I. INTRODUCTION

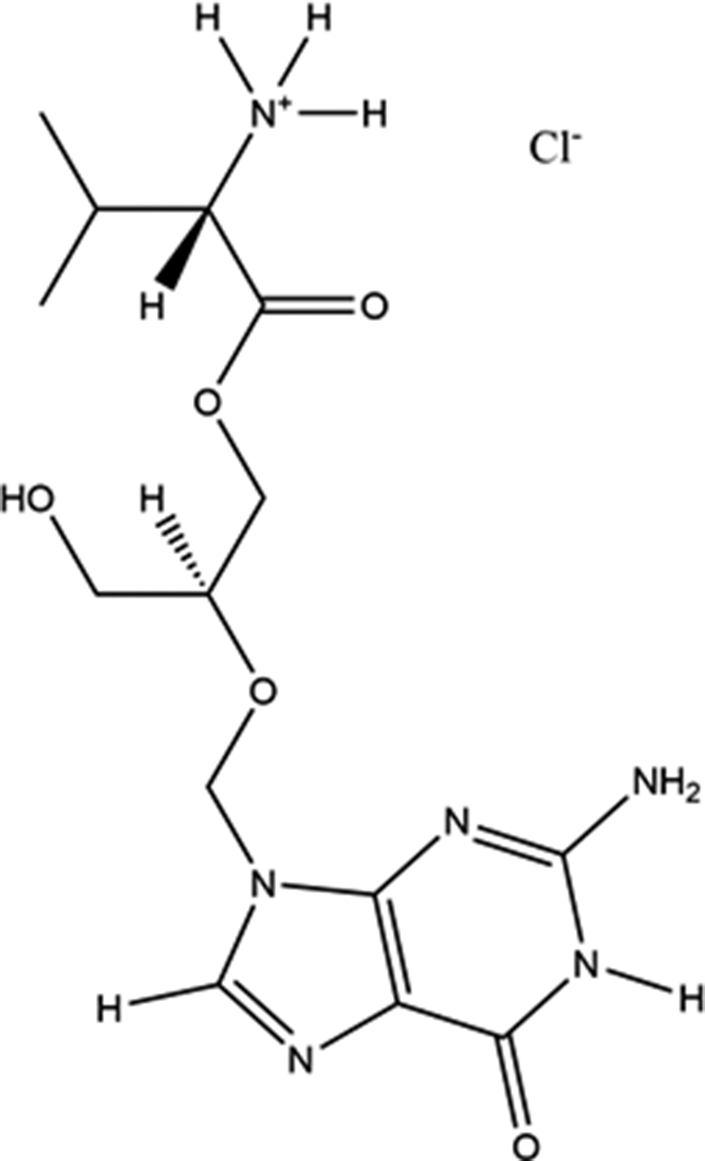

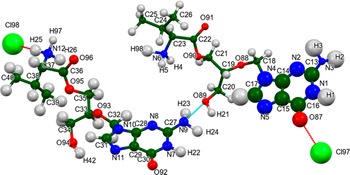

Valganciclovir hydrochloride (brand names Valcyte, Cymeval, Valcyt, Valixam, Darilin, Rovalcyte, Patheon, and Syntex) is used to treat patients with HIV/AIDS or those who have undergone organ transplant procedures who have acquired cytomegalovirus infections. Acting as an antiviral medication, Valcyte is often used in long-term treatments, as it suppresses rather than cures the infection. It is rapidly converted to ganciclovir by intestinal and hepatic esterases after oral administration. It is on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines, the safest and most effective drugs needed in a health system. The IUPAC name (CAS Registry number 175865-59-5) is [2-[(2-amino-6-oxo-1H-purin-9-yl)methoxy]-3-hydroxypropyl] (2S)-2-amino-3-methylbutanoate hydrochloride. The molecular structure of valganciclovir hydrochloride is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The molecular structure of valganciclovir hydrochloride.

