In parliamentary democracies where multiple parties routinely rule together in coalition governments, minority coalitions are often considered puzzling deviations from majority coalitions (Andeweg et al. Reference Andeweg, De Winter and Dumont2011). However, minority coalitions are not as rare as one would expect (Strøm Reference Strøm1990),Footnote 1 and their presence has been more frequent than single‐party minority government since 1980.Footnote 2 Most interestingly, empirical research has demonstrated that minority coalitions perform surprisingly well in policy making and are more stable than what conventional coalition theories would predict (e.g., Cheibub et al. Reference Cheibub, Przeworski and Saiegh2004; Field Reference Field2016; Green‐Pedersen Reference Green‐Pedersen2001; Moury & Fernandes Reference Moury and Fernandes2018; Potrafke forthcoming; Strøm Reference Strøm1990). These findings suggest that minority coalitions can implement their policy agenda in a timely manner and thus govern effectively without holding a parliamentary majority. In this case, how minority coalitions manage to govern effectively and stably becomes a critical yet understudied question for political scientists.

Existing research, which largely focuses on the necessity of external support, argues that policy‐making effectiveness and governing stability of minority governments are conditional on their ability to build legislative alliances with opposition parties (e.g., Falcó‐Gimeno & Jurado Reference Falcó‐Gimeno and Jurado2011; Field Reference Field2009; Green‐Pedersen Reference Green‐Pedersen2001; Klüver & Zubek Reference Klüver and Zubek2018; Strøm Reference Strøm1990). However, this literature has paid little attention to the principal–agent problem embedded in multiparty governance, in which coalition parties pursue different policy interests and the ministerial office‐holder has informational advantages (e.g., Anderweg Reference Andeweg2000; Martin & Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2011; Müller Reference Müller2000; Strøm Reference Strøm2000), which can make minority coalition policy making more complex and difficult. Specifically, even if parties in a minority coalition agreed on a common policy and formed a legislative alliance with an opposition party, the ministerial office‐holder can still drift from previously established agreements by drafting bills that pursue policy interests of her own party (Laver & Shepsle Reference Laver and Shepsle1996). Consequently, both the coalition partner and the external supporter have incentives to scrutinize government bills in the policy‐making process when their policy preferences diverge (e.g., Falcó‐Gimeno Reference Falcó‐Gimeno2014; Kim & Loewenberg Reference Kim and Loewenberg2005; Martin & Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2004, Reference Martin and Vanberg2005, Reference Martin and Vanberg2011; Thies Reference Thies2001). These scrutiny activities attempting to reduce informational deficits, in turn, constitute obstacles that can delay the parliamentary policy‐making process, limit the minority coalition's ability to carry out its pledges and ultimately make minority coalition governance less effective and more vulnerable (Matthieß forthcoming; Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser‐Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017).

While governing in minority coalitions requires policy‐making coordination not only among at least two ruling parties but also with additional parties in opposition, this paper attempts to identify the conditions that make minority coalition policy making more (or less) effective. More precisely, our interests land on the conditions under which government bills of minority coalitions receive less (or more) parliamentary scrutiny from coalition partners and support parties. Our argument focuses on how different patterns of portfolio allocation—defined by the relative ideological locations of the ministerial office‐holder, the coalition partner and the external support party—structure the extent to which government bills are scrutinized in parliament. When the environment is uncertain for future policy making at the time of coalition formation and agreement, we examine whether and how portfolio allocation shape the joint level of parliamentary scrutiny on government bills, and their implications on the policy‐making effectiveness of minority coalitions.

Different from prior work, which assumes that the median party occupies an advantageous bargaining position and can facilitate minority policy making (e.g., Baron Reference Baron1991; Laver & Schofield Reference Laver and Schofield1990; Schofield Reference Schofield1993; Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002), we argue that a minority coalition with the median party on board creates an unbalanced policy‐making structure that may amplify coalition tensions and thus increases the level of scrutiny and reduces policy‐making effectiveness. Since either the median partner or the median minister will attempt to offer policy concessions to an external support party closest to her to move the final policy outcome toward her own party, this configuration creates the highest potential for one‐sided policy‐making bias that may result in a great deal of parliamentary scrutiny. On the contrary, when the median party stays out of the minority coalition, it becomes a decisive actor in parliament since it provides the necessary support in addition to its advantageous bargaining position for implementing government bills.

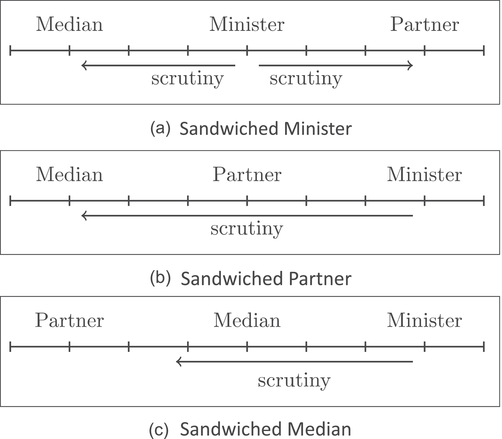

Building on this structural argument, when the median party is not a coalition member, we further distinguish three patterns of portfolio allocation in minority coalitions based on the relative ideological locations of the ministerial office‐holder, the coalition partner and the external support party (i.e., the median party): ‘sandwiched minister’, ‘sandwiched partner’ and ‘sandwiched median party’. Being ‘sandwiched’ means that one actor is ideologically surrounded by the other two actors. We expect that the ‘sandwiched median’ scenario most effectively reduces the risk of ministerial drift and makes government bills more acceptable for all three actors than those in the other two scenarios. Because the ‘sandwiched median’ mostly guarantees the implementation of agreement, this allocation pattern makes parliamentary scrutiny less likely and therefore enhances the effectiveness of minority coalition policy making.

To examine our argument, we assemble a bill dataset from Denmark, an exemplary country where governance under minority coalition frequently occurs.Footnote 3 The Danish dataset contains almost 6,000 government bills from over 250 ministries in 13 minority coalitions in the period of 1985–2015. Our descriptive statistics show that the median party is not a coalition member in 63 per cent of all ministries and that the sandwiched median configuration occurs more frequently than the other configurations when the median party stays in the opposition. In addition, we focus on two corollary measures to approximate parliamentary scrutiny. First, we study the duration that government bills spend in the parliamentary policy‐making process. Second, we examine the number of questions bills receive in committee deliberations. Our empirical analyses reveal that, in ministries where the sandwiched median is the case, government bills indeed experience a shorter parliamentary review process and receive fewer committee questions than they do in the other configurations. In other words, when the median stays out of the minority coalition and is being sandwiched, the minority coalition tends to enjoy more effective policy‐making conditions.

