Introduction

Being a modern politician is a tough task. Repeatedly, studies document and personal narratives report that politicians work under constant pressure (Flinders et al. Reference Flinders, Weinberg, Weinberg, Geddes and Kwiatkowski2020; Mannevuo Reference Mannevuo2020; Weinberg Reference Weinberg and Weinberg2012,Reference Weinberg2017), forcing them to prioritize among multiple important tasks. For instance, the Bennett Institute (2022, 20) reports that ‘legislative scrutiny is simply not their [UK MPs] priority […]. MPs […] prioritise activities that are more visible and understandable to the public and specific constituents, not least to demonstrate their value at the next election’. Similarly, a former Danish member of parliament explains the following (Altinget 2022, author’s translation):

I was caught in a logic that dictated that I should sacrifice all my time on politics based on one fundamental goal: I should be re-elected at the next election. When that logic determines your understanding of your role as a politician, you feel guilty if you are not sufficiently active on social media, if you do not try to get in the media on any issue that might attract attention […].

In both cases, politicians tend to prioritize representative tasks that provide visibility at the expense of tasks associated with invisible and complicated policy decision making. These priorities, I argue, are key to political representation.

Institutional reforms to organize parliamentary work differently or increase politicians’ administrative support have been suggested to mitigate the pressure experienced by politicians. While resources may indeed be slim in many systems, it is noteworthy that experiences of pressure are widespread across systems with different institutional and financial resources and that reforms of legislative work aimed at lessening politicians’ burdens have not been successful (Mannevuo et al. Reference Mannevuo, Rinne and Vento2022; Weinberg et al. Reference Weinberg, Cooper and Weinberg1999). Resource increase does not solve the fundamental ’endlessness’ of representative tasks facing politicians. Independently of how many (staff) hours a politician spends in the constituency, there is always another service to be provided or another community event to attend. Regardless of how many (staff) hours a politician spends on getting to the bottom of complex regulation or possible government misconduct, there is always another report to read or another stakeholder to consult. Increased resources may help politicians do even more, but how it impacts political representation depends on how MPs prioritize the resources available to them.

The immediate question jumping from this argument is: Which tasks should then be prioritized? Theoretically, the answer can be provided from multiple angles. Normative theories may suggest notions of ‘good’ or ideal types of political representation as a relevant standard of evaluation (Pitken Reference Pitken1967). Sociological institutionalist approaches may point towards norms of appropriateness among (groups of) politicians, defining their role as representatives (Searing Reference Searing1994). Positions inspired by rational choice will consider the balancing of efforts and goal achievements (Strøm Reference Strøm1997).

This study proposes looking towards voters’ standard of representative task priority. Voters are relevant for normative as well as rational choice theoretical reasons (Wolkenstein and Wratil Reference Wolkenstein and Wratil2021). Voters constitute demos and thus a relevant – though potentially not the sole – normative standard for setting politicians’ task priority. Voters also constitute the main principal and concern of re-election motivated politicians (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974) as reflected in the Bennett Institute’s report and the statement of the Danish MP above. As such, voters’ standard of representative task priority is of high relevance to democracy.

Studies of voters’ evaluation of politicians are plentiful; however, only a few include task priority as a standard of evaluation. Studies generally show that voters prefer ‘local’ politicians focusing on representing the district rather than the party but without specifying any tasks (Bøggild Reference Bøggild2020; Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Cowley, Vivyan and Wagner2019b; Wagner et al. Reference Wagner, Vivyan and Glinitzer2020). Other studies include specific tasks such as parliamentary activities (Butler et al. Reference Butler, Hughes, Volden and Wiseman2023; Hargrave and Smith Reference Hargrave and Smith2024) or spending time in the constituency (Campbell and Lovenduski Reference Campbell and Lovenduski2015; Vivyan and Wagner Reference Vivyan and Wagner2016) but do not systematically contrast different tasks, or they collapse tasks and other dimensions of representation (for example, focus and style), making task priorities difficult to interpret.

This study aims to develop and evaluate a conceptual framework for analyzing and operationalizing politicians’ task priority standard. Tasks are defined as activities politicians can perform individually. This definition excludes other relevant standards. For example, outcome delivery such as improving the economy or securing the healthcare system requires joint efforts to which the individual politician may contribute but cannot control. Combining insights from the literature on political representation and legislative studies, I propose two categories of tasks: (1) Relational tasks which politicians carry out as representatives with the aim of building or maintaining relations to voters, for instance by spending time in the constituency, communicating with voters on social media, or taking time to read and answer emails from voters; and (2) functional tasks which relate to politicians’ institutional role as legislators such as scrutinizing bills, controlling government actions, or bringing issues forward in parliamentary debates. I present two sets of competing, pre-registeredFootnote 1 hypotheses regarding voter preferences. First, based on existing public opinion literature, voters are hypothesized to prioritize relational tasks. Second, based on an argument of task visibility and power, voters are hypothesized to prioritize functional tasks.

The relevance of the conceptual framework is explored, and the hypotheses are tested using country comparative survey data collected among demographically representative samples of Danish (N = 2,454), German (N = 2,095), UK (N = 2,849), and US (N = 2,554) voters. Data was collected by YouGov in January 2025. The survey structure and analyses follow four steps, moving from an explorative to a deductive research approach – from qualitative content coding of open-ended answers to a conjoint candidate choice experiment manipulating the task priority of fictitious politicians.

The analysis shows, first, that voters do consider functional and relational tasks when just thinking about politicians’ tasks even though other standards of evaluation also exist, such as outcome delivery and more abstract notions of representative focus. Second, across rating, ranking, and experimental survey questions, functional tasks are prioritized higher than relational tasks. Third, voter task preferences vary across countries in accordance with the representative relations promoted by the electoral systems. This indicates a potential representative mismatch between politicians turning towards visible, relation tasks while voters prefer politicians to give higher priority to functional tasks. The theoretical and empirical relevance of the proposed conceptual framework is further discussed in the concluding section.

