Populists often mobilize popular support for their policy choices and institutional reforms by claiming to advance a type of democracy that will be truly responsive to the will of the majority (Benasaglio Berlucchi and Kellam Reference Benasaglio Berlucchi and Kellam2023; Bessen Reference Bessen2024). Most of the time, however, what they are doing is the exact opposite—subverting democracy rather than enhancing it (Carrión Reference Carrión2022; Medzihorsky and Lindberg Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2023; Ruth-Lovell and Grahn Reference Ruth-Lovell and Grahn2022; Weyland Reference Weyland2024). Voters, then, should decide whether to support the incumbent’s undemocratic behavior and reforms. Voters are expected to stand up for democracy (Mazepus and Toshkov Reference Mazepus and Toshkov2021), but they may also trust the incumbent to advance their interests (Singer Reference Singer2018). Under which conditions would voters tolerate the gradual dismantling of democracy advanced by populist incumbents?

This article addresses this question by analyzing public attitudes toward democratic subversion under the presidency of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) (2018–2024) in Mexico. AMLO was a widely popular president who consistently invoked “the People” and “a true democracy” to legitimize his political transformation.Footnote 1 He is also a populist leader who triggered Mexico’s ongoing episode of autocratization (Aguiar Aguilar et al. Reference Aguiar Aguilar, Cornejo and Monsiváis Carrillo2025). To assess the influence of AMLO’s populism on citizens’ attitudes toward democracy, this article examines voters’ support for executive-led transgressions of democratic norms and institutions. There is mounting evidence that ordinary citizens are willing to trade democracy for political representation or political profit (e.g., Bessen Reference Bessen2024; Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Smith, Moseley and Layton2022; Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Kingzette et al. Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Barry Ryan2021; Singer Reference Singer2018). In Mexico, recent findings also indicate that attitudes toward democracy (Castro Cornejo and Langston Reference Castro Cornejo and Langston2024), electoral fraud (Castro Cornejo Reference Castro Cornejo2024), and electoral management institutions and integrity (Monsiváis-Carrillo Reference Monsiváis-Carrillo2023) have already been conditioned by AMLO’s populist rhetoric, whose attacks on crucial democratic institutions have successfully degraded those institutions in citizens’ opinion (Cella et al. Reference Cella, Çinar, Stokes and Uribe2025).

The theoretical argument is that populist presidents frame the subversion of democratic institutions as democratic improvements on behalf of the people. Populist presidents thus compel voters to choose between the establishment, often depicted as “elitist” or “corrupt,” and what they call “democracy.” When the populist incumbent is a dominant and widely acclaimed figure, voters’ attitudes toward the political regime are thus expected to be influenced by the incumbent’s populist rhetoric. Therefore, voters who approve of the populist president might trust their claims to be transforming democracy for the sake of the people and should adopt permissive attitudes toward the president’s undemocratic behavior. On this basis, citizens who approve of López Obrador’s job performance are expected to “reward populism”—they will endorse the subversion of democratic institutions promoted by the Mexican president on behalf of his “transformation for the well-being of the people.” Using cross-sectional survey data to test these expectations, the results show that López Obrador’s supporters are more likely to be convinced that Mexico is a democracy. At the same time, they are more inclined to allow the president to disobey the rule of law, curtail the opposition’s rights, or override the checks and balances.

These findings contribute to the study of attitudes toward democratic subversion in political scenarios where populist incumbents are advancing autocratization while encouraging voters to support antiestablishment political change. This research sheds light on the attitudinal roots of democratic backsliding under AMLO’s “Fourth Transformation.” It shows that when the populist president is a dominant figure, presidential approval becomes a key predictor of public support for the subversion of democracy, even more so than partisanship or the winner-loser gap. Influential and widely acclaimed populist presidents might compel voters to embrace the gradual dismantling of democracy, a dismantling disguised as a democratic enhancement.

Theoretical background

Populism and the subversion of democracy

Democratic backsliding and autocratization are episodes of gradual transformation in which liberal democracy progressively loses its democratic attributes and might, but not necessarily, turn into an electoral or closed autocracy (López Villegas and Frantz Reference López Villegas, Frantz, Lindstaedt and den Bosch2024; Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019, 1099). Recent theories of autocratización are mostly centered on the choices and strategies adopted by political actors in different settings (Schedler Reference Schedler, Croissant and Tomini2024, 22; Tomini et al. Reference Tomini, Gibril and Bochev2023, 121–122). Actor-centered perspectives are especially focused on elected leaders and parties who subvert democracy by gradually dismantling checks and balances and curtail essential freedoms (Schedler Reference Schedler, Croissant and Tomini2024, 19).

Episodes of democratic backsliding are usually driven by illiberal incumbents who openly reject democratic norms and procedures, political pluralism, and minority rights while tolerating political violence (García Holgado and Mainwaring Reference García Holgado and Mainwaring2023; Medzihorsky and Lindberg Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2023). Undemocratic and illiberal incumbents are often personalistic leaders who justify their actions on the basis of supposedly exceptional individual qualities (Brunkert and von Soest Reference Brunkert and von Soest2023) and who may threaten democracy when weakly institutionalized parties grant them legislative majorities (Rhodes-Purdy and Madrid Reference Rhodes-Purdy and Madrid2020). Weyland (Reference Weyland, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017) characterizes these personalistic leaders as populists who advance their political agenda by circumventing and undermining democratic procedures on behalf of a direct connection with the electorate.

Personalism and populism might be complementary yet different political attributes among illiberal executives (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2018). Indeed, in line with the ideational perspective, populism is defined here as a set of Manichaean ideas that represent politics as a moral struggle between the “good” and “evil,” or the “People and the “elites,” respectively (Hawkins and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Hawkins and Rovira Kaltwasser2017). Populist ideas are not undemocratic per se. Nevertheless, these ideas often provide the “ideological motivation” that leads personalist and illiberal incumbents to undermine democracy (Benasaglio Berlucchi and Kellam Reference Benasaglio Berlucchi and Kellam2023, 820). Populism typically provides the ideational framework that justifies a wide variety of strategies and political maneuvers aimed at advancing “executive aggrandizement” (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016), electoral manipulation, or infringements on citizens’ rights and freedoms. In that regard, populist ideas often serve as powerful tools to motivate voters into supporting the government’s strategies for democratic subversion. The question that arises, however, is under which circumstances voters would embrace the democratic dismantling advanced by populist governments.

