Nanjing, Christmas Day, 1946. General George C. Marshall, US Special Envoy to China, was attending a concert organized by his hospitable Nationalist hosts in the capital when his Jeep with the special “USA20593633” plate went missing. As it turned out, the Jeep was stolen by a local thief who quickly turned it on the thriving black market. One Chinese critic called the Jeep incident an omen and allegory of the American failure in China.1 However, it was not just the failure of Marshall’s mediation in the Chinese civil war, or even the failure of US policy in China at large, but also America’s failure to sustain the image of a good and special ally just a little more than one year after winning World War II (WWII). One day earlier, and more than six hundred miles to the north, in the ancient capital of Beijing (Peiping), nineteen-year-old college student Shen Chong had been raped by an intoxicated US marine. Nationwide protests broke out over the next few days, calling for severe punishment of the American rapist and the complete withdrawal of the US military from China. But as we zoom in to the actual scene of the protest, GI spectators inside a locked compound were spotted joining outside protesters, who were shouting “Get out of China” (gun chu Zhongguo), by shouting back, “I want to go home!”2 The exchange of these messages, steeped in emotions, reveals a highly volatile and ultimately defining moment in Sino-US history that is often called the “loss of China.”3

Everyday Occupation provides a microhistory of the quotidian encounters between American soldiers and Chinese civilians and their entangled relations from the end of WWII to the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Drawing upon official, popular, and personal accounts from both countries, it focuses on the sensorial, material, and symbolic exchanges between GIs and ordinary Chinese people – pedestrians, rickshaw pullers, suspected thieves, stall vendors, and the “Jeep girls” (jipu nülang) who were seen as fraternizing with US soldiers. Through the microlens of the everyday, this book reveals how grassroots interactions affected larger political dynamics during a critical era in Sino-American relations. I argue that ostensibly mundane matters such as traffic accidents, sexual relations, theft, and black-market dealings provide a key to understanding the intensity and longevity of popular Chinese anti-American sentiment, as the abstract concepts of imperialism and sovereignty became legible in the common language of life and death, gain and loss, and fairness and injustice. Meanwhile, American servicemen and Chinese civilians engaged in a form of informal diplomacy, developing new tastes, languages, consumption habits, and identities, as well as individual and institutional bonds, all of which left a lasting imprint on both countries.

Shortly after the Jeep incident, General Marshall, newly appointed secretary of state, declared the end of his peace mission in China and returned to the United States in January 1947. As President Harry S. Truman’s special representative, Marshall had spent a trying year in China, working tirelessly to end civil strife and bring about political unification. The Truman administration aimed to limit Soviet influence in the country by forcing the ruling Nationalists and the rival Chinese Communist Party (CCP) into a coalition government under Chiang Kai-shek’s leadership. On January 10, 1946, Marshall succeeded in securing acceptance of a ceasefire agreement, and an executive headquarters was set up in Beijing to supervise the truce, led by three commissioners representing the United States, the Nationalist Government, and the CCP. However, the resulting resolutions quickly broke down as both sides violated the ceasefire and fought over the strategically important region of Manchuria. Full-scale civil war broke out in June. To pressure Chiang to become more compliant in the peace negotiations, the US imposed a ten-month arms embargo from August 1946, and a US financial loan was also put on ice. In November, Chiang Kai-shek unilaterally convened the National Assembly, but both the CCP and the Democratic League refused to participate. By the spring of 1947, the Nationalists were in a dire predicament. The tide on the battleground was shifting as the CCP went on counteroffensives. The huge gap between government expenditure and income continued to increase, and the solution of printing money led to record high inflation and devastating consequences for the urban economy. Facing increasing social unrest and widespread student protests, the government cracked down on “Communist infiltration” and banned leftist publications and organizations. The military, economic, and political crises deepened throughout 1948, and on all major fronts the Nationalist Party lost public trust and legitimacy. Despite the considerable advantages it held over the Communists at the end of WWII, the Nationalist Party was defeated in the civil war that concluded in 1949.4

In world history, the immediate postwar era is celebrated for the victory against fascism and the beginning of postwar occupation and reconstruction. It is also known for the emerging Cold War conflict between the two superpowers that were directly involved in China’s postwar struggle. On August 8, 1945, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and attacked Japanese forces in Manchuria, following its pledge at the Yalta Conference. The Soviet forces treated the Japanese with little mercy, plundered Manchurian “war booty” valued at well over USD 800 million, and secretly aided Chinese Communists by sending arms and supplies.5 Moreover, they tried to maintain a physical presence in China. On August 14, the day before Japan’s surrender, the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance was signed by the Soviet Union and the Nationalist Government. The pact included the agreement that for thirty years, Lüshun (Port Arthur) would be a naval base used jointly by China and the Soviet Union, and Dalian (Dairen) would be a free port granting the Soviets privileged access rights. As a result, the Soviet military occupied these two strategic ports, securing advantageous positioning in the Asia-Pacific region. The full withdrawal of its forces from Manchuria, supposed to be completed within weeks, was delayed several times and not finalized until early May 1946. Even then, the Soviets continued to maintain a presence in both ports until the mid 1950s.6

