The Wave and the Turbulence

Over the preceding pages we have seen how the culture of nationalism ran its course from a sudden onset in the decades around 1800 to its many manifestations in the artistic and intellectual fields and to its steady, soft influence in how people envisioned states and their sovereignties. We have seen how its long, tapering aftermath was capable of infusing popular leisuretime culture as this emerged after 1850, and capable also of generating strident war propaganda after 1870 and political discourse in 1914, surviving the upheavals of the twentieth century in the sanctuary of popular culture. The pattern reminds us of a wave, cresting and crashing with foaming violence in its onset, then levelling off but leaving turbulence in its wake. It is during such a period of renewed turbulence that I am finishing this book. A newly virulent nationalism has carried over from the realm of a popular culture still breathing the spirit of wartime propaganda into the field of domestic politics and international relations. At the same time, this ultra-political virulence is counterbalanced by a sentimental celebration of the home nation in terms of the long continuance of its historical traditions and its idyllic communitarianism. These tropes are so ambient and all-pervasive that it required a long hard look at them to see that they all originated in the decades around 1800: the war propaganda, the traditionalism and the idyllic sentimentalism, which celebrates the nation as a political extension of familial domesticity, tranquil, benign and utterly inoffensive, yet capable of rousing its citizens into righteous battle fury. To render visible this ambient, diffuse ideological force, I had to note its manifestations in diverse fields of knowledge production (linguistic history and philosophy, philology, ethnography and folklore, history writing, mythological studies) and in art forms in different media (textual, musical, visual, performative); and I also had to trace how these cultural manifestations could be encountered in societies all over Europe, despite their considerable differences as regards economy, class relations and governance.

After exploring this complex turmoil, we must ask ourselves if any patterns can be extrapolated by way of conclusion. What are the takeaways?

Shape-Shifting, Thin-Centred, Soft-Powered

Complexity and turbulence are in themselves features of nationalism, thrown into sharp relief as we traced its cultural manifestations – those would be far less multifarious if we traced the art forms inspired by communism or Fascism. This is partly because of the greater longevity of nationalism, but then again, that longevity is itself an interesting characteristic. We have seen how nationalism was a revolutionary force challenging the might of empires in Odessa and Belfast; how it had become a state-affirming, reactionary force by the time of Treitschke and Barrès; how the nation allowed border-straddling minorities (‘non-dominant ethnic groups’) to develop a unified political ideal, feeding into emancipationism and separatism among its various constituents; how it could inspire the progressive, utopian reformism around the Arts and Crafts movement as well as the intolerant authoritarianism of illiberal states in the 1920s and 2000s. Nationalism is, among the political ideologies, the ultimate shape-shifter. It is chimerical, almost, and weaves in and out of near-invisibility, ranging from a mere feeling to a fully fledged social movement.1

Throughout this book, we have traced the latent and salient states of nationalism: now anodyne, ‘unpolitical’, cultural; now strident, confrontational, ultra-political; sometimes a mere feel-good flavour, sometimes a resounding call to arms. In those shimmering alternations, the culture of nationalism has over the centuries spread across the European landmass and across cultural fields and media. In all that mobility, nationalism has adapted itself to different circumstances: whether the country was at peace or at war; whether an economy was agricultural and serf-based or rapidly industrializing; whether there was an advanced public sphere carried by print capitalism and a dense media distribution, or a society with low literacy-rates and largely lacking printed matter; whether the cultural centres gravitated to courts, monasteries or middle-class urban sociability; regardless of religion (Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox, Jewish, Muslim or secularist): across all those divides nationalism could adapt itself, survive by shape-shifts and mutations.

This adaptability appears to be typical of nationalism. For this reason, nationalism has been called ‘thin-centred’ – a characterization also, interestingly, applied to populism (on which more in what follows).2 Nationalism is, to be sure, an ideology properly speaking, in that it ‘consists of a body of tenets and prejudices constituting both a world-view and a value system’,3 but it seems capable of attaching itself to any other political doctrine on the political right or left. There are nationally tinged inflections not only in its siblings on the far right but also in the political middle ground – conservatism, (neo-)liberalism, Christian democracy – and even in social democracy, socialism and communism. The epithet ‘thin’ may carry a misleading connotation of weakness and inconsequence with it, but that is certainly not the point. I take the notion of ‘thinness’ to connote precisely this flexible adaptability. Nationalism is almost a meta-ideology, an inflection of other political doctrines, and something that can camouflage itself as being unpolitical, merely an extension of family values.