Public support for the populist subversion of democracy

Populist leaders and parties are usually elected to address severe performance crises and representative deficits (Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Kaltwasser and Andreadis2020)—and they rarely, if ever, campaign against democracy as an abstract idea (Cella et al. Reference Cella, Çinar, Stokes and Uribe2025). Moreover, according to the theory of conditional populist support (Wiesehomeier et al. Reference Wiesehomeier, Ruth-Lovell and Singer2025), populists should be aware that voters are willing to hold them accountable for their democratic accomplishments. As Wiesehomeier et al. (Reference Wiesehomeier, Ruth-Lovell and Singer2025) argue, voters support the populist incumbents on the condition that their satisfaction with democracy improves. From this point of view, populist transgressions of democratic norms and procedures should be punished at the ballot box. However, such an expectation assumes that populist supporters are willing to evaluate the democratic quality of the regime in an impartial manner, free from any partisan biases—and that might not always be the case.

Instead, I argue that voters who believe the populist president is doing a good job are more likely to endorse democratic transgressions. The argument stems, on the one hand, from research demonstrating that citizens’ political beliefs and behavior are largely influenced by political elites (Bisgaard and Slothuus Reference Bisgaard and Slothuus2018; Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013). Political elites’ positions on policy choices and political issues help voters form attitudes toward a number of complex and frequently contradictory issues (Leeper and Slothuus Reference Leeper and Slothuus2014; Slothuus and Bisgaard Reference Slothuus and Bisgaard2021). Moreover, motivated reasoning theory has shown that voters often prioritize cognitive consistency over factual accuracy (Leeper and Slothuus Reference Leeper and Slothuus2014; Taber and Lodge Reference Taber and Lodge2016). Rather than seeking reliable and verified information to update their beliefs, voters seek confirmation of their political ideas and identities—and are willing to “rationalize” their representative’s undemocratic behavior by believing it is actually democratic (Krishnarajan Reference Krishnarajan2023).

On the other hand, populists in power usually take seriously the task of cultivating popular support to legitimize their rule and sway public opinion in their favor. In particular, populist presidents typically advance democratic subversion while claiming to promote democracy on behalf of the people and against corrupt, evil elites, significantly shaping public opinion and citizens’ views and preferences. According to Love and Windsor (Reference Love and Windsor2018, 542), populist presidents have “immense power to shape public support (for good or ill) through discourse via media.” On behalf of their electoral mandate, populist presidents consistently claim to embody and represent the collective will while striving to expand their power and influence. As Bessen (Reference Bessen2024, 6) writes: “Populist discourse presents the expansion of executive power as democratic.” Populist presidents also allege that the separation of powers is an instrument of “corrupt elites” (Bessen, Reference Bessen2024, 7). Populist presidents thus tend to present voters with a stark choice: Either they remain loyal to the incumbent in advancing a populist understanding of democracy, or they are portrayed as supporters of the political establishment, regarded as “elitist” and “corrupt.”

In this manner, motivated by the populist rhetoric, voters who believe the president represents their views or interests are expected to support regime transformation, even if that entails the subversion of democracy. As a growing body of scholarship indicates, citizens tolerate democratic violations as partisan, policy-based, ideological polarization, or as increases in affective polarization (e.g., Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Kingzette et al. Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Barry Ryan2021; Simonovits et al. Reference Simonovits, McCoy and Littvay2022). Recent studies in Latin America indicate that political identification with the president or the party in government is consistently associated with permissive attitudes toward executive aggrandizement and democratic subversion (Singer Reference Singer2018)—Latin American elites are also prone to “fiddling while democracy burns” for similar reasons (Singer Reference Singer2021). The winning voters are also more likely to perceive essential political freedoms in their country, even if the incumbents have already undermined these democratic attributes (Monsiváis-Carrillo Reference Monsiváis-Carrillo2020). For instance, Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Smith, Moseley and Layton2022) found that voters who voted for Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil reported increased abstract support for democracy while also allowing for institutional ruptures that benefit authoritarian incumbents. Likewise, populist supporters were more likely to express higher regime support and political trust (Monsiváis-Carrillo Reference Monsiváis-Carrillo2021), while survey and experimental evidence show that the incumbent’s populist discourse is associated with increased support for executive aggrandizement among the president’s voters (Bessen Reference Bessen2024).

More specifically, I argue that voters who approve of the populist president’s performance in office might be willing to endorse the incumbent’s antidemocratic advancements. While most research examines partisan division, or the voters’ status as winners or losers in elections, I shift the focus to presidential approval. The reason is that populist presidents might become more salient and dominant than political parties. As Selçuk (Reference Selçuk2024, 28–37) argues, leader-centered affective polarization might be more important than ideological or party polarization when parties are in disarray. Moreover, populists are not only highly charismatic leaders—they are often highly innovative in terms of populist symbolism and imagination (Sakki and Hakoköngäs Reference Sakki, Hakoköngäs and Sakki2025). Seeking to enhance their grip on power, populist presidents cultivate public support beyond their electoral or party base by framing their actions as a struggle between the “People” and “the elites.” Populist presidents thus become highly influential and polarizing figures by shaping and framing the political agenda in a manner that compels both parties and voters to position themselves in relation to the presidential stance.

In summary, in a scenario where the populist president is a dominant figure, voters who support the executive are expected to tolerate the subversion of democracy to a greater extent than those who oppose the government. They should be compelled to embrace the incumbent’s regime transformation, provided that they believe the president is doing a good job. Citizen attitudes toward democracy under AMLO (2018–2024) are a case in point.

Populism and the subversion of democracy in Mexico

In his 2018 inauguration speech, after campaigning to “make history together,” AMLO claimed to have “the People’s mandate” to begin “the Fourth Transformation”—not simply “a change of government” but a “change of regime.” He added, “We will also transition toward a true democracy,” where “the shameful tradition of electoral frauds will be over.”Footnote 2 However, rather than delivering “true democracy,” AMLO advanced autocratization (López Leyva and Monsiváis-Carrillo Reference López, Armando and Monsiváis-Carrillo2024). A benchmark to recognize the onset of an episode of autocratization is a minimum 1 percent annual decrease in the Varieties of Democracy’s Electoral Democracy Index for at least five years without reversal or interruption (Maerz et al. Reference Maerz, Edgell, Wilson, Hellmeier and Lindberg2023, 6). According to this criterion, Mexico’s ongoing episode of autocratization began in 2019, during AMLO’s first year in office. That year, Mexico’s score on the Electoral Democracy Index was 0.685 out of 1.0. By 2024, the score had already dropped by 18 points (0.505). During the same period, other varieties of democracy significantly declined as well (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Varieties of Democracy in Mexico (1996–2024)

Source: V-Dem v. 15 (v-dem.net).

