Introduction

Political parties play a pivotal role in representative democracies, acting as conduits for the representation of citizens' preferences in policy‐making. In their pursuit of political power, parties – more or less strategically – craft policy platforms and campaigns to attract voters and secure electoral victory (Downs, Reference Downs1957). However, rather than designing these programmes from scratch, parties respond to existing and constantly evolving competitive environments, marked, for instance, by the rise of new cleavages (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006) and emergence of challengers such as green or radical right parties (de Vries & Hobolt, Reference Vries and Hobolt2012, Reference Vries and Hobolt2020).

Such changes in competition compel parties to engage with policy issues often located outside their ideological ‘comfort zones’ while remaining mindful of previous policy positions, alliances and long‐term commitments (Mair, Reference Mair2008). Given the far‐reaching implications of programmatic adaptations for party competition and policy output, it is not surprising that a wealth of research has been devoted to how parties navigate these challenges. This research has highlighted the roles of positional as well as saliency shifts (Carmines & Stimson, Reference Carmines and Stimson1993; Meguid, Reference Meguid2008) and found that parties face a constant choice between emphasizing their ‘core’ policy issues and broadening their appeal by focusing on ‘peripheral’ ones, or in other words ‘riding the wave’ (M. Wagner & Meyer, Reference Wagner and Meyer2014).

Although spatial models of party competition typically assume that parties possess information on voter preferences, relatively little is known about the specific impact of voter availability on the electoral market on these adaptations. This is not least due to the fact that previous studies have largely resorted to electoral performance as an approximation for parties' utility of narrowing or broadening their issue focus, thus leaving the strategic nature of engaging and disengaging policy approaches underexamined. To fill this void, this article investigates how the competitiveness of an election informs parties' decisions to engage in ‘peripheral’ issues or stick closely to their ‘core’ policy areas for voter mobilization.

Leveraging population data and party‐level data to answer this question, I argue that (a) the opportunity of parties to attract new voters, that is, the leaning of other parties' voters to them, (b) the degree of loyalty a party can hope for among its previous supporters and (c) the interaction between the two shapes a party's choice between emphasizing its ‘core’ policies or shifting attention to new issues in the hope of expanding its voter base. For instance, even though a rival party's supporters may express some availability to another party, the latter may only choose to seize its opportunity if it can expect to retain its previous voters.

To test these claims, I draw on voter survey data from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES, 2024) on the one hand and five rounds of the European Election Study (EES) on the other (Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Bartolini, Brug, Eijk, Franklin, Fuchs, Toka, Marsh and Thomassen2004, Reference Schmitt, Hobolt, Popa and Teperoglou2014, Reference Schmitt, Hobolt, Brug and Popa2019; van der Eijk et al., Reference Eijk, Franklin, Schoenbach, Schmitt, Semetko, Brug, Holmberg, Mannheimer, Marsh, Thomassen and Weßels1999; van Egmond et al., Reference Egmond, Brug, Hobolt, Franklin and Sapir2009), encompassing three decades of population data, which I use to determine parties' electoral opportunities and their voters' loyalty. To relate this information to indicators of parties' issue focus, obtained from the Manifesto Project (Lehmann et al., Reference Lehmann, Franzmann, Al‐Gaddooa, Burst, Ivanusch, Regel, Riethmüller, Volkens, Weßels and Zehnter2024), I harmonize party identifiers between the various data sources through a combination of fuzzy matching and manual coding, resulting in an integrated dataset.

Based on an operationalization of voter availability and loyalty adapted from A. Wagner (Reference Wagner2017), and a novel measure of parties' issue focus, I find that rising opportunities to mobilize new voters indeed coincide with increased attempts by parties to engage with peripheral policy issues outside their comfort zones. However, voter loyalty, or potential disloyalty, moderates this effect. When voter loyalty is high, parties tend to venture to expand their appeal by incorporating peripheral issues, assuming their core voter base is secure. In the absence of this loyalty, parties more strongly emphasize their ‘core’ policy issues.

These findings have substantial implications for party competition in competitive political systems, as they illuminate to what extent electoral utility informs political parties' programmatic choices, contributing to the scholarly debate on whether parties correctly perceive their electoral potential (e.g., Lichteblau et al., Reference Lichteblau, Giebler and Wagner2020). Furthermore, they shed light on the effectiveness of parties' attempts at adjusting their policy portfolios, highlighting for instance the limitations of ‘policy accommodation’ under conditions where rival party voters are firmly aligned and thus closed off to competition.

As challenger parties rise and elections become altogether more competitive (de Vries & Hobolt, Reference Vries and Hobolt2012, Reference Vries and Hobolt2020), demands for greater engagement with new issues and new competitors increase, however also engendering uncertainty about the appropriate form and degree of such engagement. Crucially, the success of policy adjustments not only depends on the attributes of the issue at stake (de Sio & Weber, Reference Sio and Weber2014) but also on the general receptiveness and loyalty of voters to parties' mobilization efforts. In this context, voter availability and potential disloyalty serve, respectively, as the ‘carrot’ and ‘stick’ in European party competition, directing and constraining parties' campaign decisions.

Spatial party competition and saliency theory

This section discusses existing approaches to comprehend how parties present themselves to the public, before turning to the roles played in this by electoral incentives, namely opportunities and voter loyalty.

As parties are at the core of democracy, a rich literature investigates how parties take and adapt their positions (Budge, Reference Budge1994; Merrill & Grofman, Reference Merrill and Grofman1999). Crucially, much of this literature draws on spatial theories of voting embedded in a rational choice framework. Accordingly, voters support a given party based on the perceived ‘proximity’ of their policy preferences to the party's programme. Parties therefore position themselves in the policy space so as to minimize the distance to their voters and maximize their electoral appeal (Downs, Reference Downs1957).Footnote 1

The literature on spatial party competition has since Downs (Reference Downs1957) undergone considerable refinement and has pointed to important mediating factors such as a party's strategic policy‐, office‐ and vote‐seeking behaviour (Müller & Strøm, Reference Müller and Strøm2010; Strøm, Reference Strøm1990), the dimensionality of the issue space (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Rovny & Edwards, Reference Rovny and Edwards2012) or other competitors' programmatic strategies (Meguid, Reference Meguid2008). Nevertheless, a plethora of research testifies to parties' strategic consideration of and responsiveness to public opinion and changes in their constituents' policy preferences (Abou‐Chadi et al., Reference Abou‐Chadi, Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2020; Romeijn, Reference Romeijn2020), past electoral performances (Abou‐Chadi, Reference Abou‐Chadi2016; Somer‐Topcu, Reference Somer‐Topcu2009) and opponents across the party spectrum (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Haupt and Stoll2009; Laver, Reference Laver2005). Parties, it seems, readily adapt their policy profiles as circumstances require.

However, while spatial models of party competition commonly assume parties to update their positions in the policy space relatively freely (Abou‐Chadi et al., Reference Abou‐Chadi, Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2020), the persistence of party positions along with the question of how parties reconcile their ideological identity with new or rival policy claims, has received relatively little attention. Although past electoral performances, government status or electoral competitiveness may incentivize parties to address new issues, the frequent adaptation of policy profiles risks undermining parties' ideological identity and credibility with voters (Downs, Reference Downs1957, p. 122). This means, party–voter linkages are inert, in that much like in the case of ‘brand ownership’, voters' impressions of parties' standpoints tend to perpetuate themselves (Budge & Farlie, Reference Budge and Farlie1983; Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996).

Saliency theory and the notion of ‘issue ownership’ therefore hold that parties should emphasize issues that are at the ‘core’ of their ideological identity and de‐emphasize other, ‘peripheral’ ones.Footnote 2 Parties' ideological cores and their backgrounds – such as conservatism, liberalism or socialism – are the distinguishing features and ideas behind party families (Beyme, Reference Beyme1985, Reference Beyme1994; Ware, Reference Ware1996) and directly inform how freely a party can move in a policy space. In the words of Mair and Mudde, the ideological core is ‘a belief system that goes right to the heart of a party's identity and (…) address[es] the question of what parties are’ (1998, p. 220). Often grounded in traditional cleavages or more recent changes in value patterns in Western societies (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1977), these ideological cores are crucial for a party's position in the ideological spectrum, connection to voters and role in government. This is why policy change tends to be incremental and why parties have been characterized as ‘conservative organizations’ (Dalton & McAllister, Reference Dalton and McAllister2015; Meyer, Reference Meyer2013).