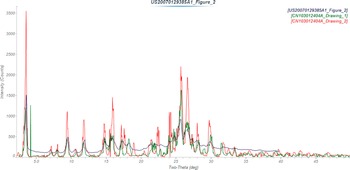

A powder pattern (monoclinic unit cell without atomic coordinates) based on a Le Bail extraction using synchrotron data is included in the Powder Diffraction File (PDF) (Kabekkodu et al., Reference Kabekkodu, Dosen and Blanton2024) as entry 00-066-1461 (Kaduk and Zhong, Reference Kaduk and Zhong2015). U.S. Patent 6083953 (Nestor et al., Reference Nestor, Womble and Maag2000; Syntex, now Roche) claims 2-(2-amino-1,6-dihydro-6-oxo-purin-9-yl)methoxy-3-hydroxy-1-propanyl-L-valinate hydrochloride in crystalline form, but no diffraction data are provided. U.S. Patent Application 2007/0129385 (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Kumar and Khanduri2007; Ranbaxy) claims amorphous valganciclovir hydrochloride, but provides a pattern of the crystalline form as Figure II of the application. Chinese Patent CN103012404A (Jin et al., Reference Jin, Li and Cheng2013) claims crystalline forms A and B of valganciclovir hydrochloride. The patterns of Form A and Form B are similar, and the poor quality of the figures makes them difficult to distinguish. The pattern of Sharma et al. (Reference Sharma, Kumar and Khanduri2007) seems most similar to that of Form A (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Comparison of the powder pattern of crystalline valganciclovir hydrochloride from U.S. Patent Application 2007/0129385 (black) (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Kumar and Khanduri2007; Ranbaxy) and Forms A (green) and B (red) from Chinese Patent CN103012404A (Jin et al., Reference Jin, Li and Cheng2013). The published patterns (measured using Cu Kα radiation) were digitized using UN-SCAN-IT (Silk Scientific, 2013) and plotted using MDI JADE Pro (MDI, 2025).

This work was carried out as part of a project (Kaduk et al., Reference Kaduk, Crowder, Zhong, Fawcett and Suchomel2014) to determine the crystal structures of large-volume commercial pharmaceuticals and include high-quality powder diffraction data for these pharmaceuticals in the PDF.

II. EXPERIMENTAL

The sample was a commercial reagent, purchased from AK Scientific, Inc. (Catalogue #N012) and was used as received. This was a different sample than that used to prepare PDF entry 00-066-1461. The white powder was packed into a 1.5-mm-diameter Kapton capillary and rotated during the measurement at ~50 Hz. The powder pattern was measured at 295 K at beam line 11-BM (Antao et al., Reference Antao, Hassan, Wang, Lee and Toby2008; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Shu, Ramanathan, Preissner, Wang, Beno and Von Dreele2008; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Toby, Lee, Ribaud, Antao, Kurtz, Ramanathan, Von Dreele and Beno2008) of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory using a wavelength of 0.413891(2) Å from 0.5° to 50° 2θ, with a step size of 0.001° and a counting time of 0.1 seconds per step.

The original pattern used to generate PDF entry 00-066-1461 was indexed (after manual peak picking) using JADE Pro (MDI, 2024), but no successful structure solution could be obtained in this monoclinic unit cell. Using this new dataset, the peaks were located by interactive profile fitting in JADE Pro. The pattern was indexed on a primitive orthorhombic unit cell with a = 7.075, b = 11.347, c = 49.342 Å, V = 3,961 Å3, and Z = 8 using DICVOL14 (Louër and Boultif, Reference Louër and Boultif2014). Analysis of the systematic absences using EXPO2014 (Altomare et al., Reference Altomare, Cuocci, Giacovazzo, Moliterni, Rizzi, Corriero and Falcicchio2013) suggested the space group P212121. A reduced cell search in the Cambridge Structural Database (Groom et al., Reference Groom, Bruno, Lightfoot and Ward2016) yielded 11 hits, but no structures for valganciclovir derivatives.

