As part of a healthy lifestyle, functional foods can have a positive health benefit beyond their basic nutritional components, including reducing the risk of chronic disease, and are an established feature of the food industry (Ghazanfari et al., Reference Ghazanfari, Falah, Yazdi, Behbahani and Vasiee2024). In this context, foods containing probiotics have gained attention in the dairy food industry (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Zhou, Zhang, Du, Tu, Wu, Zeng, Dang, Liu, Pan and Liu2025).

Probiotics are live microorganisms that have positive medicinal benefits for the digestive system, such as lowering cholesterol, improving lactose intolerance, preventing infections, and stimulating immunity (Abdel-Hamid et al., Reference Abdel-Hamid, Hamed, Walker and Romeih2024). Health-conscious people often prefer probiotic products that contain the beneficial bacteria Lactobacilli (Alvardo et al., Reference Alvarado, Ibarra-Sanchez, Mysonhimer, Khan, Cao, Miller and Holscher2024) and Bifidobacteria (Machado et al., Reference Machado, de Oliveira, Campos, de Assis, de Souza, Madruga, Pacheco, Pintado and Queiroga2017) which can be used to confer to produce a satisfactory quality and good acceptance by consumers (Meira et al., Reference Meira, Magnani, Júnior, Queiroga, Madruga, Gullon, Maria, Gomes, Pintado and de Souza2015). Thus, dairy products are good carriers for probiotics and other bioactive compounds (Mahmoudi et al., Reference Mahmoudi, Ben Moussa, Boulares, Chouaibi and Hassouna2022).

Yoghurt is recognized as the most popular and highly consumed fermented milk product worldwide (Ghaderi-Ghahfarokhi et al., Reference Ghaderi-Ghahfarokhi, Shakarami and Zarei2024). With growing consumer awareness of yoghurt, food manufacturers and researchers are increasingly focusing on developing functional yoghurt by incorporating nutritional value-added ingredients such as probiotics, prebiotics, and antioxidants (AbdiMoghadam et al., Reference AbdiMoghadam, Darroudi, Mahmoudzadeh, Mohtashami, Jamal, Shamloo and Rezaei2023).

Yoghurt is the most common delivery carrier of probiotic bacteria. Comprehensive evidence on the health benefits of probiotic yoghurt, including cancer prevention, improvement of glucose metabolism and reduction of cardiovascular disease have been provided (Meybodi et al., Reference Meybodi, Mortazavian, Arab and Nematollahi2020). To ensure a probiotic effect in the yoghurt matrix during processing, storage, and passage through the gastrointestinal, the dairy industry has adopted the minimum recommended level of 107 CFU/mL or g of product at the time of ingestion or 9 log CFU/mL or g per serving (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Guarner, Reid, Gibson, Merenstein, Pot and Calder2014) to exert health-promoting and therapeutic effects. A key strategy is incorporating prebiotic substances into yoghurt to support the growth and viability of probiotics.

Honey is a natural product with established therapeutic properties. It is produced worldwide by over 500 bee species described in 32 genera (Chuttong et al., Reference Chuttong, Chanbang, Sringarm and Burgett2016). The honey component itself is a functional food with potentially beneficial health properties (Berg and McCarthy, Reference Berg and McCarthy2022). Particularly, honey is naturally rich in metabolites of multifactorial origin, bioactive as an antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and anti-tumoral compounds (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Wu, Zhang, Wang, Zhang, Zhang and Mu2024). Also, it is endowed with a specific sugar profile and acidity that bestows unique sensory characteristics (Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Souza, Marques, Benassi, Gullon, Pintado and Magnani2016). Apis mellifera intermissa species already identified in Italy and North Africa is the most important bee species for honey production (Boussaid et al., Reference Boussaid, Chouaibi, Rezig, Hellal, Donsì, Ferrari and Hamdi2018; Utzeri et al., Reference Utzeri, Ribani, Taurisano and Fontanesi2022). In Tunisia honey has always had a valued place in traditional medicine. It has been principally employed in wound healing and diseases of the gut (Boussaid et al., Reference Boussaid, Chouaibi, Rezig, Hellal, Donsì, Ferrari and Hamdi2018).

Recently, some studies have focused on adding artificial sweeteners, fruit juices and pulps to yoghurt made from goat milk to mitigate goat aroma and aftertaste (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Frasao, Silva, Freitas, Franco and Conte-Junior2015). Honey may however be a better alternative than artificial flavours (Borba et al., Reference Borba, Silva, Madruga, Queiroga, Souza and Magnani2013) and improve their nutritional and sensory characteristics. Yet, studies about the use of honey as an ingredient in the formulation of yoghurt are still few, and to the best of our knowledge, no study is available about the incorporation of honey produced by the bee A. mellifera honey in a probiotic goat yoghurt. Considering the health claims of honey and probiotics and the opportunity to advance the technology of dairy foods based on goat milk with functional characteristics, the aim of this work was to study the physicochemical and microbiological parameters of stirred goat yoghurt adding different concentrations of honey during storage.

