Management Implications

Invasive winter annual grasses (IWAGs) are considered some of the most problematic invasive species on rangeland and wildlands in the western United States. Currently, herbicides are the viable tool to address the threat of these IWAGs on millions of hectares. Past herbicides have been inconsistent in providing the multiyear IWAG control needed to restore a site or have caused injury to desirable species. Furthermore, revegetation in sites void of desirable species often fails, due to reinvasion by IWAGs; therefore, long-term IWAG control options are needed to allow enough time to reestablish desirable species on these sites. Indaziflam has been shown to provide 3 or more years of IWAG control, but there is limited information on revegetation after indaziflam applications. Field studies established on the Colorado Front Range showed one application of indaziflam (72 and 102 g ai ha −1 ) was still reducing Bromus tectorum (downy brome), Bromus arvensis (Japanese brome), and Secale cereale (feral rye) biomass more than 5-fold compared with the nontreated check at 3 yr after treatment (YAT). Past studies indicate that the seedbanks of these IWAGs are less than 5 yr (Sebastian et al. Reference Sebastian, Nissen, Sebastian and Beck2017b; Stump and Westra Reference Stump and Westra2000); therefore, a 3-yr reduction in biomass could assist in depleting the seedbank and allow enough time for the successful establishment of drill-seeded species. A mix of cool-season grasses, warm-season grasses, forbs, and shrubs drill seeded 9 mo after herbicide application had significantly greater establishment in indaziflam-treated plots compared with other herbicide treatments at 3 YAT. At one site, species only established within indaziflam-treated plots. At a field site with a remnant native plant community, only indaziflam treatments significantly increased native grass biomass and native species richness. For land managers, indaziflam is a potential tool that can provide the long-term IWAG control needed to successfully reestablish desirable species, either through drill seeding or from the response of the native plant community. Drill seeding after indaziflam application appears to be a viable option for restoration on sites invaded by IWAGs, although further research is still needed to determine appropriate species selection and plant-back intervals for drill seeding.

Introduction

Invasive winter annual grasses (IWAGs), especially downy brome (Bromus tectorum L.), are a significant threat to rangeland ecosystems in the western United States (Knapp Reference Knapp1996; Mack Reference Mack1981; Monaco et al. Reference Monaco, Mangold, Mealor, Mealor and Brown2017). Winter annual grasses are able to dominate native perennial systems in arid and semiarid western climates due to their opportunistic life cycle, prolific seed production, and ability to deplete early-season soil moisture (Mack and Pyke Reference Mack and Pyke1983). Unchecked infestations can severely impact ecosystem services by decreasing desirable habitat, native plant diversity, and forage production, while increasing fire frequency due to the accumulation of fine fuels (Abatzoglou and Kolden Reference Abatzoglou and Kolden2011; DiTomaso et al. Reference DiTomaso, Masters and Peterson2010; Monaco et al. Reference Monaco, Mangold, Mealor, Mealor and Brown2017; Weltz et al. Reference Weltz, Coates-Markle and Narayanan2011).

In the past few decades, increased expansion of newer and less-widespread annual grass invaders has become a greater concern for land managers (Davies and Johnson Reference Davies and Johnson2011; Duncan et al. Reference Duncan, Jachetta, Brown, Carrithers, Clark, DiTomaso, Lym, McDaniel, Renz and Rice2004). Feral rye (Secale cereale L.), an IWAG that derived from the cultivated cereal rye, is an aggressive weed in cereal crops (Burger et al. Reference Burger, Lee and Ellstrand2006). More recently, S. cereale has started to spread into and become very problematic on non-crop sites (Ellstrand et al. Reference Ellstrand, Heredia, Leak-Garcia, Heraty, Burger, Yao, Nohzadeh-Malakshah and Ridley2010; Roerig and Ransom Reference Roerig and Ransom2017). The study by Roerig and Ransom (Reference Roerig and Ransom2017) showed landscape-scale expansion rates of S. cereale as high as 50% in 1 yr on natural area sites in Utah.

Remnant native plant communities still persist in much of the rangeland and natural areas invaded by IWAGs (Belnap et al. Reference Belnap, Ludwig, Wilcox, Betancourt, Dean, Hoffmann and Milton2012; DiTomaso Reference DiTomaso2000; Hobbs et al. Reference Hobbs, Arico, Aronson, Baron, Bridgewater, Cramer, Epstein, Ewel, Klink, Lugo, Norton, Ojima, Richardson, Sanderson and Valladares2006). Sites with a robust native plant component are easier to restore than highly degraded sites lacking native species, because timely weed control can allow for native species recovery and resistance from future invasion (Chambers et al. Reference Chambers, Bradley, Brown, D’Antonio, Germino, Grace, Hardegree, Miller and Pyke2014; DiTomaso Reference DiTomaso2000; Sebastian et al. Reference Sebastian, Fleming, Patterson, Sebastian and Nissen2017a). Several studies have shown that native plant communities respond positively to IWAG control, including increases in perennial grass and forb biomass as well as species richness (DiTomaso et al. Reference DiTomaso, Masters and Peterson2010; Sebastian et al. Reference Sebastian, Sebastian, Nissen and Beck2016b, Reference Sebastian, Fleming, Patterson, Sebastian and Nissen2017a). On invaded sites where the native plant community is highly degraded or nonexistent, more-intensive management is required (Evans and Young Reference Evans and Young1977; Fowers Reference Fowers2015). For example, the native perennial seedbank has been severely diminished in large areas of the shrub–steppe communities of the Great Basin, which have been plagued by dense infestations of IWAGs and frequent fire cycles (Chambers et al. Reference Chambers, Roundy, Blank, Meyer and Whittaker2007; Humphrey and Schupp Reference Humphrey and Schupp2001). In areas such as the Great Basin, weed management along with revegetation is required in order to reestablish native species and prevent reinvasion (Davies and Boyd Reference Davies and Boyd2018; Mangold and Parkinson Reference Mangold and Parkinson2015; Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Orloff, Lancaster, Kirby and Carlson2010). Revegetation is not only very costly and labor-intensive, but often fails in western climates where moisture events are scarce and unpredictable (Ethridge et al. Reference Ethridge, Sherwood, Sosebee and Herbel1997; Mangold and Parkinson Reference Mangold and Parkinson2015; Young Reference Young2000). Herbicides used in the restoration process can also negatively impact desirable seeded species, preventing successful establishment (Lym et al. Reference Lym, Becker, Moechnig, Halstvedt and Peterson2017; McManamen et al. Reference McManamen, Nelson and Wagner2018; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Monaco and Rigby2009; Sbatella et al. Reference Sbatella, Wilson, Enloe and Hicks2011; Shinn and Thill Reference Shinn and Thill2004).

