In November 1567, the Venetian nobleman Francesco Pisani died at his beloved villa in Montagnana, fifty miles southwest of Venice, deep in the Republic’s mainland territories. The villa house, designed by the architect Andrea Palladio (1508–80) in 1552, was the centerpiece of an extensive agricultural estate that formed the substance of Francesco’s legacy to his heirs (Figs 1 and 2). His family soon discovered that, several months earlier, he had written a new will, in which he disinherited Marietta da Molin, his wife of over thirty years. He instead placed the estate in the hands of a young Pisani cousin who shared his name. Francesco begged Marietta’s forgiveness for the “scant fondness” (poco amorevolezza) his will appeared to show her and left her income from two of his farms as compensation.1

1. Andrea Palladio, Villa Pisani, Montagnana, exterior from the southwest, 1553–54.

2. Andrea Palladio, Villa Pisani, Montagnana, exterior from the northwest, 1553–54.

By spring 1568, emotions still ran high. Marietta had refused to accept her lot and moved against the Pisani heirs, claiming a third farm from the estate. Francesco’s first cousin Zuan Mattio (Giovanni Matteo) Pisani, father of the young beneficiary, was incensed and went on to accuse her of stealing a prized possession of the deceased, the magnificent oil painting by Paolo Veronese, The Family of Darius before Alexander (Fig. 3).2 An order from a Venetian court dated May 11, 1568 confirms that Marietta had retained the “painting with the history of Alexander the Great, [which is] of the greatest value and price.”3 Veronese’s canvas, a recent commission by the Pisani couple, had hung in the Montagnana villa.

3. Paolo Veronese, The Family of Darius before Alexander, ca. 1565–67. London, The National Gallery.

Nothing better revealed Marietta’s false claims, Zuan Mattio asserted four days later, than “her machinations” to remove that “most precious picture” and even its iron supports from the house in Montagnana. “One sees clearly that she wants to make herself mistress [padrona] of all these properties.” For Zuan Mattio, the painting, which showed Alexander granting clemency to the family of his defeated foe, the Persian king Darius, stood in for the Pisani’s entire mainland patrimony.4

What was such a valuable possession doing in Francesco Pisani’s villa, two days’ travel from Venice? A large oil painting like the Family of Darius would have graced the portego, or main reception hall, of a Venetian family palace. Cycles of paintings in the cheaper medium of fresco typically covered the walls of the country house. Keeping the canvas in Montagnana rather than Venice elucidates the status of the building in which it was hung. As this book argues, its owner considered the villa his family palace and chief residence.

* * *

We might rightly ask: Can a villa be a palace? Palladio’s Villa Pisani at Montagnana (built 1553–54) calls into question the accepted typology – and hierarchy – of domestic architecture in the Italian Renaissance: palace and villa, city house and country house. It also asks us to look beyond typology as a method of analysis to consider other questions. For whom can a villa be a palace? In what ways? And where?

Architecturally, this building confounds conventional distinctions between a country house and a town house, and the hybrid form Palladio chose was related to the suburban character of its site, to the patron’s life divided between Venice and the mainland, and to his patrimonial and territorial ambitions. This case study invites us to think of the villa not merely as a country house subsidiary to the “main” family residence, but rather as its counterpart and sometimes its replacement. Palladio gave architectural expression to a way of living in which the villa played a fundamental role.5

Defining the Villa

The villa holds an ambiguous position in the historiography of early modern architecture in Italy. Historians recognize it as a novel secular building type and important locus of patronage from the fifteenth century on. Yet, by its very definition, it is marginal to the city, and therefore to the centers of architectural and artistic production that have dominated traditional narratives about Renaissance Italy.6 The villa has generally been understood as a residence situated outside the city, used as a pleasure retreat and “second home” by the urban elite. Sometimes it incorporated farm functions, most famously in the villas of the north Italian Veneto region designed by Andrea Palladio. Architectural historians have interpreted the Renaissance villa, moreover, as the expression of humanist ideals of country life resuscitated from ancient Roman literature, which was rich with tropes about the pleasurable escape from urban society and the moral virtues of agriculture.7 Yet early modern country houses, which can range from a castle to a rustic villa-farm to a sophisticated suburban garden, have defied easy classification and resisted the formulation of a consistent formal typology.8

