Introduction

Studies spanning the latest Quaternary highlight the importance of well-dated, chronologically constrained lake deposits as valuable records of global and regional climate and environmental change (Cohen 2003; Bradley Reference Bradley2015). Radiocarbon dating provides the chronological framework essential for understanding the timing and nature of variations in late Quaternary climate and environment. High-resolution analysis of a lake sediment core, recovered from Deoria Tal, Uttarakhand, India, using non-destructive imaging such as X-ray fluorescence, X-ray, and CT scans was undertaken to characterize long term and abrupt climatic fluctuations in northern India during the mid-to-late Holocene (Niederman et al. Reference Niederman, Porinchu and Kotlia2021). Eleven AMS 14C dates, obtained on Trapa seeds, provided the means to develop a robust chronology for the site and identify of the timing and duration of notable drought episodes during the last five millennia.

Radiocarbon dating of organic matter extracted from lake sediment, such as bulk sediment, macrofossils, and plant remains plays a pivotal role in developing the age depth models that are necessary for quantifying past rates of change, which help inform predictions of future changes in climate and ecosystems. However, the complexity of lake sediment, which contains organic carbon sourced from terrestrial and limnic material presents challenges that require careful methodological consideration. For instance, bulk sediment includes both allochthonous and autochthonous materials and the remains of plants and animals, including algae, bacteria, fungi, potentially bound to older organic material, all of which may having differing concentrations of 14C (Bjork and Wohlfarth Reference Bjork and Wohlfarth2001). Thus, a multi-proxy approach, utilizing various dating materials and methods, is often necessary to achieve reliable chronological frameworks in aquatic environments (Bradley Reference Bradley2015).

The incorporation of terrestrially sourced soil organic matter or re-worked material into lake sediment, by the various natural and anthropogenic processes occurring within lake catchments, often described as the “old” carbon effect, can result in anomalously old dates (Moreton et al. Reference Moreton, Rosqvist, Davies and Bentley2004; Wade et al. Reference Wade, Richter, Cherkinsky, Craft and Heine2020). It is essential to consider the implications of sediment mixing and post-depositional processes. Bioturbation, the initiation of agriculture and natural erosion can affect the stratigraphy and consequently the radiocarbon dates (Appleby Reference Appleby2001). These processes can introduce older or younger carbon into different sediment layers, leading to inaccuracies in dating. In addition, the existence of a lake reservoir effect, typically associated with hard water lakes characterized by high amounts of dissolved calcium carbonate, can also result in systematically old dates that differ by thousands of years from the actual age of sediments (Deveey et al. Reference Deevey, Gross, Hutchinson and Kraybill1954; Olsson Reference Olsson1986). The suitability of different aquatic plant macrofossils for radiocarbon dating varies significantly based on their interaction with dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC). Submerged aquatic plants, which utilize large amounts of DIC within the lake, often suffer from old-carbon effect, rendering them unsuitable for radiocarbon dating (Marty and Myrbo Reference Marty and Myrbo2014). Emergent plants, on the other hand, can sometimes metabolize DIC in sufficient quantities to affect dating accuracy under certain environmental conditions, further complicating the radiocarbon dating process (Marty and Myrbo Reference Marty and Myrbo2014). Factors such as natural and anthropogenic-related changes in vegetation cover and the distribution of carbonate around lakes must also be carefully considered when selecting material for radiocarbon dating (Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Chui, Yang, Cheng, Chen, Ming, Hu, Li and Lu2021).

