Institutional Review Board (CIRB Ref: 2020/2799) as this study was performed as part of infection prevention efforts in the hospital.

Results

127 HA-CLABSI cases and 252 controls were included in the study. HA-CLABSI IR between January 2018 to December 2020 was 8.4 per 1,000 central line-days.

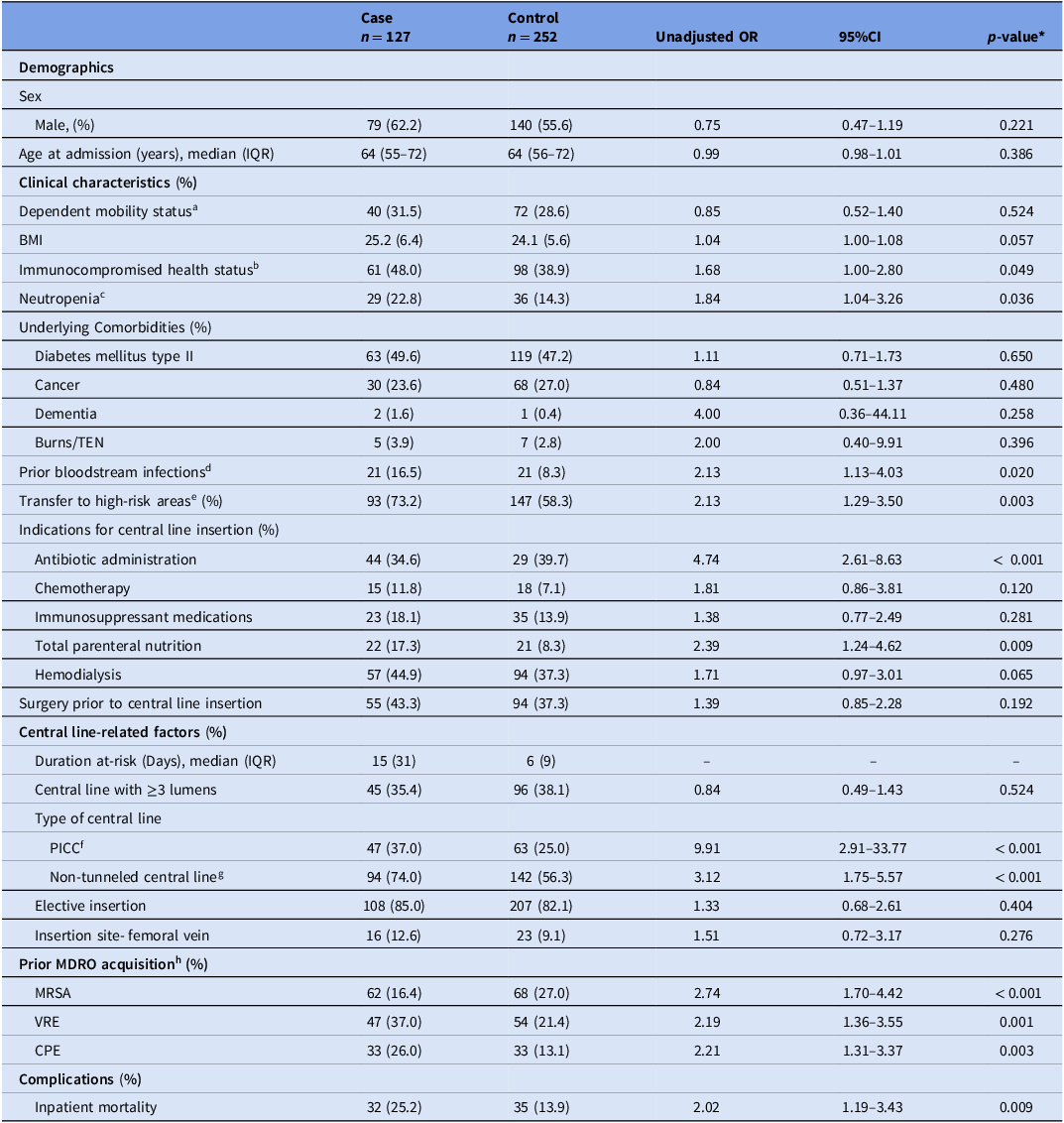

Table 1 summarizes the patient and central line-related factors. Variables significantly associated with HA-CLABSI in the bivariate analysis were immunocompromised health status (OR: 1.68, 95% CI: 1.00–2.80), bloodstream infection in the four weeks preceding central line insertion (OR: 2.13, 95% CI: 1.13–4.03), transfer to high-risk areas (OR: 2.13, 95% CI: 1.29–3.50), clinical indications for central line insertion including antibiotic administration (OR: 4.74, 95% CI: 2.61–8.63), and TPN (OR: 2.39, 95% CI: 1.24–4.62), insertion of PICC (OR: 9.91, 95% CI: 2.91–33.77) and non-tunneled central line (OR: 3.12, 95% CI: 1.75–5.57) and prior acquisition of MRSA (OR: 2.74, 95% CI: 1.70–4.42), VRE (OR: 2.19, 95% CI: 1.36–3.55), and CPE (OR: 2.21, 95% CI: 1.31–3.37) (Table 1). There was no correlation observed between these variables.

Table 1. Patient demographic and clinical characteristics and central line-related factors

Note. CI, confidence interval. IQR, interquartile range. BMI, body mass index. TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis. MDRO, multidrug-resistant organisms. MRSA, Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus; VRE, Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus. CPE, Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae.

Categorical data are shown as number (%), continuous data are shown in mean (SD) or median (IQR).

* Variables with p-value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

aMobility data was collected as of the admission notes. Dependent mobility was defined as “wheelchair bound, “bed-bound” or “requiring assistance” status.