A neutral valganciclovir molecule was built using Spartan‘24 (Wavefunction, 2023), and converted into .mol2 and .mop files using OpenBabel (O’Boyle et al., Reference O’Boyle, Banck, James, Morley, Vandermeersch and Hutchison2011). The minimum-energy conformation of the molecule was more compact (folded on itself) than would be expected in the solid state, so the conformation was manually adjusted using Materials Studio (Dassault Systèmes, 2024). The structural model was obtained by parallel tempering techniques using FOX (Favre-Nicolin and Černý, Reference Favre-Nicolin and Černý2002), using two valganciclovir molecules and two Cl atoms as fragments. Given the extreme anisotropy of the lattice parameters, a <001> preferred orientation coefficient was included in the optimization. The closest N atoms to the Cl anions were N6 and N12 of the valine side chains, indicating that the protonation occurred at these two atoms. Initial and intermediate solutions and refinements were plagued by partial overlap of one of the two independent valganciclovir cations. Comparing the two cations using Mercury (Macrae et al., Reference Macrae, Sovago, Cottrell, Galek, McCabe, Pidcock and Platings2020) indicated that the best agreement was obtained by invoking both the inversion and flexibility options in Molecule Overlay. Each cation contains two asymmetric carbon atoms. The stereochemistry about C19/C23 was S/R, and that about C33/C37 was R/R (S – sinister, left or counterclockwise; R – rectus, right or clockwise). The closest contacts were within molecule 1 (the lower atom numbers). Downloading the valganciclovir molecule Conformer_3D_CID_135413535.sdf from PubChem shows that the correct stereochemistry is S/S. Thus, we had been using the wrong enantiomer (R/R), which could not be distinguished from S/S using powder data. The default flexibility option in FOX provides enough flexibility that occasionally the chirality of a carbon atom can be inverted. (This can be changed by a program setting.) The area of the “mixed” stereochemistry was where the partial molecular overlap occurred. The chirality of C19 was inverted manually using Materials Studio, and then the entire structure was inverted using GSAS-II (Toby and Von Dreele, Reference Toby and Von Dreele2013). The structure was optimized using the Forcite module of Materials Studio, and then a Rietveld refinement was begun. The refinement yielded some close intermolecular contacts (we suspected because of preferred orientation), so a density functional geometry optimization was carried out. A refinement was begun using the results of that optimization.

A reviewer of the previous version of this paper pointed out that the sample was sold as a mixture of diastereomers and that the stereochemistry about C19/C33 was mixed. The refinement was trying to tell us that, but we did not listen. Accordingly, the refinement was restarted with molecule 1 having C19 R and C23 S, and molecule 2 having C33 S and C37 R.

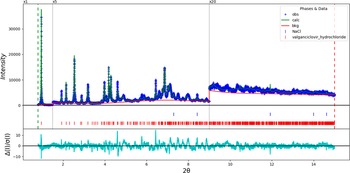

Rietveld refinement was carried out using GSAS-II (Toby and Von Dreele, Reference Toby and Von Dreele2013). Only the 0.8°–15.00° portion of the pattern was included in the refinement (d min = 1.585 Å). All non-H-bond distances and angles were subjected to restraints, based on a Mercury/Mogul Geometry Check (Bruno et al., Reference Bruno, Cole, Kessler, Luo, Motherwell, Purkis and Smith2004; Sykes et al., Reference Sykes, McCabe, Allen, Battle, Bruno and Wood2011) of the molecule. The Mogul average and standard deviation for each quantity were used as the restraint parameters. The purine ring systems were restrained to be planar. The restraints contributed 9.5% to the final χ 2. The hydrogen atoms were included in calculated positions, which were recalculated during the refinement using Materials Studio (Dassault Systèmes, 2024). One U iso was refined for the heavy atoms of the ring system, another for the heavy atoms of the side chains, and a third for the Cl. A few U iso refined to slightly negative values, so they were fixed at reasonable values. The background was modeled using a six-term shifted Chebyshev polynomial, along with one peak at 6.59° to model the scattering from the Kapton capillary and the amorphous component of the sample. The peak profiles were described using the generalized microstrain model (Stephens, Reference Stephens1999), and a fourth-order spherical harmonic preferred orientation model was included. A NaCl impurity was observed to be present; its concentration was refined to 0.29(2) wt%.