Numerous studies have identified the advantages and disadvantages associated with using different types of datable material and in doing so, have highlighted the need for the careful selection of the material ultimately used for the development of radiocarbon chronologies (Bjork and Wohlfarth Reference Bjork and Wohlfarth2001). The uncertainties related to the 14C dating of bulk sediments in lacustrine environments has prompted researchers to focus, when possible, on using macrofossil material derived from plants/animals that rely on atmospheric CO2 for carbon fixation (Törnqvist et al Reference Törnqvist, De Jong, Oosterbaan and Van Der Borg1992). However, a deficit of terrestrial and/ or aquatic macrophytes often characterizes lakes located at high latitudes (above latitudinal treeline) or high elevation (above timberline). Dating the remains of short lived insect, particularly the head capsules of chironomids, in situations where terrestrial and aquatic plant macrofossils are absent, provide researchers with an alternative to using bulk sediments to establish a radiocarbon chronology (Fallu et al. Reference Fallu, Pienitz, Walker and Overpeck2004; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Battarbee and Hedges1993). Chironomids are recognized as valuable proxies for reconstructing past environmental conditions in lake sediments (Walker Reference Walker2001). Chironomids are ubiquitous and highly sensitive to changes in water temperature, pH, oxygen levels, and other environmental variables (Porinchu and MacDonald Reference Porinchu and MacDonald2003). Their remains, primarily composed of chitin and proteins, are well preserved in lake sediments, and are not significantly altered by decomposition processes, making them reliable indicators for paleoenvironmental reconstructions (Heiri et al. Reference Heiri, Schilder and van Hardenbroek2012).

The interaction between different carbon sources and their impact on radiocarbon dating results is a critical area of study. The differences in the carbon sources in chironomid capsules, bulk sediment, and Trapa seeds can significantly affect the accuracy of radiocarbon dates. Understanding these interactions and their implications for dating accuracy is essential for reconstructing the timing of past climate and environmental change accurately. This paper has three main objectives: 1) establish three independent age-depth models based on paired radiocarbon dates obtained on aquatic macrophytes (Trapa seeds), insect remains (chironomid capsules) and bulk sediment, respectively; 2) characterize the discrepancies observed between the dates obtained on plant and insect matter and bulk sediment samples; and 3) assess whether the discrepancies in the radiocarbon dates are systematic and can be used to improve our understanding of climate and environmental change in the Garhwal Himalaya during the mid-to late Holocene.

Study area and site

Deoria Tal is a mid-elevation lake (2483 m a.s.l) located in the Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary, in the Garhwal Himalaya, Uttarakhand India (Figure 1). This wildlife sanctuary is regulated under the Wildlife Protection Act 1972, and all permits for this research have been obtained. The Garhwal Himalaya is renowned for it’s unique ecological and climatic conditions, which are influenced by a combination of high relief, topographic variability, and steep climatic gradients (Bhatt and Sachdeva Reference Bhatt and Sachdeva2014). The site, Deoria Tal, is located in the Lesser Garhwal Himalaya, which consists of diverse rock formations that are notably heterogeneous and extensively fractured. This region is bounded by the North Almora Thrust (NAT) and Main Central Thrust (MCT), with evidence of neo-tectonism documented regionally by the existence of large fans and cones of landslide debris (Chaudhary et al. Reference Chaudhary, Gupta and Sundriyal2010; Islam et al. Reference Islam, Chattoraj and Champati2014). According to Joshi and Kotlia (Reference Joshi and Kotlia2015) tectonically formed lakes are present throughout this region. The formation of Deoria Tal is likely a response to the neo-tectonic activity that is documented locally (Chaudhary et al. Reference Chaudhary, Gupta and Sundriyal2010). The bedrock geology and soil composition within the catchment influence the nature of the sediment flux and the geochemical properties of the lake sediment. Deoria Tal is located just to the south of the Bhulkund Thrust in a zone that is characterized by porphyritic gneiss with mica schist and granite also present (Bist and Sinha Reference Bist and Sinha1980). The soil surrounding Deoria Tal is greyish brown, dominated by very fine sand, with lesser amounts of coarse sand and pebbles, with a mean soil water holding capacity of ∼16% and a hue, value, chroma of 10Y/5/2, respectively (Bahuguna et al. Reference Bahuguna, Gairola, Semwal, Uniyal and Bhatt2012). The Munsell soil chart comparison was not used in the field.

Figure 1. Study area map showing Uttarakhand, India, with Deoria Tal highlighted as the research site. The main map (A) provides national context, including major cities (Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata). The inset map (B) details the state’s geography, marking Dehradun and the study site, Deoria Tal. A photograph of Deoria Tal (C) taken March 24, 2018.