bPatients with end-stage renal failure requiring hemodialysis and/or a history of transplant/hematological malignancy and/or receiving chemotherapy or immunosuppressants during the at-risk period.

cAbsolute neutrophil count < 100 cells/mm3.

dAny bloodstream infections in the four weeks preceding central line insertion for cases and controls.

eTransfer to any high-risk areas (i.e., intensive care unit, intermediate care area, high-dependency unit) within ±2 weeks of central line insertion.

fOther central lines (i.e., central venous catheter, port-a-cath, and vascular catheter) were used as the reference level for PICC.

gTunneled central line was used as the reference level for non-tunneled central line.

hAny MDRO acquired in the same admission, prior to central line insertion.

Transfer to high-risk areas (aOR: 2.03, 95% CI: 1.05–3.92), immunocompromised health status (aOR: 4.62, 95% CI: 2.20–9.69), clinical indications for central line insertion including antibiotic administration (aOR: 7.41, 95% CI: 3.24–16.92), and TPN (aOR: 3.61, 95% CI: 1.49–8.77), insertion of PICC (aOR: 13.61, 95% CI: 3.12–55.53) and non-tunneled central lines (aOR: 2.95, 95% CI: 1.48–5.87) and prior MRSA acquisition (aOR: 3.41, 95% CI: 1.83–6.35) were identified as statistically significant risk factors for HA-CLABSI (Table 2).

Table 2. Independent risk factors significantly associated with HA-CLABSI

Note. aOR, adjusted odds ratio, PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter. MDRO, multidrug-resistant organism. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

* p-value < 0.05 was considered significant in the backward stepwise multivariable conditional logistic regression.

aTransfer to high-risk areas (i.e., intensive care unit, intermediate care area, high-dependency unit) within ±2 weeks of central line insertion.

bOther central lines (i.e., central venous catheter, port-a-cath, and vascular catheter) were used as the reference level for PICC.

c Tunneled central line was used as the reference level for non-tunneled central line.

dMRSA acquired in the same admission, prior to central line insertion.