Herbicides currently used for IWAG control and site restoration provide adequate short-term weed control; however, most herbicide options do not provide the long-term control needed for native species establishment (Kelley et al. Reference Kelley, Fernandez-Gimenez and Brown2013; Kyser et al. Reference Kyser, Wilson, Zhang and DiTomaso2013; Mangold et al. Reference Mangold, Parkinson, Duncan, Rice, Davis and Menalled2013; Shinn and Thill Reference Shinn and Thill2004; Whitson and Koch Reference Whitson and Koch1998). Furthermore, very few herbicides for use on rangeland or in natural areas provide S. cereale control. Glyphosate can be used during native species dormancy to provide POST control of overwintering winter annual grass seedlings or for broad-spectrum weed control before revegetation on sites without desirable species (Kyser et al. Reference Kyser, Creech, Zhang and DiTomaso2012, Reference Kyser, Wilson, Zhang and DiTomaso2013; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Morris and Surface2016). Although the use of glyphosate can be effective for short-term control, glyphosate has no soil residual and does not provide protection against reestablishment of invasive grasses (Sebastian et al. Reference Sebastian, Nissen, Sebastian and Beck2017b). Winter annuals are very opportunistic, with the ability to germinate whenever the growing conditions are favorable (Thill et al. Reference Thill, Beck and Callihan1984). Therefore, providing soil residual control is critical to depleting the annual grass seedbank and protecting seeded species during establishment, ultimately resulting in long-term restoration success (Sebastian et al. Reference Sebastian, Nissen, Sebastian and Beck2017b).

Indaziflam, a new herbicide option for weed management on natural areas and rangeland, provides long-term B. tectorum and S. cereale control (Sebastian et al. Reference Sebastian, Sebastian, Nissen and Beck2016b, Reference Sebastian, Fleming, Patterson, Sebastian and Nissen2017a). As a cellulose biosynthesis inhibitor, indaziflam inhibits root growth in newly germinated seedlings by preventing cellulose formation (Brabham et al. Reference Brabham, Lei, Gu, Stork, Barrett and DeBolt2014; Tateno et al. Reference Tateno, Brabham and DeBolt2016). Indaziflam is a long-residual, PRE herbicide that is effective in controlling both grass and broadleaf seedlings, although it is more active on grasses (Brabham et al. Reference Brabham, Lei, Gu, Stork, Barrett and DeBolt2014; Sebastian et al. Reference Sebastian, Nissen and Rodrigues2016a, Reference Sebastian, Fleming, Patterson, Sebastian and Nissen2017a). Low application rates (44 to 102 g ai ha−1) and perennial species tolerance makes indaziflam a preferred herbicide for rangeland restoration (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Sebastian, Nissen and Sebastian2019; Sebastian et al. Reference Sebastian, Nissen and Rodrigues2016a, Reference Sebastian, Sebastian, Nissen and Beck2016b, Reference Sebastian, Fleming, Patterson, Sebastian and Nissen2017a). Additionally, indaziflam can be combined with glyphosate when desirable perennials are dormant to achieve POST control of winter annual grass seedlings plus PRE control to prevent reinvasion from the soil seedbank. Several studies have been conducted evaluating IWAG control and native species tolerance with indaziflam applications (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Sebastian, Nissen and Sebastian2019; Koby et al Reference Koby, Prather, Quicke, Beuschlein and Burke2019; Sebastian et al. Reference Sebastian, Nissen and Rodrigues2016a, Reference Sebastian, Sebastian, Nissen and Beck2016b, Reference Sebastian, Fleming, Patterson, Sebastian and Nissen2017a), but currently there is no published research using indaziflam in combination with seeding of native species. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate long-term B. tectorum and S. cereale control with indaziflam applications and subsequent establishment of drill-seeded grasses, forbs, and shrubs.

Materials and Methods

Site Description

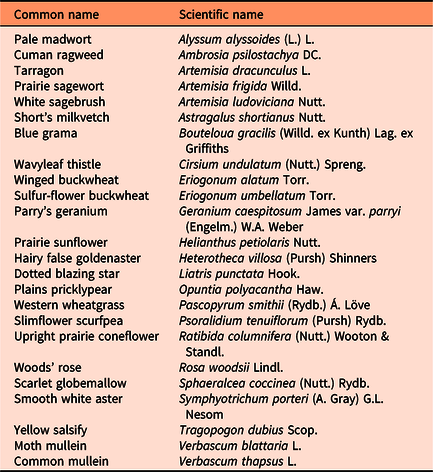

The experiment was established in 2014 at two sites in Larimer County, CO, located on the Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s Wellington State Wildlife Area (Site 1: 40.71°N, 104.95°W; Site 2: 40.73°N, 104.95°W). Site 1 was infested by a B. tectorum monoculture (100% canopy cover), and Site 2 was infested by a S. cereale monoculture (100% canopy cover). Both Sites 1 and 2 were considered severely degraded with no desirable species present. In 2015 Site 3 was established in Boulder County, CO, on Boulder County Parks and Open Space’s Ron Stewart Preserve at Rabbit Mountain (40.25°N, 105.22°W). Site 3 consisted of a dense (~80% canopy cover) B. tectorum and Japanese brome (Bromus arvensis L.) infestation with a remnant native species population (Table 1). Sites 1 and 2 were approximately 1.5 km apart and 56 km from Site 3.

Table 1. List of co-occurring species at Site 3 within the experimental plots. a

a Not all species occurred in every plot.

The soil at Site 1 was Satanta loam (fine-loamy, mixed, superactive, mesic Aridic Argiustolls), with 3.3% organic matter and 7.6 pH in the top 20 cm. The site was level, with an average elevation of 1,607 m (5,271 ft). The soil at Site 2 was Nunn clay loam (fine, smectitic, mesic Aridic Argiustolls), with 1.6% organic matter and 7.5 pH in the top 20 cm. This site was also level, with an average elevation of 1,609 m (5,278 ft). The soil at Site 3 was Baller stony sandy loam (loamy-skeletal, mixed, superactive, mesic Lithic Haplustolls), with 1.5% organic matter and 6.6 pH in the top 20 cm. The site had an approximate 9° slope, with an average elevation of 1,737 m (5,699 ft) (USDA-NRCS 2014).

