Introduction

COVID-19 restrictions were lifted on 1 February, but new challenges arose with the Russian invasion of Ukraine later in February, and the report from the Mink Commission on 30 June (Minkkommissionen 2022). While the former resulted in a referendum on 1 June on the absolution of Denmark's opt-out from EU defence, the latter resulted in a general election on 1 November. Hence, 2022 became an eventful year in Danish politics with a referendum, a general election, new relevant parties and a new type of government.

Election report: Referendum on EU opt-out and general election

Referendum on EU defence opt-out

After the Danes rejected the Maastricht Treaty in a referendum in 1992, Danish opt-outs on defence, justice, the euro and European Union citizenship were secured by the Edinburgh Agreement, which was supported at a referendum in 1993. In 2000, the Danes voted ‘no’ to adopting the euro, and in 2015, they declined to abolish the opt-out on home and justice matters. However, in a referendum on 1 June 2022, the defence opt-out was abolished. Table 1 shows that a large majority of 66.9 per cent voted in favour of abolishing the opt-out (hence 33.1 per cent against), with turnout at 65.8 per cent. An obvious explanation for the Danes’ ‘yes’ is the urgency of the defence issue caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. However, neither the financial crisis nor terrorist and migrant crises had worked in favour of a ‘yes’ vote on the other Danish EU opt-outs in the past (Prakash Reference Prakash2022).

Table 1. Results of the referendum on EU opt-out in Denmark in 2022

Source: Danmarks Statistik (2022a).

The 2022 general election

It is the prerogative of the Danish Prime Minister to call elections (election periods can last for a maximum four years). Opinion polls showed ‘rallying around the flag’ and increased support for the Social Democrats during the COVID-19 pandemic as has been seen elsewhere (Aylott & Bolin Reference Aylott and Bolin2023). However, the electoral surplus diminished shortly thereafter. As part of the handling of COVID-19, the government decided to close down the mink industry. The legality of the process was questioned (see Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2022). In light of the report from the Mink Commission (Minkkommissionen 2022), the Social Liberals (Radikale Venstre) announced on 2 July that they required the Prime Minister, Social Democrat (Socialdemokratiet) Mette Frederiksen, to call a general election prior to the opening of Parliament season on the first Tuesday of October. Otherwise, they would withdraw their support for the government, resulting in a vote of no confidence. On 5 October, Frederiksen called the election for 1 November 2022. Based on the polling, Frederiksen would have preferred to postpone the general election, as this could be held as late as 4 June 2023.

Even for Danish standards, a high number of parties (14 in total) fielded candidates across the 10 electoral districts for the 175 seats in Parliament elected in Denmark. In addition to the 10 parties elected in 2019, the Christian Democrats (Kristendemokraterne) stood for election as they have since 1971. Furthermore, three new parties had been formed. MPs who had left the Alternative (Alternativet) formed Independent Greens (Frie Grønne) (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2021), and two former prominent Liberals, Lars Løkke Rasmussen and Inger Støjberg, had both formed their own parties, respectively, the Moderates (Moderaterne) and the Danish Democrats (Danmarksdemokraterne) (See political party report below).

