Introduction

Social determinants of health, which include legal status, have been shown to effect both levels of healthcare access and health outcomes for individuals without legal status and their families in the United States (Adler and Rehkopf, Reference Adler and Rehkopf2008; Castañeda et al., Reference Castañeda, Holmes, Madrigal, Young, Beyeler and Quesada2015; Footracer, Reference Footracer2009; Hacker et al., Reference Hacker, Anies, Folb and Zallman2015; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Velazquez, O’Connor, Simon and De Groot2011; Martinez et al., Reference Martinez, Wu, Sandfort, Dodge, Carballo-Dieguez, Pinto, Rhodes, Moya and Chavez-Baray2015; Vargas Bustamante et al., Reference Vargas Bustamante, Fang, Garza, Carter-Pokras, Wallace, Rizzo and Ortega2012; Vargas and Ybarra, Reference Vargas and Ybarra2017; Zamora et al., Reference Zamora, Kaul, Kirchhoff, Gwilliam, Jimenez, Morreall, Montenegro, Kinney and Fluchel2016). As a result, it is not surprising that their healthcare access and outcomes are generally compromised (Adler and Rehkopf, Reference Adler and Rehkopf2008; Castañeda et al., Reference Castañeda, Holmes, Madrigal, Young, Beyeler and Quesada2015; Footracer, Reference Footracer2009; Hacker et al., Reference Hacker, Anies, Folb and Zallman2015; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Velazquez, O’Connor, Simon and De Groot2011; Martinez et al., Reference Martinez, Wu, Sandfort, Dodge, Carballo-Dieguez, Pinto, Rhodes, Moya and Chavez-Baray2015; Vargas Bustamante et al., Reference Vargas Bustamante, Fang, Garza, Carter-Pokras, Wallace, Rizzo and Ortega2012; Vargas and Ybarra, Reference Vargas and Ybarra2017; Zamora et al., Reference Zamora, Kaul, Kirchhoff, Gwilliam, Jimenez, Morreall, Montenegro, Kinney and Fluchel2016). Importantly, compromised access to healthcare not only affects individuals without legal status but may also have broader effects on communities and society at large (Kostandini et al., Reference Kostandini, Mykerezi and Escalante2014; Matthew et al., Reference Matthew, Monaghan and Luque2021; New York Times Editorial Board, 2020; Public Policy Institute of California, 2020).

In acknowledgement of the important and unique role that health and healthcare play in the lives of individuals, and aware of the barriers that those without legal status face in accessing care, immigration enforcement has long limited enforcement actions in and around healthcare settings as well as other sensitive areas like schools and churches (Mayorkas, Reference Mayorkas2021; Morton, Reference Morton2011). However, the Trump Administration has substantial altered policy in this regard and moved towards an increasingly intrusive approach that offers few if any sanctuaries (Boyd-Barrett, Reference Boyd-Barrett2025; Siegel et al., Reference Siegel, Natanson and Meckler2025; Trump, Reference Trump2025). States have responded to these policy changes in a manner consistent with partisanship (Boyd-Barrett, Reference Boyd-Barrett2025; Fortiér, Reference Fortiér2025; Sánchez and Chang, Reference Sánchez and Chang2025). Indeed, Florida and Texas have aggressively moved on this issue (Chang, Reference Chang2023; Figueiredo, Reference Figueiredo2024) while states like California have proceeded in the opposite direction (Boyd-Barrett, Reference Boyd-Barrett2025). These policy actions lend further credence to the assessment that political determinants of health may play an ever increasing role given the augmented levels of polarisation and partisanship in the United States today (Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021a, Reference Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021b; Van Bavel et al., Reference Van Bavel, Gadarian, Knowles and Ruggeri2024; Zingher, Reference Zingher2022). This particularly applies to an issue as controversial and salient as immigration (Anderson and Turgeon, Reference Anderson, Turgeon, Anderson and Turgeon2022; Blackburn and Haeder, Reference Blackburn and Haeder2024; Haeder and Moynihan, Reference Haeder and Moynihan2025; Kraut, Reference Kraut1995).

Overall, these policy changes at both the federal and state levels then indicate a dramatic detour from the status quo. However, while diminishing the restrictions on immigration enforcement officials as they pertain to sensitive areas has important implications, some of the policies specifically targeting healthcare providers by, eg., requiring them to document patients’ legal status or documenting the number of individuals without legal status who seek care, add an additional dimension. As such, they also pose important and broader questions because of the unique role assigned to healthcare providers by society and because they may directly or indirectly affect care experience and quality, access, and health outcomes as well as raise broader ethical and normative issues for healthcare providers (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Molina and Saadi2019; Lamneck et al., Reference Lamneck, Alvarez, Zaragoza, Rahimian, Trejo and Lebensohn2023; Sconyers and Tate, Reference Sconyers and Tate2016).

Given the important role of public opinion in shaping public policy (Burstein, Reference Burstein2003; Kingdon, Reference Kingdon2010; Page and Shapiro, Reference Page and Shapiro1983) as well as the importance of congruence between government actions and public support for the legitimacy and trust in democratic governance (Birkland, Reference Birkland2020; Peters, Reference Peters2004), understanding if the American public supports such policies from documenting legal status in medical charts to actively assisting immigration enforcement is an important inquiry at a time of rapidly changing immigration policy in the United States. Importantly, are public attitudes stable or can they be affected by highlighting the implications of these policies for immigrants, communities, and the broader public? This study aims to answer these questions by assessing public attitudes about requirements for healthcare providers related to individuals who lack legal status in the United States using a large national survey (N = 6049) that queried respondents about five specific policies related to healthcare providers and immigrants. Specifically, we relied on a survey experiment to assess public attitudes based on exposure to various informational treatments including the policies impact on individuals without legal status, US citizen children of individuals without legal status, and the broader community, either through disease exposure or effects on the food supply. In the next section we have provided an overview about our expectations based on the existing literature on the topic. We then present our data and methodology before presenting results. Lastly, we discuss our findings and assess their broader implications.

Background and expectations

Immigrants and healthcare

Social determinants of health, which include legal status, have been shown to effect both levels of healthcare access and health outcomes for individuals without legal status and their families in the United States (Adler and Rehkopf, Reference Adler and Rehkopf2008; Castañeda et al., Reference Castañeda, Holmes, Madrigal, Young, Beyeler and Quesada2015; Footracer, Reference Footracer2009; Hacker et al., Reference Hacker, Anies, Folb and Zallman2015; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Velazquez, O’Connor, Simon and De Groot2011; Martinez et al., Reference Martinez, Wu, Sandfort, Dodge, Carballo-Dieguez, Pinto, Rhodes, Moya and Chavez-Baray2015; Vargas Bustamante et al., Reference Vargas Bustamante, Fang, Garza, Carter-Pokras, Wallace, Rizzo and Ortega2012; Vargas and Ybarra, Reference Vargas and Ybarra2017; Zamora et al., Reference Zamora, Kaul, Kirchhoff, Gwilliam, Jimenez, Morreall, Montenegro, Kinney and Fluchel2016). Partly in acknowledgement of the role that legal status serves as a barrier to healthcare access and positive health outcomes, the Director of US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) issued the “Enforcement Actions at or Focused on Sensitive Locations” memorandum in 2011 (Morton, Reference Morton2011). This policy discouraged immigration enforcement actions in and around specific locations such as healthcare facilities and schools (Morton, Reference Morton2011). In 2021, the policy was updated and expanded (Mayorkas, Reference Mayorkas2021), again acknowledging the role that legal status can play in deterring actions such as accessing healthcare and demonstrating a commitment to keep hospitals and clinics free from the politics of immigration. The goal was to allow undocumented immigrants the ability to seek healthcare without fear of arrest and deportation (Mayorkas, Reference Mayorkas2021; Morton, Reference Morton2011).

The policy environment surrounding immigration has shifted significantly in recent years, particularly since the inauguration of the second Trump Administration. Following up on significant anti-immigrant rhetoric during the presidential campaign (Woolhandler et al., Reference Woolhandler, Himmelstein, Ahmed, Bailey, Bassett, Bird, Bor, Bor, Carrasquillo and Chowkwanyun2021), the Trump Administration has implemented a slew of policies that negatively affect immigrants, particularly those without legal status (Siegel et al., Reference Siegel, Natanson and Meckler2025; Trump, Reference Trump2025). These policy changes also included ending the sensitive locations policy via executive order. This follows instances from the first Trump Administration where immigrants were arrested when seeking care including during emergency care, ambulance transfers, and labour despite the policy still technically being in place (Sánchez and Chang, Reference Sánchez and Chang2025).