Materials and methods

Materials

The goat milk was collected from the Farm of Mateur (Bizerte, Tunisia). First, the milk was pasteurized at 65°C for 30 min and kept under refrigeration for up to 12 hours before yoghurt production. Apis mellifera intermissa wild multifloral honey was obtained from an OEP beekeeping centre in the city of Mraissa (Grombalia, Tunisia) in June, the highest honey production period with characteristic forest vegetation. For honey characterization, the pH, the ash, the protein, the glucose and fructose contents were determined as previously described by Boussaid et al. (Reference Boussaid, Chouaibi, Rezig, Hellal, Donsì, Ferrari and Hamdi2018). The mean values of the assessed physicochemical parameters of honey are shown in Table 1. It was then kept at room temperature overnight before preparing the yoghurt samples. The commercial freeze-dried yoghurt starter cultures Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus were purchased from Chr's Hansen (France) and the culture Lactobacillus plantarum C78 was isolated from goat milk as potential probiotic bacteria (Mahmoudi et al., Reference Mahmoudi, Ben Moussa, Khaldi, Kebouchi, Soligot-Hognon, Leroux and Hassouna2019) and inoculated into the milk as freeze-dried ferment.

Table 1. Physico-chemical parameters of Apis mellifera intermissa honey

Production of yoghurt and sample treatments

Yoghurt made of goat milk was produced according to Machado et al. (Reference Machado, de Oliveira, Campos, de Assis, de Souza, Madruga, Pacheco, Pintado and Queiroga2017) with minor modifications. The pasteurized goat milk was supplemented with 5% (w/v) sucrose and then heated at 90°C for 10 min. Next, it was cooled to 43°C, and the starter cultures and the probiotic culture (at 109 CFU/mL (in milk) = probiotic freeze-dried culture) were inoculated at a concentration of 1% then agitated uniformly (Fig. 1). Four different goat yoghurt formulations with different concentrations of honey (0%, 5 %, 10 %, and 15 %) were prepared. Fermentation was at 44°C for 4 h, and the end point of fermentation was based on verification of clot firmness and pH value of 4.5. Subsequently, the product was cooled to 4 ± 1°C, and the clot was broken by manual stirring with a glass rod. Honey was then added to the formulations as follows: (1) a control sample inoculated with probiotic culture (CPGY; 0% honey); (2) a yoghurt inoculated with probiotic culture and honey (5%) (PGY5%); (3) a yoghurt inoculated with probiotic culture and honey (10%) (PGY10%); (4) a yoghurt inoculated with probiotic culture and honey (15%) (PGY15%) under aseptic conditions, and the mixture was softly homogenized. Finally, all samples were put in 100 mL sterile high-density polyethylene bottles and stored at 4°C. All experimental yoghurt formulations were prepared in triplicate and they were subjected to physicochemical, technological and microbiological analyses after 1, 7, 14, 21 and 28 days of refrigerated storage, while sensory analyses were performed on the days 1, 14 and 28 of storage.

Figure 1. Probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt with adding honey process (Machado et al., Reference Machado, de Oliveira, Campos, de Assis, de Souza, Madruga, Pacheco, Pintado and Queiroga2017).

Biochemical and physicochemical analyses

The fat content was determined according to the Gerber method, protein was quantified using the Kjeldahl method, total solids and ash contents were determined according to the method of Bradley et al. (Reference Bradley, Arnold, Barbano, Semerad, Smith, Vines and Marshall1993), total sugars were quantified using the method 923.09 (Machado et al., Reference Machado, de Oliveira, Campos, de Assis, de Souza, Madruga, Pacheco, Pintado and Queiroga2017). The pH was measured with a Microprocessor pH-meter BT-500 (Boeco, Hamburg, Germany) and acidity was determined by titration and expressed as g/100 g (lactic acid/yoghurt).

Technological analysis

The colour parameters L*, a* and b* were measured using a Minolta CR-300 colorimeter (Minolta Chromameter Co, Ltd, Osaka, Japan). Susceptibility to syneresis was determined as recommended by (AOAC International, 2012). The water holding capacity (WHC) of experimental yoghurt was measured according to the procedure of Celik and Bakirci (Reference Celik and Bakirci2003). The apparent viscosity was determined using a viscometer (Rheomat RM-180, Germany) with coaxial cylinders. The shear rate was applied in the order of 30 s-1, which was taken as the apparent viscosity of yoghurt at 20 ± 2.6°C and the values are expressed in Pa.s (Mahmoudi et al., Reference Mahmoudi, Telmoudi, Ben Moussa, Chouaibi and Hassouna2021).