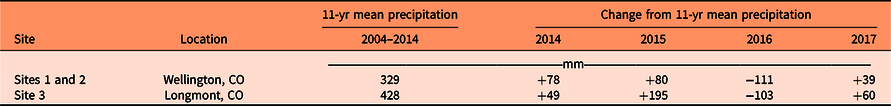

Total annual precipitation from the nearest weather stations was obtained from the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow Network (2020) for the years of the study and compared with the 11-yr means. Years 2014 and 2015 had above average precipitation, while a drought occurred at all three sites in 2016. Precipitation conditions were again above average for 2017 (Table 2).

Table 2. Yearly precipitation during the field experiment based on data obtained from closest weather stations to sites (1.9 km from Site 1; 1.4 km from Site 2; 4 km from Site 3), compared with 11-yr mean. a

a Data derived from Community Collaborative Rain, Snow and Hail Network (2020).

Experimental Design

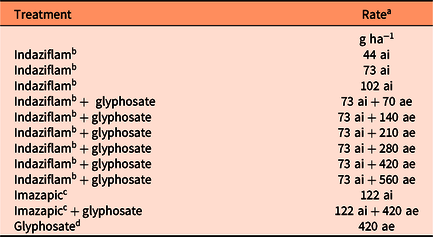

Twelve herbicide treatments and one nontreated control were evaluated for IWAG control (Table 3). Herbicide treatments were applied to 3 by 9 m plots arranged in a randomized complete block design with four replications. All treatments were applied with a CO2-pressurized backpack sprayer (R&D Sprayers, Opelousas, LA) using 11002LP flat-fan nozzles at 187 L ha−1 at 207 kPa. Herbicide applications were made on March 22, 2014, at Sites 1 and 2 and April 7, 2015, at Site 3. All winter annual grasses were actively growing when the herbicide applications were made. Bromus tectorum was 8- to 10-cm tall with 3 to 5 tillers at Site 1, and S. cereale was 13- to 18-cm tall with 1 to 4 tillers at Site 2. Both B. tectorum and B. arvensis were actively growing and were 4- to 8-cm tall with 1 to 5 tillers when herbicide applications were made at Site 3.

Table 3. Herbicides and rates applied in evaluating Bromus tectorum, Secale cereale, and Bromus arvensis control.

a All treatments included 0.25% v/v nonionic surfactant.

b Treatments received a sequential application of indaziflam (102 g ai ha−1) + glyphosate (420 g ae ha−1) on half of each experimental plot 2 yr after original application (February 2016) at Sites 1 and 2.

c Treatments received a sequential application of imazapic (122 g ai/ae ha−1) + glyphosate (420 g ha−1) on half of each experimental plot 2 yr after original application (February 2016) at Sites 1 and 2.

d Treatment received a sequential application of glyphosate (420 g ae ha−1) on half of each experimental plot 2 yr after original application (February 2016) at Sites 1 and 2.

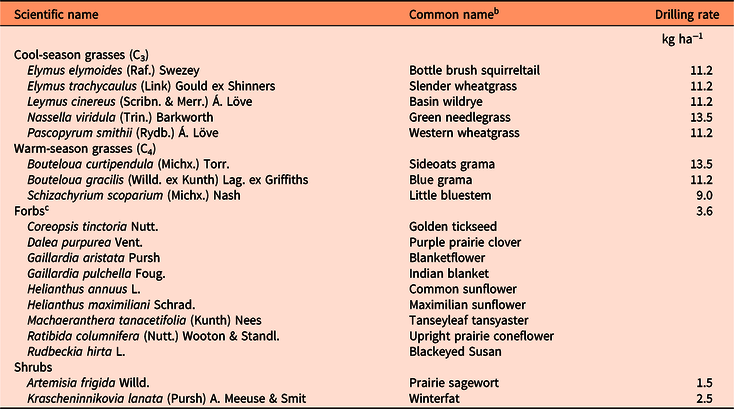

In December 2014, Sites 1 and 2 were drill seeded using a no-till rangeland grass drill (Flex II, Truax, Minneapolis, MN) with a variety of native cool- and warm-season grasses, forbs, and shrubs at National Resources Conservation Service recommended seeding rates (Table 4). Grasses, forbs, and shrubs were seeded in two individual rows per species perpendicular to herbicide treatments. A native prairie forb mix that included 19 forb species was used, although only 9 species established and were included in the analyses. On February 22, 2016, at Sites 1 and 2, herbicide applications were reapplied to half of each plot, creating a split-plot design to evaluate differences in long-term control and plant establishment with one versus two herbicide applications. All treatments that initially contained indaziflam received a reapplication of indaziflam (102 g ai ha−1) plus glyphosate (420 g ae ha−1), while the other treatments received a reapplication of the original treatment. At the second herbicide application timing, B. tectorum was actively growing and was 3- to 8-cm tall with 1 to 2 tillers, while S. cereale was 5- to 10-cm with 1 to 3 tillers. All treatments were applied with the same equipment used for the first application.

Table 4. List of perennial grass, forb, and shrub species drill seeded at Sites 1 and 2 following preplant herbicide application in March 2014. a

a Species were seeded in December 2014 at both locations.

b Common names based on U.S. Department of Agriculture PLANTS Database: https://plants.usda.gov.

c A native prairie forb mix was used that included 19 forb species. Only the species that established and were part of the frequency counts for data analysis are included in the table.

Treatment Evaluations

Bromus tectorum and S. cereale biomass was harvested from 2014 to 2017 at Sites 1 and 2 using randomly placed 1-m2 quadrats in each plot; quadrats were not placed in the same location in subsequent years. In 2016 and 2017, after the second herbicide application was made to half of each plot, two biomass collections were made, one subsample from the side that received one herbicide application and one subsample from the side that received a second herbicide application. Drilled species establishment at Sites 1 and 2 was determined by taking frequency counts using a meter stick separated into ten 10-cm segments. Frequency was taken for each drilled species individually. An occurrence of a species in a 10-cm segment counted as one; therefore, counts ranged from 0 to 10. Counts were then directly converted into percent frequency by multiplying by 10. Three frequency counts were taken for each plot to determine an average percent frequency over the entire 3-m-wide plot and two drilled rows. In 2016 and 2017, frequency counts were conducted the same way, although two frequency measurements were collected in each subplot (one or two herbicide applications) to adhere with the split-plot design.