States have responded to the changing political environment based on predictable partisan dispositions (Fortiér, Reference Fortiér2025; Sánchez and Chang, Reference Sánchez and Chang2025). On the one hand, many Republican states have actively embraced the types of policy changes initiated by the Trump Administration. Indeed, two states (Texas and Florida) had already gone a step further and passed state-level policies which instruct healthcare institutions to gather information on the legal status of their patients (Sánchez and Chang, Reference Sánchez and Chang2025). The Florida legislation, SB1718, which was signed into law in 2023, requires hospitals that accept Medicaid to ask patients if they are lawfully present in the United States (Arranda and Molina, Reference Arranda and Molina2024). The Texas law, which was enacted in 2024, requires all hospitals in Texas to ask this same question, aggregate the data, and report it to the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) beginning in January 2026 (Figueiredo, Reference Figueiredo2024).

While previous work has argued that the federal sensitive locations policy minimises the risk of documenting legal status in healthcare settings (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Molina and Saadi2019), the removal of this protection raises new questions about such documentation. And while the stated purpose of both bills is to determine the financial costs that hospitals incur from providing healthcare to individuals without legal status, previous research suggests that it is likely to deter immigrants – with and without legal status – from seeking needed medical care (Berlinger and Gusmano, Reference Berlinger and Gusmano2013; Blackburn and Sierra, Reference Blackburn and Sierra2021). However, not all states equally support these types of policy changes. As a result, the policies implemented in Florida and Texas differ substantially from states like California and Massachusetts which are advising healthcare providers to avoid documenting immigration status and encouraging healthcare providers to advertise that no information on legal status will be collected for patients (Fortiér, Reference Fortiér2025; Sánchez and Chang, Reference Sánchez and Chang2025). In these states, healthcare providers have also been advised that they are not required to assist immigration enforcement but that they also should not interfere with any investigations (Fortiér, Reference Fortiér2025).

The federal level policy change that removed protections from immigration enforcement in healthcare settings, combined with state-level policy that requires healthcare providers to actively collect information on legal status, represent a substantial departure from policy precedent (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Molina and Saadi2019; Lamneck et al., Reference Lamneck, Alvarez, Zaragoza, Rahimian, Trejo and Lebensohn2023; Sconyers and Tate, Reference Sconyers and Tate2016). Particularly, the state-level laws on immigration status reporting by healthcare facilities raise several questions about healthcare access, respect for persons, and justice that have implications far beyond the two states who have implemented this legislation (Lively, Reference Lively2024). And while healthcare providers across the United States are emphasising that individuals will not be turned away from care (Figueiredo, Reference Figueiredo2024; Sánchez and Chang, Reference Sánchez and Chang2025), there are reasons to believe that these policies will have a chilling effect on healthcare access for those without status and their families (Abraham, Reference Abraham2018). This particularly holds as there is also evidence that these policy changes have created a climate of fear and distrust among immigrant families (Arranda and Molina, Reference Arranda and Molina2024; Pillai et al., Reference Pillai, Artiga and Rae2025).

Research also indicates that increasingly restrictive laws and enforcement can have broad implications for non-citizens, their families, and their communities (Cruz Nichols et al., Reference Cruz Nichols, LeBrón and Pedraza2018; Nichols et al., Reference Nichols, LeBrón and Pedraza2018; Pillai et al., Reference Pillai, Artiga and Rae2025; Torche and Sirois, Reference Torche and Sirois2019), particular for healthcare (Abraham, Reference Abraham2018; Martinez et al., Reference Martinez, Wu, Sandfort, Dodge, Carballo-Dieguez, Pinto, Rhodes, Moya and Chavez-Baray2015; Philbin et al., Reference Philbin, Flake, Hatzenbuehler and Hirsch2018; Rhodes et al., Reference Rhodes, Mann, Simán, Song, Alonzo, Downs, Lawlor, Martinez, Sun and O’Brien2015; White et al., Reference White, Yeager, Menachemi and Scarinci2014). Importantly, there is evidence to suggest that punitive policies can have significantly negative effects on undocumented immigrants and their families even when not implemented or enforced (Torche and Sirois, Reference Torche and Sirois2019).

These policy changes also present a slew of problems for healthcare providers (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Molina and Saadi2019; Lamneck et al., Reference Lamneck, Alvarez, Zaragoza, Rahimian, Trejo and Lebensohn2023; Sconyers and Tate, Reference Sconyers and Tate2016). To be sure, there are some benefits associated with documenting legal status because it can guide treatment and allow for a broader recognition of social determinants of health (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Molina and Saadi2019). However, most outcomes of requiring documentation would likely be detrimental to the health and well-being of individuals. For one, documenting legal status may affect the care experience of individuals because patients may be offered lower quality of care from clinicians with anti-immigrant beliefs (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Molina and Saadi2019) and because of potential stigmatisation (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Molina and Saadi2019). At its worst, documenting this type of information may render individuals subject to detainment, as there is some evidence that medical staff may have notified immigration officials when encountering individuals without legal status (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Molina and Saadi2019). Moreover, immigration enforcement may ignore and violate confidentiality laws (Lamneck et al., Reference Lamneck, Alvarez, Zaragoza, Rahimian, Trejo and Lebensohn2023). Documentation also opens the door for future efforts by immigration enforcement initiatives to utilise the information to detain immigrants as has been observed in other countries (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Molina and Saadi2019). Importantly, there are also broader historic concerns about physicians and other healthcare providers acting as “agents of the state” (Spevick, Reference Spevick2002). Lastly, these changes raise questions about whether future iteration of these policies go beyond merely documenting immigration status or tracking the number of undocumented individuals served for healthcare providers. That is, could healthcare providers be required to report individuals without status to immigration enforcement or even actively assist immigration authorities?

Treatment effects

There is evidence in the literature that the framing of political information has significant effects on attitudes (Kahneman and Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979; Norris, Reference Norris2021; Tversky and Kahneman, Reference Tversky and Kahneman1981). With regards to immigrants and immigration policy, framing becomes more important because most Americans hold positive views of immigrants even though most Americans also state that they support politicians who produce negative messages about immigrants (Asbury-Kimmel, Reference Asbury-Kimmel2023; Gallup, 2025). Importantly, there is evidence that Americans are not fully aware of the experiences of individuals without legals status and their role and contributions to US society and economy (Artiga, Reference Artiga2024; Bryant, Reference Bryant2024; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Guzman and Sifre2024). For example, Americans tend to overestimate the number of undocumented immigrants while underestimating their economic contributions (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Guzman and Sifre2024). Moreover, perceptions that individuals without legal status burden public services are widespread (Artiga, Reference Artiga2024; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Guzman and Sifre2024). Economic, cultural, and political frames have all been shown to have an effect on Americans’ attitudes towards immigration policy (Ayasli, Reference Ayasli2024; Kuntz et al., Reference Kuntz, Davidov and Semyonov2017; Mayda, Reference Mayda2006; Pardos-Prado and Xena, Reference Pardos-Prado and Xena2019). However, economic factors often overshadow other factors when Americans’ form attitudes about immigrants (Aalberg et al., Reference Aalberg, Iyengar and Messing2012). Additionally, previous research suggests that Americans are generally less supportive of government action aimed at protecting the rights of individuals without legal status in the United States (Voss et al., Reference Voss, Silva and Bloemraad2020), but even so, they show decreasing levels of support for immigration policy that prevents those without legal status from accessing necessary healthcare (Blackburn and Haeder, Reference Blackburn and Haeder2024). Given these facts, providing individuals with object facts and data about undocumented immigrants may decrease support for policies detrimental to them and their families. Hence, we hypothesise the following:

H1: Providing respondents with informational treatments about the effects of the policies on immigrants and communities will decrease support for all policies.

We note that this effect may be particular strong in cases that rely on negative framing (as we do in our treatments), which has been shown to be more powerful and salient than positive framing (Avdagic and Savage, Reference Avdagic and Savage2021; Baumeister et al., Reference Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer and Vohs2001; Rozin and Royzman, Reference Rozin and Royzman2001; Soroka, Reference Soroka2014).