Deoria Tal experiences a temperate montane climate with distinctive rainy, winter, and summer seasons. Annual temperature ranges from 15ºC to 25ºC but can drop below 0ºC in winter. The lake freezes over in January and February, while snowfall is rare on lower slopes. The region receives an average annual rainfall of approximately 2000 mm, primarily from the Indian Summer Monsoon (ISM) (Sharma et al. Reference Sharma, Chauhan and Rajagopalan2000). ISM-related rainfall falls between June and September (Goswami and Chakravorty Reference Goswami and Chakravorty2017) and typically ranges between 8 and 10 mm/day (Paatwardhan et al. Reference Patwardhan, Kulkarni and Sabade2016).

Deoria Tal is surrounded by temperate forest consisting of oak, alder, elm, horse chestnut, maple and apple with srubs and thick cover of grasses. (Sharma et al. Reference Sharma, Chauhan and Rajagopalan2000). There is an extensive mat of water chestnut (Trapa), a floating leaved aquatic macrophyte, in the littoral zone of the lake (Niederman et al. Reference Niederman, Porinchu and Kotlia2021). Trapa bispinosa, the Trapa sp. present in Deoria Tal, is native to northern India (Adkar et al. Reference Adkar, Dongare, Ambavade and Bhaskar2014). Pollen analysis indicates that Trapa has been present in Deoria Tal for at least 5000 years. The terrestrial and aquatic vegetation present at Deoria Tal contributes allochthonous and autochthonous sourced organic matter to the lake, the flux of which is crucial to understanding and interpreting radiocarbon dates obtained on various materials. Temporal variations in the relative abundance of plant species and the composition of the vegetation community, established using pollen analysis and sediment geochemistry, offer valuable insights into past regional climate and local ecological changes.

The closed basin configuration of the lake is significant for paleoenvironmental studies, as it minimizes external hydrological influences and allows for the accumulation and preservation of sedimentary records that reflect local environmental changes (Sharma et al. Reference Sharma, Chauhan and Rajagopalan2000; see Supplemental Figure 1 for high-resolution DEM). The balance between precipitation, runoff and evaporation influences water levels and sediment deposition patterns (Manish and Pandit Reference Manish and Pandit2018). Deoria Tal’s relatively pristine condition, limited anthropogenic influence, and well-preserved sedimentary records make it an important site for paleoenvironmental and paleoclimatic research (Niederman et al. Reference Niederman, Porinchu and Kotlia2021; Sharma et al. Reference Sharma, Chauhan and Rajagopalan2000).

Materials and methods

A sediment core was extracted from Deoria Tal (30.5222ºN, 79.1277ºE) in May 2018 using a modified Livingstone core fitted with a 2” diameter stainless steel barrel, deployed from a platform anchored at a depth of 5.65 m. The core comprises five overlapping sections, resulting in a total composite core length of 380 cm. The flocculent surface sediment was collected with a plastic tube and sectioned in the field at 0.25 cm intervals to ensure minimal disturbance. The stiffer sediment found lower in the profile was retrieved using a stainless-steel barrel, kept intact, wrapped in plastic wrap and foil, returned to the laboratory, and stored at 4ºC.

AMS radiocarbon dating was conducted at the Center for Applied Isotope Studies (CAIS), University of Georgia for three types of samples: bulk sediment, Trapa seeds and chironomid capsules. A minimum of 2000 chironomid head capsules were isolated for each paired sample following the methods of Walker (Reference Walker2001). To extract chironomids, 1 ml of wet lake sediment was heated at temperature at 80ºC in a 10% KOH solution for 30 min to disaggregate the sediment. The sediment sample was sieved through a 95 mm mesh. Material retained by the sieve was rinsed, poured into a Bogorov counting tray and sorted under a stereomicroscope at 40× magnification. Chironomid capsules were picked using fine tweezers and transferred to a glass vial filled with Milli-Q water. The mass of carbon obtained from the chironomid capsules used for dating varied between 62 and 154 μg. Stable isotope ratios of 13C/12C were measured using a Elemental Analyser Flash 2000 coupled with Thermo Delta V Advantage isotope ratio mass spectrometer and expressed as δ13C relative to PDB, with an error of less than 0.2 ‰.

