Introduction

Social scientists are increasingly concerned with the adverse implications of negative affect across party lines. Partisan resentment is associated with multiple negative outcomes, from discrimination of out‐party supporters to democratic backsliding (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019; Kingzette et al., Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021; McConnell et al., Reference McConnell, Margalit, Malhotra and Levendusky2018; McCoy & Somer, Reference McCoy and Somer2019; Orhan, Reference Orhan2021).Footnote 1 It is thus not surprising that scholars have closely explored the drivers of partisan resentment and how they vary cross‐nationally (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Bracken, Gidron, Horne, O'Brien and Senk2023; Boxell et al., Reference Boxell, Gentzkow and Shapiro2020; Drutman, Reference Drutman2020; Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020; Harteveld, Reference Harteveld2021a, Reference Harteveld2021b; Horne et al., Reference Horne, Adams and Gidron2023; Reiljan, Reference Reiljan2020; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021).

Partisan affect varies not only across countries but also over time: it increases during election campaigns – and then subsides after elections conclude (Bassan‐Nygate & Weiss, Reference Bassan‐Nygate and Weiss2022; Hernández et al., Reference Hernández, Anduiza and Rico2021; Michelitch, Reference Michelitch2015; Singh & Thornton, Reference Singh and Thornton2019). So far, scholars have focused on the factors that intensify affective polarization over time. In this paper, we turn to mechanisms that lead to a post‐election reduction in negative partisan affect: that is, which partisans come to express warmer feelings towards which opposing parties and at which stage of the political cycle? Answering these questions is crucial if we seek to understand the processes that regulate partisan hostility in general and to identify conditions that are conducive to improvement in partisan affect after election campaigns are over.

Synthesizing insights from research in electoral politics and political psychology, we theorize two such mechanisms of post‐election decline in negative partisan affect: winners' generosity and coalitional power‐sharing arrangements. Based on work in political psychology, and specifically social identity theory, we expect that those who perceive themselves as winners of the elections will express lower levels of partisan dislike towards out‐parties (Sheffer, Reference Sheffer2020). Second, in line with work on coalition heuristics, we hypothesize that shared governance is reflected in warmer affective evaluations among supporters of co‐governing parties (Horne et al., Reference Horne, Adams and Gidron2023; Praprotnik & Wagner, Reference Praprotnik and Wagner2021). These two mechanisms serve as affective pressure valves, leading to post‐election decline in out‐party negative affect.

While these two mechanisms are analytically distinct, they are often hard to disentangle empirically. This is in part because in many democracies, public consensus regarding the likely composition of the new government is achieved shortly after election results are published,Footnote 2 and perceptions of whether a party has won an election are usually correlated with whether it ends up (or is expected to end up) in government. This makes it difficult to conclude whether post‐election changes in partisan affect are driven by the effects of perceptions of who won the election or the composition of the government.

To address this challenge, we analyse novel panel survey data designed uniquely to facilitate the study of partisan affect in a multi‐party context (Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Sheffer and Mor2022a). The Israel Polarization Panel (IPP) allows us to observe shifts in partisan affect before and after the elections, link them with citizens' perceptions of winners and losers in the elections and document how these citizens' affective evaluations respond to coalition formation. We take advantage of a unique moment of political uncertainty, in which the composition of the governing coalition remained entirely unclear for an unusually long period of time after the elections. We focus on the elections that took place in March 2021, which was the fourth time Israel went to the polls since 2019. This election resulted in a high degree of uncertainty and prolonged coalition negotiations, involving the entire spectrum of parties represented in the Knesset, which created a de facto separation between the immediate post‐election formation of perceptions of winners and losers and the formation of the coalition government in June 2021. (Below, we provide evidence for this ambiguity in public opinion perceptions.) These unique circumstances, and the fact that the IPP includes waves fielded both before and after the election as well as after the formation of the government, allow us to avoid the frequently occurring confounding of electoral performance and governance status. We are thus well‐positioned to separately test our two theoretical mechanisms of post‐election decline in negative partisan affect.

The analyses of the panel survey data support both our theoretical expectations. With regard to the mechanism of winners' generosity, we find that self‐perceived winners' affective evaluations of all out‐parties improved on average by 2.7 percentage points, a statistically significant change; we do not detect any change in out‐party affective evaluations among self‐perceived losers. The coalitional partnership effect is also substantively meaningful: when comparing pre‐election to post‐coalition formation sentiment change, we find that coalition members provide each other with an affective bonus of 8.6 percentage points, a highly significant change that is over three times larger than that of winners' generosity. We also find that supporters of opposition parties come to express more negative affective evaluations of parties in the coalition, suggesting that the affective consequences of co‐governance are multifaceted.

These findings contribute to research that focuses on mechanisms of negative affect decline (Huddy & Yair, Reference Huddy and Yair2021; Levendusky & Stecula, Reference Levendusky and Stecula2021; McCoy & Somer, Reference McCoy and Somer2021). More specifically, our findings demonstrate how institutional contexts shape the diffusion of out‐partisan negative affect in the aftermath of acrimonious elections (Drutman, Reference Drutman2020). While the mechanisms of winners' generosity should operate across contexts (Sheffer, Reference Sheffer2020), the coalitional pressure valve is only available in electoral systems that produce coalition governments (Lijphart et al., Reference Lijphart1999). And our findings regarding the intensification of negative affect among supporters of opposition parties uncover the dark affective side of the kinder, gentler politics that characterize proportional‐representation, coalition‐based political systems (Hahm et al., Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2023; Horne et al., Reference Horne, Adams and Gidron2023).