At the same time, it seems likely that respondents will be more concerned about potential policy effects that may affect themselves (ie. their community) as compared to those solely focused on the policy effects of the individuals without status. Indeed, there is a large literature highlighting the importance of personal policy benefits (Bechtel and Liesch, Reference Bechtel and Liesch2020; Hansford and Gomez, Reference Hansford and Gomez2015; Kiewiet and Lewis-Beck, Reference Kiewiet and Lewis-Beck2011; Kinder and Kiewiet, Reference Kinder and Kiewiet1981). Put differently, respondents will likely be less supportive of policies that are closer to them (ie. more likely to affect them) as compared to those that are more distant (Arnold, Reference Arnold1992; Chong et al., Reference Chong, Citrin and Conley2001; Holbrook et al., Reference Holbrook, Sterrett, Johnson and Krysan2016). Hence:

H2: Treatments focused on highlighting the effects of the policies on immigrants will elicit the strongest support while those focused on effects on the community will elicit the weakest support.

Administrative tasks versus active immigration enforcement

While we expect some general effects across all policies, there may be important differences based on the nature of the policy and what is expected of the healthcare provider. Specifically, we expect that not all policies will elicit similar responses from respondents because they differ in the type of action required by healthcare providers as well as how closely involved these healthcare providers get with actual immigration enforcement. As noted above, all five policies affect healthcare providers because, to one degree or another, they move them outside of their care-providing role and associates them with immigration policy and enforcement (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Molina and Saadi2019; Lamneck et al., Reference Lamneck, Alvarez, Zaragoza, Rahimian, Trejo and Lebensohn2023; Sconyers and Tate, Reference Sconyers and Tate2016). The varying degrees of moving healthcare providers into roles that may make them “agents of the state” (Spevick, Reference Spevick2002) seem likely to affect public attitudes.

Specifically, we believe that respondents may make substantial distinction between tasks that most would consider mostly administrative in nature as compared to those with require them to become more active agents in the identification and detention of undocumented immigrations (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Molina and Saadi2019; Lamneck et al., Reference Lamneck, Alvarez, Zaragoza, Rahimian, Trejo and Lebensohn2023; Sconyers and Tate, Reference Sconyers and Tate2016). Administrative tasks like tracking and documenting are often considered to mere routine acts of record-keeping (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Molina and Saadi2019). These administrative acts allow for a substantial amount of distance between the administrative act and the potential active involvement in immigration enforcement. Moreover, administrative tasks are much more in line with behaviour and occupational expectations for healthcare workers as well as their social identity as providers of care. Lastly, administrative acts also offer an important semblance of neutrality and procedural justice where as active involvement may elicit a number of moral and ethical questions and minimise concerns about breaking the trust between doctor and patient (Ornelas-Dorian et al., Reference Ornelas-Dorian, Torres, Sun, Aleman, Cordova, Orue, Taira, Anderson and Rodriguez2021). That is, given the accepted role of healthcare providers as healers (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Molina and Saadi2019), respondents may likely be more comfortable supporting policies that appears as avoiding a direct involvement of healthcare providers in immigration enforcement tasks.

In short, respondents may be more supportive of policies that only require healthcare providers to fulfil administrative tasks like asking patients’ immigration status or marking the status on charts and bills as compared to those focused on reporting individuals or even actively assisting enforcement. We thus hypothesise the following:

H3: The policy focused on detention will elicit the lowest level of support followed by the policy focused on reporting requirements. Administrative policies (tracking, inquiring, marking) will elicit the most support.

Given that of the five policies, the requirement to assist immigrant enforcement serves as the clearest example of active involvement (as compared to administrative compliance) we expect that the results should be particularly stark in this case.

Partisanship & presidential vote choice

Given the increasing levels of polarisation and partisanship in the United States (Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021a, Reference Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021b; Van Bavel et al., Reference Van Bavel, Gadarian, Knowles and Ruggeri2024; Zingher, Reference Zingher2022), legal status is not only relevant as a social determinant of health, however. Political determinants of health, which result in unequal health outcomes as the result of deliberate political actions, is also relevant to healthcare access and outcomes for immigrants in the United States. Specifically, public health deteriorates as political polarisation increases and individuals become less likely to trust experts and more likely to trust party officials for health information (Haeder and Yackee, Reference Haeder and Yackee2025; SteelFisher et al., Reference SteelFisher, Findling, Caporello, Lubell, Vidoloff Melville, Lane, Boyea, Schafer and Ben-Porath2023; Van Bavel et al., Reference Van Bavel, Gadarian, Knowles and Ruggeri2024). Added to this context, decisions made by these political leaders then shape the conditions that make health more or less accessible to some portions of the population (Dawes, Reference Dawes2020). Political polarisation and the political determinants of health that can become exacerbated as a result, are particularly salient for those without legal status in the United States, a topic that has historically been highly controversial and only become more so in recent years (Anderson and Turgeon, Reference Anderson, Turgeon, Anderson and Turgeon2022; Blackburn and Haeder, Reference Blackburn and Haeder2024; Haeder and Moynihan, Reference Haeder and Moynihan2025; Kraut, Reference Kraut1995).

Political determinants of health manifesting through increased political polarisation can affect opinion formation and fluidity on issues that are highly polarised, such as immigration. Previous research argues that political parties are critical to policy-decision making among citizens (Leeper and Slothuus, Reference Leeper and Slothuus2014) and the elites of those parties are responsible for framing and influencing the opinions of party members on particular political issues (Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021a). This deference to party elites contributes to polarisation on issues that may have traditionally been considered apolitical (Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021b) and partisan issues become increasingly polarised as individuals start to villainise the people and opinions of the opposing party (Bankert, Reference Bankert2024). This literature suggests that American views on immigration policy are particularly vulnerable to the framing of elites and extreme polarization.

In the current hyper-partisan political environment, partisanship and vote choice serve as crucial determinants of policy positions (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960; Downs, Reference Downs1957; Mondak, Reference Mondak1993; Schaffner and Streb, Reference Schaffner and Streb2002; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992). Additionally, Zingher (Reference Zingher2022) argues that much of the hyper-partisan environment is driven by political elites. Within this framing, voting is driven by these elites seeking to mobilise their most dedicated and extreme voters (Zingher, Reference Zingher2022). Therefore, the political messaging for everything from singular policy issues to overall presidential approval rates is driven largely by the partisan framing of elites and the support this drives from the most extreme members of the voter base provides little incentive for elites to moderate their messaging (Harrison, Reference Harrison2016; Robison, Reference Robison2023). There is substantial evidence that this is the case for Americans’ views of immigrants (Alamillo et al., Reference Alamillo, Haynes and Madrid2019; Chenane, Reference Chenane2022; Dzordzormenyoh and Boateng, Reference Dzordzormenyoh and Boateng2023; Knoll et al., Reference Knoll, Redlawsk and Sanborn2011; Merolla et al., Reference Merolla, Ramakrishnan and Haynes2013; Reich and Mendoza, Reference Reich and Mendoza2008; Sagir and Mockabee, Reference Sagir and Mockabee2023). This effect has increased over time (Baker and Edmonds, Reference Baker and Edmonds2021). We expect this to particularly hold true for such a salient issue as policies affecting individuals without legal status (Blackburn and Haeder, Reference Blackburn and Haeder2024). Moreover, issues related to health policy have proven particularly partisan (Bussing et al., Reference Bussing, Patton, Roberts and Treul2020; Haeder and Chattopadhyay, Reference Haeder and Chattopadhyay2022; Haeder and Moynihan, Reference Haeder and Moynihan2023; Jacobs and Mettler, Reference Jacobs and Mettler2020; Oberlander, Reference Oberlander2020; Sances and Clinton, Reference Sances and Clinton2021; Wang, Reference Wang2022). Unsurprisingly, conservatives and Republicans have been identified as more anti-immigrant than liberals and Democrats in a number of different circumstances (Cadena Jr., Reference Cadena2023; Dzordzormenyoh and Boateng, Reference Dzordzormenyoh and Boateng2023; Willnat et al., Reference Willnat, Ogan and Shi2023). These effects may be particularly strong based not only on traditional partisanship but also whether a respondent voted for President Trump in the most recent presidential election given the policy positions of the candidates (Alamillo et al., Reference Alamillo, Haynes and Madrid2019; Sagir and Mockabee, Reference Sagir and Mockabee2023; Woolhandler et al., Reference Woolhandler, Himmelstein, Ahmed, Bailey, Bassett, Bird, Bor, Bor, Carrasquillo and Chowkwanyun2021). We hence hypothesise that:

H4a: Democrats will be less supportive of the policies than Republicans.