Representation as a Task

This study contributes to the century-long interest in conceptualizing and studying political representation. The core idea is that from the point of view of an elected politician, representation is a practical endeavor engaging in a variety of activities to promote specific goals. Plausibly, the goals are easier to set than planning the activities: Once elected ‘[a] congressman must decide what to make of his job. The decisions most constantly on his mind are not how to vote, but what to do with his time, how to allocate his resources, and where to put his energy‘ (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Pool and Dexter1963, 405). How politicians end up making this decision is consequential for the quality of representation. This study proposes a conceptual framework for a systematic analysis of representative task priority, defining tasks as activities under the control of the individual politician and distinguishing between two core tasks: relational tasks, which involve maintaining contact with constituents, and functional tasks, which involve engaging in legislative work. Both tasks, as well as their combination, are key to political representation, and politicians and voters are therefore likely to assign importance to both of them. However, when faced with time constraints, the bundle of tasks will reflect different preferences for relational and functional tasks, respectively.

Relational Tasks

Representation is inherently relational. Representation makes something that is absent present (Pitken Reference Pitken1967, 8–9). Without the absent ‘something’, there can be no representation. As elected representatives, politicians stand and act for voters, and it is the qualities of the voter–politician relation that determine the form and quality of representation.

The relational nature of representation is prominent in classic as well as newer theories on representation. Wahlke et al. (Reference Eulau, Wahlke, Buchanan and Ferguson1959) famously conceptualized the relation by the focus and style of representation. Representative focus refers to the group of voters politicians have in mind as their main constituency. This may be very general, such as voters of the country, or more specific, such as voters of a specific district, party, or social group. Representative style concerns the mandate politicians perceive to hold as either a delegate acting upon instructions from voters and trustees, using their own conviction to promote the perceived interests of voters, or a politico combining styles of delegation and trusteeship depending on the situation. This conceptualization has been highly influential, guiding many studies of political representation (among new publications using the conceptualization are Close et al. Reference Close, Legein and Little2024; Dynes et al. Reference Dynes, Hassell and Miles2023; Ferguson Reference Ferguson2024). Importantly, this conceptualization guides research towards the perception and mindset of politicians. It is thus politicians who define the representative relation to voters by consciously or unconsciously taking on a specific focus or style.

The relational character of representation is also at the core of the newest ideas in representation theory. Not least has the constructivist turn (Disch Reference Disch, Disch, van de Sande and Urbinati2019) highlighted representation as a relational construct. It differs from the classic theories by moving beyond traditional conceptions of democratic representation connected to election and legislatures (Wolkenstein and Wratil Reference Wolkenstein and Wratil2021) and making receivers of representation equally important for defining the representative relationship (Saward 2010). Representatives – politicians, influencers, etc. – seek to form representative relationships by making representative claims (Saward Reference Saward2006). These claims may be accepted or rejected by the targeted constituents, who hereby confirm the representative relationship. The empirical application of these ideas is still limited (Blumenau et al. Reference Blumenau, Wolkenstein and Wratil2025; Wolkenstein and Wratil Reference Wolkenstein and Wratil2021); however, they do entail taking voter perceptions and mindsets into account when studying political representation.

Across classic and new theories of political representation, the relation between voters and politicians is the center of attention. This points towards the first category of representative tasks: the relational tasks performed by politicians to build and maintain supportive relations with voters. These are the type of activities Fenno (Reference Fenno1978) observed in Home Style as he shadowed members of the US House of Representatives approaching voters in their home districts. And they are the type of activities Mansbridge (Reference Mansbridge, Castiglione and Pollak2018) calls upon politicians to invest more time in by intensifying ‘recursive’ two-way communication and leaving more policy crafting to their staff. Relational tasks concern activities through which politicians can stay in close contact with voters. They are activities that make politicians available, approachable, and communicative.

Public opinion literature indicates that the Mansbridge quest for relational task priority may well be in accordance with voter preferences. Although few studies ask voters directly to express their preferences regarding representative tasks – understood as activities rather than focus of style – two studies of British voters show that (1) a majority (55 per cent) found ‘Taking up and responding to issues and problems raised by constituents’ to be the most important task of politicians, followed by ‘Being active in the constituency’ (28 per cent) (Campbell and Lovenduski Reference Campbell and Lovenduski2015), and (2) that they prefer candidates spending more time in the constituency (Wagner & Vivyan Reference Vivyan and Wagner2016). This is in line with a more substantial body of research on voters’ preferences regarding politicians’ focus and style. Across different political systems, voters are shown to prefer politicians who respond more to constituency concerns than party concerns in their vote cast (Bøggild Reference Bøggild2020; Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Cowley, Vivyan and Wagner2019a; Carson et al. Reference Carson, Koger, Lebo and Young2010; Wagner et al. Reference Wagner, Vivyan and Glinitzer2020). These activities confirm politicians’ status as ‘friends or neighbors’ (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Cowley, Vivyan and Wagner2019b), which assures voters that their politicians stand and act for them. Moreover, studies in political psychology show that voters prefer relational traits such as warmth over functional traits such as competence (Laustsen and Bor Reference Laustsen and Bor2017) and prefer candidates signaling a social-psychological attitude proximity (Baron et al. Reference Baron, Lauderdale and Sheehy-Skeffington2023) and thus social-relational consensus.

In combination, these studies and theories of political representation build a strong case for voters to prefer relational tasks:

HYPOTHESIS 1a: Voters prefer that politicians attend more to relational tasks relative to functional tasks.

HYPOTHESIS 1b: Voters are more likely to select candidates stating prioritization of relational tasks rather than candidates stating prioritization of functional tasks.

Functional Tasks

In contrast to representation theory, legislative theory is more concerned with the functional tasks of legislature. Whereas the job description of politicians is slim, the description of parliaments’ functions is well established (Packenham Reference Packenham, Kornberg and Musolf1970; Kreppel Reference Kreppel, Martin, Saalfeld and Strøm2014; Martin and Strøm Reference Martin and Strøm2023): legislative assemblies should legislate, exercise control over the government, and deliberate while representing the public in parliamentary procedures. However, parliaments are institutions rather than actors. They require agency from politicians to fulfill their functional purposes. No individual politician can legislate or sanction the government as it requires a (qualified) majority. However, each individual politician can contribute to the functioning of parliament by performing functional tasks such as scrutinizing legislative proposals (for example, reading briefs, consulting stakeholders, or asking ministers for accounts); controlling government actions (for example, reading and reacting to reports from the Ombudsman, Audit General, or other ‘fire alarm’ agents [McCubbins and Schwarts Reference McCubbins and Schwartz1984] calling ministers to provide evidence); or engaging in parliamentary debates representing and aggregating attitudes and interests in plenary, committees, or caucuses.Footnote 2 Functional tasks thus concern the institutional role of a politician as a legislator acting on behalf of voters in the legislative processes and settings.