All bulk sediment samples were pretreated with 1N HCl at 80ºC for 1 hr to remove carbonate and other contaminants. Following acid treatment, the samples were thoroughly rinsed with Milli-Q water to eliminate residual acid and contaminants. The chironomid capsules and Trapa seeds samples were also pretreated using the acid-base-acid (ABA) pretreatment protocol (Olsson Reference Olsson1986). The pretreated samples were then dried at 105°C to prepare them for combustion. For AMS analysis, the pretreated samples were combusted at 900°C in evacuated/sealed ampoules in the presence of CuO. This process converts the organic carbon in the samples into CO2, which was converted into graphite and 14C/13C ratio were measured using AMS (Cherkinsky et al Reference Cherkinsky, Prasad and Dvoracek2013). Chronological control of the sediment sequence, first reported in Niederman et al. (Reference Niederman, Porinchu and Kotlia2021), is based on 11 calibrated AMS radiocarbon dates obtained on Trapa seeds extracted from the sediment core (Table 1). The radiocarbon dates were converted to calendar years using OxCal 4.4 with the reported 2σ age ranges based on IntCal13 following Reimer et al. (Reference Reimer, Bard and Bayliss2013). The published age-depth model was developed using Bchron package, an open-source R code package used for developing chronologies (Haslett and Parnell Reference Haslett and Parnell2008). The modeled median age-depth curve was selected to convert specific depths to cal BP.

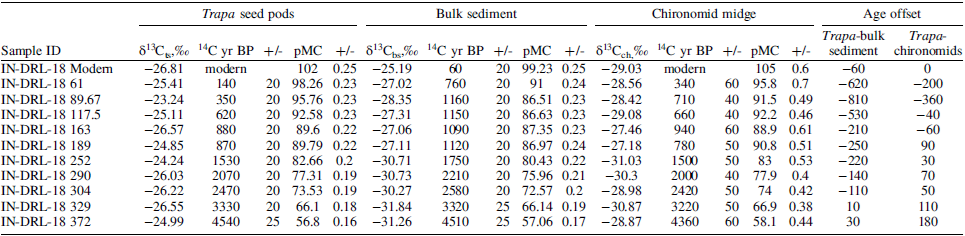

Table 1. Offset between the 14C dates obtained on the Trapa seed pods, bulk sediment, and chironomid remains.

A total of 194 bulk sediment samples were prepared for geochemical analyses of %C, %N and C/N. Samples (0.5 cm3 each) were analyzed at ∼2.0 cm resolution from 74 cm to 300 cm and 0.50 cm resolution from 300 cm to 380 cm. Samples were placed in crucibles and dried in an oven at 40°C for 48 hr to ensure evaporation of any water and homogenized using a ball mill. The homogenized samples were placed into plastic, labeled vials and freeze-dried for a minimum of 24 hr. Approximately 10–15 mg of freeze-dried sediment from each sample was weighed using a microbalance and placed into silver capsules. The quantitative measures of %C and %N derived from the bulk sediment samples were determined using a Thermo© Flash 1000 elemental analyzer at the CAIS at UGA.

Results

Stratigraphy

The 380 cm core was recovered through four separate, adjacent drives (LC1-LC4) (see Supplemental Figure 2 for core stratigraphy). LC1 (340–380 cm) was characterized by dark brown, almost black sediment at 380 cm, lightening to light brown sediment with a strong presence of organics at 350 cm, shifting to brown, organic sediment between 347 and 320 cm. LC2 (250–242 cm) consisted of dark brown, organic sediment. LC3 (165–257 cm) is composed primarily of dark brown, organic sediment with a lighter brown, clay layer found between 248 and 204 cm. LC4 (70–170 cm) consisted of dark brown, organic sediment between with abundant aquatic moss present between 170 and 122 cm. At 122 cm the color grades to light brown, less organic sediment. The uppermost sediment (0-84 cm), which was extracted using a plastic tube (PT) and sectioned at 0.50 cm intervals in the field, consisted of brown gyttja. Additional detail regarding core recovery is found in Niederman et al. (Reference Niederman, Porinchu and Kotlia2021).