The US occupation of North China occurred in the intertwining of these two crucial contexts: the internal tension culminating in a civil war and the global expansion of the US empire in the emerging Cold War.7 Fearing that the Chinese Communists and Soviets would fill the void left by Japan’s surrender, America acted quickly. In September 1945, more than fifty thousand marines of the III Amphibian Corps (IIIAC) were sent from the Pacific to North China for a new mission code-named Operation BELEAGUER. Its key occupation duties included accepting Japanese surrenders, repatriating more than 3 million Japanese soldiers and civilians, transporting half a million Nationalist troops to North and Central China, and liberating and rehabilitating Allied internees and prisoners of war.8 The IIIAC elements, including the 1st Marine Division and the 6th Marine Division, together with naval forces from the 7th Fleet and the US Military Advisory Group, formed the bulk of the US troops in China after WWII. At the peak of the US military deployment, 113,000 American soldiers were stationed in China for various duties, expanding their presence from the wartime hinterland to areas formerly occupied by the Japanese.9 While certain marine units were assigned to remote outposts in North China and Manchuria, American military personnel were concentrated in China’s major political, economic, and cultural centers: Beijing, Nanjing, Qingdao, Shanghai, and Tianjin. There they lived in city centers rather than separate camp towns and came into close contact with all types of Chinese people going about their daily lives – a major difference from their wartime predecessors who had been housed in designated hostels provided by the Nationalist Government. The nature of the mission also changed: American servicemen, including both veterans and new recruits, were no longer engaged in combat operations against Japanese forces like those who came before them. Instead, they participated in a variety of new activities, from occupation duties to humanitarian assistance and peacemaking. This shift marked a new stage for US military personnel’s interactions with Chinese society, expanding their engagement with local populations in roles and capacities beyond traditional wartime functions. But ultimately, the mission’s ambiguous, vague, and sometimes conflicting objectives, such as assisting the Nationalist Government while maintaining neutrality in the midst of an escalating civil war, made it a mission impossible to execute or succeed.

Despite the initial warm welcome extended in postwar China by locals who had suffered for years under Japanese rule, anti-American sentiment quickly developed in response to seemingly trivial incidents involving traffic accidents, sexual relations, and American goods. Rampant misconduct among American soldiers, coupled with systemic inequalities that pervaded individual and institutional interactions, provided fertile ground for grassroots frictions. Nationwide demonstrations broke out in the wake of the Peking rape incident, leading to the hitherto largest anti-American movement in Chinese history.10 The CCP seized upon the growing animosity and launched a major propaganda campaign against the continued presence of US military forces in China, American aid to the Nationalists that prolonged the civil war, and US imperialism in the world. By linking American imperialists with the reactionary Nationalist regime that acted as its “running dog,” the campaign contributed to the Communist victory, especially in advancing its political cause among urban populations.

In hindsight, it is tempting to see this historic encounter between US servicemen and Chinese civilians as a doomed failure. The late 1940s marked a turning point in Chinese perceptions of America: deep appreciation and gratitude turned into grievances and animosity, and public sentiment shifted from pro-America (qin Mei) to anti-America (fan Mei).11 According to a Time magazine report, American imperialism had replaced both Japanese imperialism and British imperialism “in the average Chinese intellectual’s dictionary of opprobrium,” and street urchins in Shanghai’s alleys sang the little rhyme of “Mei kuo lao, Chen pu hao” (American fellows are really no good)!12 While previous research has demonstrated the significant impact of US imperialism and Communist propaganda on this transition, viewing these unprecedented grassroots exchanges only through the prism of political domination and manipulation risks overlooking individual agency and historical contingencies. We also miss the opportunity to investigate how these two large political forces worked in relation to the messy world of mundane struggles. For example, how did the US system of law and justice fail in China despite its ideals of liberalism and realpolitik in the early Cold War environment? How did the Communist anti-American campaign manage to attract such a broad spectrum of supporters, ranging from outspoken leftists and liberal intellectuals to students, businessmen, and the urban poor? Moreover, what kinds of roles did Chinese individuals and American servicemen play in the nexus of Sino-US relations and everyday frictions? Answering these questions is crucial for understanding the postwar US global empire, the rise of Chinese anti-American nationalism, and the making and unmaking of Sino-US relations during a watershed moment in history. It also provides valuable lessons for today, when the world is once again caught in polarized ideological confrontations and nationalist conflicts.

Uneven Reciprocity: Locating China in the US Empire

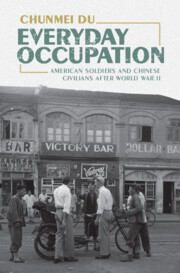

“The years from 1945 to 1949 will go down in Chinese history as the American period,” stated Graham Peck, a seasoned traveler who served with the US Office of War Information in China throughout the 1940s. This was evident as “former U.S. Army vehicles, uniforms, and arms became most conspicuous” across the country, with military advisors active in the capital, warships patrolling the seacoast, and military planes frequently flying over the interior.13 The United States after WWII, with its enormous soft and hard powers in both territorial and nonterritorial forms, includes a crucial military dimension – what many scholars call an “empire of bases.”14 The critical lens of empire provides a powerful framework for analyzing the US military in China, and it is essential to link its presence with that in other areas colonized, occupied, and stationed by America. In particular, power asymmetries embedded in Sino-US interactions at the national and individual levels were similar to those in occupied Japan and Korea, despite dramatic differences in political status and circumstances. Contemporary Chinese critics already compared GIs in China to the occupying forces in Japan, warning that the US was treating China as a colony. The US military’s policy perpetuated systemic racism and injustice against Chinese civilians in their policing and judicial process, and American servicemen expressed Orientalist views, held racist and sexist attitudes toward Chinese elites and commoners, and enjoyed immunity from local laws. In his recent book The Tormented Alliance, Zach Fredman convincingly shows the prevalence of GI misconduct and the unequal relationship imposed by US imperialism on China throughout the 1940s. However, framing grassroots interactions with the Chinese, including frictions, solely through the lens of “brutal, everyday racism of imperialism” does not adequately account for the complex nature of the US military involvement and modes of domination in postwar China.15