A key to understanding Mexico’s democratic backsliding is AMLO’s ability to become the most important figure in the political system during his presidency. Using his daily morning conferences (“mañaneras”) as one of his main official forums for direct communication with the public, López Obrador cultivated an image of an austere and honest leader, committed to the “People’s well-being,” and particularly sympathetic to the poor. Moreover, the president consistently presented himself as above partisan politics by often referring to “our movement” and rarely, if ever, taking a stance on behalf of Morena, the official party.

In this manner, AMLO’s charisma and personalistic leadership played a decisive role in shaping an emerging populist divide in the party system after the near collapse of the traditional political parties in the 2018 and 2024 presidential elections. According to Castro Cornejo (Reference Castro Cornejo2023), AMLO’s success in 2018 was less connected to voters’ ideology or programmatic preferences and more to affective polarization toward the National Action Party (PAN) and the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) (see also Béjar Reference Béjar2024). Similarly, the 2023 AmericasBarometer indicates that 75.8 percent of survey respondents declared identification with no political party. Morena took 20.1 percent of the remaining electorate. However, Morena remained weakly institutionalized and largely depended on AMLO’s leadership (Bruhn Reference Bruhn2021).

At the same time, a distinctive feature of AMLO’s rule was “doublespeak populism” (Dussauge-Laguna Reference Dussauge-Laguna, Guy Peters, Pierre, Yesilkagit, Bauer and Becker2021)—the president’s Manichaean rhetoric to conceal the assault on public administration and democratic governance (see also Guillén and Monsiváis-Carrillo Reference Guillén and Monsiváis-Carrillo2024; Monsiváis-Carrillo Reference Monsiváis-Carrillo, López Leyva and Monsiváis Carrillo2024b). AMLO’s acclamation of the “People” was a trademark of his administration, as were his attacks toward “corrupt” and “conservative” elites. For instance, the president often appealed to a plebiscitary and majoritarian notion of democracy to legitimate popular consultations and referenda (Aguilar Rivera Reference Aguilar Rivera2022; Monsiváis-Carrillo Reference Monsiváis-Carrillo, Guillén, Monsiváis-Carrillo and Mora2022) while undermining state capacity and public governance (Dussauge-Laguna Reference Dussauge-Laguna, Guy Peters, Pierre, Yesilkagit, Bauer and Becker2021; Ibarra del Cueto Reference Ibarra del Cueto2023). Other studies have also shown that AMLO’s populist speech “trash-talked” democratic institutions (Cella et al. Reference Cella, Çinar, Stokes and Uribe2025), propagated disinformation through official channels (Article 19 2023), and incited political and affective polarization (Sarsfield and Abuchanab Reference Sarsfield and Abuchanab2024). The presidential rhetoric targeted opposition parties, journalists, human rights organizations, think tanks, regulatory agencies, the National Electoral Institute (INE), the Judiciary, and the Supreme Court, among others, which were also subjected to significant budget restrictions, co-optation strategies, or policy turnovers (see, e.g., Dussauge-Laguna Reference Dussauge-Laguna, Guy Peters, Pierre, Yesilkagit, Bauer and Becker2021; Gordillo García Reference Gordillo García, López Leyva and Monsiváis Carrillo2024; López-Robles Reference López-Robles2024; Reyes-Galindo Reference Reyes-Galindo2023; Reyna Reference Reyna2023; Villanueva Ulfgard Reference Villanueva Ulfgard2023).

AMLO’s campaign for regime transformation took a decisive turn in 2022, when his government attempted to implement far-reaching reforms in the electoral system—Plan A and then Plan B. Allegedly aimed at eliminating “electoral frauds” and bringing “republican austerity” into election administration, these reforms threatened electoral democracy instead (Monsiváis-Carrillo Reference Monsiváis-Carrillo2024b). Plan A was a constitutional reform that failed when Morena fell short of the votes needed to pass it. Plan B was hastily promulgated but struck down by the Supreme Court on the basis of severe violations of the legislative process (Martín Reyes Reference Martín Reyes2024). Then, early in 2024, AMLO announced Plan C, another comprehensive package of constitutional reforms. Plan C was centered again on the electoral system but included the judiciary and the Supreme Court. All these initiatives proposed the appointment of electoral authorities, justices, and Supreme Court ministers by popular election.

As the 2024 presidential election approached, Morena, the official party, appointed AMLO’s protégée, Claudia Sheinbaum, as the presidential candidate.Footnote 3 After campaigning to “continue the transformation,” Sheinbaum was elected with nearly 60 percent of the vote.Footnote 4 The official electoral coalition, led by Morena, also received 54 percent of the vote for Congress. Then, the electoral authorities adopted a literal but still controversial interpretation of the law and the Constitution in the allocation of legislative seats (Murayama Reference Murayama2024). As a result, Morena and its allies were awarded 73 percent of the seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 64 percent in the Senate. This meant that AMLO’s last month in office converged with the onset of the newly elected legislature. The president thus hurried to promulgate the constitutional reform that enacted unprecedented changes to the judiciary, “dismantling constitutional democracy” (Velasco-Rivera Reference Velasco-Rivera2025), and provided as well a legal framework for military engagement in civil governance well beyond national defense (Bonilla-Alguera et al. Reference Bonilla-Alguera, Arana-Aguilar and Padilla-Oñate2025).

Hypotheses

Soon after being elected, and even months ahead of taking office, López Obrador became the most influential figure in Mexican politics. His populist worldview largely reshaped the country’s public debate, summoning voters to embrace his regime transformation or risk being identified with the “morally defeated opposition,” loyal to “conservative” and “corrupt” institutions. In a study about the relationship between populism and regime support in Latin America, I found that AMLO’s ascent to power was correlated with increased regime and institutional trust (Monsiváis-Carrillo, Reference Monsiváis-Carrillo2021). Castro Cornejo and Langston (Reference Castro Cornejo and Langston2024) also found that Morena identifiers are satisfied with democracy under AMLO and more inclined to tolerate military coups or “executive aggrandizement.” Likewise, morenistas are more satisfied with democracy and more trusting of the president than other voters but also more inclined to distrust INE, the judges, and certain features of electoral integrity (Monsiváis-Carrillo Reference Monsiváis-Carrillo2023). Polarization and conspiratorial thinking motivated Morena voters to believe in the alleged 2006 electoral fraud (Castro Cornejo Reference Castro Cornejo2024), which AMLO was unable to prove in court. Overall, by “trash-talking” political institutions and actors, AMLO paved the way for regime transformation while still claiming to promote democracy (Cella et al. Reference Cella, Çinar, Stokes and Uribe2025).