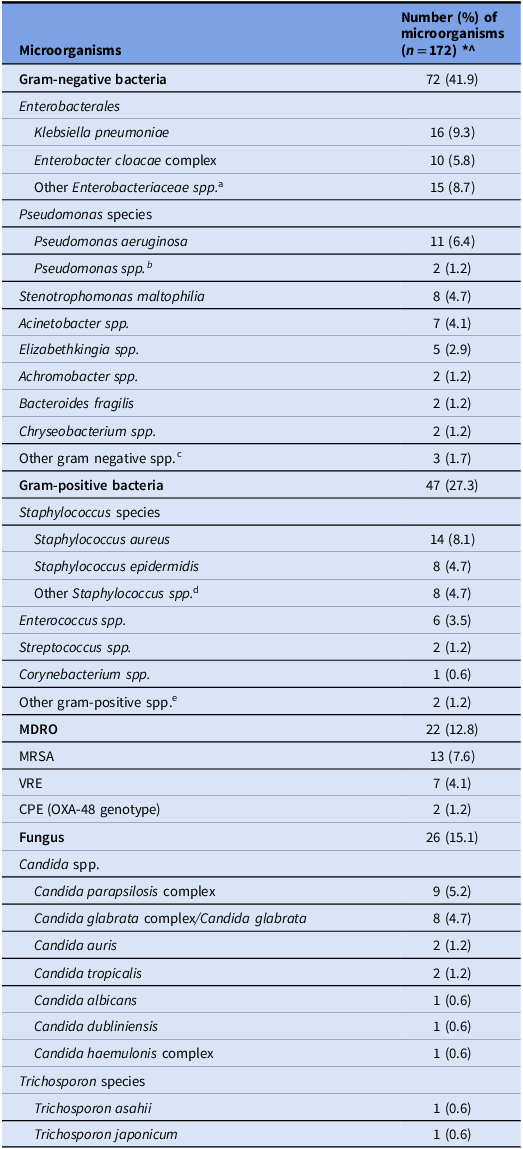

Table 3 describes the distribution of microorganisms causing HA-CLABSI. A total of 172 pathogens were isolated from 127 cases. Leading pathogens for HA-CLABSI were gram-negative bacilli (41.9%), followed by gram-positive bacteria (27.3%), fungi (15.1%) and MDROs (12.8%). Most common gram-negative bacilli were Klebsiella pneumoniae (9.3%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (6.4%), Enterobacter cloacae complex (5.8%), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (4.7%), and Acinetobacter spp. (4%). Staphylococcus aureus (8.4%), and Staphylococcus epidermidis (4.7%) were the predominant gram-positive bacteria. Candida parapsilosis complex (5.2%) and Candida glabrata complex (4.7%) were the most common causative fungi. Total MDRO burden was 12.8%, of which MRSA (7.6%), and VRE (4.1%) were common causative organisms.

Table 3. Distribution of microorganisms isolated from HA-CLABSI cases

Note. MDRO, multidrug-resistant organism. spp., species. MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. VRE, Vancomycin-resistant enterococcus. CPE, Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae.

* The total number of microorganisms exceeds the total number of CLABSI cases (n = 127).

^The percentages are calculated out of 172.

aOther Enterobacteriaceae spp. included one Citrobacter koseri, five Escherichia coli, three Klebsiella aerogenes, one Proteus mirabilis, and five Serratia marcescens.

bOther Pseudomonas spp. included one Pseudomonas putida and one unidentified Pseudomonas spp.

cOther gram-negative spp. included one Morganella morganii, one Rothia mucilaginosa and one unidentified Delftia spp.

dOther Staphylococcus spp. included three coagulase negative Staphylococcus, two Staphylococcus capitis, three Staphylococcus hemolyticus and eight Staphylococcus epidermidis.

eOther gram-positive spp. included one Leuconostoc spp. and one unidentified bacillus spp.

Discussion

Understanding the burden and risk factors can enable risk stratification of patients and development of targeted strategies for early identification and prevention of HA-CLABSI. Despite on-going infection prevention efforts, several studies report significant CLABSI incidence in their settings. Reference Baier, Linke and Eder19–Reference Mishra, Misra and Azim21 In a retrospective cohort study in 2020, Baier et al reported an IR of 10.6 per 1,000 central venous catheter-days and prevalence of 18.2%, from 610 hematologic-oncologic patients. Reference Baier, Linke and Eder19 In a nationwide study of acute-care hospitals in US from 2011 to 2017, Novosad et al reported 59,461 CLABSIs from adult ICUs and 40,763 from adult wards to the NHSN, Reference Novosad, Fike and Dudeck20 thereby highlighting the need for robust HA-CLABSI surveillance beyond critical-care areas. Mishra et al reported an IR of 17.04 per 1,000 catheter-days in a medical ICU over a 16-month period in an Indian tertiary hospital. Reference Mishra, Misra and Azim21 Our hospital-wide HA-CLABSI IR was 8.4 per 1,000 central line-days.