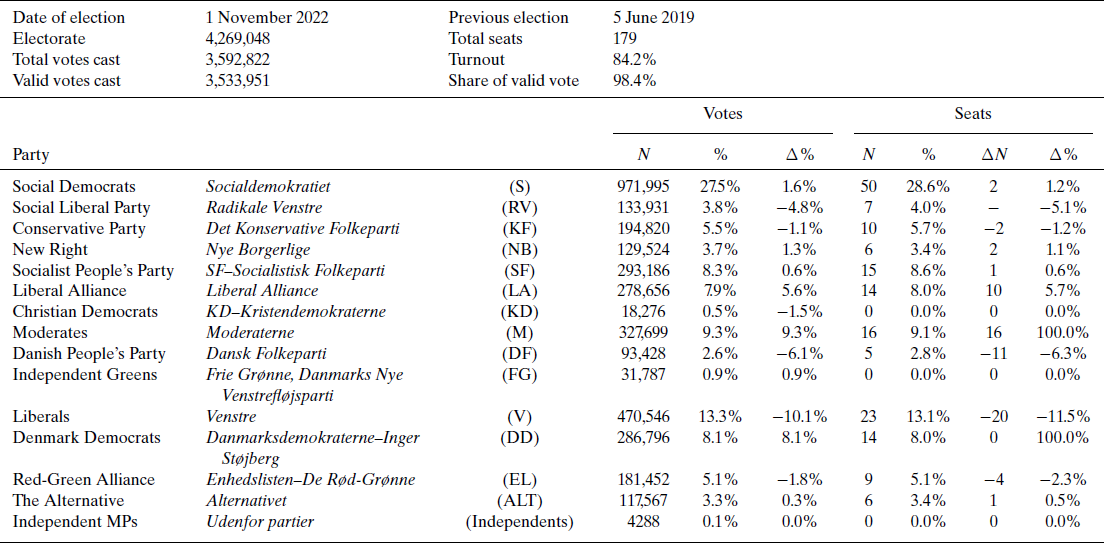

Table 2 shows the election results. The first overall result that is worthy of mention is that there is no longer a large party on each side of the political spectrum but only one, the Social Democrats. Second, two new parties (the Moderates and the Danish Democrats) made it into top 5 in 2022. The Moderates fared much better than initial polls suggested, and their 9 per cent of the vote and 16 seats was an impressive result for a new party. The Danish Democrats picked up both candidates, MPs and voters from the imploding Danish People's Party, which may at least partly explain how a party formally registered in June 2022 sprinted into Parliament with 14 seats (8 per cent of the vote) in November.

Table 2. Elections to the Parliament (Folketinget) in Denmark in 2022

The results for the rest of the parties showed wide variation. The losing sides comprise both drastic losses for the Liberals, Social Liberals and Danish People's Party and more moderate losses for the Conservatives and Red-Green Alliance. On the winning side, the Liberal Alliance more than doubled its support. For the remaining parties, the 2022 results were not that much different from those in 2019.

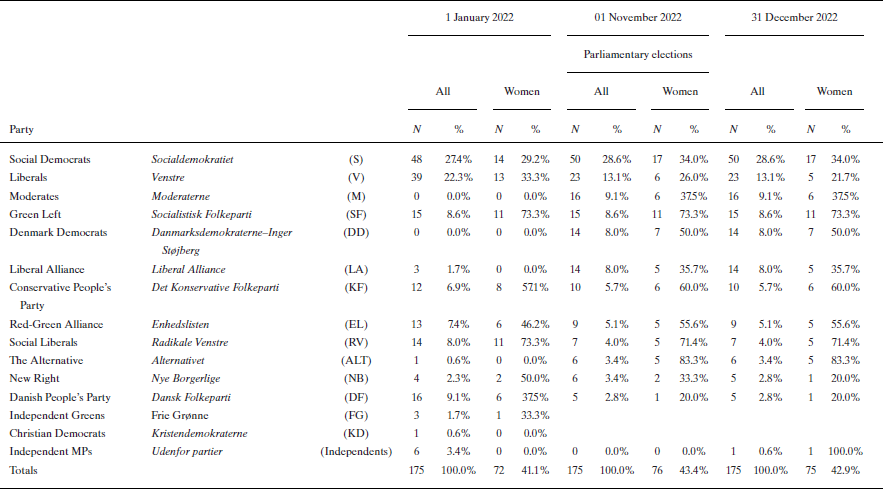

Danish turnout is, in international comparison, high (Hansen Reference Hansen, Munk Christiansen, Elklit and Nedergaard2020), but it saw a (further) drop from 85.9 per cent in 2015 and 84.5 per cent in 2019 to 84.2 per cent in 2022. The share of women in Parliament reached a record high at 43.6, surpassing 40 per cent for the first time in an election (Folketinget 2023b).