Thinness does not mean weakness. But it does mean that we cannot measure its importance in terms of power, the capacity to enforce social change despite opposition or inertia. Compared to the power of the state, certainly pre-1914, the power of nationalism is indeed weak – as weak as a fishbone lodged in the throat of a champion weightlifter. As we have seen, direct confrontations with the power of the state almost invariably panned out in favour of the state; but the repeated defeats of national movements eventually led to their political ascendancy in the century after 1918. Nationalism has exercised, over a long period of time, influence rather than raw power. It has vested the nation, against the oppression of tyrants and the perceived danger coming from foreigners, with a lasting reservoir of soft power. It has given the nation its charisma: that is to say, the power to inspire and to nudge political developments at moments of crisis and political dissolution.

This brings us back to the longevity of nationalism. Although my periodization of nationalism brands me a ‘modernist’, we must realize that this ‘modern’ history of nationalism by now spans fully a quarter of a millennium. Its sustained survival along such a long time-span reminds us of the endurance of culture, which displays the same adaptability and shape-shifting flexibility in the remediating presence of its canonical works, surfing in self-perpetuation from books to operas to streaming video. And this also leads me to conclude that we cannot understand nationalism unless we understand it historically, as a persistent influence in modern history.

The Presence of the Past

Scattered across the preceding pages are the many traces left by Romanticism. From glamourized queens and empresses to patriotic verse echoing in the minds of post-1945 politicians (even Boris Johnson could not stop himself from muttering Kipling’s ‘Mandalay’ while on a state visit to Myanmar), such traces may each individually have opened a single sight-line, an anecdotal anachronism, a trailing presence of the Then in the Now. Between them these individual threads form a web, something coherent and significant. Medieval epics and Romantic novels adapted to streaming video; anthems sung across the centuries with undiminished fervour; heavy metal bands recycling Germanic runes and sagas; Viktor Orbán’s turanism allowing him access to a post-communist Eurasian support network; Slavophilia in the policies of Vladimir Putin; juvenile-Romantic national-imperial chauvinism in the thought of conservative politicians such as John Major, Michael Gove and Jan-Peter Balkenende; modern cityscapes suffused with national-historicist street names and monuments.

When I set out to trace the typology, manifestations and repertoire of Romantic nationalism, I envisaged this initially as an almost antiquarian project, dealing with neo-Gothic buildings and bourgeois medievalism; I soon discovered that many of those neo-Gothic buildings were dedicated to modern, technological purposes and that the statues, paintings and historical novels of nineteenth-century vintage had obtained a fresh lease of life on banknotes and postage stamps and in films. While the erection of national monuments went through a noticeable dip in the twentieth century, the resurgence of that type of cultural production since 1990 was unmistakable (Figure 12.1). The ongoing recycling and availability of the Romantic-historicist nineteenth-century repertoire in new, mass-diffused and unobtrusive media seemed to span the mid-century dip and to connect the nationalist heydays of 1910 and 2020. It is then that I saw the ‘bump-dip-bump’ shape of those graphs as the trajectory of that metaphorical dolphin that visibly surfaces, dives into invisibility and elsewhere surfaces again.

The power of nationalism to condense time and to abolish historical distance is remarkable. The culture of nationalism has become the great enabler of anachronism. It creates short-cuts of memorability, recognizability and identification across decades and centuries of changing circumstances, adding up to the most potent anachronism of all: that of ‘timeless nations’ with their abiding national identities.4 National memories have an enormous power and presence in the here and now, and whoever would study nationalism only within the temporal parameters of a given social situation or a political moment would lose sight of that cardinally important potency. Nationalism can invoke memories and traditions spanning many centuries; it can pack all that temporality into a mighty ideological punch. Culture spans many centuries, but its national cultivation is concentrated in a handful of decades.