Microbiological analysis

The microbiological analysis of yoghurt was determined as outlined by Bradley et al. (Reference Bradley, Arnold, Barbano, Semerad, Smith, Vines and Marshall1993). Microbial counts were expressed as the log of the number of colony forming units per mL of yoghurt (log CFU/mL). For S. thermophilus M17 agar (Biokar Diagnostics, France) was used, with aerobic incubation at 44°C for 48 h; for L. bulgaricus MRS agar medium supplemented with cysteine (0.5 g/L) was used at 37°C for 48 h (Lima et al., Reference Lima, Kruger, Behrens, Destro, Landgraf and Franco2009); for probiotic culture L. plantarum C78 MRS agar supplemented with 4 mg of ciprofloxacin and 20 g of sorbitol was used at 37°C for 48 h (Bujalance et al., Reference Bujalance, Jiménez-Valera, Moreno and Ruiz-Bravo2006).

Sensory analysis

Sensory analysis of the different yoghurt formulations was performed on the day-1, day-14 and day-28 of storage. The yoghurt samples were subjected to tests of acceptance and relative preference as described by Machado et al. (Reference Machado, de Oliveira, Campos, de Assis, de Souza, Madruga, Pacheco, Pintado and Queiroga2017). In the acceptance test, well-known pre-established criteria were used. These tests were performed by 30 trained panellists. The tasting panel consisted of students and professors from the High School of Food Industry (ESIAT, Tunisia), pre-selected according to interest and with a habit of consuming stirred yoghurt. Each panellist was served 20 mL of each yoghurt sample on a small white glass at 6°C coded with a random three-digit number. The assessment of appearance, colour, flavour, taste, texture and overall acceptability were evaluated on a nine-point unstructured hedonic scale ranging from 9 (like very much) to 1 (dislike very much) (Mudgil et al., Reference Mudgil, Jumah, Hamed, Ahmed and Maqsood2018). Purchase intention was evaluated using a nine-point hedonic scale (9 = extremely like, 8 = very much like, 7 = moderately like, 6 = slightly like, 5 = neither like nor dislike, 4 = slightly dislike, 3 = moderately dislike, 2 = very much dislike, and 1 = extremely dislike).

Statistical analysis

All yoghurt formulations were conducted in triplicate and averaged for analysis and presentation. Two-way ANOVA was carried out to investigate the effects of honey concentration and storage period on goat yoghurt parameters (P < 0.05). Mean comparisons were performed using Tukey’s test (P < 0.05). All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS statistics 20.0 commercial software.

Results and discussion

Biochemical and physicochemical analyses

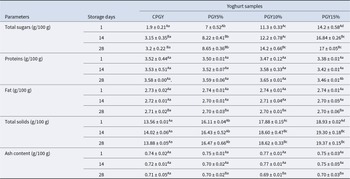

The mean values of the biochemical composition of probiotic stirred goat yoghurt are presented in Table 2. Protein concentrations were similar in all except the 15% samples on the first day of storage, possibly due to dilution from the higher amount of honey in PGYH15%. Regarding the fat content, there were no significant differences (P > 0.05) between yoghurt samples during storage. Similar findings to ours were obtained by Machado et al. (Reference Machado, de Oliveira, Campos, de Assis, de Souza, Madruga, Pacheco, Pintado and Queiroga2017).

Table 2. Biochemical composition of probiotic stirred goat-milk yoghurt with incorporation of honey during 28 days of refrigerated storage

CPGY – probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt(control); PGY5% – probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt containing honey at 5% (v/v); PGY10% – probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt containing honey at 10% (v/v); PGY15% – probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt containing honey at 15% (v/v); a-d Mean ± standard deviations with different lowercase letters in the same row denote difference among the different formulations, based on the Tukey's test (P < 0.05); A-B Mean ± standard deviations with different uppercase letters in the same column denote difference among the different storage periods, based on the Tukey’s test (P < 0.05).