Classic as well as newer legislative literatures question politicians’ motivation for engaging with these functional tasks. King (Reference King1976) famously described different modes of operandi between government and parliament, which due to partisanship and opposition–government competition for office mainly leave the legislative scrutinizing and government controlling functions to the opposition politicians. Such activities among opposition politicians have been argued to be motivated by vote-seeking and office-seeking aspirations, engaging primarily in cases salient to voters and harmful to the government, while other cases may be left aside (Behrens et al. Reference Behrens, Nyhuis and Gschwend2023).

Especially when working under time pressure, functional tasks may be de-prioritized because they are troublesome, their impact is uncertain, and their public visibility slim. For instance, it takes time to understand the efficiency of a policy proposal in solving the intended problem and to understand the possible unintended and perhaps undesirable side effects. It requires reading, and talking to stakeholders and bureaucrats – activities that are not publicly visible. Moreover, the likelihood of making changes to a bill depends also, and sometimes even more, on majority formation logics rather than well-prepared arguments. Politicians may thus leave the legislature behind, making it a toothless institution compared to the executive. The persistent ‘parliamentary decline thesis’ should not be overstated. Parliaments do indeed participate actively in the legislative process (Russel and Gover Reference Russell and Gover2017). But studies do also show that legislative processes are speeding up, leaving less time for scrutiny; executive control is more partisan than constitutional (IPU 2017; Green-Pedersen Reference Green-Pedersen2010); and politicians are found to spend more time on relational tasks such as constituency work (Norton Reference Norton1994) and public communication on conventional or social media platforms (Pedersen Reference Pedersen2022).

Very few studies ask voters about their preferences for activities related to functional tasks. Studies investigating the electoral effects of parliamentary activity tend to find a positive correlation between parliamentary activity and electoral results, suggesting that voters care about these tasks (Däubler et al. 2016; Kellermann Reference Kellermann2013; Loewen et al. Reference Loewen, Koop, Settle and Fowler2014). However, these studies only measure the correlation between visible activities and electoral performance; they do not take the invisible activities of reading, consulting, and negotiating into account. Experimental work has made the invisible performance of politicians visible and finds that voters do reward legislative effectiveness and productivity (Butler et al. Reference Butler, Hughes, Volden and Wiseman2023; Hargrave and Smith Reference Hargrave and Smith2024), but these studies do not compare the importance of such functional tasks to the importance of the suggested relational tasks.

There are reasons to expect that voters do indeed give or can give high priority to functional tasks. First, while the relational character of representation is unquestionable, the relationship may not be the main purpose of political representation. As Wolkenstein (Reference Wolkenstein2024) argues, representational relationships that provide the representative access to significant powers are more crucial than relationships entailing mainly identification and followship but no formal powers. It is through functional tasks that politicians enact the power delegated to them by the voters. Without attending to those tasks, the representative relationship becomes less relevant. Functional tasks circumscribe or constitute the purpose of the relational tasks and should, therefore, be given relatively higher priority.

Second, due to the invisibility of functional task activities that limit voters’ ability to monitor politicians’ functional performance, they may turn to more observable proxies of performance focusing on the visible relational tasks. However, if visibility is provided, voters do seem to care (Butler et al. Reference Butler, Hughes, Volden and Wiseman2023; Däubler et al. Reference Däubler, Christensen and Linek2018), and perhaps even more so if the time constraints demanding task prioritization also become clear to voters, just as it is for politicians juggling both tasks all the time.

Given the opportunity to reflect upon and evaluate ‘invisible’ functional tasks and arguing that power is entailed in political representation as exercised through functional tasks, it is possible to formulate a competing set of hypotheses regarding voters’ standard of representative task priority:

HYPOTHESIS 2a: Voters prefer that politicians attend more to functional tasks relative to relational tasks.

HYPOTHESIS 2b: Voters are more likely to select candidates stating prioritization of functional tasks rather than candidates stating prioritization of relational tasks.

Research Design

The relevance of the conceptual differentiation between relational and functional tasks is explored and the hypotheses tested using survey answers from respondents in four Western democracies: Denmark (N = 2,454), Germany (N = 2,095), the United Kingdom (N = 2,849), and the United States (N = 2,554). The surveys were administered by YouGov, and respondents were recruited to match the country-specific population of voters on sex, age, education, and region. The survey was fielded 6 January and closed 23 January 2025. A total of 9,957 citizens entered the survey, 1,427 did not sign the consent form and stopped the survey, and five did not pass the opening attention check. In sum, 8,525 citizens completed the survey.

The four countries are selected as examples of established liberal democracies in which voters have evaluated their politicians in free elections over many generations. Within this population of established liberal democracies, the four countries are selected to maximize variation across cases to increase the generalizability of the conclusions. The countries provide variation in terms of regime type (US: presidential; DK, UK, DE: parliamentarian), chamber structure of legislature (DK: one chamber; UK, US, DE: two chambers), electoral system (DK: proportional, multimember district; UK, US: majoritarian, single-member district; DE: mixed-member system), and unity (UK, DK: unitary states; DE, US: federal systems). Beyond these institutional features, the four countries also represent nations of different sizes (population and area), media systems, and welfare state systems. These differences are taken to influence representative linkages. For instance, elections in single-member districts are argued to promote an emphasis on district representation among politicians (Cain et al. Reference Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1987), which may also apply to voters. Similarly, members of the US Congress have been described as more individualistic than their more party-collectivist European counterparts (Esaiasson Reference Esaiasson, Esaiasson and Heidar2000), which may also translate into voters preferring greater attention to the party.

Taking these factors into account, the United States can be perceived as a most likely case for finding support for relational task preferences (H1a–b) as voters in this large, federal nation with single-member district elections and a restrictive welfare state may be more concerned with the relational tasks of politicians maintaining contact with local problems and providing services to the district. In contrast, Denmark can be perceived as a most likely case for finding support for functional task preferences (H2a–b) as voters in this small nation with proportional elections and a universal welfare state may be less concerned with the relational tasks of politicians relative to politicians’ efforts in managing national policy.

