1 Introduction

The English language has long served as the global lingua franca in aviation, officially since 1944 (ICAO, 1944), and it remains the most widely used lingua franca in this industry today. Historically, the choice appeared obvious given the influence of the United States (US) in aviation, including the presence of English-speaking ex-military pilots and major aircraft manufacturers (Crystal, Reference Crystal2003). Had the decision been made today, the outcome would likely be the same; English’s dominance continues to grow with no competing language in the foreseeable future. English is also widely used as a lingua franca in many other professional sectors, such as business and healthcare, due to increasing global mobility. Consequently, there has been a growing body of research on English as a lingua franca (ELF), particularly in fields such as academia and business.

Public attention to communication between pilots and air traffic controllers (hereafter ‘controllers’) has been sporadic, primarily arising when communication issues are reported in the media as contributing factors to accidents and incidents. Academic attention from applied linguistics started growing after the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), a United Nations specialised agency, adopted English proficiency requirements in 2003 in response to concerns that insufficient English proficiency among ‘non-native’ English-speaking pilots and controllers had contributed to past accidents. While specialised coded radiotelephony language is used in routine situations, more natural English is expected in abnormal or emergency situations, where communication shifts to English as a lingua franca. In these contexts, ICAO maintains that English proficiency is crucial. Accordingly, all ‘non-native’ English-speaking pilots and controllers are required to demonstrate proficiency by taking a test assessing six criteria: pronunciation, comprehension, structure, vocabulary, fluency, and interactions. Proficiency is evaluated on a scale from pre-elementary level 1 to expert level 6, with level 4 set as the minimum operational requirement. So-called ‘native speakers’ are effectively exempt, as their inherent proficiency is assumed to be at expert level 6 unless a speech impediment or excessively strong regional accent is detected during licensure (ICAO, 2022, n.d.). However, the criteria for evaluating these qualities – especially, who judges and on what basis internationally inappropriate accents are assessed – remain unclear, as does the assumption of expert competence in radiotelephony communication by being ‘native speakers’. This effectively imposes a ‘non-native speaker’ identity on pilots and controllers who use English as an additional language (L2+), framing them as deficient in competence (Holliday, Reference Holliday and Liontas2018; Piller & Bodis, Reference Piller and Bodis2022) and thus affecting their performance (discussed in Sections 4 and 5).

There is also a recurring policy regarding proficiency verification. Pilots and controllers who meet the minimum level 4 must retake a test every three years, while those at level 5 are tested every six years. This limited shelf life is somewhat questionable, given that pilots and controllers continuously learn through ongoing practice. Here ‘learning’ should not be understood in the second language acquisition sense but rather as engagement and development within communities of practice, which include members whose first language (L1) is English and L2+ members (discussed in detail in Section 2).

ICAO’s English proficiency requirements aimed for effectiveness by 2008, with a three-year transition period extending the deadline to March 2011. However, two months before this deadline, 137 of 191 (close to 72 per cent) member states at that time had not yet complied. Service providers in Italy and Romania claimed that all aviation personnel met the minimum level (Alderson, Reference Alderson2011). According to a report from Korea (Aviation Policy Division, 2009), many L2+ member states – including China, France, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Russia, and Taiwan – developed their own tests at the government level or national airline level. Alderson’s surveys (Reference Alderson2009, Reference Alderson2010, Reference Alderson2011), however, raised doubts about the quality of these tests, revealing that many testing organisations failed to provide sufficient, or indeed any, evidence of test quality and that their assessment processes fell short of international language testing standards. Fifteen years after policy implementation, only one test (the English Language Proficiency for Aeronautical Communication) has received ICAO’s recommendation. ICAO operates by member state consent and lacks authority to mandate policies, respecting member states’ sovereignty (MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie2010). Thus, while all member states agreed to the policy, which had been proposed in the name of safety – since not agreeing could be viewed as a loss of face – some or many L2+ states developed and implemented tests to maintain control and minimise the policy’s impact. In this context, questions arise regarding the rationale behind such responses by member states when their own safety is at stake, and whether the policy overlooks critical aspects of the target language use situation.

Performance and communication in professional settings are shaped by numerous interconnected elements, including work culture, values, history, relationships, domain knowledge, experience, expertise, and both language- and domain-specific aspects (e.g., Kim, Reference Kim2018; Kim & Elder, Reference Kim and Elder2009; Kim & Friginal, Reference Kim and Friginal2026). These elements can best be examined within the framework of communities of practice. In broader investigations of ELF, which predominantly occurs in intercultural contexts where English is used for specific purposes, the suitability of this framework – as opposed to the concept of a speech community – has been acknowledged but not thoroughly explored. Accordingly, this study aims to investigate the various aspects influencing aviation ELF, with a particular focus on pilot and controller performance and radiotelephony communication, and to situate these within the community of practice framework. Additionally, it reviews ICAO English proficiency requirements from this perspective. To address these aims, the study responds to the following research questions:

1. What language-specific and domain-specific aspects emerge from domain specialists’ evaluations of peers’ performance in naturally occurring situations?

2. How do domain specialists’ values inform the understanding of performance in radiotelephony within the framework of communities of practice?

3. What are the implications of domain specialists’ values for ICAO’s English proficiency requirements?

In the following section, Section 2, I attempt to identify multiple aviation communities of practice within the international community by drawing on key concepts from the framework, such as legitimate periphery participation, learning through practice and interaction among members, and evolving identities leading to expertise. To gain a deeper understanding of the international context, I contextualise radiotelephony communication by explaining the environmental challenges posed by voice-only communication. I then highlight shared and unshared repertoires among members of the international community. Shared repertoires relate to rules-based conventions developed in response to the environment challenges inherent in radiotelephony communication, while unshared repertoires pertain to the individual variations that members bring to this international context, constituting significant challenges for radiotelephony communication. To address these variations, accommodation skills, explored in pilot-controller interaction as well as in ELF studies in other contexts, are suggested as a way forward. Building on this background, Section 3 details the ICAO English proficiency requirements and critiques found in the literature, followed by an examination of differing interpretations and perceptions related to four frequently cited aircraft accidents that ICAO used to justify the establishment of the English proficiency standards. Moving from these extreme cases to more commonly occurring abnormal cases, Section 4 presents an instance of naturally occurring performance, drawing on domain specialists’ insights as they evaluate the performance captured in the recording. In Section 5, I discuss the findings reported in Section 4 in relation to the three research questions: the values that emerge as domain specialists evaluate their peers’ performance, how these values can be understood within the framework of communities of practice, and implications for ICAO’s English proficiency requirements. The Element then concludes with brief remarks.

2 Aviation English as a Global Lingua Franca within Communities of Practice

Originating from a social theory of learning, the concept of communities of practice is a well-established, practice-based model developed by social anthropologist Jean Lave and educational theorist and practitioner Etienne Wenger (Lave, Reference Lave2019; Lave & Wenger, Reference Lave and Wenger1991; Wenger, Reference Wenger1998). The suitability of this concept for describing ELF communication contexts has been recognised by scholars in the field (e.g., Canagarajah, Reference Canagarajah2007; Ehrenreich, Reference Ehrenreich, Jenkins, Baker and Dewey2017; House, Reference House2003; Seidlhofer, Reference Seidlhofer2009), particularly in contrast to the concept of the speech community, which focusses on shared norms or a single linguistic variety in a community (Hymes, 1972; Labov, Reference Labov1972), such as Australian English and British English. ELF communication, which often occurs beyond the boundaries of traditional speech communities, takes place in intercultural contexts where interactants from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds engage with one another. House (Reference House2003) briefly mentions the potential suitability of the communities of practice framework for capturing the interactional features of ELF, while Canagarajah (Reference Canagarajah2007) argues that the practice-based nature of this model makes it particularly well-suited for understanding ELF realisations. Indeed, there are no shared norms or single varieties that can fully explain ELF interactions. On the contrary, as Canagarajah (Reference Canagarajah2007) contends, the variation that each individual brings to the interaction and the ways in which participants manage these variations, are central to these communicative exchanges. The focus of ELF research is on communicative features that emerge in interactions; however, to fully understand the complexity of these contexts, it is necessary to adopt a broader approach. Accordingly, this section attempts to do so by situating aviation communities within the communities of practice framework.

The concept of apprenticeship is important in examining communities of practice. In Lave and Wenger’s (Reference Lave and Wenger1991) earlier book, descriptions are provided of apprenticeships in five different communities of practice: Yucatec midwives, tailors, naval quartermasters, meat cutters, and nondrinking alcoholics, as well as a medical claims processing centre discussed in Wenger’s (Reference Wenger1998) later book. The contexts of Yucatec midwives, tailors, and meat cutters evoke a somewhat archaic sense of outdated times, seemingly irrelevant to the present day. However, by citing a mathematical problem-solving activity undertaken by a member of a family – where the family is considered a community of practice in this case – during everyday grocery shopping in a supermarket (Murtaugh, Reference Murtaugh1985), Lave (Reference Lave2019) convincingly demonstrates what occurs in everyday mathematical practice, which differs significantly from conventional conceptions of math problem solving. In Murtaugh (Reference Murtaugh1985):

I just keep putting them in until I think there’s enough. There’s only about three or four [apples] at home, and I have four kids, so you figure at least two apiece in the next three days. These are the kinds of things I have to resupply. I only have a certain amount of storage space in the refrigerator, so I can’t load it up totally … Now that I’m home in the summertime, this is a good snack food. And I like an apple sometimes at lunchtime when I come home.

