1. Introduction

The Himalayan region hosts abundant glacial lakes (Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Yao, Xie, Wang and Yang2015; Maharjan and others, Reference Maharjan2018), most of which are expanding due to the accelerated glacier melt induced by global climate change (Nie and others, Reference Nie2017; Dimri and others, Reference Dimri2021). These include supraglacial lakes located on glacier surfaces, proglacial lakes in the frontal region of the glacier, and periglacial lakes that are not directly connected to the glacier but are influenced by glacial ice (Otto, Reference Otto, Heckmann and Morche2019). The dynamic nature of these glacial lakes is evident in their formation, expansion, disappearance and occasional glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs; Mertes and others, Reference Mertes, Thompson, Booth, Gulley and Benn2017; Nie and others, Reference Nie2017). Each type of lake undergoes characteristic developmental stages influenced by various geological and climatic factors. For instance, supraglacial lakes can drain rapidly through englacial channels, while proglacial lakes are more likely to persist longer and grow as glaciers retreat. Such processes make the dynamics of glacial lakes spatially and temporally heterogeneous. However, one consistent pattern across High Mountain Asia is that there has been a notable increase in the number, volume, and surface area of glacial lakes. Moreover, the expansion rate has accelerated over recent decades (Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Yao, Xie, Wang and Yang2015; Nie and others, Reference Nie, Liu, Wang, Zhang, Sheng and Liu2018). These lakes often release water catastrophically, leading to GLOFs (Zheng and others, Reference Zheng2021a). GLOFs can be triggered by external mechanisms, including high precipitation events, mass wasting in their catchments, ice calving, seismic activities, self-destructive processes such as ice-cored moraine degradation or a combination of events (Harrison and others, Reference Harrison2018).

Multiple GLOF events have been reported across the Himalayan region (Carrivick and Tweed, Reference Carrivick and Tweed2016; Majeed and others, Reference Majeed2021). It is reported that 47% of these events originated from moraine-dammed glacial lakes (Shrestha and others, Reference Shrestha2023). In light of the warming temperatures and rapid glacier retreat, projections indicate a threefold increase in GLOF risk by the end of the century (Khadka and others, Reference Khadka, Zhang and Thakuri2018; Zheng and others, Reference Zheng2021a). GLOFs thus pose increasing threats to downstream communities and the physical environment. These outburst floods can destroy infrastructure, including roads, residential buildings, agricultural lands and hydropower projects, and affect ecosystem services (Nie and others, Reference Nie2023; Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Wang, An and Wei2023c). A notable example is the GLOF event of 2023 at South Lhonak Lake in Sikkim, which caused 178 fatalities and extensive damage to infrastructure, including three hydropower projects (Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Wang and An2024c). Several GLOF events have also sporadically impacted the other parts of the Hindu Kush–Karakoram–Himalaya primarily due to the degradation of ice-dammed lakes (Bhambri and others, Reference Bhambri, Hewitt, Kawishwar and Pratap2017; Yin and others, Reference Yin, Zeng, Zhang, Huai and Wang2019). Similarly, the neighbouring Tibetan plateau has a history of GLOF events (Nie and others, Reference Nie, Liu, Wang, Zhang, Sheng and Liu2018; Allen and others, Reference Allen, Zhang, Wang, Yao and Bolch2019). More recently, a GLOF triggered by a rockfall in Langmale Lake in Barun Valley, Nepal, damaged infrastructure and agricultural fields (Byers and others, Reference Byers, Rounce, Shugar, Lala, Byers and Regmi2019; Sattar and others, Reference Sattar, Haritashya, Kargel, Leonard, Shugar and Chase2021b). These events have, at times, extended their impacts far beyond national borders. For instance, the 2016 GLOF event at Gongbatongsha Lake in the Poiqu Basin, Eastern Himalaya, triggered a transboundary flood and debris flow, causing extensive downstream damage (Sattar and others, Reference Sattar, Haritashya, Kargel and Karki2022). Besides immediate destruction, GLOFs can also lead to long-term environmental impacts, such as soil erosion, sediment deposition, and changes in river morphology, which can further affect agriculture and alter habitat and local ecosystems (Tomczyk and others, Reference Tomczyk, Ewertowski and Carrivick2020; Shugar and others, Reference Shugar2021; Dahlquist and West, Reference Dahlquist and West2022). These occurrences underscore the potential danger posed by the glacial lakes in mountainous regions, necessitating a timely and updated assessment of GLOF susceptibility.

Remote sensing technology, combined with multi-criteria decision-making approaches, has proven effective for continuous monitoring and timely detection of GLOFs in inaccessible mountainous regions (Huggel and others, Reference Huggel, Kääb, Haeberli, Teysseire and Paul2002; Quincey and others, Reference Quincey2007; Wangchuk and others, Reference Wangchuk, Bolch and Robson2022). Medium- and high-resolution satellite data like Landsat, Sentinel, and Planet image collections analysed in geographic information systems (GIS) provide critical data on glacial lake size and dynamics, which are essential for assessing GLOF risk (Kapitsa and others, Reference Kapitsa, Shahgedanova, Machguth, Severskiy and Medeu2017; Qayyum and others, Reference Qayyum, Ghuffar, Ahmad, Yousaf and Shahid2020; Wangchuk and Bolch, Reference Wangchuk and Bolch2020). Various approaches have been employed to assess potentially dangerous glacial lakes in the Himalaya (Rounce and others, Reference Rounce, McKinney, Lala, Byers and Watson2016; Prakash and Nagarajan, Reference Prakash and Nagarajan2017). Often these approaches, utilizing diverse data related to climate, geomorphology, and seismicity, have been adopted from various studies (e.g. Huggel and others, Reference Huggel, Haeberli, Kääb, Bieri and Richardson2004; McKillop and Clague, Reference McKillop and Clague2007; Emmer and Vilímek, Reference Emmer and Vilímek2013; Kougkoulos and others, Reference Kougkoulos2018; Drenkhan and others, Reference Drenkhan, Huggel, Guardamino and Haeberli2019) without region-specific sensitivity analysis. These techniques differ in their choice of parameters used for the analysis. For example, Allen (Reference Allen, Zhang, Wang, Yao and Bolch2019) estimated the GLOF risk for all glacial lakes (≥0.1 km2) on the Tibetan Plateau by combining lake area, upstream watershed area, potential for ice/rock avalanches, and dam slope to model and rank hazard levels. Shijin and others, (Reference Shijin, Dahe and Cunde2015) identified potentially dangerous glacial lakes in the Chinese Himalaya using the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) to calculate parameter weights. Similarly, Das and others, (Reference Das, Das, Mandal, Sharma and Ramsankaran2024) identified potentially dangerous glacial lakes using Sentinel data and the AHP framework in the western Himalaya. However, the computed hazard and risk are highly sensitive to the choice and weight of the parameters included, as different studies prioritize varying factors depending on regional settings and available data. However, it is possible to assess the reliability of the risk computed by validating it against past events.

Recent research highlights that glacial thinning in the Kashmir Himalaya is occurring at an accelerated rate compared to other parts of the Himalayan arc, with the maximal regional annual thinning rate of 0.66 ± 0.09 m (Kääb and others, Reference Kääb, Berthier, Nuth, Gardelle and Arnaud2012; Rashid and others, Reference Rashid, Majeed, Aneaus and Pelto2020). This reduction in glacial extent has also spurred the formation and expansion of glacial lakes at an alarming rate (Kumar and others, Reference Kumar, Bahuguna, Ali and Singh2020; Shugar and others, Reference Shugar2020; Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Chen, Zhao, Wang and Wang2021). The rapid expansion of existing glacial lakes and the emergence of new ones continuously exacerbate the GLOF risk to the downstream communities (Dubey and Goyal, Reference Dubey and Goyal2020; Taylor and others, Reference Taylor, Robinson, Dunning, Rachel Carr and Westoby2023). Given this backdrop, glacial lakes were mapped and assessed for their susceptibility to outburst floods across the Kashmir Himalaya from 1992 to 2024. The findings of this study are expected to contribute to the understanding of glacial lake dynamics and their associated hazards, providing valuable insights for researchers, policymakers, and stakeholders involved in disaster risk reduction and climate adaptation efforts.

2. Study area

The Kashmir Himalaya lies between the Greater Himalayan mountain range and the Pir Panjal mountain range in the Jammu and Kashmir region, India, located between 33°20’–34°40’ N latitudes and 73° 40’–75°40’ E longitudes (Fig. 1). It has a topographically rugged terrain (Kashani and others, Reference Kashani, Jan, Bhat, Najar and Rashid2024) with elevations ranging from 1073 to 5236 m above mean sea level (a.m.s.l.). The valley experiences a temperate climate characterized by an average rainfall of ∼1000 mm, partially from the Indian monsoon and mainly from western disturbances. The average maximum and minimum temperatures in the Kashmir Himalaya have increased by 1.4 °C and 0.88 °C over the last four decades (Dad and others, Reference Dad, Muslim, Rashid and Reshi2021). To date, no GLOF events have been reported in the Kashmir Himalaya. However, the region hosts 147 glaciers undergoing accelerated recession compared to the Himalayan arc in response to climate change (Romshoo and others, Reference Romshoo, Fayaz, Meraj and Bahuguna2020). Additionally, the existence of 326 rock glaciers across the region demonstrates the widespread presence of permafrost, underlining the risk to glacial lake dams due to long-term permafrost degradation, landslides, and rock and snow avalanches under existing and future warming scenarios (Bhat and others, Reference Bhat, Rashid, Ramsankaran, Banerjee and Vijay2025).

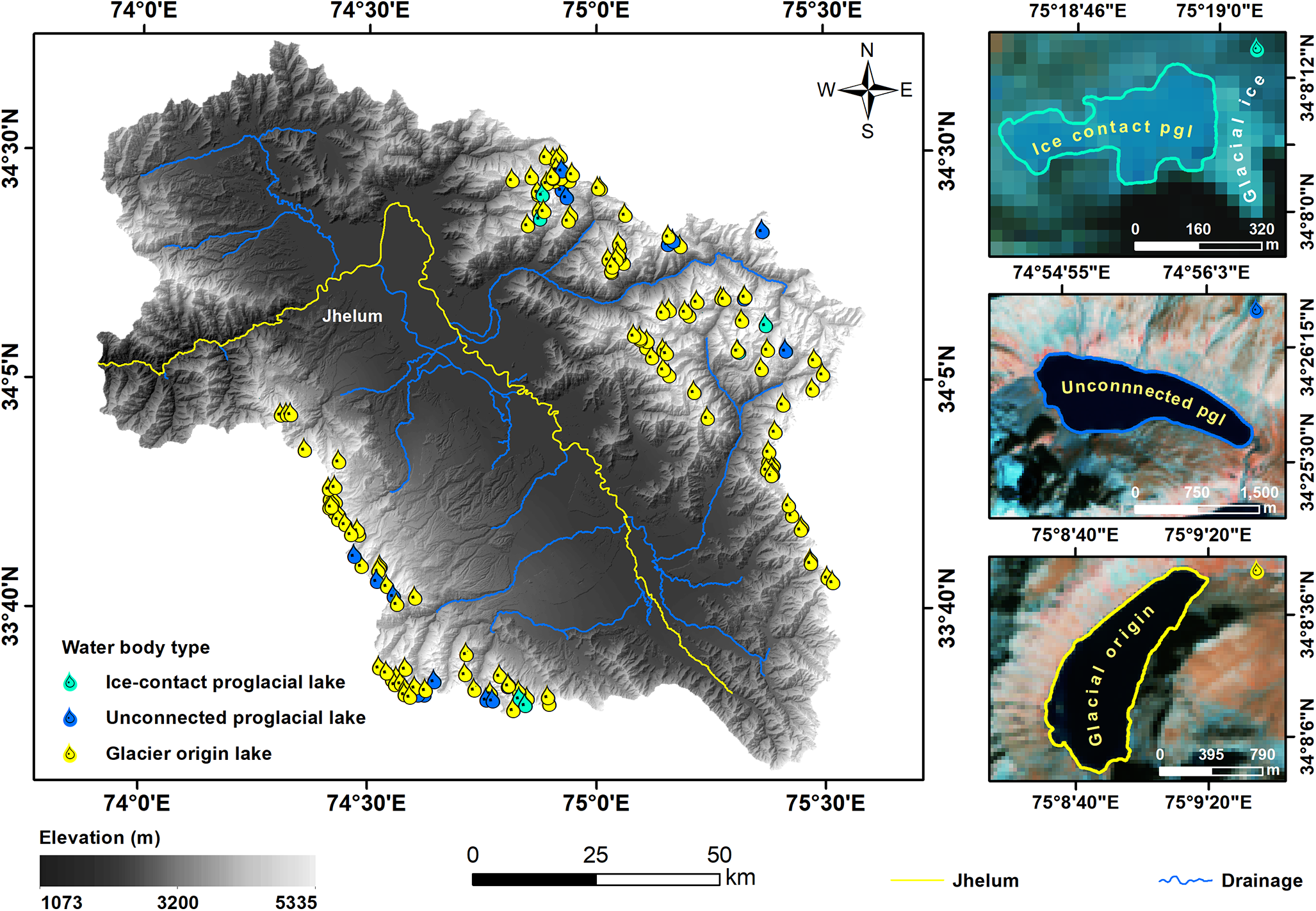

Figure 1. Location, geographical setting, and drainage network of the research area. The map outlines the study area boundary, area topography, and hydrological networks. Star markers indicate the locations of a few lakes in the Kashmir Himalaya.

