Introduction

This paper is about the evolution of HIV and AIDS-oriented community and home-based care (CHBC) practices in Zambia. It discusses the origin of these practices in the mid-1980s when the AIDS epidemic inspired local responses to care for the sick and dying. It covers the processes which created, by 2011, a national HIV programme capable of providing hundreds of thousands patients with anti-retroviral treatment (ART) at primary health facilities. This programme is now a platform for further development of chronic care services, using the experience with addressing the long-term care needs of ART patients; the advent of ART having enabled HIV/AIDS to become a manageable chronic illness (Volberding and Deeks, Reference Volberding and Deeks2010; Deeks et al., Reference Deeks, Lewin and Havlir2013). We discuss the opportunities of this nascent chronic care system for confronting an emerging burden of chronic, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) as well as the erosion of this system, following a reduction in funding to CHBC and government interventions that have changed the nature of CHBC in the country.

CHBC in Zambia articulates local and international concepts of care. There is Zambian research which intimates this articulation (Chela and Siankanga, Reference Chela and Siankanga1991; Blinkhoff et al., Reference Blinkhoff, Bukanga, Syamalevwe and Williams1999; Nsutebu et al., Reference Nsutebu, Walley, Mataka and Simon2001; Bond et al., Reference Bond, Tihon, Muchimba and Godfrey-Faussett2005). It builds on the principles of community participation in Primary Health Care (PHC), social relationships, and values of mutual support in Zambian society. Community participation in health is a much debated topic (Bender and Pitkin, Reference Bender and Pitkin1987; Zakus and Lysack, Reference Zakus and Lysack1998; Morgan, Reference Morgan2001). The gist of the debate has been about whether community participation is a means to save health care costs or a tool to empower people to take responsibility of their own health. Boyce and Lysack (Reference Boyce and Lysack2000), for example, distinguish between top-down initiatives in which community participation amounts to the voluntary contribution of people’s time and resources towards a common goal, and transformational participation in which people’s capacities are developed to organise themselves and make decisions on issues that affect their lives (Boyce and Lysack, Reference Boyce and Lysack2000). This distinction refines previous critiques which differentiated ‘community-oriented’ and ‘community-based’ health care approaches. The former refers to the use of health management structures to determine community-level initiatives and to define the terms for community participation (Rifkin, Reference Rifkin1981). The latter refers to programmes which are aligned to local needs, and which have adjustable structures to respond to changes in local conditions (Kark, Reference Kark1981; Rifkin, Reference Rifkin1981; Tollman, Reference Tollman1991).

The Alma Ata declaration on PHC in 1978 invoked the transformational approach in its conception of community participation [World Health Organisation (WHO), 1978]. At country level, community health worker programmes would be the main vehicle to foster community involvement in health care (Walt, Reference Walt1988). Although African governments struggled to implement these programmes in the context of a global economic crisis (Walt, Reference Walt1988; Lawn et al., Reference Lawn, Rohde, Rifkin, Were, Paul and Chopra2008), civil society organisations (CSO) started mobilising settlement residents to respond to another crisis: the HIV and AIDS pandemic. These initiatives actively engaged patients, families and settlement residents to provide home-based care (HBC) to HIV-infected patients (Ncama, 2005). After 30 years, CHBC programmes continue to be appropriate in the context of changing health care needs in the population. They reflect the theory and practice for the delivery of health care to patients with chronic conditions (Wagner, Reference Wagner1998; WHO, 2002; Barr et al., Reference Barr, Robinson, Marin-Link, Underhill, Dotts, Ravensdale and Salivaras2003). For example, the emphasis on patient involvement in chronic care is based on the understanding that the largest share of chronic care takes place outside the health facility, for the patient primarily ‘self-manages’ his/her condition (Holman and Lorig, Reference Holman and Lorig2004; Gately et al., Reference Gately, Rogers and Sanders2007). ‘Self-management’ refers to patients managing the bio-physical, psychological, social and economic aspects of their conditions (Swendeman et al., Reference Swendeman, Ingram and Rotheram-Borus2009). It depends on family and community support (Swendeman et al., Reference Swendeman, Ingram and Rotheram-Borus2009), patients acquiring appropriate skills and knowledge to adopt new lifestyles and behaviours (Aujoulat et al., Reference Aujoulat, d’Hoore and Deccache2007) and to seek medical assistance when necessary (Lorig, Reference Lorig1993).