Due to the remnant native plant community, Site 3 was not drill seeded, and the response of the existing native vegetation was evaluated. Biomass of B. tectorum, B. arvensis, perennial grasses, and forbs was harvested from 2015 to 2018 using the same quadrat collection method used in Sites 1 and 2. A second herbicide application was not made at this site, so only one biomass sample per plot was collected during those years. The two Bromus species present at Site 3 (B. tectorum and B. arvensis) were not separated, so total biomass of both species together was recorded. Species richness was determined at Site 3 by counting the number of species occurring in each plot.

Data Analysis

Nonlinear regression using the drc package in R v. 3.4.3 was used to determine glyphosate rates required to reduce plant dry biomass by 50% (GR50) for B. tectorum and S. cereale (R Core Team 2017) at Sites 1 and 2. These sites were determined to have comparable starting weed densities based on IWAG biomass and cover being very similar. The treatments that included indaziflam (73 g ai ha−1) plus the increasing rate of glyphosate were used for the analysis. Because treatments were applied POST in the spring, biomass reductions in the first season after application were due to glyphosate, as indaziflam only provides PRE control of IWAGs (Brabham et al. Reference Brabham, Lei, Gu, Stork, Barrett and DeBolt2014). The herbicide concentrations resulting in 50% reduction in plant biomass (GR50) were determined for S. cereale and B. tectorum using four-parameter log-logistic regression. The equation used to regress herbicide concentration with percent reduction in plant dry biomass was:

where c is the lower response limit, d is the upper response limit, b is the slope of the curve, and GR50 is the herbicide dose resulting in 50% reduction in response (biomass). For curve fitting and GR50 estimation, the lower limit of the model was constrained to 0. An F-test of the curves for both species was conducted to determine whether the difference between the GR50 values was statistically significant at the 5% level of probability.

To test the effect of herbicide treatment on IWAG biomass, a linear mixed-effects model was created using the lme4 package in R v. 3.4.3, testing for treatment effects at α = 0.05 (R Core Team 2017). Site and year were not included in the model and were analyzed separately due to a large variability in biomass across years from environmental factors as well as to increase data normality. For Sites 1 and 2 (the first 2 yr) and Site 3 (all years), the fixed factor included in the model was treatment, while block was included as a random factor. For Sites 1 and 2, the split-plot design was then considered in years 3 and 4 in the linear mixed-effects model, with the fixed factors being treatment, number of herbicide applications, and their interaction, while block was included as a random factor. At all three sites, several treatments were highly effective, resulting in a mean of zero Bromus spp. or S. cereale biomass, which created problems with data normality; therefore, all treatments with a mean of zero were excluded from the model. Confidence intervals were then estimated for all non-zero treatment means. Further analyses of treatment effect were performed using the emmeans package in R (R Core Team 2017) to obtain comparisons between all pairs of least-squares means for each year with a Tukey adjustment (P < 0.05). Treatments with a mean of zero were then grouped with treatments where the confidence interval included zero in order to have a full set of treatment comparisons. Any treatment with a confidence interval not containing zero was considered significantly different from the treatments where the mean was zero.

Drilled species were grouped into cool-season grasses (C3), warm-season grasses (C4), and forbs/shrubs for analysis. Site and year were again analyzed separately. Drilled species frequencies were square root (n + 0.5) transformed when needed to meet assumptions of normality. Frequency data were subjected to the same linear mixed-effects model and post hoc analysis used to evaluate winter annual grass biomass data. Again, treatments with an average frequency of 0 were dropped from the model and included with treatments whose confidence interval included zero for post hoc analysis.

At Site 3, to analyze treatment effects on grass and forb biomass a linear mixed-effects model was created with treatment, year, and their interaction as fixed factors. Block was included as the random factor. We failed to reject the hypothesis that count data of species richness were from a Poisson distribution (P = 0.9523); therefore, species richness was analyzed using a generalized linear mixed model with a Poisson distribution using the same factors as the grass and forb data. Any significant treatment, year, or interaction effects were determined post hoc using pairwise comparison of least-squares means test with Fisher’s protected LSD (P < 0.05) (lme4 and emmeans packages; R Core Team 2017).

Results and Discussion

Glyphosate Dose Response

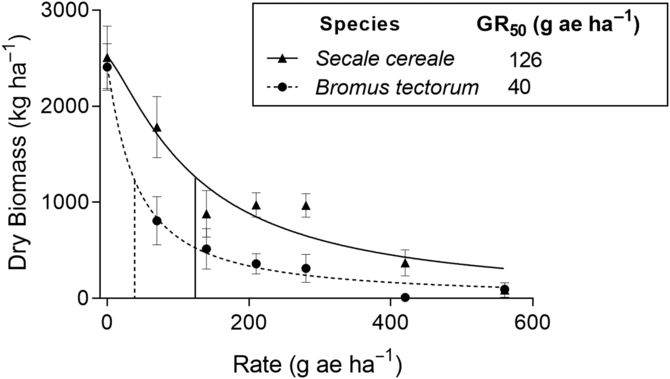

Bromus tectorum (Site 1) was controlled at a much lower glyphosate rate than S. cereale (Site 2) (Figure 1; Supplementary Figure S1). The GR50 value was approximately three times greater for S. cereale (GR50 = 126.0 g ae ha−1) compared with B. tectorum (GR50 = 40.4 g ae ha−1). A comparison between the two GR50 values was highly significant (P < 0.001); however, a GR50 value could not be calculated for Site 3 (B. tectorum and B. arvensis with native species understory), because the lowest glyphosate rate reduced the biomass more than 50% (data not shown).

Figure 1. Response of feral rye (Secale cereale) and downy brome (Bromus tectorum) to glyphosate. Dose–response curves were fit using three-parameter log-logistic regression. Mean values of four replications are plotted. Vertical lines represent the herbicide dose resulting in 50% reduction in dry biomass (GR50) for each species.