Trapa seeds

The radiocarbon dates obtained on the Trapa seeds were in stratigraphic order, with a statistically insignificant age reversal between 163 and 189 cm (Supplementary Table 1; Neiderman et al. Reference Niederman, Porinchu and Kotlia2021). The date obtained on the living seed recovered from the lake in 2018 had a pMC equal to 101.99 (Table 1), suggesting that the Trapa seed pods have not been affected by old carbon or a reservoir effect and that they can be used to develop a robust chronology for the core. The basal sample at 372 cm provided a radiocarbon date of 4540 14C yr BP. The age-depth model developed in Bchron (Supplementary Figure 3) indicates that the base of the core (380 cm) extends to ∼5200 cal BP. A notable change in the sedimentation rate occurs at 1500 cal BP. The rate of sedimentation nearly doubles from ∼0.06 cm/yr at 1600 cal BP to 0.10 cm/yr at 1500 cal BP. The increase in sedimentation at 1500 cal BP is even more apparent when placed in a broader temporal context: it increases from ∼ 0.03 cm/yr between the base of the core and 1500 cal BP to 0.18 cm/yr from 1500 cal BP to the present (Niederman et al. Reference Niederman, Porinchu and Kotlia2021).

Bulk sediment

The radiocarbon dates obtained on the bulk sediment samples were stratigraphically ordered at the base and top of the sediment profile, with statistically indistinguishable dates found between 89 and 189 cm (Supplementary Table 2). The basal bulk sediment sample at 372 cm provided a radiocarbon date of 4510 14C yr BP. The age-depth model developed in Bchron (Supplementary Figure 4) indicates that the base of the core (380 cm) extends to ∼5300 cal BP. Three distinct intervals of sedimentation can be identified in the age-depth model. The sedimentation rate was ∼0.03 cm/yr between the 1750 cal BP and 5310 cal BP, 0.24 cm/yr between ∼1180 cal BP and 1750 cal BP and ∼0.1 cm/yr between modern and ∼1180 cal BP. The error associated with the determination pMC for the bulk sediment samples is similar to the pMC error determined for the Trapa seeds (Table 1).

Chironomids capsules

The radiocarbon dates obtained on the chironomid samples were stratigraphically ordered at the base and top of the sediment profile, with age reversals found between 89 and 189 cm (Supplementary Table 3), similarly to the bulk sediment results. The age-depth model developed in Bchron (Supplementary Figure 5) indicates that the base of the core (380 cm) extends to ∼5200 cal BP. The sedimentation rate from ∼1420 to ∼5007 cal BP was 0.03 cm/yr. The sedimentation rate increased six-fold between ∼645 to ∼1420 cal BP to 0.17 cm/yr and further increased to 0.18 cm/yr from ∼645 cal BP to the present. The error associated with the determination pMC for the chironomid head capsule samples is approximately double the magnitude of the pMC error determined for the Trapa seed and sediment samples (Table 1).