Moreover, we further explore two particular empirical implications of the above findings. Our additional empirical endeavour reveals that the presence of specific portfolio allocation patterns at the ministry level is significantly correlated with the amount of ideological divisiveness of the minority coalition. Precisely speaking, we find that the median party is less likely to be part of the minority coalition when intra‐coalition divisiveness is present and that the likelihood of the median party being sandwiched is higher when divisiveness within the minority coalition increases. Taking everything together, our findings shed light on the implications of portfolio allocations for minority coalition policy making in parliamentary democracies, and they may advance our understanding of why minority coalitions have become more prominent than single‐party minority governments.

Policy making in minority governments

Despite the scholarly findings on the long history and the frequent occurrence of minority governments (e.g., Cheibub et al. Reference Cheibub, Przeworski and Saiegh2004; Strøm Reference Strøm1990), research on why they form and how they govern has been scant compared with that on majority governments. Moreover, in the existing literature on minority governments, the scholarly interest has mostly focused on explaining their formation and yet left minority policy making a relatively unexplored territory (e.g., Bergman Reference Bergman1993; Crombez Reference Crombez1996; Kalandrakis Reference Kalandrakis2015; Luebbert Reference Luebbert1986). Although this literature shows under what conditions parties may prefer the form of minority governance over majority ruling, we still know very little about how minority governments sustain without the majority support in parliament (Christiansen & Pedersen Reference Christiansen and Pedersen2014).

Taking a policy‐seeking perspective, Strøm's (Reference Strøm1990) reasoning of the formation of minority governments contends that some parties may choose to stay out of the government to avoid potential electoral loss resulting from government participation.Footnote 4 Nevertheless, these parties are willing to trade their support in parliament with the minority government for short‐term or long‐term policy benefits (e.g., Artés & Bustos Reference Artés and Bustos2008; Bale & Bergman Reference Bale and Bergman2006). This suggests that the effectiveness of minority policy making may largely depend on the minority government's abilities to build legislative alliances with opposition parties in parliament.

Motivated by Strøm (Reference Strøm1984, Reference Strøm1990), several scholars have investigated minority policy making with an interest on the relationship between government and opposition parties. For instance, Falcó‐Gimeno and Jurado (Reference Falcó‐Gimeno and Jurado2011) discover that the ideological fragmentation within the minority government and that within the opposition determine the fiscal performance of the minority government. Klüver and Zubek (Reference Klüver and Zubek2018) reveal that the ideological conflict between government and opposition parties structures the ability of the minority government to take action on its policy agenda. Most importantly, to obtain the trust and support from opposition parties, Christiansen and Damgaard (Reference Christiansen and Damgaard2008) and Christiansen and Pedersen (Reference Christiansen and Pedersen2014) argue that the minority government may rely on formal or informal legislative agreements to ensure its policy‐making performance. Those formally written agreements may further institutionalize minority governance as ‘contract parliamentarism’ (Bale & Bergman Reference Bale and Bergman2006). In addition, Bassi (Reference Bassi2017) contends that parties in the minority government can distribute portfolios in ways so that the final policy output can not only benefit the governing parties but also satisfy the policy interests of their external supporters.

Indeed, recent empirical research has shown that once parties in the minority government reach agreements with ad hoc partners in parliament, they tend to govern well (Field Reference Field2009; Green‐Pedersen Reference Green‐Pedersen2001). However, this body of work pays little attention to the principal–agent problem that occurs when minority policy making needs collaboration between the coalition and opposition parties (e.g., Andeweg Reference Andeweg2000; Müller Reference Müller2000; Strøm Reference Strøm2000). Specifically, in multiparty (majority and minority) governments, ministerial office‐holders have an informational advantage and discretionary power over their portfolios,Footnote 5 and these privileges allow them to draft bills in the shapes they prefer (Laver & Shepsle Reference Laver and Shepsle1996). Also, the electoral incentives to pursue policies of their own party make the ministerial office‐holders likely to betray the agreements they made with their coalition partners, particularly when policy preferences of coalition parties diverge. In response, coalition partners are motivated to employ political institutions to scrutinize and eventually challenge the proposals made by ministerial parties to prevent potential promise‐breaking behaviour (e.g., Carroll & Cox Reference Carroll and Cox2012; Indridason & Kristinsson Reference Indridason and Kristinsson2013; Kim & Loewenberg Reference Kim and Loewenberg2005; Lipsmeyer & Pierce Reference Lipsmeyer and Pierce2011; Thies Reference Thies2001).Footnote 6 Importantly, through monitoring and amending proposals initiated by the ministerial office‐holder in parliament, coalition partners can ameliorate the principal–agent problem by reducing their informational deficits and ultimately implementing previously agreed policies (Martin & Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2011, Reference Martin and Vanberg2014).

Unlike majority coalitions, minority coalitions are known for the need for external support from opposition parties in parliament. Motivated by potential drifting behaviour of ministerial office‐holders, external supporters of the minority coalition should possess as much incentive as coalition partners to scrutinize government bills to protect their own policy benefits (Strøm Reference Strøm1990), particularly when their policy preference deviates from that of the ministerial party. In theory, this suggests that policy making in minority coalitions would be more difficult than that in majority coalitions since both coalition partners and external supporters are motivated to engage in scrutinizing and challenging ministerial proposals to protect their own policy benefits. Excessive parliamentary oversight can potentially hinder a minority coalition from implementing policies, which may further impose considerable electoral costs on coalition parties (Martin Reference Martin2004; Matthieß forthcoming). However, contradictory empirical findings, which demonstrate that minority coalitions have similar policy‐making effectiveness to majority coalitions (Cheibub et al. Reference Cheibub, Przeworski and Saiegh2004; Strøm Reference Strøm1990), suggest that an explanation for how minority coalitions can rule effectively and successfully is warranted.