National Culture Transnationally Pursued

The cultural manifestations of nationalism take a similar form in highly dissimilar societies. Architecture, choral singing, the mural, amateur theatre and the decorative arts develop in parallels modes from Riga to Barcelona, Dublin to Iaşi. Academic scholars were aware of what was going on internationally in their field of expertise. Modern entrepreneurial formats such as the world fair developed standardized modes of showcasing the national individuality of the participants. The historical novel, academic history painting, the collecting of folktales were vogues enveloping all of Europe in their spread. Taken together, all this adds up to a strong counter-argument to the common wisdom that culture develops as a response to its surrounding societal conditions. The parallels are too numerous, too patently evident in various cultural fields, too diverse as to their societal backgrounds to be explained infrastructurally – certainly in the light of the many documented instances of communicative transfer. Culture has responded not just to ‘this society over here’ but also to ‘those other cultures over there’.

Nationalism is capable of spanning geographical distances. To illustrate a pattern that is visible all over this book, I recall only two instances: oral epic echoing back and forth between Ossianic Scotland and the Balkans, with ricochets reaching Goethe, Grimm, Mérimée and Pushkin; and a Parisian edition of Greek popular poetry by the philhellene Fauriel (1824) inspiring the Irish antiquarian Hardiman to publish Gaelic anti-English ballads in 1831, with an introduction stating that the relationship between London and Dublin is like that between Istanbul and Athens. We have repeatedly seen the culture of nationalism leapfrog across the European continent in two or three great bounds. Culturally, the European space is tightly and densely entangled. In the field of knowledge production, Europe was a single, homogeneous space: the Republic of Philology. The world of academic learning heaved with ‘Grimm Ripples’ (as Terry Gunnell has called them, Reference Gunnell2022). We have seen the visualizations of dense epistolary networks. In the fields of literature and the arts, we have encountered the remarkable paradox of ‘universal exceptionalism’: national authenticity was celebrated as being ‘different from the rest’ for each nation separately, but this was asserted by all nations in highly similar ways. The cultural thought of Herder, the historical novels of Scott, the philology and folktales of the Grimms, the rhapsodies of Liszt, the aesthetics of national-history painting, the agendas of language revivalism: these were taken up everywhere in Europe from Reykjavík to Tbilisi, Helsinki to Santiago de Compostela. Parallel movements occurred across huge cleavages. The cultures are all distinct, but their cultivation is a transnational process. Rien de plus international que le nationalisme.5

Cultural Entanglement, Political Localism

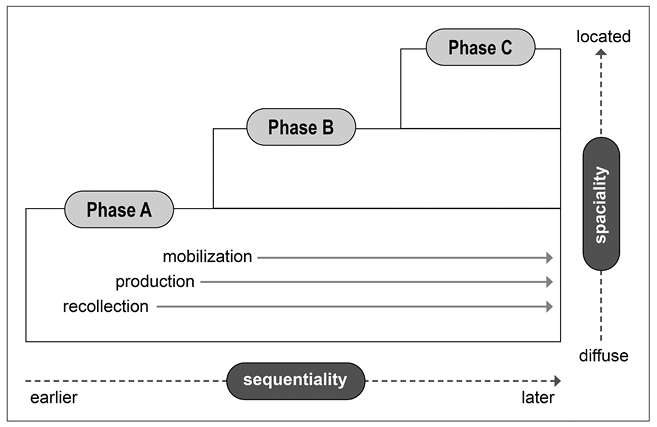

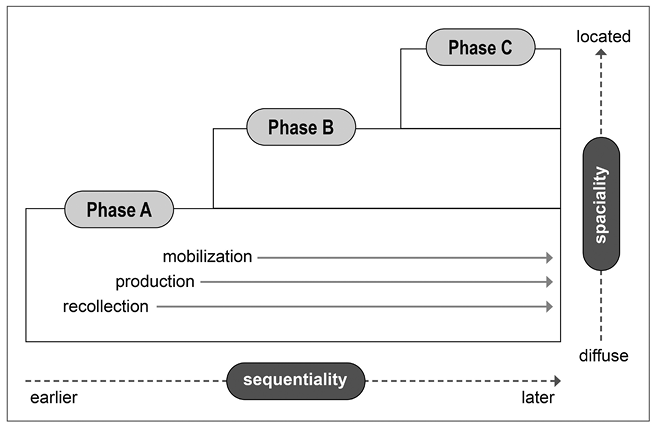

This transnational fluidity of cultural patterns stands in contrast to the more society- or state-specific workings of national movements as forms of activism. Activism characterizes what Miroslav Hroch has termed the ‘B’ and ‘C’ phases of national movements; cultural consciousness-raising commences in (but is not restricted to) his ‘A’ phase.6