Unlike its East Asian neighbors under US occupation and the Philippines – a former colony and later client state – China was an ally and a sovereign nation. Officially, GIs were “invited guests” of the Nationalist Government, a status that was not in name only. For example, despite their critical contributions to the war effort and an initial plan to send them, black troops, in deference to the Chinese government’s racist requests, were not stationed in postwar Chinese cities.16 Since WWII, the American military had tried to educate its soldiers to respect the Chinese as civilized equals, while American propaganda celebrated China and its people with flattering portrayals.17 In the precarious environment of the civil war between the Nationalist and Communist Parties, the American government promoted a liberal image of itself as a “benevolent leader of the world,” in contrast to the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, it promulgated the economic agenda of a free world economy based on the open market and free trade, secured favorable terms for American businesses and investors, and enabled further domination through various instruments of influence. In principle, the US government intended to showcase democracy and provide a blueprint for a future liberal China. This projected sense of equality and fairness was crucial to the legitimacy of the expanding empire in the early Cold War era.18 Back home, the new American middlebrow intellectual representations highlighted mutually beneficial exchanges between Americans and Asians “within a system of reciprocity.”19 In China, US strategic objectives called for appeasement of rising anti-American sentiment among the Chinese, which the US actually attempted, and it was reluctant to directly intervene in the civil war. This peculiar power dynamic affected how US imperialism worked in China and shaped the inner workings of the Sino-American partnership.

The everyday interactions, especially conflicts, between American servicemen and Chinese civilians embodied the power struggles between the two governments. The Nationalist Government held an ambivalent and often conflicting attitude on the issue of US occupation. On the one hand, it hoped to prolong the US military’s stay during the civil war and remained dependent on US assistance, and on the other hand, it was resistant to foreign encroachment on Chinese sovereignty. As the Generalissimo declared victory against Japan and embarked on postwar reconstruction after eight years of devastating war, China claimed unprecedented national pride and a leading role in the region and even the world.20 The country embraced its new international status as one of the “Big Four” nations, along with Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union, and became one of the five permanent members of the newly established United Nations Security Council. Known for his sensitivity regarding national equality, Chiang flagged unequal treaties as a “national humiliation” that hampered Nationalist efforts to “build a nation” and acclaimed their removal as the start of a “new epoch” in history and “the most important page” in Chinese history.21 The Nationalist Government took sovereignty seriously and referred to US military activities in China as “presence” (zhuHua), rather than “occupation,” the term used by the US military for its mission in North China. The government was also careful in not setting legal precedents for other foreign countries. For example, although the US Navy saw Qingdao as a potential permanent naval base and used the port as a major fleet anchorage in the Far East until 1949, “no formal written agreement on stationing U.S. Naval vessels at China ports is known to exist,” as the Chinese government desired to “avoid written agreements of this nature.”22 Such a lack of formal agreements with clearly defined terms regarding the US military presence in China often led to unrealistic expectations, inconsistent assumptions, and disappointing outcomes on both sides.

By its nature, the presence of an invited foreign military in a sovereign nation is a significant military matter as well as a complex legal and political concern testing key issues of jurisdiction and sovereignty. The continuing system of extraterritoriality, dating back to the First Opium War, remained the most sensitive issue of the day.23 As an Ally, the United States relinquished its century-old rights of extraterritoriality on January 11, 1943, when the Sino-American Treaty for the Relinquishment of Extraterritorial Rights in China and the Regulation of Related Matters was signed. The historic treaty positioned China as an equal sovereign in the system of international law as opposed to the colonial system of unequal treaties.24 But it also necessitated the articulation of a fresh legal basis for the rights and privileges of American individuals and entities. Jurisdiction over American military personnel in China was the first issue to be settled according to these new terms. On the basis of reciprocity, a Sino-American agreement in 1943 recognized the US military’s exclusive jurisdiction over criminal offenses committed by its members in the country until six months after the war. The agreement was renewed in June 1946, extending the wartime legal privileges of US troops for another year, and was extended again in July 1947 until the complete withdrawal of US troops. Due to its sensitivity, the issue was raised well before 1943, but both sides waited to sign the agreement until after the monumental Relinquishment of Extraterritorial Rights treaty in order to prevent a potential negative influence on the latter.25