Portfolio allocation patterns and policy‐making effectiveness in minority coalitions

In her recent work, Bassi (Reference Bassi2017) contends that ruling parties in the minority government can distribute portfolios strategically to make multiparty policy making robust against defections from either ruling partners or external supporters. Specifically, since how portfolios are allocated shapes the final policy outcome of the government, ruling parties may choose an allocation pattern, which results in a specific set of government policies, that not only maximizes their own policy benefits but also satisfies policy preferences of their external supporters.Footnote 7 Building on this perspective, we propose to study minority coalition policy making by investigating the potential effects that different patterns of ministerial portfolio allocation exert on the interactions between the ministerial office‐holder, the coalition partner and the external supporter in the parliamentary policy‐making process.Footnote 8

Our argument, following the literature on policy making in multiparty governments (Martin & Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2005, Reference Martin and Vanberg2011), centres on how the risk of ministerial drift motivates both coalition partners and external supporters to scrutinize government bills in the parliamentary policy‐making process and how distributing portfolios in different patterns conditions these actors’ incentives to engage in parliamentary oversight. In other words, our primary interest lands on the relationship between portfolio allocation patterns and the extent to which government bills are scrutinized in the policy‐making process (i.e., minority policy‐making effectiveness).

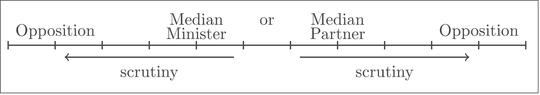

Although we are interested in how the ministerial office‐holder, the coalition partner, and the external supporter interact in the minority policy‐making process, we consider the parliamentary median party the most critical candidate for being an external supporter in our theoretical model. Since minority governance is more policy‐seeking oriented (Strøm Reference Strøm1990) and minority governments can hardly offer office benefits (Bale & Bergman Reference Bale and Bergman2006), parties in minority coalitions have great incentives to build a parliamentary majority with a party that can provide not only additional legislative support but also bargaining leverage over policies. When the median party is not a government member, given its pivotal position in the policy space (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002), it provides parties in the minority coalition exactly what they want for carrying out their policy agenda. Yet, when the median party joins the minority coalition in the first place, either taking the ministerial office or serving as the coalition partner, the very need for additional supporters in parliament can make the implementation of minority coalition policies more complex. Figure 1 depicts our conjecture.

Figure 1. Portfolio allocation and its policy‐making implications in minority coalitions: When the median party is a cabinet member.

Note: The direction of arrows indicates the actors who initiate scrutiny, and the length of arrows represent the levels of scrutiny a government bill may receive.

As illustrated in Figure 1, while the minority coalition holding the median position can choose between an external supporter from either side, this policy‐making choice is likely to come to the benefit of either the ministerial median party or the coalition median partner. Specifically, instead of sticking with the coalition agreement that is likely to be located between the two coalition parties, both the median partner and the median minister have incentives to move the final policy outcome close to themselves. They can profit from offering necessary policy concessions to the closest external party for building a legislative alliance. In the end, this situation may encourage more scrutiny activities initiated by parties from both sides as they all fear policy drift at their expense. For instance, if the minority coalition forms an alliance with the external party located to the right, the partner (being median or not) and the external party on the right will monitor the minister to prevent her from drifting, while the opposition party on the left will also scrutinize ministerial bills to ensure a final policy outcome close to the left.Footnote 9

Put it differently, although the median party controls an advantageous position in policy bargaining and forming a government with the median can be beneficial (Baron Reference Baron1991; Laver & Schofield Reference Laver and Schofield1990; Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002), we expect that holding this position within the minority coalition is likely to make the principal–agent problem worse. It essentially motivates all parties involved in policy making to engage in parliamentary scrutiny and thus reduces the effectiveness of minority coalition policy making. This situation can get even worse when divisiveness of coalition parties increases, as the incentives to monitor and challenge ministerial proposals increase. The above discussion leads to our first hypothesis.

H1: All else being equal, policy making in the minority coalition is less effective when the median party is a coalition member than when it stays out of the coalition.

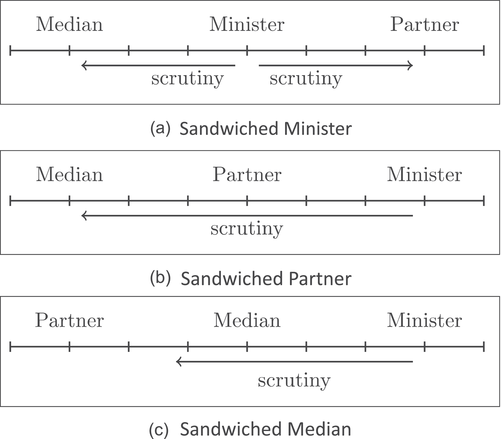

Now, when the median party stays out in the opposition as the external supporter, we can further distinguish three specific patterns of portfolio allocation under minority coalitions: the sandwiched minister, the sandwiched partner and the sandwiched median, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Portfolio allocation and its policy‐making implications in minority coalitions: When the median party is not a cabinet member.

Note: The direction of arrows indicates the actors who initiate scrutiny, and the length of arrows represent the levels of scrutiny a government bill may receive.

The upper panel in Figure 2 presents the situation where the ministerial office‐holder is ideologically surrounded by her coalition partner and the median party (i.e., the external supporter). One possibility in this scenario is that the office‐holder can autonomously draft a bill to her own favour and the coalition partner will approve the bill without scrutinizing it, as the partner believes that the ministerial proposal is constrained by the median party. However, as Martin and Vanberg (Reference Martin and Vanberg2011: 22) show, this only holds in situations where divisiveness of coalition parties is sufficiently small. As soon as this conflict escalates, both the coalition partner and the median party have strong incentives to monitor the minister and her bills to avoid agency loss resulting from potential ministerial drift. As prior work on coalition governance indicates, the coalition partner eventually scrutinizes and challenges the minister in parliament because she prefers the implementation of the coalition compromise (likely to be located between the minister and the partner). Besides, the median party expects the implementation of the legislative agreement she made with the minority coalition as a whole (likely to be located to the left of the minister). In other words, both the partner and the median party are motivated to keep tabs on the minister. Consequently, parliamentary scrutiny from different directions makes the policy‐making process lengthy and less effective.

