13.1 Introduction

Information and education are central to climate justice. The people who are likely to be worst affected by climate change must have a good understanding of its causes and consequences. In this manifesto we also argue it is important that the knowledge and experiences of people at the sharp end of climate change be fully incorporated into the international understanding of this global challenge. In other words, climate justice requires a two-way education.

In 2020–2022, we conducted researched into how young people in Uganda are impacted by, and respond to, climate change in a collaboration between the youth NGO Restless Development, Makerere University and the University of Cambridge. To tackle these questions, we first needed to consider how climate change is perceived, understood and explained. We conducted this research just as young people’s demands for a stronger and more sincere response to climate change were hitting the headlines, in Uganda and internationally. Young Europeans’ critical voices cut through in the media (even if they were not always acted upon). Yet despite the swell of youth climate action in some of the world’s most climate-affected places, in many instances young people at the sharp end of climate change were, quite literally, cut out – Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate was cropped out of a photograph of young climate activists at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2020. As Nakate observed, ‘When it comes to the African continent, it is, of course, on the frontlines of the climate crisis. But it’s not on the front pages of the world’s newspapers’ (Lakhani, Reference Lakhani2022).

Many young African environmentalists, including Hilda Nakabuye and Vanessa Nakate from Uganda and Elizabeth Wathuti from neighbouring Kenya, are outspoken on climate change. Shoulder to shoulder with others in East Africa and beyond, they campaign and take practical actions on a plethora of climate change–related issues, including tree planting schemes, tackling plastic pollution and critiquing the new East African Crude Oil Pipeline. They have taken the campaign to tackle environmental damage and its social impacts to the streets, spoken at major international conferences, developed active social media campaigns and written books (Nakabuye, Nirere and Oladosu, Reference Nakabuye, Nirere, Oladosu, Henry, Rockström and Stern2020; Nakate, Reference Nakate2021). Between 2019 and 2020, more than 20,000 students demanded urgent climate action (Nakabuye, Nirere and Oladosu, Reference Nakabuye, Nirere, Oladosu, Henry, Rockström and Stern2020). Not only do these young women understand climate change but they also seek to raise awareness about how climate change is playing out in their own countries, while proactively working to respond.

Although many young people today are well informed about climate change, some people still haven’t even heard of climate change – despite experiencing it first hand. Furthermore, some are aware of climate change but are unsure of its causes or how to respond. This was a key finding from our British Academy research on ‘Peak Youth, Climate Change and the Role of Young People in Seizing Their Future’ (Barford et al., Reference Barford2021). Having identified this lack of knowledge and awareness about climate change, our team proposed a Social Science Impact Award project to the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council, entitled ‘Taking Climate Change to School’. Here we draw upon our learnings from both projects and discuss the implications for the design of educational offerings.

We first turn to the nature of climate change in Uganda – what young people are facing now and what they will face in the future. We then discuss young people’s knowledge and understanding of climate change. Next, we set out a series of primary school–focused activities that could be used to engage young people with climate change in an informative and hopefully empowering way. Finally, we discuss the need for a global sharing of knowledge, understanding and experiences.

13.2 Climate Change in Uganda

Back in the days, the season for rainfall was being estimated but as of now, people don’t know when rainfall will start or even end. So, people today are unaware compared to the past when people used to know when to start planting and when to harvest and wait for another season ahead.

Climate change is being acutely felt in Africa, even though historically and today, African countries contribute minimally to global warming. In Uganda, for example, recent years have seen hundreds of thousands of people newly displaced by weather-related events (Figure 13.1). These events include rapid-onset events such as lake and river flooding and landslides following heavy rains. Landslides are particularly problematic in mountainous areas, such as Bududa district, located in eastern Uganda on the slopes of Mount Elgon, and Kisoro district in south-western Uganda, on the Virunga Massif. Triggered by heavy rain swelling clay soils, landslides often destroy homes and agricultural land, kill people and animals and of course displace many others (Barford et al., Reference Barford2021; Mugeere, Barford and Magimbi, Reference Mugeere, Barford and Magimbi2021). Yet flooding is not confined to Uganda’s more remote volcanic mountains, with frequent inundations impacting towns and cities, including the capital, Kampala.

Figure 13.1 Recent climate change–related disruptions in Uganda.