The last decades have produced a rich array of English-language studies of the social history and meanings of the early modern villa. David Coffin’s pioneering study of 1979 set aside formal questions, using archival and other written sources to enrich our picture of villeggiatura, or country living, in papal Rome.9 Important subsequent studies, including James Ackerman’s magisterial volume of 1990, exposed the inherently ideological role of the villa as a site of elite privilege and power: in Bentmann and Müller’s words, the architecture of hegemony.10 More recently, scholars have offered important correctives to earlier interpretations of the villa as secular, apolitical, and wholly separate from the city.11 Tracy Ehrlich argued that the early seventeenth-century Villa Borghese at Frascati was not an escape but actively “articulated” and “helped to shape the Roman social and political order” under Pope Paul V.12 In fifteenth-century Florence, Amanda Lillie has shown, country and city “were the two interdependent halves of a single social and economic world.”13 Here I make a parallel case for a third significant period and region associated with early modern villa culture: the Veneto of Andrea Palladio.

As difficult as it has been to define what the villa is, what it is not has rarely been in doubt. Modern scholarship inherited a dual typology, set forth in the texts of Vitruvius, Alberti, and Palladio himself, that placed the country house and the city house in distinct categories. Scholars have read the Renaissance palazzo (the palace or town house), like the ancient Roman domus, as the primary residence and family seat, the center of family representation. Venetian patricians like Francesco Pisani eschewed the term palazzo, but their “case” (houses) are likewise interpreted as the embodiment of the family.14 In contrast, the villa is understood to be secondary. As Ackerman put it, it is a “satellite,” which “exists not to fulfill autonomous functions but to provide a counterbalance to urban values and accommodations” – that is, to the palace.15

The central case study of my investigation, Palladio’s Villa Pisani at Montagnana, challenges the interpretation of the villa as a second home and a satellite to the city. The origins of the early modern villa may be rooted in ancient Roman culture, but villas of antiquity never usurped the primary role of the owner’s urban domus in defining his social identity.16 For Francesco Pisani, however, a villa could serve as a palace.