The final refinement of 182 variables using 14,201 observations and 126 restraints yielded the residuals R wp = 0.12090 and GOF = 2.09. The largest peak (1.49 Å from N1) and hole (1.24 Å from N5) in the difference Fourier map were 0.26(7) and −0.22(7) eÅ−3, respectively. The largest errors in the fit (Figure 3) are at the 002 peak at 0.96°, the 024 peak at 4.60°, and the 033 peak at 6.44°. The errors suggest that the preferred orientation has not been modeled completely and/or that the sample exhibits some granularity.

Figure 3. The Rietveld plot for the refinement of valganciclovir hydrochloride. The blue crosses represent the observed data points, and the green line is the calculated pattern. The cyan curve is the normalized error plot. The row of red tick marks indicates the peak positions of valganciclovir hydrochloride, and the blue tick marks indicate the NaCl peak positions. The vertical scale has been multiplied by a factor of 5× for 2θ > 1.5̊, and by a factor of 20× for 2θ > 8.7̊.

The crystal structure of valganciclovir hydrochloride was optimized (fixed experimental unit cell) with density functional techniques using VASP (Kresse and Furthmüller, Reference Kresse and Furthmüller1996) through the MedeA graphical interface (Materials Design, 2024). The calculation was carried out on 32 cores of a 144-core (768 GB memory) HPE Superdome Flex 280 Linux server at North Central College. The calculation used the GGA-PBE functional, a plane-wave cutoff energy of 400.0 eV, and a k-point spacing of 0.5 Å−1, leading to a 2 × 2 × 1 mesh, and took ~27.5 days. Single-point density functional theory calculations (fixed experimental cell) and population analysis were carried out using CRYSTAL23 (Erba et al., Reference Erba, Desmarais, Casassa, Civalleri, Donà, Bush and Searle2023). The basis sets for the H, C, and O atoms were those of Gatti et al. (Reference Gatti, Saunders and Roetti1994), and the basis set for Cl was that of Peintinger et al. (Reference Peintinger, Vilela Oliveira and Bredow2013). The calculations were run on a 3.5 GHz PC using eight k-points and the B3LYP functional, and took ∼6.1 hours.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The synchrotron powder pattern of this study matches those of Sharma et al. (Reference Sharma, Kumar and Khanduri2007) and Jin et al. (Reference Jin, Li and Cheng2013) well enough (Figure 4) to conclude that all three samples contain the same crystalline phase, and thus that this pattern is representative of material in commerce. The background contains contributions in addition to that from the Kapton capillary, indicating that this sample is only partially crystalline.

Figure 4. Comparison of the synchrotron pattern (black) of valganciclovir hydrochloride to the pattern reported by Sharma et al. (Reference Sharma, Kumar and Khanduri2007) (red) and Form A reported by Jin et al. (Reference Jin, Li and Cheng2013) (green). The published patterns were digitized using UN-SCAN-IT (Silk Scientific, 2013) and scaled to the synchrotron wavelength of 0.413891 Å using MDI JADE Pro (MDI, 2019).

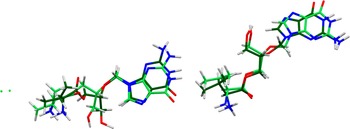

The refined atom coordinates of valganciclovir hydrochloride and the coordinates from the DFT optimization are reported in the Crystallographic Information Frameworks attached as the Supplementary Material. The root-mean-square (rms) difference of the non-H atoms in the Rietveld-refined and VASP-optimized structures, calculated using the Mercury CSD-Materials/Search/Crystal Packing Similarity tool, is 0.895 Å (Figure 5). The rms Cartesian displacements of the non-H atoms in the Rietveld-refined and VASP-optimized structures of the two cations, calculated using the Mercury Calculate/Molecule Overlay tool, are 0.763 and 0.522 Å (Figures 6 and 7). The absolute position differences of Cl97 and Cl98 are 0.879 and 1.089 Å. The agreements are outside of the normal range expected for correct structures (van de Streek and Neumann, Reference van de Streek and Neumann2014). The limited data range, the relatively large structure, the broad peaks, the relatively low crystallinity, and the significant preferred orientation all affect the Rietveld refinement, making the refined structure less accurate than usual. This discussion concentrates on the DFT-optimized structure. The asymmetric unit (with atom numbering) is illustrated in Figure 8, and the crystal structure is presented in Figure 9.