Figure 13.1Long description

The map spans from the Democratic Republic of Congo on the left to Kenya on the right, and from Sudan in the north to Rwanda and Tanzania in the south. Uganda is shown in the centre. From bottom-left to upper-right of the map, the following points on the map are annotated as follows: Kasese: In 2021, homes, crops, livelihoods, and roads in 30 villages across Kasese district were damaged by flooding. Kiruhura: The Kiruhura and Isingiro districts in Uganda’s Western region have suffered frequent and severe droughts. Kampala: Every year, the rainy season causes flooding, pollution, loss of property, and loss of life. In 2019, flash floods displaced hundreds of people and caused eight deaths in Kampala. Lake Victoria: Lowering water levels in Lake Victoria and the Nile. Lake Kyoga: In 2021, rising water levels in Lake Kyoga forced hundreds of families to evacuate. Butaleja: Flooding in 2021 affected 15,000 families in the Butaleja district. Bududa: In 2010, a landslide in the Bududa district triggered by heavy rain killed roughly 365 people and displaced 8,000. In 2018, 850 people in the same region were displaced and 51 died in mudslides. Mbale: 63 percent of people surveyed in Mbale are impacted by both drought and erratic rainfall. Karamjoa sub-region: Flooding, drought, and other climate disruptions continue to worsen food insecurity in Karamoja.

Slower-onset events are also destructive. Droughts destroy crops and reduce food supply, which leads to food price rises. Extreme heat increases the likelihood of disease in livestock, meaning farmers spend more on medicines for their animals. While agriculture is especially exposed to the immediate impacts of a more extreme and less predictable climate, there are also impacts elsewhere in the Ugandan economy. One interviewee told us, ‘Carpentry has also been affected, because when there is severe drought, plants wither out so there is less timber.’ Another interviewee explained, ‘Activities like brewing gets to a standstill because the major input for making it [beer] is sorghum and maize, in which prices automatically hike if the harvest is poor, thus rendering us unemployed.’ Climate change–related events are already having serious consequences for people’s lives and livelihoods in Uganda. And the disruption and devastation are only likely to worsen.

Africa is especially susceptible to the impacts of climate change because the continent is dependent on rain-fed agriculture (where no rain means no water for plants to grow), has high levels of poverty and relies on infrastructure that is readily damaged by extreme weather. The situation is made worse still by limited access to climate change information in schools and for the general public. Right now, people’s lives are being disrupted by often unexplained changes, making it harder to know how to respond and how to prepare for the future. And this high exposure to the effects of climate change is affecting the continent’s economic development and exacerbating poverty.

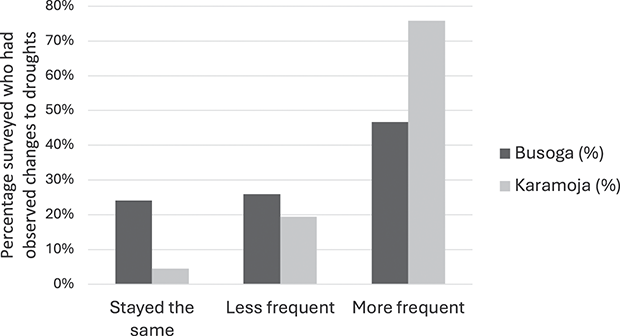

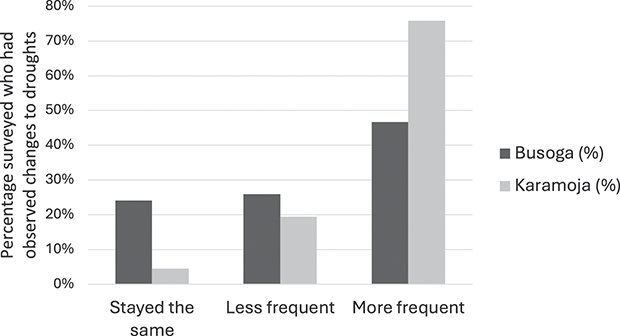

In our own research with young people, we asked about the changes they had observed. There was general agreement that temperatures had increased. One respondent explained, ‘For the past few years, there have been several environmental changes in my community. These include more dry and less wet seasons. The rainfall is very unreliable, with high temperatures and frequent drought. This is majorly brought about by increased cutting down of trees for firewood and charcoal burning.’ There was also agreement that rainfall had generally decreased, and rainfall patterns had become less predictable (Figure 13.2). Less rain and less predictability impact farming as most agriculture is rain fed. One interviewee reflected: ‘We cannot predict seasons these days like rainfall but I can see even if I didn’t study agriculture. But back in the day people could predict that this month it would rain and farmers were planting crops, but these days it’s impossible and seasons change. The seasons are no longer stable.’ This experience varies between regions, most (76 per cent) of young people in the semi-arid region of Karamoja noticed increases in droughts, compared to roughly half (47 per cent) in the lusher Busoga region in the Lake Victoria basin. Overall, young people described new weather patterns in terms of strong and dusty winds, prolonged droughts, flash-floods and changeability.