Inter-sample comparison

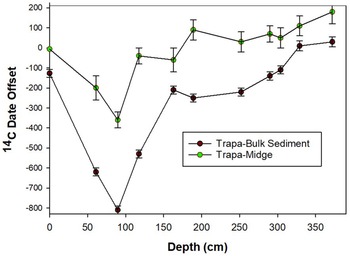

The magnitude of the offset between the measured 14C dates for the bulk sediment and the Trapa seed is characterized by a multi-step increase from the base of the core to present (Figure 2). The dates obtained on the two oldest Trapa and sediment samples were statistically indistinguishable, resulting in a negligible offset between the dates obtained on the Trapa samples and bulk sediment. From the base upwards, the offset increases to 100 years at 300 cm and then doubles to 200 years at 252 cm. The offset remains at ∼200 years until 163 cm. The offset peaks at 800-years at ∼90 cm. The magnitude of the offset between the Trapa seeds and bulk sediment is reduced to ∼100 years at the surface of the core. The bulk sediment samples are consistently older than the Trapa samples (Figure 2).The magnitude of the offset between the measured 14C dates obtained on the chironomid capsules and the Trapa seeds is muted relative to magnitude of the offset observed for the paired dates obtained on the bulk sediment and the Trapa seeds, with the chironomid samples providing younger dates than the Trapa samples between 380 cm and ∼163 cm. The offset between the measured 14C dates obtained on the chironomid capsules and the Trapa seeds, which increases to 360 years at 90 cm, is negligible at the surface. The offset between the Trapa and chironomid remains only exceeds 200 years for one sample at 90 cm, with the chironomid sample 360 years older than the corresponding Trapa seed pod. The chironomid dates transition from being younger to older than the Trapa samples between 189 cm and 163 cm.

Figure 2. Age offset plotted against depth (cm) for the difference between the 14C dates obtained on Trapa seed pods and bulk sediment (red) and chironomid remains (green), respectively.

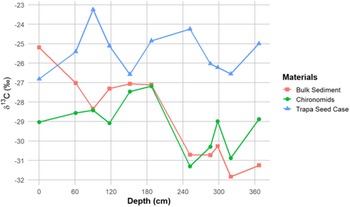

The δ13C of the Trapa seed pods (δ13CTS) varied between –23.24‰ and –26.81‰ (range = 3.57‰; mean = –25.46‰; standard deviation = 1.11‰). The δ13C of the 11 paired chironomid samples (δ13CCH) varied between –31.08‰ and –27.18‰ (range = 3.39‰; mean = –29.07‰; standard deviation = 1.24‰). The δ13C of the 11 paired bulk sediment samples (δ13CBS) varied between –31.84‰ and –25.19‰ (range = 6.65‰; mean = –28.81‰; standard deviation = 2.22‰) (Figure 3). The C/N values for the 194 bulk sediment samples varied between 16.3 and 10.2 (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Variations in δ13C values of the paired bulk sediment, chironomid, and Trapa seed case samples with depth.

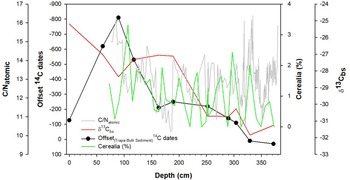

Figure 4. Variations in C/N (gray line), δ13C values of the paired bulk sediment samples (red line), percentage of Cerealia pollen (green line) and the offset between the 14C dates obtained on Trapa seed pods and bulk sediment (black) during the past 5300 cal BP (380 cm).

Discussion

The observed differences between the radiocarbon dates derived from chironomid capsules, Trapa seeds, and bulk sediment (Figure 2) underscores the inherent complexities and challenges in developing robust chronologies using bulk sediment. Bulk sediment integrates a mixture of autochthonous and allochthonous sources over different time scales, making it susceptible to contamination from older carbon from terrestrial or reworked material, often leading to an overestimation of the radiocarbon age (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Battarbee and Hedges1993; Fritz Reference Fritz2008). The allochthonous flux of organic carbon to lakes, particularly in arctic and alpine settings, often consists of different soil horizons which may contain very old carbon due to the slow rates of decomposition of organic matter that occur in these environments (Strunk et al. Reference Strunk, Olsen, Sanei, Rudra and Larsen2020). The C:N ratio can be used to determine whether the OM in lacustrine sediment is derived terrestrial or aquatic sources (Meyers and Teranes Reference Meyers and Teranes2001). C:N is known to increase significantly following forest clearance and other disturbances in the catchment such as fire (Dunnette et al. Reference Dunnette, Higuera, McLauchlan, Derr, Briles and Keefe2014; Kaushal and Binford Reference Kaushal and Binford1999; Morris et al. Reference Morris, McLauchlan and Higuera2015). Variations in the δ13C values can indicate changes in vegetation, primary productivity, and carbon sources in an ecosystem (Griffiths Reference Griffiths1998; Meyers Reference Meyers1994). For bulk sediment, depleted δ13C values may indicate a typical proportion of terrestrial C3 plants within the lake catchment or organic matter derived from aquatic sources (Lamb et al. Reference Lamb, Wilson and Leng2006; Meyers Reference Meyers1994).