The GIs’ extraterritorial rights in China, both on and off duty, affected the dynamics of everyday interactions on the ground. They provided legal shields to servicemen whose misconduct toward Chinese civilians was often tolerated or prosecuted lightly. Today, the agreement is still widely criticized as a continuation of American extraterritoriality in China and an instance of the Nationalist Government’s trading of sovereignty for US support. But a close look at the negotiation process shows a more nuanced picture of the Nationalist Government’s role. Before the Agreement between the United States and China regarding Jurisdiction over Criminal Offenses Committed by American Armed Forces in China, Exchange of Notes (處理在華美軍人員刑事案件換文) was signed on May 21, 1943, the Chinese side had requested that a reciprocity clause be added. Whether it was done purely as “a matter of face,” the Exchange of Notes stipulated that “insofar as may be compatible with military security,” the US military trials would be conducted “in open court in China and within a reasonable distance from the place where the offense is alleged to have been committed” to facilitate witness attendance.26 Further, US authorities “will be prepared to cooperate with the authorities of China in setting up a satisfactory procedure for affording such mutual assistance as may be required in making investigations and collecting evidence,” and “it would probably be desirable that preliminary action should be taken by the Chinese authorities on behalf of the United States authorities” when witnesses were not members of the US forces.27 On October 1, the Regulations Governing the Handling of Criminal Offenses Committed by Members of the Armed Forces of the United States in China (處理在華美軍人員刑事案件條例) agreement was promulgated. Except for Article 1, which extended the jurisdiction of the US military over its members in China, all the other six articles placed restrictions upon such jurisdiction. For example, Article 4 provided that the US jurisdiction did not “under the Chinese law, affect the right of questioning, arresting, detaining, searching, attaching or investigating members of the United States armed forces who have committed criminal offenses or who are suspected of having committed criminal offenses.” Article 5 stated that Chinese authorities may request copies of American judgments “prior to the rendering of a judgment” and “make inquires as to the status of a case.”28

As we will explore later in this book, the Chinese government tried to set some limits on the “exclusive jurisdiction” of the US military and introduced terms that would restrict US privileges and enable Chinese participation or intervention in the process. But these provisions were difficult or impossible to implement without the collaboration of American military authorities in China. Even as late as June 1948, the Executive Yuan continued efforts to improve the judicial procedures for handling such criminal cases. It issued instructions to local governments, reaffirming the principles laid out in Articles 4 and 5.29 In practice, American authorities often simply disregarded and bypassed Chinese officials, distrusting local police or the government in general. Hampered by legal restrictions and, more importantly, the political necessity of depending on US military and economic aid while pursuing nationalist endeavors, Chiang Kai-shek’s government ignored, denied, or trivialized the GIs’ misconduct, insisting it was merely an isolated individual event, a strategy that eventually backfired. To many of its critics and supporters alike, the government failed in its mission to protect its citizens and defend the nation. It lost credibility and legitimacy when it failed to secure compensation, settle disputes, provide relief, and deliver justice to victims. Consequently, the Communists seized the opportunity to attack the Nationalist regime, accusing it of serving as America’s agent and signing new unequal treaties that made China its colony.

In recent decades, Chinese scholars have formulated various frameworks for understanding the new Sino-US treaties signed in the period leading up to and following WWII, ranging from viewing them as neocolonial treaties, completely and unapologetically unequal, to seeing them as equal in form but unequal in content. Revisionist histories have argued that these agreements, based on international law, should not be simply called a mere revival of extraterritoriality. Instead, they demonstrate progress in creating new bilateral treaties after the termination of extraterritoriality, thus signifying milestones in China’s journey toward integration into the new international legal order.30 In this case, American demands, usage, and abuse of legal privileges in China were intended to achieve American rights, privileges, and justice on their own terms. But they should not be equated with colonial treaties or simply dismissed as empty talk, fake trials, or sham pacts. These demands and treaties stipulating American rights and privileges in China show what I call a relation of “uneven reciprocity.” On the principle of equality and reciprocity, the two countries signed major agreements such as the provisions granting extraterritorial rights for US military personnel; the controversial 1946 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation; and various treaties on tariff relations, arbitration, educational exchange, and economic aid.31 Nevertheless, these agreements were unfavorable to China because it did not have the capacity to take advantage of the reciprocity rights or implement their terms, thus only ensuring American rights and privileges in reality. Such uneven reciprocity in Sino-US legal and political negotiation and practice mirrors the power asymmetry in the bilateral relations at large. It also showcases the new system of law and order that the US empire was developing after WWII, in which China, alongside other postcolonial and postwar states, struggled to negotiate equitable terms with the United States while striving to forge a “special” allied relationship through both collaboration and resistance.32 During a period of significant political and social fluidity in China and around the world, the Nationalist Government hoped to lay a foundation for postwar reconstruction and development. It sought to leverage the emerging global order while addressing American demands and balancing various – often conflicting – political agendas. Ultimately, it failed to overcome these challenges, particularly in dealing with the US military presence.

Overall, China in the late 1940s was subject to US political and economic domination. American servicemen, while conducting their “peaceful” missions, engaged with local populations in the context of national and systemic inequality. However, adopting a stark imperialist perspective reduces the intricate grassroots encounter to a dichotomous story of aggressors versus victims. This perspective also overlooks a crucial opportunity to deepen our understanding of the CCP, which launched the most successful anti-American campaign to date, targeting the very issue of American military presence.