The middle panel in Figure 2 shows another pattern where the coalition partner is surrounded by the minister and the median party. In this scenario, since the median party provides critical external support to the minority coalition, she has a stronger incentive than the partner to scrutinize and challenge ministerial proposals in order to enforce the implementation of a final policy outcome that is close to her ideal point. For the coalition partner, she knows that bills will be examined by the median party and the final policy outputs are very likely to be moved to somewhere closer to the median party, which means the coalition policy output is likely to be closely located to her own policy preference. As a result, her incentive to scrutinize ministerial proposals should be slightly weaker than the sandwich minister case described above, even if the divisiveness of the coalition presents in this scenario. Consequently, we expect that the joint degree of parliamentary scrutiny in the sandwiched partner case should be slightly lower than that in the sandwiched minister case.Footnote 10

Finally, the lower panel in Figure 2 illustrates the scenario where the median party is ideologically surrounded by the minister and the coalition partner. We expect that the portfolio allocation pattern can effectively ease the principal–agent problem and other difficulties parties face in minority coalition policy making. Specifically, compared with the two scenarios described above, the joint degree of parliamentary scrutiny initiated by the external median party and the coalition partner should be much lower. This is because, in a sense, the median party is included in the policy‐making core of the minority coalition, which can put the median party close to the coalition compromise on which the coalition parties have agreed upon.

When the partner initiates oversight to ensure the implementation of the agreed coalition compromise, it signals the median party that the coalition compromise is likely to be implemented, which further weakens her incentive to scrutinize the government bill. Similarly, when the median party scrutinizes the bill, it also lowers the partners’ incentive to keep an eye on the minister, since she knows that the coalition compromise is very likely to be executed. In other words, placing the median party between coalition parties works as a heuristic that informs both the partner and the external supporter about the likely location of the final policy outcome, which in turn enhances their trust and facilitates the policy‐making process in parliament. This expectation should also hold when coalition divisiveness increases. Based on the discussion above, we may derive our second hypothesis:

H2: All else being equal, when the median party stays out of the minority coalition government, policy making is more effective in the sandwiched median scenario than that in the other scenarios.

Research design and data

To evaluate our expectations, we rely on data from Denmark where political parties frequently govern together in minority coalition governments. Minority coalition policy making, in which ministerial office‐holders are often confronted with the mistrust from both coalition partners and external support parties, has been a regular exercise rather than an exceptional case in Denmark. Moreover, Danish parties in minority coalitions often build legislative alliances with opposition parties in different policy areas (Christiansen & Damgaard Reference Christiansen and Damgaard2008; Green‐Pedersen Reference Green‐Pedersen2001). All these together make Denmark an exemplary country for studying policy‐making effectiveness in minority coalitions. We assemble a dataset covering all Danish government bills initiated by minority coalitions in the period of 1985–2015. Since almost all governments formed in this period are minority coalitions except for the only majority coalition government led by the Social Democrats from 1993 to 1994, this dataset allows us to test how portfolio allocation patterns influence minority coalitions’ policy‐making effectiveness. Overall, the bill dataset covers almost 6,000 bills proposed by 256 ministries in 13 minority coalitions.

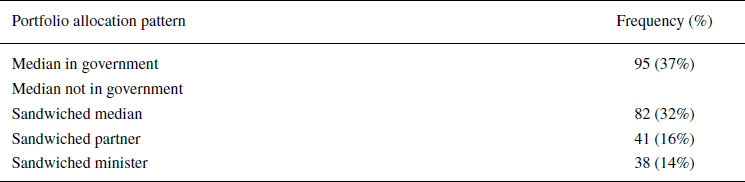

Since our core argument distinguishes four scenarios of portfolio allocation in minority coalitions, our first task is to locate the ideological positions of the ministerial party, the coalition partner party and the external party in different policy areas for each minority coalition in the period we study.Footnote 11 For this purpose, we rely on the Comparative Manifestos Project (CMP) dataset, which documents the policy attention of political parties on a variety of issues across time.Footnote 12 With the CMP dataset, we follow Bäck et al. (Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011) by attaching CMP sub‐policy categories to 13 issue areasFootnote 13 and employ the scaling approach developed by Lowe et al. (Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011) to calculate the ideological positions of parties on these 13 issue areas as well as the importance of those issues to each party. This allows us to locate the area‐specific ideological positions of political parties accordingly. Once we have the information on those parties’ positions, the next task is to attach existing issue areas to portfolios in each minority coalition covered in our sample. Here, we also follow Bäck et al. (Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011) and classify all portfolios into these 13 policy areas.Footnote 14 Finally, based on the relative positions of the ministerial party, the coalition partner party and the legislative median party, we categorize each ministry into the four portfolio‐allocation scenarios we described above. Table 1 summarizes the frequencies of these patterns.

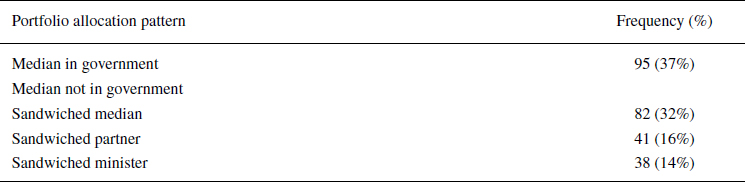

Table 1. Portfolio allocation patterns in Danish minority coalitions (1985–2015)

Note: Total number of ministries is 256.

Our sample covers a total number of 256 ministries in 13 minority coalitions. While the literature often emphasizes the role that the legislative median party can play in a minority government (e.g., Schofield Reference Schofield1993; Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002), our findings on the patterns of portfolio allocation reveal that the median party is rarely included in Danish minority coalitions. Only 37% of the total portfolios in our sample contain the median party as either the minister or the partner.Footnote 15 On the contrary, the median party frequently stays out of government, and this pattern constitutes more than 60% of the portfolios we investigate here. Moreover, when the median party is not a member of the minority coalition, the median party is sandwiched (i.e., ideologically surrounded) by the ministerial and the partner party quite commonly.

Although Table 1 seems to suggest that political parties in Denmark prefer certain patterns of portfolio allocation over others when they govern in minority coalitions, the question of our main interest is whether these patterns are associated with the joint level of parliamentary scrutiny. To test the proposed relationship, we approximate policy‐making effectiveness by relying on two measures that capture the level of parliamentary scrutiny. First, we follow Schulz and König (Reference Schulz and König2000) and Martin and Vanberg (Reference Martin and Vanberg2011) by employing the length of the policy‐making process as a central indicator for the time spent for information acquisition. As monitoring activities consume time, this variable approximates policy‐making effectiveness by measuring the number of days between the day that a bill proposal was introduced and the day that the bill was approved or removed from parliament. The longer a bill stays in this process, the more likely the bill experiences scrutiny, and thus the less effective the minority coalition is on implementing the bill. We collect this information for all ministerial proposals in the period we study.