This study joins the emerging literature on partisan affective evaluations outside the United States (Boxell et al., Reference Boxell, Gentzkow and Shapiro2020; Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2023; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Mendoza and Rooduijn2022; Harteveld, Reference Harteveld2021a; Harteveld & Wagner, Reference Harteveld and Wagner2023; Lauka et al., Reference Lauka, McCoy and Firat2018; Reiljan, Reference Reiljan2020; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021). Since virtually all Western democracies outside of the United States are characterized by multi‐party systems, it is crucial that scholars pay closer attention to the ways in which multi‐party competition and cooperation shape partisan resentment (Drutman, Reference Drutman2020; McCoy & Somer, Reference McCoy and Somer2019). Our findings should also motivate more work on how perceptions of winning and losing in elections are formed in multi‐party systems and their implications for polarization, democratic well‐being, and trust in government (Blais & Gélineau, Reference Blais and Gélineau2007; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Arnesen and Werner2023; Gattermann et al., Reference Gattermann, Meyer and Wurzer2022; Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Klemmensen and Serritzlew2019; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Karakoç and Blais2012).

The paper proceeds as follows. We begin with explicating our theoretical expectations – winners' generosity and co‐governance – building on research in political psychology and the institutional underpinnings of partisan affect. After outlining their distinct observable implications, we turn to present the Israeli political context and introduce the IPP. Then, we discuss our empirical approach, which relies on a series of t‐tests to investigate our theoretical expectations. We test two hypotheses in the order in which they were presented and conclude with a discussion of our key findings and their implications for the comparative study of affective polarization. We also discuss the limitations of our data and research design, specifically in terms of scope conditions.

Theoretical expectations

Scholars have closely examined factors seen as responsible for rising affective polarization, such as social sorting into parties (Harteveld, Reference Harteveld2021b; Mason, Reference Mason2016), economic inequality (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, McCarty and Bryson2020) and the rising salience of cultural issues across Western publics (Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020). While the literature is largely focused on what accounts for increases in affective polarization, there is evidence that negative partisan affect subsides after elections. Both Singh and Thornton (Reference Singh and Thornton2019) and Hernández et al. (Reference Hernández, Anduiza and Rico2021) convincingly document this decline in negative affect using comparative survey data and both attribute this pattern to the decreasing salience of elections in the aftermath of the campaigns. However, this existing work does not outline specifically which groups of partisans would come to express warmer feelings towards which out‐parties. In addition, it is unclear whether there are countervailing developments that may attenuate this change, pushing some groups of partisans to express growing negative affect while their fellow citizens' affective evaluations of out‐parties improve. To push forward this research agenda, we turn to two potential pathways of post‐election reduced partisan animosity that are analytically distinct despite their almost inevitable co‐occurrence in the dynamics of electoral competition: winning elections and power sharing through co‐governing.

Winners' generosity

Insights from political psychology, and specifically social identity theory, lead us to expect that post‐election perceptions of winning and losing likely feed into partisan affective evaluations. Specifically, partisan animosity is expected to respond to changes in a sense of political threat and reassurance, according to Huddy et al. (Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarøe2015). As these authors note, ‘anger is most likely to arise in response to electoral threats, whereas positive emotions increase under conditions of reassurance’ (p. 4). We expect these emotions to spill over and colour out‐parties affective evaluations (Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Rogers and Snyder2016). That is, a sense of threat following electoral loss will be expressed in more negative affective evaluations of political opponents, while reassurance among electoral winners will result in less negative affective evaluations (Duck et al., Reference Duck, Terry and Hogg1998; Oc et al., Reference Oc, Moore and Bashshur2018). Note that our expectation is not that winners express warm feelings towards political opponents but rather warmer (yet potentially still negative) affect compared to pre‐election levels.

And indeed, in the few accounts that trace post‐election attitudinal dynamics (Baekgaard, Reference Baekgaard2023; Singh & Thornton, Reference Singh and Thornton2019), one major source of divergence in the pace and magnitude of decline in partisan hostility is the fate of one's party in the elections. Analysing survey panel data collected before and after the Canadian elections of 2015, Sheffer (Reference Sheffer2020) shows that partisan‐based discrimination (as measured in economic decision‐making games) of election winners towards election losers declined substantially in the weeks following the elections while in‐group bias among elections losers remained stable. Importantly, this study focused on a case in which an opposition party gained an absolute majority and immediately formed a government, making it difficult to identify whether any warming of affect towards losing parties emanates from being an electoral winner or from holding office.

Here, we depart from this line of work by focusing on a case in which electoral performance was temporally separate from and non‐predictive of government membership. We also rely on voters' subjective evaluations of whether their parties won or lost, instead of determining it ourselves. This follows a growing body of work that uses such self‐reports and finds that voters' perceptions of winning and losing are dependent on a broad set of factors (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Karakoç and Blais2012; Stiers et al., Reference Stiers, Daoust and Blais2018). We, therefore, expect to see the potential impact of winning among those who see themselves as having voted for a winning party, allowing us to evaluate these perceptions at different points in time. This leads us to pose our first hypothesis:

H1 (Winners' generosity). Negative out‐partisan affect will subside following the elections among perceived winners.

Note that we are interested in the implications of self‐perceptions of winning and losing, rather than in the roots of these perceptions. As previously acknowledged, ‘existing literature has devoted almost no attention to the question of when voters feel like they are either winners or losers of an election’ (Plescia, Reference Plescia2019, p. 797). As can be expected, it is often the case that supporters of parties that received most votes and seats perceive themselves as political winners (Stiers et al., Reference Stiers, Daoust and Blais2018). Yet this is not the only path towards a subjective sense of winning. Supporters of parties that increased their share of the vote improved their electoral performance compared to the previous elections and compared to their pre‐election expectations, also tend to view themselves as electoral winners. The degree to which these factors matter likely turns on contextual features such as the electoral system and parties' ideological profile (Gattermann et al., Reference Gattermann, Meyer and Wurzer2022). Voters' perceptions of winning and losing are also shaped by a ‘loyalty premium’ in which a party's voters tend to report that it won more than out‐partisans do (Baekgaard, Reference Baekgaard2023; Singh, Reference Singh2014). Thus, it is likely that within our sample, different constituencies can identify as winners (as well as losers) for different reasons. We remain agnostic about the sources of winners' perceptions as our theoretical expectation pertains to the implications of these perceptions on partisan affect.