3. Data and methods

3.1. Datasets

We utilized a range of datasets that included medium and high-resolution optical satellite imagery, Digital Elevation Model (DEM) and earthquake-related data. Optical satellite imagery from the Landsat series was utilized to map the glacial lake extents for the years 1992 and 2024 (EROS, 2020a; EROS, 2020b). The available images during the melting season (July–September) were selected to ensure minimal snow cover and maximum visibility of glaciers and glacial lakes. Selected Landsat images were further filtered based on individual cloud-cover percentages with a threshold of 10%. Glacier outlines from the Randolph Glacier Inventory (RGI), version 7, were used to identify glaciers across the study area (RGI Consortium, 2023). Information on the slope and potential mass-wasting areas surrounding the glacial lakes (Fujita and others, Reference Fujita, Suzuki, Nuimura and Sakai2008) was derived using the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) DEM (Wang and others, Reference Wang, Yang and Yao2012). This data was instrumental in identifying regions susceptible to mass wasting, a significant trigger for GLOFs. All the other parameters employed for the multi-criteria analysis discussed below were obtained from the visual interpretation of the Landsat data. The details of the datasets and parameters used for the current research are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Data sources for various parameters utilized in this study. While the first ten factors were used to assess the GLOF susceptibility in the Kashmir Himalaya, Google open buildings and the Randolph Glacier Inventory were used to identify the number of building settlements at risk and glaciers, respectively.

3.2. Glacial lake mapping and classification

Glacial lakes were manually delineated at a scale of 1:10 000 in a GIS environment. All identified waterbodies located >2500 m a.s.l. having an area ≥0.4 ha were classified as lakes. Waterbodies with <0.4 ha area were categorised as ponds and excluded from the analysis due to their low water volume and negligible GLOF risk (Rashid and others, Reference Rashid, Abdullah, Glasser, Naz and Romshoo2018). This threshold was used to prioritize water bodies with greater volume, which are more pertinent to assessing GLOF susceptibility in the region. The difference between the various types of proglacial and distant glacier-origin lakes is often misreported in the Himalaya, leading to the incorrect categorisation of lakes (Ahmed and others, Reference Ahmed, Ahmad, Wani, Mir, Ahmed and Jain2022a). The glacial lakes in the Kashmir Himalaya were further classified into three categories: ice-contact proglacial lakes, unconnected proglacial lakes, and distant glacial origin lakes, based on their geographic position and hydrologic connectivity to the glaciers. While ice-contact proglacial lakes are present at the termini and remain in direct contact with the parent glacier, unconnected proglacial lakes are situated close to glaciers (∼1 km) but lack direct glacial contact. Additionally, glacial-origin lakes formed through glacial erosion are located farther from the glaciers (Yao and others, Reference Yao, Liu, Han, Sun and Zhao2018; Chen and others, Reference Chen2021).

3.3. GLOF susceptibility analysis

To assess the GLOF susceptibility of the identified glacial lakes across the Kashmir Himalaya, the AHP, a structured Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) approach, was employed (Saaty, Reference Saaty2008). AHP was selected for its ability to systematically integrate expert judgment and quantitative data about various factors that contribute to the GLOF into a weighted susceptibility index (Zaginaev and others, Reference Zaginaev, Petrakov, Erokhin, Meleshko, Stoffel and Ballesteros-Cánovas2019; Zhang and others, Reference Zhang2023a; Das, and others, Reference Das, Das, Mandal, Sharma and Ramsankaran2024). The AHP workflow adopted here consists of the following four key steps.

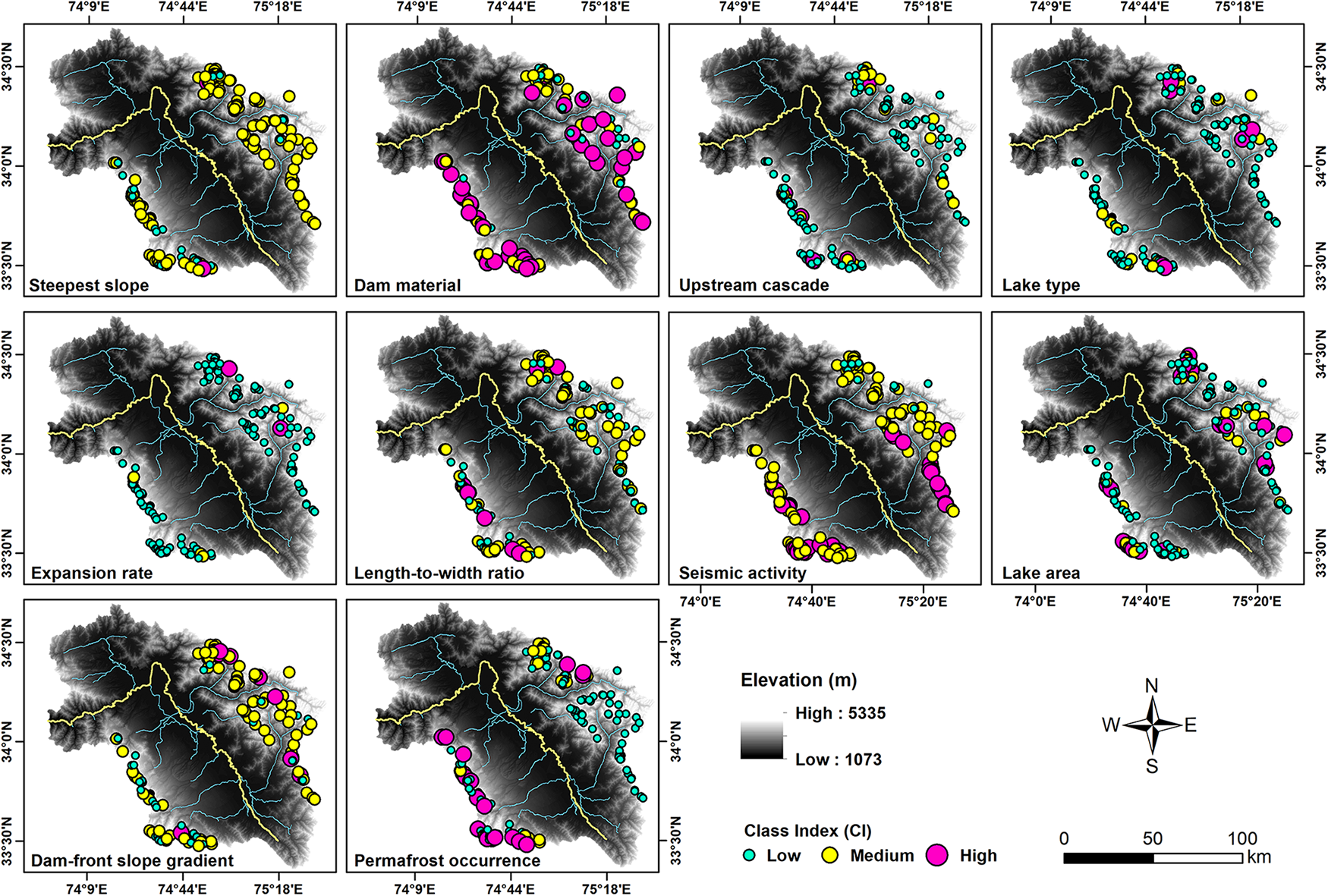

Based on the understanding from the existing studies, reported GLOF events, expert knowledge, and data availability, data about ten potential GLOF-triggering factors were generated (Nie and others, Reference Nie, Liu, Wang, Zhang, Sheng and Liu2018; Lützow and others, Reference Lützow, Veh and Korup2023; Zhou and others, Reference Zhou2024) (Table 1). The factors described below encompass a range of characteristics of the lake and its surrounding terrain (Fig. 2).

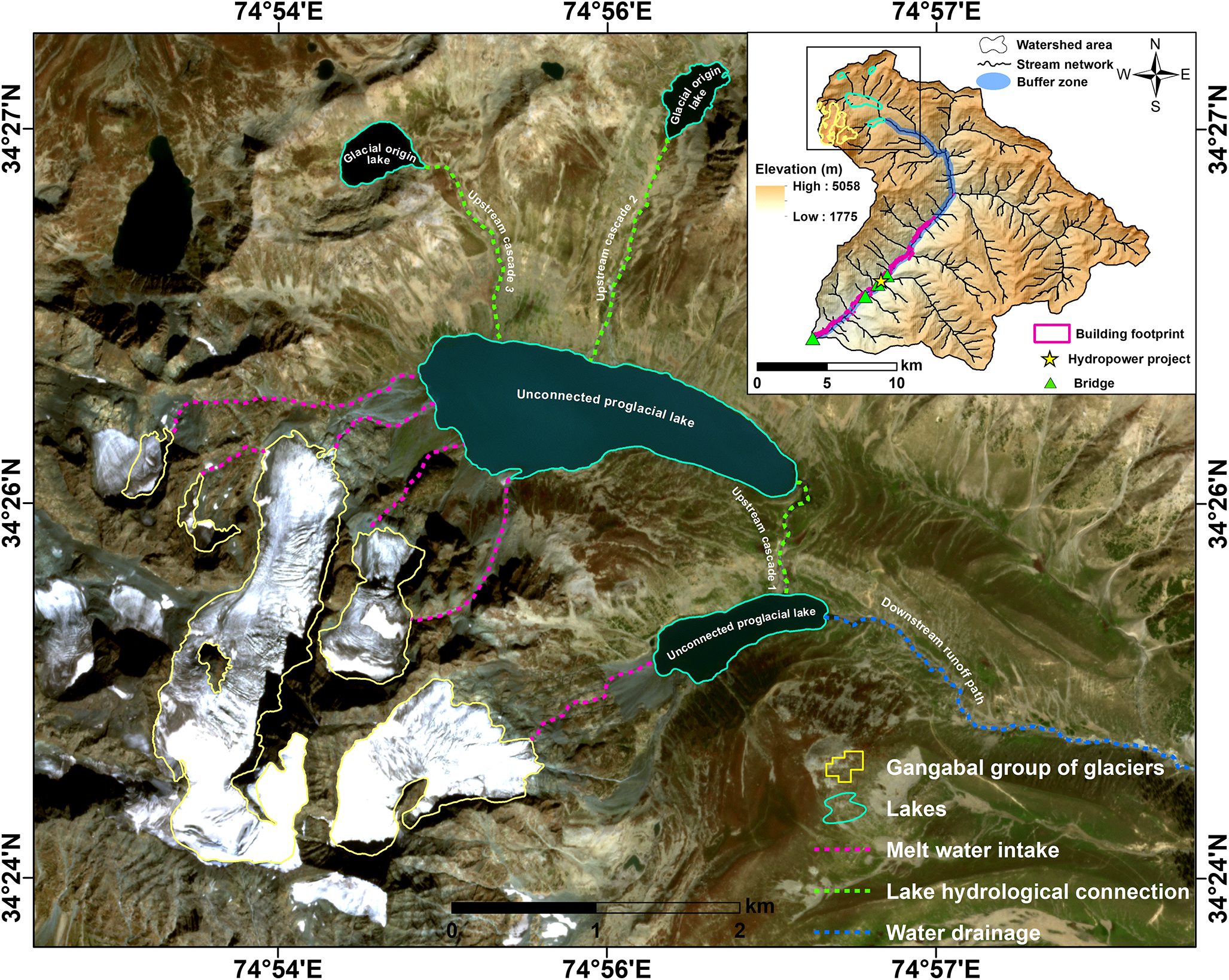

Figure 2. Example of the ten parameters utilized for GLOF susceptibility assessment, illustrated for an unconnected proglacial and glacial origin lake. The parameters include dam-front slope gradient, steepest slope, lake area, seismic activity and upstream cascades, among others, represented spatially in the surrounding area.