The earlier practices of HBC for HIV-infected patients have been documented (Uys, Reference Uys2002; Campbell and Foulis, Reference Campbell and Foulis2004; Ogden, Reference Ogden, Esim and Crown2006). However, there has been little research on current practices involving chronic care in Africa. Studies that describe chronic care practices in this region tend to focus on facility-based services (Samb et al., Reference Samb, Desai, Nishtar, Mendis, Bekedam, Wright, Hsu, Martiniuk, Celetti, Patel, Adshead, McKee, Evans, Alwan and Etienne2010; Levitt et al., Reference Levitt, Steyn, Dave and Bradshaw2011; Rabkin and El-Sadr Reference Rabkin and El-Sadr2011; Rabkin et al., Reference Rabkin, Kruk and El-Sadr2012; Aantjes et al., Reference Aantjes, Quinlan and Bunders2014a). Our study explored how community-based programmes mobilised people to help care for HIV-infected patients and, as ART became available, adjusted their services towards providing chronic care, including patient self-management support, in four sub-Saharan African countries. This paper discusses the findings from the Zambian component of the study in light of changes in government policy and strategies aimed at revitalising the country’s PHC services, as well as other developments which influence the nature of community participation.

Methods

The Zambian research was part of a multi-country study of CHBC programmes, conducted in 2011 and 2012, in Ethiopia, Malawi, South Africa and Zambia. The study used a historical, comparative approach to distinguish commonalities and differences between the four countries; an approach that is commonly used in the discipline of social anthropology (Pocock, Reference Pocock1961). The study had four research objectives. This paper draws primarily on the results from the first and second research objective:

-

(1) Explore the adaptations and changes in caregiving at the community level as the rapid scale-up of anti-retroviral therapy while focussing on the tasks of caregivers and the needs of their clients.

-

(2) Assess how and to what extent caregiving by informal caregivers at community level has been integrated in the health system and is being recognised as part of PHC structures and policies.

-

(3) Investigate the contributions, potential role of and benefits for caregivers in the expansion of HIV prevention, treatment and PHC programmes.

-

(4) Assess the potential means for formal and informal community health worker programmes to complement each other in the context of decentralisation of HIV treatment programmes, taking into account current initiatives and arrangements.

Criteria for country selection included the presence of a generalised HIV epidemic, well-established CHBC programmes (>10 years old) and national government commitment to the African PHC revitalisation agenda. The research was conducted in several parts by in-country research teams, supported by two project co-ordinators. The study design began with an online survey among international HIV and health experts to help define the foci and objectives of the proposed research and, thereafter, to inform the development of the research tools. The first part of the in-country studies included literature reviews and semi-structured interviews with key informants at national level. Informants included officials from health, social welfare and community development ministries, the national AIDS council, large care and support organisations, HIV patient networks and CHBC programme funders. The second part included in-depth study of selected CHBC programmes in each country. Selection criteria for the programmes were (1) they had been operational for >10 years; (2) their care models were generally representative of CHBC in each country; (3) were managed by different types of organisations; (4) offered diversity in care and range of patients; and (5) inclusion of rural and urban programmes.

Programme selection was guided by national advisory boards set up in each country, consisting of representatives of CHBC programmes, staff from national HIV programmes and community caregivers. Primary research methods included semi-structured interviews with programme and clinic staff, service observations, focus group discussions (FGDs), community mapping with caregivers, and structured interviews with patients and their relatives. Internal validation of the research included the use of standardised interview schedules and field work procedures in each country and verbatim transcription of the data from interviews and FGDs. Data analysis was standardised using structured coding and findings were validated via another round of key informant interviews and a questionnaire survey. The design of the questionnaire was based on key findings from the country analyses and sought to validate these with a wider range of community programmes/projects in each of the four countries. The survey was disseminated to 59 care and support organisations across four countries, with a response rate of 78%. Before dissemination, all survey questions were reviewed by an international reference group. This group, consisting of several UN agencies and international non-governmental organisations, monitored the study as a whole. National advisory boards monitored the quality and progress of the in-country studies. The qualitative data were analysed with the software programme Atlas.ti. The quantitative data were processed with SPSS software. Further details on the methodology can be found in another publication which presents findings on objectives 2 and 3 (Aantjes et al., Reference Aantjes, Quinlan and Bunders2014b).