Figure 5. Comparison of the CRYSTAL23-optimized structure of valganciclovir hydrochloride (colored by atom type) to the VASP-optimized structure (green). The comparison was generated by the Mercury CSD-Materials/Search/Crystal Packing Similarity tool; the root-mean-square displacement is 0.895 Å. Image generated using Mercury (Macrae et al., Reference Macrae, Sovago, Cottrell, Galek, McCabe, Pidcock and Platings2020).

Figure 6. Comparison of the Rietveld-refined (red) and VASP-optimized (blue) structures of cation 1 of valganciclovir hydrochloride. The root-mean-square Cartesian displacement is 0.664 Å.

Figure 7. Comparison of the Rietveld-refined (red) and VASP-optimized (blue) structures of cation 2 of valganciclovir hydrochloride. The root-mean-square Cartesian displacement is 0.668 Å.

Figure 8. The asymmetric unit of valganciclovir hydrochloride, with the atom numbering. The atoms are represented by 50% probability spheroids.

Figure 9. The crystal structure of valganciclovir hydrochloride, viewed down the b-axis. Image generated using Diamond (Crystal Impact, 2023).

The crystal structure (Figure 9) is dominated by alternating layers of ring systems and protonated side chains/anions along the c-axis. In addition to the ammonium–Cl hydrogen bonds, the ring systems and side chains are linked into double layers in the bc-plane by hydrogen bonds. The mean plane of the purine ring system in cation 1 is approximately (10, 1, 5), and that in cation 2 is (6, −1, 2). These rings stack along the a-axis, and the distance between the centroids of the adjacent ring systems is 3.69 Å. As expected for diastereomers, the two independent cations have very different conformations (Figure 10). The rms Cartesian displacement is 1.725 Å.

Figure 10. Comparison of the two cations in valganciclovir hydrochloride. Cation 1 is in green, and cation 2 is in orange.

Almost all of the bond distances, angles, and torsion angles fall within the normal ranges indicated by a Mercury Mogul Geometry check (Macrae et al., Reference Macrae, Sovago, Cottrell, Galek, McCabe, Pidcock and Platings2020). In cation 1, the C38–C37–C36 angle of 117.0° (average = 113.1(13)°; Z-score = 3.1) is flagged as unusual. The uncertainty on the average is small, inflating the Z-score. Torsion angles involving rotation about the C18–N4, O88–C19, C22–C23, C35–C33, and C36–C37 bonds lie on the tails of distributions of similar torsion angles. Torsion angles involving C32–N10 are unusual, so the conformation of cation 2 is unusual, while cation 1 is unusual but not unprecedented.

Quantum chemical geometry optimization of the valganciclovir cations (DFT/B3LYP/6-31G*/water) using Spartan‘24 (Wavefunction, 2023) indicated that the observed solid-state conformation of cation 1 is 18.8 kcal/mole higher in energy than the local minimum (Figure 11). The rms Cartesian displacement between the two structures is 1.551 Å. The observed solid-state conformation of cation 2 is 14.7 kcal/mole higher in energy than the local minimum (Figure 12). The rms Cartesian displacement between the two structures is 1.276 Å. The local minimum of cation 2 (SR) is 0.8 kcal/mole lower in energy than that of cation 1 (SS). The energy difference is within the expected uncertainty of such calculations, so the two diastereomers are equivalent in energy. Molecular mechanics conformational analysis indicated that the minimum-energy conformation is much more compact than the observed ones. The ammonium group on the valine side chains folds toward the ring system, forming N–H···N and N–H···O hydrogen bonds. Intermolecular interactions are thus important in determining the observed conformations.