Figure 13.2 Young people’s observations of changes to droughts during the past five years, by region.

Figure 13.2Long description

The x-axis represents observed changes to droughts and has three categories: Stayed the same, Less frequent, and More frequent. The y-axis is labelled Percentage surveyed who had observed changes to droughts and ranges from 0 per cent to 80 per cent in increments of 10. The graph has two vertical bars: Busoga and Karamoja. The data are as follows: Busoga: (Stayed the same, 24 per cent), (Less frequent, 26 per cent), (More frequent, 47 per cent). Karamoja: (Stayed the same, 3 per cent), (Less frequent, 19 per cent), (More frequent, 65 per cent). All the values are approximate.

Alongside extreme weather events, changing seasonality was one of the biggest problems described. In the past, most of Uganda had two predictable planting seasons, one during March to May and the other September to December (Orlove et al., Reference Orlove2009), with specific crops planted each season. One of the young rural respondents recalled, ‘There has been a change in seasons due to these climate changes [such that] these days, people [are only able to] plant in one season. Back in the past, people knew that there were two seasons in a year, but [now], it’s one season in a year.’ In previous generations – before the invention of modern weather forecasts – indigenous knowledge was used to predict seasons. Farmers expected two planting seasons each year, knowing which crops to plant when and whether there might be a drought that year. Typically, fast-growing crops were planted in the March to May season to catch the first rainy period, and slower-growing plants would be planted for the September to December rains (Orlove et al., Reference Orlove2009). Before sophisticated technology to gauge rainfall, farmers would scrape soil away, or dig with hoes, to examine soil moisture to determine when it was sufficient for planting.

13.3 Young People’s Understandings of Climate Change

There is no [little] teaching about climate change in schools. This makes it hard for people to understand climate change. … However, despite the ignorance, everyone is familiar with the effects of climate change because they affect each and every one of us in various ways.

The environmental teaching in Uganda’s primary schools usually separates questions about the local environment from discussions of the global challenges. For instance, children study waste management as a local issue, while discussions of greenhouse gases and global warming tend to focus elsewhere in the world – for example the melting of Arctic ice. This approach is reminiscent of neo-colonial education, whereby geography classes neither resonate with the immediate local, social, physical, economic or environmental context, nor build relevant knowledge to help them survive and thrive as climate change worsens. Strikingly, the global dimension of this education does not highlight the international causes of climate change, overlooking the stark socio-political injustice of climate change.