Co‐governance

Institutional power‐sharing arrangements, and specifically coalitional co‐governance, can warm partisan affective evaluations. There are several theoretical reasons why partisans are likely to express warmer feelings towards parties that serve in coalitions with their own party. First, parties that are in power together are perceived as more ideologically proximate (Fortunato & Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2013), and this perception of increased ideological proximity may translate into warmer affective evaluations (Lelkes, Reference Lelkes2021). Second, public media interactions between parties that co‐govern together are warmer than interactions across the coalition‐opposition divide, and such warm elite interactions can signal to partisans that they should also express warmer affective evaluations towards coalition partners (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Weschle and Wlezien2021). Lastly, coalitions can constitute a super‐ordinate identity shared by its members; that is, supporters of coalition parties may develop a shared sense of ‘we’ against the ‘them’ of opposition parties (Brewer, Reference Brewer, Capozza and Brown2000). This sense of shared identity is also likely to be reflected in warmer affective evaluations among coalition partners.

In line with this logic, Bassan‐Nygate and Weiss (Reference Bassan‐Nygate and Weiss2022) identify a causal effect of information regarding potential coalition formation on affective evaluations within the Israeli context. They demonstrate experimentally that information signals that a unity government between left and right will be formed leads to warmer evaluations across the left‐right partisan divide. Using a similar research design, Praprotnik and Wagner (Reference Praprotnik and Wagner2021) report similar results from an experiment conducted in Austria. Beyond these country‐specific studies, a broad comparative experimental study conducted in 25 European polities similarly concluded that ‘coalition partnership significantly lessens affective polarization’ (Hahm et al., Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2023, p. 2).

These findings are supported by analyses of comparative observational data from a large number of countries, which similarly argue that coalitions are followed by warm partisan affect among co‐governing partisans (Horne et al., Reference Horne, Adams and Gidron2023). Importantly, this affective coalitional bonus does not disappear the moment a coalition is dissolved. Analysing survey data collected since the mid‐1990s across Western democracies, Horne et al. (Reference Horne, Adams and Gidron2023) show that partisans provide coalition partners with an affective bonus that lingers in the immediate years following the dissolution of the coalition. These dense networks of present and past coalitional cooperation can help explain why affective polarization is lower in proportional systems with multi‐party coalitions than in majoritarian systems with no coalition governments (Drutman, Reference Drutman2020; Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020).

This leads us to pose our second hypothesis:

H2 (Coalition bonus). Following coalition formation, supporters of coalition parties express warmer feelings towards other coalition parties.

Observable implications

The two hypotheses generate distinct observable implications. First, they are distinct with regard to the relevant out‐parties: while our winners' generosity hypothesis (H1) predicts post‐election decline of negative affect among winners towards all out‐parties, our co‐governance hypothesis (H2) predicts decline in negative affect specifically among members of the coalition (i.e., when evaluating affect by supporters of coalition parties towards the other coalition parties).

Second, the observable implications of the two hypotheses are distinct temporally. Initial perceptions of who won in the elections are already formed in the immediate aftermath of an election, while coalition formation negotiations can be stretched over long periods of time and their outcome can remain uncertain throughout their duration. The time period between election results are known and before a coalition government is formed is when the implications of our winners' generosity (H1) can be measured, while the effects of co‐governance (H2) kick in following the formation of the government. When the expected composition of a future government is known – whether because it is comprised of a one‐party majority government, the identity of which is clear given the result of the election, or because there is public consensus on who will be the parties that are likely to form the government –then H1 and H2 are confounded and affective evaluations of winners/losers are inevitably intertwined with evaluations of parties' (assumed) governing role.

In the Israeli context, 3 months have passed between the March 2021 elections and the formation of the new government in June 2021, and during that period of time, it was largely unclear what its composition might be, with an overwhelming majority of citizens expecting that no government will be formed and another election will be called even as late as May 2021, and the main potential coalition configurations discussed in the media were seen by voters as equally (un)likely to be realized (Hermann & Anabi, Reference Hermann and Anabi2021).Footnote 3 As we discuss below in detail, self‐perceptions of winning and losing the elections, as recorded immediately after the elections, do not correspond with the eventual composition of the coalition: some parties that were perceived as winners ended up in the opposition and were accordingly perceived as losers by a majority of their voters, while self‐perceived losers were eventually part of the government and their voters perceived them eventually as winners. We find this wholesale reversal of perceptions among six of the 11 parties for which we have these evaluations. By and large then, respondents were unable to foresee which parties will be included in the eventual coalition government. As a result, we are able to separately evaluate the impact of winners' generosity and co‐governance. We now turn to discuss in further detail the Israeli political context and how it allows us to test our hypotheses.

Data and measurement

The Israeli case

The Israeli political arena in 2021 provides us with a useful case study to test the hypothesized mechanisms of post‐election decline in negative affect. Israel, with its proportional electoral rules, is characterized by a highly fragmented party system. The effective number of parties in Israel has been around eight when averaging over the last 20 years (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2019). All governments in Israel have been coalition governments (Bassan‐Nygate & Weiss, Reference Bassan‐Nygate and Weiss2022).