Although parties regularly adapt to their environment, they are thus simultaneously constrained in their capacities to fundamentally alter their positions on issues that are of core concern to their voters (Budge, Reference Budge1994; Somer‐Topcu, Reference Somer‐Topcu2009). Where radical shifts do occur, this often enough threatens to divide parties internally (Bardi et al., Reference Bardi, Bartolini and Trechsel2014; Mair, Reference Mair2008) and risks voter alienation (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Haupt and Stoll2009; van Spanje, Reference Spanje2018). Policy adaptation can therefore be regarded as a ‘desperate deed’ of parties from a position of electoral weakness (Schumacher & van Kersbergen, Reference Schumacher and Kersbergen2016; van de Wardt, Reference Wardt2015). This is because of the fact that how well positional shifts will resonate with voters is inherently uncertain. Hence, especially where the core of a party family is concerned (Mair & Mudde, Reference Mair and Mudde1998), parties are more likely to opt for continuity over frequent re‐alignment with new demands.

Thus, the Downsian and Rokkanian approaches to party competition have often been regarded as mutually exclusive (however, see Koedam, Reference Koedam2022; Rovny, Reference Rovny2015). While one regards parties as actors updating their policy profile as electoral circumstances demand, the other stresses that parties do not draft election manifestos from scratch: ‘Parties do not simply present themselves de novo to the citizen at each election; they each have a history and so have the constellations of alternatives they present to the electorate’ (Lipset & Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967, p. 2). Consequently, parties often find themselves in a bind, unable to easily pivot away from established positions without risking the abandonment of issues critical to their identity and core supporters. This tension between adapting to new realities and maintaining ideological consistency creates a strategic dilemma, as parties need to navigate the risks of policy change against the potential costs of appearing unresponsive or static in the face of evolving voter preferences.

Few empirical studies exist that examine how political parties weigh the costs and benefits of these two pathways and how parties reconcile the need for engagement with ‘new’ demands on the one hand while holding onto ‘old’ demands and voter bases on the other – notwithstanding some noteworthy exceptions. Tavits (Reference Tavits2007) argues that the nature of the policy issue at stake and how strongly it is linked to a party's ideological roots determines how pragmatically and freely a party can alter its positions (see also Koedam, Reference Koedam2022). Habersack and Werner (Reference Habersack and Werner2023) demonstrate that political parties' ideological identity influences not only the extent of engagement but also the level of commitment in policy responses to competitors. Yet, an essential question remains underexplored in the extant literature: Do parties adopt a trial‐and‐error approach when reacting to changes in their competitive environment, or, with the professionalization of campaigns and greater access to polling data, are their choices informed by voter preferences?

Previous research has frequently relied on vote shifts and parties' electoral vulnerability as indirect measures to evaluate the appeal and likelihood of adopting more ‘engaging’ policy strategies. Abou‐Chadi (Reference Abou‐Chadi2016), for instance, demonstrates that the policy influence of niche parties is often contingent on the electoral performance history of mainstream parties. Likewise, Breyer (Reference Breyer2022) illustrates that electoral vulnerability can push parties toward adopting populist rhetoric. However, these studies do not fully explain the underlying mechanisms driving strategic policy choices. Specifically, they leave unresolved the question of how parties calculate the potential electoral returns of broadening versus narrowing their issue agendas. This gap highlights the need for a deeper understanding of how parties anticipate and evaluate the strategic benefits of engagement under varying electoral conditions.

The role of opportunities and voter loyalty

Extensive research explores the conditions under which mainstream actors respond to public opinion and changes in voter preferences (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Haupt and Stoll2009; Ezrow et al., Reference Ezrow, Vries, Steenbergen and Edwards2011; Romeijn, Reference Romeijn2020). Besides differences between small and large parties and incumbent and non‐incumbent parties (Klüver & Spoon, Reference Klüver and Spoon2016), extant empirical studies also highlight the role of electoral competition (Abou‐Chadi, Reference Abou‐Chadi2018; Abou‐Chadi & Orlowski, Reference Abou‐Chadi and Orlowski2016) and volatility (Dassonneville, Reference Dassonneville2018) in engendering higher levels of engagement with new demands, even at the cost of listening to their already established voter bases. Such changes in parties' mobilization strategies have been closely monitored and linked to more general shifts in party competition, namely the rise of challenger parties and simultaneous decline of the mainstream (de Vries & Hobolt, Reference Vries and Hobolt2020).Footnote 3

However, adapting comes at the expense of neglecting established voter groups and often risks dividing parties internally, as any innovation gives rise to the potential conflict between factions (Bardi et al., Reference Bardi, Bartolini and Trechsel2014; Mair, Reference Mair2008). This is because parties are limited in their programmatic decisions by their activists, their established voter bases and target voters (Basu, Reference Basu2020). Even though parties' internal organization and size (Basu, Reference Basu2020), incumbency status (van Heck, Reference Heck2018), and their ultimate political goals (Müller & Strøm, Reference Müller and Strøm2010) affect their decisions as to which groups to prioritize, all three play a significant role and decide upon parties' relative issue emphasis. These issue priorities, in turn, have far‐reaching electoral consequences (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Merill and Zur2024), further underscoring the necessity for parties to carefully tailor their campaign messages to their audience.

Parties are thus well advised to analyse their market opportunities, which implies taking electoral competitiveness into account. In other words, the effectiveness of responses to new demands rests on key voter‐side conditions such as information about the direction into which public opinion is moving (Stimson et al., Reference Stimson, Mackuen and Erikson1995), and electoral opportunities, or as I argue here, the ‘availability’ of other parties' voters on the electoral market (Bartolini & Mair, Reference Bartolini and Mair2007; A. Wagner, Reference Wagner2017). In a similar vein, Lewandowsky and Wagner (Reference Lewandowsky and Wagner2023) have argued that strategies devised to regain or siphon voters ‘lost’ to radical parties such as the Alternative for Germany (AfD) may well be a losing gamble, given that large parts of the AfD's voter segment are closed off to other parties and thus simply not available on the market.

The present article flips this argument on its head. Given the rise of polling data, use of focus groups and general campaign professionalization, which has spurred the rise of the ‘electoral‐professional party’ (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988), parties, much like business firms, tend to have a good grasp of the voter market and their opportunities for voter engagement (de Vries & Hobolt, Reference Vries and Hobolt2020). This implies that parties' decisions as to hold onto previous voters or diversify and innovate their product, hinge on the receptiveness of the electorate to such new offers. Independent of electoral conditions such as a ‘winning’ or ‘losing’ position or the wider context of an election, parties are thus incentivized to take the potential demand for broader voter engagement into account. And, in doing so, parties tend to more willingly adapt issue salience than specific positions they are associated with, which tend to be less malleable during election campaigns (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Merill and Zur2024, p. 807; Meyer & Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2019).

H1: The greater the opportunity to attract new voters, the more emphasis a party places on peripheral policy issues. (Opportunity)

Furthermore, parties that perceive their market opportunities correctly, will simultaneously be mindful of the risk of losing previous voters in their attempts to tap into new voter segments. This is because while ‘a new issue appeal may attract new electoral constituencies only gradually, established voters may be alienated quickly, plunging an established party into an electoral crisis’ (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt, Boix and Stokes2009, p. 539). Thus, there is a need for consistency in parties' policy focus, which however not only stems from their connection with the broader electorate but also from the increasingly important role activists on the street and the party base play in campaigning (Enos & Hersh, Reference Enos and Hersh2015; Moens, Reference Moens2022). This manifests itself, for instance, in the party leadership demonstrating greater programmatic openness than members further down the party hierarchy (Ennser‐Jedenastik, Haselmayer, Huber, & Fenz, Reference Ennser‐Jedenastik, Haselmayer, Huber and Fenz2022). Hence, I argue that parties will more likely broaden their focus to encompass peripheral issues for mobilization when they perceive their established voter base as sufficiently secure. Conversely, in a scenario of low voter loyalty and a high risk of voter defection, parties revert to core issues to solidify their traditional support base.