Second, following recent research on coalition oversight (e.g., Höhmann & Sieberer Reference Höhmann and Sieberer2020; Martin & Whitaker Reference Martin and Whitaker2019; Otjes & Louwerse Reference Otjes and Louwerse2018), we conceptualize parliamentary questions as a potential instrument that parliamentary parties use to solicit policy information from ministerial parties in the policy‐making process.Footnote 16 The policy‐making process is likely to be delayed when a bill receives many inquiries in parliament, and therefore effectiveness can be deteriorated. Furthermore, the number of questions may indicate imperfect drafting and reveal coalition tensions, which threaten to reduce the effectiveness of minority coalitions. To explore how coalition parties and external supporters together scrutinize those bills, we focus on the committee level and collect the total number of questions asked by participating committee members from different parties.Footnote 17 Yet, because of data availability, we only have this information for bills initiated in the period of 2004–2015.Footnote 18

In addition to our portfolio allocation patterns (captured by several indicator variables), we control for a set of variables that may encourage parties to scrutinize government bills and therefore lead to a less effective policy‐making process. First, the level of preference divergence within a coalition has been demonstrated to be a decisive factor that determines how coalition parties deal with their inherent principal–agent problems in the parliamentary policy‐making process (e.g., Bräuninger et al. Reference Bräuninger, Debus and Wüst2017; Martin & Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2011). We measure intra‐coalition policy disagreements by using the index of coalition divisiveness proposed by Martin and Vanberg (Reference Martin and Vanberg2011).Footnote 19 We expect that greater divisiveness leads to a lengthier policy‐making process and provokes more questions in committee deliberations. Second, we control for the overall saliency of a ministry in Denmark in order to account for the potential relationship between the saliency of a ministry and the level of parliamentary scrutiny it receives, although we do not have clear expectations. This information is obtained from an expert survey of Druckman and Warwick (Reference Druckman and Warwick2005). Third, we control for government size in our models. This is measured as the sum of seat shares of all coalition parties. Theoretically, the bigger the government, the less likely it would rely on opposition parties’ support. The size of government thus conditions the influence of opposition parties on minority policy‐making effectiveness. Fourth, we include the number of government parties to account for unobserved coalition dynamics. The increase in the number of coalition parties may raise the bargaining costs within the minority coalition and may change the overall interaction between the coalition and opposition parties. We also generate a dummy variable that indicates whether a ministerial party holds the most extreme policy position in an issue area. We suspect that bills initiated by an extreme minister are more likely to be scrutinized by its coalition partners as well as its external supporters. Finally, we control for issue fixed effects.

Empirical results

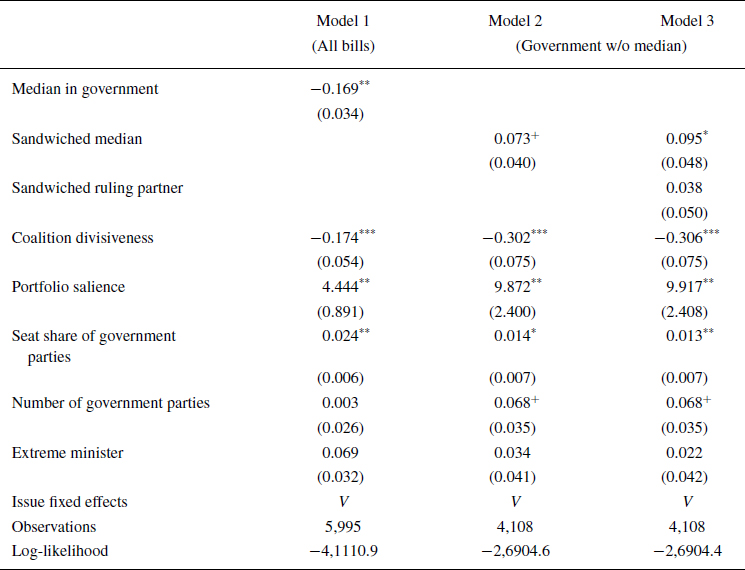

Portfolio allocation and length of policy making

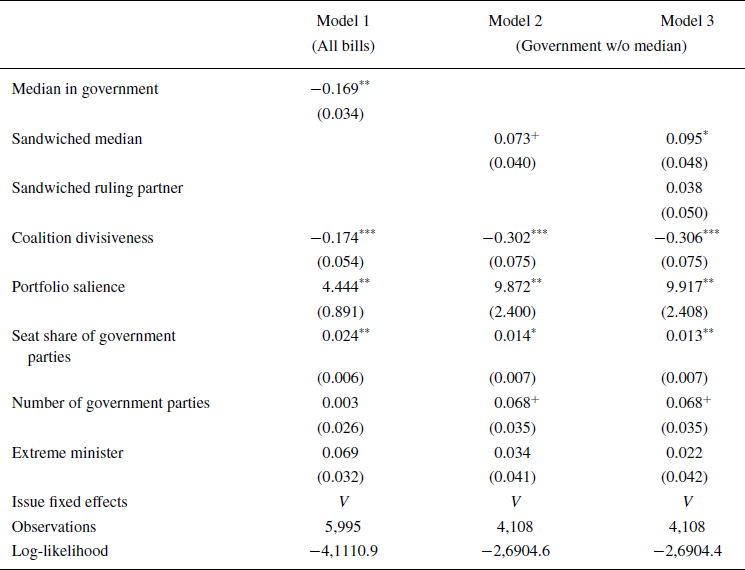

We first evaluate our expectations by examining the relationship between portfolio allocation patterns and the length of the policy‐making process. Since the dependent variable measures the total number of days that a government bill stays in the parliamentary policy‐making process, we employ an event history model for our analyses. Specifically, we perform several Cox regression models with issue area fixed effects, and the estimated results are presented in Table 2. Note that the estimated coefficients of a Cox model are parameterized concerning the hazard rate, so a positive coefficient indicates a higher hazard rate, that is, a shorter survival time. On the contrary, a negative coefficient represents a lower hazard rate and, therefore, a longer survival time.

Table 2. Portfolio allocation and length of parliamentary review, Cox model (1985–2015)

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses.