In 2019, Israel entered a period of intense political uncertainty, with four elections taking place within only 2 years. The analyses below utilize data collected before and after the fourth election, which took place in March 2021 and led to the formation of a new coalition government in June 2021 – ousting Benjamin Netanyahu from the premiership he has held for 12 consecutive years. The coalition government formed in June 2021 brought together a diverse set of parties, ranging not only from the far right to the deep left but also incorporating an Islamist party, thus breaking a historical taboo in Israeli politics.

The coalition formed in June 2021 was surprising even for astute observers of Israeli politics. This is relevant for our research design, as the question of which parties will be part of the coalition was far from settled in the immediate aftermath of the elections. The election resulted in a stalemate, as neither the Netanyahu‐led bloc nor the anti‐Netanyahu bloc could amass a majority of 61 votes to form the government (the Israeli Knesset has 120 seats). During the 3 months of coalitional negotiations, it was uncertain that any coalition will be formed, and the option of a fifth election was widely seen as the most likely outcome even in late May (Hermann & Anabi, Reference Hermann and Anabi2021). Even more importantly, it was unclear whether an eventual government, if formed, will be based on the Netanyahu‐led bloc or an Anti‐Netanyahu amalgamation of parties (which was the eventual result), nor was it clear what the party composition of either of these potential coalitions would consist of. The composition of the government only became apparent in the final days of this period, and the government's successful swearing, in June, was seen as doubtful even as the vote was unfolding in parliament.

This prolonged political limbo allows us to distinguish between the observable implications of our two hypotheses: we can test the implications of winners' generosity on partisan affect (H1) by looking at subjective perceptions of winning immediately following the elections, and separately gauge the effect of co‐governance on affective evaluations (H2) by looking at changes in affect following the formation of the government. Compared to our research design, observational work on positive affect among coalition members is not well‐positioned to distinguish whether this warm affect is related to co‐governance rather than to other processes such as winners' generosity (Horne et al., Reference Horne, Adams and Gidron2023). Others have used an experimental design to show that pre‐election expectations for the formation of a broad post‐election coalition attenuate population‐wide affective polarization levels. This design cannot, however, provide real‐world evidence of the impact of actual, post‐election co‐governance status on affect (Bassan‐Nygate & Weiss, Reference Bassan‐Nygate and Weiss2022; Praprotnik & Wagner, Reference Praprotnik and Wagner2021).

The Israeli Polarization Panel

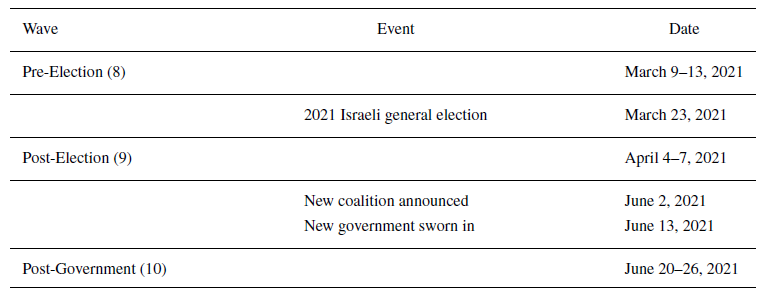

To examine the two hypotheses introduced above, we analyse data from the IPP (Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Sheffer and Mor2022a). The IPP consists of panel survey data (repeated respondents), designed specifically to examine multiple dimensions of polarization. It covers the four election cycles that took place between 2019 and 2021, with the last wave fielded following the formation of the unity government formed in June 2021. This data set is thus uniquely suited to examine within‐individual variations in partisan affect during the campaign, following the elections, at the aftermath of a new coalition formation. While the IPP contains 10 survey waves, the analyses below are limited to the last three waves since only they include all relevant questionnaire items. These survey waves were fielded shortly before and after the March 2021 elections and then following the formation of the eventual government in June 2021. Table 1 outlines the timing of the waves with respect to the election and subsequent formation of the government.

Table 1. Timeline of principal events and IPP survey waves used in the current study.

The sample in the IPP, recruited by the Midgam‐Panel public opinion firm, includes almost only Jewish Israelis (who make up around 80 per cent of the Israeli population).Footnote 4 It was originally balanced primarily on party voting in the election preceding the beginning of data collection (2015). Since data collection spans over a time period of more than 2 years, the panel experienced inevitably attrition.Footnote 5 That being said, we did not find that attrition is correlated with partisan identification, which is the main variable determining the representativeness of the sample. Since the analyses below investigate within‐individual variations in partisan affect over time (and focus on the final three waves of the panel, between which there was minimal drop‐off), potential implications of attrition for the representativeness of the data do not pose concerns for inference. The sample used in the current analysis consists of respondents who participated in the eighth wave (N = 1268), the ninth wave (N = 1240) and the 10th wave (N = 1,238) of the IPP, of which exactly 1000 participated in all three waves. A full breakdown of per‐wave descriptive statistics is provided in the online appendix.

We measure our dependent variable, partisan affect, using the out‐party feeling thermometer: ‘the workhorse survey item’ for scholars of affective polarization in the United States (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019, p. 131) and in comparative research (Boxell et al., Reference Boxell, Gentzkow and Shapiro2020; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021). Previous research conducted in the Israeli context shows that out‐party feeling thermometer scores are associated with other measures of partisan affect such as preference for social distance and discriminatory behaviors towards out‐partisans (Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Sheffer and Mor2022b). The feeling thermometer survey question appears in the IPP in the following version, adopted from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems questionnaire: ‘What is your attitude towards each of the following parties? Rate your response on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is rejection/hatred, 10 is support/sympathy; and 5 is in between’.