3.3.1. Lake type

Lake type is a key parameter in assessing GLOF susceptibility, as the nature of a lake formation and its proximity to glaciers significantly influence its stability (Clague and O’Connor, Reference Clague and O’Connor2021). For this study, lakes formed in front of the glacier snout, having direct contact with the glacial ice, were classified as ice-contact proglacial lakes, while lakes that are situated within a 1 km buffer of the glacier snout, having no direct contact with the glacial ice, were classified as unconnected proglacial lakes. Lakes located in areas where no glaciers are currently present were classified as distant glacial origin lakes (Chen and others, Reference Chen2021).

3.3.2. Lake area

Larger lakes typically have a higher volume of stored water and exert more hydrostatic pressure on the lake dam, which can result in more destructive GLOF events (Fischer and others, Reference Fischer, Korup, Veh and Walz2021). While lake volume would provide a more accurate representation of potential flood magnitude, the absence of bathymetry data for the lakes in the study area necessitated the use of surface area as a proxy for lake hazard potential. In this study, the lake area was manually quantified using multi-temporal satellite imagery for 1992 and 2024.

3.3.3. Expansion rate

The rate of change in the lake area over time may strongly influence the GLOF hazard (Wang and others, Reference Wang, Xiang, Gao, Lu and Yao2015; Khan and others, Reference Khan, Ali, Xiangke, Qureshi, Ali and Karim2021). The expansion rate of the lakes was calculated using manually delineated lake inventories for 1992 and 2024, derived respectively from Landsat TM and Landsat OLI-2 imagery. It was determined using the following formula:

\begin{equation}E = \frac{{{A_{2024}} - {A_{1992}}}}{{{A_{1992}}}} \times 100,\end{equation}

\begin{equation}E = \frac{{{A_{2024}} - {A_{1992}}}}{{{A_{1992}}}} \times 100,\end{equation}where E is the expansion rate of the lake in percentage, A 1992 is the lake area in the year 1992, and A 2024 is the lake area in the year 2024.

3.3.4. Dam material

The spatial configuration and internal structure of moraine complexes are increasingly recognized as key determinants of glacial lake stability and GLOF susceptibility (Zaginaev and others, Reference Zaginaev, Petrakov, Erokhin, Meleshko, Stoffel and Ballesteros-Cánovas2019). However, due to limitations in the resolution of available DEM and the lack of in situ validation, this study did not explicitly account for the detailed geomorphological configuration of moraine complexes. The dam material associated with lakes is also considered a critical factor in assessing their susceptibility to GLOFs. Different types of dam material exhibit varying degrees of stability and vulnerability to external triggers like avalanches, earthquakes, or rapid glacier melt (Clague and O’Connor, Reference Clague and O’Connor2021). Lakes dammed by bedrock are considered more stable compared to lakes dammed by debris (Emmer and others, Reference Emmer, Harrison, Mergili, Allen, Frey and Huggel2020).

In this study, the dam material was classified into three categories: debris, rock, or a mixture of both. Classification was performed using standard elements of visual image interpretation on high-resolution Google Earth imagery, focusing on features such as tone, colour, texture, landform pattern and slope morphology, among others. To maintain mapping consistency, lakes were classified by a single expert, enabling a first-order assessment of dam material in remote and inaccessible terrain. An uncertainty analysis to assess expert bias in dam material classification was conducted and is detailed further in Section 3.7 (Data validation and uncertainty estimations).

3.3.5. Lake length-to-width ratio

Lake morphometric parameters like lake length and width have been used in the past for assessing the stability of glacial lakes (Mohanty and Maiti, Reference Mohanty and Maiti2021). Several reported GLOF events, such as those from Chinjin, Central Rimo, and particularly the South Lhonak lake, originated from elongated lakes (Shrestha and others, Reference Shrestha2023; Sattar and others, Reference Sattar2025). This could be due to a higher wave amplitude of water in an elongated lake, leading to uneven and elevated hydrostatic pressure at the leading edges, in response to sudden disturbances (Westoby and others, Reference Westoby, Glasser, Brasington, Hambrey, Quincey and Reynolds2014; Faltinsen, Reference Faltinsen2017). Based on this, the length-to-width (LW) ratio of a lake was used. A ratio closer to 1 was considered more stable, as a more circular shape tends to distribute pressure more evenly across the dam structure. In contrast, elongated lakes with higher LW ratios may exert greater hydrostatic pressure on a narrow frontal moraine dam, thereby increasing the risk of dam destabilization. In this study, the LW ratio of all identified lakes was manually determined in a GIS platform. For each lake, three measurements were taken for both the length and width to account for variations in the morphometry of the lake. The LW ratio was then calculated using the mean length and mean width of each lake with the following formula:

\begin{equation}\text{LW}=\frac{\sum_{i=1}^nl_i}n/\frac{\sum_{i=1}^nw_i}n,\end{equation}

\begin{equation}\text{LW}=\frac{\sum_{i=1}^nl_i}n/\frac{\sum_{i=1}^nw_i}n,\end{equation}where l and w are the multiple length and width measurements of the lake, and n (n = 3 for this study) is the number of measurements taken for each lake.

3.3.6. Dam-front slope gradient

Dam characteristics, such as the average slope or the steepness of the moraine dam, significantly determine the stability of the dam (Wang and others, Reference Wang, Yao, Gao, Yang and Kattel2011; Hazra and Krishna, Reference Hazra and Krishna2022). Notably, Fujita and others (Reference Fujita2013) found that lakes in Nepal, Bhutan, and Tibet that experienced GLOF events exhibited a steep lakefront area before the failure. Accurate remote sensing measurements of these parameters are challenging due to the uncertainty related to vertical resolution. In this study, the dam-front slope gradient was computed as the mean slope within a buffer zone, which was strictly downstream of the lake. The buffer extent was chosen to be 300 m, which was larger than the DEM resolution (∼30 m) but smaller than the typical scale of the valley (∼1 km). This helped in averaging out the local-scale noise in slope, while avoiding interference from the large-scale topography of the valley. The buffer was further manually corrected using Google Earth imagery to ensure that it contained only the downstream area of the lake. The slope at the pixel at location (i, j) within a buffer zone was calculated as

\begin{equation}{\text{Slop}}{{\text{e}}_{\left( {i,j} \right)}} = \arctan \left( {\sqrt {{{\left( {\frac{{\Delta z}}{{\Delta x}}} \right)}^2} + {{\left( {\frac{{\Delta z}}{{\Delta y}}} \right)}^2}} } \right) \times \frac{{180}}{\pi },\end{equation}

\begin{equation}{\text{Slop}}{{\text{e}}_{\left( {i,j} \right)}} = \arctan \left( {\sqrt {{{\left( {\frac{{\Delta z}}{{\Delta x}}} \right)}^2} + {{\left( {\frac{{\Delta z}}{{\Delta y}}} \right)}^2}} } \right) \times \frac{{180}}{\pi },\end{equation}where Δz/Δx and Δz/Δy are local elevation changes in the x- and y-direction within the buffer zone, and d is the horizontal distance between adjacent pixels. The 180/π is the conversion factor to transform the slope from radians to degrees.

The dam-front slope gradient was then determined as

\begin{equation}{\text{Gradien}}{{\text{t}}_{{\text{SDF}}}} = \frac{\sum\limits^n_{i = 1} {\text{Slop}}{{\text{e}}_{\left( {i,j} \right)}}}{n},\end{equation}

\begin{equation}{\text{Gradien}}{{\text{t}}_{{\text{SDF}}}} = \frac{\sum\limits^n_{i = 1} {\text{Slop}}{{\text{e}}_{\left( {i,j} \right)}}}{n},\end{equation}where GradientSDF is the average dam-front slope gradient, and n is the total number of pixels within the buffer zone.

3.3.7. Steepest slope

The steepest slope surrounding the lake is a crucial parameter as it can influence the likelihood of triggering mass-wasting events, such as landslides and rockfalls, which can destabilize the dam (Prakash and Nagarajan, Reference Prakash and Nagarajan2017; Sattar and others, Reference Sattar2021a). To assess the steepest slope around each lake, a 600 m buffer zone was created around the lake. The steepest slope (S max) of the buffer zone was then finally determined as

\begin{equation}{S_{{\text{max}}}} = {\text{max}}\left( {{\text{slop}}{{\text{e}}_{\left( {i,j} \right)}}} \right).\end{equation}

\begin{equation}{S_{{\text{max}}}} = {\text{max}}\left( {{\text{slop}}{{\text{e}}_{\left( {i,j} \right)}}} \right).\end{equation}3.3.8. Upstream cascade

The cascading effect from hydrologically connected upstream lakes could intensify the GLOF impact, posing amplified risks to downstream communities and infrastructure (Mani and others, Reference Mani2023; Peng and others, Reference Peng2023). Therefore, each lake in the study area was carefully examined for the presence of upstream cascades using high-resolution Google Earth Imagery, and the number of hydrologically connected lakes was recorded in a GIS environment.

3.3.9. Permafrost occurrence

Permafrost degradation due to rising temperatures can lead to the weakening and eventual collapse of moraine dams (Haeberli and others, Reference Haeberli, Schaub and Huggel2017; Pandey and others, Reference Pandey, Banerjee, Ali, Khan, Chauhan and Singh2022). Thawing permafrost reduces the structural integrity of the dam material and surrounding terrain, making the system more prone to failure. The occurrence of permafrost in the proximity of glacier lakes was visually interpreted using high-resolution Google Earth imagery. Indicators such as thermokarst features, patterned ground, and surface texture were used as visual cues for probable permafrost presence. Finally, identified permafrost areas were cross-verified with the TTOP-based permafrost distribution map for the northern hemisphere, generated by Obu and others (Reference Obu2019), to assess consistency and provide a contextual basis for permafrost inference. This dataset is freely available at https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.888600.

3.3.10. Seismic activity

Seismic activity plays a crucial role in assessing the stability of glacial lakes (Wester, and others, Reference Wester, Mishra, Mukherji and Shrestha2019), particularly in seismically active regions like the Kashmir Himalaya, which falls within earthquake-prone zone V (Bilham and others, Reference Bilham, Gaur and Molnar2001; Ali and Ali, Reference Ali and Ali2020; Bhat and others, Reference Bhat, Bali, Mir and Kumar2024). Since shallow earthquakes are more destructive compared to deeper ones (Richter, Reference Richter1958; Yang and others, Reference Yang and Yao2021), this study incorporated a ratio of the intensity and depth of the past seismic events around the region. This information was sourced from the USGS (United States Geological Survey) earthquake catalogue, accessible at https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/search/. Furthermore, information on Peak Ground Acceleration (PGA) with a 10% probability of being exceeded in 50 years was also incorporated from the Global Earthquake Model (GEM) Global Seismic Hazard Map (version 2023.1), accessible at https://www.globalquakemodel.org/product/global-seismic-hazard-map. For integration, both datasets were normalized and rescaled using the min-max normalization approach and finally averaged to generate the USGS-PGA regional seismic index with minimized potential bias as

\begin{equation}{\text{SI}} = \frac{{X - {X_{{\text{min}}}}}}{{{X_{{\text{max}}}} - {X_{{\text{min}}}}}},\end{equation}

\begin{equation}{\text{SI}} = \frac{{X - {X_{{\text{min}}}}}}{{{X_{{\text{max}}}} - {X_{{\text{min}}}}}},\end{equation}where SI is the seismic index, X is the pixel value of the dataset representing the ratio of intensity and depth, and PGA, X min is the minimum pixel value in the dataset, and X max is the maximum pixel value in the dataset.