In addition, an increase in the total carbohydrate content was observed at the end of the assessed storage period for all probiotic yoghurt samples (P < 0.05) (Table 2). The oligosaccharide content in honey samples has been shown to vary with the action of the bee enzyme α-D-glucosidase (Shin and Ustunol, Reference Shin and Ustunol2005). In fact, certain microbial enzymes in the goat-milk yoghurt may have similar actions toward honey sugars. Likewise, Machado et al. (Reference Machado, de Oliveira, Campos, de Assis, de Souza, Madruga, Pacheco, Pintado and Queiroga2017) reported the same sugar contents in goat yoghurt added with stingless bee honey. Moreover, bacteria are able to use the free glucose originally available as growth substrate, and eventually through the action of enzymes produced by lactic acid bacteria, they may release additional free sugar molecules to yoghurt formulated with honey. In contrast, the smallest increase in total sugar content in the control sample (CPGY) over the monitored storage period may be related to the use of sucrose as an ingredient with no honey addition. During the storage period, the yoghurt sample containing 15% added honey (PGY15%) presented higher (P < 0.05) total solids content, this is due to the higher amount of honey. Regarding the ash content, there was no difference (P > 0.05) between the probiotic yoghurt samples over the assessed storage period. These results were in line with those reported by Machado et al. (Reference Machado, de Oliveira, Campos, de Assis, de Souza, Madruga, Pacheco, Pintado and Queiroga2017).

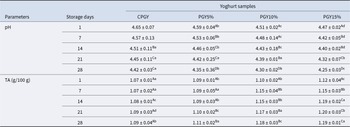

The mean values of pH and acidity of probiotic goat yoghurt samples are shown in Table 3. The addition of honey may have led to the slight reduction of the initial pH (0.2 units) in PGYH15% sample. The acidity of honey results from the naturally occurring organic acids in its composition (Alvarado et al., Reference Alvarado, Ibarra-Sanchez, Mysonhimer, Khan, Cao, Miller and Holscher2024). The initial pH of the assessed yoghurt formulations continuously decreased until day-28of storage, and the yoghurt samples containing honey exhibited lesser pH that was proportional to the honey amount in probiotic goat yoghurt to reach a final value ranging from 4.42 ± 0.03 to 4.25 ± 0.03 in CPGY and PGYH15% samples respectively.

Table 3. Physicochemical parameters of probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt within corporation of honey during 28 days of refrigerated storage

CPGY – probiotic goat stirred yoghurt (control); PGY5% – probiotic goat stirred yoghurt containing honey at 5% (v/v); PGY10% – probiotic goat stirred yoghurt containing honey at 10% (v/v); PGY15% – probiotic goat stirred yoghurt containing honey at 15% (v/v); a-d Mean ± standard deviations with different lowercase letters in the same row denote difference among the different formulations, based on the Tukey’s test (P < 0.05); A-D Mean ± standard deviations with different uppercase letters in the same column denote difference among the different storage periods, based on the Tukey’s test (P < 0.05).

At the same time, the acidity increased throughout the storage period in all yoghurt samples, with a very clear difference (P < 0.05) between control and PGYH15%, presenting the highest acidity values, containing 1.19 ± 0.01 g/100 g in PGYH5% sample at the end of the storage period (Table 3). A previous study with yoghurt containing added fruit observed a reduction in pH values during storage, indicating the increase of the acidity over time (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Zhou, Zhang, Du, Tu, Wu, Zeng, Dang, Liu, Pan and Liu2025).

Technological characteristics

Effects of honey supplementation at different concentrations on colour parameters for different goat yoghurt samples are presented in Table 4. The L* (brightness) value for all probiotic goat yoghurt samples decreased proportionally with the increased amount of honey with values of 91.04 ± 0.03 and 82.20 ± 0.00 on the first day, and reaching 90.85 ± 0.03 and 88.38 ± 0.06 at the end of the storage period in control and PGYH15% samples respectively, probably due to the presence of naturally occurring honey colour compounds (Alvarado et al., Reference Alvarado, Ibarra-Sanchez, Mysonhimer, Khan, Cao, Miller and Holscher2024). However, the brightness value decreased in yoghurt without added honey. The higher brightness values result in lighter objects (observed in all yoghurt samples (91.04–88.38)), which may be associated with the white colour characteristic of goat milk matching the colour of honey (Fazilah et al., Reference Fazilah, Ariff, Khayat, Rios-Solis and Halim2018).

Table 4. Technological parameters of probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt with incorporating of honey during 28 days of refrigerated storage

CPGY – probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt (control); PGY5% – probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt containing honey at 5% (v/v); PGY10% – probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt containing honey at 10% (v/v); PGY15% – probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt containing honey at 15% (v/v); WHC – water-holding capacity; a-d Mean ± standard deviations with different lowercase letters in the same row denote difference among the different formulations, based on the Tukey’s test (P < 0.05); A-E Mean ± standard deviations with different uppercase letters in the same column denote difference among the different storage periods, based on the Tukey's test (P < 0.05). L*, a* and b* are colour parameters.