Our two independent variables are as follows. To test the winners' generosity hypothesis (H1), we rely on respondents' subjective assessments of whether a given party has won or lost the election. We use the following survey question: ‘In light of the election results, do you think that each of these parties won the elections or lost the elections?’ and collect evaluations for each party who ran in the election and was seen as likely to cross the 3.25 per cent electoral threshold. This survey question is adopted from previous research that examined subjective perceptions of election winners and losers (Blais et al., Reference Blais, Sevi and Plescia2022; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Karakoç and Blais2012; Stiers et al., Reference Stiers, Daoust and Blais2018). We classify winning/losing parties based on whether a majority of their voters believed, in the post‐election wave, that their party won the election. (We collected similar assessments in the 10th, post‐government formation wave of our survey.)

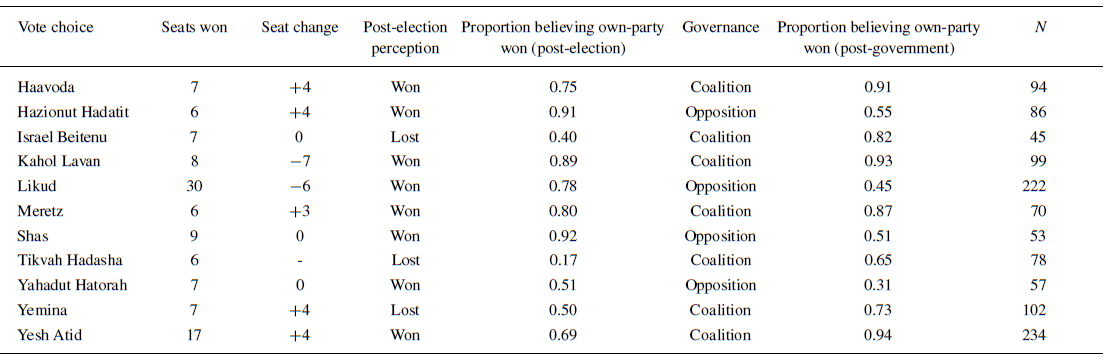

Our second independent variable, co‐governance, is based on membership in the government formed in June 2021. The relevant classification for each party, and those parties' post‐election and post‐government formation own‐party winning assessments, are reported in Table 2. Importantly, being perceived as an election winner post‐election is hardly predictive of eventual co‐governance status. Of the eight parties perceived by their voters as post‐election winners, only five ended up in coalition. The three parties perceived as losers post‐election all ended up in coalition. Post‐government formation evaluations of parties' winning/losing status changed accordingly: for example, 78 per cent of Likud voters thought their party won the election in the post‐election survey, but after the formation of government only a minority (45 per cent) continued to hold this perception. In stark contrast, only 17 per cent of Tikva Hadasha's voters believed, post‐election, that their party won (classifying the party as an election loser), a figure that soared to 65 per cent once the party ended up in government.

Table 2. Party performance and voters' perceptions of party performance in the March 2021 election

Note: Raam and Joint List are not listed owing to limited sample. Tikvah Hadasha was not represented in the Knesset prior to 2021. Post‐election classification is based on majority of party's voters believing the party won or lost.

Our analysis strategy is based on directly measuring our quantities of interest (mean sentiment towards different groups of parties) in the relevant periods – pre‐election, post‐election and post‐government. We also estimate the change in mean sentiment using standard t‐tests. The panel structure of our data allows these comparisons to account for all time‐invariant features of our respondents and allows us to follow the observation made by Diana Mutz (Reference Mutz2018) that ‘in observational settings, panel data are widely acknowledged as the ideal basis for causal conclusions’. However, our analysis does not account for time‐variant features, which to begin with we are not well‐placed to estimate (e.g., an argument could be made that political interest or news media consumption levels varied within‐respondents over the span of our three waves, but we do not measure that feature over time). Nevertheless, our panel spans a relatively short period of roughly 3 months that was characterized by heightened political strife and constant media attention to politics, suggesting that any changes we observe are more likely to reflect a response to concrete political events rather than to environmental factors.

Results

Results: Winners' generosity

Our first hypothesis is that self‐perceived winners will come to express more positive affect towards out‐parties relative to their pre‐election affect towards the same targets (H1). To examine this hypothesis, we look at data collected before the election and after the election – yet prior to the formation of the new coalition government.

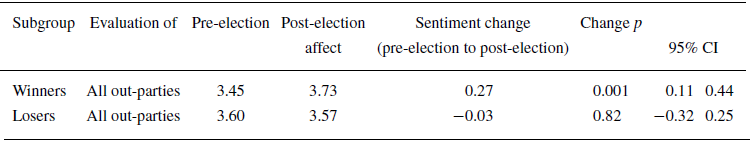

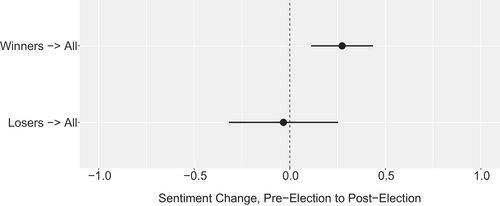

Table 3 reports changes in affective evaluations of out‐parties in the pre‐ and post‐election panel waves, divided into two subgroups: those who perceive themselves as having voted for an election winner (‘Winners'), and those who believe the party they voted for lost (‘Losers'), as identified in Table 2. Figure 1 plots the sentiment change reported in Table 3. The results strongly support our theoretical expectation: the expressed affect of winners towards all out‐parties has warmed in the immediate aftermath of the elections, and this change is statistically significant and substantively noteworthy (0.27 points increase from a 3.45 base rate affect on a 0–10 scale, which is an 8 per cent increase). This is not the case when examining changes in affect of election losers towards all out‐parties: the change here is far from statistically significant and appears very close to zero.