This most different system logic of case selection constitutes a strong design for providing generalizable findings regarding voters’ views on politicians’ task priority. However, the multiple differences across the four countries that come with this design make it impossible to isolate country-level factors possibly influencing variation in voters’ preference for representative task priority. This study will, therefore, possibly contribute to the formulation of new hypotheses for how voters’ standard of representative task priority is likely to vary across political systems.

The survey instrument consists of four elements. First, by order of appearance in the survey, respondents were asked (UK version): ‘Members of parliament handle various tasks, and there is no specific job description, so it is up to each politician to prioritise their time among these tasks. Off the top of your head, what do you think is the most important task for a member of parliament to attend to?’ The open answers provided to this question minimize the research situation and priming effects and provide nuanced and spontaneous notions of voters’ spontaneous standard of politicians’ task priority. This exploratory, open-ended question design is helpful for evaluating the extent to which the conceptual framework of functional and relational tasks fits voters’ first-order concerns (Ferrario and Stantcheva Reference Ferrario and Stantcheva2022).

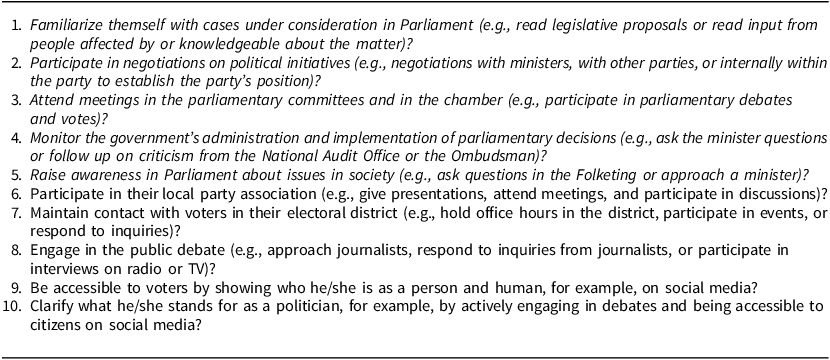

Second, voters were presented with a list of relational and functional tasks (Table 1 from the UK survey; other versions are available in the appendix) and asked to indicate on a scale from 0 to 10 how important each task was for politicians to attend to. The list is designed to include an equal number of activities of functional and relational tasks and to include the most dominant tasks given in the literature. The functional tasks are operationalized to reflect key parliamentary functions as defined by legislative theory. This includes legislative scrutiny (#1 in Table 1), legislative initiative (#2), representation of interests in debates (#3), executive control (#4), and representation of interests through parliamentary agenda-setting (#5) (Martin and Strøm Reference Martin and Strøm2023). Relational tasks are operationalized to cover constituencies stated as most important to politicians (Esaiasson and Heidar Reference Esaiasson and Heidar2000): the party (#6), the electoral district (#7), and all voters (#8–10); to include bottom-up (#6–8) as well as top-down actives (#9–10) (Andeweg and Tomassen Reference Andeweg and Thomassen2005); and to include the most relevant channels of communication: on-site presence, mass media, and social media. The task descriptions are intended to be as neutral and informative as possible, reducing possible social desirability effects.

Table 1. List of functional and relational tasks

Note: Functional tasks are indicated by italics, which are not shown in the survey. The table shows the UK version of the task list. Lists for DK, DE, and the US are included in the appendix.

Third, respondents faced the same list but had to allocate the share of working hours they wanted politicians to spend on each task during a week, adding up to 100 per cent. In contrast to the second step, where task importance was rated, this third step involved an explicit prioritization of the various tasks, which reflects the dilemmas facing politicians and pushes respondents further in expressing their standards for prioritization by revealing how they rank the various tasks in terms of time investment.

Fourth, respondents participated in a forced choice, conjoint vignette experiment. Moving beyond rating and ranking, the experiment involves comparison of voters’ concern with task priority relative to other relevant candidate attributes. This therefore constitutes a test of not only the priority of functional tasks relative to relational tasks but also the relative importance of task performance to other parameters influencing candidate choice. Moreover, the experiment includes an alternative formulation of representative tasks as it must align with how politicians may call attention to their task priorities. Hereby, the voter standard of representative task priority is compared to other relevant standards and methodologically triangulated against a different wording of operationalization.

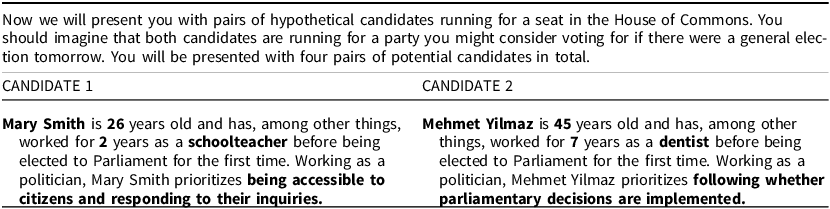

The experiment includes six candidate attributes: sex, age, ethnicity, education, work experience, and task priority. Respondents were presented with four pairs of candidates and asked to choose the one they preferred based on the information given. Table 2 presents an example of the choice respondents were presented with (UK version).

Table 2. Candidate choice, conjoint experimental design

Note: Bold text (not in survey text) indicates the manipulated attributes.

Attributes were selected to include the most important descriptive characteristics of politicians. Policy characteristics are held constant by asking voters to consider a candidate running for a party whom they would consider voting for.

Sex and ethnicity are varied by name using common ethnic majority and ethnic minority first and second names. Specifically, Turkish names are used to signal ethnic minority status as this minority constitutes a relevant and name-recognizable group in all countries. More majority names (66 per cent) are included than minority (33 per cent) to approximate the fewer minority candidates running for election.

Age is operationalized into three levels: young (25–34 years), medium (40–54), and older (60–65). To accommodate the prevalence of middle-aged candidates, fewer young (32 per cent) and older (19 per cent) candidates are included compared to medium-aged (48 per cent) candidates.