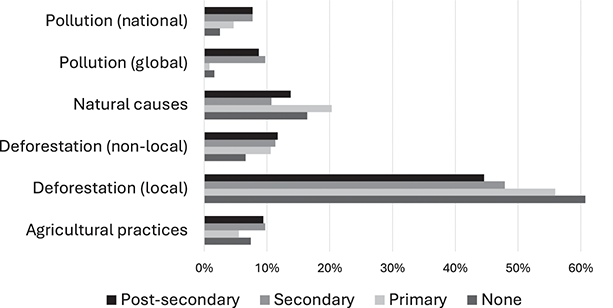

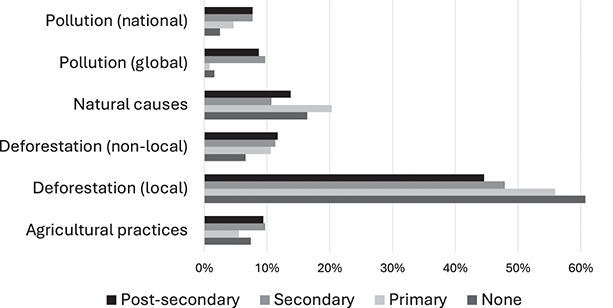

One of our team, a former science teacher in Uganda, first learned about the causes and consequences of climate change when he started teaching twelve years ago. He taught his pupils about the greenhouse effect, caused by gases trapping heat within the Earth’s atmosphere; causing the oceans, land and air to warm up. Yet this learning was global, lacking the indigenous examples which can help pupils apply a broader lesson to a local context. Instead, local changes have been rationalised as punishments from God, or the result of local activities such as people encroaching upon the forests, cutting down trees for charcoal production, mineral mining, building in the wetlands and Ugandan industrial pollution. In our research, we found that as education levels increase, so young people’s understanding of the drivers of climate change strengthens (Figure 13.3). Even so, the main cause of climate change is still identified as local deforestation, and only a tiny proportion of respondents saw global pollution as the leading cause. At primary school level and beyond, the puzzle of how climate-disrupted daily life in Africa is linked to global pollution is clearly not addressed.

Figure 13.3 Perceptions of the main causes of environmental change, by highest level of education.

Figure 13.3Long description

The x-axis ranges from 0 percent to 60 percent. The y-axis lists various environmental issues: Pollution (National), Pollution (Global), Natural causes, Deforestation (Non-Local), Deforestation (Local), and Agricultural practices. For each environmental issue, there are four horizontal bars, representing different levels of education, as indicated in the legend: Post-secondary (black), Secondary (dark grey), Primary (medium grey), and None (light grey). The approximate percentages for each category: Pollution (National): Post-secondary is 7 percent, Secondary is 6 percent, Primary is 5 percent, and None is 3 percent. Pollution (Global): Post-secondary is 10 percent, Secondary is 8 percent, Primary is 7 percent, and None is 4 percent. Natural causes: Post-secondary is 12 percent, Secondary is 15 percent, Primary is 18 percent, and None is 19 percent. Deforestation (Non-Local): Post-secondary is 12 percent, Secondary is 13 percent, Primary is 11 percent, and None is 9 percent. Deforestation (Local): Post-secondary is 44 percent, Secondary is 48 percent, Primary is 55 percent, and None is 58 percent. Agricultural practices: Post-secondary is 10 percent, Secondary is 8 percent, Primary is 7 percent, and None: 5 percent. All the values are approximate.

Education prepares people for climate change–related disasters, reduces negative impacts and supports faster recovery from climate shocks (Muttarak and Lutz, Reference Muttarak and Lutz2014). Many studies have shown how education can boost the ability to receive, decode, and understand information (e.g. Maponya, Mpandeli and Oduniyi, Reference Maponya, Mpandeli and Oduniyi2013, p. 278). Combined with specific knowledge about climate change, education equips people for an informed response. As contemporary climate change is anthropogenic, people need to be aware of their role in changing the environment for better or worse, as well as how to respond. Greater knowledge and understanding will support the roll out of adaptation and mitigation strategies. Molthan-Hill and colleagues (Reference Molthan-Hill2019, p. 2) state, ‘Educated people are more aware of the risks climate change poses and are better equipped to make informed decisions about responses at local, national and international scales.’

Young people with less education are also less likely to think climate change will worsen in the future. We found that among those who did not finish primary school, 72 per cent expect more environmental changes in the coming five years; rising to 92 per cent for those who completed post-secondary education. We also found that young people with more education are more likely to report being involved in mitigating and adapting to climate change. For example 17 per cent of those who did not complete primary education were involved in action to mitigate climate change, increasing to 47 per cent of those with post-secondary education. In terms of adaptation activities, there was a smaller range – 18 per cent of those without a full primary school education reporting involvement in adaptation activities, rising to 37 per cent of those with post-secondary education.