H2: The greater the loyalty of a party's existing voter base, the more emphasis a party places on peripheral policy issues. (Loyalty)

Lastly, I argue that only when both conditions of high electoral opportunities and receptiveness of new voter segments as well as sufficient voter loyalty are met, will parties have a rational incentive to broaden the focus of their campaigns. This is not to say that rational behaviour should never lead to erroneous positioning and always produce optimal outcomes (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988, p. 241). Yet, I argue that the combination of electoral incentives arising from electoral opportunities and voter loyalty renders strategic and data‐driven crafting of campaigns more likely. This aligns well with research regarding the impact of polling data and other sources of information on legislators' choices when representing their constituents' interests (Butler & Nickerson, Reference Butler and Nickerson2011) and the selection of which issues to pay attention to (Jones & Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005). It furthermore conforms to accounts of the campaign literature, specifically the ‘perceived voter model’, suggesting that modern political parties draw on a variety of data sources in tailoring their messages to their audience (Hersh, Reference Hersh2015). Naturally, resources matter in campaign professionalization. Yet, even in the absence of comprehensive data on voter preferences do parties possess information about their constituents, namely through personal ties and local campaign contacts (Giebler et al., Reference Giebler, Weßels and Wüst2014).

H3: Greater opportunities to attract new voters only coincide with a party's attention to peripheral policy issues when loyalty is high and the risk of voter alienation is low. (Opportunity

$\times$Loyalty)

$\times$Loyalty)

Consequently, even though a rival party's supporters may express some availability to another party, the latter may only choose to act upon this information if it perceives its own supporters as sufficiently loyal. This approach offers a perspective on parties' electoral strategies that speaks to other concepts such as the established ‘issue yield’ model (de Sio & Weber, Reference Sio and Weber2014; de Sio et al., Reference Sio, Angelis and Vincenzo2018). The issue yield model evaluates the electoral benefits of parties prioritizing certain issues over others based on the risk‐opportunity ratio at the issue level. While this approach is useful for assessing the potential electoral gains of focusing on specific topics, it is therefore inherently micro‐focused. Focusing instead on how parties balance their entire policy portfolio based on changes in voter preferences on the electoral market offers a distinct perspective that directly relates to scholarly debates surrounding the effectiveness of broad‐ and narrow‐appeal strategies (e.g., Bergman & Flatt, Reference Bergman and Flatt2021; M. Wagner & Meyer, Reference Wagner and Meyer2014).

Empirical strategy

For the empirical analysis, I combine party‐level information on the salience of parties' ideological cores and voter‐level data on party preferences (CSES: ‘party likability’; EES: ‘propensity to vote'). The resulting dataset covers 282 political parties across 162 parliamentary elections and 31 European countries. Importantly, the cases include EU members and non‐members and countries across various regions. To investigate the role of voter availability in shaping parties’ mobilization strategies, I treat individual parties as belonging to one out of several ideological families, which ensures comparability across cases. At the same time, this strategy enables me to determine parties' ideological origins, which I argue inform their campaign and mobilization strategies. That is, a party will adapt its emphasis on ‘core’ and ‘peripheral’ policy issues as electoral circumstances require.

Measuring core salience

To measure the dependent variable, namely the salience of ‘core’ policy issues in parties' election manifestos, I draw on the Manifesto Project (Lehmann et al., Reference Lehmann, Franzmann, Al‐Gaddooa, Burst, Ivanusch, Regel, Riethmüller, Volkens, Weßels and Zehnter2024), which makes extensive data on all electorally relevant parties in Europe from 1945 onwards available. Besides information on a party's ideological background and party family affiliation, it also provides content codes on a range of policy issues which I utilize to identify the salience of the core of individual party families over time and across countries. This measurement approach is embedded in saliency theory (Budge & Farlie, Reference Budge and Farlie1983) and assumes that the space that a policy issue occupies in a party's manifesto is indicative of the importance the party attaches to this issue. Though manifestos may not perfectly reflect parties' true policy positions, and alternative measures of core salience may thus diverge (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Bernardi, Ezrow, Gordon, Liu and Phillips2019), this is what renders them ideal for the present analysis given the focus on how parties present themselves and their policies to the public.

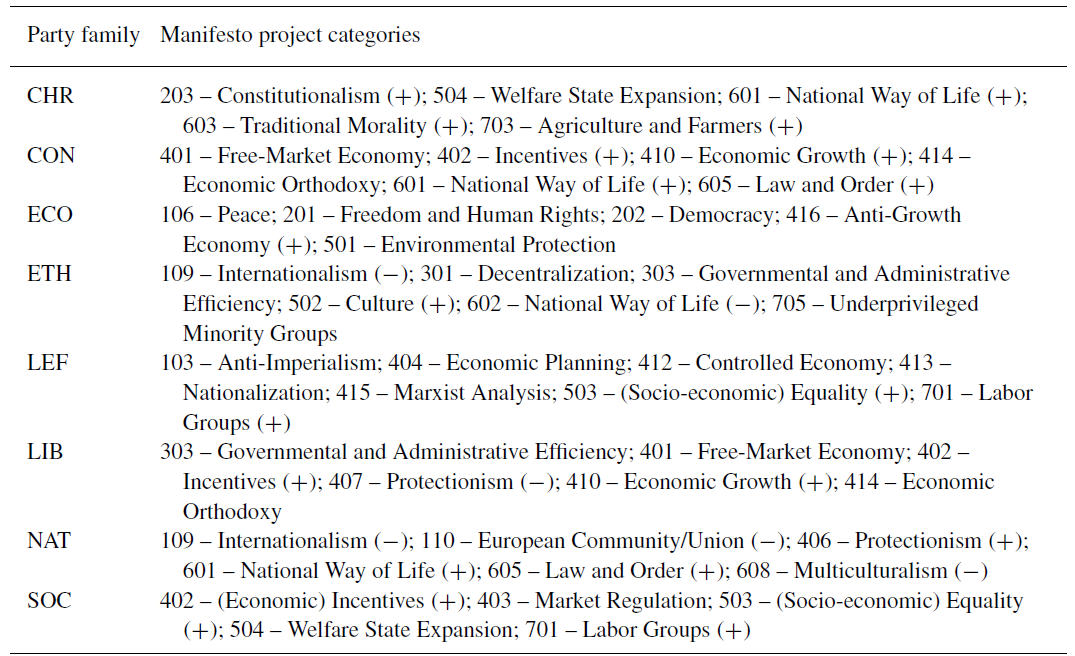

To operationalize what constitutes each party family's ideological core, I draw on established literature concerning party families in both Western and Central and Eastern Europe (Beyme, Reference Beyme1985, Reference Beyme1994; Freeden et al., Reference Freeden, Sargent and Stears2013; Hlous̆ek & Kopecek, Reference Hlous̆ek and Kopecek2016). These classifications of parties into ‘familles spirituelles’, while originally developed with an emphasis on Western European democracies (Beyme, Reference Beyme1985), have also effectively been extended to East‐Central and Eastern European party systems (Beyme, Reference Beyme1994; Lewis, Reference Lewis2002), suggesting a meaningful degree of comparability. Despite evident differences in political volatility and regional differences in political landscapes and voter‐party linkages (de la Cerda & Gunderson, Reference Cerda and Gunderson2023; Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1995), the concept of party families thus holds analytical value and generally highlights parties' distinct historical and sociological origins. Furthermore, as Hlous̆ek and Kopecek (Reference Hlous̆ek and Kopecek2016) conclude in their comprehensive analysis of party families in East‐Central Europe, ‘[we] can generally speak of a visible and significant convergence among the family identities of parties in the Eastern and Western European areas over the course of the last two decades’ (pp. 8–9).