Education is included to signal social class and operationalized into three levels: short (for example, hairdresser, painter, social and healthcare assistant), medium (for example, schoolteacher, nurse, accountant), long (for example, doctor, lawyer, psychologist). To accommodate the prevalence of candidates with long education, fewer candidates with short (25 per cent) and medium (32 per cent) education are included compared to candidates with long education (44 per cent).

Work experience is a signal related to perceptions of career politicians or politicians as ‘ordinary’ people (Clark et al. Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2018). It is operationalized as the number of years the candidate has worked in their profession before getting elected to parliament. There are three levels: short (1–3 years), medium (7–9 years), and long (13–15 years). The maximum level of 15 years is set to allow for randomization across levels of age. However, as young candidates (25–34 years) are unable to have worked professionally for a longer period, especially if combined with a long education, the randomization is restricted so that young age is always combined with short work experience.

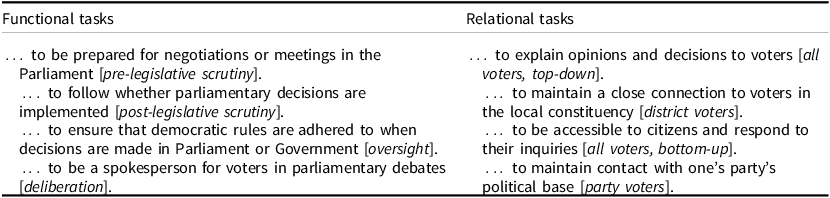

Task priority is the central attribute and includes two levels specified in Table 3. Values are operationalized to cover all central parliamentary functions and key voter relations, while still limiting the number of values to maintain statistical power within each value. The formulations of the task priorities are intended to be equally attractive, minimizing possible social desirability. They are less informative (for example, including no task examples) than the formulations in the rating and ranking questions (Table 1), but they are more idiomatic, mimicking ways politicians could express task priorities to voters.

Table 3. Values for the two levels of task priority

Note: Square brackets […] indicate the key function or relation the value is intended to capture. UK version of task descriptions.

The order of survey instruments gives priority to the descriptive and exploratory aims of the study. It moves from very open, respondent-controlled instruments to more closed, researcher-controlled instruments to establish the voter standard of representative task priority. Reaching the experiment, respondents are pre-treated by engaging with the prior questions, which possibly accentuate the potential task effect. However, the main aim is not to determine the precise effect size of task evaluations in general but to compare across survey instruments which tasks – functional or relational – are relatively more important according to voters as they spontaneously think about politicians’ work, rate and rank them in relation to each other, and finally compare them to other candidate characteristics.

What Should Politicians Do?

The open answers were coded using ChatGPT 4.0. Codes for functional and relation tasks were pre-defined (see Table 4) in line with the theoretical definition, including only references to activities that individual politicians are expected to carry out. Based on manual coding of survey answers from Danish voters in a pilot study, five additional codes were defined by, first, conducting an inductive coding staying as close as possible to the words used and, second, conducting an axial coding of these words categorizing them into five analytical codes: Focus, Contract, Outcome, Trait, ‘Don’t know’ (see Table 4; more detail on the manual coding can be found in the appendix). The final coding scheme was operationalized into prompts instructing ChatGPT 4.0 how to classify the answers according to the codes. Coding validity and reliability were tested by comparing ChatGPT codes to manual codes across 200 randomly selected answers for each code (coding agreement ranges between 80 and 98 per cent; the coding process and results are described in detail in the appendix). The codes are not mutually exclusive; rather, one answer can express multiple preferences for how politicians should prioritize their tasks, which will be captured by this coding approach.

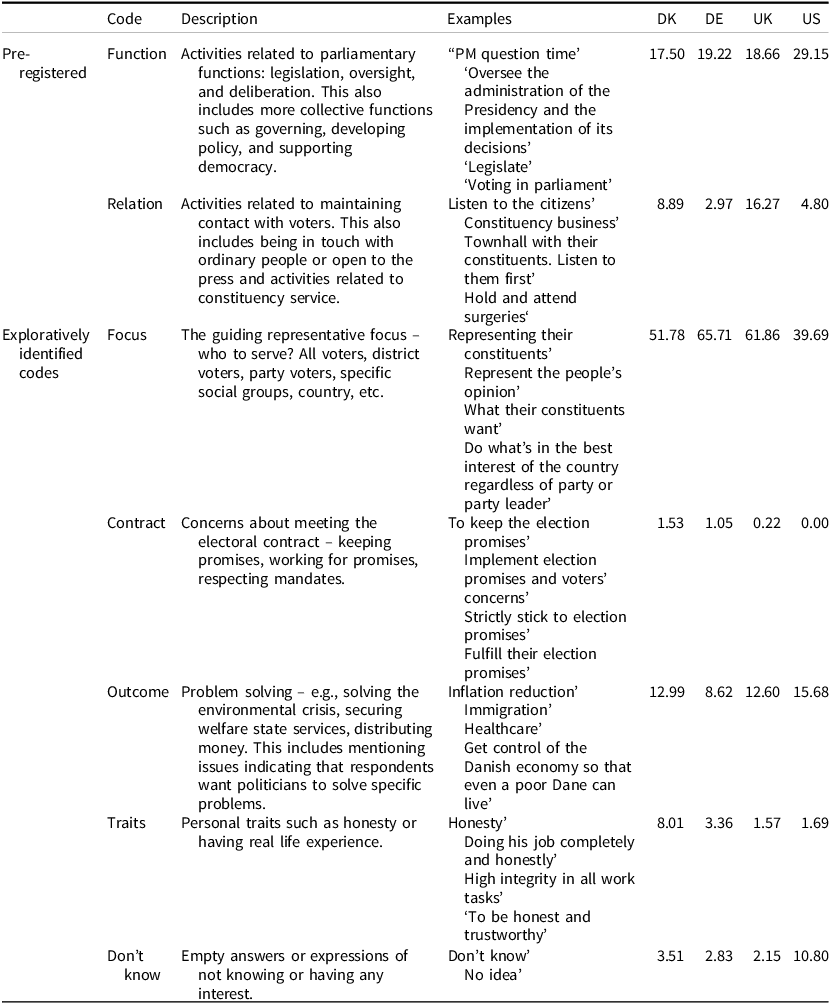

Table 4. Content and prevalence of open answers, per cent

Note: N DE = 2,086; N DK = 2,023; N UK = 2,229; N US = 2,185. Numbers indicate the share of answers including the given code. One answer may include more codes or none of the codes, so the percentages across codes do not add up to 100 per cent.