Table 3. Sentiment towards parties in the March 2021 Israel elections

Note: The winners subgroup consists of respondents who believed the party they voted for won the election. The losers subgroup consists of those who believed their party lost. Affect values are means per subgroup and evaluation target. Sentiment change is the difference between post‐election and pre‐election affect. p‐values and 95 per cent confidence intervals derived from two‐sided t‐tests.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence intervals.

We provide further details on these changes in Table A2 in the online appendix, where we report an analysis of pre–post election sentiment change among self‐perceived winners and losers towards each party separately. We exclude respondents who voted for the evaluated party to avoid conflating generosity towards others with self‐evaluations. While some parties are the target of substantial affect warming by both winners and losers (e.g., Kahol‐Lavan, with +0.87 and +0.87 changes, respectively), in most other cases the positive changes in affect are far more pronounced among winners, such as a +0.36 versus +0.06 change in affect towards the Likud among winners and losers, or +0.31 versus +0.07 towards Tikva Hadasha. Indeed, self‐perceived winners show significant warming of affect towards both winning and losing parties, while self‐perceived losers show no significant warming towards either group (see Table A5 and Figure A3 in the online appendix) overall, we observe statistically significant (p

![]() $<$ 0.05) warming of affect by winners towards eight out of the 13 parties we evaluate (11 out of 13 at the p

$<$ 0.05) warming of affect by winners towards eight out of the 13 parties we evaluate (11 out of 13 at the p

![]() $<$ 0.1 threshold), compared with just four such cases among losers. Furthermore, we observe an absence of warming (i.e., a change that is substantively close to zero) towards just two of the 13 parties, while for losers this obtains for eight of the 13 parties.Footnote 6 This again demonstrates that voters belonging to these two groups had overall divergent affective responses which are in line with our theoretical expectations.

$<$ 0.1 threshold), compared with just four such cases among losers. Furthermore, we observe an absence of warming (i.e., a change that is substantively close to zero) towards just two of the 13 parties, while for losers this obtains for eight of the 13 parties.Footnote 6 This again demonstrates that voters belonging to these two groups had overall divergent affective responses which are in line with our theoretical expectations.

Overall then, self‐diagnosed election winners consistently express a more positive sentiment towards all the parties in the political system once elections take place. Importantly, because these evaluations were reported shortly after the election and before any meaningful information regarding the future composition of the government, they are likely based on categorization that is derived from features such as the seat gain or loss of given parties relative to previous attainment, pre‐election polling‐based expectations or a party's ability to pass the electoral threshold – but not on the eventual governing status. Other factors may play a role, such as an expression of an expectation (strategic or honest) that one's party would be part of the eventual government, or a desire to express in‐group support, but it is difficult to form a clear expectation on the direction in which they are supposed to bias such individuals’ changes in affective evaluations towards out‐parties. What is clear is that these results substantiate that there is a meaningful difference between winners and losers in their willingness to sustain negative affect towards out‐parties, in line with our first hypothesis. In the online appendix, we report a regression analysis where we regress the change in pre‐ to post‐election sentiments on self‐perceived winning status, producing similar results to those reported here.

Additional analyses, reported in the online appendix, consider the option that warmer affective evaluations among self‐perceived winners merely reflect the expectation that their party will be part of the future coalition. If that were to be the case, we would expect self‐perceived winners to express warmer feelings specifically towards other parties that are perceived as winners, as they are the expected coalition partners. Yet this is not the case: when we differentiate changes in winners’ affect towards winning and towards losing parties, we see that there was a significant post‐election warming of affect towards both perceived winners and losers. This suggests that winners' generosity is distinct from the co‐governance mechanisms of reduced negative affect, which we now turn to discuss.

Results: Co‐governance

Our second hypothesis is that co‐governance generates warmer feelings among coalition partners (H2): that is, when one's preferred party forms a coalition with other parties, one will come to express warmer affect towards co‐governing parties. Our panel data allow us to observe within‐individual fluctuations in partisan affect following real‐world coalition agreements.

To test our second hypothesis, we investigate differences in expressed partisan affect as measured before the elections and after the formation of the coalition government. We also report results measured in the post‐election wave of the survey (i.e. after the election but before the formation of government), substantiating that the bulk of the change in affect is borne out of coalition formation dynamics and not prior to them.