The major parties still hold the monopoly on prime ministers, but the ‘old core’ of the party system (Social Democrats, Liberals, Conservatives and Social Liberals) has been challenged. These parties usually got at least two-thirds of all votes (Kurrild-Klitgaard & Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen, Kurrild-Klitgaard and Lisi2019). However, in 2015, their support took a dip (49 per cent), and while they regained their strength in 2019 (68 per cent), their vote share is back at a lower level (51 per cent) in 2022. This is even markedly lower than the 59 per cent they got at the historic 1973 ‘Landslide Election’, where the four old parties lost 54 seats.

Finally, while the share of invalid votes has been increasing for the past 50 years, this election saw a marked increase both in the share of total invalid votes and in the share of blank votes. Hence, 1.3 per cent of the Danish voters turned up but refrained from supporting any of the 14 parties and their candidates on the ballot.

In addition to the 175 seats elected in Denmark, four MPs are elected in Greenland and The Faroe Islands (see Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2023).

Cabinet report: From Mette Frederiksen I to a very different Mette Frederiksen II

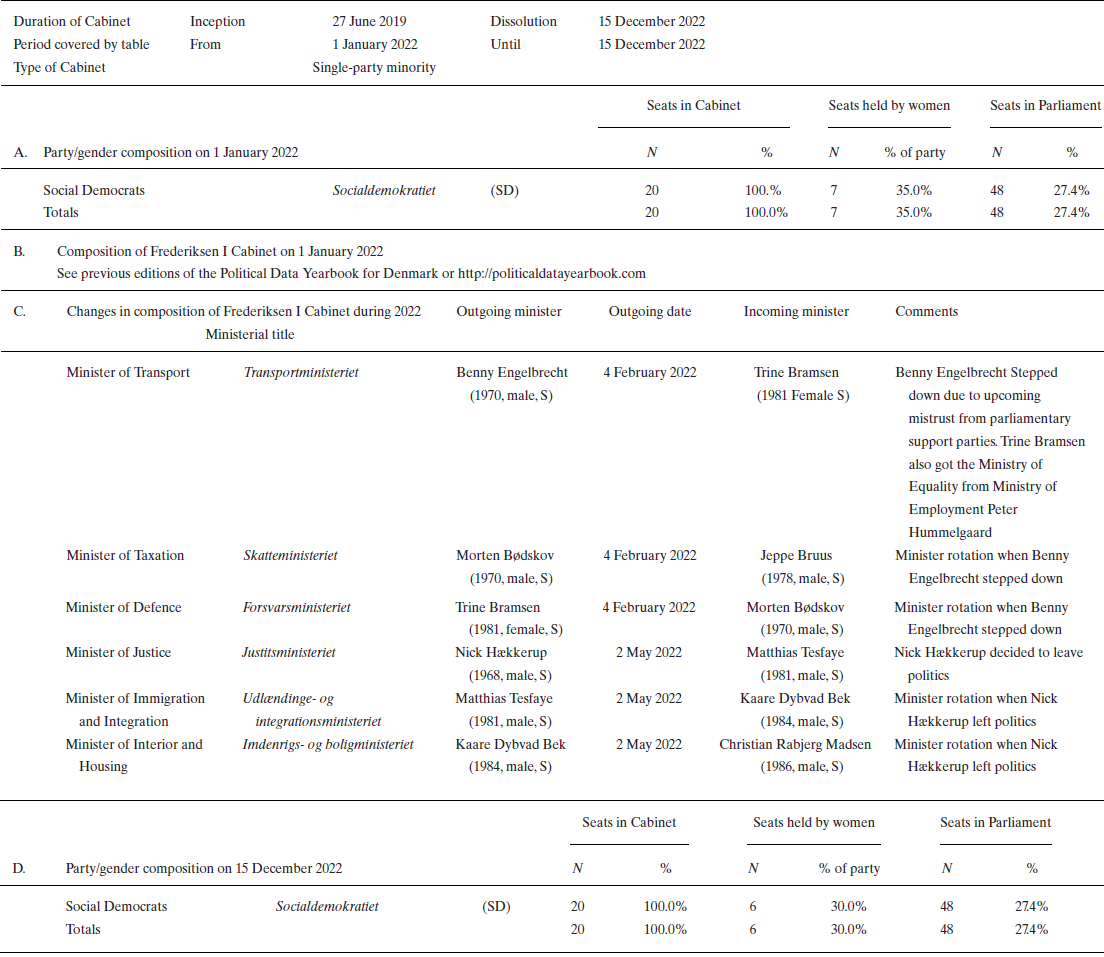

A Cabinet reshuffle took place on 4 February in Mette Frederiksen's minority single-party Social Democratic government. A majority in Parliament across the government's parliamentary support and opposition parties lost trust in Minister of Transport Benny Engelbrecht when it became known that estimates on the climate impact of a large infrastructure project had been withheld. He decided to step down before this lack of trust would manifest in a parliamentary vote (Hagedorn & Lauritzen Reference Hagedorn and Lauritzen2022). Trine Bramsen, who was challenged as Minister of Defence due to her decision of dismissing the director of the Defence Intelligence Service (Forsvarets Efterretningstjeneste), replaced Engelbrecht in the Transport Ministry and, in addition, got the portfolio of Equality from Ministry of Employment Peter Hummelgaard. Morten Bødskov took over as Minister for Defence, and in turn, Jeppe Bruus replaced him in the Ministry of Taxation.

Another Cabinet reshuffle took place on 2 May. Minister of Justice Nick Hækkerup left politics to become director of the interest group of Danish breweries. He was replaced by Mattias Tesfaye, whose Ministry of Immigration and Integration was taken over by Kaare Dybvad Bek, who in turn left the Ministry of Interior and Housing to Christian Rabjerg Madsen. All in all, promotions went along the expected lines. Hækkerup (born 1968), who is out of a political dynasty on his father's side with several MPs and ministers all along from when democracy was formed in 1849, and who has been in politics almost all his career, argued that he left to have a life after politics. Table 3 sums up the minister changes.

Table 3. Cabinet composition of Frederiksen I in Denmark in 2022

Sources: Kosiara-Pedersen (Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2022); Regeringen (2022a).