3.4. Pairwise comparisons

The above-described ten factors were incorporated to construct a pairwise comparison matrix and quantify weights for each factor through AHP. The weights were determined by the understanding gained through the historical GLOFs, literature review, and the consensus of the six subject matter experts in Himalayan glaciology (see supplementary material, Table S1 for more details). This process considers both the likelihood and influence of each factor to trigger a GLOF. Relative importance was assigned to factors using a 9-point scale where 1 indicated equal importance, and 9 indicated extreme importance. For example, in this study, the stability of the moraine dam was deemed 5 times more critical than its proximity to permafrost. Therefore, the matrix entry for this pair became 5 and reciprocally 1/5 for inverse comparison.

3.5. Determination of factor weights

The comparison matrix was normalized to calculate the relative factor weights and resolve the inconsistencies in expert judgments. Each factor was classified into three susceptibility levels (High, Moderate, and Low) based on its distribution of values following the equal-interval classification method. To maintain consistency and comparability across all the parameters, discrete index values (1, 0.5, and 0.25) were assigned to the defined susceptibility levels, respectively. These numerical equivalents were chosen based on their successful application in previous studies (Prakash and Nagarajan, Reference Prakash and Nagarajan2017; Das and others, Reference Das, Das, Mandal, Sharma and Ramsankaran2024; Zhang and others, Reference Zhang2024b). Class indices were utilized in the AHP methodology to evaluate the relative importance of different factors contributing to GLOF susceptibility, from 1 (indicating the highest importance) to 0.25 (indicating the lowest importance). The selection of a consistent set of index values was done to enhance the reliability and validity of the GLOF susceptibility evaluation. The defined factor classes and weights applied for each factor are provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Selected factors with their class intervals and equivalent Index values. The weight of each factor is computed by setting up a pairwise comparison matrix using the AHP framework.

3.6. Susceptibility assessment

The final weights for each factor were computed by multiplying the class index values (Ci) with the factor weights (Wi) and summed up for all factors to evaluate the GLOF susceptibility index (GSI) of the lake as

\begin{equation}{\text{GSI}} = \sum\limits_{i = 1}^n \left( {{C_i} \times {W_i}} \right).\end{equation}

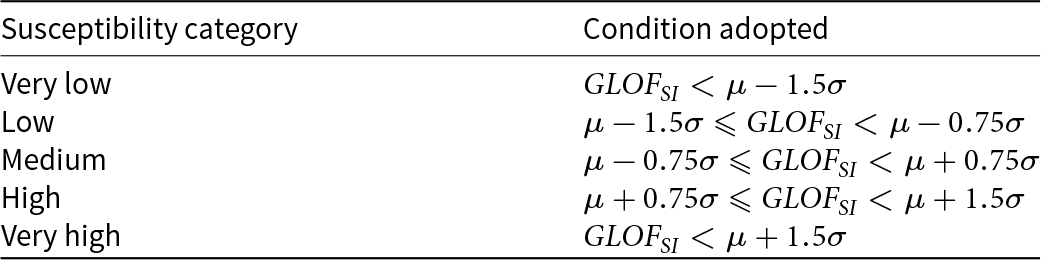

\begin{equation}{\text{GSI}} = \sum\limits_{i = 1}^n \left( {{C_i} \times {W_i}} \right).\end{equation}Several classification approaches, such as the widely used quantile method, have the potential to misrepresent data distribution by grouping elements with considerably different values into the same class or with similar values in distinct classes (Cantarino and others, Reference Cantarino, Carrion, Goerlich and Martinez Ibañez2019). Therefore, this study used a classification method based on mean and standard deviation to better capture the natural variability and distribution of GLOF susceptibility. The mean (µ) serves as a central reference point, whereas the standard deviation (σ) adjusts for value dispersion, producing a more accurate and consistent classification that reflects the inherent variability in susceptibility levels. The adoption of this classification criterion is statistically valid only if the susceptibility scores exhibit a central tendency (e.g., approximate a Gaussian distribution). Before classification, the distribution of GSI values was assessed using histogram analysis and the Kernel Density Estimate function. The thresholds for five susceptibility categories defined for this study are provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Classification of GLOF susceptibility based on mean and standard deviation thresholds.

Two plausible impact zones using buffer sizes of 250 and 500 m were delineated along the lake stream where infrastructure and settlements could potentially be affected in the event of an outburst based on the understanding from existing literature and practical considerations (Majeed and others, Reference Majeed2021; Sattar and others, Reference Sattar2025). Also, the length of the impact zone was mapped using high-resolution Google Earth Imagery, from the lake outlet until the channel widened sufficiently, reducing its ability to confine or amplify a sudden discharge. The exposure of downstream elements, such as building footprints, was obtained from the Google Open Buildings dataset, while bridges and hydropower plants were manually mapped using high-resolution Google Earth imagery.

3.6.1. Data validation and uncertainty estimations

To ensure the reliability of the generated datasets, the manually developed lake inventories were validated using high-resolution Google Earth Imagery, which incorporates data from multiple sources, including Maxar Technologies, Centre National d’Études Spatiales, Landsat, and Copernicus (Lesiv and others, Reference Lesiv2018). The area estimations utilizing the on-screen digitization approach are influenced by the spatial resolution of satellite imagery. It is noteworthy to mention that previous studies have considered a mapping uncertainty of half a pixel (Bolch and others, Reference Bolch, Menounos and Wheate2010; Paul and others, Reference Paul2013). However, this study assumes the mapping uncertainty to be a quarter of a pixel, owing to the validation carried out using high-resolution Google Earth and Planet Labs imagery. Accordingly, the uncertainty in the area was quantified as

\begin{equation}{U_{{\text{la}}}} = n \times \frac{{{\lambda ^2}}}{4},\end{equation}

\begin{equation}{U_{{\text{la}}}} = n \times \frac{{{\lambda ^2}}}{4},\end{equation}where U la is the lake area uncertainty, n and λ are the pixels along the lake boundary and the spatial resolution of the utilized satellite imagery, respectively. Since this study utilized orthorectified Landsat products having geolocation error <12.5 m (Gill and others, Reference Gill2010), the georeferencing error was assumed to be tolerable and not incorporated into the mapping uncertainty estimates. To assess dam material classification uncertainty arising from expert interpretation, a subset comprising 20% of the total lakes was randomly selected for independent classification by a group of additional subject matter experts (see supplementary material, Table S1 for more details). Comparative analysis revealed a mean expert bias of 7%, indicating a reasonable degree of uncertainty associated with visual interpretation. The consistency of the pairwise comparison matrix used in the AHP process for GLOF susceptibility assessment was rigorously validated to verify the logical coherence. The consistency ratio (CR) was calculated to evaluate the logical coherence of the pairwise comparisons used to determine weights to different factors influencing GLOF susceptibility, as

\begin{equation}{\text{CR}} = \frac{{{\text{CI}}}}{{{\text{RI}}}},\end{equation}

\begin{equation}{\text{CR}} = \frac{{{\text{CI}}}}{{{\text{RI}}}},\end{equation} \begin{equation}{\text{CI}} = \frac{{{\lambda _{{\text{max}}}} - n}}{{n - 1}},\end{equation}

\begin{equation}{\text{CI}} = \frac{{{\lambda _{{\text{max}}}} - n}}{{n - 1}},\end{equation}where CI is the consistency index, λ max is the maximum eigenvalue of the comparison matrix, n is the number of criteria compared, and RI is the random index, representing the average consistency index of a randomly generated matrix of the same size (Saaty and Tran, Reference Saaty and Tran2007). A CR of less than 0.1 is considered acceptable, indicating that the pairwise comparisons exhibit sufficient logical consistency and the assigned weights are reliable for decision-making.

To assess the robustness of the AHP-derived susceptibility framework, the described methodology, including factor selection, weights, and classification thresholds, was applied to a set of historically documented glacial lakes that have experienced outburst events across the Himalaya since 2010. The year 2010 was chosen to ensure the availability of reliable pre-event data, which is essential for evaluating the application of the AHP. This retrospective validation was carried out by reviewing the comprehensive GLOF database, containing 697 individual events (Shrestha and others, Reference Shrestha2023). In cases where lakes experienced more than one outburst event, the first event was considered to avoid bias from repeated events at the same location. In addition, GLOF events originating from supra-glacial or ice-dammed lakes were also omitted, as such lake types are absent in the Kashmir Himalaya and thus not comparable in terms of lake formation processes or outburst dynamics. Ten lakes that experienced GLOF were identified, of which two lakes that formed due to short-lived extreme precipitation events were excluded from the analysis. The remaining eight glacial lakes, which represent diverse geomorphic and climatic settings within the Himalayan arc, were selected for detailed assessment (see supplementary material, Table S3).

4. Results

4.1. Lake dynamics

For the 2024 inventory, 155 lakes above 2500 m a.m.s.l. were identified and mapped in the study area. The lakes covered a cumulative area of 1690 ± 138 ha with a mean area of 10.9 ha. Out of 155 lakes, 6 lakes were classified as ice-contact proglacial lakes, 17 as unconnected proglacial lakes, and 132 as distant glacial origin lakes (Fig. 3). The ice-contact proglacial lakes had a total area of 52.6 ± 5.7 ha and a mean area of 8.8 ha. The unconnected proglacial lakes had a total area of 290 ± 17 ha and a mean area of 8.8 ha. Distant glacial origin lakes covered a total area of 1347 ± 112 ha and a mean area of 10 ha. For the 1992 inventory, the number and classification of lakes remained the same as per the adopted mapping criteria. The ice-contact proglacial lakes covered a total area of 41.6 ± 4.8 ha and a mean area of 6.9 ha. The unconnected proglacial lakes covered a total area of 298 ± 17 ha with a mean of 17 ha. Distant glacial origin lakes covered a total area of 1340 ± 111 ha with a mean area of 10 ha.

Figure 3. Spatial distribution of water body types across the Kashmir Himalaya, categorised as ice-contact proglacial lakes, unconnected proglacial lakes, and glacial origin lakes.