The known risk factors for HA-CLABSI include older age, underlying comorbidities, higher Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) score, neutropenia, administration of chemotherapy, immunosuppressants, parenteral nutrition and antibiotics, immunocompromised health status, hematological malignancies, prior surgery, insertion of other invasive devices, prolonged hospitalization and catheterization duration before CLABSI acquisition, prior ICU stay, multi-lumen central lines, concurrent use of ≥1central lines, non-tunneled central lines, position of central line, location of insertion and central line maintenance. Reference Rajandra, Yunos and Teo1,Reference Seo, Hwang and Shin12,Reference Baier, Linke and Eder19,Reference Mishra, Misra and Azim21–Reference Moriyama, Ando and Kotani23 Risk factors significantly associated with HA-CLABSI in our study were transfer to high-risk areas, immunocompromised health status, administration of antibiotics and TPN via central lines, insertion of non-tunneled central line and PICC and prior MRSA acquisition. These findings are aligned with existing literature. A recent multicenter study by Rajandra et al. involving three Malaysian hospitals found that patients with extended ICU stay were at almost two-fold higher odds of CLABSI. Reference Rajandra, Yunos and Teo1 Mishra et al reported that immunocompromised patients were at 10.5 times higher odds of developing CLABSI. Reference Mishra, Misra and Azim21 Ippolito et al demonstrated that patients receiving TPN were at 4.33 times higher odds of developing CLABSI. Reference Ippolito, Larson, Furuya, Liu and Seres24 Patients with prior ICU stays, immunocompromised health status and requiring administration of TPN and antibiotics are vulnerable to HAIs, such as HA-CLABSI, due to their severity of illness, multiple comorbidities, prolonged hospitalization, frequent clinical interventions, emergency insertions and utilization of multiple central lines. Reference Rajandra, Yunos and Teo1,Reference Alwazzeh, Alnimr and Al Nassri10,Reference Moriyama, Ando and Kotani23 These provide additional opportunities for compromising sterile barriers and enabling migration of microorganisms from patient’s skin and external surfaces to internal luminal surface of central lines, resulting in biofilms formation. Reference Haddadin25,Reference Opilla26 The high nutritional content of TPN can also promote intraluminal biofilm formation, which often harbors microorganisms that are drug-resistant and evade host immune responses. Catheter hubs are often primary entry sites for microorganisms and biofilm formation. Reference Opilla26 Therefore, infection prevention measures are crucial to prevent biofilm formation and pathogen colonization in central lines. Malnutrition in hospitalized patients can be exacerbated by dextrose infusion in TPN, leading to hyperglycemia and consequent suppression of patient’s immune system as a stress-response, thereby increasing susceptibility to infections such as HA-CLABSI. Reference Opilla26

Baier et al found the prevalence of CLABSI to be 18% in patients with non-implanted central lines. Reference Baier, Linke and Eder19 Non-tunneled catheters are temporary central lines that are inserted percutaneously and, therefore, account for majority of CLABSIs.Reference Haddadin25 In a prospective surveillance study, Templeton et al demonstrated that each additional lumen was associated with 4.4 times higher hazards of developing CLABSI. Reference Templeton, Schlegel and Fleisch27 However, in our study, utilization of multi-lumen central lines was not associated with HA-CLABSI.

The optimal site for central line insertion remains debatable. According to the Asia Pacific Society of Infection Control guidelines for CLABSI prevention, femoral catheters should be avoided due to higher risk of infections and deep vein thrombosis. Reference Ling, Apisarnthanarak and Jaggi28 Merrer et al demonstrated that femoral catheterization was associated with a significantly increased risk of CLABSI compared to subclavian site (19.8% vs 4.5%; IR of 20 vs 3.7 per 1,000 catheter-days). Reference Merrer, De Jonghe and Golliot29 This could be due to the relatively high concentration of skin flora in the groin region. Reference O’Grady, Alexander and Burns6 However, Marik et al in 2012 and Timsit et al in 2013 reported a comparable risk of infection between the three typical insertion sites (subclavian, jugular, and femoral vein). Reference Marik, Flemmer and Harrison30,Reference Timsit, Bouadma and Mimoz31 We found no significant association between femoral site insertion for central lines and HA-CLABSI in our study.