Brutal Imperialists: Locating America in Communist Propaganda

In January 1947, Time magazine described the presence of “many thousands of ambassadors abroad – all of them in official uniform” as a historic first, which stoked animosities toward America globally, but especially among the Chinese.33 When widespread anti-American movements broke out in the late 1940s, it was baffling to the American elites and public. John Leighton Stuart, the US ambassador to China and a dedicated missionary educator, lamented that even with billions in financial aid, decades of philanthropy, no annexation of territory, “Why is there never anything but anger with America?”34 A Wall Street Journal piece called the protests “a peculiar form of ‘reverse lend-lease,’” a puzzling way of expressing “gratitude” for the crucial aid that the United States had provided in defeating the Japanese.35 To many Americans, Chinese animosities against the United States were a complete shock, as they vividly remembered the close wartime friendship embodied in such representatives as the “Flying Tigers” and Madame Chiang, not to mention the rousing Chinese cheers for marines on their recent landing that were featured in so many media and personal accounts.

Communist propaganda seemed the only plausible explanation for the about-face, and it became the answer supplied by the Nationalist authorities, the US military, and major American media outlets alike. The Nationalist Government did not acknowledge the legitimacy of anti-American sentiment or make serious attempts to address the key issues raised by the protestors. Not so unlike the Communists, who used these incidents as ammunition to fire at the enemy, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek condemned student protests as products of Communist instigation through underground operatives and spies, instructing his officials to repress these elements rather than address students’ demands. It might seem ironic that the two sworn enemies at war quickly settled on such an important assessment. But we know that both made persistent attempts to promote and manipulate nationalist sentiments for their own political gains, adopting such measures as planting agents on university campuses and waging propaganda wars.36 Anti-imperialism had remained a central theme in both parties’ legitimacy claims since their founding. A key difference, perhaps, was how effective their maneuvers were. While both groups claimed to be the true defender of Chinese sovereignty, the Communists succeeded in winning the propaganda battle, not only against America but also against their Nationalist rivals in the civil war.

According to the Communist Party’s own narrative, the anti-American movement of the late 1940s was an integral part of Mao Zedong’s broader strategy of “opening the Second Battlefield” in Nationalist-controlled areas. This strategy operated alongside the military front, featuring the struggles between “Chiang Kai-shek’s reactionary government” and the patriotic, democratic movements led by students, workers, and other urban populations.37 The Party’s official history weaves a cohesive account that positions nearly all major demonstrations under its central leadership, leading toward the Communist victory in 1949.38 In the summer of 1946, with the civil war intensifying, the CCP began to highlight American misconduct in China, educating the public about “brutalities” committed by GIs. In late September 1946, ten civil organizations in Shanghai launched “US Troops Quit China Week,” a campaign featuring a series of public meetings, press conferences, and news releases.39 Following CCP directives to expose American military misconduct, the campaign expanded to Chongqing, Beijing, Yan’an, and even Chinese communities abroad. It called on American progressive groups, the United Nations, and peace advocates worldwide to demand the immediate withdrawal of the American forces from China. Three months later, in the wake of the Peking rape incident, the Party launched an “Anti-Brutality” (kangbao 抗暴) movement that quickly expanded across the nation and lasted several months. The campaign positioned the US military presence in a direct lineage stretching back to the Eight-Nation Alliance in the Boxer Uprising at the turn of the twentieth century. With unwavering resolve, the Communists proclaimed the abolition of “all the treasonable treaties” made with imperialist countries, especially those brokered by the Nationalists, and demanded all US troops be withdrawn from China.40 In May 1948, during the final phase of the civil war, another major protest movement, “Opposing the US Support of Japan” (fanMeifuRi 反美扶日), broke out over the new US occupation policy in Japan, especially the plan to assist in its postwar reconstruction. Fueled by resentment against Japan and fears of renewed Japanese aggression, college students and intellectual elites across the country initiated a new wave of protests. They were quickly joined by workers and urban residents, who were drawn by the pressing issues of hunger, oppression, and American intervention in the civil war.41

In general, the CCP campaign condemned the continuous American military involvement and exterritorial rights, US aid to the Nationalist Government, and support of the civil war, framing these issues only as a matter of foreign imperialism. Despite the relatively short duration and limited scale of the US military presence, the CCP was able to make this a central focus and headline for the nation. Upon the Allied victory in WWII, American prestige and standing within China reached unprecedented levels, and there were great hopes for US aid in the country’s socioeconomic and political developments. In the early postwar years, Chinese experiences and discussions of America could be described as a mixture of fascination and uneasiness. Critiques of America came from both the left and the right: while leftists criticized capitalism and economic imperialism for endangering Chinese industries, right-wing ultranationalists warned against cultural and racial corruption through American influence, and both were concerned about national sovereignty and American intervention. Nationalist discourses concerning American influence encompassed a variety of conservative, leftist, and liberal groups and continuing debates over Westernization and modernization from earlier decades. Nevertheless, as Communist propaganda fired up and political and economic situations worsened in Chiang-controlled urban areas, these multivalent debates over American society, culture, and commodities became increasingly politicized and singular.