+p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

We begin with an estimation that distinguishes the situation between whether the median party is a member of the minority coalition. As Model 1 shows, the negative coefficient of median in government suggests that the policy‐making process is significantly longer when the median party is a member of the minority coalition than when the median party is a member of the opposition. Consistent with our expectation, although the median position may constitute an advantaged bargaining position for either the ministerial or the partner party, it increases the scrutiny activities of the non‐median parties to prevent ministerial drift, which lengthens the parliamentary policy‐making process.

In Models 2 and 3, we focus on bills under the situation where the median party is not a member of the minority coalition, and we investigate whether the sandwiched median pattern facilitates the policy‐making process under minority coalitions. In Model 2, we simply employ the indicator variable sandwiched median and make the reference group include the sandwiched partner and sandwiched minister cases. In Model 3, we estimate the effects of sandwiched median and sandwiched partner and make the sandwiched minister scenario the reference group. As demonstrated in both models, the positive coefficient of sandwiched median shows that this particular portfolio allocation pattern reduces the duration that bills stay in parliament. In other words, when the median party is sandwiched by the coalition partner and the minister, it makes minority coalition policy‐making significantly shorter, allowing the minority coalition to implement bills more effectively than other patterns do. These findings are consistent with our expectations.

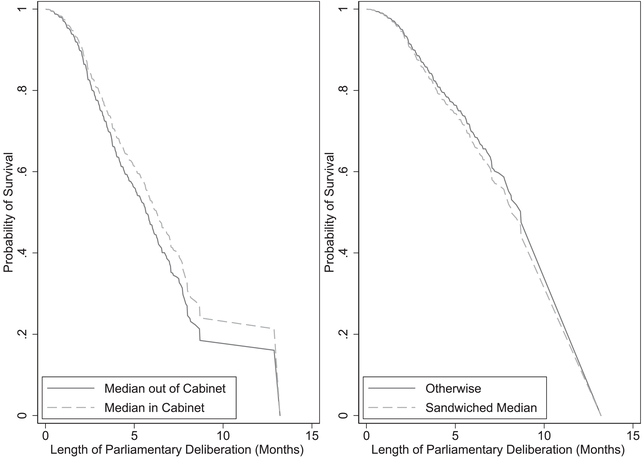

To illustrate the substantive effects of the variables of our interest, we plot the survival probabilities of bills given different portfolio allocation patterns in Figure 3, where the survival functions are derived from Models 1 and 2 presented above. The left panel in Figure 3 shows the estimated survival probabilities of bills given whether or not the median party is a member of the minority coalition. When the median party stays out of the minority coalition (i.e., the solid‐line), the survival experience of bills is always shorter than when the median party is part of the minority coalition (i.e., the dashed‐line). In other words, when the median party is a coalition member, it extends the time that the bills needed in the parliamentary policy‐making process. Moreover, the right panel depicts the estimated survival functions given whether or not the median party is sandwiched when it stays out of the minority coalition. Although the difference is less pronounced, bills stay relatively shorter in parliament when the median party is sandwiched (i.e., the dashed‐line) than when it is not (i.e., the solid‐line). In addition to the variables of interest, we also find that coalition divisiveness, portfolio importance, government size and number of cabinet parties are associated with the length of the policy‐making process in minority coalitions. Specifically, consistent with the coalition governance literature (e.g., Martin & Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2005, Reference Martin and Vanberg2011), we find that greater coalition divisiveness significantly makes government bills stay longer in the policy‐making process, regardless of whether the median party joins the minority coalition or not. For bills initiated from important portfolios, we find that they tend to stay shorter in parliament than those bills initiated in less important ones. We suspect that ministers have less discretion in those portfolios and thus receive less scrutiny as the Folketing pays more attention to bills in important areas. Moreover, minority coalitions with more seats in parliament significantly shorten the policy‐making process since they are less likely to rely on support from external parties. Finally, the increase in the number of coalition parties seems to reduce the duration of policy making, although this is only the case when the median party stays out of the minority coalition.

Figure 3. Portfolio patterns and survival probabilities.