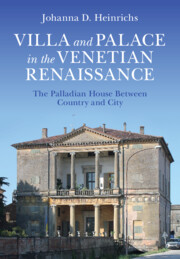

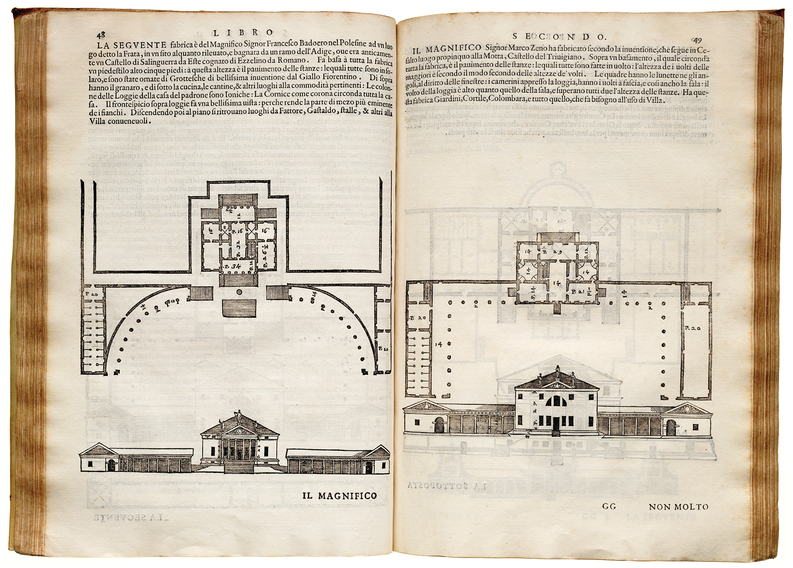

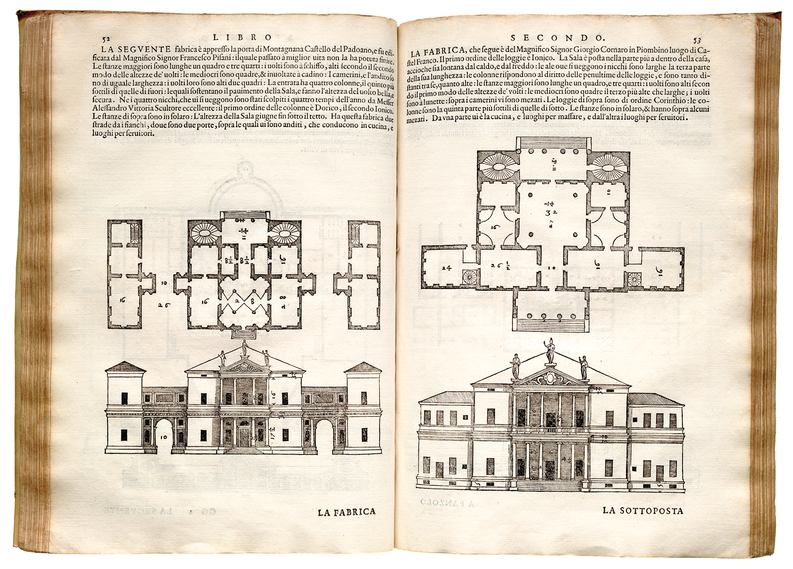

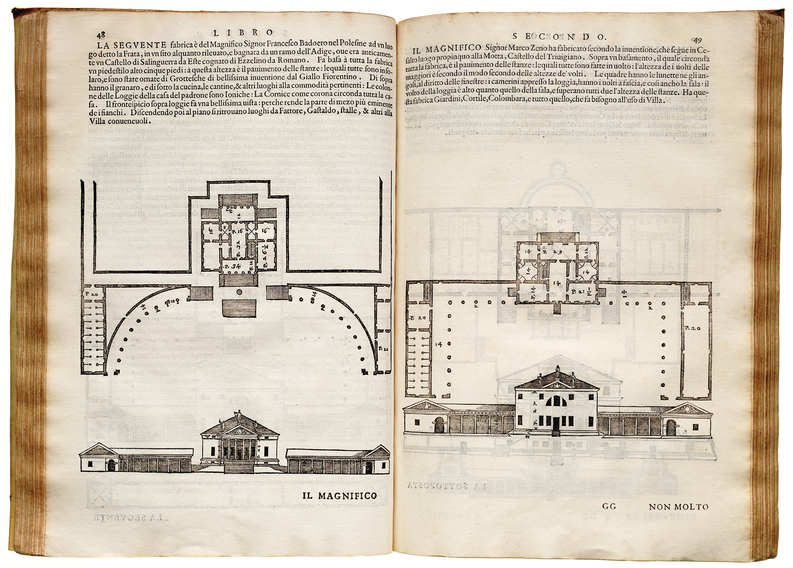

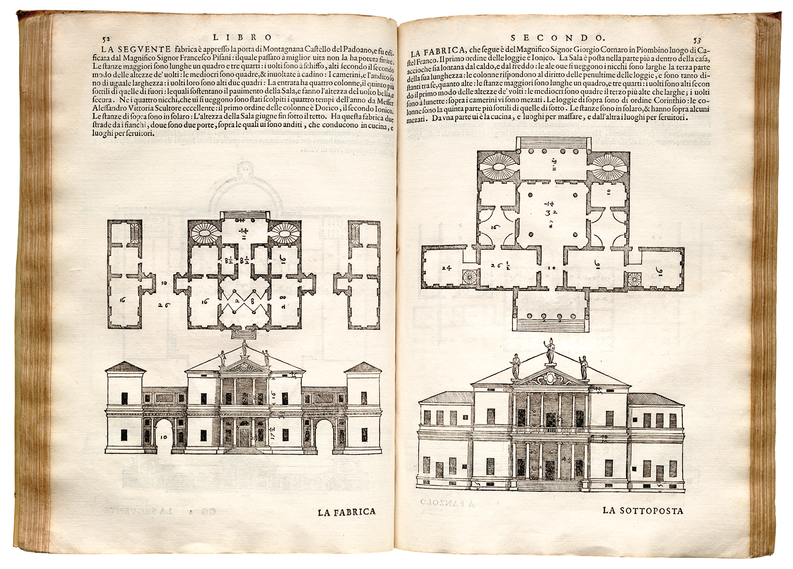

Palladio’s Villas

In separate chapters of book two of I quattro libri dell’architettura (The Four Books on Architecture), his influential treatise published in 1570, Palladio served up to readers his designs for case di città and case di villa, city houses and houses on a country estate. In this division, he followed his predecessor Leon Battista Alberti and the Roman architect Vitruvius, authors of, respectively, the first modern theoretical text on architecture and the only surviving ancient treatise.17 Palladio’s first five villa designs in book two, all for Venetian rather than mainland patrons, include some of Palladio’s best-known villas: Villa Badoer at Fratta Polesine, Villa Foscari (La Malcontenta) at Gambarare di Mira, and Villa Barbaro at Maser, all dating to the mid-1550s. Together they suggest to the reader that a country house should have one main living floor and a pedimented columnar portico, or temple front, on the main façade. Four of the five also display a forecourt or lateral extensions composed of barchesse, colonnaded or arcaded dependencies, to serve the family and the farm (Fig. 4). This is the classic Palladian villa type. As we turn the pages, however, we soon encounter a variant. The elevations of Villa Pisani at Montagnana and Villa Cornaro at Piombino Dese both show a two-story block, with a double portico (two superimposed sets of columns) on both front and back, and no forecourt (Fig. 5). Although both houses have lateral wings, they lack the portico-barchesse of the first few designs. This more compact scheme recalls an example from Palladio’s earlier chapter on city houses, which he opened with a nearly identical design, for Palazzo Antonini in Udine (see Fig. 20). By drawing our attention back to the palace projects, the images for Villa Pisani and Villa Cornaro dismantle the apparent distinctions established by book two’s typological structure. While the treatise aimed for clarity and consistency, nuances and even contradictions emerge in some projects.