The ideological cores that define each party family are thus essential for understanding how these parties present themselves to voters and for understanding the policies they pursue in government. Christian Democrats typically advocate for policies that combine state governance with Christian moral principles, aiming to shape public life around the ethical standards of Christianity (Pombeni, Reference Pombeni2013). Conservatives, by contrast, emphasize the maintenance of established social orders, advocating for minimal state intervention in the economy and a cautious approach to social reforms (O'Sullivan, Reference O'Sullivan, Freeden, Sargent and Stears2013). Green parties argue for the necessity of radical environmental protection measures alongside promoting social equity and pacifism, positioning ecological concerns at the centre of their political agenda (van Haute, Reference Haute2016, p. 313). Regionalist parties, though more prevalent in Western Europe, generally focus on defending the interests of specific regions or ethnic communities, pushing for greater autonomy and the preservation of local customs and economic interests (Hlous̆ek & Kopecek, Reference Hlous̆ek and Kopecek2016, p. 246). On the far left of the spectrum, parties demand comprehensive state involvement in the economy, aiming to redistribute wealth more equally and expand public services (Bozóki & Ishiyama, Reference Bozóki and Ishiyama2020). Classical liberal parties champion economic deregulation and advocate for free markets with minimal government intervention, maintaining that the role of the state should primarily be to protect individual liberties rather than prescribing or enforcing particular moral ideals (Close, Reference Close2019). Radical right parties are noted for their nativist and authoritarian ideology (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007) and their exclusionary rhetoric (Pytlas, Reference Pytlas2015, pp. 23–47). Lastly, Social Democrats seek economic policies that extend democratic freedoms into the social sphere, focusing on welfare state expansion, labour rights and promoting reforms that ensure fair and more equitable distribution of resources (Jackson, Reference Jackson2013).

Table 1 summarizes the policy codes utilized for each of the eight party families analysed, namely: Christian Democrats (CHR), Conservatives (CON), Greens (ECO), Ethnic and Regional Parties (ETH), Radical Left (LEF), Liberals (LIB), Radical Right (NAT), and Social Democrats (SOC).

Table 1. Operationalization of party families' ideological cores

Note:

![]() $\pm$ indicates directional policy codes and refers to a party's negative

$\pm$ indicates directional policy codes and refers to a party's negative

![]() $(-)$ and positive

$(-)$ and positive

![]() $(+)$ positions on the respective policy issue.

$(+)$ positions on the respective policy issue.

Drawing on these content codes, I derive a measure which yields, for each country–election–party triad, information on the relative share of quasi‐sentences attributed to ‘core’ policy issues. This indicator directly taps into the relative importance party families attach to core over peripheral issue areas across time and space. Importantly, the resulting indicator fundamentally differs from the notion of ‘issue ownership’, since it is based on the idea that party families share a set of ideological beliefs and policy priorities (Mair & Mudde, Reference Mair and Mudde1998), which are to some degree independent of the issues a party may choose to emphasize at a specific election and robust to public opinion shifts or the level of problem‐solving competency voters may assign to a given party at a given point in time. I calculate core salience as follows:

Here, it is critical to recognize that party families are not necessarily ideologically coherent, which particularly concerns left‐wing and liberal parties in contemporary European politics (de la Cerda & Gunderson, Reference Cerda and Gunderson2023). This heterogeneity manifests itself both temporally, as parties may undergo fundamental transformations over time as well as cross‐sectionally, where the core attributes of party families may vary depending on the national policy space. In cases of extreme ideological realignment, parties are assigned new identifiers in the Manifesto Project database. National differences in the issue space on the other hand have prompted scholars to determine parties' ideological identities on the basis of cluster analyses rather than theoretical considerations. However, as Mair and Mudde (Reference Mair and Mudde1998, p. 218) note, this method often results in classifications that reflect national contexts more so than they do party ideologies. Consequently, this study utilizes an operational definition based on the sociological roots, names and international affiliations of political parties as reflected in established party family classifications such as those provided by the Manifesto Project.

Measuring electoral incentives

The key independent variables are the electoral opportunity of a given party and the loyalty of a party's voter base, which I argue directly impact parties' mobilization strategies. This rests on the premise that parties position themselves in the policy space so as to maximize their appeal to voters (Downs, Reference Downs1957). Following this logic, parties will have an incentive to emphasize salient issues if the risk of losing previous voters is negligible and new voters are available on the market.

To measure both variables, I draw on ‘party likability scores’ (PLS) from voter survey data, measuring respondents' leaning towards a specific party on a scale from 0 (‘strongly dislike') to 10 (‘strongly like'), re‐scaled to range between 0 and 1. Additionally, I draw on ‘propensity to vote’ (PTV) scores as a substitute. Both of these types of questions have been shown to align with voting decisions while providing a more detailed assessment of voters’ preferences (A. Wagner & Krause, Reference Wagner and Krause2023, p. 220). Yet, it is worth noting that these two questions differ in their focus: PTV remains rather focused on electoral considerations, whereas PLS shifts focus to sympathy. This is relevant as voters may express sympathy for several parties yet might only ever consider voting for one or two out of them. Drawing on both variables and arriving at the same conclusions should therefore be an indication of empirical robustness.

Based on these types of survey questions, A. Wagner (Reference Wagner2017) conceives of the availability of voters at an election as the summed distances between the square root transformed preference scores for their preferred party on the one hand and all remaining parties on the other.Footnote 4 This measure yields high values of availability if the distances between two parties’ likability scores are minimal. In other words, if a voter supports A over B by a margin of 0.1 on a 0 to 1 scale, the decision of A

![]() $>$ B is highly dependent upon minor changes in the election campaign, whereas larger differences will be reflected in a lower availability of voters to the mobilization tactics of B. At the same time, the square root transformation ensures that overall higher likability scores lead to generally higher availability. To illustrate this, consider two cases, one in which a respondent favours A

$>$ B is highly dependent upon minor changes in the election campaign, whereas larger differences will be reflected in a lower availability of voters to the mobilization tactics of B. At the same time, the square root transformation ensures that overall higher likability scores lead to generally higher availability. To illustrate this, consider two cases, one in which a respondent favours A

![]() $>$ B by PLS = 0.9 to PLS = 0.8 and another, in which a respondent favours A

$>$ B by PLS = 0.9 to PLS = 0.8 and another, in which a respondent favours A

![]() $>$ B by PLS = 0.3 to PLS = 0.2. Though the margin of 0.1 is the same, the second respondent is altogether less available to either party, resulting in a slightly lower availability of 0.899 compared to 0.946.

$>$ B by PLS = 0.3 to PLS = 0.2. Though the margin of 0.1 is the same, the second respondent is altogether less available to either party, resulting in a slightly lower availability of 0.899 compared to 0.946.

To measure a party's electoral opportunity, I rely on a measure adapted from Lewandowsky and Wagner's (Reference Lewandowsky and Wagner2023) transformation of the availability metric above as an indicator of a party's potential to gain new voters.

This measure taps into the availability of voters to a party they did not vote for in order to gauge the latter's electoral opportunity. It is again a relational metric and juxtaposes the preference for the party a respondent in fact voted for (v) to the likability score for any other competing party (n). Taking both likability scores into account, it captures a respondent's leaning towards a new party given the strength of support for their preferred party. The measure can then be aggregated to obtain the average electoral opportunity of parties or party families at any point in time and space. For the present case, I aggregate the individual‐level metrics of opportunity and loyalty (see below) to the party‐level based on vote choice. This yields, for all political parties present in the data, a measure of their average electoral opportunity which is the average leaning of respondents to a given non‐voted for party in a specific election.