The a* parameter values significantly differed among the assessed yoghurt formulations (P < 0.05), being higher with increased honey amounts and also as the storage period progressed (P < 0.05). This colour characteristic in yoghurt may be pronounced, with the colour characteristics of the honey, and with the oxidation of fatty acids and protolithic activity naturally occurring in yoghurt (Ghaderi-Ghahfarokhi et al., Reference Ghaderi-Ghahfarokhi, Shakarami and Zarei2024). The values of the b* parameter, also increased in probiotic goat yoghurt when the concentration of incorporated honey increased and also along the storage period. In contrast, yoghurt samples with added honey presented a difference in b* parameter values (P < 0.05) at the beginning of storage period but showed no significant difference (P > 0.05) at the end of the assessed storage period (8.61 ± 0.02, 8.73 ± 0.08 and 8.64 ± 0.06 in PGYH5, PGYH10 and PGYH15% respectively). Changes in goat-milk yoghurt colour on day-28 may have occurred because of the colour of added honey and the possible presence of Maillard reaction-derived compounds (Guenaoui et al., Reference Guenaoui, Ouchemoukh, Ouchemoukh, Ayad, Moumeni, Zeroual, Hadjal and Plazzotta2025). Similar colour characteristics were reported by Machado et al. (Reference Machado, de Oliveira, Campos, de Assis, de Souza, Madruga, Pacheco, Pintado and Queiroga2017) in goat yoghurt incorporated with stingless bee M. scutellaris honey.

Syneresis is a process of contraction in yoghurt gel accompanied by the spontaneous expulsion of whey, negatively impacting consumer perception of yoghurt quality. The values observed in probiotic goat yoghurt formulations are shown in Table 4. As cold storage progressed, the percentage of syneresis gradually increased in all yoghurt samples. All yoghurt with added honey (5, 10 and 15%) exhibited significant syneresis (P < 0.05) throughout the storage period. At the final storage time point, the yoghurt with 15% added honey showed lower (P < 0.05) syneresis compared to the other goat-milk yoghurt samples. This fact may be related to the high osmolarity of honey, which would attract water to the yoghurt-forming casein micelles, reducing the water release to the surroundings (Guenaoui et al., Reference Guenaoui, Ouchemoukh, Ouchemoukh, Ayad, Moumeni, Zeroual, Hadjal and Plazzotta2025). The presence of Apis mellifera intermissa bee honey seemed to influence the syneresis process in the assessed probiotic goat yoghurt samples.

Water holding capacity (WHC) is related to the ability of the proteins and dietary fibre to trap water in yoghurt gel structure and is thought of as the most important parameter for yoghurt quality. The results of WHC in goat-milk yoghurt formulations are presented in Table 3. At the end of storage, the WHC values were lower (P < 0.05) when compared to the first day of storage for all yoghurts, and the WHC was particularly lower (P < 0.05) in the control yoghurt (without added honey) (43.60 ± 0.29%; at day-28 of storage). This WHC behaviour was probably associated with the syneresis, as the increasing release of the liquid phase in yoghurt was concurrent with smaller WHC in the different yoghurt samples over time. Previously, an increase in acidity content during storage was observed in all assessed yoghurt formulations. This may be associated with the increase in water release (syneresis) in these samples because of possible protein denaturation as a consequence of pH decrease up to the isoelectric point of proteins, when this causes destabilization of casein micelles and consequent loss of liquid (Bezerra et al., Reference Bezerra, Souza and Correia2012).

In other studies, the presence of proteins, dietary fibres, and polysaccharides (Demirci et al., Reference Demirci, Aktaş, Sözeri, Öztürk and Akın2017; Hasani et al., Reference Hasani, Khodadadi and Heshmati2016) contributed to the improved WHC and reduced syneresis in yoghurt by binding water.