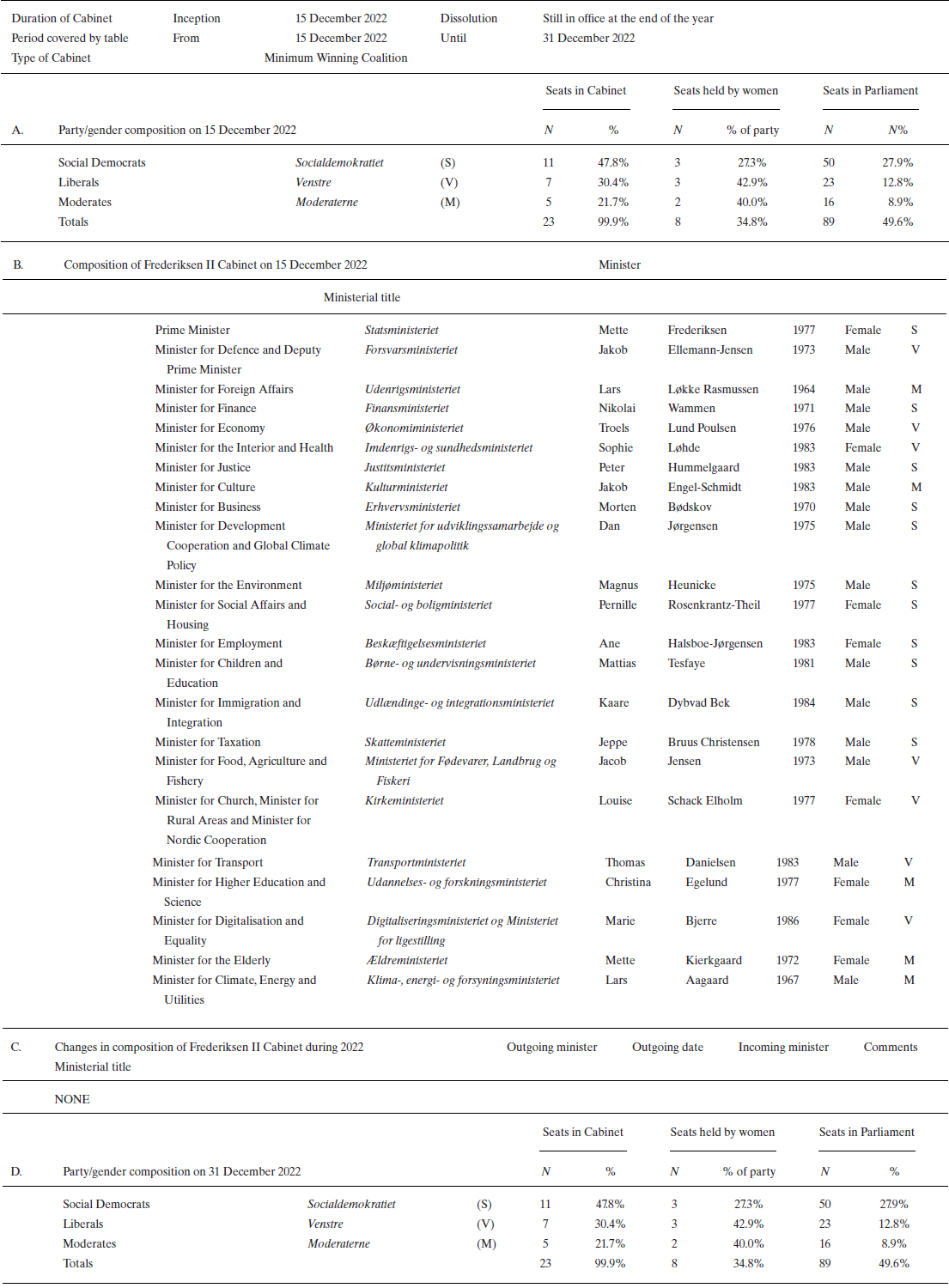

Turning to the government formation after the general election, things changed. Following an almost 30-year period, 1982–2011, where Denmark had long-serving prime ministers (viz., a Conservative right-of-centre PM between 1982 and 1993, a Social Democrat centre-left PM between 1993 and 2001, and a Liberal right-of-centre PM between 2001 and 2011), the period since 2011 had been characterised with government shifting side at all elections. However, in 2022, Frederiksen broke this stream and remained in office but in charge of a very different government. At the election, the centre-left bloc of parties got a marginal majority when including the three North Atlantic MPs (two from Greenland and one from the Faro Islands). Hence, Frederiksen was appointed formateur after a ‘Queen round’ (where all parties give advice on what government they would support). Nevertheless, rather than aiming for a centre-left government, Frederiksen wanted to pursue the idea already proposed in June 2022, and repeated during the election campaign, of forming a government across the left–right divide.

Government negotiations lasted a record-long six weeks, but on 15 December 2022, a new government was formally formed (Regeringen 2022a, 2022b), made up of the Social Democrats, Liberals and Moderates. As can be seen in Table 4, it commanded 89 of the 179 seats, a de facto majority due to the North Atlantic seats usually not voting on issues that do not directly affect their territories. This was a historic government in several ways, truly across the aisle, including the two dominant Prime Minister parties since WW2. The Social Democrats and Liberals had only collaborated in government once, shortly in 1978–1979, and this was not a success. The new government is formed by the three largest parties in Parliament, including the Moderates, a new party sprinting across the thresholds of declaration, authorisation, representation, and relevance (Pedersen Reference Pedersen1982) within just 1.5 years.

After the election and formation of the Frederiksen II government, the number of ministries was enlarged from 20 to 23. While the parliamentary size of the Social Democrats, Liberals and Moderates is, respectively, 50, 23 and 16 seats, their ministerial split is 11, seven and five, respectively. As usual, the smaller parties acquired a larger share of ministries than seats. However, based on the formal ranking order of the ministries (statsrådsrækkefølgen), the Social Democrats clearly got more high-ranking ministries as their ministries on average rank at 9.3, the Liberals’ at 12.6 and the Moderates’ ministries at 15.2 on a ministerial ranking ranging from 1 (highest ranking minister) to 23 (lowest ranking minister).