H4b: Those who did not vote for President Trump will be less supportive of the policies than those who voted for him.

Personal connection to individuals without legal status

There is limited research on the way that personal connections with undocumented individuals influence attitudes towards policies related to health, but there is more substantial literature examining how personal connections influence attitudes towards immigration policy more broadly. These studies find that having a personal connection to an individual who lacks legal status or who has been deported, increases the salience of immigration policies and political engagement (Roman et al., Reference Roman, Walker and Barreto2022; Sanchez et al., Reference Sanchez, Vargas, Walker and Ybarra2015). However, there is also evidence that personal connections play an important role in shaping attitudes about public policies, particularly as they are related to health. Personal connection may offer a better understanding of the policy effects on individuals, and they may encourage a more empathetic outlook (Addison and Thorpe, Reference Addison and Thorpe2004; Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, Kuwabara and O’Shaughnessy2009; Sattler et al., Reference Sattler, Escande, Racine and Göritz2017). For example, research by Grogan and Park (Reference Grogan and Park2017, Reference Grogan and Park2018) indicates that a connection to Medicaid increased support for the programme. At the same time, those with connections have also been found to be less tolerant of administrative burdens that reduce access (Haeder and Moynihan, Reference Haeder and Moynihan2024; Halling et al., Reference Halling, Herd and Moynihan2022). Other research suggest that personal connection may affect attitudes about other health issues (Haeder et al., Reference Haeder, Herd and Moynihan2025; Haeder et al., Reference Haeder, Sylvester and Callaghan2021; Sylvester et al., Reference Sylvester, Haeder and Callaghan2022). Lastly, personal connections are likely to provide individuals with direct information about the hardships experienced by undocumented individuals while reducing the effect of misinformation about them. We hence hypothesise the following:

H5: Those connected to undocumented immigrants will be less supportive of the policies than those not connected to undocumented immigrants.

Residence in border states

The literature also indicates that there are notable differences in attitudes towards immigrants based on geographic location within the United States. Studies have found that living in proximity to immigrant groups affects attitudes towards immigrants, though the directionality of this effect is mixed (Abrajano & Hajnal, Reference Abrajano and Hajnal2015; Berinsky et al., Reference Berinsky, Karpowitz, Peng, Rodden and Wong2023; Chan et al., Reference Chan, Raychaudhuri and Valenzuela2023; Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2010). Several studies found living in geographic locations with higher numbers of immigrants and their families leads to an increase in pro-immigrant attitudes (Berinsky et al., Reference Berinsky, Karpowitz, Peng, Rodden and Wong2023; Chan et al., Reference Chan, Raychaudhuri and Valenzuela2023), while other studies have found that living near immigrant populations is associated with negative attitudes of immigrants (Abrajano & Hajnal, Reference Abrajano and Hajnal2015; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Wong and Citrin2006; Enos, Reference Enos2016; Ha, Reference Ha2010; Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2010). For non-Hispanic Whites, living near Hispanic immigrants makes those individuals more likely to hold negative stereotypes (Ha, Reference Ha2010). However, there is no consensus in the literature about how living in geographic proximity to immigrants affects support for restrictive immigration policies. Some studies have found that it influences views of immigration policies (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Wong and Citrin2006; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Velez, Hartman and Bankert2015), while others have shown it has little effect (Hopkins et al., Reference Hopkins, Sides and Citrin2019; Swire-Thompson et al., Reference Swire-Thompson, Ecker, Lewandowsky and Berinsky2020). However, sudden changes in the number of immigrants in a population or community increases hostile views of immigrants (Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2010). Based on the literature related to geographic location and attitudes towards immigrants and immigrant policy as well as the substantial increase in undocumented immigrants along the southern border of the United States (CA, NM, AZ, TX), it seems plausible that attitudes of individuals living in border states may differ from those in other geographic areas. However, as the literature is mixed in this regard, we do not have a clear hypothesis.

Data & methods

Data

To assess public attitudes about requirements for healthcare providers related to individuals who lack legal status, we programmed an original survey in Qualtrics and relied on Lucid to recruit respondents. Lucid hosts a large, online, double opt-in panel and offers respondents various incentives to complete surveys. Lucid was compensated $1.50 per completed response. Data generated from Lucid’s pool has been validated and is generally considered to be of high quality (Coppock and McClellan, Reference Coppock and McClellan2019; Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Mercer, Keeter, Hatley, McGeeney and Gimenez2016; Stagnaro et al., Reference Stagnaro, Druckman, Berinsky, Arechar, Willer and Rand2024). It has been frequently used in work related to social science, health, and politics (Stagnaro et al., Reference Stagnaro, Druckman, Berinsky, Arechar, Willer and Rand2024). They survey was fielded from 7 March to 26 March 2025. Overall, 6948 US adults opted into the survey (18 years or older) and 6651 consented to take the survey. Of these, 6049 completed the survey. Lucid has implemented a pre-survey attention screener to ensure data quality. Lucid relies on quota sampling to ensure a sample that approaches national population benchmarks on gender, race, income, and education. We further improved fit by utilising weights based on the US Census Current Population Survey (for further details see Appendix Exhibits 1 & 2). This study was declared exempt by the appropriate Institutional Review Board.

Survey design and dependent variables

Treatments

Prior to exposing respondents to our survey experiment, we introduced all respondents to the topic as follows:

First, we would like to ask you about certain policies related healthcare access and undocumented immigrants.

The survey contained a control group which did not receive any additional information as well as six distinct treatments for a total of seven tracks (see Appendix 3). Of the six treatments, two focused specifically on the effect of various policies on the individuals without legal status and their families including highlighting (1) negative effects on healthcare access for the individual without legal status and (2) negative effects for their children and other family members who “who are US citizens.” These effects have been described extensively in the popular press (Chang, Reference Chang2023; Figueiredo, Reference Figueiredo2024) as well as in the academic literature (Abraham, Reference Abraham2018; Martinez et al., Reference Martinez, Wu, Sandfort, Dodge, Carballo-Dieguez, Pinto, Rhodes, Moya and Chavez-Baray2015; Philbin et al., Reference Philbin, Flake, Hatzenbuehler and Hirsch2018; Rhodes et al., Reference Rhodes, Mann, Simán, Song, Alonzo, Downs, Lawlor, Martinez, Sun and O’Brien2015; White et al., Reference White, Yeager, Menachemi and Scarinci2014).

Two of the treatments raised potentially negative consequences for the broader community. This included (3) public health threats for outbreaks of contagious diseases “like the bird flu also known as H5N1 or avian influenza” or (4) the negative effect on the food supply “from sick and ill undocumented immigrants [who] will handle foods as farm workers or in food processing plants.” In both cases, the role of individuals without legal status was intentionally described as “threatening.” These types of concerns issues have been common in the public discourse in the United States (Alexander, Reference Alexander2009; Willingham, Reference Willingham2020) (New York Times Editorial Board, 2020) and analysed in academic writing (Bloodsworth-Lugo and Lugo-Lugo, Reference Bloodsworth-Lugo and Lugo-Lugo2020; Kraut, Reference Kraut1995; Markel and Stern, Reference Markel and Stern2002; Matthew et al., Reference Matthew, Monaghan and Luque2021; Munsiff, Reference Munsiff2007).

Lastly, two treatments also focused on broader effects on the community but the role of individuals without legal status was not described as contributing to the threat. This included negative effects due to workforce shortages (5) on the food supply and (6) on the economy. Similar to the other treatments, these frames have been part of the public debate and presented in the news (Chadde, Reference Chadde2025; Gurley, Reference Gurley2025; Liu and Lakhani, Reference Liu and Lakhani2025; Ma, Reference Ma2025; Public Policy Institute of California, 2020), as well as academic writing (Gutiérrez-Li, Reference Gutiérrez-Li2025; Gutiérrez-Li and Rubalcaba, Reference Gutiérrez-Li and Rubalcaba2025; Kostandini et al., Reference Kostandini, Mykerezi and Escalante2014; Rauf et al., Reference Rauf, Sekercioglu and Koc2021; Ross et al., Reference Ross, Desiderio, St. Mars and Rangel2021).