Lave (Reference Lave2019) explains that although apprenticeships are ubiquitous, they are often not recognised as learning in practice or apprenticeships because they are considered informal and thus are less valued or overlooked in most modern education systems. She further argues that apprenticeship studies, in the anthropological sense, provide a means to explore how learning occurs independently of formal teaching. She notes that apprenticeship differs from schooling or socialisation in that it is always situated within practice. Lave (Reference Lave2019) also observes that we are all apprentices within the communities of practice to which we belong, such as the shopper in Murtaugh’s study mentioned earlier, with home or family serving as a community of practice.

Lave (Reference Lave2019) conceptualises learning as engagement with others within communities of practice – in other words, learning through practice – and identifies ‘changes in knowledge and action’ as central to the process of apprenticeship. Thus, Lave and Wenger (Reference Lave and Wenger1991) and Lave (Reference Lave2019) argue that communities of practice themselves provide learning opportunities for all members, whether peripheral (i.e., newer) or old-timers (i.e., more experienced), as they participate within them. In this framework, learning is always understood as situated in everyday (work) life, occurring sometimes through observation of more experienced individuals or peers with lower levels of participation, and at other times through medium-level, active, or fuller participation while engaged in practice. Additionally, as newer members move from their peripheral participation to fuller participation, and as senior members leave communities of practice, they contribute historical traces of artefacts, including physical, linguistic, and symbolic forms, along with social structures. In this way, practices are constituted and reconstituted over time (Lave & Wenger, Reference Lave and Wenger1991).

Building on this background, I situate aviation communication within the framework of communities of practice. This will help understand radiotelephony communication between pilots and controllers, who bring their values, perceptions, and work cultures, among others, from both local and international communities into their interactions. First, I discuss the unique multiple memberships held by pilots and controllers engaged in international radio communication. Next, I explore the concept of learning in practice and the evolving identities within the international aviation community of practice. I then examine the elements that constitute this international community, including environmental challenges and both shared and unshared repertoires among its members. Lastly, I review accommodation as a strategy to bridge gaps in unshared repertoires, drawing on insights from ELF research in other contexts.

2.1 Multiple Memberships

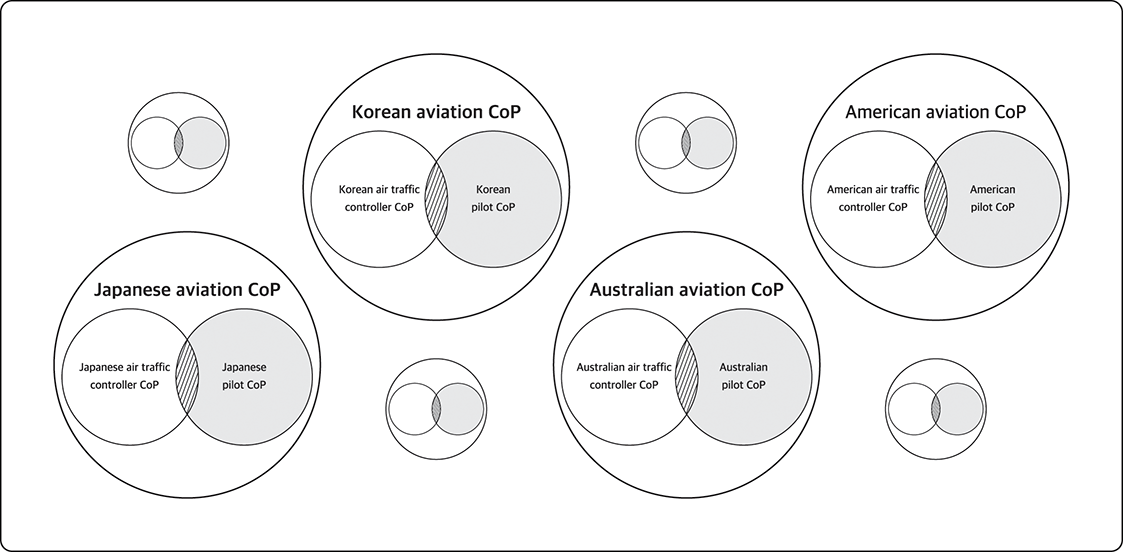

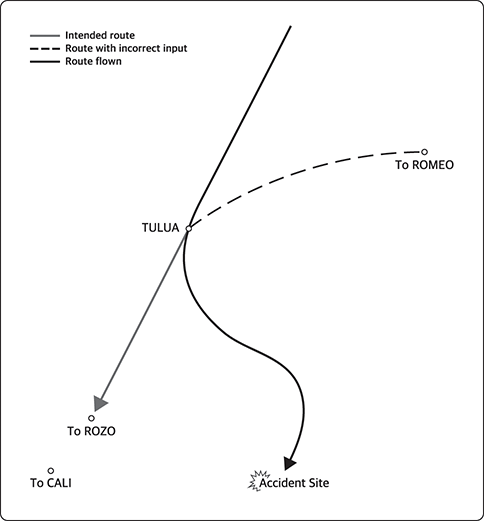

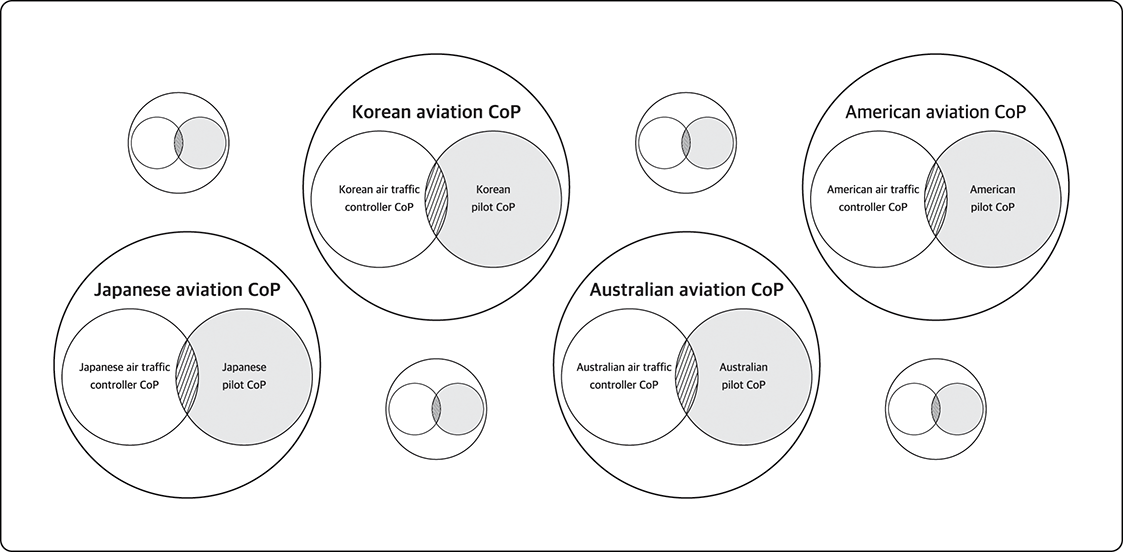

In the context of international aviation, pilots and controllers hold multiple memberships across several different but interrelated communities of practice, as summarised in Figure 1. The following description is based on a one-day nonparticipant observation of three air traffic control units in Korea, supplemented by audio-recorded explanations provided by controllers in each unit, as well as my long-standing interactions with pilots and controllers and my research on aviation communication.

Figure 1 International aviation community of practice (CoP)

There are three main communities of practice: those of pilots, controllers, and the combined community of pilots and controllers. Additionally, within and across these communities, individual memberships may vary depending on position and level of expertise. With increasing mobility in recent years, airline companies themselves have become multicultural contexts. For example, approximately half of the captain pilots in one Korean airline are foreign nationals (Kim, Reference Kimforthcoming), and the situation is likely similar in other airlines globally. In contrast, all controllers in Korea are Korean civil servants due to security reasons, although some countries do hire foreign citizens as controllers.

Pilots are considered first. Their multiple community memberships depend on their position, profession, and nationality. For instance, a Korean pilot might belong to the community of first officers or captains, while simultaneously holding membership as a pilot at the company level, the national level, and as a Korean pilot within the international aviation community. Within and across these communities, pilots closely interact to practise their profession, whether working with long-term partners or complete strangers in the cockpit. They collaborate as first officers and captains, sharing information and experience among all members. For instance, when unusual or unique features arise regarding certain air routes, airports, or language habits of specific L1 groups, pilots may share relevant information and personal experiences. During flights, first officers and captains collaborate closely, though the captain bears greater responsibility and is relied upon more heavily for expertise and experience. Roles and rules are expected, and as pilots advance in their careers within particular teams, these roles and rules become increasingly routinised and tacitly understood rather than explicitly defined (e.g., Hutchins & Klausen, Reference Hutchins, Klausen, Engeström and Middleton1996). Within these multiple communities, mutual engagement varies in intensity. Among colleagues who operate flights together, engagement is grounded in everyday practice; however, this smaller community may change as their positions and experience evolve over time.