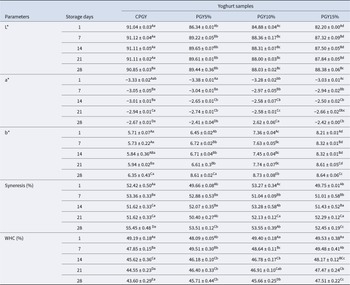

The results of apparent viscosity of goat-milk yoghurt samples are shown in Fig. 2. In this study, the control sample was the only formulation that presented a significant decrease (P < 0.05) in apparent viscosity during storage, which ranged from 30 ± 0.44 to 21 ± 0.87 Pa.s. All the samples with honey amounts showed a significant increase (P < 0.05) in apparent viscosity during all storage period (28 ± 0.25 Pa.s for PGYH15% sample on day 28). Honey is considered a high-viscosity fluid, and at refrigeration temperature, the honey incorporated in yoghurt behaved as a pseudo-plastic offering greater resistance and higher viscosity for yoghurt. Furthermore, the yoghurt apparent viscosity was directly proportional to the added honey amount. However, throughout the entire storage time the yoghurt samples containing honey revealed increased oscillation (Fig. 2) in viscosity values, which may also be associated with the characteristic of this ingredient. In line with our findings, the same apparent viscosity was noted in probiotic goat yoghurt added with stingless bee honey as pseudo-plastic fluid (Machado et al., Reference Machado, de Oliveira, Campos, de Assis, de Souza, Madruga, Pacheco, Pintado and Queiroga2017). On the other hand, during storage and up to the consumption of yoghurt, microgels are able to re-aggregate and the rheological properties of the product changes, presenting higher viscosity and elasticity (storage modulus measured by oscillatory rheology) (Gilbert and Turgeon, Reference Gilbert and Turgeon2021).

Figure 2. Apparent viscosity of probiotic goat stirred yoghurt containing honey during 28 days of refrigerated storage. CPGY – probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt (control); PGYH5% – probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt containing honey at 5% (v/v); PGYH10% – probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt containing honey at 10% (v/v); PGYH15% – probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt containing honey at 15% (v/v).