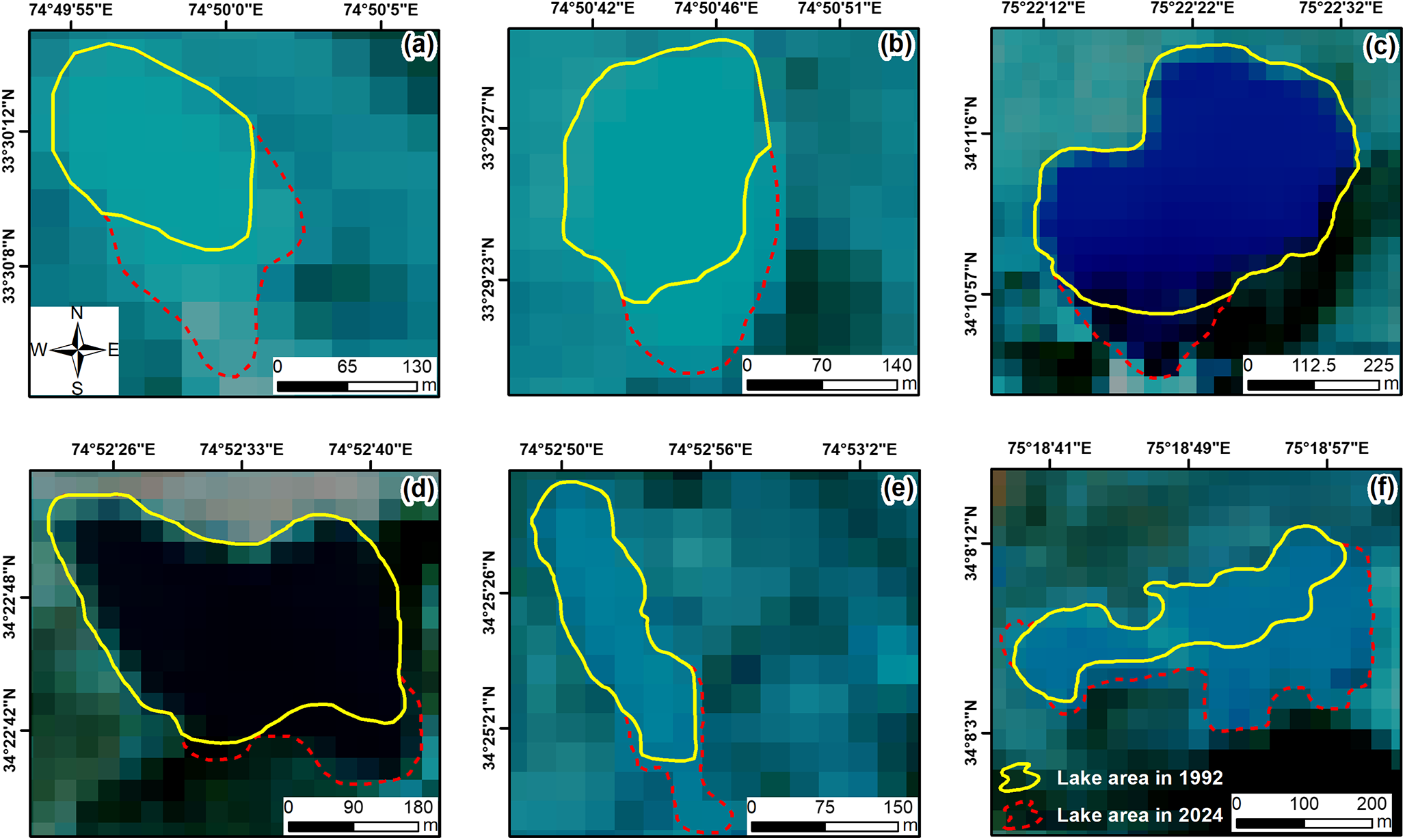

The change detection analysis revealed that the total area of all mapped water bodies increased marginally by 20 ha (1.2%) between 1992 and 2024. The glacial origin and unconnected proglacial lakes also experienced a marginal expansion of 7 ha (0.5%) and 1 ha (0.3%), respectively. The ice-contact proglacial lakes exhibited an expansion of 11 ha (26%) in a 32-year observation period across the study area (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Temporal dynamics of ice-contact proglacial lake areas from 1992 to 2024. Changes in the lake area were assessed using high-resolution satellite imagery and analysed through an on-screen digitization approach within a GIS environment.

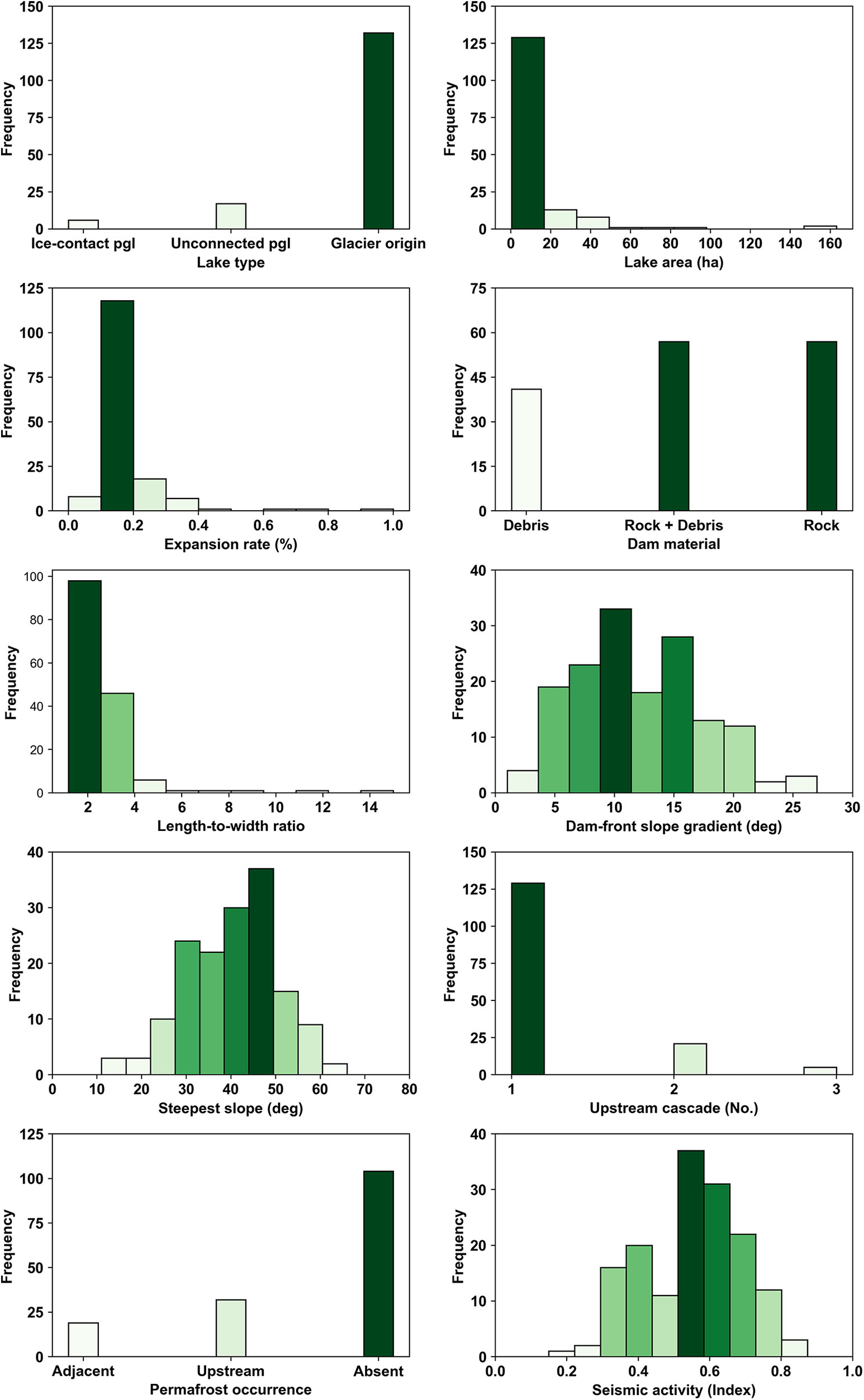

4.2. Variability in the susceptibility parameters

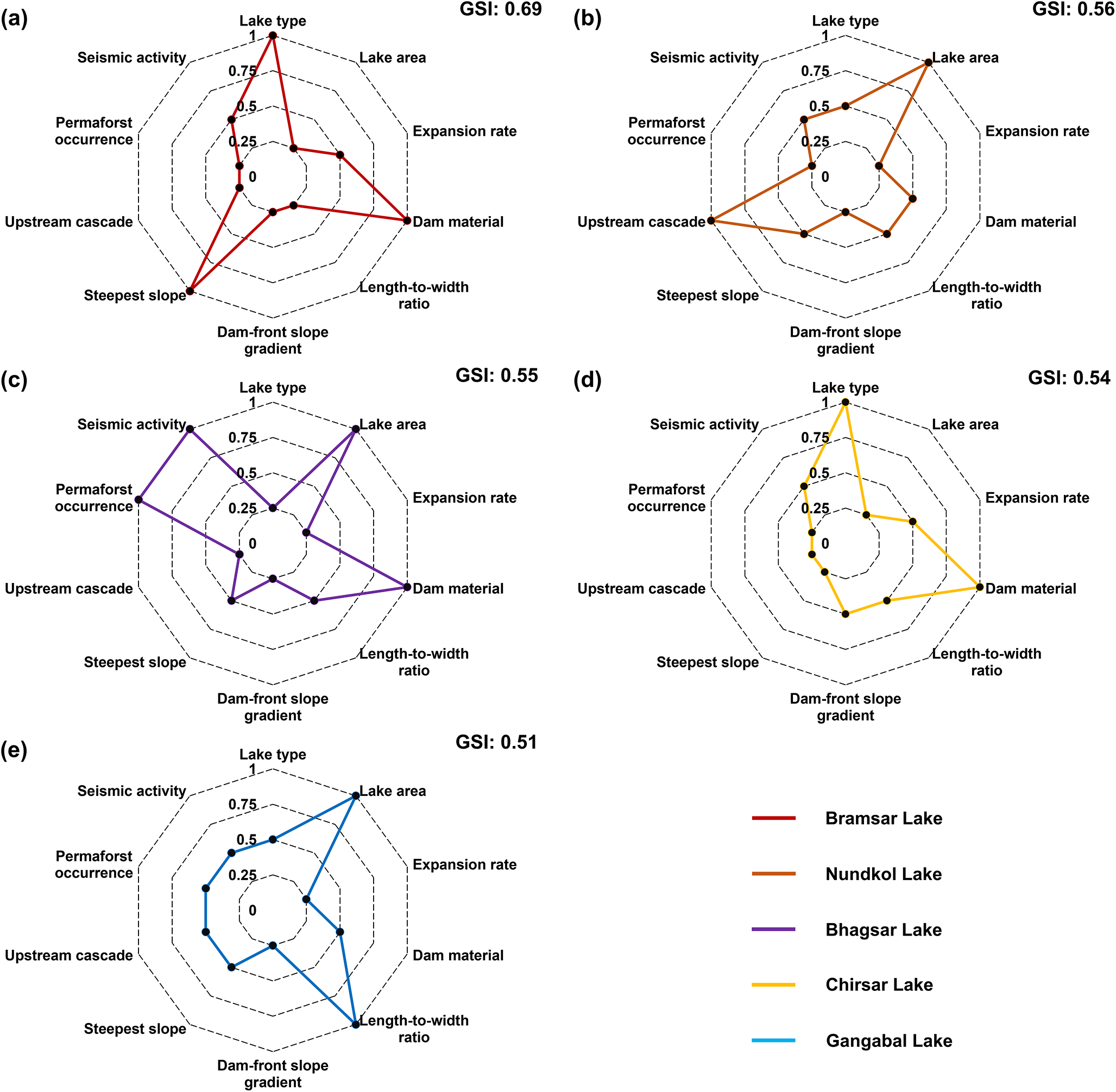

All ten parameters observed for the GLOF susceptibility assessment (Fig. 5) were classified in line with the Class Index Values of the AHP model (see Table 2). The variability of the lake types has been discussed in the previous section (4.1). The rest of the nine parameters used for susceptibility analysis are discussed in this section.

Figure 5. Histogram showing the distribution and variability of selected GLOF triggering factors utilized for susceptibility assessment.

Seventy percent (N = 108) of identified lakes had an area of less than 10 ha in 2024, 28 lakes (18%) had areas between 10 and 20 ha, and 19 lakes (12%) had areas exceeding 20 ha (Fig. 6). The overwhelming majority of lakes (N = 149, or 96%) expanded less than 33% between 1992 and 2024. A smaller subset of five lakes (3.2%) showed expansion rates between 33% and 66%. Only two lakes (1.3%) experienced expansion rates exceeding 66% during the observation period. Out of 155 lakes, 40 (26%) were dammed by debris, 57 (37%) by rock, and 58 (37%) by a mixture of rock and debris. The majority of lakes (N = 83, or 54%) exhibited moderate shape, having circularity ratios between 2 and 4. Sixty-two lakes (40%) were classified as circular with circularity ratios less than 2, while only 10 lakes (6%) were elongated, with circularity ratios greater than 4. The majority of lakes (N = 90, or 58%) had a dam-front slope gradient between 10° and 20°. Fifty-seven lakes (37%) had gentle dam-front slopes less than 10%, while only eight lakes (5%) had steeper dam-front slopes greater than 20°. Importantly, six (4%) lakes were found to have direct ice-contact with their parent glaciers.