All study informants provided written informed consent before study participation. The study was approved by the ERES Converge Ethics Review Board in Zambia (reference 2012/001) and the medical ethics review committee of the VU University in Amsterdam (reference 2011/180). Table 1 presents the sample sizes from the Zambian research and from the overall study.

Table 1 Informant samples

CHBC=community and home-based care; FGD=focus group discussion.

Findings

This section presents the research findings historically to show how community-based end of life care evolved to chronic care and how approaches to community participation in PHC changed over time in the context of global and national-level influences.

End of life care: local innovation (1985–1997)

The first Zambian AIDS case was reported in 1984 (WHO, 2005). Study informants reported that Zambian civil society responded to the increasing number of deaths by providing end of life care to afflicted individuals in their homes in 1985/1986. Christian churches were at the forefront of this initiative. They incorporated the concept of HBC into their health facility outreach programmes whereby medical teams visited patients and provided basic medical care. For example, the Salvation Army which had a hospital and clinics in the south of the country, had teams who visited patients with tuberculosis (TB) and leprosy and who then began to visit HIV and AIDS patients. The medical teams started to draw on the assistance of trained lay-volunteers who, on occasion, replaced these teams to reduce costs and increase contact time with patients and families. The development of these HBC programmes coincided with national health reforms in Zambia; notably, decentralisation of health services in line with the PHC agenda set at Alma Ata and following the WHO’s decentralisation model (WHO, 1978; Bosman, Reference Bosman2000; Bossert et al., Reference Bossert, Chitah and Bowser2003; Lawn et al., Reference Lawn, Rohde, Rifkin, Were, Paul and Chopra2008). The reforms involved establishing health posts and clinics and mobilising settlement residents, via neighbourhood health committees, in primary health care. The government’s health decentralisation policy created favourable conditions for further development of the HBC concept and more use of lay-volunteers. In 1986, the Churches Health Association of Zambia (CHAZ) officially adopted the HBC model. In 1991, the Catholic Diocese of Ndola established a large HBC programme in the north of the country. By 1992, 47 HBC programmes were registered in the country (Ministry of Health, 1994).

HBC programmes were also established by CSOs independently of church-based initiatives. For example, in 1996, Bwafwano established a programme in Lusaka, using volunteers to care for TB and AIDS patients who had little or no family support. These volunteers were generally elderly women motivated by their religious beliefs and sense of duty; as one study informant stated

‘There was a problem and it needed to be fixed’.

(Community caregiver, FGD)

By 1996, there were over 100 HBC programmes (Illife, Reference Illife2006). Two factors shaped HBC in the 1990s: the relative lack of government involvement in HBC and the provision of care largely by familiar lay-persons responsive to patient needs. The Zambian government acknowledged the importance of HBC, but viewed it as a form of pastoral care by churches. Linkages between volunteer caregivers and medical staff at PHC facilities were merely to facilitate home nursing. A few ‘AIDS care handbooks’ were in circulation (WHO, 1993), but the basis for HBC was charity. A study informant, who had been a doctor in the Salvation Army’s HBC programme, reported there was limited external funding. Christian organisations provided care and support mostly with their own resources and via congregation members.

Patients’ needs informed the practices of family and volunteer caregivers. The roles of medical staff were largely to monitor patients’ health, treat opportunistic infections and encourage family members to give care. In contrast, the caregivers provided basic nursing care, bathed patients, washed clothes, did household chores, ensured patients ate their food, encouraged family members to care for their afflicted kin, mobilised broader support (e.g., food donations) and reminded those on TB treatment to take medicines. In other words, the practice of care drew upon and cultivated social relationships amongst kin, neighbours and acquaintances within settlements.

End of life care: professionalisation of HBC (1998–2004)

Elaboration of HBC through collaboration between CSOs and government agencies occurred from the late 1990s. A foundation was the introduction of formal training for caregivers. CSOs developed Ministry of Health (MoH)-approved training and care manuals and, increasingly, international NGOs began to provide financial support. CHBC informants reported an increase in donor funding from early 2000s onwards. This was also the period when the content of HBC was formally defined. Training courses set out medical standards for basic nursing care in people’s homes, protection of caregivers, detection and treatment (under supervision) of opportunistic infections, pain management, diagnosis and care of TB (co-infected) patients. Caregivers were supplied with ‘HBC kits’ which included surgical gloves, bandages, pain killers, oral rehydration salts and other non-prescription medicines. ART became available in Zambia, but few patients could afford the cost of ~U$8 per month.