Along this line, I expect that Mexican citizens who approve of President López Obrador’s performance in office will display the range of attitudes that lend support to the subversion of democracy. For instance, the president consistently declared that his government had left “corruption” and “electoral fraud” behind and was advancing toward a “true democracy.” The first hypothesis is thus about voters’ assessment of the Mexican regime:

H1: Approval of AMLO’s performance is correlated with a high probability of believing Mexico is a democratic regime.

Citizens should be comfortable with the idea that the president is allowed to disobey or infringe on the law as long as it helps the incumbent deliver on his promises. Characteristically, both López Obrador and his administration displayed a manifest hostility toward the rule of law. AMLO made clear his position on this issue: “Justice” should prevail over the law. As he once stated, visibly outraged, “Do not tell me the story that the law is the law.”Footnote 5 His authority was supposed to override any formal rule.Footnote 6 The second hypothesis reads like this:

H2: Approval of AMLO’s performance is correlated with a high probability of expressing tolerance for the incumbent’s unlawful behavior.

In the third place, illiberal and populist governments usually believe that any kind of political pluralism or opposition is illegitimate. Leveraging deep-seated affective polarization (Castro Cornejo Reference Castro Cornejo2023), López Obrador cast the party opposition as corrupt and antidemocratic actors. His followers may then agree to restrict the opposition’s rights and freedoms, particularly if the president claims they are hindering the “fourth transformation.” This leads to the following hypothesis:

H3: Approval of AMLO’s performance is positively correlated with support for imposing restrictions on the political opposition’s democratic rights.

On the other hand, populist presidents are frequently moved by the ambition to rule without constraints or procedural limitations. They should thus attempt to co-opt or capture the National Congress and the Supreme Court. Since 2018, AMLO enjoyed majoritarian control of both Chambers of Congress—thus, he barely attacked the legislative branch. However, the Supreme Court became one of the most significant targets of the president’s virulence, budget cuts, co-optation, and finally, dissolution through constitutional reform (Inclán Oceguera Reference Inclán Oceguera, López Leyva and Monsiváis Carrillo2024). Therefore, it is expected that AMLO’s supporters would endorse the executive override of the separation of powers—and particularly the Supreme Court:

H4.1: Approval of AMLO’s performance is correlated with a high probability of endorsing the presidential override of Congress.

H4.2: Approval of AMLO’s performance is correlated with a high probability of endorsing the presidential dissolution of the Supreme Court.

Empirical strategy

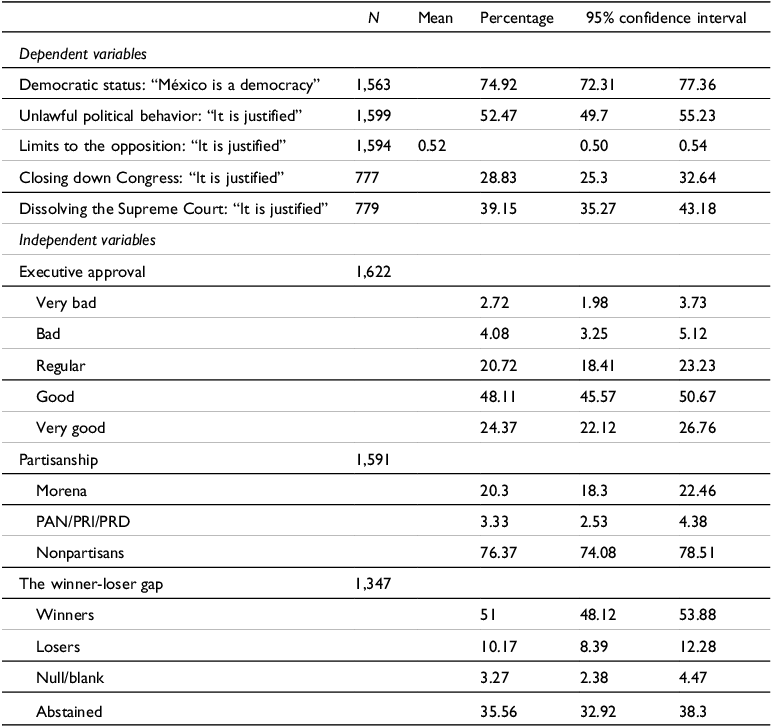

To test the empirical expectations, this study leverages the AmericasBarometer’s survey conducted in Mexico.Footnote 7 The AmericasBarometer surveys are based on representative, multistage probabilistic samples of the voting-age adults in the national population. The analysis examines the relationship between presidential approval and the dependent variables using the 2023 AmericasBarometer Mexico Survey, which comprises 1,622 face-to-face interviews conducted from May 5 to June 4, 2023. The analysis also includes a series of tests using partisanship and the winner-loser gap as independent variables—see the descriptive statistics in Table 1. The empirical tests are also replicated on the available AmericasBarometer data prior to 2023.Footnote 8

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Source: AmericasBarometer 2023. Estimations accounting for the survey design.

Dependent variables

The first dependent variable is Mexico’s democratic status, measured as a dummy variable after the item “DEM20. Is Mexico a Democracy?” In March 2019, 66 percent of the Mexican public responded yes (95 percent confidence interval = 63 percent–68 percent). Four years later, in 2023, as shown in Table 1, the percentage increased to 75 percent (95 percent CI = 73 percent–77 percent). The second dependent variable is unlawful political behavior, a dichotomous indicator assessing the trade-off between demanding that politicians obey the law and giving them ample leeway to fulfill their promises. Respondents were presented with the item “CRG2. In order to deliver on promises to the people, it is justifiable for politicians to act outside the law.” It is important to note that this is not about the president’s unlawful behavior. However, precisely because of that, the item provides a stringent test of voters’ support for democratic transgressions under a populist government presided by an influential leader. Table 1 indicates that half of the electorate deemed it justifiable to disobey the rules (52 percent).