Microbiological analysis

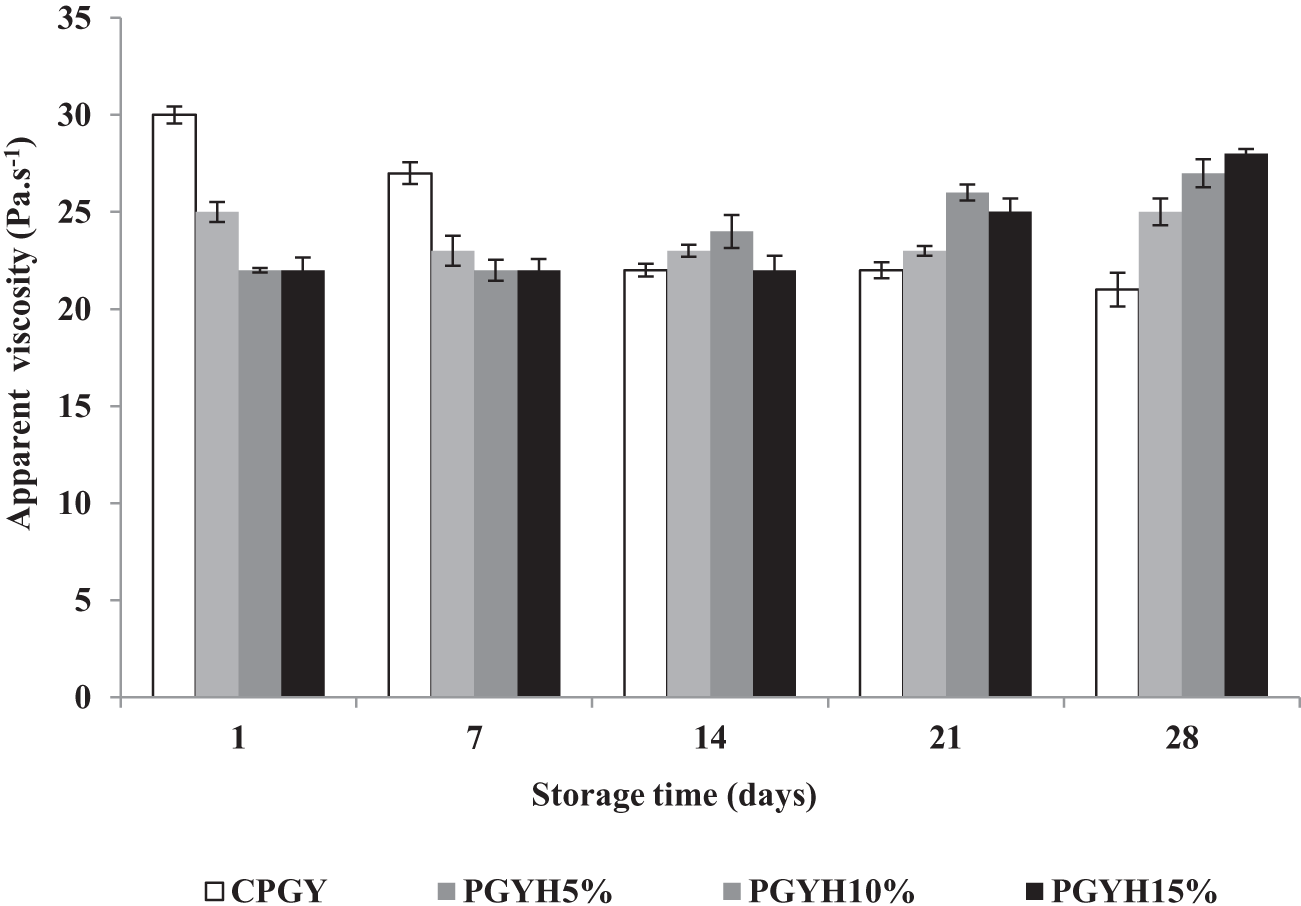

The results of microbiological analysis revealed the viable counts of the standard starter bacteria S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus and the probiotic culture L. plantarum C78 in goat yoghurt with honey and control during cold storage are presented in Fig. 3. The density of L. bulgaricus culture at the first day of storage was approximately 8.2 log CFU/mL, and decreased to approximately 7.5 and 7.4 log CFU/mL on day-14 and day-21 of refrigerated storage, respectively, in yoghurt formulations containing added bee honey. Statistically significant decrease was shown in all yoghurts in the following 14 days (P < 0.05). This behaviour of L. bulgaricus is consistent with the case reported by Demirci et al. (Reference Demirci, Sert, Aktaş, Atik, Negişe and Akına2019) and Machado et al. (Reference Machado, de Oliveira, Campos, de Assis, de Souza, Madruga, Pacheco, Pintado and Queiroga2017) who observed that the highest L. bulgaricus counts on day 14 followed by a decrease in counts at the end of the storage period in yoghurt with tomato powder and stingless bee honey, respectively containing probiotic bacteria.

Figure 3. Viable cell counts of Lactobacillus bulgaricus (A), Streptococcus thermophilus (B) and Lactobacillus plantarum C78 (C) of goat-milk stirred yoghurt containing honey during 28 days of refrigerated storage. CPGY – probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt (control); PGYH5% – probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt containing honey at 5% (v/v); PGYH10% – probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt containing honey at 10% (v/v); PGY15% – probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt containing honey at 15% (v/v).

On the first day after production, no significant difference in the viable counts of S. thermophilus in any yoghurt formulations was observed (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3B). The count of S. thermophilus slowly decreased towards to the end of storage. It is worth noting that the bee honey supplemented stirred yoghurt presented a higher count of S. thermophilus (ranging from 8.33 to 7.2 log CFU/mL) compared to CPGY (ranging from 8.3 to 6.7 log CFU/mL) on day 28 of storage. According to Medina et al. (Reference Medina, Aleman, Cedillos, Aryana, Olson, Marcia and Boeneke2023), the decline in S. thermophilus population in yoghurt with added honey was linked to pH reduction and the formation of diacetyl and acetaldehyde during fermentation. However, this same trend was not observed in other previous studies that reported an increase in S. thermophilus for one week of storage, followed by a subsequent decrease of about one log unit, which was observed in yoghurt produced from goat milk reported by Guler-Akin and Akin (Reference Guler-Akin and Akin2007). These differences could be attributed to the different conditions applied in the manufacturing process.

The bacterial counts found after the first day of storage in control goat-milk yoghurt or in yoghurt containing bee honey were higher than the minimum counts recommended to characterize a fermented milk as yoghurt (Machado et al., Reference Machado, de Oliveira, Campos, de Assis, de Souza, Madruga, Pacheco, Pintado and Queiroga2017).

For the L. plantarum C78, probiotic culture, a similar survival trend was found in all assessed goat-milk yoghurt samples on the first day of storage, although these counts were always higher (P < 0.05) in yoghurt containing added honey from day-14 of storage (8.2 and 8.5 in control and PGYH15%, respectively) (Fig. 3C). A similar behaviour of sharp reduction in counts of L. plantarum C78 occurred from 7 to 14 days of storage in all yoghurt formulations (approximately 8.2 to 8.5 log CFU/mL in control and PGYH15%, respectively), to have a final decrease in counts towards the end of storage. For standard starter groups and L. plantarum C78, the addition of bee honey in yoghurt appeared to assure the maintenance of higher counts in comparison to the control. These differences were more pronounced from day-21 of cold storage (P < 0.05), when an inversion of sugar content occurred in the yoghurt (mostly in PGYH15%). Our finding revealed that the level of added honey positively improved the viability of the yoghurt starter culture and probiotic bacteria. Our findings were aligned with those of Alvardo et al. (Reference Alvarado, Ibarra-Sanchez, Mysonhimer, Khan, Cao, Miller and Holscher2024) who reported a higher B. animalis survivability in yoghurt with clover honey. All together, these findings suggest that for L. plantarum C78, some compounds were released in the goat yoghurt with honey, probably fermentable sugars, that may promote its growth, but this was not enough to maintain their cell number until storage (Machado et al., Reference Machado, de Oliveira, Campos, de Assis, de Souza, Madruga, Pacheco, Pintado and Queiroga2017). Overall, the counts of L. plantarum C78 were above 7 log CFU/mL during the evaluated storage period in all yoghurt samples, remaining consistent with the minimum count required to confer probiotic physiological benefits in functional food products (Bedani et al., Reference Bedani, Rossi and Saad2013).