Table 4 shows that voters have multiple notions of what is important for politicians when just asked to think of the most important task. Some of the answers speak directly to which activities voters want politicians to prioritize, and these can all be meaningfully captured by the functional and relational tasks of politicians. In this way, the two types of tasks encapsulate voters’ ideas about representative activities. In total, 22–35 per cent of all answers spontaneously mention either functional tasks or relational tasks or both. This indicates that even though politicians’ activities are often hard to monitor and likely even difficult to define for many voters, a substantial number of the respondents point to specific tasks politicians should attend to rather than, for example, certain problems they want solved or general, abstract principles they associate with political representation.

For answers coded as Function, respondents indicate that politicians should legislate, study issues, attend meetings in the legislature and its committees, and debate important issues. Legislation is the most prevalent element in this code, but answers also express preferences for politicians to control the government and bring issues forward in the legislative assembly. Functional tasks are mentioned in 17 per cent (DK) to 29 per cent (UK) of the answers.

For answers coded as Relation, respondents indicate that politicians should ‘keep their finger on the pulse’, listen to people, and be present and active in their constituency. ‘Listen’ is a common term used for describing relational tasks, which is rather abstract but seems to indicate preferences for politicians being available rather than being information suppliers. Constituency services are also a common theme describing relational tasks. Communication tasks such as clarifying and explaining positions are less prominent in the answers, indicating that voters unprompted think of bottom-up rather than top-down relational tasks (Andeweg and Thomassen Reference Andeweg and Thomassen2005). Relational tasks are mentioned in 3 per cent (DE) to 16 per cent (UK) of the answers.

Across the four countries, functional tasks are mentioned more often than relational tasks, and the differences are statistically significant (p < 0.001) in all cases but that of the United Kingdom (p = 0.136). This offers the first support of H2a (functional tasks are more important than relational tasks), whereas it conflicts with the prediction of H1a (relational tasks are more important than functional tasks).

Table 4 also provides interesting insights into voters’ definitions of politicians’ most important tasks. In many cases, these answers do not concern ‘tasks’ as activities under the control of individual politicians. As such, representative task priority is a relevant, but not the only, standard of evaluation when voters think about politicians. For instance, respondents want politicians to solve societal problems and improve society, which are demands for Outcomes often not deliverable by an individual politician. This includes answers wanting politicians to handle immigration, inequality, the climate crisis, or inflation. Other answers relate to the intrinsic qualities of politicians rather than their activities. This includes personality Traits, of which honesty is most wished for, speaking indirectly to the widespread political distrust (Valgarðsson et al. Reference Valgarðsson, Jennings, Stoker, Bunting, Devine, McKay and Klassen2025).

Two other codes relate to the motivation behind task delivery. This includes Contract, which captures answers that express preferences for politicians to deliver on or work to promote their electoral pledges, mirroring ideas from principal–agent theory (Bergman et al. Reference Bergman, Müller, Strøm, Blomgren, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2003) and pledge democracy (Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser-Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017) perceiving politicians as delegates elected to deliver on their ‘election contract’. Answers coded under Focus express preferences for whose interests politicians should have in mind when conducting their work and mirrors the theoretical understanding of representative focus (Wahlke et al. Reference Eulau, Wahlke, Buchanan and Ferguson1959). This is typically expressed in broad and rather unclear notions such as ‘thinking about their constituency’, representing the people’, and ‘do what is best for the country’. Focus is the most prevalent aspect of the answers across all four countries, which may reflect respondents’ unfamiliarity with considering individual task performance. Instead, they provide more abstract notions of whom politicians should represent, without specifying particular activities.Footnote 3

Only a few respondents provide ‘Don’t know’ answers indicating that they have no idea or preferences regarding politicians’ task performance. Except for the United States, less than 5 per cent leave the answer empty or indicate not knowing.

The qualitative analysis of the open-ended answers documents that voters use different standards for evaluating politicians. Task priority is an important one of them, and when tasks are understood as activities, the answers align with the conceptual idea of functional and relational tasks, which speaks to the empirical relevance of the conceptual framework.

Which Tasks Are More Important to Voters?

Figure 1 shows the average importance assigned to each of the tasks presented to the respondents (see Table 1) as well as the average importance of all functional (relational) tasks, adding the answers of each relevant task into an index. Importance is evaluated on a 0–10 scale, and the index is simply constructed by adding the scores for each of the five tasks and dividing by five. The figure shows that across all four countries, functional tasks (shown to the left) are, on average, rated as more important than relational tasks (shown to the right). Differences in index means vary between 1.61 (DK) and 0.58 (UK) and are statistically significant (p < 0.001). This provides support for H2a rather than H2b: across the four countries, voters tend to find functional tasks more important than relational tasks.

Figure 1. Average importance assigned to each of the representative tasks.

Note: To the left of the dotted vertical line are functional tasks. Relational tasks are to the right. Solid, horizontal black lines show the mean of the additive index of all functional (relational) tasks. Dashed, horizontal black lines show the 95 per cent confidence interval around the means of the additive indexes. Gray dots show means for each specific task, and the vertical lines within the dots show the 95 per cent confidence intervals for these task-specific means. N(DK) = 1,885; N(DE) = 1,919; N(UK) = 2,071; N(US) = 1,983. ‘Don’t know’ answers are excluded. Tasks can be assigned importance from 0: ‘Not important’ to 10: ‘Very important’.

Figure 1 also shows that voters find all tasks more important than unimportant, as means are above the scale midpoint (5) across all tasks and countries. This indicates that voters want politicians to attend to functional as well as relational tasks, though functional tasks are, on average, evaluated as more important. This demonstrates that the two types of tasks should not be considered as mutually exclusive. Rather, and in line with the argument behind H2a, voters value politicians maintaining contact with constituents in order to inform their exercise of power through functional tasks. In this sense, the tasks supplement each other. Yet time constraints push them to prioritize, and under such conditions voters assign relatively more importance to functional tasks.