The next dependent variable, limitations to the opposition’s voice and vote, taps into support for imposing limitations on the political opposition’s democratic rights. This time, the president is expected to clamp down on the opposition for the sake of the country: “POP101. It is necessary for the progress of this country that our president limit the voice and vote of opposition parties. How much do you agree or disagree with that view?” The answers are provided on a seven-point scale ranging from 0 to 1. In 2023, the estimated mean is 0.52 (0.50, 0.54) (Table 1). The same question was fielded by the AmericasBarometer in 2008 (n = 1,480), 2010 (n = 1,462), and 2012 (n = 1,478), under Felipe Calderón’s (2006-2012) administration. However, as shown in Figure 2, support for the president imposing limitations on the opposition is significantly higher in 2023, when AMLO was in power—11 points on average.

Figure 2. Attitudes toward democratic subversion in Mexico over time

Note: Estimated proportions with 95 percent confidence intervals accounting for the survey design.

In turn, public support for executive coups is measured as follows. First, item JC15A addresses “support for closing down Congress”: “Do you believe that when the country is facing very difficult times, it is justifiable for the president of the country to close the Congress/Parliament and govern without Congress/Parliament?” This question was applied in a split random sample (n = 777). In 2023, almost a third of the electorate supported the president if he had to close down Congress (29 percent, 95 percent CI= 25 percent, 32 percent)—see Table 1. This variable was also measured in 2010 (n = 1,431), 2012 (n = 1,442), 2014 (n = 1,430), 2017 (n = 1,439), 2019 (n = 1,478), and 2021 (n = 640). As shown in Figure 2, support for the override of the legislature by the executive has increased since AMLO’s election.

Second, public endorsement for the “dissolving of the Supreme Court” was measured by item JC16A in the other half of the sample (n = 779): “Do you believe that when the country is facing very difficult times, it is justifiable for the president of the country to dissolve the Supreme Court?” Remarkably, 39 percent (35 percent, 43 percent) responded yes. Samples from 2010 (n = 1,439), 2012 (n = 1,427), and 2019 (n = 1,462) indicate that the share of the electorate who would agree to the dissolution of the Supreme Court is larger under AMLO than under Felipe Calderón. Furthermore, the percentage increased from 32 percent in 2019 to 39 percent in 2023 (Figure 2).

Independent variables

The independent variable, executive approval, is measured by the following question: “M1. Speaking in general of the current administration, how would you rate the job performance of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador?” The original 5-point ordinal variable was reversed so that possible answers range from “very bad” to “very good.” At the time of the survey, 48.1 percent of the voting-age population rated the president’s performance as “good” and 24.4 percent as “very good.” That is a sound 72.5 percent of the electorate (Table 1). In the AmericasBarometer surveys, neither Felipe Calderón nor Enrique Peña Nieto ever enjoyed as much approval as AMLO (Figure 3).

Figure 3. “Is the president doing a ‘good job’?” Executive approval in Mexico (2008–2023)

Note: Estimations accounting for the survey design.

In addition, a series of supplementary analyses was performed using partisanship and the winner-loser gap as independent variables. As shown in Table 1, 20 percent of the electorate identify with Morena, the official party (item VB11). The opposition parties combined, the National Action Party (PAN), Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), and Democratic Revolution Party (PRD), amount to 4 percent. Instead, “nonpartisans or independents” represent 76 percent of voters in 2023 (item VB10). On the other hand, the winner-loser gap merges VB2: “Did you vote in the last presidential elections of 2018?” and VB3N: “Who did you vote for in the last presidential election of 2018?” Those who voted for AMLO are the “winners” (51 percent), PAN, PRI, or PRD candidate supporters are the “losers” (10 percent), “blank” are citizens who choose “none,” “other” or “null” (3.2 percent), and those who did not vote, “abstained” (36.6 percent) (Table 1).

Method

The AmericasBarometer uses a stratified, multistage cluster sampling design to collect the survey data. The survey design should be incorporated into the analyses to reduce the likelihood of producing biased estimates or standard errors that do not account for the sample’s sources of variance. By applying AmericasBarometer recommendations (LAPOP Lab Reference LAPOP2023, 4), the analysis is conducted using descriptive tools and regression models for survey data. Most dependent variables were modeled using logistic regressions for survey data. The exception is limitations on the opposition’s voice and vote, a 7-point variable that was modeled using linear regressions for survey data. Standard errors are computed by using Taylor-linearized variance estimation.

In the analysis presented here, executive approval is modeled as a continuous variable. However, as a robustness test, I also contrasted each level of the independent variable with the baseline—those who believe the president’s performance is “very bad.” This is a more demanding test than modeling executive approval as a continuous variable. As Hainmueller et al. (Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu2019) argue, continuous independent variables with very few observations in some intervals might produce unstable or model-dependent results. Although their warnings are aimed at multiplicative interaction models, their remarks might also apply to other situations as well. Therefore, each level of the independent variable was evaluated as a qualitative category. The substantive results are the same, and the regression outcomes are available in the online appendix.

Finally, all models control for crucial covariates: interpersonal trust, corruption victimization, political interest, ideology, sex, age, educational attainment, ethnicity, urban-rural residence, subjective household income, and household wealth (Córdova Reference Córdova2009). Because of space constraints, item wording, descriptive statistics, and additional information are all shown in the online appendix.

Results

Is Mexico a democracy? The first hypothesis asserts that citizens are more likely to believe that their country is a democracy if they also believe AMLO’s government is doing a very good job. The results are straightforward: While most people think of Mexico as a democratic country (75 percent), the expected percentage increases to 86 percent when citizens rate the president’s performance as “very good.” At the opposite extreme, when the executive’s job performance is rated as “very bad,” only 43 percent of the electorate are expected to share the same opinion. Figure 4a presents the marginal predictions based on model M1 from Table 1—all covariates at their means.

Figure 4. Executive approval and support for the subversion of democracy

Note: Marginal predictions with 95 percent confidence intervals. All covariates at their means.

The second hypothesis shifts the focus to the relationship between executive approval and permissive attitudes toward democratic subversion. In H2, the dependent variable is support for unlawful political behavior, as long as it is deemed necessary for politicians to fulfill their promises. In this scenario, model M2 provides straightforward evidence in support of the hypothesis (Figure 4a). The data indicate a strong relationship between the independent and outcome variables. When voters rate presidential performance as “very bad,” only 35 percent are expected to express tolerance for unlawful political behavior. However, as presidential approval increases, the proportion of citizens willing to permit unlawful behavior on the condition that politicians deliver on their promises also rises. Thus, if people believe AMLO is doing a “good job,” breaking the law is expected to be justified by 53 percent of the electorate. This share reaches 59 percent if presidential job performance is considered “very good.”