The ‘cultivation of culture’ that I consider fundamental to national consciousness-raising (Figure I.3) takes shape as part of Hroch’s Phase A, in three successive and intensifying modes: ‘recollection’, ‘production’ and ‘propaganda’. These continue beyond phase A to inspire and accompany the social demands and the activist mobilization phases of national movements – and, I may add, in the nationalism of sovereign states. What is unmistakable in the successive chronological overlays of Hroch’s phases is a change in spatiality. The social and political action that characterizes phases B and C takes place in the context of a specific society or state. Cross-national patterns here became more anomalous, certainly after 1848. As national movements assert their social demands and mobilize their followers, they do so in a particular place in specific circumstances. By the time people start petitioning their governments or waging publicity campaigns, the transnational fluidity of everyone reading Herder or Walter Scott, or listening to Liszt becomes irrelevant.

And so, as the cultivation of culture moves across its stages of intensification, and as Hroch’s phase model moves from A to B to C, an initially diffuse condition of communicative transnationalism crystallizes into the specificity of localized action. This is represented schematically in Figure 13.1.

Figure 13.1 Phases of national movements between communicative diffusion and localized activism.

This suggests another type of historical dynamics: between diffusion and condensation. Culture diffuses, activism condenses. Ideas and cultural fashions can be spread far and wide by books, songs, music: in short, by cultural communication. This form of ‘broadcasting’ is untargeted, a bit like the sower sowing his seeds in the biblical parable: only a portion of the indiscriminately scattered seeds yields a harvest, while others land on fallow or rocky ground.7 Models for cultural organization and manifestation (choirs, sports associations, festivals, Matica book clubs) likewise proliferate, but in a slightly different mode, which I have termed ‘reticulation’: imitatively spreading from city to city across the European map, as often as not across cultural boundaries, with local associations often linking up in federative associational networks. But the social and political mobilization that is inspired by this, such as the Slavic Congress in 1848, or the choral mass demonstrations in the Baltic countries, or Patrick Pearse proclaiming Irish independence from Dublin’s General Post Office: each of these is concentrated in a specific society, subject to its social and political conditions, often occurring in urban spaces. And in turn those activist moments can resonate far and wide, like the Galician Irmandades da Fala emulating the Irish Gaelic League in 1916, or Catalan activists setting up a human chain across the land in 2013 in imitation of the Baltic one of 1989.8

Transnational and Intimate: Scalarity and Affect

The wide span of these processes across space and time has been contrasted repeatedly with their immediacy in the here and now. But where is here? The culture of nationalism can be sensed and registered at many levels. It can affect a far-flung aggregate such as the self-defining ‘Slavs’ of 1848; or a country (the Irish programme of de-Anglicization by way of Gaelic sports and language revivalism), a region (the Flemish-speaking part of Belgium) or a city (Valencia asserting its stature alongside Barcelona).9 How exactly the units are spaced on that scale is moot. Are Wales and Brittany regions or countries? And when the Slavs gathered at their 1848 Congress, was that event affecting their entire community, or the city of Prague, or both at the same time? And if the latter, what effect did that have on the communitarian tensions between Prague’s German and Czech inhabitants? In factoring in such scalar complexities, this book has moved beyond a comparative approach to a transnational one. The comparative method has traditionally tended to juxtapose nations as modular country-by-country units. A transnational approach has allowed me to take the multiscalarity of nesting levels of aggregation into account. A city or region is part of a country but may itself be culturally hybrid (Anglo-Irish Dublin, Spanish–Catalan Barcelona, German–Czech Prague, Danish–German Schleswig). Differences run within as well as between the aggregates we compare, and the smaller aggregation level may be as complex as the larger, outer ones. Even the single individual may go through changes, or feel conflicted, as to the culture(s) they feel they belong to, or the name they should call themselves (Douglas Hyde or Dubhghlas de h-Íde, Friedrich Tirsch or Miroslav Tyrš). And those scalar levels and juxtaposed units overlap and interpenetrate, as in the case when nationally-minded philologists from different regions and countries met in Vienna at the Stammtisch of Jernej (or Bartholomäus) Kopitar; or when Christian Bunsen and Max Müller, Britain-based Germans, drew Dwarkanath Tagore, as a ‘fellow-Aryan’, into the ambit of a Welsh eisteddfod.