Among the Social Democrats, four ministers held on to their portfolios, while seven were given a new ministry. In particular, Nicolai Wammen in the Ministry of Finance and Minister of Justice Peter Hummelgaard are among the most powerful. Liberal Chair Jakob Ellemann-Jensen became Vice-Prime Minister (a non-formal institution) and Minister of Defence. The Social Democrats held on to the powerful Ministry of Finance, but the Liberals got the Ministry of the Economy. Together with the Ministry of the Interior and Health, these are, in everyday government business, heavier than the Defence Ministry.

Moderate Chair Lars Løkke Rasmussen became Minister of Foreign Affairs. Neither he nor the Moderates had emphasised this policy area in the campaign, where Lars Løkke Rasmussen had, in particular, called for reform of the way in which the health sector is organised. However, being Minister of Foreign Affairs is more of a ‘statesman’ position and probably more attractive if health reform is not on the immediate government agenda. The Moderates also acquired the Ministries for Culture, (Higher) Education and Research, Digitalisation, Equality and the Elderly, as well as the Ministry for Climate, Energy and Utilities. Due to the high frequency of travel for the Minister for Foreign Affairs, the Moderates’ ‘number 2’, Minister for Culture Jakob Engel-Schmidt (former Liberal MP), sits in two of the most important government committees (on coordination and the economy). This is uncommon for a Minister of Culture.

There is a tradition of including ministers who are not MPs in Danish governments, such as a mayor, chair of the regional boards or people from businesses or other organisations. In 2022, there are two ministers who are not MPs, both of them representing the Moderates. Minister for Higher Education and Research, Christina Egelund, was formerly an MP for the Liberal Alliance from 2015 to 2019 and the party's parliamentary group chair between 2018 and 2019. Minister for Climate, Energy and Utilities (‘domestic climate minister’), Lars Aagaard, is a former director of ‘Danish Energy’, now called ‘Green Power Denmark’, which is an interest organisation working for the green transition through electrification.

In the government agreement among the three parties, welfare takes up by far the most pages, but other themes included are the economy, climate, defence, cohesion between the rural countryside and urban cities, active and open democracy and the Kingdom of Denmark, that is, the relationship with Greenland and the Faroe Islands. The government has framed itself as a reform-focused government, but part of the welfare reforms is left unspecified in the government agreement; committees will be working to develop these reforms and create agreement on them.

Danish parliamentary affairs are characterised by a high level of consensus with broad support for a large share of the legislation. However, the new government will likely be challenged by opposition from both the right and the left, as well as from within, as ministers from the three parties have to reach agreements and learn to trust each other.

Parliament report

In 2022, prior to the election, the composition of Parliament was affected by both MPs becoming independents, changing parties or forming new parties, and by members leaving Parliament to a much larger extent than usual and with more prominent MPs involved. Yet another (see Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2022) prominent Liberal, former Minister Karsten Lauritzen, left politics on 1 February. Also, Nick Hækkerup left in May (see Cabinet Report). Lars Løkke Rasmussen, who left the Liberals on 1 January 2021, was an independent until 19 May, when he began representing his new party, the Moderates, in Parliament.

The Danish People's Party lost several MPs after the election of Messerschmidt as party chair. Six left and became independents in February and another four in June. Four of the former, and all of the latter, joined the Danish Democrats in August. On 30 June, former party Chair Kristian Thulesen Dahl left the Danish People's Party to become an independent, and on 31 July, he left politics for a civil career as director of the Port of Aalborg.

In addition to two independent MPs from the Danish People's Party, the independents parliamentary group included the two former Conservatives who left due to #metoo cases (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2021, Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2022), a former Liberal Alliance member (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2020a) and Jens Rohde, former MP for the Liberals, Social Liberals and Christian Democrats, who left the latter in August 2022.

The large number of exits, defections and new parties in Parliament since the 2019 election resulted in a markedly changed party system and a record-high number of independents.

These trends continued in the new election period. Within a month of the 1 November election, two further MP changes had taken place. Mette Thiesen, New Right, became an independent on 7 November after her partner was accused of harassment within the party and also at the election night party. On 14 November, Karen Ellemann (Liberals) left Parliament to become Secretary-General to the Nordic Council of Ministers. On 24 November, one of the politically inexperienced members of the Moderates, Kristian Klarskov, stepped out (Folketinget 2023a) due to media coverage indicating that he was not as successful an entrepreneurial businessman as presented during the election campaign (Westersø Reference Westersø2022). All these changes are summed up in Table 5.