Controllers, like pilots, also have multiple and overlapping community memberships. However, their communities typically maintain more stable relationships at the local level, with members familiar with each other’s career trajectories. Controllers belong to the team with which they work most closely, the associated air traffic control unit (ground, approach, or en route control), and the broader controller community. Extensive coordination is required as air traffic control and radiotelephony communication are handed over from one unit to another. Controllers working in en route units in Korea, for example, actively interact with counterparts in neighbouring countries such as China, Japan, and North Korea for coordination purposes. Furthermore, smaller, hierarchically arranged communities of practice exist within each unit, including trainee controllers working under supervision until they obtain full certification, colleagues working within or across teams, team leaders, and supervisors overseeing entire units. Given this hierarchical structure, when unusual or unexpected situations arise, less experienced controllers can seek assistance from more experienced colleagues, team leaders, or supervisors.

As both pilots and controllers collaborate closely in flight operations and air traffic control – a dynamic not depicted in Figure 1 – they form a distinct community of practice, characterised by intensive, though non-face-to-face, radiotelephony communication. The practices of each group are closely interwoven. Pilots operate flights based on instructions or information received from controllers throughout all flight phases, communicating with multiple controllers from departure to arrival. Controllers, meanwhile, manage air traffic within their units and may simultaneously handle numerous aircraft from various countries. They issue instructions to pilots and sometimes request information to ensure safe and efficient air traffic control. Since their interaction is never face-to-face, it presents a significant challenge because one aspect of communication, nonverbal communication, is unavailable. Nonverbal communication can sometimes repeat, conflict with, complement, substitute, accentuate, or regulate verbal communication; thus, its absence can affect the completeness and effectiveness of communication (Knapp et al., Reference Knapp, Hall and Horgan2014). Consequently, strict adherence to radiotelephony procedures and conventions is essential for safety and efficiency. This form of communication relies on standard phraseology in routine situations, a specialised language developed for radiotelephony, which includes acronyms and technical jargon (see Section 2.3.2 for further details).

The system of radiotelephony communication practised by the pilot and controller is highly rigorous, involving well-defined and strictly regulated duties, roles, and language use (e.g., Varantola, Reference Varantola1989). Violations of these duties and roles result in sanctions, such as letters issued to the associated airline or government agency detailing the nature of the violation. When flight operations or air traffic control procedures deviate from routine – that is, during unexpected or abnormal situations – departures from established protocols become more likely. Nevertheless, even in these abnormal circumstances, expected duties and roles associated with the broader community of practice remain, allowing members to judge the appropriateness of behaviour in context.

Differences do exist across the various communities to which pilots and controllers belong. While the core dimensions of practice are shared across the entire international community at the broadest level, particular values and norms may be shared and appreciated only within certain narrower communities. For this reason, the traits of specific national aviation communities of practice – including work culture, character, and language use habits – are often noted by members of the international community. Moreover, there is not always consensus on how such characteristics are evaluated. Certain practices within the American aviation community of practice are often criticised for their habitual violation of radiotelephony conventions (e.g., Hawkins & Orlady, Reference Hawkins and Orlady2017; Kim & Friginal, Reference Kim and Friginal2026), due to differing and potentially conflicting conceptions and levels of awareness among its members. These differences stem from individual experience, expertise, L1s, attitudes, and the organisational cultures of the smaller communities to which pilots and controllers belong.

2.2 Learning in Practice and Changing Identities

Learning through practice and evolving identities along trajectories are core concepts within the community of practice framework (Lave, Reference Lave2019; Lave & Wenger, Reference Lave and Wenger1991). As newcomers join a community of practice, their learning begins through legitimate peripheral participation. Legitimacy signifies their belonging to the community; as members, they engage in and perform their roles while assuming their share of responsibility. Lave and Wenger (Reference Lave and Wenger1991) stress that the concept of the periphery should be understood from the structural perspective of communities of practice. With experienced members or old-timers (e.g., captains) participating more fully, peripheral members learn and advance towards greater participations, and in doing so, their identities also change – for example, from individuals who learn a particular skill through practice to individuals who have experience in that skill. In the longer term, their participation within the community of practice increases. To illustrate this within the pilot community of practice, the description by one pilot informant who participated in the study by Kim and Friginal (Reference Kim and Friginal2026) of his first communication with Mumbai and Colombo controllers as a first officer, and how he learned from a senior captain in the cockpit, is revealing – in this case, in a quite explicit way:

We have to talk to Mumbai and Colombo a lot … If you don’t know what to expect, when they talk to you, trying to ascertain what they are asking for is really difficult … my first flight across, I hadn’t done that particular procedure on the HF [High Frequency] before. I was flying with the captain; I was on the radio … Mumbai contacted us and the accent was so thick … I looked straight at the captain. I was like, ‘oh … I’m sorry I didn’t. Did you? Did you catch any of that?’ And because he had heard it before a hundred times, and he knew exactly what they’re asking for. I think that knowing what to expect in that situation really facilitated his understanding of what they were trying to achieve on the radio. So he was like, ‘just watch me do the first one, and then you can do so.’ He did. He talked to Colombo and Sri Lanka on the radio, and then said, ‘yeah, this is the format you do use for the HF position report’ and then and after that, talking to Mumbai, it was so much easier to understand what they were asking. And even though the accent was quite thick.

This pilot informant described the encountered situation – a procedural report communicated via high-frequency radio – that was complicated by unfamiliar accents. Learning occurred through practice while participating alongside a more experienced senior member in the cockpit. With his accumulated knowledge and skills from performing similar tasks, his understanding developed relatively quickly. As illustrated by this example, pilots gain experience through everyday practice, and their identities evolve into those of individuals capable of managing such situations; this process is understood as learning (Lave, Reference Lave2019).

When learning is understood this way, it becomes clearer that the communities of practice framework originates from a social theory of learning. Lave (Reference Lave2019) argues that learning is a social process that occurs through interaction, rather than an individual process taking place solely within the mind of the learner, as is traditionally and more commonly understood in psychology. The author further explains that situatedness, or context, is crucial for learning, and experiencing it within its situated context is what defines apprenticeship. In the context of the anecdotes illustrated over Mumbai and Colombo earlier, the pilot informant’s learning is not something that could be acquired in advance, such as during a pre-flight briefing. It becomes meaningful only within the situated context, given the complexity of the challenges compounded by the peculiarity of that specific airspace and the unfamiliar accents. Citing Coy’s introductory chapter on the theory of apprenticeship, which describes apprenticeship training as ‘personal, hands-on, and experiential’ (Coy, Reference Coy and Coy1989, p. 1), Lave (Reference Lave2019) emphasises the practice aspect, noting that apprentices, or legitimate peripheral participants, are becoming skilled practitioners within specialised occupations. This process of apprenticeship involves more than socialisation – for example, all children are socialised within a given society – but entails learning specialised skills and knowledge through practice. A practice is ‘a way of doing things, as grounded in and shared by a community’ (Eckert & Wenger, Reference Eckert and Wenger2005, p. 583), and through apprenticeship, not only knowledge and skills but also ‘appropriate deportment, shared assumptions, behaviours and values (i.e., culture)’ (Cooper, Reference Cooper and Coy1989, p. 137) are transmitted.

The cultures of the communities of practice to which pilots and controllers belong are situated at both local and international levels, with the local level influencing the international level. Although differences and conflicts can arise within local communities, they are generally more manageable compared to those found in the international community. When unshared cultural elements present challenges, bridging these differences may be more difficult due to the greater diversity and potential conflicts among the many aggregated communities within the global context. Nevertheless, the international aviation community of practice as a whole shares a clear common goal: safe and efficient flight operations.

2.3 International Aviation Community of Practice

This section provides a closer examination of the international aviation community of practice. Pilots and controllers interact in a unique manner – exclusively through radiotelephony. While they engage in face-to-face practice within their local communities, such as in the cockpit and the associated air traffic control unit, they simultaneously communicate over radio, which constitutes the international context of their community. ICAO specifies rules and procedures for radiotelephony communication; thus, these are intended to form a shared culture, a way of doing things. However, differing values, interpretations, language backgrounds, and work cultures challenge this ideal, resulting in gaps and conflicts. These issues are explained in turn.

2.3.1 Environmental Challenges

As briefly mentioned in Section 2.1, the non-face-to-face communication environment itself poses many challenges due to the absence of aiding non-verbal cues. Moreover, aircraft noise and equipment-related sounds add an additional layer of complexity to this environment, making clear communication even more challenging. As noise levels increase, intelligibility decreases, particularly when communication relies solely on auditory cues rather than on both auditory and visual cues, as is the case in radiotelephony (Hawkins & Orlady, Reference Hawkins and Orlady2017). Since English is a global lingua franca, do aviation communities with English L1 pilots and controllers have an advantage in radio communication and are they less vulnerable to challenges in this environment? Studies show that it is not the case. While the benefit of a shared L1 has yielded mixed results in studies (e.g., Bent & Bradlow, Reference Bent and Bradlow2003; Major et al., Reference Major, Fitzmaurice, Bunta and Balasubramanian2002), Adank et al. (Reference Adank, Evans, Stuart-Smith and Scott2009) demonstrated that familiarity with a particular accent plays a significant role under noisy conditions. Their participants from Glasgow, who were familiar with both Received Pronunciation (e.g., through media) and Glaswegian accents, showed comparable comprehension in both normal and noise conditions. In contrast, participants from Greater London, who were familiar only with Received Pronunciation, exhibited slower responses in noise conditions. Some studies have focussed on the distinction between ‘native’ and ‘non-native’ speakers in terms of intelligibility and perception (e.g., Molesworth et al., Reference Molesworth, Burgess, Gunnell, Löffler and Venjakob2014; Shimizu et al., Reference Shimizu, Makishima, Yoshida and Yamagishi2002; van Wijngaarden et al., Reference van Wijngaarden, Steeneken and Houtgast2002), showing that noise conditions tend to affect L2+ users more adversely.