Portfolio allocation and committee questions asked

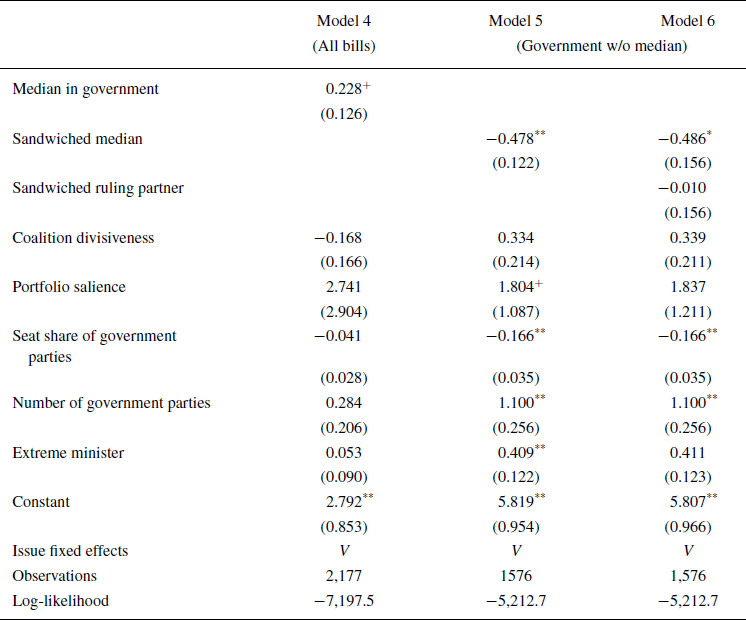

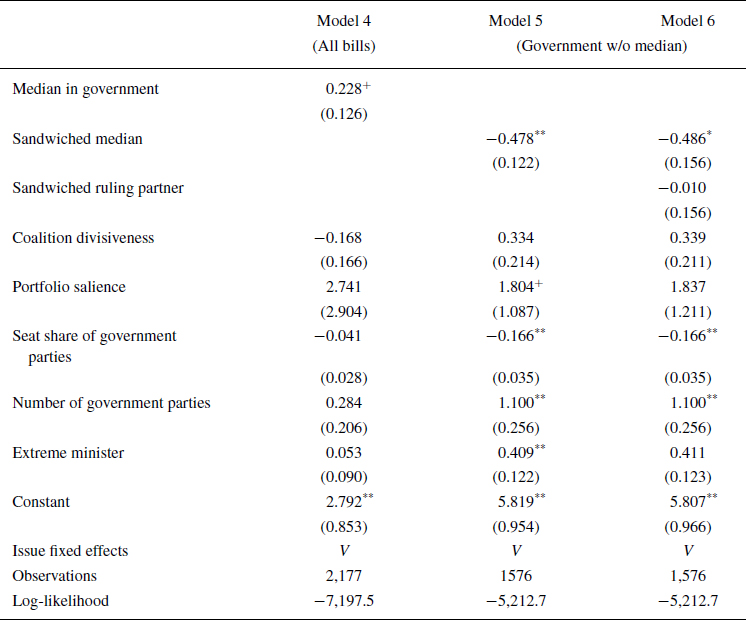

The duration of bills is a prominent yet indirect measure approximating the interaction between those actors involved in the parliamentary policy‐making process. A more direct measure is the total number of questions raised by members of the responsible committee for the bill. This information documents how many questions were asked by both coalition and opposition members during committee deliberations. The more questions a bill receives in the committee review process, the greater level of scrutiny these parties devote to the ministerial proposal. Since the dependent variable here is a count variable, we perform a set of negative binomial regression models with issue fixed effects and present the estimated results in Table 3.

Table 3. Portfolio allocation and committee questions, negative binomial model (2004–2015)

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses.

+p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Unlike our duration data that covers a longer period from 1985 to 2015, the data on committee questions is only available for bills reviewed in parliamentary committees between 2004 and 2015.Footnote 20 That said, the results revealed in Table 3 seem to be consistent with what we already found in Table 2, and most importantly, our argument. More precisely, there are two major findings from Table 3. First, when the median party is a member of the minority coalition, bills receive significantly more committee questions than they do when the median party stays out of the minority coalition (i.e., Model 4), and this may result in a less effective policy‐making process. Second, when the median is not a member of the minority coalition and when it is ideologically surrounded by the parties of the minority coalition (i.e., Model 5 and 6), bills clearly receive fewer questions, meaning that the policy‐making effectiveness in minority coalitions is improved.

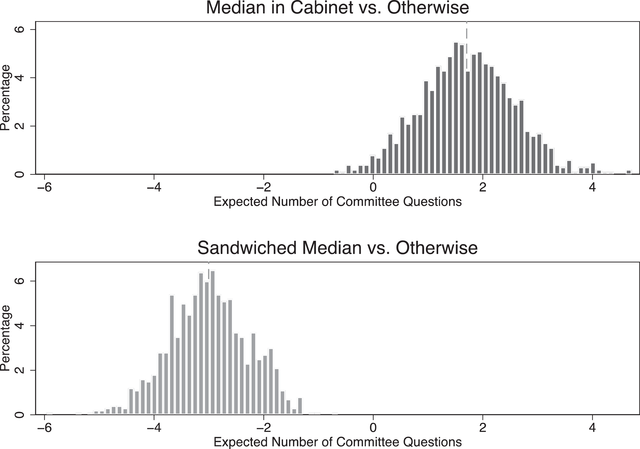

In addition to the estimated results, we illustrate the substantive effects of our findings through a simple simulation exercise. We follow King et al.’s (Reference King, Tomz and Wittenberg2000) strategy by calculating first differences in the predicted number of committee questions a bill would receive given different patterns of portfolio allocation. More precisely, we first draw 1,000 simulated parameters from the models estimated above, and then generate the mean predicted values for the patterns of our interest while holding other variables constant at their mean values.Footnote 21 Finally, we calculate the difference between our scenarios and repeat this process 1,000 times. In the end, we obtain 1,000 simulated values of first differences for each comparison, and we plot the distributions of these values with dashed lines indicating the median values in Figure 4.Footnote 22

Figure 4. Portfolio patterns and committee questions asked.

The upper panel in Figure 4 plots the distribution of the estimated first differences between whether or not the median party is part of the minority coalition. The distribution has a median of 1.8 and its difference from zero is statistically significant (p < 0.001), which suggests that a bill would receive almost two more questions in committee proceedings when the median party is part of the minority coalition than when it is not. Further, the lower panel shows the distribution of the first differences between whether or not the median party is sandwiched by the minister and the coalition partner. As the graph reveals, a bill tends to receive three fewer questions in the sandwiched median scenario than in other scenarios, and the difference is also statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Overall, the results presented in Tables 2 and 3 provide supportive evidence for our argument. When it comes to portfolio allocation in minority coalitions, different patterns resulting from the relative ideological locations of involved actors significantly change the policy‐making effectiveness of minority coalitions in the one or the other direction.

Table 4. Coalition conflict and portfolio patterns in minority coalitions, simple logit models

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses.

+p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

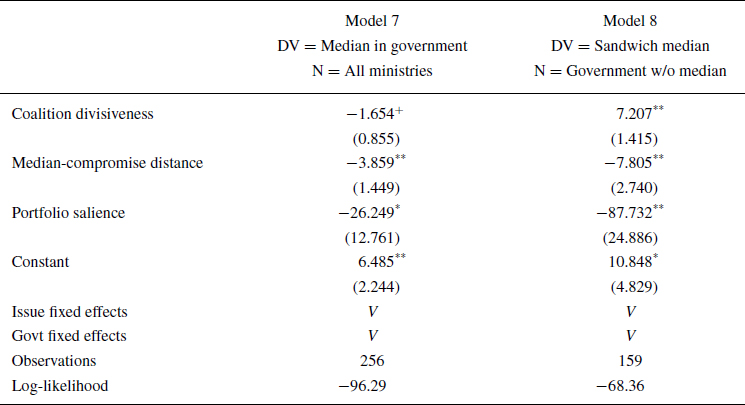

Portfolio allocation patterns in minority coalitions

Up to this point, we have demonstrated that different patterns of portfolio allocation structure the joint level of parliamentary scrutiny cast on government bills, which further determines the policy‐making effectiveness of minority coalitions. One follow‐up question is under which conditions we find these patterns more or less likely in minority coalitions. Put it alternatively, when parties in a minority coalition expect that distributing portfolios in specific ways may have different impacts on the effectiveness of future policy‐making environments, what makes these parties allocate them differently?Footnote 23

Guided by research on majority coalitions, coalition divisiveness seems to be a natural candidate that can help us explain how minority coalitions allocate portfolios on average. Specifically, the amount of coalition divisiveness is likely to produce greater parliamentary scrutiny and therefore a less effective policy‐making process. In this vein, parties in the minority coalition may avoid patterns that bring extra parliamentary scrutiny and make policy making much less effective. Instead, patterns that reduce the chance of government bills being scrutinized and thus a more effective policy‐making environment should be more common.Footnote 24 If this conjecture is correct, then we should observe that the coalition divisiveness index is negatively associated with the presence of the ‘median‐in‐government’ scenario and positively associated with the occurrence of the ‘sandwiched median’ pattern.