Invasive Winter Annual Grass Response in Highly Degraded Sites

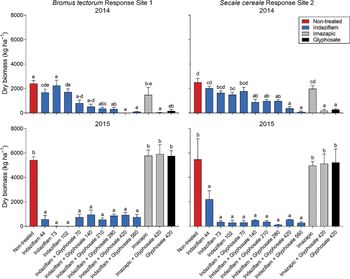

Year to year IWAG biomass was inconsistent due to variable precipitation; therefore, year and site were analyzed separately. Treatment was highly significant (P < 0.001) for Sites 1 and 2. During the initial season after application (2014), only the treatments that included glyphosate reduced both B. tectorum and S. cereale biomass, as the herbicide applications were made POST while both annual grasses were actively growing (Figure 2). By 1 yr after treatment (YAT) (2015), only treatments containing indaziflam reduced B. tectorum and S. cereale biomass, even when glyphosate was not included in the initial application. All other treatments were no longer impacting B. tectorum and S. cereale biomass (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Invasive winter annual grass biomass response to herbicide treatments at Site 1 (Bromus tectorum) and Site 2 (Secale cereale) in year of treatment (2014) and 1 yr after treatment (YAT) (2015). Application timing was after B. tectorum and S. cereale emergence (POST) in March 2014. Letters indicate differences among herbicide treatments separated by year and by site, using least-squares means (P < 0.05). Herbicide treatments are as follows: indaziflam (44, 73, 102 g ai ha−1), indaziflam (73 g ai ha−1) plus glyphosate (70, 140, 210, 280, 420, 560 g ae ha−1), imazapic (22 g ai ha−1), imazapic (122 g ai ha−1) plus glyphosate (420 g ae ha−1), and glyphosate (420 g ae ha−1).

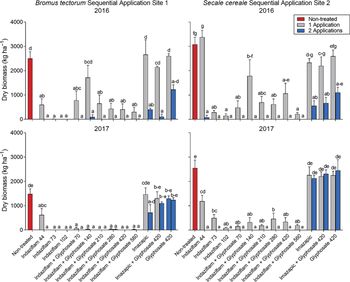

In the season directly following the second herbicide application and 2 yr after initial application (2016), the treatment by application number interaction was highly significant at Sites 1 and 2 (P < 0.001). For most indaziflam treatments, there was not a significant difference in B. tectorum and S. cereale biomass reductions between one and two applications (Figure 3). For treatments that did not contain indaziflam, one herbicide application was not sufficient to control IWAGs 2 yr later (Figure 3). At both Sites 1 and 2, the second imazapic application with glyphosate did provide better IWAG biomass reduction compared with one application, while a second application of glyphosate alone was not sufficient to control B. tectorum or S. cereale (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Invasive winter annual grass biomass response to 1 or 2 herbicide applications at Site 1 (Bromus tectorum) and Site 2 (Secale cereale) 2 yr after treatment (YAT) (2016) and 3 YAT (2017). Initial application was POST in March 2014; second application was POST in February 2016. Letters indicate differences among herbicide treatments across application number separated by year and by site, using least-squares means (P < 0.05). Herbicide treatments are as follows: indaziflam (44, 73, 102 g ai ha−1) and indaziflam (73 g ai ha−1) plus glyphosate (70, 140, 210, 280, 420, 560 g ae ha−1), with these treatments receiving a sequential application of indaziflam (102 g ai ha−1) + glyphosate (420 g ae ha−1) on half of each experimental plot 2 yr after original application; imazapic (122 g ai ha−1) and imazapic (122 g ai ha−1) plus glyphosate (420 g ae ha−1), with these treatments receiving a sequential application of imazapic (122 g ai ae ha−1) + glyphosate (420 g ha−1) on half of each experimental plot 2 yr after original application; and glyphosate (420 g ae ha−1), with this treatment receiving a sequential application of glyphosate (420 g ae ha−1) on half of each experimental plot 2 yr after original application.

At 1 yr after herbicide reapplication and 3 yr after initial application (2017), the treatment by application number interaction was still highly significant at both sites (P < 0.001). In the B. tectorum site (Site 1), there were no differences in B. tectorum biomass between one and two applications for treatments containing indaziflam (Figure 3). Both one and two applications continued to reduce B. tectorum biomass compared with the nontreated check. There was no longer a difference in B. tectorum biomass between one and two imazapic applications, and all treatments without indaziflam had B. tectorum biomass comparable to the nontreated check (Figure 3). It should be noted that overall there was much less B. tectorum biomass at Site 1 in 2017 compared with previous years. In the S. cereale site (Site 2), the lowest indaziflam rates applied without glyphosate (44 and 73 g ai ha−1) and the indaziflam (73 g ai ha−1) plus glyphosate (280 g ae ha−1) treatments had differences in biomass with one compared with two herbicide applications, although all treatments including indaziflam (one or two applications) were still providing reductions in S. cereale biomass compared with the nontreated check (Figure 3). Treatments that did not include indaziflam were no longer providing any reductions in S. cereale biomass with one or two applications (Figure 3).