HA-CLABSI is associated with increased risk of complications. MDROs add to the existing complexity of clinical management of HA-CLABSI. Reference Alwazzeh, Alnimr and Al Nassri10 In this study, MRSA acquisition prior to central line insertion was significantly associated with HA-CLABI risk. MDROs (i.e., MRSA, VRE and CPE) accounted for 12.8% of the causative organisms identified. Predominant species causing HA-CLABSI were gram-negative bacilli followed by gram-positive bacteria and fungi. Enterobacterales species was the most common organism (14.5% of all isolates). Other settings have also revealed a shift in the dynamic hospital ecosystem from gram-positive to gram-negative bacteria. Reference Alwazzeh, Alnimr and Al Nassri10,Reference Novosad, Fike and Dudeck20,Reference Kale, Khodare, Pindi, Joy and Khillan32–Reference Pitiriga, Kanellopoulos, Bakalis, Kampos, Sagris and Saroglou35 Therefore, addressing pathogen profile, prevalence and antibiograms may offer insights into hospital bioburden, support clinical decision-making and enable development of focused infection prevention measures such as screening and decolonization protocols, surveillance methods and antimicrobial stewardship programs.

The risk factors identified in this study were largely modifiable, indicating HA-CLABSI in our setting may be preventable. Local and international guidelines recommend several evidence-based HA-CLABSI prevention strategies including, standardized central line insertion and removal checklists, aseptic technique, maximal barrier precautions, chlorhexidine-impregnated dressings, routine review of central line necessity to reduce dwell time, disinfection of catheter hubs, needless connectors, and injection ports before accessing central line, selecting tunneled central lines when long-term utilization is anticipated, staff training, care-giver education, and compliance audits. Reference O’Grady, Alexander and Burns6,Reference Ling, Apisarnthanarak and Jaggi28,Reference Malek and Raad36,Reference Morisi, Montani and Ehode37 HA-CLABSI surveillance in ICU and non-ICU settings is critical for identifying trends and reducing incidence. Given the significant association with TPN and antibiotic administration, judicious utilization of these interventions is warranted with regular assessments to discontinue when no longer necessary. Reference Lum, Yeong, Tan, Salazar, Lee and Ng38,Reference Ahmed, Hussein and Qurbani39 Furthermore, the significant association between prior MRSA acquisition and CLABSI supports importance of contact precautions, hand hygiene and consideration of antiseptic or antimicrobial impregnated central lines, and antimicrobial lock therapy for long-term central lines in mitigating HA-CLABSI risk. Reference Ling, Apisarnthanarak and Jaggi28,Reference Malek and Raad36 Emerging approaches such as individualized risk prediction scores may enable early identification of patients at risk of HA-CLABSI. Reference Herc, Patel, Washer, Conlon, Flanders and Chopra40

This study has several strengths. First, broad inclusion of hospital-wide HA-CLABSI patients enables a more comprehensive understanding of the risk across diverse inpatient settings where HA-CLABSI remains under-studied. Second, utilization of standardized NHSN definitions ensures consistency with international surveillance criteria and enables comparability of the findings. Third, temporal matching of cases and controls allows mitigation of any confounding effects due to pandemic-related changes in HA-CLABSI prevention practices, ensuring that both cases and controls were exposed to a similar risk environment. Lastly, being one of the largest tertiary-level hospitals, SGH receives a diverse patient population, therefore findings of this study may offer regional and local insights into HA-CLABSI epidemiology.

There were some limitations of this study. First, data collection relied on review of electronic medical records, which may introduce information bias due to potential inaccuracies in documentation, particularly for central line insertion and removal dates. Second, since this was a single-center study, the findings may have limited generalizability to other healthcare settings. Third, we did not analyze compliance rates and impact of our interventional bundles on HA-CLABSI incidence. Finally, residual confounding due to unmeasured variables cannot be excluded.

In conclusion, despite implementation of prevention bundles, HA-CLABSI remains of significant concern. Extending surveillance and prevention beyond ICU settings and understanding local epidemiology can guide tailored infection prevention measures.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the institution’s healthcare providers in preventing HA-CLABSI within the hospital and the efforts of microbiology laboratory colleagues in performing the cultures required for timely diagnosis.

Financial support

This research did not receive any funding form agencies in the public, private or non-profit sectors.

Competing interests

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.