Certainly, the CCP played a key role in organizing and leading the anti-American campaign in the late 1940s, contributing to its overall success. But we should be cautious of the seemingly coherent and almost teleological narrative espoused in its official history. For instance, Party cadres in Beijing were initially surprised by the rapid development of student protests in reaction to the Peking rape incident, concerned that the issue was too local to attract support from other campuses.42 The number of underground Party members among students remained relatively small, and they had to navigate an oppressive environment with care. Despite many students chanting anti-American slogans, some directed appeals to Chiang Kai-shek, seeking justice for the victim. American diplomats and observers also acknowledged that these anti-American movements were not all Communist-instigated but had a broader base, with some arguing that attributing them solely to the Party would be “paying the Communists too great a compliment.”43 There were even instances when Nationalist agents might have helped stir up anti-American sentiment. The American consul general in Dalian compared the Communist and Nationalist attacks on American policy, describing the latter as “if less direct, in the long run … rather more than less insidious and destructive of popular liking for the United States.”44 In reality, not every campaign launched by the Communists in urban centers achieved success. For example, the 1947 boycott campaign against American products in Shanghai did not gain widespread support, as it jeopardized the livelihoods of certain groups of workers, vendors, businesses, and local residents.45 In essence, the Party’s calls to oppose US imperialism did not always work. Rather than orchestrating a series of cohesive and coherent movements, as is often claimed, the CCP actually seized the opportunities, capitalized on popular sentiment, and co-opted the protests into a political campaign that was taking shape.

Beyond the Communist ideological attacks, the intensity and longevity of popular anti-American sentiment should also be understood in the context of everyday struggles. Ultimately, grassroots frictions provided a decisive weapon for Communist anti-American propaganda, effectively fueling Chinese nationalism. The visceral perils of daily life affected Chinese people across the political and socioeconomic spectrum – whether college students, local officials’ wives, illiterate migrants to the city, or rickshaw pullers – as they fell victim to drunk US soldiers, speeding Jeeps, and the excessive use of force. Based on these events, the Communist media set a new script for Sino-US interactions, assigning the two parties the binary and collective roles of everyday victim and bully.46 This affective formula featured key ingredients of American racism, sexual aggression, and physical violence as a result of extraterritoriality and unequal treaties. As such, seemingly frivolous disputes over speed limits, fair bargains, physical and social boundaries, economic compensations, and moral and legal responsibilities embodied the otherwise abstract issues of national inequality and infringement of sovereignty. While the Communist propaganda of this era played the familiar notes of anti-imperialism from the early twentieth century, it was the new theme song of everyday brutality that struck an emotional and responsive chord among a wide base of urban residents, from outspoken leftist and liberal intellectuals to businessmen and even government officials. It is perhaps not surprising that the Communists, who positioned themselves as champions of the common people, emphasized the suffering of ordinary victims. Ironically, this focus, also borrowed from wartime tropes and imagery about Japanese atrocities – some of which Americans had propagated in their war against Japan as well – was now conveniently adapted to target American soldiers.47 The stereotype of the US soldier-imperialist committing “atrocious acts” toward Chinese civilians spoke a clear, strong, and intelligible message to all.

Entangled Relations

The everyday: what is most difficult to discover.

Anchored in micropolitics, Everyday Occupation examines how the quotidian encounter between US serviceman and Chinese civilians was experienced, embodied, and narrated by both sides.49 It foregrounds the experiences and agencies of ordinary individuals in Sino-US relations through the everyday actions they took to survive, cope, appropriate, resist, and prosper. While diplomatic negotiations settled issues of economic aid, political policies, and occupation terms between the two nations, the grassroots protagonists of this historical account engaged in day-to-day struggles to cope with the dangers of war, social disintegration, political chaos, and psychological stress amid some of the most devastating conflicts in modern Chinese history.

Turning toward the everyday, as this study does, is both historically necessary and theoretically critical.50 “The personal is political,” declared pioneering feminist scholar Cynthia Enloe, emphasizing the role of the private, domestic, and mundane in shaping international politics.51 Micro-actions by local agents have a cumulative power to shape larger dynamics.52 In postwar China, mundane matters were not only crucial in shaping the new Communist anti-American trope and collective memories, but also fundamental to how the Chinese experienced, perceived, and challenged America and Americans. On the national and international stage, massive protests against GI misconduct garnered a wide range of supporters, and the tale of Sino-US reciprocity and equality continued to be questioned. In their day-to-day interactions, local civilians negotiated prices and payments with American servicemen, capitalized on complex economic and cultural exchanges, and undermined the US pedagogy of fairness and justice using their own tactics. Methodically, an alliance between the history of everyday life and international relations also provides an antidote to the two aforementioned teleological traps in the study of Sino-US interactions, American imperialism on the one hand and Communist propaganda on the other. As Harry Harootunian has argued, history writing driven by the nation-state often conceals, disguises, and suppresses the everyday.53 The messy mundane world, its contingency, fragmentation, and cacophony, does not easily fit into a linear narrative of the past leading to national destiny. To the majority of Chinese civilians, against the backdrop of the US occupation, daily preoccupations remained primary, especially in a time of war and disorder, and the motivation to survive and prosper overshadowed national issues in their interactions with American soldiers. In the official history and existing literature, however, the dynamic roles assumed by these parties are often reduced to a simple dichotomy between victims and perpetrators, depriving those involved of voice, identity, and even name. Dominant nationalist historiographies leave little space for the struggles, actions, and agencies of local protagonists that are deemed trivial or irrelevant.54 Many of their stories are ignored or silenced, and those that are told are often filtered through patriarchal nationalist agendas.