Outcome variables

After the treatment, we queried respondents about five policies related to healthcare providers and requirements related to individuals who lack legal status. First, we asked respondents about whether hospitals and other healthcare providers should track how many undocumented patients that they provide care to. Subsequently, respondents were asked whether healthcare providers should be required to ask for a patient’s immigration status before providing care, whether they should be required to note a patient’s immigration status on medical charts and medical bills, and whether they should be required to report undocumented immigrants they treat to immigration enforcement. Lastly, we asked respondents whether healthcare providers should be required to assist immigration enforcement in detaining undocumented immigrants. In all cases, respondents were offered a 5-point scale from “strongly oppose” to “strongly support” with a neutral mid-point. For details on the various questions, see Appendix 4.

Subgroups

Based on the literature, we identified several subgroups worth analysing. Our first group of interest is based on respondent partisanship. We relied on the standard 7-point measure to determine the partisanship of respondents. We then combined the three levels of Democratic and Republican respondents (strong, weak, lean). Analyses based on partisanship may hold important information as recent research suggest that public health messages are often filtered through a partisan lens, with Republicans less likely to respond to these cues (Gadarian et al., Reference Gadarian, Pepinsky and Goodman2022; Van Bavel et al., Reference Van Bavel, Gadarian, Knowles and Ruggeri2024). Because of the aforementioned prominent role of President Trump in immigration policy, we also created a dichotomous variables based on whether respondents indicated that they voted for President Trump in the 2024 presidential election. We also asked respondents about their current state of residence and then coded the four states (California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas) along the US southern border as border states. Lastly, we also queried respondents whether they or anyone close to them “lack[ed] legal status in the United States (are an ‘undocumented immigrant’).” We specifically relied on this wording to account for the sensitive nature of the response. That is, the question choice allowed individuals without legal status to provide an affirmative answer without specifically identifying themselves as such. For further details on the survey questions to derive these variables, see Appendix 5.

Methods

The data for the analyses were generated from a survey experiment where respondents were randomly assigned to one of six treatment groups or a control group (Appendix 2). As a result, we estimated a series of weighted least square models (WLS), one for each of our five outcomes (policies), that included an indicator for the treatment group utilising the aforementioned survey weights to make comparisons across treatments. For our subgroup analyses, we interacted the treatment indicator with indicators for partisanship, presidential vote, residence in a border state, or personal connection to a person without legal status, respectively. We then relied on comparisons of predicted means to assess statistical differences using mlincom in Stata (Cameron and Trivedi, Reference Cameron and Trivedi2010; Long and Freese, Reference Long and Freese2014). We note that WLS estimation over ordered logit models to facilitate comparisons, interpretation, and presentation of results, as is a common approach. We considered a p-value lower than 0.05 as statistically significant throughout our analyses.

Results

Descriptive findings

Overall, we found that Americans were very much divided with regard to the five policies we queried them about, with just one policy being supported or opposed by a majority of respondents (Figure 1). That is, a small majority of 50.8% of respondents were (strongly or somewhat) opposed to requiring healthcare providers to assist immigration enforcement in detaining undocumented patients, with 30.5% in support (strongly or somewhat). At the same time, for two of the policies, we found that pluralities of respondents supported the policies. This included the tracking of the number of undocumented patients served which was supported by 45.4% of respondents and opposed by 34.2%, as well as the marking of immigration status on medical charts and bills which was favoured by 40.5% and opposed by 39.5% of respondents. Conversely, in the case of asking immigrants about their immigration status before providing care (35.6% in support and 47.1% in opposition) and reporting undocumented patients to immigration enforcement (38.8% in support and 43.6% in opposition) we found pluralities to be in opposition. For all five policies, about 1 in 5 respondents neither supported nor opposed the policy. Lastly, we note that the results for the six treated groups were remarkably similar to those of the control group (Appendix 7).

Figure 1. Distribution of support for five policies regarding healthcare providers and requirements related to individuals who lack legal status.

Notes: Based on a national survey of 6049 US residents from 7 March to 26 March 2025. The control group contained 859 respondents. Respondents were asked whether they supported the following policies. Results only shown for control group. Additional results are displayed in the appendix. (1) Some have proposed for all hospitals and other healthcare providers to track how many undocumented patients that they provide care to (Track); (2) Some have proposed to requiring hospitals and other healthcare providers to ask for a patient’s immigration status before providing care (Ask Status); (3) Some have proposed to requiring hospitals and other healthcare providers to note a patient’s immigration status on medical charts and medical bills (Mark Status); (4) Some have proposed to requiring hospitals and other healthcare providers to report undocumented immigrants they treat to immigration enforcement (Report); (5) Some have proposed to requiring healthcare providers and staff to actively assist immigration enforcement in detaining undocumented immigrants (Assist). Respondents were provided with a 5-point scale for each question.