Admittedly, this conjecture can be conceptualized as a coalition formation question. That is, parties would prefer coalitions that reduce the level of parliamentary scrutiny and thus enhance policy‐making effectiveness. However, as we have argued, minority coalitions are formed in an uncertain environment about future policy making. Accordingly, they do not completely and perfectly know the level of parliamentary scrutiny, which bills of ministerial office‐holders will experience. This suggests that the patterns are more or less determined when the composition of the coalition is fixed, in particular by the ideological positions of the coalition parties. Nevertheless, we want to examine whether the coalition divisiveness of their ideological positions impacts the set of portfolio allocation patterns – resulting from the formation of a minority coalition – that may bring them the most effective policy‐making environment.

To empirically examine the implications of coalition divisiveness for the set of portfolio allocation patterns, we restructure our dataset such that the unit of analysis is the ministry of a particular minority coalition with 256 ministries in total. We perform two simple logit models with issue and government fixed effects.Footnote 25 In the first model, the dependent variable is a dichotomous variable indicating whether the median party is included as a member of the minority coalition. In the second model, the dependent variable is another dummy variable that captures whether the median party (as an external supporter) is ideologically sandwiched by the parties in the minority coalition. The main explanatory variable is coalition divisiveness, which we have already used in the analyses at the bill level. In addition, we include the ideological distance between coalition compromise and the median party,Footnote 26 and portfolio salience as control variables.Footnote 27

The estimated results are presented in Table 4. As Model 7 shows, coalition divisiveness is negatively associated with the median being a member of the minority coalition, meaning that the median party is less likely to be included in the minority coalition when the level of coalition divisiveness increases. Furthermore, as we can see from Model 8, when coalition divisiveness increases and the median party being the external supporter, the median party is more likely to be ‘sandwiched’ than placed in different locations. These exploratory findings provide additional support for our major argument that having the median party on board in a minority coalition is suboptimal, particularly when coalition divisiveness already exists among coalition parties, and that having the median party sandwiched seems to be a pattern to easing the principal–agent problem in the minority coalition.Footnote 28

Conclusion and discussion

Up until now, policy making in minority governments has received very little scholarly attention. The deviations between conventional expectations of how minority governments would perform and what they actually do have raised several puzzling questions. For instance, how do parties in minority governments govern and under what conditions do they govern effectively? Among the few scholarly works that exist, the attention has focused mainly on the relationship between government and opposition parties due to the need for external support (Bale & Bergman Reference Bale and Bergman2006; Christiansen & Pedersen Reference Christiansen and Pedersen2014; Green‐Pedersen Reference Green‐Pedersen2001; Klüver & Zubek Reference Klüver and Zubek2018; Strøm Reference Strøm1990 ). This study complements this particular literature by focusing on policy making in minority coalitions and investigating how portfolio allocation patterns structure the policy‐making interaction among the major actors in minority coalitions, and by extension, the effectiveness of minority coalitions on managing and implementing policies.

Our analyses reveal several interesting findings by exploring portfolio allocation patterns in 256 ministries from 13 Danish minority coalitions between 1985 and 2015. First, while the parliamentary median party is conventionally considered essential in the policy‐making process of minority governments, we find that the median party is not always included as a member of minority coalitions. Rather, the median party stays out of the minority coalition in about 63 per cent of the portfolios we investigate here. Second, when the median party is not a minority coalition member, we find that the median party is often surrounded by the coalition parties such that the median party is sandwiched by the ministerial party and the coalition partner. This constitutes 50 per cent of the total cases when the median party is not a minority coalition member.

Our further investigation shows that these patterns actually affect the effectiveness of minority coalition policy making. Government bills tend to face a lengthier policy‐making process when the median party is a member of the minority coalition than when it stays out of the government. On the contrary, when the median party serves as an external support party and is sandwiched by coalition parties, the policy‐making process becomes smoother as government bills spend less time in parliament and receive fewer questions in committee deliberations. Interestingly, while the explanatory power of the well‐known median model has been found questionable in predicting the policy‐making dynamics in minority governments (e.g., Ganghof & Bräuninger Reference Ganghof and Bräuninger2006; Klüver & Zubek Reference Klüver and Zubek2018), our results suggest that whether the median party is a government member could be an important factor that conditions its bargaining leverage in the policy‐making process in minority coalitions. Moreover, the findings help us explain why minority coalition policy making can be more effective than what is conventionally considered. Nevertheless, since our empirical investigation relies on a single‐country study, work in the cross‐national context is no doubt needed in the future to explore how far our results can travel.

Finally, our major findings imply that parties in minority coalitions can allocate portfolios to respond to an uncertain policy‐making environment. Through our exploration of portfolio allocation patterns, we find that the presence of certain patterns is associated with the level of coalition divisiveness. Accordingly, the median party is less likely to be included as a government member when coalition divisiveness is high. In addition, when the median party provides external parliamentary support rather than joining the government, the increase in coalition divisiveness makes it more likely for the median party to be ideologically surrounded by the parties of the minority coalition. While this particular finding is encouraging, we consider our additional empirical effort an exploratory attempt, and we understand that our empirical strategy has its limitations. Thus, we believe more work is needed for demonstrating how parties in minority coalitions strategically employ political institutions to promote policy making.

Acknowledgements

This work has received financial support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) via the Collaborative Research Center 884 ‘Political Economy of Reforms’ at the University of Mannheim and the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST). Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article:

Table A1: Government type in Western Europe by country (1945–2017)

Table A2: Assigning Danish ministries to 13 issue categories

Table A3: Summary statistics of the two dependent variables by issue area

Figure A1: Patterns of portfolio allocation across issue area (1985–2015)

Figure A2: Portfolio allocation among government parties across issue area (1985–2015)