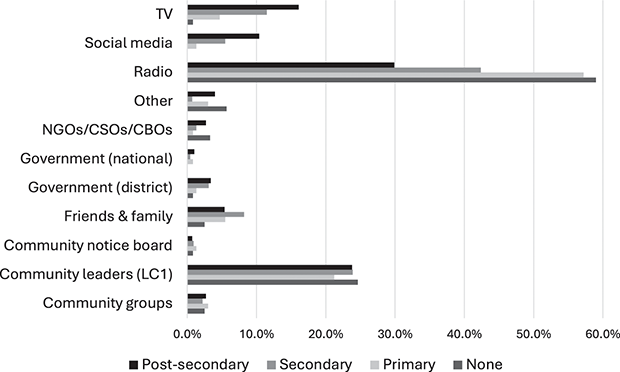

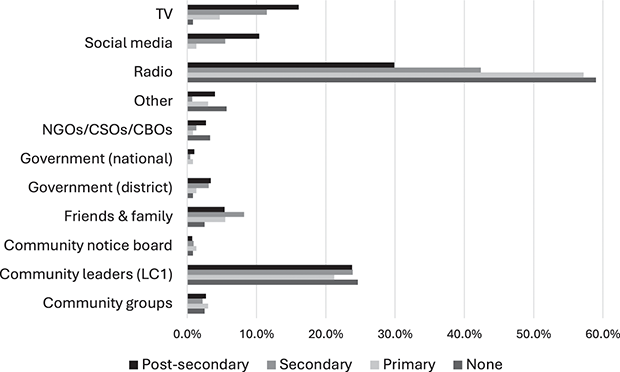

Alongside formal education, a plethora of information other sources about climate change are important – not least for those young people who leave education. We found that radios, followed by community leaders, were the most trusted sources of climate change information (Figure 13.4). For those with higher levels of education (likely a proxy for relative wealth and income), television and social media were important information sources. In addition to general information about the causes and consequences of climate change, it is important to have access to immediate and practical information about weather patterns and how best to respond to them. Among young people without primary education, 78.7 per cent did not know how to access information about weather patterns, compared to 52.3 per cent of respondents with post-secondary education.

Figure 13.4 Most trusted information source, by highest level of education. These are survey responses to the research question (with reference to climate change), In general, which source do you trust most when it comes to getting information about your community?

Figure 13.4Long description

The x-axis ranges from 0.0 percent to 60.0 percent. The y-axis lists various information sources: Television, Social media, Radio, Other, Non-Governmental Organizations or Civil Society Organizations or Community-Based Organizations, Government (National), Government (District), Friends and family, Community notice board, Community leaders (LC1), and Community groups. For each information source, there are four horizontal bars, representing different levels of education, as indicated in the legend: Post-secondary (black), Secondary (dark grey), Primary (medium grey), and None (light grey). The approximate percentages for each category are: Television: Post-secondary is 15 percent, Secondary is 17 percent, Primary is 13 percent, and None is 10 percent. Social media: Post-secondary is 8 percent, Secondary is 7 percent, Primary is 5 percent, and None is 3 percent. Radio: Post-secondary is 42 percent, Secondary is 47 percent, Primary is 55 percent, and None is 59 percent. Other: Post-secondary is 5 percent, Secondary is 6 percent, Primary is 4 percent, and None is 2 percent. Non-Governmental Organizations or Civil Society Organizations or Community-Based Organizations: Post-secondary is 3 percent, Secondary is 4 percent, Primary is 2 percent, and None is 1 percent. Government (National): Post-secondary is 2 percent, Secondary is 3 percent, Primary is 1 percent, and None is 1 percent. Government (District): Post-secondary is 4 percent, Secondary is 5 percent, Primary is 3 percent, and None is 2 percent. Friends and family: Post-secondary is 6 percent, Secondary is 8 percent, Primary is 5 percent, and None is 4 percent. Community notice board: Post-secondary is 1 percent, Secondary is 2 percent, Primary is 1 percent, and None is 0.5 percent. Community leaders (LC1): Post-secondary is 24 percent, Secondary is 25 percent, Primary is 22 percent, and None is 20 percent. Community groups: Post-secondary is 3 percent, Secondary is 4 percent, Primary is 2 percent, and None is 1 percent. All the values are approximate.

13.4 Taking Climate Change to School

Who is going to help me as an African child to understand how someone polluting over there will affect me here in Uganda?

In Uganda, schools offer education about the environment, as part of the National Curriculum. However, climate change has received little attention in Ugandan classrooms to date, in part because it has not been formalised in the curriculum. However, on 14 August 2021, President Yoweri Museveni passed the National Climate Change Act, stipulating that ‘the ministry responsible for education shall ensure that climate change education and research are integrated into the national curriculum’ (Republic of Uganda, 2021, Sec. 29). Thus, the learning landscape in Uganda should soon shift to systematically include climate change. Our own project was an effort to begin this engagement.