To recap, I argue in this article that the utility of emphasizing peripheral over core policy issues is a function of both ‘electoral opportunity’ and the ‘loyalty’ of a party's voter base. Hence, to measure the concept of ‘loyalty’, I adapt the above metric as follows:

where

![]() ${\rm PLS}_{v}$ again refers to the likability score for the party a respondent voted for, and

${\rm PLS}_{v}$ again refers to the likability score for the party a respondent voted for, and

![]() ${\rm PLS}_{n}$ denotes their preference for each remaining party. Loyalty is bounded between 0 and 1 and is in many ways the inverse of availability. Closer likabilities yield smaller values and therefore overall lower values of loyalty. The exponentiation ensures that altogether lower values will result in lower values of loyalty, albeit the difference between likability scores is more decisive. For example, if a voter supports A

${\rm PLS}_{n}$ denotes their preference for each remaining party. Loyalty is bounded between 0 and 1 and is in many ways the inverse of availability. Closer likabilities yield smaller values and therefore overall lower values of loyalty. The exponentiation ensures that altogether lower values will result in lower values of loyalty, albeit the difference between likability scores is more decisive. For example, if a voter supports A

![]() $>$ B with

$>$ B with

![]() ${\rm PLS}{v}$ = 0.9 to PLS = 0.8, loyalty for A is 0.17, whereas if they favour A

${\rm PLS}{v}$ = 0.9 to PLS = 0.8, loyalty for A is 0.17, whereas if they favour A

![]() $>$ B with

$>$ B with

![]() ${\rm PLS}{v}$ = 0.3 to PLS = 0.2, and hence by the same margin, loyalty is 0.05. Closely aligned likability scores signal that minor election changes can sway a voter's choice of one party over the other, while a

${\rm PLS}{v}$ = 0.3 to PLS = 0.2, and hence by the same margin, loyalty is 0.05. Closely aligned likability scores signal that minor election changes can sway a voter's choice of one party over the other, while a

![]() ${\rm PLS}_{v}$ of 0.9 versus a PLS of 0.1 would indicate a clear preference.Footnote 5

${\rm PLS}_{v}$ of 0.9 versus a PLS of 0.1 would indicate a clear preference.Footnote 5

Data and modelling approach

To ascertain the effect of ‘opportunity’ and ‘loyalty’ on parties' programmatic strategies, I draw on the CSES's Integrated Module Dataset (CSES 2024), which comprises survey data from across five different modules, from 1996 to 2021. Throughout these modules, respondents have consistently been asked what party they had supported at the last national election (‘party choice recall') and how much they liked or disliked each of the competing parties (‘party likability score'). From these two survey questions, I infer on respondents’ preferred party and construct the above measures of electoral ‘opportunity’ and ‘loyalty’.Footnote 6

Utilizing PLS and PTV data to determine respondents’ party preferences and, in this case, opportunity and loyalty, has several advantages (van der Eijk et al., Reference Eijk, Brug, Kroh and Franklin2006). First, party preferences measured along 0 to 10 scales are overall more conducive to traditional regression‐based modelling approaches. Second, likability scores and propensities draw a more accurate picture of party support less contaminated by other factors such as strategic voting or institutional settings. Third, party likability and propensity to vote nevertheless closely align with actual vote choice, whilst avoiding under‐reporting support for minor or radical parties.

As an additional assessment of the study's robustness, I utilize data from the EES and five different waves of data collection between 1999 and 2019 (Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Bartolini, Brug, Eijk, Franklin, Fuchs, Toka, Marsh and Thomassen2004, Reference Schmitt, Hobolt, Popa and Teperoglou2014, Reference Schmitt, Hobolt, Brug and Popa2019; van der Eijk et al., Reference Eijk, Franklin, Schoenbach, Schmitt, Semetko, Brug, Holmberg, Mannheimer, Marsh, Thomassen and Weßels1999; van Egmond et al., Reference Egmond, Brug, Hobolt, Franklin and Sapir2009). In contrast to other data sources, the EES is the only one to consistently provide PTV measures across countries. At the same time, the European context of the EES and the second‐order nature of European Parliament elections renders this analysis a critical test of the stated theoretical expectations as it can be assumed that party loyalty will overall be much lower than in the context of national elections and less likely to affect parties' strategies in the exact same way.Footnote 7

Since EES only provides inconsistent party codes, I manually coded information on parties in EES rounds to match the party IDs provided by Party Facts and the Manifesto Project in order to determine which party a respondent had supported at the last national election.Footnote 8 I then calculate voters' loyalty to their preferred party as well as openness or availability to third parties. Few time‐series cross‐sectional studies of parties' programmatic strategies exist, and even fewer include a perspective on voters and their availability in the electoral market. This study incorporates voter‐level information and provides a dataset combining party‐level and voter‐level data. This allows researchers to explore voter preferences and, thanks to the coherent party ID coding, connect this dataset with external sources such as the Manifesto Project, Chapel Hill Expert Survey, and Populism and Political Parties Expert Survey.

Finally, I model the effect of electoral opportunities and voter loyalty on parties' programmatic strategies in a stepwise approach, first focusing on the baseline effects of the two variables and then additionally looking at their interaction. Besides the main independent variables, the panel regression models contain a set of important controls such as ‘party family’ and consider the electoral performance at the party‐level, government status, party age, the length of the respective election manifestos, and the competitiveness of an election. For the control variables that pertain to parties' government status and information such as the competitiveness of elections, I additionally draw on data obtained from the V‐Party dataset (Lindberg et al., Reference Lindberg, Düpont, Higashijima, Kavasoglu, Marquardt, Bernhard, Döring, Hicken, Laebens, Medzihorsky, Neundorf, Reuter, Ruth‐Lovell, Weghorst, Wiesehomeier, Wright, Alizada, Bederke, Gastaldi, Grahn, Hindle, Ilchenko, Römer, Wilson, Pemstein and Seim2022).

Results

This section presents the descriptive results of measuring parties' emphasis on their core and their electoral incentives, meaning their opportunities and voter loyalty, before turning to the test of H1 to H3.

Variation in core salience and electoral dynamics

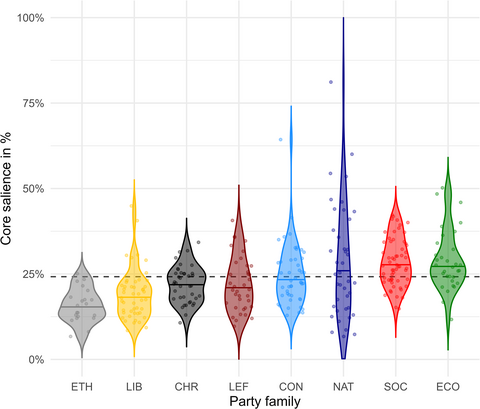

First, how much of their manifestos do parties attribute to their ideological cores? Figure 1 displays the distribution of core saliences by party family. At the bottom, manifestos devote minimal attention to core policies and focus more on peripheral issues, while at the top, parties' core issues feature more prominently.

Figure 1. Average core salience by party family.

Note: The dashed line denotes the average core salience across families, countries and elections. Depiction is based on data from the Manifesto Project (Lehmann et al., Reference Lehmann, Franzmann, Al‐Gaddooa, Burst, Ivanusch, Regel, Riethmüller, Volkens, Weßels and Zehnter2024) and operationalization in Table 1.

Two extreme cases include the UK Liberal Democrats' 2019 manifesto, which focused on Brexit and issues like tax rises to fund the health system, encroaching on Labour's territory, and the Austrian Greens' 2019 manifesto, which devoted about three‐quarters of its content to typical green policies, driven by the heightened salience of climate change protests. Overall, parties devote 24 per cent (SD 11 per cent) of their manifestos to core issues, which is considerable given their encyclopaedic and often very technical nature (Bischof & Senninger, Reference Bischof and Senninger2018, p. 474).

Strikingly, while there is variation both between and within party families, left‐right orientation does not strongly influence the extent to which parties discuss core policy issues.Footnote 9 Instead, catch‐all parties and those regularly in office are most likely to address peripheral issues; except for regionalist and leftist parties. The average core salience among incumbent parties is 19 per cent, compared to nearly 26 per cent among opposition parties. This is intuitive as catch‐all parties require broader thematic appeal and incumbents often address issues linked to their ministerial portfolios rather than their party ideology (see also Greene, Reference Greene2016; van Heck, Reference Heck2018).

In other words, when the prospects of government participation beckon, parties that otherwise occupy rather specific issue positions in the political spectrum become ‘moderate as necessary’ (Abou‐Chadi & Orlowski, Reference Abou‐Chadi and Orlowski2016). Bergman and Flatt (Reference Bergman and Flatt2021) find that such a broad‐appeal strategy can be especially beneficial for centre‐right parties. Although no causal inferences can be drawn from this depiction, it generally underscores the strategic relevance of choices between emphasizing core policy issues and ‘riding the wave’. Figures A.1 and A.2 in the Online Appendix support this finding as they illustrate that across Western and Eastern European party systems variation in core salience is high, yet the above‐discussed incumbency patterns remain consistent.Footnote 10 This raises an important question: What drives the considerable variation in core salience observed across parties and elections?