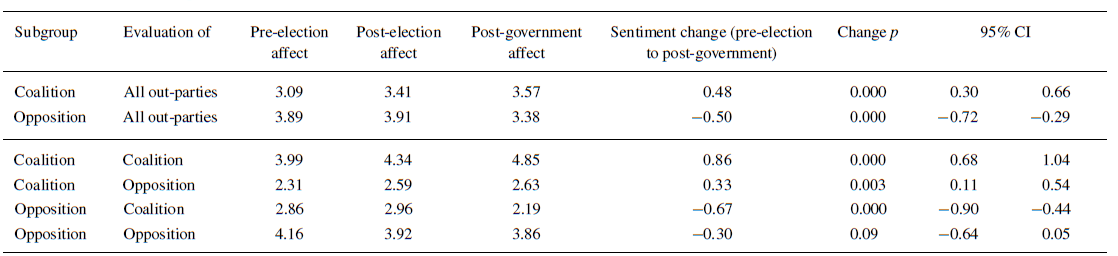

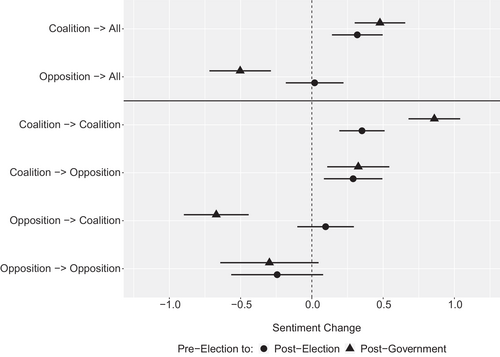

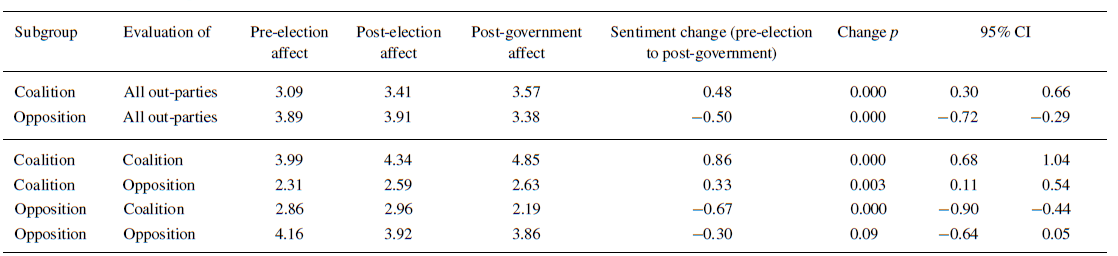

The results of our analyses, reported in Table 4 and illustrated in Figure 2, provide strong evidence that co‐governance warms partisan affective evaluations among coalition members. Supporters of parties that entered the coalition have significantly warmed up to out‐partiesFootnote 7 as can be seen in row 1 in Table 4. This change (+0.48 on a 0–10 affect scale) is highly statistically significant and substantively large, almost double the size of the shift among post‐election self‐perceived winners described in Table 3. The positive shift in affect among supporters of eventual coalition parties is particularly large (+0.86) towards co‐governing out‐parties (row 3 in Table 4). This change in affect is very similar to that reported in previous work on co‐governance and affect that analysed cross‐sectional survey data (Horne et al., Reference Horne, Adams and Gidron2023). A positive change in affect towards opposition parties (row 4) is also apparent, but it is less than half the magnitude of the positive change observed towards co‐governance partners.

Table 4. Sentiment towards parties in the March 2021 Israel elections

Note: The coalition subgroup consists of respondents who voted for parties that eventually formed the post‐election government. The opposition subgroup consists of those who voted for parties that formed the post‐election opposition. Evaluations are of either eventual coalition or opposition parties, or of all out‐parties. Affect values are means per subgroup and evaluation target. Sentiment change is the difference between post‐government formation and pre‐election affect. p‐values and 95 per cent confidence intervals derived from two‐sided t‐tests.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence intervals.

Figure 1. Pre‐election to post‐election sentiment change, among self‐perceived election winners and losers, all out‐parties.

Figure 2. Pre‐election to post‐government sentiment change, among supporters of eventual coalition and opposition parties, towards eventual coalition and opposition parties.

That these patterns appear to be strongly tied to governing status is further bolstered by a closer inspection of the temporal trajectories of affect change among eventual coalition and opposition members across our three survey waves. Looking at row 3 in Figure 2, we see that immediately after the election there is already a positive change in the affect directed by voters of eventual coalition parties towards those parties that they would co‐govern with (+0.35). However, this change is smaller than the subsequent +0.51 warming of affect towards those eventual coalition parties that we observe between the post‐election period and the actual formation of the coalition. (Together, these changes amount to the total +0.86 sentiment change mentioned earlier.) Moreover, the post‐election warming towards coalition parties is very similar to the warming that the same future‐coalition voters experience towards the eventual opposition parties (a change of +0.38 and +0.28, respectively, see rows 3 and 4), suggesting that it might be an artefact of winner's generosity experienced by some of these voters. In comparison, the subsequent change in affect towards eventual opposition parties moving from post‐election to post‐government is effectively zero (+0.04), which, compared with the +0.51 change in affect in this period of time towards co‐governance partners, is suggestive of these affective changes taking place primarily as a result of changes brought upon by the formation of the government rather than by processes that preceded it. These dynamics are well‐aligned with the observable implications of H2. Similar to our approach in H1, we include in the online appendix regression analyses where we regress the change in pre‐election to post‐coalition sentiment towards coalition and opposition parties on respondents' own vote choice (coalition and opposition). This analysis yields similar evidence in support of H2.

While our hypothesis dealt explicitly with the role of co‐governance as an affective pressure value and appears to be strongly supported, our analysis uncovers a symmetric negative pattern, in which supporters of eventual opposition parties express a significantly more negative affect towards all out‐parties (row 2) and especially towards coalition parties (row 5). The magnitude of negative affect change among opposition party supporters is equal to the positive shift among supporters of coalition parties and largely occurs between the post‐election survey and the formation of the government, pointing to the cementing of the coalition/opposition status as its likely driver, similar to our primary result here regarding coalition supporters.

Discussion and conclusions

In this paper, we contribute to the emerging comparative polarization literature by shedding light on mechanisms of post‐election decline in negative partisan emotions. Analysing novel panel data collected in Israel during a highly politically tumultuous time period, we provided evidence that self‐perceived election winners express warmer affect towards out‐partisans compared to self‐perceived election losers. This is in line with the argument within social identity theory, which predicts a lower sense of threat to translate into decreased partisan animosity. Then, we showed that people express warmer feelings towards parties that entered a coalition with their preferred party, even when this coalition is highly diverse and unexpected. This, in turn, suggests that even in highly fragmented party systems, citizens draw affective boundaries around political blocks that are broader than just their party (Kekkonen & Ylä‐Anttila, Reference Kekkonen and Ylä‐Anttila2021) – and that these boundaries are not set in stone but rather respond to elite signals in the form of co‐governance.

In terms of our research design, we were able to distinguish between the operation of these two mechanisms by leveraging unique circumstances of prolonged coalition negotiations, which separated temporally the initial formation of perceptions regarding who won the elections from the formation of a multiparty coalition government. This enabled us to show that the decrease in negative affect associated with coalition co‐membership is about double the size of that associated with being a post‐election self‐perceived winner. While the two mechanisms have distinct and substantial contributions to reducing post‐election partisan hostility, co‐governance is a substantially stronger driver of changes in affect.