Native Species Establishment in Highly Degraded Sites

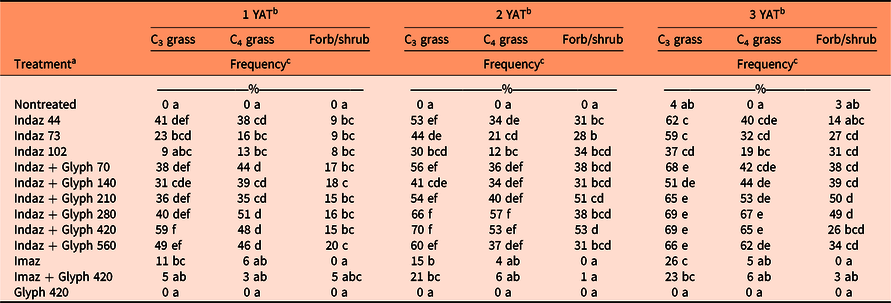

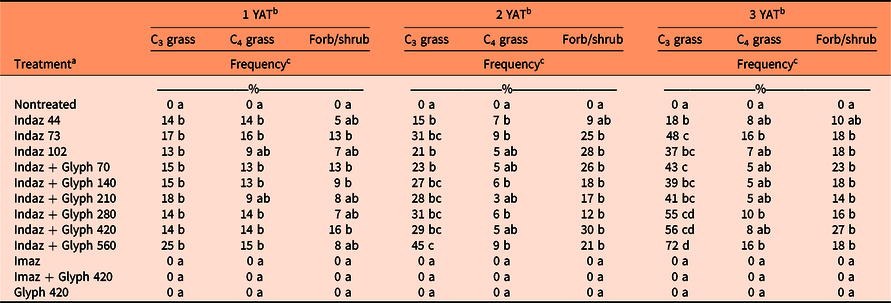

Species frequency was assessed by functional group: C3 grasses, C4 grasses, and forbs/shrubs. In the year following drill seeding (2015), treatment was highly significant for all functional groups in both sites (P < 0.001). In the B. tectorum site (Site 1), there was significant C3 grass establishment in all indaziflam treatments, except for indaziflam at 102 g ai ha−1, and the imazapic-alone treatment compared with the nontreated check, although the indaziflam treatments had an average C3 grass frequency of 36 ± 4.8% (mean ± SE) compared with imazapic with an average frequency of 11 ± 4.1% (Table 5). Only treatments that included indaziflam had significant C4 grass and forb/shrub establishment (Table 5). Overall establishment was lower at the S. cereale site (Site 2), although drilled species in all functional groups only established in treatments that included indaziflam (Table 6).

Table 5. Percent frequency of cool-season grasses (C3), warm-season grasses (C4), and forbs/shrubs 1, 2, and 3 yr after initial herbicide treatment (YAT) at Site 1.

a Herbicide treatments are as follows: indaziflam (Indaz, 44, 73, 102 g ai ha−1), indaziflam (Indaz, 73 g ai ha−1) plus glyphosate (Glyph, 70, 140, 210, 280, 420, 560 g ae ha−1), imazapic (Imaz), imazapic (Imaz) plus glyphosate (Glyph, 420 g ae ha−1), and glyphosate (Glyph, 420 g ae ha−1).

b Means followed by the same letter within the column do not differ significantly at the P < 0.05 level.

c Frequency was determined by the occurrence of a species in a 10-cm segment counted as one; therefore, counts ranged from 0 to 10. Counts were then directly converted into percent frequency by multiplying by 10.

Table 6. Percent frequency of cool-season grasses (C3), warm-season grasses (C4), and forbs/shrubs 1, 2, and 3 yr after initial herbicide treatment (YAT) at Site 2.

a Herbicide treatments are as follows: indaziflam (Indaz, 44, 73, 102 g ai ha−1), indaziflam (Indaz, 73 g ai ha−1) plus glyphosate (Glyph, 70, 140, 210, 280, 420, 560 g ae ha−1), imazapic (Imaz), imazapic (Imaz) plus glyphosate (Glyph, 420 g ae ha−1), and glyphosate (Glyph, 420 g ae ha−1).

b Means followed by the same letter within a column do not differ significantly at the P < 0.05 level.

c Frequency was determined by the occurrence of a species in a 10-cm segment counted as one; therefore, counts ranged from 0 to 10. Counts were then directly converted into percent frequency by multiplying by 10.

After the second herbicide application was made in half of each plot, the treatment by application number interaction for drilled species establishment was analyzed for significance. Application number and the treatment by application number interaction were not significant for all functional groups of drilled species at both sites over the 2 yr. Treatment was highly significant (P < 0.001) for establishment in all functional groups at both sites during both years, so establishment for each group was averaged over application number and compared across treatments.

In the B. tectorum site (Site 1) at 2 YAT (2016), all three functional groups had significant establishment in every indaziflam treatment compared with the nontreated check (Table 5). Both imazapic treatments also had significant C3 grass establishment (Table 5). At 3 yr after initial herbicide treatments, all treatments that included indaziflam continued to have a higher frequency of drilled species compared with the nontreated check (Table 5). Imazapic treatments also had significant establishment of C3 grasses at 3 YAT, although C3 frequency averaged 24 ± 5.1% for imazapic treatments and 61 ± 1.7% for indaziflam treatments (Table 5).

Russian thistle (Salsola tragus L.) invaded the S. cereale site (Site 2) at 2 YAT in plots where S. cereale was controlled and negatively impacted the continued establishment of the warm-season grasses. Over the course of the study, warm-season grasses that originally established decreased in frequency. By 3 YAT, less than half of the indaziflam treatments still had significant establishment of C4 grasses compared with the nontreated check (Table 6). Although there was some successful C4 grass establishment, the average frequency in indaziflam treatments was only 9% in Site 2 compared with 47% in Site 1 (Tables 5 and 6). At 2 and 3 YAT, all treatments that included indaziflam had better C3 grass and forb/shrub establishment compared with the nontreated check, with the exception of indaziflam at the lowest rate (44 g ai ha−1) (Table 6). Overall, C3 grasses had greater establishment and were less impacted by the S. tragus invasion in Site 2, as frequency increased from an average of 16 ± 1.4% at 1 YAT to 46 ± 2.6% at 3 YAT. There was no establishment of any drilled species in Site 2 among treatments that did not contain indaziflam (Table 6).

Invasive Winter Annual Grass Response at the Site with a Remnant Native Plant Community