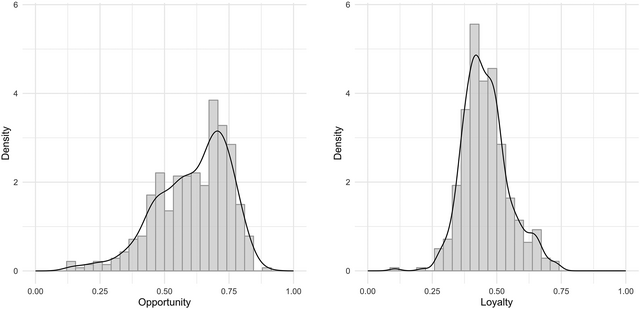

To explore this question, I draw on two main independent variables, namely a party's electoral opportunities and the loyalty of its previous supporters, both of which are bounded between 0 and 1. Figure 2 displays the density distributions of both variables. Taking the average across countries, election years and parties, electoral opportunities are approximately normally distributed albeit with somewhat of a skew towards greater opportunities. This means that as parties face competition – predominantly so within their ideological blocs (Bartolini & Mair, Reference Bartolini and Mair1990) – this engenders some degree of openness of voters to other competitors on the market. Only in rare cases are new voter groups entirely closed off to a given party.

Figure 2. Average distribution of electoral opportunities and voter loyalty.

Note: Mean values of opportunity and loyalty at the party level.

Loyalty, by comparison, features a slight skew towards values lower than 0.5, which indicates that a significant share of voters of a given party also expresses somewhat favourable opinions about at least one other party. While extreme cases of loyalty and disloyalty are observable on the individual level, for example, where a voter feels more inclined to a non‐voted for party than the one he or she actually supported, this is not the case on the aggregate level. That is, only few parties feature extremely high or low voter loyalty. Interestingly, the EES data distribution closely resembles that of the CSES data but with somewhat higher levels of loyalty, which may reflect key distinctions between the national and European contexts. Unlike national contests, European elections are often considered ‘second order’ and less strategic in nature. This may result in voting patterns that are more ideologically motivated and therefore lead to somewhat higher loyalty in these elections (see Figure A.6 in the Online Appendix).

The two variables are only moderately correlated at

![]() $r = 0.15$

$r = 0.15$

![]() $(p < 0.05)$ in the case of CSES and uncorrelated in the case of EES (

$(p < 0.05)$ in the case of CSES and uncorrelated in the case of EES (

![]() $r = 0.04$;

$r = 0.04$;

![]() $p = 0.3$), which generally confirms that the two measures are conceptually distinct (see Figures A.7 and A.8 in the Online Appendix).

$p = 0.3$), which generally confirms that the two measures are conceptually distinct (see Figures A.7 and A.8 in the Online Appendix).

Yet, do parties take these electoral circumstances into account? To recap, ample literature shows that parties undertake efforts to adapt to new competitive environments (Adams & Somer‐Topcu, Reference Adams and Somer‐Topcu2009; Laver, Reference Laver2005), though little is known about how strategic these attempts are. While some empirical studies highlight a general dragging effect of new issues and new challengers and speak of policy contagion (Meijers, Reference Meijers2017; Schumacher & van Kersbergen, Reference Schumacher and Kersbergen2016), I argue that how parties respond to competition crucially hinges on the expected receptiveness of voters on the market on the one hand and their own voters' loyalty on the other.

Opportunity, loyalty and parties' policy priorities

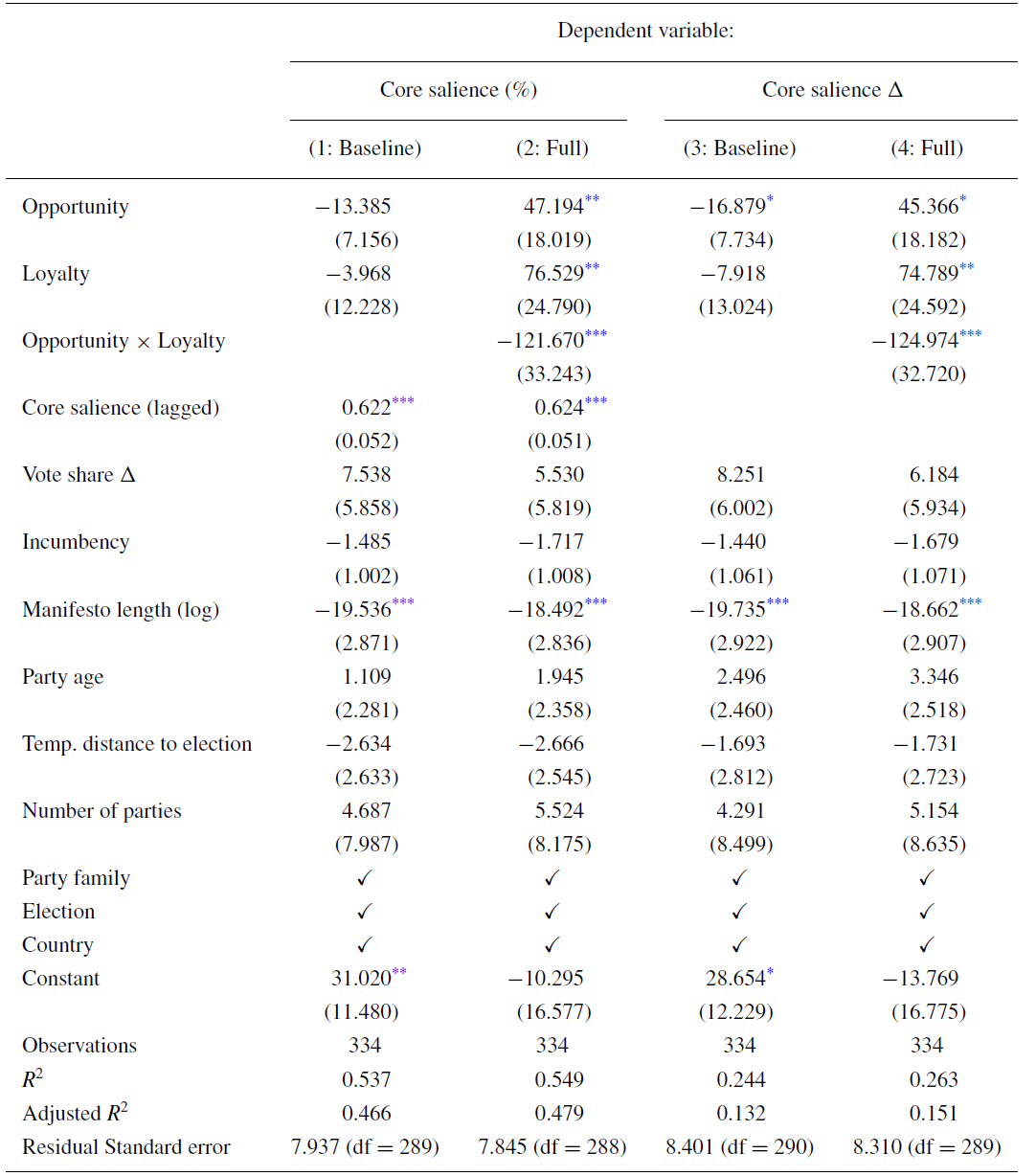

To ascertain to what extent parties respond to changes in the competitiveness of elections, I conduct a series of regression models, the results of which are reported in Table 2. All main models are based on CSES data, with the baseline models only regarding the individual effects of opportunities and voter loyalty and the full models additionally including the interaction term. Models 1 and 2 focus on core salience in percentage – and therefore contain the lagged dependent variable, accounting for the fact that past core salience at

![]() $t_{0}$ is positively correlated with present core salience at

$t_{0}$ is positively correlated with present core salience at

![]() $t_{1}$, in this case at

$t_{1}$, in this case at

![]() $r = 0.47$ (

$r = 0.47$ (

![]() $p < 0.001$). Models 3 and 4 look at changes in core salience between elections. Additionally, the models control for the temporal distance between the parliamentary election and the date of the interview.Footnote 11

$p < 0.001$). Models 3 and 4 look at changes in core salience between elections. Additionally, the models control for the temporal distance between the parliamentary election and the date of the interview.Footnote 11

Table 2. Panel regression models of core salience (change) on opportunity and loyalty

Note: Data: CSES/MARPOR; robust SE in parentheses.