The matter of occupation is both extraordinary and mundane. The theater of operation encompasses not only key defense sites and railway lines but also the loci of households, streets, bars, markets, and recreational spaces. This study prioritizes the everyday space as a microcosm of larger systemic relations between nations, races, genders, and classes, as well as a dynamic contact zone where spontaneous and calculated micro-actions take place. I foreground the materiality of the daily life, emphasizing its multiple situated contexts, and dwell on individual actors’ experiences and stories. The mundane acts of eating, dancing, going to a theater, playing sports, shopping, and using the toilet rarely appear in the grand national histories and might be difficult to locate in government archives that were compiled and preserved with concerns over national destiny in mind. But once we shift the focus and zoom in to the human moments and quotidian actions within micro-arenas, the ubiquitous presence of ordinary individuals and the roles they play begin to emerge.

The everyday is both a geographical and a social space consisting of concrete places and symbolic microcosms.55 In this story of the Sino-US encounter, the actions take place in the Nanjing parking lot where General Marshall’s Jeep was stolen, outside a Tianjin warehouse where suspected thieves were shot dead by GI sentries for stealing several boxes of stationery supplies, within a Beijing dance hall where American and Chinese soldiers fought over dance girls, and on the wall of a marine billet where watching US soldiers joined in with Chinese protesters’ slogan shouting. The everyday space also includes the representational and imaginary space of newspaper advertisements, tabloid reports, and magazine columns, where Chinese women wrote letters asking what to do with their GI boyfriends, adoption agencies advertised mixed-race babies, satirical poetry mocked American men as “toad-like” or “over-innocent country-bumpkins,” and Communist and leftist editorials condemned atrocious American acts against the Chinese people.56 The everyday space expands further to take in the legal and political space of the American courtroom, where Chinese witnesses were invited to participate and yet not heard, and the Nationalist Government meeting rooms, where victims’ families and representatives from professional associations gathered to appeal for compensation, intervention, and justice.

In this book, US servicemen and Chinese civilians are cast as the main characters and treated not as political pawns but rather as local actors with transformative potential. American soldiers were problematic agents of the empire. They were, first and foremost, foreign armed forces – occupiers, guards, humanitarian aid workers, advisors, and peacekeepers – performing assigned military duties. They were also tourists, consumers, fashion setters, sexual partners, and cultural messengers on the ground, there to cultivate alliance and represent and spread US democracy and values. In their daily lives, while American soldiers savored the taste of victory and Oriental city life, they were also confronted by the harsh realities of China’s economic devastation, social unrest, and renewed civil war. The GIs were preconditioned by Orientalist views and racist behaviors, but they also stepped out of their comfort zone and engaged with novel experiences and forged new relations with the locals. Upon their return, veterans brought pieces of China home via souvenirs, photos, spouses, and children, as well as tastes, vocabularies, tales, aesthetics, and identities, which were all woven to a varying degree into America’s sociocultural fabric in the mid twentieth century. Servicemen joined missionaries, journalists, scientists, teachers, students, donors, and Chinese-Americans throughout the 1940s in creating new transpacific networks, institutions, relationships, and dynamics in Sino-US exchanges that helped lay the groundwork for a postwar world order.57

On the Chinese side, most people, including protestors, harbored a mixture of resentment, misgivings, and fascination with respect to GIs and America at large. Dance hostesses, prostitutes, rickshaw pullers, houseboys, cooks, restaurant owners, tour guides, street vendors, black marketeers, thieves, and gangsters endured and resisted, as well as seized opportunities to capitalize on the presence of US servicemen. While some locals loathed them as violent bullies and evil imperialists, others welcomed, desired, and depended on them for the material, cultural, and political capital they brought as liberators, customers, patrons, and purveyors of Western goods and culture. As this book will show, the US military presence left overt and covert imprints on China’s physical and mental geography. The GIs instituted the practice of right-side driving, affected local economies – including restaurants, brothels, and rickshaws – and participated in a booming black market for American goods. Servicemen also introduced new technological and commercial products and cultural spectacles, such as Jeep rides and Western courtship rituals. As locals emulated GIs in drinking Coca-Cola, sipping surplus coffee, using DDT to spray their houses and soil pits, and receiving penicillin shots, the United States entered the intimate and public spaces of Chinese life – bodies, households, streets, soil, and water, as well as memories, legends, and propaganda. Through these iconic and everyday products, together with US soldiers who visibly consumed, represented, and advertised them, Chinese society at large came to see, feel, and interpret America. Although American commodities and culture had been present since the old China trade, it was in the late 1940s that ordinary people on the coast and in the hinterland gained access to a more substantial American experience. This direct encounter affected their daily lives and views of a country that had previously been too remote to reach or even imagine. Through this newfound connection, the once abstract ideals of America became a tangible reality.

Both Chinese citizens and GIs crossed many boundaries in their encounters at the crossroads of micro and global spaces. Like the “anonymous hero” who, in the words of Michel de Certeau, uses context-specific “tactics” in everyday practices, they had to navigate unfamiliar worlds, speak each other’s languages, develop new tactics to deal with foreign situations, protect their individual interests and the “face” of their nation, and even adopt new names and identities.58 Such encounters were shaped by local and global knowledge and beliefs, sociocultural biases on both sides, and the larger political dynamics between the two nations. But these interactions were not simply a replay of the official guides that instructed them on how to act toward each other. Nor were they an enactment of formal treaties or agreements signed by national leaders. They were also spontaneous, messy, and inconsistent and often went beyond the official ideology and even common wisdom. It is in the micropolitics of the everyday where the macro-order of the US global empire was negotiated, contested, and potentially transformed.