In pilot-controller interaction, Tiewtrakul and Fletcher’s (Reference Tiewtrakul and Fletcher2010) study on accent effects, based on radiotelephony discourse from Bangkok international airport, where controllers are all Thai L1 speakers, found a shared L1 advantage: communication between Thai pilots and controllers involved fewer errors, followed by interaction with English L1 pilots, and then non-Thai L2+ pilots. While emphasising the critical impact of accents, the authors recommend more rigorous training for L2+ pilots and controllers. However, this distinction between ‘native’ and ‘non-native’, commonly found in second language acquisition studies – which often focus on how ‘non-native’ English use differs from that of so-called ‘natives’ – can also be interpreted in terms of familiarity and unfamiliarity. In ELF contexts, this distinction is largely irrelevant and unhelpful, as shared understanding and mutual responsibility for the success or failure of communication are paramount, regardless of speakers’ L1s or ‘native’ status (Kim & Billington, Reference Kim and Billington2018; Kim & Elder, Reference Kim and Elder2009). Instead, the ability to manage a variety of accents – whether this is more challenging or easier – can serve as a valuable measure of communicative competence in these contexts. Research on the benefit of familiarity with different accents, particularly through long-term exposure, is illuminating in this regard, as evidenced by studies conducted in settings such as Hong Kong (Tauroza & Luk, Reference Tauroza and Luk1997) and the US (Smith & Nelson, Reference Smith, Nelson, Nelson, Proshina and Davis2020). Smith and Nelson’s study shows that intelligibility (recognising words and utterances) was easier for the participants than comprehensibility (understanding meaning) and interpretability (inferring intended meaning). Although the English L1 group performed better in comprehensibility, the group more familiar with diverse English accents was better at accurately interpreting interactions. The authors highlight that increasing varieties of English do not hinder understanding, provided users develop familiarity with them.

2.3.2 Shared Repertoire among Members

To address environmental challenges in radiotelephony communication and the complexity of interactions between pilots and controllers, standard phraseology was developed. ICAO’s (1996) nine basic principles of phraseology can be summarised as follows: (1) English should serve as the basis; (2) selected words and phrases must ensure optimum transmissibility without risk of misinterpretation; (3) words and phrases prone to pronunciation variations should be avoided; (4) commonly used spoken Q codes, such as QFE and QNHFootnote 1, may be preferred over lengthy or complex phrases; (5) phrases proven phonetically effective across languages should remain unchanged; (6) new phrases should be clear, unambiguous, and concise without sacrificing clarity for brevity; (7) phrases should convey a thought in natural language using the simplest grammar; (8) positive and negative instructions should be clearly distinguished; (9) where possible, avoid words with sounds or syllables difficult for ‘non-native’ English speakers to pronounce. In short, clarity, resistance to misinterpretation, and maximum transmissibility are of paramount importance. Currently, the ICAO standard phraseology (ICAO, 2007) comprises 553 phrases, with 231 allocated for tower control (e.g., report when ready for departure) – including 28 for airport ground vehicle or crew service –, 209 for approach control (e.g., FL80 estimating north cross 46 information delta), and 113 for en route control (e.g., stop descent at FL150) (Kim & Zhang, Reference Kim and Zhangforthcoming). In the literature, standard phraseology is described as the most successful semi-artificial international language (Robertson, Reference Robertson1987), a purpose-built language (Varantola, Reference Varantola1989), or a codified language (Philps, Reference Philps1991). Robertson highlights the difficulty that English L1 pilots and controllers face in strictly adhering to standard phraseology, as natural English is often easier and more convenient to use. He notes:

Standard behaviour does not come naturally––even on the purely procedural, as opposed to the linguistic, side, complaints about sloppy RT [radiotelephony] discipline are commonly heard … Natural languages are never static, their users impose change continuously … RT phraseology goes against nature and has to counter the same influences which are otherwise given free rein in natural language. (p. ix).

Similarly, Varantola (Reference Varantola1989) notes that L2+ pilots and controllers find it easier to use standard phraseology because they learn the code and use it in context with less interference, whereas English L1 pilots and controllers must consciously distinguish between the code and the natural language they use in other contexts. For this reason, Estival (Reference Estival, Farris and Molesworth2016, Reference Estival2025) argues that English L1 pilots and controllers need to learn and practise standard phraseology as if it were a second language.

The deletions and omissions (e.g., subjects, linking verbs, or prepositions) typical of phraseology sub-grammar are possible because the language is embedded within referential meanings specific to the flight phase and air traffic control context, rendering certain elements redundant (Philps, Reference Philps1991). Additionally, at the surface level, even a simple list of phrases within a single transmission (e.g., four noun phrases in juxtaposition – runway 35, wind 340 degrees 10 knots, QNH 1008, no traffic) can be meaningful without causing confusion, as the messages are conveyed within well-defined operational and procedural contexts (Kim & Zhang, Reference Kim and Zhangforthcoming).

To ensure clarity over radio, numbers such as those for flight levels and radio frequencies are pronounced according to specific guidelines. Notably, distinctive pronunciations include three as [triː] and thousand as [taʊzənd], due to the difficulty some users have in pronouncing the voiceless dental fricative /θ/; and five as [faɪf] and nine as [naɪnər] to avoid phonetic confusion (Philps, Reference Philps1991), as the initial and final sounds in [faɪv] and [naɪn] in natural English can become indistinct in noisy conditions (Trippe & Baese-Berk, Reference Trippe and Baese-Berk2019). Similarly, airport names and geographical points on the map are coded using letters from the phonetic alphabet to avoid ambiguity caused by variations in pronunciation (e.g., a for alpha, b for bravo … y for yankee, and z for zulu). The most notable conventions are readback and hearback. Messages provided by the controller must be repeated by the pilot to ensure that the instructions are correctly received; this procedure is called readback. The controller then listens to verify whether the messages read back by the pilot are correct. This procedure is known as hearback. During the hearback process, if a pilot’s partial or incorrect understanding is detected, the controller is required to correct it (e.g., by using the phrase negative, I say again …).

The readback and hearback monitoring practices embedded in radiotelephony communication serve as pre-emptive systems to prevent misunderstanding or lack of understanding. The hearback procedure is particularly important, as it can alter the pilot’s understanding of the situation; without it, the pilot would rely solely on their own perception. This likely explains why studies in the US have focussed on nonroutine communication, where repetition of the initiate-readback process through the controller’s hearback is necessary. Focussed on live radiotelephony discourse from multiple air traffic control units in the US, studies – 48 hours of tower control recordings in Burki-Cohen (Reference Burki-Cohen1995), 42 hours of approach control in Morrow et al. (Reference Morrow, Lee and Rodvold1993), and 47 hours of en route control in Cardosi (Reference Cardosi1993) – show that the readback error was remarkably low, at less than 1 per cent. While this low rate of noncompliance is reassuring in routine transmissions, it is crucial to recognise that a single piece of unclear information could have catastrophic consequences in air traffic control. Consequently, all studies emphasise the importance of pilots and controllers strictly adhering to readback and hearback procedures. Readback errors were more likely to occur when a single transmission contained multiple pieces of information (e.g., number, direction, altitude, and location) (Burki-Cohen, Reference Burki-Cohen1995; Cardosi, Reference Cardosi1993) and involved two speech acts (e.g., directive and request) rather than just one (Morrow et al., Reference Morrow, Lee and Rodvold1993). With particular emphasis on compliance with standard phraseology, Howard (Reference Howard2008), based on an analysis of 15 hours of radiotelephony discourse, notes that deviations from standard phraseology and conventions are critical precursors to communication problems, as they inherently violate system rules and interlocutor expectations.

Drawing on the same recordings from their earlier study, Morrow et al. (Reference Morrow, Rodvold and Lee1994) conducted further analysis to investigate the reasons for deviations from procedures. Two main reasons were identified: limited air traffic conventions for resolving communication problems when they arose and a lack of flexibility in these conventions for addressing nonstandard topics. The findings indicated that communication became nonroutine primarily during the acceptance of previously presented information, rather than when presenting new information. In such cases, both pilots and controllers tended to use natural English. When communication deviated from prescribed procedures, more complex syntax, nonstandard terminology, abbreviations, and context-dependent referring expressions were employed. Accordingly, the authors made three recommendations: (1) pilots and controllers should adhere to standard procedures and conventions; (2) standard procedures for nonroutine communication should be developed; and (3) training emphasising collaborative principles should be implemented. These recommendations are particularly relevant to the discourse analysis informed by insights from domain experts and will be further discussed in Section 4.