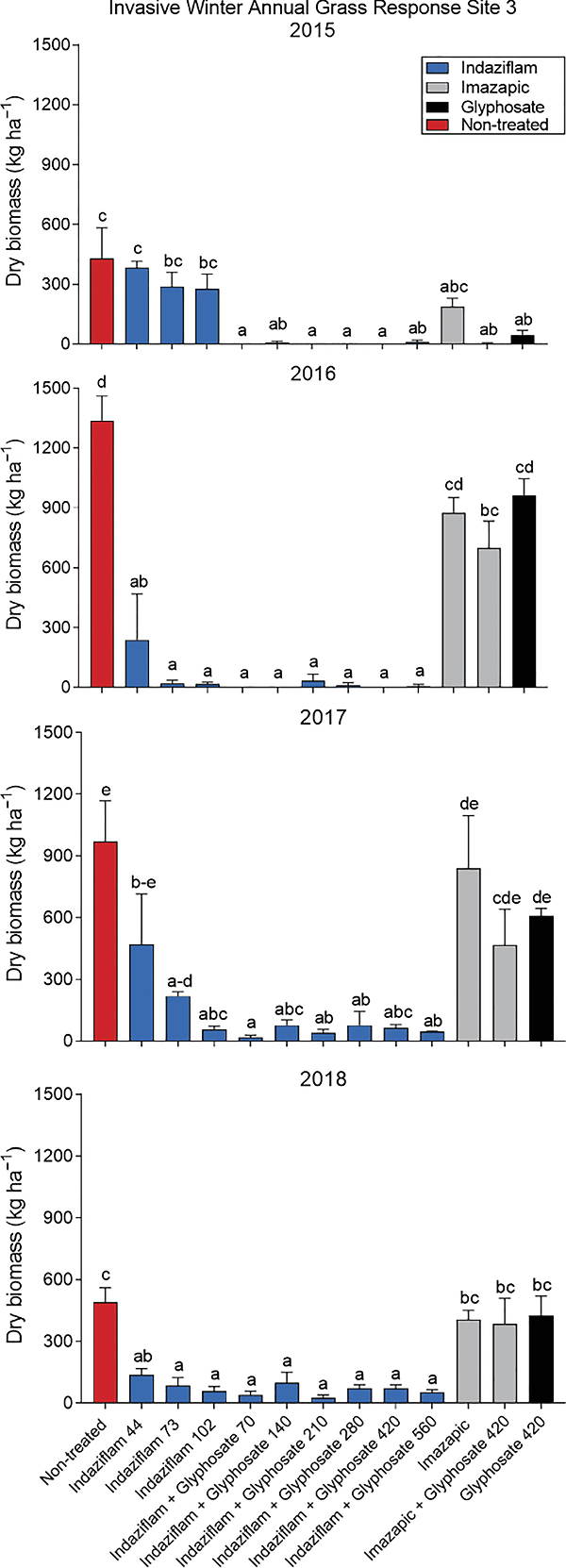

At Site 3, an analysis of Bromus (B. tectorum and B. arvensis) biomass in the nontreated plots showed a difference in biomass across years (P = 0.0016), with 2016 having significantly more Bromus than other years. Due to this variability in Bromus biomass, each year was analyzed separately to meet normality assumptions. All 4 yr of the study had a highly significant treatment effect (P < 0.001). During the growing season following initial herbicide applications, only treatments containing glyphosate reduced Bromus biomass (Figure 4). At 1 YAT, all treatments containing indaziflam and the imazapic with glyphosate treatment had less Bromus biomass compared with the nontreated check. Two and three YAT, only the indaziflam treatments, with the exception of the lowest rate of indaziflam (44 g ai h−1), were significantly reducing Bromus biomass (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Invasive winter annual grass (Bromus tectorum and Bromus arvensis) biomass response to herbicide treatments at Site 3, year of treatment (2015), 1 yr after treatment (YAT) (2016), 2 YAT (2017), and 3 YAT (2018). Application timing was after Bromus emergence (POST) in April 2015. Letters indicate differences among herbicide treatments by year, using least-squares means (P < 0.05). Herbicide treatments are as follows: indaziflam (44, 73, 102 g ai ha−1), indaziflam (73 g ai ha−1) plus glyphosate (70, 140, 210, 280, 420, 560 g ae ha−1), imazapic (122 g ai ha−1), imazapic (122 g ai ha−1) plus glyphosate (420 g ae ha−1), and glyphosate (420 g ae ha−1).

Perennial Grass, Forb, and Species Richness Response at the Site with a Remnant Native Plant Community

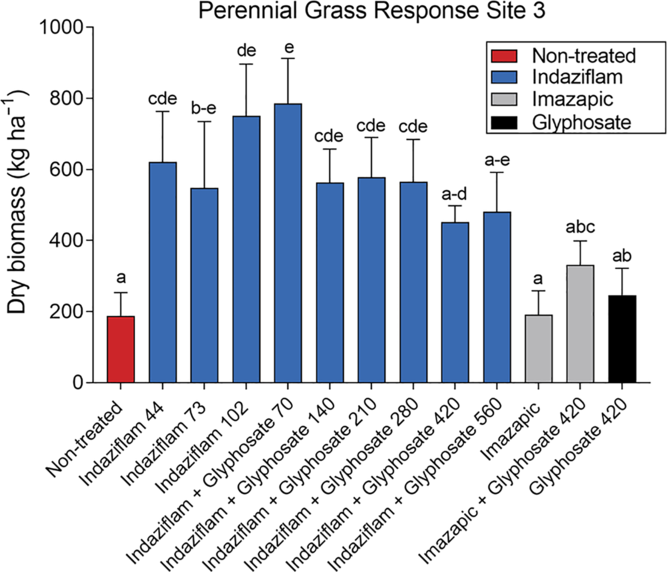

Year and the interaction of treatment by year were not significant for perennial grass biomass, while treatment was highly significant (P < 0.001); therefore, perennial grass biomass was combined across all years and analyzed by treatment. With the exception of the indaziflam treatments with the highest glyphosate rates (420 and 560 g ae ha−1), treatments containing indaziflam had increases in perennial grass compared with the nontreated check. Treatments without indaziflam did not increase perennial grass biomass (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Perennial grass biomass response to herbicide treatments at Site 3, all 4 yr combined. Letters indicate differences among herbicide treatments, using least-squares means (P < 0.05). Herbicide treatments are as follows: indaziflam (44, 73, 102 g ai ha−1), indaziflam (73 g ai ha−1) plus glyphosate (70, 140, 210, 280, 420, 560 g ae ha−1), imazapic (122 g ai ha−1), imazapic (122 g ai ha−1) plus glyphosate (420 g ae ha−1), and glyphosate (420 g ae ha−1).

The treatment by year interaction was not significant for forb biomass (P = 0.1017), although treatment (P = 0.0345) and year (P < 0.001) were significant; therefore, data were analyzed across treatments by year. Throughout the 4 yr of the study, differences in forb biomass were highly variable by year. In the initial application year (2015), very few differences were seen in forb response, with increased biomass only in treatments of the highest indaziflam rate (102 g ai ha−1) and glyphosate (420 g ae ha−1) alone (Supplementary Figure S2). At 1 YAT, treatments increased forb biomass, with the exception of indaziflam at 44 g ai ha−1, indaziflam plus glyphosate at 70 g ae ha−1, and imazapic alone. Although there were still significant B. tectorum and B. arvensis reductions among indaziflam treatments at 2 and 3 YAT, forb biomass differences were no longer observed (Supplementary Figure S2).