And so nationality is also a yo-yo, bobbing up and down the gradations of scalarity from large, far-flung associations (Aryans, Slavs, Celts, Germans) to small, local ones. Languages can be lumped together or split into particularist component variants. Valencian revivalism sometimes distinguishes its culture, together with the Catalan Renaixença, against Madrid; and sometimes distinguishes its local culture from its Catalan-hegemonic neighbour Barcelona.Footnote *

Amidst all that scalar fluidity, a heuristic end-point in the here and now is reached within the bosom of the individual affected emotionally by the culture of nationalism. Its emotive power comes to the fore prominently in the performative arts as they affected ‘embodied communities’ and participants – lyrical-poetic declamation, oratory, music. The ecstatic upward gaze encountered in so many instances is a form of secular religion, or rather a response to the nation’s charisma. That selfsame gaze had traditionally, in baroque religious art, been a sign of mystical fervour; it was now transplanted to the realm of national culture. To recall this book’s opening pages, and the powerful affect inspired by communally singing ‘Die Wacht am Rhein’ or ‘La Marseillaise’: nationalism, before it becomes an explicit political doctrine or ideology, is experienced as a private feeling; and even at the heart of the fully fledged ideology, that emotive state remains quite, quite powerful.10

Charisma, Disenchantment, Narcissism

There is a sliding slope from seeing the nation as a sovereign subject rationally pursuing its goals towards seeing it as the bearer of a transcendent world-historical mission. This ‘charismatic supercharging of the idea of nationality’11 was noticeable in the German ‘conservative revolution’ and as such formed part of that country’s ‘culture of defeat’ post-1918, in which bitterness and rancour were rife and people turned to the extraordinary appeal of charismatic leaders. That appeal is by no means specific to Weimar Germany, nor even to countries in defeat (although it has been pointed out that charismatic leadership is better suited to ‘states of exception’ than to routine governance12) – but there is, I argue, a meaningful correlation between the new political force of charisma and the decline of the two other forms of Weberian authority, dynastic and institutional, a decline accelerated as a result of the Great War. In addition, we have seen a general, long-term alternation between the Weberian notion of disenchantment (as a concomitant of the modernizing process) and the Romantic appeal of the nation, which I have linked to Romanticism’s poetics of re-enchantment. I have drawn attention to the renewed presence, in European culture, of a thematics of disenchantment as the power of Romanticism, and the Romantic re-enchantment of the world, declines, and with the rise of realism and naturalism. Romanticism and lyricism were rejected scornfully by the post-1918 avant-garde (subsisting only in downmarket comfort reading); but the charisma of the nation, and the derived charisma of the new type of leaders who spoke for the nation, remained a political force that became increasingly important in the 1920s. People whom the events of 1914–1918 had robbed of many a fond illusion bought into the enthusiasm of a new nationalism under charismatic leadership, fervently attended huge rallies and dedicated themselves to the cause of their nationality. The nation’s charisma became, in other words, a palliative to the disenchantment of twentieth-century modernity. It could be that it still functions as such. The nation, as a tranquil, serene, communitarian essence transcending the unpredictable sound and fury of a conflicted world, uniting the people across society and uniting the generations across history, is a powerful antidote to a modern sense of disorientation and deregulation. It gives modern people in a secular world something to believe in, something to cherish and to adore – the political equivalent of football fans devoted to their home teams. Hence the upward-gazing ecstasies that the nation can inspire. This may explain how nationalism, as the power of the nation’s charisma, has survived across revolutions and regime changes from empires to restored monarchies to republics and nation-states to dictatorships and back; it is still thriving, in its ethnopopulist form, in a globalized neoliberal world order.