2.3.3 Unshared Repertoires among Members: Managing Variation

Variation in the individual resources that pilots and controllers bring to interactions in the international radiotelephony communication context poses challenges in this professional setting. Since pilot-controller interactions are prescribed, routinised, and proceed as expected in routine situations, such variations are unlikely to be noticeable. However, in abnormal situations, such as when an aircraft experiences a problem that does not affect its normal operation (e.g., a sick passenger on board or a diversion due to fuel shortage), or during emergencies, such variations emerge and play a significant role. For instance, a controller under close supervision may communicate with a pilot who has decades of international experience and benefit from the pilot’s expertise in managing abnormal situations as they unfold through communication. An L2+ first officer flying into Sydney for the first time may appreciate accommodations made by an English L1 controller, such as a slower speech rate, in response to the pilot’s perceived inexperience or unfamiliarity with the airport or accent. Conversely, a captain with substantial international experience but new to flying into New York may struggle to understand colloquial expressions used by controllers speaking rapidly during commonly occurring abnormal situations. These variations, referred to here as unshared repertoires in contrast to the shared ones discussed in the previous section, present challenges that pilots and controllers must manage to ensure effective collaboration, often emerging in complex and interconnected ways.

One notable variation is the use of plain language – specifically, plain English – referring to both the language spoken on the ground and English – when standard phraseology is unavailable, such as in abnormal or emergency situations. In these contexts, English use shifts from specialised language (i.e., standard phraseology) to English as a global lingua franca. ICAO (2010) offers somewhat contradictory explanations regarding plain language: on one hand, it states that it should be delivered in ‘the same clear, concise, and unambiguous manner as standard phraseology’ (p. 4–2); on the other, it describes plain language as ‘the spontaneous, creative, and non-coded use of a given natural language’ (p. 6–6). While the former emphasises restricted use, the latter highlights natural use. As a result, there is considerable variation in how individual pilots and controllers interpret plain English. Due to accessibility issues, however, there is a lack of studies focussing on abnormal or emergency situations. Some literature on emergency situations is available because accidents have occurred, drawing attention to these extreme cases. These cases often involve numerous factors throughout the unfolding events, which will be discussed in Section 3.

This section focusses on three intertwined variations observed in pilot-controller communication during abnormal situations, which pilots and controllers need to manage in aviation ELF contexts, as identified in my earlier studies: the use of plain English, experience and expertise, and accent familiarity. Experienced pilots and controllers served as informants in relevant studies, providing evaluations and interpretations of these scenarios. Elder et al. (Reference Elder, McNamara, Kim, Pill and Sato2017) provide a well-argued discussion on the contributions non-language specialists can make to the constructs of communicative competence. They illustrate this through examples from two professional fields, healthcare (see Elder & McNamara, Reference Elder and McNamara2016; Pill, Reference Pill2016) and aviation, as well as one general context (see also Sato & McNamara, Reference Sato and McNamara2019). Their discussion raises important questions about how narrowly language-focussed assessments, though valid from the perspective of applied linguists, may lack meaningfulness for professionals in real-world settings. A further question concerns whether such assessments are valid at all. Although exploring domain specialists’ perceptions in professional contexts is not new, when these perceptions are linked to discussions of the validity of communicative constructs, the issue becomes essential rather than optional. Thus, the studies summarised in the following are particularly significant because experienced pilots and controllers, language users themselves in the international radiotelephony communication context, served as informants to evaluate naturally occurring peer performance.

Kim and Elder’s (Reference Kim and Elder2009) study examined an abnormal situation involving a fuel shortage on a Cathay aircraft, with discourse between an American pilot and a Korean controller. Six experienced Korean aviation specialists served as informants. Due to fuel overconsumption, the American pilot initially requested a diversion to Shanghai, later changing it to Osaka while in Korean airspace. The informants noted that the pilot’s transmissions were often unclear, indirect, excessively fast, and noncompliant with radiotelephony conventions, which they identified as typical of many English L1 pilots and controllers. For example, when requesting the diversion, the pilot said: Roger sir, due to operational requirement we’re having to divert and diversion port will be Shanghai. If you could er … liaise with Shanghai ATC and request vector for landing in Shanghai, please, Cathay 883. The informants suggested this could have been simplified to ‘request a diversion to Shanghai’. Similarly, when the Korean controller asked for the reason for diversion, the pilot said: Cathay 883, due to strong head wind, we do not have enough fuel to reach Hong Kong, weather in Taipei is not suitable for landing. Our company would like us to go to Shanghai to refuel, Cathay 883. The informants recommended a concise explanation such as ‘due to fuel shortage’. The use of four-letter ICAO airport codes is standard to avoid confusion, especially since Shanghai has two international airports. The informants noted that the pilot should have used these codes instead of the city name. For example, Pudong airport is Zulu Sierra Papa Delta and Hongqiao airport is Zulu Sierra Sierra Sierra. This omission continued when the pilot changed the destination to Osaka (Romeo Juliett Bravo Bravo). Regarding the Korean controller, missed understanding and noncompliance with radiotelephony conventions were also observed. While attempting to clarify whether the destination was Hongqiao or Pudong, the controller failed to recognise the change to Osaka and repeatedly asked which Shanghai airport was intended. This was resolved only after the pilot specified RJBB, the ICAO code for Osaka. Additionally, the controller did not use the five-letter code, the navigational point RUGMA, which the pilot could not locate on the map, leading to extended exchanges to clarify its spelling.

The evaluations provided by the Korean domain specialist informants were consistent with those from a later replication study by Kim and Friginal (Reference Kim and Friginal2026), which used the same audio recording but involved ten Australian domain specialist informants. The Australian informants evaluated the Korean controller more positively, emphasising his handling of the fast-speaking pilot who failed to deliver clear and direct messages, as well as the overall success of the communication. The shared values among aviation domain specialists, regardless their L1 backgrounds, concerning communication priorities and language delivery are revealing. However, the extent and degree of restriction or liberty in the use of plain English required or permitted in radiotelephony communication remain unclear due to the absence of guidelines and thus depends on individual perceptions. For instance, while the Korean informants unequivocally criticised the American pilot’s verbosity, one Australian controller informant considered the American pilot’s plain English use acceptable. This Australian informant also evaluated the Korean controller as lacking confidence in his use of plain English. It appears that the Korean informants, and potentially including others in L2+ communities, tend to adopt a more rigid view emphasising conciseness. In contrast, the Australian informants, and possibly others in English L1 communities, while also valuing simplicity and clarity, adopt a more flexible approach. This unresolved variation is critical in the international aviation community of practice, as individual perspectives shape local cultural norms that are transmitted to junior members, potentially perpetuating undesirable practices.

In addition to message delivery, the Korean informants deemed the American pilot’s unnecessary intervention in the controller’s role by instructing him to coordinate with other controllers inappropriate. Similarly, the Australian informants judged the pilot’s premature contact, made before his airline finalised a decision that led to a change of alternate destination, as inappropriate. Consequently, both the American pilot and the Korean controller were evaluated as inexperienced in dealing with such abnormal situations. These evaluations reveal that expertise and experience influence communication efficiency, including when to initiate contact and what information to convey. Another study by Kim (Reference Kim2018) of a different abnormal situation further demonstrates that experience and expertise significantly affect the success or failure of managing such events.

The recording analysed in Kim (Reference Kim2018) involved a Russian pilot from Vladivostok airlines flying from Pattaya, Thailand to Incheon, Korea, and a Korean controller. Six experienced Korean pilots and controllers served as informants. The Russian pilot requested a diversion to home country due to a technical problem, requiring the controller to coordinate controllers in North Korea and Russia. Although the Russian pilot was evaluated as having limited English proficiency, his strategy of listing the proposed alternate route was highly praised by the informants. This effort, however, proved futile, as the Korean controller was unfamiliar with air routes to neighbouring countries. The controller’s continued use of plain English phrases, such as let me know …, I want to know exact route of flight …, what’s the name of fix (fix: geographical point) or let me check and see and call you again (which could have been replaced with standard phraseology ‘standby’), did not facilitate the Russian pilot’s immediate comprehension of the messages. Most notably, the informants noted the ambiguity of the controller’s language; for example, the phrase what’s the name of fix was unclear because the controller did not specify whether he was asking for the geographical point of the airway or the point the aircraft would take after using the named airway. This ambiguity, the informants explained, stemmed from the controller’s lack of knowledge of air routes and his unpreparedness to manage such an abnormal situation. The informants further observed that the controller’s use of general English was intended to be recognised ‘superficially and falsely, as competent’ (pp. 416–417), as one informant noted. Furthermore, the informants criticised the controller’s enquiry concerning a fuel issue, not because the question itself was inappropriate, but because it was posed without first clarifying and resolving the air routes, which were the priority for both parties. Despite the extended twenty-six turns regarding the air route, it remained unconfirmed until the end of transmission, leaving confirmation to the pilot in North Korean airspace. This reflects professional unreadiness, demonstrated by a lack of necessary knowledge for the controller’s role and an inability to prioritise among competing issues, all of which undermine communication efficiency.

In addition to the controller’s lack of professional knowledge, his habitual misuse of terms such as affirm (meaning ‘yes’), roger (meaning ‘I have received all of your last transmission’), or wilco (meaning ‘I understand your message and will comply with it’) – using them without fully understanding the pilot–, his noncompliance with radiotelephony conventions, specifically failing to confirm the route listed by the pilot, and his inability to rephrase questions when the pilot did not understand were identified as factors contributing to the Russian pilot’s difficulties.