Likewise, the third hypothesis (H3) posits that voters will agree with the president if he decides to limit the opposition’s voice and vote for the sake of the country when they are happy with the executive’s performance. The results from M3 also support the empirical expectations—see Figure 4b. Provided that 0 means “strongly disagree” and 1 means “strongly agree,” voters are expected to shift from a mean of 0.31 (0.20, 0.42) to a mean of 0.58 (0.54, 0.62) if they move from being very dissatisfied to very satisfied with AMLO’s job performance.

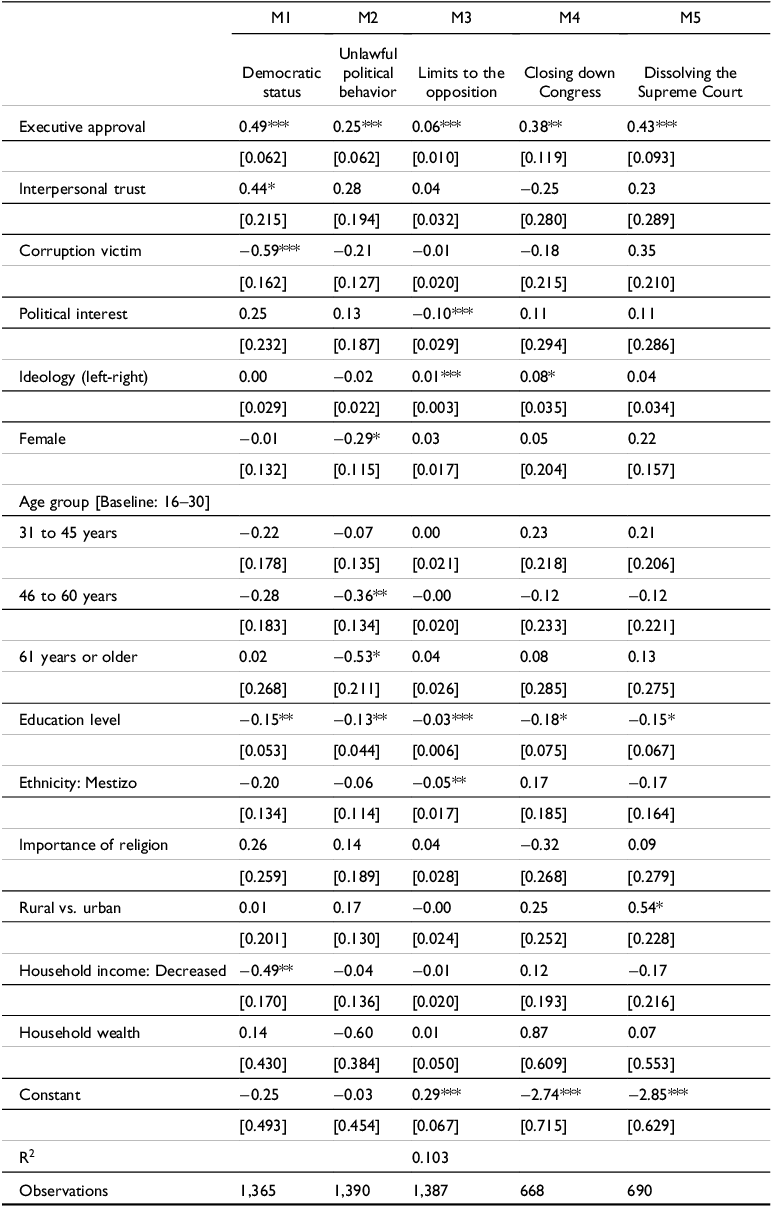

Hypotheses H4.1 and H4.2 address attitudes regarding the presidential suppression of the separation of powers during times that “are very difficult.” Model M4 in Table 2 indicates that the relationship between the independent variable and support for the president closing down Congress is statistically significant. For instance, the predicted probability of believing that the president is justified in shutting down the national legislature is 0.36 (0.28–0.43) at the highest level of executive approval (Figure 4c). In other words, a third of the electorate would justify AMLO’s decision should he choose to close down Congress—an unnecessary move, considering that Morena and its legislative coalition controlled the majority in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. On the other hand, the analysis does offer support for H4.2, as shown in M5 and Figure 4c. In this case, what is at stake is the dissolution of the Supreme Court. Almost half of those who believed AMLO was doing a “very good” job (49 percent, 42 percent–55 percent) in 2023 were willing to support the president if he decided to eliminate the highest tribunal in the country. Conversely, only 14 percent (7 percent, 22 percent) of those who perceived a “very bad” presidential performance endorsed the dissolution of the Supreme Court.

Table 2. Executive approval and support for the subversion of democracy

Notes: Regression models for survey data. Linearized standard errors in brackets.