Finally, any impacts to species richness from herbicide treatments were analyzed. Because the treatment by year interaction was not significant (P = 0.9523), treatment effects on species richness were analyzed across treatments by year. Increases in species richness were variable throughout the study, most likely influenced by interannual variation in moisture. Increases in species richness were observed in approximately half of the indaziflam treatments in the season following treatment and at 1 and 3 YAT, while treatments without indaziflam did not have greater species richness throughout the course of the study (Supplementary Figure S3). In 2017 (2 YAT) there were no differences in species richness observed among treatments, although this was following severe drought conditions in 2016 (Supplementary Figure S3).

Glyphosate can be a critical component in IWAG management systems, because it provides POST control and can be applied alone or in combination with products that provide long-term soil residual control (Morris et al. Reference Morris, Morris and Surface2016). In sites with remnant desirable species, glyphosate can be used for IWAG control when native species are dormant. A review of several glyphosate labels showed recommended rates to control B. tectorum and S. cereale varying from 315 to 433 g ae ha−1 (Anonymous 2014, 2015, 2017). The results of our dose–response study suggest that higher glyphosate rates may be needed depending on site or species present. Secale cereale biomass was only reduced to near zero at 560 g ae ha−1 of glyphosate, which is more than the highest recommended rate for IWAG control (Figure 1; Supplementary Figure S1). This information is critical for land managers, as the recommended labeled rates for glyphosate may not be enough to control some IWAGs in highly invaded sites. Therefore, these data suggest that glyphosate rates may need to be altered to fit the target species and invasion level at each site.

Previous research has shown that IWAGs quickly reinvade areas after herbicide application, even when adequate first-year control is attained (Davies Reference Davies2010; Davies and Boyd Reference Davies and Boyd2018; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Monaco and Rigby2009). Sebastian et al. (Reference Sebastian, Nissen, Sebastian and Beck2017b) looked at the B. tectorum seedbank longevity and found that at least 4 yr with no additional seed rain were needed to prevent reinvasion from the soil seedbank. That research indicated that the reinvasion is most likely occurring from the seedbank at the site and not from new seed moving in from adjacent areas. Our results suggest indaziflam could provide the length of IWAG control needed to deplete the soil seedbank with just one herbicide application. At the termination of this study at 3 YAT, indaziflam (73 g ai ha−1 or higher) was still providing significant IWAG control at all three sites with just one application. Interestingly, similar results in long-term control were achieved at sites void of native species (Sites 1 and 2) and a site with a remnant native plant community (Site 3), although revegetation was required in the sites without a remnant community. In some sites, especially with annual grasses that are more difficult to control, such as S. cereale, higher rates or two applications may be needed to achieve the goal of depleting the annual grass seedbank.

Results from the current study suggest that indaziflam could play an important role in the restoration process at sites with a remnant native plant community and in highly degraded sites where revegetation will be required. In sites with a remnant native plant community, native species can reestablish from the existing community through persistent IWAG control (Monaco et al. Reference Monaco, Mangold, Mealor, Mealor and Brown2017; Sebastian et al. Reference Sebastian, Sebastian, Nissen and Beck2016b, Reference Sebastian, Fleming, Patterson, Sebastian and Nissen2017a). The native plant community responded to treatments in our study that provided multiyear reductions in Bromus biomass, with increases in perennial grass biomass and species richness still evident even at 3 YAT. In a comprehensive review by Monaco et al. (Reference Monaco, Mangold, Mealor, Mealor and Brown2017), an evaluation of perennial grass impacts after IWAG management indicated that increases in perennial grass are often only a short-term response (<2 yr). Our results suggest that with multiyear IWAG control, increases in perennial grass biomass and native species richness can be achieved on a longer-term or more permanent basis.

Our study was the first to evaluate revegetation using drill seeding after indaziflam applications. The successful establishment of grasses, forbs, and shrubs in the indaziflam treatments demonstrates that drill seeding after indaziflam applications is potentially an option, although more research is needed to determine adequate plant-back intervals, depths, and species selection. Soil properties and environmental factors, especially precipitation, also play a large role in successful seedling establishment. One notable finding in this study was that significant establishment of drill-seeded species only occurred within treatments that provided more than 1 yr of IWAG control. Seeded species continued to persist throughout the 3 yr of the study, although some functional groups performed better than others. At 3 yr after seeding, there was a higher frequency of C3 grasses in almost all treatments that continued to provide IWAG control, while C4 grass establishment did not persist in most treatments at the S. cereale site. The forb and shrub populations did persist through the 3 yr of evaluations at both Sites 1 and 2, although the overall frequency of these species was not as high as C3 grass frequency. These results support past research indicating that species selection plays an important role in long-term persistence of seeded plants and in providing competition against reinvasion (Rinella et al. Reference Rinella, Mangold, Espeland, Sheley and Jacobs2012).

Even when initial establishment of desirable species is achieved, revegetation efforts often fail, as weeds reinvade the site and inhibit seeded species from persisting (Rinella et al. Reference Rinella, Mangold, Espeland, Sheley and Jacobs2012). An additional management strategy that requires future research is to utilize a tool such as indaziflam as a protective treatment after revegetation has occurred. Land managers could make indaziflam applications after initial seedling establishment and potentially prevent IWAG reinvasion from the soil seedbank. This could provide multiyear protection from IWAGs during the critical establishment period for desirable species and would eliminate the concern of plant-back intervals.

Multiyear control efforts are needed to deplete the IWAG seedbank and allow time for native species recovery or species establishment through revegetation methods (Chambers et al. Reference Chambers, Bradley, Brown, D’Antonio, Germino, Grace, Hardegree, Miller and Pyke2014; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Monaco and Rigby2009; Sebastian et al. Reference Sebastian, Nissen, Sebastian and Beck2017b). In highly degraded sites without a remnant native plant community, establishing desirable species in a way that is sustainable requires long-term weed control and adaptive management in order to be successful. The ultimate goal is a sustainable plant community that can be resistant to reinvasion or new invasions (Davies Reference Davies2010; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Monaco and Rigby2009; Rinella et al. Reference Rinella, Mangold, Espeland, Sheley and Jacobs2012; Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Orloff, Lancaster, Kirby and Carlson2010). Our results demonstrate that indaziflam is a viable tool to achieve the goal of seedbank depletion and restoration of non-crop sites where revegetation is required.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express appreciation to Colorado Parks and Wildlife and Boulder County Parks and Open Space for allowing the use of their properties for this research. The authors would also like to express appreciation to Andrew Kniss for assistance with the statistical methods. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or the commercial or not-for-profit sectors. No conflicts of interest have been declared.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/inp.2020.23