The government acknowledged HBC programmes as a component of the health system yet separate to government health services. It did not create regulatory frameworks; instead, international NGO stipulations set the benchmarks for standards of care and voluntary work. One prerequisite for funding was that CSOs employed nurses to supervise the caregivers. Some programmes began to provide non-financial incentives to retain caregivers (e.g., t-shirts, bags, food). HBC programmes also started to create broader support mechanisms; for example, farmer support groups to help provide food for very poor HIV-afflicted individuals and households. The model changed from hospital-based HBC, using mobile medical teams, to a model that concentrated care within settlements and in the hands of volunteer caregivers. Some CSOs had offices on government or mission hospital premises as a result of collaborative arrangements but, generally, HBC programmes became distinct adjunct entities involved in the organisation and management of caregivers in settlements:

‘you may realise that the issue of HBC was not born in a government agency, it was born by civil society organisations and more specifically by the faith-based organisations … the government came on board very late, we were actually almost in the second or third stage of HIV and AIDS [that is] when they recognised that we needed to have this type of workforce’.

(Senior manager CHAZ, semi-structured interview).

From end of life to chronic care: diversification of HBC (2005–2011)

In August 2004, ART became freely available in public hospitals (Schumaker and Bond, Reference Schumaker and Bond2008). Later, as ART patients recovered their health, HBC programmes found they needed to provide support as much as care for these patients. This is not to say that end of life care was no longer necessary; only that the demand for various support services increased whilst demand for end of life care decreased.

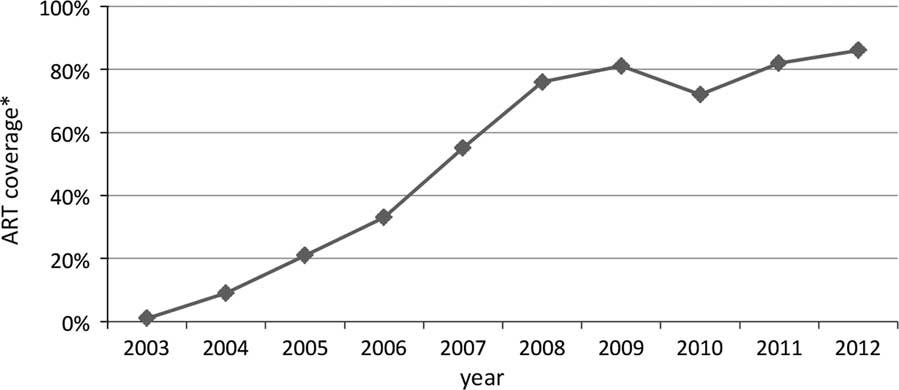

Study informants reported rapid diversification of HBC services during this period and programmes evolved into what are now commonly known as CHBC programmes. Figure 1 illustrates the changes in relation to the rapid increase in the number of ART patients, which, by 2012, served 450 000 patients (UNAIDS, 2013). Foreign funding facilitated this expansion (Ainsworth and Over, Reference Ainsworth and Over1997; Oomman et al., Reference Oomman, Bernstein and Rosenzweig2007; Ndubani, Reference Ndubani2009).

Figure 1 Zambian treatment coverage. *The percentages refer to the share of all eligible for anti-retroviral treatment who are receiving it. Source: WHO/UNAIDS 2003–2012 estimates.

Volunteer caregivers became involved in promoting the national ART programme by motivating patients to register for treatment, encouraging people to go for voluntary counselling and testing and, in time, monitoring patients.

‘HBC has evolved over the years from mediators to the provision and advice on HIV and AIDS, including the administration of ART’.

(Community representative, FGD)

CSOs introduced support services in response to the changing needs of their patients. Patients and caregivers were unequivocal about the reasons: patients on ART need psychosocial and economic support to re-establish their lives and, notably, nutritional support. CSOs relied on patient support groups, farmer and business groups to assist ART patients. The programmes addressed issues such as nutrition, infection prevention, management of side-effects, establishment of vegetable gardens, formation of cash savings groups and ways to start small businesses. Local gatherings were a means for broad dissemination of information on ART, on patient needs and for mobilising local assistance. CHBC programmes also began to assist the elderly and people suffering from NCDs, though volunteer caregivers did not have formal training in this area. In sum, CSOs fostered ‘community’ in the sense of diverse forms of assistance to patients and their households by fellow settlement residents. This amounted to mutual support in a context where virtually all Zambians had been affected in some way by the HIV pandemic.