Experimental findings

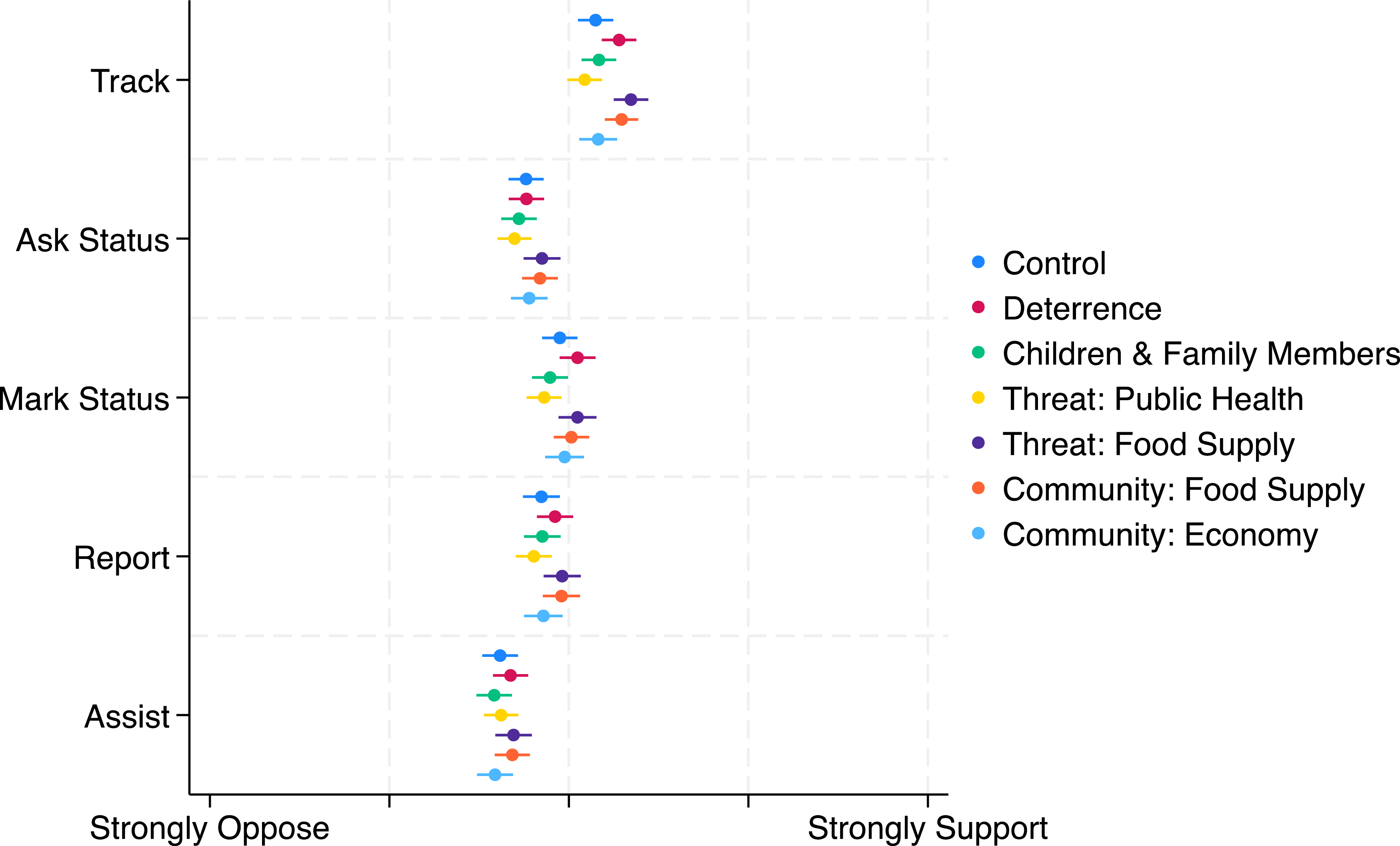

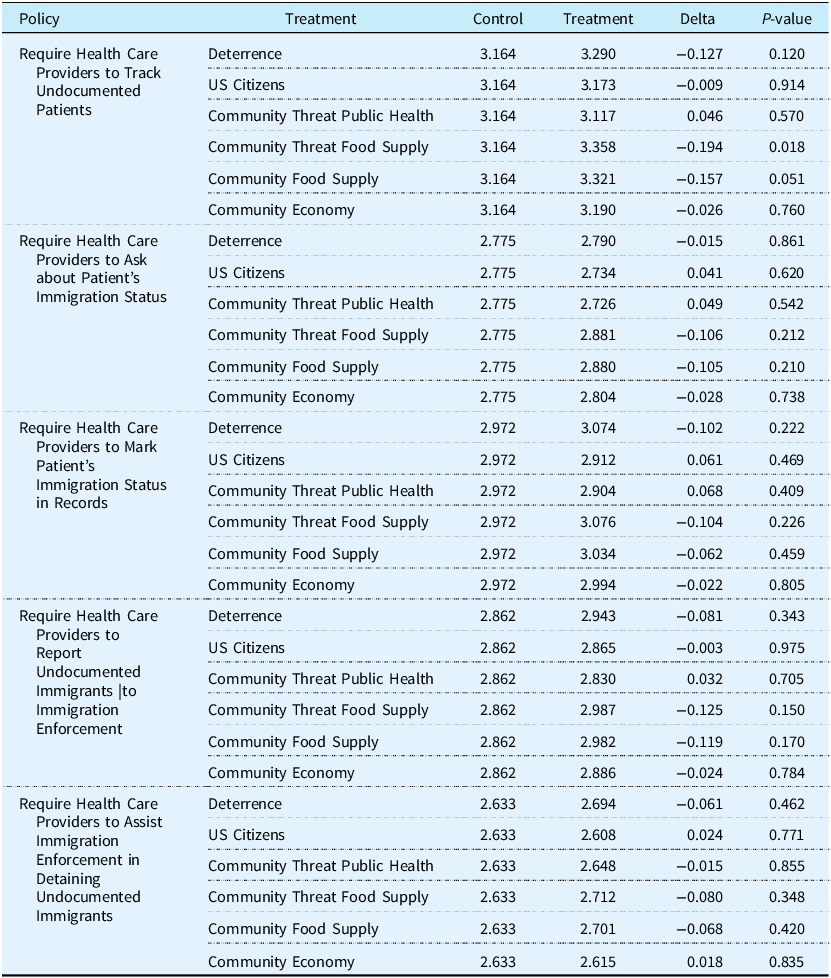

As noted above, our primary interest was to determine whether public attitudes about the various policies was movable when respondents were provided with additional information about the effect of these policies on immigrants and their families or the broader community as well as whether attitudes on this issue are by and large immovable. Overall, we found that the latter was the case. Comparing the control group to all six treatments, we found no support for our first hypothesis that any of the treatments lowered support for any of the policies respondents were queried about (Table 1, Figure 2). For policies focused on administrative tasks, differences between the control group and the various informational treatments ranged from 0.026 to 0.157 (p ≥ 0.051) with regard to tracking undocumented immigrants, 0.015 to 0.106 (p ≥ 0.210) with regard to asking patients about their immigration status, and 0.022 to 0.104 (p ≥ 0.222) with regard to documenting patients’ immigration status in records. The sole statistically significant difference we identified for was the informational treatment focused on threats to the food supply (0.194, p = 0.018). However, accounting for the number of hypotheses tested would have rendered this finding statistically insignificant, as well. We also could not identify any differences for the two policies that required healthcare providers to become more involved in the immigration enforcement process. Here, differences ranged from 0.003 to 0.125 (p ≥ 0.150) for reporting requirements and 0.015 to 0.080 (p ≥ 0.348) for assisting requirements.

Figure 2. Predicted mean levels of support for five policies regarding healthcare providers and requirements related to individuals who lack legal status.

Notes: Based on a national survey of 6049 US residents from 7 March to 26 March 2025. Respondents were asked whether they supported the following policies. (1) Some have proposed for all hospitals and other healthcare providers to track how many undocumented patients that they provide care to (Track); (2) Some have proposed to requiring hospitals and other healthcare providers to ask for a patient’s immigration status before providing care (Ask Status); (3) Some have proposed to requiring hospitals and other healthcare providers to note a patient’s immigration status on medical charts and medical bills (Mark Status); (4) Some have proposed to requiring hospitals and other healthcare providers to report undocumented immigrants they treat to immigration enforcement (Report); (5) Some have proposed to requiring healthcare providers and staff to actively assist immigration enforcement in detaining undocumented immigrants (Assist). Respondents were provided with a 5-point scale for each question.

Table 1. Predicted mean levels of support for five policies regarding healthcare providers and requirements related to individuals who lack legal status, control versus treatments

Notes: Based on a national survey of 6049 US residents from 7 March to 26 March 2025. Respondents were asked whether they supported the following policies. (1) Some have proposed for all hospitals and other healthcare providers to track how many undocumented patients that they provide care to (Track); (2) Some have proposed to requiring hospitals and other healthcare providers to ask for a patient’s immigration status before providing care (Ask Status); (3) Some have proposed to requiring hospitals and other healthcare providers to note a patient’s immigration status on medical charts and medical bills (Mark Status); (4) Some have proposed to requiring hospitals and other healthcare providers to report undocumented immigrants they treat to immigration enforcement (Report); (5) Some have proposed to requiring healthcare providers and staff to actively assist immigration enforcement in detaining undocumented immigrants (Assist). Respondents were provided with a 5-point scale for each question.

In short, across all five policies, highlighting the potential effects on immigrants and their families or the broader community did not significantly alter attitudes about the policies. In order to ensure that that the treatment did not have effects specific to certain subgroups we also assessed treatment effects for various demographics of interest. The findings from these subgroup analyses further confirmed the findings derived from all respondents based on partisanship, presidential vote choice, personal connections, and residence in border states (Appendices 8–15). That is, treatments did not move opinions across all respondents nor for various demographics of interest.

Moreover, we found no evidence for our second hypothesis treatments that had expected that highlighting the effects of the policies on immigrants will elicit the strongest support while those focused on effects on the community will elicit the weakest support (Appendices 16 & 17).