*p

![]() $<\nobreakspace $0.05; **p

$<\nobreakspace $0.05; **p

![]() $<\nobreakspace $0.01; ***p

$<\nobreakspace $0.01; ***p

![]() $<\nobreakspace $0.001.

$<\nobreakspace $0.001.

This empirical strategy aims to tackle the issue of reversed causality, which arises when parties' campaign choices potentially influence voter preferences. For instance, Seeberg and Adams (Reference Seeberg and Adams2024) demonstrate that the policy issues parties highlight can shape the concerns of their own voters – though this influence does not extend to the broader electorate. Furthermore, particularly when pursuing office, parties may broaden their appeal, thereby attracting a voter base that is less homogeneous and more ‘disloyal’ than usual.Footnote 12 In contrast, pariah parties like the AfD in Germany's political system often narrow down their focus, in this case, on immigration, consolidating their support base.Footnote 13 Thus, while it is impossible to completely eliminate the issue of reversed causality, it is essential to control for a party's prior core salience at

![]() $t_{0}$ to model the shift in campaign focus that is likely attributable to voter‐level dynamics.

$t_{0}$ to model the shift in campaign focus that is likely attributable to voter‐level dynamics.

An alternative method would involve examining the change in core salience, measured in percentage points, from one election to the next. To complement the main models, I therefore also report on additional models that focus on change in core salience as their dependent variable; see Table 2. The results consistently demonstrate robustness against these changes in the model specification as the patterns between core salience (Models 1 and 2) and the change in core salience (Models 3 and 4) are remarkably similar.

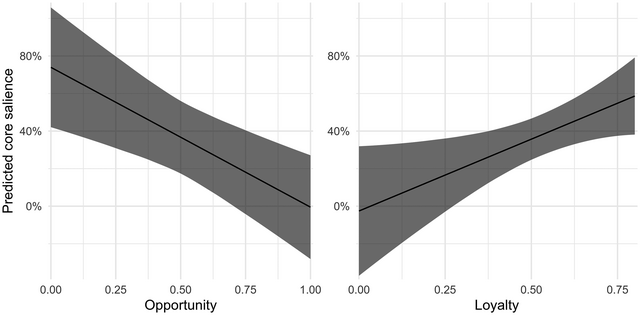

The regression results reveal that both loyalty and electoral opportunities are significantly linked to how political parties prioritize policy issues – whether emphasizing their core policy issues or engaging with peripheral ones. Increased opportunities seem to prompt parties to broaden their issue focus; though this effect is not consistent across models as it hinges notably on the interaction between opportunity and loyalty. Similarly, the impact of loyalty also hinges on the presence of the interaction term. While the potential to expand one's voter base (i.e., the ‘carrot') offers tangible benefits, the risk of voter disloyalty (i.e., the ‘stick') compels parties to seek their support elsewhere. Figure 3 illustrates these dynamics.

Figure 3. The individual effects of opportunity and loyalty on predicted core salience.

Note: Predicted core salience with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

[Correction added on 24 February 2025, after first online publication: Figure 3 has been updated in this version.]

Although the models generally indicate a stronger influence of loyalty, additional models based on the EES ascribe more importance to opportunities (see Table A.6 in the Online Appendix). Collectively, these findings affirm Hypothesis 1 but contradict Hypothesis 2, indicating that a secure voter base alone is insufficient to motivate political parties to pursue new voter groups. Greater voter loyalty might simply increase the perceived utility of focusing on the demands and preferences of already established voter bases, whereas disloyalty forces political parties to secure the support of new voter groups.

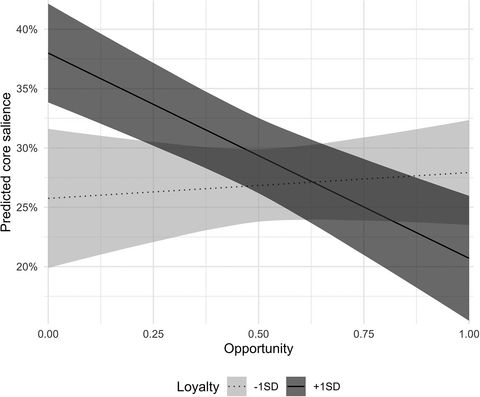

Strikingly, both effects hinge on the presence of the interaction term between opportunity and loyalty. Figure 4 visualizes the impact of the interaction on predicted core salience based on Model 2. The figure shows that greater opportunities to attract voters are associated with greater engagement in peripheral policy issues. However, voter loyalty crucially moderates this relationship. In accordance with Hypothesis 3, parties tend to more willingly approach potential new voters when the risk of alienating previous ones is comparatively low (i.e., dark grey confidence band). Conversely, where parties face meagre opportunities to tap new market segments, stronger voter loyalty is associated with an increased emphasis on core issues.

Figure 4. The effect of electoral incentives on predicted core salience.

Note: Predicted core salience with 95 per cent confidence intervals, interaction: high/low loyalty measured as

![]() $\pm$ 1 standard deviation.

$\pm$ 1 standard deviation.

Crucially, the overall model fit is high and the results are robust to various model specifications such as types of models fitted, lags and even the type of source data used to measure key variables, namely opportunity and loyalty. As Table A.6 in the Online Appendix shows, the overall patterns remain remarkably similar when drawing on EES data, albeit the effect sizes are somewhat smaller and loyalty appears as altogether less important. Finally, the results also hold for models that look at change in core salience rather than absolute levels, indicating that parties indeed adapt their issue attention in response to voter dynamics. For instance, the more voters are available on the market, the greater the engagement with peripheral issues (Model 2) but also the more pronounced the shift away from core issues and towards peripheral ones (Model 4). Again, similar patterns can be observed in the case of the EES models; see Table A.6.

Several additional findings concern the impact of electoral performance and other factors. Parties that perform poorly face on average greater incentives to innovate their campaign strategies and engage in new policy issues for voter mobilization at the next election, while parties may regard electoral victories as validation of their existing focus on core issues, leading them to maintain their current approach rather than pursuing significant changes. However, the effect of vote share change is non‐significant (Models 1–4). As might be expected, a party's government status decreases its focus on core policy issues; however, this effect is not significant either. Lastly, the longer the election manifesto, the higher the likelihood that at one point or another, it will touch upon peripheral policy issues rather than exclusively discuss core policy issues (see also on the matter of issue substitution vs. volume expansion: Ennser‐Jedenastik, Haselmayer, Huber, & Scharrer, Reference Ennser‐Jedenastik, Haselmayer, Huber and Scharrer2022).

Finally, it is noteworthy that the observed effects persist across the heterogeneity of countries included in the dataset, whether based on CSES or EES data. This suggests that the impact of opportunity and voter loyalty is robust and largely generalizable across national borders. However, the limited sample size constrains any further exploration of specific country‐level differences. While initial indications are that parties are particularly responsive to voter dynamics in Western European elections, further research is essential to determine the influence of contextual factors and differences in party systems, which might either amplify or weaken the connections between voters and parties. For example, previous studies have indicated that political volatility and prevalent corruption can often result in a disconnect between voter preferences and the policies parties promote and enact (Engler, Reference Engler2016; Piattoni, Reference Piattoni2001; Rohrschneider & Whitefield, Reference Rohrschneider and Whitefield2012). A more granular analysis could provide crucial insights into how these factors interact with parties’ political strategies.