In 2007, the MoH began to regulate CHBC programmes, beginning with ‘National Minimum Standards for CHBC Organisations’ (National AIDS Council, 2007). The document updated standards for caregiver training courses and set standards for the new activities that caregivers were doing (e.g., treatment literacy, ART adherence). The MoH also started its own CHBC programmes in selected health facilities. These programmes recruited and trained volunteers who were supervised by medical staff at PHC facilities. The overt difference to the CSO-led programmes was that these volunteers focussed primarily on treatment adherence, counselling and tracing patients who defaulted on their medicinal regimens. In 2008, the government adopted a WHO-driven strategy to ‘revitalise’ PHC services (WHO, 2008). It led to plans to increase the number of nurses employed by the MoH and deployed to PHC facilities, and to recruit ‘community health assistants’ (CHAs) as state-paid community health workers.

By 2011, the key actors as described in chronic care service models (Wagner, Reference Wagner1998; WHO, 2002; Barr et al., Reference Barr, Robinson, Marin-Link, Underhill, Dotts, Ravensdale and Salivaras2003) were in place (‘community partners’; patients; families) or were anticipated (health care teams at PHC facilities). CSOs provided health and social care for the prevention and management of chronic conditions. Their programmes applied the principle of patient ‘self-management’ through multiple, overlapping social relationships between patients, their families and volunteer caregivers. In summary, two important processes occurred from 2005–2011. One, was the diversification of CHBC programme services which, together with the collaboration between government and CSOs in the delivery of ART, created the country’s first large-scale chronic care programme. The other, was the PHC revitalisation agenda which directed the government’s attention to strengthening primary-level services. As we discuss in the next section, these processes laid the foundation for the integration of CHBC programmes into government PHC services.

Chronic care: medicalisation of CHBC programmes (post-2011)

By 2012, the government had revised health and economic development strategies via the Sixth National Development Plan (Government Republic of Zambia, 2011), the National Health Strategic Plan 2011–2015 (Ministry of Health, 2011) and a National Health Policy (Government Republic of Zambia, 2012). The common ethos within these initiatives was commitment to addressing the social and bio-medical determinants of health by aligning health with national economic policies. PHC services were the focus of attention and this was expressed in the new health policy’s commitment ‘to bringing health care as close to the family as possible’, plans to build an additional 650 PHC facilities according to health officials, and plans to merge the portfolios of PHC, social welfare and community development under a single new Ministry of Community Development, Mother and Child Health (MCDMCH, 2013). In addition, according to MoH officials, the government began in 2012 to recruit 3000 nurses and to train the first cadre of a projected 5000 CHAs. It should be noted that these plans were put into effect after the end of this study. Follow-up interviews in 2013 and 2014 with health officials revealed that the nurses had been recruited, construction of PHC facilities was ongoing and that the first cadre of CHAs had been deployed. Furthermore, the thrust of the initiatives was to integrate CHBC programmes into PHC services by making PHC facilities the focal point for management and for CHAs to be responsible for the supervision of community-based activities.

However, in 2012, contradictions were already surfacing in these efforts to integrate CHBC programmes with PHC services. Notably, the orientation of these programmes to address the social and bio-medical determinants of health was constrained by what can be described as ‘medicalisation’ of health care; meaning that volunteer caregivers were increasingly directed to enabling PHC professionals to implement international medical guidelines for treating ART patients (WHO, 2010; Schwartländer et al., Reference Schwartländer, Stover, Hallett, Atun, Avila, Gouws, Bartos, Ghys, Opuni, Barr, Alsallay, Bollinger, de Freitas, Garnett, Holmes, Legins, Pillay, Stanciole, McClure, Hirnschall and Laga2011). Table 2 shows the results from our questionnaire survey among a sample of nine CHBC organisations in Zambia. It reveals the extent to which these organisations and their caregivers are involved in service provision at PHC facilities. The two quotes below illustrate how health officials understand this role:

‘… they (community caregivers) play a critical role …. volunteers help with triaging, keeping records, tracking patients out in the community, linking patients to different services, offering peer support or possibly participating in health education talks, emotional support and all that, so without that cadre there, the programme starts to fall into pieces. In government clinics, …. they are doing the same things as in partner supported facility like patient registration, patient flow in the clinic, helping patients get to the right provider at the right time, weighing patients, help the patients count through their pills, offer adherence counselling, and if patients are missing clinic visits, they go out into the community and track the patients and bring them back into care’.