***p < 0.001. **p < 0.01. *p < 0.05.

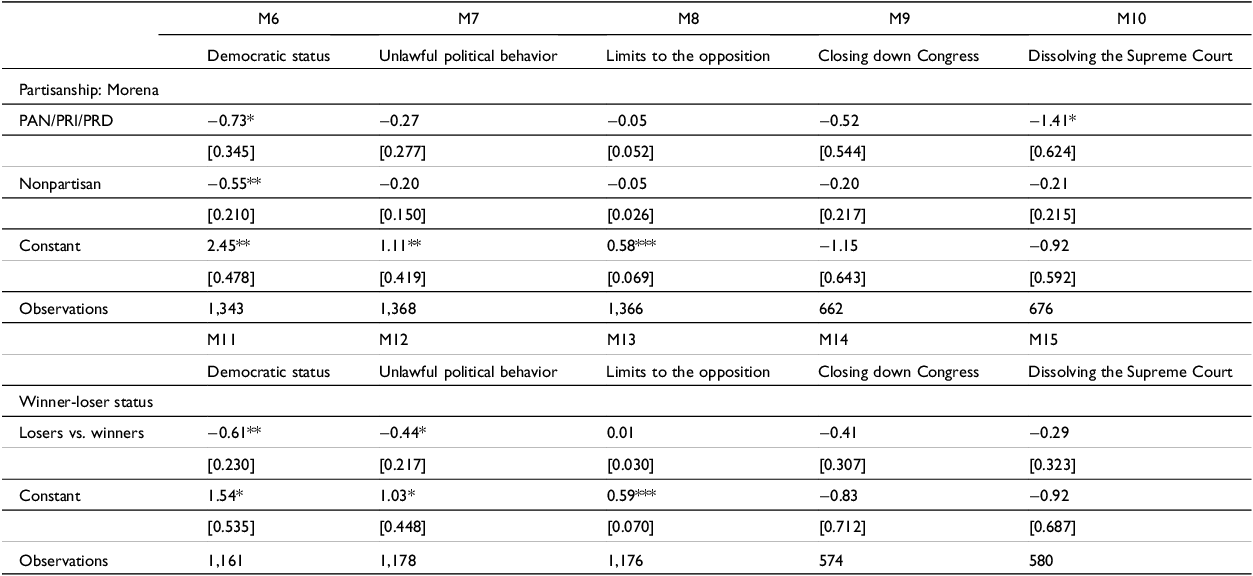

Alternative explanations

So far, the evidence suggests that citizens who approve of the president’s performance are more likely to believe that Mexico is a democracy and endorse certain decisions consistent with executive aggrandizement. The question, then, is whether citizens support AMLO’s populist transformation or if this is a pattern that should be more generally expected. For instance, it should be expected that Morena partisans reported a similar pattern of attitudes to those who feel represented by López Obrador. However, López Obrador’s supporters do not necessarily coincide with morenistas—in 2023, more than 70 percent of the electorate was satisfied with the presidential performance, but only 20 percent identified with Morena. The implication is that public endorsement for the subversion of democracy is not necessarily exclusive to Morena partisans. This is corroborated by the analysis reported in Table 3 (see also Figure 5). The data reveal, indeed, that Morena identifiers are more likely to believe that Mexico is a democracy than opposition voters and nonpartisans (M6, Figure 5a). Moreover, morenistas are more likely to support the idea that the president is justified in dissolving the Supreme Court in difficult times (Figure 5e). However, no other tests produce the expected outcomes. These results suggest that morenistas responded to AMLO’s appeals for an “authentic democracy” and his attacks against the Supreme Court. Nonetheless, endorsing the dismantling of democracy was seemingly not confined to voters identified with Morena.

Table 3. Partisanship and the winner-loser gap: Supplementary tests

Notes: Regression models for survey data. Control variables are included but not shown. Full results are available in the online appendix.

***p < 0.001. **p < 0.01. *p < 0.05.

Figure 5. Are either morenistas or winning voters more committed to subverting democracy than other voters?

Note: Marginal predictions with 95 percent confidence intervals. All covariates at their means.

The evidence is similar if the analysis examines the winner-loser gap in voters’ attitudes. In this case, it is expected that voters who supported the president in the last election (50 percent) report similar attitudes to those who are satisfied or very satisfied with the executive’s performance. In some instances, they are indeed similar. The results presented in Table 3 show that winners are more likely to believe that Mexico is a democracy than the losing voters (M11, Figure 5a). Winners are also more likely than the losers to tolerate unlawful political behavior (M11, Figure 5b). However, the winner-loser gap still provides less explanatory leverage of public support for the subversion of democracy than executive approval (see Figure 5).

Another explanation is that voters who approve of the president will display a similar attitudinal pattern regardless of who the president is. In this case, it should be expected to observe similar attitudes among satisfied voters under different Mexican presidents. Accordingly, several tests were performed using the available set of dependent variables from previous rounds of the AmericasBarometer. This time, the analysis evaluates whether the relationship between the executive approval and the dependent variables is influenced by the president in office. The data suggest, yet again, that AMLO’s performance evaluations are crucial to understanding citizens’ willingness to “delegate away democracy” (Singer Reference Singer2018). Figure 6 illustrates the findings—the full results are available in the online appendix in Tables A25–A27.

Figure 6. Does populism make a difference? Executive approval, Mexico’s status as a democracy, and support for presidential limitations on the opposition’s democratic freedoms

Note: Marginal predictions with 95 percent confidence intervals. All covariates at their means.

In the first place, the percentage of citizens who believe that Mexico is a democracy increased from 66 percent in 2019 to 75 percent in 2023. In addition, as shown in Figure 6a, the relationship between executive approval and the belief that Mexico is a democracy was not statistically significant in 2019. However, in 2023, this belief sharply increased along with executive approval. Therefore, not only did a larger share of voters perceive Mexico as a democratic nation in 2023 compared to 2019, but it also appears that this increase was driven by satisfaction with AMLO’s performance in office.

In the second place, the variable restrictions on the opposition’s voice and vote were measured under Felipe Calderón in 2010 and 2012, and then again in 2023, when AMLO was in office. The data indicate that the relationship between executive approval and the dependent variable is statistically significant in 2010 and 2023—see Figure 6b. However, in 2010, the relationship between these variables was not particularly strong (B = 0.02, p = 0.025) and became flat by the end of Calderón’s administration. The analysis indicates that, as Calderón’s time in office advanced, citizens appeared increasingly reluctant to allow the president to curtail the opposition’s voice and vote, even if they were satisfied with the president’s job performance. The evidence suggests, therefore, that voters’ support for imposing limitations on the opposition’s democratic rights is distinctively correlated with AMLO’s approval.

A similar trend is observed in voters’ support for executive coups. In 2010, voters who were very happy with Felipe Calderón were decidedly more likely to support the president if he chose to close down the national Congress or the Supreme Court. However, such a permissive attitude flattened in the following years. Figures 7a and 7b show that voters who approved of Calderón in 2012 seemed as reluctant as their less satisfied peers to delegate that type of power to the executive. The same is observed in 2014 and 2017, already under Enrique Peña Nieto’s presidency. It should also be underscored that, in those years, the percentage of citizens who were very satisfied with the presidential performance was significantly small: 5 percent in 2010, 6 percent in 2012, 4 percent in 2014, and 1 percent in 2017. Conversely, a substantial percentage of voters rated AMLO’s performance as “very good” (24 percent) in 2023. Moreover, in contrast to the final years in office of former presidents Calderón and Peña Nieto, support for the executive override of Congress and, notably, the Supreme Court increased under AMLO.

Figure 7. Populism makes a difference: Presidential approval and support for executive aggrandizement under Calderón, Peña Nieto, and AMLO

Note: Marginal predictions with 95 percent confidence intervals. All covariates at their means.

Discussion

One of the most striking findings in current research on attitudes toward democracy is that citizens might tolerate and even support the regime’s subversion and demise. In some cases, a crucial factor appears to be the misleading information provided by populist governments about what certain policies and institutional reforms would entail. When citizens trust the populist government to represent their interests or welfare, they may also trust its political purposes and decisions, even if these subvert democratic institutions and freedoms.