The two pressure valves for negative partisan affect, winners' generosity and co‐governance, differ in their availability across political contexts. The decline in negative affect towards out‐parties among self‐perceived election winners can operate in both majoritarian and proportional electoral systems: our findings from the highly proportional Israeli context echo previous work that analysed partisan affect in the majoritarian Canadian system (Sheffer, Reference Sheffer2020). While our winners' generosity hypothesis draws theoretically on the role of electoral threat and reassurance in shaping partisan affect, we acknowledge that this divergence in affective evaluations may also be driven by broader differences in the evaluation of the political system. It is well established that electoral winners (losers) tend to express higher (lower) trust in the political system as a whole (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Klemmensen and Serritzlew2019), which may in turn translate into differences in partisan affect. Our data set does not allow us to test this mechanism, which generates the same observable implications as our preferred threat‐versus‐reassurance framework. This issue thus remains for future research on the topic.

However, the availability of the second mechanism for attenuating the negative partisan affect, that of co‐governance in multiparty coalitions, is conditioned by electoral rules (Drutman, Reference Drutman2020; Lijphart et al., Reference Lijphart1999). It is only in proportional systems that a mechanism based on multi‐party cooperation can operate. Our findings also qualify the growing emphasis in the literature on the ameliorative implications of coalition governments on affective polarization. In a recent important contribution to this body of work, Hahm et al. (Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2023) conclude that ‘coalition experience reduces both in‐group favoritism and out‐group derogation, thereby diminishing affective polarization’ (p. 14). Yet our results suggest this is only part of the story, as we documented a pattern in which opposition parties express growing resentment towards members of a new governing coalition, a negative change that is equivalent in magnitude to the improvement in sentiment observed among supporters of coalition parties. Theoretically, this fits with the argument that coalition and opposition serve as super‐ordinate political identities that once established are also likely to translate into negative affect between governing parties and their opposition (Brewer, Reference Brewer, Capozza and Brown2000; Bassan‐Nygate & Weiss, Reference Bassan‐Nygate and Weiss2022).

Next to theoretical reasons for expecting negative affect among opposition supporters towards coalition parties, there are also specific circumstances in the Israeli case that may have exacerbated this pattern. The coalition that was formed following the election we analysed above included an Islamist party, for the first time in the country's history, and this may have triggered especially intense animosity on behalf of the opposition parties. It remains for future work to examine this issue and consider how generalizable is the finding that coalition governments fuel intense negative affect among supporters of the opposition. Furthermore, scholars of partisan affect in multiparty systems should also examine whether certain types of coalition governments – for instance, majority versus minority governments, more ideologically coherent versus aisle‐crossing coalitions, and those that are comprised of a small versus large number of parties – breed more intense partisan resentment.

That being said, the normative implications are far from straightforward. On the one hand, considering that intense affective polarization corrodes the ‘social and political fabric’ (Levendusky & Stecula, Reference Levendusky and Stecula2021, 2) – it is no wonder that scholars have looked for mechanisms to diffuse out‐partisan dislike, and from this perspective co‐governance can be cast as a normatively positive process. Yet, on the other hand, affect warming through co‐governance may blur the emotional boundaries between mainstream and nativist authoritarian parties, granting them greater legitimacy alongside the obvious impacts on policy (not unlike such parties' entrance into parliaments, see, e.g. Abou‐Chadi & Krause, Reference Abou‐Chadi and Krause2020). Such radical right parties are often strongly disliked, far beyond what is expected simply based on their extreme policies (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Mendoza and Rooduijn2022). An improvement in affect towards these parties through inclusion in coalition governments is not necessarily desirable or helpful for the long‐term viability of democracies, even if it leads to lower levels of affective polarization.

The analyses above have several limitations. While we take advantage of the unique political circumstances in Israeli politics, the fact that respondents experienced four elections in 2 years (the last of which is the focus of this work) may raise questions about generalizability. This reservation becomes even more acute considering that the Israeli coalition formed during the time period covered in this study was highly idiosyncratic: it was not only highly diverse ideologically but also included an Islamist party for the first time in Israel's history. If anything, however, this setup poses a harder test for the co‐governance hypothesis we test, as it should make it harder for partisans to assume a shared governing identity with coalition parties that they are strongly opposed to on ideological and/or ethno‐nationalist grounds. That we do find such an effect under these circumstances is striking and portrays co‐governance as a promising, powerful institutional mechanism for alleviating partisan animosity – at least in the short run. As more comparative panel data regarding polarization accumulates, we hope future work delineates the scope conditions of our theoretical claims.

Acknowledgements

For their helpful comments, we thank Shir Raviv, Omer Yair, Chagai Weiss, Eelco Harteveld, Tristan Klinglehoffer, Guy Mor and participants of the annual APSA meeting 2022, the annual ISPP meeting 2022, annual EPSA meeting 2022.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Data S1

Data S2

Data S3

Data S4

Table A1: Sample Demographics.

Figure A1: Survey attrition by wave, relative to wave 8.

Table A2: Sentiment towards parties in the March 2021 Israel elections.

Table A3: Regression analysis of pre-election to post-election and post-coalition sentiment change.

Table A4: Regression analysis of outcomes of interest for H1 and H2 reported in the paper.

Figure A2: Change in out-party sentiment among self-reported election winners from before to after the election, conditional on pre-election out-party sentiment.

Figure A3: Change in out-party sentiment among self-reported election winners from before to after the election, conditional on pre-election out-party sentiment.

Table A5: Sentiment towards parties in the March 2021 Israel elections.