Figure 6. Spatial variability of class index values assigned to the ten factors used for GLOF susceptibility assessment of various lake categories in the Kashmir Himalaya.

The steepest slopes in proximity to 125 lakes (81%) were between 30° and 60°. Twenty-eight lakes (18%) had slopes of less than 30°, while only two lakes (1%) had extremely steep slopes greater than 60°. The majority of lakes (N = 129, or 83%) in the study area had no associated upstream lake cascades. Notably, 21 lakes (13.5%) were identified with a single upstream lake, while a small proportion, five lakes (3.2%), had two or more hydrologically connected upstream lakes. Most lakes (N = 105, or 68%) were located in areas without surrounding permafrost. Thirty-one lakes (20%) were situated near upstream permafrost, while 19 lakes (12%) occurred in proximity to permafrost areas. Sixty-eight percent (N = 105) of lakes had a medium seismic index ranging between 0.33 and 0.66. Thirty-six lakes (23%) had a high seismic index greater than 0.66, while 14 lakes (9%) had a low seismic index less than 0.33.

4.3. GLOF susceptibility

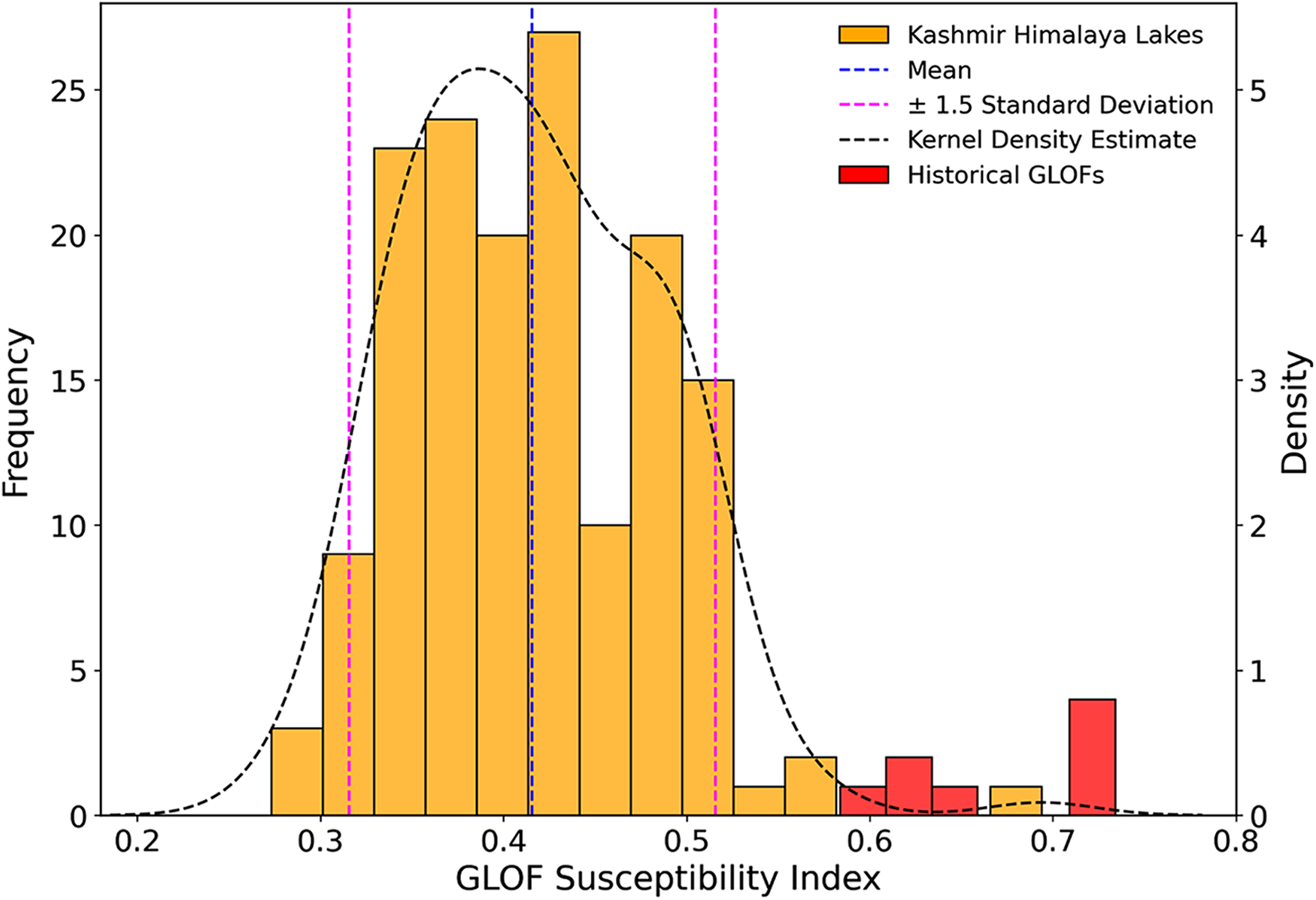

The weights assigned for the AHP-based GLOF susceptibility assessment indicated a λ max of 14.78, with a consistency index of 0.11 and a consistency ratio of 0.07. The distribution of susceptibility index values was found to exhibit a near-Gaussian distribution (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Histogram showcasing the near-Gaussian distribution of GLOF susceptibility index values, overlaid with a Kernel Density Estimate curve and reference lines for ±1.5 standard deviations around the mean.

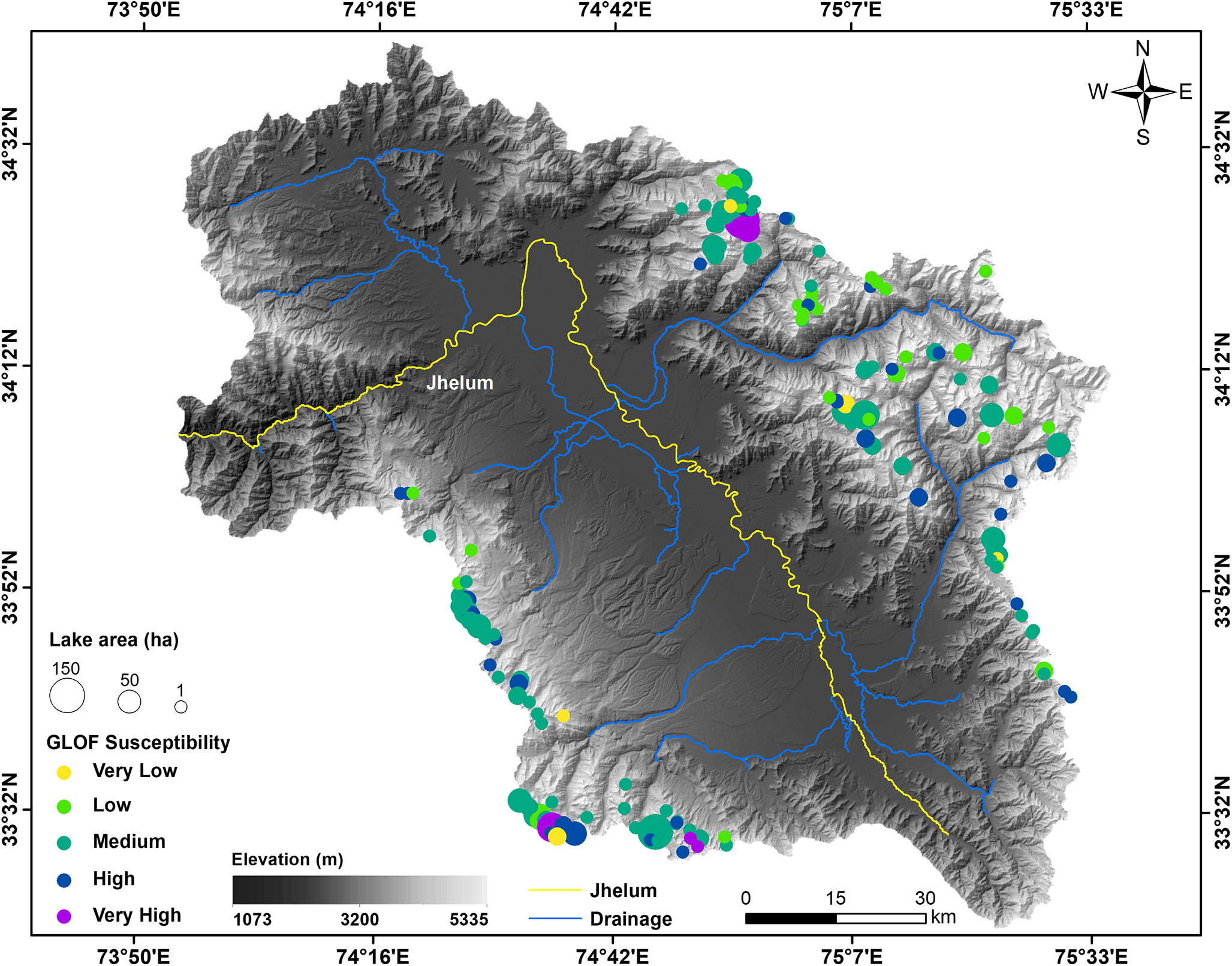

Therefore, all glacial lakes were categorised into five susceptibility classes based on mean and standard deviation (see Table 3), identifying five lakes (3%) with very high GLOF susceptibility, 35 lakes (22%) with high, 77 lakes (50%) with moderate GLOF susceptibility, 32 lakes (21%) with low susceptibility and six lakes (4%) with very low susceptibility (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. GLOF susceptibility in the Kashmir Himalaya. The map shows the spatial distribution of glacial lakes across the study area, categorised for the varying GLOF susceptibility levels, with point size scaled to represent the corresponding lake area.