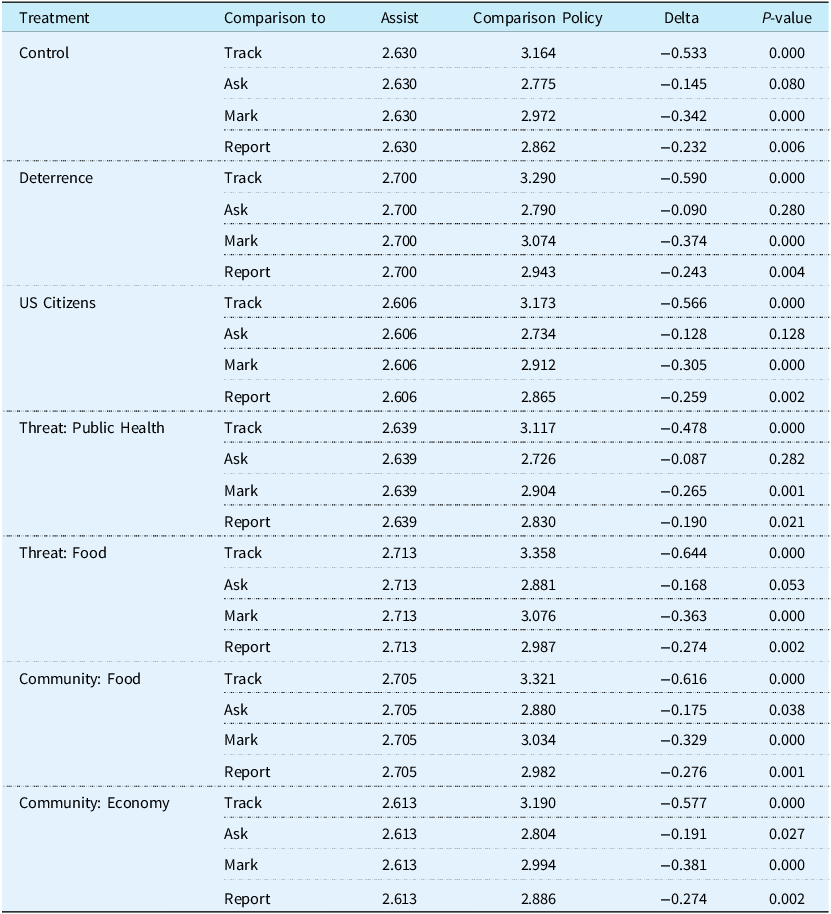

However, we found some limited confirmation for our third hypothesis that expected differential attitudes based on the objective intensity of the policies (Table 2 & Appendix 18). That is, respondents were generally less supportive of requiring healthcare providers to actively assist law enforcement in detaining individuals without status as compared to the more administrative tasks of tracking care provided to them. Across treatments, differences ranged from 0.478 to 0.644 (p < 0.001) in comparison to tracking the number of patients without legal status, 0.175 to 0.191 (p < 0.039) in comparison to asking about patients’ immigration status, 0.265 to 0.381 (p < 0.002) in comparison to marking patients’ status on medical charts and bills, and 0.190 to 0.276 (p < 0.022) in comparison to reporting requirements. However, we only found difference comparing the requirement to assist undocumented patients to law enforcement to requiring asking patients about their immigration status for the control group and treatments focused on impacts on the food supply and economy.

Table 2. Predicted mean levels of support for policies regarding healthcare providers and requirements related to individuals who lack legal status, comparing requirement to assist versus other policies

Notes: Based on a national survey of 6049 US residents from 7 March to 26 March 2025. Respondents were asked whether they supported the following policies. (1) Some have proposed for all hospitals and other healthcare providers to track how many undocumented patients that they provide care to (Track); (2) Some have proposed to requiring hospitals and other healthcare providers to ask for a patient’s immigration status before providing care (Ask Status); (3) Some have proposed to requiring hospitals and other healthcare providers to note a patient’s immigration status on medical charts and medical bills (Mark Status); (4) Some have proposed to requiring hospitals and other healthcare providers to report undocumented immigrants they treat to immigration enforcement (Report); (5) Some have proposed to requiring healthcare providers and staff to actively assist immigration enforcement in detaining undocumented immigrants (Assist). Respondents were provided with a 5-point scale for each question.

The comparisons of the reporting requirements to the three other more administratively focused policies (Appendix 18) only identified statistically significant differences with the tracking requirement ranging from 0.288 to 0.370 (p < 0.002).

In terms of differences between various subgroups, as expected, we identified consistent and substantial differences based on partisanship, with Democrats substantially more opposed to the various policies than Republicans (Hypothesis 4a, Appendix 19, Figure 3). Differences ranged from 1.071 to 1.648 (p < 0.001). Similarly large differences were present based on presidential vote choice with Trump voters more favourable (Hypothesis 4b, Appendix 20, 1.002 to 1.482, p < 0.001). However, we were unable to identify any differences between respondents living in border states and those living in other parts of the country (Appendix 21, Figure 4). With only a handful of exceptions, this was also the case comparing respondents with personal connections to individuals without legal status to those without those connections (Hypothesis 5, Appendix 22). Based on the findings related to personal connections, we conducted two additional exploratory analyses based on whether respondents were born outside the United States or not (Appendix 23) and whether respondents exhibit low or high degrees of sympathy towards individuals without legal status (Appendix 24). We again found consistent and substantive differences for the latter (1.171 to 1.985, p < 0.001). Moreover, found more mixed differences based on place of birth.

Figure 3. Predicted mean levels of support for five policies regarding healthcare providers and requirements related to individuals who lack legal status, by partisanship.

Notes: Based on a national survey of 6049 US residents from 7 March to 26 March 2025. Respondents were asked whether they supported the following policies. (1) Some have proposed for all hospitals and other healthcare providers to track how many undocumented patients that they provide care to (Track); (2) Some have proposed to requiring hospitals and other healthcare providers to ask for a patient’s immigration status before providing care (Ask Status); (3) Some have proposed to requiring hospitals and other healthcare providers to note a patient’s immigration status on medical charts and medical bills (Mark Status); (4) Some have proposed to requiring hospitals and other healthcare providers to report undocumented immigrants they treat to immigration enforcement (Report); (5) Some have proposed to requiring healthcare providers and staff to actively assist immigration enforcement in detaining undocumented immigrants (Assist). Respondents were provided with a 5-point scale for each question.

Figure 4. Predicted mean levels of support for five policies regarding healthcare providers and requirements related to individuals who lack legal status, by residence.

Notes: Based on a national survey of 6049 US residents from 7 March to 26 March 2025. Respondents were asked whether they supported the following policies. (1) Some have proposed for all hospitals and other healthcare providers to track how many undocumented patients that they provide care to (Track); (2) Some have proposed to requiring hospitals and other healthcare providers to ask for a patient’s immigration status before providing care (Ask Status); (3) Some have proposed to requiring hospitals and other healthcare providers to note a patient’s immigration status on medical charts and medical bills (Mark Status); (4) Some have proposed to requiring hospitals and other healthcare providers to report undocumented immigrants they treat to immigration enforcement (Report); (5) Some have proposed to requiring healthcare providers and staff to actively assist immigration enforcement in detaining undocumented immigrants (Assist). Respondents were provided with a 5-point scale for each question.

Discussion

We administered a national survey to assess public attitudes about various policies affecting healthcare providers and how they relate to individuals who lack legal status in the United States. Such policies, some of which have been implemented by several states, present a substantial departure from the long-standing status quo separating healthcare from immigration enforcement. Importantly, they blur the line between the provision of healthcare and the immigration policy, and they do so by enmeshing healthcare providers in immigration enforcement, raising substantial legal, moral, and ethical issues. Importantly, more policy changes of these sorts may be on the horizon at both the federal and state levels given the growing levels of polarisation and partisanship across the country. To our knowledge, this study is the first to assess public attitudes on this important emerging policy issue and thus makes an important contribution from a policy and governance perspective.

Overall, we found a divided public on the topic, with only a majority, albeit a very slim one, favouring opposition in the case of requiring healthcare providers to actively assist immigration enforcement in detaining patients. In addition, pluralities supported two of the policies (tracking of overall patient counts and marking patient status on bills and charts) and opposed the two other policies (asking about immigration status and reporting undocumented patient to immigration enforcement). This finding indicates that a substantial number of Americans are willing to blur the lines between immigration policy and enforcement and the provision of healthcare, and, crucially, to actively engage healthcare providers in immigration enforcement.

In addition, we found that highlighting the effects of these policies on the individual without legal status or the broader community did not significantly impact attitudes about the various policies. Various subgroup analyses failed to identify any significant changes, as well. Moreover, we did not find any differences comparing primes focused on the effect of the policies on immigrants compared to those with broader effects on the community including such important issues as the food supply or the economy, and whether those changes presented immigrants as a threat. These findings depart from the previous literature which demonstrated that individual’s attitudes towards immigrants are not fixed and, instead, change based on informational cues or the framing that they are presented (Avdagic and Savage, Reference Avdagic and Savage2024; Kahneman and Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979; Norris, Reference Norris2021). This is especially true for individuals who identify with right-wing ideologies when presented with threat framing (Homola, Reference Homola2021; Oxley et al., Reference Oxley, Smith, Alford, Hibbing, Miller, Scalora, Hatemi and Hibbing2008) and that all individuals are more receptive to the framing of information that matches their existing partisan views (Slothuus and De Vreese, Reference Slothuus and De Vreese2010).

The lack of findings raises the question of whether this politically salient topic has emerged as a policy issue with hardened opinions and attitudes which remain largely unmovable by interventions, framing, and learning. That is, it is plausible that immigration-related policies, whether they focus on healthcare or other issues such as schooling or deportation, may have become so deeply partisan that, in the hyper-polarised environment that we experience today, attitudes are virtually predetermined. With Republican elites cueing their followers to support anti-immigrant and anti-immigration policies, Republicans in the populations might be unwilling or unable to adjust their attitudes, even when confronted with novel information or when they might experience negative effects in their own lives. Conversely, the inverse might hold for Democrats, of course. In this way, the findings may very much resemble those on the Affordable Care Act (Haeder, Reference Haeder2026; Haeder and Chattopadhyay, Reference Haeder and Chattopadhyay2022; Haeder and Sylvester, Reference Haeder and Sylvester2024; Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2023).