Sensory analysis

In addition to the potential health benefits of functional yoghurt, their consumption is primarily driven by sensory preferences and overall marketability. Consequently, conducting sensory evaluations of products is crucial (Yu et al., Reference Yu, Ma, Wang, Lu, Fu, Zhang, Shi, Xu and Xie2022). Thus, the impact of the incorporation of bee honey as an alternative sweetener on sensory aspects of goat yoghurt containing L. plantarum C78 was evaluated to obtain natural food products with pleasant sensory characteristics.

The mean scores obtained for goat yoghurt in sensory evaluation are shown in Fig. 4(A, B and C). Panellists declare notable differences among yoghurt formulations only in terms of flavour and overall acceptability attributes (P < 0.05) in goat yoghurt containing the greatest added honey amounts, (PGYH10% and PGYH15%), received the highest scores (7.02, 7.33, 6.46 and 6.84) on the first and 14th days of storage, respectively. Similarly, a previous study found that the addition of mulberry fruit enhanced the acceptance of goat yoghurt, improving its flavour and suggesting a positive influence of sugars naturally found in fruit on these sensory attributes (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Zhou, Zhang, Du, Tu, Wu, Zeng, Dang, Liu, Pan and Liu2025). Likewise, the added bee honey may have made the goat yoghurt containing L. plantarum C78 more acceptable and attractive due to the presence of these saccharides in the formulation, in addition to the presence of other possible pleasant flavour-forming compounds (Machado et al., Reference Machado, de Oliveira, Campos, de Assis, de Souza, Madruga, Pacheco, Pintado and Queiroga2017). Interestingly, the highest acidity observed in goat yoghurt containing added honey did not impact negatively on the sensory acceptance of probiotic yoghurt. This could be related to the honey sweetness that in combination with the higher acidity may provide a desirable flavour to probiotic goat yoghurt. In another study, Serhan et al. (Reference Serhan, Mattar and Debs2016) revealed that concentrated yoghurt (Labneh) made of a mixture of goats’ and cows’ milk presented a less pronounced caprine taste, which contributes to better acceptance by consumers, nevertheless maintaining desirable nutritional aspects of goat's milk.

Figure 4. Sensorial profiles of probiotic goat stirred yoghurt containing honey after first day (A), 14 days (B) and 28 days (C) of storage. CPGY – probiotic stirred goat yoghurt (control); PGYH5% – probiotic goat stirred yoghurt containing honey at 5% (v/v); PGYH10% – probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt containing honey at 10% (v/v); PGYH15% – probiotic goat-milk stirred yoghurt containing honey at 15% (v/v).

Conclusion

The incorporation of honey produced by Apis mellifera intermissa into goat-milk yoghurt containing the probiotic L. plantarum C78 positively affected the assessed characteristics of the product during refrigerated storage such as increasing water holding capacity, and imparting desired stability to the yoghurt gel throughout storage The count of L. plantarum C78 in all functional goat yoghurt formulations remained sufficient (>7 log CFU/mL) to promote health benefits to the consumer throughout storage. The formulation containing bee 15% honey presented the highest counts of L. plantarum C78 at 14 and 21 days of storage, indicating a growth promoting effect. The addition of honey appeared to directly influence the acidity of the probiotic goat-milk yoghurt over time. The yoghurts containing honey presented the best sensory acceptance. Finally, the results of this study presented a successful incorporation of the probiotic and honey produced by a native Tunisian bee as ingredients of a new goat dairy product with satisfactory nutritional and sensory quality. Further research is required to explore the biofunctionality of honey and the viability of probiotics during the simulated gastrointestinal passage of functional yoghurts. This would provide valuable insights into the potential health benefits of consuming these products and satisfy consumer interest in functional food.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Tunisian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research for its financial support of the Research Laboratory: Technological Innovation and Food Security (LR22 AGR01-ESIAT) from Carthage University.