4. Andrea Palladio, Villa Badoer at Fratta Polesine and Villa Zeno at Cessalto, from I quattro libri dell’architettura, 1570.

5. Andrea Palladio, Villa Pisani at Montagnana and Villa Cornaro at Piombino Dese, from I quattro libri dell’architettura, 1570.

Villa Pisani looks like a palace, but it also bears features of a villa. Its hybrid character – a closed, palatial street front and a garden front marked by open loggias – draws attention to the fluidity of Palladio’s approach to domestic architecture. The architect’s deliberate mixing of forms and types in Villa Pisani (as projected in the treatise and as built) points to his subtle reading of the house’s site just outside the walls of Montagnana. It also speaks to his sense of decorum, the appropriateness of the design to its owner, for Palladio would have understood not only the patron’s social status but also his particular living situation and the messages he wanted his house to communicate.

Many studies of Palladio’s work follow the typological structure of the treatise and group the villas together to catalogue his development and ingenuity as a designer.18 The villas appear as original, gem-like creations comparable only to one another. For his patrons, however, the villa was not an abstract design solution but a place for living. Grounded in extensive archival documentation, much of it newly discovered or reinterpreted, this book reconstructs Villa Pisani as a “social space,” to borrow Henri Lefebvre’s term.19 Resembling, by turns, a palace and a villa, it served as a collection point for part of the estate’s agricultural yield as well as a place of business, sociability, spiritual devotion, and, above all, representation. The microhistory of Villa Pisani illuminates Palladio’s villas as lived spaces for real people.20 At the same time, because it never reached completion according to the scheme published in the Four Books, Villa Pisani sheds light on the rarely straightforward relationship between Palladio’s building practice and his written theory.