Table 5. Party and gender composition of the Parliament (Folketinget) in Denmark in 2022

Note: The table is based on the 175 MPs elected in the mainland Denmark. Parliament also contains four North Atlantic representatives, two MPs from Greenland and two from the Faroe Islands. The former has two female MPs, whereas the latter has a male and a female MP, thus bringing the total number of women to 78 out of 179 MPs (43.6 per cent).

Sources: Danmarks Statistik (2022b); Folketinget (2022); Kosiara-Pedersen (Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2021).

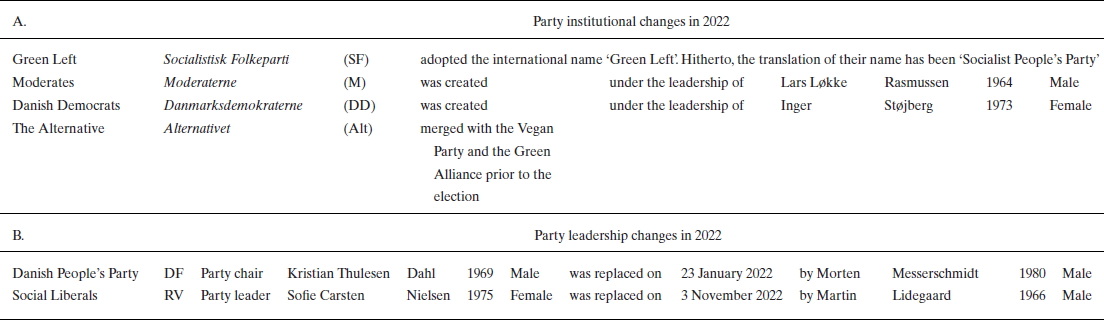

Political party report

Even though the new party the Moderates/Moderaterne (M) created by former Prime Minister and party chair of the Liberals/Venstre (V), Lars Løkke Rasmussen, had collected the required number of signatures by mid-September 2021 (Dreiager Reference Dreiager2021), they waited until 14 March 2022 to be approved and eligible to stand for election. The party was formally founded on 5 June 2022, which is the Danish ‘Constitution Day’ (Grundlovsdag)—a half or full holiday and an important day of celebration, in particular for centre-right parties.

Inger Støjberg, former MP, Minister for Integration and vice-chair of the Liberals left the party in 2021 in light of their support for bringing her to the Rigsret (‘impeachment’), the court dealing with ministers’ illegal administration (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2022). Støjberg was accused and later convicted for the handling of cases concerning the accommodation of married or cohabiting asylum seekers, one of whom was a minor, which had not taken place in accordance with administrative law rules and principles. When sentenced to 60 days of unconditional prison in December 2021, Støjberg left Parliament upon the sentence and served it in her home in the spring of 2022. In June 2022, she formally formed the new party ‘Danish Democrats–Inger Støjberg’ (Danmarksdemokraterne–Inger Støjberg) and broke the record for the fastest collection of voter signatures to become eligible to stand for election. Støjberg gained the support of many former members of the Danish People's Party. Hence, she was able to single-handedly nominate a number of experienced politicians for her party's 2022 election list.

Denmark has seen an emergence of (small) green parties in recent years. As the election came closer, all but one green party decided to collaborate with each other. First, the Vegan Party/Veganerpartiet (VP), which had already become eligible in 2020 (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2021), joined the Greens/De Grønne to form a new party called the Green Alliance/Grøn Alliance on 1 September 2022. The Greens were originally created in 2019 under the name Green Direction–Denmark's Green Liberal Party, but changed its name to the Greens in February 2020. As the Greens were not eligible to stand for election, the Election Committee had to approve the Vegan Party's official name change to Green Alliance. Second, on 4 October 2022, an agreement was reached between the Alternative, Green Alliance and Momentum (which had not collected sufficient signatures to be able to stand for election) on fielding candidates together on the list of the Alternative at the upcoming election (Alternativet 2022).