There is a downside to this. Whether the nation is a sovereign subject rationally pursuing its goals or the bearer of a transcendent world-historical mission, it may become a moral validator of the goals the state chooses to pursue. As the state’s national interest is underwritten by a transcendent, charismatic nation, it obtains a specious moral-categorical justification: ‘My country, right or wrong’. Yes, that facile phrase was memorably exploded by G. K. Chesteron, who sarcastically likened it to ‘My mother, drunk or sober’. But Chesteron’s ridicule had a serious undertone. The question of whether one’s mother takes to drink, or whether one’s country is in the right or in the wrong, should be a matter of grave concern, not of ‘gay indifference’.13

The state cannot do whatever it finds expedient on the grounds that it does so on behalf of a cherished nation. What Chesterton is driving is it that the jingoistic cult of ‘My country, right or wrong’ suspends the higher criteria of morality and lawfulness in a national narcissism. We have noted how a similar narcissism in Germany (Dahn’s phrase that ‘a nation’s highest good is its rightful entitlement’) was denounced by Emile Durkheim as a form of anomie: the idea that the will to realize the nation’s needs constitutes a rightful justification, surpassing international laws and treaties. In other words: the more fervently we buy into the nation’s charisma, the more prone we are to unilateralism and reckless self-righteousness. ‘Anomie’ was coined by Durkheim from the Greek word for ‘lawlessness’, a replacement of rules and regulations by willpower and self-interest.14 The applicability of that principle to post-1989 manifestations of ruthless, self-righteous nationalism is obvious, both within the state and in the field of international relations. Narcissism is a possible side effect of the nation’s charisma.

Small Government, Big Flags

While this book does not set out to analyse contemporary politics, it does furnish an explanatory background – by no means an all-explaining one, but relevant nonetheless. To understand the ethnopopulist turn that has dominated politics in the first quarter of the twenty-first century, we must see its reliance on the culture of nationalism not as an incidental proclivity that happens to affect populist politicians, like a case of bad breath, but as an intrinsic core element of their political repertoire and discourse. Nationalism is not an occasional feature of populism; populism is the new carrier of nationalism.

Seen in this light, populism is not a political novelty emerging in a realigning social order; it is the latest manifestation of a shape-shifting phenomenon with long, deep historical roots, and this book has demonstrated how deep and widely-ramified those roots run. Anti-immigrant xenophobia amidst the resurgent hard right in European politics is just not a symptom of generic bigotry; Donald Trump’s desire to annex Canada or Greenland is not just a mark of his flippant eccentricity; these things are, very pointedly, motivated by the nationalist commitment to expand the nation’s territory, to keep it unsullied by foreign admixture, to maintain the body politic’s cultural line of descent. The heaving gestures of populist rhetoric draw on a centuries-old, ingrained discourse. The mobilizing power of Donald Trump on 6 January 2021 was not mere rancorous rabble-rousing but involved – could not possibly have done without – the ubiquitous inspirational invocation of nationalist symbols and a patriotism so fervent and yet so ambient as to be unquestionable and almost unnoticeable in the sound and fury of the events. The rune-tattooed Capitol-storming ‘QAnon Shaman’ (Figure 5.3) was filmed marching along, Braveheart-style, with shouts of ‘Freedom!’ Footage shows that he, too, like Rouget de Lisle, Ossian, Liszt and the Serbian guslar (Figures 1.3, 3.1, 5.1 and 9.1), had his eyes fervently turned heavenwards and must have felt his commitment intensely, privately, while tapping into into global internet memes to obtain his neopagan tattoo designs. Those were not just decorative anecdotal ornaments or incidental whimsies: they are the internalized insignia, bodily indentured into his skin, of an ethnicist challenge to the political order. The meme is the message.