Within the category of functional tasks, legislative scrutiny is generally assigned the highest importance, closely followed by attending parliamentary meetings. Basically, respondents want politicians to know and understand legislative proposals and be present to act on that knowledge on their behalf. Oversight and participating in negotiations with ministers and within or between parties is assigned lower importance. The UK in particular stands out, with voters assigning lower importance to negotiations, which may be due to the tradition of single-party majority governments, making cabinet negotiations most important for legislative initiatives.

Within the category of relational tasks, task-specific means vary more across countries. Denmark stands out, with voters assigning lower importance to all relational tasks than functional tasks. In Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States, voters assign more or the same importance to politicians’ staying in contact with their constituency to some of the functional tasks. This is most clearly the case in the United Kingdom. The electoral system is a possible likely explanation, as the single-member district systems in the United States and the United Kingdom support representative district linkages. The German mixed-member system also does so to some extent, while this linkage is weaker in the Danish multimember district system. Across all tasks, participation in public debates (UK and US) and being accessible to voters on social media (DK and DE) are assigned the lowest importance.

The patterns are remarkably similar across groups of respondents. The appendix shows means across gender (Figure C1), political interest (Figure C2), and political trust (Figure C3). While there are statistically significant differences across groups – most importantly, respondents with political interests assign more importance to all tasks compared to respondents without political interest – the rating is very similar across all groups: functional tasks are evaluated as more important than relational tasks. Therefore, like the open-ended answers, the rating question delivers more support for H2a (functional tasks more important than relational tasks) than H1a.

Figure 2 shows the results of the ranking questions asking respondents to distribute 100 per cent of politicians’ time across the ten presented tasks. If all tasks are found to be equally important, politicians should spend 10 per cent of their time on each task. The figure shows the mean share of time investment for each task as well as for additive indexes for functional and relational tasks. Across the four countries, voters, on average, rank functional tasks higher than relational tasks. Differences in index means vary between 5.91 (DK) and 1.45 (UK) percentage points and are statistically significant (p < 0.001). On average, Danish voters prefer politicians to spend 65 per cent of their time on functional tasks and 35 per cent on relational tasks, while UK voters prefer politicians to spend 55 per cent of their time on functional tasks and 45 per cent on relational tasks. This pattern supports H2a rather than H2b.

Figure 2. Average share of time assigned to each of the representative tasks. Per cent.

Note: To the left of the dotted vertical line are functional tasks. Relational tasks are to the right. Solid, horizontal black lines show the mean of the additive index for all functional (relational) tasks. Dashed, horizontal black lines show the 95 per cent confidence interval around the mean of the additive indexes. Gray dots show means for each specific task, and the vertical lines within the dots show the 95 per cent confidence intervals for these task-specific means. N(DK) = 1,885; N(DE) = 1,919; N(UK) = 2,071; N(US) = 2,071. ‘Don’t know’ answers are excluded. Tasks can be assigned values from 0: ‘No time’ to 100: ‘All the time’.

Echoing Figure 1, all tasks are assigned at least some share of the politicians’ time, suggesting that voters demand relational as well as functional task attendance. No tasks are assigned a fifth (20 per cent) of the time on average, which speaks to the fragmented and multitasking nature of politicians’ work. Similarly, constituency contact stands out as an important difference across countries, being ranked higher or as high as more of the functional tasks in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Germany. On average, UK voters prefer their politicians to spend 15 per cent of their time on maintaining contact with voters in the district.

Does Task Priority Influence Candidate Choice?

The final step is to move beyond task priority comparisons to test whether politicians’ task priority matters compared to other relevant politician traits. Figure 3 shows the average marginal component effects of the six experimental attributes, including the constraint on the combination of age (young) and work experience (short). Models are run for each country and data reshaped so that each candidate choice constitutes the unit of analysis. Each respondent therefore appears in the data four times. The models are estimated with standard errors clustered by respondents as:

Figure 3. Average marginal component effects on candidate choice.

Note: DK: 2,024 respondents, 16,192 observations. DE: 2,085 respondents, 16,680 observations. UK: 2,231 respondents, 17,848 observations. US: 2,185 respondents, 17,480 observations. AMCE: average marginal component effects.

Where:

![]() $U_{rta}$

represents the utility of candidate profile a for respondent r in task t.

$U_{rta}$

represents the utility of candidate profile a for respondent r in task t.

![]() $X_{rta,k}$

are indicator variables for levels of the unconstrained attributes (sex, ethnicity, education, and task).

$X_{rta,k}$

are indicator variables for levels of the unconstrained attributes (sex, ethnicity, education, and task).

![]() $\beta_{k}$

are the corresponding untility parameters for unconstrained attribute levels.

$\beta_{k}$

are the corresponding untility parameters for unconstrained attribute levels.

![]() $G_{rta,{\ell}}$

are indicator variables for levels of age.

$G_{rta,{\ell}}$

are indicator variables for levels of age.

![]() $\gamma_{\ell}$

are the utility parameters associated with age levels.

$\gamma_{\ell}$

are the utility parameters associated with age levels.

![]() $W_{rta,m}$

are indicator variables for levels of work experience.

$W_{rta,m}$

are indicator variables for levels of work experience.

![]() $\delta_{m}$

are the utility parameters associated with work experience levels.

$\delta_{m}$

are the utility parameters associated with work experience levels.

\varepsilon_{rta} is an idiosyncratic error term.

The average marginal component effects (AMCEs) are then estimated for each attribute-level combination and show the average change in the probability of selecting a candidate profile associated with a change in one attribute level, holding other attributes constant. The model accounts for the design constraint by estimating the effects of age and work experience over the restricted set of feasible attribute combinations.

The most important result from Figure 3 is the probability of selecting a candidate that states they prioritize functional tasks rather than stating they prioritize relational tasks. In Denmark, the probability increases by 18 percentage points, which is the largest effect detected across all attributes included in the experiment. In Germany, the probability increases by 7 percentage points, which is similar to the effects of work experience and ethnicity. In the United States and the United Kingdom, the probability increases (decreases) by 1 percentage point but is not statistically significant (p US = 0.1, p UK = 0.16). Hence, the smaller differences detected in the descriptive rating and ranking questions set in when task priority is evaluated next to other candidate traits. Overall, the test provides more support for H2b (voters prefer candidates prioritizing functional tasks over relational tasks) rather than H1b. However, unlike results supporting H2a, the results for H2b cannot be generalized across all political systems as UK and US voters are less persuaded by task priority compared to other factors such as the work experience or education of the candidate.