The 3.5‰ enrichment in the δ13Cbs that occurs between 252 cm (1450 cal BP) and and 117.5 cm (∼580 cal BP) is notable. The large shift in δ13Cbs values at ∼1450 cal BP may reflect land use changes, such as deforestation and/or an increase in agricultural intensity in the Deoria Tal catchment. Pollen analysis of the Deoria Tal core reveals that the interval between 249 cm (1425 cal BP) and 107 cm (515 cal BP) is characterized by a nearly eight-fold increase in the relative abundance of grass and cereal pollen (Figure 4). The cereal pollen likely represents an increase in the cultivation of crops, including millet and cereals such as sorghum, in the lake’s catchment. The clearance of land for agriculture, which would increase the flux of terrestrial organic matter into the lake system, is supported by the notable increase in C/N between 190 cm (∼900 cal BP), when the C/N value is at its minimum value, and 100 cm (∼500 cal BP) (Lamb et al. Reference Lamb, Wilson and Leng2006; Meyers Reference Meyers1994). This inference is supported by the δ¹3C values of chironomid remains, which are characterized by one episode of notable enrichment, which occurs between 252 cm (∼1500 cal BP) and 189 cm (∼900 cal BP), when the δ¹³C is enriched 3.85‰. This enrichment likely reflects the incorporation by chironomid, through diet, of isotopically enriched detrital matter, originating from the catchment and associated with the intensification of agricultural activities at ∼1500 cal BP.

The highly variable C/N values that characterize the core between 380 cm (∼5300 cal BP) and 250 cm (1500 cal BP) correspond to an interval of relatively low values of cultural plant pollen (0-2%). The increase in the offset between the bulk sediment and the Trapa seed pod dates begins at ∼800 cal BP (163 cm), when it is ∼ 200 years, and peaks at ∼400 cal BP (89 cm), when the offset reaches ∼800 years. The four-fold increase in the offset between the bulk sediment and the Trapa seed pod dates is coincident with an eight-fold increase in the relative abundance of cultural pollen and grasses and a large increase in C/N that occurs between 185 cm (∼900 cal BP) and 85 cm (∼380 cal BP). The offset in the 14C dates for the chironomid remains transition to a negative value (the date obtained on the chironomid is older than the date obtained on the Trapa) between 117.5 cm (∼580 cal BP) and 89 cm (400 cal BP). This interval is characterized by the highest values of % Cerealia and C/N, likely reflecting peak agricultural activity in the lake catchment. Increased agricultural activity would result in an elevated flux of soil OC, which contains a higher proportion of old carbon, to the lake. This material, which would be incorporated by the chironomids as they fed on detrital matter, could account for why the dates obtained on the chironomids are older than those obtained on the Trapa between 800 cal BP and present. The timing of this increasing offset closely aligns with the timing of the increase grass and cereal pollen and C/N (Figure 4) presented here and with existing palaeoecological evidence of intensified agricultural activity and human-induced environmental changes in the region (Sharma and Gupta Reference Sharma and Gupta1997; Sharma et al. Reference Sharma, Chauhan and Rajagopalan2000; Quamar and Kar Reference Quamar and Kar2022). There is limited evidence documenting the timing of the intensification of human activity in the Garhwal Himalaya. However, the existing records suggest the presence of increased grass pollen and charcoal fragments around 3000 BP, associated with the Painted Grey Ware culture, indicates land clearance and cultivation practices that further impacted the sedimentation process (Niederman et al. Reference Niederman, Porinchu and Kotlia2021; Sharma et al. Reference Sharma, Chauhan and Rajagopalan2000). These findings underscore the importance of considering human activity and its impact on sediment composition and radiocarbon dating.