Populism insistently and consistently draws on the congenial rhetoric and symbols of nationalism. The proliferation of national flags in the public appearances of populist leaders is an indicator. This is all the more remarkable since many of those politicians (Silvio Berlusconi, Donald Trump, British Conservatives of recent vintage) are avowedly neoliberal and in favour of ‘small government’. As the regulatory and fiscal powers of the state are being steadily whittled away, the symbolic emblems of the state’s nationality are being multiplied and magnified. As the government is made small, the nation is ‘Made Great Again’.15 In the neoliberal view of the nation-state, the ‘nation’ and the ‘state’ are in direct inverse proportionality, like the opposite ends of a see-saw. The ‘state’ is being diminished and relinquished to market forces, the ‘nation’ with its symbols and pomp and emotive appeal to our loyalty is bombastically enlarged. Illiberal and authoritarian states are equally dedicated to the inflation of the symbols of nationhood; and so the nation is proclaimed fervently everywhere, by every sort of state, while everywhere its democracy is deregulated and ceding to autocracy or ethnocracy.

Stating that ethnopopulism draws its water from the well of nationalism raises the question of how it differs from nationalism’s earlier iterations.16 One important novelty is the shift from experts (Michael Gove: ‘the people of this country have had enough of experts’17) to influencers. In public opinion, a radical epistemic intransigence has taken hold, denying evidence-based, institutionally scrutinized authority and relying, instead, on the swarm knowledge of the internet. The importance of social media in political debate marks a deep paradigm shift in societal relations, fundamentally altering the workings of the public sphere and the production of public opinion. It is difficult, and still too early in the current century’s erratic developments, to tell how these new media affect, specifically, the culture of nationalism. First impressions suggest that in the lapidary brevity and ephemeral transience of social media, the repertoire of that culture is becoming more formulaic, selective and abbreviated, like headlines or the ten-second digests of football matches showing only the goals (including slow-motion replays) and the cheers.

The historical dynamics I have summarized so far tend to be of a bi-stable nature, oscillating between latency and salience, diffusion and condensation, wider and narrower scalarities or temporalities. If these phase changes are triggered by anything specific, it would be the ‘culture of defeat’. To the cases analysed by Schivelbusch (Reference Schivelbusch2004) we can add the various instances of loss of empire: for example Spain in 1898 and the defeats of Austria, Turkey and Russia in 1866, 1878 and 1904 as experienced in those empires’ heartlands; and in that context also, perhaps, the evaporation of the nation-state’s sovereignty in a globalizing world. The Dutch intellectual Menno ter Braak, when discussing National Socialism in the 1937, spoke of an ‘ideology of rancour’ (rancuneleer, Braak Reference Braak1937); mutatis mutandis, defeats appear to have something to do with the politics of rancour, resentment, grievance.18

What seems steadily unidirectional in all this is the shift from restricted to unrestricted cultural production: the culture of nationalism appears to have relied increasingly, over the past century and a half, on popular rather than ‘high’ culture. That slow, steady shift has been driven by the emergence of new mass-diffusion media and seems to have gone into overdrive now that communication, and what we may call ‘recreational opinioneering’, are produced in the cloud by self-replicating viral memes, by influencers and possibly even by bots and troll-farms. What is also unidirectional is the tendency for the nation-state to gravitate from democracy to ethnocracy; we saw it happen in the 1920s and 1930s and it is happening again in these decades. The cry of ‘Freedom!’ intoned by Mel ‘Braveheart’ Gibson and the QAnon Shaman has shifted away from democratic to populist usage; it had been originally raised by the insurrectionists of 1789, 1830 and 1848 as the nation tried to wrest sovereignty from haughty monarchs. After 1848, nationalism has increasingly allied itself with the political right, and since the days of George W. Bush and Boris Johnson, the cry of ‘Freedom!’ has been appropriated by the far right. It is now used in an exclusivist and exclusionary sense: freedom is claimed only, exclusively, for one’s own nation, to the exclusion of foreigners and minorities. This shift from democratic solidarity towards populist intolerance, the gravitational slide from democracy to ethnocracy, seems unidirectional and appears to occur in tandem with the shift towards ‘unrestricted’ cultural production.

That may be a glum note on which to end this book; but the book has studied the culture of nationalism not to celebrate it but to diagnose it – in the Greek root sense of that word: to ‘see through it’. Once we see how it works, what its appeal is and what its foibles are, we can perhaps also work out how, while opposing its intellectual complacency, its political narcissism and its bigoted intolerance, we can salvage its message of communitarianism, social cohesion and civic solidarity.