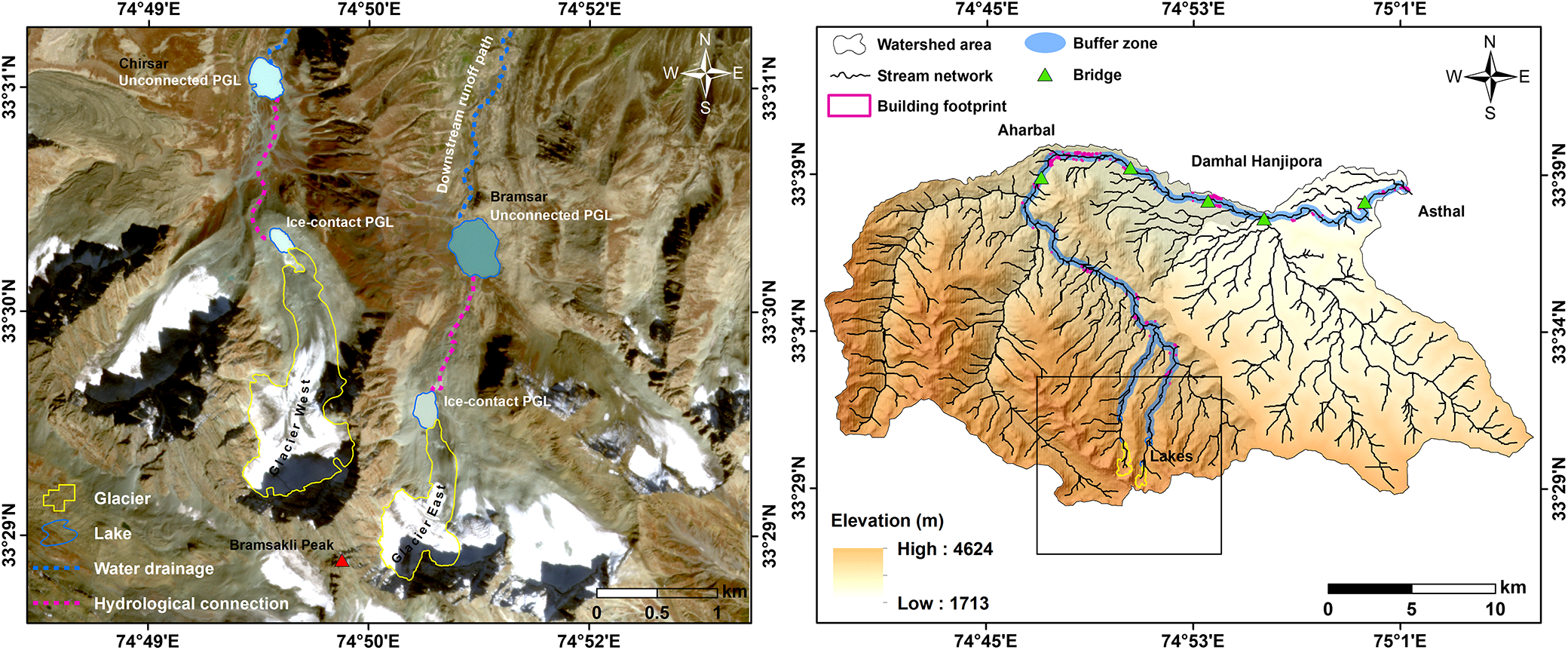

The five lakes with very high GLOF susceptibility were examined for downstream implications. Bramsar (33.4903° N, 74.8466° E) ice-contact proglacial lake and Nundkol (34.4185° N, 74.9365° E) unconnected proglacial lake were found to have the highest GLOF susceptibility. Using a flood buffer of 250 m, outburst floods from the Bramsar and Chirsar lakes pose a risk to 406 buildings, five bridges, and associated land use in the downstream area (see Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Map illustrating the geographical settings of the Bramsar and Chirsar glacial lakes. The left panel showcases the geographical area of ice-contact and unconnected proglacial lakes along with their parent glaciers and associated hydrologically connected upstream cascades. The right panel shows their common runoff paths and downstream infrastructure at risk in case of an outburst event.

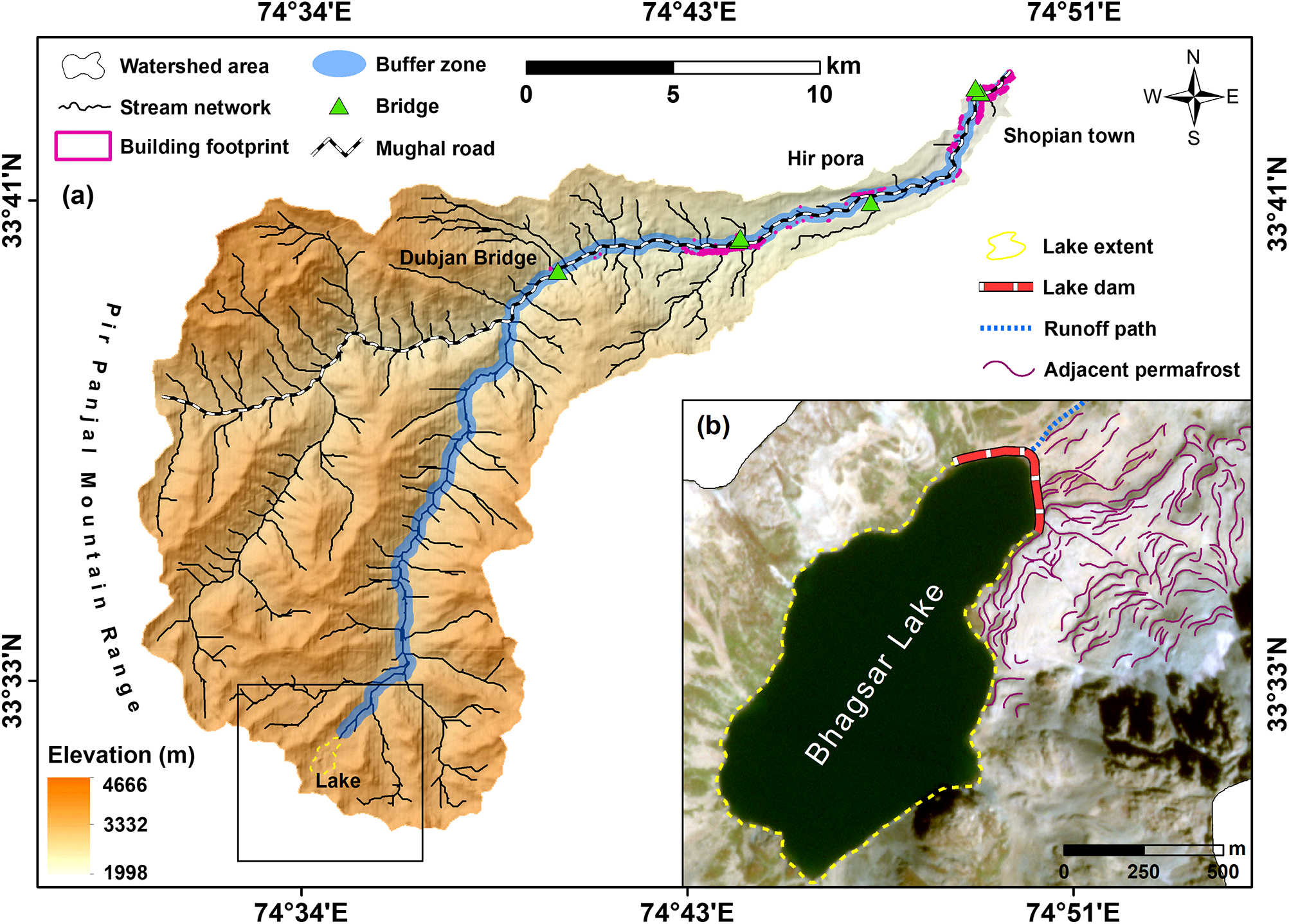

Similarly, a GLOF event from Nundkol and Gangabal Lake threatens 1184 buildings, four bridges, and a hydropower plant situated in the downstream area (see Fig. 10). Additionally, a GLOF event from Bhagsar Lake threatens 1114 buildings, six bridges, and Mughal Road, a crucial alternative route to the Kashmir Himalaya (see Fig. 11). The details of the lakes having very high GLOF susceptibility in the Kashmir Himalaya are provided in Table 4. The results generated from a 500 m buffer area and information on all lakes, along with their susceptibility values, are provided in the supplementary material (Fig. S1, S2, S3, Table S2 and Table S4, respectively). The key factors contributing to the very high susceptibility classification of five lakes are discussed further in Section 5.3.

Figure 10. Map illustrating the complex geographical and hydrological settings of the Gangabal group of glaciers. The inset highlights critical downstream infrastructure at risk, including buildings, bridges, and a hydroelectric power plant, emphasizing the need for targeted risk management strategies in the event of a GLOF.

Figure 11. Map highlighting the geographical setting of Bhagsar Lake, showcasing elements at risk including roads, bridges, and buildings. The inset provides a closer view of the lake area, emphasizing its proximity to permafrost and potential instability risk due to permafrost degradation in a warming climate.

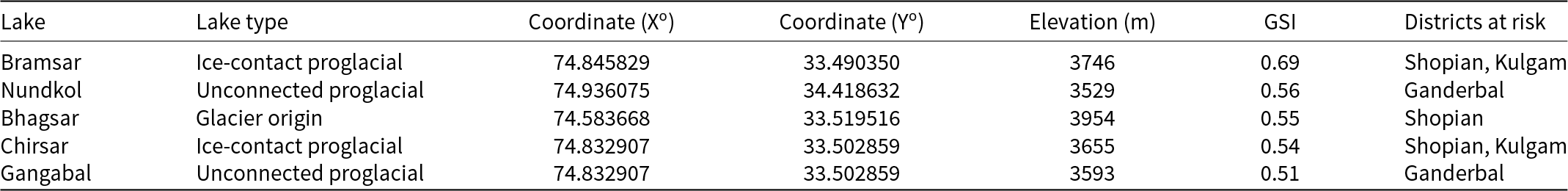

Table 4. Key details of highly susceptible glacial lakes in the Kashmir Himalaya, along with downstream areas at risk, arranged in descending order of susceptibility.

Lakes with historical GLOF events included prominent outburst cases such as Gya and South Lhonak, among others (see supplementary material, Table S3). The susceptibility index values of these lakes ranged from 0.58 to 0.73, with Chinjin ice-contact proglacial lake having the highest GLOF susceptibility. All eight lakes fall within the very high susceptibility category, as defined by the same classification thresholds used in this study (Fig. S4).

5. Discussion

5.1. Glacial lake inventory and classification

This inventory of lakes in the Kashmir Himalaya reports 6 ice-contact proglacial lakes, 17 unconnected proglacial lakes, and 132 distant glacial origin lakes. The classification approach adopted in this study diverges from the previous study (Ahmed and others, Reference Ahmed, Ahmad, Wani, Mir, Ahmed and Jain2022a), which reported 102 proglacial lakes in the region, classifying all the lakes of glacial origin as proglacial lakes. Various studies described ice-contact as the primary classifying criterion for the proglacial lakes. Chen and others (Reference Chen2021) classified proglacial lakes as lakes connected to the glacier termini and dammed by ice and/or moraine. On the other hand, Wang and others (Reference Wang2013) classified proglacial lakes into two distinct categories by taking their hydrological connection and physical contact with their parent glaciers into account. Carrivick and Tweed (Reference Carrivick and Tweed2013) showed that ice-contact and unconnected proglacial lakes differ in geomorphological, sedimentological, biological, and chemical characteristics. A step further, Hardmeier and others (Reference Hardmeier, Schmidheiny, Suremann, Lüthi and Vieli2024) discovered that the connection of proglacial lakes with their parent glaciers accelerates the frontal retreat of glaciers and affects sedimentation. These studies motivated us to distinguish ice-contact proglacial lakes from unconnected ones for GLOF susceptibility assessments.

5.2. Spatiotemporal evolution of glacial lakes

A temporal analysis of glacial lakes between 1992 and 2024 revealed notable changes in the distribution and characteristics across the Kashmir Himalaya. The increase in the areal extent of ice-contact proglacial lakes highlights their sensitivity to dynamic environmental processes, including glacial dynamics and climate variability (Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Bolch, Allen, Linsbauer, Chen and Wang2019; VanDeWeghe and others, Reference VanDeWeghe, Lin, Jayaram and Gronewold2022). Similar results have been observed by Zhang and others (Reference Zhang2023b), who observed that proglacial lakes in the western Himalaya exhibited the highest relative growth of 50% in the area between 2000 and 2020. Furthermore, Zheng and others (Reference Zheng2021a) suggested that future GLOF risk is projected to shift towards and triple in the western Himalaya. However, the smaller mean area of ice-contact proglacial lakes compared to glacial-origin lakes may suppress the immediate GLOF risk (Falatkova and others, Reference Falatkova2019), and their potential for rapid expansion poses considerable challenges for downstream communities and infrastructure, necessitating continuous observation (Li and others, Reference Li, Wang, Chang and Zhang2023).

5.3. Hydrogeomorphic factors of high-risk lakes

The AHP-driven classification of lakes into different susceptibility categories provides a nuanced understanding of the potential risks associated with each lake (Shijin and others, Reference Shijin, Dahe and Cunde2015). A consistency bias of 7.4% suggests reasonable consistency in the pairwise comparison matrix established during the AHP process. This indicates that the judgments made during the weighting process were relatively stable and consistent, contributing to the overall reliability of the susceptibility assessment (Pant and others, Reference Pant, Kumar, Ram, Klochkov and Sharma2022). Furthermore, the strong alignment between the GLOF susceptibility index and historical GLOF occurrences underscores the capacity of AHP to capture critical hazard-inducing characteristics across diverse glacial environments, despite its subjective nature. These findings not only enhance confidence in the application of AHP for preliminary GLOF hazard screening but also demonstrate its practical importance in data-limited, high-mountain regions where process-based modelling remains constrained by field access and data availability. AHP characterized five lakes, including Bramsar, Nundkol, Bhagsar, Chirsar, and Gangabal, arranged in order of susceptibility as the most susceptible to GLOF in the Kashmir Himalaya. These lakes exhibit distinct hydrogeomorphic characteristics that heighten their risk potential (see Fig. 12).