Taken together, the results illuminate the association between parties’ electoral campaigns and voter availability in competitive political systems. While previous research has documented how parties innovate their campaigns in response to rising challengers (de Vries & Hobolt, Reference Vries and Hobolt2012, Reference Vries and Hobolt2020), this analysis emphasizes that both electoral opportunities and voter loyalty are equally essential in determining parties' policy priorities in Europe. This integrated approach sheds light on the conditions under which shifts in competition lead parties to adjust their agendas to meet voter demands. The findings indicate that parties tend to expand their appeal when the potential to attract new voter segments aligns with a secure base of existing supporters. Both the opportunity to grow voter support – the ‘carrot’ – and the imperative to retain loyalty – the ‘stick’ – equally shape the policy strategies parties pursue. Overall, this confirms the notion of political parties as fundamentally conservative organizations, favouring stability over frequent change and expansion (Koedam, Reference Koedam2022; van Heck, Reference Heck2018).

These findings are subject to three main caveats that warrant further consideration. First, the influence of country‐specific contextual factors on the relationship between political parties and voters merits greater attention in future research. Particularly, the presence of clientelist ties and varying levels of corruption may moderate how voter preferences inform parties' campaign strategies across different political systems. Despite this system‐level diversity, of course, the main effects observed in this study remain statistically significant.

Moreover, the salience and meaning of policy issues vary across national political landscapes, leading to differences among party families. Party families' core policy areas are neither constant across time and space nor does kinship entail a perfectly aligned understanding of ideological labels like ‘green’, ‘liberal’ or ‘radical right’. However, while starting levels of parties' core salience may vary, the fundamental dynamics by which electoral incentives shape party positions are likely consistent.

Second, parties' programmatic choices may induce shifts in opportunities and loyalties rather than the other way around. For example, if the radical‐right Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) chooses to broaden its focus in the hope of maximizing its vote share and entering government, such a move likely affects the sympathy for the FPÖ among other parties' voters, such as those of the centre‐right Austrian People's Party (ÖVP). It is essential to acknowledge that while parties may base such strategic decisions on substantial evidence anticipating electoral gains, the accuracy of their perceptions of their market shares and voter potentials remains debatable.

Third, the analysis assumes a rational basis underpinning both the voters' preferences and the parties' campaign strategies. Although there is a demonstrable link between electoral incentives and party behaviours as suggested by the data, further research is required to illuminate parties' and campaign coordinators' decision mechanisms in greater depth and detail.

Bearing these limitations in mind, the findings hold significant political implications. By examining the utility functions underlying strategies like ‘riding the wave’ or focusing on core policy issues, this research clarifies why political parties may, at times, hesitate to address new voter demands. This is because even where opportunities to reach new voters are available, parties may not broaden their appeal if they fear voter defection, for example, if a social democratic party anticipates that its supporters might switch allegiance to green or radical left parties. Moreover, the strong link between voter availability and parties' issue focus sheds new light on the challenges parties face in ‘regaining’ voters from competitors such as the Populist Radical Right (see Lewandowsky & Wagner, Reference Lewandowsky and Wagner2023). Such efforts often fail when the base of rival parties is closed off and unavailable to other political messages.

Conclusion

In elections, parties frequently encounter changing competitive environments, marked by the rise of new issues and the emergence of challengers in the electoral arena. Historically, parties have responded to these challenges in diverse ways, either by campaigning around well‐established themes closely tied to their ideological identity, or by directly addressing these new issues to broaden their electoral appeal and avoid losing influence.

Given the far‐reaching policy consequences inherent in these decisions – after all, campaign choices not only affect the outcomes of elections but also the policies to which parties commit themselves later in government – a substantial body of literature has investigated how political parties navigate the challenges of new issues and emerging competitors during elections. However, what has received insufficient attention in this literature is the influence of the voter side, particularly the availability of voters in the electoral market. While previous studies have primarily relied on changes in vote shares as a proxy, this article argues for a closer examination of both (a) the receptivity of new voters and (b) the loyalty of existing voters as essential to understanding what drives parties' strategic choices.

Empirically, this article makes use of voter‐level data from the CSES and the EES to measure parties' voter loyalty and electoral opportunities based on likability and propensity to vote scores and draws on the Manifesto Project to gauge the extent to which parties emphasize their own ‘core’ policy issues over ‘peripheral’ ones. Drawing on a measurement of electoral opportunities and voter loyalty adapted from A. Wagner (Reference Wagner2017), and a novel operationalization of the salience of parties' core policy issues, the analysis highlights that both opportunities and risks constrain and inform parties' campaign choices. However, their effect on parties' programmes is complex.

While rising opportunities to mobilize new voters indeed lead to more openness and engagement with peripheral policy issues (H1), the effect of voter loyalty runs counter to initial theoretical expectations: greater voter loyalty induces a stronger focus on core policy issues (H2). Yet, the results also indicate that the effect of beckoning opportunities is contingent on loyalty and parties are, on average, more likely to seize the opportunity to win over new voters when they perceive their established voter base as sufficiently loyal (H3). These findings are robust to several changes in model specifications, including exchanging the data source for the calculation of opportunity and loyalty.

The broader implications of this article's findings are that while beckoning support of new voters promises electoral returns, potential disloyalty of existing voters effectively poses a threat which restrains political parties in their campaigns and their engagement with new policy issues. The results therefore indirectly also contribute to the debate surrounding the effectiveness of policy accommodation and related strategies. Political parties whose attempts to tap new voter segments stand in disproportional relation to the electoral risks associated with such acts, may ultimately bear the costs of their disregard of the voter market.

Of course, changes in the competitive environment engender uncertainty. The rise of green and radical right challengers, in particular, has in recent decades driven a wedge into party systems, compelling established parties to adapt. Such disruptions increase the risk of misperceived electoral potentials and ill‐designed campaign strategies, with potentially vast electoral consequences (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Merill and Zur2024). Further research would therefore be well‐invested in studying parties' campaign choices and policy priorities from the angle of political parties and campaign coordinators themselves. This could lead to more effective strategies and enhance the stability and responsiveness of party systems.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their meticulous reading of and invaluable feedback on my manuscript. I would also like to extend my sincere gratitude to Franz Eder, Marco Fölsch, Sophia Hunger, Giovanna Invernizzi, Marcelo Jenny and Bartek Pytlas for their thoughtful advice and insightful comments on earlier versions of this article.

[Correction added on 3 December 2024, after first online publication: The Acknowledgements section has been updated in this version.]

Conflict of interest statement

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability statement

The databases used in this study can be accessed directly through the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES 2024), the European Election Studies (Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Bartolini, Brug, Eijk, Franklin, Fuchs, Toka, Marsh and Thomassen2004; Reference Schmitt, Hobolt, Popa and Teperoglou2014; Reference Schmitt, Hobolt, Brug and Popa2019; van der Eijk et al., Reference Eijk, Franklin, Schoenbach, Schmitt, Semetko, Brug, Holmberg, Mannheimer, Marsh, Thomassen and Weßels1999; van Egmond et al., Reference Egmond, Brug, Hobolt, Franklin and Sapir2009), and the Manifesto Project (Lehmann et al., Reference Lehmann, Franzmann, Al‐Gaddooa, Burst, Ivanusch, Regel, Riethmüller, Volkens, Weßels and Zehnter2024). The replication data files and the R Script to replicate all main results are available in the GitHub repository: https://github.com/FabianHabersack/carrots‐and‐sticks.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A.1: Number of observations across CSES rounds by country

Table A.2: Number of observations across EES rounds by country

Table A.3: Overview of key dataset variables based on CSES and MARPOR

Table A.4: Overview of key dataset variables based on EES and MARPOR

Figure A.1: Core percentage in party families' manifestos in Western Europe

Figure A.2: Core percentage in party families' manifestos in Eastern Europe

Figure A.3: Party families and their appetite for other families' cores relative to their own

Table A.5: Where ideological cores increase and decrease in salience

Figure A.4: Party families' top‐10 remainder policy categories and their average salience

Figure A.5: Average core salience by party family across regions

Figure A.6: Average distribution of electoral opportunities and voter loyalty (EES)

Figure A.7: Average correlation between opportunity and loyalty on party‐level (CSES)

Figure A.8: Average correlation between opportunity and loyalty on party‐level (EES)

Table A.6: Panel regression models based on European Election Studies

Figure A.9: The effect of electoral incentives on predicted core salience (EES)

Figure A.10: The effect of electoral incentives on change in core salience (EES)

±

±