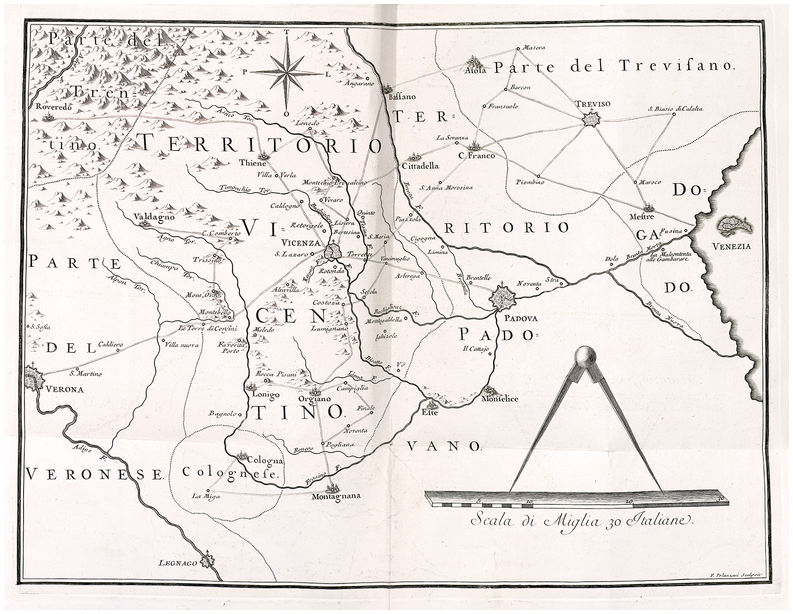

The Villa and the Venetian State

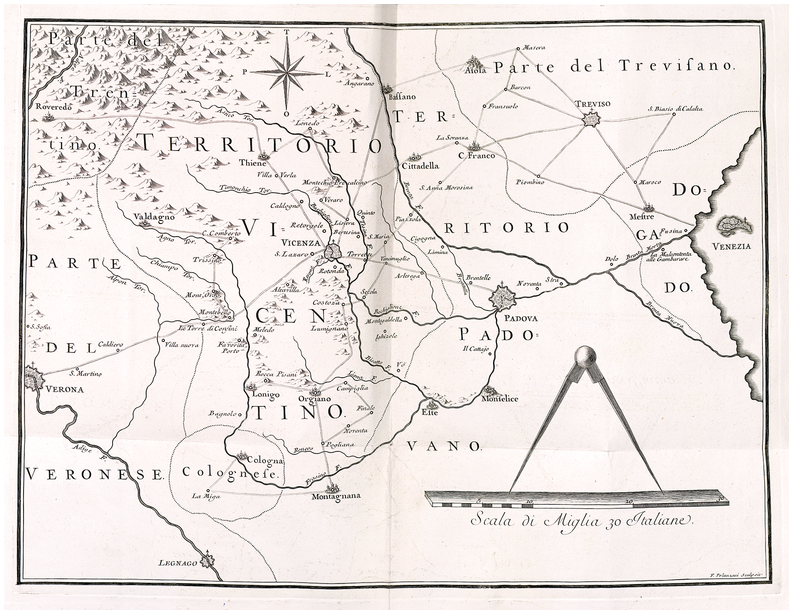

Why did Venetians build villas? The long-standing seaward orientation of Venice’s economy and society – not to mention its emphatically urban character – raises the question of the status of the countryside in the Venetian world.21 Starting in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, the Republic came to control an extensive mainland territory, the stato da terra, as a colonial power. Venetian patricians and citizens began to acquire landed estates on a large scale following the annexation of important terraferma cities such as Treviso, Padua, Vicenza, and Verona and their rural territories (Fig. 6).22 A combination of economic, cultural, and social factors turned Venice’s mercantile patriciate to the land. The greater security of land investment compared to the increasing uncertainties of maritime trade, coupled with the Republic’s need to secure its grain supply, made a powerful economic case for buying land. Recuperation of Roman republican ideals of country life and the prestige attached to land ownership further enhanced its appeal and spurred a burgeoning villa culture among the Venetian elite.23

6. Map of the Venetian terraferma with Palladian building sites, from Francesco Muttoni, Architettura di Andrea Palladio, vol. 1, 1740.

In 1509, the Serenissima nearly lost its mainland state as the major European powers united to reverse a century of aggressive Venetian expansion in northeast Italy. The War of the League of Cambrai halted Venetian investments, but only temporarily, as the state regained most of its former territories by 1517.24 During the sixteenth century, rising grain prices caused by population pressure and, after mid-century, large-scale drainage and irrigation projects sponsored by the Venetian state would further increase the value of land. The present work charts Venice's intensifying engagement with the terraferma not through this geopolitical lens but rather through the story of one family and their villa. For some Venetian families such as the Pisani, as for the fifteenth-century Florentines examined by Lillie, mainland and metropolis had become two halves of one world.25 As the Republic tightened its grip on subject cities following the war, city and state also grew more closely knit through the living arrangements and investment strategies of Venice’s elite.