The δ13C values of aquatic insects like chironomids and aquatic plants like Trapa are influenced by the isotopic composition of the dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) in the water and the carbon sources available to them (Walker Reference Walker2001; Ficken et al. Reference Ficken, Li, Swain and Eglinton2000). The δ¹³C values of the chironomid remains range from –27.18 ‰ to –31.03‰ to, with a variation of approximately 3.4‰ per mil. Chironomid larvae feed on both autochthonous and allochthonous carbon sources, with their grazing behavior varying seasonally (Dvorak et al. Reference Dvorak, Dittmann and Pedrini-Martha2023; Grey et al. Reference Grey, Jones and Sleep2001). Species feeding on detritus often exhibit more negative δ¹³C values due to the accumulation of sedimentary carbon in their diet, whereas species that rely more on algae or phytoplankton show less depleted δ¹³C values. Cummins and Klug (Reference Cummins and Klug1979) note that chironomids occupy various trophic levels, ranging from primary consumers to predators, contributing to their δ¹³C heterogeneity. The δ13C values of Trapa seeds vary between –23.24‰ and –26.81‰. Trapa seed pods typically have δ13C values that reflect the photosynthetic pathways used by C3 plants. The range and standard deviation of the δ13C obtained on the Trapa seed pods and chironomid remains are similar, suggesting that both organisms are primarily incorporating C from the aquatic sources. The relatively stable δ13C values suggest stable growing conditions and consistent photosynthetic activity over the sedimentation period (Ficken et al. Reference Ficken, Li, Swain and Eglinton2000; O’Leary Reference O’Leary1988).

This study highlights the complexities of interpreting radiocarbon dates from bulk sediment due to the integration of multiple carbon sources and potential contamination from older carbon inputs. To improve the reliability of radiocarbon dating in lake sediments, future research should focus on refining pretreatment protocols and selecting more specific organic components, such as identifiable macrofossils or individual aquatic organisms such as chironomids, to minimize the influence of allochthonous inputs (Olsson Reference Olsson1986; Strunk et al. Reference Strunk, Olsen, Sanei, Rudra and Larsen2020). Advances in instrumentation, will reduce the sample mass required for dating by an order of magnitude, enabling the use of ultra-small samples, making the direct dating of chironomid microfossils feasible. Additionally, refining the use of alternative proxies analyzed in lacustrine sediments, such as pollen, diatoms, and geochemical data, can provide a more comprehensive understanding of past environmental conditions.

Conclusion

The findings of this study underscore the importance of selecting appropriate materials for radiocarbon dating in lake sediment studies. Chironomid head capsules and Trapa seed pods provide reliable and precise chronological markers, offering valuable insights into past environmental conditions in Deoria Tal. The δ13C values of radiocarbon dated materials reveal distinct trends in the source of organic matter through time at Deoria Tal. Anthropogenic activity within the Deoria Tal catchment is evidenced by the increasingly enriched values of δ13Cbs that begins at ∼1500 cal BP (252 cm). These data, in conjunction with pollen estimations, provide a detailed chronology of environmental changes in the Garhwal Himalaya, particularly during periods of significant ecological and climatic transitions, which occurred between 1500 and 400 cal BP. The results also highlight the need for careful consideration of carbon sources and potential contamination in radiocarbon dating and the benefits of using multiple proxies for comprehensive paleoenvironmental reconstructions. Future research should aim to refine dating techniques and expand the range of proxies analyzed to improve the understanding of historical climate and ecological changes. By addressing these challenges, researchers can enhance the accuracy and reliability of radiocarbon dating, providing more detailed and accurate reconstructions of past environmental and climatic conditions.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2025.10174

Acknowledgments

A National Science Foundation Human-Environment and Geographical Sciences Award (HEGS-2026311) to DFP and AC, a U.S. Fulbright-Nehru Fellowship to DFP and a Global Collaborative Research Grant from UGA to DFP supported this research.