Figure 12. Radar plots showing the risk profile and factor contributions for five very high susceptible lakes across the Kashmir Himalaya.

Bramsar and Chirsar, classified as ice-contact proglacial lakes, pose significant threats due to their direct glacial connectivity and rapid expansion rates of 43% and 65%, respectively (Fig. 9) (Pastorino and others, Reference Pastorino, Elia, Pizzul, Bertoli, Renzi and Prearo2024). Studies have shown that ice-contact lakes are particularly prone to sudden outbursts as they interact dynamically with glacier retreat, expand in areas, and destabilize the dam structures (Benn and others, Reference Benn2012; Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Chen, Tian, Liang and Yang2020). Both lakes, being debris-dammed, are inherently more vulnerable to erosion and failure, especially when subjected to external triggers such as landslides and rock/ice avalanches (Allen and others, Reference Allen, Linsbauer, Randhawa, Huggel, Rana and Kumari2016). An example is the recent South Lhonak Lake outburst flood event that occurred in the northwestern part of the Sikkim Himalaya. The outburst was triggered by the slumping of ice-rich permafrost moraine on steep slopes towards the north of South Lhonak Lake in the first week of October 2023, triggering GLOF (Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Wang and An2024c; Sattar and others, Reference Sattar2025). This is particularly valid for the most susceptible Bramsar Lake, having a steep surrounding terrain with a 62o slope further intensifying the likelihood of mass movement-induced moraine failure (Furian and others, Reference Furian, Loibl and Schneider2021; Sattar and others, Reference Sattar, Haritashya, Kargel, Leonard, Shugar and Chase2021b).

Nundkol and Gangabal, despite being unconnected proglacial lakes, rank among the most susceptible ones due to their hydrological connection with multiple upstream cascades and large surface areas of 37 and 163 ha, respectively (Fig. 10). In addition, with high length-to-width ratios of 3.85 and 4.37, respectively, both Nundkol and Gangabal lakes increase the risk of structural failure, as elongated lakes exert greater hydraulic pressure on the dam structures (Faltinsen, Reference Faltinsen2017; Ali and others, Reference Ali, Kamran and Khan2017). Conversely, due to moderately stable material composition, both lakes may not be susceptible to complete moraine failures. However, their hydrological connection with two or more upstream cascades increases the likelihood of secondary outburst floods, compounding the potential downstream outburst impact mainly through the overtopping mechanism (Zhang and others, Reference Zhang2024a). Cascading events, wherein upstream lakes trigger a chain reaction of outburst events, have become increasingly evident over the last decade, underscoring their destructive potential (Dubey and others, Reference Dubey, Sattar, Gupta, Goyal, Haritashya and Kargel2024; Singh and others, Reference Singh, Anand, Durga Rao, Shashivardhan Reddy and Chauhan2024). A GLOF event that occurred from the Thyanbo glacial lake and caused massive destruction to the downstream Thame village in the Khumbu region of Nepal is a typical example of the catastrophic impact of such a cascading mechanism (ICIMOD, 2024).

Bhagsar, a glacial-origin lake exhibiting a large surface area of 76 ha, presents a different risk profile. In contrast, the lake does not have direct glacial contact, however, its dam material and adjacency to permafrost may weaken the structural integrity of the moraine due to permafrost degradation, thereby exacerbating the potential for an outburst event in a warming climate (Fig. 11) (Deline and others, Reference Deline2021; Li and others, Reference Li2022; Bhat and others, Reference Bhat, Bali, Mir and Kumar2024). Furthermore, the seismic index of 0.72 (Ci: 1) increases the probability of earthquake-induced failure, particularly in the event of a strong tremor that could compromise the stability of the loosely packed debris dam. While recent literature suggests that there is no definitive evidence linking seismic events directly to GLOFs, the potential for such events cannot be neglected. For instance, Wood and others (Reference Wood2024) reported that only about 2% of GLOF events outside the Third Pole were triggered by earthquakes, highlighting their relatively low contribution. While these figures suggest a relatively low frequency, the highly dynamic nature of the Himalaya, marked by frequent tectonic activity, necessitates caution (Kargel and others, Reference Kargel2016; Maurer and others, Reference Maurer2020; Bhat and others, Reference Bhat, Bali, Mir and Kumar2024). Additionally, the cascading impacts of seismic events on glacial lakes, particularly in regions with steep terrain and fragile geological structures, could amplify their potential role as indirect triggers (Chen and others, Reference Chen2023; Sharma and others, Reference Sharma2023). Therefore, the inclusion of seismicity as an important input parameter in GLOF hazard assessments may be appropriate in the Himalaya. Given this understanding, a relatively low weightage (4.9%) was assigned to the seismic activity to appropriately balance its contribution to the overall GLOF hazard assessment.

5.4. Limitations of the study

The AHP-based susceptibility analysis used in this study involved expert judgment to assign relative weights to multiple risk factors. While this method provides a structured framework for integrating diverse criteria, it remains inherently subjective. The reliance on expert opinion could introduce potential biases, especially when assessing complex and nonlinear processes such as mass wasting or lake outburst, unlike physically based models. However, due to data limitations and poorly constrained boundary conditions, this study relied on the AHP-based approach for regional-scale outburst susceptibility analysis and a geomorphology-informed buffer-based method to provide a first-order downstream impact assessment. Therefore, the exposure values reported in this study should be interpreted as indicative and not absolute, given the limitations of the utilized approach. Future research should aim to integrate process-based modelling techniques with the advent of more reliable datasets to improve the robustness of GLOF risk predictions. Additionally, the classification approach based on mean and standard deviation used in this study may be area-specific. As such, the application of present classification thresholds to other glacierized regions in the Himalaya or elsewhere is not recommended.

GLOF events, being inherently complex, can be influenced by factors not fully captured in this study, such as unpredictable climate extremes, long-term permafrost degradation, or hidden subglacial dynamics (Haeberli and others, Reference Haeberli, Schaub and Huggel2017). This uncertainty is further exacerbated by satellite data resolution constraints that limit the accurate characterization of incorporated factors. Factors such as the underlying dam material and the true ice-contact nature of the lake, particularly for lakes associated with debris-covered glaciers, necessitate field-based investigations. Additionally, while permafrost occurrence was assessed using visual interpretation of high-resolution imagery and cross-referenced with a coarser global dataset, this approach may not accurately reflect local-scale permafrost distribution in complex mountainous terrains like the Kashmir Himalaya.

Notably, the findings of this study are consistent with previous research on Himalayan GLOFs, which emphasizes that ice-contact and debris-dammed lakes are among the most susceptible due to their inherent instability (Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Bolch, Allen, Linsbauer, Chen and Wang2019; Zheng and others, Reference Zheng2021b). Additionally, studies conducted in the eastern Himalaya (Das and others, Reference Das, Das, Mandal, Sharma and Ramsankaran2024) have demonstrated that lakes with upstream cascades, such as those similar to Gangabal, are at an elevated risk of secondary flooding, which can significantly amplify outburst impacts. However, this study presents an alternative perspective to the findings of Ahmed and others (Reference Ahmed, Ahmad, Wani, Mir, Ahmed and Jain2022b) on Gangabal. Given that Gangabal is mostly a bedrock-dammed lake, the assumption of total dam failure is unlikely to reflect actual conditions. Such types of dams have been shown to withstand substantial stress due to structural integrity and low susceptibility to erosion, making a 100% catastrophic failure highly improbable even under extreme conditions (Emmer and others, Reference Emmer, Harrison, Mergili, Allen, Frey and Huggel2020; Wood and others, Reference Wood2024). Therefore, overestimated drainage volumes may lead to inflated hazard predictions, potentially causing unnecessary concern and inefficient allocation of resources. This underscores the importance of refining GLOF modelling approaches to incorporate realistic dam characteristics, ensuring more accurate risk assessments aimed at contributing to effective disaster preparedness strategies.

5.5. Potential downstream implications

The identified highly susceptible glacial lakes in this study require prioritized monitoring and targeted mitigation efforts to reduce the likelihood and impact of potential outburst events (Wang and others, Reference Wang and Zhou2017). This is particularly crucial for the two highly susceptible ice-contact proglacial lakes (Bramsar and Chirsar) and the two unconnected proglacial lakes (Gangabal and Nundkol), given that these lakes directly drain into other lakes. This hydrological connection introduces an additional layer of complexity and potential hazard cascade for the nearby downstream communities (Peng and others, Reference Peng2023). Therefore, in case of a GLOF event from these highly susceptible lakes with associated cascades, the flooding could rapidly increase the water volume and pressure in the downstream lake, potentially triggering a secondary outburst (Veh and others, Reference Veh, Korup, von Specht, Roessner and Walz2019). The insights reported in this study will serve as critical information for stakeholders and policymakers to proactively mitigate the impacts of GLOFs from highly susceptible lakes in the Kashmir Himalaya to safeguard downstream communities and infrastructure. The findings further emphasize the need for continuous monitoring as the identified highly susceptible lakes pose an immediate risk to 2704 downstream buildings, 15 major bridges, roads, and a hydropower plant in the study area. This could be achieved through targeted interventions, including master plans related to urban development in downstream areas, stabilization of dam material, and community-based GLOF early warning systems, emphasizing proactive disaster risk reduction strategies to enhance resilience and safeguard vulnerable populations.

6. Conclusions

In this study, a comprehensive glacial lake inventory for the Kashmir Himalaya was developed to assess the diversity of glacial lakes, their recent area changes, and the associated GLOF hazard following an AHP. This approach diverges from previous studies in the Kashmir Himalaya by focusing on the direct and indirect connections of lakes with glaciers, thereby refining the classification criteria and associated hazards. This research establishes a robust methodology for GLOF susceptibility assessments by integrating topographical, geomorphological, hydrological, and seismic factors ascertained through historical outburst events. Ice-contact proglacial lakes, despite being fewer in number, pose a high GLOF hazard owing to their direct interactions with parent glaciers and higher rate of expansion. This underscores the influence of glacier dynamics and climate warming on GLOF susceptibility. Five lakes having very high susceptibility require immediate attention to mitigate potential GLOF hazards and risks. Overall, the study underscores the need for proactive GLOF management strategies through continuous monitoring utilizing remote sensing and in situ observations, hydrodynamic modelling, and incorporating scientific knowledge into decision-making to safeguard vulnerable mountain communities and infrastructure. By providing critical insights into lake dynamics, GLOF susceptibility, and potential downstream impacts, this study lays a foundation for future research and policy action to mitigate GLOF risks in the Kashmir Himalaya.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2025.10120.

Acknowledgements

The authors express sincere gratitude to Mr. Faisal Zahoor Jan, Mr. Imtiyaz Ahmad Bhat, Mr. Nadeem Ahmad Najar, and Mr. Shahid Younis Bhat from the University of Kashmir for their participation in the manuscript-related discussions. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the United States Geological Survey (USGS) for providing free access to Landsat data and historical seismic activity records, and Planet Labs PBC for providing free access to high-resolution satellite imagery used in this study. The authors thank the Editors and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, which improved the content and structure of the manuscript.

Author contributions

SDRK conceptualized the study, curated and analysed the data, developed the methodology, conducted software-based validations, prepared visualizations, wrote the original draft, and carried out revisions. SA assisted in data curation and visualization. IR conceptualized the study, secured funding, supervised the project, provided resources, and contributed to writing and revisions. AB supervised the work, reviewed the manuscript and visualizations, and contributed to the revisions. UM helped in the visualization and contributed to the manuscript-related discussions. All authors participated in discussions, reviewed the final manuscript and approved it for publication.

Financial support

This study was carried out as part of the research project, ‘Identifying current and future GLOF risk over contrasting topographic and climatic zones of the Indian Himalaya using earth observation data and modelling’, funded by the Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India (Grant Number—MOES/PAMC/H&C/127/2019-PC-II).

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15051825.