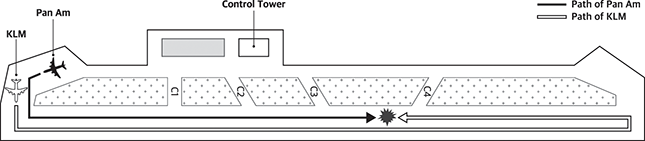

One final abnormal situation involved a runway incursion between a French pilot and a Korean controller, attributed to the influence of L1 phonology on the production and comprehension of instructions, combined with contextual factors, as discussed in Kim and Billington (Reference Kim and Billington2018). Six experienced aviation specialists provided their evaluations of this incident. Specifically, during the turn in which the Korean controller instructed the French pilot to move slightly towards the holding position during the departure phase, the instruction Air France 267, taxi forward and hold short 16 was given. However, the French pilot’s readback was position and hold runway 16, Air France 267. The phrase position and hold, developed by the Federal Aviation Administration in the US to mean ‘taxi onto runway and wait on the runway’, is no longer recognised as standard phraseology by ICAO. Consequently, although the controller intended for the pilot to wait on the taxiway and hold position, the pilot interpreted the instruction to taxi onto the runway, leading to a runway incursion. The informants provided evaluations on three aspects. First, they identified the pilot’s incorrect readback and the controller’s failure to detect it, constituting noncompliance with radiotelephony conventions. Second, the informants noted that contextual factors likely influenced the pilot’s expectations. Specifically, the pilot had been informed by the controller that their take-off time would be 51 minutes, which was confirmed in previous exchanges. Hearing the instruction near 50 minutes may have led the pilot to interpret it as clearance to enter the runway. The informants observed that both the controller and pilot heard what they expected to hear, resulting in the controller not correcting the readback and the pilot entering the runway. Third, regarding linguistic challenges, the informants highlighted the difficulty Korean speakers face distinguishing between the sounds of [f] and [p]. They suggested that the [f] in forward within the controller’s instruction was likely perceived as [p] by the pilot, causing the pilot to repeat the phrase as position and hold.

Building on the third aspect identified by the informants, Kim and Billington (Reference Kim and Billington2018) conducted an acoustic analysis using Praat. Their results suggest that substitution of [p] for [f] was unlikely to have caused the misinterpretation. However, the controller’s pronunciation of taxi [tʰeɕɪ], which differs from pronunciations in other more common English varieties, may have been perceived by the French pilot as the final two syllables of the word position (e.g., [pəˈzɪʃən] in American English). Additionally, the controller pronounced forward as [fɔɭwɜɹdə], with the final consonant of the first syllable realised as retroflex lateral [ɭ] rather than the approximant rhotic [ɹ], a common feature of Korean phonology. The controller’s pronunciation also exhibited characteristics similar to those found in various English pronunciations of hold (e.g., [hoʊld] in American English). Thus, L1 phonological influences clearly affected both the production and perception of the relevant exchanges. Based on these analysis and findings, Kim and Billington (Reference Kim and Billington2018) recommend that all pilots and controllers be aware of the features of their L1 phonology that could affect their speech productions and develop appropriate strategies to enhance intelligibility in radiotelephony communication (see also Section 2.3.4).

The four studies discussed previously demonstrate that understanding radiotelephony communication requires considering multiple interconnected factors, including situational context, experience and expertise, behavioural motives (or strategy adoption), and language-related aspects such as English proficiency and L1 phonology. As with routine radiotelephony communication discussed in the previous section, compliance with radiotelephony conventions is prioritised irrespective of L1 backgrounds, not only because it is required, but because it clarifies communication and allows mutual understanding to be confirmed within systematised conventions. However, some English L1 and proficient L2+ pilots and controllers use plain English that is insufficiently concise, clear, and direct, which can hinder safe and efficient communication. One Australian controller informant highlighted the importance of standard phraseology use, noting that ‘[t]here is a high chance of misunderstanding, irrespective of the proficiency in English of either person … the use of plain language in a scenario has a likelihood of creating errors’ (Kim & Friginal, Reference Kim and Friginal2026). Similarly, a Korean informant remarked on the American pilot’s habitual general English, stating ‘[t]his pilot speaks English very well but he is not the one who does well in air traffic communication’ (Kim & Elder, Reference Kim and Elder2009, p. 23.11). The importance of adhering to standard phraseology and radiotelephony conventions is emphasised throughout the literature. However, this is not always realised in practice due to differing individual perceptions and more critically, ICAO’s emphasis on English proficiency in a general sense (see Section 3.1 for details), which has reinforced the misconception that ‘native’ or ‘native-like’ proficiency represents expert competence in radiotelephony communication.

To manage the variations that inevitably arise in radiotelephony communication – such as differing levels of English proficiency, experience and expertise, and various accents – accommodation skills are essential. These skills are primarily developed through practice with both English L1 and L2+ individuals, often with more experienced seniors who recognise the value of collaborative effort for successful communication. However, current ICAO policy places responsibility solely on L2+ pilots and controllers to improve their general English proficiency, while disregarding the contributions that English L1 pilots and controllers can and should make. This approach increases the risk of unsafe and inefficient communication. Raising awareness of the importance of actively developing accommodation skills is urgent, and incorporating targeted training would significantly enhance air safety. Currently, no formal training exists; the global industry relies mainly on experienced individuals to mentor junior members within communities of practice. Insights can be gained by turning to accommodation research in ELF in other contexts, which will be discussed next.

2.3.4 Accommodation to Narrow Gaps in Unshared Repertoires: Insights from ELF Research in Other Contexts

ELF is a growing area of research, and accommodation is recognised as a core skill in ELF communication contexts (e.g., Jenkins, Reference Jenkins and Walkinshow2022; Kim & Penry Williams, Reference Kim and Penry Williams2021; Seidlhofer, Reference Seidlhofer2009). As briefly described in Section 2, interactants introduce variation into interactions through their own linguistic and strategic repertoires, shaped by their communication experiences and practices. Sensitivity to such variation, as well as the ability to adjust one’s language to align with others, is therefore essential. This process, known as accommodation, originates from Communication Accommodation Theory (Giles, Reference Giles and Giles2016; Giles et al., Reference Giles, Coupland, Coupland, Giles, Coupland and Coupland1991). Three strategic concepts involve accommodation: convergence, divergence, and maintenance. Convergence involves speakers adjusting their communicative behaviours to more closely align with their interlocutors, while divergence entails becoming more dissimilar to the interlocutor and maintenance involves retaining one’s original communicative behaviours without adjustment (Dragojevic et al., Reference Dragojevic, Gasiorek, Giles and Giles2016).

Early studies on accommodation are found exclusively in L1 communication, focussing on affective motives related to retaining or projecting identity. For example, a classic study by Bourhis and Giles (Reference Bourhis, Giles and Giles1977) demonstrates that Welsh-born English speakers who were genuinely motivated to learn Welsh converged towards an English speaker with Received Pronunciation during normal communication. However, when the English speaker made dismissive comments about the Welsh language, they diverged in both accent and content to assert their Welsh identity. Speaker attitudes towards perceived prestigious varieties also influence accommodation choices. Chakrani’s (Reference Chakrani2015) study in a US diasporic setting examined five speakers of different Arab varieties. Sudanese and Moroccan Arabic speakers, whose varieties were perceived as less prestigious, accommodated more towards Saudi, Jordanian, and Egyptian Arabic speakers, whose varieties were considered more prestigious. This accommodation involved adopting various phonological and syntactic forms. The author noted that Sudanese and Moroccan speakers were expected to accommodate based on stereotypes and perceived status hierarchies. However, when the Egyptian speaker expressed negative attitudes towards the Moroccan variety, the Moroccan speaker explicitly diverged by adopting Moroccan expressions. This, in turn, influenced the Sudanese speaker – another representative of a less prestigious variety – who displayed aversion through facial expressions and interruptions, even as he linguistically converged towards the Egyptian speaker. Thus, the perceived prestige of a variety (e.g., Received Pronunciation or certain Arab varieties) influences speaker accommodation, but speakers may also seek to preserve their linguistic identity. The role of perceived or assigned prestige in accommodation is particularly relevant to pilot-controller interactions, especially with regard to presumed competence of ‘native speakers’ in radiotelephony communication as designated by ICAO, which places ‘native speakers’ at the highest expert level and exempts them from testing, as previously mentioned. As a result of this tacit power dynamic, some L2+ pilots and controllers feel obliged to accommodate their English L1 counterparts when the latter use not only plain but also colloquial English (see Sections 4 and 5 for further discussion).

Research on accommodation in ELF has primarily focussed on cognitively motivated convergence strategies related to comprehension and communicative efficiency. This review examines studies of ELF interactions that offer insights relevant to aviation ELF in radiotelephony communication. In an early study, House (Reference House2003) recorded a half-hour group discussion between Chinese, German, Korean, and Indonesian students at a university in Germany. Analysis revealed that participants, especially the Asian students, repeated parts of others’ utterances, facilitating processing and reflecting politeness. Solidarity and consensus orientation were also evident through concordant responses such as yes. Notably, the German student rejected the consensus-oriented ‘Asian style’, preferring to maintain her German communication style. In other words, she employed a maintenance strategy to preserve her German identity in communication, although House did not frame this in terms of accommodation. Cogo (Reference Cogo, Mauranen and Ranta2009) observed similar repetition, specifically referring to these as accommodation strategies. She examined the casual interactions of four foreign language teachers in non-classroom settings at a tertiary education institution. The study found that interlocutors’ repetition of parts of their conversational partners’ utterances served as a collaborative strategy, acknowledging understanding, confirming statements, and demonstrating alignment and solidarity within the same community of practice. This was evidenced by overlaps, latching (i.e., no gap between speakers’ turns), and repetitions.