Indeed, there is some evidence to support the importance that partisan effects may have on impeding the movability of public attitudes, particularly for controversial topics. For example, numerous experimental design studies on controversial issues such as immigration and climate change have found that partisan cues override framing effects of media or news framing (Diamond, Reference Diamond2020; Ehret et al., Reference Ehret, Van Boven and Sherman2018; Magistro et al., Reference Magistro, Debnath, Wennberg and Michael Alvarez2025). Specifically, partisan individuals tend to process information in a biased way if the information source is not considered part of their partisan in-group (Diamond, Reference Diamond2020; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Su and Chen2023). Moreover, one study found that the effect of partisan cues in reducing the impact of framing effects is larger for Republicans than for Democrats, with framing effects completely disappearing among Republicans when they were first primed with their partisan identity (Diamond, Reference Diamond2020). Other studies have found that the size of framing effects is dependent both on the type for frame and the source of the information because individuals will interpret frames on partisan issues through the lens of their political orientation (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Su and Chen2025).

While these studies have highlighted the power of partisan informational cues above media framing effects, all of these studies presented participants with an explicit partisan frame such as naming the information source as a Republican politician or stated that the information came from a mainstream or conservative media site, which our study did not. Notably, these studies found that framing effects disappeared with partisan priming, suggesting that partisan information cues in these instances were not salient enough to reduce framing effects in the absence of the specific partisan priming. Our study, however, did not include specific partisan priming, yet demonstrated no significant framing effect on the highly salient and polarised issue of immigration.

Given our findings, new interesting questions about the interplay between partisan cues and public attitudes emerge, particularly for highly salient and polarising issues and here particularly for the second Trump administration. For example, it seems plausible that issues that have been at the core of President Trump’s agenda including immigration, diversity, equity, and inclusion, or government reform of the “deep state” may have emerged as relatively immutable to new information anchored in partisanship as compared to issues the president has focused little attention on such as rural development or housing. Over the long term, it is also worth exploring whether these issues once again become more susceptible to changes in attitudes as the president’s focus diminished or as the current administration leaves office. Put differently, is there something unique about polarisation and partisanship with regards to President Trump or are these effects generalised at this point. Lastly, President Trump’s own policy decisions might offer additional opportunities to re-assess attitudes related to immigration, in general and framing effects in particular, by focusing on the one group of immigrants strongly support by the president, white Afrikaner South Africans (Kanno-Youngs and Aleaziz, Reference Kanno-Youngs and Aleaziz2025).

An additional finding was that respondents, to a degree, differentiated between policies focused on administrative tasks like record keeping and more active involvement of healthcare providers and that these policy differences had some impact on respondents’ attitudes towards the policies. Specifically, respondents generally differentiated between the requirement to assist in detaining immigrants and the other four policies including administrative tasks of documenting and tracking individuals without legal status and the requirements to report individuals without legal status. At the same time, respondents only differentiated between the reporting requirement and one of the administrative tasks, the tracking of the number of undocumented patients that they provide care to. In short, public support was largest for the tracking requirement and lowest for the assisting requirement, with the three other policies indistinguishable in between the two policies.

Lastly, we found substantial differences in attitudes towards the policies based on partisanship, with respondents who identified as Democrats more strongly opposed to the policies than respondents who identified as Republican, and those who voted for President Trump in 2024 more supportive than those who did not. This finding supports previous literature which demonstrates that the crucial role that immigration plays in the partisan politics today (Abrajano & Hajnal, Reference Abrajano and Hajnal2015; Ayasli, Reference Ayasli2024; Baker and Bader, Reference Baker and Bader2022; Blackburn and Haeder, Reference Blackburn and Haeder2024; Kuntz et al., Reference Kuntz, Davidov and Semyonov2017; Pardos-Prado and Xena, Reference Pardos-Prado and Xena2019). Surprisingly, we found no differences between individual living in border states as compared to those who live in other parts of the country. We also did not find differences between those respondents with close connection to individuals without legal status and those who did not have those connections.

There are several limitations that apply to our study. First, our survey was cross-sectional and can only provide a one-time assessment of Americans attitudes towards these policies. Importantly, the survey was administered in March 2025, which was a time when immigration-related issues were particularly salient in American politics. The timing of the survey could have contributed to the findings that partisanship and having voted for President Trump in the 2024 election were the largest predictors of attitudes towards these policies. It could also help to explain the limited statistically significant findings between healthcare providers collecting immigration status and healthcare providers actively assisting immigration enforcement because public opinions for such a salient policy issue may not be movable by interventions like ours. Of course, it is also plausible that respondents discounted the information provided. As in all survey, specific wording choices in the treatments or questions may also affect respondents’ perceptions. We note the limited research on this topic which offered only limited guidance. Moreover, we note that future work, as more states may pursue these types of policies, should add further nuances to our assessments here. This includes assessing the effect of the effect of the intensity of the reporting restrictions on state residents as well as the degree of policy congruence (or lack thereof) between state policies and state residents.

Methodologically, we utilised an online, non-probability platform. While this is common practice in survey research, we used weighting and attention checks to mitigate some of the known concerns with this data collection method. Additionally, this method of data collection is frequently used in this type of work and is considered high quality and Lucid has been recommended a recent comprehensive review (Coppock and McClellan, Reference Coppock and McClellan2019; Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Mercer, Keeter, Hatley, McGeeney and Gimenez2016; Stagnaro et al., Reference Stagnaro, Druckman, Berinsky, Arechar, Willer and Rand2024).

Despite these limitations, examining public attitudes about the reporting requirements of healthcare providers related to individuals who lack legal status in the United States is central to conceptualising the swift shift of federal and state-level policy around immigration broadly, and healthcare access for those without legal status more specifically. Our findings suggest that the salience and partisanship of this issue have hardened American attitudes whereas framing effects are limited. Further study is needed to understand the full scope of these hardened attitudes and opinion and the extent to which they result from the timing of the survey compared to representing a notable shift in American attitudes.

Conclusion

State-level laws that require healthcare providers to document the immigration status of their patients is part of a growing trend in many states to impose restrictive policies on individuals without legal status (Torche and Sirois, Reference Torche and Sirois2019). In a time where individuals without legal status already face a number of barriers to health coverage and access to healthcare (Pillai et al., Reference Pillai, Artiga, Hamel, Schumacher, Kirzinger, Presiado and Kearney2023), these new policies could create an additional damper on their health-seeking behaviour and ultimately lead to increases in negative health outcomes and disparities. Anti-immigrant rhetoric in the broader policy environment has already contributed to this type of chilling effect (Blackburn and Sierra, Reference Blackburn and Sierra2021; Woolhandler et al., Reference Woolhandler, Himmelstein, Ahmed, Bailey, Bassett, Bird, Bor, Bor, Carrasquillo and Chowkwanyun2021). While various of these policies have been denounced by the American Medical Association (AMA) and the AMA Code of Medical Ethics (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Molina and Saadi2019), significant changes in the role of healthcare providers may be on the horizon. More generally, the trend towards stricter immigration enforcement, even in healthcare settings, indicates a profound shift in the US policy environment.

Importantly, the findings of our study suggest that there is a possible change in the American social norms that traditionally supported ensuring healthcare access for individuals who need it and protections in certain sensitive locations (Abraham, Reference Abraham2018; Haeder, Reference Haeder2019). The increased salience of immigration and the possible hardening of partisan attitudes regarding acceptable enforcement policies as well as increased partisanship and polarisation are likely to create new challenges for healthcare providers, as there are more than 11 million undocumented immigrations in the United States and an additional 5.1 million US citizen children with at least one undocumented parent (Baker and Warren, Reference Baker and Warren2024). Our findings suggest that in a policy environment in which immigration is highly salient, public opinion on this issue is hard to move, highlighting likely negative outcomes associated with these policies – even negative effects on communities, society, and the economy have little influence on American public attitudes towards policies.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744133125100364

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

No outside support was obtained to support this work

Competing interests

No disclosures to report.