We chose to work in primary schools and teacher training colleges for several reasons. The Uganda Bureau of Statistics (2016) reports that 51 per cent of young people leave school earlyFootnote 2 (and girls are more likely to leave early than boys), and although children tend to leave school in order to start working, the School-to-Work Transition Survey found 71 per cent of the young people in work are undereducated for their roles. School-leaving data, combined with our own findings on climate change awareness, point to the importance of communicating climate information early in pupils’ education. Although young people tend to be better educated than their parents – as access to education has improved – since these data were collected, Ugandan children have faced new barriers to education, including the almost two-year-long closure of state schools due to COVID-19. This was one of the longest COVID-19 closures in the world, after which many pupils did not return to school. And many teachers left the profession as salaries were paused, turning instead to farming.

Our multi-partner research team responded by planning a six-month pilot project to ‘take climate change to school’. Our aims – which drew directly on the youth-led research we conducted in Busoga and Karamoja – were to design and share practical learning tools for primary-level climate change education, while also catalysing student interest in climate change and how to respond. Furthermore, our learnings were to be shared with experts developing climate change education for the National Curriculum for primary schools (Isiko, Reference Isiko2022). Our project focused on four primary schools and a teacher training college in the Busoga region. We planned extended, ongoing engagement with the schools during the six-month project, to make the lessons more meaningful and achieve deeper engagement. This began with introductory meetings followed by sensitisation meetings with the classes. Then came a series of tree planting sessions, several inter-school debates and the donation of climate change posters and ‘talking compounds’ to schools.

A talking compound is a sign with a message painted on it, which is displayed within the school grounds. In Uganda, talking compounds are widely used to communicate information to students on a range of topics (Figure 13.5). The messages are clear, concise and understandable to students. In our project, we used talking compounds to communicate environmental awareness messages to students, focusing environmental cleanliness, tree conservation and avoiding plastic pollution. For the schools we visited, these were the first climate change specific talking compounds they had seen.

Within the Busoga subregion, the project engaged 520 pupils from four primary schools – two rural and two urban. To have a longer-term impact on other schools, we also engaged sixty trainee teachers. These campaigns made students aware of the causes and consequences of climate change and encouraged young people to restore tree cover in their schools and communities to facilitate climate change mitigation (Figure 13.6). Pupils planted trees, and school environment clubs were responsible for the growth of the new saplings. Overall, more than 1,500 trees were planted, including fruit trees, eucalyptus and avocado – based on the preferences of the schools. Fruit trees were of particular interest, as they provide snacks for the children during the school day, and their usefulness means they are less likely to be cut down. Following these exercises, pupils are taking their newly acquired knowledge and skills home, to share with others. As a result, new environmental clubs have been established; elsewhere, existing clubs have been revived.

13.5 Conclusion

I have seen low or no rainfall due to serious deforestation or over cutting of trees, which delays rainfall formation, thus prolongs drought. … I am an eyewitness to some of these changes.

Young people in Uganda are facing the disruptions of climate change now. At the extreme, they are being displaced from their homes and fields and pushed to search for new livelihoods. Others find themselves facing unpredictable and rising costs; for some, their work is increasingly economically unviable. In short, young people in Uganda have immediate knowledge of what climate change means for their lives. Our data show that knowledge of climate change is heavily weighted towards direct experiences, especially for those with lower levels of education. This leaves young people only partially prepared for a future of worsening climate change induced disruptions.

Information and education are central to climate justice. We argue that two elements are particularly important for educators to consider:

1) Providing an understanding of climatic changes and why they are occurring. The people who experience the most climate disruption have a right to a true understanding of what is happening to their lives, and why. The why is extremely important given that the regions worst impacted by climate change tend not to be the places where most greenhouse gases were emitted.

2) Implementing a two-way, humanised climate education. Learning must be multidirectional, such that the knowledge and experiences of people at the sharp end of climate change are incorporated into the wider body of international understanding of this global challenge. This coheres with Paulo Friere’s concept of ‘conscientisation’ – whereby scientific evidence is integrated with lived experiences to humanise and globalise our understandings of climate change in a holistic way (Dorling and Barford, Reference Dorling and Barford2006). Education ‘encourage[s] people to change their attitudes and behaviour and helps them to make informed decisions’ (United Nations, 2022). So, this learning needs to be an integral part of educational offerings in Uganda and the UK alike, and indeed everywhere.

There is an urgent need to bring climate change into classrooms. In the meantime, ‘inaction at large is putting everything at risk’ (Nakabuye, Nirere and Oladosu, Reference Nakabuye, Nirere, Oladosu, Henry, Rockström and Stern2020).