The experiment reproduces other findings regarding preferences for ethnic majority candidates (Portmann and Stojanović Reference Portmann and Stojanović2022) and female candidates (Schwarz and Cappock Reference Schwarz and Coppock2022). Also, candidates with more work experience prior to being elected are preferred over candidates with shorter experience, and candidates with longer education are prioritized over candidates with shorter education (except for Germany). In Germany and Denmark, politicians’ task priority is as or more important for candidate choice than the descriptive traits candidates bring with them into parliament.

Discussion and Conclusion

The results of this study suggest, first, that the conceptual framework of categorizing politicians’ multitude of tasks into two major categories of functional and relational tasks is helpful for studying voters’ preferences for representative tasks. More voters think about such tasks in open-ended questions, and all specified tasks are assigned importance in rating as well as ranking questions. Second, across measurements and countries, functional tasks tend to receive higher priority than relational tasks, offering more support to H2a than H1a. The pattern is consistent across all countries, but it is not the case that relational tasks are unappreciated. Rather, and in line with the argument behind H2a, voters care about politicians maintaining contact with voters to perform their functional tasks as legislators, and as such, the higher ranking of functional tasks speaks to the importance of the power being exercised from the representative relationship. This resonates with recent findings among US voters, showing that US voters believe that the government would run better if politicians (a) listened more to ordinary people and (b) did more research before deciding (Hibbing et al. Reference Hibbing, Theiss-Morse, Hibbing and Fortunato2023, 7). This study develops a framework for conceptualizing such findings into analytical tools helpful for connecting empirical studies to theories on political representation.

Beyond this overall cross-national pattern of preferences, the study also provides important insights into differences across countries. The higher importance assigned to functional tasks compared to relational tasks is most clearly expressed among Danish voters, followed by German voters, US voters, and finally UK voters, where the priority is least clear. The order of countries aligns with possible expectations given the institutional design of the political systems, informing us that voter preferences for political representation – even when challenged with similar global trends – are rooted in relatively stable institutions defining electoral connections and legislative functions. This is also reflected in the final analytical step where support of H2b – that voters prefer candidates emphasizing functional tasks – is more mixed. None of the cases provide support for the competing hypothesis, H2a. Only two of the cases – Denmark and Germany – provide support for H2b, whereas task priority seems to matter less than, for instance, work experience, education, or ethnicity in the United Kingdom and the United States. As such, the voter standard of representative task performance is uniform across the four countries, but the importance of it for evaluating specific politicians varies across cases.

The distinction between functional and relational tasks constitutes a conceptual innovation that directs attention towards individual-level representative acts rather than systemic output, and it holds promise as an analytical tool in future studies of political representation. Future studies may investigate in greater detail how preferences for representative task priorities vary among voters and potentially influence the type of representation they receive. Moreover, the framework can be applied to compare the preferences of actors beyond voters – such as party members, party leaders, or political advisors – thus illustrating how preferences may diverge and create conflicting demands on politicians. In addition, the framework can be employed to compare preferred and realized task priorities by extending the research design to include observed time investments of politicians. The framework therefore provides both a theoretically relevant and empirically useful starting point for examining differences in representative task preferences and activities across actors. This can be further developed by theorizing and empirically investigating the potential causes and consequences of such differences, thereby enriching both public and scholarly understanding of political representation in modern democracies.

As a final note, the distinction between functional and relational tasks is developed based on rich literatures on political representation and legislative politics. In contrast to the newest developments in representation theory emphasizing the complex multidimensionality of political representation (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge2003; Rehfeld Reference Rehfeld2006; Wolkenstein and Wratil Reference Wolkenstein and Wratil2021), this conceptualization suggests a simplification focusing on the representative activities. This simplification is relevant for understanding the practical act of political representation among elected representatives and helpful for designing empirical studies describing and explaining varying expectations and priorities of representative tasks across politicians and voters. However, such a reduction also comes with limitations, as it cannot address all relevant questions regarding political representation, such as who politicians should represent and what should come out of representation. The answers to the open-ended questions indicate that voters also care about these dimensions of representation, and the conjoint experiment reveals that additional standards of evaluation are important when voters consider their vote choice. Whether the share of spontaneous mentions of representative tasks (22–35 per cent), the differences in ratings and rankings, or the effects sizes should be considered large or small is difficult to determine with certainty. On the one hand, only the abstract notion of Focus is mentioned more often than tasks, and the difference and effect sizes reach conventional standards of statistical significance. On the other hand, most respondents do not spontaneously mention representative tasks and express preferences for a mix of relational and functional tasks. Nevertheless, the selective emphasis on representative activities rather than outcomes, focus, or personal traits is theoretically significant for understanding the dual roles of politicians as representatives and legislators, and empirically important for addressing the acute problem of politics under pressure, which may push politicians towards visible relational tasks at the expense of less visible functional tasks. This study suggests that such changes of task priorities are not in line with the wishes of voters who do emphasize the need for politicians to be representative legislators.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123425101245.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/50RWSI.

Acknowledgments

I am most grateful for the helpful and constructive comments and suggestions on this research from three anonymous reviewers, from Christopher Wratil, Fabio Wolkenstein, Troels Bøggild, Frederik Hjorth, Martin Bisgaard, Thomas Zittel, Stefanie Bailer, from participants at the Workshop on Citizens’ Views on Representation in Vienna, the Panel on Parliaments, Public Engagement and Connecting with Citizens at the ECPR General Conference in Thessaloniki, at the ODER kickoff Seminar in Copenhagen, and from colleagues in the Research Section on Political Behaviour and Institutions in Aarhus.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Aarhus University Research Foundation (grant number: AUFF-E-2022-9-11).

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical standards

The research was conducted in accordance with the protocols approved by Aarhus University Research Ethics Committee (approval number: BSS-2023-094).

Pre-registration

https://osf.io/mpcjf/?view_only=85d635dc2f734e949a6f0f570fa2317f.