Situated far from Venice but at the edge of an important mainland town, Villa Pisani belonged to a social, cultural, and political geography that spanned the lagoon city of Venice and its territorial state.26 I argue that for Francesco Pisani, as for other Venetian patricians who commissioned Palladio’s best-known villas, the villa served as a key node within a system of multiple residences. Neither a singular gem nor a satellite, the Palladian villa belonged integrally to a crown or constellation of properties. Pisani’s house at Montagnana served as his primary residence but was linked through his regular movements to a second, “stop-over” villa in the town of Monselice and to Venice, where he dwelled in rented accommodations. Other Palladio patrons built up even more complex portfolios. Their villas should be understood in relation to their other residences, as part of a family’s spatial footprint. Francesco Pisani and his homes tell a story of mobility and multiplicity, not the dualisms of center and periphery that have shaped discourse on the Renaissance villa.

The diarist Girolamo Priuli blamed Venice’s devastating losses in 1509 on its abandonment of the sea, the historic source of its wealth and honor. He famously portrayed the mainland state as a debilitating intoxication to his countrymen.27 Wealthy patricians and citizens wanted to “triumph and live and give themselves over to pleasure and delight and the green of the terraferma.” Relinquishing maritime trade, they spent money instead. Buying land led to building palaces; palaces, in turn, meant furniture, carriages, and horses.28 Priuli’s critique of the mercantile patriciate gone soft is a well-worn trope of the historiography, and recent scholarship has challenged the extreme view he promoted that Venetian nobles had abandoned their seafaring enterprises to embrace the aristocratic mentality of the rentier. Economic historians now stress the legitimate financial, ideological, and familial reasons for land investment. They have shown how Venetian and mainland nobles continued to engage in trade while taking an active role in land management and industrial enterprises on the terraferma.29

Embittered though it may be, Priuli’s narrative does correspond in its basic outline to the trajectory of the Pisani family. Francesco Pisani’s grandfather Francesco di Almorò Pisani dal Banco had purchased the nucleus of what became the Montagnana estate in 1487. He maintained his mercantile activity, investing in the Flanders galley rounds in the same year. His son Zuanne, however, never engaged in commerce (“ne mai … ha fato mercantie,” as his wife asserted in a 1524 tax document), choosing instead to augment and improve his mainland inheritance near Montagnana, especially after the end of the war.30 The grandson would follow this path as he too added farms and acreage to the estate and eventually constructed the new suburban villa-palace designed by Palladio. Francesco Pisani even got himself a horse and carriage, not to mention a second villa. Far from giving himself over to the villa pleasures that Priuli scorned, however, Pisani worked to consolidate his properties, manage his estate, make loans, and collect rents. Having inherited a country estate but no ancestral home in Venice, he made the Montagnana villa his family seat. And in the upper-floor sala, or reception hall, he installed the great Alexander canvas, showcasing that exemplar of the vita activa on the walls of his primary residence.

* * *

In this book, I approach Villa Pisani from a variety of angles, to understand its architecture in its physical setting, in the social and political context of Montagnana and the Venetian territorial state, and according to the lived experience of and meanings it held for its owners. Part I: Villa and Palace introduces the villa and its patron and the central argument of the book. The first chapter analyzes Palladio’s design for Villa Pisani in relation to Renaissance theoretical discourse, Veneto building practice, and the architect’s own written and built works. It argues that Villa Pisani’s hybrid architecture reflected the mixed urban-rural nature of its site and can be linked to Alberti’s conception of the suburban residence (hortus suburbanus). The hybrid form was also related to use and meaning. Chapter 2 trains a biographical lens on Francesco Pisani, who was a patron of major Veneto artists, including Alessandro Vittoria (1525–1608), in addition to Palladio and Veronese. An investigation of where and how Pisani lived in his native city of Venice – as well as his political career and family affairs – clarifies the reasons for his investment in the mainland estate. Chapter 3 returns to Montagnana to examine the lived spaces of Villa Pisani. It focuses on four key sites – farm court, entrance hall, sala, and chapel – and draws on archival evidence to bring these spaces to life. Both palace and villa, this building served Pisani and his family throughout the year as a locus of otium and negotium (leisure and business), as well as familial display.