Figure 11. Comparison of the observed (green) and DFT-optimized local minimum (orange) conformations of cation 1 in valganciclovir hydrochloride.

Figure 12. Comparison of the observed (green) and DFT-optimized local minimum (orange) conformations of cation 2 in valganciclovir hydrochloride.

Analysis of the contributions to the total crystal energy using the Forcite module of Materials Studio (Dassault Systèmes, 2024) suggests that angle distortion terms dominate the intramolecular deformation energy, as might be expected in a fused-ring system. The intermolecular energy is dominated by electrostatic attractions, which in this force-field-based analysis include cation coordination and hydrogen bonds. The hydrogen bonds are better analyzed using the results of the DFT calculation.

Hydrogen bonds are important in the crystal structure (Table I). As expected, each protonated ammonium group makes at least one N–H···Cl hydrogen bond to an anion. Each ammonium group also makes at least one N–H···O hydrogen bond. The energies of the N–H···O hydrogen bonds were calculated using the correlation of Wheatley and Kaduk (Reference Wheatley and Kaduk2019). The hydroxyl groups O89 and O94 participate in O–H···N and O–H···Cl hydrogen bonds. The energy of the O–H···O hydrogen bond was calculated using the correlation of Rammohan and Kaduk (Reference Rammohan and Kaduk2018), and the energy of the O–H···Cl hydrogen bond was calculated according to the correlation of Kaduk (Reference Kaduk2002). The amino group N3 acts as a donor to both O94 and Cl98, whereas the amino group N9 acts as a donor to O91 and O92. The ring nitrogen atom N1 participates in a N–H···O hydrogen bond. There are a surprising number of C–H···Cl, C–H···O, and C–H···N hydrogen bonds, involving methyl, methylene, and methyne groups, as well as ring C–H bonds. Although individually probably weak, in sum, they contribute significantly to the crystal energy.

TABLE I. Hydrogen bonds (CRYSTAL23) in valganciclovir hydrochloride.

* Intramolecular.

The volume enclosed by the Hirshfeld surface (Figure 13; Hirshfeld, Reference Hirshfeld1977; Spackman et al., Reference Spackman, Turner, McKinnon, Wolff, Grimwood, Jayatilaka and Spackman2021) is 974.07 Å3, 98.41% of one-fourth of the unit-cell volume. The packing density is thus fairly typical. All of the significant close contacts (red in Figure 13) involve the hydrogen bonds. The volume/non-hydrogen atom is slightly larger than usual at 19.0 Å3.

Figure 13. The Hirshfeld surface of valganciclovir hydrochloride. Intermolecular contacts longer than the sum of the van der Waals radii are colored blue, and contacts shorter than the sum of the radii are colored red. Contacts equal to the sum of the radii are white.

The Bravais–Friedel–Donnay–Harker (Bravais, Reference Bravais1866; Friedel, Reference Friedel1907; Donnay and Harker, Reference Donnay and Harker1937) morphology suggests that we might expect platy morphology for valganciclovir hydrochloride, with {001} as the principal faces. A fourth-order spherical harmonic model for preferred orientation was incorporated into the refinement. The texture index was 1.211(9), indicating that preferred orientation was significant, even in this rotated capillary specimen. The powder pattern of valganciclovir hydrochloride from this synchrotron dataset is included in the PDF as entry 00-071-1641 to replace entry 00-066-1461.

DEPOSITED DATA

The Crystallographic Information Framework (CIF) files containing the results of the Rietveld refinement (including the raw data) and the DFT geometry optimization were deposited with the ICDD. The data can be requested at pdj@icdd.com.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0885715625101073.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Lynn Ribaud and Saul Lapidus for their assistance in the data collection.

FUNDING STATEMENT

Use of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. This work was partially supported by the International Centre for Diffraction Data.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors have no competing interests.