To argue for a causal relation between the “micro” of everyday politics and the “macro” of international relations involves a huge interpretative leap. For instance, one may ask: Did the American military staying on end up doing more harm than good for the Nationalists? Could greater efforts by the US government to address soldiers’ misconduct or a willingness to relinquish extraterritorial rights for its servicemen have prevented anti-American sentiment? These counterfactual questions, like the “lost chance” hypothesis, have no definitive answers. Yet it is reasonable to speculate that a clearer and more cohesive mission, and one attuned to local realities and grassroots tensions, could have lessened the tragic loss of life on both sides. It could also have reshaped Chinese perceptions of America and perhaps influenced how the civil war unfolded – even if not deciding its ultimate outcome.

It remains a methodological and narrative challenge to strike a balance between elements of human agency and larger, more impersonal forces that impinge upon it, to stitch together all the causative factors and weave the enmeshed fabric of micro-relations into a coherent pattern. But it is precisely such elusive specificities that lie at the core of historical and humanistic inquiries. The contradictions, ambiguities, and subtleties at the micro-level of this global encounter are not mundane distractions from the larger story but rather keys to unlocking a more authentic one. Overall, this book uncovers a forgotten history of entangled relations between GIs and Chinese civilians that was profound for both nations. It hopes to shed light on this complicated history of US-China interactions that mixed military occupation, economic expansion, imperialist aggression, nationalist assertions, Communist maneuvers, and day-to-day struggles, mundane resistance, everyday desires, and hopes for new beginnings. While the “loss of China,” often attributed to state policies and ideological struggles, speaks of a failure that is evidenced by the withdrawal of the last GI from China in 1949, Everyday Occupation, focusing on the micro-level, sheds light on dynamic and mutually transformative quotidian encounters. Full of perils and opportunities, this process of entanglement tells a story different from the inevitable fall.

Chapter 1 examines the US military operations in China within the volatile context of the civil war and emerging Cold War. As the US forces accepted the Japanese surrender, clashed with Communist forces in sporadic skirmishes, and adjudicated trials of Japanese criminals in China independent of the Nationalist Government, they staged American victory, might, and justice for both enemies and allies. The tactic of “show of force” was used in a “peaceful” mission to ensure submission and deference. However, its diverse, ambiguous, and at times contradictory objectives created significant military and political challenges. Ultimately, occupying China became a mission impossible.

Chapter 2 explores American servicemen’s everyday lives through their sensory encounters with China. While largely maintaining a privileged lifestyle separate from Chinese society, they also forged intimate connections with local populations by exchanging goods, service, language, and culture, an encounter that both followed and contradicted official policies and popular representations. As tourists, consumers, cultural messengers, and diplomats in the field, their encounters with China were characterized by both fascination and contempt, enchantment and alienation. While their sensorial experiences and narratives were conditioned by preexisting Orientalist beliefs and racist prejudices, GIs’ cultural identities were reshaped by daily interactions involving new sights, smells, tastes, sounds, and touches.

While Chapters 1 and 2 focus on American servicemen’s experiences and narratives, Chapters 3, 4, and 5 examine the three largest sources of Chinese grievance or fascination – traffic accidents, intimate interactions, and American products. Chapter 3 investigates the frequent accidents caused by American military vehicles, the most common trigger of everyday tensions, as well as GIs’ turbulent relationships with rickshaw pullers. Following frequent accidents caused by drunk driving, speeding, and negligence, the American Jeep turned from an object of enchantment, a symbol of Allied prestige and a cultural spectacle and popular commodity, into a military tool of intimidation, danger, and harassment, threatening the existing order of Chinese society and the nation. As the two sides fought over speed limits, economic compensation, moral responsibilities, and legal justice, the Jeep-GI duality, embroiled in local street politics with rickshaw pullers, became the ultimate symbol of prolonged American occupation trampling Chinese sovereignty. Chapter 4 examines American soldiers’ actual and perceived sexual relations with Chinese women, the most sensitive subject that triggered the strongest anti-American sentiment. While Chinese conservatives, out of racial and sexual anxieties, maligned women who consorted with GIs, liberals and self-identified “Jeep girls” ingeniously invoked the language of modernity and patriotism. However, in the wake of the Peking rape incident, the once lively debate over modernity was quickly silenced as nationwide protests raged against American imperialism. Chapter 5 analyzes the everyday impact of American goods on Chinese lives and views of America. Massive quantities of industrial products, such as instant coffee, Coca-Cola, canned food, penicillin, and DDT, poured into postwar China through American aid and war surplus sales, creating new and the only direct experiences many had of America. This growing consumption engendered Chinese fears of capitalism crushing domestic industries and US materialism corrupting Chinese morality. Meanwhile, the American military’s stringent “halt or shoot” policy, implemented to protect US properties from theft and black marketing, led to frequent killings of members of the civilian population. The policy gave rise to the deadliest type of grassroots encounters, resulting in legal disputes and political crises.

The shadow of the American occupation remains long and haunting. The recurring persona of the Chinese victim facing American brutality, further popularized through propaganda during the Korean War, continues to influence Chinese anti-American nationalism. After all, the postwar US mission in China unfolded within the vital space of the everyday, where the occupying GIs encountered Chinese civilians in their preoccupations with daily life. It is in this forgotten story of the quotidian encounter, in the entangled relations, that we find connections – disjointed and faulty at times – that paved the historical paths of China and the United States.