At their annual meeting on March 20, the Socialist People's Party decided to change its international name to ‘Green Left’ in order to distance themselves from communist and radical left parties, as the party was created in opposition to the communists in 1959 (Ritzau 2022). With the new English appellation of ‘Green Left’, the party shows both that they belong to the left-wing and that they are part of the European Green Party, with whom they sit in the European Parliament.

Turning to changes in party leadership, Table 6 shows that 2022 brought two of these among parties represented in Parliament. The Danish People's Party/Dansk Folkeparti chair, Kristian Thulesen Dahl, stepped down in light of the very poor election results at the municipal and regional elections in November 2021. Dahl had met internal opposition for a while, and dissatisfaction with his leadership became more apparent after those elections. Particularly noticeable is Pia Kjærsgaard's (party founder and former party chair) waning support for Dahl; this indicated a true split among the group of party founders (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen, Munk Christiansen, Elklit and Nedergaard2020b). A new party chair, Messerschmidt, was elected at an extraordinary party congress in January 2022. The Danish People's Party imploded after the election of Messerschmidt, with MPs, members and voters defecting to the New Right and Danish Democrats, among others. In August 2021, the party's Vice-Chair Morten Messerschmidt got a six-month suspended prison sentence due to misuse of EU funding at a party meeting where EU matters were not being discussed and forgery in relation to this. However, in December 2021, the judge was recused from the case due to him liking a Facebook message, which could be interpreted as critical of Messerschmidt, and the case was sent to retrial with a decision of not guilty by 21 December 2022 (Dalsgaard & Hagemann-Nielsen Reference Dahlsgaard and Hagemann-Nielsen2022). By the end of 2022, Messerschmidt was back on track, with parliamentary representation, acquittal and potential influence on government decisions due to the Danish People's Party being part of established agreements with the government on certain policy areas (forlig).

Table 6. Changes in political parties in Denmark in 2022

Last, following a poor election result, Sofie Carsten Nielsen stepped down as leader of the Social Liberals. The parliamentary group decided on 3 November to replace her with Martin Lidegaard.

Institutional change report

No changes to the constitution, basic institutional framework, electoral law or other major changes to the rules of the game occurred in 2022.

Issues in national politics

The aftermath of COVID-19 played a role in Danish politics. The report from the Mink Commission, which investigated the process around illegal orders to cull minks in light of COVID-19 contamination risks (see Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2021), was published on 30 June (Minkkommissionen 2022) and caused the Social Liberals to call for an election to end the one-party Social Democratic government.

Another ‘scandal’ taking up a lot of room in 2022 was the ‘Defence Intelligence Service scandal’ (FE-sagen). Defence Minister Trine Bramsen temporarily dismissed several high-ranking officials within the Danish Defence Intelligence Service (FE) in 2020 due to critique from the parliamentary control committee. In December 2021, four high-ranking officials were accused of sharing classified information. One of these was the chief of FE, Lars Findsen, who spent 70 days in prison (custody). In September 2022, charges were filed against Findsen for divulging secrets of importance to state security. In the midst of the election campaign, he published a book containing a harsh critique of the government's handling of this case. While the centre-right opposition tried to put these scandals on top of the electorate's agenda during the campaign, they seemed to have already harmed the Social Democrats and did not have an effect on the voters at that time.

Defence and security were, due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, more markedly on the agenda than in previous years. The government assembled a broad coalition of parties in March to increase public spending on defence to 2 per cent of Denmark's GDP and to call a referendum on Denmark's opt-out of EU defence on 1 June 2022. Defence was also on the agenda in the election campaign, something which is rarely seen. While the economy is a constant issue on the political agenda, fighting, and mitigating the effects of, inflation became an important issue after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Policies were passed to help those who are the worst off (e.g., pensioners and families with small children) and those hit by high energy prices.

In sum, the not-so-normal COVID-19 years of 2020–2021 were followed by yet another year of challenges. However, the response has been renewed with new, major parties formed and a completely new type of Danish government.