(MoH official, semi-structured interview).

‘They have a critical role to play to support the whole process. They will need to talk about health education of the client, touching on critical issues like adherence, following up patients in the communities, those who don’t come for follow-ups’.

(WHO country office official, semi-structured interview).

Table 2 Support services provided by community and home-based care (CHBC) organisations to local health facilities

ART=anti-retroviral treatment.

The redefinition of roles was succinctly illustrated in a report from an informant in one large CHBC programme which had retrained its caregivers, at the instigation of their funders, to be ‘adherence support’ workers and to work in teams under the guidance of health facility staff. A MoH official stated that ‘the MoH is not up to destroying the volunteer spirit in the community’, but volunteer caregivers voiced their discontent in interviews about being unpaid health workers under the supervision of (paid) CHAs. From their perspective, CHAs were different to them only in that they met the MoH’s recruitment standards such as standard of education. Furthermore, CHAs would not necessarily be deployed in their home settlements and, therefore, some would lack familiarity with the social relations and networks which facilitate community participation in health care. In other words, as one CHBC programme manager indicated, the government’s initiatives were ignoring fundamental reasons for the utility of volunteer caregivers:

‘These people are found within these localities, so they operate within their locality because they understand the community, they understand the culture, they understand the people, they understand the problems, they experience the problems together with everyone so that gives them a passion to do the work’.

(CHBC programme manager, semi-structured interview).

It should be noted that CHBC programmes were also under threat as a result of large-scale losses of funding from donors, as one informant highlighted:

‘In terms of HBC and OVC [orphans and vulnerable children] care I think international funds have dried up for that. That is my view and I think they are at a point where they are saying communities can do it on their own. We have had eight years to build their capacity and set up systems’.

(Manager of a large care organisation, semi-structured interview).

Furthermore, the new MCDMCH which was created in late 2012 was given the responsibility of engaging with CSOs and with traditional and local government authorities, but did not have detailed plans. The responsibilities included registering CSOs, promoting co-ordination of their activities and collaboration with CHAs and similar level state workers in other sections of the new ministry. However, the MCDMCH’s strategy for 2013–2016 did not contain procedures on how it would fulfil its responsibilities (MCDMCH, 2013)Footnote 1 .

In summary, post-2011, CHBC was changing from a conglomeration of services that were evolving parallel to government’s PHC services, towards integration of the former into the latter. The different agencies had a common purpose: to expand the content, and improve the delivery of PHC. However, CSOs, government ministries and international agencies had different perspectives on the structure, organisation and meaning of community-level health care.

Discussion

We have demarcated qualitative shifts in the form of HIV and AIDS community-based care over time in the following terms:

-

∙ Mid-1980s–1997: ‘Local innovation’ according to local cultural values and norms and capabilities of existing health service infrastructure, the latter leading to hospital-based organisation of HBC and community care.

-

∙ 1998–2004: ‘Professionalisation’ of HBC programmes via introduction of training for volunteer caregivers and establishment of HBC standards.

-

∙ Mid-2000s–2011: ‘Diversification’ of HBC leading to CHBC programmes providing support as much as care in the context of advent and expansion of ART programme and nascence of a chronic care system.

-

∙ Post-2011: ‘Medicalisation’ of CHBC programmes in the sense of a re-emphasis of the bio-medical components of PHC service delivery and ART treatment (albeit alongside government initiatives to address the social determinants of health).

For 30 years, there has been extensive mutual support amongst residents in many settlements to ease the suffering wrought by HIV and AIDS, facilitated by CSOs. This entailed continuous interventions to replace volunteers and to sustain involvement of different residents and social groups as a result of generational change within families and households. In other words, Zambia has shown what ‘community mobilisation’ and ‘community participation’ means: pragmatism, invocation of cultural values that emphasise social relationships between settlement residents, creation and use of social networks and organisation of people on the basis of these linkages by CSOs who provide direction guided by the expressed needs of patients. The findings of the research show how local initiatives of home care developed into distinct community home-based care programmes in Zambia. These programmes initially occupied a niche position but, over time, became part of the national health system and helped accelerate the access to ART as well as establish the capacity to provide chronic care for HIV patients at primary health and community level.