Focussing on how shared understanding is achieved in an ELF academic context, Kaur’s (Reference Kaur2009) study demonstrates how interlocutors collaboratively and through negotiation contribute to mutual understanding by adopting strategies such as repetition, paraphrase, and various forms of confirmation and clarification, initiated by both speakers and recipients as they monitor each other’s comprehension. Problems of understanding are sometimes resolved jointly and at other times pre-emptively through proactive measures. This is possible because participants are acutely aware of the diverse linguistic backgrounds and capabilities present, leading to increased efforts from both parties. In addition to these strategies, Gaete (Reference Gaete2022) identified completing an interlocutor’s utterance as collaborative behaviour; Birlik and Kaur (Reference Birlik and Kaur2020) highlighted the important role of nonverbal strategies, such as nodding and hand-pointing gestures, in contextualising or enhancing verbal input and making understanding visible; and Kaur and Birlik (Reference Kaur and Birlik2021) noted the provision of unsolicited explanations to clarify and improve shared knowledge. While the usefulness of nonverbal strategies recalls the environmental challenges of radiotelephony communication discussed in Section 2.3.1, these findings offer valuable insights for the aviation ELF context, as assigning blame for non-understanding or misunderstanding to only one party is not meaningful in ELF interactions. Furthermore, determining what additional information would aid clarification is closely linked to domain knowledge, while effective delivery of this information depends on experience within the international aviation ELF context.

Creative meaning-making within context and openness to variation among interlocutors are also noteworthy features of interaction. In Seidlhofer’s (Reference Seidlhofer2009) study, which involved student representatives from European universities discussing joint degree programs, a French student’s phrase endangered field was creatively adopted and adapted by Croatian, French, and Swedish students (e.g., endangered programs, endangered disciplines, and endangered activities) to effectively communicate the concept of being at risk as it emerged from their interactions. This acceptance of the creative – or, to some users, awkward – use of the collocation, and the subsequent adoption of these variations, is significant in terms of the participants’ desire to build rapport and maintain conversational flow in the situated context, rather than correcting the awkward usage through, for instance, recasting in subsequent turns. Similarly, in Pitzl’s (Reference Pitzl, Mauranen and Ranta2009) study of a business meeting, creative use of idioms and metaphors was observed. When a Korean company unknowingly distributed a copyrighted image, a German participant used the phrase we should not wake up any dogs, a direct translation of the German idiom ‘schlafende Hunde soll man nicht wecken’ (equivalent to ‘let sleeping dogs lie’ in English), to suggest avoiding further action. This creative expression was successfully understood by all interlocutors, demonstrating effective intercultural communication. These observations reveal that attentiveness to interlocutors’ repertoires, including multilinguals’ L1s, and collaborative efforts to make sense of them can contribute to shared understanding as well as foster appreciation of multicultural ELF contexts.

Regarding intelligibility in ELF contexts, Jenkins (Reference Jenkins2000) identified key phonological features for intelligibility and proposed the Lingua Franca Core. She (Reference Jenkins2000, Reference Jenkins2007) also emphasised that the speakers’ ability to accommodate their pronunciation to interlocutors is crucial in ELF communication. Some scholars (e.g., Gibbon, Reference Gibbon, Dziubalska-Kołaczyk and Przedlacka2005) argue that, due to the diverse influences of L1 phonologies on production, a universal set of phonological features intelligible to all speakers in ELF contexts is unlikely. Indeed, the case study by Kim and Billington (Reference Kim and Billington2018), summarised earlier, found that word-final consonant clusters, vowel quality, and pitch movement – which are not included in the Lingua Franca Core – contributed to miscommunication leading to a runway incursion. Nevertheless, the Lingua Franca Core has pedagogical value, as it enables the prioritisation of specific features to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of practice. When influential L1 phonological aspects are regularly shared within pilots’ and controllers’ local community as part of their everyday practice – through conversations, experiences, and specific anecdotes – radiotelephony communication can benefit greatly.

One notable ELF study that adopts the concept of a community of practice is Ehrenreich (Reference Ehrenreich2010), which situates its analysis within a business context. The study demonstrates how the history of long-term mutual engagement between interactants influences communication during a 90-second phone conversation. When a German project manager received an update from a Chinese sales manager, the latter’s mix up between two projects was neither corrected nor clarified, yet no misunderstanding occurred, as the German manager correctly inferred what was meant. From their perspective, no issue required resolution. This suggests that a long-standing relationship can itself resolve potential confusion. Additionally, when the author asked the German manager for assistance in transcribing and comprehending the Chinese manager’s utterances, the German manager explained that, although he understood the intended meaning, he could not repeat his colleague’s words verbatim. This highlights how established relationships within a community of practice contribute to both spoken and unspoken communication, including intelligibility and understanding.

In light of the review of ELF research in other contexts, one significant contribution warrants particular emphasis. Supported by evidence from naturally occurring interactions, ELF research offers the potential to reconceptualise communicative competence in diverse ELF contexts. Rather than focussing on individual linguistic ability, competence within ELF is now understood as co-constructed and collaborative. Against the backdrop of shared and unshared repertoires in aviation communication, as well as the essential accommodation skills required in the international aviation ELF setting, the next section examines ICAO’s decision to require ‘non-native’ pilots and controllers to pass an English proficiency test, along with the justification for this requirement.

3 International Civil Aviation Organisation and English Proficiency Requirements

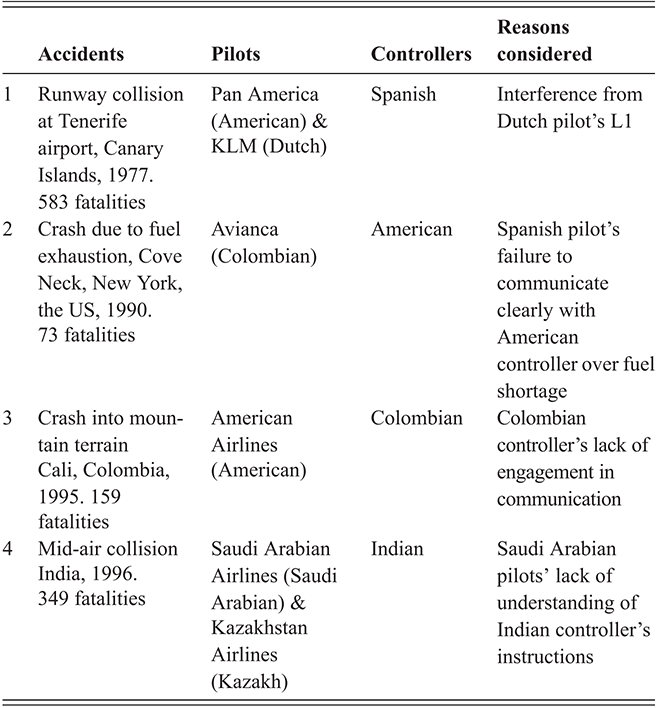

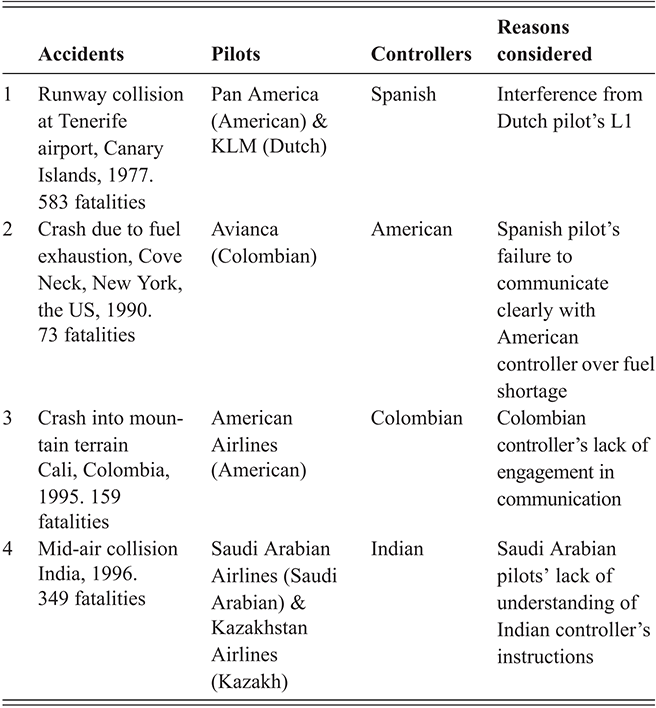

To justify English proficiency testing requirements for ‘non-native’ L2+ pilots and controllers, relevant ICAO manuals (ICAO, 2004, 2010) present four examples of accidents in which, according to ICAO, investigators found that insufficient English proficiency on the part of L2+ flight crews or controllers was a contributing factor in the chain of events leading to the accidents. Additionally, the first edition of the manual (ICAO, 2004) identifies three distinct roles that language played in past accidents and incidents: (1) incorrect use of standardised phraseology, (2) lack of plain language proficiency, and (3) the use of more than one language in the same airspace. Regarding the first role, the second edition of the manual (ICAO, 2010) emphasises the significant role of standard phraseology supported by evidence from a study by Mell (Reference Mell1992), which reported that 70 per cent of all speech acts uttered by English L1 and L2+ pilots and controllers were not compliant with standard phraseology. The second aspect is directly related to the rationale behind the language proficiency requirements, which will be examined more closely in the following section. The third aspect concerns the use of languages normally spoken on the ground (e.g., Korean in Korean airspace); however, as English functions as a global lingua franca, it should be available for communication (ICAO, 2016). The ICAO language proficiency requirements apply to any language used for radiotelephony communication in international operations. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to assume that individual pilots and controllers are proficient L1 speakers of at least one language, typically the language spoken on the ground. Consequently, the language proficiency requirements are generally regarded as English proficiency requirements or testing policy, with the plain language referred to by L2+ pilots and controllers being plain English.