Villas rarely existed in idyllic isolation. Part II: Territory and Town re-situates Villa Pisani in its local and its territorial contexts. Chapter 4 traces the gradual entrenchment of the Pisani family in the Bassa Padovana region, showing that the villa house was more than an occasional residence and formed part of a long-term strategy of estate-building. Francesco Pisani’s construction of his Palladian villa just outside the principal gate of Montagnana culminated a multi-generational process. Chapter 5 turns to the town of Montagnana to probe its identity as a small but significant urban center, the character of the suburban district where Villa Pisani was built, and the role of civic benefactor that Pisani cultivated for himself. In Chapter 6, we chart Pisani’s expanding spatial footprint as he built a second house, which I call a “stop-over villa,” on the route between Venice and Montagnana. Mobility becomes the key term as we explore the concept of a “residential system” defined by the owner’s frequent movement. This chapter shows that Francesco Pisani was not alone in devising a system of multiple residences, nor in making his mainland villa the chief family seat.

Part III: The Villa in Time investigates the status of Palladio’s unrealized project for Villa Pisani and its afterlife. As he published it in the Four Books of 1570, Palladio extended the villa’s central block on both sides with a monumental arch connected to a tower (see Fig. 5). These additions, Chapter 7 argues, belonged to the initial project sanctioned by the patron, not to the later period when Palladio prepared his treatise for publication.31 Like the accumulation of land, the construction of a villa house was expected to be a piecemeal process. The treatise illustration thus represented not an idealization but an expanded version of the built fabric intended to be realized in time. Such an interpretation offers a potential framework for resolving other thorny questions in Palladio studies about the discrepancies between his villas as built and their published schemes.

The triumphal-arch form of the proposed extensions would have constituted the boldest statement of Pisani’s ambitions as a landowner and a patron. Chapter 8 shows how the wings would have reinforced the villa’s hybrid character by relating Palladio’s design to a range of urban and rural building types and to the politically fraught reception of the ancient triumphal arch in Venice and the Veneto. Although the original scheme did not reach completion before Francesco Pisani’s death, the villa achieved its patron’s goal of representing the family’s lineage and wealth, just as the farm estate would enrich his previously impoverished heirs. This reversal of fortune, however, would prompt a reversal of the family’s orientation to the terraferma, as Chapter 9 shows.

My investigation, finally, sheds light on the Palladian legacy outside of the Veneto. More than any other architectural book, the Four Books achieved its author’s immortality. Recent Palladio-inspired dwellings can be found in places as diverse as South Bend, Indiana, and Nablus in the Palestinian West Bank.32 Palladio has continued to occupy a place in modern and contemporary architectural discourse,33 if not the central role he held in building culture of the eighteenth-century transatlantic British world.34 Although the alternative, two-story country house scheme offered by Villa Pisani was largely ignored by English authors and designers of that period, it proved an important model for planters and other patrons in the southern, slaveholding colonies of British North America. Two features of its flexible design – the pedimented, two-story portico and the hyphenated wings – would find renewed life at the edge of a different empire.

The pressing problems of the contemporary world, including large-scale ecological change and urbanization, make it an appropriate moment to consider how cultures of the past have conceptualized the relationship between the urban and the rural. I began this research as a graduate student in Princeton, NJ, a university town on the gritty corridor between two major US cities that, like many Renaissance villas, is both a locus amoenus (pleasant place) and a refuge of wealth and privilege. The book took shape while I lived in Chicago, the nation’s third largest city, whose legacy as the Urbs in Horto (City in a Garden) masks another urban history of deep inequity and segregation, especially in housing. And now my project comes to completion in Lexington, KY, an urban county of 300,000 ringed by horse farms, which faces urgent questions about sustainable growth and development. Each of these places, caught between city and country, has taught me something about how architecture mediates between human lives and the world around us. This book examines the ways the urban-rural nexus shaped and was shaped by how people lived, in this case through the architecture, landscape, and lived spaces of the villa.