However, the findings also point at how government interventions since circa 2010/2011 are changing the nature of the relationship between ‘communities’ and PHC medical staff. First, the ethic of care and support provided by familiar peers according to the needs of the patients is contradicted by volunteer caregivers becoming quasi-authorities (e.g., ‘adherence support’ workers) who are answerable to PHC clinics; a trend which has occurred elsewhere (Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Hlophe and van Rensburg2008). Second, the introduction of CHAs signal movement away from a PHC system reliant on community caregivers, towards one that is run by medical staff via state-employed community health workers.

The methodological limitation within the Zambian government’s efforts to improve PHC services, lies in the tacit premise of community-oriented interventions; meaning government engagement with ‘communities’ to extend government services to citizens who do not receive these services. The limitations of this premise, notably the impediments to community participation and emphasis on bio-medical perspectives on health care, have been voiced in the past (Rifkin, Reference Rifkin1981; Morgan, Reference Morgan2001). In contrast, CSOs, during the course of their evolution, worked from a different premise of community-based interventions. This is expressed in the extensive involvement of ‘communities’ in the care and support of HIV patients as well as in their flexibility to adapt as the needs of HIV-infected patients changed and to support people with other chronic diseases and the elderly in the community.

At root, our argument in support of the ‘community-based’ methodology of CHBC programmes is that Zambian CSOs have mediated the interests of patients and medical staff by building social networks and structures to facilitate the delivery of, and people’s access to, diverse forms of treatment, care and support. In this instance, the argument refers to the large body of literature on the theory and practice of appropriate mechanisms that enjoin diverse agencies to create and apply knowledge for practical purposes and for mutual benefit (Kay and Bawden, Reference Kay and Bawden1996; Cash, Reference Cash2001; Guston, Reference Guston2001; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Datta and Jones2009; Regeer and Bunders, Reference Regeer and Bunders2009; Drimie and Quinlan, Reference Drimie and Quinlan2011). To be more precise, Zambian CSOs have played a critical brokering role between ‘communities’ and government agencies to facilitate ‘health care as close to the family as possible’. Furthermore, they have incorporated the mechanisms that are considered central in the provision of chronic care. We refer here to the empowerment of people to take responsibility, collectively, for their health (Aujoulat et al., Reference Aujoulat, d’Hoore and Deccache2007; Fumagalli et al., Reference Fumagalli, Radaelli, Lettieri, Bertele and Masella2015) and, related, the promotion of patient self-management (Greenhalgh, Reference Greenhalgh2009; Swendeman et al., Reference Swendeman, Ingram and Rotheram-Borus2009). The different mechanisms are critical enablers in the delivery of comprehensive care and a continuum of care at primary health and community level, and as the demands for lifelong treatment and care from patients with chronic HIV and NCDs increase.

Conclusion

This history of CHBC programmes in Zambia has focussed on the meaning and practice of community participation, the development of PHC services, and how the programmes represent a local model of chronic care. Our research shows that the Zambian authorities work with the concept of community-oriented participation. We refer here to the equation of community with settlements and their residents who need to be reached by the government’s health services and to the lack of evidence in policy, strategy and planning documents, which indicates appreciation of community as a qualitative construct. Equally, our research shows that CHBC programmes have demonstrated how to construct ‘community’ and, thereby, to sustain community participation in the development and delivery of PHC services.

Our contention is that the Zambian government is facing a specific challenge now. It risks losing the ground gained in turning HIV into a manageable disease and in establishing chronic care services if it does not recognise the limitations in its ‘community-oriented’ approach to improving PHC services. Simply put, allow CHBC programmes to run down, which is happening due to loss of funding, and Zambia will lose its capacity to promote and sustain community participation in the delivery of health care at primary and community level. The solution is to invest in them and enhance their brokering role.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank in-country researchers Greg Saili and Alice Mwewa for their contribution towards the field work and analysis.

Financial Support

The research was funded by Cordaid and UNAIDS. Cordaid, UNAIDS and the Caregivers Action Network reviewed the research protocol and provided guidance during the implementation of the research. Data analysis was undertaken by the named authors who made the final editorial decisions about the manuscript. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views, nor the stated positions, decisions or policies of Cordaid, the UNAIDS Secretariat or any of the UNAIDS Cosponsors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.