3.1 ICAO English Proficiency Requirements

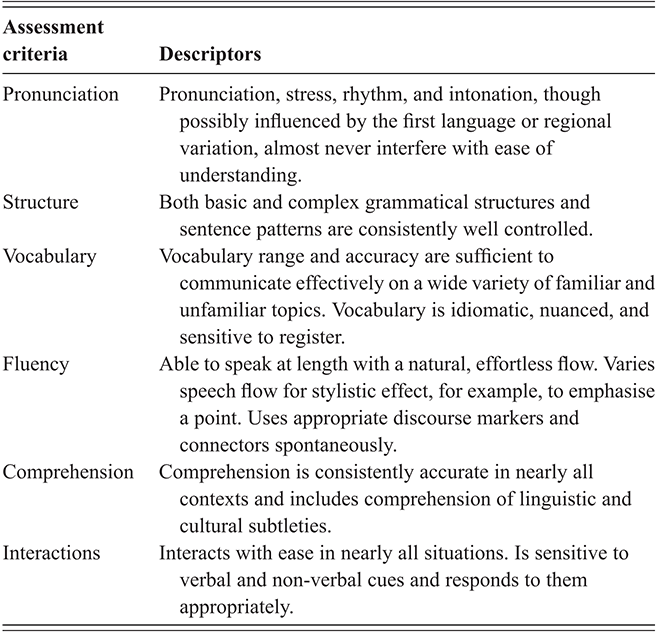

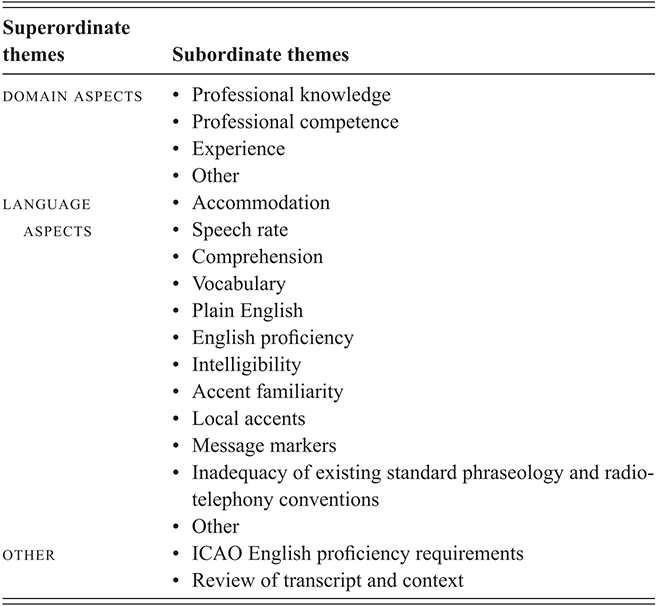

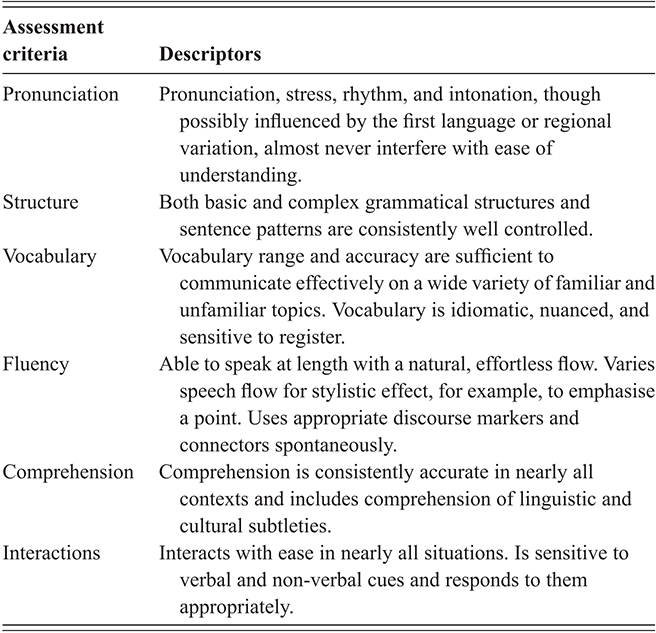

As introduced earlier, there are six assessment criteria across six levels, with the descriptors for the highest expert level 6 shown in Table 1. In a previous paper, I (Kim, Reference Kim, Friginal, Prado and Roberts2024) critiqued the assessment criteria and rating scale, noting that the specific linguistic characteristics of radiotelephony communication are not at all reflected in them.

Table 1Long description

Six assessment criteria (pronunciation, structure, vocabulary, fluency, comprehension, and interactions) are presented as column headings in the first row. Their corresponding descriptions appear in the second row.

In brief, pronunciation and comprehension emphasise ease and accuracy of understanding, treating L1-influenced pronunciations as speaker deficiencies rather than as indicators of respondents’ competence, thereby leaving no room for negotiation between interlocutors. Moreover, by exempting ‘native speakers’, it is assumed that their pronunciation and comprehension never pose problems. Regarding structure and vocabulary, complexity in grammatical patterns and the use of idiomatic or nuanced vocabulary are emphasised, despite these being recognised elsewhere by ICAO as impediments to radiotelephony communication. For fluency and interactions, extended speech and sensitivity to both verbal and non-verbal are highlighted, although these features can hinder or be irrelevant to effective radiotelephony communication. These ICAO descriptors have also been criticised by McNamara (Reference McNamara2010) for being implemented solely for policy purposes and failing to reflect the target domain, and by Fulcher (Reference Fulcher2015) for lacking relevance by focussing on general interactions, arguing that descriptors could apply to any context.

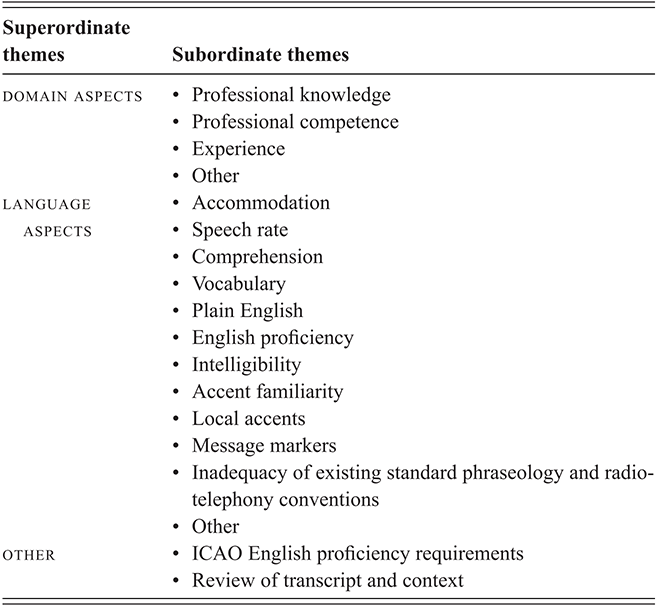

This lack of specificity and relevance to the construct of radiotelephony communication has been further criticised by domain specialists. Knoch’s (Reference Knoch2014) validation study of ICAO’s rating scale with English L1 domain specialists, using recorded speech samples, found that technical knowledge, experience, and training level were the most mentioned categories by pilot experts alongside pronunciation. Kim and Elder’s (Reference Kim and Elder2015) survey revealed that while the great majority of Korean pilots and controllers considered ICAO’s English proficiency requirements, as they stand, to be (completely) unnecessary (69 per cent). The respondents were also negative about the test developed in Korea to meet the ICAO requirements, with 76 per cent indicating that the construct of radiotelephony communication is not well or not at all reflected in the test. Of the assessment criteria, they were particularly critical of the structure and fluency criteria. Kim and Friginal (Reference Kim, Friginal and Allen2025) further discuss these descriptors in terms of construct under-representation and construct irrelevance. Regarding construct under-representation, linguistically valued aspects of radiotelephony communication – such as simple, concise, unambiguous messages, handling various accents, and accommodation – are absent from the rating scale. For construct irrelevance, opposing qualities that may hinder safe radiotelephony communication – such as complex grammatical patterns, idiomatic expressions, and non-verbal cues – are identified as construct irrelevant variance. Due to these shortcomings, the authors argue that the current ICAO English proficiency requirements inevitably produce negative or detrimental washback (i.e., the effect of tests on learning and teaching) for pilots and controllers.