The analysis performed in this article suggests that such was the case in Mexico under AMLO. In this case, democracy was progressively eroded by a populist government that promoted political polarization and “trash-talked” specific democratic institutions on behalf of the “Fourth Transformation” and “authentic democracy” (Aguiar Aguilar et al. Reference Aguiar Aguilar, Cornejo and Monsiváis Carrillo2025; Cella et al. Reference Cella, Çinar, Stokes and Uribe2025; Monsiváis-Carrillo Reference Monsiváis-Carrillo, López Leyva and Monsiváis Carrillo2024a, Reference Monsiváis-Carrillo2024b). According to the theory of conditional populist support (Wiesehomeier et al. Reference Wiesehomeier, Ruth-Lovell and Singer2025), voters should have punished the incumbent’s behavior by expressing dissatisfaction with democracy and endorsing opposition candidates. Instead, in the spring of 2023, a substantial majority of the voters viewed Mexico as a democratic country—an even larger proportion than at the beginning of AMLO’s term. In addition, those voters who were the most satisfied with López Obrador’s performance in office were not only persuaded of Mexico’s democratic status. They were also the most likely to embrace the idea that politicians should be allowed to infringe the law to deliver on their promises, that the president should be allowed to restrict the opposition’s voice and vote, and that the executive is justified in shutting down Congress or, more significantly, dissolving the Supreme Court. Moreover, in the 2024 presidential election, voters responded to the incumbent’s assault on democracy by electing Claudia Sheinbaum, with nearly 60 percent of the ballots. Shortly thereafter, the implementation of Plan C began to reshape Mexico’s constitutional democracy.

The findings indicate that rather than holding the government accountable for advancing democratic backsliding, voters rewarded AMLO’s populist subversion of democracy. To explain such an outcome, this study argues that populist presidents invest considerable efforts to mobilize collective support for their political agenda while pretending to promote a genuinely responsive democratic system for the majority and the common people as they fight entrenched and corrupt elites. In this manner, voters identified with the incumbent could be persuaded to support undemocratic behavior and initiatives. Citizens might embrace the presidential discursive and symbolic struggle for the people and democracy while the president and his government undermine democratic norms and institutions.

These findings contribute to current research on the relationship between populism in power and voters’ tolerance for executive aggrandizement and democratic dismantling (e.g., Bessen Reference Bessen2024). This study suggests that dominant populist presidents play a crucial role in motivating voters to support the incumbent’s political transformation. In particular, the evidence indicates that AMLO’s quest for regime transformation influenced voters’ attitudes toward democracy and regime change in a more effective manner than Morena or the opposition parties. As the data show, executive approval provided a more comprehensive explanation of citizens’ attitudes toward democratic transgressions than partisanship or the winner-loser gap. More than ideology or programmatic partisanship, AMLO’s personalistic populism has arguably played a significant role in reshaping political and partisan identities through affective polarization (Béjar Reference Béjar2024; Castro Cornejo Reference Castro Cornejo2023).

The analysis also reveals that, relative to other Mexican presidents, the relationship between executive approval and tolerance for democratic subversion was particularly strong under López Obrador. Executive approval among nonpopulist presidents—such as Felipe Calderón and Enrique Peña Nieto—did not motivate citizens’ support for imposing limits on the opposition, shutting down Congress, or dissolving the Supreme Court to the same extent as AMLO. Calderón’s presidential approval justified restricting the opposition and overriding the Supreme Court, but only in the early years of his administration. Conversely, support for democratic subversion was strong during AMLO’s first year in office and so remained throughout his term. Thus, it could be argued that AMLO’s leadership not only succeeded in motivating voters to endorse his government’s democratic transgressions—it also enabled a momentous shift in the party system by eroding the left-right structure of party competition and introducing an emerging populist divide centered on the “continuation of the transformation” with Sheinbaum in the presidency and Morena as the official party.

The evidence presented here, however, is limited in a number of ways. The analysis relies on cross-sectional survey data and contextual information. In addition, there are no direct measures of AMLO’s populist discourse to assess its effects on support for the subversion of democracy. The evidence is therefore insufficient to support any causal claim beyond statistical correlations and empirical assessments informed by the political context. At the same time, there are additional lines of research that exceed the scope of the study. For instance, future studies should seek to disentangle the effects of populist rhetoric from those of personalistic leadership (Hawkins and Mitchell Reference Hawkins and Mitchell2025). The relationship between voters’ income, targeted benefits, or evaluations of the socioeconomic situation under AMLO and the Fourth Transformation and their attitudes toward democratic transgressions also deserves more examination. In that case, it should be underscored that the delivery of social programs or benefits was credited to AMLO and his government rather than nonpartisan, impartial, or universalistic social policy.

Along the same line, an important caveat is order. The available evidence is insufficient to disentangle a crucial difference in the mechanism that explains the results. It could be the case that voters ignored the negative effects of AMLO’s behavior and reforms, and thus simply lent their support to the executive. In other words, voters may have sincerely believed that the “Fourth Transformation” would actually improve the Mexican democracy. However, it could also be the case that some voters were well aware of the political implications of López Obrador’s pursuit of regime transformation. In such a case, voters may have shared with AMLO and his government an illiberal and majoritarian understanding of democracy, in which the separation of powers, checks and balances, free media, or political opposition are viewed as “undemocratic” constraints on the government that represents “the will of the majority.” These voters, so to speak, approved of the president’s performance because they expected that AMLO and his government would deliver a “majoritarian democracy”—a regime in which the incumbent party achieved a majoritarian status and ruled without constraints. The difference between these alternative explanations entails both theoretical and empirical importance and thus should be further examined in future research.

Despite the limitations, the findings are relevant beyond the Mexican case. The analysis sheds light on the attitudinal correlates of democratic backsliding under populism when the party system is in flux and the president not only drives the public conversation but also decisively shapes how the electorate makes sense of democracy. As the evidence suggests, under such circumstances, presidential approval could become a reliable predictor of voters’ willingness to embrace democratic dismantling disguised as democratic improvement. In Mexico, while enjoying widespread approval, López Obrador arguably succeeded in persuading a large proportion of the electorate that his “regime transformation” would deliver a “true democracy,” when in fact, an illiberal regime was in the making.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/lar.2025.10110

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this article was presented at the LASA 2024 Congress in Bogotá, Colombia. The author thanks José Luis Mendez for his comments on the manuscript. The author is especially grateful to the anonymous LARR reviewers for their insightful remarks and suggestions.